Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

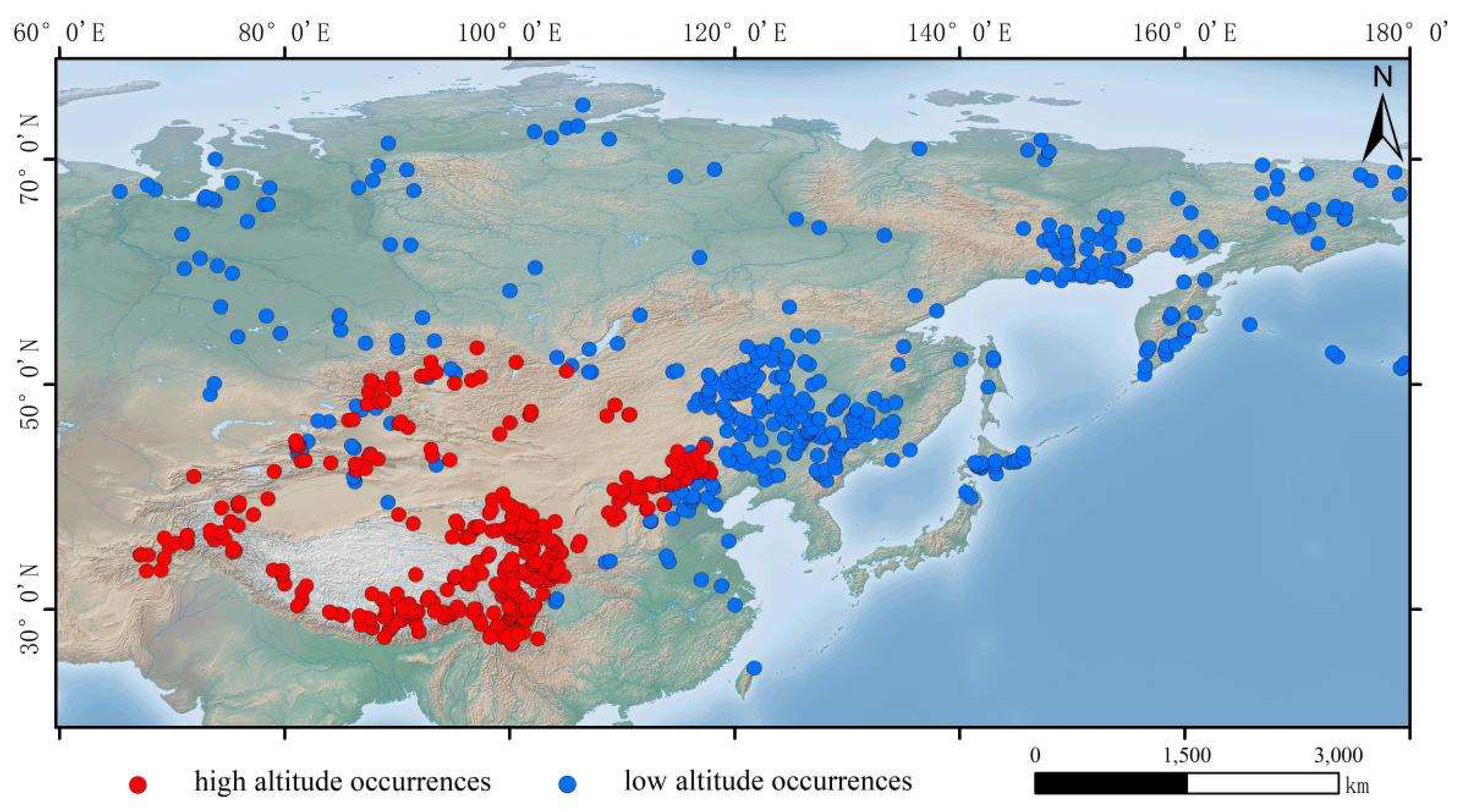

2.1. Collection and Processing of Distribution Records

2.2. Environmental Variable Selection

2.3. Model Optimization and Accuracy Evaluation

2.4. Classification of Suitable Habitat and Centroid Distribution

3. Results

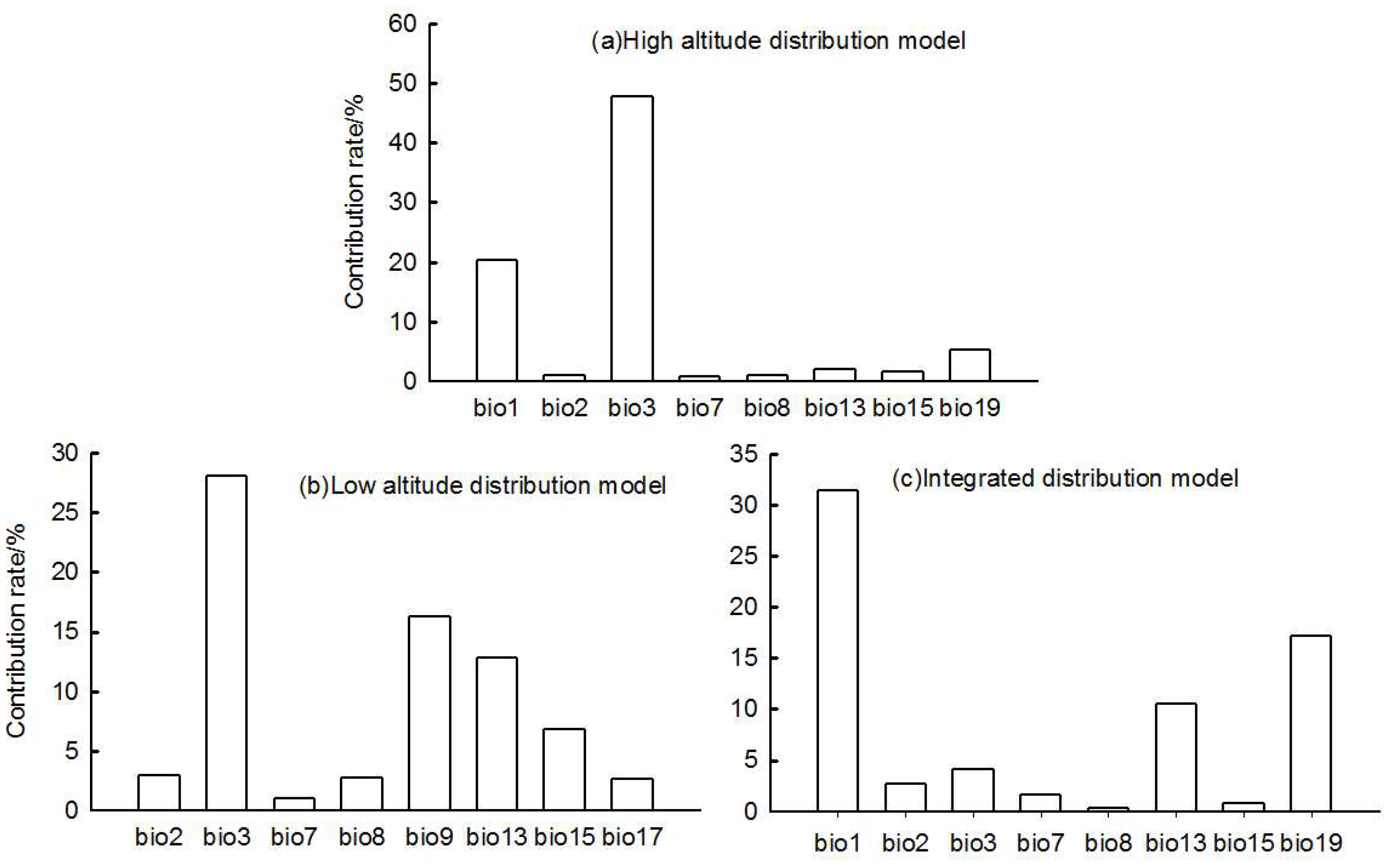

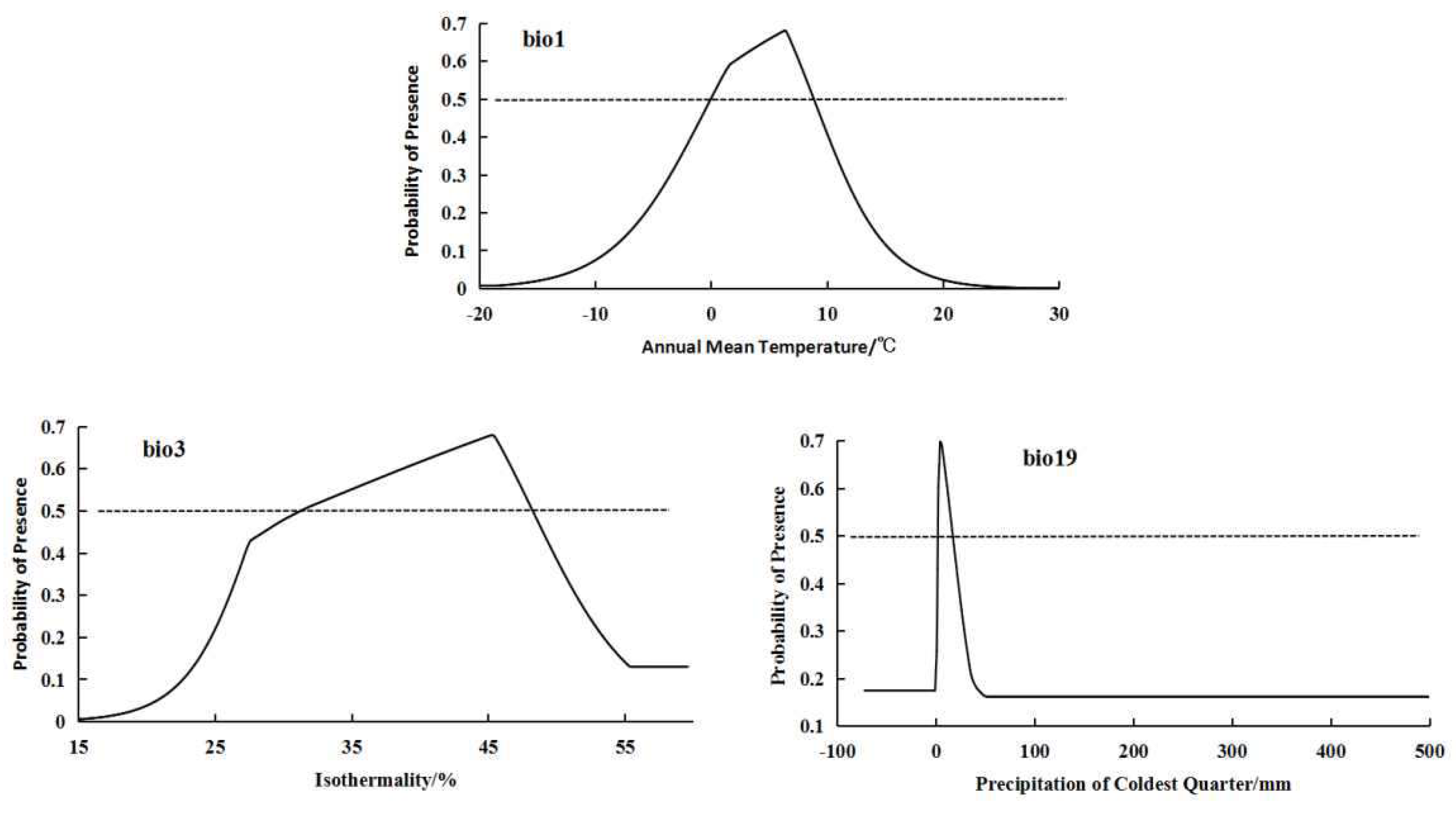

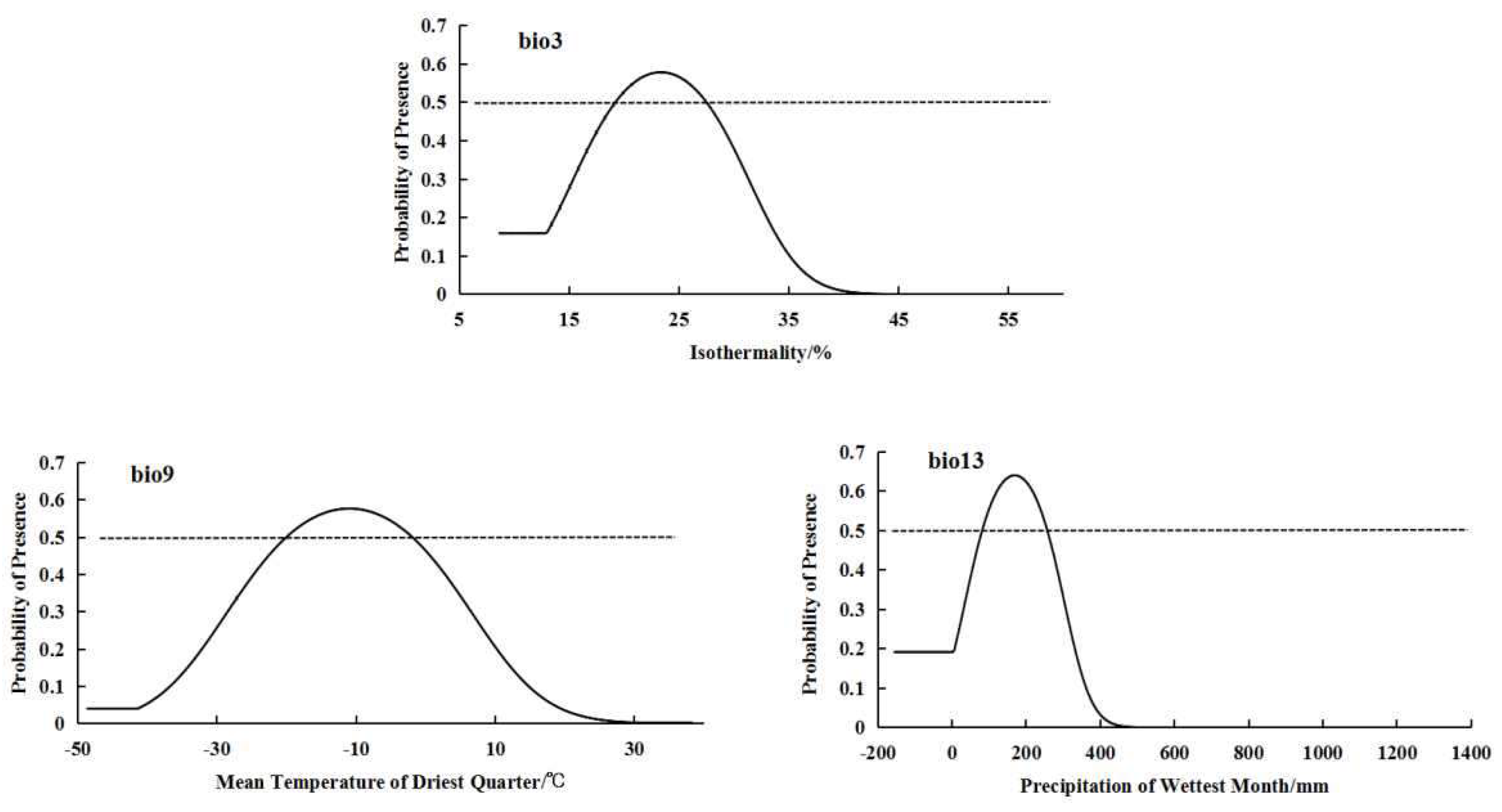

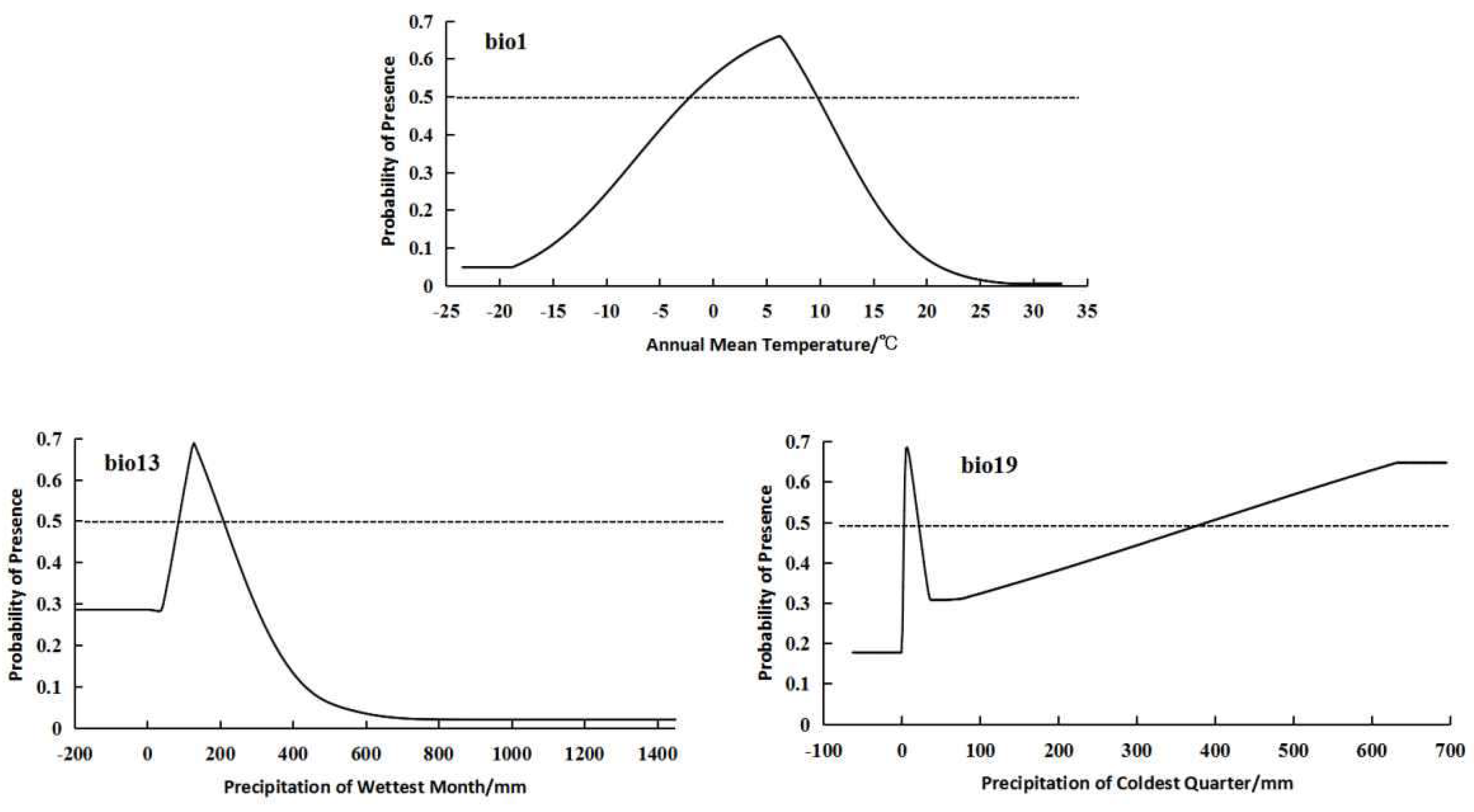

3.1. Model Validation, Dominant bioclimatic variables and Response Curves

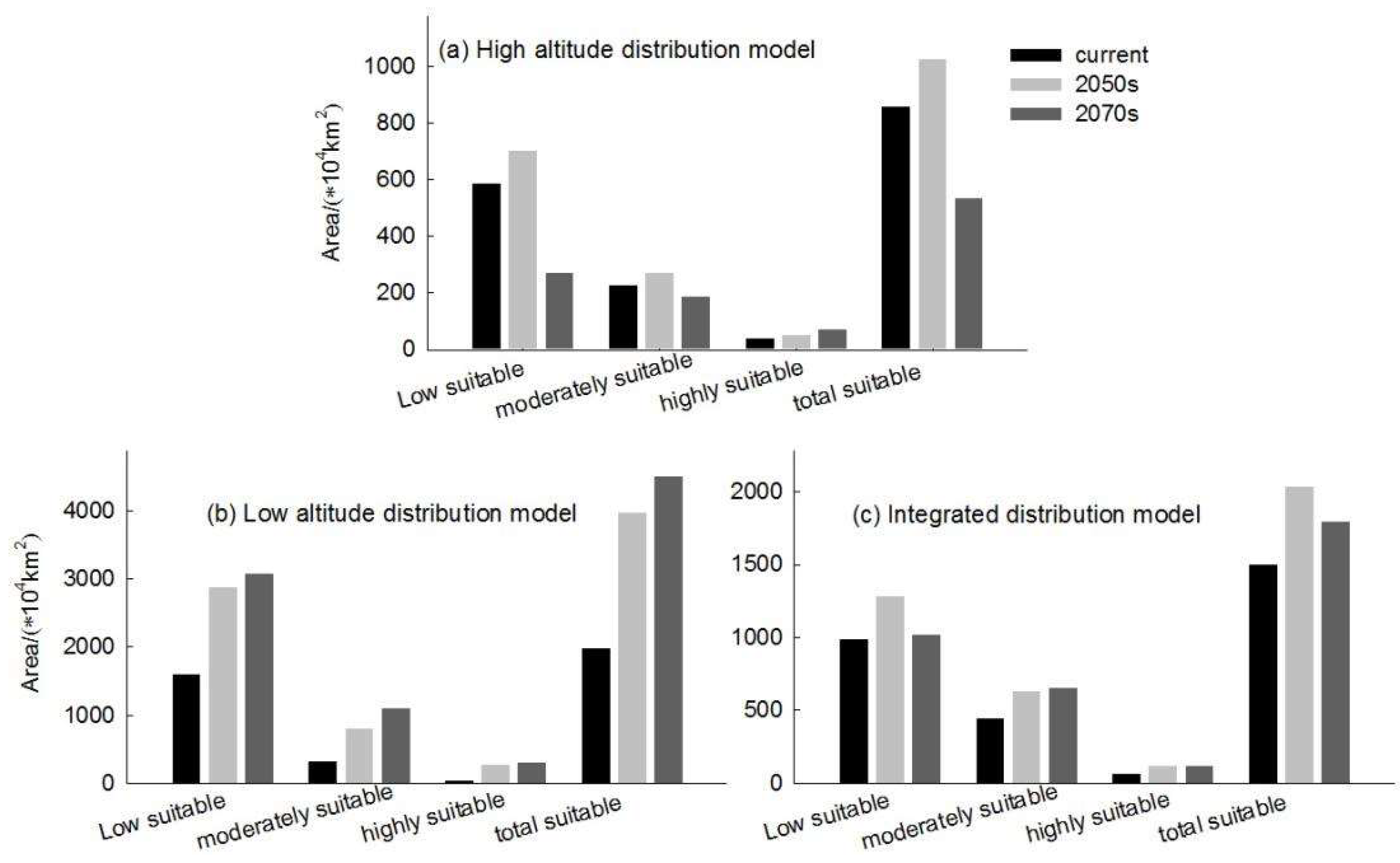

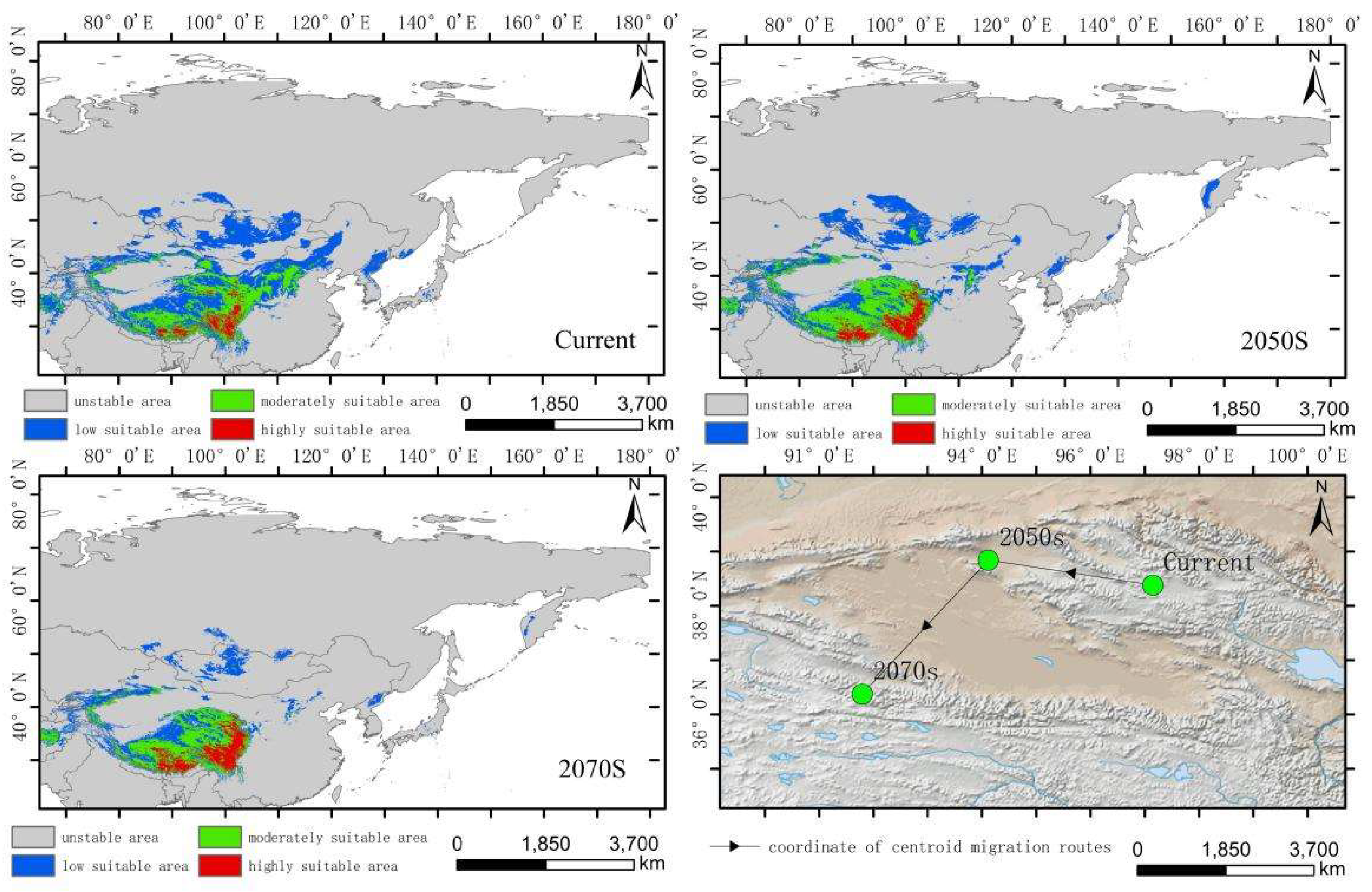

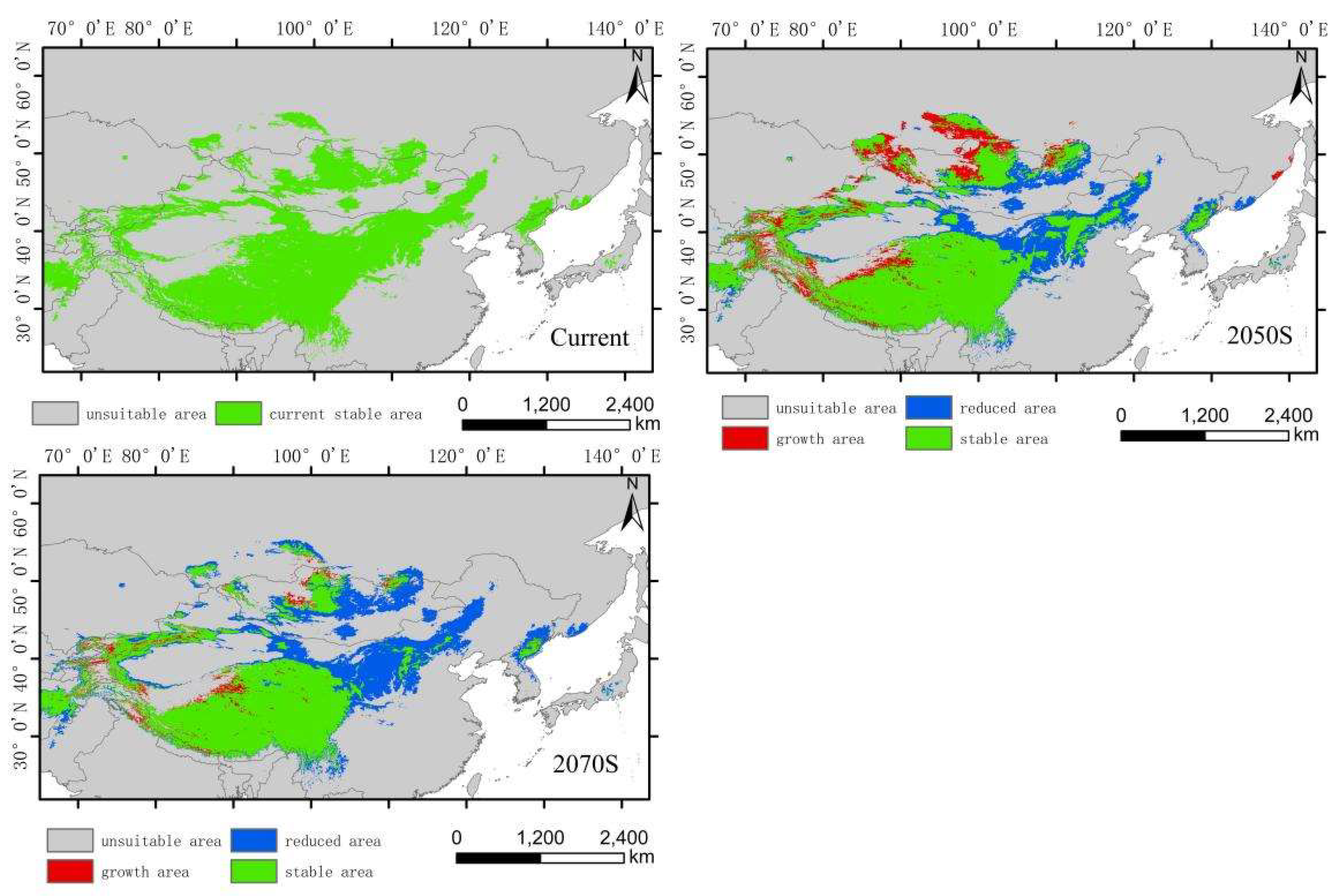

3.2. Distribution and Trends of Potential Suitable habitats

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in Crucial bioclimatic Variables Across Various Models

4.2. Distribution Pattern and Trends of the Suitable Habitat

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woodward, F.I.; Lomas, M.R.; Kelly, C.K. Global climate and the distribution of plant biomes. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 2004, 359, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, R.G.; Dawson, T.P. Predicting the impacts of climate change on the distribution of species: are bioclimate envelope models useful? Global Ecology and Biogeography 2003, 12, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Liu, Q.; Bu, W.; Gao, Y. Ecological niche modeling and its applications in biodiversity conservation. Biodiversity Science 2013, 21, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhya Kiran, G.; Prajapati, P.C.; Mohanta, A. A systematic appraisal of ecological niche modelling in the context of phytodiversity conservation. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.R.; Hamann, A.J.E. Method selection for species distribution modelling: are temporally or spatially independent evaluations necessary? Ecography 2012, 35, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao S L; Zhang X Z; Wang T; et al. Responses and feedback of the Tibetan Plateau’s alpine ecosystem to climate change. Chinese Science Bulletin 2019, 64, 2842–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, H. Advances in the Studies of Responses of Alpine Plants to Global Warming*. Chinese Journal of Appplied Environmental Biology 2012, 17, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmesan, C. Ecological and Evolutionary Responses to Recent Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2006, 37, 637–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Fan, J.; Zhao, Q.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Ding, R.; Gu, R.; Zhong, S. Estimation of habitat suitability and climatic distribution change of Pegaeophyton scapiflorum based on the MaxEnt model. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Science Edition) 2024, 48, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Zeng, J.Y.W.; Qi, D. Prediction of the eographical distribution of Carex moorcroftii under global climate change based on MaxEnt model. Chinese Journal of Grassland 2018, 40, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.-C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D.J.S. Rapid Range Shifts of Species Associated with High Levels of Climate Warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, G.-R.; Post, E.; Convey, P.; Menzel, A.; Parmesan, C.; Beebee, T.J.C.; Fromentin, J.-M.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Bairlein, F. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 2002, 416, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Fu, Q.-L.; Jacquemyn, H.; Burgess, K.S.; Cheng, J.-J.; Mo, Z.-Q.; Tang, X.-D.; Yang, B.-Y.; Tan, S.-L. Contrasting range changes of Bergenia (Saxifragaceae) species under future climate change in the Himalaya and Hengduan Mountains Region. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2023, 155, 1927–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.K.; Hamann, A. Strategies for Reforestation under Uncertain Future Climates: Guidelines for Alberta, Canada. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e22977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albach, D.C.; Meudt, H.M.; Oxelman, B. Piecing Together the “New” Plantaginaceae. American Journal of Botany 2005, 92, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Flora of China; Science Press: Beijing, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. The Geography of aquatic vascular plants of Qinghai-Xizang(Tibet) Plateau. Doctor, Wuhan University, 2003.

- Chen, J.; Du, Z.-Y.; Sun, S.-S.; Gituru, R.; Wang, Q.-F. Chloroplast DNA Phylogeography Reveals Repeated Range Expansion in a Widespread Aquatic Herb Hippuris vulgaris in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and Adjacent Areas. PloS one 2013, 8, e60948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; García-Girón, J.; Iversen, L.L. Global change and plant-ecosystem functioning in freshwaters. Trends in Plant Science 2023, 28, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Tao, C.; Miao, X.; Wang, D.; Tang, m.; Da, w.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Pan, H. Ethno-veterinary survey of medicinal plants in Ruoergai region, Sichuan province, China. Ethnopharmacol 2012, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.X.; Zhu, J.; Yu, D.; Xu, X. Genetic and geographical structure of boreal plants in their southern range: phylogeography of Hippuris vulgaris in China. BMC Evol Biol 2016, 16, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rixen, C.; Wipf, S.; Rumpf, S.B.; Giejsztowt, J.; Millen, J.; Morgan, J.W.; Nicotra, A.B.; Venn, S.; Zong, S.; Dickinson, K.J.M.; et al. Intraspecific trait variation in alpine plants relates to their elevational distribution. Journal of Ecology 2022, 110, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, S.; MO, S.; HU, X.; DENG, T. Prediction of potential suitable areas of endangered plant Abies ziyuanensis based on MaxEnt and ArcGIS. Chinese journal of Ecology 2024, 43, 533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, J.M.; Vilela, B.; Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Muscarella, R.; Merow, C.; Anderson, R.P. Wallace: A flexible platform for reproducible modeling of species niches and distributions built for community expansion. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2018, 9, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, M.G.; Ganio, L.M.; Huso, M.M.P.; Som, N.A.; Huettmann, F.; Bowman, J.; Wintle, B.A. Comment on “Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: a review”. Ecography 2009, 32, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, g.; Liu, q.; Gao, Y. Improving ecological niche model transferability to predict the potential distribution of invasive exotic species. Biodiversity Science 2014, 22, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, C.; Simpson, N.; Johnson, F.; Birt, A. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report (Full Volume) Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2023.

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, H.X.; Wang, H. Potential geographical distribution of populus euphratica in China under future climate change scenarios based on Maxent model. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2020, 40, 6552–6563. [Google Scholar]

- K, Y.W.; Y, L.; L, W.; Y, Z.X.; Q, L. Effects of artificial introduction and climate change on the future distribution of Cyanopica cyanus. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2023, 43, 10387–10398. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.L., Xinhai; Zou, H. Optimizing MaxEnt model in the prediction of species distribution. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2019, 30, 2116–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X. Prediction of Historical, Current, and Future Configuration of Tibetan Medicinal Herb Gymnadenia orchidis Based on the Optimized MaxEnt in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Plants 2024, 13, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240 4857, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Guo, C.; Dong, W.; Zhao, L.; Liu, D. Changes in the Suitable Habitat of the Smoke Tree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.), a Species with an East Asian–Tethyan Disjunction. Plants 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-g.; Le, X.-g.; Chen, Y.-h.; Cheng, W.-x.; Du, J.-g.; Zhong, Q.-l.; Cheng, D.-l. Identification of the potential distribution area of Cunninghamia lanceolata in China under climate change based on the MaxEnt model. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2022, 33, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Yao, W.; Wang, Z.; Fan, X.; Hu, S.; Wang, H.; Ou, J. Predicting Potential Suitable Habitats of Three Rare Wild Magnoliaceae Species (Michelia crassipes, Lirianthe coco, Manglietia insignis) Under Current and Future Climatic Scenarios Based on the Maxent Model. Plants 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Yuan, G.; Li, W.; Ge, D.; Zou, D.; Huang, Z. Environmental effects on community productivity of aquatic macrophytes are mediated by species and functional composition. Ecohydrology 2019, 12, e2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Su, Y.L.; Luo, Y.Y.; Sun, Z.L.; Xiong, M.; Zhou, L.Y. Prediction of suitable Solanum rostratum growth areas in Horqin Sandy Land based on the Maximum Entropy Model. Pratacultural Science 2024, 41, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.H.; Longzhu, D.J.; Lu, X.W.; Songzha, C.; Miao, Q.; Sun, F.H.; Suonan, J. Habitat suitability of Corydalis based on the optimized MaxEnt model in China. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2023, 43, 10345–10362. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.K.M., Y L; Zhu, G.P. Impact of global climate change on potential distributions of Alternanthera philoxeroides and Agasicles hygrophila. Journal of Tianjin Normal University(Natural Science Edition) 2023, 43, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D. Study on the dynamics and succession of aquatic macrophyte communities in the Zhushun Lake, Harbin. Acta Phytoecologica Sinica 1994, 18, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, Y.; Yabe, K.; Katagiri, K. Factors controlling changes in the aquatic macrophyte communities from 1984 to 2009 in a pond in the cool-temperate zone of Japan. Limnology 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigdel, S.R.; Zheng, X.; Babst, F.; Camarero, J.J.; Gao, S.; Li, X.; Lu, X.; Pandey, J.; Dawadi, B.; Sun, J.; et al. Accelerated succession in Himalayan alpine treelines under climatic warming. Nature Plants 2024, 10, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Shen, C.; Tao, Z.; Qin, W.; Huang, W.; Siemann, E. Deterministic responses of biodiversity to climate change through exotic species invasions. Nature Plants 2024, 10, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gao, Q.-B.; Guo, W.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Ma, X.-L.; Zhang, F.-Q.; Chen, S.-L. Impacts of human activities and environmental factors on potential distribution of Swertia przewalskii Pissjauk., an endemic plant in Qing-Tibetan Plateau, using MaxEnt. Plant Science Journal 2021, 39, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- VanDerWal, J.; Murphy, H.T.; Kutt, A.S.; Perkins, G.C.; Bateman, B.L.; Perry, J.J.; Reside, A.E. Focus on poleward shifts in species’ distribution underestimates the fingerprint of climate change. Nature Climate Change 2013, 3, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Lenoir, J.; Shrestha, N.; Lyu, T.; Luo, A.; Li, Y.; Ji, C.; Peng, S.; et al. Upward shift and elevational range contractions of subtropical mountain plants in response to climate change. The Science of the total environment 2021, 783, 146896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HU, Z.-j.; ZHANG, Y.-l.; Yu, H.-b. Simulation of Stipa purpurea distribution pattern on Tibetan Plateau based on MaxEnt model and GIS. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2015, 26, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, N.; Naudiyal, N.; Wang, J.N.; Gaire, N.P.; Wu, Y.; Wei, Y.Q.; He, J.L.; Wang, C.Y. Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Potential Distribution of Meconopsis punicea and Its Influence on Ecosystem Services Supply in the Southeastern Margin of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. FRONTIERS IN PLANT SCIENCE 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenoir, J.; Gegout, J.C.; Marquet, P.A.; Ruffray, P.D.; Brisse, H.J.S. A significant upward shift in plant species optimum elevation during the 20th century. Science 2008, 320, 1768–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antão, L.H.; Weigel, B.; Strona, G.; Hällfors, M.; Kaarlejärvi, E.; Dallas, T.; Opedal, Ø.H.; Heliölä, J.; Henttonen, H.; Huitu, O.; et al. Climate change reshuffles northern species within their niches. Nature Climate Change 2022, 12, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pineda-Munoz, S.; McGuire, J.L. Plants maintain climate fidelity in the face of dynamic climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2201946119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Guan, B.; Lai, L.; Yang, Q.; Chen, X. Recent decade expansion of aquatic vegetation covering in china’s lakes. Ecological Indicators 2024, 159, 111603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Du, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Y. Meteorological Droughts in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau:Research Progress and Prospects. Advances in Earth Science 2022, 37, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Hou, X.; Feng, L.; Pi, X.; Kyzivat, E.D.; Zhang, Y.; Woodman, S.G.; Tang, L.; Cheng, X.; et al. Expansion of aquatic vegetation in northern lakes amplified methane emissions. Nature Geoscience 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fu, Z.; Xiao, K.; Dong, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhan, Q. Climate Change Potentially Leads to Habitat Expansion and Increases the Invasion Risk of Hydrocharis (Hydrocharitaceae). Plants 2023, 12, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillard, M.; Thiebaut, G.; Deleu, C.; Leroy, B. Present and future distribution of three aquatic plants taxa across the world: decrease in native and increase in invasive ranges. Biological Invasions 2017, 19, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Piao, S.; Myneni, R.B.; Huang, M.; Zeng, Z.; Canadell, J.G.; Ciais, P.; Sitch, S.; Friedlingstein, P.; Arneth, A.; et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nature Climate Change 2016, 6, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environment variables | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| bio1 | Annual Mean Temperature | ℃ |

| bio2 | Mean Diurnal Range(Mean of monthly(max temp - min temp)) | ℃ |

| bio3 | Isothermality | % |

| bio4 | Temperature Seasonality | - |

| bio5 | Max Temperature of Warmest Month | ℃ |

| bio6 | Min Temperature of Coldest Month | ℃ |

| bio7 | Temperature Annual Range | ℃ |

| bio8 | Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter | ℃ |

| bio9 | Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter | ℃ |

| bio10 | Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter | ℃ |

| bio11 | Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter | ℃ |

| bio12 | Annual Precipitation | mm |

| bio13 | Precipitation of Wettest Month | mm |

| bio14 | Precipitation of Driest Month | mm |

| bio15 | Precipitation Seasonality(Coefficient of Variation) | - |

| bio16 | Precipitation of Wettest Quarter | mm |

| bio17 | Precipitation of Driest Quarter | mm |

| bio18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter | mm |

| bio19 | Precipitation of Coldest Quarter | mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).