What Is Known

Chronic disease self-management (CDSM) programs have proven benefits in the management of many chronic diseases

CDSM programs benefits in improving MACE in CHF remains unclear

CDSM can be delivered as generic or disease specific programs, the former has been tested widely in CHF.

What Is New

Generic CDSM programs can be used in CHF

Generic short form tools derived from gold standard CDSM can risk stratify poor and good self-managers

Self-managers with borderline and average abilities require greater understanding when designing randomized trials to further analyse these findings.

1. Introduction

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a chronic disease. Chronic disease self-management (CDSM) is important for CHF patients for the following two reasons. Firstly, in Australia, at least 50% of population suffer one of these eight chronic conditions namely, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, arthritis and back pains, mental health conditions, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and cancer [

1]. CHF in many cases is associated with at least one of the chronic conditions above [

2]. Secondly, the prevalence, morbidity, mortality, readmission and resource cost of CHF are on the rise. CHF is resource intensive, it’s disease loads and hospital readmissions continue to rise [

3,

4]. While empowering patients through chronic disease self-management has sound theoretical basis, the CHF guidelines are complex, there are unanswered questions and evidence gaps [

5].

An important theoretical framework Wagners ‘Chronic Care Model’ [

6] published several decades ago, identified two key domains and six key elements: the health system domain requires organised health services, delivery system redesign, clinical information systems and decision support; and a community domain requiring community linkages resources and policies to enhance self-management support. Cameron et.al [

7] in 2009 established from 14 CHF specific instruments, that were promoted in best practice, for the provision of disease-specific measures of CHF self-care behaviours; psychometric analysis revealed that only 2 tools were reliable and valid to specifically measure CHF self-management. In the ensuing decades publications have covered a range of topics from theory, practical management, and consensus guidelines, with optimism [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Nonetheless, trial results were not forthcoming, and the American Heart Foundation demoted self-management in CHF from a performance to quality measure [

10], which has filtered into the guidelines [

3,

4,

5]. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to create a focus on generic CDSM programs and build the evidence from this platform. The program in review is the Flinders Program of Chronic condition Self-management (CFPI), a gold standard tool for CDSM. The CFPI has been validated, published data support good validity and internal consistency, and it is also utilised clinically across a range of conditions [

1,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] however not CHF. The basis of its theoretical foundation was published in 2003, where the Partners in Health Scale (PIH), a patient reported outcome tool, using 12 questions and over 4 domains, assess patients’ skills (knowledge, partnership, recognising and managing, coping) on symptoms and condition. This paper uses Battersby’s et.al definition of self-management as ‘

the active involvement of the patient in the management of their chronic medical condition’ [

14].

In this study, we aim to assess the psychometric properties (internal reliability and construct validity) of the Partners in Health (PIH) scale, a chronic condition self-management instrument to assess baseline self-management behaviours in a CHF cohort. For this syndrome, the literature supports the observation that validated CHF specific CDSM programs are few and, comorbid conditions are frequent in CHF [

5,

24]; thus, assessing both disease specific and generic CDSM tools could be important, and for the generic Flinders Program of CDSM, validating the PIH scale is an important first step in utilizing this tool.

2. Methods

The study data is from a subanalysis of the

SELFMANagement in Heart Failure Study (

SELFMAN-HF) study, as described in the protocol [

24].

2.1. Design

A clinical audit was performed on 210 consecutive patients screened for the SELFMAN-HF study, assessing the efficacy of CDSM programs, in patients commencing Sodium Glucose Co-transport 2 inhibitor (SGLT-2i) for CHF. As a routine for chronic disease management, all patients completed the PIH tool at baseline. The cohort included patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The study team, and expert panel designed, oversaw the conduct and analysis of results. The analyses were conducted by 3 investigators (PI, FH, DS).

2.3. Participants

For this audit eligible patients were aged over 18 years who, were screened for use of SGLT-2i within May 2022 and Jan 2024, with a clinical diagnosis of CHF, were eligible for an SGLT-2i and had completed a PIH as routine clinical work-up and care. Patients screened were predominantly HFrEF cohort, aged over 18 years started SGLT-2i within 6 months - for systolic CHF, echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40%. Patients screened with LVEF > 40%, who completed with PIH scale at baseline were not enrolled into the prospective

SELFMAN-HF study, however baseline data were used to form this psychometric audit analysis. Patients were excluded, should concerns be raised by any medical staff; has a life expectancy of ≤6 months whilst receiving palliative or nursing home care; have a significant cognitive impairment; or started SGLT2-i for more the >6 months [

24].

2.4. Sample Size Calculations

The effect size for the introduction of SGLT-2i in a community cardiology population with treated CHF is not known. The study design chose >80 patients with LVEF <40% and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class 2 or 3. The documented event rates in similar settings for readmission and mortality at 1 month and 1 year were 25%. Thus, a follow up at 12 months would see >100 admissions and >10 mortalities. Interim analysis at 3-6 months, and the lower event rates the sample size was increased to the documented number.

2.5. Trial Instruments and Procedures

2.5.1. CFPI Program and PIH Tools

The CFPI is a generic and comprehensive CDSM program that utilises various tools (questionnaires) to obtain a patient centred, comprehensive and flexible program of care for patients. This tool is gold-standard and is on par with other programs in achieving its outcomes, i.e., assess self-management understanding and goals, and from this understanding can tailor education to achieve self-efficacy for managing chronic disease. The CFPI program extract patient reported outcomes (PRO) and health services data along 4 part [

13] 1) The Partners in Health Scale (PIH) is a self-rated questionnaire for the patient to assess their self-management knowledge, attitudes, behaviours and impacts of their chronic condition. 2) The PIH, using 12 questions and 8-point Likert scale, to score patient on 4 self-management domains, knowledge, partnership in treatment, recognition and management of symptoms and coping; 3) the additional parts are the cue and response, problems and goals and chronic condition care plan, 4) CFPI are detailed in these references [

1,

13,

14,

15,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

2.5.2. Data Collection

The PIH scale was completed by all patients screened at the heart failure clinic. Forms with done in the waiting room, the doctors’, or heart failure nurse office. Patients were offered guidance if they had difficulty interpreting the study and asked for assistance. The PIH use Likert-type scales (an 8-point rating scale), which allow change and progress to be measured and recorded during reviews. The PIH is provided to the patient in the waiting room or the consulting room. Time is provided to fill in the scale. Patients are provided assistance if they are not able to understand or if they have carer or partner to help.

2.5.3. Ethical Considerations

This study has been approved by the St Vincent’s ethics committee (approval no. LRR 177/21). All participants will complete a written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study.

2.5.4. Statistical Aspects and Data Analysis

We investigated the convergent and discriminant validity of PIH using Bayesian Confirmatory Factor Analysis (BCFA). This approach is a compromise between maximum likelihood (ML) CFA and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). In a single step analysis, BCFA enables the specification of the prior hypothesized major factor patterns as well as informative small-variance priors for cross-loadings and residual covariances. The cross-loadings model the relationships between PIH indicators and nontarget factors, and residual covariances model shared sources of influence on the PIH indicators that are unrelated to the factors. A strategic use of such priors facilitates a more substantive interpretation of model parameters in context of the current study population. This approach also minimizes the capitalization on chance that otherwise may occur through a sequence of model modifications. Statistical inferences about parameter estimates and model fit are made from a posterior distribution. A BCFA is like a standard CFA but does not rely on large-sample theory and performs better with small samples compared to ML algorithms. In other words, the Bayesian framework does not require traditional model identification to estimate model parameters. Previous studies have shown that using prior information (e.g., small variance priors for cross loadings and residual covariances) in a Bayesian estimation framework provide reliable estimates for small study samples (e.g., N=20; N =40).

Bayesian confirmatory factor analysis was first used to estimate the PIH-CFA model with zero cross-loadings. We then repeated the BCFA analysis, firstly with the addition of small, informative priors for cross-loadings and then with additional non-zero priors for the residual correlations. The observed variables were standardized in accordance with the standardized priors. To identify a suitable cross-loading prior variance a range of increasing values (0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.30) were initially tested. The aim was to find a value that made a substantial reduction in the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the observed and the replicated chi-square values relative to the original CFA model without cross-loadings whilst not sacrificing speed of convergence [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

The Inverse-Wishart (

IW) distribution was then used for the addition of residual correlations to the model. This is the conventional prior distribution for covariance matrices in Bayesian analysis [

32]. Priors were set for

IW(

dD,

d) where

d is the degrees of freedom of the distribution and

D is a diagonal matrix comprised of residual variances from the BCFA model [

32,

33]. The starting value for the degrees of freedom parameter was set at

d =50 and then varied to find the largest value that generated a posterior predictive

p-value (PP

p) greater than 0.05 to show acceptable BCFA model fit and at the same time being close to the CFA model. This was to enable the identification of the smallest possible modifications to address CFA model misfit [

32]. BSEM does not require the assumptions of normality and is independent of large sample theory [

33].

Bayesian estimation was comprised of 8 independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and two processors. The minimum number of iterations was set at 15,000 and maximum of 100,000 and monitored using the potential scale reduction (PSR) criterion where values less than 1.1 provide evidence for convergence [

34]. To evaluate BCFA models, Bayesian versions of approximate fit indices root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), confirmatory fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were used. The suggested cut off values for reasonably well-fitting models are: RMSEA<0:06, TLI > 0:95, CFI > 0:95. The Discrepancy Information Criterion (DIC) was also used to compare models as it takes into account model complexity via the estimated number of parameters or effective number of parameters [

32,

35]. Lower values are indicative of a better fitting model. To assess the internal reliability of PIH raw scores, McDonald’s omega coefficients and 95 % Bayesian credible intervals were calculated using estimates from the final model [

36]. For health status questionnaires, coefficient values between 0.70 and 0.95 are indicative of good internal consistency [

37]. All analyses were conducted using MPlus software (Version 8.9).

3. Results

Patient Demographic and Characteristics

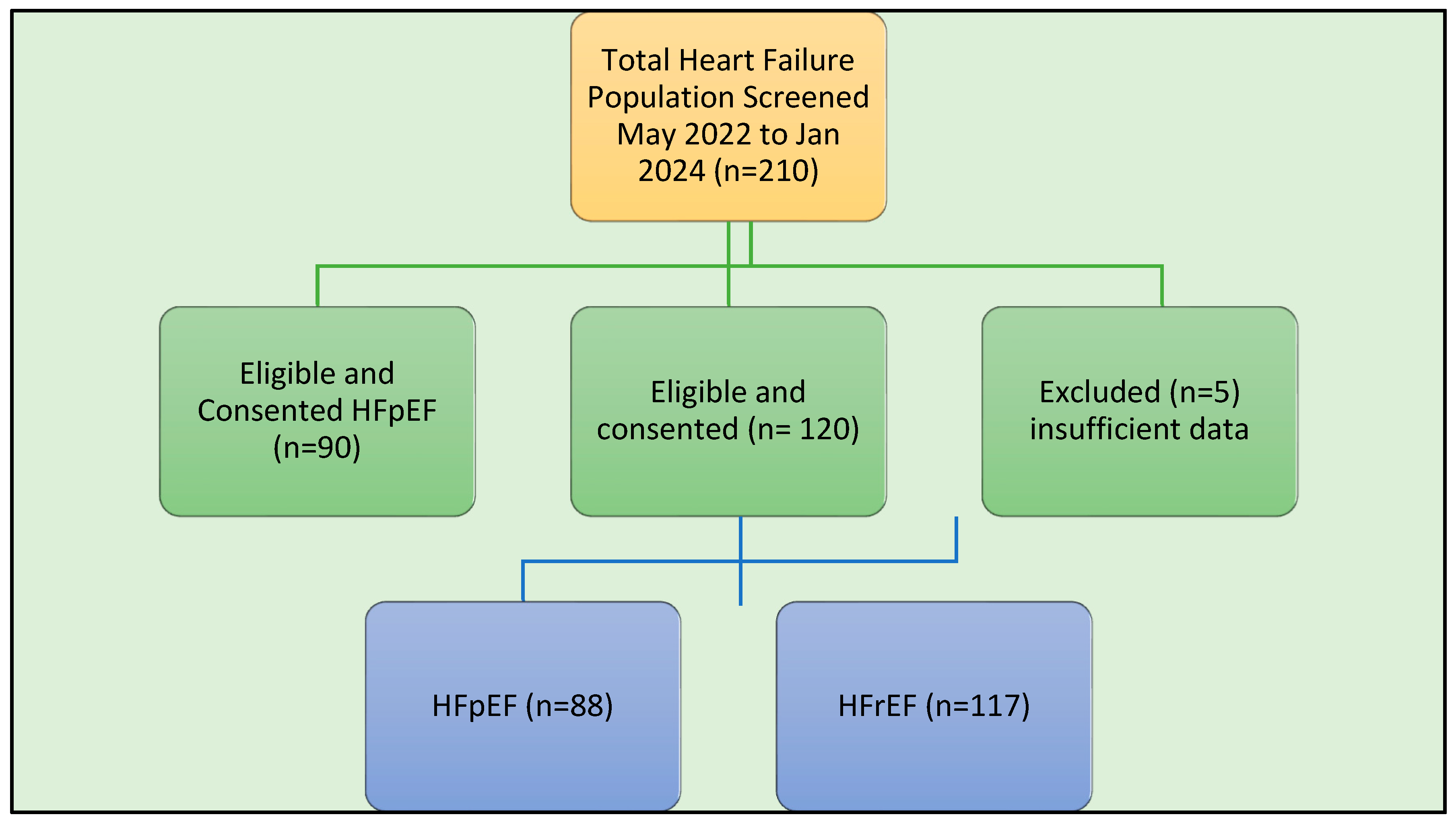

From May 2022 till January 2024, 210 CHF patients (117 HFrEF and 88 HFpEF) were audited from a cohort eligible for SGLT-2i who had completed the PIH and had (

Figure 1) available baseline information.

Baseline Characteristics (HFrEF)

The HFrEF study population comprising 117 patients, the baseline study characteristics are summarised in

Table 1. The mean age was 66.8 years old (SD 13.5) and the gender, 88 (75 %) were male and 29 females. The majority of patients ethnicity were Caucasian

90 (77%)], the others South Asian, Asian, African or Indigenous. Most patients were married, 75 (64%)]. At least 71 (65%) described spouse of family supports for their ailment. A majority in 90 (76.9%) of patients had education up to high school level. Renal impairment defined as eGFR <60 ml/min were recorded in 48 (39%) patients. Thirty (25,6%) of patients did not record any associated comorbidity at baseline, 26 (22.3%) had one and the remainder had 3 or more. Hypertension and hypercholesterolemia were the most common comorbidity in 79 (68%) and 73 (62.4%) patients 79 and 73% respectively. Coronary artery disease (CAD) and diabetes was recorded in 51 (44%) and 42 (36%), obstructive sleep apnoea was also common, recorded in 31 (26.5%) of the cohort. Smoking history was recorded in 53 (45%) CHF was not a new diagnosis, i.e. a chronic condition, having been diagnosed prior to 12 months in 34 (29%) of the cohort. At baseline all patients had commenced Sodium Glucose co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors (SGLT2-i), within 6 months of identification for study enrolment. At this point at least 3 of 4 CHF [beta-blocker, renin-angiotensin aldosterone and/or neprilysin inhibitor (RAAS/ ARNI) or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA)] pillars were already started in patients diagnosed prior to 12 months. Most patients with diagnosis of CHF within the 12 months period were also optimised on CHF pillar therapy. As was the requirement for eligibility of SGLT-2i, all patients were NYHA class 2 or more, with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) Class III (<40%) and greater. CHF therapy was good all patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant at baseline. CHF pillars were 112 (96%) for BB, 111 (95.1%) for RAAS/ARNI, and 46 (39%) for MRA. Polypharmacy was common

101 (68%) had at least 5 prescribed medications classes. Cardiac rehabilitation was only recorded among 16 (14%) of patients.

Baseline Characteristics (HFpEF)

The study population HFpEF comprising 88 patients, baseline study characteristics are summarised in table 1. The population had was 71.3 years old (SD 9.76); 46 (52%) were male and 42 (48%) females, highly very distinct demographics to HFrEF. The majority of patients ethnicity were Caucasian [90 (77%)], the others South Asian, Asian, African or Indigenous. Most patients were married [75 (85%)]. At least 71 (82%) described spouse of family supports for their ailment. A majority in 63 (71%) of patients had education up to high school level. Renal impairment defined as eGFR <60 ml/min were recorded in 23 (26%) patients. Only 3 (3.5%) of patients did not record any associated comorbidity at baseline, 32 (36.3%) had one and the remainder had 3 or more. Hypertension and hypercholesterolemia were the most common comorbidity in 76 (87%) and 67 (76%) patients respectively. Coronary artery disease (CAD) and diabetes was recorded in 30 (41%) and 29 (33%), obstructive sleep apnoea was also common, recorded in 21 (24%) of the cohort. Smoking history was recorded in 29 (33%) Heart failure was not a new diagnosis, i.e. a chronic condition, having been diagnosed prior to 12 months in only 7 (8%) of the cohort. At baseline 71 (80.7%) patients had commenced Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter-2 Inhibitors (SGLT2-i), within 6 months of identification for study enrolment. At this point with HFpEF the heart failure pillar was not relevant and only 2 (2.3%) were on ARNI, 46 (52.3%0 on BB, and 15 (17%) on MRA starkly different to HFrEF cohort. Most patients with diagnosis of CHF within the 12 months period were also optimised on CHF pillar therapy (BB, RAAS/ ARNI or MRA). As was the requirement for eligibility of SGLT-2i, all patients were NYHA class 2 or more, however all patients had left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) Class 1 (>50%) a clear separation with HFrEF patients. CHF therapy was not as good where diuretic, MRA and calcium channel blocker (CCB) use were lower. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant at baseline varied on comorbidity. CCF pillars for HFpEF is only the SGLT2i and were 71 (80.7) reflecting difficulty in diagnosis, ongoing understanding of HFpEF treatments and overlap with other indications such as DM and proteinuric chronic renal impairment. Polypharmacy was common 27 (31%) had at least 5 prescribed medications classes, although lower than HFrEF. Cardiac rehabilitation was not recorded in any participant for HF.

BCFA Model

The BCFA with exact zero cross-loadings and residual correlations corresponding to the pre-specified regular CFA model provided a posterior predictive p-value of almost zero (

Table 1). The specification of small (close to zero) informative variances for cross-loadings ranging from 0.001 to 0.03 did not lead to an acceptable model fit based on PP p < 0.001. The addition of residual correlations produced almost perfect model fit for a larger prior (d=50) as shown by PP p values being close to 0.5 and confidence intervals symmetric about zero.

Table 2 results show acceptable model fit for small informative cross-loadings of 0.005 and residual correlations d = 200 as indicated by goodness of fit indices whilst being close to the BCFA-based CFA model (PP p = 0.144).

Table 2 shows factor loadings and factor correlation estimates for the BCFA and CFA model. All cross-loadings for the BCFA model were less than or equal to 0.1 and statistically non-significant in that 95% Bayesian credibility intervals covered zero. All hypothesised factor loadings were substantial and significant at p < 0.001 and factor correlation estimates were in the moderate range (0.409 – 0.662). For estimates of residual correlations, 95% (63/66) were statistically non-significant in that 95% Bayesian credibility intervals covered zero. Three residual correlations were statistically significant though ignorable in terms of statistical magnitude (<0.14) and practical implications. In conclusion, posterior predictive assessments of model fitness showed mostly ignorable discrepancies between BCFA and CFA models from a statistical and practical perspective. This provided additional support for a PIH four-factor solution using a standard CFA approach.

To assess the reliability of subscale scores for the BCFA 4-factor model with small variance priors, McDonald’s omega coefficients were calculated using unstandardised factor loadings and item residual variances. Coefficients (95 % Bayesian credible intervals) for the PIH subscales knowledge, partnership, management, and coping were 0.84 (0.79–0.88), 0.79 (0.73–0.84), 0.89 (0.85–0.91) and 0.84 (0.79–0.88), respectively. These values indicated that the subscales internal reliability in producing raw scores was in the acceptable range [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

40].

Discussion

In this study, a generic patient reported self-management measure, the PIH scale is validated for CHF. Prior to this, only 2 measures of self-management, both disease specific [Self-care Heart Failure Index (SCHFI) and European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS)] that have rigorous validity and reliability, psychometric testing in CHF [

7]. The PIH scale developed at a time where evidence was building for the effectiveness of CDSM, yet there were no instruments to assess their effectiveness [

13,

14]. The findings we present here are encouraging and advance the investigation of the psychometric properties of the PIH scale, validated across many languages and chronic conditions [

1,

13,

14,

15,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]

,, and now for the first time purposed for the spectrum of CHF syndromes.

Summary of PIH and Theoretical Framework, of Generic Self-Management, Scale

In the seminal paper, Battersby et.al [

14] showed that PIH completed by patients as a patient reported outcomes (PRO or patient self-rating) tool and interpreted by health professionals as marker of self-management capabilities to facilitate patients care. This preliminary investigation on the psychometric properties of the PIH supported face validity among patients, general practitioners, other health professionals (e.g. nurses); concept validity in foundations based on sound self-management definitions. The study also demonstrated reliability in both internal consistency and inter-rated reliability. The PIH structure then underwent factor analysis, and a stable and meaningful three factors underlying the overall scale core self-management, condition knowledge, and symptom monitoring [

14]. The authors themselves highlighted this sentinel works as preliminary due to the small sample size of 46 patients. Nonetheless the authors raised important points in the summation for future research including increasing the sample size and using other components of the scale such as the health worker prompted Cue and Response to improve the accuracy of PRO.

Since then, studies in diabetics, arthritis, chronic lung diseases, chronic liver disease, heart failure (including this study), and across multiple languages have supported this original claims. The theoretical framework, is validated, rigorously tested and has held up across a range of chronic conditions self-management [

1,

13,

14,

15,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], and it also has relevance for deficiencies reported in CDSM and CHF [

5,

11,

12]. The PIH scores patient across 4 self-management domains (knowledge, partnership in treatment, recognition and management of symptoms and coping) to develop a baseline of self-monitoring, self-tailoring and self-efficacy abilities. How this translates for generic chronic conditions versus disease specific conditions is an ongoing question.

Summary of Self-Management in Heart Failure and Comparing Relevant Research

A lot has changed in CHF landscape. Today comprehensive care (including rehabilitation) around guideline derived medical therapies (GDMT) [

3,

4] are delivered through an organised process, ensures timely and high uptake of prognostic therapies for stable patients. This is further supported during decompensation. This care improves all major cardiovascular events (MACE). The CHF syndrome has chronological characteristics, and the disease trajectory that has changed with the rapid therapeutic developments over the last several decades.

Nonetheless the arguments for self-management holds for CHF. In the first decade of this millennia, some important observations were highlighted. Riegel et.al studied 2080 adults from developed (United States, Australia) and developing nations (Thailand and Mexico), using the Self-Care of HF Index (SCHFI) all measures of self-management were inadequate, although higher in the developed nations. This study concluded that self-management interventions were greatly needed in across all groups [

8]. Importantly at this stage of 14 available clinical instruments to assess self-management only 2 were reliable and valid for measuring CHF self-management [

7]. Practical recommendations for self-management in CHF followed, which covered a generic range of health topics within a CHF context. The most specific aspects being symptom recognition and fluid and sodium management [

9]. With regards to research and translation of CDSM there are confounding characteristics that affecting self-management capabilities including comorbid conditions, psychological (mood, anxiety, cognitive and sleep disturbance) and physical functional status and demographics (health literacy, social isolation and support, socioeconomics). These factors could influence behavioural more than pharmacological therapies, the later which also receives greater emphasis in education and delivery.

The evidence that was published in that era, despite these issues that needed to be factored were encouraging trends, although without definitive gold standard results. These covered a range of outcomes reproducing optimal GDMT uptake [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49], improving readmissions and MACE [

50,

51], event free survival [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56], and age, quality of life and functional status [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Feng et.al performed meta-analysis on 20 randomised controlled trials (7 rated Grade A and 13 Grade B) enrolling 3459 patients with CHF showed that administered CDSM programs improved patient skill, quality of life, readmission rates, although this did not extend to mortality.

Table 3.

Bayesian models for CFA and using informative prior with cross-loadings and residual covariances.

Table 3.

Bayesian models for CFA and using informative prior with cross-loadings and residual covariances.

| |

|

|

BSEM- CFA

4-factor model |

|

|

|

|

BSEM with cross-loadings N (0, 0.005) and residual covariances IW(200*D,200 ) |

|

| Item |

K |

P |

M |

C |

|

K |

P |

M |

C |

| |

|

|

|

|

Loadings |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

0.916* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0.831* |

-0.019 |

0.037 |

0.013 |

| 2 |

0.918* |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

0.869* |

0.024 |

-0.020 |

-0.011 |

| 3 |

0 |

0.915* |

0 |

0 |

|

-0.040 |

0.538* |

0.065 |

-0.060 |

| 4 |

0 |

0.517* |

0 |

0 |

|

0.057 |

0.772* |

-0.036 |

0.012 |

| 5 |

0 |

0.551* |

0 |

0 |

|

0.022 |

0.854* |

-0.072 |

0.012 |

| 6 |

0 |

0.836* |

0 |

0 |

|

-0.063 |

0.604* |

0.082 |

0.017 |

| 7 |

0 |

0 |

0.860* |

0 |

|

0.024 |

0.008 |

0.906* |

-0.023 |

| 8 |

0 |

0 |

0.885* |

0 |

|

-0.003 |

0.009 |

0.850* |

0.045 |

| 9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.761* |

|

0.014 |

0.024 |

0.067 |

0.622* |

| 10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.950* |

|

-0.001 |

-0.026 |

-0.070 |

0.971* |

| 11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.964* |

|

-0.003 |

0.010 |

-0.019 |

0.915* |

| 12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.523* |

|

-0.020 |

0.001 |

0.101 |

0.414* |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Factor correlations |

|

|

|

|

| K |

- |

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

| P |

0.275* |

- |

|

|

|

0.641* |

- |

|

|

| M |

0.350* |

0.842* |

- |

|

|

0.409* |

0.662* |

- |

|

| C |

0.540* |

0.358* |

0.609* |

- |

|

0.576* |

0.641* |

0.597* |

- |

The study size, only 4 studies enrolled more than 200 patients, with at least 100 in control or treatment arm. The follow-up periods of the included studies ranged from 6 to 12 months. The CDSM intervention delivered varied in location, health staff, duration and intensity [

60]. Thus, the statements for authoritative consensus on this topic, remain accurate. The early positions in 2009 and 2017 by Reigel et.al “…Although there are many nuances to the relationships between self-care and outcomes, there is strong evidence that self-care is effective in achieving the goals of the treatment plan and cannot be ignored. As such, greater emphasis should be placed on self-care in evidence-based guidelines…”, remain accurate [

8,

9,

11]. However, the nuances remain, while great emphasis was encouraged, it is understandable that, unlike the pharmaceutical and device trials, without consistent baseline CDSM program standards, its delivery and follow-up it is not feasible to achieve the Grade 1A or gold standard finding to comment on MACE, for current consensus statements to provide [

3,

4].

Specifically, to the Flinders Program (FP), this study has shown that the generic CDSM principles are valid. It has been many decades since Wagner’s Chronic Care Model and the FP, nonetheless the domains describe in the previous paragraph remain relevant as surrogates of patient perception of behaviour and are valid. The next steps in integrating generic and disease specific tools are topics for future studies.

Current Findings and Future Research

The findings from this study are promising and provide support for advancing further research into self-management and self-management support in CHF. Firstly, it does appear that a generic tool can be utilised in a heterogenous population of HFrEF, HFpEF, high comorbidity burden and diverse demography with good internal validity. This ticks an important box for self-administered assessments for CDSM instruments. Alongside this paper we have completed a study in HFrEF which explores the external validity of this tool. The details are discussed further in that paper [

24].

It is interesting to note the simplicity of the concepts as it flowed from, firstly, base finding on knowledge and CDSM efficacy. These results are consistent with the theoretical proposition that limited education interventions do little to influence health related behaviours and skills. The PIH is part of a more comprehensive Flinders CDSM program for e.g The Cue and Response form is useful tool to follow the PIH in identifying any deficits/issues at the beginning and end of an assessment. The PIH scale is important in gauging a patient’s perspective, so long as they understood the scale and questions. This simple and complex link in these tools is an area of future importance; secondly, the role of dyads in CDSM. The dyads are patient and health professionals and patient and dedicated carer in the journey of assessing baseline and progress (judging scales and levels) and with an ease of achieving an agreed knowledge, forming partnerships, planning, symptom monitoring and management and coping. This internal validation leaves room to expand on the clinical bedside workings of this generic CDSM tool.

Limitations

The study presents data from a single clinic from a consecutive screened and unran-domized population for HFrEF and HEpEF. Patients who were HFpEF have some gaps in baseline social data. While not relevant for assessing preliminary internal validity, broader demographic, cultural and co-morbidity samples will be required to confirm the study findings. greater trial controls will be required for future works. Questions of concurrent validity, reliability, reproducibility in a larger multisite clinical population of CHF, requires more advanced study designs including randomisation and follow up data to assess whether PIH is a valid measure of change in self-management, clinical and quality of life outcomes over time.

5. Conclusions

In this study we describe the first validation of the PIH scale, on the spectrum of heart failure syndromes (HRrEF and HFpEF). The PIH scale, a component of the Flinders Program, is validated across a range of chronic diseases and now CHF. This study has confirmed the reliability, validity and dimensionality of the PIH as a patient reported tool for measuring self-management capabilities for key domains, including collective self-efficacy for the CHF syndrome. For the next step, in other chronic diseases, studies have shown that the translation of patient scores, to tailored self-management support with the CFPI, improves patients’ knowledge, skills to disease and case management. This study lays a foundation to assess this concept for CHF. Importantly it also raises the questions on the steps required to introduce CHF (disease specific) aspects within the generic program. The traditional CHF approach has been predominately disease specific. This is an area that requires further exploration in the future.

Author Contributions

PI: FH, MB and MdC participated in research design, data analysis, and writing of the paper. PI, MB participated in performance of the research and data collection. PI, FH, MB, MdC provided advice and support. PI assisted DS in statistical analysis/ All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Support from relevant University and clinic administration.

Conflicts of Interest

Professor Malcolm Battersby is co-inventor of the “Flinders Model of Chronic Condition Self-Management” and has received competitive and Federal Government funding for research in chronic condition self-management. All other authors have received government and non-governmental funding. None pose a conflict of interest for this publication.

References

- Ramachandran, J.; Smith, D.; Woodman Muller, K.; Wundke, R.; McCormick, R.; et al. Psychometric validation of the Partners in Health scale as a self-management tool in patients with liver cirrhosis. Internal Medicine Journal. 2021, 51, 2104–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, V.L. Epidemiology of heart failure: a contemporary perspective. Circ Res. 2021, 128, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022, 79, e263–e421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group, 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. EHJ. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Breathett, K.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Adults With Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2527–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.H. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, J.; Worrall-Carter, L.; Driscoll, A.; Stewart, S. Measuring self-care in chronic heart failure: a review of the psychometric properties of clinical instruments. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009, 24, E10–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Driscoll, A.; Suwanno, J.; Moser, D.K.; Lennie, T.A.; Chung, M.L.; et al. Heart Failure Self-Care in Developed and Developing Countries. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2009, 15, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Lee, C.; Dickson, V. Self care in patients with chronic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011, 8, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainscak, M.; Blue, L.; Clark, A.; et al. Self-care management of heart failure: practical recommendations from the Patient Care Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2011, 13, 115–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Moser, D.K.; Buck, H.G.; et al. Self-Care for the Prevention and Management of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaarsma, T.; Hill, H.; Bayes-Genis, A.; et al. Self-care of heart failure patients: practical management recommendations from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.flindersprogram.com.

- Battersby, M.; Ask, A.; Reece, M.; Markwick, M.; Collins, J. The partners in health scale: the development and psychometric properties of a generic assessment scale for chronic condition self-management? Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2003, 9, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.W.; Petkov, J.; Misan, G.; Warren, K.; Fuller, J.; Battersby, M.; et al. Self-management support and training for patients with chronic and complex conditions improves health related behaviour and health outcomes. Australian Health Review. 2008, 32, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyngkaran, P.; Toukhsati, S.R.; Harris, M.; Connors, C.; Kangaharan, N.; Ilton, M.; et al. Self Managing Heart Failure in Remote Australia - Translating Concepts into Clinical Practice. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016, 12, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, P.A.; Gough, L.L. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health. 2014, 104, e25–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrijver, J.; Lenferink, A.; Brusse-Keizer, M.; Zwerink, M.; van der Valk, P.D.L.P.M.; van der Palen, J.; et al. Self-management interventions for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022, CD002990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, J.D. A review of web-based chronic disease self-management for older adults. Gerontechnology. 2017, 16, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.; Dennis, S.; Hasan, I.; et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrante, J.P.; Wells, M.T.; Peterson, J.C. Interventions to Support Behavioral Self-Management of Chronic Diseases. Annual Review of Public Health. 2019, 40, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, M.; Song, R. Effects of self-management programs on behavioral modification among individuals with chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0254995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, S.; Mc Carthy, V.J.C.; Savage, E. Frameworks for self-management support for chronic disease: a cross-country comparative document analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018, 18, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyngkaran, P.; Hanna, F.; Andrew, S.; Horowitz, J.D.; Battersby, M.; De Courten, M.P. Comparison of short and long forms of the Flinders program of chronic disease SELF-management for participants starting SGLT-2 inhibitors for congestive heart failure (SELFMAN-HF): protocol for a prospective, observational study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023, 10, 1059735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battersby, M.; Korff, M.V.; Schaefer, J.; et al. Twelve evidence-based principles for implementing self-management support in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2010, 36, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkov, J.; Harvey, P.; Battersby, M. The internal consistency and construct validity of the Partners in Health Scale:validation of a patient rated chronic condition self-management measure. Qual Life Res 2010, 19, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenferink, A.; Effing, T.; Harvey, P.; et al. Construct validity of the Dutch version of the 12-item Partners in Health Scale: measuring patient self-management behaviour and knowledge in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 2016, 11, e161595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battersby, M.; Harris, M.; Smith, D.; Reed, R.; Woodman, R. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of the Flinders Program of chronic condition management in community health care services. Patient. Educ Couns 2015, 98, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.; Harvey, P.; Lawn, S.; Harris, M.; Battersby, M. Measuring chronic condition self-management in an Australian community: factor structure of the revised Partners in Health (PIH) scale. Qual Life Res 2017, 26, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudon, M.; Chouinard, M.C.; Krieg, C.; et al. The French adaptation and validation of the Partners in Health(PIH)Scale among patients with chronic conditions seen in primary care. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0224191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, M.K.; Ahn, J.W.; Park, Y.H.; et al. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Partners in Health Scale(PIH-K). J Korean Crit Care Nurs 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T. Bayesian structural equation modeling: a more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychol Methods. 2012, 17, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B.; Morin, A.J.S. Bayesian structural equation modeling with cross-loadings and residual covariances: Comments on Stromeyer et al. Journal of Management. 2015, 41, 1561–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depaoli, S. (2021). Bayesian structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

- Zhang, Z.; Hamagami, F.; Lijuan Wang, L.; Nesselroade, J.R.; Grimm, K.J. Bayesian analysis of longitudinal data using growth curve models. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007, 31, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depaoli, S.; Rus, H.M.; Clifton, J.P.; van de Schoot, R.; Tiemensma, J. An introduction to Bayesian statistics in health psychology. Health Psychology Review. 2017, 11, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelman, A.; Rubin, D.B. Inference from Iterative Simulation Using Multiple Sequences. Statistical Science. 1992, 7, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T.; Muthén, B. Advances in Bayesian model fit evaluation for structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2021, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.t.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalter, D.J.; Best, N.G.; Carlin, B.P.; Van Der Linde, A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 2002, 64, 583–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D. Thanks coefficient alpha, we'll take it from here. Psychol Methods. 2018, 23, 412–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. (1998-2017). Mplus Users Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén, & Muthén.

- Kim, Y.J.; Soeken, K.L. A meta-analysis of the effect of hospital-based case management on hospital length-of-stay and readmission. Nurs Res. 2005, 54, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K. Disease management programs for heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2010, 12, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savard, L.A.; Thompson, D.R.; Clark, A.M. A meta-review of evidence on heart failure disease management programs: the challenges of describing and synthesizing evidence on complex interventions. Trials. 2011, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whellan, D.J.; Hasselblad, V.; Peterson, E.; O’Connor, C.M.; Schulman, K.A. Metaanalysis and review of heart failure disease management randomized controlled clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2005, 149, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovicic, A.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.M.; Straus, S.E. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshman, S.L.; Charrois, T.L.; Simpson, S.H.; McAlister, F.A.; Tsuyuki, R.T. Pharmacist care of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohler, A.; Januzzi, J.L.; Worrell, S.S.; Osterziel, K.J.; Gazelle, G.S.; Dietz, R.; et al. A systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and heterogeneity of disease management programs in congestive heart failure. J Card Fail. 2006, 12, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, M.A.; Konstam, V. Heart failure disease management a sustainable energy source for the health care engine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 56, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrante, D.; Varini, S.; Macchia, A.; Soifer, S.; Badra, R.; Nul, D.; et al. Long-term results after a telephone intervention in chronic heart failure: DIAL (Randomized Trial of Phone Intervention in Chronic Heart Failure) follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 56, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.R.; Moser, D.K.; Chung, M.L.; Lennie, T.A. Objectively measured, but not self-reported, medication adherence independently predicts event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008, 14, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; Moser, D.K.; De Jong, M.J.; Rayens, M.K.; Chung, M.L.; Riegel, B.; Lennie, T.A. Defining an evidence-based cutpoint for medication adherence in heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009, 157, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; Corley, D.J.; Lennie, T.A.; Moser, D.K. Effect of a medication-taking behavior feedback theory-based intervention on outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- vanderWal, M.H.; vanVeldhuisen, D.J.; Veeger, N.J.; Rutten, F.H.; Jaarsma, T. Compliance with non-pharmacological recommendations and outcome in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2010, 31, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.S.; Moser, D.K.; Lennie, T.A.; Riegel, B. Event-free survival in adults with heart failure who engage in self-care management. Heart Lung. 2011, 40, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, H.G.; Lee, C.S.; Moser, D.K.; Albert, N.M.; Lennie, T.; Bentley, B.; et al. Relationship between self-care and health-related quality of life in older adults with moderate to advanced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012, 27, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.P.; Lin, L.C.; Lee, C.M.; Wu, S.C. Effectiveness of a self-care program in improving symptom distress and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients: a preliminary study. J Nurs Res. 2011, 19, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, E.; Leonard, K.J.; Cafazzo, J.A.; Masino, C.; Barnsley, J.; Ross, H.J. Self-care and quality of life of heart failure patients at a multidisciplinary heart function clinic. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011, 26, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Qu, Z.; Zheng, S. Effect of self-management intervention on prognosis of patients with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis. Nurs Open. 2023, 10, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.S.; Thompson, D.R.; Lee, D.T. Disease management programmes for older people with heart failure: crucial characteristics which improve post-discharge outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2006, 27, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).