Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents.

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

2.4.2. Fatigue Measurement

2.4.3. Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

2.4.4. Depressive Symptoms

2.4.5. Anxiety Symptoms

2.4.6. Cognitive Performance

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

| Predictor Variable | Depression/Anxiety Composite Coefficient | pvalue | Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use Coefficient | pvalue | Use of Central Nervous System-Acting Medications Coefficient | pvalue |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.590 | 0.187 | 4.561 | 0.042 | 0.102 | 0.457 |

| Educational level | 0.020 | 0.951 | 2.620 | 0.108 | –0.067 | 0.502 |

| Age | –0.003 | 0.900 | 0.020 | 0.843 | 0.002 | 0.742 |

| Arterial hypertension | –0.003 | 0.994 | 1.345 | 0.445 | 0.024 | 0.824 |

| Sex (female) | 0.040 | 0.902 | 1.304 | 0.418 | 0.117 | 0.243 |

| Toxic oil syndrome diagnosis | 1.695 | <0.001 | 13.062 | <0.001 | 0.328 | 0.003 |

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

References

- Manuel Tabuenca J. Toxic-allergic syndrome caused by ingestion of rapeseed oil denatured with aniline. Lancet. 1981;2:567–8. [CrossRef]

- Posada De La Paz M, Philen RM, Borda IA. Toxic Oil Syndrome: The Perspective after 20 Years. 2001.

- Kilbourne EM, De La Paz MP, Borda IA, et al. Toxic oil syndrome: A current clinical and epidemiologic summary, including comparisons with the eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:711–7. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Tello F, Navas-Palacios J, Ricoy J, et al. Pathology of a New Toxic Syndrome Caused by Ingestion of Adulterated Oil in Spain. Virchows Arch [Pathol Anat]. 1982;397:261–85.

- Ricoy JR, Cabello A, Rodriguez J, et al. NEUROPATHOLOGICAL STUDIES ON THE TOXIC SYNDROME RELATED TO ADULTERATED RAPESEED OIL IN SPAIN. 1983.

- Alonso-Ruiz A, Calabozo M, Perez-Ruiz F, et al. Toxic oil syndrome. A long-term follow-up of a cohort of 332 patients. Medicine. 1993;72:285–95. [CrossRef]

- Posada de la Paz M, Philen RM, Gerr F, et al. Neurologic outcomes of toxic oil syndrome patients 18 years after the epidemic. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1326–34. [CrossRef]

- del Ser T, Espasandín P, Cabetas I, et al. [Memory disorders in the toxic oil syndrome (TOS)]. Arch Neurobiol (Madr). 1986;49:19–39.

- Ladona MG, Izquierdo-Martinez M, Posada De La Paz M, et al. Pharmacogenetic profile of xenobiotic enzyme metabolism in survivors of the Spanish toxic oil syndrome. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:369–75. [CrossRef]

- Benito-León J, Martínez-Martín P, Frades B, et al. Impact of fatigue in multiple sclerosis: the Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use (D-FIS). Mult Scler. 2007;13:645–51. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin P, Catalan MJ, Benito-Leon J, et al. Impact of fatigue in Parkinson’s disease: the Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use (D-FIS). Qual Life Res. 2006;15:597–606. [CrossRef]

- Badia X, Roset M, Herdman M, et al. A comparison of United Kingdom and Spanish general population time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:7–16. [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory–II. PsycTESTS Dataset. Published Online First: 12 September 2011. [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. [CrossRef]

- Dwolatzky T, Whitehead V, Doniger GM, et al. Validity of a novel computerized cognitive battery for mild cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr. 2003;3:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Doniger GM, Zucker DM, Schweiger A, et al. Towards Practical Cognitive Assessment for Detection of Early Dementia: A 30-Minute Computerized Battery Discriminates as Well as Longer Testing. 2005.

- Schweiger A, Abramovitch A, Doniger GM, et al. A clinical construct validity study of a novel computerized battery for the diagnosis of ADHD in young adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007;29:100–11. [CrossRef]

- Golan D, Wilken J, Doniger GM, et al. Validity of a multi-domain computerized cognitive assessment battery for patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;30:154–62. [CrossRef]

- Doniger GM, Jo MY, Simon ES, et al. Computerized cognitive assessment of mild cognitive impairment in urban African Americans. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24:396–403. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Manheim I, Sinnreich R, Doniger GM, et al. Fasting plasma glucose in young adults free of diabetes is associated with cognitive function in midlife. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28:496–503. [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Manheim I, Doniger GM, Sinnreich R, et al. Body mass index, height and socioeconomic position in adolescence, their trajectories into adulthood, and cognitive function in midlife. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2017;55:1207–21. [CrossRef]

- Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Westlye LT, et al. When does brain aging accelerate? Dangers of quadratic fits in cross-sectional studies. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1376–83. [CrossRef]

- Roe CM, Xiong C, Miller JP, et al. Education and Alzheimer disease without dementia: support for the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Neurology. 2007;68:223–8. [CrossRef]

- Seblova D, Berggren R, Lövdén M. Education and age-related decline in cognitive performance: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;58.

- Wilson RS, Yu L, Lamar M, et al. Education and cognitive reserve in old age. Neurology. 2019;92:E1041–50. [CrossRef]

- Bangen KJ, Werhane ML, Weigand AJ, et al. Reduced regional cerebral blood flow relates to poorer cognition in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:390812. [CrossRef]

- Petrova M, Prokopenko S, Pronina E, et al. Diabetes type 2, hypertension and cognitive dysfunction in middle age women. J Neurol Sci. 2010;299:39–41. [CrossRef]

- Muela HCS, Costa-Hong VA, Yassuda MS, et al. Hypertension severity is associated with impaired cognitive performance. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6. [CrossRef]

- Polentinos-Castro E, Biec-Amigo T, Delgado-Magdalena M, et al. Enfermedades crónicas y multimorbilidad en pacientes con Síndrome de Aceite Tóxico: estudio comparativo con población general. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2021;95.

- García de Aguinaga ML, Posada de la Paz M, Estirado de Cabo E, et al. High prevalence of cardiovascular risk in patients with toxic oil syndrome: A comparative study using the general Spanish population. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19:32–9. [CrossRef]

- Kouvatsou Z, Masoura E, Kiosseoglou G, et al. Evaluating the relationship between working memory and information processing speed in multiple sclerosis. Applied Neuropsychology:Adult. 2022;29:695–702. [CrossRef]

- Slavomira K, Petra H, Daniel C, et al. Information-processing speed in mildly disabled relapsingremitting multiple sclerosis patients correlates with volumetry of optic chiasma and subcortical grey matter nuclei. Bratislava Medical Journal. 2022;123:678–84. [CrossRef]

- Chabriat H, Lesnik Oberstein S. Cognition, mood and behavior in CADASIL. Cereb Circ Cogn Behav. 2022;3. [CrossRef]

- Jolly AA, Anyanwu S, Koohi F, et al. Prevalence of Fatigue and Associations With Depression and Cognitive Impairment in Patients With CADASIL. Neurology. 2025;104. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien JT, Erkinjuntti T, Reisberg B, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:89–98. [CrossRef]

- Katz DI, Cohen SI, Alexander MP. Mild traumatic brain injury DEFINITIONS AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA Mild traumatic brain injury. 2015.

- Anderson JFI, Cockle E. Investigating the effect of fatigue and psychological distress on information processing speed in the postacute period after mild traumatic brain injury in premorbidly healthy adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2021;36:918–29. [CrossRef]

- Bai L, Bai G, Wang S, et al. Strategic white matter injury associated with long-term information processing speed deficits in mild traumatic brain injury. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41:4431–41. [CrossRef]

- Nuño L, Gómez-Benito J, Carmona VR, et al. A systematic review of executive function and information processing speed in major depression disorder. Brain Sci. 2021;11:1–18.

- Biasi MM, Manni A, Pepe I, et al. Impact of depression on the perception of fatigue and information processing speed in a cohort of multiple sclerosis patients. BMC Psychol. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, et al. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202:329–35.

- Yang L, Deng YT, Leng Y, et al. Depression, Depression Treatments, and Risk of Incident Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study of 354,313 Participants. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93:802–9. [CrossRef]

- Brakowski J, Spinelli S, Dörig N, et al. Resting state brain network function in major depression – Depression symptomatology, antidepressant treatment effects, future research. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;92:147–59.

- Martin EM, Srowig A, Utech I, et al. Persistent cognitive slowing in post-COVID patients: longitudinal study over 6 months. J Neurol. 2024;271:46–58. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha A, Basera DS, Kumari S, et al. Assessment of memory deficits in psychiatric disorders: A systematic literature review. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;15:182–93. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Alonso C, Valles-Salgado M, Delgado-Álvarez A, et al. Cognitive dysfunction associated with COVID-19: A comprehensive neuropsychological study. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;150:40–6. [CrossRef]

- Tellez I, Cabello A, Franeh O, et al. Acta Heuropathologica Chromatolytic changes in the central nervous system of patients with the toxic oil syndrome*. 1987.

- Zanon Zotin MC, Sveikata L, Viswanathan A, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive impairment: From diagnosis to management. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021;34:246–57.

- Benito-León J, Sanz-Morales E, Melero H, et al. Graph theory analysis of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging in essential tremor. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:4686–702. [CrossRef]

- Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, et al. CADASIL. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:643–53.

- Su J, Ban S, Wang M, et al. Reduced resting-state brain functional network connectivity and poor regional homogeneity in patients with CADASIL. J Headache Pain. 2019;20. [CrossRef]

- Cheung EYW, Shea YF, Chiu PKC, et al. Diagnostic Efficacy of Voxel-Mirrored Homotopic Connectivity in Vascular Dementia as Compared to Alzheimer’s Related Neurodegenerative Diseases-A Resting State fMRI Study. Life (Basel). 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Kampaite A, Gustafsson R, York EN, et al. Brain connectivity changes underlying depression and fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2024;19. [CrossRef]

- Hainsworth AH, Markus HS, Schneider JA. Cerebral Small Vessel Disease, Hypertension, and Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Hypertension. 2024;81:75–86.

- Batista S, Zivadinov R, Hoogs M, et al. Basal ganglia, thalamus and neocortical atrophy predicting slowed cognitive processing in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2012;259:139–46. [CrossRef]

- Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat Med. 2017;23:28–38. [CrossRef]

- Gusnard DA, Akbudak E, Shulman GL, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex and self-referential mental activity: Relation to a default mode of brain function.

- Chen B, Yang M, Zhong X, et al. Disrupted dynamic functional connectivity of hippocampal subregions mediated the slowed information processing speed in late-life depression. Psychol Med. 2023;53:6500–10. [CrossRef]

- Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, et al. Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Major Depression: Abnormally Increased Contributions from Subgenual Cingulate Cortex and Thalamus.

- Han K, Chapman SB, Krawczyk DC. Altered amygdala connectivity in individuals with chronic traumatic brain injury and comorbid depressive symptoms. Front Neurol. 2015;6. [CrossRef]

- Anderson AJ, Ren P, Baran TM, et al. Insula and putamen centered functional connectivity networks reflect healthy agers’ subjective experience of cognitive fatigue in multiple tasks. Cortex. 2019;119:428–40. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Overall (N = 100) | Control (N = 50) | Patient (N = 50) | P value |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.284 a | |||

| Male | 32 (32.0) | 19 (38.0) | 13 (26.0) | |

| Female | 68 (68.0) | 31 (62.0) | 37 (74.0) | |

| Age, mean (standard deviation) | 59.3 (8.0) | 58.7 (8.2) | 59.9 (7.8) | 0.449 b |

| Education, n (%) | 0.546 a | |||

| Illiterate or primary studies | 44 (44.0) | 20 (40.0) | 24 (48.0) | |

| Secondary or higher | 56 (56.0) | 30 (60.0) | 26 (52.0) | |

| Central nervous system-acting medications, N (%) | 39 (39.0) | 10 (20.0) | 29 (58.0) | <0.001 a |

| Arterial hypertension, N (%) | 42 (42.0) | 9 (18.0) | 33 (66.0) | <0.001 a |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 15 (15.0) | 3 (6.0) | 12 (24.0) | 0.025 a |

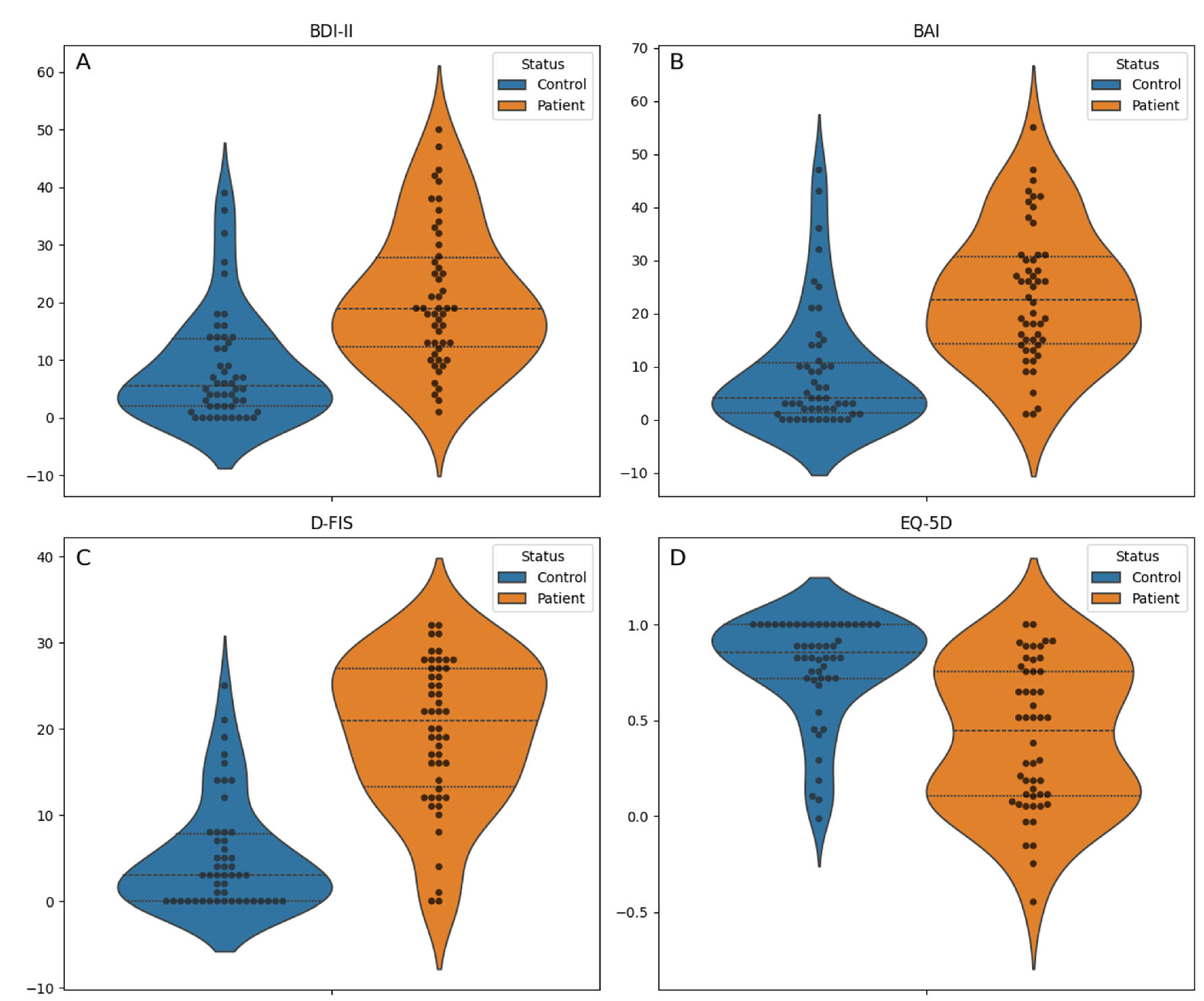

| EQ-5D index, median [Q1, Q3] | 0.7 [0.3, 0.9] | 0.9 [0.7,1.0] | 0.4 [0.1, 0.8] | <0.001 c |

| Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use, mean (standard deviation) | 12.4 (10.4) | 5.2 (6.3) | 19.7 (8.5) | <0.001 b |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory, median [Q1, Q3] | 14.0 [3.0, 26.0] | 4.0 [1.2,10.8] | 22.5 [14.2, 30.8] | <0.001 c |

| Beck Depression Inventory, median [Q1, Q3] | 13.0 [4.8, 21.0] | 5.5 [2.0,13.8] | 19.0 [12.2, 27.8] | <0.001 c |

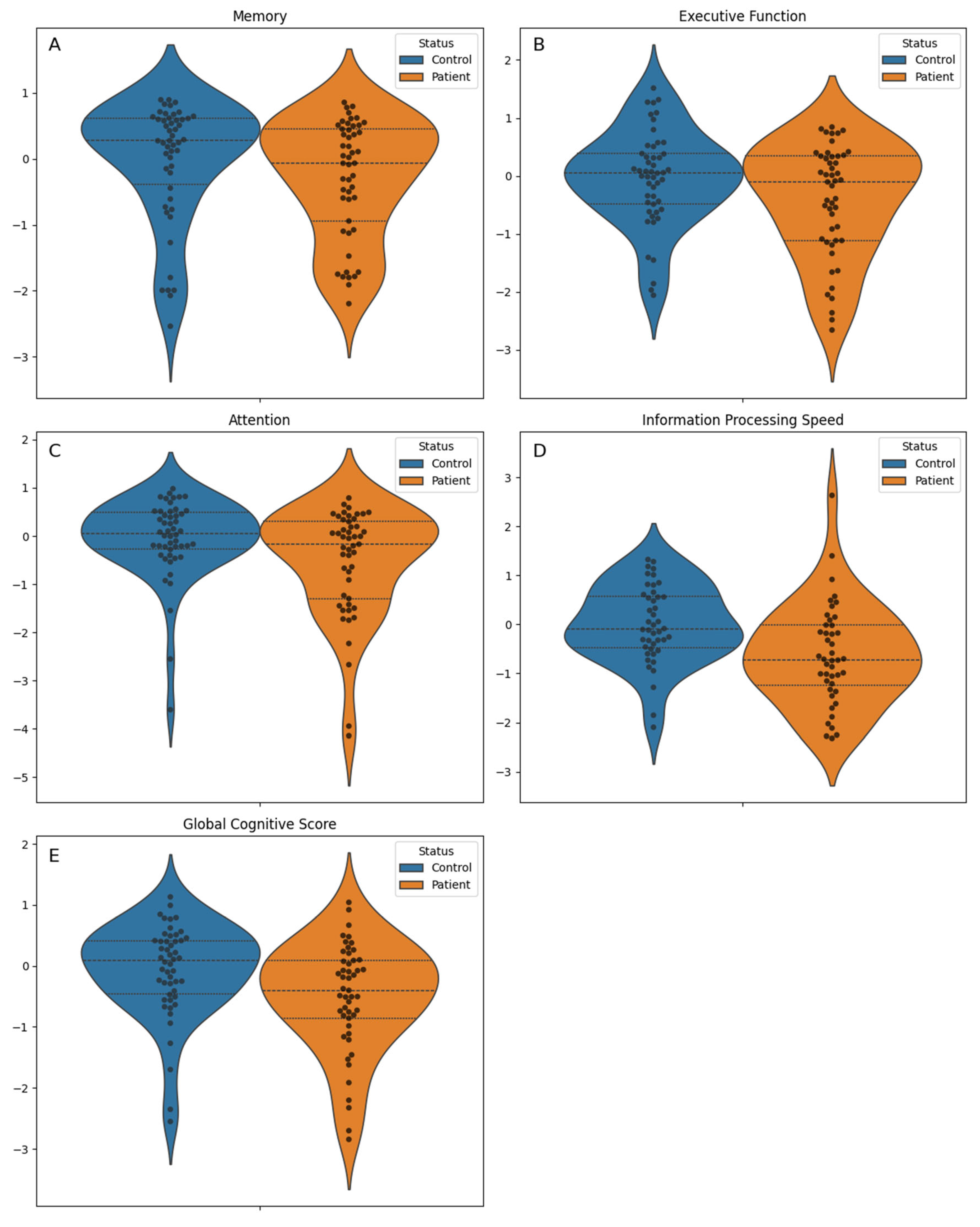

| Global Cognitive Score, mean (standard deviation) | -0.3 (0.9) | -0.1 (0.8) | -0.5 (0.9) | 0.010 b |

| Cognitive domains | ||||

| Memory, median [Q1, Q3] | 0.2 [-0.6, 0.5] | 0.3 [-0.4, 0.6] | -0.1 [-0.9, 0.4] | 0.070 c |

| Executive function, mean (standard deviation) | -0.2 (0.9) | -0.0 (0.8) | -0.4 (1.0) | 0.036 b |

| Attention, median [Q1, Q3] | -0.0 [-0.5, 0.4] | 0.1 [-0.3, 0.5] | -0.2 [-1.3, 0.3] | 0.024 c |

| Information processing speed, mean (standard deviation) | -0.3 (1.0) | -0.0 (0.8) | -0.6 (1.0) | 0.002 b |

| Predictor Variable | Global Cognitive Score Coefficient (p value) | Memory Coefficient (p value) | Executive Function Coefficient (p value) | Attention Coefficient (p value) | Information Processing Speed Coefficient (p value) |

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.183 (0.294) | 0.044 (0.824) | –0.318 (0.107) | –0.472 (0.050) | 0.170 (0.523) |

| Educational level | 0.437 (0.001) | 0.657 (<0.001) | 0.229 (0.119) | 0.213 (0.231) | 0.644 (0.001) |

| Age squared | –0.002 (0.019) | –0.003 (0.004) | –0.001 (0.271) | –0.003 (0.021) | –0.000 (0.910) |

| Age | 0.176 (0.071) | 0.284 (0.012) | 0.057 (0.603) | 0.254 (0.058) | –0.020 (0.904) |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.220 (0.115) | 0.262 (0.101) | 0.218 (0.164) | 0.199 (0.295) | 0.215 (0.273) |

| Sex (female) | –0.356 (0.006) | 0.025 (0.864) | –0.517 (<0.001) | –0.453 (0.010) | –0.439 (0.018) |

| Toxic oil syndrome diagnosis | –0.382 (0.006) | –0.307 (0.050) | –0.274 (0.074) | –0.369 (0.048) | –0.606 (0.002) |

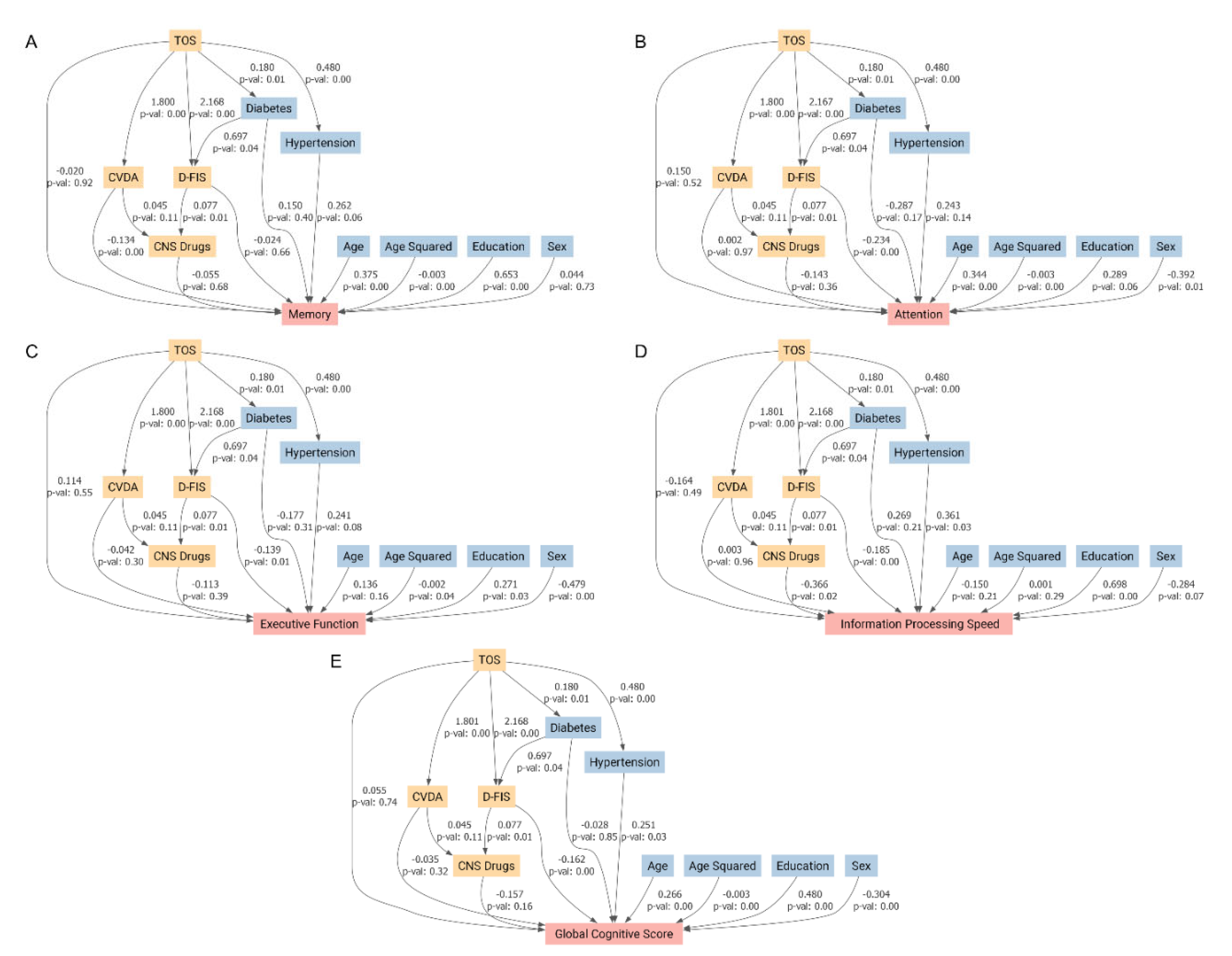

| Global Cognitive Score | Memory | Attention | Executive Function | Information Processing Speed | |

| Average Direct Effect | 0.055 | -0.02 | 0.15 | 0.114 | -0.164 |

| Average Causal Mediation Effects (composite variable of depression/anxiety ) | -0.062 | -0.241 | 0.003 | -0.076 | 0.005 |

| Average Causal Mediation Effects (Fatigue Impact Scale for Daily Use) | -0.351 | -0.051 | -0.508 | -0.302 | -0.402 |

| Average Causal Mediation Effects (Central Nervous System-Acting Medications) | -0.019 | -0.007 | -0.018 | -0.014 | -0.045 |

| Total Effect | -0.377 | -0.318 | -0.372 | -0.278 | -0.606 |

| Mediated proportion | 1.146 | 0.938 | 1.404 | 1.409 | 0.729 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).