1. Introduction

Interoperability between digital models is one of the most critical challenges in both AEC and industrial worlds. In their respective fields of application, the manufacturing and construction sectors adopt well-established standards for the representation of three-dimensional and information models: the STandard for the Exchange of Product data (STEP) format (ISO 10303-21 [

1]) for manufacturing and the Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) format (ISO 16739-1 [

2]) for construction. However, although both standards are based on explicit and formally defined data structures, communication between these two worlds remains complex due to substantial differences in conceptual models, levels of detail and application purposes. This area is still little explored in scientific literature, and there are few commercial solutions currently available, often for a fee and generally integrated within proprietary software ecosystems.

This integration difficulty is particularly evident in complex construction projects, where mechanical components of industrial origin, such as plant, machinery or prefabricated systems, need to be included in the Building Information Model (BIM) model. In the absence of standardized and accessible tools for efficient conversion of STEP models to IFC-SPF (STEP Physical File), transposition of information is frequently done by manual remodeling of components. This approach is highly time-consuming and subject to a high risk of introducing errors. Currently available integration solutions, in most cases, are limited to importing geometries in the form of meshes into the BIM model as external coordination files and thus lacking semantic structure. Even in cases where meshes are incorporated within the IFC file, they are generally associated with generic entities such as IfcBuildingElementProxy, resulting in the loss of key semantic information. In addition, the geometric complexity of the generated meshes results in a significant increase in computational load and a reduction in the efficiency of authoring software. The result, therefore, is suboptimal management of industrial components, resulting in an uncontrolled process that causes loss of relevant information and transfer of overly detailed content relative to actual civil design needs.

This paper proposes an operational framework for the structured transformation of STEP models to IFC-SPF format, with a specific focus on semantic and geometric optimization of the model to ensure its full usability in building and civil design contexts. The approach taken is not limited to formal conversion between two formats, but introduces a logic of data filtering, simplification and enrichment, based on functional and design criteria. Key elements of the framework include selective removal of irrelevant elements (e.g., small parts), simplification of geometries, merging of complex assemblies, and integration of additional properties through external sources.

The importance of the contribution lies in the possibility of bridging the existing gap between manufacturing and civil design by proposing a consistent, lightweight and interoperable information flow between the two domains. Experimental results show a significant reduction in the computational load and size of the IFC files produced, with low processing time and information quality adequate for the purposes of BIM design.

In summary, the work presented demonstrates how a structured approach to STEP-to-IFC conversion, based on real-world design requirements, can be an effective, scalable and interoperability-oriented solution between digital models in industrial and AEC domains. A methodological framework is proposed and one among possible operational solutions is implemented. This implementation is distinguished using open-source tools, selected based on principles of scientific repeatability and transparency. It also adopts a simple and accessible user interface designed to facilitate application in professional settings even by practitioners without programming skills.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background

2.1.1. Interoperability in Manufacturing Domain

During the design phase, the manufacturing industry makes extensive use of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) modelers, often based on proprietary software. The growing need to exchange design data has critically highlighted the problem of interoperability between different systems. In manufacturing, CAD models can be classified into two main categories [

3]:

The use of high-level CAD models is crucial to the Model-Based 3D Engineering approach of fully conveying design information through the three-dimensional model, with the goal of ensuring long-term data maintenance. In this context, the international standard ISO 10303 is a key tool to enable interoperability between different CAD systems, via the neutral data structure STEP [

5]. Within this standard, several Application Protocols (APs) have been defined to meet the specific needs of various industries. The main ones include [

6]:

AP203 - Configuration Controlled Design: designed for the aerospace industry, defines geometries, topologies, and configuration management mechanisms for parts and assemblies

AP214 - Core Data for Automotive Mechanical Design Processes: developed for the automotive industry, extends the functionality of AP203 by including support for color and geometric tolerances

AP242 - Managed Model-Based 3D Engineering: integrates the contents of the previous protocols, providing a unified format for managing 3D model-based engineering. STEP AP242 enables efficient collaboration between design and manufacturing by facilitating the automated exchange of design specifications between different systems and organizations [

7]

In addition to STEP formats, there are additional open formats. The Jupiter Tessellation (JT) format, initially developed by Siemens and later adopted as an ISO 14306 standard [

8] in 2012 [

9], is known for its effectiveness in geometric visualization and support for PMI, making it suitable for use in Model-Based Engineering contexts. However, despite its openness, the adoption of JT outside the Siemens ecosystem remains limited. Another emerging format is QIF (Quality Information Framework), standardized under ISO 23952 [

10]. QIF defines an integrated set of information models that facilitate the exchange of data across the entire quality cycle in manufacturing, from product design to inspection planning and execution to analysis and reporting [

11]. Although QIF represents a very promising solution, its adoption is still in the early stages and, at present, its deployment remains limited. STEP thus emerges as a more widely used format in the manufacturing landscape.

2.1.2. Interoperability in AEC Domain

The construction industry has also been confronted with interoperability issues in the exchange of digital data, particularly in the BIM context. Beginning in 1994, with the development of IFC, the path toward defining an open data model standard capable of meeting the interoperability requirements specific to the BIM context was formally initiated [

12]. Currently, IFC represents the most widely adopted open standard in the industry and corresponds to ISO 16739-1 [

2]. Among the proposed formats, the most used one is IFC STEP Physical File (IFC-SPF) [

13], which, similarly to the STEP format, is formally described through the EXPRESS language, in accordance with ISO 10303-21 standard [

1].

2.1.3. Integration of Manufacturing Domain into AEC Domain

In complex building projects involving a strong mechanical component or the integration of manufacturing products, a dialogue between industrial CAD models and BIM models is necessary. Indeed, it is essential for civil designers to be able to visualize, query and integrate mechanical components within their working environments to properly plan structural elements, plant systems, supporting works, and so on. The not achieved acceptance in the AEC industry of the STEP data model represents a significant barrier to interoperability [

14]. A key contributor to this issue is the presence of inconsistent and incompatible schemas across applications and standards, with divergent definitions of entity-types impeding seamless data exchange [

15]. This limitation affects a broad range of CAD models [

16] and has direct consequences for commercially available software, which often restricts export capabilities to either the STEP or IFC format based on their domain-specific requirements [

17]. Furthermore, it is noted in the literature that software capable of performing STEP to IFC-SPF conversion is often tied to proprietary ecosystems and, in most cases, available only through paid plug-ins. It should be emphasized that by “integration” we do not mean a mere transposition of data between one format and another: in fact, the differences between the conceptual models and modeling logics of the two sectors (manufacturing and AEC) are substantial. In the manufacturing context, modeling is characterized by a high level of detail, including explicit representation of each individual product component (e.g., screws, bolts, flanges, plates, etc...) that is functional for industrial production, but excessive for the construction sector. Such detail introduces a significant computational load, both in terms of geometric and informational complexity. In addition, much of the information conveyed by STEP models, such as geometric tolerances, surface specifications, welding symbols, process notes, or material characteristics, is irrelevant to civil design. Therefore, to ensure effective integration between CAD and BIM models, it is necessary to selectively filter the information to be transferred, considering the actual needs of design and AEC management. Such selection is essential to avoid the propagation of superfluous data that, in addition to reducing the computational efficiency of the software involved, could compromise the readability, maintainability and overall quality of the information model.

2.2. Methodological Framework

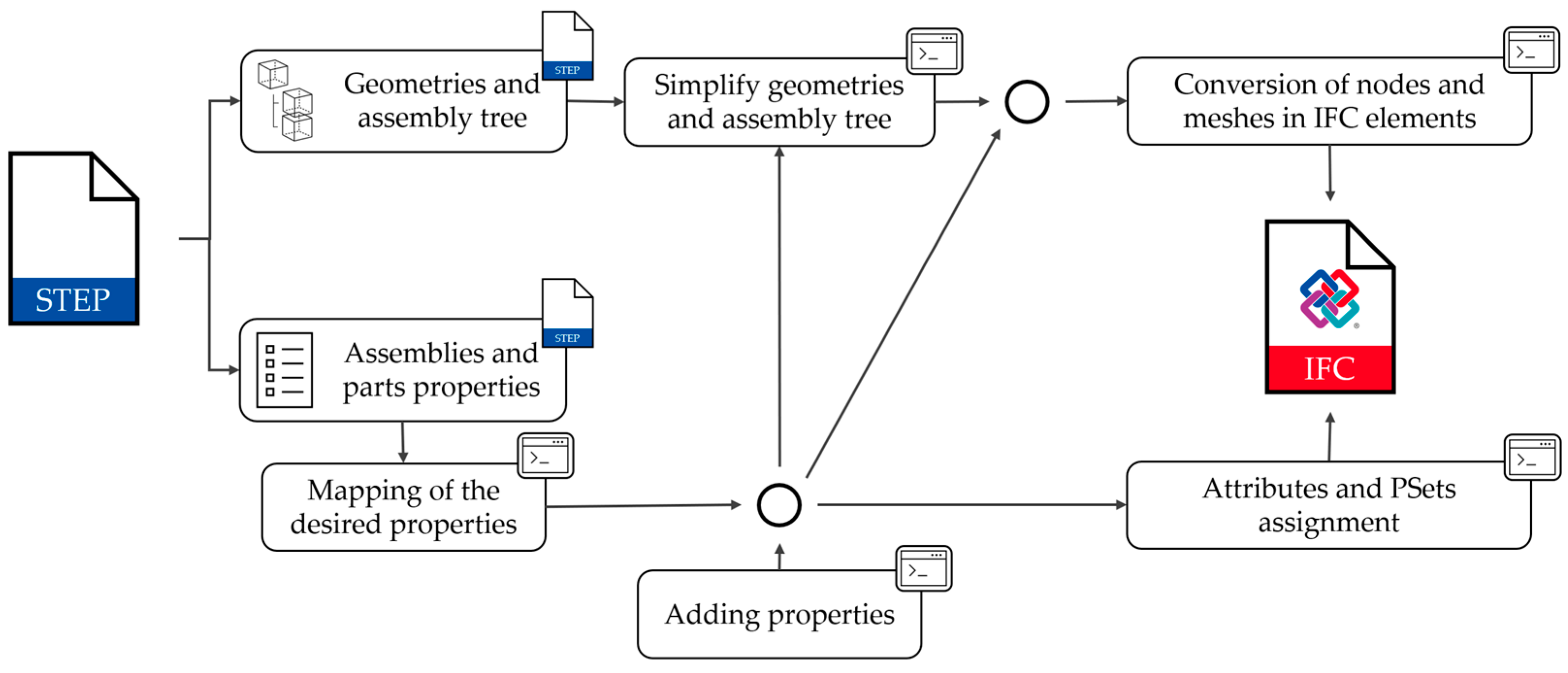

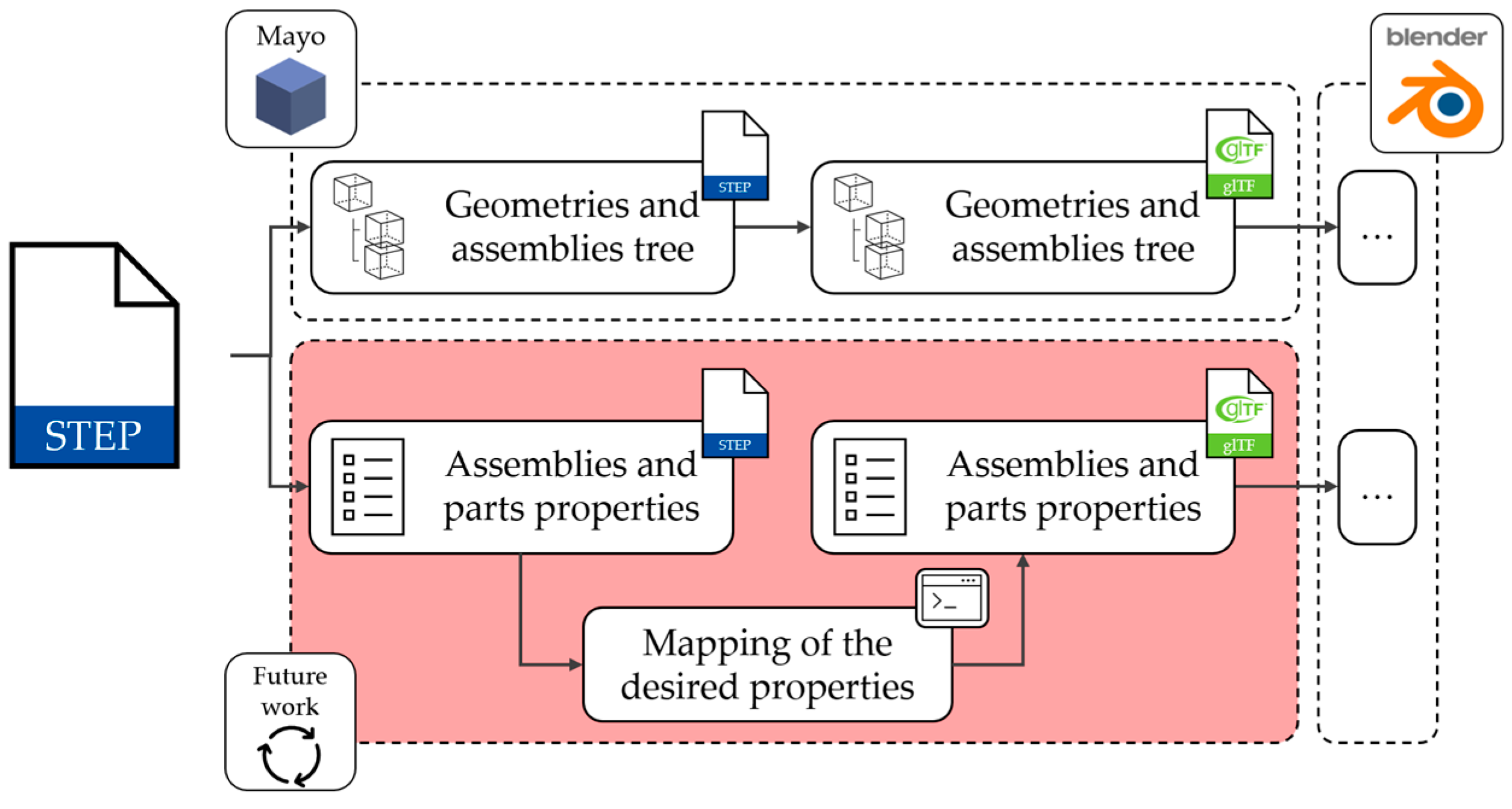

The proposed framework is not limited to simply converting a STEP file to IFC-SPF format but defines a structured procedure for controlling and managing geometric and semantic information, with the goal of generating consistent and fully usable output within civil engineering design software. The workflow is shown in

Figure 1.

From the AEC perspective, the essential information to be extracted from the STEP file concerns geometries, the assembly tree, and the properties associated with parts and assemblies. The properties of parts and assemblies must be properly mapped and transformed into attributes compatible with the IFC data model to ensure an effective semantic transition. In addition, the framework provides the ability to enrich the model with additional properties not originally present in the STEP file. Such additional information can come from external sources such as databases, CSV files or other software. It is necessary to integrate external data because it is difficult for the manufactory domain to produce model with the specific needs of civil design. Integrable properties and information include instructions for geometric simplification and assembly tree simplification. By analyzing the assembly tree, it is possible to identify and exclude elements that are not relevant to the design (e.g., screws, flanges, labels, cables, etc.), thus reducing the overall number of entities to be managed. The framework provides for the merging of assemblies into unitary entities, reducing the number of managed objects, improving efficiency in model management and significantly reducing computational load and file weight. Regarding geometries, an automatic simplification procedure is implemented for overly detailed shapes, to make the model lighter and more usable in civil design software, without compromising the information essential for integration into the AEC context. Finally, the nodes of the assembly tree and the resulting geometries (usually in the form of meshes) are converted into IFC entities, to which the previously processed attributes and properties are associated.

The result is an optimized IFC file, which represents a simplified and semantically coherent version of the original product, specifically tailored to the requirements of design in the AEC sector.

2.2.1. Product Data Management (PDM)

The collection, organization, and management of product information are commonly referred to as Product Data Management (PDM. Within the STEP context, PDM is supported by the STEP PDM Schema, a subset of STEP entities designed to represent typical PDM concepts and structures. The entity-relationship model that underpins the STEP standard is sufficiently generic and flexible to accurately represent properties of any product type, regardless of the application domain [

18]. Furthermore, there are some dictionaries of proprieties like ISO 13584 (PLIB) [

19] that establish standardized EXPRESS-based information model for product classification libraries, enabling interoperability and reuse of shared concepts across domains [

20].

The aim of this chapter is not to provide an exhaustive analysis of the STEP data structure nor an in-depth discussion of the attribution of properties, but rather to provide some basic operational indications on the insertion of properties within a STEP file, to support the implementation of the framework described in this study. The complete definition of the entities included in the STEP schema can be found in [

21], while a series of exemplary diagrams of the EXPRESS schema is available in [

22]. As software for the visualization and analysis of the properties, PMIs and all the data contained within STEP, [

23] was used.

In the STEP standard, the concept of product is represented by a generic entity that can describe either a single part or an assembly. The concept of product could be a hierarchical structure where product’s assemblies and parts occupy subsequent levels [

24]. An assembly is a type of product composed of one or more parts or other nested assemblies and parts are the basic components used to construct assemblies. So, the elementary unit of the STEP model is represented by the part. A property is the definition of a special quality and can reflect physical or arbitrary measures, defined by the user. In the PDM schema, a general model is used for the instantiation of property information. The information reported below is a reworking from [

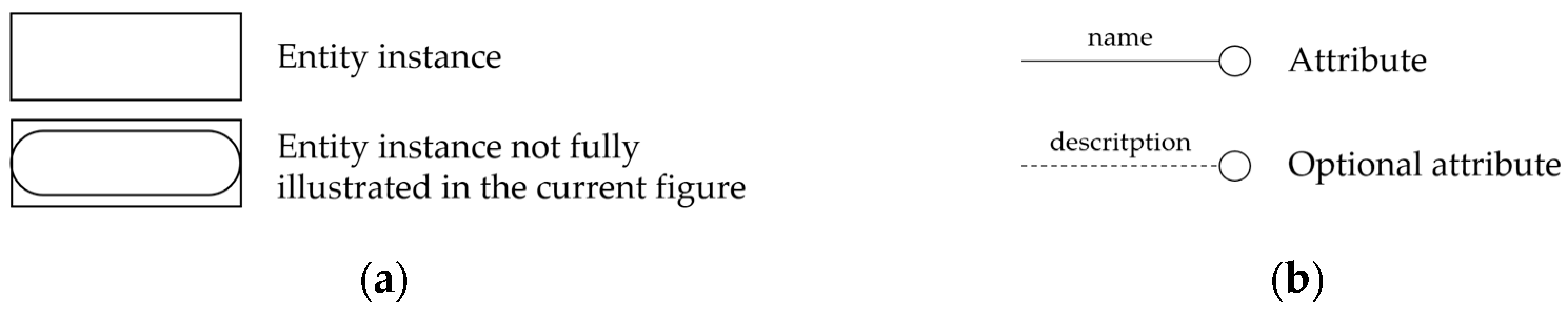

25]. The diagrams reported do not illustrate the entire EXPRESS schema but only a specific subset. The notation adopted is described in

Figure 2, which specifies that the directionality of the attributes is indicated by a graphic symbol placed at the end of the relation, thus highlighting the direction of association between the entities involved.

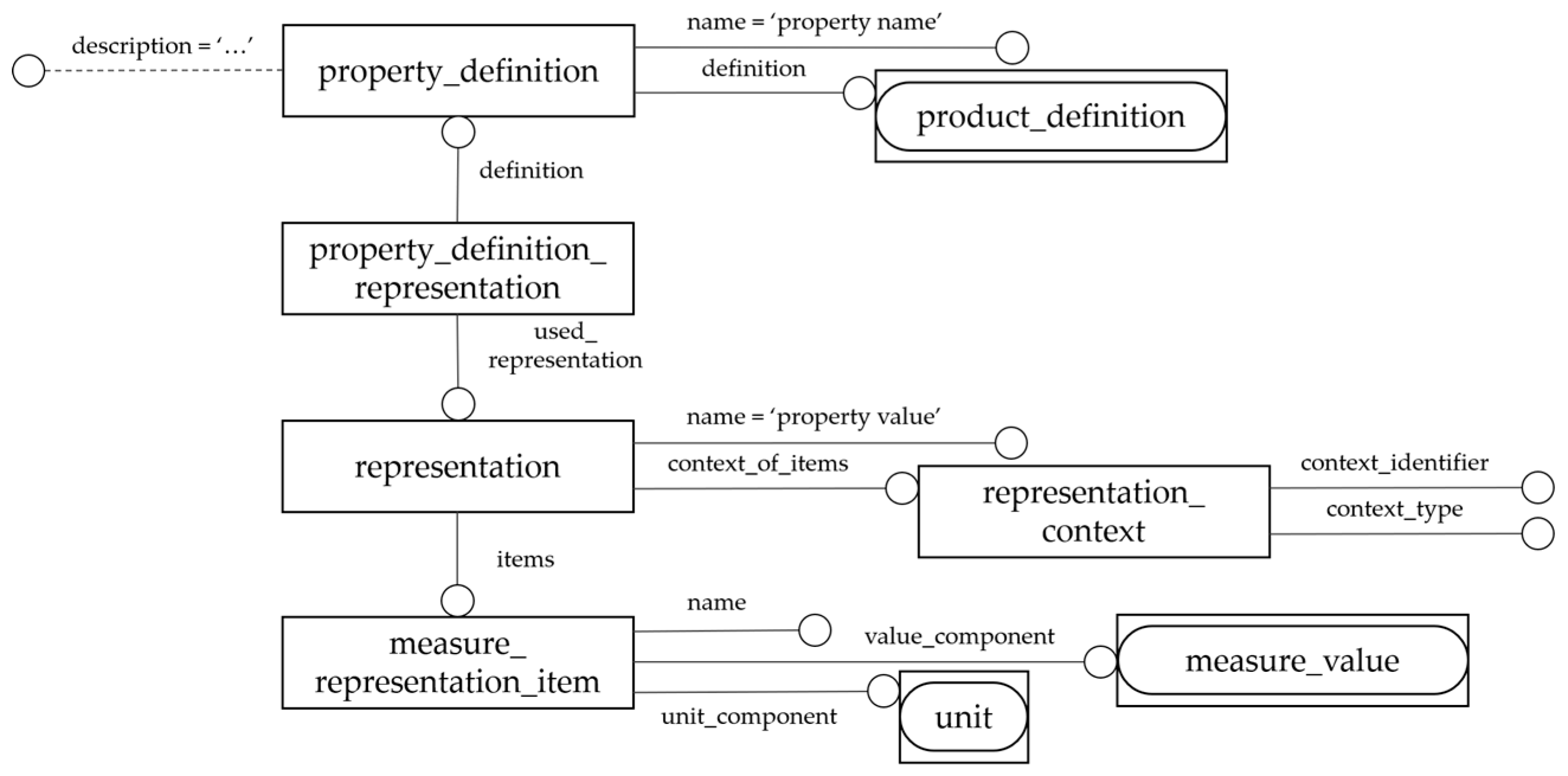

To specify the properties associated with product data, the

property_definition entity is used. This entity enables the association of a measurement with a specific

product_definition. The structure of the relationships between the entities is illustrated in

Figure 3, while a detailed description of the entities involved is provided in

Table 1.

In cases where properties are associated not with a quantitative measurement but rather with a description or a generic textual value, a representation like that shown in

Figure 3 is adopted. In this context, however, the

measure_representation_item entity is replaced by the

descriptive_representation_item class. The latter is characterized by only two attributes:

name and

description, where the

description field represents the value assigned to the property in the form of a textual description.

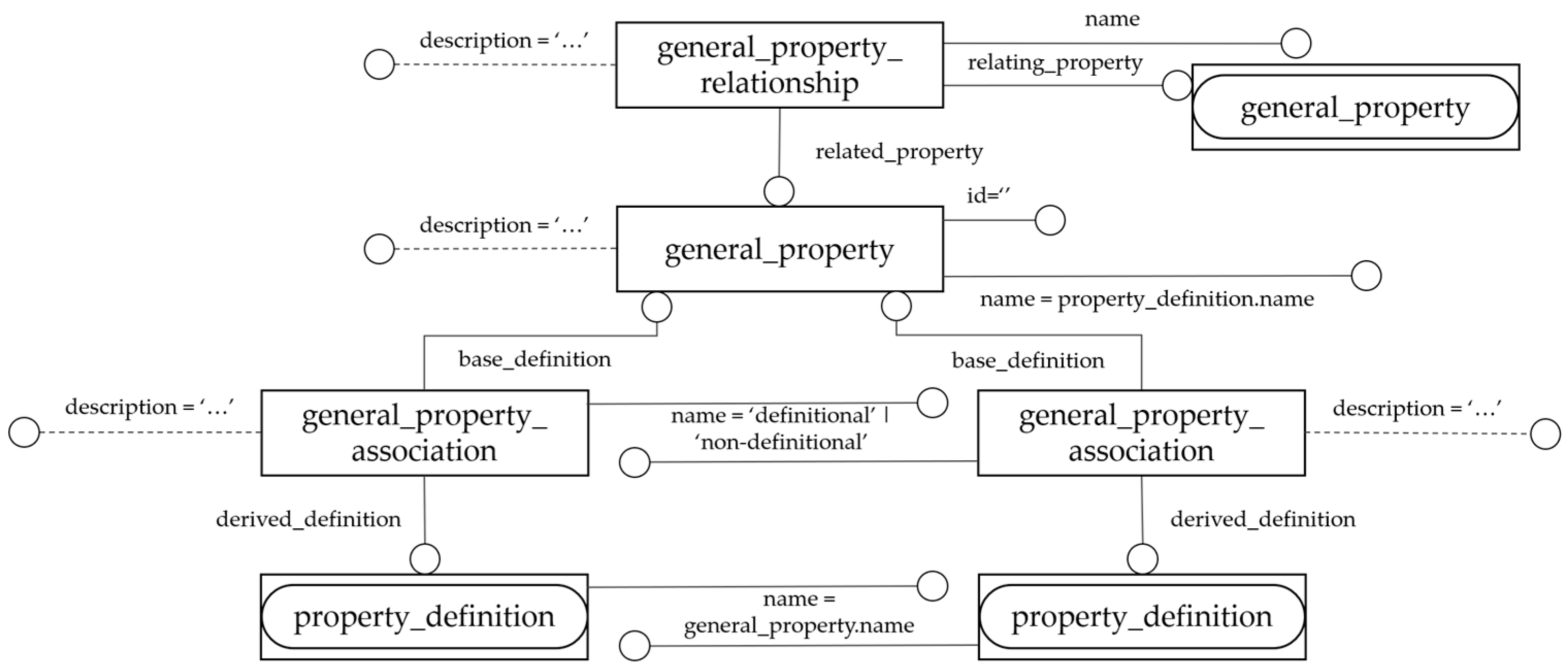

The PDM Schema allows for the identification of properties independently of their actual association with a product. These properties are referred to as

general_property, and they link multiple

property_definition instances of the same type through the

general_property_association entity (i.e. all properties measuring the weight of an object may all be associated with a

general_property named “weight”). The

general_property_association can be of type

definitional if the property can be used to distinguish one product from another, or

non-definitional if it does not represent a distinguishing feature. The PDM schema also supports the specification of relationships between two general property objects. These relationships can be used to indicate that the value of one property can be derived from the value of another. This relation is modeled using the

general_property_relationship entity. The structure of the relationships and the entities involved is illustrated in

Figure 4, while a description of the entities is provided in

Table 2.

2.2.2. Mapping of the Desired Properties

It is necessary to establish a mapping between all properties associated with objects and the corresponding properties defined in the IFC schema. Manufacturing products often include properties that are not relevant to the context of civil design; therefore, an appropriate mapping process allows for the control of information flow and the selection of only the relevant properties. Generally, many of the data relevant to the AEC domain are not included in the STEP file, as they are not considered pertinent for manufacturing purposes. As a result, it is essential to provide the ability to integrate additional data outside the STEP standard.

Within the STEP file, products are not identified by an ID but by a unique Instance Name within the project. Therefore, this identifier must be used to associate properties coming from external sources.

Within the proposed framework, the information is divided into two main categories:

Simplification information: includes data required for the proper functioning of the framework, such as indications on whether to retain or remove elements deemed unnecessary, simplification of their geometry, or potential grouping into assemblies to optimize information management.

Manufacturing and civil product information: includes attributes and properties associated with parts or assemblies, intended to be incorporated as IFC model properties.

2.2.3. Geometries and Assembly Tree Simplification

Within the proposed framework, the process of geometric and informational optimization of STEP models is structured into three distinct phases:

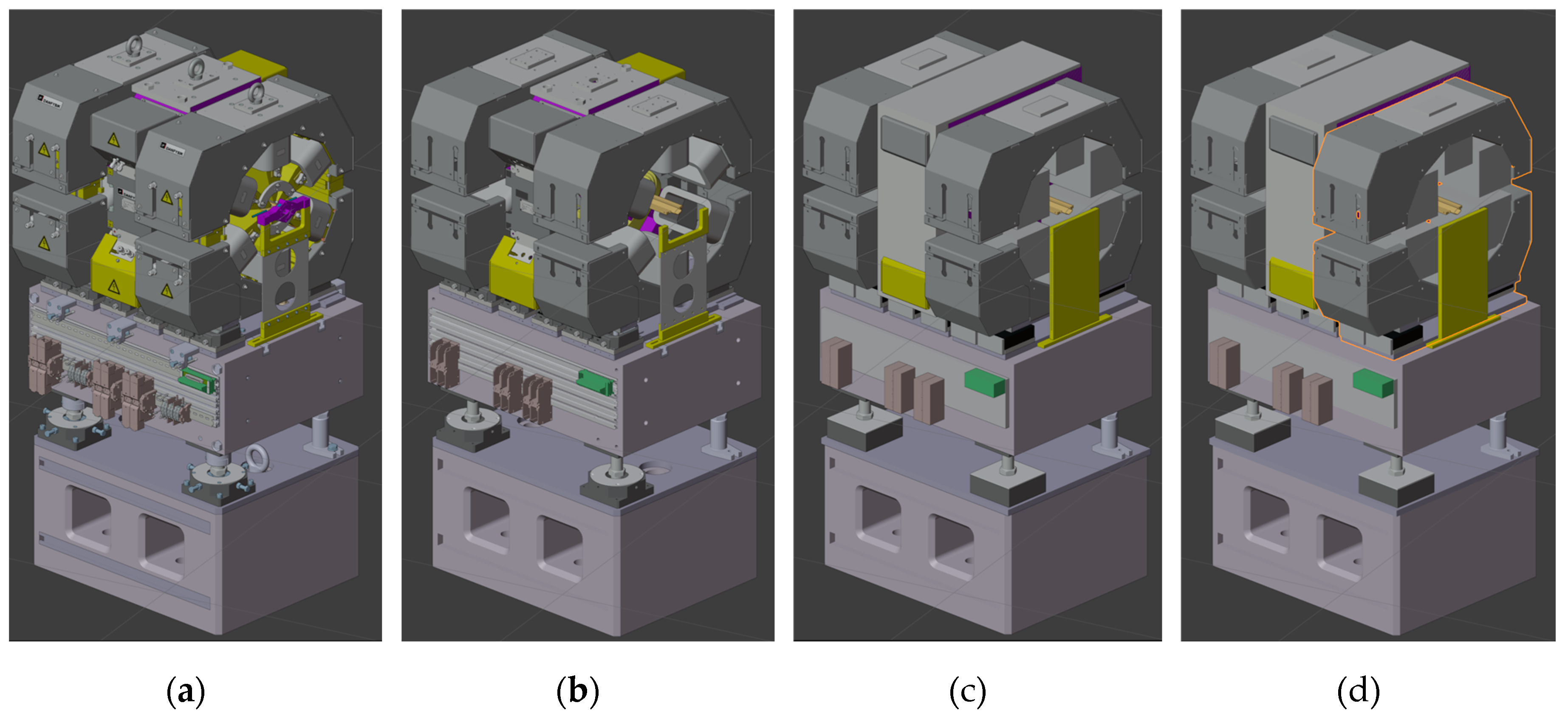

Elimination of non-relevant elements: the STEP file may contain numerous objects and highly detailed geometric features that are not pertinent to the context of civil design. These include very small components (e.g., screws, bolts, flanges, labels) or internal, non-visible parts (such as coils, rotors, circuits, pistons, etc., typically found inside motors or other devices). As shown in

Figure 5b, removing such elements allows for a significant reduction in computational load, thereby improving processing efficiency.

Geometric simplification: as illustrated in

Figure 5a, certain geometric entities can be extremely complex, characterized by a high number of vertices, faces, and triangles, which negatively impact performance. However, in many AEC applications, a high level of detail is not required. It is therefore appropriate to generate simplified versions of these objects or minimal representations such as bounding boxes, given that object identification can also rely on the name or associated attributes and properties. The result of geometric simplification is shown in

Figure 5c.

Aggregation of components into a higher-level assembly: in the AEC domain, the concept of a "product" takes on a different meaning compared to manufacturing, as it operates on a different design scale. Consequently, the detail of individual components becomes less relevant in favor of identifying the final product. It is therefore necessary to define a maximum decomposition level, beyond which individual parts are merged into a single assembly, simplifying information management and reducing model complexity. As shown in

Figure 5d, the selected magnet, highlighted by the orange outline, is treated as a single product, obtained by merging all its constituent components

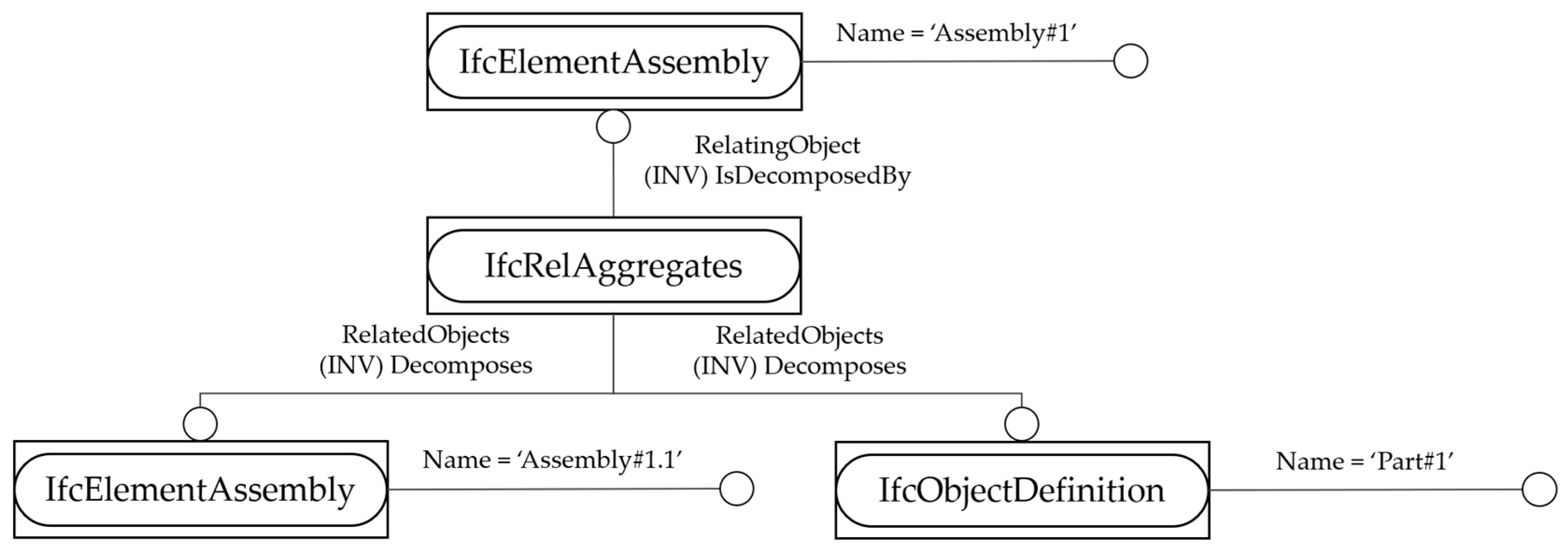

2.2.4. Conversion to IFC Elements with Attributes and Properties Assignment

The final phase of the process involves converting assemblies and individual parts into IFC entities. Assemblies are mapped to the

IfcElementAssembly class, which is specifically designed to represent structures composed of multiple related elements. As illustrated in the example shown in

Figure 6, the

IfcRelAggregates relationship is used to explicitly model the hierarchical decomposition between the assembly and the entities it contains. For the conversion of individual parts, a specific IFC class must be assigned based on the nature of the product. In

Figure 6, this process is represented using the generic abstract class

IfcObjectDefinition, from which the specific IFC types are derived. Depending on the selected class, it is possible to associate dedicated attributes, Property Sets (PSets), and custom properties, ensuring a consistent and comprehensive description of the object.

This procedure enables the faithful reconstruction of the parent-child relationship in the assembly tree within the IFC model, preserving the original information structure and ensuring full interoperability with BIM environments.

3. Results

3.1. Case Study: Elettra 2.0 Light-Machine

Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste S.C.p.A. is a multidisciplinary research center of excellence, open to the international scientific community and active since 1993. Located in Trieste, Italy, the center specializes in the generation of high-quality synchrotron light and free-electron laser radiation. Elettra is actively engaged in the development and operation of two major facilities: Elettra and FERMI. The Elettra machine is currently undergoing a technological upgrade aimed at enhancing its performance. This modernization presents complex challenges, such as the integration of industrial and civil design processes, one of the key aspects addressed in this work.

Synchrotron light is generated by accelerating electrons along a circular trajectory using magnetic and electric fields. As the electrons are forced to bend their path, they emit electromagnetic radiation—known as synchrotron light—due to the energy loss caused by centripetal acceleration. This radiation is directed through dedicated beamlines to experimental stations, where it interacts with samples of various types and sizes, ranging from nanoscale biological systems (e.g., viruses, proteins) to macroscopic materials. The light produced at Elettra and FERMI supports a wide range of scientific disciplines, including chemistry, structural biology, solid-state physics, materials science, nanotechnology, medicine, and cultural heritage science.

3.2. Operational Implementation of the Methodological Framework

The implementation of the proposed framework can be carried out through a variety of approaches, employing different software libraries, application tools, and workflows, depending on specific design and operational requirements. This section presents the workflow adopted by the authors, specifically tailored to the case study under investigation.

The definition of the methodology was preceded by the identification of several key requirements, which guided the selection of tools and the design of the operational architecture:

Open-source: priority was given to the use of open-source formats and tools to ensure reproducibility of the procedure, methodological transparency, and the adoption of open technologies with broad documentation availability. This choice facilitates the advancement of research and promotes the sharing of results without proprietary license constraints or technological barriers.

User-friendly: one of the primary goals was to develop a workflow accessible to a wide range of professionals, including those without advanced IT skills. To this end, emphasis was placed on selecting tools with intuitive graphical interfaces or those already widely used in professional practices such as spreadsheet formats (e.g., CSV). The aim is to reduce adoption barriers and promote the integration of the framework in real-world operational contexts.

3.2.1. Tools Selection Criteria

The workflow developed for the implementation of the framework is based on the use of Blender [

26], one of the most widely adopted free open-source software platforms for three-dimensional geometric modeling [

27], integrated with the Bonsai extension [

28] (formerly BlenderBIM), specifically designed for managing models in the IFC format. The choice of Blender was driven by several strategic factors: its broad adoption within the technical and scientific community, the availability of comprehensive Application Programming Interface (API) documentation, and the presence of an integrated Python development environment. The latter not only provides full access to Blender’s native APIs but also allows the integration of external libraries, thereby enhancing the extensibility and customization of the workflow.

An additional advantage lies in the possibility of creating dedicated user interfaces for executing custom scripts. This feature makes the operational process accessible even to users with limited programming experience, aligning with the usability requirement defined during the design phase.

A challenge encountered when using Blender is its inability to directly import STEP files, which are widely used in manufacturing and CAD contexts. To address this limitation, it was necessary to identify an exchange format compatible with Blender and capable of effectively conveying both geometric and semantic information required by the workflow. Among the supported formats, glTF 2.0 (Graphics Library Transmission Format) was selected, as it represents an open standard that is efficient and well-aligned with Blender’s architecture.

3.2.2. glTF 2.0

The Graphics Library Transmission Format (glTF), developed and maintained by the Khronos Group, is an open and neutral format designed for the efficient transmission and representation of three-dimensional content. Tailored to optimize real-time loading and rendering, glTF is structured as a set of files that work together to comprehensively describe a 3D scene:

A main JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file (.gltf), containing the structural description of the scene, including node hierarchies, materials, cameras, animations, and references to geometry and texture data;

One or more binary files (.bin), storing high-density buffered data such as meshes and animations;

Image files (.jpg, .png) used to define textures associated with materials.

The modular and compact structure of the glTF format allows for fast parsing and efficient access to information, promoting interoperability across platforms and applications. The format implements a node-based hierarchy for scene representation, analogous to the assembly tree used in the manufacturing domain, where each node may represent either an assembly or a part.

A distinctive feature of glTF is its ability to semantically extend entities via arbitrary key-value properties defined within the

extras field. This capability enables the customized annotation of nodes, meshes, or other model entities, supporting the integration of domain-specific metadata across a variety of application areas [

29],including engineering and industrial contexts.

While this work does not provide a detailed analysis of all entities defined in the glTF format, a comprehensive overview can be found in the official documentation published by the Khronos® 3D Formats Working Group [

30].

3.2.3. STEP to glTF 2.0

As is commonly the case in manufacturing design processes, the source files in this case study did not contain part or assembly level property data. Descriptive information related to the products was instead managed externally using spreadsheet files in CSV format. For this reason, it was not necessary to develop a dedicated parsing module to map STEP file properties to IFC entities for subsequent integration into the glTF file. While this step is conceptually outlined, it has been deferred to future work. In this context, the development of a tool that can accurately convert geometry and selectively map semantic properties from the STEP model in a configurable manner will be essential.

In the present work, the only content requiring processing involved the geometric data and hierarchical structure of the assembly tree. For this purpose, Mayo [

31], an open-source software application designed for CAD model visualization and conversion, was used. Among the various tools available, Mayo was selected for its flexible export options, particularly its ability to save each object with its corresponding

Instance Name or

Product Name. The decision to export using the

Instance Name proved to be strategic, as this identifier serves as a unique key within the CAD model structure and forms the basis for the automated association of properties from the CSV files in the current workflow.

The workflow for converting STEP to glTF is illustrated in

Figure 7.

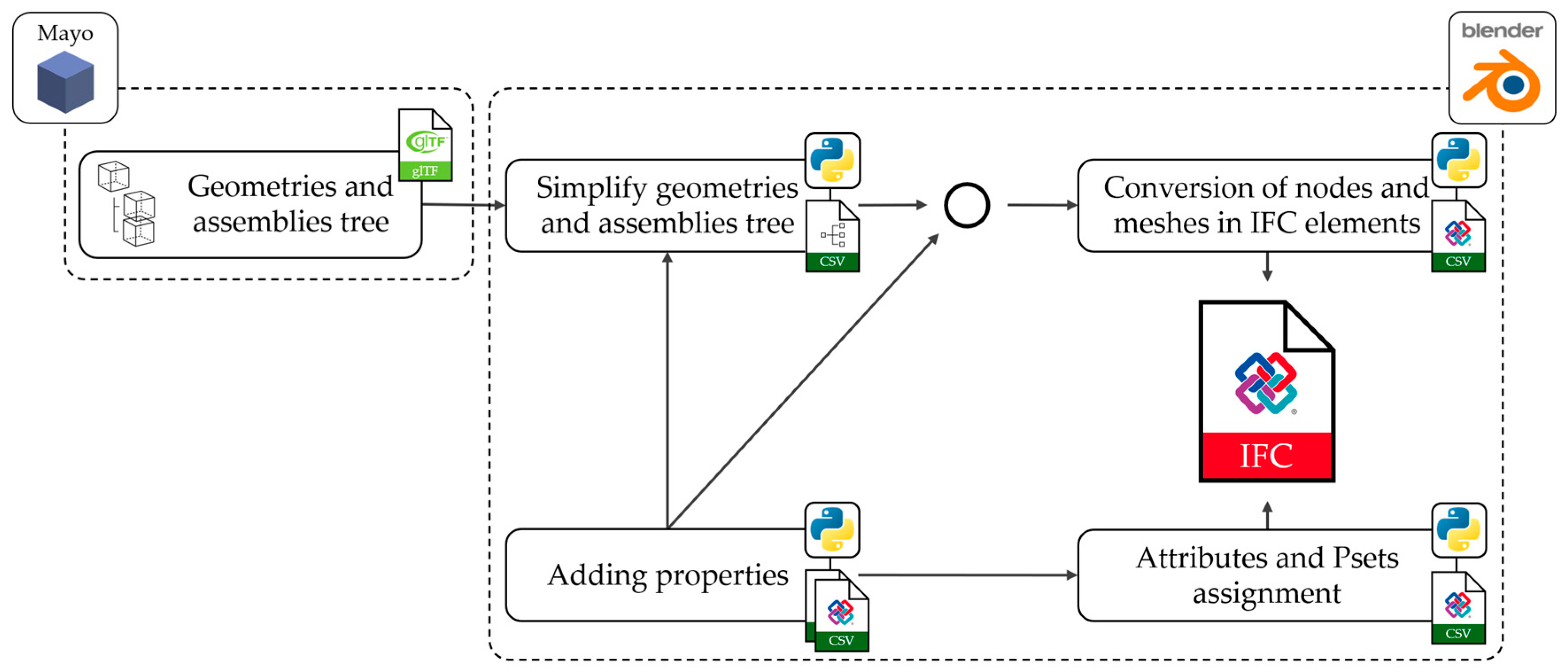

3.2.4. glTF to IFC: Blender Add-On

A custom add-on for Blender [

32] was developed, featuring an intuitive user interface, to manage the conversion process according to the workflow illustrated in

Figure 8. The process begins with the import of a glTF-format file into Blender. Then, by processing two separate CSV files, the workflow proceeds with the simplification of geometries and the hierarchical structure of assemblies, based on the data contained in the first CSV (related to simplification), and the conversion of the meshes into IFC elements, complete with attributes and Property Sets derived from the second CSV file containing the semantic IFC data.

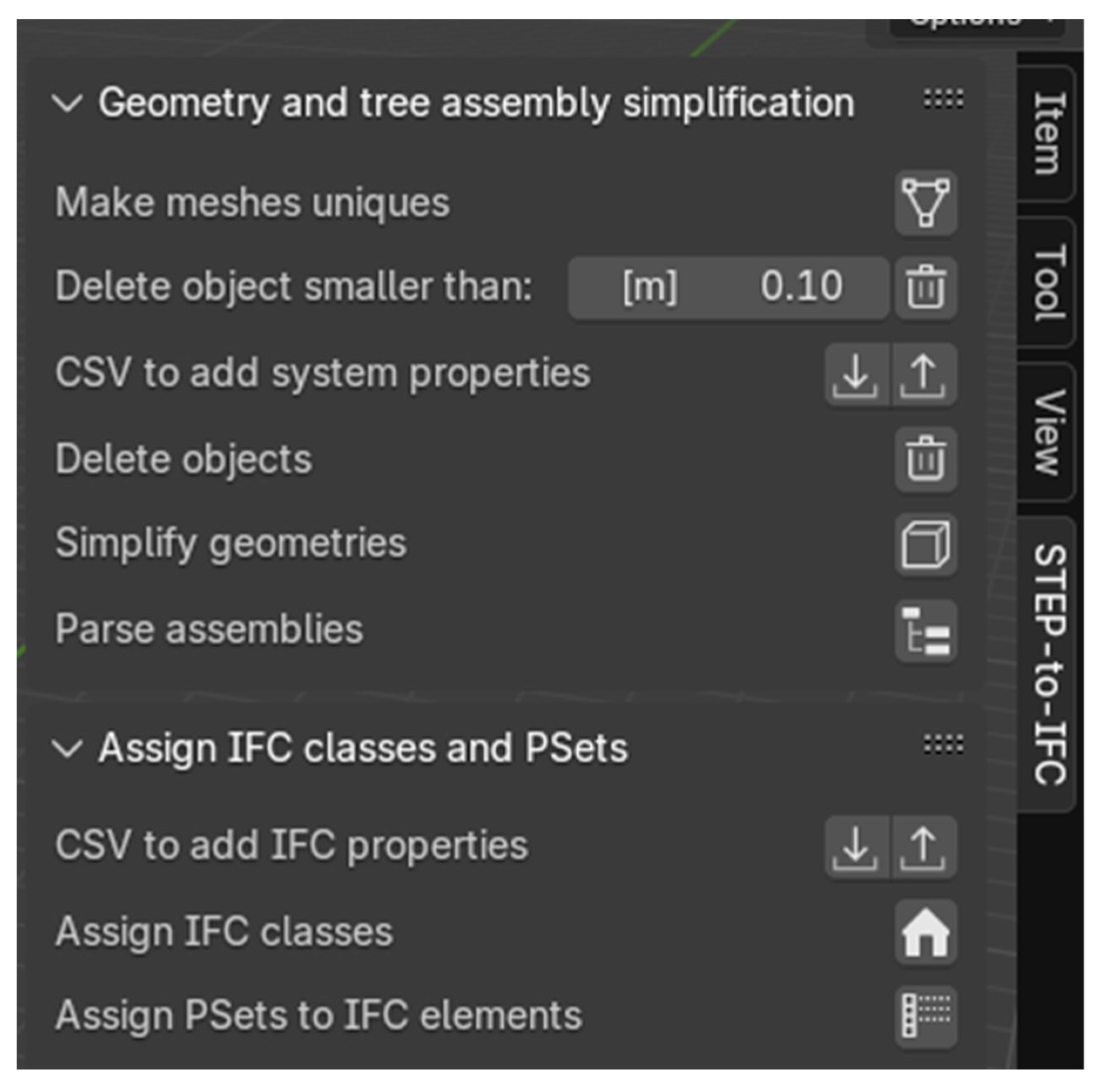

Blender supports the development of add-ons with customizable user interfaces, enabling the creation of intuitive workflows that are accessible even to users without specific programming skills. The add-on developed for this work, as illustrated in

Figure 9, is structured into two main panels, each containing a set of commands dedicated to the different phases of the conversion process.

The first panel handles the simplification of geometries and the hierarchical structure of assemblies through the following commands:

Make meshes unique: Blender allows the instantiation of objects based on the same mesh to optimize memory usage by applying spatial transformations (translation, rotation, and scaling). However, this approach is incompatible with subsequent processing steps that require the merging and transformation of meshes. Therefore, the script generates independent copies of the meshes, making them individually editable

Delete small objects: this command automatically deletes all objects with dimensions smaller than a defined threshold along the X, Y, and Z axes, removing negligible components (e.g., screws, bolts, flanges). This step is not mandatory, and targeted object deletion can still be performed in a later phase.

CSV to add system properties: a CSV file is generated containing hierarchical information about the parts within the assembly tree. The user is asked to fill in three columns: “To be deleted”, “To be simplified”, and “To be grouped under”. The first column indicates if a part should be removed; the second specifies whether the geometry should be simplified using a bounding box; the third defines the destination assembly for grouping and merging parts, as shown in

Table 3.

Delete objects: removes all meshes marked as "Yes" in the “To be deleted” column of the imported CSV. Subsequently, assemblies without content are deleted to reduce scene complexity.

Simplify geometries: Replaces meshes marked as "Yes" in the “To be simplified” column of the CSV with their corresponding bounding boxes while preserving the original material.

Parse assemblies: Groups the meshes under the assemblies defined in the “To be grouped under” column of the CSV. Meshes belonging to the same assembly are then merged into a single object, further optimizing the hierarchical structure.

This second section focuses on the assignment of IFC classes and associated properties through the following commands:

CSV to add IFC properties: Generates a CSV file containing all meshes with their respective paths in the assembly tree. The user must specify the IFC class to assign to each object, the

Predefined Type, and, if necessary (in the case of USERDEFINED), the

Object Type. Additionally, columns with headers

Pset_Name/Prop_Name can be added to define the desired Property Sets and their corresponding properties, entering the values in the corresponding cells, as shown in

Table 4.

Assign IFC classes: Assigns the specified IFC class, Predefined Type, and, if required, Object Type to each mesh, according to the CSV content.

Assign PSets to IFC elements: Assigns Property Sets and properties to the IFC elements in accordance with the content of the CSV. If multiple properties belong to the same PSet, they are correctly grouped, in compliance with the IFC standard.

3.3. Results Analysis

Given the multiple possible approaches to implementing this framework, it is equally important to evaluate its performance to identify the most effective tools and workflows.

As shown in

Table 5, the geometric compression ratio is particularly significant, with a reduction in the number of vertices and faces by 91,41% and 90,54%, respectively, and a decrease in the total number of objects by 99,05%. The average time required to complete the entire process, from the conversion of the STEP file into glTF format to the final export in IFC format, is approximately 254 seconds, a duration considered fully acceptable for practical applications.

The most time-consuming phase, which has been excluded from the timing analysis due to the high variability of influencing factors, is the compilation of CSV files. This operation, typically carried out using spreadsheet software, is highly dependent on the user’s proficiency in applying filtering, grouping, and bulk editing operations across large datasets. The decision to adopt the CSV format was driven by its wide adoption, flexibility, and its ability to support fast data input, particularly when used with an adequate level of expertise.

Finally, the size of the resulting IFC files remains sufficiently compact to ensure usability even on mid-range hardware systems, without compromising overall performance.

4. Discussion

The proposed framework offers a structured and controlled approach to converting data from the STEP format to the IFC-SPF format and has been specifically designed to meet the needs of civil-oriented design processes. The originality and scientific value of this work lie in the development of a methodological framework and an operational implementation workflow that bridges the industrial and AEC domains using open and interoperable standards.

In contrast to generic approaches that rely on the automatic conversion of meshes into generic IfcBuildingElementProxy entities—often without regard for the semantic structure of the product or the computational weight of the resulting meshes—this framework introduces a systematic process for assigning specific IFC classes and coherent properties based on the original nature and function of the components. This results in a high level of control over the transformation process, enabling significant flexibility and adaptability to different project contexts and requirements. The contribution should therefore not be viewed as a mere conversion tool, but as a system designed to adapt industrial product logic to the information needs of the AEC domain. Moreover, the framework is designed to be compatible with a variety of libraries, tools, and operational logics, enhancing its portability and integration across different digital environments.

The practical application of the framework presents several advantages. First, the exclusive use of widely adopted open-source tools—such as Blender—makes the procedure reproducible, accessible, and sustainable. Second, the ability to develop a clear and functional user interface, accessible even to users without programming skills, supports its widespread use in both academic and professional settings.

Despite the numerous benefits offered by the framework, some limitations remain that require further development. One important area for future work concerns the completion of the functional branch dedicated to mapping properties from STEP to glTF format, which is not yet fully implemented. A significant limitation of the current approach lies in the geometric representation of meshes, which are exported to IFC using tessellated geometry. Specifically, meshes are encoded as

IfcPolygonalFaceSet entities, with surfaces described through lists of coordinates (

IfcCartesianPointList3D) for each vertex. While this ensures a faithful geometric representation, it also leads to a substantial increase in the size of the resulting IFC file due to the large number of points stored. For this reason, the development of alternative strategies for geometry export—aimed at improved efficiency—is required. These strategies may involve the use of more compact representation methods, such as Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG), sweep geometries, Boundary Representation (BRep), and tessellation, all supported by IFC [

33]. For tessellated representation, enhanced simplification techniques can be applied to reduce the number of vertices while maintaining sufficient geometric and information quality.

Lastly, as the framework is designed to be modular and adaptable, it will be essential to conduct comparative test campaigns using different tools, libraries, methodologies, and representation logics. The aim is to assess the impact of each approach both in terms of computational performance and the quality and compactness of the resulting IFC file.

Funding

This research was funded by DM 117/2023.

Data Availability Statement

The models and data used in this study are the property of Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste S.C.p.A. and cannot be shared publicly due to privacy and confidentiality restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste S.C.p.A. for their technical support, for providing the materials used in the case study, and for granting permission to publish selected images of mechanical components from the Elettra 2.0 project. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT4 and DeepL Translator for the purposes of translation and grammar and spelling check. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEC |

Architectural, Engineering and Construction |

| AP |

Application Protocol |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| BIM |

Building Information Model |

| CAD |

Computer-Aided Design |

| glTF |

Graphics Library Transmission Format |

| IFC |

Industry Foundation Classes |

| IFC-SPF |

IFC STEP Physical File |

| IGES |

Initial Graphics Exchange Specification |

| JSON |

JavaScript Object Notation |

| JT |

Jupiter Tessellation |

| PDM |

Product Data Management |

| PMI |

Product Manufacturing Information |

| QIF |

Quality Information Framework |

| STEP |

STandard for the Exchange of Product data |

| STL |

STereo Lithography interface format |

References

- ISO 10303-21; 2016.

- ISO 16739-1; 2024.

- Nzetchou, S.; Durupt, A.; Remy, S.; Eynard, B. Semantic Enrichment Approach for Low-Level CAD Models Managed in PLM Context: Literature Review and Research Prospect. Computers in Industry 2022, 135, 103575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, A.B.; Frechette, S.P.; Srinivasan, V. A Portrait of an ISO STEP Tolerancing Standard as an Enabler of Smart Manufacturing Systems. Journal of computing and information science in engineering 2015, 15, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, C.; Xu, X. Standards for Smart Manufacturing: A Review.; IEEE, 2019; pp. 73–78.

- Xiao, J.; Anwer, N.; Durupt, A.; Le Duigou, J.; Eynard, B. Information Exchange Standards for Design, Tolerancing and Additive Manufacturing: A Research Review. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM) 2018, 12, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, L. Smart Manufacturing Process and System Automation – A Critical Review of the Standards and Envisioned Scenarios. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2020, 56, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14306-1; 2024.

- Katzenbach, A.; Handschuh, S.; Vettermann, S. JT Format (ISO 14306) and AP 242 (ISO 10303): The Step to the next Generation Collaborative Product Creation.; Springer, 2013; pp. 41–52.

- ISO 23952; 2020.

- Ram, P.S.; Deepak Lawrence, K. Implementation of Quality Information Framework (QIF): Towards Automatic Generation of Inspection Plan from Model-Based Definition (MBD) of Parts. In Proceedings of the Industry 4.0 and Advanced Manufacturing; Chakrabarti, A., Arora, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, M.; Kiviniemi, A. The IFC Standard: A Review of History, Development, and Standardization, Information Technology. ITcon 2012, 17. [Google Scholar]

- buildingSMART Technical IFC Formats. Available online: https://technical.buildingsmart.org/standards/ifc/ifc-formats/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ji, Y.; Borrmann, A.; Beetz, J.; Obergrießer, M. Exchange of Parametric Bridge Models Using a Neutral Data Format. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering 2013, 27, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielingh, W. An Assessment of the Current State of Product Data Technologies. Computer-Aided Design 2008, 40, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillinger, S.; Esche, E.; Tolksdorf, G.; Welscher, W.; Wozny, G.; Repke, J.-U. Data Exchange for Process Engineering – Challenges and Opportunities. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2019, 91, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Curating Architectural 3D CAD Models. IJDC 2009, 4, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, A.J.; Swindells, N.; Archer, E.; McIlhagger, A.; Sung, A.; Leong, K.; Jones, R. A Review of Composite Product Data Interoperability and Product Life-Cycle Management Challenges in the Composites Industry. Advanced Manufacturing: Polymer & Composites Science 2017, 3, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13584-42; 2010.

- Swindells, N. The Representation and Exchange of Material and Other Engineering Properties. Data Sci. J. 2009, 8, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STEP Tools AIM EXPRESS Text: STEP Schemas. Available online: https://steptools.com/stds/stp_aim/html/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- STEP Tools AIM: STEP Integrated Definitions Diagram. Available online: https://steptools.com/stds/stp_expg/aim.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Lipman, R.R.; Astheimer, R. STEP File Analyzer and Viewer Available online: https://www.nist.gov/services-resources/software/step-file-analyzer-and-viewer.

- Gu, P.; Chan, K. Product Modelling Using Step. Computer-Aided Design 1995, 27, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerer, M.; Rosché, P. Usage Guide for the STEP PDM Schema V1.2. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blender 2025.

- Malta, A.; Farinha, T.; Cardoso, A.J.M.; Mendes, M. Survey on the Use of BIM Methodology for Railway 3D Modeling. Discover Applied Sciences 2024, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsai 2025.

- Izawa, R.; Koga, M. An Extension of glTF for Robot Description. In Proceedings of the 2019 19th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS); October 2019; pp. 1010–1014. [Google Scholar]

- The Khronos® 3D Formats Working Group glTFTM 2.0 Specification. Available online: https://registry.khronos.org/glTF/specs/2.0/glTF-2.0.html#foreword (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Delorme, H. Mayo Available online: https://github.com/fougue/mayo.

- Avogaro, D. STEP-to-IFC Available online: https://github.com/Daavogaro/STEP-to-IFC.

- Chen, J.; C. Clarke, K. Modeling Standards and File Formats for Indoor Mapping. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management; SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications: Porto, Portugal, 2017; pp. 268–275.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).