Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design Ethics Approval

2.2. Patients’ Categorization

2.3. Heart Failure Diagnosis

2.4. Collected Information

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographics

3.2. Index Hospitalization: Patient Profiles & Clinical Trajectories

3.3. Mortality and Re-Hospitalization Rate

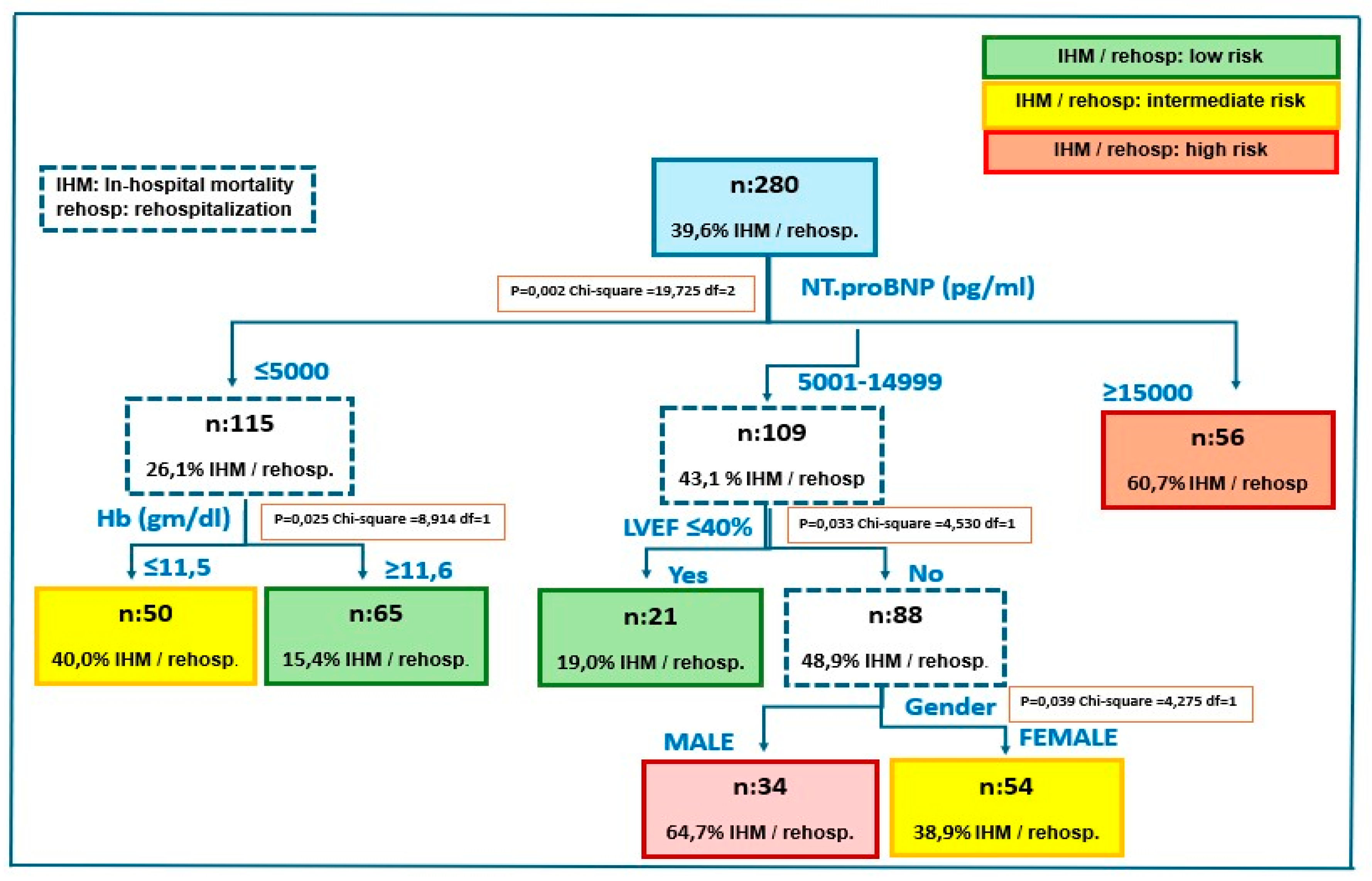

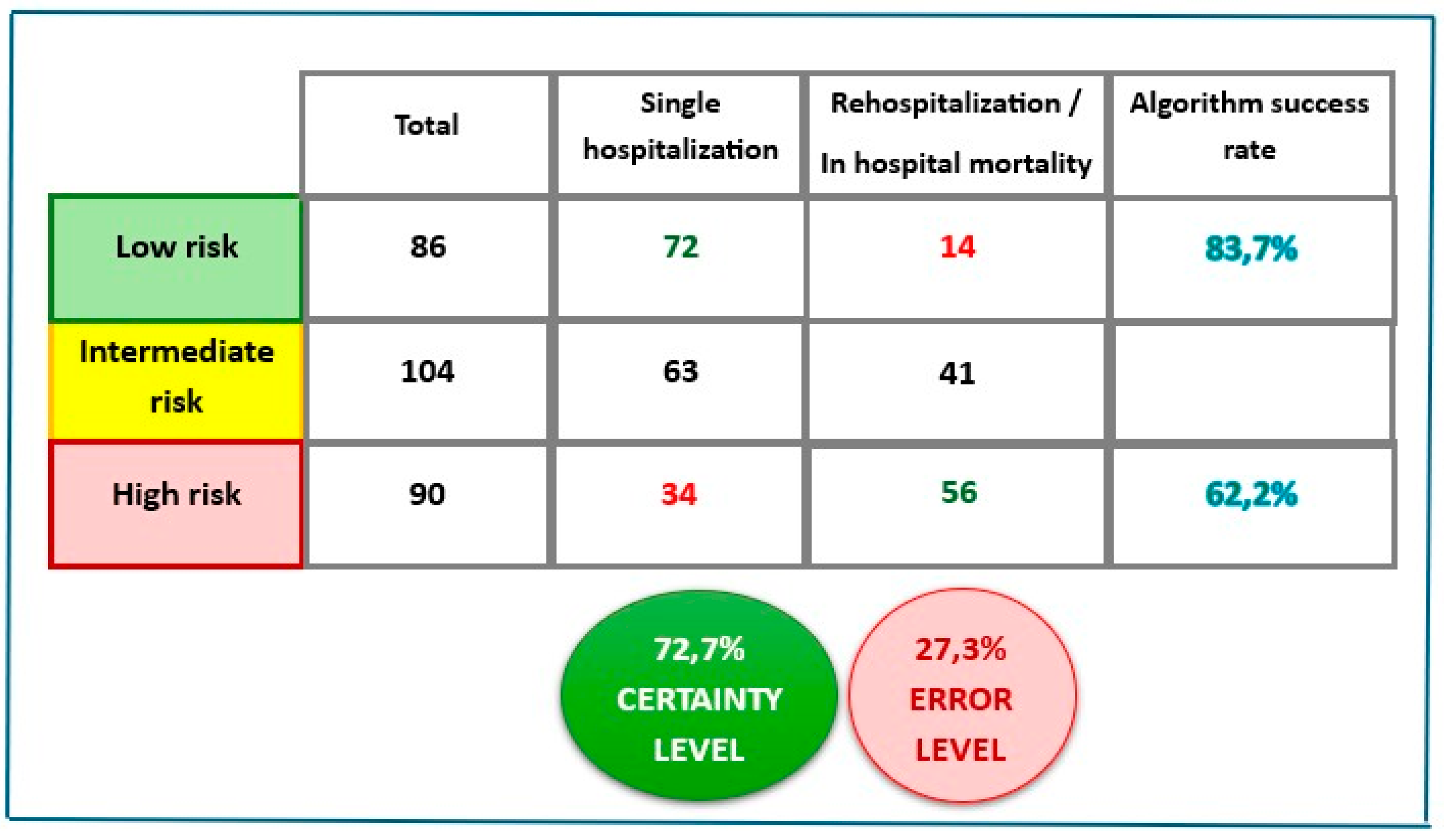

3.4. Multivariable Analysis

4. Discussion

Summary of Main Results and Comparison with Published References

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Ahmad, T.; Alexander, K.M.; Baker, W.L.; Bosak, K.; Breathett, K.; Fonarow, G.C.; Heidenreich, P.; Ho, J.E.; Hsich, E.; et al. Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America. J Card Fail. 2023, 29, 1412–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, B.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Kaplan, R.M.; Senni, M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Chioncel, O.; Butler, J.; Gheorghiade, M. Lessons learned in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoaib, A.; Farag, M.; Nolan, J.; Rigby, A.; Patwala, A.; Rashid, M.; Kwok, C.S.; Perveen, R.; Clark, A.L.; Komajda, M.; Cleland, J.G.F. Mode of presentation and mortality amongst patients hospitalized with heart failure? A report from the First Euro Heart Failure Survey. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019, 108, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrosciano, C.; Horton, D.; Air, T.; Tavella, R.; Beltrame, J.F.; Zeitz, C.J.; Krumholz, H.M.; Adams, R.J.T.; Scott, I.A.; Gallagher, M.; et al. Frequency, trends and institutional variation in 30-day all-cause mortality and unplanned readmissions following hospitalization for heart failure in Australia and New Zealand. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidge, J.; Halling, A.; Ashfaq, A.; Etminani, K.; Agvall, B. Clinical characteristics at hospital discharge that predict cardiovascular readmission within 100 days in heart failure patients—An observational study. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. 2023, 16, 200176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Horwood, C.; Hakendorf, P.; Thompson, C. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with heart failure discharged from different specialty units in Australia: An observational study. QJM 2022, 115, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, G.; Covino, M.; Burzo, M.L.; Della Polla, D.A.; Franceschi, F.; Mebazaa, A.; Gambassi, G. Clinical Characteristics and Predictors of In-Hospital Mortality among Older Patients with Acute Heart Failure. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.; Lopes Ramos, R.; Mendonça, D.; Teixeira, L. One-year mortality after hospitalization for acute heart failure: Predicting factors (PRECIC study subanalysis). Rev Port Cardiol. 2023, 42, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, A.; Nagatomo, Y.; Yukino-Iwashita, M.; Nakazawa, R.; Yumita, Y.; Taruoka, A.; Takefuji, A.; Yasuda, R.; Toya, T.; Ikegami, Y.; et al. Sex Differences in Cardiac and Clinical Phenotypes and Their Relation to Outcomes in Patients with Heart Failure. J Pers Med. 2024, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivetti, G.; Giordano, G.; Corradi, D.; Melissari, M.; Lagrasta, C.; Gambert, S.R.; Anversa, P. Gender differences and aging: Effects on the human heart. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995, 26, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworatzek, E.; Baczko, I.; Kararigas, G. Effects of aging on cardiac extracellular matrix in men and women. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2016, 10, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdiani, V.; Panigada, G.; Fortini, A.; Masotti, L.; Meini, S.; Biagi, P. The heart failure in internal medicine in Tuscany: The SMIT study. Italian Journal of Medicine 2015, 9, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuda, A.; Berner, J.; Malgorzata, L. The journey of the heart failure patient based on data from a single center. Adv Clin Exp Med 2019, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Anker, S.D.; Maggioni, A.P.; Coats, A.J.; Filippatos, G.; Ruschitzka, F.; Ferrari, R.; Piepoli, M.F.; Delgado Jimenez, J.F.; Metra, M.; et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donal, E.; Lund, L.H.; Oger, E.; Hage, C.; Persson, H.; Reynaud, A.; Ennezat, P.V.; Bauer, F.; Sportouch-Dukhan, C.; Drouet, E.; et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction included in the Karolinska Rennes (KaRen) study. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014, 107, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, W.T.; Fonarow, G.C.; Albert, N.M.; Stough, W.G.; Gheorghiade, M.; Greenberg, B.H.; O’Connor, C.M.; Sun, J.L.; Yancy, C.W.; Young, J.B.; Young, J.B.; OPTIMIZE-HF Investigators and Coordinators. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure: Insights from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52, 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, K.F.Jr.; Fonarow, G.C.; Emerman, C.L.; LeJemtel, T.H.; Costanzo, M.R.; Abraham, W.T.; Berkowitz, R.L.; Galvao, M.; Horton, D.P. ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: Rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am Heart J. 2005, 149, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Ide, T.; Kaku, H.; Matsushima, S.; Tohyama, T.; Enzan, N.; Funakoshi, K.; Sumita, Y.; Nakai, M.; Nishimura, K.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hospitalized patients with heart failure from the large-scale Japanese registry of acute decompensated heart failure (JROADHF). Circ J. 2021, 85, 1438–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoupil, J.; Hrečko, J.; Čermáková, E.; Adamcová, M.; Pudil, R. Characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted for acute heart failure in a single-centre study. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 2249–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, F.M.; Joy, A.; Nellimala, N.J.; Bharathy, K.M.; Prakash, T.V.; John, K.V.; Mathuram, A.J.; Sathyendra, S.; Abraham, O.C.; Ramya, I.; et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients admitted with Congestive Heart failure (HF) in a general medical ward—A case-control study from a tertiary care centre in South India. CHRISMED Journal of Health and Research 2021, 8, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orso, F.; Pratesi, A.; Herbst, A.; Baroncini, A.C.; Bacci, F.; Ciuti, G.; Berni, A.; Tozzetti, C.; Nozzoli, C.; Pignone, A.M.; et al. Acute heart failure in the elderly: Setting related differences in clinical features and management. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2021, 18, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambrosy, A.P.; Fonarow, G.C.; Butler, J.; Chioncel, O.; Greene, S.J.; Vaduganathan, M.; Nodari, S.; Lam, C.S.P.; Sato, N.; Shah, A.N.; Gheorghiade, M. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: Lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmarajan, K.; Hsieh, A.F.; Lin, Z.; Bueno, H.; Ross, J.S.; Horwitz, L.I.; Barreto-Filho, J.A.; Kim, N.; Bernheim, S.M.; Suter, L.G.; et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013, 309, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sager, R.; Lindstedt, I.; Edvinsson, L.; Edvinsson, M.L. Increased mortality in elderly heart failure patients receiving infusion of furosemide compared to elderly heart failure patients receiving bolus injections. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2020, 17, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Wideqvist, M.; Cui, X.; Magnusson, C.; Schaufelberger, M.; Fu, M. Hospital readmissions of patients with heart failure from real world: Timing and associated risk factors. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omary, M.S.; Khan, A.A.; Davies, A.J.; Fletcher, P.J.; Mcivor, D.; Bastian, B.; Oldmeadow, C.; Sverdlov, A.L.; Attia, J.R.; Boyle, A.J. Outcomes following heart failure hospitalization in a regional Australian setting between 2005 and 2014. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udani, K.; Patel, D.; Mangano, A. A Retrospective Study of Admission NT-proBNP Levels as a Predictor of Readmission Rate, Length of Stay and Mortality. HCA Healthc J Med. 2021, 2, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voors, A.A.; Ouwerkerk, W.; Zannad, F.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Samani, N.J.; Ponikowski, P.; Ng, L.L.; Metra, M.; Ter Maaten, J.M.; Lang, C.C.; et al. Development and validation of multivariable models to predict mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.T.; Tseng, Y.T.; Chu, T.W.; Chen, J.; Lai, M.Y.; Tang, W.R.; Shiao, C.C. N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) -based score can predict in-hospital mortality in patients with heart failure. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 29590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total HFH (n: 420) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary HF (n/%) | 109 (27%) | Secondary HF (n/%) | 301 (73%) |

| Causes (n/%): | Causes (n/%): | ||

| • New-onset AF | 29 (26%) | • Respiratory infection5 | 116 (39%) |

| • Valvular disease1 | 22 (20%) | • Respiratory insufficiency6 | 60 (20%) |

| • Non-compliance 2 | 17 (16%) | • Worsening renal function7 | 49 (16%) |

| • ACS | 14 (13%) | • Sepsis8 | 27 (9%) |

| • Worsening AF3 | 9 (8%) | • Urinary infection | 19 (6%) |

| • Bradyarrhythmia | 8 (7%) | • Anemia/GI bleeding | 11 (4%) |

| • Cardiac amyloidosis 4 | 6 (6%) | • Hip fractures | 7 (2%) |

| • Pulmonary embolism | 3 (3%) | • Ascitic decompensation | 5 (1,6%) |

| • Aortic dissection | 1 (1%) | • Stroke | 5 (1,6%) |

| • Other | 2 (0,8%) |

| Item | All patients | Female | Male | p between genders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||

| n | 280 (100%) | 152 (54%) | 128 (46%) | |

| Age: years± SD, (range) | 82,11 ± 9,9 (41-99) | 84,51 ± 8,6 (46-99) | 79,26 ±10,5 (41-96) | <0,0001 |

| BMI: Kg/m2± SD, (range) | 28,4 ± 5,6 (16 -49,1) | 28,4 ± 5,8 (16 -49,1) | 28,5 ± 5,3 (17,6 -44,1) | 0,9486 |

| Age distribution | ||||

| ≤ 59 years: n (%) | 10 (4%) | 2 (1%) | 8 (6%) | |

| 60-69 years: n (%) | 18 (6%) | 8 (5%) | 10 (8%) | |

| 70-79 years: n (%) | 65 (23%) | 31 (20%) | 34 (27%) | |

| 80-89 years: n (%) | 130 (46%) | 68 (45%) | 62 (48%) | |

| ≥90 years: n (%) | 57 (20%) | 43 (28%) | 14 (11%) | |

| Etiology | ||||

| CAD n (%) | 55 (20%) | 22 (14%) | 33 (26%) | 0,0199 |

| Non-CAD n (%) | 225 (80%) | 130 (86%) | 95 (74%) | |

| Cardiac rhythm | ||||

| SR: n (%) | 134 (48%) | 73 (48%) | 61 (48%) | 0,9510 |

| AF: n (%) | 119 (43%) | 67 (44%) | 52 (41%) | 0,5619 |

| Pacemaker: n (%) | 27 (9%) | 12 (8%) | 15 (11%) | 0,2892 |

| LVEF: % ± SD, (range) | 53,7 ± 12,3 (19-76) | 56,8 ±10,2 (20-76) | 50,0 ± 13,5 (19-76) | |

| HFrEF: n (%) | 57 (20%) | 17 (11%) | 40 (31%) | <0,0001 |

| HFmrEF: n (%) | 30 (11%) | 13 (9%) | 17 (13%) | 0,2115 |

| HFpEF: n (%) | 193 (69%) | 122 (80%) | 71 (55%) | <0,0001 |

| Comorbidity | All Patients | Female | Male | p between genders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 242 (86%) | 133 (88%) | 109 (85%) | 0,5724 |

| DM | 130 (46%) | 63 (41%) | 67 (52%) | 0,0694 |

| COPD | 127 (45%) | 53 (35%) | 74 (58%) | 0,0001 |

| SAS | 52 (19%) | 21 (14%) | 31 (24%) | 0,0287 |

| Stroke | 50 (18%) | 30 (20%) | 20 (16%) | 0,3689 |

| CKD | 42 (15%) | 22 (14%) | 20 (16%) | 0,7896 |

| Hypothyroidism | 33 (12%) | 25 (16%) | 8 (6%) | 0,0063 |

| Active cancer | 19 (7%) | 7 (5%) | 12 (9%) | 0,1251 |

| ≥3 comorbidities | 136 (49%) | 68 (45%) | 68 (53%) | 0,1631 |

| Items | All Patients |

Single Hospitalization |

Rehospitalizations | Death first hospitalization |

p between hospitalizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 280 (100%) | 169 (60%) | 73 (26%) | 38 (14%) | |

| Female: n (%) | 152 (54%) | 97 (57%) | 33 (45%) | 22 (58%) | 0,1952 |

| Male: n (%) | 128 (46%) | 72 (43%) | 40 (55%) | 16 (42%) | |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Age: years, ± SD, (range) | 82,1 ± 9,9 (41-99) | 80,5 ± 10,9 (41-99) | 83,8 ± 7,4 (55-98) | 85,9 ± 7,2 (69-96) | 0,0018 |

| BMI: Kg/m2± SD, (range) | 28,4 ± 5,5 (16-49,1) | 28,5 ± 5,9 (17,3-49,1) | 28,2 ± 5,1 (16,0 -40,0) | 28,3 ± 4,6 (20,1-42,3) | 0,8858 |

| SBP: mmHG, ± SD, (range) | 135,3 ± 26,9 (60-230) | 136,6 ± 27,0 (65-230) | 134,3 ± 27,1 (60-195) | 131,2 ± 26,4 (70-200) | 0,4984 |

| DBP: mmHG, ± SD, (range) | 76,3 ± 14,4 (30-115) | 77,4 ± 14,2 (40-110) | 75,3 ± 14,9 (30-115) | 73,3 ± 14,0 (40-100) | 0,2226 |

| Cr: mg/dl, ± SD, (range) | 1,52 ± 1,0 (0,42-6,63) | 1,40 ± 0,9 (0,42-6,24) | 1,55 ± 0,8 (0,47-5,09) | 2,01 ± 1,5 (0,48-6,63) | 0,0022 |

| eGFR: mL/min/1.73 m2, ± SD, (range) | 47,8 ± 21,9 (15-90) | 50,9 ± 21,8 (15-90) | 45,3 ± 20,8 (15-90) | 38,9 ± 22,2 (15-90) | 0,0047 |

| Hb: mg/dl ± SD, (range) | 11,6 ± 2,2 (3,5-17,3) | 11,9 ± 2,3 (4,8-17,3) | 11,3 ± 2,2 (3,5-16,4) | 11,2 ± 2,0 (7,0-16,5) | 0,0447 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/ml) median (IQR) | 9938 (8841-11035) | 8264 (6981-9547) | 10084 (8083-12085) | 17101 (13623-20579) | <0,0001 |

| Etiology | |||||

| CAD | 55 (20%) | 33 (20%) | 19 (26%) | 4 (8%) | 0,0742 |

| Non-CAD | 225 (80%) | 136 (80%) | 54 (74%) | 35 (92%) | |

| Cardiac rhythm | |||||

| SR: n (%) | 134 (48%) | 90 (53%) | 25 (34%) | 19 (50%) | 0,0237 |

| AF: n (%) | 119 (43%) | 68 (40%) | 38 (52%) | 13 (34%) | 0,1264 |

| Pacemaker: n (%) | 27 (9%) | 11 (7%) | 10 (14%) | 6 (16%) | 0,0854 |

| LVEF: % ± SD, (range) | 53,7 ±12,3 (19-76) | 53,4 ± 12,9 (20-72) | 54,8 ± 11,3 (19-76) | 53,1 ± 11,4 (34-76) | |

| HFrEF: n (%) | 57 (20%) | 38 (22%) | 10 (14%) | 9 (24%) | 0,2577 |

| HFmrEF: n (%) | 30 (11%) | 14 (8%) | 11 (15%) | 5 (13%) | 0,2578 |

| HFpEF: n (%) | 193 (69%) | 117 (69%) | 52 (71%) | 24 (63%) | 0,6798 |

| HF cause | |||||

| Primary: n (%) | 87 (31%) | 63 (37%) | 18 (25%) | 6 (16%) | 0,0134 |

| Secondary: n (%) | 193 (69%) | 106 (63%) | 55 (75%) | 32 (84%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).