Introduction

There is growing evidence that suggests a compelling link between cognitive impairment and dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and increased mortality risks in older people [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A critical aspect of this link is the role of episodic memory impairment, which is a hallmark of AD, one of the earliest domains to decline and related to an increased risk of mortality [

1,

5].

In large population studies, assessing episodic memory through extensive testing is impractical due to the time-consuming nature of these tests. Therefore, alternative methods that offer a quicker and more practical approach to evaluating episodic memory are essential in these research contexts. Given these constraints, the simplicity of the Mini-Mental State Examination's (MMSE) three-word recall task emerges as a more practical tool. This task offers a faster and more efficient way to measure episodic memory, particularly in large-scale studies [

1,

5,

6]. Also, its proven ability to predict mortality and dementia offers a practical yet effective tool for large-scale epidemiological studies [

1,

5]. In the MMSE's three-word recall task, the patient is asked to remember and later recall three unrelated words.

ET patients generally have poor performance on language, verbal and visual memory, and frontal executive function tests [

7,

8,

9], and these cognitive changes are associated with more functional difficulty [

10]. These changes are not static and can worsen significantly [

11,

12]. Specifically, several extensive epidemiological studies have demonstrated an association between ET with mild cognitive impairment and dementia [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], including AD [

14]. A postmortem investigation revealed that ET patients accumulate amyloid-β in the cerebellar cortex [

19]. In another study, cognitively unimpaired ET patients and those with mild cognitive impairment had more hyperphosphorylated forms of the microtubule-associated protein tau in neurofibrillary tangles in the neocortex than their non-ET counterparts [

20]. These findings suggest a possible link between ET and the neuropathological hallmarks of AD, highlighting the need for further research into the neurological underpinnings and potential cognitive implications of ET. In addition, the risk of incident dementia was found to be higher in individuals with ET in two separate population-based studies (one in Spain and the other in New York) [

15,

16].

A significant gap remains in our understanding of the relationship between ET and mortality. Only a paucity of studies (especially prospective population-based studies) explicitly focused on the mortality risk among ET patients [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Cognitive impairments in ET, particularly in episodic memory [

25,

26], mirror those observed in the early stages of AD [

7,

8,

9].

We aimed to bridge this gap using the Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) cohort. By focusing on the MMSE-37’s three-word recall task to assess episodic memory in older adults with ET [

1,

5,

6], we sought to elucidate the relationship between episodic memory impairment and mortality risk in this population. The study tested two hypotheses. Firstly, that poorer episodic memory performance in ET patients correlates with a higher mortality risk, and secondly, that ET patients with episodic memory impairments are at an increased risk of mortality from AD.

Methods

Study Population

The data for the current studies were obtained from the NEDICES study, a comprehensive, community-based research project examining the prevalence, incidence, and factors influencing primary conditions related to aging in the older population [

27,

28,

29]. Detailed accounts of the study population and sampling methods have been published elsewhere [

27,

28,

29].

Study Evaluation

During the initial (1994–1995) and follow-up (1997–1998) assessments, participants were interviewed with a questionnaire designed to gather information on demographic factors, medication use, medical history, smoking (ever vs. never), and drinker (ever/at least once per week vs. never) [

27,

28,

29]. A short questionnaire was mailed to subjects who refused or were unavailable for face-to-face interviews.

A 37-item Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-37) was administered to assess global cognition. This test is a Spanish adaptation of the standard MMSE [

30,

31], that essentially follows the original procedure of Folstein et al. [

32]. The delayed free recall task was conducted immediately following the attention assessment. The interval between registration and free recall tasks was about three minutes [

30,

31].

According to a comorbidity score developed in ambulatory care settings [

33], a comorbidity index was calculated [

33]. To assess sleep habits, each participant was asked to indicate their total hours of actual sleep in 24 hours (sum of nighttime sleep and daytime napping) [

34,

35].

One screening question for ET was included in the baseline (1994–1995) and follow-up assessment (1997–1998): “Have you ever suffered from a tremor of the head, hands, or legs that has lasted longer than several days?” [

36,

37].

Participants were considered a positive screening for ET if they answered “yes” to the screening question for ET [

36,

37]. The sensitivity of this screening question was evaluated by selecting and contacting a random sample of approximately 4% of subjects who had screened negative [

38]. Each of these subjects subsequently underwent a neurologic examination [

38]. During the neurologic examination, none of the 183 participants who tested negative at screening were found to have ET (sensitivity: 100%; negative predictive value: 100%) [

38].

At baseline and follow-up [

36,

37], participants who screened positive for ET underwent a neurologic evaluation by senior neurologists. The participants' medical records, which were unavailable for assessment, were sourced from various places. ET cases were initially identified by one neurologist and subsequently examined by two additional neurologists. Patients were classified as having ET only when all three neurologists reached a consensus, thereby minimizing the likelihood of initial diagnostic errors. The same rigorous methodology was applied during the second assessment (1997–1998) to ensure consistency in diagnostic criteria over time.

The diagnostic criteria for ET in this study, applied to both direct examinations and reviews of participants' medical records, were derived from the criteria used in the Sicilian Study [

39] and recommendations from the Movement Disorders Society Consensus [

40]. ET diagnosis was confirmed in participants exhibiting action tremors of the limbs or head, with no attributable alternative causes.

Among the 5,278 participants screened for ET from 1994 to 1995, 256 prevalent cases (4.8%) were identified [

36]. This prevalence rate aligns closely with other population-based estimates of ET prevalence in Western countries, underscoring the validity of the diagnostic criteria used in this study [

41].

We used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria to diagnose dementia [

42,

43,

44]

Mortality Data

Mortality data of the cohort were obtained until December 31, 2017. The Spanish National Population Register (

Instituto Nacional de Estadística in Spanish) provides the death dates. In Spain, the death certificates are issued by a physician at the time of death and then sent to the local municipal authority where the deceased resided, allowing the information to be recorded in the National Register. We coded the cause of death using the International Classification of Diseases—ICD- 10th Revision (

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10.htm). In cases where the death certificates specified dementia according to ICD-10th criteria, we conducted an in-depth review if there was a pre-existing clinical diagnosis of AD confirmed by NEDICES neurologists.

Final Selection of Study Participants

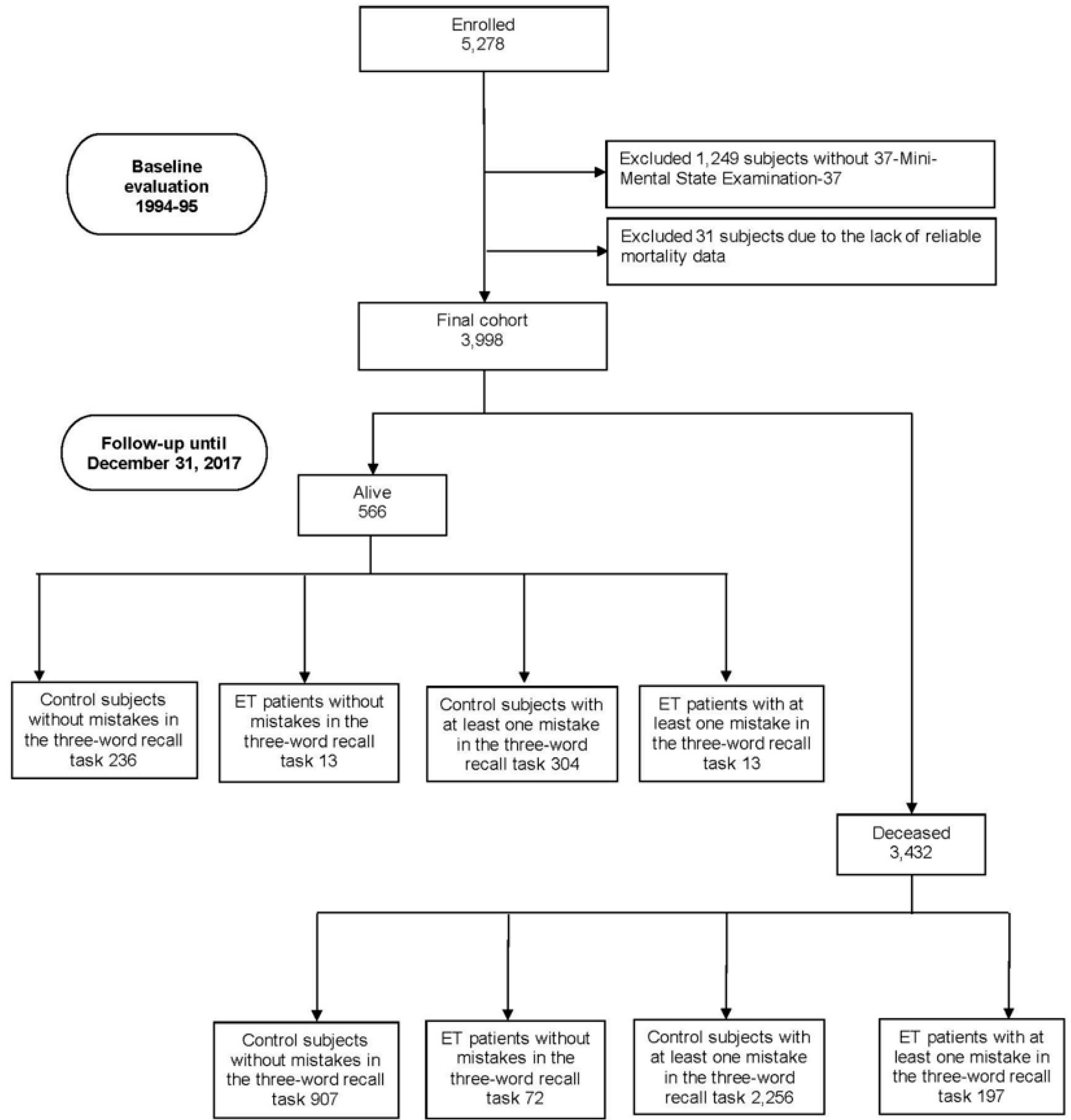

Of the 5,278 participants screened for neurological conditions at baseline (1994–1995), 1,249 (27.7%) had no MMSE-37 (including 34 prevalent ET cases—participants diagnosed with ET at baseline—and 8 ET premotor cases—participants identified with ET during the follow-up period but not at baseline—and 1,207 controls). Additionally, 31 participants (0.6%) (one prevalent ET case, one ET premotor case, and 29 controls) were excluded due to the lack of reliable mortality data, leaving 3,998 participants included in our analyses (

Figure 1). We compared the final 3,998 participants to the 1,280 excluded participants and found that the included participants were younger (73.7±6.7 [median=72] vs. 75.5±7.7 [median=74] years, Mann–Whitney test, p<0.001), a smaller proportion were women (2,047 [51.2%] vs. 704 [55.0%], chi-square [X²]=5.61, p=0.018), and they were more educated (562 [14.1%] vs. 146 [11.8%] had secondary or higher education, X²=31.35, p<0.001).

Of the 3,998 participants, 221 were identified as prevalent ET cases, 74 as ET premotor cases, and 3,703 as controls (participants who did not meet the criteria for ET during either the baseline screening or the follow-up period) [

36,

37]. Among the 221 prevalent ET cases, three (1.4%) had isolated head tremor, eight (3.6%) presented with both limb and voice tremor, 18 (8.1%) exhibited head and limb tremor, three (1.4%) had head, limb, and voice tremor, and the remaining 189 (85.5%) had isolated limb tremor. None of them exhibited other neurological signs, such as dystonic posturing, that would not suffice to make an additional syndrome diagnosis.

In the current study, we included premotor ET patients—those first diagnosed with ET at follow-up (1997–1998)—as part of the ET patient group. This approach aligns with emerging research suggesting that non-motor symptoms may represent an early or variant stage of motor ET [

12,

17,

45]. Previous studies support the idea of a progression from non-motor to motor symptoms in ET, indicating a continuum in the disease's manifestation [

12,

45]. Therefore, including premotor ET patients in the ET group is justified for the analysis, as it reflects the evolving understanding of ET's progression and spectrum [

12,

45].

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses for the study were conducted using SPSS software, version 29.0, and Python 3.12.2, with the packages pandas 2.2.2 and lifelines 0.29.0. All p values were two-tailed, and we considered p < 0.05 significant. Even after log transformation, continuous variables were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p<0.05). Therefore, we used Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis tests to analyze these continuous variables, whereas the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, when the expected frequencies in any cell were less than five, was used to analyze categorical variables.

Using the Cox proportional hazards models, we calculated the mortality hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (Cis). The time variable covered the period from the baseline assessment (1994–1995) to December 31, 2017, or the date of death, whichever came first.

We categorized participants based on their performance in the three-word recall task. They were divided into four groups: control subjects without mistakes in the three-word recall task (reference category in the Cox proportional-hazards models), ET patients without mistakes in the three-word recall task, control subjects with at least one mistake, and ET patients with at least one mistake. This classification allowed for a nuanced analysis of episodic memory performance across different groups, considering ET's presence and the memory task's accuracy. In each analysis, we began with an unadjusted model. In adjusted Cox proportional-hazards analyses, model 1 used a more restrictive approach considering all baseline variables that were associated (p < 0.05) with both the groups of exposure (controls and ET patients, stratified by the performance of the three-word recall task) and the outcome (death). After that, we considered baseline variables that were associated (p< 0.05) with either the exposure or the outcome in bivariate analyses (i.e., a less restrictive approach) (model 2).

Age (years), sex, educational level, sleep duration, smoker (ever smoker vs. never), consumption of ethanol (ever at least once per week vs. never), comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension were assessed at baseline and considered as potential covariates. Our comprehensive approach adjusted for all potential confounding factors in the analysis, irrespective of their statistical correlation with the exposure or outcome variables. This adjustment was made to ensure the robustness of our findings, encompassing factors that might not show a direct link but could influence the results (model 3).

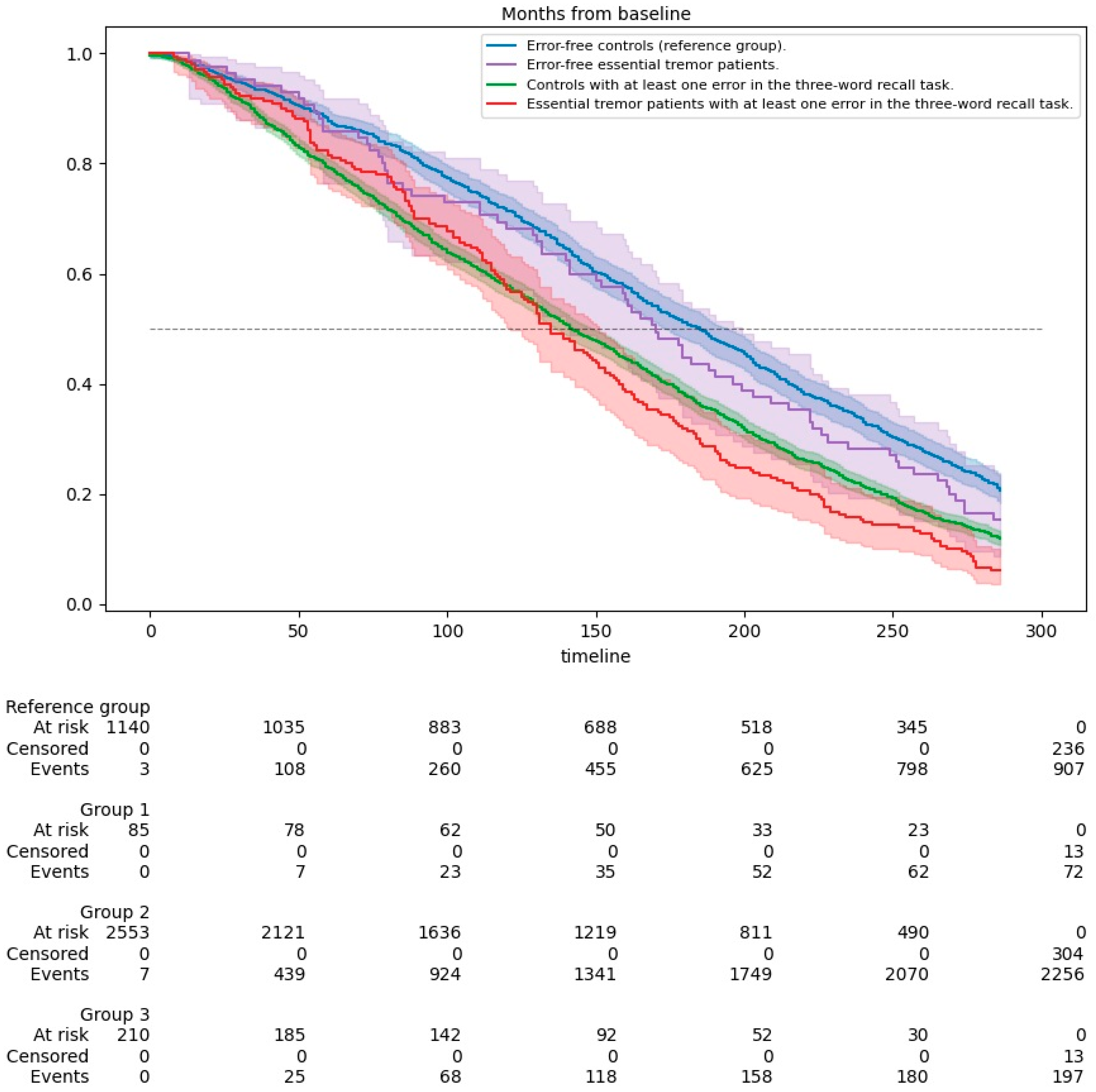

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were utilized to evaluate and compare the survival of ET patients and non-ET subjects based on their performance in the MMSE-37's three-word recall task. These groups were further divided based on whether they made any mistakes in the task. We used the log-rank test to compare the differences between the four survival curves, providing insights into the impact of ET and episodic memory performance on survival rates.

Additive interactions were assessed using the Relative Excess Risk due to Interaction (RERI), which measures deviation from additivity on the risk scale. A RERI of 0 indicates no interaction, while values above 0 suggest a positive interaction (combined effect exceeds the sum of individual effects), and values below 0 indicate a negative interaction (effect less than additivity) [

46].

Results

Of the 3,998 participants, 3,432 (85.8%) died over a median follow-up of 11.2 years (mean = 11.5 years; range=0.003–23.9 years). This included 907 deaths (79.3%) among the 1,143 control subjects without mistakes in the three-word recall task, 72 deaths (84.7%) among the 85 ET patients without mistakes, 2,256 deaths (88.1%) among the 2,560 control subjects with at least one mistake, and 197 deaths (93.8%) among the 210 ET patients with at least one mistake (

Figure 1). Notably, 210 out of 295 (71.2%) of ET patients demonstrated memory impairments, aligning with criteria for ET-plus [

47], which encompasses additional neurological features such as cognitive deficits.

We observed demographic and clinical characteristics differences among participants divided by ET status and cognitive function (measured by a three-word recall task). Specifically, variations were observed in age and educational attainment, with ET patients and those with recall task errors tending to be older and possessing lower education levels. Additionally, lifestyle factors such as sleep duration and smoking, as well as medical comorbidities, differed significantly among the groups (

Table 1).

Consistent with expectations, the analysis revealed that deceased individuals were notably older, with lower levels of education, longer sleep durations, a higher prevalence of smoking, and more medical comorbidities compared to their living counterparts, as detailed in

Table 2.

In an unadjusted Cox model, the mortality risk was increased in ET patients with at least one mistake in the three-word recall task (HR=1.65, 95% CI=1.41–1.93, p<0.001) and controls with at least one mistake (HR=1.42, 95% CI=1.32–1.54, p<0.001), but not in ET patients without any mistake (HR=1.15, 95% CI=0.91–1.47, p=0.239) vs those controls without any mistake (reference group). In a Cox regression model that incorporated adjustments for age in years, educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, and comorbidity index, i.e., variables that were associated with both the groups of exposure (controls and ET patients, stratified by the performance of the three-word recall task) and the outcome (death), the risk of mortality remained increased in ET patients with at least one mistake in the three-word recall task (HR=1.26, 95% CI = 1.08–1.48, p=0.004) and controls with at least one mistake (HR=1.19, 95% CI=1.10–1.29, p<0.001), Model 1 in

Table 3.

The findings remained consistent in a Cox regression model even after adjusting for variables that were linked with either the groups of exposure and the outcome (death) (baseline age in years, educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, ever drinker, comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension,) (Model 2 in

Table 3). The results were like a Cox model that adjusted for all the potential confounders (baseline age in years, sex, educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, ever drinker, comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension), independent of their statistical significance model 3 in

Table 3).

Mean survival times were derived from Kaplan-Meier estimates based on the baseline assessment (1994–1995).

Figure 2 illustrates the survival curves for the study groups, stratified by disease status (controls and ET patients) and performance on the three-word recall task. A lower survival rate was observed in groups with episodic memory impairments, as evidenced by the Log Rank (Mantel-Cox) test (χ² = 93.827, p<0.001). ET patients who made at least one mistake in the three-word recall task had slightly shorter survival times, with a median survival of 11.3 years (95% CI: 10.1–12.4) and a mean survival of 12.0 years (95% CI: 11.2–12.9), compared to ET patients without mistakes and controls (

Table 4)

When we limited our analyses to the 1,280 participants without MMSE-37 data, we observed no increased mortality risk among ET patients (unadjusted HR=0.89, 95% CI=0.64–1.23, p=0.479) compared to controls (reference group). This finding remained consistent across all adjusted models (1, 2, and 3) (data not shown).

In other analyses, we first excluded the dementia cases, and the results did not change (

Table 5), as did when we excluded the premotor ET patients (

Table 6).

Model 1: Adjusted for baseline age (years), educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, and comorbidity index.

Model 2: Adjusted for baseline age (years), educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, ever drinker, comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension.

Model 3: Adjusted for baseline age (years), sex, educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, ever drinker, comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension.

Model 1: Adjusted for baseline age (years), educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, and comorbidity index.

Model 2: Adjusted for baseline age (years), educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, ever drinker, comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension.

Model 3: Adjusted for baseline age (years), sex, educational level, sleep duration, ever smoker, ever drinker, comorbidity index, and arterial hypertension.

ET patients with memory impairments had a significantly higher AD-related mortality rate (5.1%) compared to those without memory impairments (1.4%, p=0.013). Similarly, controls with memory impairments also exhibited increased AD-related mortality (5.1%) compared to controls without memory impairments (2.7%). No significant differences were observed between ET patients and controls in mortality rates for other primary causes of death, such as cerebrovascular disorders, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, or cancer. These findings highlight the pivotal role of memory impairment in AD-related mortality, with ET status possibly amplifying this risk but not independently driving the association.

An additive interaction between ET and memory impairment was assessed using the RERI. The unadjusted RERI was 0.08 (95% CI: -0.32–0.48), and the adjusted RERI was 0.11 (95% CI: -0.21–0.43).

Discussion

Our study revealed that episodic memory impairments, assessed through errors in a word recall task, were significantly associated with increased mortality risk across all models. In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), ET patients with memory impairment had a moderately elevated hazard of mortality (HR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.07–1.46, p=0.006) compared to controls with memory impairment (HR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.09–1.28, p<0.001). Among those without memory impairments, ET patients did not exhibit a significant increase in mortality risk compared to controls (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.75–1.21, p=0.687).

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that ET patients with episodic memory impairments had survival trajectories slightly lower than those of controls with similar memory deficits. This finding suggests that episodic memory impairment, rather than ET, is the primary driver of the increased mortality risk, with ET potentially amplifying this effect. The RERI analysis further supports this conclusion, as no significant additive interaction was detected between ET and memory impairment. In the unadjusted model, the RERI was 0.08 (95% CI: -0.32 to 0.48), and in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), it was 0.11 (95% CI: -0.21 to 0.43). As both confidence intervals included 0, these findings were not statistically significant, indicating no evidence of a meaningful additive interaction.

These results suggest that the observed association likely reflects the independent contributions of the two factors. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better elucidate the interplay between ET, cognitive impairment, and mortality risk

The association between episodic memory impairments and increased mortality in ET patients warrants careful consideration, as it reflects the interplay of neurodegenerative processes, health management challenges, and functional decline. There is growing evidence suggesting that ET is associated with an increased likelihood of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD [

14,

15,

48,

49], which prominently features episodic memory loss. Cognitive impairments in ET, particularly episodic memory deficits, may signal the early stages of neurodegenerative processes that elevate mortality risk over time. This link is further supported by postmortem studies demonstrating a higher incidence of AD-type pathological changes in ET patients [

19,

20].

Additionally, memory impairment can adversely affect health management by compromising medication adherence, symptom recognition, and compliance with medical recommendations, leading to increased complications and poorer outcomes. Cognitive decline also contributes to functional impairments, greater frailty, and increased susceptibility to injuries and infections, further elevating mortality risk [

50].

Our results prompt the importance of understanding the diverse clinical characteristics of ET patients who develop cognitive impairments. The possible neurodegenerative nature of ET and its association with cognitive defects have been explored [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

49], highlighting the role of cerebellar dysfunction [

51]. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome spectrum, which includes attention, executive functions, and language impairments, is particularly relevant [

51,

52]. These observations highlight that ET affects a broad range of brain areas, not limited to those directly implicated in controlling tremor movements [

53,

54,

55]. Additionally, frontal lobe dysfunction and cognitive deficits observed in ET patients suggest a complex interplay between cerebellar-thalamo-cortical pathways and cognitive processes [

51,

56]. These insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of ET may offer potential therapeutic targets. Addressing cerebellar dysfunction and exploring interventions to modulate cerebellar-thalamo-cortical pathways could open new avenues for mitigating cognitive decline and potentially reducing mortality in ET patients [

55].

This study has limitations. The final sample of 4,029 excluded participants without MMSE-37 data. However, similar mortality risks in controls and ET cases without MMSE-37 data suggest these exclusions likely did not bias conclusions on the association between ET, episodic memory impairment, and mortality.

Secondly, relying solely on the MMSE's three-word recall task to assess episodic memory may have led to false positives or negatives, highlighting the need for more comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations to better capture ET patients' cognitive profiles. However, the MMSE’s simplicity makes it a practical tool for large-scale epidemiological studies [

1,

5,

6]. Adjustments for confounders such as dementia, psychiatric disorders, and educational level likely mitigated inaccuracies associated with this measure.

Thirdly, despite the rigorous consensus process involving three neurologists at baseline and follow-up to classify ET cases, some misclassification is inevitable, especially in long-term studies where conditions like Parkinson’s disease or dystonia may emerge. ET's association with other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s and progressive supranuclear palsy [

57,

58], further complicates diagnosis. Future research using advanced diagnostic tools, including biomarkers or postmortem analyses, could improve diagnostic accuracy and understanding of ET’s progression and comorbidities.

Finally, our reliance on death certificates to determine AD-related mortality introduces potential inaccuracies [

59] as clinical AD diagnoses are prone to misclassification without biomarkers or autopsy data [

60]. Other neurodegenerative diseases among deceased participants were not systematically accounted for, raising the possibility of coexisting or alternative conditions. While we reviewed clinical records to validate causes of death, the lack of neuropathological confirmation or biomarkers leaves some diagnostic uncertainty.

Despite these limitations, the study has several strengths. Firstly, the population-based design enabled the assessment of a broad, unselected group of older adults. Secondly, the standardized and prospective nature of the assessments reduced potential biases. Lastly, the study accounted for the confounding effects of various critical factors, enhancing the reliability of its findings.

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of episodic memory impairment in shaping health outcomes in older adults with ET. Memory deficits, a hallmark of AD, may reflect shared pathophysiological mechanisms or suggest that ET exacerbates cognitive vulnerabilities. The clinical heterogeneity of ET aligns with the concept of it being a family of diseases rather than a single disorder [

61]. Findings from the NEDICES study show that while ET does not universally increase mortality risk, it is significantly higher in ET patients with episodic memory impairments. This underscores the need for further research into the mechanisms linking ET to cognitive networks and memory, which could enhance understanding of its neurological impact and guide targeted interventions.

Author Contributions

J. Benito-León (jbenitol67@gmail.com) collaborated on 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project, 2) the statistical analysis design, and 3) the writing of the first draft of the manuscript. J. Lapeña-Motilva (joselapemo@gmail.com) collaborated on 1) the conception organization of the study and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. R. Ghosh (ritwikmed2014@gmail.com) collaborated on 1) the conception organization of the study and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. V. Giménez de Bejar (neuro.gimenezdebejar@gmail.com) collaborated on 1) the conception organization of the study and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. C. Benito-Rodríguez (carlaabeenito@gmail.com) collaborated on 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript. F. Bermejo-Pareja (felixbermejo006@gmail.com) collaborated on 1) the conception, organization, and execution of the research project and 2) the review and critique of the manuscript.

Funding

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011- 287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD—platform for the tracking of movement disorder), the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451) and The Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan at the Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant TED2021-130174B-C33, NETremor). The Spanish Health Research Agency and the Spanish Office of Science and Technology supported NEDICES. Information about collaborators and detailed funding of the NEDICES study can be found on the following webpage (https://www.ciberned.es/en/research-programmes/projects/nedices).

Conflicts of Interest

No specific funding was received for this work. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

References

- Villarejo, A.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Trincado, R. , et al. Memory impairment in a simple recall task increases mortality at 10 years in non-demented elderly. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2011, 26, 182–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contador, I.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Mitchell, A.J. , et al. Cause of death in mild cognitive impairment: a prospective study (NEDICES). Euro J of Neurology 2014, 21, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León, J.; Contador, I.; Mitchell, A.J.; Domingo-Santos, Á.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Performance on Specific Cognitive Domains and Cause of Death: A Prospective Population-Based Study in Non-Demented Older Adults (NEDICES). JAD 2016, 51, 533–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarejo, A.; Benito-León, J.; Trincado, R. , et al. Dementia-Associated Mortality at Thirteen Years in the NEDICES Cohort Study. JAD 2011, 26, 543–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazarán, J.; Trincado, R.; Bermejo, F.; Benito-León, J.; Díaz, J.; Vega, S. Selective memory impairment on an adapted Mini-Mental State Examination increases risk of future dementia. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2004, 19, 1173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcaillon, L.; Amieva, H.; Auriacombe, S.; Helmer, C.; Dartigues, J.-F. A Subtest of the MMSE as a Valid Test of Episodic Memory? Comparison with the Free and Cued Reminding Test. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2009, 27, 429–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Population-based case-control study of cognitive function in essential tremor. Neurology 2006, 66, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas-Martín, V.; Villarejo-Galende, A.; Fernández-Guinea, S.; Romero, J.P.; Louis, E.D.; Benito-León, J. A Comparison Study of Cognitive and Neuropsychiatric Features of Essential Tremor and Parkinson’s Disease. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 2016, 6, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafo, J.A.; Jones, J.D.; Okun, M.S.; Bauer, R.M.; Price, C.C.; Bowers, D. Memory Similarities Between Essential Tremor and Parkinson’s Disease: A Final Common Pathway? The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2015, 29, 985–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis ED, Benito-Leon J, Vega-Quiroga S, Bermejo-Pareja F, The Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group. Cognitive and motor functional activity in non-demented community-dwelling essential tremor cases. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2010, 81, 997–1001.

- Louis ED, Benito-León J, Vega-Quiroga S, Bermejo-Pareja F, the Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group. Faster rate of cognitive decline in essential tremor cases than controls: a prospective study. Euro J of Neurology 2010, 17, 1291–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León J, Louis ED, Sánchez-Ferro Á, Bermejo-Pareja F. Rate of cognitive decline during the premotor phase of essential tremor: A prospective study. Neurology 2013, 81, 60–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D.; Mitchell, A.J.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Elderly-Onset Essential Tremor and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Population-Based Study (NEDICES). JAD 2011, 23, 727–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Elderly-onset essential tremor is associated with dementia. Neurology 2006, 66, 1500–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Louis, E.D.; Benito-León, J. Risk of incident dementia in essential tremor: A population-based study. Movement Disorders 2007, 22, 1573–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thawani, S.P.; Schupf, N.; Louis, E.D. Essential tremor is associated with dementia: Prospective population-based study in New York. Neurology 2009, 73, 621–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J.; Contador, I.; Louis, E.D.; Cosentino, S.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Education and risk of incident dementia during the premotor and motor phases of essential tremor (NEDICES). Medicine 2016, 95, e4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radler KH, Zdrodowska MA, Dowd H, et al. Rate of progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in an essential tremor cohort: A prospective, longitudinal study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord.

- Béliveau E, Tremblay C, Aubry-Lafontaine É, et al. Accumulation of amyloid-β in the cerebellar cortex of essential tremor patients. Neurobiology of Disease.

- Farrell K, Cosentino S, Iida MA, et al. Quantitative Assessment of Pathological Tau Burden in Essential Tremor: A Postmortem Study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2019, 78, 31–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.H.; Offord, K.P.; Beard, C.M.; Kurland, L.T. Essential tremor in Rochester, Minnesota: a 45-year study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1984, 47, 466–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, E.D.; Benito-León, J.; Ottman, R.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. A population-based study of mortality in essential tremor. Neurology 2007, 69, 1982–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, N.; Hernandez, D.I.; Radler, K.; Huey, E.D.; Cosentino, S.; Louis, E. Mild cognitive impairment, dementia and risk of mortality in essential tremor: A longitudinal prospective study of elders. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 1175. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, A.; Cersonsky, T.E.K.; Kellner, S.; Huey, E.D.; Cosentino, S.; Louis, E.D. What Predicts Mortality in Essential Tremor? A Prospective, Longitudinal Study of Elders. Front Neurol, 1077. [Google Scholar]

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D. Essential tremor: emerging views of a common disorder. Nat Rev Neurol 2006, 2, 666–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D. Update on essential tremor. Minerva Med 2011, 102, 417–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morales JM, Bermejo FP, Benito-León J, et al. Methods and demographic findings of the baseline survey of the NEDICES cohort: a door-to-door survey of neurological disorders in three communities from Central Spain. Public Health.

- Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Benito-León, J. ; Vega-QS; et al La cohorte de ancianos, N.E.D.I.C.E.S. Metodología y principales hallazgos neurológicos [The NEDICES cohort of the elderly. Methodology and main neurological findings] Rev Neurol, ;46.

- Vega S, Benito-León J, Bermejo-Pareja F, et al. Several factors influenced attrition in a population-based elderly cohort: neurological disorders in Central Spain Study. J Clin Epidemiol, ;63.

- Serna A, Contador I, Bermejo-Pareja F, et al. Accuracy of a Brief Neuropsychological Battery for the Diagnosis of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: An Analysis of the NEDICES Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis 2015, 48, 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contador, I.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Fernández-Calvo, B.; et al. The 37 item Version of the Mini-Mental State Examination: Normative Data in a Population-Based Cohort of Older Spanish Adults, (.N.E.D.I.C.E.S. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2016, May;31, 263-72.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975, 12, 189–98.

- Carey, I.M.; Shah, S.M.; Harris, T.; DeWilde, S.; Cook, D.G. A new simple primary care morbidity score predicted mortality and better explains between practice variations than the Charlson index. J Clin Epidemiol, ;66.

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Cognitive decline in short and long sleepers: a prospective population-based study (NEDICES. J Psychiatr Res, 1998; ;47. [Google Scholar]

- Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D.; Villarejo-Galende, A.; Romero, J.P.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Long sleep duration in elders without dementia increases risk of dementia mortality (NEDICES. Neurology 2014. [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Morales, J.; Vega, S.; Molina, J. Prevalence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Movement Disorders 2003, 18, 389–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Louis, E.D. Incidence of essential tremor in three elderly populations of central Spain. Neurology 2005, 64, 1721–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, F.; Gabriel, R.; Vega, S.; Morales, J.M.; Rocca, W.A.; Anderson, D.W. Problems and Issues with Door-To-Door, Two-Phase Surveys: An Illustration from Central Spain. Neuroepidemiology 2001, 20, 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemi G, Savettieri G, Rocca WA, et al. Prevalence of essential tremor: A door-to-door survey in Terrasini, Sicily. Neurology 1994, 44, 61–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschl, G.; Bain, P.; Brin, M. Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Mov Disord, 2: Suppl 3.

- Louis, E.D.; McCreary, M. How Common is Essential Tremor? Update on the Worldwide Prevalence of Essential Tremor. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 2021, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed 1994, xxvii, 886–xxvii, 886.

- Bermejo-Pareja F, Benito-León J, Vega S, et al. Consistency of clinical diagnosis of dementia in NEDICES: A population-based longitudinal study in Spain. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol, ;22.

- Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Benito-León, J.; Vega, S.; Medrano, M.J.; Román, G.C. Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group. Incidence and subtypes of dementia in three elderly populations of central Spain. J Neurol Sci.

- Lenka, A.; Benito-León, J.; Louis, E.D. Is there a Premotor Phase of Essential Tremor? Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 2017, 7, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chambless, L. Test for additive interaction in proportional hazards models. Ann Epidemiol 2007, 17, 227–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia KP, Bain P, Bajaj N, et al. Consensus Statement on the classification of tremors. from the task force on tremor of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society. Mov Disord 2018, 33, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito-León, J. Essential Tremor: One of the Most Common Neurodegenerative Diseases? Neuroepidemiology 2011, 36, 77–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J. Essential Tremor: A Neurodegenerative Disease? Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements 2014, 4, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Navarro, S.G.; Mimenza-Alvarado, A.J.; Yeverino-Castro, S.G.; Caicedo-Correa, S.M.; Cano-Gutiérrez, C. Cognitive Frailty and Aging: Clinical Characteristics, Pathophysiological Mechanisms, and Potential Prevention Strategies. Arch Med Res 2024, 56, 103106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León, J.; Labiano-Fontcuberta, A. Linking Essential Tremor to the Cerebellum: Clinical Evidence. Cerebellum 2016, 15, 253–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh R, León-Ruiz M, Sardar SS, et al. Cerebellar Cognitive Affective Syndrome in a Case of Cerebrotendinous Xanthomatosis. Cerebellum 2022, 22, 776–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-León J, Louis ED, Romero JP, et al. Altered Functional Connectivity in Essential Tremor: A Resting-State fMRI Study. Medicine (Baltimore.

- Benito-León J, Sanz-Morales E, Melero H, et al. Graph theory analysis of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging in essential tremor. 2019.

- Younger EFP, Ellis EG, Parsons N, et al. Mapping Essential Tremor to a Common Brain Network Using Functional Connectivity Analysis. Neurology [Internet], /: 2024 Mar 3];101(15). Available from: https, 2024.

- Cartella SM, Bombaci A, Gallo G, et al. Essential tremor and cognitive impairment: who, how, and why. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 4133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis ED, Iglesias-Hernandez D, Hernandez NC, et al. Characterizing Lewy Pathology in 231 Essential Tremor Brains From the Essential Tremor Centralized Brain Repository. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2022, 81, 796–806. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, E.D.; Babij, R.; Ma, K.; Cortés, E.; Vonsattel, J.-P.G. Essential Tremor Followed by Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Postmortem Reports of 11 Patients. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013, 72, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritt, B.S.; Hardin, N.J.; Richmond, J.A.; Shapiro, S.L. Death Certification Errors at an Academic Institution. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2005, 129, 1476–9. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, T.G.; Monsell, S.E.; Phillips, L.E.; Kukull, W. Accuracy of the Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012, 71, 266–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenka, A.; Louis, E.D. Do We Belittle Essential Tremor by Calling It a Syndrome Rather Than a Disease? Yes. Front Neurol, 5226. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).