1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a syndrome characterized by symptoms and signs caused by structural and/or functional cardiac abnormalities, corroborated by elevated levels of natriuretic peptides and evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion [

12]. HF affects 64.3 million people worldwide, representing 1% of the global population. Ischemic heart disease is the most frequent etiology, accounting for 26.5% of cases [

3]. The 30-day mortality rate is estimated at 2%, while the five-year mortality rate can reach 50–75% [

4].

HF generates high healthcare costs. A systematic review, which included 16 international studies between 2004 and 2016, estimated that the lifetime medical care cost for HF is

$126,819 per patient [

5]. In Chile, the situation is similar; in 2014, 1% of all hospital discharges were due to HF, according to the Department of Epidemiology and Health Information (DEIS) [

6].

HF can be classified in multiple ways, such as by ejection fraction, affected ventricle, or underlying etiology. However, a key classification is based on the urgency of medical attention required: acute or chronic HF. Acute heart failure (AHF) is defined by the need for urgent medical attention and hospitalization to initiate or optimize treatment [

7].

The European Society of Cardiology reports that one-year mortality for AHF patients is 23.6%, while the combined outcome of death or hospitalization within one year of discharge is 40.1% [

8]. The rehospitalization rate is up to 25% within 30 days post-discharge [

9] and 35–40% at one year [

10].

Historically, the main factors associated with mortality in AHF were systolic blood pressure <115 mmHg, blood urea nitrogen >43 mg/dL, and plasma creatinine >2.75 mg/dL [

10]. Recently, additional risk factors include male gender, age >80 years, dementia, cancer, atrial fibrillation (AF), kidney injury, severe anemia, and non-use of beta-blockers. Other factors, such as NT-ProBNP and QRS duration, are also predictive of mortality [

11], as are echocardiographic parameters like the E/e' ratio and global longitudinal strain [

12].

In Chile, there are no specific studies evaluating mortality or risk factors associated with AHF, with most data being extrapolated from international literature.

The primary objective of this study was to describe the mortality of patients hospitalized for AHF at a high-complexity hospital in Santiago, Chile, within 12 months of admission.

Secondary objectives included characterizing the cohort in terms of epidemiology, treatments administered during hospitalization, and discharge prescriptions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Study Design

The University of Chile’s Clinical Hospital is a high-complexity university hospital located in the northern area of Santiago, the capital of Chile. Its cardiovascular center manages highly complex cardiac diseases, including surgical, percutaneous, electrophysiological, and clinical conditions, in patients with both public and private health insurance, sourced from the hospital's own geographic area as well as from other regions of the city and country. A retrospective cohort study was conducted based on records of admissions to the coronary intensive care unit with a diagnosis of AHF between 2017 and 2019. Clinical, social, cardiological, and therapeutic variables were considered, along with respective death records. The study was approved by both the hospital’s Clinical Research Support Office and its Scientific Ethics Committee.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The main inclusion criterion was the diagnosis of AHF upon admission to the coronary care unit, established by a cardiologist, with patients aged over 18 years. Exclusion criteria included the presence of concomitant severe non-cardiological respiratory conditions (e.g., pneumonia, interstitial lung disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), a condition with a life expectancy of less than one year (e.g., advanced cancer, terminal HF), or death due to SARS-COV2.

2.3. Data Extraction and Variable Recording

Data extraction was performed by the research team from electronic medical records, following strict confidentiality and quality protocols to ensure accuracy and avoid bias. Epidemiological, clinical, cardiological, and therapeutic variables were recorded. Statistical analysis was conducted using R Studio.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data cleaning and identification of missing values (NAs) were performed initially. Variables with a significant proportion of missing values (≥50%) were excluded from the analysis due to the potential bias. For variables with less than 50% missing values, imputation was conducted using linear regression for continuous variables and classification for categorical ones. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and inferential analysis was carried out using logistic, logarithmic, or Poisson regression, selecting the best-fit model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Association measures were calculated (Odds Ratio -OR-, Risk Ratio -RR-, or Hazard Ratio -HR-) according to the type of regression.

3. Results

A total of 184 patients were included, with a mean age of 72.5 years, 56% male, and a median follow-up of 12 months (Other characteristics are in

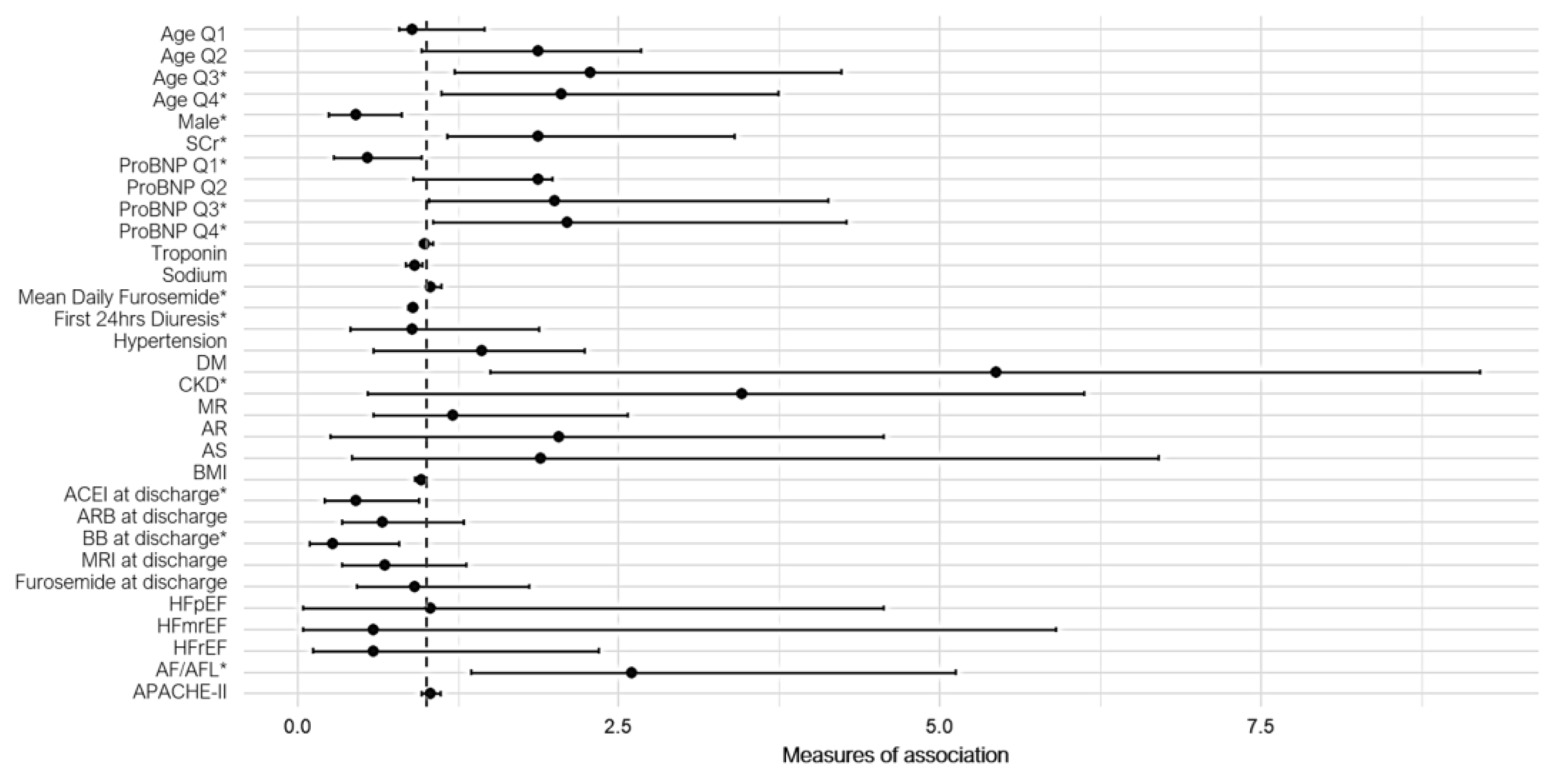

Table 1). The overall mortality rate at 12 months was 22.7%, with 35% of deaths attributed to cardiac causes. Significant risk factors included advanced age (HR 2.28, 95% CI: 1.22-4.23; p<0.05), elevated plasma creatinine at admission (OR 1.87, 95% CI: 1.16-3.40; p<0.05), and NT-ProBNP levels exceeding 4140 pg/mL (RR 2.0, 95% CI: 1.02-4.13; p<0.05). Additional factors such as chronic kidney disease (OR 5.44, 95% CI: 1.5-9.3; p<0.05), atrial fibrillation/flutter (OR 2.74, 95% CI: 1.30-5.76; p<0.05), and higher daily doses of furosemide (OR 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01-1.04) were also associated with increased mortality.

Conversely, protective factors included ACEi and BB use at discharge (OR 0.45, 95% CI: 0.21-0.94; p<0.05, and OR 0.27, 95% CI: 0.09-0.79, respectively), NT-ProBNP levels below 3220 pg/mL (RR 0.54, 95% CI: 0.28-0.96; p<0.05), eunatremia (OR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84-0.97), and high diuresis within the first 24 hours (OR 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97-0.99).

Figure 1 summarizes the association measures derived from the univariate regression models.

3.2. Figures, Tables and Schemes

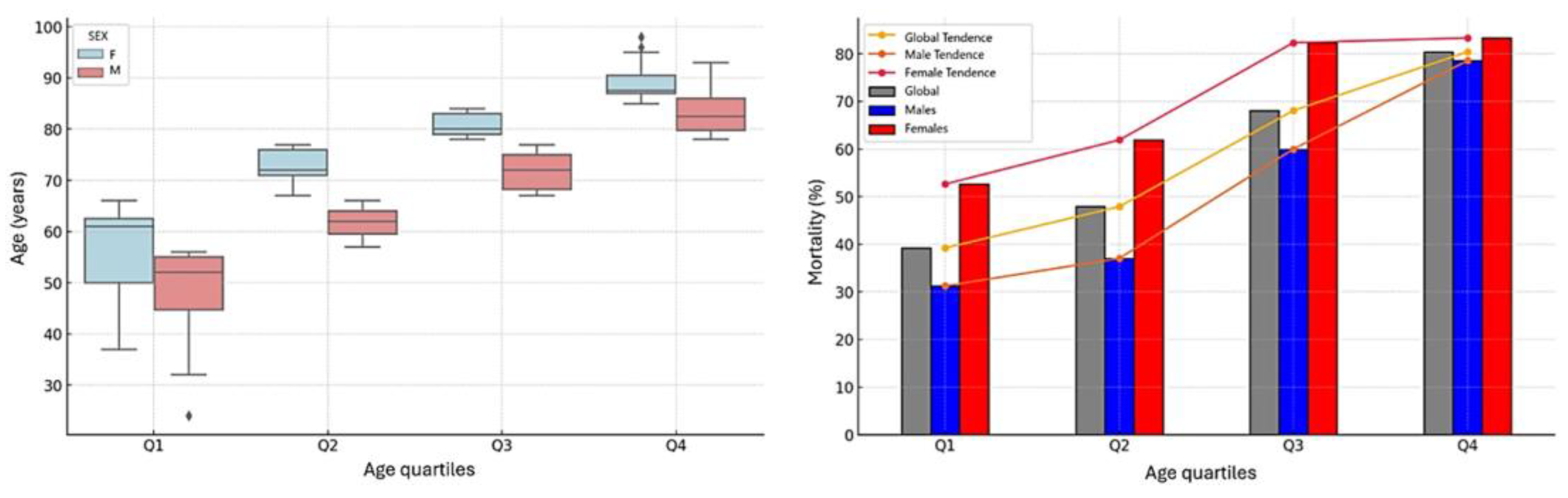

As previously mentioned, age showed a direct association with mortality, with the effect being more pronounced in the upper quartiles. When stratifying each age quartile by gender, women consistently demonstrated a higher mean age compared to men (ANOVA p<0.05, with significant differences confirmed by Tukey post hoc analysis). This finding suggests that the observed protective effect of male gender is likely attributable to differences in age distribution between the groups, rather than an intrinsic protective role of sex. These results are illustrated in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

Our findings align with studies and registries conducted in the United States and Europe. For instance, the ADHERE registry reported a 12-month mortality rate of 36%, compared to the lower but still significant rate observed in our cohort [

13,

14]. In Latin America, mortality rates show considerable variability: Venezuela reported a 3-month mortality of 22.7% [

15], Argentina observed an 18% 30-day mortality due to combined causes [

16], and Brazil documented a one-year mortality of 28.9% [

17]. The scarcity of specific data on AHF in other Latin American countries underscores the heterogeneity in regional evidence and the need for more robust datasets.

Key predictors of mortality, including NT-ProBNP levels, advanced age, atrial fibrillation/flutter, and chronic kidney disease, were consistent with previous studies. Elevated NT-ProBNP levels (>5582 pg/mL) have been associated with a higher risk of death (HR 1.6) [

18], as have age ≥80 years (HR 1.61), dementia (HR 1.08), and atrial fibrillation (HR 1.71) [

10]. Similarly, hyponatremia and elevated plasma creatinine were linked to increased mortality, while lower NT-ProBNP levels were protective.

Health insurance (public vs. private) did not significantly influence 12- or 60-month mortality in our cohort. While patients with public insurance were, on average, older by eight years, no notable differences in comorbidities or disease severity were found. This contrasts with Japanese studies showing public insurance as an independent risk factor for mortality (HR 2.15) [

20]. A systematic review by Enard similarly reported mixed results, highlighting the influence of geographic and population contexts [

21]. In Chile, health insurance appears unrelated to long-term AHF outcomes.

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced challenges in AHF management, with reported doubling of 30-day mortality and reduced hospitalizations, likely contributing to higher in-hospital mortality [

22]. These changes emphasize the need for adaptive strategies in acute care.

Regarding prognostic tools, the APACHE II score is widely used in intensive care units but shows variable correlations with outcomes in critically ill cardiology patients. While models like APACHE-HF address cardiogenic shock, no scoring systems specifically tailored to AHF exist [

23]. In our study, APACHE II was used solely for classification and characterization, showing no significant association with mortality.

Treatment guidelines emphasize early diuretic response, with the European Society of Cardiology recommending 3 to 5 liters of diuresis within 24 hours [

24]. Poor diuretic response correlates with higher 180-day mortality (HR 1.24) [

25], and rapid response has been linked to reduced 30-day mortality [

26]. However, the relationship between intravenous diuretic doses and mortality remains unclear. Sub-analyses from ADHERE suggested that higher diuretic doses increase in-hospital mortality, while greater diuresis improves symptoms and reduces rehospitalization, as shown in the ROSE-AHF study [

27,

28]. Our findings indicate that higher diuretic doses were associated with increased mortality, whereas higher diuresis was protective. This highlights the complexity of diuretic response, warranting alternative definitions based on furosemide mg/kg and achieved diuresis.

5. Conclusions

AHF presents a significant and high mortality rate one year after discharge in Chile. Mortality was associated with age, NT-ProBNP levels, plasma sodium and creatinine at admission, as well as a history of CKD and AF/FLA. Additionally, the average dose of furosemide administered and diuresis during the first 24 hours were significantly related to outcomes. Notably, health insurance type (public or private) was not associated with mortality.

This study highlights key factors linked to mortality in AHF at a center in Santiago, Chile, providing valuable insights into their relative contributions. Furthermore, it enabled the development of predictive models that may improve patient stratification upon admission.

It is important to acknowledge that the study included a relatively small number of patients, which might limit how well these results apply to larger populations or different healthcare settings. Despite this, the findings provide valuable information and are consistent with international studies, which adds confidence to their relevance.

Prospective studies are needed to address potential biases and incorporate contemporary cardiological variables of interest, such as urinary sodium, quantitative LVEF, additional biomarkers, and social determinants of health. Such research is essential to develop strategies for optimizing inpatient and outpatient care for AHF patients6. Patents

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital of the University of Chile, under Resolution Number 59, issued during the session held on October 8, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

This was a retrospective study with anonymized data, conducted under a confidentiality agreement and in compliance with Chilean legislation on human research, so informed consent was not required. Nonetheless, all collected data were handled with the highest level of confidentiality, without recording any personal identifiers.

Data Availability Statement

Chilean legislation stipulates that patient information collected exclusively for research purposes cannot be shared. Additionally, the Ethics Committee only authorized access to this information for research objectives. Therefore, the authors are unable to share the data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to the Cardiovascular Research Unit for their unwavering support, as well as to the staff of the Intensive Cardiac Care Unit and the Cardiovascular Center for their invaluable contributions. Our thanks also go to the medical students and fellows who participated in this study and showed a keen interest in expanding their knowledge of cardiology, epidemiology, and clinical research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic P, Rosano GMC, Coats AJS. Global burden of heart failure : a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology . Cardiovasc Res. 2023 Jan 18;118(17):3272–87. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid CM, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure : a report of Heart Failure Society of America , Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology , Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition Heart Failure : Endorsed by Canadian Heart Failure Society , Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand , and Chinese Heart Failure Association . Eur J Heart Fail . 2021 Mar;23(3):352–80. [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen A, Rutten FH, Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart failure . Eur J Heart Fail . 2020 Aug;22(8):1342–56. [CrossRef]

- Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Crespillo AP, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence : a population-based study of 4 million individuals . The Lancet. 2018 Feb ;391(10120):572–80.

- Lesyuk W, Kriza C, Kolominsky -Rabas P. Cost-of-illness studies in heart failure : a systematic review 2004–2016. BMC Cardiovasc Disord . 2018 Dec;18(1):74. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Toro F, Nazzal N. C, Verdejo PH Incidence and in-hospital mortality due to heart failure in Chile: Are there differences by sex? Rev Médica Chile. 2017;145(6):703–9.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure . Eur Heart J. 2021 Sep 21;42(36):3599–726.

- Crespo- Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, Coats AJ, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long- Term Registry ( ESC -HF-LT ): 1-year follow -up outcomes and differences across regions . Eur J Heart Fail . 2016 Jun ;18(6):613–25. [CrossRef]

- Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for Heart Failure : Predict or Prevent ? Circulation . 2012 Jul 24;126(4):501–6. [CrossRef]

- Marques I, Mendonça D, Teixeira L. One-year rehospitalization and mortality after acute heart failure hospitalisation : a competing risk analysis . Open Heart. 2023 Mar;10(1 ):e 002167.

- Bozkurt B, Nair AP, Misra A, Scott CZ, Mahar JH, Fedson S. Neprilysin Inhibitors in Heart Failure . JACC Basic Transl Sci . 2023 Jan;8(1):88–105.

- Park J, Hwang IC, Yoon YE, Park JB, Park JH, Cho GY. Predicting Long - Term Mortality in Patients With Acute Heart Failure by Using Machine Learning . J Card Fail . 2022 Jul ;28(7):1078–87. [CrossRef]

- Farmakis D, Parissis J, Lekakis J, Filippatos G. Acute Heart Failure : Epidemiology , Risk Factors , and Prevention . Rev Esp Cardiol Engl Ed. 2015 Mar;68(3):245–8. [CrossRef]

- Fonarow GC, ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee . The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure . Rev Cardiovasc Med . 2003;4 Suppl 7:S 21-30.

- Fuenmayor, Vladimir E al. Acute heart failure: evaluation of mortality after hospital discharge. Med Interna Caracas. 2018;34(3):161–71.

- Lescano A, Soracio G, Soricetti J, Arakaki D, Coronel L, Cáceres L, et al. Argentina Registry of Acute Heart Failure (ARGEN-IC). Evaluation of a Partial Cohort at 30 Days . Rev Argent Cardiol . 2020 Apr;88(2):118–24.

- Albuquerque DC, Barros E Silva PG, Lopes RD, Hoffmann C, Nogueira PR, Reis H, et al. Main results of the first Brazilian Registry of Heart Failure (BREATHE). Eur Heart J. 2022 Oct 3;43(Supplement_2 ):ehac 544.1078. [CrossRef]

- Yin T, Shi S, Zhu X, Cheang I, Lu X, Gao R, et al. Survival Prediction for Acute Heart Failure Patients via Web- Based Dynamic Nomogram with Internal Validation : A Prospective Cohort Study . J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:1953 –67. [CrossRef]

- Sarastri Y, Zebua JI, Lubis PN, Zahra F, Lubis AC. Admission hyponatraemia as heart failure predictor events in patients with acute heart failure . ESC Heart Fail . 2023 Oct ;10(5):2966–72. [CrossRef]

- Fujito H, Kitano D, Saito Y, Toyama K, Fukamachi D, Aizawa Y, et al. Association between the health insurance status and clinical outcomes among patients with acute heart failure in Japan . Heart Vessels . 2022 Jan;37(1):83–90. [CrossRef]

- Enard KR, Coleman AM, Yakubu RA, Butcher BC, Tao D, Hauptman PJ. influence of Social Determinants of Health on Heart Failure Outcomes : A Systematic Review . J Am Heart Assoc . 2023 Feb 7;12(3 ):e 026590. [CrossRef]

- Kubica J, Ostrowska M, Stolarek W, Kasprzak M, Grzelakowska K, Kryś J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on acute heart failure admissions and mortality : a multicentre study (COV-HF-SIRIO 6 study ). ESC Heart Fail . 2022 Feb ;9(1):721–8. [CrossRef]

- Okazaki H, Shirakabe A, Hata N, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi N, Shinada T, et al. New scoring system (APACHE-HF) for predicting adverse outcomes in patients with acute heart failure : Evaluation of the APACHE II and Modified APACHE II scoring systems . J Cardiol . 2014 Dec;64(6):441–9. [CrossRef]

- Correction to : 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure : Developed by the task force for diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the special contribution of Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2024 Jan 1;45(1):53–53.

- Ter Maaten JM, Valente MAE, Damman K, Hillege HL, Navis G, Voors AA. Diuretic response in acute heart failure — pathophysiology , evaluation , and therapy . Nat Rev Cardiol . 2015 Mar;12(3):184–92. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio Rodrigues T, Garcia Quarto LJ, Nogueira SC, Theuerle JD, Farouque O, Burrell LM, et al. Door-to-diuretic time and mortality in patients with acute heart failure : A systematic review and meta- analysis . Am Heart J. 2024 Mar;269:205 –9. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz MB, Gayat E, Salem R, Lassus J, Nikolaou M, Laribi S, et al. Impact of diuretic dosing on mortality in acute heart failure using a propensity-matched analysis . Eur J Heart Fail . 2011 Nov ;13(11):1244–52. [CrossRef]

- Chen HH, Anstrom KJ, Givertz MM, Stevenson LW, Semigran MJ, Goldsmith SR, et al. Low- Dose Dopamine or Low- Dose Nesiritide in Acute Heart Failure With Renal Dysfunction : The ROSE Acute Heart Failure Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2013 Dec 18;310(23):2533. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).