1. Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) poses a substantial and growing economic burden on healthcare systems worldwide. As a leading cause of hospitalization among older adults, CHF accounts for a disproportionate share of healthcare expenditures relative to its prevalence. The economic impact is multifactorial, encompassing direct costs such as inpatient care, outpatient visits, medications, and device therapies, as well as indirect costs related to lost productivity, disability, and informal caregiving. Hospitalizations, in particular, represent the largest single contributor to direct costs, often driven by frequent readmissions and the need for intensive management of decompensated episodes. In the United States alone, the total annual cost of heart failure was estimated to exceed

$35 billion, with projections suggesting a doubling of costs by 2030 due to aging populations and increasing prevalence [

1]. European health systems report similar financial pressures [

2,

3]. Importantly, the burden of CHF is not limited to healthcare systems but extends to patients and families through out-of-pocket expenses [

4,

5] and diminished quality of life. Efforts to mitigate these costs have increasingly focused on early identification, optimization of guideline-directed medical therapy, and prevention of hospital admissions. Understanding the drivers of cost in CHF, particularly those modifiable through clinical care or self-management, remains critical for developing sustainable healthcare models in an era of rising chronic disease burden.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as health-related quality of life have also emerged as predictors of healthcare utilization and cost, highlighting the importance of integrating patient perspectives into cost-containment strategies. PROs have also become increasingly recognized as essential tools in the management of CHF [

6,

7,

8,

9], providing direct insight into patients’ symptoms, functional status, and quality of life. Instruments such as the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) allow clinicians and researchers to capture the lived experience of heart failure [

10,

11], which often cannot be fully assessed through objective measures alone. PROs complement clinical data by revealing limitations in daily activities, psychosocial impacts, and treatment tolerability - all of which are relevant to care planning and prognosis. Beyond their clinical utility, PROs have demonstrated growing value in the economic evaluation of CHF management. Lower PRO scores are consistently associated with increased hospitalization rates, higher healthcare utilization, and poorer outcomes, making them useful predictors of future cost. Several studies have shown that PROs can identify high-risk patients who are likely to incur substantial healthcare costs [

12], thereby supporting more targeted interventions, early follow-up, and resource allocation. Moreover, improvements in PROs are increasingly being used as endpoints in cost-effectiveness analyses of therapies [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], particularly as healthcare systems shift toward value-based care models. Integrating PROs into routine care may also facilitate shared decision-making, enhance adherence, and improve patient satisfaction - factors that can contribute indirectly to cost reduction. As health systems seek sustainable strategies to manage CHF, PROs offer a unique bridge between clinical effectiveness and economic value, helping to align care with what matters most to patients while optimizing healthcare resources. While the use of PROs to study the economic burden of CHF are abundant from developed countries, such reports from emerging and developing countries are scarce.

In this context, the current study aims to evaluate the significance and independence of PROs in predicting costs of hospitalized CHF cases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This observational cross-sectional study included all adult patients with a physician-confirmed diagnosis of CHF who were randomly admitted to the internal medicine department of a university emergency hospital from Bucharest, Romania, between July and September 2024. Patients with incomplete questionnaire responses, missing CHF characteristics or cost data, and those who died during the admission were excluded. All patients offered written informed consent and the study was approved by the local ethics committee.

2.2. Data Collection and Measures

Patient demographics (age; sex; dwelling; smoking status), CHF clinical characteristics (ultrasound-estimated left ventricular ejection fraction – LVEF; New York Heart Association - NYHA functional class), comorbidities (defined with the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases codes and used to calculate the Charleston comorbidity index – CCI [

20]), laboratory values (N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide - NT-proBNP, normal < 125 pg/mL; serum creatinine, normal < 1.2 mg/dL) and economical characteristics of the hospitalization (total cost, hospitalization duration) were collected from electronic medical records.

Upon admission, each patient filled in the validated Romanian version of the 12-item KCCQ, used with the author’s permission), which is a validated heart failure-specific patient-reported outcome measure [

10,

11], with items that evaluate how CHF affects patients’ lives in terms of physical limitation, symptom stability, symptom frequency, symptom burden, total symptom score, self-efficacy, quality of life, social limitation, overall summary score and clinical summary score. All KCCQ scores range from 0 to 100 and are summarized in quartiles which represent health status as follows: very poor to poor (0-24); poor to fair (25-49); fair to good (50-74); and good to excellent (75-100).

Also, each patient underwent clinical interview, clinical examination and transthoracic echocardiography as part of routine clinical evaluation in the same admission. LVEF was assessed by clinic’s experienced sonographers in accordance with the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography (LVEF was estimated using the biplane Simpson’s method of discs from apical two- and four-chamber views when image quality permitted; in cases of suboptimal image quality, visual estimation by an experienced cardiologist was accepted) [

21]. LVEF was used to classify CHF as follows: CHF with reduced LVEF (HFrEF; LVEF ≤ 40%), CHF with mildly reduced LVEF (HFmrEF; LVEF = 41-49%) and CHF with preserved LVEF (HFpEF; LVEF ≥ 50% with ultrasound-defined left ventricular hypertrophy, left atrium dilatation or diastolic dysfunction) [

22].

Serum creatinine was used to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) with the 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in order to classify CKD according to eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) in stages G1 (≥ 90), G2 (60-89), G3a (45-59), G3b (30-44), G4 (15-29) and G5 (< 15) [

23].

Regarding cost, Romanian hospitals issue a hospital bill upon discharge, which represents the cost variable recorded by the study. The amount of the expense bill for each discharged patient includes three components: a) the daily hospital charge per ward/compartment, which is established annually by the hospital and which excludes the value of medicines, medical supplies or services/interventions; b) the number of days of hospitalization completed per discharged case; and c) the value of medicines, including those from national programs, medical supplies, laboratory tests; medical investigations and interventions/manoeuvres; food allowance. For this study, hospitalization cost is reported at an average exchange rate of 5 Romanian Leu per 1 Euro (€).

All measures (clinical interview, clinical examination, blood sampling, echocardiography, questionnaire filling) were done within the maximum first 2 days of the same admission for each patient.

2.3. Statistics

Data distribution normality was assessed using descriptive statistics, normality, stem-and-leaf plots and the Lillefors corrected Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Continuous variables are reported as “mean ± standard deviation” (SD) if normally distributed, or as “median (interquartile range)” (IQR) if non-normally distributed, while nominal variables are reported as “absolute frequency (percentage of group or subgroup)”.

Group comparisons of hospitalization cost and duration across KCCQ Overall Summary Score (KCCQ-OSS) categories (<25, 25-49, 50-74, ≥75) were performed using Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Total hospitalization cost and hospitalization duration were used as the primary outcomes, while the KCCQ Overall Summary Score (KCCQ-OSS), a measure ranging from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicating better health status), was used as the primary predictor variable. The association between baseline KCCQ-OSS and the primary outcomes was first assessed using Spearman’s rank correlations. Since the primary outcome measure variables failed normality and homoscedasticity of residuals tests due to their skewness, generalized linear modeling (GLM) with a gamma distribution and log link function was employed to evaluate the independent predictive value of KCCQ-OSS. All potential confounders (age, sex, CCI, CKD class, LVEF class, and NYHA class) were entered simultaneously using the enter method. Interaction terms were tested to explore potential effect modification by age and sex. Multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIF), and a threshold of VIF > 5 was considered indicative of significant collinearity. Exponentiated beta coefficients were reported to interpret the effect of predictors as relative changes in expected cost and hospitalization duration. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by stratifying the sample by ejection fraction category (HFrEF vs. HFpEF) and by age tertiles. Given the limited subgroup sizes, these analyses were performed primarily to explore consistency in the direction and magnitude of the association between KCCQ-OSS and hospitalization cost.

All tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., released 2019, Armonk, NY), and a p value below 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

The study included 171 CHF patients with an average age of 73.5 years and a predominance of women (55.0%;

Table 1). The sample showed a uniform distribution of NYHA 2-4 classes: 33.3% had NYHA class 2, 33.9% had NYHA class 3 and 32.7% had NYHA class 4. Regarding type of LVEF, 56.7% were diagnosed with HFpEF, 15.2% with HFmrEF and 28.1% HFrEF.

Regarding economic variables, the sample produced a median total hospitalization cost of 1513 €/patient, with a median daily cost of 260 €/day/patient for a mean hospitalization duration of 8.7 days (

Table 1).

In terms of patient-reported outcomes (

Table 2), 32.7% of patients reported significant physical limitation (very poor KCCQ score), 26.3% of patients reported low symptom stability, 31.6% of patients reported high symptom frequency, 28.1% of patients reported high symptom burden, 26.3% of patients reported low quality of life and 46.2% of patients reported significant social limitation. Despite these reports, 58.5% of patients reported good self-efficacy.

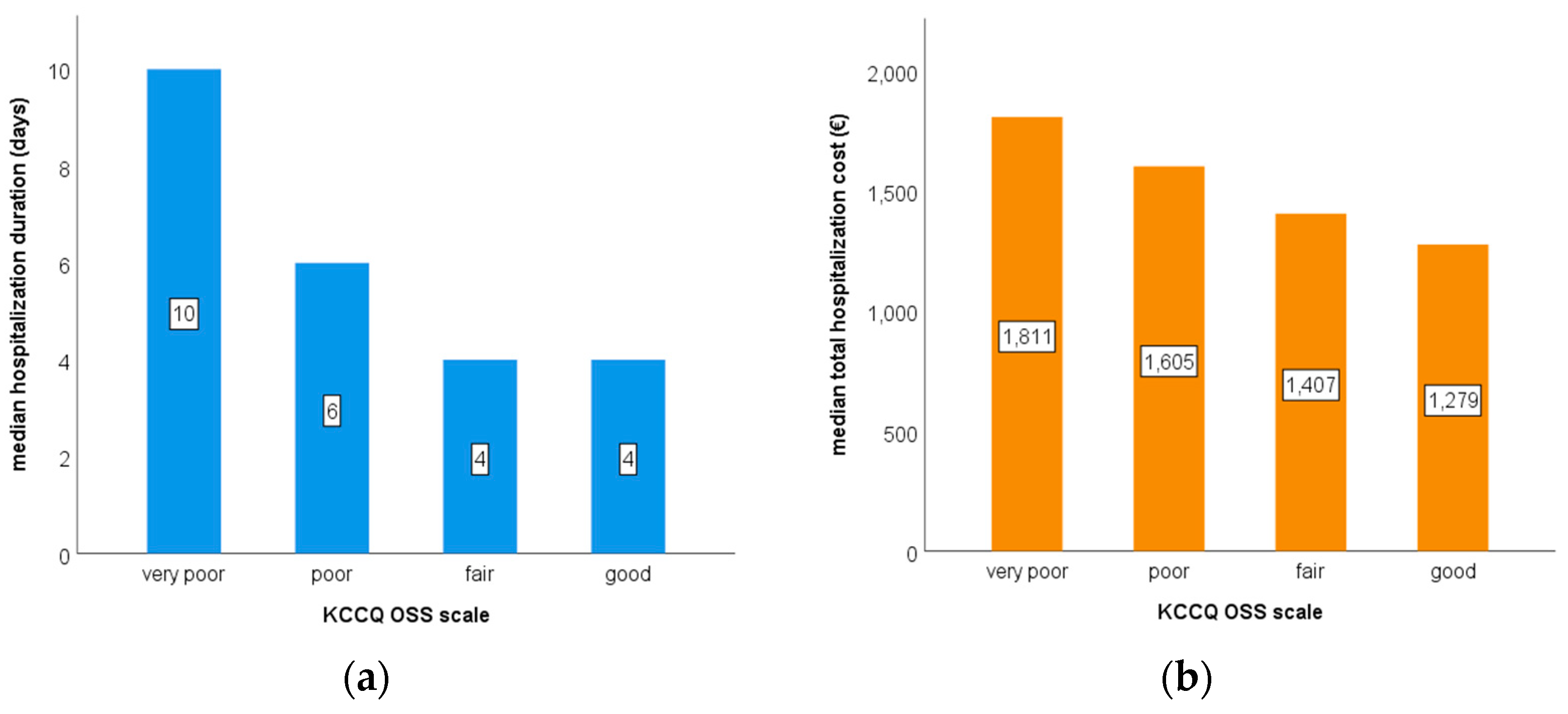

Generally, median hospitalization duration and median total hospitalization cost increased with each KCCQ-OSS class (

Figure 1): compared to patients with good KCCQ-OSS scores (n = 17), patients with very poor KCCQ-OSS scores (n = 66) had significantly higher median hospitalization duration (10 day versus 4 days; p < 0.001) and significantly higher median total hospitalization costs per patient (1811 € versus 1279 €; p = 0.029).

The GLM model which examined the association between baseline KCCQ-OSS and hospitalization duration demonstrated acceptable goodness of fit (deviance/degrees of freedom - df = 0.44; Pearson χ²/df = 0.51) and revealed that baseline KCCQ-OSS was significantly and independently associated with hospitalization duration (

Table 3 – model 1). Specifically, each 10-point decrease in KCCQ-OSS was associated with a 9.5% increase in expected hospitalization duration (exp(B) = 0.990; 95% confidence interval - CI: 0.985-0.994; p < 0.001). Other significant predictors included HFrEF, NYHA class and NT-proBNP level. Similarly, the GLM model which examined the association between baseline KCCQ-OSS and total hospitalization cost demonstrated acceptable goodness of fit (deviance/df = 0.37; Pearson χ²/df = 0.68) and revealed that baseline KCCQ-OSS was significantly and independently associated with total hospitalization cost (

Table 3 – model 2). Specifically, each 10-point increase in KCCQ-OSS was associated with a 5.1% increase in expected cost (exp(B) = 1.005; 95% CI: 1.000-1.010; p = 0.031). Other significant predictors included HFrEF, NYHA class and CCI score. Within each model and each subgroup, stratified analyses by ejection fraction category and age tertiles showed that the association between KCCQ-OSS and cost remained directionally consistent with the primary model. However, confidence intervals were wider and some estimates were not statistically significant, likely reflecting limited power due to small subgroup sizes.

4. Discussion

This study found that baseline patient-reported health status, as measured by the KCCQ, was a significant and independent predictor of total hospitalization cost and of hospitalization duration in patients with CHF: lower KCCQ-OSS scores were associated with higher expected hospitalization costs and duration, even after adjusting for potential confounders. These findings suggest that patients’ subjective assessment of their symptoms and functional limitations carries valuable prognostic information beyond traditional clinical metrics. The association between poorer health-related quality of life and increased hospitalization cost and duration highlights the potential utility of integrating PROs into cost prediction and risk stratification models in CHF care. Incorporating PROs such as the KCCQ into routine CHF management could help identify high-cost, high-risk patients earlier, allowing for proactive intervention. In a value-based care context, PROs could offer a cost-effective, patient-centered means of stratifying risk and tailoring resource allocation.

In this study, a substantial proportion of patients - ranging from one-fifth to one-third (

Table 2) - reported very poor scores (typically defined as < 25) across multiple KCCQ domains, including physical limitation, symptom stability, symptom frequency, symptom burden, quality of life, and social limitation. This finding highlights the considerable symptom burden and functional impairment experienced by a large segment of the CHF population. These low scores reflect the profound impact of CHF on daily life and underscore the importance of addressing not just clinical measures (e.g., NYHA class, ejection fraction, NT-proBNP), but also the patient’s subjective experience. Interestingly, the self-efficacy domain showed a markedly different pattern, with only 2.9% of patients reporting very poor scores. This suggests that, despite severe symptoms and limitations, most patients feel confident in their ability to manage their condition. However, the apparent disconnect between high self-efficacy and poor health status raises important clinical questions: are patients overly optimistic about their disease management, or are they truly empowered but overwhelmed by disease severity? This discordance may signal an opportunity for clinicians to target specific interventions, such as psychosocial support, palliative care discussions, or enhanced education focused not only on self-management but also on improving actual health status and symptom control.

Our findings that lower KCCQ-OSS scores are associated with increased hospitalization costs and longer lengths of hospitalization align with existing literature emphasizing the prognostic value of PROs in CHF management [

24]. In a seminal study by Heidenreich et al., patients with the poorest health status (KCCQ score <25) incurred approximately

$9,000 more in 12-month healthcare costs compared to those with better scores, underscoring the economic implications of diminished patient-reported health status [

25]. Further supporting this, Dai et al. demonstrated that lower KCCQ scores obtained prior to hospital discharge were significantly associated with higher 30-day readmission rates in CHF patients. The study highlighted that each 25-point decrease in KCCQ score corresponded to a substantial increase in readmission risk, suggesting that KCCQ can serve as a valuable tool for identifying patients at elevated risk for rehospitalization [

26]. Additionally, research by Sauser et al. indicated that KCCQ scores are sensitive to clinical changes during hospitalization and can reflect improvements or deteriorations in patient status, which may correlate with hospitalization duration [

27]. Collectively, these studies reinforce the utility of KCCQ-OSS as a predictive measure for both clinical outcomes and healthcare resource utilization in CHF, aligning with our findings that lower KCCQ scores are indicative of higher hospitalization costs and extended lengths of hospital stay. Already, using tools like KCCQ, studies are investigating alternative care models, such as early discharge to clinic-based therapy of patients presenting with decompensated CHF [

28] and early palliative care [

29].

Strengths of this study include the use of a validated PRO instrument, a real-world patient cohort, and cost data from actual hospitalization records. However, limitations include a modest sample size, which may have limited the power of subgroup analyses. Additionally, while cost was modeled using GLM to address skewness, unmeasured confounding and variation in institutional billing practices may influence estimates. Also, lack of data on other potential confounders, such as medication use, hospitalization history and alcohol use may impact the results.

Future studies with larger, multi-center cohorts are needed to validate these findings and to explore whether interventions that improve KCCQ scores can also reduce downstream costs. Integration of PROs into electronic health records and cost prediction algorithms should be a focus of ongoing health system innovation.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that KCCQ-OSS is a significant independent predictor of both hospitalization cost and duration in CHF. Additionally, a substantial proportion of patients reported very poor scores across multiple KCCQ domains, reflecting a high symptom burden and diminished quality of life. These findings underscore the clinical and economic utility of integrating PROs into routine CHF care. Incorporating KCCQ assessment may support early identification of high-risk, high-cost patients, guide resource allocation, and ultimately enhance patient-centered and value-based management strategies in CHF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and D.-I.M.; methodology, A.-L.C., D.G.M.; software, C.-C.P., D.-I.M.; validation, A.M., C.-C.P. and A.R.; formal analysis, C.-C.P., D-.I.M.; investigation, A.-L. C., A.C., A.R.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., C.-C. P.; writing—review and editing, A.C., D.-I.M., A.-L.C., V.G., D.G.M., A.R.; visualization, V.G.; supervision, D.-G. M., V.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of “Prof. Dr. Agrippa Ionescu” Clinical Hospital (protocol code 292318/April 18th 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila through the institutional program “Publish not Perish”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCI |

Charleston comorbidity index |

| CHF |

Chronic heart failure |

| CKD-EPI |

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration |

| eGFR |

estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| GLM |

generalized linear modeling |

| HFmrEF |

CHF with mildly reduced LVEF |

| HFpEF |

CHF with preserved LVEF |

| HFrEF |

CHF with reduced LVEF |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| KCCQ |

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| KCCQ-OSS |

KCCQ Overall Summary Score |

| LVEF |

left ventricular ejection fraction |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association |

| PROs |

Patient-reported outcomes |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| VIF |

variance inflation factors |

References

- Wei C, Heidenreich PA, Sandhu AT. The economics of heart failure care. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;82:90-101. [CrossRef]

- Hessel, FP. Overview of the socio-economic consequences of heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021;11(1):254-62. [CrossRef]

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Walli-Attaei M, Gray A, Torbica A, Maggioni AP, Huculeci R, et al. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the European Union: a population-based cost study. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(45):4752-67. [CrossRef]

- Gunn AH, Warraich HJ, Mentz RJ. Costs of care and financial hardship among patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2024;269:94-107. [CrossRef]

- Rao BR, Allen LA, Sandhu AT, Dickert NW. Challenges Related to Out-of-Pocket Costs in Heart Failure Management. Circ Heart Fail. 2025;18(3):e011584. [CrossRef]

- Butler J, Usman MS, Gandotra C, Salman A, Farb A, Thompson AM, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes as End Points in Heart Failure Trials. Circulation. 2025;151(15):1111-25. [CrossRef]

- Fonarow GC, Tang AB. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Heart Failure: Delivering More Dimensions. JACC Heart Fail. 2025;13(2):293-5. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Lan RH, Sandhu AT. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Heart Failure Clinical Trials: Trends, Utilization, and Implications. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2025;18(2):e011423. [CrossRef]

- Rorah D, Pollard J, Walters C, Roberts W, Hartwell M, Hemmerich C, Vassar M. Assessing the completeness of patient-reported outcomes reporting in congestive heart failure clinical trials. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;18:17539447241303724. [CrossRef]

- Spertus JA, Jones PG. Development and Validation of a Short Version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(5):469-76. [CrossRef]

- Spertus JA, Jones PG, Sandhu AT, Arnold SV. Interpreting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Clinical Trials and Clinical Care: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(20):2379-90. [CrossRef]

- Hung M, Zhang W, Chen W, Bounsanga J, Cheng C, Franklin JD, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Total Health Care Expenditure in Prediction of Patient Satisfaction: Results From a National Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2015;1(2):e13. [CrossRef]

- Booth D, Davis JA, McEwan P, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, De Boer RA, et al. The cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin in heart failure with preserved or mildly reduced ejection fraction: A European health-economic analysis of the DELIVER trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(8):1386-95. [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen J, Mustonen P, Heikkila E, Leskela RL, Pennanen P, Kruhn K, et al. Effectiveness of Telemonitoring in Reducing Hospitalization and Associated Costs for Patients With Heart Failure in Finland: Nonrandomized Pre-Post Telemonitoring Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2024;12:e51841. [CrossRef]

- McEwan P, Darlington O, McMurray JJV, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Bohm M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin as a treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a multinational health-economic analysis of DAPA-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(11):2147-56. [CrossRef]

- Parizo JT, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Salomon JA, Khush KK, Spertus JA, Heidenreich PA, Sandhu AT. Cost-effectiveness of Dapagliflozin for Treatment of Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(8):926-35. [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann CJ, Marino P, Mahlknecht A, Barbieri V, Piccoliori G, Engl A, Gidding-Slok AHM. A cluster-randomized study to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Assessment of Burden of Chronic Conditions (ABCC) tool in South Tyrolean primary care for patients with COPD, asthma, type 2 diabetes, and heart failure: the ABCC South Tyrol study. Trials. 2024;25(1):202. [CrossRef]

- Yu DS, Li PW, Li SX, Smith RD, Yue SC, Yan BPY. Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of an Empowerment-Based Self-care Education Program on Health Outcomes Among Patients With Heart Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e225982. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, Parizo JT, Spertus JA, Heidenreich PA, Sandhu AT. Cost-effectiveness of Empagliflozin in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(12):1278-88. [CrossRef]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83. [CrossRef]

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):1-39 e14. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJ, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid M, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-12. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen C, Bamber L, Willey VJ, Evers T, Power TP, Stephenson JJ. Patient Perspectives on the Burden of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in a US Commercially Insured and Medicare Advantage Population: A Survey Study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2023;17:1181-96. [CrossRef]

- Chan PS, Soto G, Jones PG, Nallamothu BK, Zhang Z, Weintraub WS, Spertus JA. Patient health status and costs in heart failure: insights from the eplerenone post-acute myocardial infarction heart failure efficacy and survival study (EPHESUS). Circulation. 2009;119(3):398-407. [CrossRef]

- Dai S, Manoucheri M, Gui J, Zhu X, Malhotra D, Li S, et al. Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire Utility in Prediction of 30-Day Readmission Rate in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:4571201. [CrossRef]

- Sauser K, Spertus JA, Pierchala L, Davis E, Pang PS. Quality of life assessment for acute heart failure patients from emergency department presentation through 30 days after discharge: A pilot study with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. J Card Fail. 2014;20(5):378 e11-5.

- Ranasinghe MP, Koh Y, Vogrin S, Nelson CL, Cohen ND, Voskoboinik A, et al. Early Discharge to Clinic-Based Therapy of Patients Presenting With Decompensated Heart Failure (EDICT-HF): Study Protocol for a Multi-Centre Randomised Controlled Trial. Heart Lung Circ. 2024;33(1):78-85. [CrossRef]

- Becher MU, Balata M, Hesse M, Draht F, Zachoval C, Weltermann B, et al. Rationale and design of the EPCHF trial: the early palliative care in heart failure trial (EPCHF). Clin Res Cardiol. 2022;111(4):359-67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).