Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Chemicals and Instruments

2.3. Separation of Flavonoids O-Glycosides and C-Glycosides

2.4. HPLC-QTOF-MS/ MS Analysis

2.5. In Vitro Simulated Digestion and Fermentation

2.5.1. In Vitro Simulated Digestion

2.5.2. In Vitro Simulated Fermentation

2.5.3. Ethics Statement

2.6. Determination of Antioxidant Activity

2.6.1. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by DPPH Method

2.6.2. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by ABTS Method

2.6.3. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by FRAP Method

2.6.4. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by ORAC Method

2.7. Changes in the Stability of LPF C-Gly and LPF O-Gly

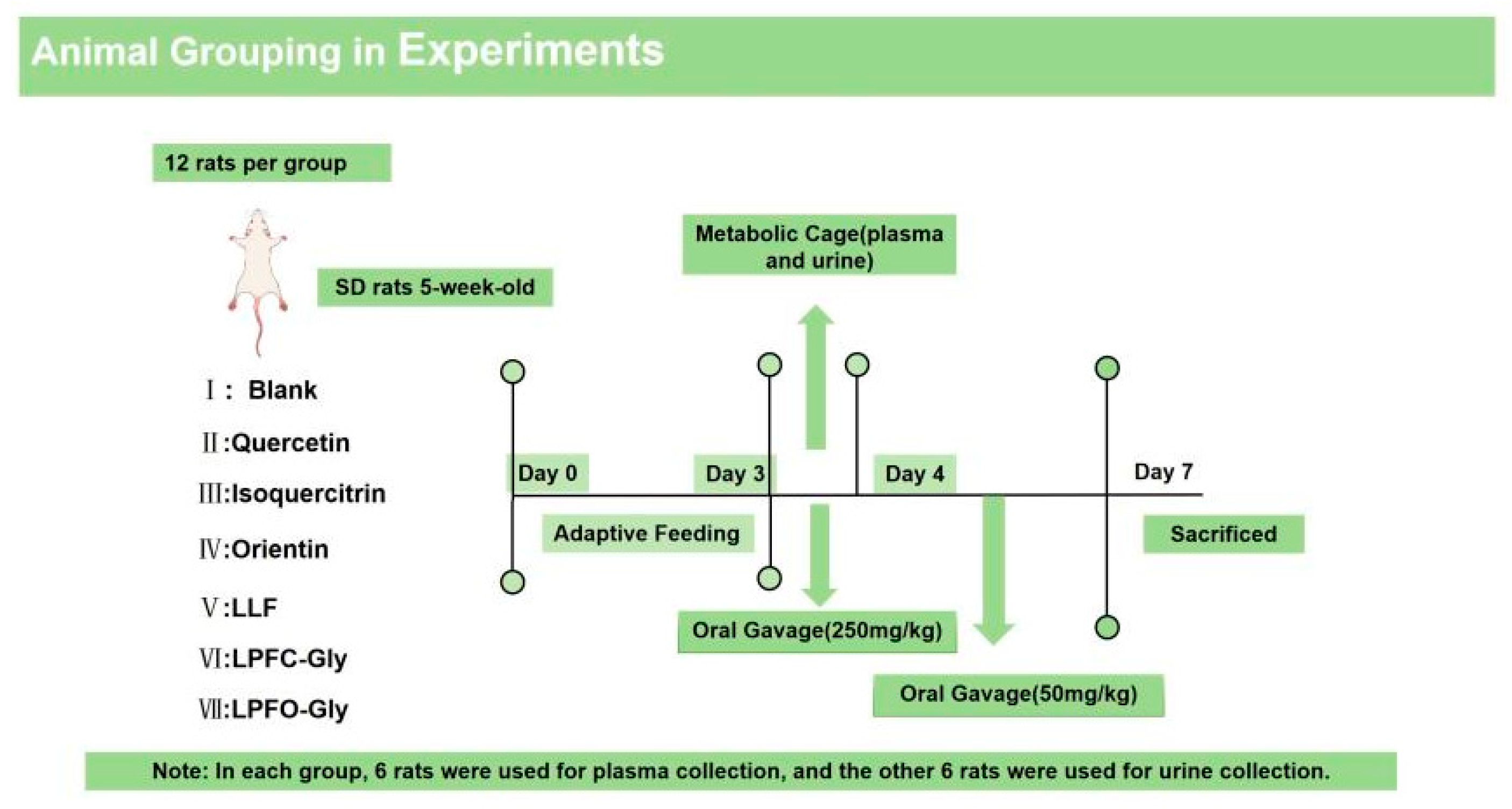

2.8. Animal Experiment

2.8.1. Experimental Animal Grouping

2.8.2. Preparation of Plasma and Urine Samples

2.8.3. Collection of Cecal Contents

2.8.4. Metabolites Identification

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

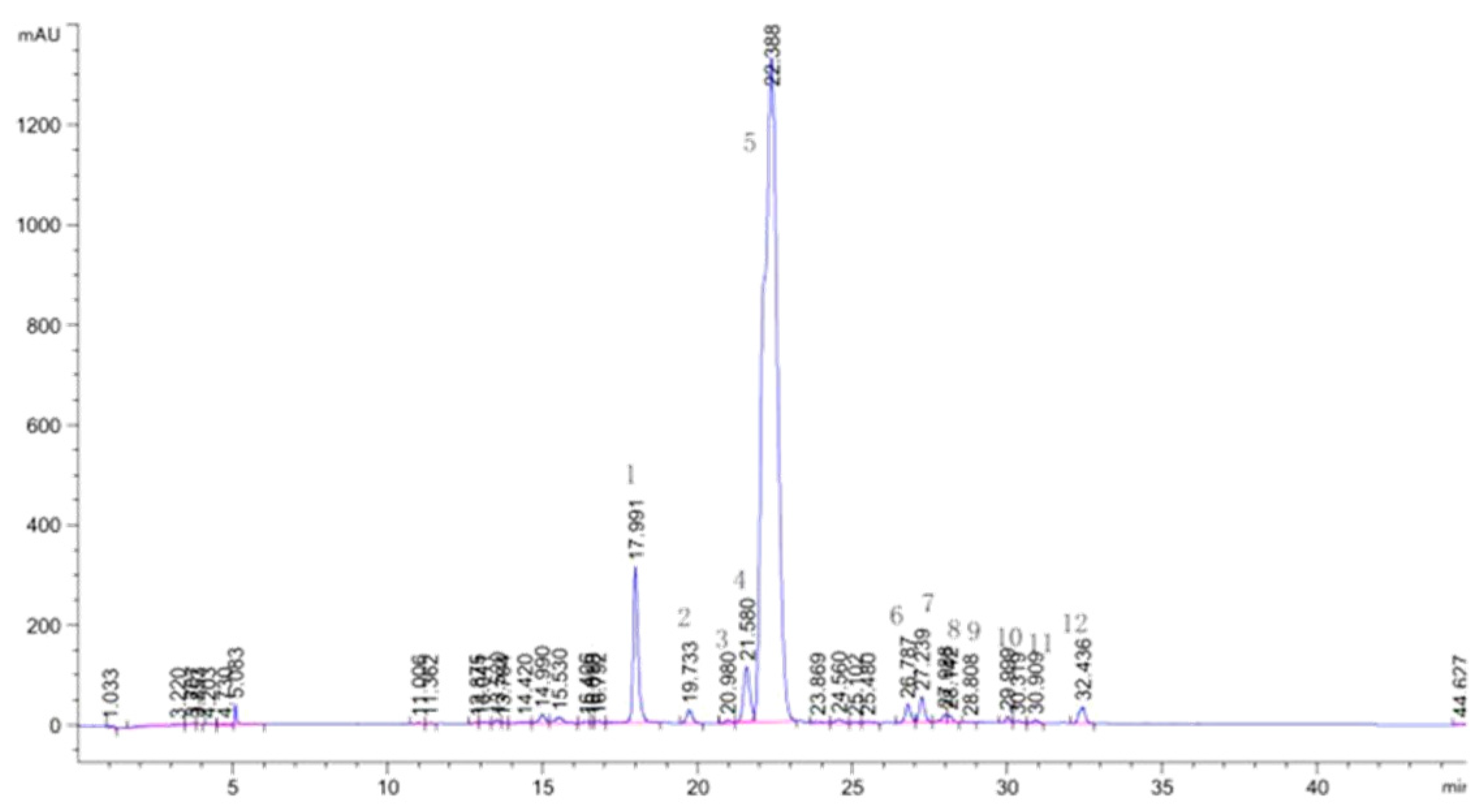

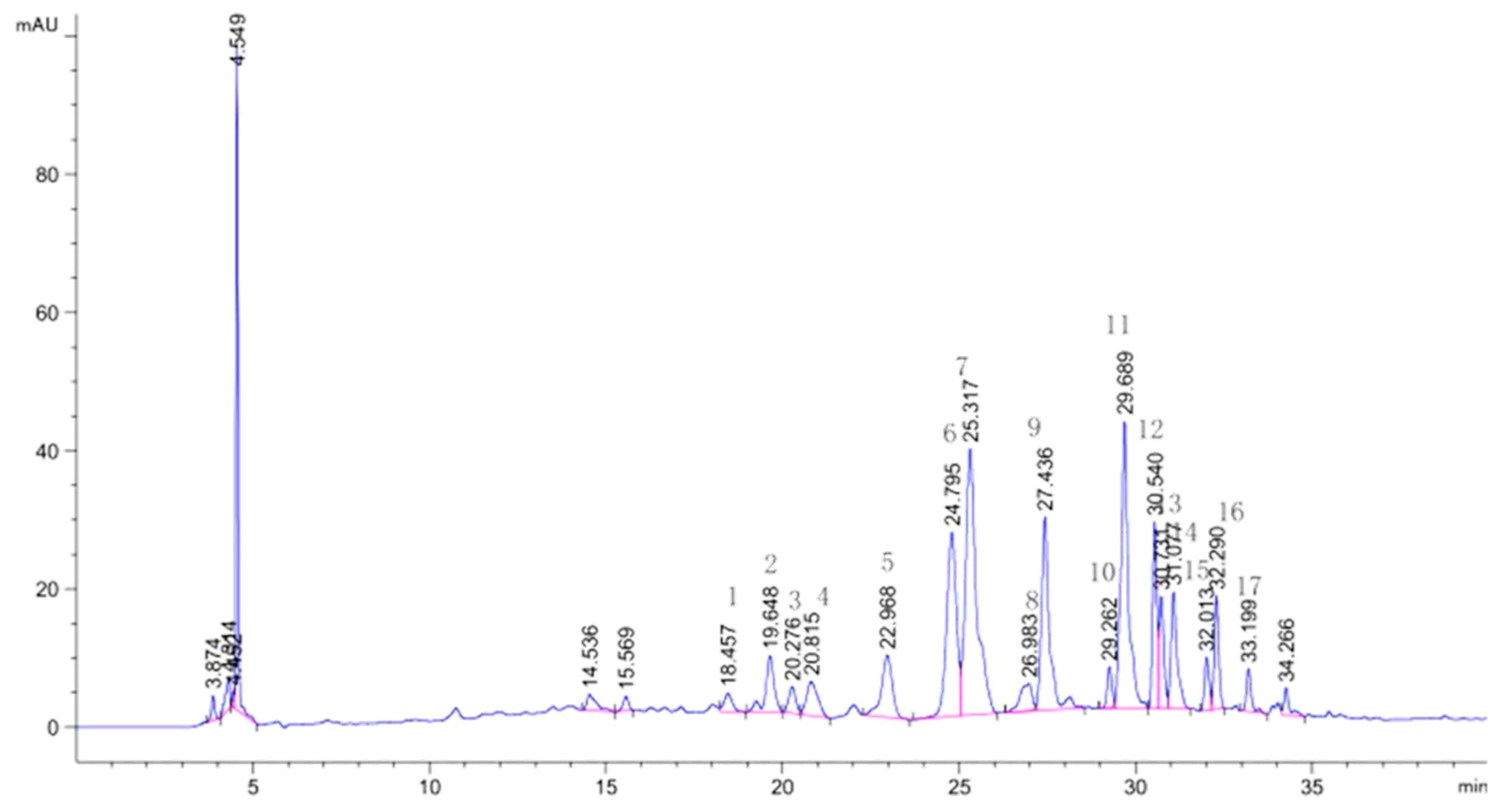

3.1. Identification

3.2. Quantitative Results of LFF, LPF Gly

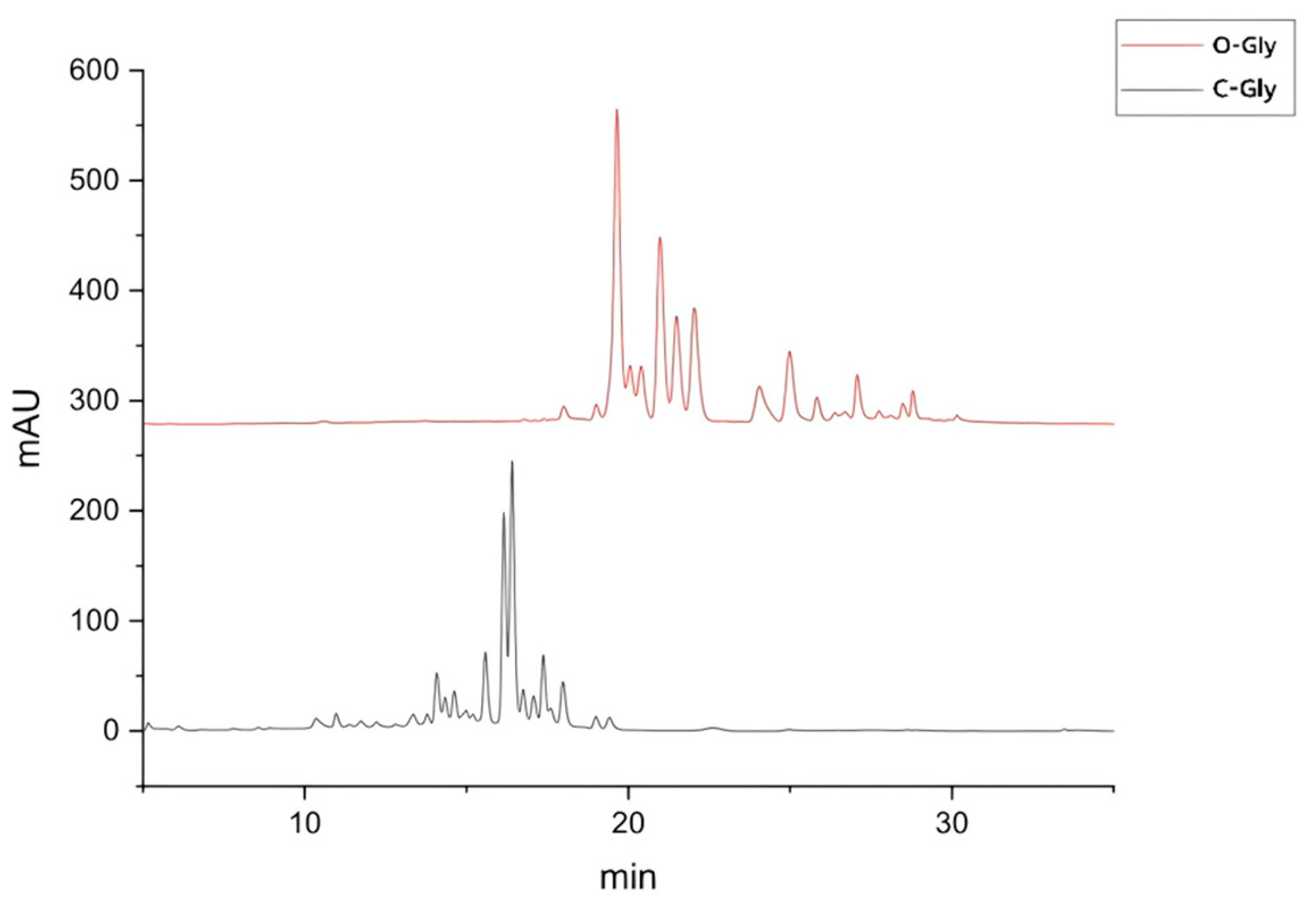

3.3. Separation of LPF C-Gly and LPF O-Gly

3.4. Antioxidant Activity In Vitro Digestion and Fermentation

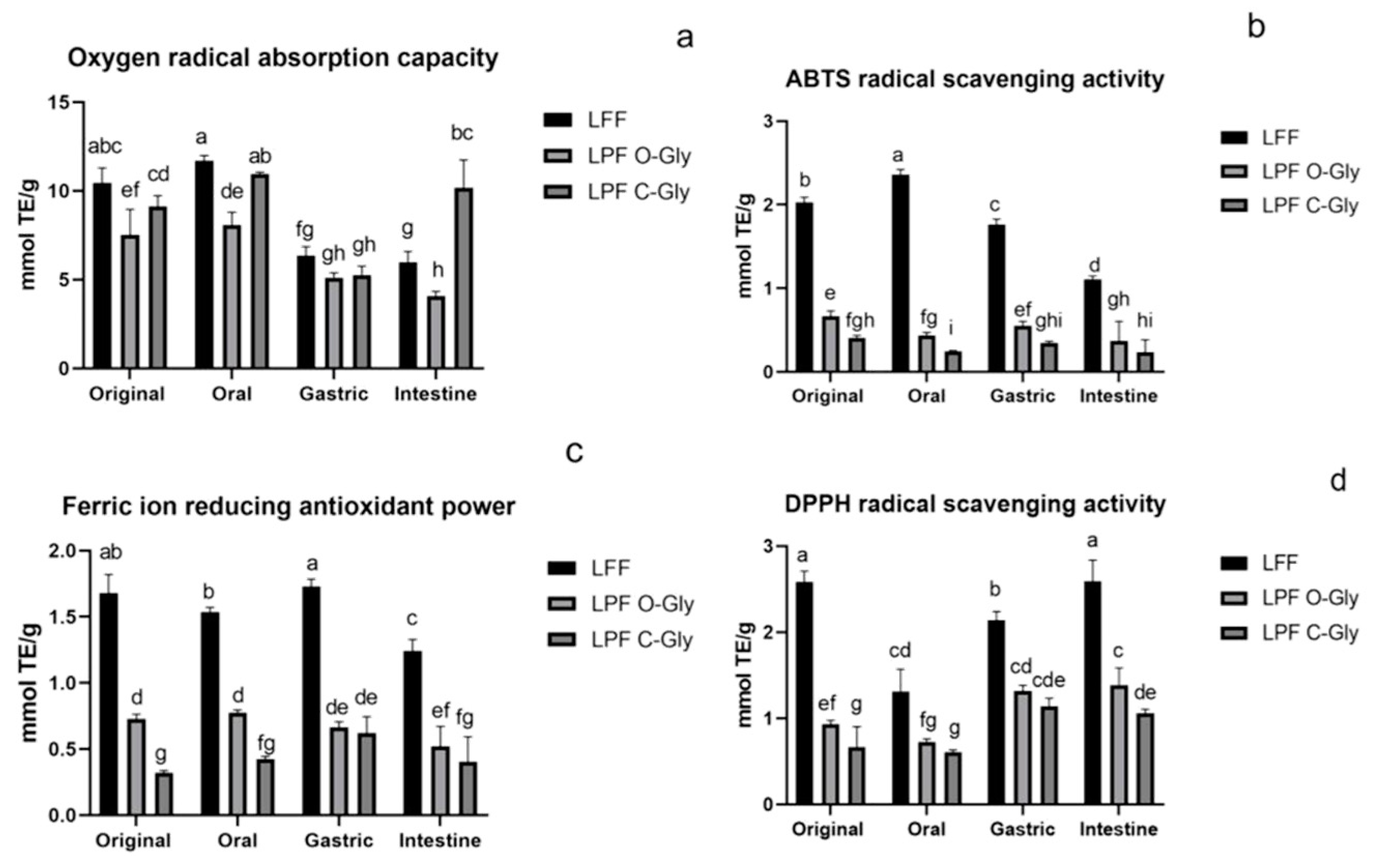

3.4.1. Antioxidant Activity In Vitro Digestion

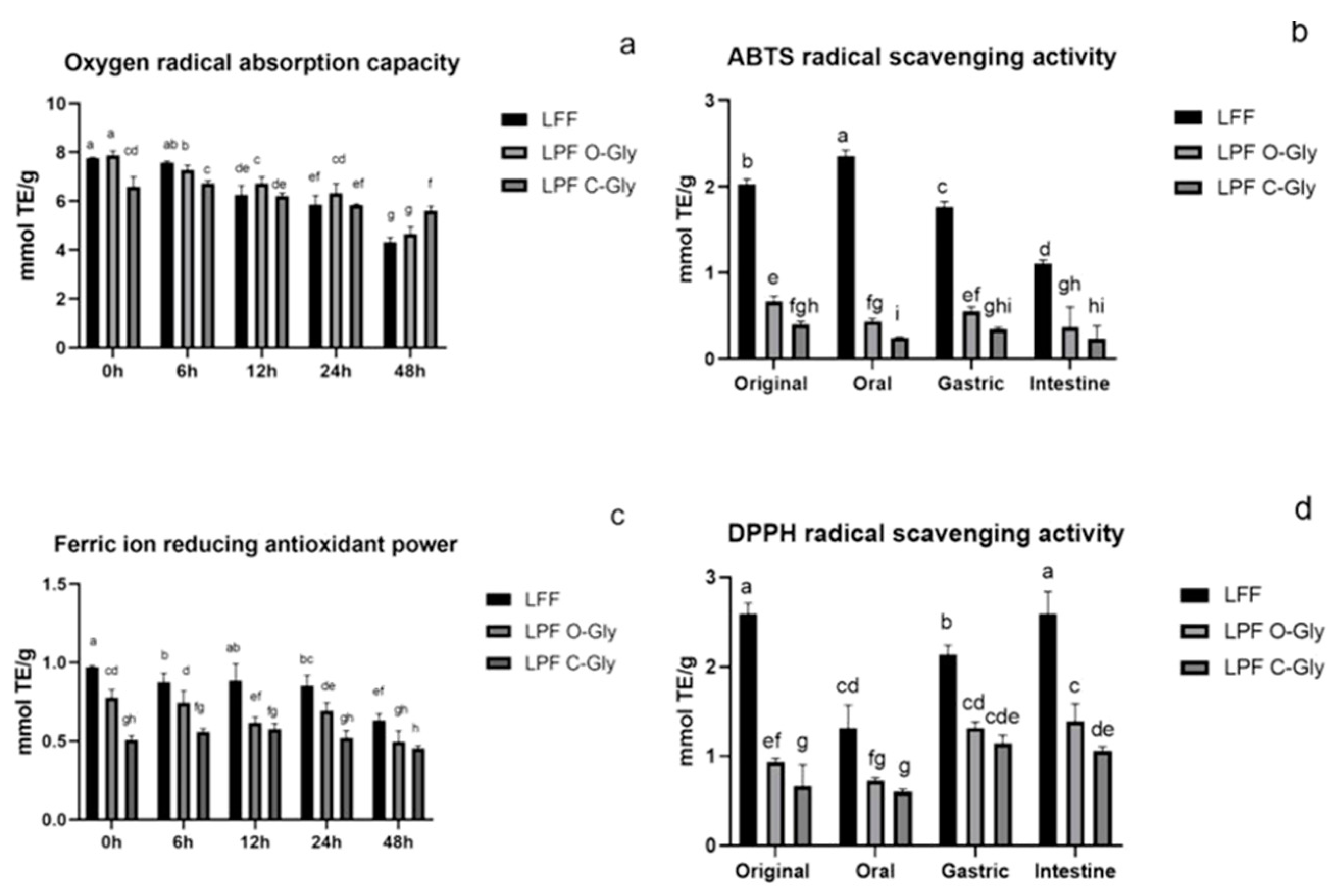

3.4.2. Antioxidant Activity In Vitro Fermentation

3.5. Stability Change of LFF、LPF C-Gly and LPF O-Gly During In Vitro Digestion and Fermentation

3.5.1. Stability Changes of LFF、LPF C-Gly and LPF O-Gly During In Vitro Digestion

3.5.2. Stability Changes of LFF、LPF C-Gly and LPF O-Gly During In Vitro Fermentation

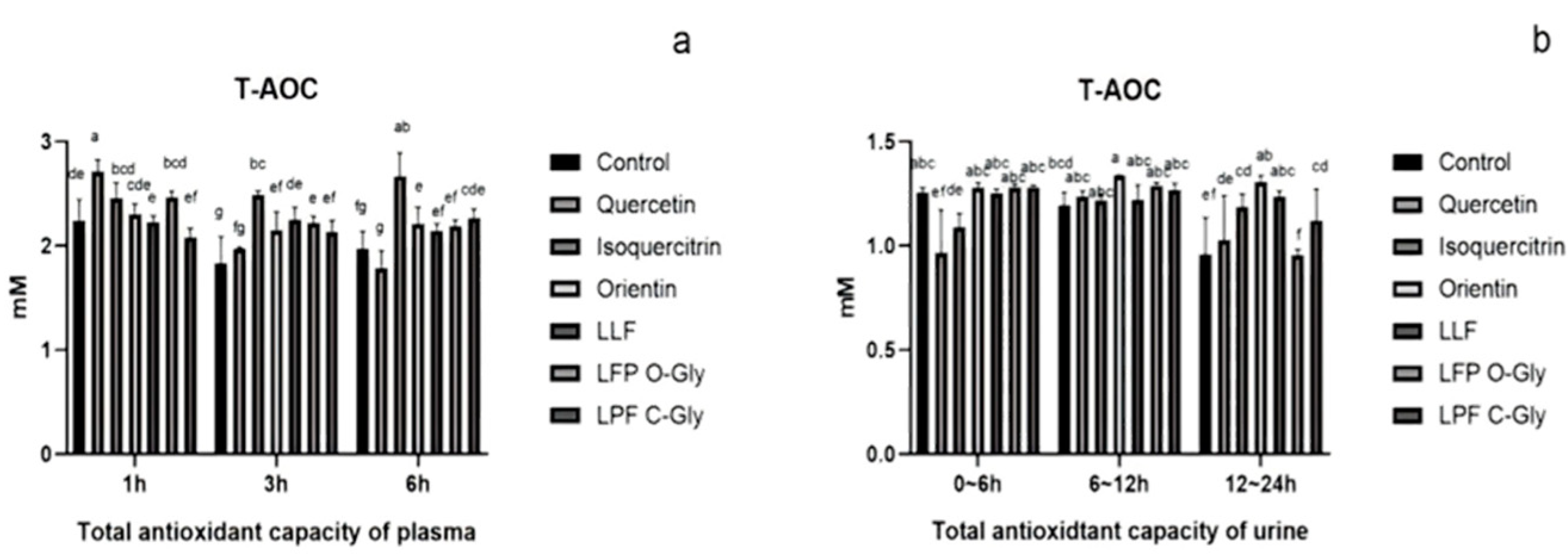

3.6. Animal Experimental Results

3.6.1. Metabolic Differences Between C-Glycosides and O-Glycosides in Plasma and Urine

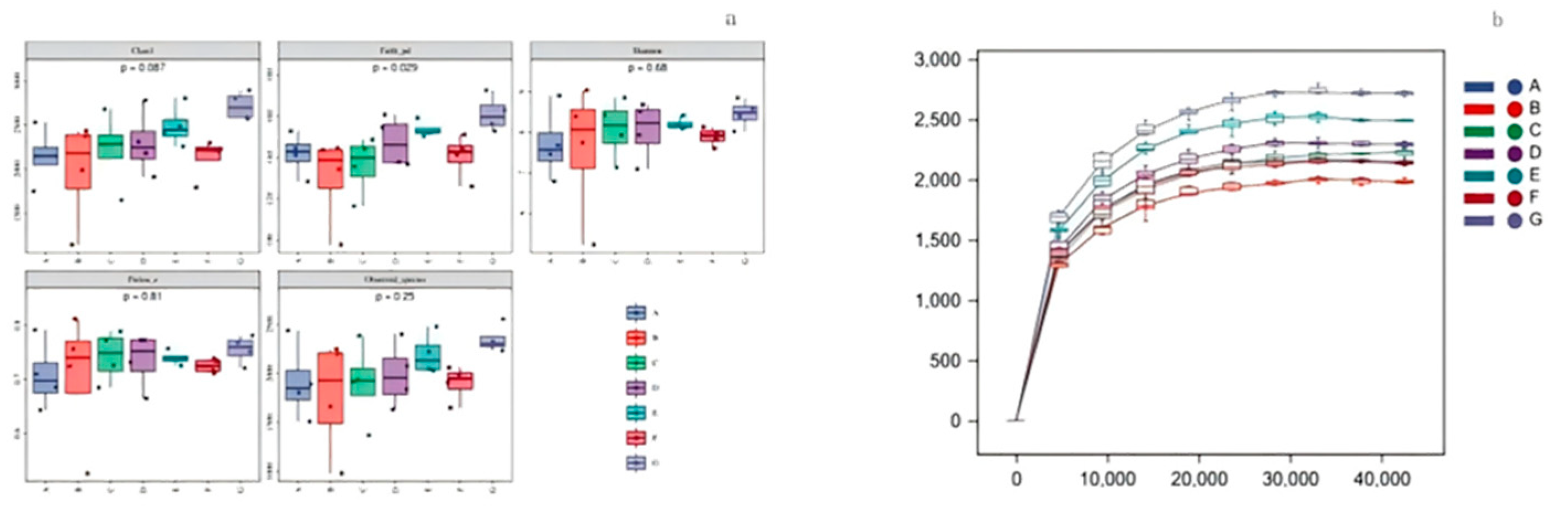

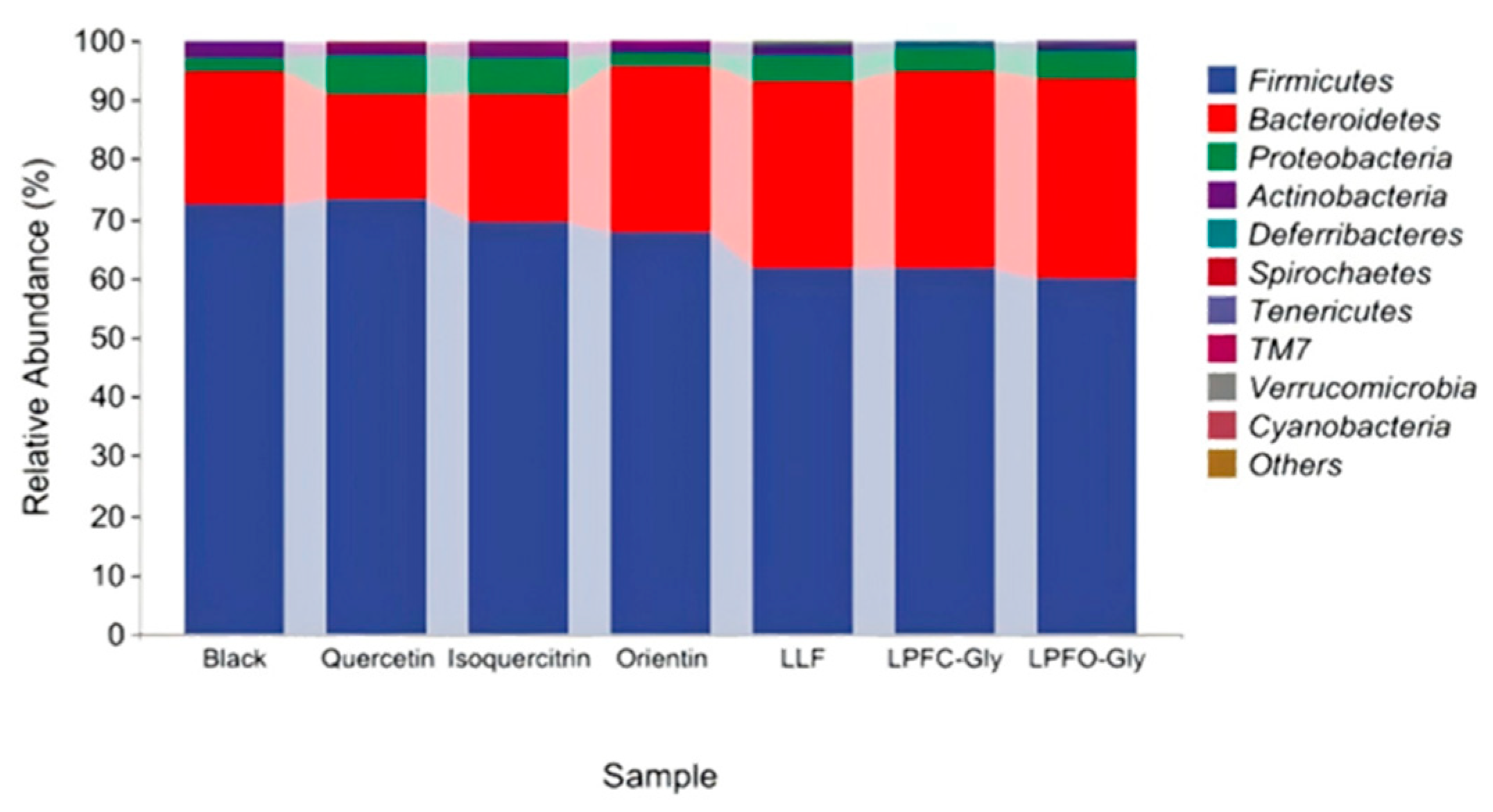

3.6.2. Effects of O- Flavonoids and C-Glycosides on Intestinal Flora in Rats

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang M, Shen Q, Hu L, et al. Physicochemical Properties, Structure and in Vitro Digestibility on Complex of Starch with Lotus (nelumbo Nucifera Gaertn.) Leaf Flavonoids[J]. Food Hydrocolloids, 2018,81:191-199. [CrossRef]

- Xiao J, Capanoglu E, Jassbi A R, et al. Advance on the Flavonoid C-glycosides and Health Benefits[J]. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 2016,56 Suppl 1:S29-S45. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y, Fang J, Zhang Z, et al. Plant flavonoids bioavailability in vivo and mechanisms of benefits on chronic kidney disease: a comprehensive review[J]. Phytochemistry Reviews, 2023,22. [CrossRef]

- Liu S, Li D, Huang B, et al. Inhibition of pancreatic lipase, α-glucosidase, α-amylase, and hypolipidemic effects of the total flavonoids from Nelumbo nucifera leaves[J]. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 2013,149(1):263-269.

- Tian Y, Du H, Qing X, et al. Effects of picking time and drying methods on contents of eight flavonoids and antioxidant activity of leaves of Diospyros lotus L.[J]. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization, 2020,14:1461-1469. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Fan M, Wu J, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of flavonoids from lotus plumule[J]. Food chemistry, 2019,277:706-712. [CrossRef]

- Jomova K, Raptova R, Alomar S Y, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging[J]. Archives of Toxicology, 2023,97:2499-2574.

- Yu Y, Cui Y, Niedernhofer L J, et al. Occurrence, Biological Consequences, and Human Health Relevance of Oxidative Stress-Induced DNA Damage.[J]. CHEMICAL RESEARCH IN TOXICOLOGY, 2016,29:2008-2039. [CrossRef]

- Salehi B, Selamoglu Z, Sevindik M, et al. Achillea spp.: A comprehensive review on its ethnobotany, phytochemistry, phytopharmacology and industrial applications[J]. CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY, 2020,66:78.

- Liu L, Yang L, Zhu M, et al. Machine learning-driven predictive modeling for lipid oxidation stability in emulsions: A smart food safety strategy[J]. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2025,159:104972. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Truong T, Bortolasci C, et al. The potential of baicalin to enhance neuroprotection and mitochondrial function in a human neuronal cell model[J]. BIPOLAR DISORDERS, 2024,26:114. [CrossRef]

- Park H, Yu J. Hesperidin enhances intestinal barrier function in Caco-2 cell monolayers via AMPK-mediated tight junction-related proteins[J]. FEBS OPEN BIO, 2023,13(3):532-544.

- Hu Y, Guan X, He Z, et al. Apigenin-7-O-glucoside alleviates DSS-induced colitis by improving intestinal barrier function and modulating gut microbiota[J]. JOURNAL OF FUNCTIONAL FOODS, 2023,104. [CrossRef]

- Zymone K, Benetis R, Trumbeckas D, et al. Different Effects of Quercetin Glycosides and Quercetin on Kidney Mitochondrial Function-Uncoupling, Cytochrome C Reducing and Antioxidant Activity[J]. MOLECULES, 2022,27(19).

- Jin H, Zhou Y, Ye J, et al. Icariin Improves Glucocorticoid Resistance in a Murine Model of Asthma with Depression Associated with Enhancement of GR Expression and Function[J]. PLANTA MEDICA, 2023,89(03):262-272. [CrossRef]

- Guo D, Huang H, Liu H, et al. Orientin Reduces the Effects of Repeated Procedural Neonatal Pain in Adulthood: Network Pharmacology Analysis, Molecular Docking Analysis, and Experimental Validation[J]. PAIN RESEARCH & MANAGEMENT, 2023,2023.

- Dahat Y, Ganguly S, Khan A, et al. Optimizing ultrasonication-assisted comprehensive extraction of bioactive flavonoids from Pterocarpus santalinus leaves using response surface methodology[J]. JOURNAL OF CHROMATOGRAPHY A, 2024,1738. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Zhang H, Jiang P, et al. Isoliquiritin counteracts cadmium-induced intestinal damage in mice through enhancing intestinal barrier function and inhibiting apoptosis[J]. FOOD AND CHEMICAL TOXICOLOGY, 2024,186. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Su T, Sun Q, et al. Ultrahigh pressure enhances the extraction efficiency, antioxidant potential, and hypoglycemic activity of flavonoids from Chinese sea buckthorn leaves[J]. LWT-FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, 2024,207.

- Nicolescu A, Babota M, Canada E A, et al. Association of enzymatic and optimized ultrasound-assisted aqueous extraction of flavonoid glycosides from dried Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Sea Buckthorn) berries[J]. ULTRASONICS SONOCHEMISTRY, 2024,108. [CrossRef]

- Miksovsky P, Kornpointner C, Parandeh Z, et al. Enzyme-Assisted Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Flavonoids from Apple Pomace (Malusxdomestica)[J]. CHEMSUSCHEM, 2024,17(7).

- Martínez-Las Heras R, Pinazo A, Heredia A, et al. Evaluation studies of persimmon plant (Diospyros kaki) for physiological benefits and bioaccessibility of antioxidants by in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion[J]. Food chemistry, 2017,214:478-485. [CrossRef]

- Zyzynska-Granica B, Gierlikowska B, Parzonko A, et al. The Bioactivity of Flavonoid Glucuronides and Free Aglycones in the Context of Their Absorption, II Phase Metabolism and Deconjugation at the Inflammation Site.[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2019,135:110929. [CrossRef]

- Bohn T, Carriere F, Day L, et al. Correlation between in vitro and in vivo data on food digestion. What can we predict with static in vitro digestion models?[J]. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 2018,58(13):2239-2261. [CrossRef]

- Lucas-González R, Viuda-Martos M, Álvarez J A P, et al. Changes in bioaccessibility, polyphenol profile and antioxidant potential of flours obtained from persimmon fruit (Diospyros kaki) co-products during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion[J]. Food chemistry, 2018,256:252-258. [CrossRef]

- Minekus M, Alminger M, Alvito P, et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food–an international consensus[J]. Food & function, 2014,5(6):1113-1124.

- Qin Y, Zhang Y, Chen X, et al. Synergistic effect of pectin and the flavanols mixture on in vitro starch digestion and the corresponding mechanism[J]. FOOD HYDROCOLLOIDS, 2025,158. [CrossRef]

- LI Z, CAI H, LIANG Y, et al. Effect of Xanthan Gum on Bioaccessibility of Four Bamboo Leaf Flavonoids during Simulated in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion[J]. Food Science, 2019,40:58-64.

- Thilakarathna S H, Rupasinghe H V. Flavonoid bioavailability and attempts for bioavailability enhancement[J]. Nutrients, 2013,5(9):3367-3387.

- Brodkorb A, Egger L, Alminger M, et al. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion[J]. Nat Protoc, 2019,14(4):991-1014. [CrossRef]

- Mulet-Cabero A, Egger L, Portmann R, et al. A standardised semi-dynamic in vitro digestion method suitable for food–an international consensus[J]. Food & function, 2020,11(2):1702-1720.

- Zeng Y, Song J, Zhang M, et al. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of six flavonoids with similar structures[J]. Antioxidants, 2020,9(8):732. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Yang Y, Gao J, et al. Phenolics and antioxidant activity of bamboo leaves soup as affected by in vitro digestion[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2020,135:110941. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Wu J, Chen L, et al. Biogenesis of C-glycosyl flavones and profiling of flavonoid glycosides in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera)[J]. PLoS One, 2014,9(10):e108860. [CrossRef]

- Zhu M Z, Wu W, Jiao L L, et al. Analysis of Flavonoids in Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) Leaves and Their Antioxidant Activity Using Macroporous Resin Chromatography Coupled with LC-MS/MS and Antioxidant Biochemical Assays[J]. Molecules, 2015,20(6):10553-10565.

- Liu B, Li J, Yi R, et al. Preventive effect of alkaloids from Lotus plumule on acute liver injury in mice[J]. Foods, 2019,8(1):36. [CrossRef]

- Liu T, Zhu M, Zhang C, et al. Quantitative analysis and comparison of flavonoids in lotus plumules of four representative lotus cultivars[J]. Journal of Spectroscopy, 2017,2017(1):7124354. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, Tian W, Yang C, et al. Identification of flavonoids in Plumula nelumbinis and evaluation of their antioxidant properties from different habitats[J]. Industrial Crops and Products, 2019,127:36-45. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Zhao H, Cheng N, et al. Rape bee pollen alleviates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis by neutralizing IL-1β and regulating the gut microbiota in mice[J]. Food research international, 2019,122:241-251. [CrossRef]

- Valentová K, Vrba J, Bancířová M, et al. Isoquercitrin: Pharmacology, toxicology, and metabolism[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2014,68:267-282.

- Xie L, Deng Z, Zhang J, et al. Comparison of Flavonoid O-Glycoside, C-Glycoside and Their Aglycones on Antioxidant Capacity and Metabolism during In Vitro Digestion and In Vivo: Foods[Z]. 2022: 11.

- Xu G, Zhong X, Wang Y, et al. An approach to detecting species diversity of microfaunas in colonization surveys for marine bioassessment based on rarefaction curves[J]. Marine pollution bulletin, 2014,88(1-2):268-274. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta A, Dick W A. Bacterial community diversity in soil under two tillage practices as determined by pyrosequencing[J]. Microbial ecology, 2015,70:853-859.

- Zhao L, Zhang Q, Ma W, et al. A combination of quercetin and resveratrol reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed rats by modulation of gut microbiota[J]. Food & function, 2017,8(12):4644-4656. [CrossRef]

| Main Constituent | Concentration | SSF pH 7 |

SGF pH 3 |

SIF pH 7 |

||||

| Volume | Concentration | Volume | Concentration | Volume | Concentration | |||

| g L-1 | Mol L-1 | mL | mmolL-1 | mL | mmolL-1 | mL | mmolL-1 | |

| NaCl | 117 | 2 | — | — | 11.8 | 47.2 | 9.6 | 38.4 |

| NaHCO3 | 84 | 1 | 6.8 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 25 | 42.5 | 85 |

| KCl | 37.3 | 0.5 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

| KH2PO4 | 68 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| (NH4)2CO3 | 48 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.5 | — | — |

| MgCl2(H2O)6 | 30.5 | 0.15 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.33 |

| pH regulating solution | ||||||||

| molL-1 | mL | mmolL-1 | mL | mmolL-1 | mL | mmolL-1 | ||

| HCl | 6 | 0.09 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 15.6 | 0.7 | 8.4 | |

| NaOH | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Add CaCl2(H2O)2again in the digestion stage | ||||||||

| gL-1 | molL-1 | mmolL-1 | mmolL-1 | mmolL-1 | ||||

| CaCl2(H2O)2 | 44.1 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.15 | 0.6 | |||

| NO | RT(min) | NI-MS | MS/MS | Identification | Ref |

| 1 | 17.991 | 595 | 300 | Quercetin 3-O-arabinopyranosyl-(1→2)-galactopyranoside | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 2 | 19.733 | 609 | 300 | Quercetin 3-O-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-glucopyranoside | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 3 | 20.980 | 463 | 300 | Hyperoside | Standard |

| 4 | 21.580 | 463 | 300 | Isoquercitrin | Standard |

| 5 | 22.388 | 477 | 301 | Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | Standard |

| 6 | 26.787 | 447 | 284 | Kaempferol 3-O-galactoside | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 7 | 27.239 | 447 | 284 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside (astragalin) | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 8 | 27.988 | 461 | 285 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 9 | 28.112 | 461 | 298 | Diosmetin 7-O-hexose | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 10 | 29.999 | 609 | 314, 299 | Isorhamnetin3-O-arabinopyranosyl-(1→2)-glucopyranoside | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 11 | 30.909 | 477 | 314 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-hexose | zhu et al., 2015 |

| 12 | 32.436 | 491 | 315 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-glucuronide | zhu et al., 2015 |

| NO | RT (min) | NI-MS | MS/MS | Identification | Ref |

| 1 | 18.457 | 579 | 519, 489, 459, 399, 369 | Luteolin6-C-pentoside-8-C-glucoside | Li et al. (2014) |

| 2 | 19.648 | 593 | 575, 533, 503, 473, 383, 353 | Chrysoeriol (Diosmetin)6-C-pentoside (hexoside)-8-C-hexoside | Ferreres et al. (2003) |

| 3 | 20.276 | 579 | 519, 489 | Luteolin6-C- glucoside -8-C- pentoside | Li et al. (2014) |

| 4 | 20.815 | 563 | 503, 473, 443, 425, 383, 353 | Apigenin 6-C-glucoside-8-C-xylosidase | Liu et al. (2017) |

| 5 | 22.968 | 563 | 503, 473 | Apigenin-6-C-xylosidase-8-C-glucoside | Liu et al. (2017) |

| 6 | 24.795 | 563 | 473, 443, 383, 353 | Apigenin 6-C-glucosyl-8-C-arabinoside(Schaftoside) | Standard |

| 7 | 25.317 | 447 | 327, 297 | Luteolin-6-C-glucoside (isoorientin) | Standard |

| 8 | 26.983 | 447 | 357, 327, 297 | Luteolin-8-C-glucoside (orientin) | Standard |

| 9 | 27.436 | 563 | 503, 473, 443, 383, 353 | Apigenin-6-C-arabinosyl-8-C-glucoside (isoschaftoside) | zheng et al. (2019) |

| 10 | 29.263 | 577 | 503, 487, 457, 383, 353 | Apigenin-6-C-glucosyl-8-C-rhamnoside | Li et al. (2014) |

| 11 | 29.689 | 609 | 300, 271 | Rutin | zhu et al. (2017) |

| 12 | 30.540 | 577 | 457, 383, 353 | Apigenin-6-C-rhamnoside-8-C-glucosyl | Li et al. (2014) |

| 13 | 30.731 | 593 | 447, 285 | Luteolin-7-O-neohesperidoside | Liu et al. (2017) |

| 14 | 31.077 | 463 | 300 | Quercetin3-O-glucoside(Isoquercitrin) | zhu et al. (2017) |

| 15 | 32.013 | 593 | 285 | Luteolin-7-O-rutinoside | Liu et al. (2017) |

| 16 | 32.290 | 623 | 315 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | Liu et al. (2017) |

| 17 | 33.199 | 607 | 299, 284 | Diosmetin 7-O-rutinoside (Diosmin) | zhu et al. (2017) |

| LFF | Content(mg/g) | LPF O-Gly | Content(mg/g) | LPF C-Gly | Content(mg/g) |

| Qu 3-ara (1→2) gal | 59.17±16.01 | Ru | 158.12±19.11 | Lu 6-pen-8-glu | 13.31±0.92 |

| Qu 3-rha (1→2) glu | 19.88±3.3 | Lu 7-neo | 71.46±15.99 | Chr 6-pen-8-hex | 29.55±2.63 |

| IQ | 29.39±9.61 | IQ | 62.57±13.67 | Lu 6-glu-8-pen | 21.42±2.41 |

| Qu 3-glu | 611.98±138.92 | Lu 7-rut | 28.24±2.64 | Ap 6-glu-8-xyl | 13.12±1.86 |

| Ka 3-gal | 22.25±2.96 | Iso 3-rut | 41.37±3.77 | Ap 6-xyl-8-glu | 45.56±3.79 |

| Ka 3-glu | 21.49±0.72 | Dio 7-rut | 21.40±2.89 | Sc | 92.65±0.45 |

| Ka 3-gln | 15.76±1.51 | Ior | 144.23±5.27 | ||

| Iso 3-gln | 18.88±4.96 | Or | 23.85±5.73 | ||

| Isc | 45.12±0.86 | ||||

| Ap 6-glu-8-rha | 45.48±6.16 | ||||

| Total | 798.81±86.53 | 383.17±31.65 | 474.29±74.57 |

| Compound | Phase (Content mg/g) | |||

| Firsthand | Oral cavity | Stomach | Intestinum | |

| Qu 3-ara (1→2) gal | 59.17±16.01a | 40.75±3.04a | 11.50±0.33b | 15.19±5.04b |

| Qu 3-rha (1→2) glu | 19.88±3.3a | 14.62±0.65b | 14.98±2.31b | 13.27±0.90b |

| IQ | 29.39±9.61a | 25.52±1.46ab | 21.55±2.04bc | 13.62±1.29c |

| Qu 3-glu | 611.98±138.92a | 360.75±32.87b | 327.86±29.66b | 221.87±4.55b |

| Ka 3-gal | 22.25±2.96a | 14.96±1.23b | 12.36±0.90b | 12.56±0.32b |

| Ka 3-glu | 21.49±0.72a | 17.59±0.44b | 13.93±1.08c | 11.57±0.30d |

| Ka 3-gln | 15.76±1.51a | 11.50±0.21b | 12.33±0.30b | 11.45±0.51b |

| Iso 3-gln | 18.88±4.96a | 15.36±0.31ab | 13.72±0.05ab | 12.20±0.30b |

| Qu | 0.00 | ND | 4.27±1.37 | 9.48±2.16 |

| Total | 798.81±86.53a | 500.85±2.89b | 427.22±33.76c | 311.73±2.45d |

| Compound | Phase (Content mg/g) | |||

| Firsthand | Oral cavity | Stomach | Intestinum | |

| Rut | 158.12±19.11a | 72.62±0.58b | 57.42±0.28b | 52.99±4.39b |

| Lu 7-neo | 71.46±15.99a | 67.93±0.32ab | 50.43±2.44bc | 42.37±2.39c |

| IQ | 62.57±13.67a | 36.74±0.27b | 31.02±0.085b | 23.70±2.41b |

| Lu 7-rut | 28.24±2.64a | 20.21±4.29b | 19.30±0.85b | 18.22±1.16b |

| Iso 3-rut | 41.37±3.77a | 29.72±0.26b | 26.44±1.12bc | 23.31±2.07c |

| Dio 7-rut | 21.40±2.89a | 16.14±2.06ab | 18.21±0.59bc | 13.02±0.74c |

| Qu | 0.00 | ND | 1.41±0.22 | ND |

| Total | 383.17±31.65 | 243.36±1.60b | 202.82±3.44c | 173.61±9.30d |

| Compound | Phase (Content mg/g) | |||

| Firsthand | Oral cavity | Stomach | Intestinum | |

| Lu 6-pen-8-glu | 13.31±0.92a | 11.58±1.05a | 11.60±0.01a | 11.16±0.24a |

| Chr 6-pen-8-hex | 29.55±2.63a | 22.98±5.43b | 23.47±1.10b | 23.50±2.12b |

| Lu 6-glu-8-pen | 21.42±2.41a | 15.56±4.95b | 13.83±1.54b | 15.18±3.2b |

| Ap 6-glu-8-xyl | 13.12±1.86a | 11.41±1.28b | 11.12±0.4b | 11.93±0.32b |

| Ap 6-xyl-8-glu | 45.56±3.79a | 34.92±9.00b | 34.05±2.58b | 33.64±5.64b |

| Sc | 92.65±0.45a | 77.53±27.78b | 75.31±7.24b | 75.40±13.45b |

| Ior | 144.23±5.27a | 101.54±30.27b | 90.72±7.50b | 93.16±13.37b |

| Or | 23.85±5.73a | 17.90±1.41b | 18.04±0.78b | 17.87±1.92b |

| Isc | 45.12±0.86a | 31.24±10.92b | 33.38±1.59b | 33.02±6.26b |

| Ap 6-glu-8-rha | 45.48±6.16a | 33.89±8.23b | 30.85±0.87b | 31.54±5.91b |

| Total | 474.29±74.57a | 358.56±26.44b | 344.53±18.70c | 346.40±40.54c |

| Compound | Phase (Content mg/g) | ||||

| 0h | 6h | 12h | 24h | 48h | |

| Qu 3- ara (1→2) gal | 32.76±6.32a | 28.27±4.65ab | 17.55±3.36b | 17.27±6.32b | 10.60±3.03c |

| Qu 3- rha (1→2) glu | 9.84±2.01 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| IQ | 16.77±3.02a | 12.12±1.20ab | 4.54±0.63c | 6.83±2.31c | 3.67±1.21cd |

| Qu 3-glu | 282.23±32.36a | 139.56±14.56b | 72.97±6.99c | 94.77±5.21c | 9.88±2.51d |

| Ka 3-gal | 10.68±2.14a | 9.82±1.58a | 2.28±0.45b | 2.40±1.01b | 2.68±0.59b |

| Ka 3-glu | 12.38±1.59a | 9.80±3.26ab | 2.11±0.65c | 2.98±0.84c | 4.30±1.24c |

| Ka 3-gln | 11.20±1.58a | 10.09±2.12a | 3.56±1.11b | 2.21±0.54b | 3.63±0.87b |

| Iso 3-gln | 14.17±2.55a | 10.15±1.24ab | 2.57±0.57c | 2.62±0.08c | 1.99±0.04c |

| Qu | 3.26±0.24c | 3.91±0.84c | 29.53±2.45b | 41.87±5.98ab | 30.73±5.21ab |

| Total | 390.03±26.34a | 219.81±15.94b | 105.58±8.98c | 128.98±15.45c | 36.75±5.65d |

| Compound | Phase (Content mg/g) | ||||

| 0h | 6h | 12h | 24h | 48h | |

| Rut | 106.23±14.84a | 73.00±4.57b | 62.013±5.24b | 68.68±6.87b | 22.62±2.48c |

| Lu 7-neo | 56.67±6.54a | 49.64±6.87ab | 34.54±4.77c | 32.12±4.54c | 14.57±3.21d |

| IQ | 59.46±6.57a | 41.44±3.54b | 29.89±3.65bc | 27.59±4.14bc | 11.62±2.51d |

| Lu 7-rut | 20.09±3.21a | 13.87±2.21b | 10.46±1.39b | 11.21±2.24b | 2.68±0.59c |

| Iso 3-rut | 31.71±3.54a | 22.92±2.24ab | 17.49±4.55bc | 18.97±3.66bc | 4.54±1.21d |

| Dio 7-rut | 14.84±2.34a | 6.64±2.21b | 1.84±0.54c | 1.48±0.05c | ND |

| Qu | 1.73±0.14c | 3.70±1.14c | 11.86±2.21bc | 11.64±1.14bc | 14.41±2.57a |

| Total | 289.00±14.51a | 207.51±9.87ab | 156.233±6.54bc | 160.05±8.84bc | 56.03±4.89d |

| Compound | Phase (Content mg/g) | ||||

| 0h | 6h | 12h | 24h | 48h | |

| Lu 6-pen-8-glu | 5.51±2.14a | 5.15±1.24a | 3.38±1.47ab | 3.08±1.54ab | 2.39±0.47bc |

| Chr 6-pen-8-hex | 18.94±5.47a | 19.59±5.47a | 20.029±4.14a | 14.88±3.44b | 16.74±4.47ab |

| Lu 6-glu-8-pen | 9.12±2.47a | 10.41±3.24a | 8.94±2.14ab | 9.03±2.44a | 6.37±2.54bc |

| Ap 6-glu-8-xyl | 8.88±2.45a | 10.55±2.55a | 9.48±2.41a | 7.26±1.47ab | 7.24±.31ab |

| Ap 6-xyl-8-glu | 29.70±6.87a | 29.44±6.54a | 26.80±4.87a | 23.64±4.58ab | 20.41±6.57bc |

| Sc | 59.50±10.54a | 59.80±11.23a | 64.46±12.14a | 56.21±10.24ab | 57.91±9.87ab |

| Ior | 92.37±15.15a | 82.97±11.21ab | 86.60±9.23ab | 98.11±14.55a | 92.55±11.25a |

| Or | 12.029±2.34a | 11.20±3.21a | 10.28±3.54a | 8.78±2.69a | 10.70±3.51a |

| Isc | 28.79±6.55ab | 32.71±3.65a | 32.27±5.47a | 28.97±6.88ab | 26.54±7.21ab |

| Ap 6-glu-8-rha | 23.42±7.27a | 20.50±5.66a | 20.33±6.36a | 20.58±4.14a | 16.25±4.57b |

| Total | 288.26±21.54a | 282.32±24.31a | 262.27±21.9c | 270.54±17.4b | 257.10±15.48c |

| NO | tR/min | [M-H]- /[M+H]+ |

PPM | Fragment ions (m/z) |

Mode | Formula | Transformations | Location | |

| P | U | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.195 | 477.066 | 1.41 | 301.034 151.002 |

Neg | C21H18O13 | Glucuronide Conjugation | - | + |

| 2 | 1.236 | 318.073 | -0.12 | Neg | C16H14O7 | Reduction, Methylation |

+ | - | |

| 3 | 1.336 | 491.082 | -1.63 | 315.050 151.002 |

Neg | C21H16O14 | Methylation | - | + |

| 4 | 6.286 | 653.098 | -1.87 | 477.0666 301.034 |

Neg | C27H26O19 | Glucuronide Conjugation | - | + |

| 5 | 6.299 | 653.098 | -0.85 | 477.066 301.034 |

Neg | C21H18O13 | Glucuronide Conjugation | - | + |

| 6 | 7.092 | 301.030 | -0.97 | 153.017 | Pos | C15H8O7 | Dehydration, Reduction, Methylation | - | + |

| 7 | 7.220 | 301.070 | -1.29 | 153.017 | Pos | C15H8O7 | Dehydration, Reduction, Methylation | - | + |

| 8 | 8.298 | 315.051 | -2.60 | 300.027 151.002 |

Neg | C16H12O7 | Methylation | - | + |

| 9 | 11.007 | 315.050 | -1.05 | 300.027 151.002 |

Neg | C16H12O7 | Methylation | + | |

| 10 | 11.762 | 315.050 | -4.18 | 300.026 151.002 |

Neg | C16H12O7 | Methylation | - | + |

| 11 | 14.374 | 313.237 | -0.12 | Neg | C15H6O8 | Desatyration, Methylation | - | + | |

| 12 | 14.417 | 315.253 | -0.34 | 300.027 | Neg | C16H12O7 | Methylation | - | + |

| 13 | 16.088 | 315.253 | -1.07 | 300.026 | Neg | C16H8O7 | Methylation | + | + |

| 14 | 18.198 | 315.050 | -1.37 | 300.027, 151.002 |

Neg | C16H8O7 | Methylation | + | + |

| 15 | 19.139 | 315.253 | -1.16 | 300.027 | Neg | C16H10O8 | Methylation | + | + |

| 16 | 32.294 | 315.050 | -1.98 | 300.027 151.002 |

Neg | C21H20O12 | Methylation | - | + |

| NO | tR/min | [M-H]- /[M+H]+ |

PPM | Fragment ions (m/z) |

Mode | Formula | Transformations | Location | |

| P | U | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.325 | 145.049 | -0.88 | Neg | C6H8O4 | Hydration, Desaturation |

- | + | |

| 2 | 1.432 | 195.050 | -3.99 | Neg | C17H14O10 | Dioxidation, | - | + | |

| 3 | 4.197 | 187.006 | -4.94 | Neg | C8H12O7 | Dehydration, Acetylation |

- | + | |

| 4 | 4.797 | 129.054 | -0.40 | Neg | C6H8O3 | Didehydration | - | + | |

| 5 | 5.935 | 461.072 | -1.07 | 151.002 | Neg | C21H18O12 | Desaturation, Glucuronide Conjugation |

+ | - |

| 6 | 8.619 | 301.069 | -1.09 | 153.017 | Pos | C16H12O8 | Dehydration, Reduction, Methylation | - | + |

| 7 | 8.717 | 285.039 | -1.16 | 151.110 | Neg | C21H18O11 | Dehydration, Reduction, |

- | + |

| 8 | 8.989 | 307.118 | -2.78 | Neg | C12H20O9 | Dehydration, Glucoside Conjugation | - | + | |

| 9 | 14.797 | 315.253 | -1.16 | 300.027 | Neg | C16H12O6 | Methylation | + | |

| 10 | 15.238 | 477.277 | -0.77 | 151.075 | Neg | C21H18O13 | Glucuronide Conjugation | - | + |

| 11 | 16.747 | 315.253 | -0.78 | 300.026 | Neg | C16H12O6 | Methylation, | - | - |

| 12 | 29.685 | 311.108 | -0.19 | Neg | C16H8O7 | Didesaturation, Methylation |

- | + | |

| 13 | 30.535 | 286.047 | -1.80 | Neg | C15H10O6 | Dehydration, Reduction |

- | + | |

| NO | tR/min | [M-H]- /[M+H]+ |

PPM | Fragment ions (m/z) |

Mode | Formula | Transformations | Location | |

| P | U | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.144 | 563.147 | -0.59 | 503.309 | Neg | C26H8O14 | - | + | |

| 2 | 1.801 | 563.147 | -1.63 | 503.309 | Neg | C26H8O14 | - | + | |

| 3 | 1.823 | 447.092 | -2.30 | 357.736 | Neg | C21H20O11 | + | ||

| 4 | 1.981 | 563.147 | 4.02 | 503.309 | Neg | C26H8O14 | - | + | |

| 5 | 1.994 | 447.106 | -4.19 | 357.736 | Neg | C22H22O10 | + | - | |

| 6 | 2.329 | 445.253 | -1.49 | 357.736 | Neg | C22H22O10 | Dehydration, Reduction, Methylation |

+ | - |

| 7 | 29.947 | 491.119 | -0.61 | Neg | C23H24O12 | Reduction, Acetylation |

+ | - | |

| 8 | 30.281 | 491.119 | -0.42 | Neg | C23H24O12 | Reduction, Acetylation |

+ | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).