1. Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a pervasive and complex chronic syndrome impacting individuals worldwide. As reported by the American Heart Association, the prevalence of CHF among Americans aged 20 and older was approximately 6 million between 2013 and 2016. Notably, there was a significant increase of 5.7 million cases between 2009 and 2012, with a projected further increase of 46% from 2012 to 2030, reaching over 8 million individuals over 18 years old. This increase indicates that the incidence of CHF is expected to rise from 2.42% in 2012 to 2.97% in 2030 [

1]. The European Society of Cardiology also notes that in developed countries, the incidence of CHF is estimated at 1-2% among adults but rises to nearly 10% among those aged over 70. Additionally, the hazard of CHF is 33% for men at the age of 55 and 28% for women [

2]. In Greece, it is believed that about 200,000 patients have CHF, with around 30,000 new diagnoses reported every year [

3]. `

Individuals with CHF often experience poor clinical outcomes, resulting in frequent hospitalizations. In Greece, the hospitalization rate is estimated at 19%, with an annual mortality rate of 8% during one year of follow-up. However, patients with a history of previous CHF-related hospitalizations exhibit higher hospitalization and mortality rates, at 42% and 24%, respectively [

4]. The high rate of hospitalization is related to an important rise in the total healthcare cost. Regarding Greece, Parisis et al. (2015) found that hospitalization for CHF accounts for 75% of the total cost related to CHF, amounting to approximately €2,300 to €3,200 per hospitalization. In 2012, the estimated worldwide cost of CHF was

$533 million (approximately €416 million) [

6]. However, the direct cost of CHF exceeds €4,400 per person annually in Greece [

4].

It is essential to highlight that a significant portion of hospitalizations and costs associated with CHF are preventable and can be avoided, primarily attributed to low adherence to the recommended therapeutic regimen. The low level of medication adherence is associated with an increased symptom manifestation. Also, patients often visit a hospital because they are not able to face any changes in the signs and symptoms of their chronic disease. These imply that patients often choose not to follow the healthcare professionals' prescribed instructions and fail to adopt the suggested self-care behaviors necessary for effective condition management [

4,

5].

In 2003, the European Society of Cardiology defined self-care as "the decision and strategies undertaken by the individual to maintain life, healthy functioning, and well-being." Self-care behavior can be health-deviated, or developmental, depending on whether it is needed by every person, emerges from health issues, or is associated with a particular life period [

7]. In 2021, the European Society of Cardiology emphasized the significance of effective patient self-care in managing heart failure, leading to better quality of life, decreased readmission rates, and lower mortality rates [

8,

9].

However, the literature review reveals a lack of instruments and tools for assessing self-care behaviors among CHF patients, which are crucial for healthcare professionals to develop and implement strategies for improvement. For instance, the Self-Care Assessment Schedule (SCAS) was developed by Burnes and Benjamin and assesses ten self-care behaviors during a 14-day-period of time, however, it is not a disease-specific tool for CHF [

10]. The Self-Care Behavior Questionnaire was developed by Dodd in 1984 to estimate self-care among patients with cancer who face side effects of chemotherapy [

11]. The Self-Care in Chronic Illness Questionnaire includes 45 items and it is not a disease-specific questionnaire for CHF [

12].

On the other hand, we found some tools assessing self-care among patients with CHF, however they are characterized by some limitations. First of all, the Beliefs about Medication and Compliance Scale and the Beliefs about Dietary Compliance Scale were developed by Bennett et al. [

13]. Both these two scales aim to assess patients' beliefs about the benefits of and barriers to medication and diet adherence in patients with CHF. The Selfcare of Heart Failure Index is a disease-specific instrument that evaluates self-care behaviors in CHF [

14]. It includes 15 items sub-divided into 3 scales. More specifically, the Self-care of Heart Failure Index assesses self-care maintenance, self-care management, and self-care self-confidence. The self-care maintenance concerns symptom monitoring and treatment adherence so that patients could be able to adopt a healthy lifestyle. Self-care management is a dynamic, intentional decision-making approach initiated in answer to symptoms. Self-care management is based on symptom recognition, symptom, and treatment evaluation which is related to self-efficacy. In other words, patients should be able to recognize any change in signs and symptoms of CHF and to respond immediately. Finally, the scale assesses self-care maintenance based on CHF clinical guidelines regarding diet, body weight, exercise, and flu vaccination, whereas the questions related to self-care management are about signs and symptoms of CHF.

The last disease-specific tool for CHF is the Revised European Heart Failure Self-care Behavior Scale which was published in 2003 and has been translated into many languages [

15]. The scale includes 12 items and assesses self-care behavior in patients with heart failure over time. More specifically, the items negotiate patients´ self-care regarding body weight, symptom management, flu vaccination, exercise, diet, and medication adherence. However, according to the analysis, three items were excluded from the scale which are very significant issues in patients with heart failure. These items refer to ¨taking rest if dyspnea occurs ¨, ¨flu shot¨, and ¨medication adherence¨.

The recognition of symptoms and signs of heart failure and the knowledge of their management are essential issues in the management of heart failure. Healthcare providers educated patients and their families about the symptoms of heart failure like dyspnea, fatigue, and edema, and how to manage them. Therefore, it is important a scale to assess how patients face the symptoms of their health condition since the ineffective management of their symptoms leads to a deterioration of their quality of life. Also, healthcare workers should be able to identify any possible gaps in the knowledge of their patients to provide them with appropriate education. Moreover, the flu vaccination is an important part of the management of CHF, since patients with heart failure are at high risk when they are contracted with influenza. However, the researchers excluded this item because of its psychometric properties. The last deleted item is related to medication adherence. Medication adherence plays a significant role in the management of all chronic diseases like heart failure and it is an integral part of self-care. From all the above, it is obvious that the Revised European Heart Failure Self-care Behavior Scale does not include important aspects of the self-care behavior of patients with heart failure.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to develop and test the Hippocratic Heart-Failure Self-Care Scale. Specifically, the prevailing study goals at:

Develop the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale.

Assess the reliability of the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale.

Investigate the factorial structure of the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale.

Evaluate the structural estimation modeling approach of the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale using explanatory factor analysis (EFA).

2. Materials and Methods

Establishment of the face and content validity of the Hippocratic Heart-Failure Self-Care Scale.

The development of the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale involved a comprehensive literature review of recent data and reports from health associations such as the European Society of Cardiology [

8,

9]. A 30-item scale was created, comprising 8 sub-sections: medication aspects (items 1-6), diet aspects (items 7-15), exercise aspect (items 16-17), alcohol aspects (items 18-19), smoking topic (items 20-22), symptoms (items 23-26), appointment keeping (items 27-28), and vaccination aspects (items 29-30). Each item was presented as a full sentence and rated on a five-point Likert scale from "never" (0 points) to "very frequently" (4 points), resulting in an entire score range of 0 to 120.

To assess content validity, the opinions of seven experts, including cardiologists, heart failure specialized nurses, statistics experts, and psychometrics experts, were solicited through an evaluation form. The task force categorized each item as "essential," "useful but inadequate," or "unnecessary." Their feedback was incorporated into the scale, leading to the exclusion of 8 items due to overlap between sub-sections. The clarity of all items was also evaluated and refined with input from 50 non-CHF individuals without research backgrounds.

Ultimately, the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale was reduced to a 22-item scale with 8 sub-sections.

Table 1 presents the total scale. Items 1-4, 6-8, 11, 13-16, and 19-22 were reverse-scored. Points over 52 were classified as "very good," 48-51 as "good," 43-47 as "fair," and below 42 as "poor" based on score quartiles. Therefore, a higher score indicates better self-care behavior among patients with heart failure.

Sample and Data Collection

The present research was carried out at a General Hospital in Athens from June 2020 to March 2021. Totally 250 men and women were hospitalized in the Cardiology Unit due to either deteriorating health conditions or scheduled procedures. The sample size was calculated so that the question item/ participant ratio would be at least 1/10 [

16]. Inclusion criteria included being at least 18 years old, exhibiting symptoms of CHF NYHA II-IV, having a confirmed CHF diagnosis based on ultrasound (HFrEF), the ability to read and write Greek, having written informed consent received, the absence of life-threatening diseases other than CHF, the absence of psychiatric disorders, no cardiac surgery within the last 6 months, and no musculoskeletal disorders affecting physical activity.

Data collection involved face-to-face interviews during the initial assessment, with a follow-up phone call to 30 participants one month later to assess test-retest reliability. This time frame is considered a rational concession between recollection bias and any changes in the patient's health status since a very short time interval may affect the patient´s responses due to memory or mood. Findings above of 0.9 are considered as excellent reliability, 0.8 to 0.9 as good reliability, 0.7 to 0.8 as acceptable reliability, and 0.6 to 0.7 as questionable reliability [

17].

Participants completed the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale, and their demographic characteristics, including age, sex, level of education, and occupational and marital status, were collected. The scale was well-received, with participants reporting that it was clear, relevant, and easy to complete within 5-10 minutes.

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and ethical approval was obtained by the Ethical Committee. The study was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed.

Statistics

The mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range were used to describe the quantitative data, whereas percentage (%) and frequencies (N) were used for qualitative variables. Reliability coefficients measured by Cronbach’s alpha were calculated for the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale to assess the reproducibility and consistency of the instrument. A Cronbach coefficient alpha value of >0.59 and <0.95 was considered acceptable [18-19]. The underlying dimensions of the scale were checked with an explanatory factor analysis using a Varimax rotation and the Principal Components Method as a usual descriptive method for analyzing grouped data. A factor analysis, using principal component analysis with Varimax rotation, was carried out to determine the dimensional structure of the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale using the following criteria: (a) eigenvalue>1; (b) variables should load >0.50 on only one factor and less than 0.40 on other factors; (c) the interpretation of the factor structure should be meaningful, and (d) the scree plot is accurate if the means of commonalities are above 0.60. A Bartlett’s test of sphericity with p<0.05 and a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy of 0.6 was used in performing this factor analysis. A factor was considered important if its eigenvalue exceeded 1.0 [

20].

A correlation analysis was used to assess internal consistency reliability. The correlation coefficient must not be negative or below 0.20. Qualitative and quantitative steps on attitude scale development Pearson’s rank correlation coefficient was used to measure the level of agreement between responses at test and re-test. In addition, a linear regression model with the level of adherence as the dependent variable and one independent variable (such as socioeconomic factors, and the relationship between patient-healthcare providers) was used to assess the relationship between the level of adherence and the added independent variable. The level of significance was 0.05. The analysis was conducted via SPSS 22.0.

3. Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the sample indicated that 52.8% were women (mean age = 70 years). Most of the participants were divorced or widowed (85.6%), 43.6% had a higher educational level, and 26.0% were employed. Over half of the patients had NYHA III CHF. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (25.2%) and respiratory disease (16.8), with coronary artery disease as the primary cause of CHF (

Table 3).

The Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale demonstrated sufficient reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.906 for the whole scale (Items 1-22). Subgroup analyses also indicated reliability for men (0.79), women (0.82), NYHA II (0.73), NYHA III (0.85), and NYHA IV (0.80).

The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.658 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 1971.02, df = 142, p < 0.001. Factor analysis identified two primary factors: "Medication Aspects" and "Diet Aspects," which explained 88.44% of the entire variance, as presented in

Table 4. The first one encompassed items related to medication: 1 (forget to take medication), 2 (omit to take medication due to its side effects), 3 (omit to take medication when patients feel better), 4 (omit to take medication when patients are outside/travel), and 17 (change the doses according to recommendations); this was termed “Medication aspects”. The second factor includes the following items: 5 (daily consumption of fruit and vegetables), 6 (consumption of food responsible for weight increase), 7 (consumption of salty food), 8 (shake salt on your food), 9 (read food labels for ingredients) and 10 (adaption of liquid consumption); this was termed “Diet aspects”. Cronbach's alpha was 0.702 for "Medication Aspects" and 0.251 for "Diet Aspects."

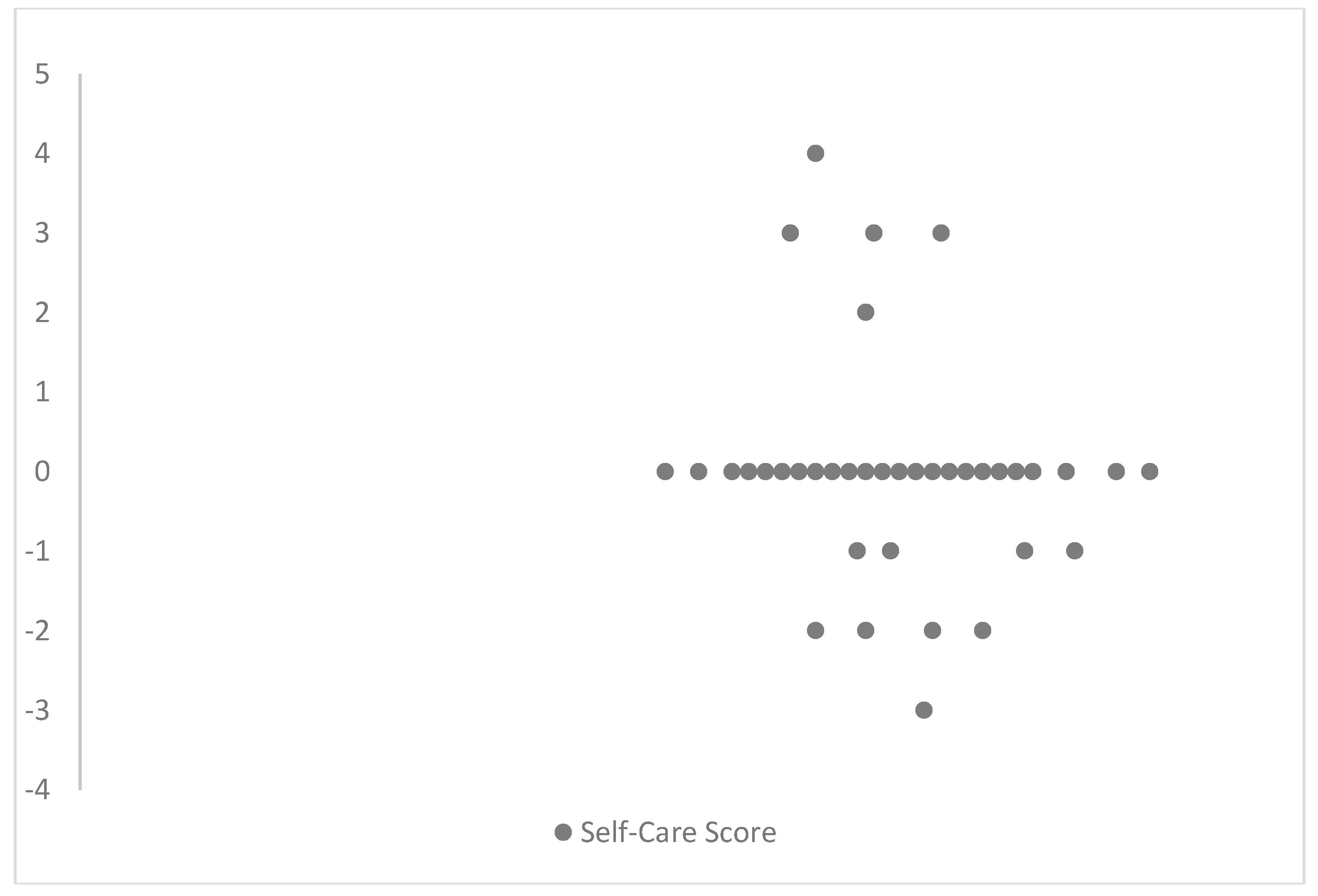

The Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale exhibited strong stability over time, with a high positive correlation (r=0.973, p<0.001) in the test-retest reliability assessment. Bland & Altman Method Scatter Plot and the Cohen Kappa statistic further demonstrated strong inter-rater reliability and agreement between measurements (

Figure 1).

The Hippocratic heart failure self-care scale was well-shouldered by the individuals since it was not difficult and requested less than 10 min to be answered. The items were assessed as pertinent, sensible, and plain. On account of that face validity was considered very good. The test–retest analysis indicates a high positive correlation between the total scores of the assessments (r = 0.983; p < 0.001). The total score on the Hippocratic heart failure self-care scale was significantly lower among patients with NYHA IV (t = 2.298; p = 0.026). In addition, the scores for the medication and diet sub-scale were significantly higher among participants with NYHA IV (p > 0.05). According to correlation analysis, the level of self-care was not related to age (r = −0.761; p > 0.05), gender (t = 0.317; p > 0.05), and education level (p > 0.05). However, the total score on the Hippocratic heart failure self-care scale is associated with the presence of comorbidities. For instance, the level of self-care was lower among patients with diabetes mellitus, and respiratory or kidney disease than other patients without comorbidities (p<0.01). The main differences were observed in the sub-scales of medication and symptoms.

4. Discussion

The Hippocratic heart failure self-care scale is a disease-specific tool for assessing the level of self-care in patients with CHF. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.906 for the entire scale based on validation analysis, whereas the factor analysis detected two main factors. Further analysis did not show a satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha for these two factors. These domains accounted for 88.44% of the total variance.

This study marks the first attempt to develop a comprehensive tool for evaluating self-care behaviors in patients with heart failure, which holds significant potential for integration into both research and clinical practice. For instance, the Self-Care Assessment Schedule (SCAS), Self-Care Behavior Questionnaire, and Self-Care in Chronic Illness Questionnaire are non-disease-specific questionnaires assessing some aspects of self-care among patients with chronic health diseases [

9,

10,

11]. The Beliefs About Medication Compliance Scale and the Beliefs About Dietary Compliance Scale are two disease-specific tools assessing only the self-care behavior regarding medicines and diet among patients with CHF [

12]. The Selfcare of Heart Failure Index estimates self-care behaviors like medications, diet, and symptom management, whereas the Revised European Heart Failure Self-care Behavior Scale does not consider the recognition of signs and symptoms of deterioration of heart failure and immunization [

14].

The validation study indicated very good internal consistency for the entire scale, although sub-scales related to "Diet," "Alcohol," "Appointment Keeping," and "Vaccination Aspects" exhibited low Cronbach's alpha values. "Smoking" and "Exercise" sub-scales each had only one question, precluding the calculation of Cronbach's alpha. "Symptoms" and "Medications" sub-scales had Cronbach's alpha values of 0.506 and 0.702, respectively. Therefore, the scale is suggested to be used as an entire tool.

Factor analysis identified two factors, "Medication Aspects" and "Diet Aspects," which may provide valuable insights into self-behaviors among CHF patients. The scale offers healthcare providers the ability to categorize patient adherence into "very good," "good," "fair," and "poor" levels based on score quartiles, facilitating targeted interventions.

Test-retest reliability results suggest that the Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale is stable over time, indicating its potential for long-term monitoring and assessment of patient self-behaviors. This is further supported by the strong agreement between measurements observed in the Bland & Altman Method Scatter Plot and the Cohen Kappa statistic.

The Hippocratic heart-failure self-care scale offers a valuable tool for clinical practice, enabling healthcare providers to identify patients who may benefit from interventions aimed at improving their self-behaviors. Future research should involve cross-sectional and cohort studies to educate clinical practitioners and guide interventions for self-care behaviors in CHF patients.

5. Conclusions

The Hippocratic heart failure self-care scale had satisfactory reliability, and the factor analysis indicated two main factors that were of interest. Therefore, we can state that it is a reliable and valid scale for assessing self-care behaviors in people with heart failure. The score of the scale is independent of the demographic characteristics of patients with heart failure; therefore, it could be used for any patient with heart failure without any limitation. Healthcare providers can use it in their clinical practice to enhance the identification of patients who do not follow and adopt the recommended self-care behaviors. Future studies are recommended to inform clinical practicians and guide the development of specific interventions for self-care behaviors in patients with CHF.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B.; methodology, H.B. and A.A.C.; software, A.A.C. and N.V.F.; validation, K.G. and A.A.C.; formal analysis, A.A.C.; investigation, H.B., A.A.C. and N.V.F.; data curation, A.P. and A.A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G., N.V.F., A.A.C. and H.B.; writing—review and editing, K.G. and A.A.C.; supervision, H.B.; project administration, H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of General Hospital of Athens “Hippokration” (Ethical Committee’s approval No.: 52/21-12-2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141(9), e139–e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC [published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2016; 37, 27, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Trikas, A. Heart failure. Heart Diseases. Athens: Paschalidis Medical Publications. P: Athens, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stafylas, P.; Farmakis, D.; Kourlaba, G.; Giamouzis, G.; Tsarouhas, K.; Maniadakis, N.; et al. The heart failure pandemic: The clinical and economic burden in Greece. Int J Cardiol. 2017, 227, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parissis, J.; Athanasakis, K.; Farmakis, D.; Boubouchairopoulou, N.; Mareti, C.; Bistola, V.; et al. Determinants of the direct cost of heart failure hospitalization in a public tertiary hospital. Int J Cardiol. 2015, 180, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.; Cole, G.; Asaria, P.; Jabbour, R.; Francis, D.P. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014, 171(3), 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainscak, M.; Blue, L.; Clark, A.L.; Dahlström, U.; Dickstein, K.; Ekman, I.; et al. Self-care management of heart failure: practical recommendations from the Patient Care Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011, 13(2), 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure Eur Heart J. 2021; 42, 36, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar]

- European Society of Cardiology, 2016. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J.

- Connelly, C.E. An empirical study of a model in self-care in chronic illness. Clin Nurs Spec 1993, 7, 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, S.J.; Perkins, S.M.; Lane, K.A.; Forthofer, M.A.; Brater, D.C.; Murray, M.D. Reliability and validity of the compliance belief scales among patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001, 30(3), 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart Failure Society Of America. Executive summary: HFSA 2006 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Card Fail. 2006, 12(1), 10–38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijó, M.K.; Ávila, C.W.; de Souza, E.N.; Jaarsma, T.; Rabelo, E.R. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the European Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior Scale for Brazilian Portuguese. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012, 20(5), 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Barbaranelli, C.; Carlson, B.; Sethares, K.A.; Daus, M.; Moser, D.K.; Miller, J.; Osokpo, O.H.; Lee, S.; Brown, S.; Vellone, E. Psychometric Testing of the Revised Self-Care of Heart Failure Index. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019, 34(2), 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, B.; Lupón, J.; Parajón, T.; Urrutia, A.; Herreros, J.; Valle, V. Aplicación de la escala europea de autocuidado en insuficiencia cardíaca (EHFScBS) en una unidad de insuficiencia cardíaca en España [Use of the European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS) in a heart failure unit in Spain]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006, 59(2), 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P. Validity and reliability of questionnaires in epidemiological studies. Arch of Hellen Med. 2013, 30, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- RICKHAMPPHUMANEXPERIMENTATIONCODEOFETHICSOFTHEWORLDMEDICALASSOCIATIONDECLARATIONOFHELSINKI Br Med J. 1964; 2, 5402, 177.

- Powers, B.; Knapp, T. Dictionary of nursing theory and research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, J.; Wood, J. Advanced Design in Nursing Research. 2nd ed. California: Sage Publication; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cam, M.O.; Arabaci, L.B. Qualitative and quantitative steps on attitude scale. Turkish J Res Dev Nurs. 2010, 2, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).