1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) is a well-accepted and widely utilized method for producing diverse components, prototypes, and parts, as well as customized tools and accessories through a layer-by-layer construction process. AM is constantly evolving to expand and find its place in as many possible different industrial sectors including AEC (Architecture-Engineering-Construction) [

1]. One of the most significant advantages of this method is the relatively fast production of geometrically complex parts which is even more actual if serial production is not required [

2].

Metal threads are utilized for joining materials in a variety of industries, including metal structures, shipbuilding, automobiles, electronics, aircraft, and defense. Its application is increasing, especially when rapid construction and disassembly of pieces is required [

3]. There is an absence of thorough studies analyzing the quality of metal inserts used in AM-produced plastic parts. Such joints are essential because their quality influences the final product's intended purpose. This is particularly valid when it comes to joining larger products. Today, the industry has simply embraced metal and plastic joints during the assembly process, which demands rapid connection of smaller pieces [

4]. The maximal pull-out force is a widely accepted criterion for quantifying the quality of the joint between metal insert and plastic. During testing, the force required to pull the threaded insert out of the plastic is continually measured. Generally, this is still not a standardized method even though this force can be measured on standard pull-out or tensile test devices. This means that researchers do not always employ the same preset parameters throughout testing, such as loading speed and sample dimensions [

5].

Several methods (insert molding, thermal, cold and ultrasonic insertion) are available for joining thermoplastic material with metal insert [

6,

7]. Amancio et. al. [

8] have analyzed three techniques for joining polymers and their composites: mechanical fastening (screws or rivets), adhesive bonding, and welding (melting the materials to form a joint). Each of these techniques has its advantages and disadvantages. Namely, mechanical joining has certain difficulties due to the different physical and chemical properties of metals and polymers (thermal expansion, surface energy, and mechanical strength). Besides the characteristics of the materials used for joining have a huge impact on the durability and design of final products. Metal inserts (or threatened inserts) offer better qualities than printed parts in which they are embedded, particularly those related to stress-strain relationships.

Heat stuck is a commonly used technique for joining metal and printed plastic. The main advantage of this method is that the joining process does not require drilling that additionally affects the mechanical properties of the plastic parts obtained by AM [

3]. During embedding the softened plastic adheres to the outer surface of the insert. This process can be realized by different procedures [

9]. The strength of the joint is greatly influenced by the joining technology, the geometry of the insert and preset printing parameters, for example specified number of top and bottom layers and wall line contours [

10]. The strongest connections are made by directly sinking metal threaded inserts into the plastic [

5]. Recently Fürst et al. [

11] have presented an innovative procedure, in which heat input is delivered via outer thread flanks during application. This method can increase the overall strength of the joint compared to the standard heat stuck procedure. Miklavec et. al. [

12] have used different forms of metal inserts to improve the mechanical characteristics of the hybrid joint. Results have confirmed that the design of metal inserts, especially its outside surface is a very important parameter for ensuring better polymer bonding to the metal which consequently leads to the increase of its strength and corrosion resistance. Furthermore, the folds on the outside of the metal inserts have a direct impact on pullout resistance and torque [

13]. An investigation into the possibilities of enhancing the stiffness and mechanical strength of the composite carbon fiber reinforced plastic is another example of how the geometry and form of the metal insert impact the joint [

14]. An additional bed patterns were added to the metal sheet of the insert. This technology significantly increased the performance of composite products, particularly their load-bearing capability. Thereby composite components can be linked with other materials more readily and robustly. The influence of printing parameters on the quality of the joint between the insert and plastic was reported in the study by Kastner et al. [

15]. It was found that infill density has a significant effect on the joint strength. A direct relation between infill density and the pulling force was registered. Optimal printing preset was also reported. Recommended infill density, wall thickness, layer height and print temperature were set to 70%, 1.2 mm, 0.2 mm, and 225°C. When it comes to sandwich panels, the performance of inserts subjected to pulling forces was also investigated. For example, Seeman et al. employed numerical models to predict pull-out strength [

16], whereas Stefan et al. experimentally investigated the mechanical properties of panels with inserted metal joints under various loading conditions [

17].

Degradation is commonly seen as the deleterious distortion of the material: surface appearance (color change), chemical structure, or physical properties. In the polymer case, degradation occurs as a result of macromolecule chemical cleavage. Various mechanisms (photo-oxidative, thermo-oxidative, ozone-induced, mechanochemical, hydrolytic, freeze-thaw and biodegradation) which can act separately or simultaneously are causing the polymer chain scission. Besides, polymer aging is commonly seen as the gradual degradation of material over time caused by environmental factors such as heat, moisture, oxygen exposure, light (UV radiation) or mechanical stress [18-20]. Accelerated aging refers to any artificial procedure that increases one or more variables affecting the material's natural decay. The primary goal is to simulate the long-term effects of environmental conditions in a shorter time frame. Orellana-Barrasa et al. [

21] have aged PLA in a temperature range from 20 to 80°C. It was found that PLA can be safely aged without degrading at 39°C. Vorkapić et al. [

22] have studied the impact of temperature aging at 57°C on the tensile properties of PLA printed samples. It was found that with aging the mechanical properties are decreasing. This is more pronounced for samples printed with higher layer height. Products with 0/90[°] orientation were mostly brittle while those printed using -45/45[°] orientation withstood the highest deformations before failure. The impact of UV radiation on PLA samples can be found for example in references [23-25]. References [

25,

26] described PLA weathering tests utilizing the methodology that included two (humidity and temperature) and three (humidity, temperature, and UV) aging agents. The main finding was that mechanical properties were lower for samples aged at maximal relative humidity content.

Standards ISO 2578, ISO 176, and ASTM D1203 are used for determining heat stability and formulating long-term predictions about polymers. Heat distortion of polymers is described in ASTM D648. The problem is that most standards for assessing polymer weathering degradation are limited to a particular degrading agent, such as ASTM D1435, D1499, D2565, D4329, or D4364. The lack of corresponding ISO or ASTM Cyclic Laboratory Conditions aging standards which include all aging mechanisms is evident. It is important to state that the existing long-term polymer performance assessment is limited and has to be taken with caution, especially when assessing factors are apparent. In such situations, its validity is questionable [

27]. As a result, many aging processes were used in this work, including a novel full cycling method that included four aging parameters (relative humidity, temperature, UV, and IC radiation) at the same time. Furthermore, the effect of artificial aging on the joint between inserts and plastic has not been recorded in literature.

3. Results and discussion

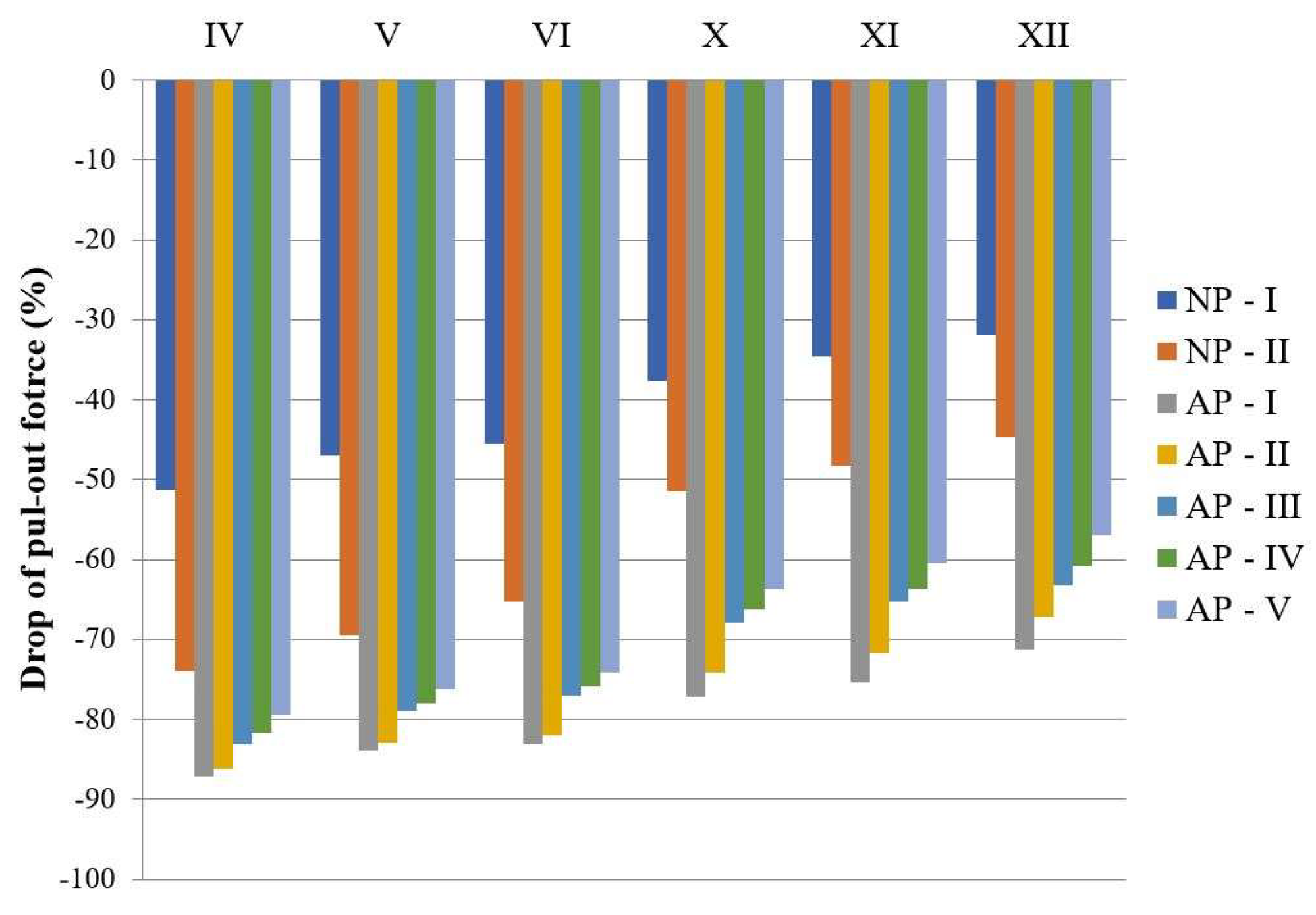

The averaged pull-out force results are summarized in

Table 2.

Figure 8 illustrates the decrease in pull-out force observed after both natural and artificial aging compared to the initial measurements taken before any aging conditions (SP). Both natural and artificial aging significantly decreased the pull-out force. The highest decline is observed in the case of AP-I, which was expected given that this aging protocol comprised temperature cycling, humidity exposure, dry/wet cycle circumstances, combined load, and environmental exposure to UV and IC radiation. Notably, a similar drop in force is observed with AP-II.

The obtained results suggest that the degradation effects caused by freeze-thaw protocols under severe conditions, namely AP-III and AP-IV, are comparable. Additinally, the extreme freeze technique resulted in a stronger pull-out force than any of the severe freeze-thaw methods. However, this "increasing" effect on mechanical properties after extreme exposure was not unexpected, as it was also noted and discussed in our previous study involving PETG samples [

51].

As can be seen in Fig. 8. the pull-out force is in direct correlation with the set printing parameters. As previously stated, its value has consistently increased from samples IV to XII. This pattern was observed for all aging treatments. The nozzle movement during sample realization was visualized using the Ulitmaker Cura software. The output images for samples IV – VI are given in

Figure 9. Samples VI and XII are "stronger" around the hole than samples printed with two or three wall line contours.

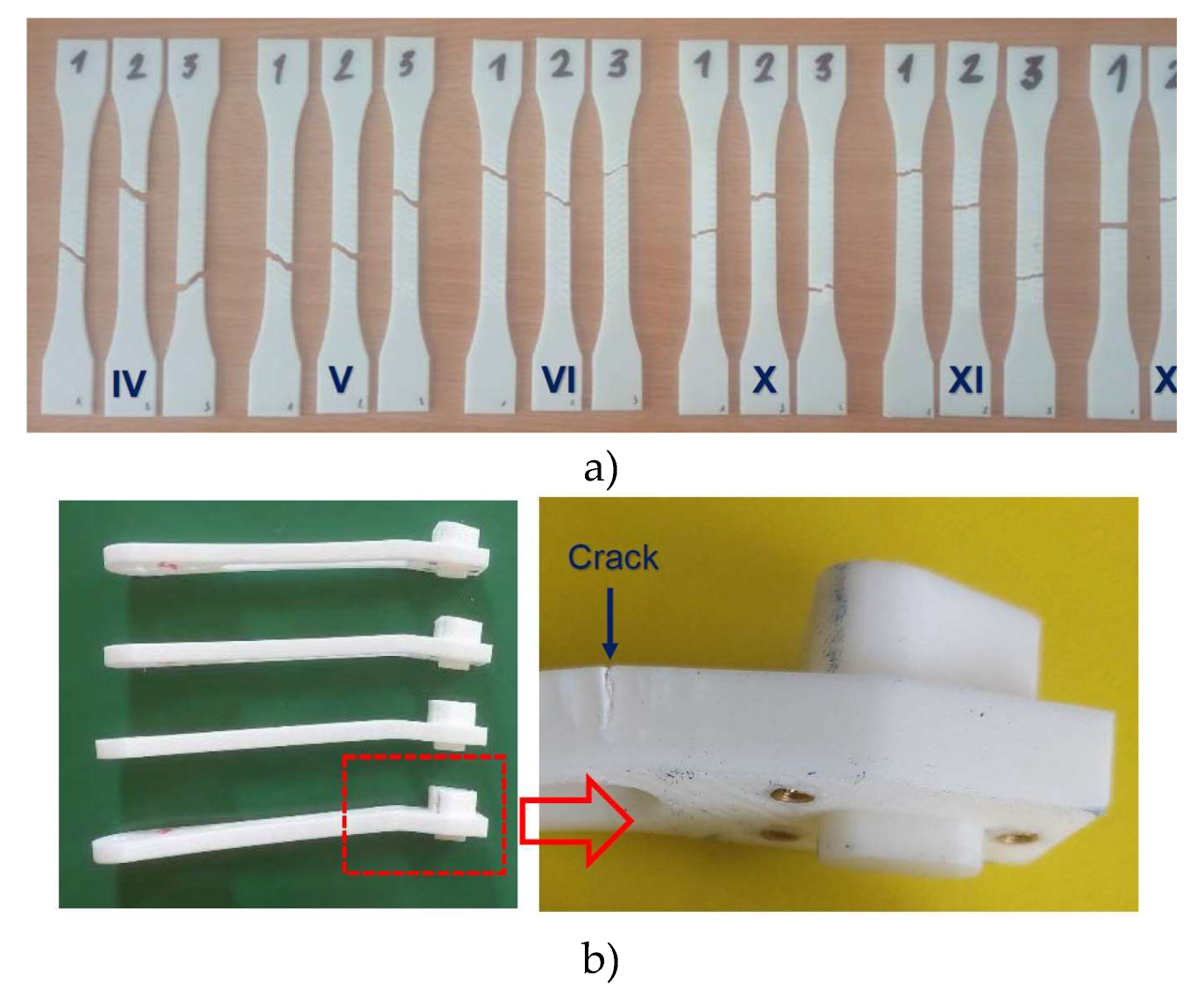

The morphology of the tested samples after the pull-out test for NP-II, AP-III and AP-V is illustrated in

Figure 10. Samples aged under protocol NP-I, AP-I and AP-II have a similar appearance. As can be seen in

Figure 11, AP-IV was the only set where a distinct morphology pattern was observed.

Furthermore, each pull-out metal insert was covered in plastic in this instance as well. In addition, the thickness of the plastic layer around the implant increased from samples IV to VI and from samples X to XII. This is valid proof that the heat stack insertion method was successful. Also, since other printing parameters, such as infill density and infill line direction, were constant in the study it is obvious that the number of wall line contours is responsible for the observed pull-of-force trend. This was also in line with the findings reported in reference [

52].

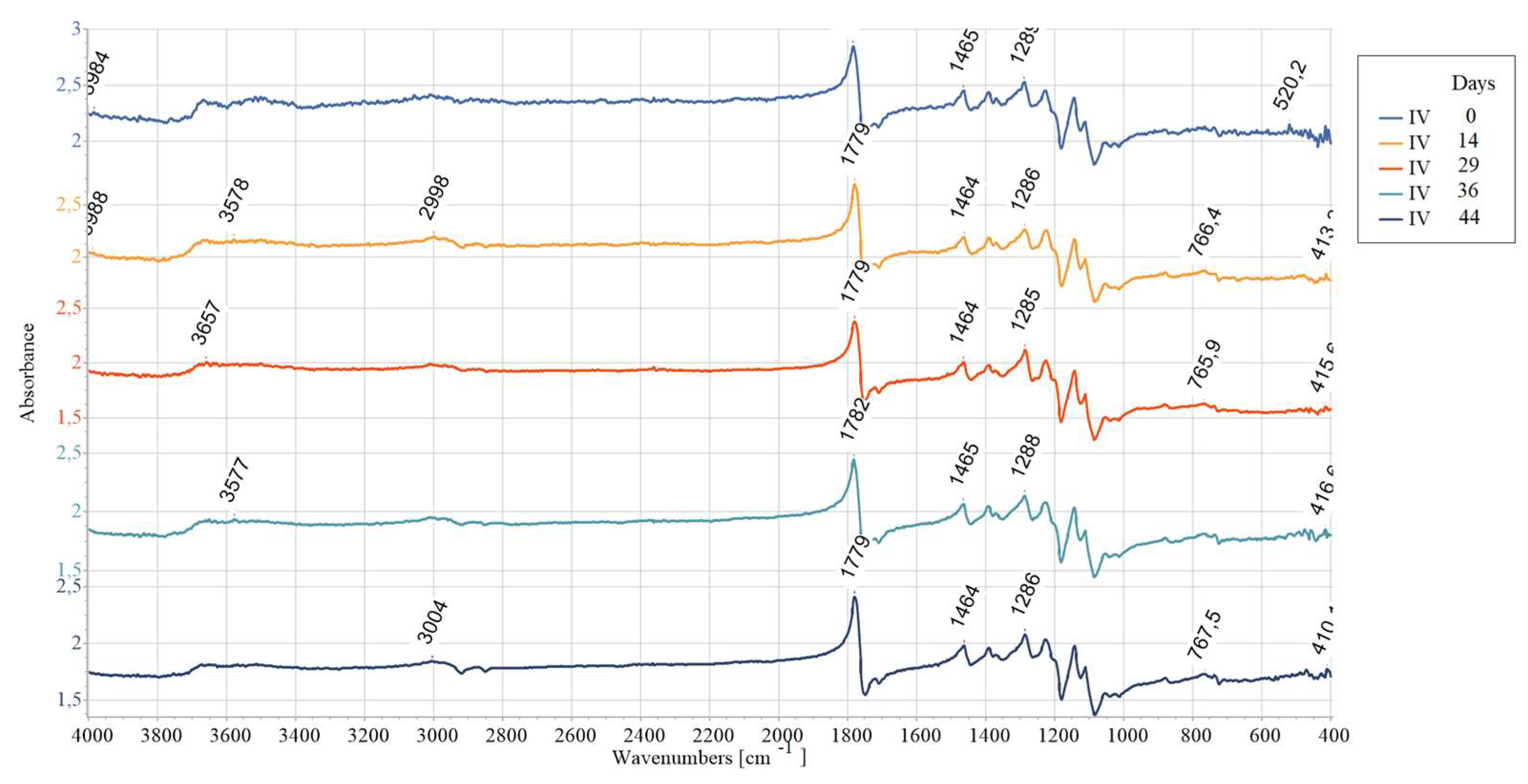

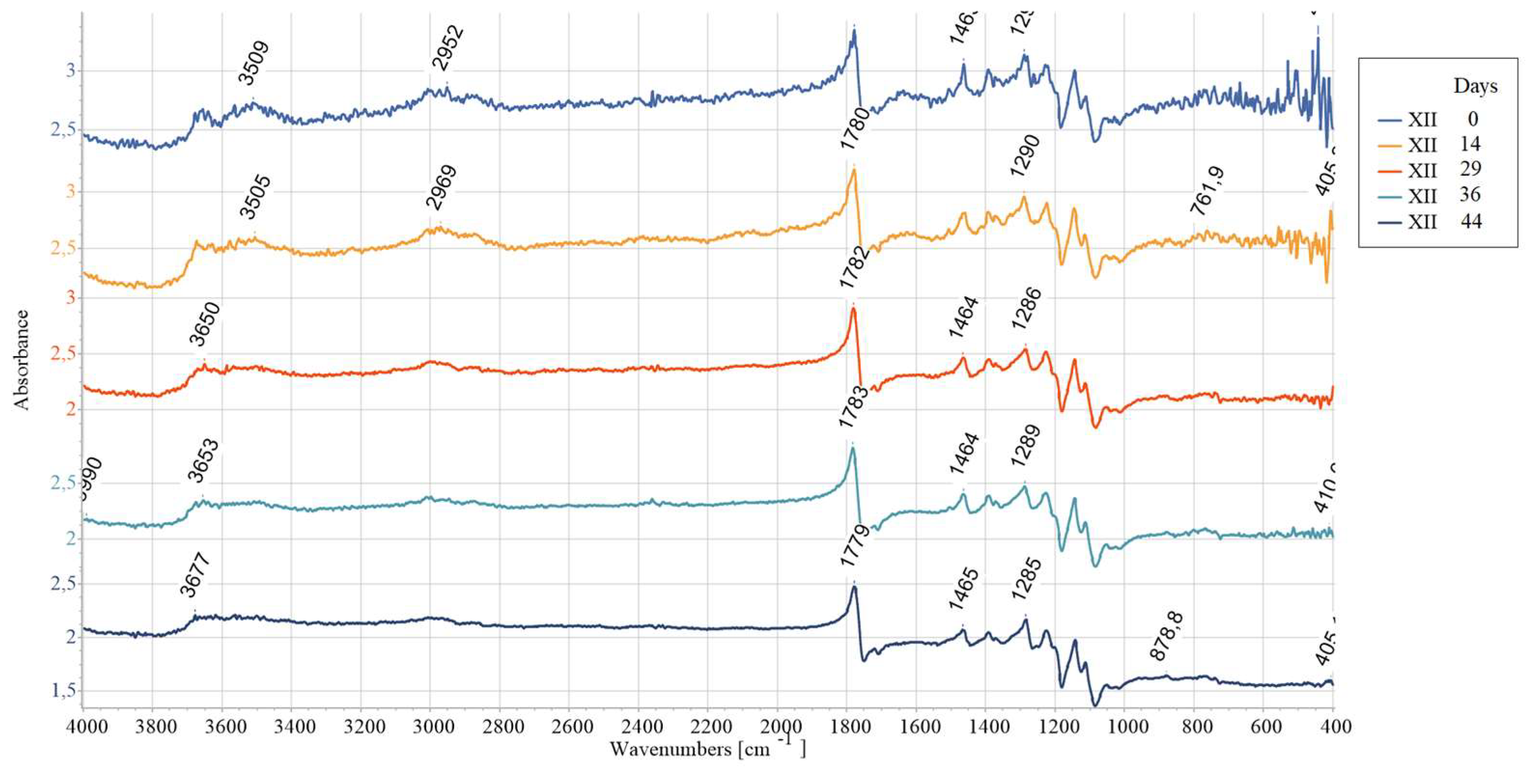

The quantification of the long-term degradation caused by aging was given for AP-I as an example. FTIR measurements are summarized in

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15. To study the degradation exhibited in the provided spectroscopic data over a 44-day period (31.01.2024-15.03.2024), multiple critical observations are examined: absorption trends and peak shifts. The absorbance values across the different dates generally show consistent behavior, with some peaks and troughs reflecting chemical changes over time. Certain peaks observed around specific wavenumbers appear to shift or change intensity over time.

The absorbance spectrum obtained on the first day of the investigation (31.01.2024) presents a characteristic baseline with peaks, indicating the initial state of the material being studied. Minor changes are observed after 14 days (13.02.2024) compared to the baseline, suggesting an initial phase of degradation or stabilization. At 29 days (28.02.2024) the spectrum appears more pronounced in certain absorbance peaks, indicating further degradation or alterations. New peaks are emerging, suggesting changes in chemical bonds. At 37 days (8.03.2024) the absorbance likely continues to increase or shift, hinting at ongoing degradation. Specific peaks show significant intensity changes, possibly indicating compound breakdown. At 44 days (15.03.2024) the spectral features are mostly pronounced, showing the final extent of degradation.

Broad peak (3984–3850 nm range) present initially (31.01.2024) are absent at later stages. This could be related to moisture or hydroxyl groups (-OH) disappearing over time. Initial high absorbance (2.85) at wave lines (~1779–1783 nm) which is associated with the stretching vibrations of carbonyl groups (C=O), later decreases slightly (2.40). This suggests slow degradation or oxidation effects on ester bonds. The peaks corelated with the C-H stretch (~3009–3010 nm) remains relatively stable but its intensity is slightly decreasing. This may indicate minor structural rearrangements but not complete polymer backbone breakdown. Noticeable absorbance fluctuations are registered at wavenumbers connected with C-H bending vibrations and C-C Stretch (1464–1465 nm, 1285–1288 nm). This could indicate chain scission or fragmentation due to the degradation as well as rearrangement of the polymer structure. In the region of small peaks (765–768 nm, 415–416 nm range) the absorbance first decreases (1.63 on 28.02) and then increases (1.85 on 08.03). This could be linked to crystalline vs. amorphous region changes.

Overall, the evolution of the absorbance spectra from the first to 44. day illustrates a trend of increasing degradation and structural change. Hydrolytic degradation, oxidating effects, and crystallinity changes are possible FTIR data interpretation. Hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid (PLA) occurs via ester hydrolysis, which is evidenced by the reduction in ester peak intensities observed around 1779 nm. The observed changes in the C=O and C–O peaks indicate mild oxidation, which may result from exposure to air. Variations in the peak intensities within the range of 765–768 nm suggest alterations in the material's amorphous and crystalline structure. These findings are in line with references [25,53-55]. From

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 it is obvious that the value of absorbance registered at the same wave line is higher as we move from samples IV towards sample X in each data series. The observed pattern is related with the set printing parameters. Since other printing parameters such as infill density, infill line direction etc. were constant in the study this means that the absorbance value is directly correlated with the used number of wall contour lines and its thickness.

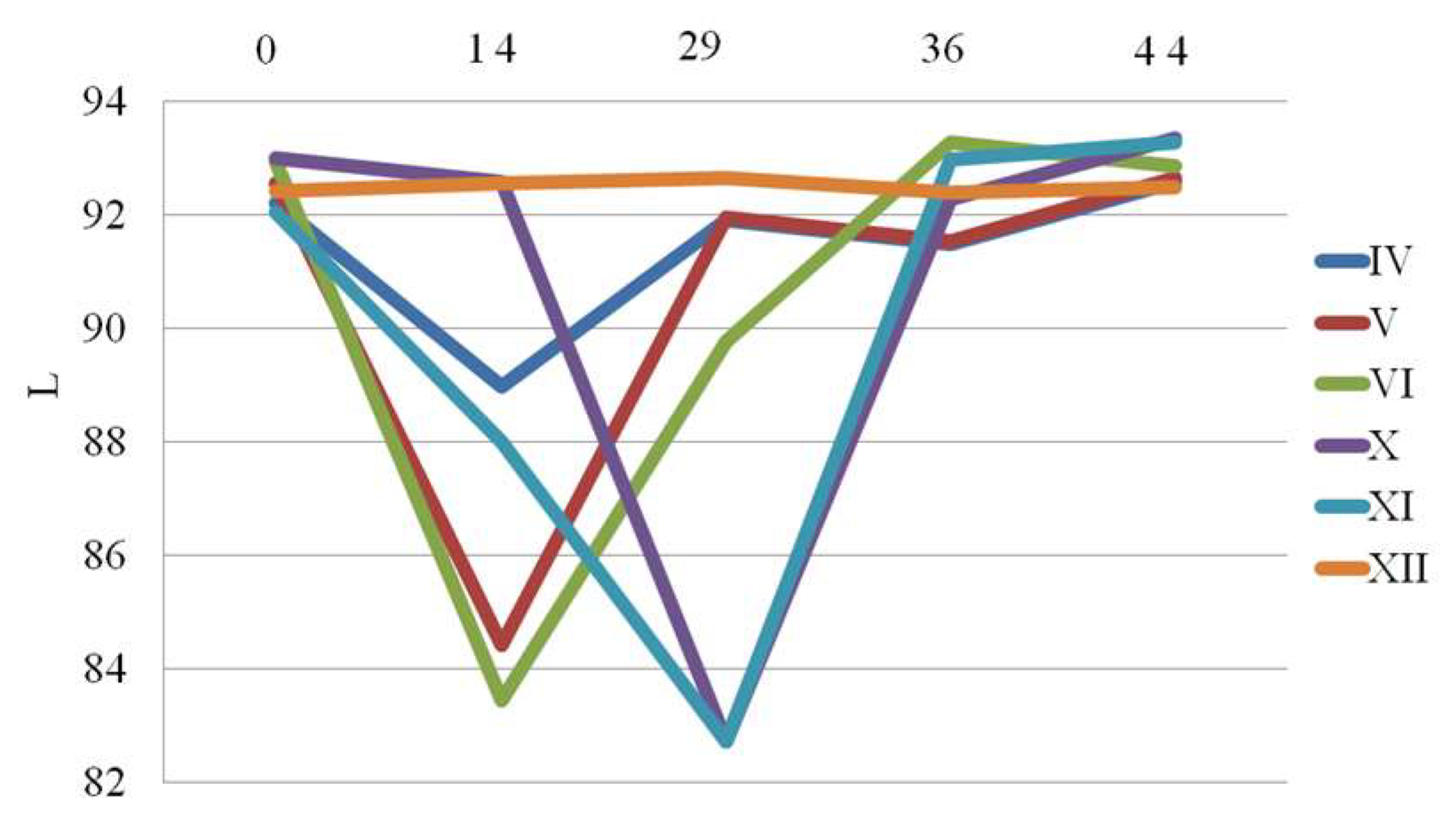

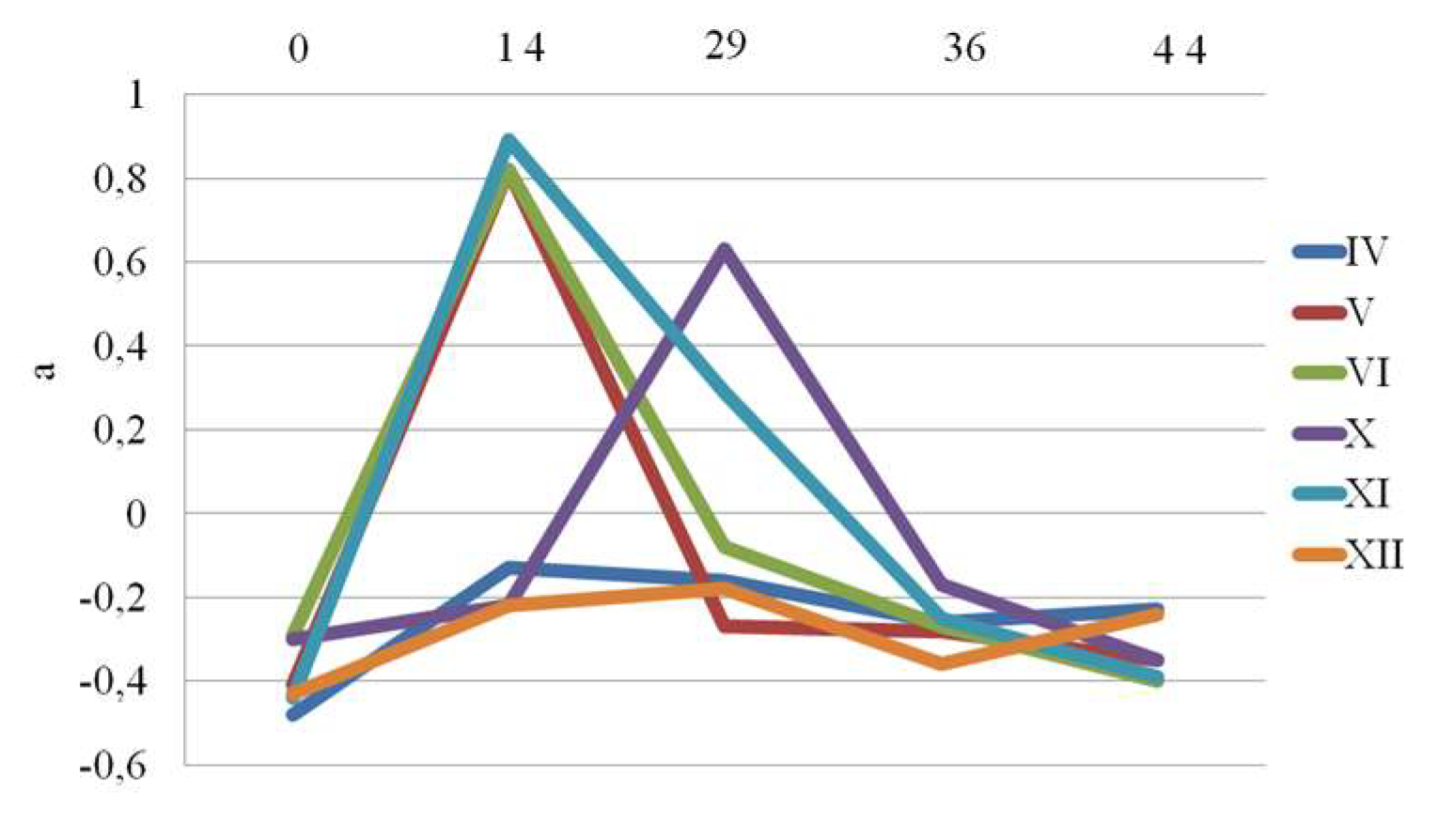

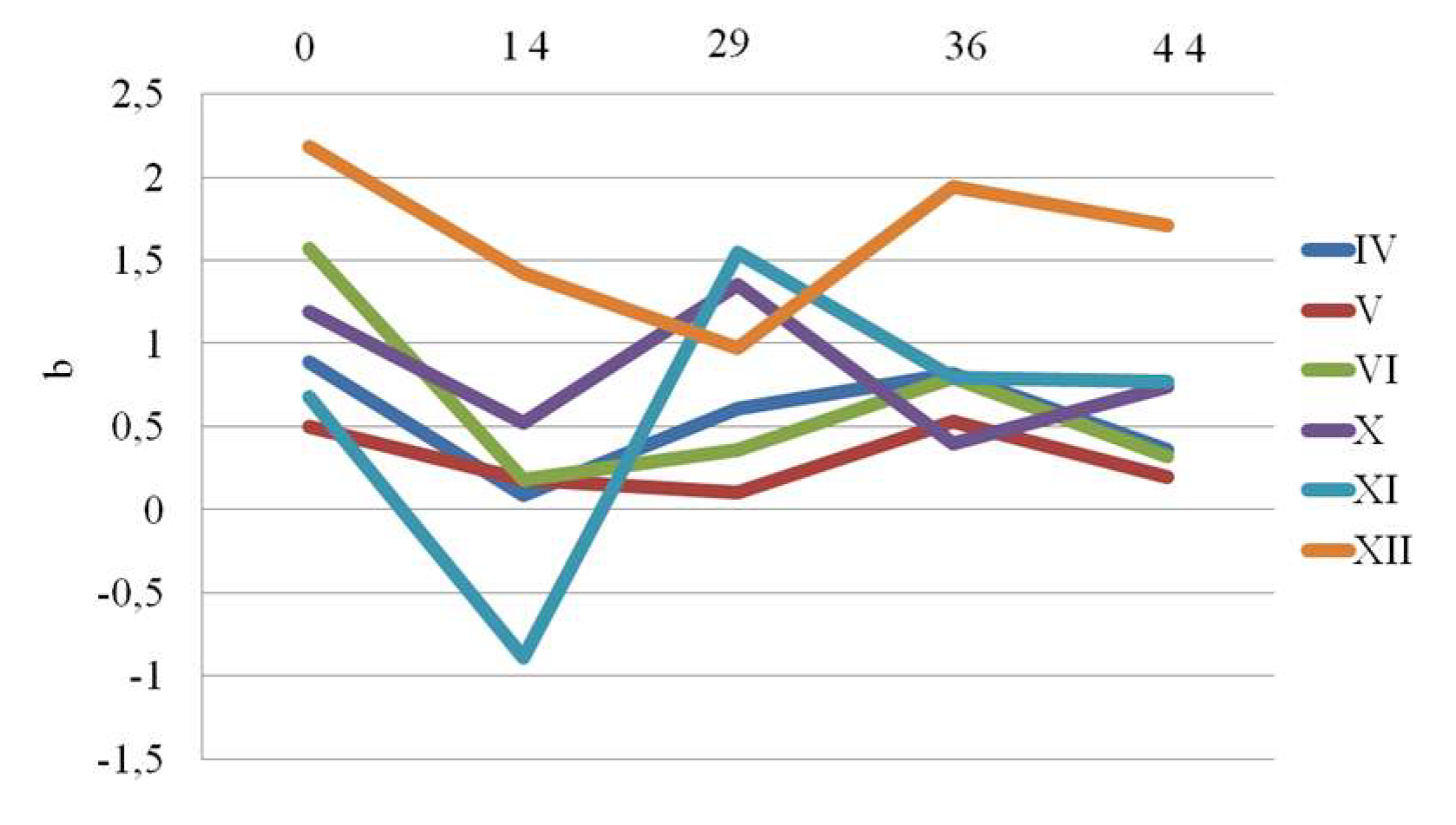

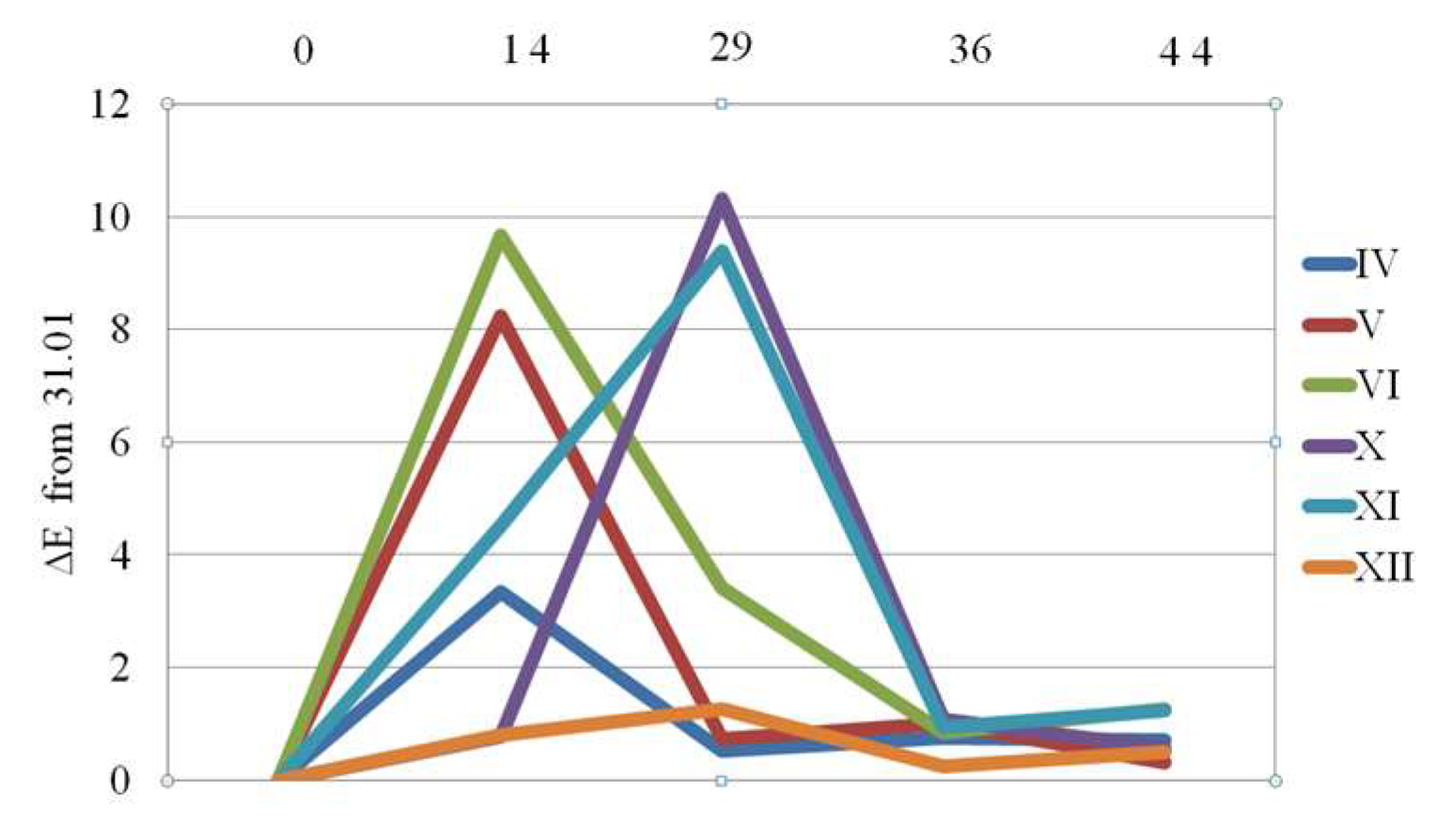

Colorimetric results are given in

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19. It is evident that sample XII maintained a highly stable

L value throughout the aging process. As aging progressed, a significant decrease in L values was observed after 14 days for samples IV to VI, and on 29

th day for samples X and XI. After this initial drop, a stabilization phase was noted. The

a value remained relatively stable for Samples IV and XII during the entire period. For the remaining samples, this value exhibited a pattern similar to that of L, with an initial drop followed by stabilization. The

b value showed the maximal decrease after 14 days for samples IV, VI, X, and XI. After that its value was rising and after 29 days were above the base line. From that point onward, a stabilization phase began. For Samples V and XII, the b values reached their lowest point at 29

th day and began to stabilize from 36

th day.

The overall conclusion about colorimetric behavior is visualized in

Figure 19. ΔE values exceeding 2 are typically considered noticeable to the human eye. In this context, significant color changes were observed for samples V, VI, X and XI, particularly after 14 and 29 days. These changes were later followed by a period of stabilization or partial recovery. The sample XII exhibited the most consistent color stability over time. These findings are also in line with the discussed pull-out and FTIR results.

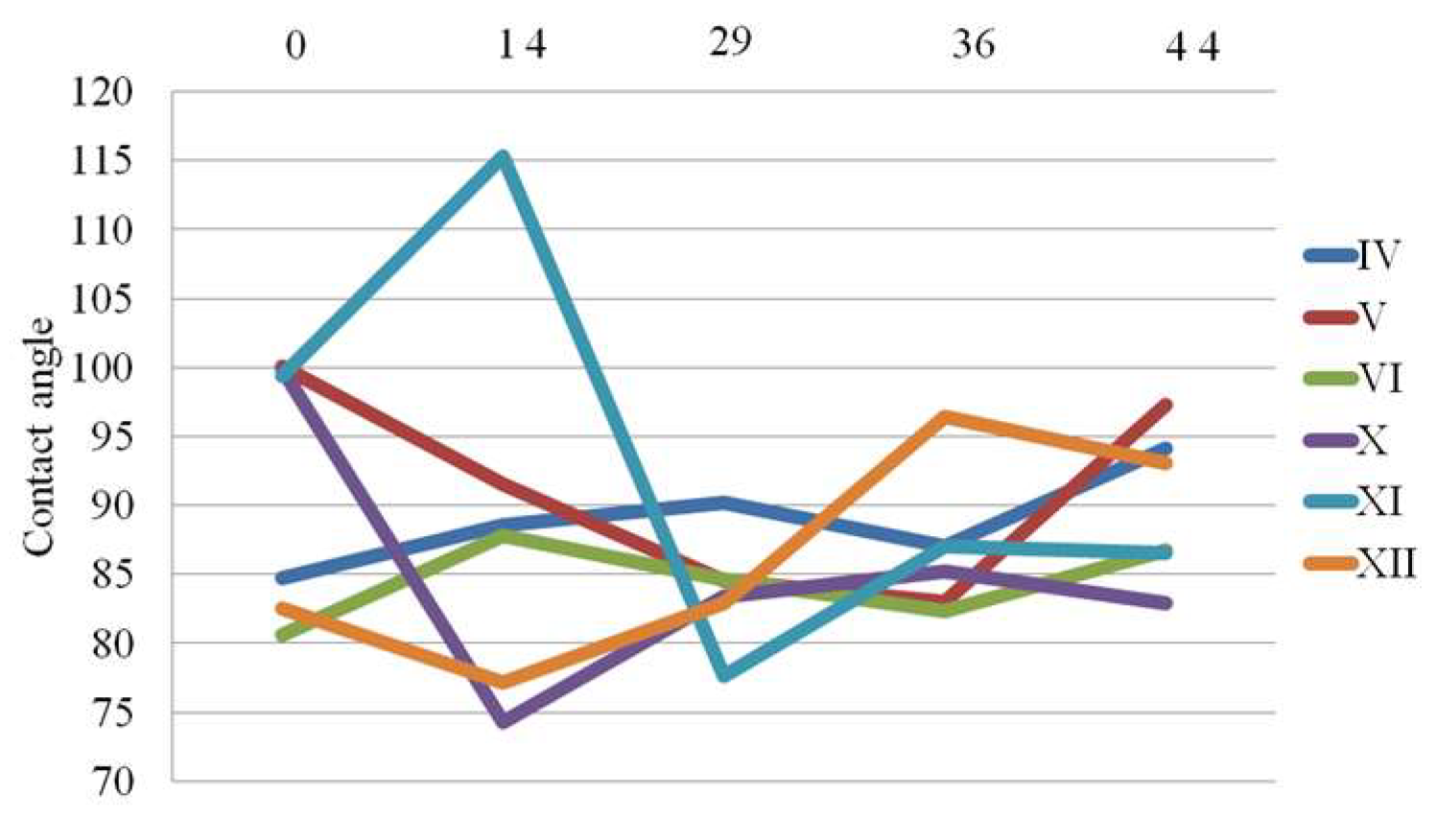

The parameter that describes wettability (wetting ability) of a material's surface is the contact angle. It is defined as the angle formed between the measuring fluid (water, glycerol, etc.) and the solid surface onto which it is applied. Results of contact angle measurements are summarized in

Figure 20.

The contact angle data indicates varying stability and hydrophobicity across different PLA samples over the aging period. While some samples, like IV and VI, show consistent improvement, others exhibit fluctuation of surface properties which origins from the environmental sensitivity or degradation processes.

The hydrophobicity of the sample IV is slightly improved during aging. This is probably a consequence of degrading which led some hydrophobic groups to be more exposed on the surface. In the case of sample V the contact angle is highest at the beginning. During aging its value is decreased to 83.02 after 36 days. From this moment its value is increasing until it is recovered closely to the baseline. A relatively stable performance with approximately gradual improvement in hydrophobicity was observed for sample VI. A significant loss in hydrophobicity followed with a slight recovery was observed for sample X. An unusual and unexpected high contact angle of 115° was registered for sample XI after 14 days. After that a decreasing trend was observed before material was stabilized. In case of sample XII an improvement in hydrophobicity after some initial fluctuations was also observed.

As can be seen from our FTIR data interpretation PLA degradation follows three stages: hydrolysis, oligomer formation and crystallinity increase. During hydrolysis ester bonds are cleaved which will led to the increased hydrophilicity. During oligomer formation the chains become smaller. This will inevitably lead to the variable surface properties. As crystallinity increases degraded amorphous regions become more hydrophobic. This means that in cases of samples where contact angle indicates a shift towards more hydrophobic surface the crystallinity or surface roughening is probable degradation mechanism. In our case this are experiments IV (have steady increase) and VI (shows an upward trend after an initial drop). In cases of samples where contact angle is causing a shift towards more hydrophobic surfaces the hydrolysis is the dominating degradation mechanisms. Representative examples are samples X (have a sharp drop) and XI (have a falling trend after its peak). In case when significant variability in contact angle is registered material will over go simultaneously through hydrolysis and crystallization. Experiments V (has a dip and recovery) is a typical example of such behavior.

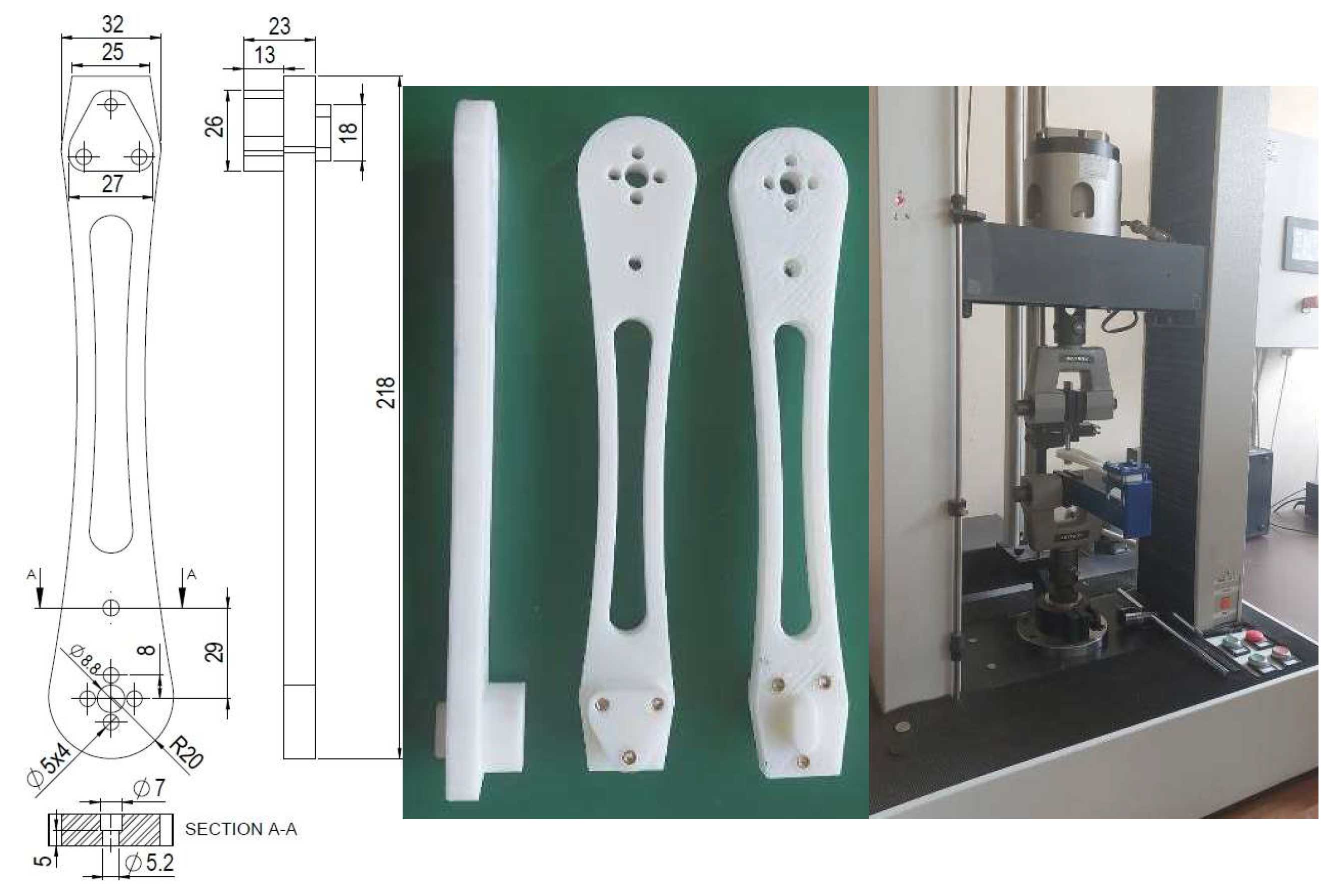

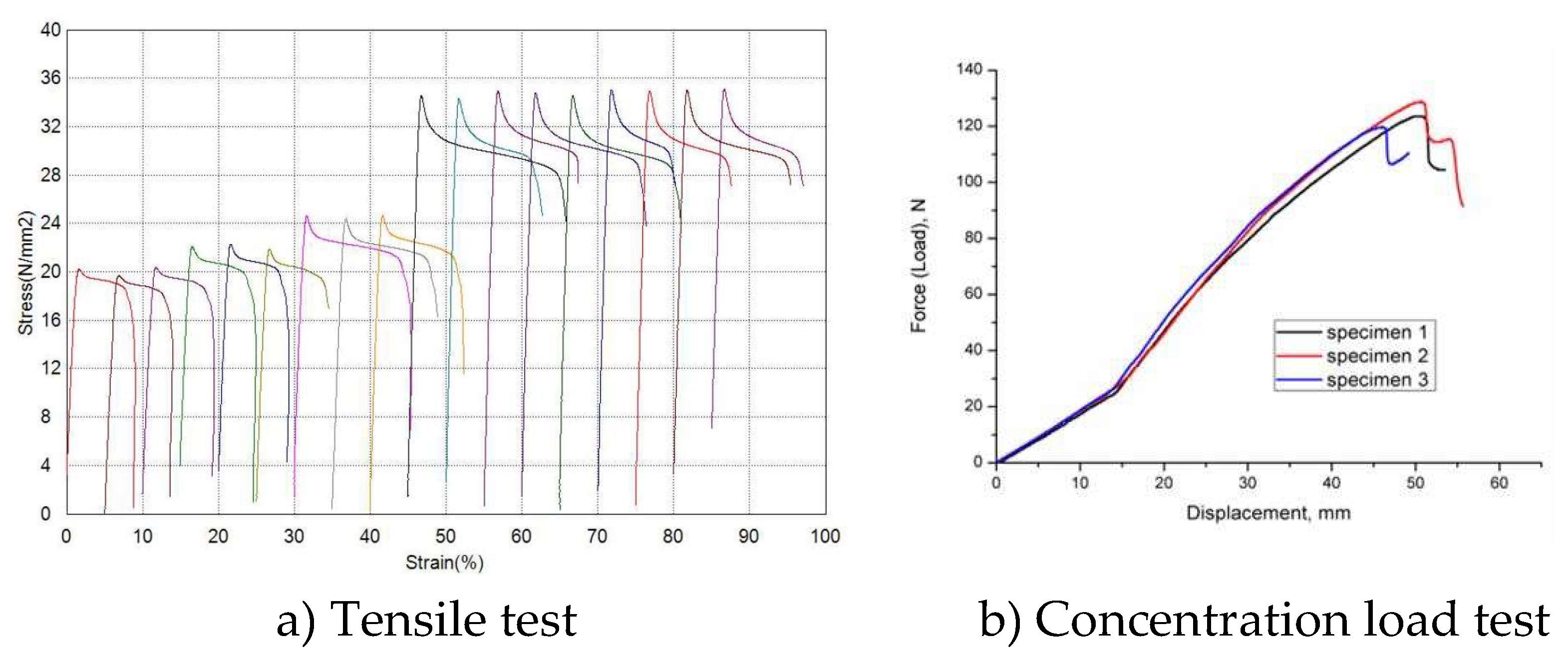

The results of tensile and concentrated load test after one year of natural aging is given in

Table 3 and

Figure 22. A positive correlation between maximum stress and strain is generally observed. The modulus of elasticity shows a pronounced increase from samples VI towards sample XII. A higher modulus indicates that these samples not only withstand greater loads but do so while maintaining a high degree of stiffness, which is desirable characteristics for drone application.

Clear increasing trend in maximum stress and strain from groups IV to XII is visible. samples X, XI, and XII have significantly higher tensile strength than those in groups IV, V, and VI. The average maximum stress in case of samples IV and V is between 18–19 N/mm². The corresponding strain values for these samples remains relatively low, indicating a brittle property.

Sample VI has a slight increase in average maximum stress in comparison to the samples IV and V. Besides more variation of strain values are also observed. This leads to a moderate strength and ductility improvement of this sample in comparison to previous one. Maximum stress for the samples X-XII is around 28 N/mm². The substantial elongation, especially in samples X-1 and XI-2 was registered. This is a clear indication that samples X-XII are more ductile. Besides, the morphology of samples after tensile tests, which is shown in

Figure 22, is in line with the observed ductility pattern. As we move from sample IV to sample XII the ductility is rising. Samples IV and V are mostly brittle while samples VI – VII are more ductile.

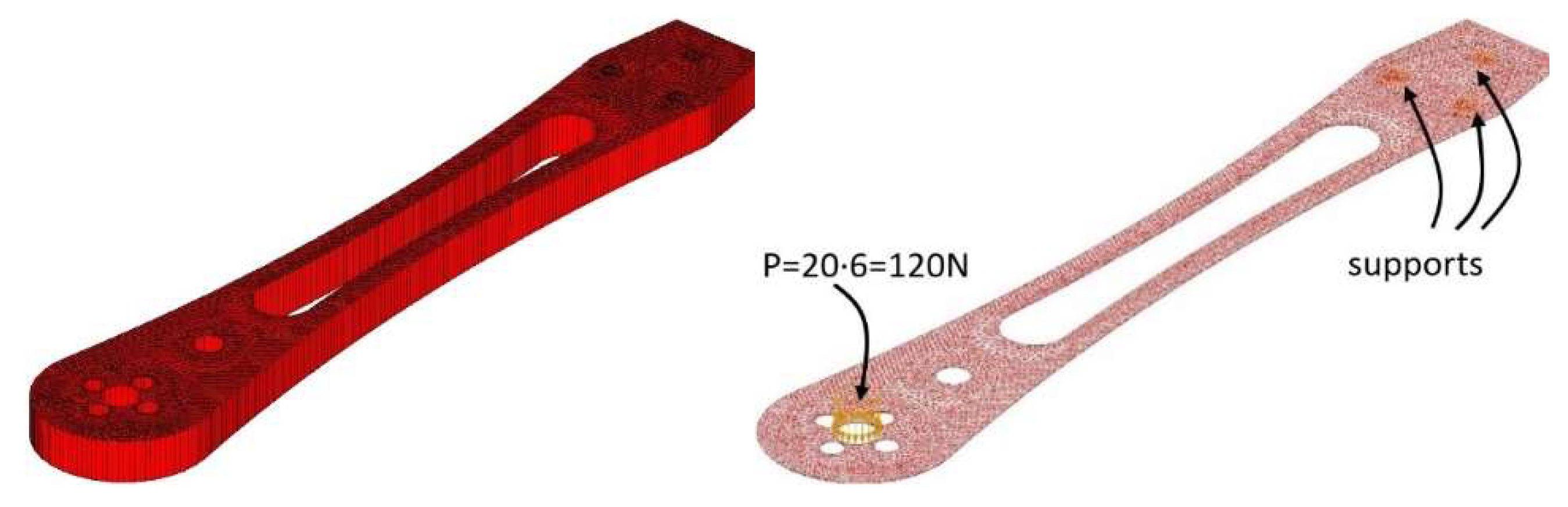

The relationship between force and displacement on the concertation load test appears to be linear at the beginning suggesting elastic behavior of the drone arm up to approximately 25N. As the force continues to increase, the rate of displacement begins to accelerate (see the slope change). From this moment the material is experiencing plastic deformation or yielding. In the vicinity of the maximal force (mean value 127 N) a noticeable stiffness reduction is registered.

Figure 23 shows the drone arm with applied self-weight (uniformly distributed over the surface) along with the supports and place where concentrated force was applied. A concentrated load of 120 N, acting orthogonally to the mid-plane of the drone arm, was used. This value represents the maximum force that the printed arm withstood during concentration load testing. Since this force is exerted at the central hole of the arm, it was redistributed along the hole’s perimeter into 20 equal segments. Additionally, the supports were modeled as annular line supports with stiffness components in all three orthogonal directions (kx=ky=kz=10

10 kN/m/m) while the rotational stiffness was set to zero.

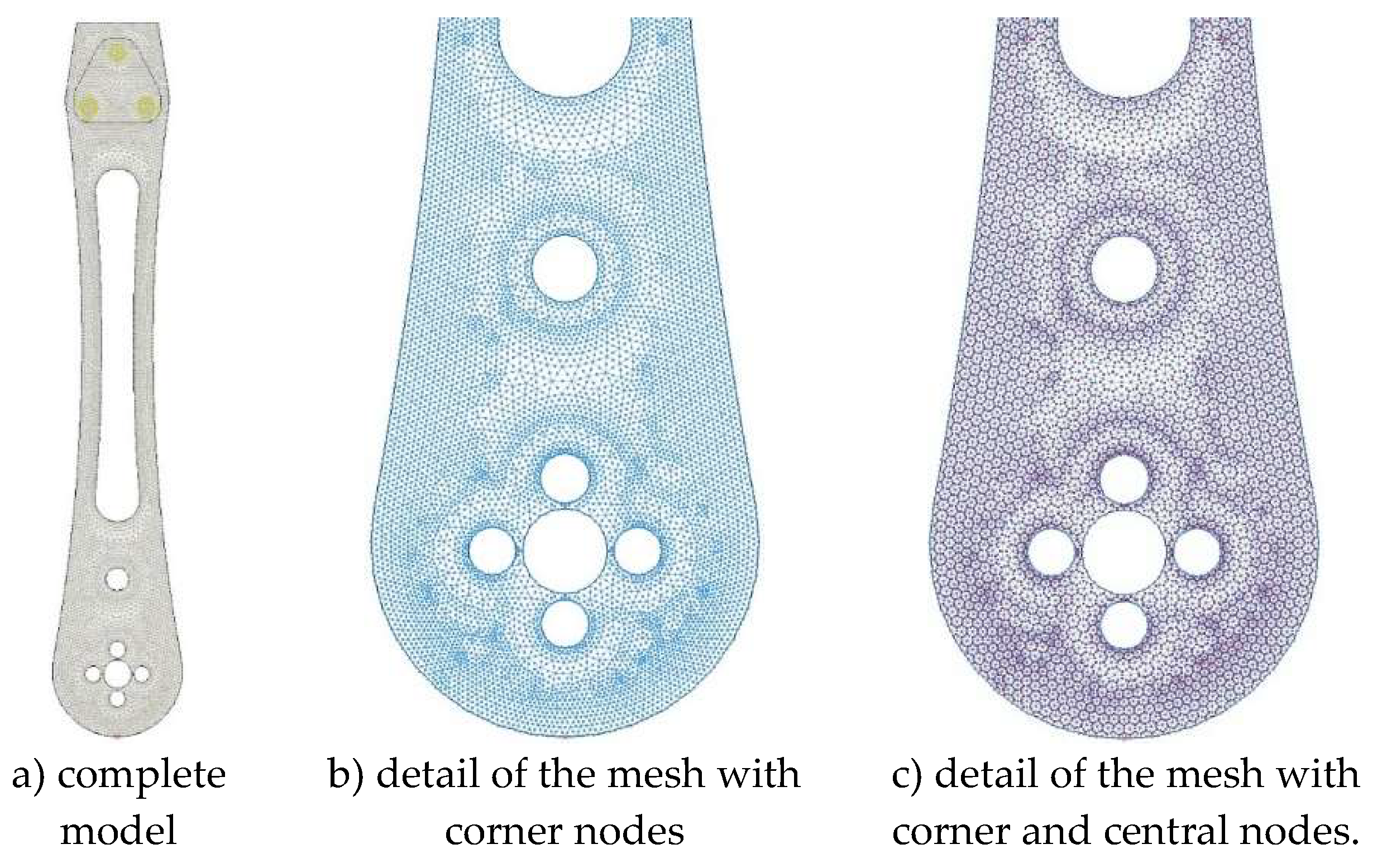

The

domain of the drone arm was modeled using a

triangular surface finite element mesh. The mesh was generated with an

average element side length of 1 mm, with additional refinement applied in the contour regions, where the element side lengths were reduced to less than 1 mm. This triangular finite element comprises

six nodes (three at the corners and three at the midpoints of the edges) and is formulated according to

Mindlin-Reissner theory, which incorporates the effects of

shear deformation. The entire numerical model of the drone arm was treated as a surface model with three degrees of freedom per node: two rotational degrees of freedom about the two orthogonal horizontal axes and one translational degree of freedom in the vertical direction. The model comprises a total of 9423 surface finite elements, with 5103 corner nodes and 14532 intermediate nodes. The generated finite element mesh for the complete model is given in

Figure 24. A statical analysis was done in AxisVM software. Model had 58905 equilibrium equations.

Forces in the cross-section of the drone arm include: moments m

x, m

y, m

xy, and shear forces q

x, q

y. The global axes are: horizontal X and vertical Y axis. The main influences are defined as: m

1, m

2, angle α

n, and the resultant shear force q

R. The main directions of influence were: direction 1 and direction 2. The stress states iso-surfaces are shown for: stresses s

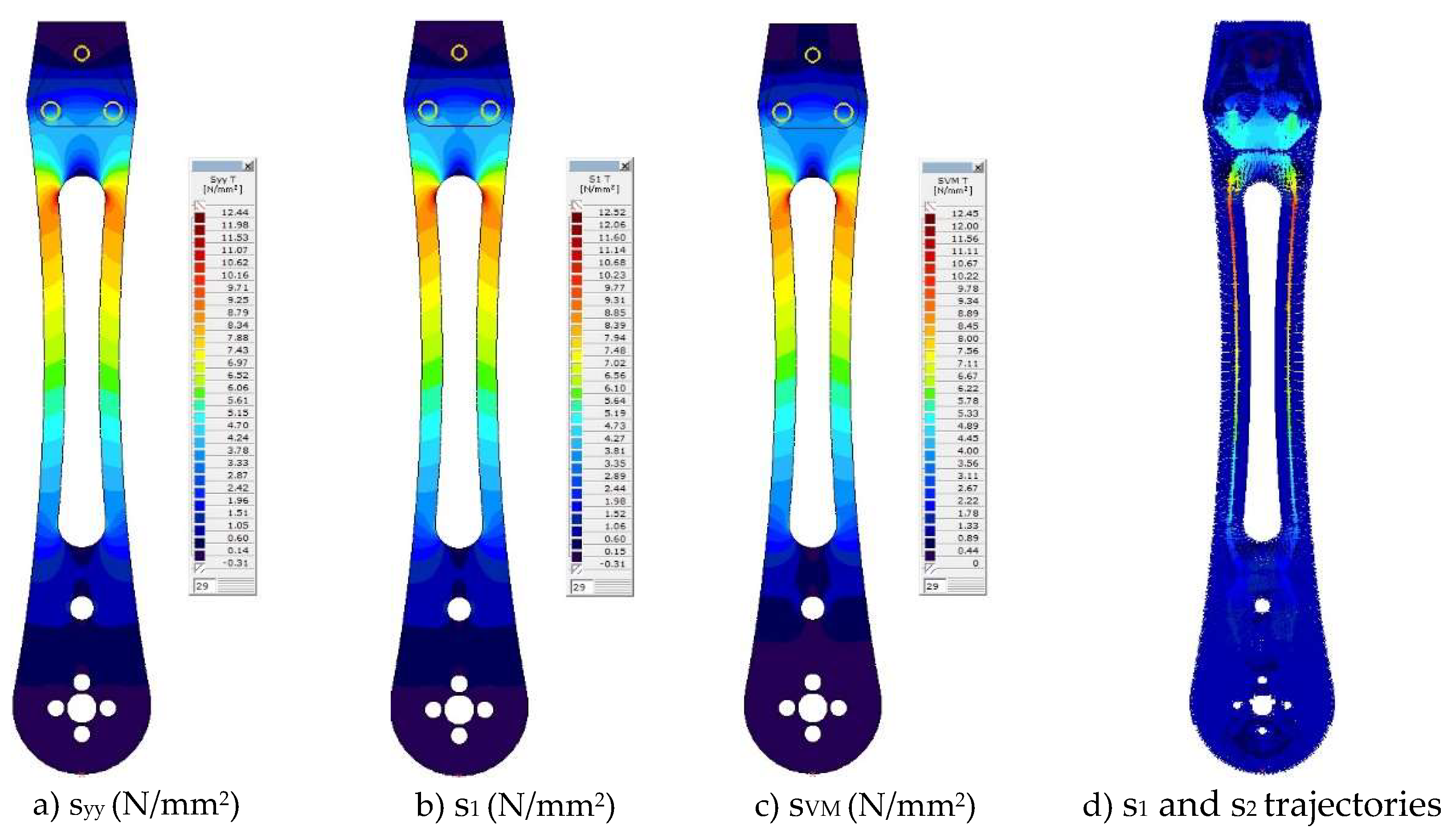

yy in the Y axis direction, stresses s

1 in the principal direction 1, and Von Mises stresses s

VM at

Figure 25.

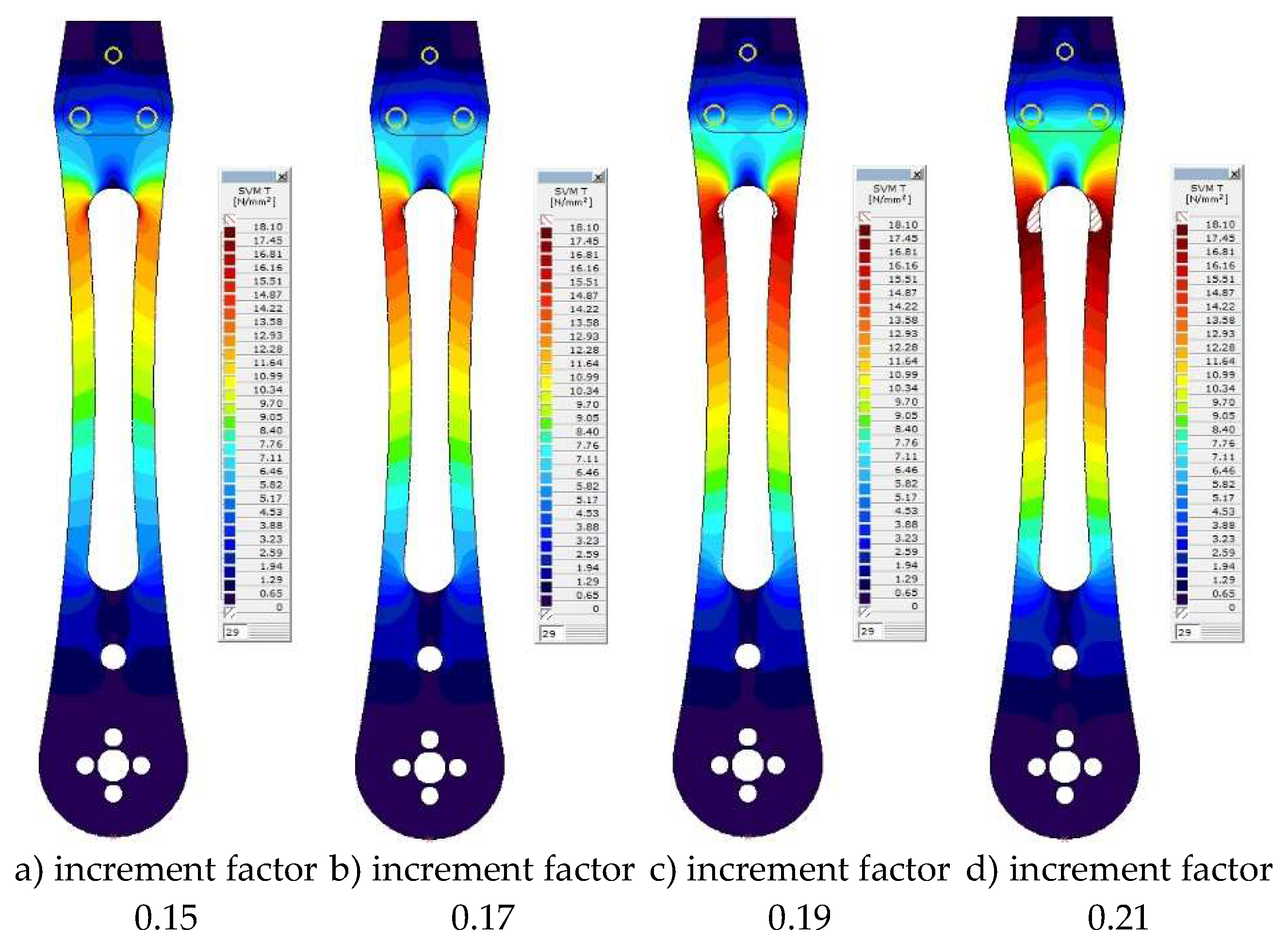

The evolution of stress states and its distributions in the drone leg within the linear behavior domain was calculated using the force increment of 0.1. Additionally, the integral illustration of the principal stresses s1 and s2 trajectories is also provided. Stresses are shown only for the upper surface of drone arm, since all dominant load bearing stresses are occurring on this side. Now it is obvious that all three stress states yield similar solutions in terms of intensity. However, in order to identify and analyze the zone of material plasticity development and crack formation, further investigation was conducted relying on Von Mises stresses, which combines sxx, syy and sxy stresses. In this regard, the maximum value of Von Mises iso-surface stress is limited to the yield stress of the material (18.1 N/mm2 for sample IV). Numerical analyses of the drone arm were carried out using an iterative procedure, starting with an initial scaling factor of 0.15 for the concentrated force set at 120 N. This value was then progressively increased in increments of 0.01.

The Von Mises iso-surfaces stress states for the scaling factors 0.15, 0.17, 0.19, and 0.21 are given in

Figure 26. The zone of plasticity initiation is now clearly identified. This process takes place from the inner edge to the outer edge of the drone arm.

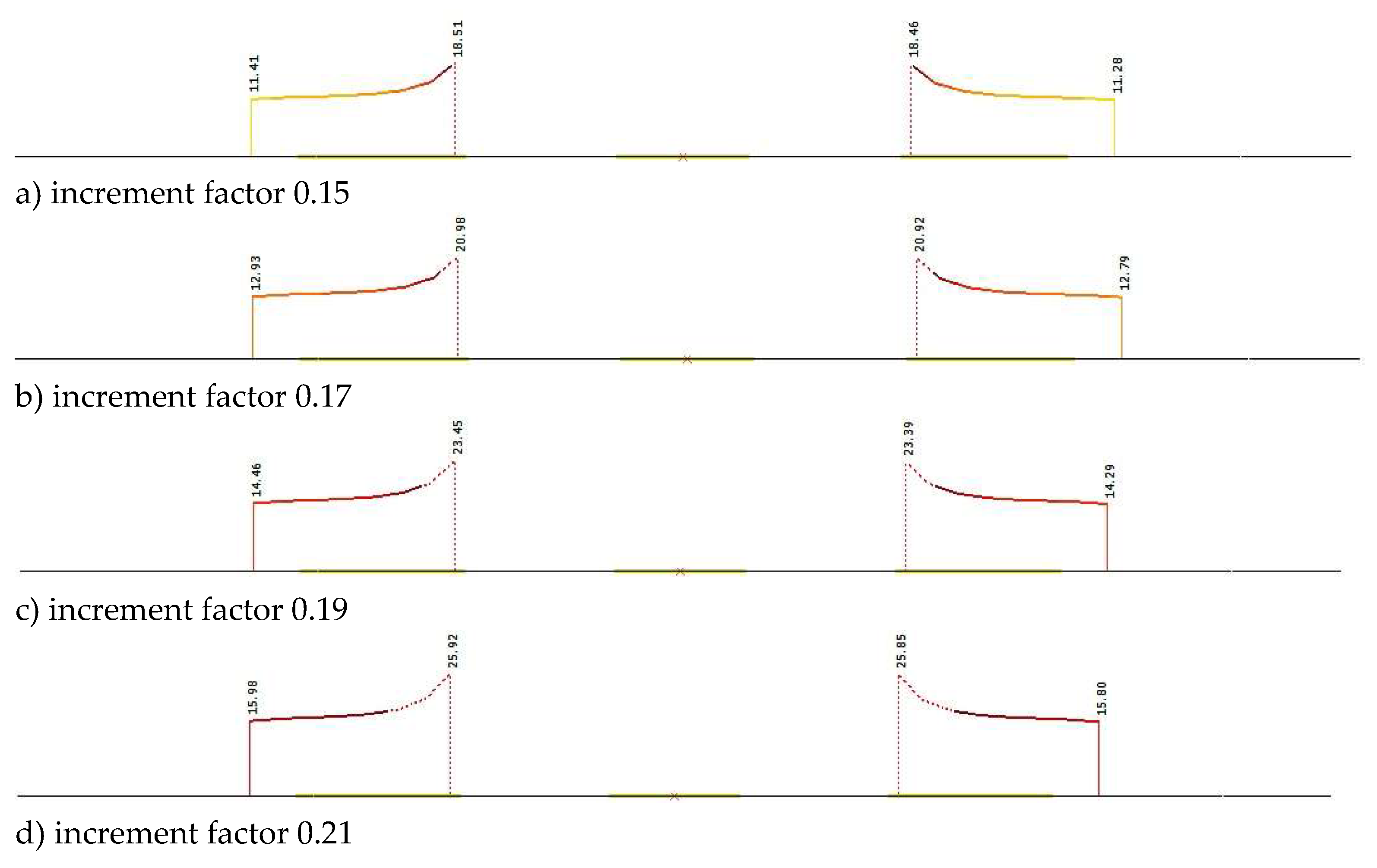

The development of Von Mises stresses in the cross-section where yielding occurs, is given at

Figure 27 for the same scaling factors. It is obvious that stresses are not evenly distributed across the cross-section. Besides, they are significantly higher at the inner side of the drone's arm. This means that yielding initially develops from the inner side and progresses to the outer side of the drone's arm.

Table with calculated concentration loads (ACL) which drone arm can hold without entering into the plastic zone with confidence levels of 10% and 20% is summarized in

Table 4 for all samples. The classification of drone size vs payload capacity is summarized in

Table 5.

It is evident that if our printed drone arms are installed in quadcopter drone its payload capacity will corresponding to the large drone class. It is important to note that this is excellent output result since the infill density and raster line in this study were set to 35% and 0.3. It is well known that mechanical properties of printing parts are in direct relation with the infill density and raster line. The common value of infill density for high quality parts is around 70%. It was proven that PLA filament is suitable for drone application. Besides it was observed that even the aged drone arms printed with the low infill density can withstand high pay load capacity (1,46 – 2,31 kg). The future work will focus on repeating the procedure described in this paper, but on drone arms printed with higher infill density, such as 70, 80, and 90%. It is planned also to see how the raster line affects the mechanical properties of the aged printed parts. That is why each infill density will be represented by 12 different combinations. The anticipated preset combination is shown in

Table 6.

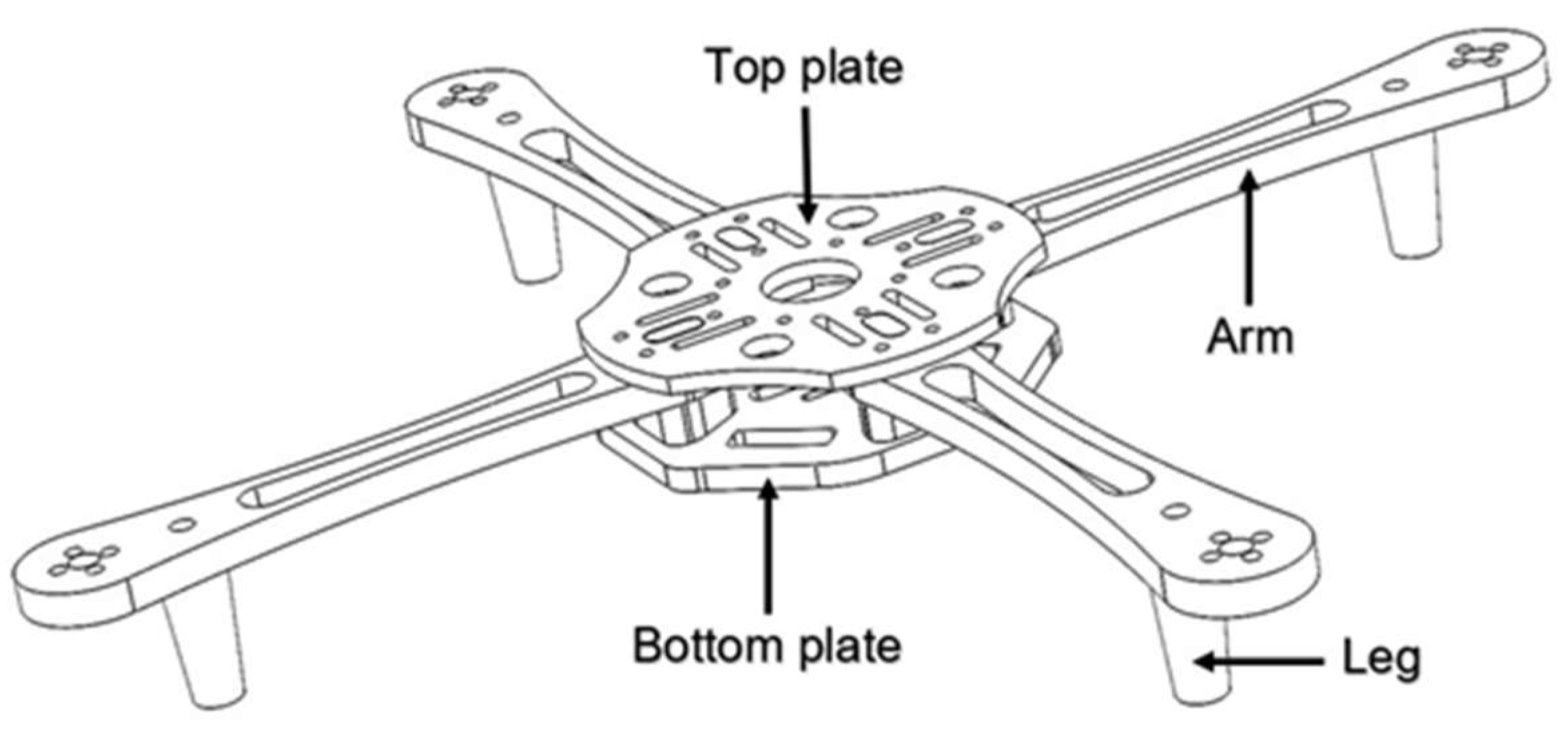

Figure 1.

Scheme of drone frame parts.

Figure 1.

Scheme of drone frame parts.

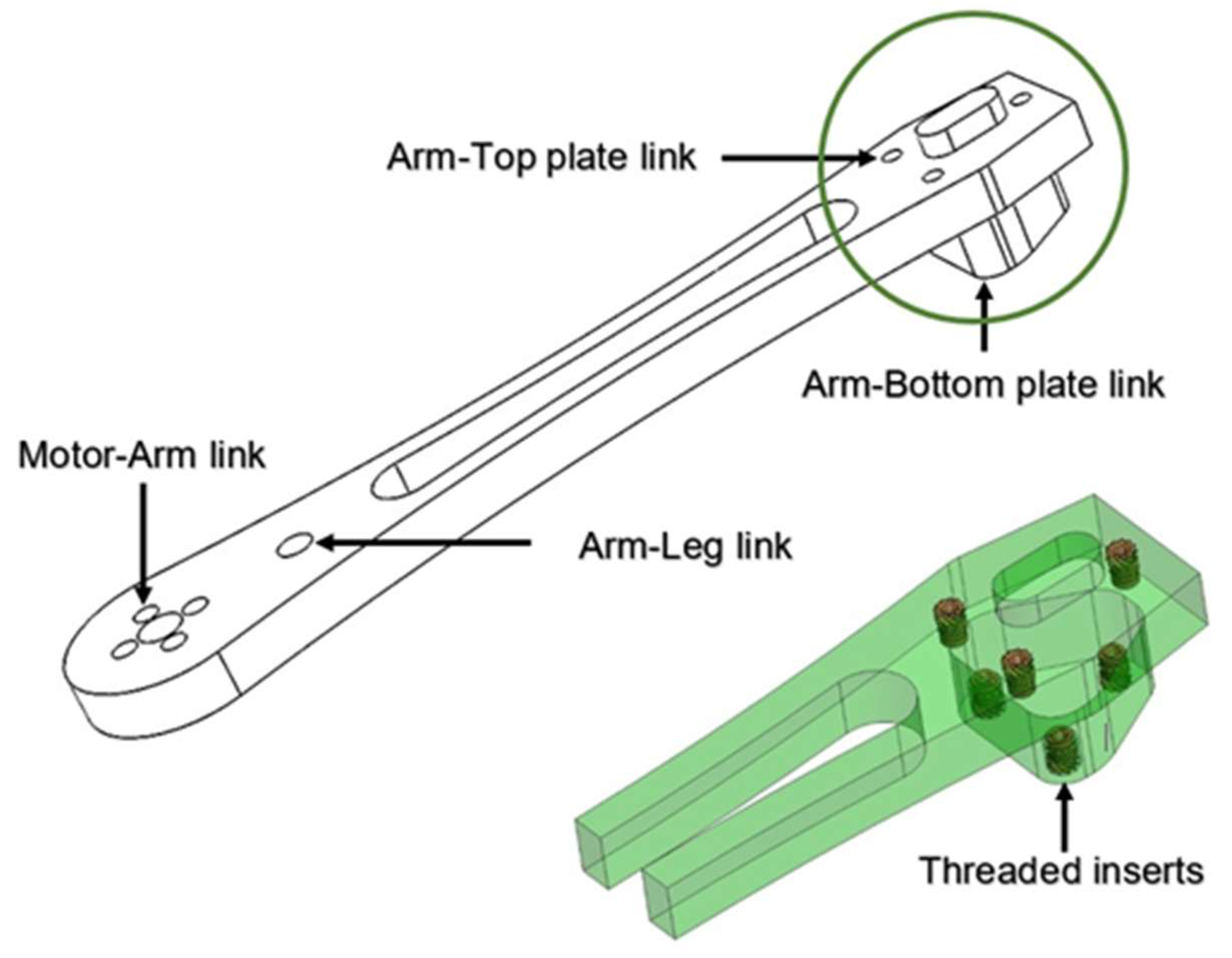

Figure 2.

Scheme of the threaded inserts placement in the drone arm.

Figure 2.

Scheme of the threaded inserts placement in the drone arm.

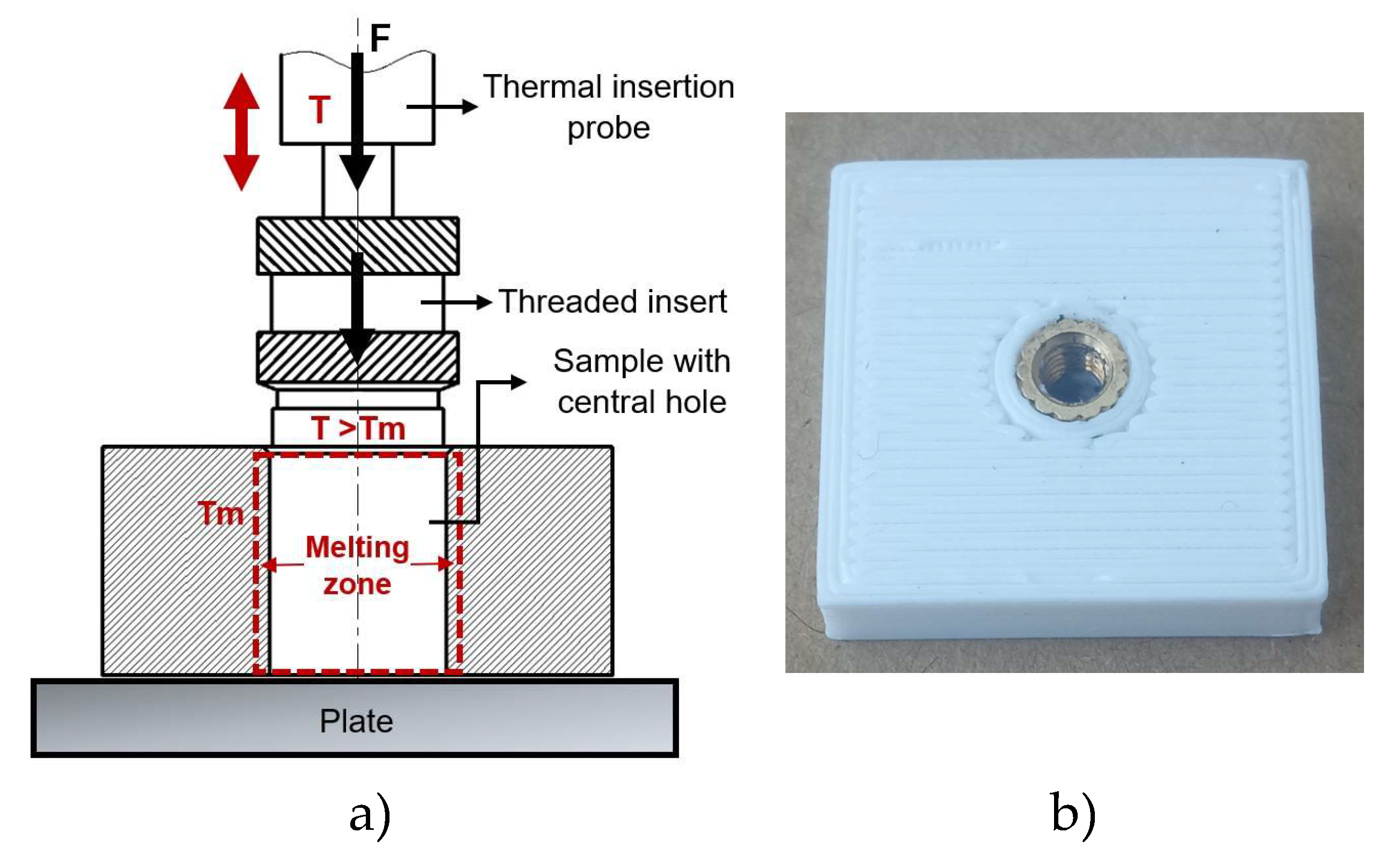

Figure 3.

Heat staking process: a) procedure schematic view; b) Final output.

Figure 3.

Heat staking process: a) procedure schematic view; b) Final output.

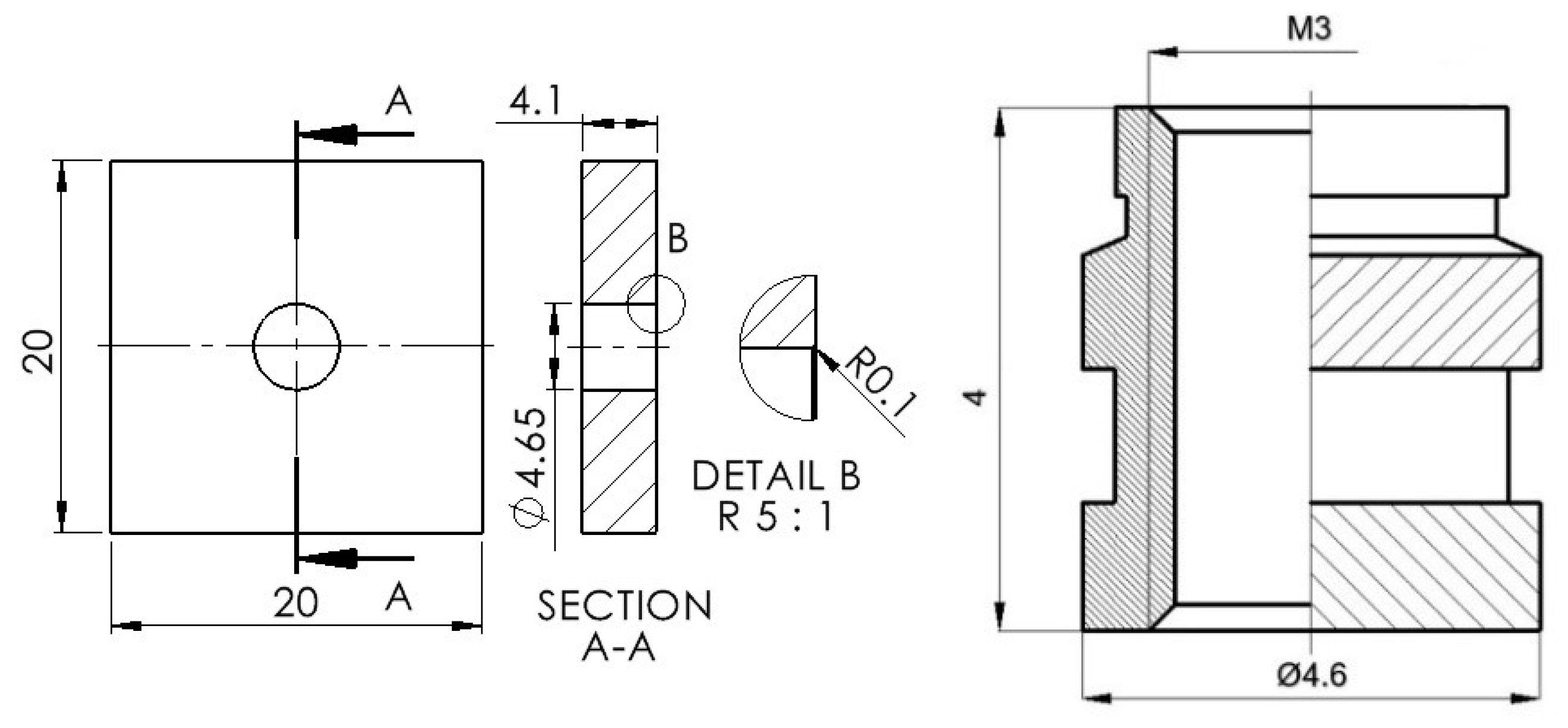

Figure 4.

The scheme of the sample and brass dimensions.

Figure 4.

The scheme of the sample and brass dimensions.

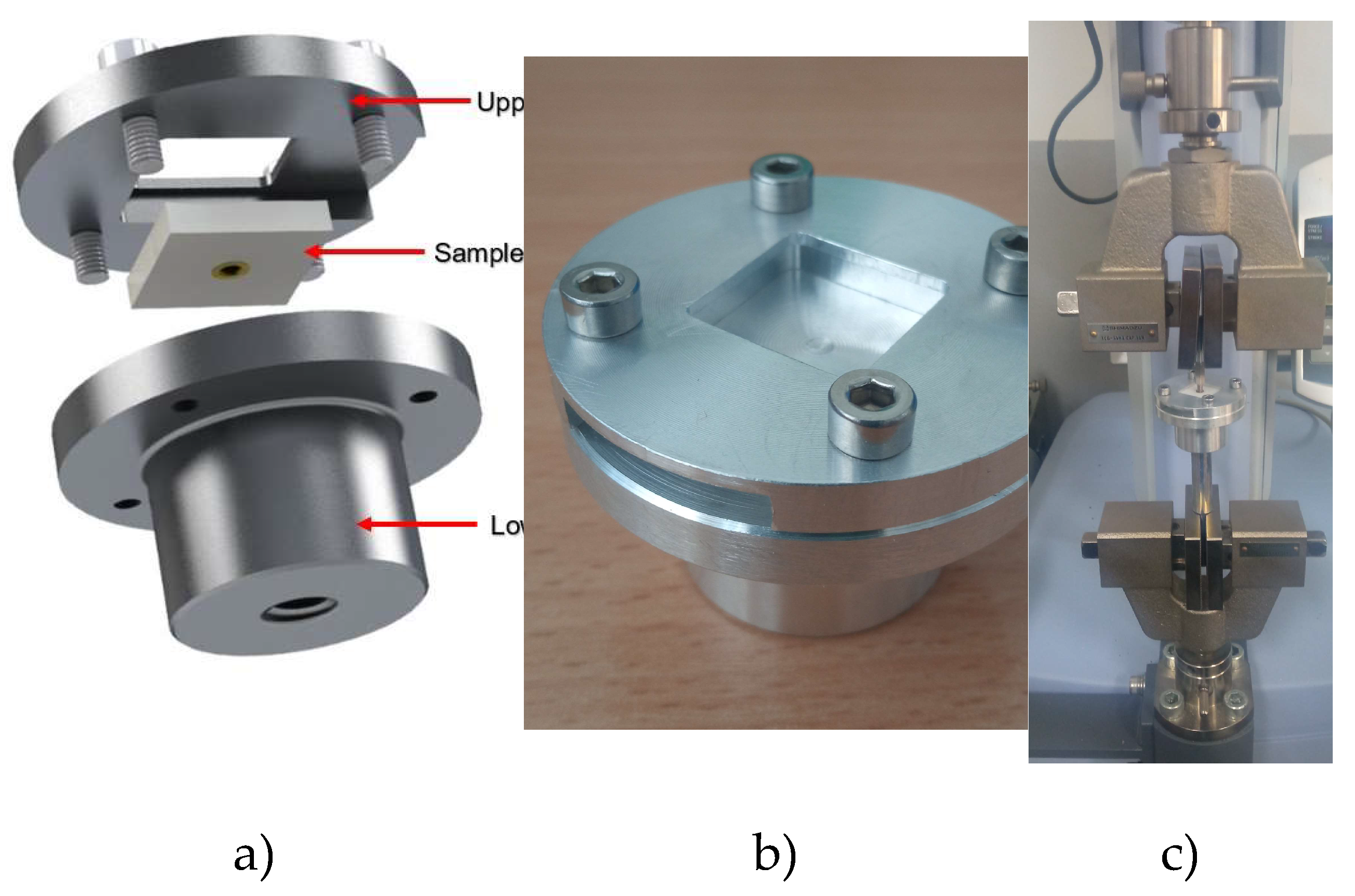

Figure 5.

Adapter tool: a) 3D model, b) manufactured model, c) setting.

Figure 5.

Adapter tool: a) 3D model, b) manufactured model, c) setting.

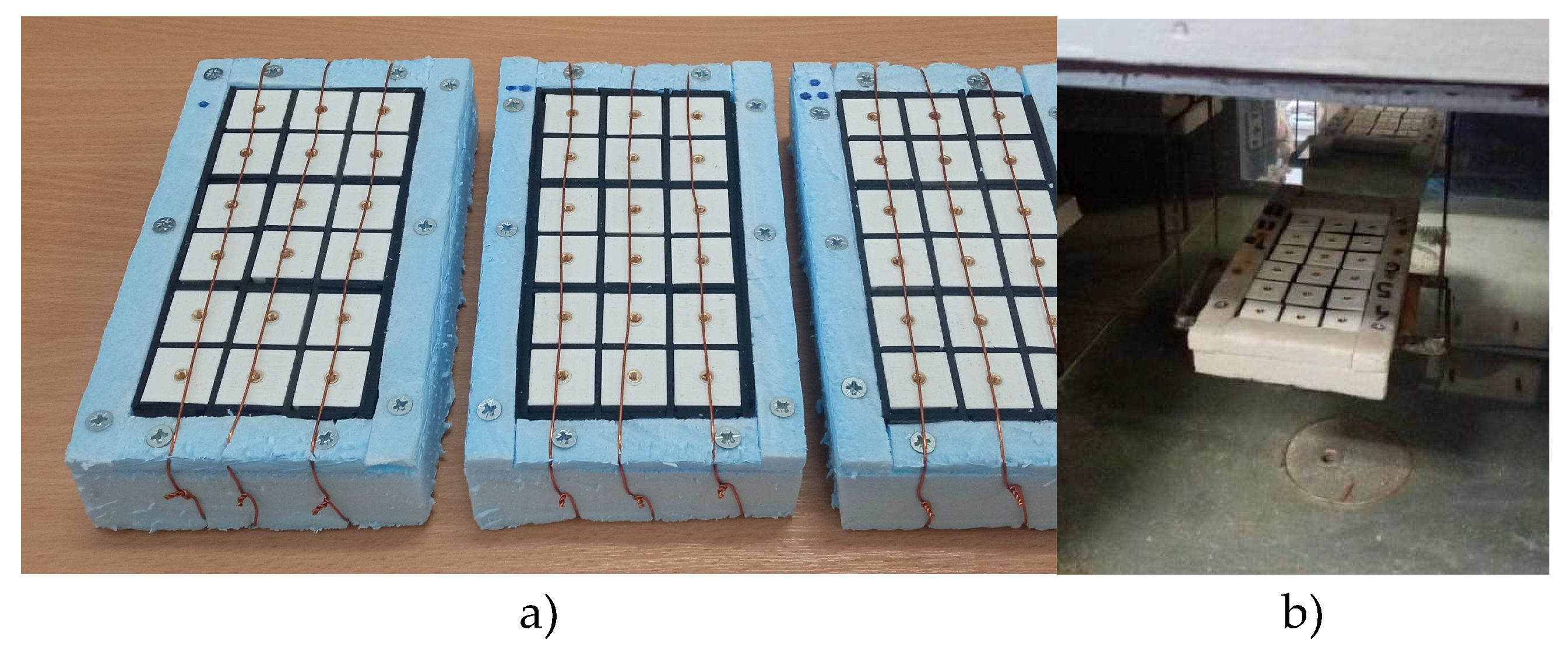

Figure 6.

Preview of test panels: a) settings, b) the second artificial aging.

Figure 6.

Preview of test panels: a) settings, b) the second artificial aging.

Figure 7.

Concentrated load position and drone arm dimensions.

Figure 7.

Concentrated load position and drone arm dimensions.

Figure 8.

Drop of pull-out force in treated samples in comparison to the SP.

Figure 8.

Drop of pull-out force in treated samples in comparison to the SP.

Figure 9.

Nozzle trajectory during printing samples IV – VI.

Figure 9.

Nozzle trajectory during printing samples IV – VI.

Figure 10.

The morphology of the tested samples after the pull-out test for NP-II, AP-III and AP-V.

Figure 10.

The morphology of the tested samples after the pull-out test for NP-II, AP-III and AP-V.

Figure 11.

The appearance of samples AP-II after pull-out test.

Figure 11.

The appearance of samples AP-II after pull-out test.

Figure 12.

FTIR analysis conducted before aging (base line – 0 days data set).

Figure 12.

FTIR analysis conducted before aging (base line – 0 days data set).

Figure 13.

FTIR analysis conducted after 44 days.

Figure 13.

FTIR analysis conducted after 44 days.

Figure 14.

FTIR analysis conducted for the sample IV.

Figure 14.

FTIR analysis conducted for the sample IV.

Figure 15.

FTIR analysis conducted for the sample XII.

Figure 15.

FTIR analysis conducted for the sample XII.

Figure 16.

Change of L during aging.

Figure 16.

Change of L during aging.

Figure 17.

Change of a during aging.

Figure 17.

Change of a during aging.

Figure 18.

Change of b during aging.

Figure 18.

Change of b during aging.

Figure 19.

Color difference ∆E.

Figure 19.

Color difference ∆E.

Figure 20.

Change of contact angle during aging.

Figure 20.

Change of contact angle during aging.

Figure 21.

Tensile (a) and concentration load (b) results.

Figure 21.

Tensile (a) and concentration load (b) results.

Figure 22.

The sample morphology after tensile (a), and concentration load (b).

Figure 22.

The sample morphology after tensile (a), and concentration load (b).

Figure 23.

Isometric view of the numerical model of the drone arm.

Figure 23.

Isometric view of the numerical model of the drone arm.

Figure 24.

Generated finite element mesh.

Figure 24.

Generated finite element mesh.

Figure 25.

The stress state iso-surface (top surface of the leg) for a force increment of 0.1·P.

Figure 25.

The stress state iso-surface (top surface of the leg) for a force increment of 0.1·P.

Figure 26.

Von Mises stress state iso-surface (arm top surface) for various force increments.

Figure 26.

Von Mises stress state iso-surface (arm top surface) for various force increments.

Figure 27.

Von Mises stresses in the section where yielding occurs for various the scaling factors.

Figure 27.

Von Mises stresses in the section where yielding occurs for various the scaling factors.

Table 1.

Printing parameter combinations.

Table 1.

Printing parameter combinations.

| Samples designation code |

IV |

V |

VI |

X |

XI |

XII |

| Wall thickness [mm] |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

| Wall line contour |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Top layer number |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| Bottom layer number |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Table 2.

The results of the pull-out tests after natural and artificial aging.

Table 2.

The results of the pull-out tests after natural and artificial aging.

| Designation code |

Pull-out force [N] |

| SP |

NP-I |

NP-II |

AP-I |

AP-II |

AP-III |

AP-IV |

AP-V |

| IV |

433 |

211 |

113 |

55 |

60 |

73 |

79 |

89 |

| V |

442 |

235 |

135 |

71 |

75 |

93 |

97 |

105 |

| VI |

505 |

275 |

175 |

85 |

91 |

116 |

122 |

131 |

| X |

578 |

360 |

280 |

132 |

149 |

186 |

195 |

210 |

| XI |

619 |

405 |

320 |

152 |

175 |

215 |

225 |

245 |

| XII |

624 |

425 |

345 |

179 |

205 |

230 |

245 |

269 |

Table 3.

Tensile test results.

Table 3.

Tensile test results.

| Sample |

Max. Stress, σ (N/mm2) |

Strain at Max. Stress, ε (%) |

Modulus, E

(N/ mm2) |

| IV-1 |

18.07 |

8.22 |

1056 |

| IV-2 |

17.70 |

7.92 |

1605 |

| IV-3 |

18.07 |

8.59 |

1253 |

| V-1 |

19.23 |

9.19 |

1276 |

| V-2 |

19.41 |

8.43 |

1083 |

| V-3 |

18.51 |

9.20 |

1762 |

| VI-1 |

20.28 |

14.48 |

1416 |

| VI-2 |

20.22 |

12.95 |

1853 |

| VI-3 |

20.26 |

11.57 |

2851 |

| X-1 |

27.18 |

20.30 |

3522 |

| X-2 |

28.52 |

11.61 |

2520 |

| X-3 |

28.79 |

12.42 |

2705 |

| XI-1 |

28.12 |

15.64 |

2962 |

| XI-2 |

27.78 |

15.19 |

5691 |

| XI-3 |

28.86 |

9.84 |

2375 |

| XII-1 |

28.24 |

12.44 |

2901 |

| XII-2 |

28.04 |

15.38 |

2388 |

| XII-3 |

28.52 |

11.94 |

2800 |

Table 4.

Allowed concentration loads.

Table 4.

Allowed concentration loads.

| Sample |

IV |

V |

VI |

X |

XI |

XII |

| ACL with confidence level 10 per drone arm (kg) |

1,59 |

1,67 |

1,78 |

2,48 |

2,50 |

2,70 |

| ACL with confidence level 20 per drone arm (kg) |

1,46 |

1,53 |

1,63 |

2,38 |

2,29 |

2,31 |

| Drone payload capacity with confidence level 10 (kg) |

6.36 |

6.68 |

7.12 |

9.92 |

10 |

10.8 |

| Drone payload capacity with confidence level 20 (kg) |

5.84 |

6.12 |

6.52 |

9.52 |

9.16 |

9.24 |

Table 5.

Drone size classification.

Table 5.

Drone size classification.

| Drone size |

Payload capacity |

Description |

| Mini drones |

≤ 100 g |

Recreational use. |

| Small drones |

100g – 1kg |

Recreational or light commercial tasks |

| Medium drones |

1 – 5 kg |

Professional use (photography, surveying, agricuture) |

| Large drones |

5 – 30 kg |

Industrial use (inspections, cargo transport, etc.) |

| Heavy lift drones |

≥ 30 kg |

Heavy lifting in construction, agriculture or emergency operations |

Table 6.

Preset printing parameter combinations.

Table 6.

Preset printing parameter combinations.

| Designation code |

I |

II |

III |

IV |

V |

VI |

VII |

VIII |

IX |

X |

XI |

XII |

| Layer height [mm] |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

| Wall thickness [mm] |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.6 |

| Wall line contour |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Top layer number |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

| Bottom layer number |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |