Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

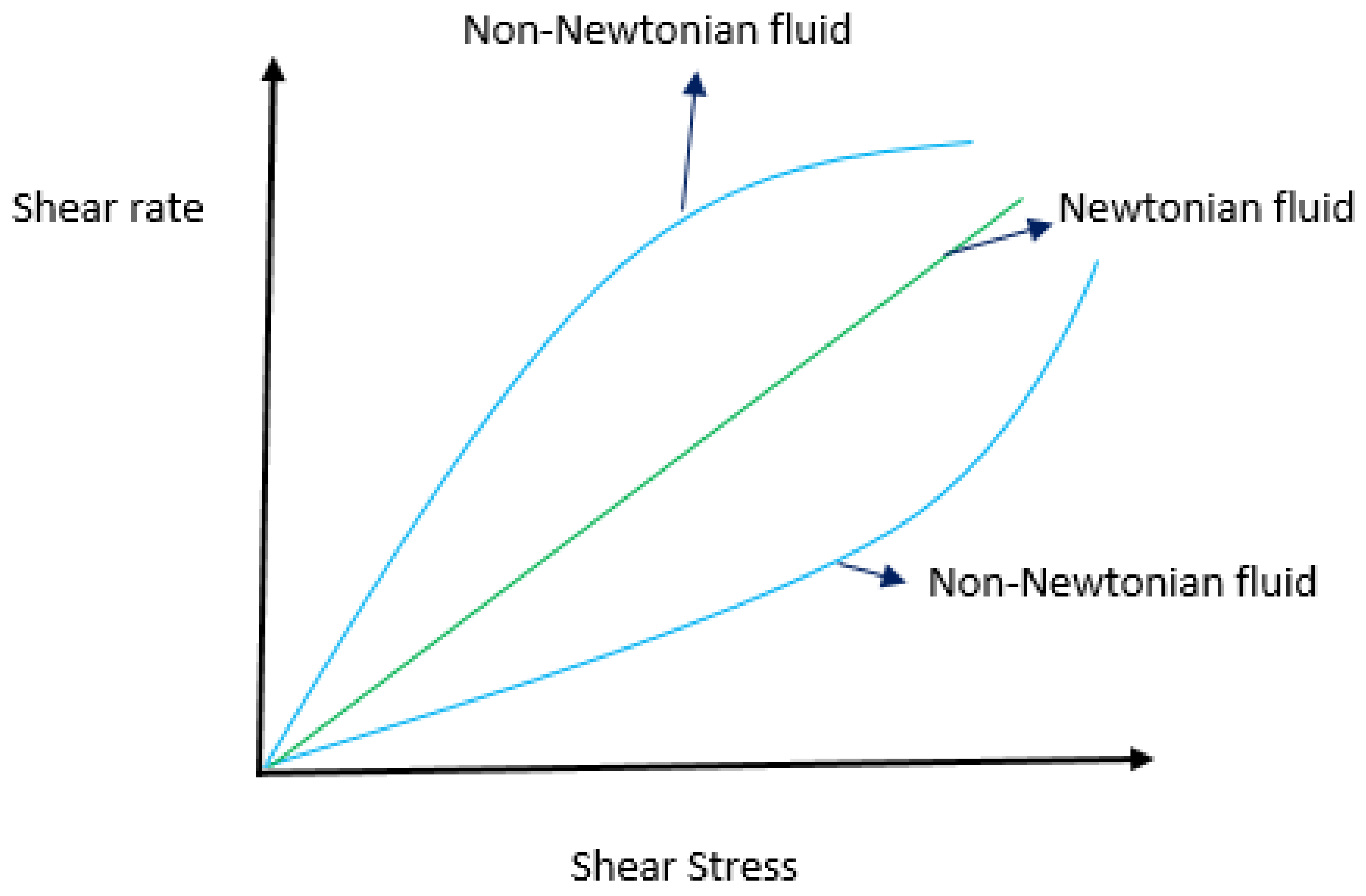

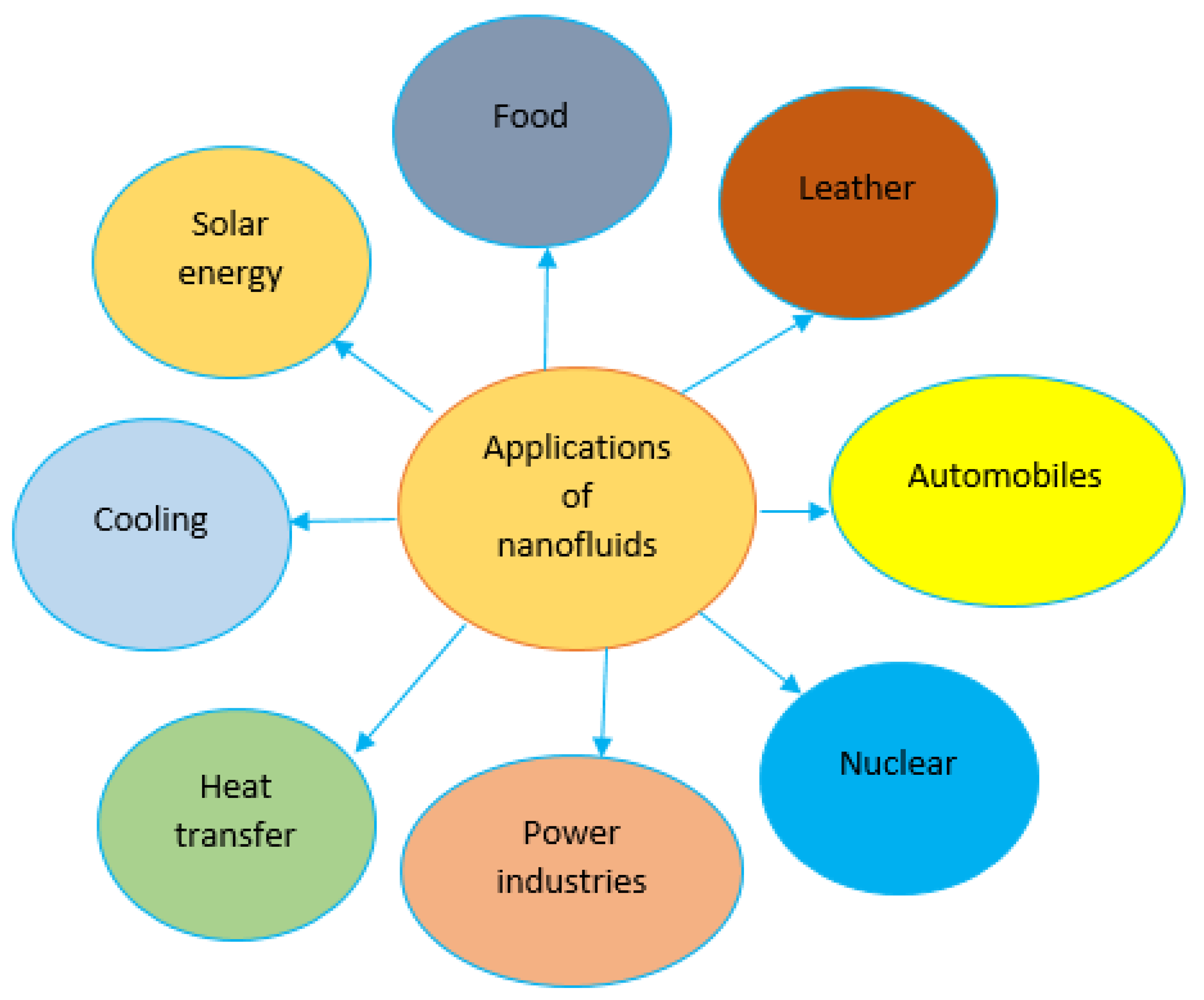

1. Introduction

1.1. Novelty

- What is the behavior of swimming microorganisms in Eyring-Powell nanofluid?

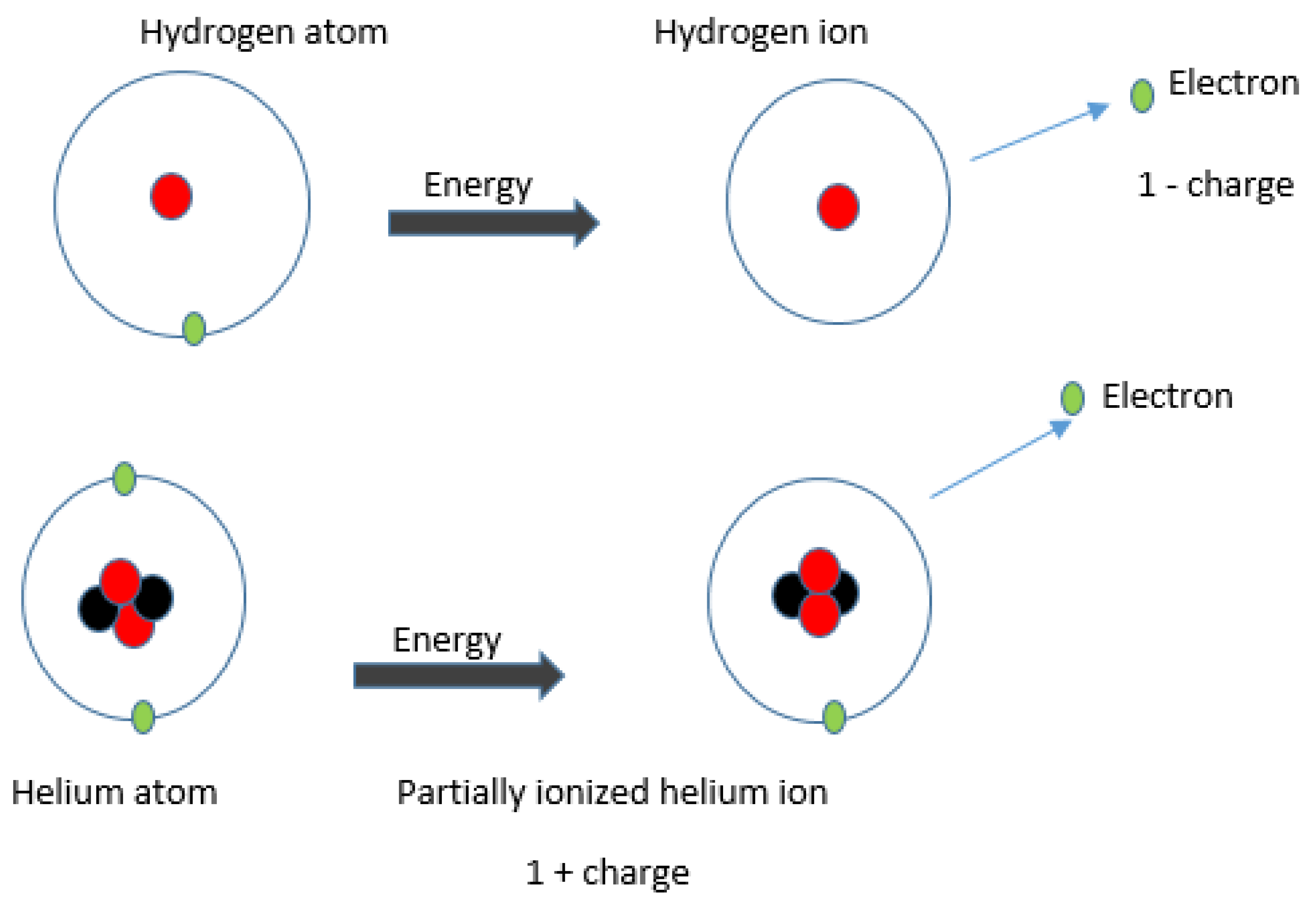

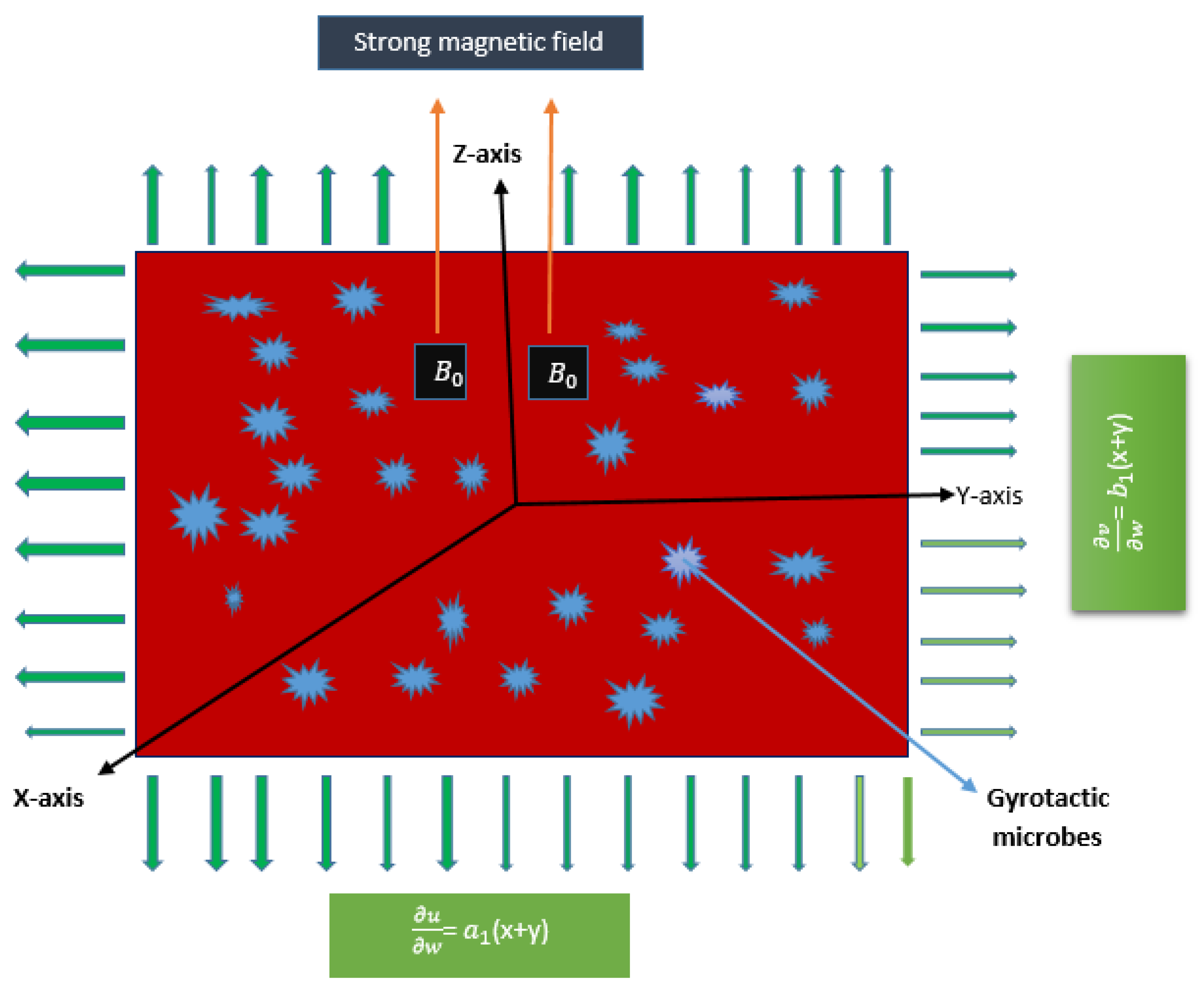

- How can a magnetic field, Hall, and ion slip traits affect the dynamics of liquid velocity?

- In what way are the gyrotactic bacteria and nanoparticles distributed in three-dimensional Eyring-Powell nanofluid flow?

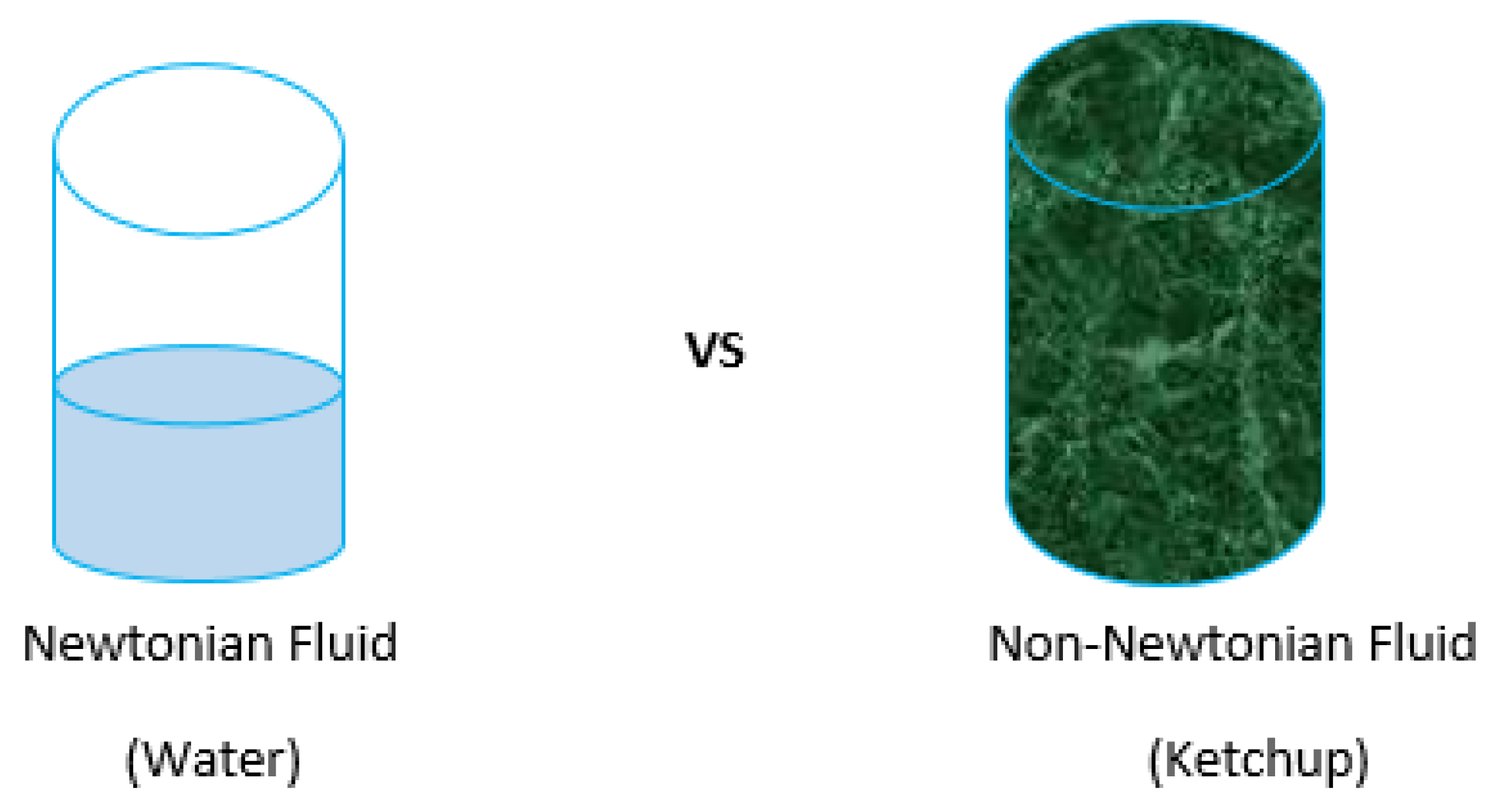

1.2. Governing Equations

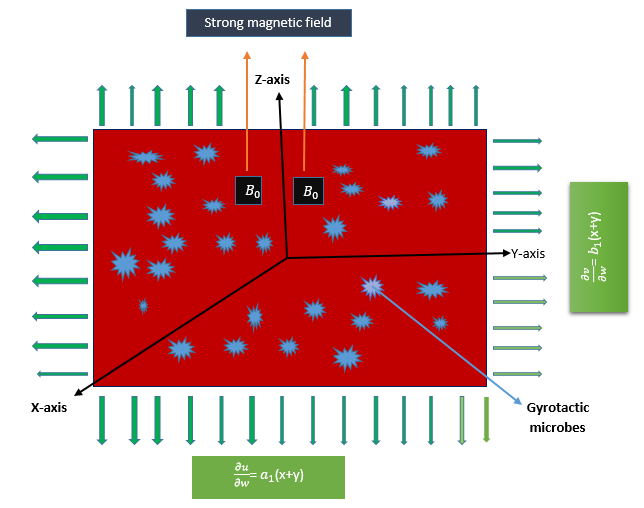

1.3. Physical Description of the Problem

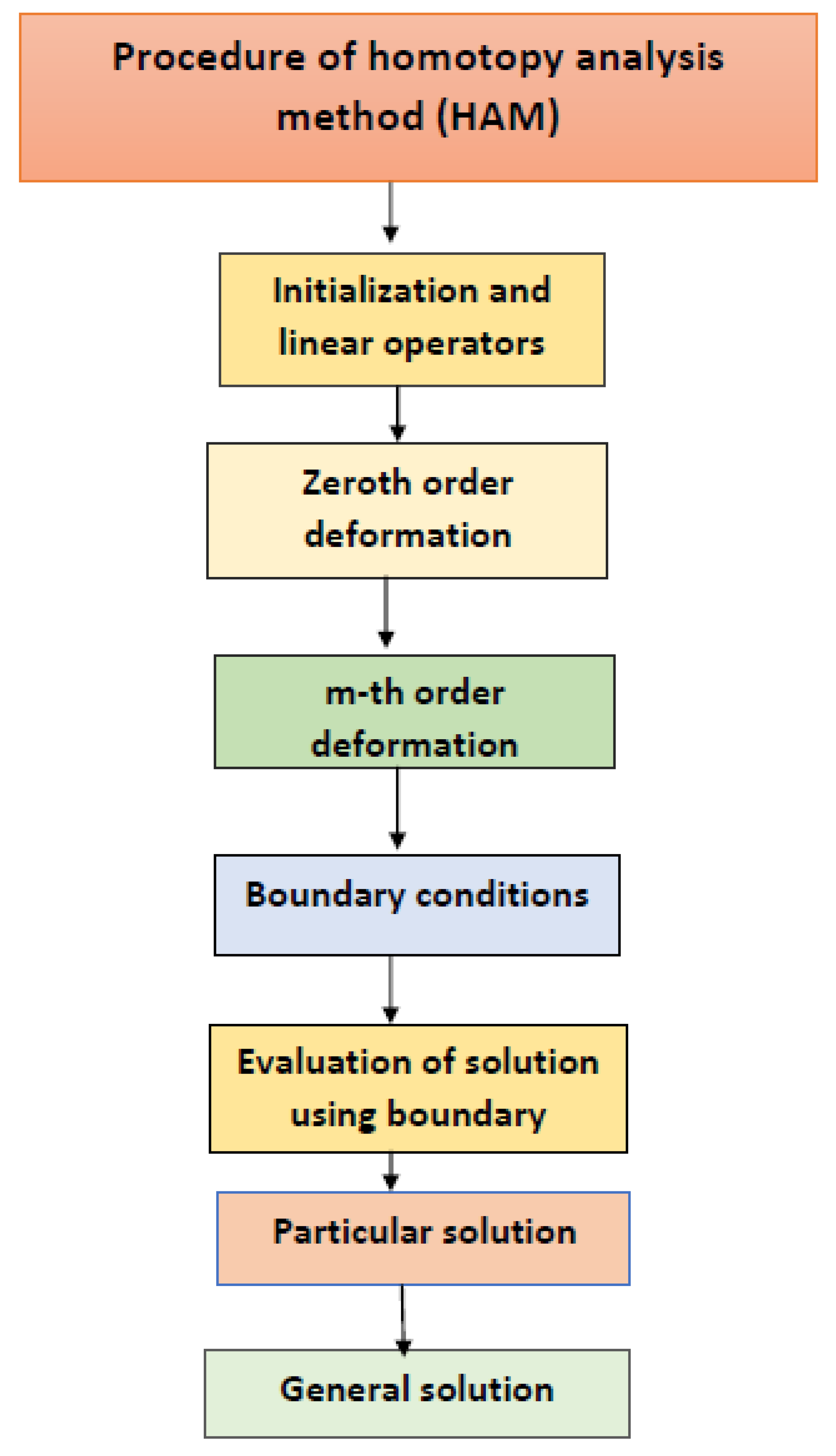

2. Solution of the problem by HAM

- The convergence solution to the issue at hand is found using this strategy.

- There are no calculations or measurement errors in the HAM.

- There are no baseline units or operators for linearity used in this procedure.

- HAM can be used with both large and small variable schemes.

- This technique can be used for settings with stronger or lower fundamental constants.

2.1. Deformation Equations of Zeroth Order

2.2. m-th Order Deformation Problems

3. Results and Discussion

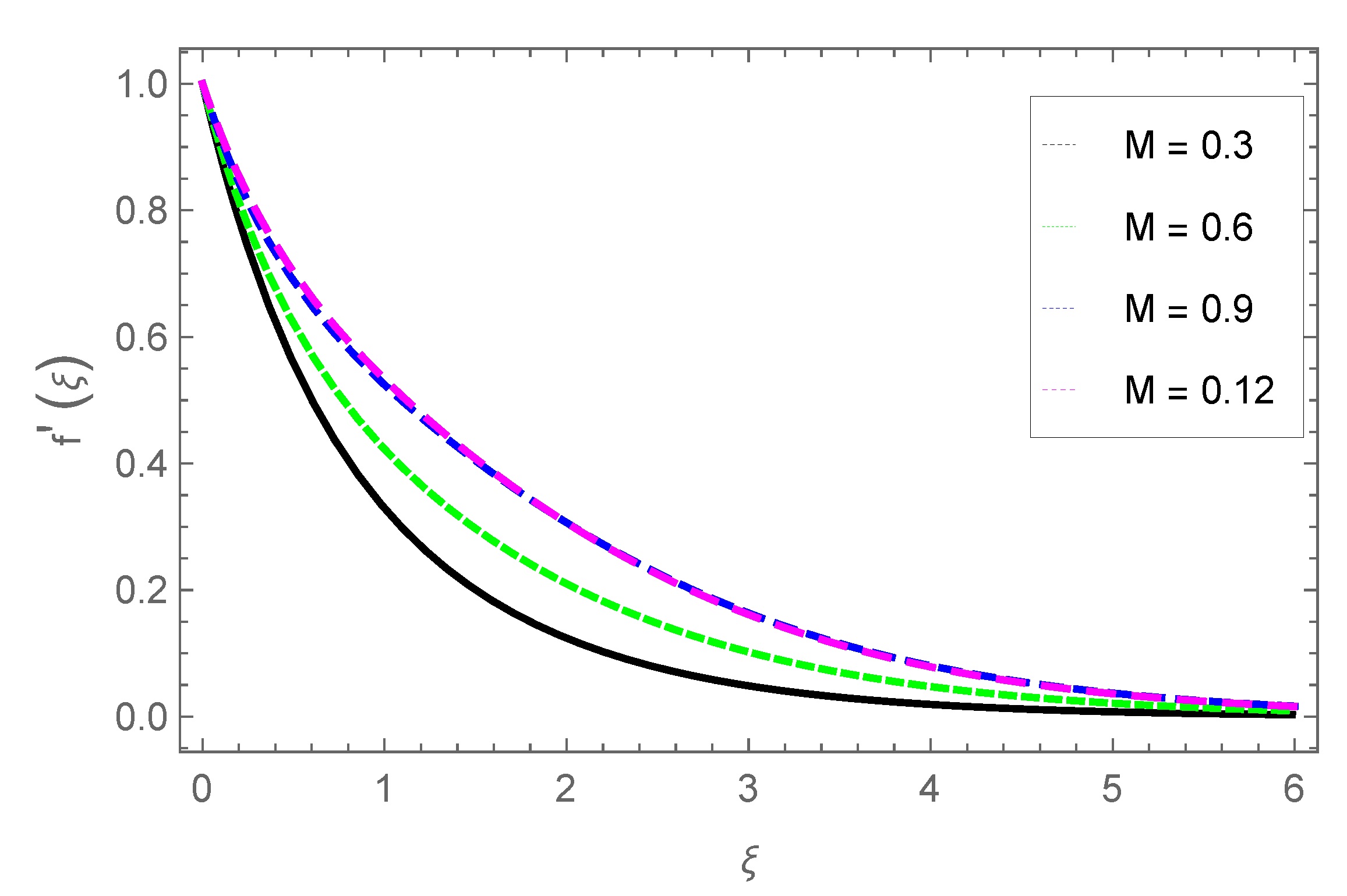

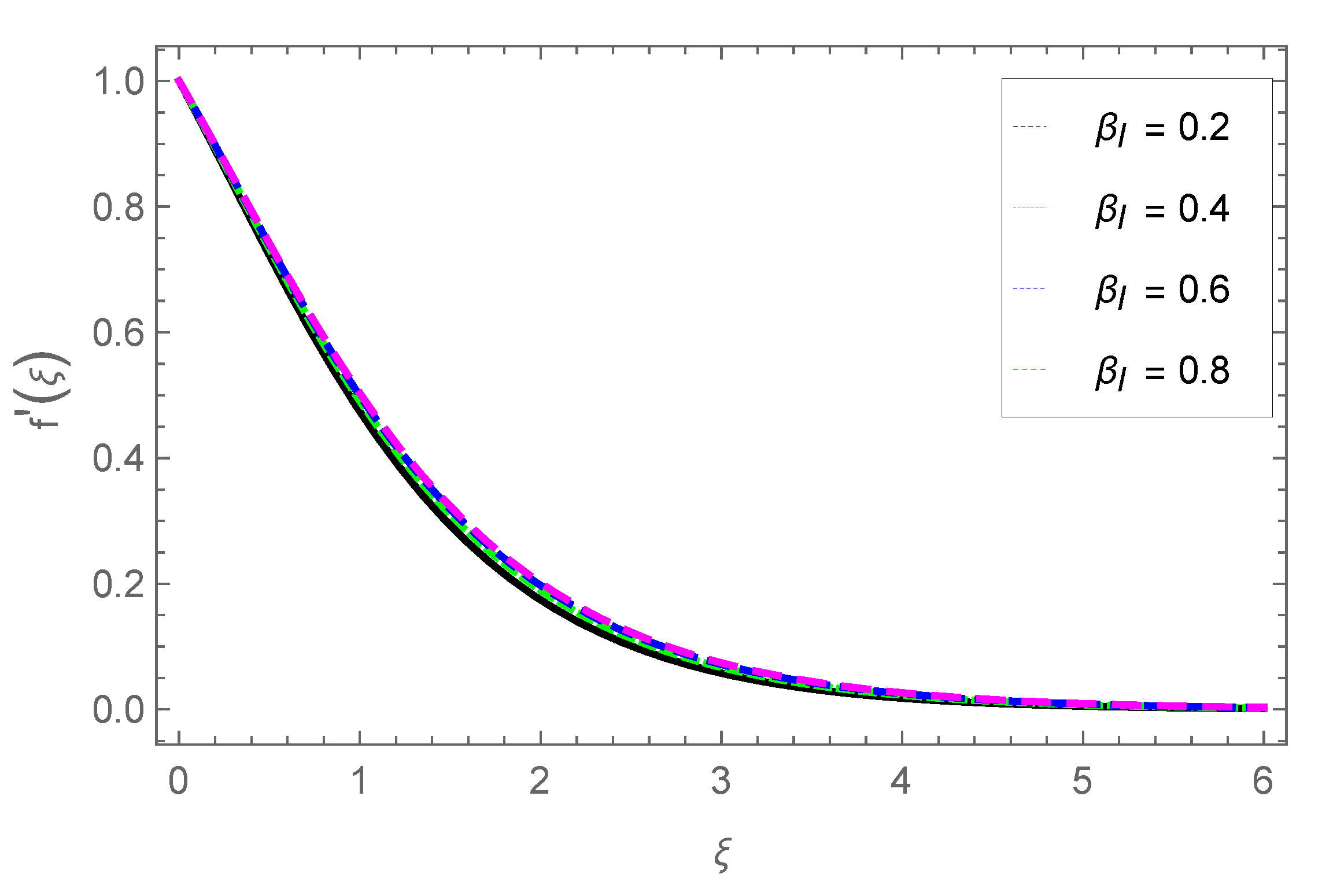

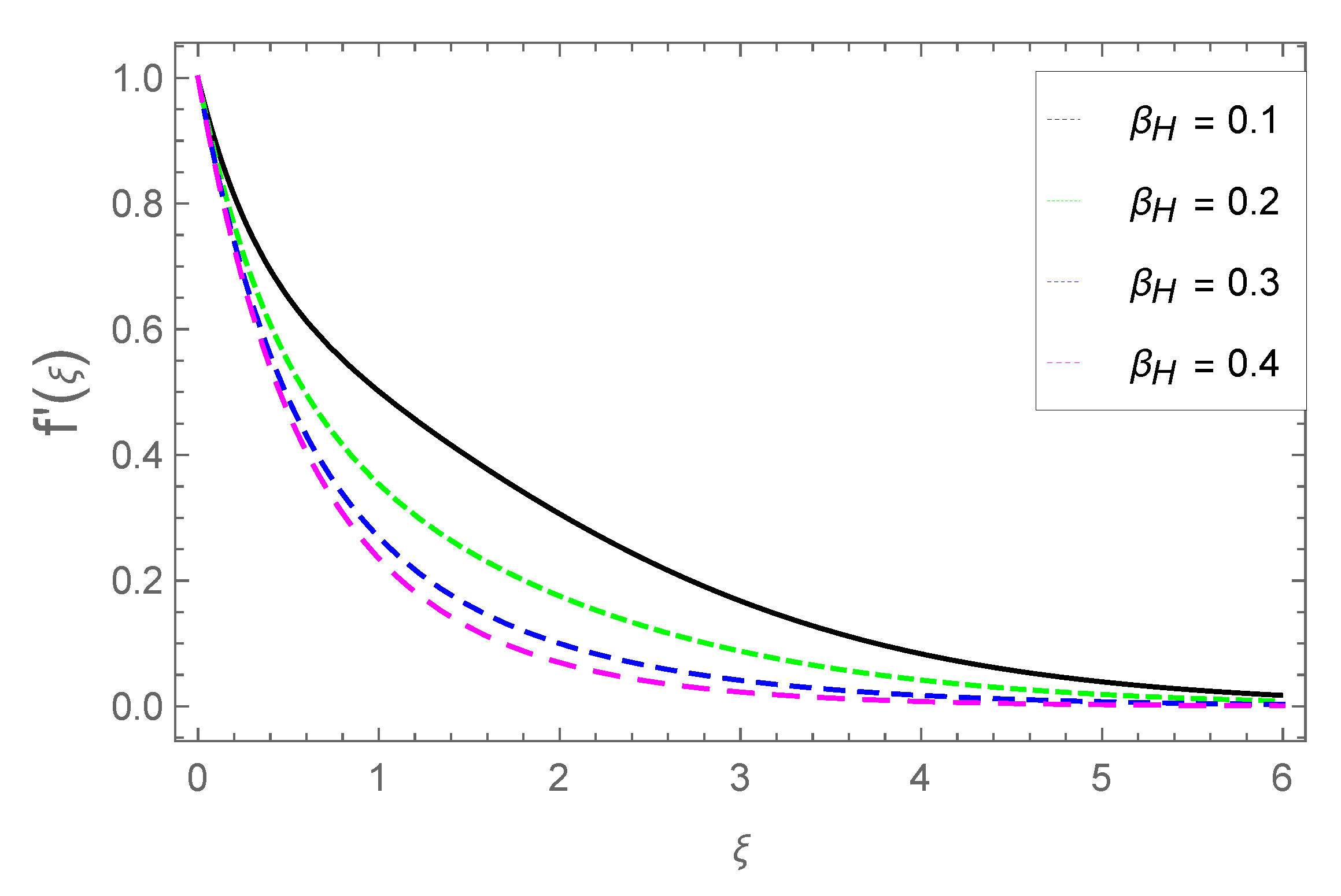

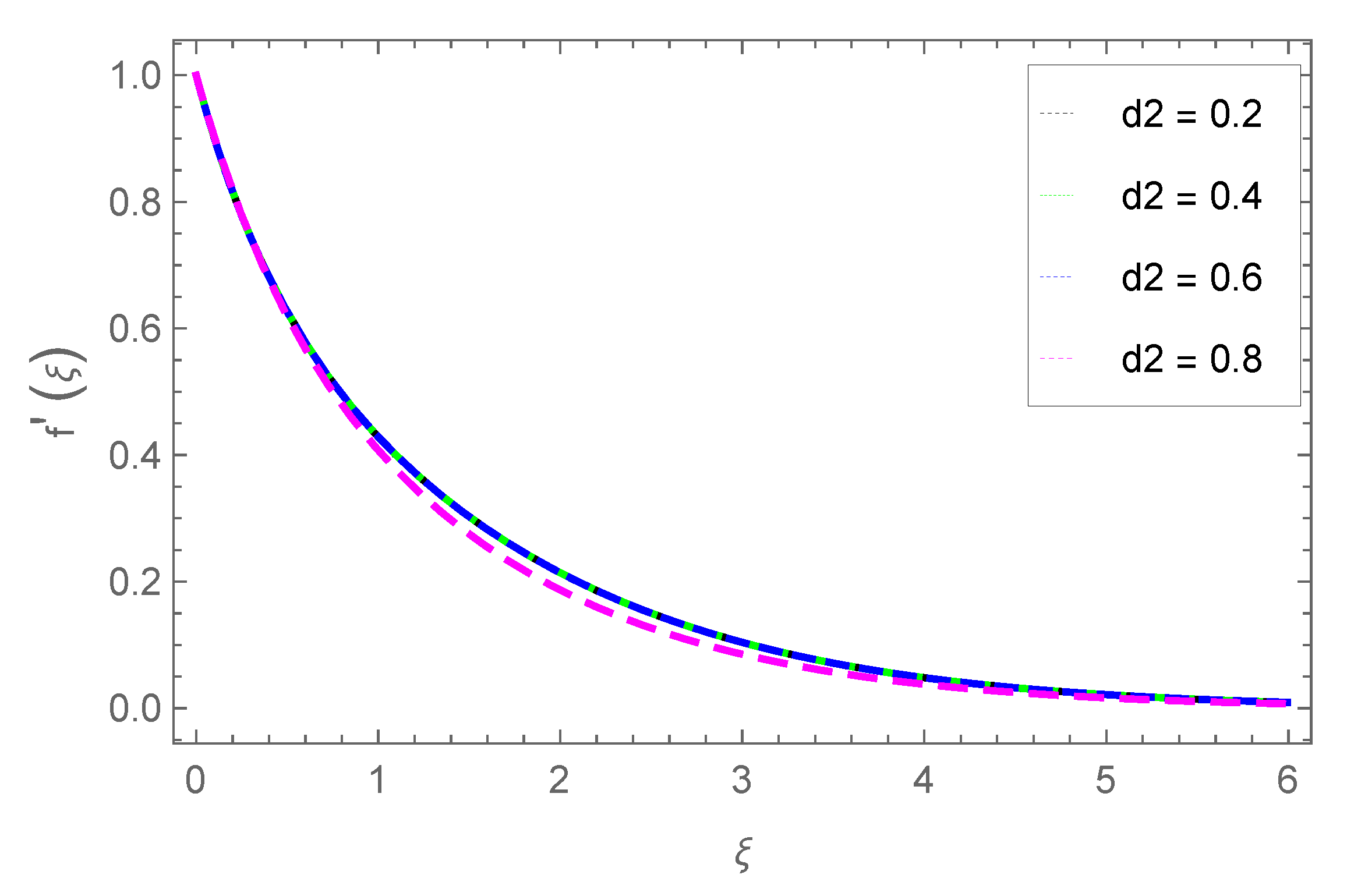

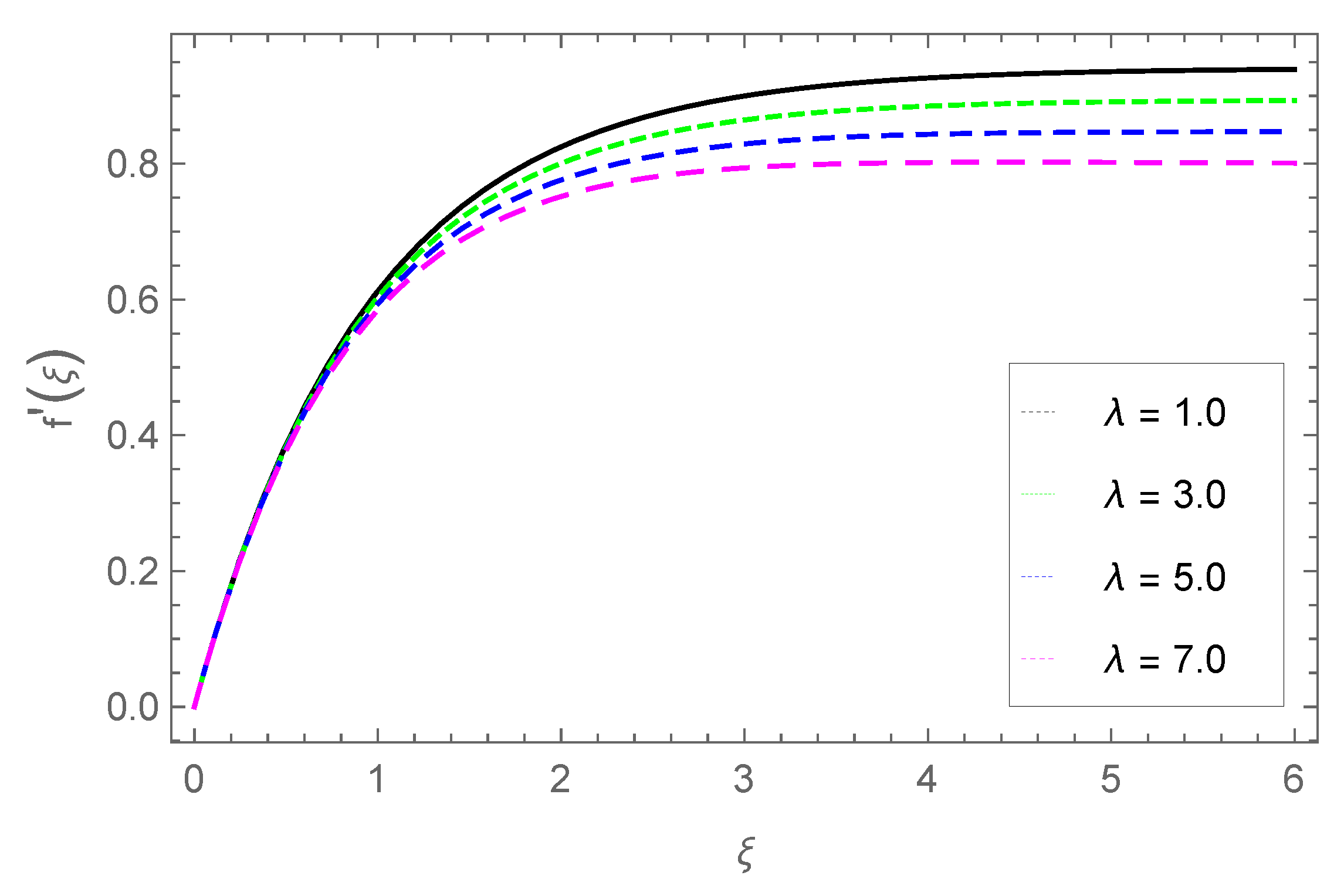

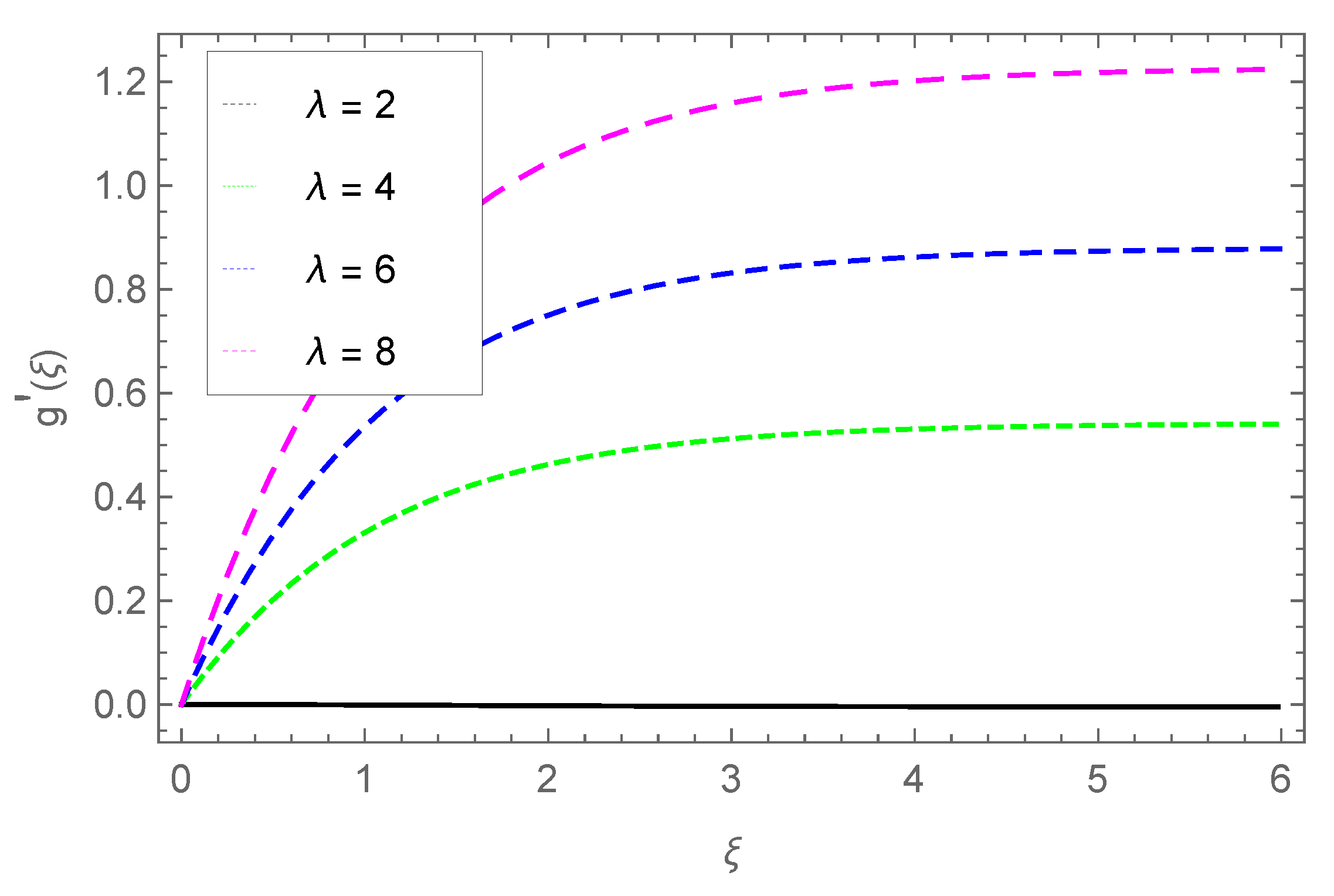

3.1. Radial Velocity Profile

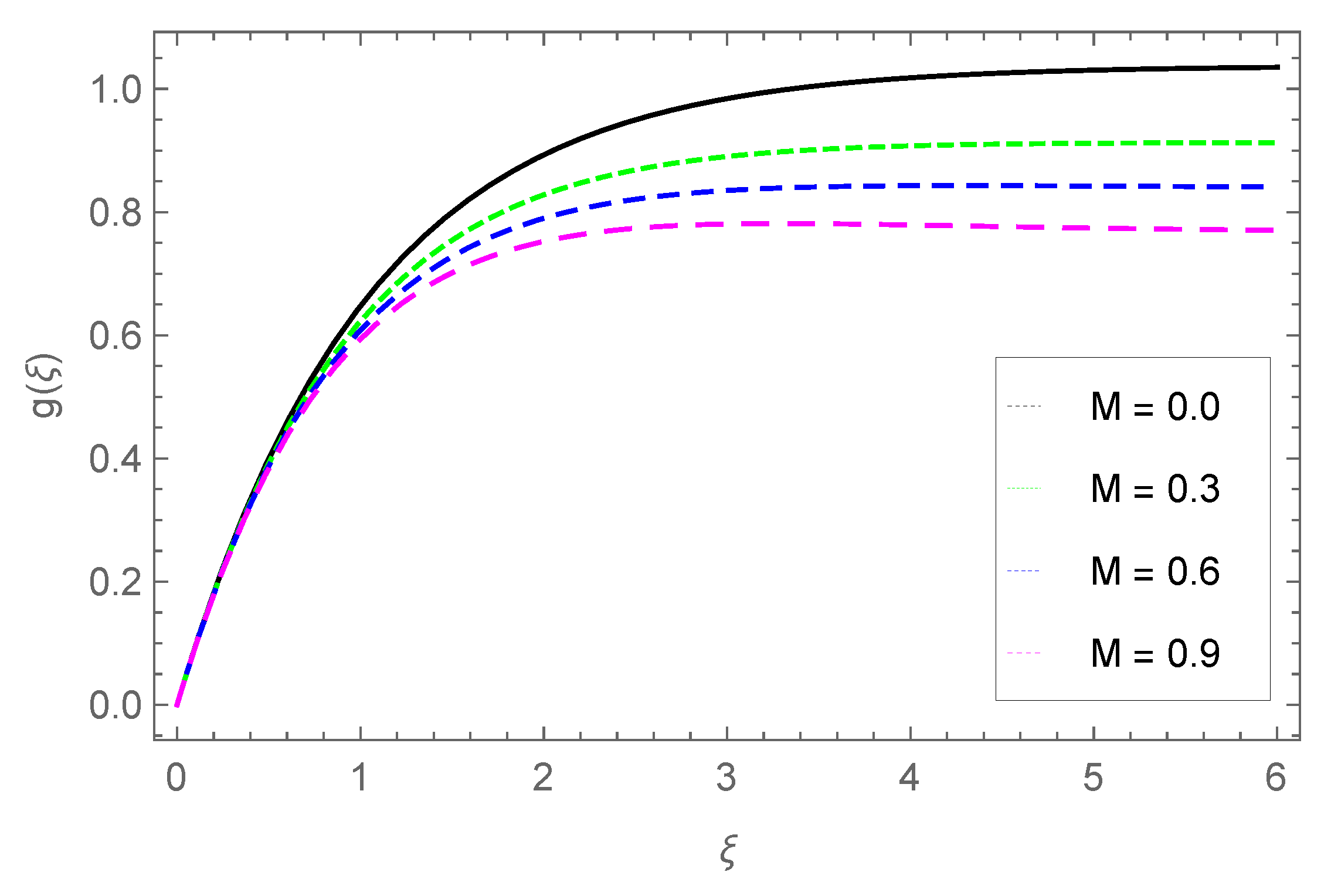

3.2. Transverse Velocity Profile

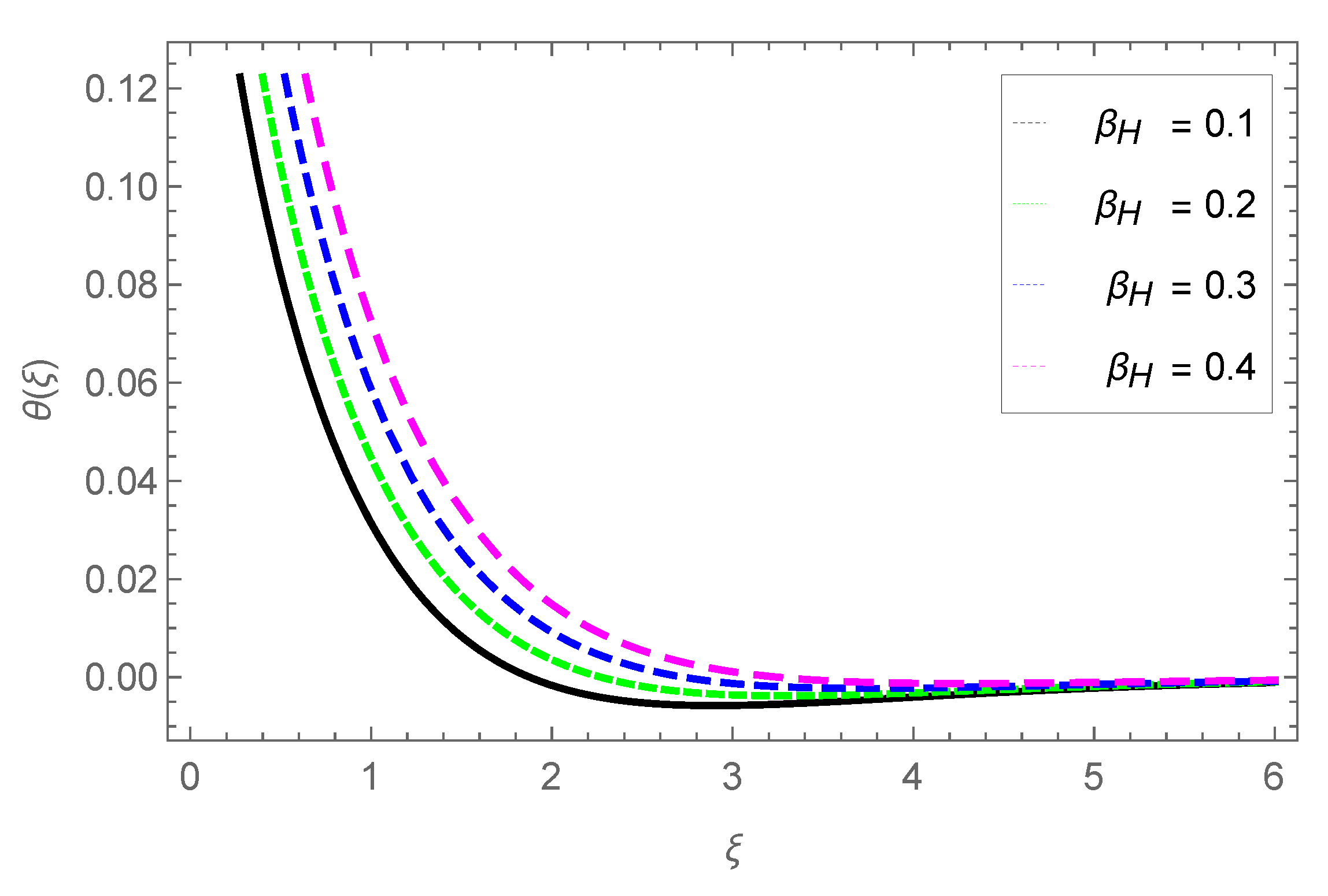

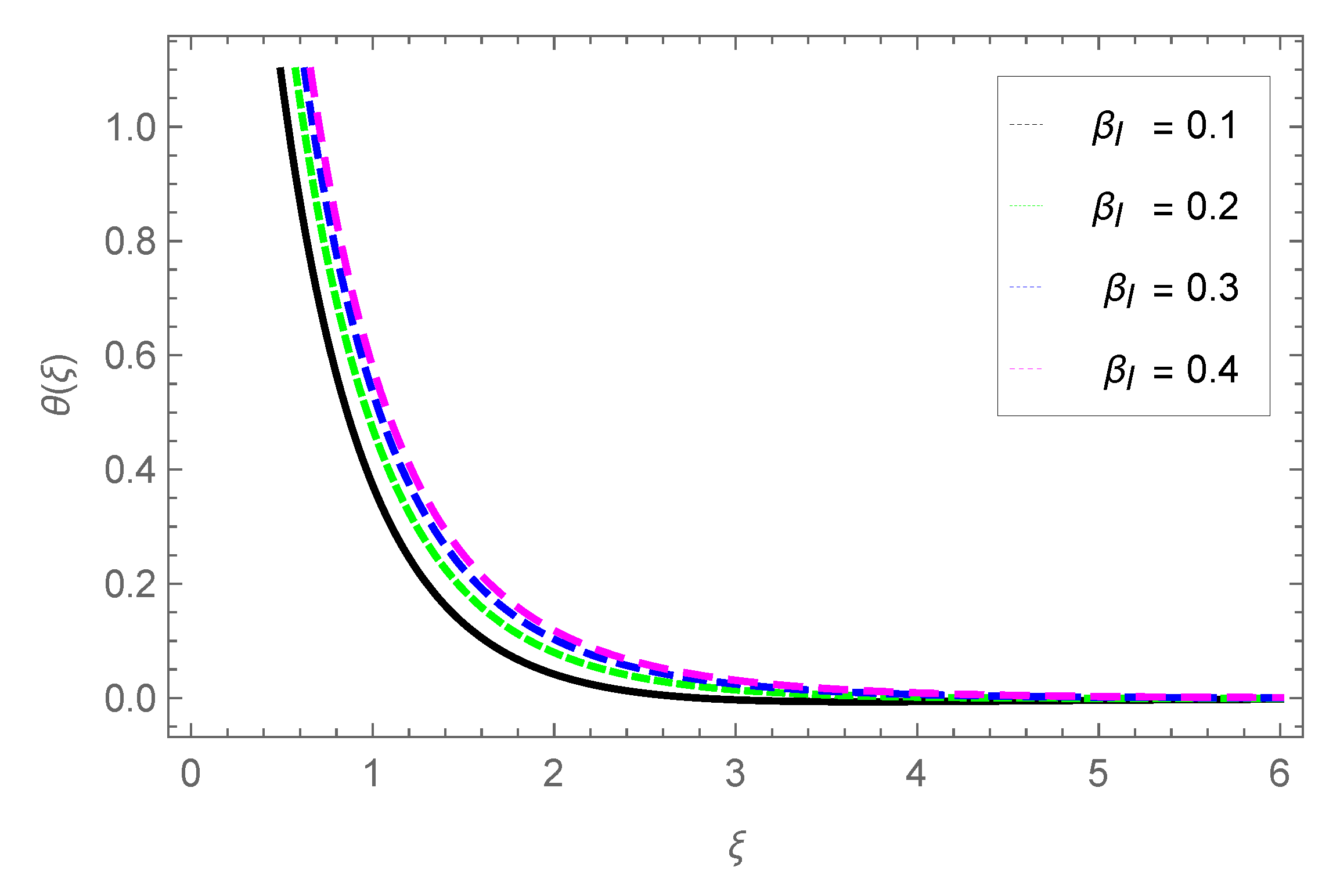

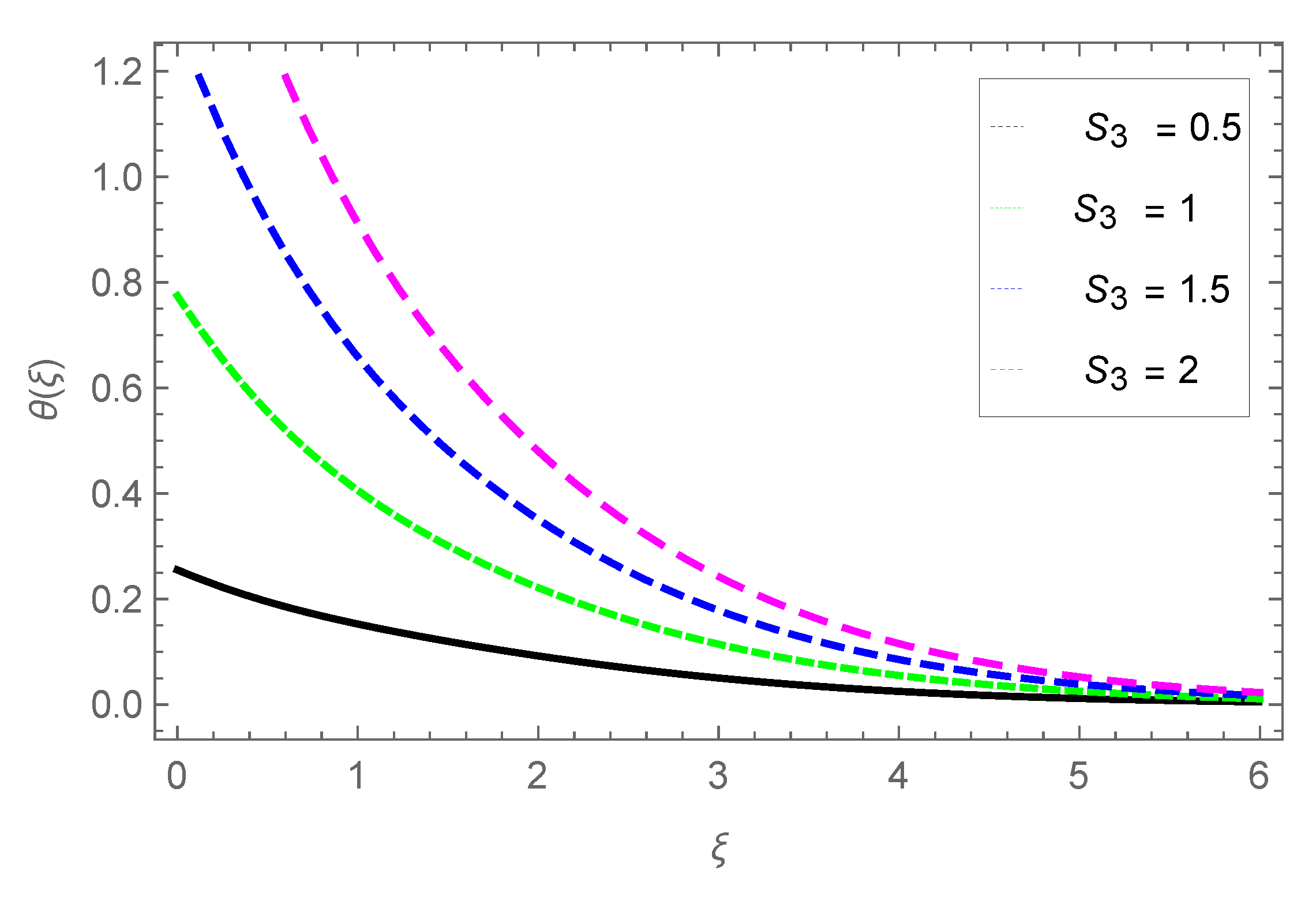

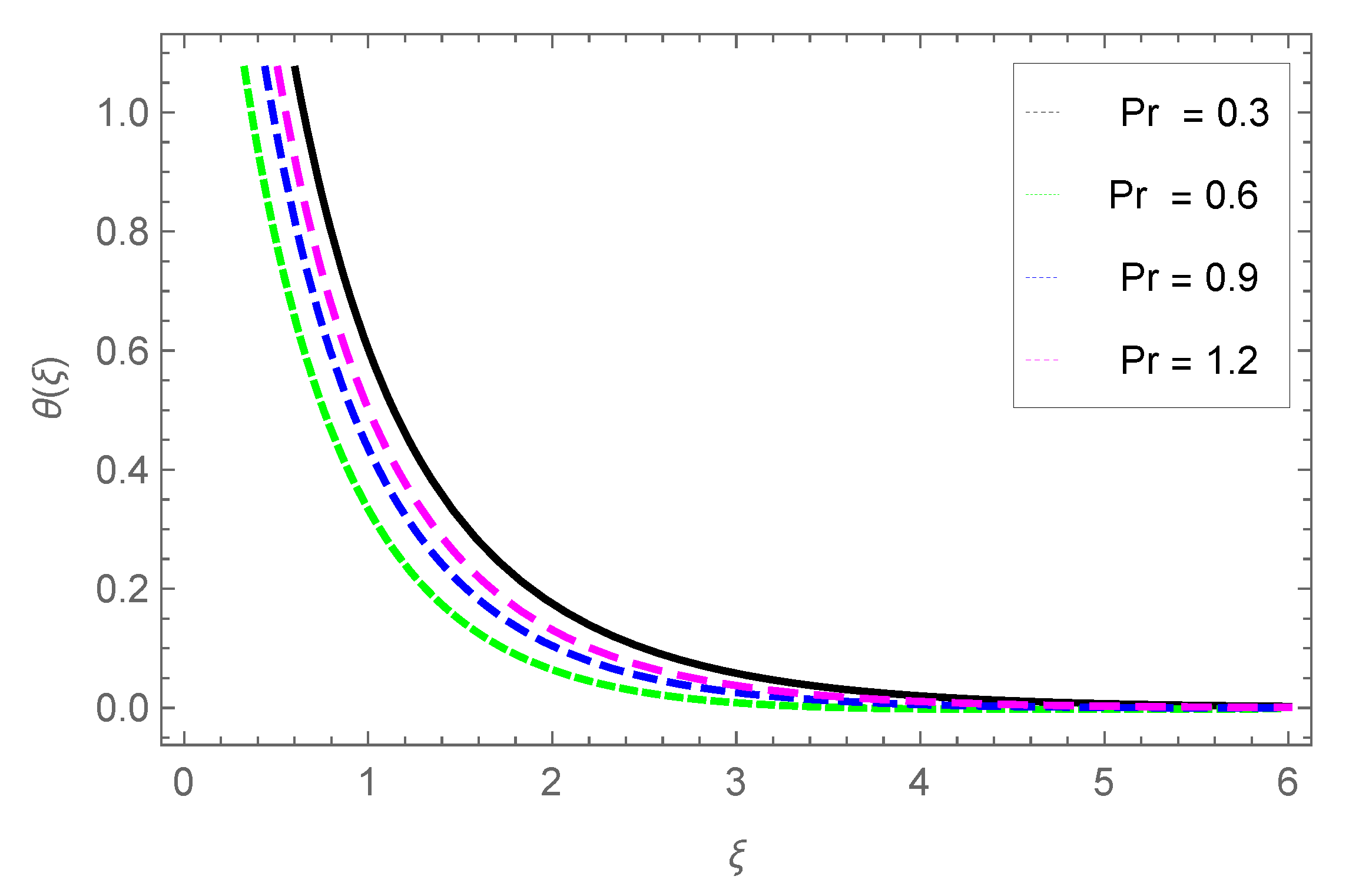

3.3. Temperature Profile

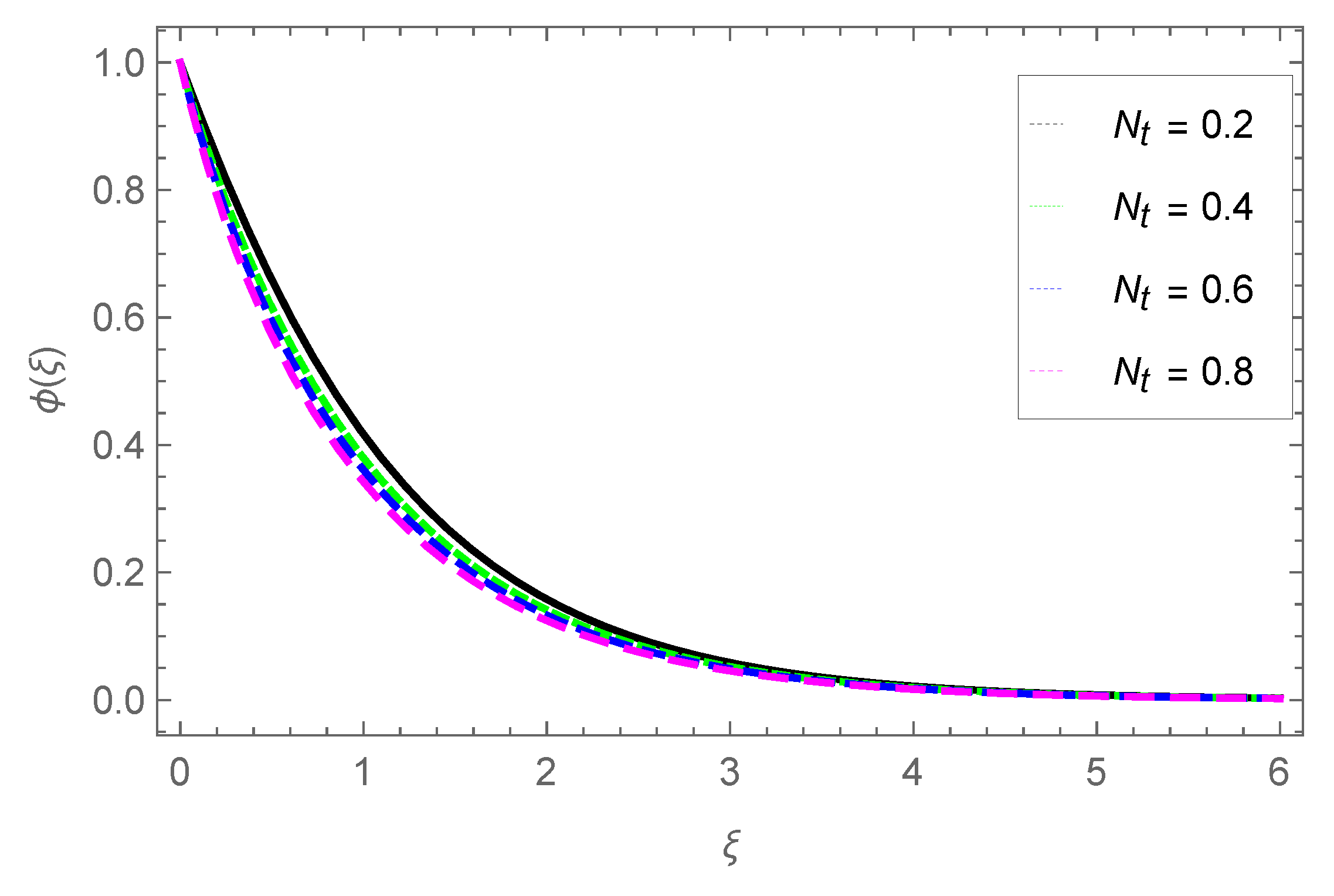

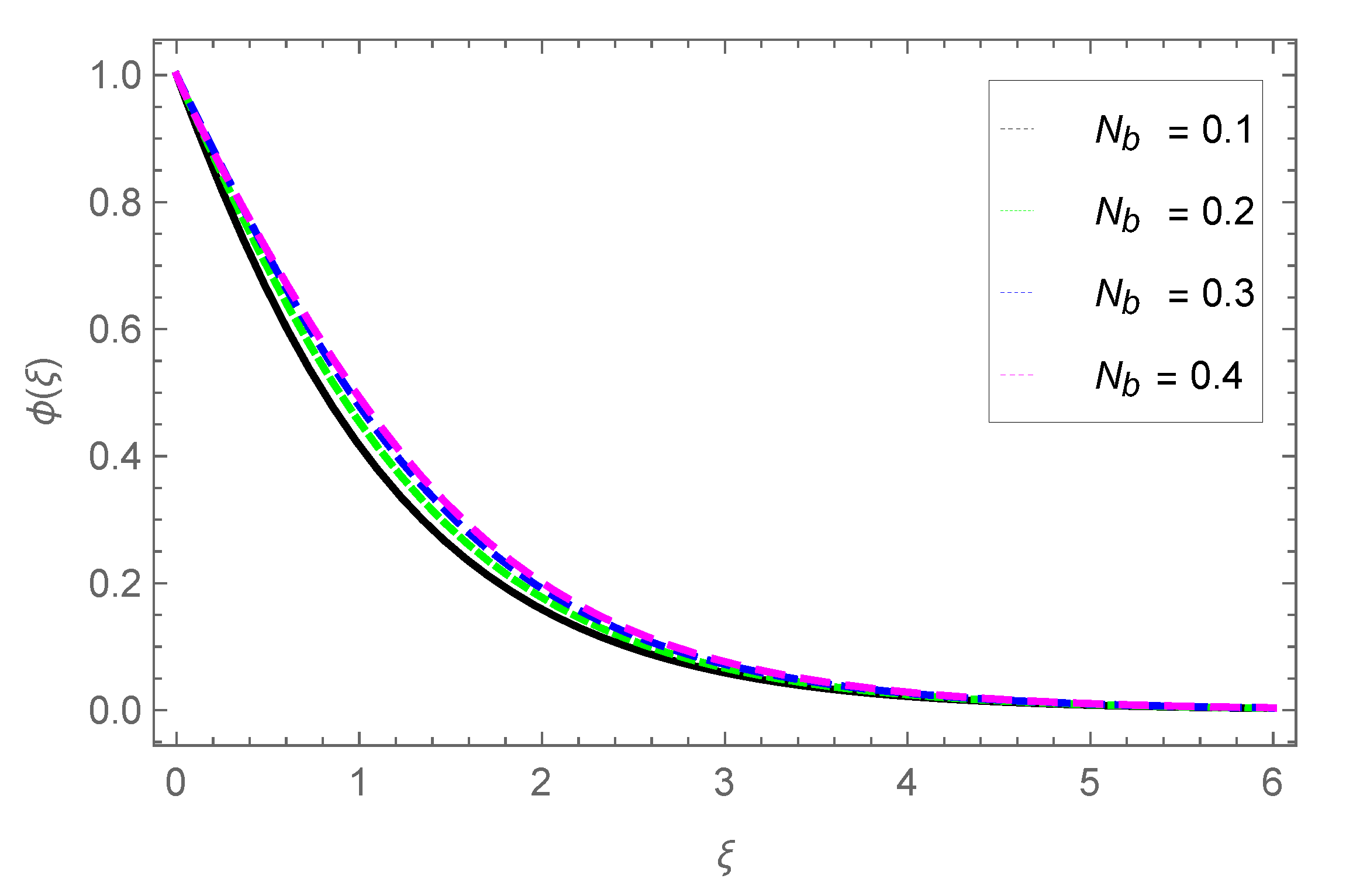

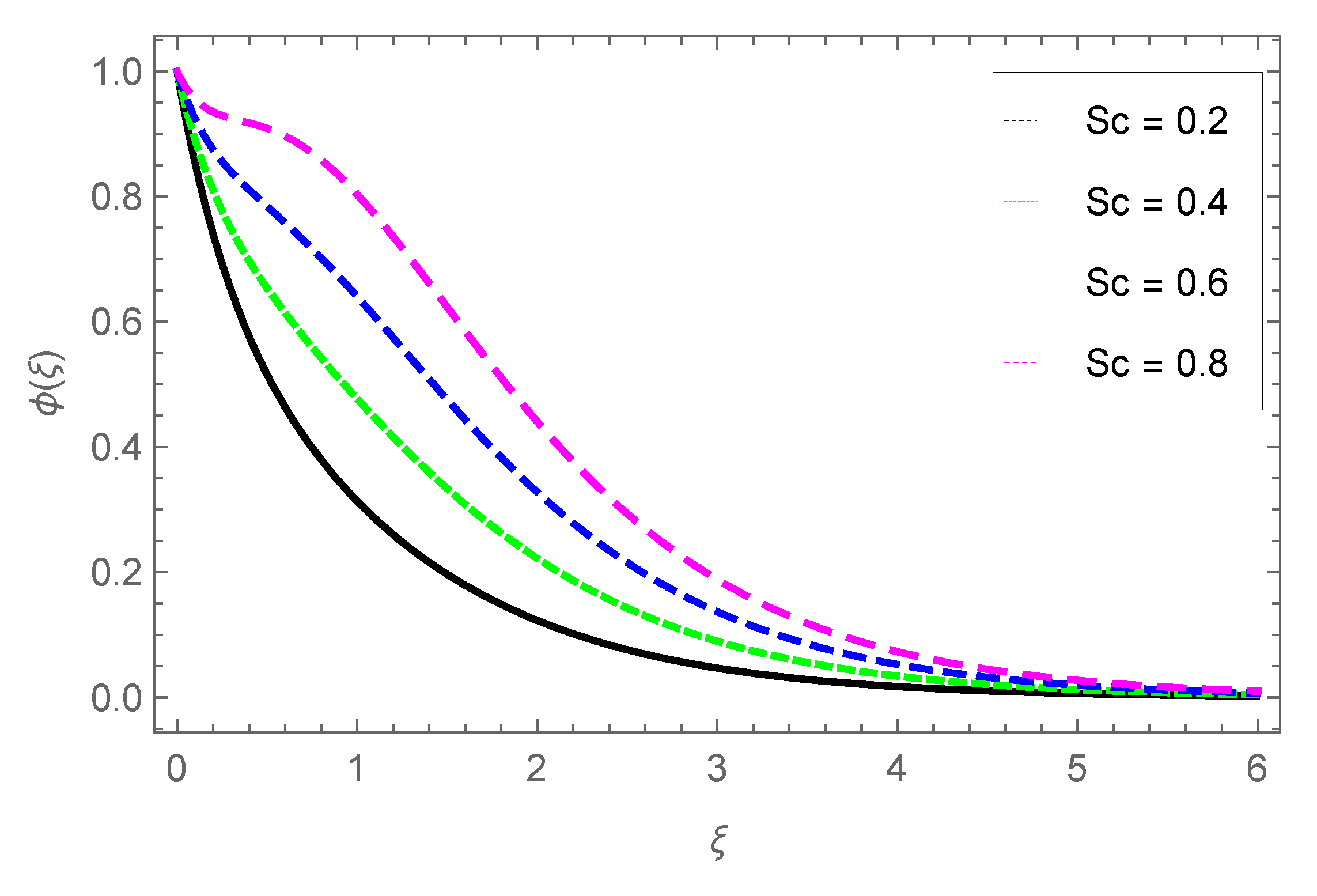

3.4. Nanoparticle Concentration Profile

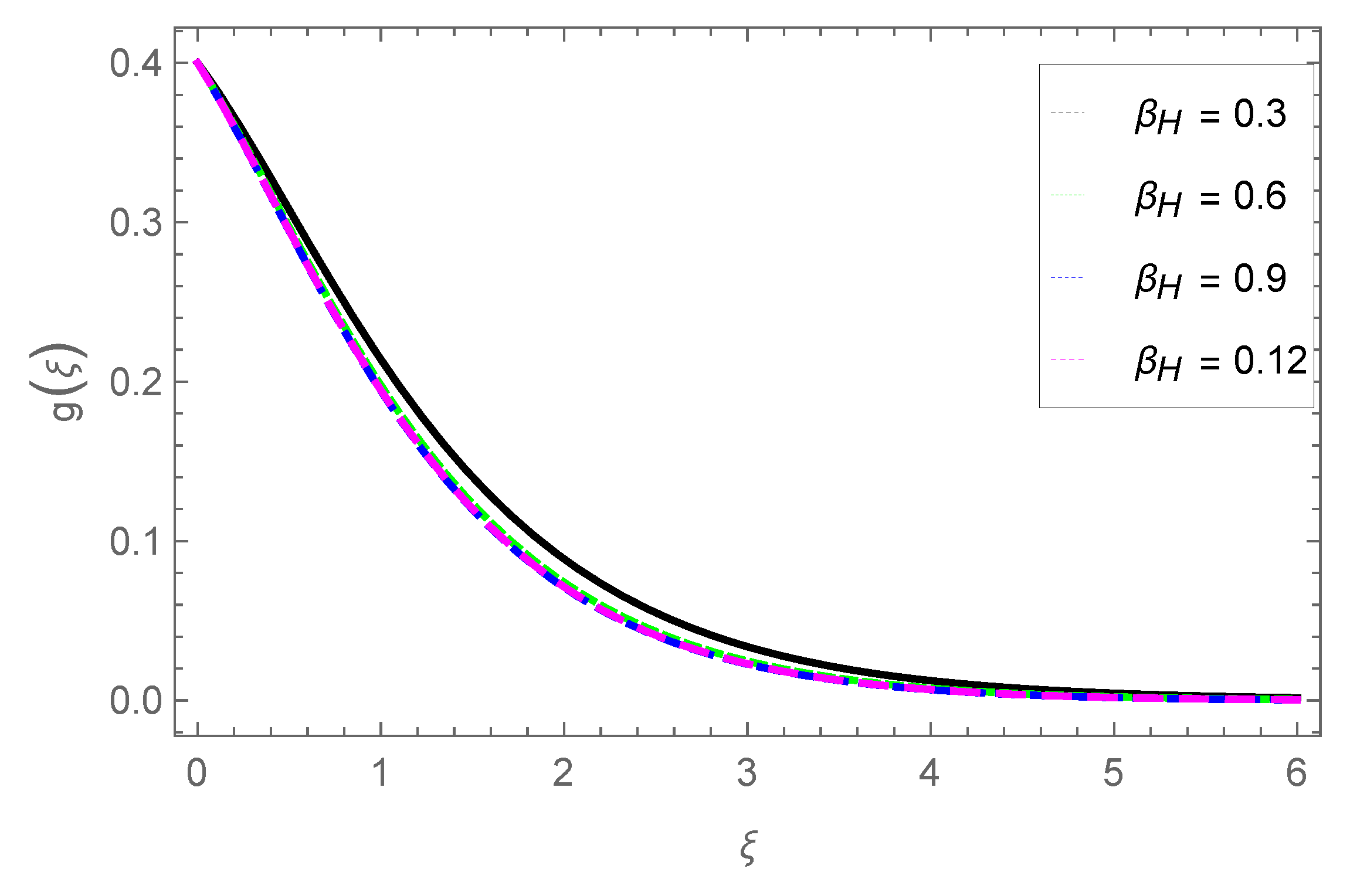

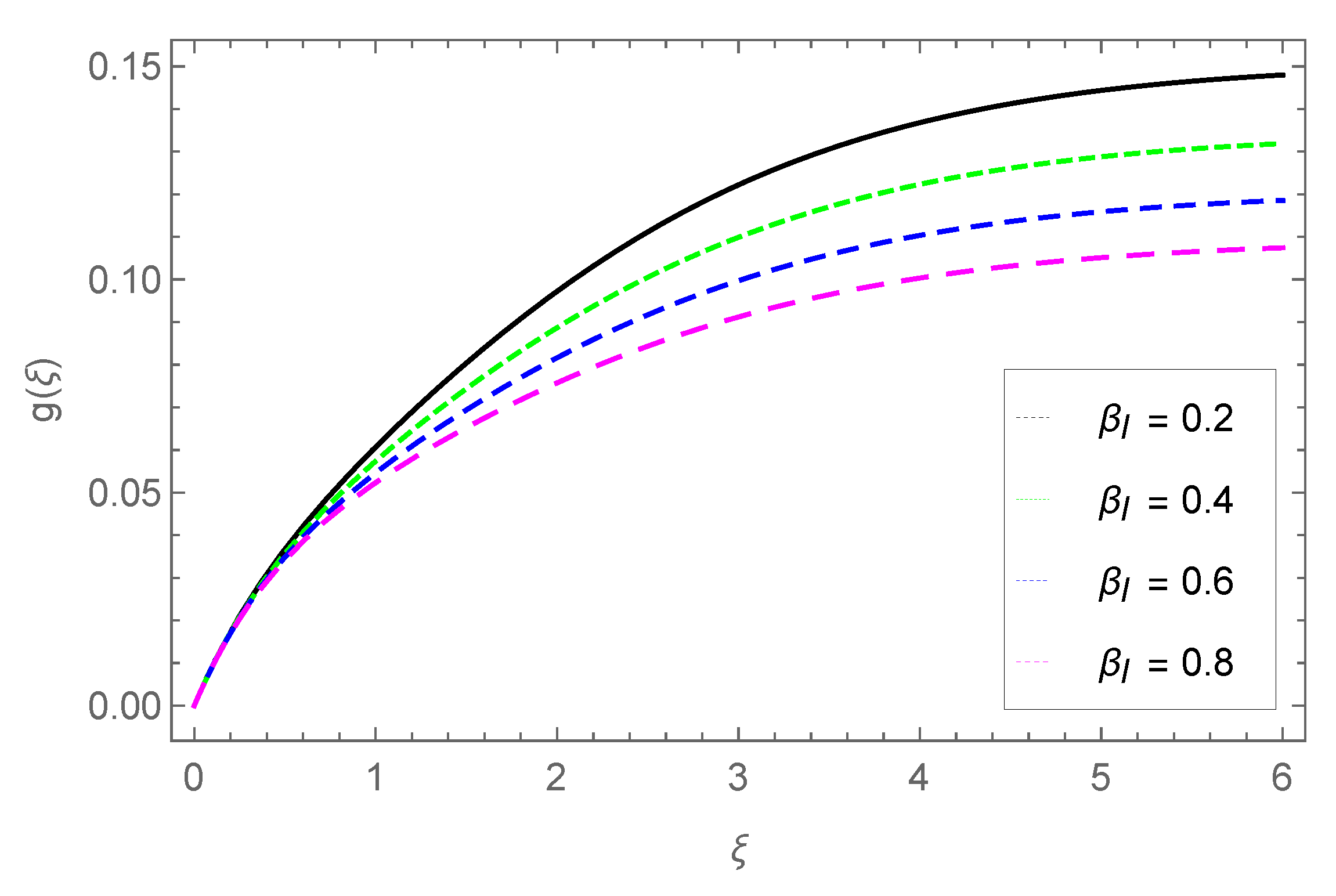

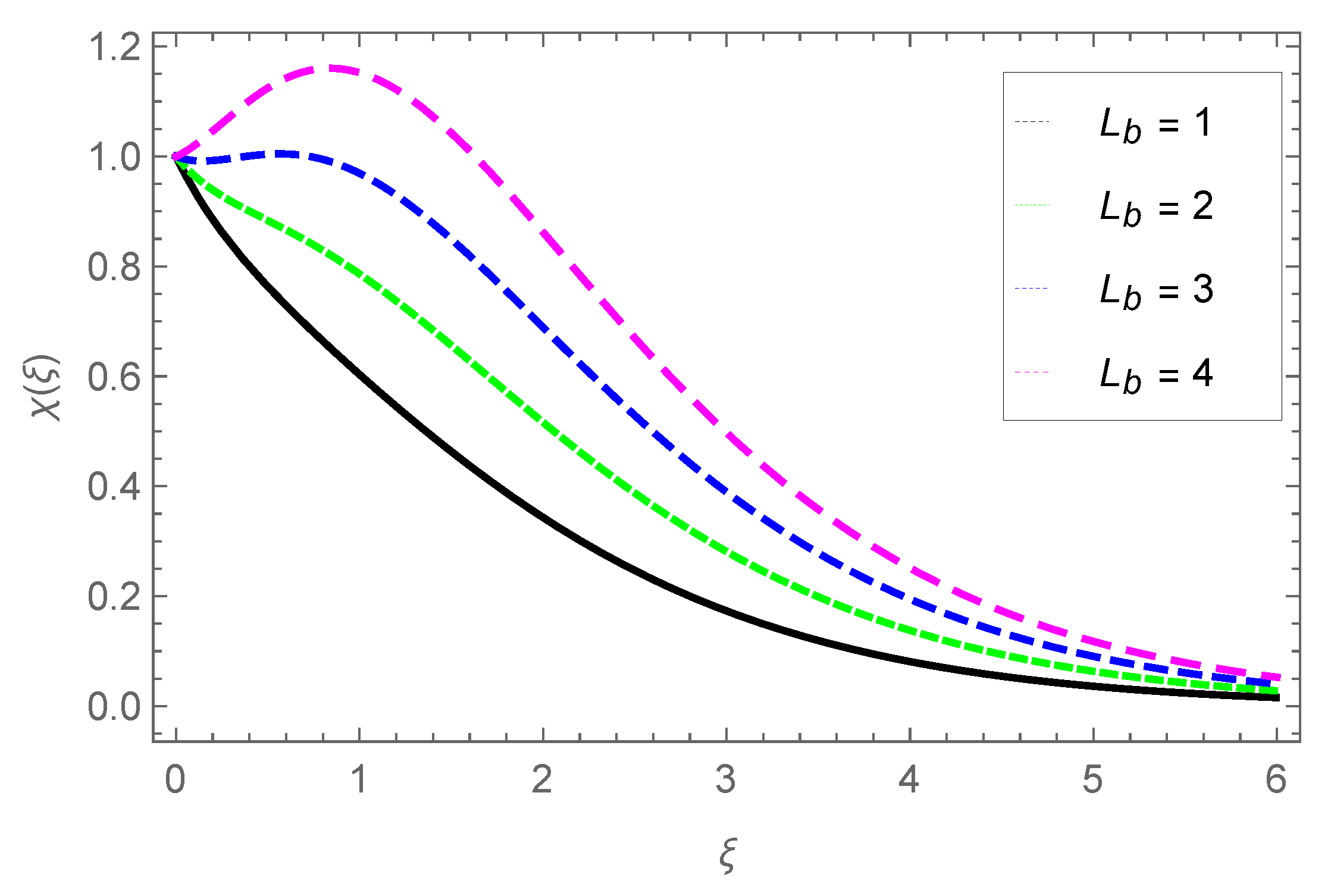

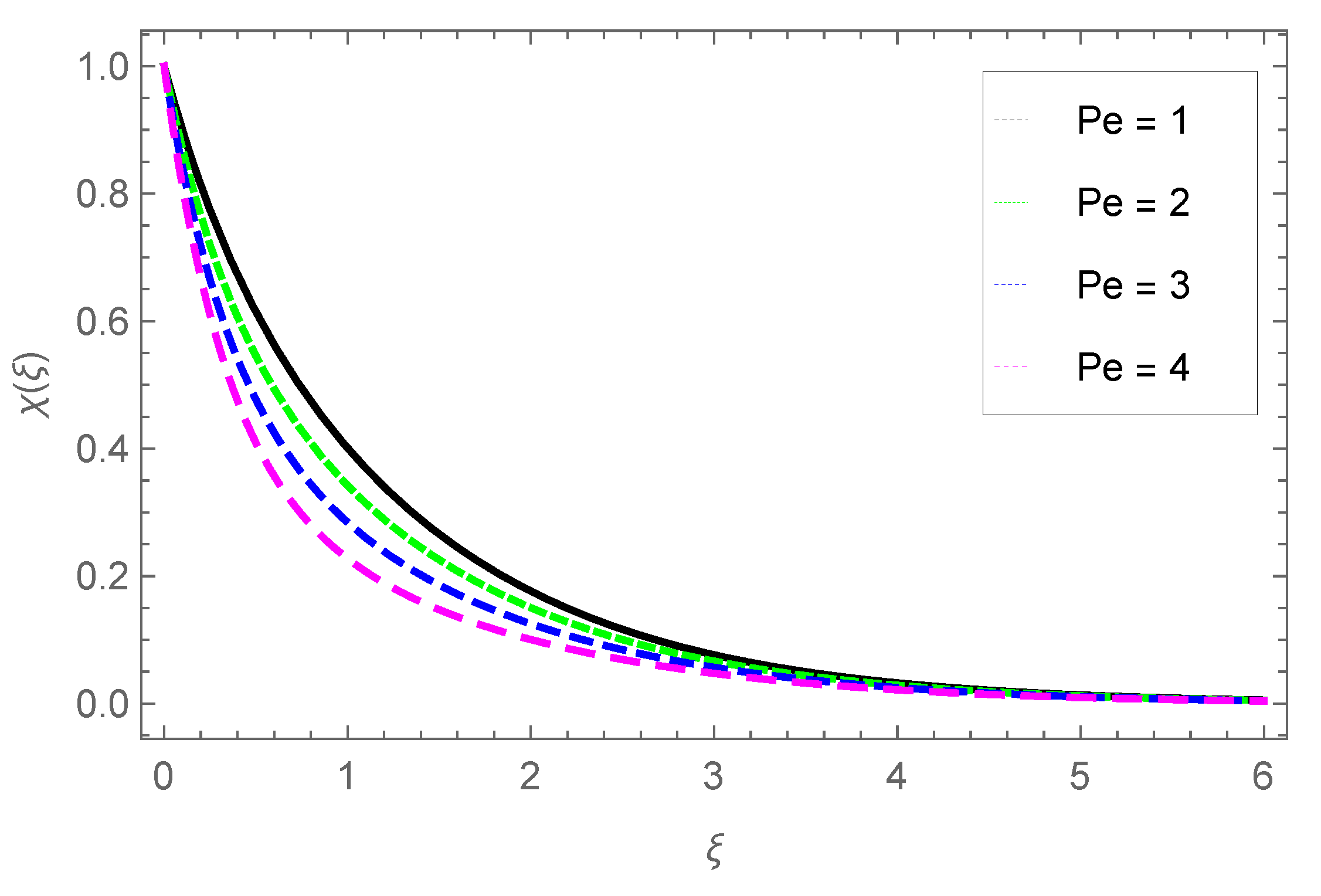

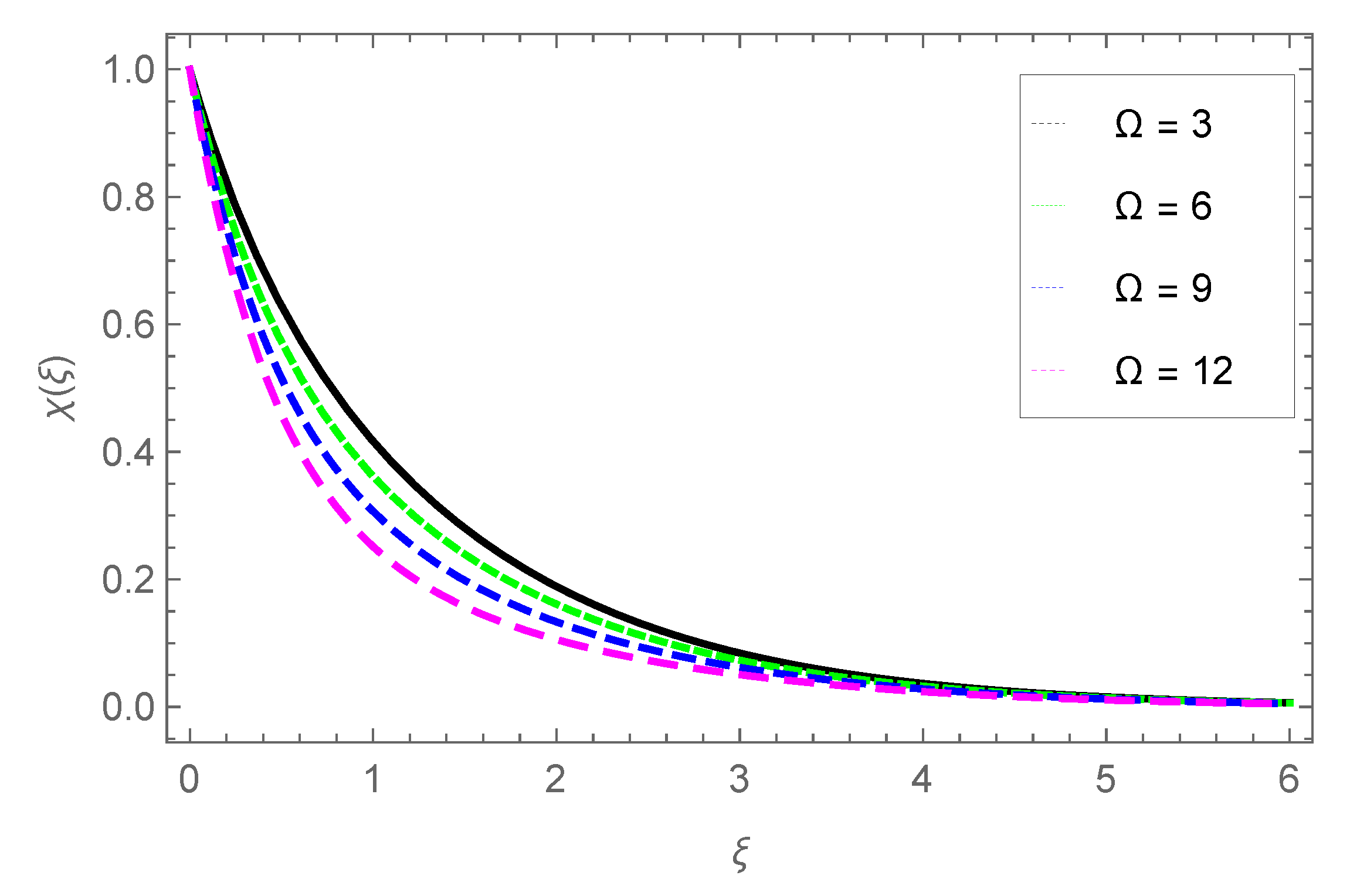

3.5. Gyrotactic Microorganisms Profile

3.6. Tubular Description

3.7. Final Remarks

- The radial velocity profile is enhanced with parameters M and , but velocity is reduced with parameters d2 and .

- The fluid velocity slows down in the transverse direction with parameters M, , and .

- The temperature profile is raised with parameters , , S3, and Pr.

- The concentration of the nanoparticle grows with parameters and Sc, while it is reduced with parameter .

- The concentration of the gyrotactic microbe profile grows with parameter Lb, while it is reduced with parameters Pe and .

Nomenclature

| M | Magnetic field parameter | Concentration difference parameter | |

| Nt | Thermophoresis parameter | Nb | Brownian motion parameter |

| Wce | Maximum cell swimming speed | Lb | Bioconvection Lewis number |

| Prandtl number | Heat transfer coefficient | ||

| B0 | Strong magnetic field | T∞ | Ambient temperature (k) |

| N | Concentration of microorganisms | (u,v,w) | Components of velocity () |

| DT | Thermophoretic diffusion coefficient | C∞ | Ambient concentration |

| b0 | Chemotaxis constant | Cw | Surface concentration |

| T | Fluid temperature (k) | C | Concentration |

| DB | Brownian diffusion coefficient | Tw | Temperature on wall (k) |

| Dn | Diffusivity of microbes | f | Axial velocity profile |

| g | Transverse velocity profile | N∞ | Ambient concentration of microbes |

| cp | Specific heat at constant pressure | Axis coordinates (m) | |

| k | Thermal conductivity | Nw | Reference concentration of microbes |

| (a, b) | Dimensional constants | Pe | Bioconvection Peclet number |

| , | Drag force | Sc | Schmidt number |

| Greek Letters | |||

| Dynamic viscosity | Kinematic viscosity of nanopartcles | ||

| Density of nanoparticle() | Stefan-Boltzmann constant | ||

| Similarity variable | Hall parameter | ||

| Concentration profile | Temperature profile | ||

| Ion slip parameter | Gyrotactic microorganisms profile | ||

| Surface shear stress | d2 | Thermal relaxation time |

References

- R. E. Powell., H. Eyring, Mechanism for relaxation theory of viscosity, Nature. 154(55): 427–428 (1944).

- M. Hassan., M. Ahsan., Usman., M. Alghamdi., T. Muhammad. Entropy generation and flow characteristics of Powell Eyring fluid under effects of time sale and viscosities parameters. natureportfolio. 8376 (2023).

- R. Sajjad., M. Mushtaq., S. Farid., K. Jabeen., R. M. A. Muntazir. Numerical Simulations of Magnetic Dipole over a Nonlinear Radiative Eyring–Powell Nanofluid considering Viscous and Ohmic Dissipation Effects. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 16 (2021).

- O. A. Abo-zaid1., R. A. Mohamed1., F. M. Hady., A. Mahdy1., MHD Powell–Eyring dusty nanofluid flow due to stretching surface with heat flux boundary condition. Journal of the Egyptian Mathematical Society. 29: 14 (2021).

- N.S. Akbar, Application of Eyring-Powell fluid model in peristalsis with nanoparticles, J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 12(1): 94–100 (2015).

- M.Y. Malik., S. Bilal., M. Bibi., U. Ali., Logarithmic and parabolic curve fittinganalysis of dual stratified stagnation point MHD mixed convection flow of Eyring- Powell fluid induced by an inclined cylindrical stretching surface, Results Phys. 7: 544–552 (2017).

- M. Ramzan., H. Gul., S. Kadry., Y. Chu. Role of bioconvection in a three-dimensional tangent hyperbolic partially ionized magnetised nanofluid flow with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux and activation energy. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer. 120: 104994 (2021).

- I. H. Qureshi., M. Nawaz., A. Shahzad. Numerical study of dispersion of nanoparticles in magnetohydrodynamic liquid with Hall and ion slip currents. AIP Adv. 9: 025219 (2019).

- T. Hayat., H. Zahir., A. Alsaedi., B. Ahmad. Hall current and Joule heating effects on peristaltic flow of viscous fluid in a rotating channel with convected boundary conditions. Results Phys. 7: 2831–2836 (2017).

- N. S. Khan., T. Gul., S. Islam., A. Khan., Z. Shah. Brownian motion and thermophoresis effects on MHD mixed convective thin film second-grade nanofluid flow with Hall effect and heat transfer past a stretching sheet J. Nanofluids. 6: 812–29 (2017).

- T. Hayat., M. Awais., H. Zahir., A. Saedi., B. Ahmad. Hall current and joule heating effects on the mixed convection peristaltic flow of viscous fluid in a rotating channel with convective boundary conditions, Results Phys. 7: 2831–2836 (2017).

- M. Nawaz., S. Rana., I. H. Qureshi., T. Hayat. Three-dimensional heat transfer in the mixture of nanoparticles and micropolar MHD plasma with Hall and ion effects, Results Phys. 8: 1063–1073 (2018).

- E. F. Elshehawey., N. T. Eldabe., E. M. E. Elbarbary., N. Z. Elgazery., Chebyshev finite-difference method for the effects of hall and ion-slip currents on magnetohydrodynamic flow with variable thermal conductivity, Can. J. Phys. 82: 701–715 (2004).

- Y. Dadhich., R. Jain., K. Loganathan. M. Abbas., K. S. Prabu., M. S. Alqahtani. Sisko nanofluid flow through exponential stretching sheet with swimming of motile gyrotactic microorganisms: An application to nanoengineering. Open Physics. 21: 20230132 (2023).

- D. R. Mostapha., N. T. M. El-dabe. Peristaltic transfer of nanofluid with motile gyrotactic microorganisms with nonlinear thermic radiation. natureportfolio. 13: 7054 (2023).

- M. Iqbal., N. S. Khan., W, Khan., S. B. H. Hassine., S. A. Alhabeeb., H. A. E. Khalifa.Partially ionized bioconvection Eyring–Powell nanofluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms in thermal system. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress. 47: 102283 (2024).

- M. Khan., M. Irfan., W. A. Khan. Impact of nonlinear thermal radiation and gyrotactic microorganisms on the Magneto-Burgers nanofluid. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences. 130: 375-382 (2017).

- M. M. Bhatti., M. Marin., A. A. Zeeshan., R. Ellahi., S. I. Abdelsalam. Swimming of motile gyrotactic microorganisms and nanoparticles in blood flow through anisotropically tapered arteries. Front. Phys. 8: 95 00095 (2020).

- M. I. Khan., F. Alzahrani., A. Hobiny. Heat transport and nonlinear mixed convective nanomaterial slip flow of Walter-B fluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms. Alex. Eng. J. 59(3): 1761–1769 (2020).

- N. I. Nima. Melting effect on non-Newtonian fluid flow in gyrotactic microorganism saturated non-darcy porous media with variable fluid properties. Appl. Nanosci. 10(10): 3911–3924 (2020).

- S. Naz., M. M. Gulzar., M. Waqas., T. Hayat., A. Alsaedi. Numerical modeling and analysis of non-Newtonian nanofluid featuring activation energy. Appl. Nanosci. 10(8): 3183–3192 (2020).

- N.S. Khan, Q. Shah, A. Bhaumik, P. Kumam, P. Thounthong, I. Amiri, Entropy generation in bioconvection nanofluid flow between two stretchable rotating disks, Sci. Rep. 10 (2020) 4448.

- N.S. Khan, Mixed convection in mhd second grade nanofluid flow through a porous medium containing nanoparticles and gyrotactic microorganisms with chemical reactions, Filomat. 33 (14): 4627–4653 (2019).

- S. Zuhra., N.S. Khan., M. Alam., S. Islam., A. Khan. Buoyancy effects on nanoliquids film flow through a porous medium with gyrotactic microorganisms and cubic auto catalysis chemical reaction, Adv. Mech. Eng. 12 (1): 1–17 (2019).

- S. U. S. Choi., J. Eastman., Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. ASME. 231: 718–720 (2001).

- J. Buongiorno. Convective transport in nanofluids. J. Heat Transf. 128: 240–250 (2006).

- M. Waqas., S. Jabeen., T. Hayat., S. A. Shehzad., A. Alsaedi. Numerical simulation for nonlinear radiated Eyring-Powell nanofluid considering the magnetic dipole and activation energy. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 112: 104401 (2020).

- O. A. Akbari., D. Toghraie., A. Karimipour., A. Marzban., G. R. Ahmadi. The effect of velocity and dimension of solid nanoparticles on heat transfer in non-Newtonian nanofluid. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 86: 68–75 (2017).

- R. Ellahi., A. Zeeshan., A. Waheed., N. Shehzad.S. M. Sait. Natural convection nanofluid flow with heat transfer analysis of carbon nanotubes–water nanofuid inside a vertical truncated wavy cone. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 1–19 (2021).

- M. Turkyilmazoglu. On the transparent effects of Buongiorno nanofluid model on heat and mass transfer. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 136(4): 1–15 (2021).

- T. Nazar., M. M. Bhatti., E. E. Michaelides. Hybrid (Au-TiO2) nanofluid flow over a thin needle with magnetic field and thermal radiation: Dual solutions and stability analysis. Microfluid Nanofluidics. 26(2): 12 (2022).

- M. Bilal., M. Ramzan., Y. Mehmood., T. Sajid., S. Shah. M. Y. A. Malik. Novel approach for EMHD Williamson nanofluid over nonlinear sheet with double stratification and Ohmic dissipation. J. Process Mech. Eng. 0(0): 1–16 (2021).

- J. R. Platt., “Bioconvection patterns in cultures of free-swimming microorganisms,”.Science. 133: 1766–1767 (1963).

- F. Mabood., W. A. Khan., A. Izani., M. Ismail. Analytical modeling of free convection of non-Newtonian nanofluids flow in porous media with gyrotactic microorganisms using OHAM. In AIP Conference Proceedings ICOQSIA Langkawi, Malaysia.(2014).

- A. M. Rashad., A. J. Chamkhab., B. Mallikarjunac., M. M. M. Abdoua. “Mixed bioconvection flow of a nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms past a vertical slender cylinder,” Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer (FHMT). 10(21): (2018).

- S. Shaw. P. Sibanda. A. Sutradhar. P. V. S. N. Murthy. Magnetohydrodynamics and soret effects on bioconvection in a porous medium saturated with a nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms. ASME J Heat Transfer. 136: 052601 (2014).

- Mekheimer K.S., Ramadan S.F. New insight into gyrotactic microorganisms for bio-thermal convection of Prandtl nanofluid over a stretching/shrinking permeable sheet. SN Appl. Sci. 450: 1–11 (2020).

- , Anwar M.J., Khan W.A. Bioconvective non-Newtonian nanofluid transport in porous media containing micro-organisms in a moving free stream. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 15 (2015).

- M. Nawaz., H.Q. Imran., A. Shahzad. Thermal performance of partially ionized Eyring–Powell liquid: A theoretical approach, Phys. Scripta. 94: 10 (2019).

- M. Ramzan., H. Gul., S. Kadry., Y. M. Chu. Role of bioconvection in a three dimensional tangent hyperbolic partially ionized magnetized nanofluid flow with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux and activation energy, Int. Commun. Heat Mass Trans. 120: 104994 (2021).

- M. Iqbal., N. S. Khan., W. Khan., S. B. H. Hassine., S. A. Alhabeeb., H. A. E. Khalifa. Partially ionized bioconvection Eyring–Powell nanofluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms in thermal system. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress. 47: 102283 (2024).

- Liao S 2012 Homotopy analysis method in non-linear differential equations Higher Education Press Beijing and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Liao S 2004 On the homotopy analysis method for non-linear problems Appl. Maths. Computat. 147 (Elsevier) 499–513.

- Liao S 1998 Homotopy analysis method: a new analytic method for non-linear problems Appl. Maths. Mech. (English edn, vol. 19, No. [CrossRef]

- M. Iqbal., N. S. Khan., W. Khan., S. B. H. Hassine., S. A. Alhabeeb., H. A. E. Khalifa. Partially ionized bioconvection Eyring–Powell nanofluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms in thermal system. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress. 47: 102283 (2024).

- M. Ramzan., H. Gul., S. Kadry., Y. M. Chu. Role of bioconvection in a three dimensional tangent hyperbolic partially ionized magnetized nanofluid flow with Cattaneo-Christov heat flux and activation energy. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Trans. 120 104994 (2021).

| M | [37] | Present results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.852219 | 0.852218 |

| 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.870754 | 0.870752 |

| 0.1 | 2 | 0.4 | 0.884226 | 0.884224 |

| 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 0.890434 | 0.890432 |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.889218 | 0.889219 |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.902486 | 0.902485 |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.904523 | 0.904520 |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.906588 | 0.906586 |

| 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.964238 | 0.964235 |

| 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.010009 | 1.010006 |

| 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.115522 | 1.115520 |

| 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.221035 | 1.221033 |

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.72467 | 0.72464 |

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.878117 | 0.878116 |

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.891306 | 0.891307 |

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.904496 | 0.904494 |

| [37] | [36] | Present results | [37] | [36] | Present results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.719070243 | 0.719070241 | 0.719070240 | 0.111575838 | 0.111575831 | 0.111575830 |

| 0.757387985 | 0.757387982 | 0.757387980 | 0.281564212 | 0.281564212 | 0.281564211 |

| 0.797424135 | 0.797424132 | 0.797424131 | 0.394505727 | 0.394505723 | 0.394505722 |

| 0.823405641 | 0.823405643 | 0.823405642 | 0.451557772 | 0.451557774 | 0.451557772 |

| 0.887549495 | 0.887549494 | 0.887549492 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039883 |

| 0.887549495 | 0.887549496 | 0.887549495 | 0.55719186 | 0.55719181 | 0.55719182 |

| 0.887549495 | 0.887549497 | 0.887549496 | 0.55719186 | 0.55719182 | 0.55719181 |

| 0.887549595 | 0.887549598 | 0.887549597 | 0.55719186 | 0.55719183 | 0.55719182 |

| 0.887549495 | 0.887549491 | 0.887549490 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039882 |

| 0.887044175 | 0.887044172 | 0.887044171 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039885 | 0.564039883 |

| 0.887044175 | 0.887044173 | 0.887044172 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039886 | 0.564039885 |

| 0.887044175 | 0.887044174 | 0.887044174 | 0.564039884 | 0.564039887 | 0.564039884 |

| 0.887044175 | 0.887044175 | 0.887044174 | 0.234080623 | 0.234080628 | 0.234080627 |

| 0.745831925 | 0.745831925 | 0.745831923 | 0.226862343 | 0.226862341 | 0.226862340 |

| 0.741235004 | 0.741235004 | 0.741235002 | 0.224322014 | 0.224322012 | 0.224322011 |

| 0.736437806 | 0.736437806 | 0.736437804 | 0.222927008 | 0.222927005 | 0.222927004 |

| 0.731437806 | 0.731437806 | 0.731437805 | 0.221986349 | 0.221986346 | 0.221986345 |

| 0.726117576 | 0.726117576 | 0.726117575 | 0.664419328 | 0.664419327 | 0.664419326 |

| 0.80225148 | 0.80225148 | 0.80225147 | 0.671397457 | 0.671397456 | 0.671397455 |

| 0.981391226 | 0.981391226 | 0.981391225 | 0.765839488 | 0.765839488 | 0.765839487 |

| 1.158190169 | 1.158190169 | 1.158190168 | 0.947744044 | 0.947744044 | 0.947744043 |

| 1.476161533 | 1.476161533 | 1.476161531 | 1.153120999 | 1.153120999 | 1.153120998 |

| 1.839517997 | 1.839517997 | 1.839517996 | 0.679775184 | 0.679775184 | 0.679775183 |

| 0.993626652 | 0.993626652 | 0.993626651 | 0.655608013 | 0.655608013 | 0.655608012 |

| 0.884899639 | 0.884899639 | 0.884899638 | 0.612787646 | 0.612787646 | 0.612787645 |

| 0.802264361 | 0.802264361 | 0.802264360 | 0.563176151 | 0.563176151 | 0.563176150 |

| 0.748580802 | 0.748580802 | 0.748580800 | 0.513618696 | 0.513618696 | 0.513618695 |

| 0.716979363 | 0.716979363 | 0.716979362 | 0.656965055 | 0.656965055 | 0.656965054 |

| 0.661008802 | 0.661008802 | 0.661008801 | 0.555527812 | 0.555527812 | 0.555527811 |

| 0.74256172 | 0.74256172 | 0.74256170 | 0.455495507 | 0.455495507 | 0.455495506 |

| 0.77837091 | 0.77837091 | 0.77837090 | 0.386043017 | 0.386043017 | 0.386043016 |

| 0.785950317 | 0.785950317 | 0.785950316 | 0.337580336 | 0.337580336 | 0.337580335 |

| 0.784265665 | 0.784265665 | 0.784265664 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669163 |

| 0.856524973 | 0.856524973 | 0.856524972 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669164 |

| 0.856524973 | 0.856524973 | 0.856524972 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669162 |

| 0.856524973 | 0.856524973 | 0.856524971 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669163 |

| 0.856524973 | 0.856524973 | 0.856524972 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669163 |

| 0.856524973 | 0.856524973 | 0.856524972 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669164 |

| 0.856524973 | 0.856524973 | 0.856524971 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669165 | 0.556669164 |

| [37] | [36] | Present results |

|---|---|---|

| 1.5990239 | 1.5990231 | 1.5990231 |

| 1.4202682 | 1.4202682 | 1.4202682 |

| 1.1564338 | 1.1564333 | 1.1564333 |

| 0.9287895 | 0.9287894 | 0.9287894 |

| 0.5494868 | 0.5494865 | 0.5494865 |

| 0.8096016 | 0.8096016 | 0.8096016 |

| 1.0905005 | 1.0905007 | 1.0905007 |

| 1.3286006 | 1.3286008 | 1.3286008 |

| 0.5491808 | 0.5491809 | 0.5491809 |

| 0.9287895 | 0.9287895 | 0.9287895 |

| 1.2669854 | 1.2669854 | 1.2669854 |

| 1.3689696 | 1.3689696 | 1.3689696 |

| 1.4844171 | 1.4844171 | 1.4844171 |

| 1.4833107 | 1.4833107 | 1.4833107 |

| 1.4821196 | 1.4821196 | 1.4821196 |

| 1.4808276 | 1.4808276 | 1.4808276 |

| 1.4794173 | 1.4794173 | 1.4794173 |

| 0.9433476 | 0.9433476 | 0.9433476 |

| 0.910217 | 0.910217 | 0.910217 |

| 0.8077522 | 0.8077522 | 0.8077522 |

| 0.7457675 | 0.7457675 | 0.7457675 |

| 0.1187274 | 0.1187274 | 0.1187274 |

| 0.4541371 | 0.4541371 | 0.4541371 |

| 0.8618128 | 0.8618128 | 0.8618128 |

| 1.1292928 | 1.1292928 | 1.1292928 |

| 1.2931189 | 1.2931189 | 1.2931189 |

| 0.9552824 | 0.9552824 | 0.9552824 |

| 1.159594 | 1.159594 | 1.159594 |

| 1.3236266 | 1.3236266 | 1.3236266 |

| 1.4156669 | 1.4156669 | 1.4156669 |

| 1.4692599 | 1.4692599 | 1.4692599 |

| 0.66944612 | 0.66944612 | 0.66944612 |

| 0.8129271 | 0.8129271 | 0.8129271 |

| 0.8957033 | 0.8957033 | 0.8957033 |

| 0.9287895 | 0.9287895 | 0.9287895 |

| 0.94665 | 0.94665 | 0.94665 |

| 0.946555 | 0.946555 | 0.946555 |

| 0.8129271 | 0.8129271 | 0.8129271 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).