Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

First Stage: Scoping Review

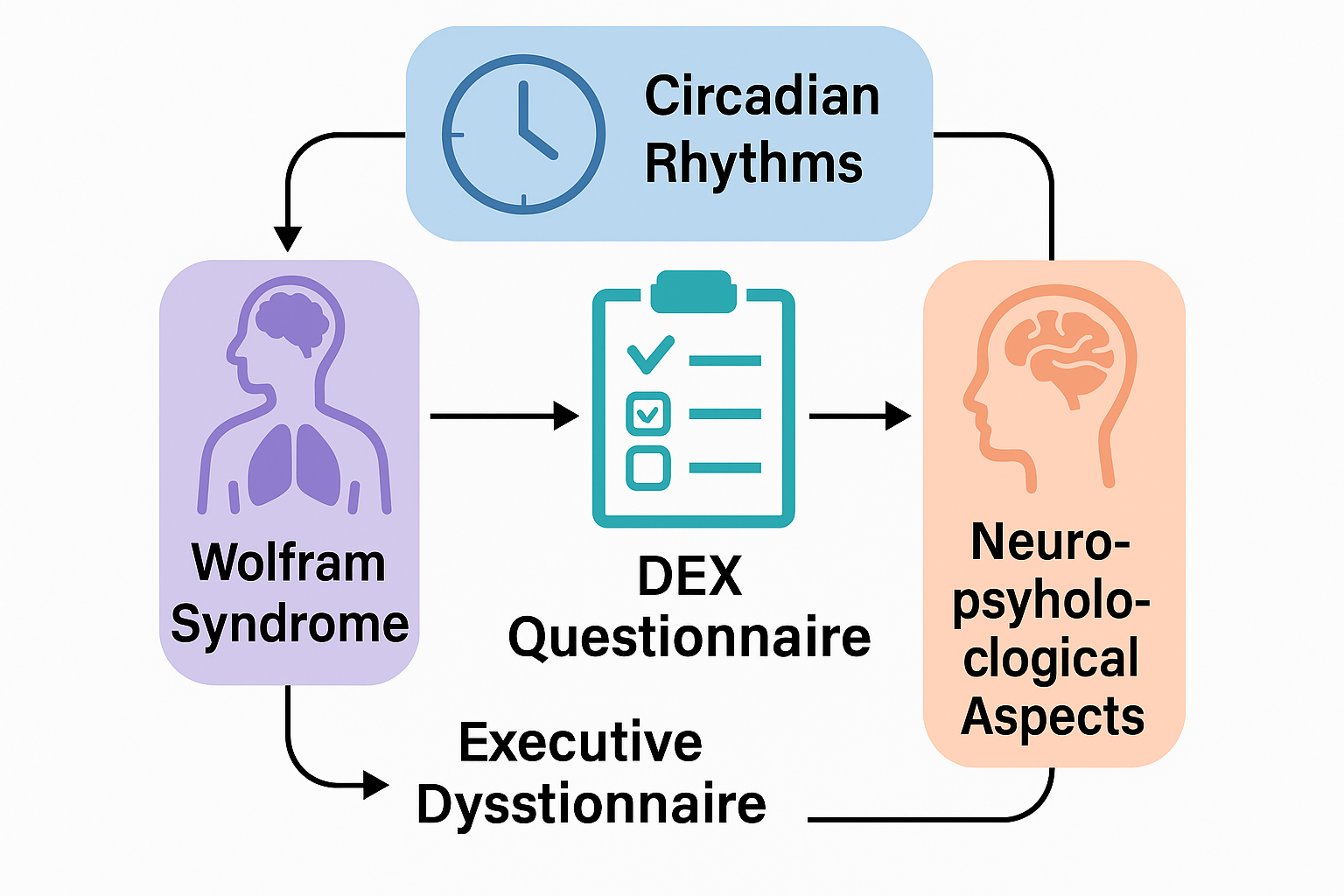

Second Stage – Evaluation of Executive Functions Using DEX

Results

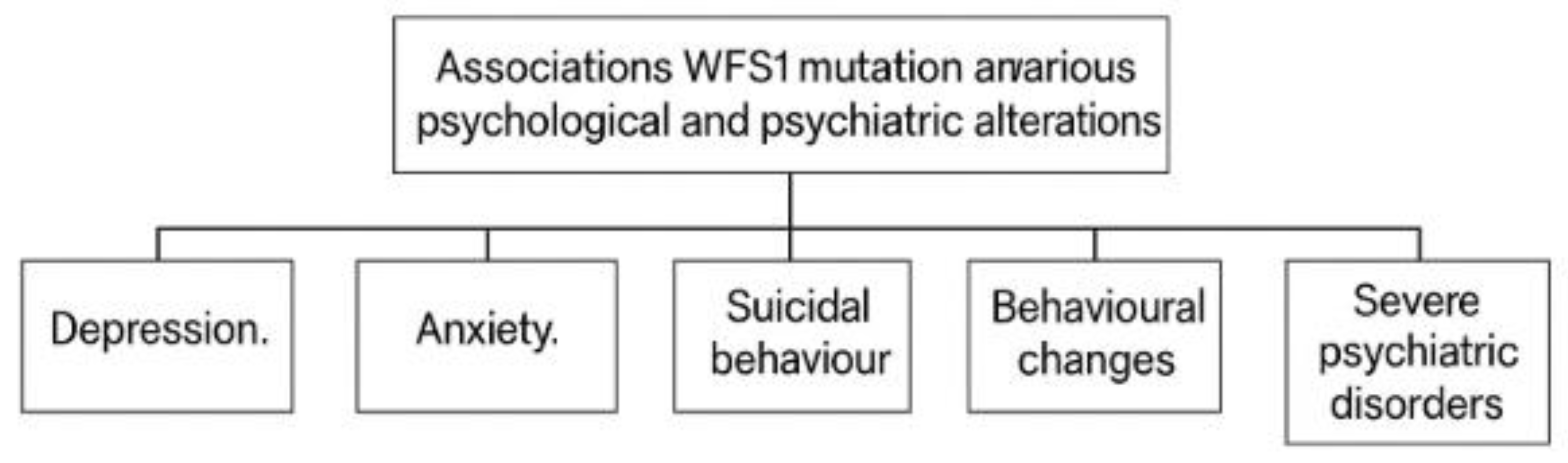

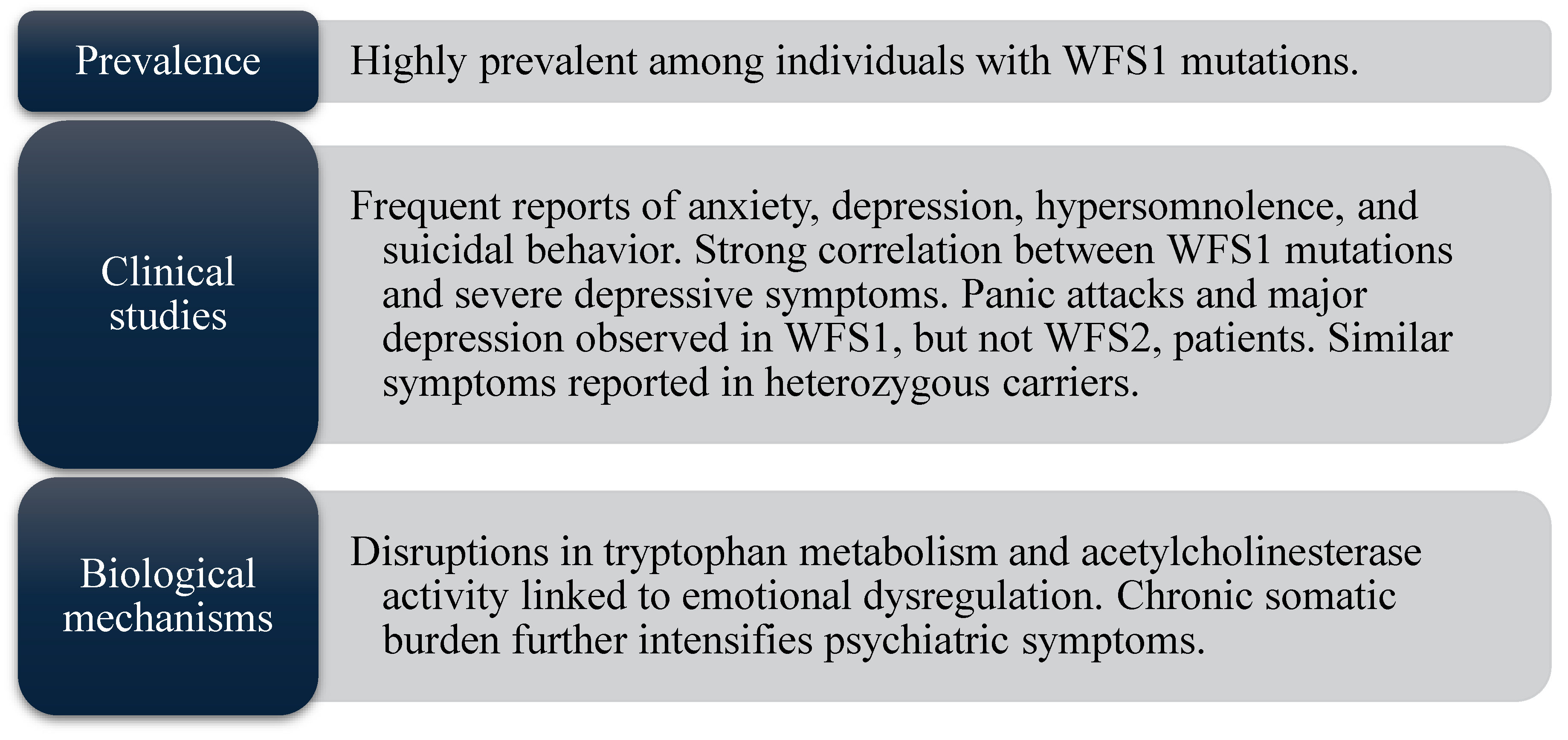

Functional Category 1 – Anxiety and Depression Disorders

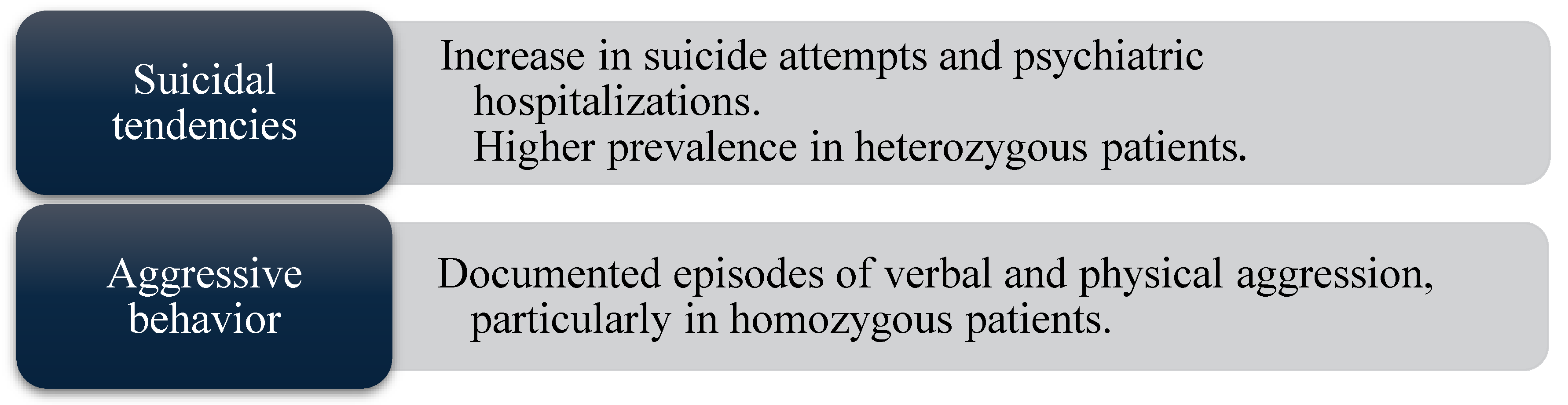

Functional Category 2 - Suicidal and Aggressive Behaviors

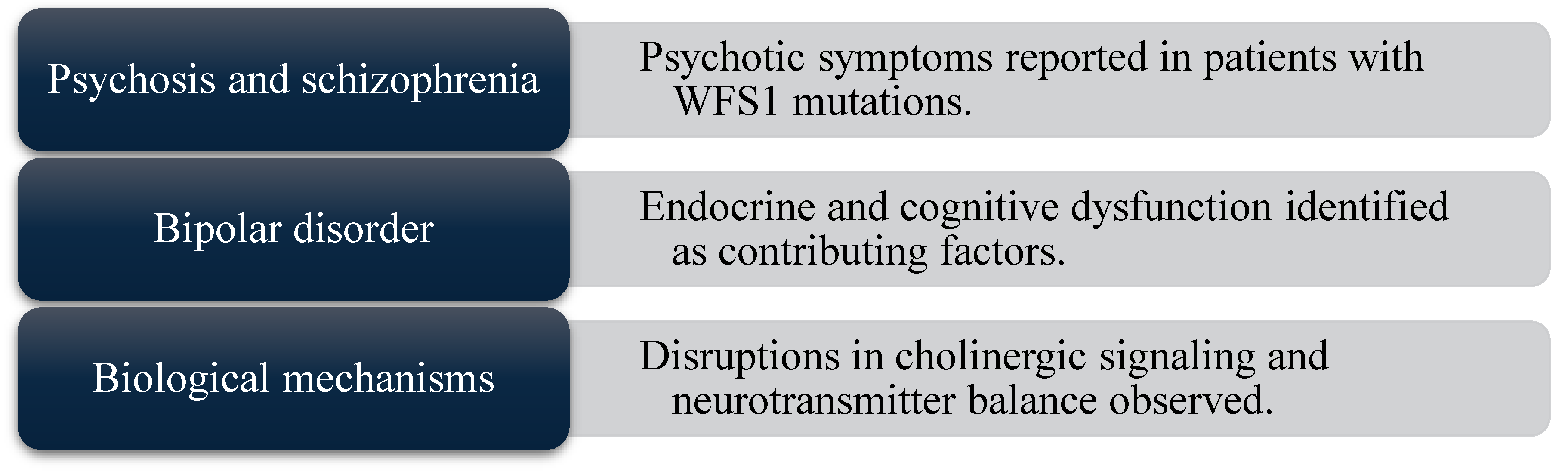

Functional category 3 - Severe Psychological and Psychiatric Disorders

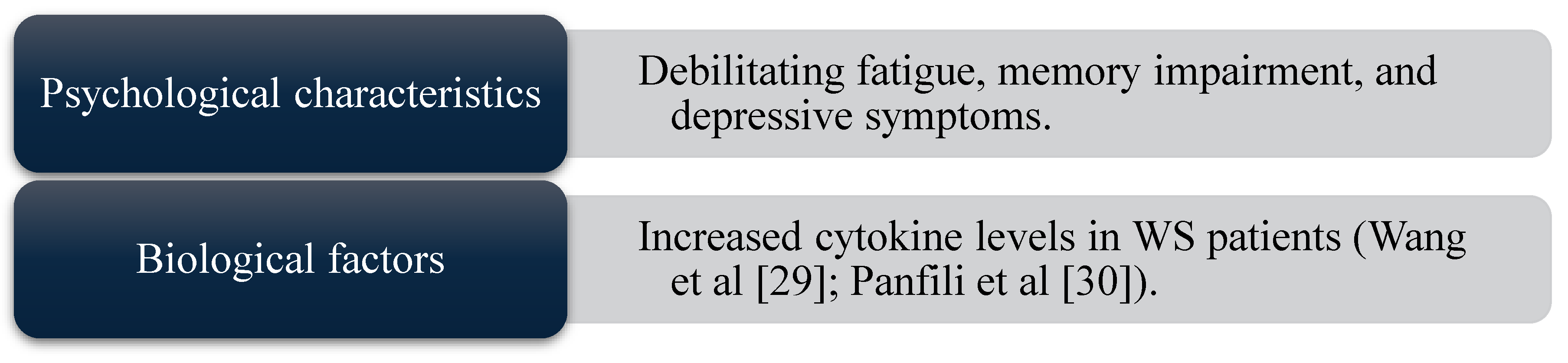

Functional Category 4 – Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Impact of Hypogonadism

Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Author information

Ethical Standards

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Esteban Bueno G, Fernández Martínez JL. Gonadal Dysfunction in Wolfram Syndrome: A Prospective Study. Diagnostics. 2025;15:1594. [CrossRef]

- Hardy C, Khanim F, Torres R, Scott-Brown M, Seller A, Poulton J, Collier D, Kirk J, Polymeropoulos M, Latif F, Barrett T. Clinical and molecular genetic analysis of 19 Wolfram syndrome kindreds demonstrating a wide spectrum of mutations in WFS1. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(5):1279–1290. [CrossRef]

- Bueno GE, Ruiz-Castañeda D, Martínez JR, Muñoz MR, Alascio PC. Natural history and clinical characteristics of 50 patients with Wolfram syndrome. Endocrine. 2018;61(3):440–446. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Bueno G, Berenguel Hernández AM, Fernández Fernández N, Navarro Cabrero M, Coca JR. Neurosensory Affectation in Patients Affected by Wolfram Syndrome: Descriptive and Longitudinal Analysis. Healthcare. 2023;11(13):1888. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff AN, Reiersen AM, Buttlaire A, Al-Lozi A, Doty T, Marshall BA, Hershey T; Washington University Wolfram Syndrome Research Group. Selective cognitive and psychiatric manifestations in Wolfram Syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:66. [CrossRef]

- Swift RG, Sadler DB, Swift M. Psychiatric findings in Wolfram syndrome homozygotes. Lancet. 1990;336(8721):667–669. [CrossRef]

- Reiersen AM, Noel JS, Doty T, Sinkre RA, Narayanan A, Hershey T. Psychiatric Diagnoses and Medications in Wolfram Syndrome. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. 2022;10(1):163–174. [CrossRef]

- Swift M, Gorman Swift R. Psychiatric disorders and mutations at the Wolfram syndrome locus. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(9):787–793. [CrossRef]

- Wilson BA, Alderman N, Burgess PW, Emslie H, Evans JJ. Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome. Thames Valley Test Company; 1996.

- Gerstorf D, Siedlecki KL, Tucker-Drob EM, et al. Executive dysfunctions across adulthood: Measurement properties and correlates of the DEX self-report questionnaire. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2008;15(4):424–445. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca SG, Fukuma M, Lipson KL, Nguyen LX, Allen JR, Oka Y, Urano F. WFS1 is a novel component of the unfolded protein response and maintains homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(47):39609–39615. [CrossRef]

- Hao X, Zhou Y, Park D, et al. Wolfram syndrome 1 regulates sleep in dopamine receptor neurons via ER-mediated calcium homeostasis. PLoS Genet. 2023;19(3):e1010827. [CrossRef]

- Ferreras C, Gorito V, Pedro J, et al. Wolfram syndrome: Portuguese research. Endokrynol Pol. 2021;72(4):353–356. [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbusch N, Löwe B, Depping MK. Correlates of depression and anxiety in patients with different rare diseases. J Psychosom Res. 2018;109:142. [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbusch N, Löwe B, Härter M, Schramm C, Weiler-Normann C, Depping MK, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with different rare chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211343. [CrossRef]

- Silva P, Cedres L, Vomero A, et al. Síndrome de Wolfram. Rev Esp Endocrinol Pediatr. 2019;10(2):74–80. [CrossRef]

- Pedrero Pérez EJ, Olivar Arroyo L, Morales Alonso S, et al. Versión española del Cuestionario de Disfunción Ejecutiva (DEX-Sp): propiedades psicométricas en población clínica. Rev Neurol. 2009;48(4):193–198. [CrossRef]

- Welschen D, Peralta C, Estela M, et al. Síndrome de Wolfram: reporte de casos. Oftalmol Clin Exp. 2015;8(1):29–38.

- Ferreira VFS, Campos CR, Furtado AM, et al. Wolfram syndrome: A case report. Res Soc Dev. 2021;10(6):e52410616116. [CrossRef]

- Nanko S, Yokoyama H, Hoshino Y, et al. Organic mood syndrome in two siblings with Wolfram syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Swift RG, Perkins DO, Chase CL, et al. Psychiatric disorders in 36 families with Wolfram syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Xavier J, Bourvis N, Tanet A, et al. Bipolar Disorder Type 1 in a 17-Year-Old Girl with Wolfram Syndrome. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee SS, Mitra S, Pal SK. Mania in Wolfram’s disease: From bedside to bench. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira A, Kim C, Seguin M, et al. Wolfram syndrome and suicide: Evidence for a role of WFS1 in suicidal and impulsive behavior. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003;119B(1):108–113. [CrossRef]

- Nickl-Jockschat T, Kunert HJ, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with Wolfram syndrome caused by a combination of thalamic deficit and endocrinological pathologies. Neurocase. [CrossRef]

- Swift M, Gorman Swift R. Wolframin mutations and hospitalization for psychiatric illness. Mol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Owen, MJ. Psychiatric disorders in Wolfram syndrome heterozygotes. Mol Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Rigoli L, Caruso V, Aloi C, Salina A, Maghnie M, d'Annunzio G, et al. An Atypical Case of Late-Onset Wolfram Syndrome 1 without Diabetes Insipidus. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Kitamura RA, Maxwell KG, Ye W, et al. Multidimensional analysis and therapeutic development using patient iPSC-derived disease models of Wolfram syndrome. JCI Insight. 2022;7(18):e156549. [CrossRef]

- Rosanio FM, Di Candia F, Occhiati L, et al. Wolfram Syndrome Type 2: A Systematic Review of a Not Easily Identifiable Clinical Spectrum. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):1–12. [CrossRef]

- Cairns G, Burté F, Price R, O’Connor E, Toms M, Mishra R, Moosajee M, Pyle A, Sayer JA, Yu-Wai-Man P.A mutant wfs1 zebrafish model of Wolfram syndrome manifesting visual dysfunction and developmental delay. Sci Rep. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Wang X, Shi L, et al. Wolfram syndrome 1b mutation suppresses Mauthner-cell axon regeneration via ER stress signal pathway. Acta Neuropathol Commun. [CrossRef]

- Panfili E, Mondanelli G, Orabona C, Belladonna ML, Gargaro M, Fallarino F, et al. Novel mutations in the WFS1 gene are associated with Wolfram syndrome and systemic inflammation. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30(3–4):265–276. [CrossRef]

- de Muijnck C, Brink JBT, Bergen AA, Verhagen M, van Genderen MM, van den Born LI, et al. Delineating Wolfram-like syndrome: A systematic review and discussion of the WFS1-associated disease spectrum. Surv Ophthalmol. [CrossRef]

- Salzano G, Rigoli L, Valenzise M. Clinical Peculiarities in a Cohort of Patients with Wolfram Syndrome 1. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Reiersen AM, Noel JS, Doty T, Cox CL, Hershey T, Swift RG, et al. Psychiatric Diagnoses and Medications in Wolfram Syndrome. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Pedrero EJ, Ruiz JM, Rojo G, et al. Versión española del Cuestionario Disejecutivo (DEX-Sp): propiedades psicométricas en adictos y población no clínica. Adicciones.

- Hershey T, Lugar HM, Shimony JS, Nebes RD, Sadler B, Perantie DC, et al. Early brain vulnerability in Wolfram syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40604. [CrossRef]

- Shi G, Cui L, Chen R, Liang S, Wang C, Wu P, et al.. TT01001 attenuates oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis by preventing mitoNEET-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Neuroreport. [CrossRef]

- Morikawa S, Blacher L, Onwumere C, Akeju Y, Merali S, Woldeyohannes L, et al. Loss of Function of WFS1 Causes ER Stress-Mediated Inflammation in Pancreatic Beta-Cells. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:849204. [CrossRef]

- Low RN, Low RJ, Akrami A. A review of cytokine-based pathophysiology of Long COVID symptoms. Front Med. 2023;10:1011936. [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, JS. Cognitive impairment in Huntington disease: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. [CrossRef]

- Orellana G, Slachevsky A. Executive functioning in schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Szablewski, L. Associations Between Diabetes Mellitus and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Caruso V, Rigoli L. Beyond Wolfram Syndrome 1: The WFS1 Gene's Role in Alzheimer's Disease and Sleep Disorders. Biomolecules. 2024;14(11):1389. [CrossRef]

- Quittner AL, Goldbeck L, Abbott J, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers. Thorax. 2014;69(12):1090–1097. [CrossRef]

- Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ, Butler MG, Hanchett JM, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med. [CrossRef]

- Visnapuu T, Raud S, Loomets M, Talvik T, Cheng L, Dierssen M, et al. Wfs1-deficient mice display altered function of serotonergic system and increased behavioral response to antidepressants. Front Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Michalsky, T. Metacognitive scaffolding for preservice teachers' self-regulated design of higher order thinking tasks. Heliyon. 2024;10(2):e24280. [CrossRef]

- Mirhosseini S, Imani Parsa F, Moghadam-Roshtkhar H, Jafari P, Peivandi S, Lotfi M, et al. Support based on psychoeducation intervention to address quality of life and care burden among caregivers of patients with cancer. Front Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Pozuelos JP, Combita LM, Abundis A, Martínez MJ, Valero B, Soto N, et al. Metacognitive scaffolding boosts cognitive and neural benefits following executive attention training in children. Dev Sci. [CrossRef]

- Atkins JC, Padgett CR. Living with a Rare Disease: Psychosocial Impacts for Parents and Family Members – a Systematic Review. J Child Fam Stud. [CrossRef]

- Majander A, Jurkute N, Burté F, Brock K, João C, Huang H, Neveu MM, Chan CM, Duncan HJ, Kelly S, Burkitt-Wright E, Khoyratty F, Lai YT, Subash M, Chinnery PF, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Arno G, Webster AR, Moore AT, Michaelides M, Stockman A, Robson AG, Yu-Wai-Man P. WFS1-Associated Optic Neuropathy: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations and Disease Progression. Am J Ophthalmol. [CrossRef]

| Database | Documents Retrieved | Meeting Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria |

| Scopus | 843 | 8 |

| Web of Science | 672 | 6 |

| Dialnet | 116 | 5 |

| PsycInfo | 36 | 2 |

| PsicoDoc | 29 | 1 |

| ScienceDirect | 125 | 5 |

| Total | 1821 | 27 |

| TITLE | AUTHORS AND YEAR |

| Selective cognitive and psychiatric manifestations in Wolfram Syndrome | Bischoff, A.N.; Reiersen, A.M.; Butterfire, A. et al. (2015) [5] |

| Psychiatric diagnoses and treatment in Wolfram Syndrome | Reiersen, A.M.; Narayanan, A.; Sinkre, R.A. et al. (2019) [7] |

| Psychiatric findings in Wolfram syndrome homozygotes | Swift, R.G.; Sadler, D.B.; Swift M. (1990) [11] |

| Psychiatric Disorders and Mutations at the Wolfram Syndrome Locus | Swift, M.; Gorman Swift, R. (2000) [8] |

| Depression and anxiety in patients with different rare chronic diseases: A cross-sectional study | Uhlemusch, N.; Löwe, B.; Harter, M. et al. (2019) [15] |

| Correlates of depression and anxiety in patients with different rare diseases | Uhlemusch, N.; Löwe, B.; Depping, M.K. (2018) [14] |

| Síndrome de Wolfram | Silva, P., Cedres, L., Vomero, A., et al. (2019). [16] |

| Síndrome de Wolfram: reporte de casos | Welschen, D.; Peralta, C.; et al. (2015) [18] |

| Síndrome de Wolfram - Relato de caso | Ferreira, V. F. S., Campos, C. R., Furtado, A. M., et al. (2021). [19] |

| Organic mood syndrome in two siblings with Wolfram syndrome | Nanko, S., Yokoyama, H., Hoshino, Y., et al. (1992). [20] |

| Psychiatric disorders in 36 families with Wolfram syndrome | Swift, R. G., Perkins, D. O., Chase, C. L., Sadler, D. B., & Swift, M. (1991). [21] |

| Bipolar Disorder Type 1 in a -Year-Old Girl with Wolfram Syndrome | Xavier, J., Bourvis, N., Tanet, A. et al. (2016) [22] |

| Mania in wolfram’s disease: From bedside to bench | Chatterjee, S. S., Mitra, S., & Pal, S. K. (2017). [23] |

| Wolfram Syndrome and Suicide: Evidence for a Role of WFS1 in Suicidal and Impulsive Behavior | Sequeira, A., Kim, C., Seguin, M., et al. (2003). [24] |

| Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with Wolfram syndrome caused by a combination of thalamic deficit and endocrinological pathologies | Nickl-Jockschat, T., Kunert, H. J., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., et al. (2009). [25] |

| Wolframin mutations and hospitalization for psychiatric illness | Swift, M., & Gorman Swift, R. (2005). [26] |

| Psychiatric disorders in Wolfram syndrome heterozygotes | Owen, M. J. (1998). [27] |

| An Atypical Case of Late-Onset Wolfram Syndrome 1 without Diabetes Insipidus | Rigoli, L., Caruso, V., Aloi, C., et al. (2022). [28] |

| Multidimensional analysis and therapeutic development using patient iPSC–derived disease models of Wolfram syndrome | Kitamura, R. A., Maxwell, K. G., Ye, W., et al. (2022). [29] |

| Wolfram Syndrome Type 2: A Systematic Review of a Not Easily Identifiable Clinical Spectrum | Rosanio, F. M., Di Candia, F., Occhiati, L., et al. (2022) [30] |

| A mutant wfs1 zebrafish model of Wolfram syndrome manifesting visual dysfunction and developmental delay | Cairns, G., Burté, F., Price, R., et al. (2021) [31] |

| Wolfram syndrome 1b mutation suppresses Mauthner-cell axon regeneration via ER stress signal pathway | Wang, Z., Wang, X., Shi, L., et al. (2022) [32] |

| Novel mutations in the WFS1 gene are associated with Wolfram syndrome and systemic inf lammation | Panfili, E., Mondanelli, G., Orabona, C., et al. (2021). [33] |

| Delineating Wolfram-like syndrome: A systematic review and discussion of the WFS1 -associated disease spectrum | de Muijnck, C., Brink, J. B. T., Bergen, A. A., et al. (2023). [34] |

| Clinical Peculiarities in a Cohort of Patients with Wolfram Syndrome 1 | Salzano, G., Rigoli, L., Valenzise, M. (2022). [35] |

| Psychiatric Diagnoses and Medications in Wolfram Syndrome | Reiersen, A.M., Noel, J.S., Doty, T., et al. (2022). [36] |

| Wolfram syndrome: Portuguese research | Ferreras, C., Gorito, V., Pedro, J., et al. (2021). [13] |

| CATEGORY | SUMMARY | REFERENCES |

| Associated psychiatric disorders | Includes the presence of psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. These studies examine potential biological, genetic, and neurological links. | [5,6,7,8,27,36] |

| Mood and behavioral disorders | Covers mood disturbances (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder) and behavioral symptoms (e.g., impulsivity, suicidal behavior), and their relation to clinical or neurological features. | [20,22,23,24] |

| Cognitive and neurological aspects | Addresses cognitive deficits, neurodegeneration, and neuropsychiatric changes in WS, and their impact on daily function and disease progression. | [24,26] |

| Anxiety and depression disorders | Examines anxiety and depressive disorders in individuals with Wolfram Syndrome and other rare diseases, focusing on the psychological burden of chronic progressive conditions. | [13,14] |

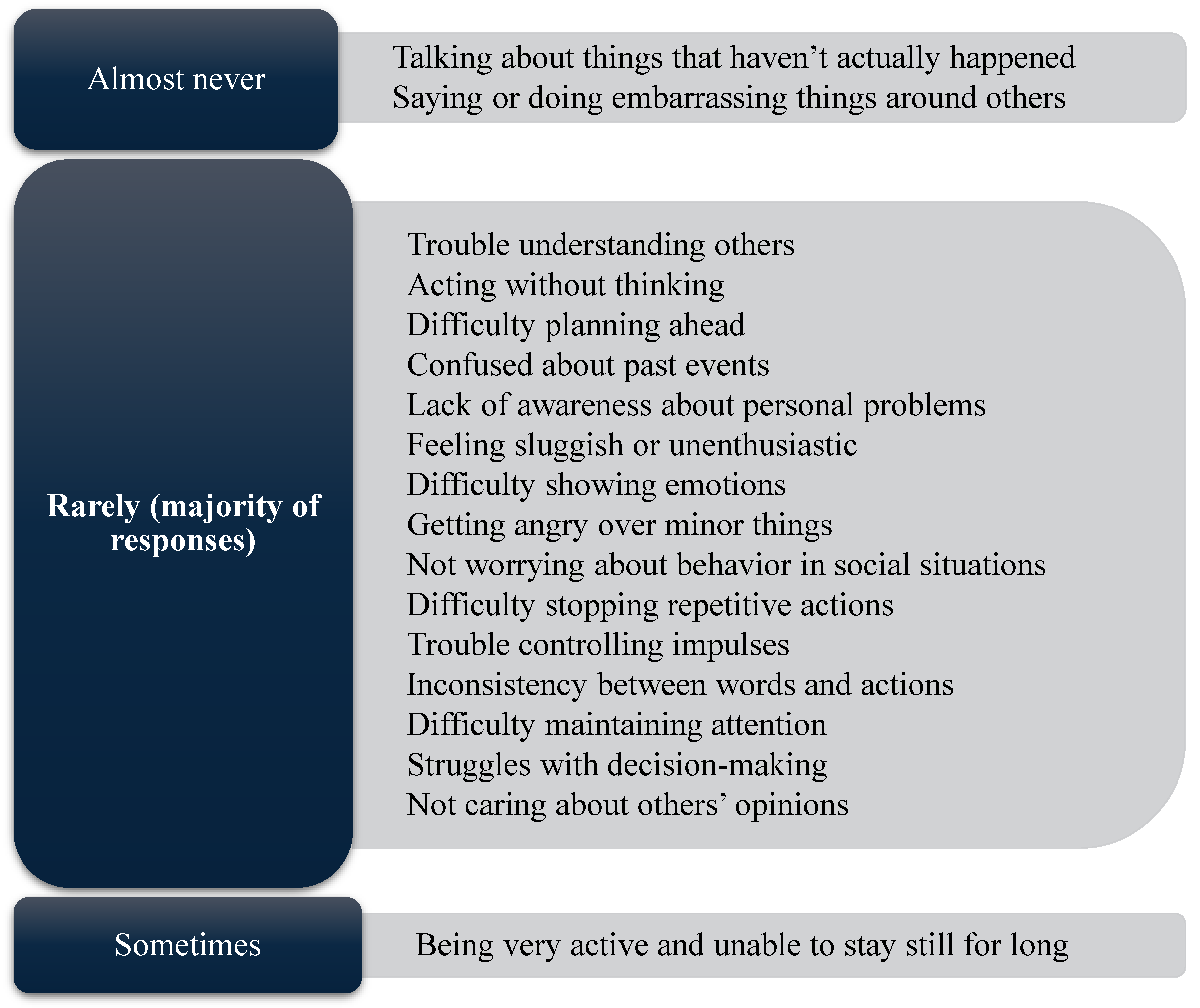

| Question | Executive dimension | Mean | Range |

| 15 | Hyperactivity and restlessness | 2.8 | [2.29-3.57] |

| 18 | Difficulties in maintaining attention | 2.27 | [1.71-3.29] |

| 2 | Impulsivity (acting without thinking) | 2.05 | [1.57-2.86] |

| 8 | Lack of enthusiasm/apathy | 2.03 | [1.36-2.82] |

| 17 | Inconsistency between what is said and what is done | 1.99 | [1.57-2.57] |

| 11, 12, 14, 19 | Difficulty in showing emotions, anger, repetitive behaviors, indecisiveness | ≈1.98 | [1.36-2.45] |

| Question | Executive dimension | Mean | Range |

| 9 | Embarrassing behavior towards others | 1.3 | [1.00-1.82] |

| 3 | Confusion with reality (false memories) | 1.49 | [1.27-1.88] |

| 4 | Future planning | 1.69 | [1.29-2.00] |

| 6 | Confusion between events | 1.72 | [1.21-2.55] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).