1. Introduction

Toxic Oil Syndrome (TOS) is a multisystemic disorder that emerged in Spain in May 1981 following the ingestion of aniline-adulterated rapeseed oil fraudulently sold as olive oil [

1]. The outbreak affected more than 20,000 individuals and led to over 300 deaths within the first year. Clinically, TOS manifested initially with respiratory symptoms, progressing to a chronic phase marked by severe myalgia, eosinophilia, peripheral neuropathy, and scleroderma-like cutaneous changes [

2,

3].

Although its precise pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, current evidence supports a type I hypersensitivity reaction potentially triggered by fatty acid anilides—compounds formed through the interaction of oleic acid and aniline. This mechanism is consistent with the clinical overlap observed between TOS, myalgia-eosinophilia syndrome, and scleroderma [

4].

Three distinct clinical stages have been described: (1) an acute phase (~2 months) characterized by pulmonary edema, rash, eosinophilia, and myalgia; (2) an intermediate phase (months 2–4) marked by peripheral edema, skin induration, hepatic dysfunction, and pulmonary hypertension; and (3) a chronic phase (beyond month 4, with potential partial recovery after two years), featuring scleroderma-like skin changes, sicca syndrome, polyneuropathy, joint contractures, musculoskeletal pain with functional impairment, weight loss, and neuropsychiatric symptoms including memory deficits, anxiety, and depression [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Long-term neurological consequences have been reported among TOS survivors. In a study conducted 18 years post-outbreak, exposed individuals (n=80) demonstrated significantly greater neurological impairment compared to matched controls (n=79), including reduced hand strength, increased vibrotactile thresholds, diminished heart rate variability (suggestive of dysautonomia), and cognitive deficits [

8]. Neuropathological findings such as inflammatory neuropathy and neurogenic muscle atrophy support a neurotoxic mechanism [

9], further corroborated by autopsy evidence of central chromatolysis and vacuolization in spinal motor neurons, the reticular formation, and brainstem nuclei [

10]. Memory impairment remains one of the most commonly reported symptoms. A case-control study of TOS patients with subjective cognitive complaints revealed deficits in attention, episodic and semantic memory, processing speed, and executive function—consistent with a central neurotoxic origin rather than mood-related causes [

11].

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the neurodegenerative potential of TOS. One involves vascular and immune-mediated injury, whereby fatty acid anilides may disrupt the blood-brain barrier by promoting endothelial dysfunction and sustained proinflammatory cytokine release, increasing CNS vulnerability [

4,

12]. Another proposed mechanism is oxidative stress: these compounds can generate peroxides, triggering oxidative damage, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction—well-established contributors to neurodegeneration [

13,

14]. A third hypothesis suggests direct neurotoxicity, although the direct cytotoxic effects of these compounds on neural tissue remain poorly characterized. Patients with TOS and neuromuscular symptoms showed increased levels of homovanillic acid and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in cerebrospinal fluid. Interestingly, mice treated with oleyl anilide did not develop clinical or histological signs compatible with TOS but exhibited serotonin depletion and elevated 5-HIAA levels, suggesting that toxic agents involved in TOS induced changes in monoamine neurons of the brain [

15].

Notably, these mechanisms closely resemble those implicated in classical neurodegenerative disorders [

14]. Given the persistence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and the reported decline in quality of life among survivors, it is plausible that TOS may act as a trigger for a slowly progressive neurodegenerative process extending beyond the acute phase.

Over the past decade, the use of blood-based biomarkers for detecting neurodegeneration has gained increasing attention. Neurofilament light chain (NfL), measurable in both cerebrospinal fluid and plasma, has emerged as a sensitive marker of axonal injury, useful for distinguishing neurodegenerative diseases from primary psychiatric conditions [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Similarly, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), released by reactive astrocytes, has been proposed as a more specific marker of central nervous system astrogliosis and neurodegeneration [

20,

21], with elevated levels reported in AD [

22], Parkinson’s disease [

23], multiple sclerosis [

24], and traumatic brain injury [

25]. Moreover, plasma phosphorylated tau isoforms—especially pTau217 and pTau231—are strongly associated with amyloid PET positivity, making them promising candidates for early detection of AD pathology [

26].

Based on this rationale, the present study aimed to assess blood concentrations of NfL, GFAP, and pTau217 in individuals with a history of TOS compared to matched healthy controls. Our goal was to determine whether these long-term survivors exhibit biomarker profiles suggesting chronic progressive neurodegeneration potentially attributable to the original toxic exposure.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the 12 de Octubre University Hospital (CEIC codes: 17/035 and 23/616). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

2.2. Study Design and Setting

Between April and June 2024, individuals diagnosed with Toxic Oil Syndrome (TOS) and healthy controls were recruited from Madrid, one of the regions most severely affected by the epidemic outbreak in 1981. This case-control study was conducted at the 12 de Octubre University Hospital in Madrid, Spain, where all interviews and blood sampling procedures were performed.

2.3. Participants

TOS cases had been identified according to the diagnostic criteria established in the epidemiological studies conducted during the original outbreak [

27,

28], and these diagnoses were reviewed at the time of enrolment in the present study. Eligible participants were those who had experienced either the acute or the chronic phase of the syndrome. The acute phase was characterized by alveolar–interstitial pulmonary infiltrates and/or pleural effusion in the presence of absolute eosinophilia greater than 500 cells/mm³. The chronic phase was defined by the presence of myalgia and eosinophilia and/or at least one of the following clinical features clearly attributable to TOS: scleroderma-like skin changes, peripheral neuropathy, pulmonary hypertension, or hepatopathy.

Patients were recruited from the hospital’s specialized clinical unit for TOS, the only dedicated center in Spain providing long-term follow-up and care for affected individuals. Participants were contacted consecutively until the target sample size of 50 patients was reached.

The control group consisted of 50 individuals without a history of TOS, recruited from friends and acquaintances residing in the same geographic area. Controls were frequency-matched to cases by age (±5 years), sex, and educational attainment. They shared similar demographic, sociocultural, and environmental characteristics with the patients but did not suffer any symptoms of TOS during the original outbreak.

Exclusion criteria for both groups included a diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease), a history of stroke, chronic renal disease, chronic alcohol misuse, or any traumatic injury or clinical condition affecting the central or peripheral nervous system.

Demographic and clinical data—including age, sex, education level, medical history, cognitive complaints, and current pharmacological treatments—were collected using a standardized structured questionnaire.

2.4. Biomarker Quantification

- -

Sample Collection and Handling

Peripheral blood samples were obtained by standard venipuncture from an antecubital vein EDTA vacutainer tube. Immediately after collection, tubes were gently inverted to mix with anticoagulant and kept at 4 °C until processing. Plasma was separated within 2 hours of draw by centrifugation (2,000 ×g for 10 min at 4 °C) [

29]. The supernatant plasma was aliquoted into polypropylene cryotubes and stored at –80 °C until analysis. These procedures ensured optimal sample stability and minimized pre-analytical variability prior to biomarker assays [

29].

- -

GFAP Quantification (Quanterix SIMOA SR-X)

GFAP concentrations were measured using a Single Molecule Array (SIMOA) immunoassay GFAP Discovery Kit (ref:102336, lot:504261 Quanterix, Billerica, MA, USA) on the Quanterix SR-X ultra-sensitive detection platform. This ultra-sensitive digital immunoassay allows the detection of GFAP at femtogram-per-milliliter levels, with a sensitivity approximately 1000-fold greater than that of conventional ELISA methods [

30].

Prior to analysis, plasma samples were thawed at room temperature for 1 hour, mixed on a vortex for 10 seconds, and centrifuged at 10,000 xg for 5 minutes. Assays were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions, including the use of kit-provided calibrators (for standard curve generation) and two quality controls (QC) in each run. The SIMOA platform offers a broad analytical measuring range; for the GFAP assay, the lower limit of detection was approximately 0.21 pg/mL (with a functional lower limit of quantification ~0.7 pg/mL), and the dynamic range extended up to ~4000 pg/mL in plasma [

31]. All sample readings fell within the linear range of the assay. Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <15% based on kit specifications, reflecting high precision and reliability in GFAP quantification.

- -

pTau217 and NfL Quantification (Fujirebio Lumipulse G600II CLEIA)

Plasma phosphorylated tau at threonine 217 (pTau217) and NfL were measured using the Lumipulse G600II automated immunoassay system (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan). The Lumipulse G600II is a fully automated bench-top analyzer based on a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (CLEIA) principle [

32,

33].

Each analyte was assayed with a dedicated immunoreaction cartridge Lumipulse G pTau 217 Plasma (ref: 81472, lot: D4C4129) and Lumipulse G NfL Blood kits (ref: 81215; lot: Y8B4022), respectively, which incorporates a two-step sandwich immunoassay. In brief, sample plasma is first incubated with magnetic particles coated with capture antibodies specific to pTau217 or NfL, followed by a reaction with an enzyme-conjugated detection antibody. After automated washing steps, a chemiluminescent substrate is added; the ensuing enzyme-driven light emission is measured by the system’s photodetector, with luminescence intensity proportional to the analyte concentration. The CLEIA technology allows rapid analyte detection (results in ~30–60 minutes) and a throughput of ~60 tests/hour on the G600II platform [

32,

33]. All steps—sample handling, incubation, washing, and signal detection—are performed automatically by the analyzer, which improves workflow efficiency and analytical consistency [

32,

33].

Plasma samples were thawed for 30 min at room temperature, shaked by vortex for 10 s, and centrifuged at 2,000 xg for 5 min before the analysis. All pTau217 and NfL assays were run in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol, including the use of 5-point calibration curves and internal controls to verify assay performance. The Lumipulse platform has been extensively validated for neurodegenerative biomarkers and is noted for its high analytical sensitivity and precision. The Quality Controls were provided by the manufacturer and were measured at the beginning of each analytic session. In comparative studies, the automated Lumipulse CLEIA assays demonstrated outstanding performance in terms of assay linearity, low intra-/inter-assay variability, and excellent reproducibility [

32,

33]. The analytical sensitivity (functional detection limit) of the plasma pTau217 and NfL assays is in the low pg/mL range, making them well-suited for quantifying these low-abundance biomarkers in blood. The fully automated and standardized nature of the Lumipulse G600II platform minimizes operator-dependent error and ensures reliable measurement of pTau217 and NfL in all samples [

32,

33]. This approach yields data of comparable quality to traditional cerebrospinal fluid assays, supporting the use of plasma pTau217 and NfL as robust biomarkers of neurodegeneration in the context of TOS survivors.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and figure generation were performed using Python (v3.12.2) and R (v4.4.2). The following Python libraries were employed: pandas (v2.2.3) for data handling, TableOne (v0.9.1) for descriptive statistics, statsmodels (v0.14.4) for regression analysis, semopy (v2.3.11) for structural equation modeling, and rpy2 (v3.5.16) for integrating R within Python. In R, the emmeans package (v1.10.5) was used to calculate estimated marginal means.

A descriptive analysis was first conducted to characterize the study population. Group differences were assessed using parametric or non-parametric tests as appropriate to variable distribution. Biomarker concentrations (NfL, GFAP, and pTau217) were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. Finally, standardized linear regression models were applied to assess associations between biomarker levels and demographic or clinical variables (e.g., age, sex, cognitive complaints, comorbidities), adjusting for relevant covariates.

3. Results

The study included 50 individuals with clinically confirmed TOS and 50 healthy controls, matched for age and sex. There were no significant differences between groups in sex distribution, mean age, or years of education, according to selection rules. The TOS group exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of arterial hypertension (66% vs. 18%; p < 0.001) and diabetes mellitus (24% vs. 6%; p = 0.025). A summary of demographic and clinical characteristics is presented in

Table 1.

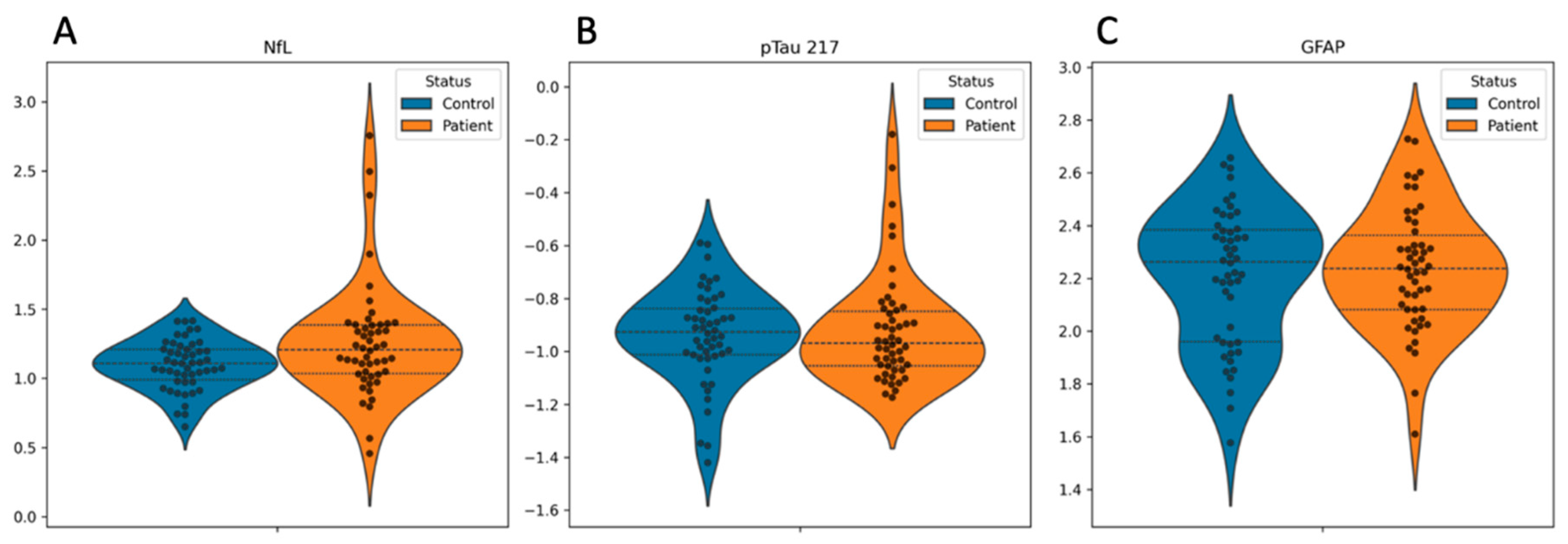

Blood biomarker concentrations are shown in

Figure 1. Compared to controls, the TOS group demonstrated slightly elevated blood NfL levels, although this difference appeared to be driven by a small number of outliers and did not reach statistical significance (

Figure 1A). No significant group differences were observed in blood concentrations of pTau217 or GFAP (

Figure 1B and 1C, respectively).

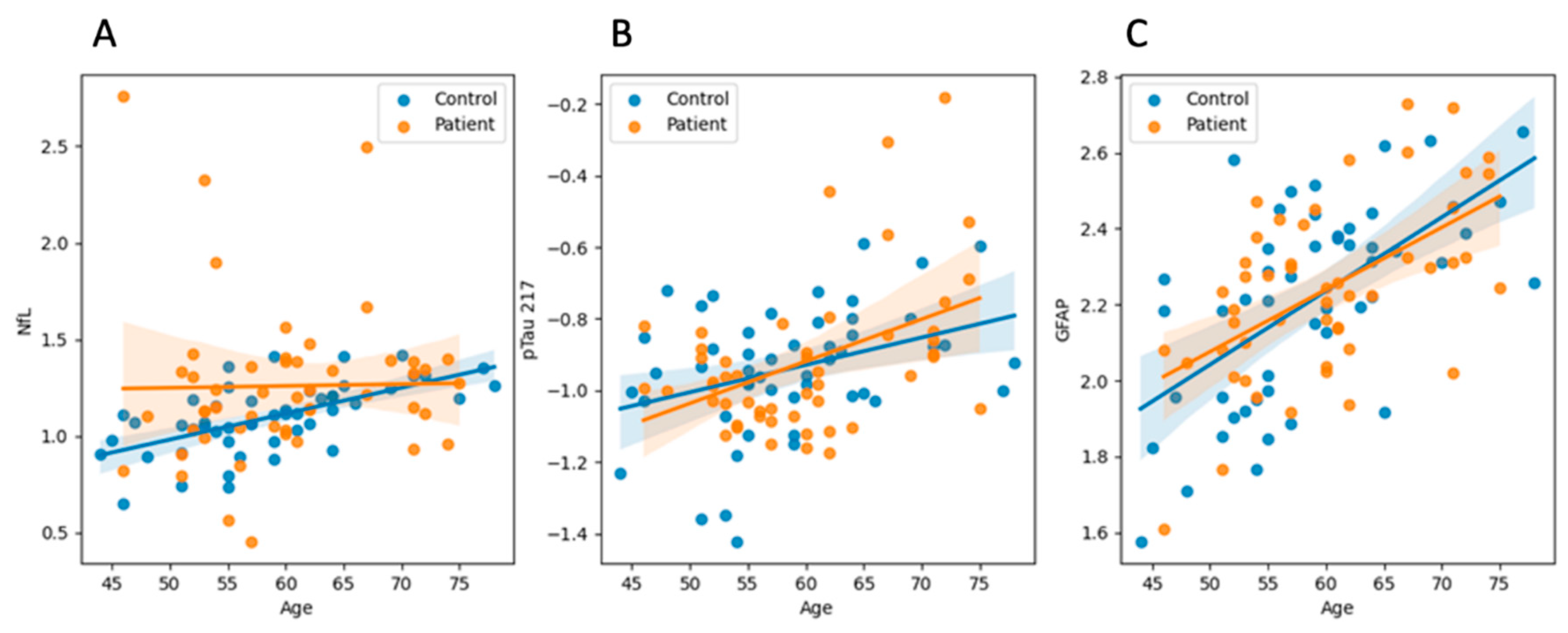

We performed multiple linear regression analyses using z-scored values of GFAP, NfL, and pTau217 as dependent variables to explore predictors of biomarker concentrations. Age emerged as a robust predictor, showing significant positive associations with GFAP (p < 0.001) and pTau217 (p = 0.003), indicating higher biomarker levels among older individuals (see

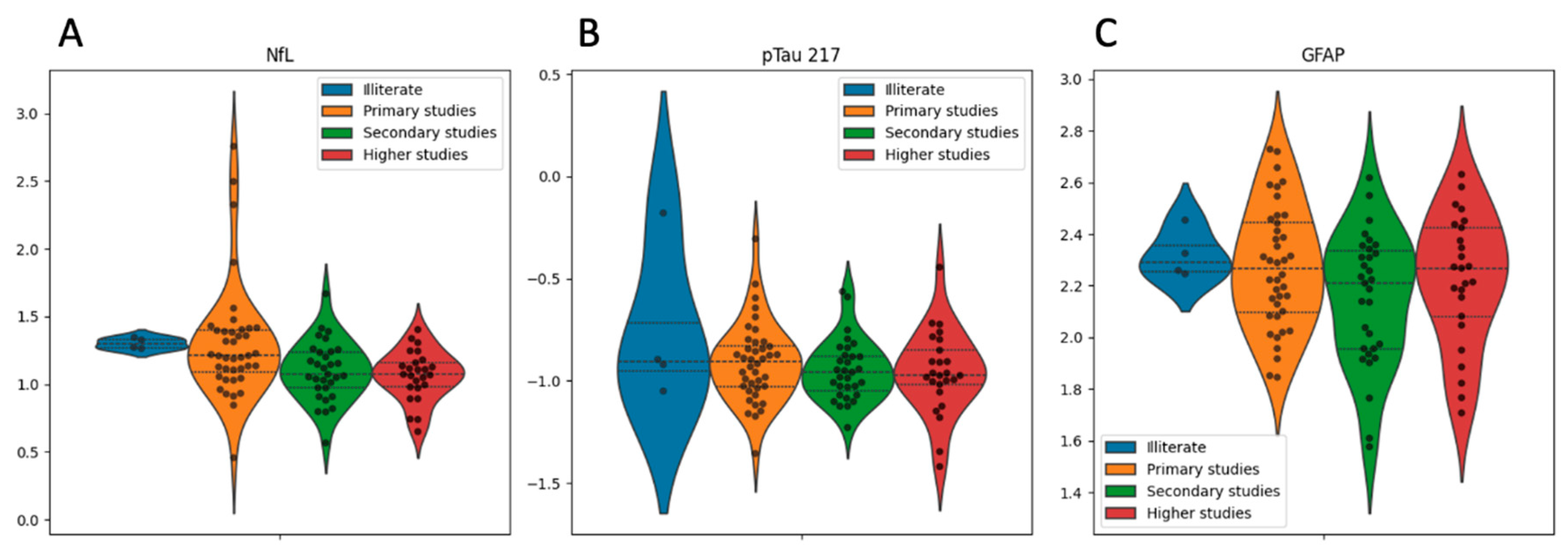

Figure 2). Sex was independently associated with GFAP, with significantly higher levels observed in women compared to men (p = 0.016). Educational attainment demonstrated a significant inverse association with NfL (p = 0.020), suggesting a potential protective effect of higher education (

Figure 3A), although its associations with GFAP (p = 0.073) and pTau217 (p = 0.906) were not statistically significant (

Figure 3B and 3C, respectively). Diabetes mellitus showed a marginal association with increased pTau217 levels (p = 0.063), while arterial hypertension displayed a non-significant trend toward lower NfL levels (p = 0.071). Neither clinical status (TOS vs. control) nor the presence of peripheral neuropathy were significant predictors of any biomarker levels (all p > 0.10).

4. Discussion

In this case-control study, we investigated blood concentrations of NfL, GFAP, and pTau217 in long-term survivors of TOS four decades after the initial outbreak. We aimed to explore whether these blood-based biomarkers of neuroaxonal injury and neurodegeneration could reveal evidence of chronic or progressive neurological involvement in this unique population.

While NfL levels were marginally higher in the TOS group compared to matched controls, the difference was not statistically significant. This finding suggests that ongoing neuroaxonal degeneration is unlikely to be a predominant process in most long-term survivors, while a few cases showing very high levels of plasma NfL could have experienced marked neuroaxonal damage. This stands in contrast to well-characterized neurodegenerative disorders, such as AD or frontotemporal dementia, where elevated NfL levels in blood or cerebrospinal fluid consistently reflect progressive neuronal loss [

16,

18]. Nevertheless, subtle elevations in NfL—especially in individuals with persistent symptoms— may still indicate residual effects of past toxic or inflammatory insults, and peripheral or central axonal damage cannot be entirely excluded. The overall stability of NfL levels aligns with prior clinical studies showing that the neurological manifestations of TOS were disabling but tended to plateau over time rather than follow a progressive trajectory [

8].

The analysis of pTau217 was designed to screen for covert AD pathology, motivated by the high prevalence of memory and other cognitive complaints in this cohort [

11]. Our results showed no significant differences between TOS patients and controls, providing no support for the hypothesis that AD-like tau pathology underlies the cognitive complaints observed in these individuals. These findings are consistent with previous neuropsychological and pathological studies that have implicated toxic or vascular mechanisms—rather than classic neurodegeneration—as the principal contributors to TOS-related cognitive dysfunction [

9,

12].

GFAP was included as an exploratory biomarker of astrocytic activation. Although no group differences were detected, GFAP levels increased with age and were higher in women, consistent with prior literature in both healthy aging and neurodegenerative contexts [

21,

22]. The absence of elevated GFAP in TOS patients may suggest that any acute-phase astrogliosis has already been resolved and that astroglial reactivity is currently minimal in this chronic stage of the disease. Alternatively, chronic low-grade glial activation may persist below the detection threshold of current assays.

These results should be interpreted within the clinical context of the cohort. Participants were followed in a general clinical setting and did not undergo serial cognitive testing. Although many patients reported cognitive decline, objective longitudinal measures are lacking. Consequently, the absence of biomarker abnormalities at a late single time point does not preclude the possibility of subtle or slowly evolving neurotoxic processes that remain below detectable thresholds. This is particularly relevant given the known links between environmental toxins and neurodegeneration. In Parkinson’s disease, for example, prolonged exposure to pesticides or solvents has been associated with increased risk via mechanisms such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation [

34,

35,

36]. Similar mechanisms —particularly endothelial injury, blood-brain barrier disruption, and immune-mediated neural damage— have been proposed in TOS [

3,

4]. It is, therefore, plausible that the initial toxic exposure to TOS may have initiated insidious, long-lasting changes in the central nervous system that are not readily captured by cross-sectional blood biomarkers.

Furthermore, it is important to recognize that blood biomarkers in neurodegeneration are still an emerging field [

19]. For instance, in progressive forms of multiple sclerosis, blood NfL levels may remain normal despite clinical deterioration, while GFAP levels better reflect disease progression [

37]. The temporal dynamics, cellular specificity, and sensitivity of these markers remain active areas of investigation, especially in non-classical neurodegenerative conditions such as TOS.

This study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes longitudinal tracking of biomarker dynamics or symptom evolution. Second, the modest sample size may have limited power to detect small but meaningful differences. Third, the lack of neuroimaging restricts the ability to correlate biomarker levels with structural parameters such as cortical or subcortical atrophy. Fourth, participants were not followed in specialized neurology clinics, and clinical impressions of cognitive decline were not formally assessed. Finally, residual confounding but unmeasured factors such as comorbidities or lifestyle variables cannot be ruled out.

In summary, our findings do not support the presence of overt or progressive neurodegeneration in long-term survivors of TOS, as reflected by blood concentrations of NfL, GFAP, and pTau217. However, the possibility of low-grade, localized, or slowly evolving neurotoxic injury cannot be excluded. Future studies incorporating larger cohorts, longitudinal follow-up, advanced neuroimaging, and multimodal biomarker assessments will be essential to clarify the long-term neurological consequences of TOS and to determine whether a subset of survivors may benefit from closer neurological monitoring.

Author Contributions

Mariano Ruiz-Ortiz collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the writing of the manuscript's first draft and the review and critique of the manuscript. José Lapeña-Motilva collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project; 2) the statistical analysis design; and 3) the review and critique of the manuscript. Verónica Giménez de Bejar collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Fernando Bartolomé collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Carolina Alquézar collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Minerva Martinez-Castillo collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Sonia Wagner-Reguero collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Teodoro del Ser collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. María Antonia Nogales collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Sonia Alvarez-Sesmero collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Montserrat Morales collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. Cecilia García-Cena collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the writing of the manuscript's first draft and the review and critique of the manuscript. Julián Benito-León collaborated with 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was funded by project TED2021-130174B-C33, supported by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union's ‘NextGenerationEU’/PRTR.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all participating patients for their time, trust, and commitment to this study. Their collaboration made this research possible. José Lapeña-Motilva, Mariano Ruiz-Ortiz, Verónica Giménez de Bejar, and Julián Benito-León are supported by the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grants TED2021-130174B-C33, NETremor, and PID2022-138585OB-C33, Resonate). Mariano Ruiz-Ortiz is additionally supported by the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant PID2022-138585OB-C33, Resonate) and through a Río Hortega contract (CM22/00183). Julián Benito-León is also supported by the National Institutes of Health (NINDS R01 NS39422 and R01 NS094607). Fernando Bartolomé receives support from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP20/00009, PI21/00183, and PI24/00099) and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RED2022-134774-T). Carolina Alquézar is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP21/00049 and PI22/00345), the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (RED2022-134774-T and CNS2024-154198), the Eugenio Rodríguez Pascual Foundation (FERP-2022-5), and the Fundación Luzón (Ayudas Unzué Luzón 2024).

Disclosures

Dr. José Lapeña-Motilva (joselapemo@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Mariano Ruiz-Ortiz (mariano.ruiz.ortiz@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Verónica Giménez de Bejar (neuro.gimenezdebejar@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Fernando Bartolomé (fbartolome.imas12@h12o.es) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Carolina Alquézar (carolinaalquezar.imas12@h12o.es) reports no relevant disclosures. Minerva Martinez-Castillo (mmartinez@fundacioncien.es) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sonia Wagner-Reguero (swagner@fundacioncien.es) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Teo del Ser (tdelser@fundacioncien.es) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. María Antonia Nogales (mariaantonia.nogales@salud.madrid.org) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sonia Alvarez-Sesmero (sasesmero@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Montserrat Morales (montserrat.morales@salud.madrid.org) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Cecilia García-Cena (cecilia.garcia@upm.es) reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Julián Benito-León (jbenitol67@gmail.com reports no relevant disclosures.

References

- Tabuenca, M.J. Toxic-allergic syndrome caused by ingestion of rapeseed oil denatured with aniline. Lancet. 1981, 2, 567–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, E.M.; Posada de la Paz, M.; Abaitua Borda, I.; Diez Ruiz-Navarro, M.; Philen, R.M.; Falk, H. Toxic oil syndrome: a current clinical and epidemiologic summary, including comparisons with the eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991, 18, 711–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelpí, E.; de la Paz, M.P.; Terracini, B.; Abaitua, I.; de la Cámara, A.G.; Kilbourne, E.M.; Lahoz, C.; Nemery, B.; Philen, R.M.; Soldevilla, L. ; Tarkowski S; WHO/CISAT Scientific Committee for the Toxic Oil Syndrome. Centro de Investigación para el Síndrome del Aceite Tóxico. The Spanish toxic oil syndrome 20 years after its onset: a multidisciplinary review of scientific knowledge. Environ Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 457–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoshida, S.H.; German, J.B.; Fletcher, M.P.; Gershwin, M.E. The toxic oil syndrome: A perspective on immunotoxicological mechanisms. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1994, 19, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Ruiz, A.; Calabozo, M.; Perez-Ruiz, F.; Mancebo, L. Toxic oil syndrome: A long-term follow-up of a cohort of 332 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993, 72, 285–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Ser Quijano, T.; Esteban García, A.; Martínez Martín, P.; Morales Otal, M.A.; Pondal Sordo, M.; Pérez Vergara, P.; Portera Sánchez, A. Evolución de la afección neuromuscular en el síndrome del aceite tóxico [Course of neuromuscular involvement in the toxic oil syndrome]. Med Clin (Barc). 1986, 87, 231–6, Spanish. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Castroviejo, I. A multisystemic disease caused by adulterated rapeseed oil. Brain Dev. 1988, 10, 84–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Paz, M.P.; Philen, R.M.; Gerr, F.; Letz, R.; Ferrari Arroyo, M.J.; Vela, L.; Izquierdo, M.; Arribas, C.M.; Borda, I.A.; Ramos, A.; Mora, C.; Matesanz, G.; Roldán, M.T.; Pareja, J. Neurologic outcomes of toxic oil syndrome patients 18 years after the epidemic. Environ Health Perspect. 2003, 111, 1326–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martinez-Tello, F.J.; Tellez, I. Extracardiac vascular and neural lesions in the toxic oil syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991, 18, 1043–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricoy, J.R.; Cabello, A.; Rodríguez, J.; Téllez, I. Neuropathological studies on the toxic syndrome related to adulterated rapeseed oil in Spain. Brain. 1983, 106, 817–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Ser, T.; Espasandín, P.; Cabetas, I.; Arredondo, J.M. Trastornos de memoria en el síndrome del aceite tóxico (SAT) [Memory disorders in the toxic oil syndrome (TOS)]. Arch Neurobiol (Madr). 1986, 49, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood–brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018, 14, 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fournier, E.; Efthymiou, M.L.; Lecorsier, A. Spanish adulterated oil matter: An important discovery by Spanish toxicologists—the toxicity of anilides of unsaturated fatty acids. Toxicol Eur Res. 1982, 4, 107–12. [Google Scholar]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Lungu, I.I.; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An Overview of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- del Ser, T.; Franch, O.; Portera, A.; Muradas, V.; Yebenes, J.G. Neurotransmitter changes in cerebrospinal fluid in the Spanish toxic oil syndrome: human clinical findings and experimental results in mice. Neurosci Lett. 1986, 67, 135–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaetani, L.; Blennow, K.; Calabresi, P.; Di Filippo, M.; Parnetti, L.; Zetterberg, H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019, 90, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xin, Y.; Meng, S.; He, Z.; Hu, W. Neurofilament light chain protein in neurodegenerative dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019, 102, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhauria, M.; Mondal, R.; Deb, S.; Shome, G.; Chowdhury, D.; Sarkar, S.; Benito-León, J. Blood-Based Biomarkers in Alzheimer's Disease: Advancing Non-Invasive Diagnostics and Prognostics. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 10911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eratne, D.; Kang, M.J.Y.; Lewis, C.; Dang, C.; Malpas, C.B.; Keem, M.; Grewal, J.; Marinov, V.; Coe, A.; Kaylor-Hughes, C.; Borchard, T.; Keng-Hong, C.; Waxmann, A.; Saglam, B.; Kalincik, T.; Kanaan, R.; Kelso, W.; Evans, A.; Farrand, S.; Loi, S.; Walterfang, M.; Stehmann, C.; Li, Q.X.; Collins, S.; Masters, C.L.; Santillo, A.F.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Berkovic, S.F.; Velakoulis, D.; MiND Study Group. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light chain distinguish neurodegenerative from primary psychiatric conditions in a clinical setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 7989–8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hol, E.M.; Pekny, M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the astrocyte intermediate filament system in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015, 32, 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhak, A.; Foschi, M.; Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Yue, J.K.; D'Anna, L.; Huss, A.; Oeckl, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Kuhle, J.; Petzold, A.; Manley, G.T.; Green, A.J.; Otto, M.; Tumani, H. Blood GFAP as an emerging biomarker in brain and spinal cord disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022, 18, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.B.; Janelidze, S.; Smith, R.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Teunissen, C.E.; Zetterberg, H.; Stomrud, E.; Ashton, N.J.; Blennow, K.; Hansson, O. Plasma GFAP is an early marker of amyloid-β but not tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2021, 144, 3505–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pilotto, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Lupini, A.; Battaglio, B.; Zatti, C.; Trasciatti, C.; Gipponi, S.; Cottini, E.; Grossi, I.; Salvi, A.; de Petro, G.; Pizzi, M.; Canale, A.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Padovani, A. Plasma NfL, GFAP, amyloid, and p-tau species as Prognostic biomarkers in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2024, 271, 7537–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ammitzbøll, C.; Dyrby, T.B.; Börnsen, L.; Schreiber, K.; Ratzer, R.; Romme Christensen, J.; Iversen, P.; Magyari, M.; Lundell, H.; Jensen, P.E.H.; Sørensen, P.S.; Siebner, H.R.; Sellebjerg, F. NfL and GFAP in serum are associated with microstructural brain damage in progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023, 77, 104854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korley, F.K.; Jain, S.; Sun, X.; Puccio, A.M.; Yue, J.K.; Gardner, R.C.; Wang, K.K.W.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Yuh, E.L.; Mukherjee, P.; Nelson, L.D.; Taylor, S.R.; Markowitz, A.J.; Diaz-Arrastia, R. ; Manley GT; TRACK-TBI Study Investigators. Prognostic value of day-of-injury plasma GFAP and UCH-L1 concentrations for predicting functional recovery after traumatic brain injury in patients from the US TRACK-TBI cohort: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Milà-Alomà, M.; Ashton, N.J.; Shekari, M.; Salvadó, G.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Montoliu-Gaya, L.; Benedet, A.L.; Karikari, T.K.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Vanmechelen, E.; Day, T.A.; González-Escalante, A.; Sánchez-Benavides, G.; Minguillon, C.; Fauria, K.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Dage, J.L.; Zetterberg, H.; Gispert, J.D.; Suárez-Calvet, M.; Blennow, K. Plasma p-tau231 and p-tau217 as state markers of amyloid-β pathology in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1797–1801, Erratum in: Nat Med. 2022, 28, 1965. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02037-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Portera, A.; Franch, O.; Del Ser, T. Neuromuscular manifestations of the Toxic Oil Syndrome. In: Battistin, L.; Hashim, G.; Lajtha, A.; editors. Clinical and biological aspects of the peripheral nervous diseases. New York: Alan, R. Liss; 1983. p. 171-181.

- Ladona, M.G.; Izquierdo-Martinez, M.; Posada de la Paz, M.P.; de la Torre, R.; Ampurdanés, C.; Segura, J.; Sanz, E.J. Pharmacogenetic profile of xenobiotic enzyme metabolism in survivors of the Spanish toxic oil syndrome. Environ Health Perspect. 2001, 109, 369–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arranz, J.; Zhu, N.; Rubio-Guerra, S.; Rodríguez-Baz, Í.; Ferrer, R.; Carmona-Iragui, M.; Barroeta, I.; Illán-Gala, I.; Santos-Santos, M.; Fortea, J.; Lleó, A.; Tondo, M.; Alcolea, D. Diagnostic performance of plasma pTau217, pTau181, Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 in the LUMIPULSE automated platform for the detection of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024, 16, 139, Erratum in: Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024, 16, 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-024-01538-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rissin, D.M.; Kan, C.W.; Campbell, T.G.; Howes, S.C.; Fournier, D.R.; Song, L.; Piech, T.; Patel, P.P.; Chang, L.; Rivnak, A.J.; Ferrell, E.P.; Randall, J.D.; Provuncher, G.K.; Walt, D.R.; Duffy, D.C. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 595–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quanterix Corporation. SIMOA GFAP Discovery Kit HD-1/HD-X: Data Sheet. Rev03. Billerica (MA): Quanterix; 2020. Available from: https://www.quanterix.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Simoa_GFAP_Data_Sheet_HD-1_HD-X_Rev03.

- Arcaro, M.; Fenoglio, C.; Serpente, M.; Arighi, A.; Fumagalli, G.G.; Sacchi, L.; Floro, S.; D'Anca, M.; Sorrentino, F.; Visconte, C.; Perego, A.; Scarpini, E.; Galimberti, D. A Novel Automated Chemiluminescence Method for Detecting Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid-Beta 1-42 and 1-40, Total Tau and Phosphorylated-Tau: Implications for Improving Diagnostic Performance in Alzheimer's Disease. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujirebio Europe, N.V. LUMIPULSE G600II: High-throughput immunoassay analyzer [Internet]. Ghent (Belgium): Fujirebio. Available online: https://www.fujirebio.com/en/products-solutions/lumipulse-g600ii (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Ball, N.; Teo, W.P.; Chandra, S.; Chapman, J. Parkinson's Disease and the Environment. Front Neurol. 2019, 10, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldman, S.M. Environmental toxins and Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014, 54, 141–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Zafar, M.; Lettenberger, S.E.; Pawlik, M.E.; Kinel, D.; Frissen, M.; Schneider, R.B.; Kieburtz, K.; Tanner, C.M.; De Miranda, B.R.; Goldman, S.M.; Bloem, B.R. Trichloroethylene: An Invisible Cause of Parkinson's Disease? J Parkinsons Dis. 2023, 13, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdelhak, A.; Antweiler, K.; Kowarik, M.C.; Senel, M.; Havla, J.; Zettl, U.K.; Kleiter, I.; Skripuletz, T.; Haarmann, A.; Stahmann, A.; Huss, A.; Gingele, S.; Krumbholz, M.; Benkert, P.; Kuhle, J.; Friede, T.; Ludolph, A.C.; Ziemann, U.; Kümpfel, T.; Tumani, H. Serum glial fibrillary acidic protein and disability progression in progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2024, 11, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).