Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

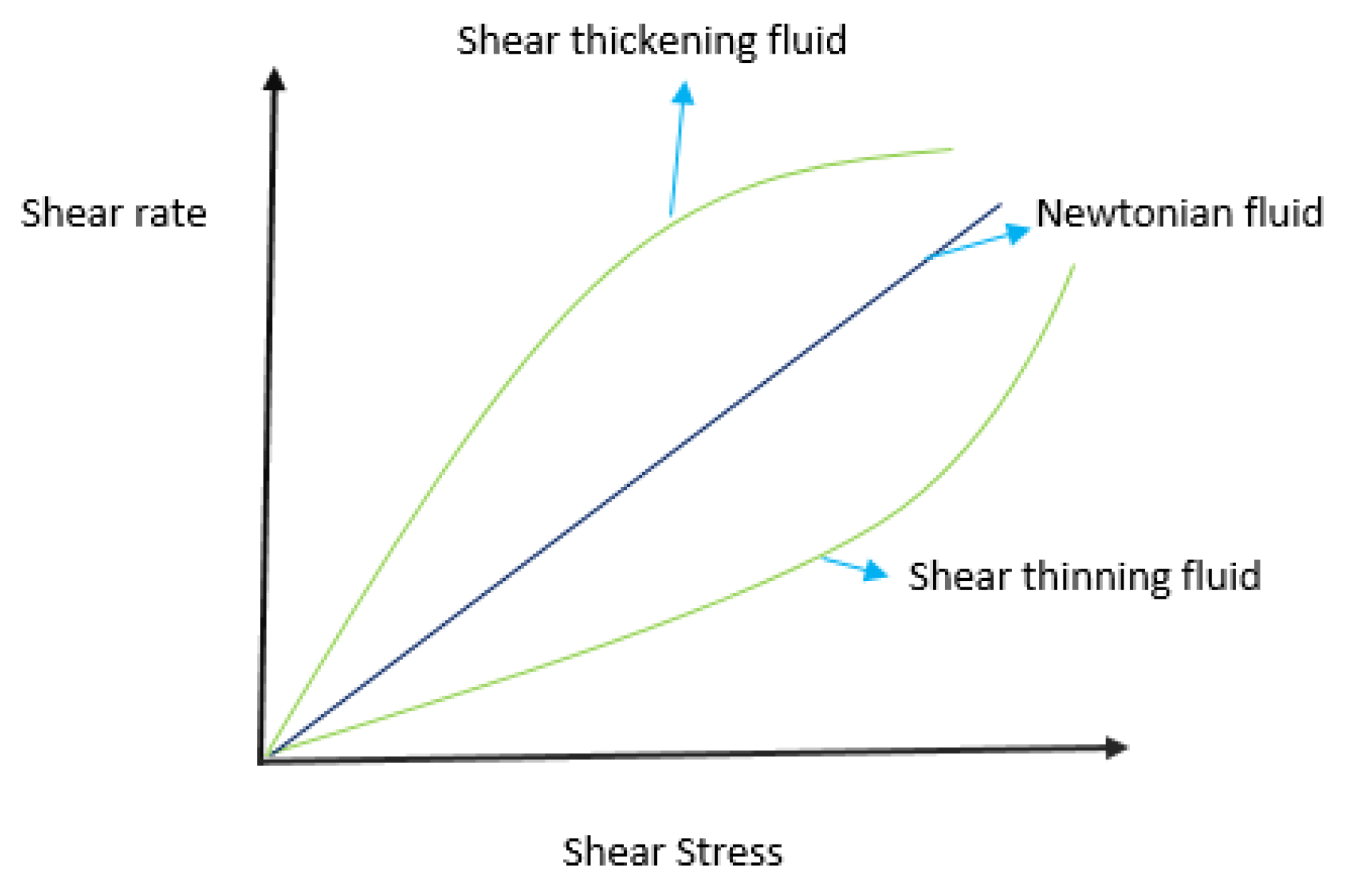

1. Introduction

Novelty

- What is the influence of the magnetic field in bicoconvection Casson fluid?

- What is the consequence of Brownian movement, heat transfer, Darcy number and Fourchemmir principal on bioconvection in Casson liquid?

- How does the Casson fluid react in the presence of chemical reactions over the stretching sheet?

2. Mathematical Formulation

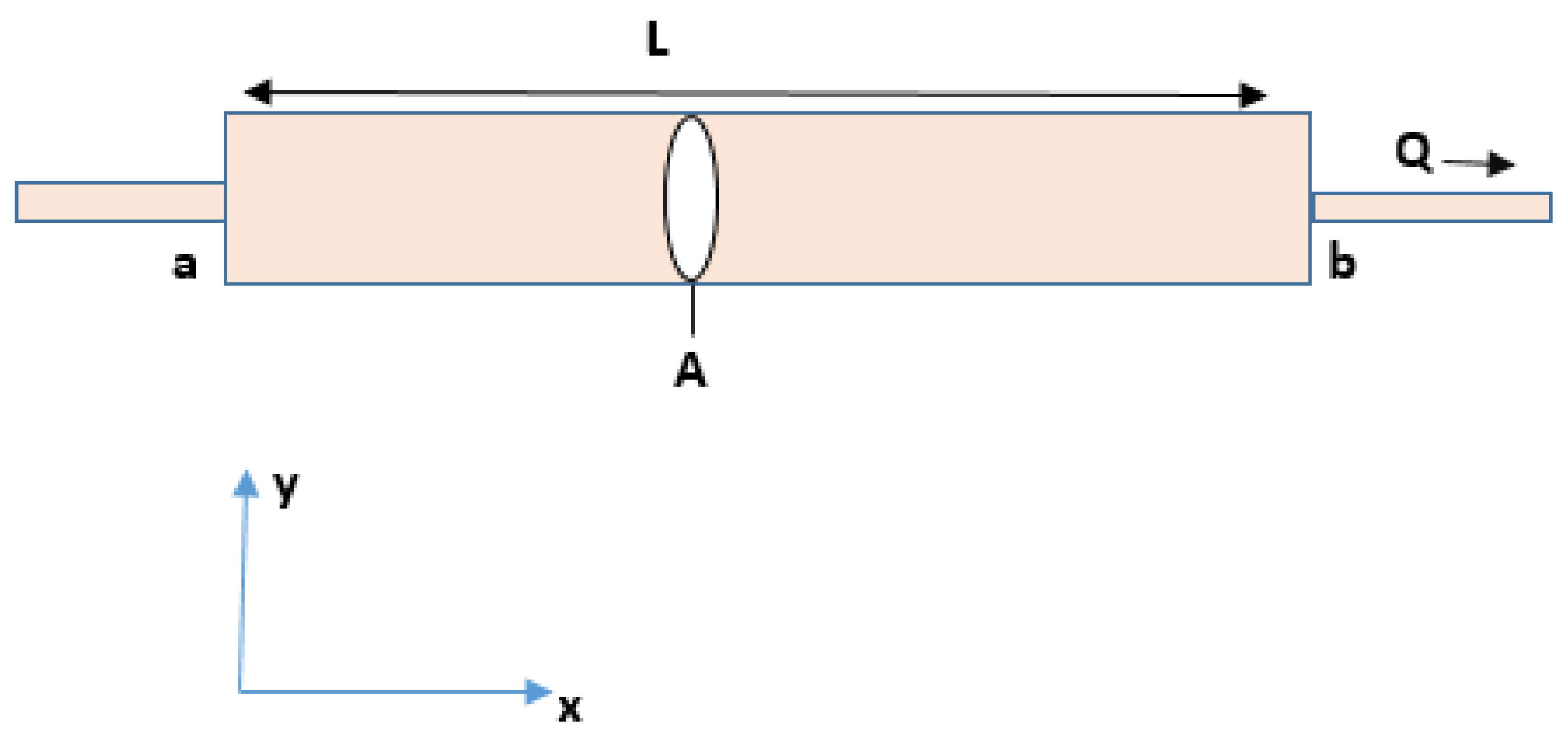

2.1. Physical Description of the Problem

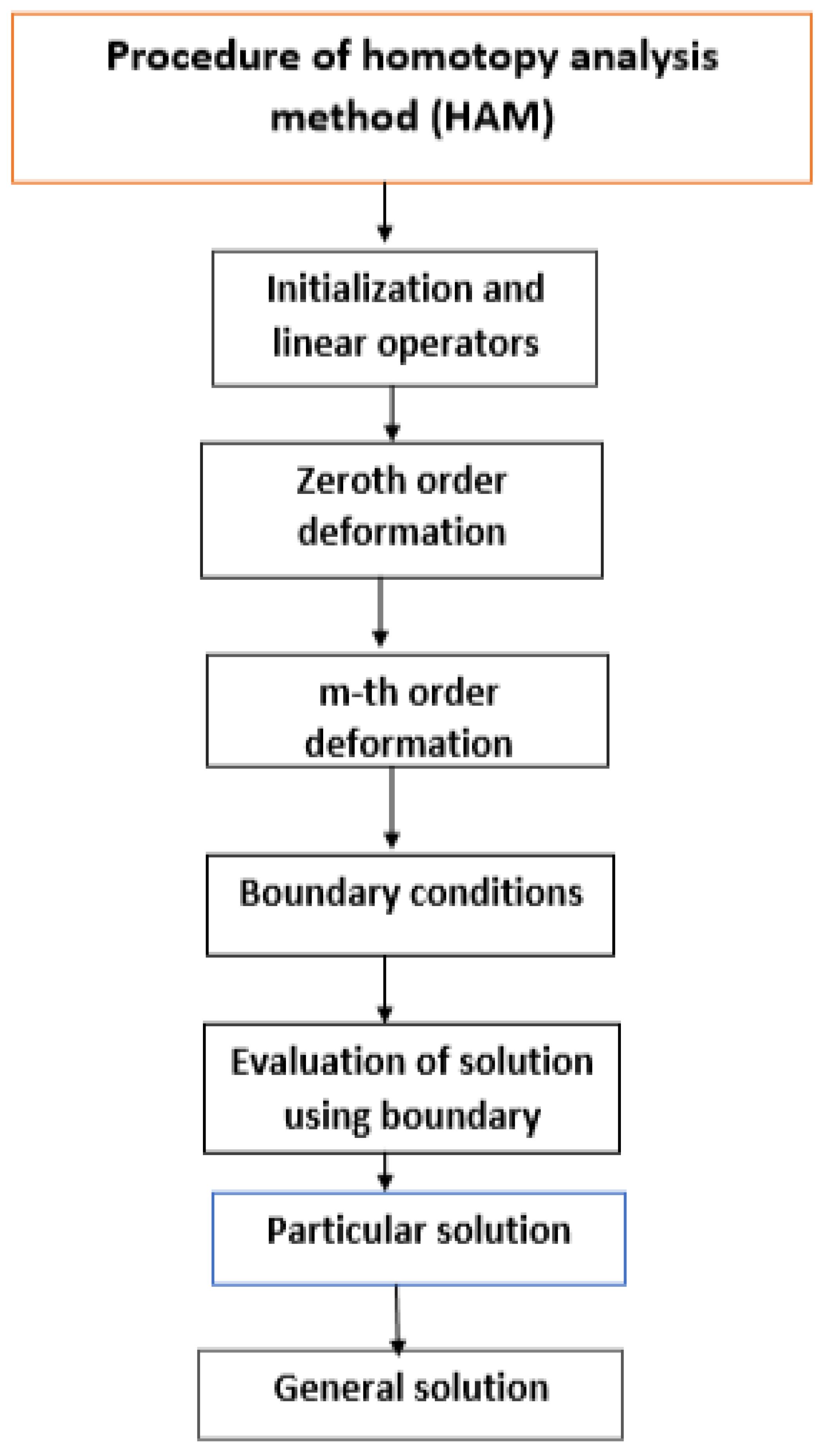

3. Solution of the Problem by HAM

3.1. Deformation Equations of Zeroth Order

3.2. m-th Order Deformation Problems

4. Results and Discussion

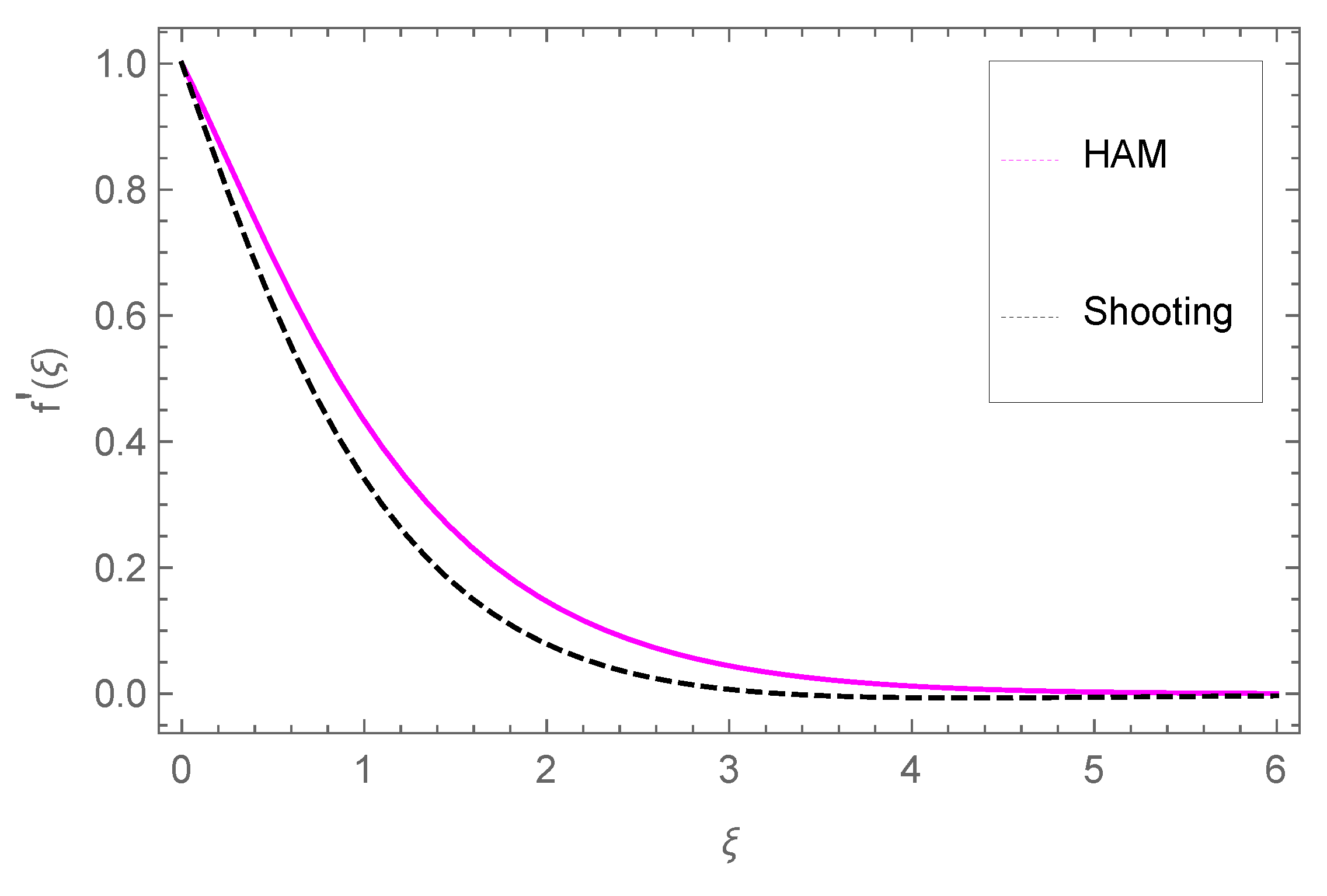

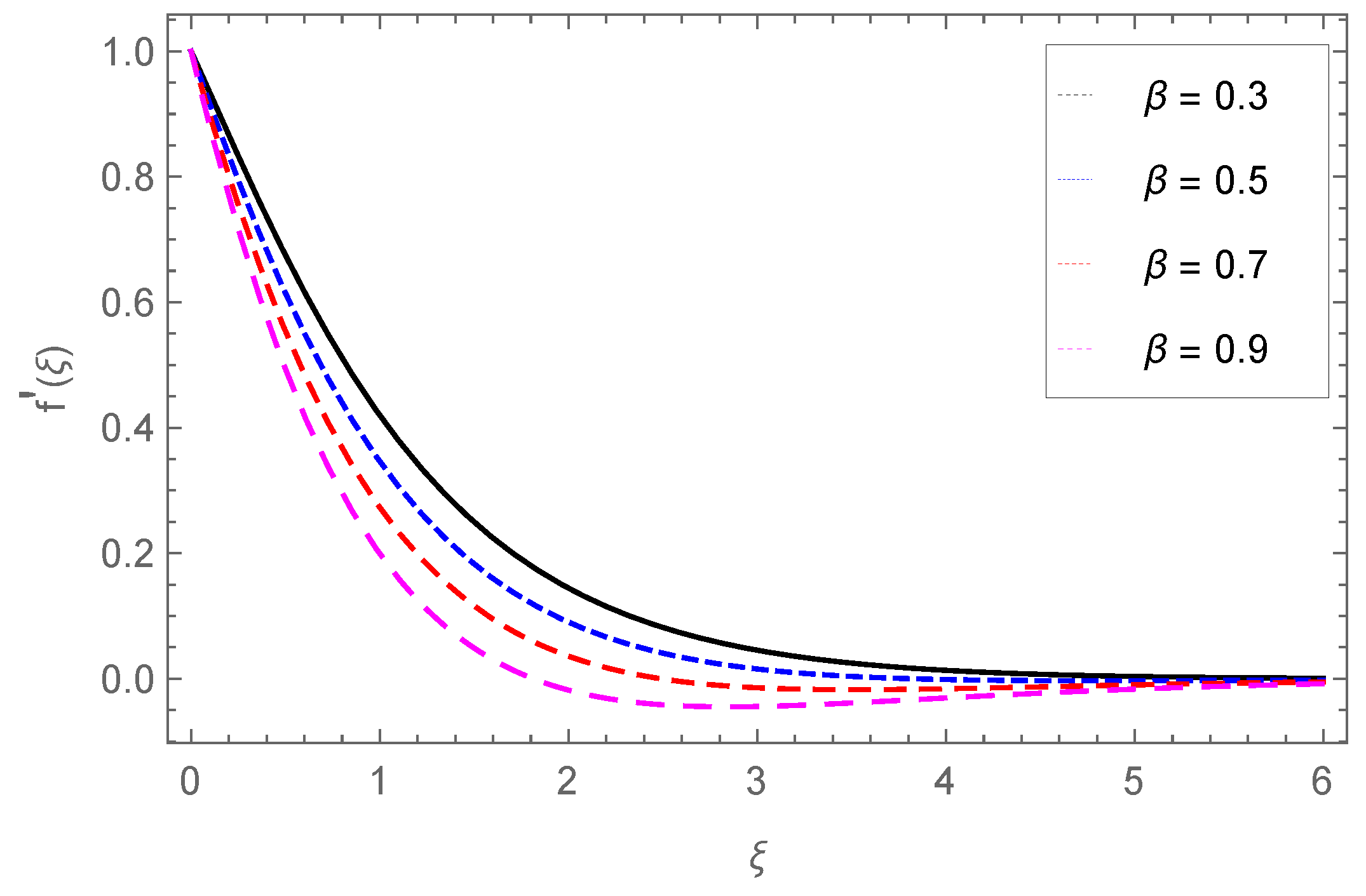

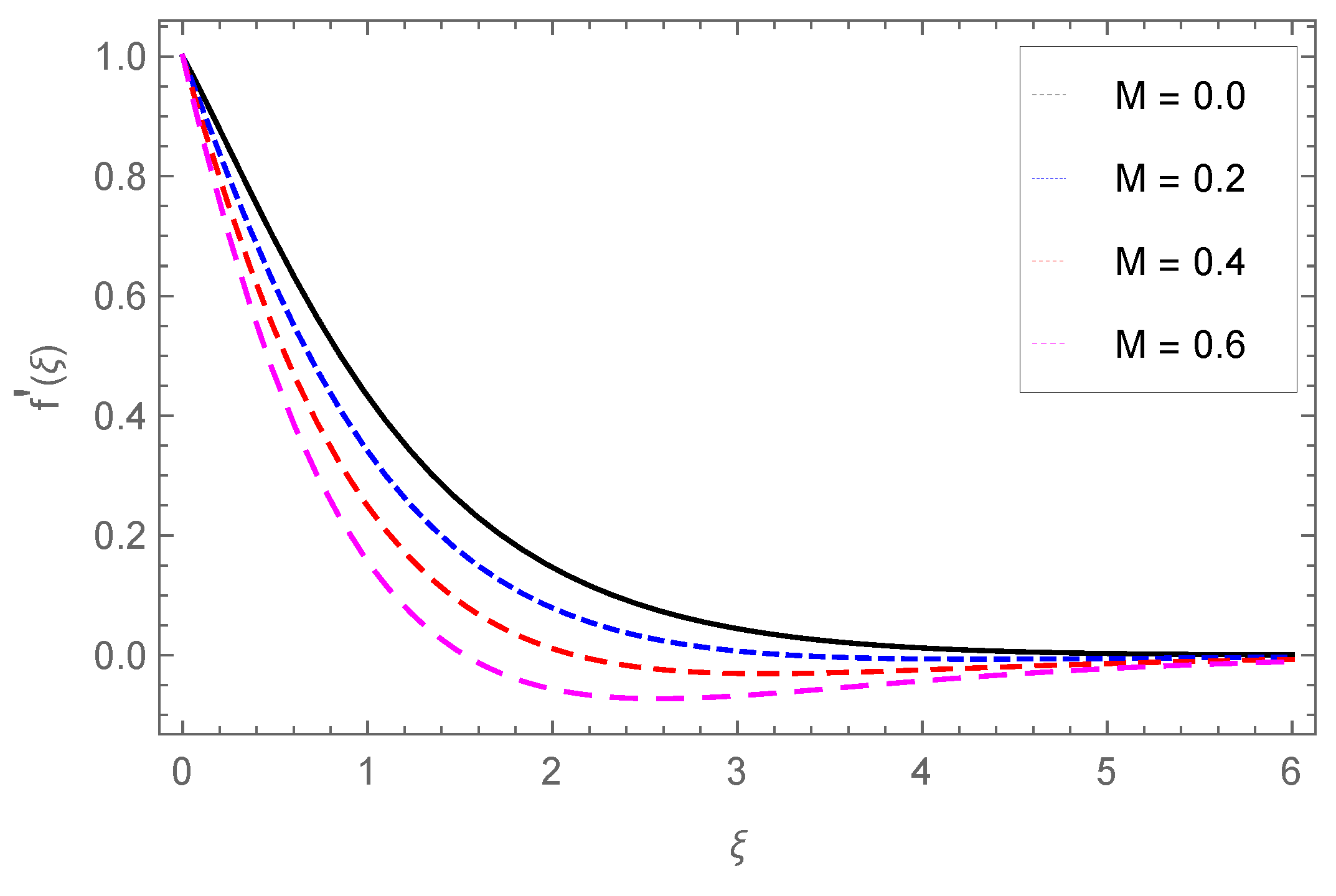

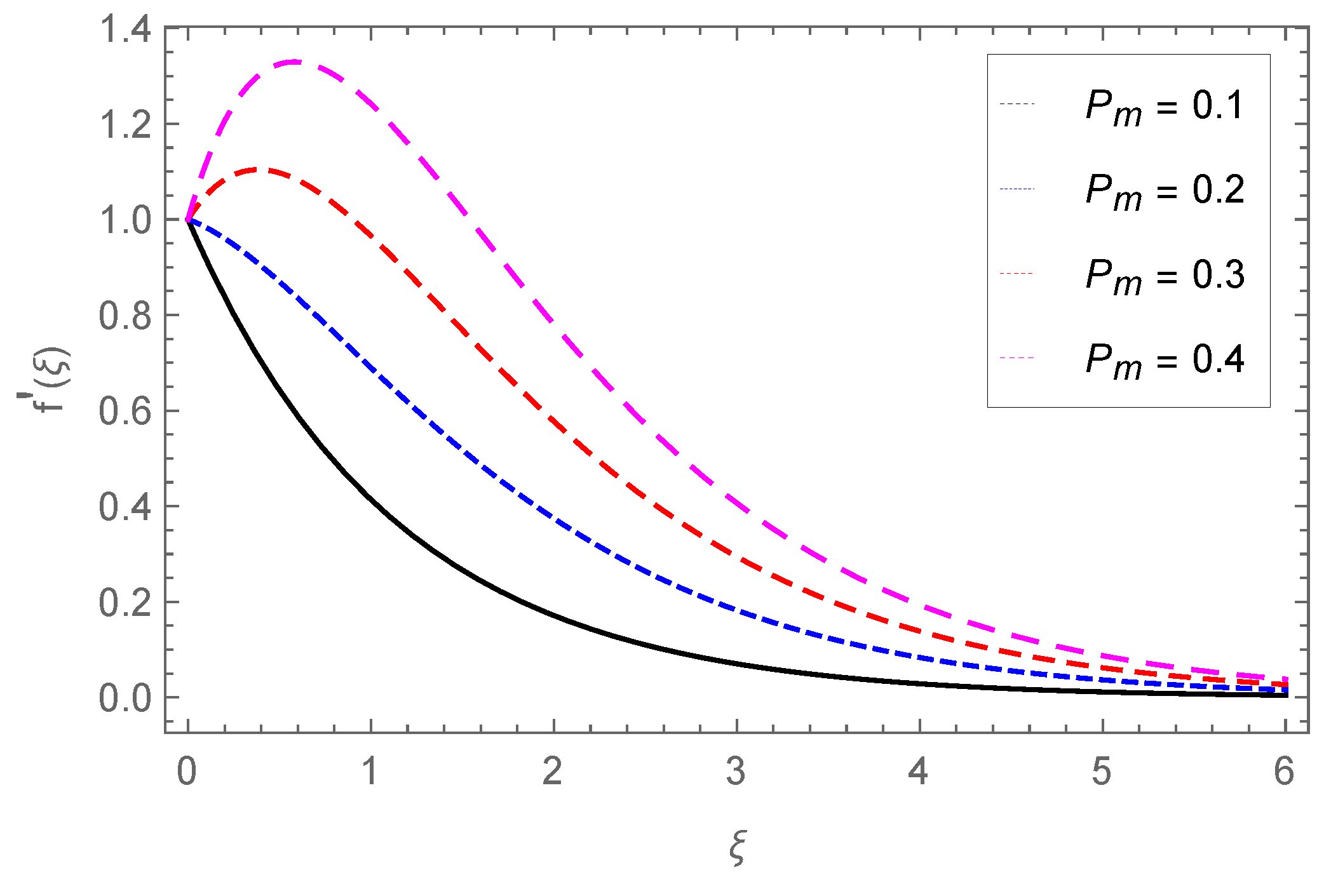

4.1. Velocity Profile

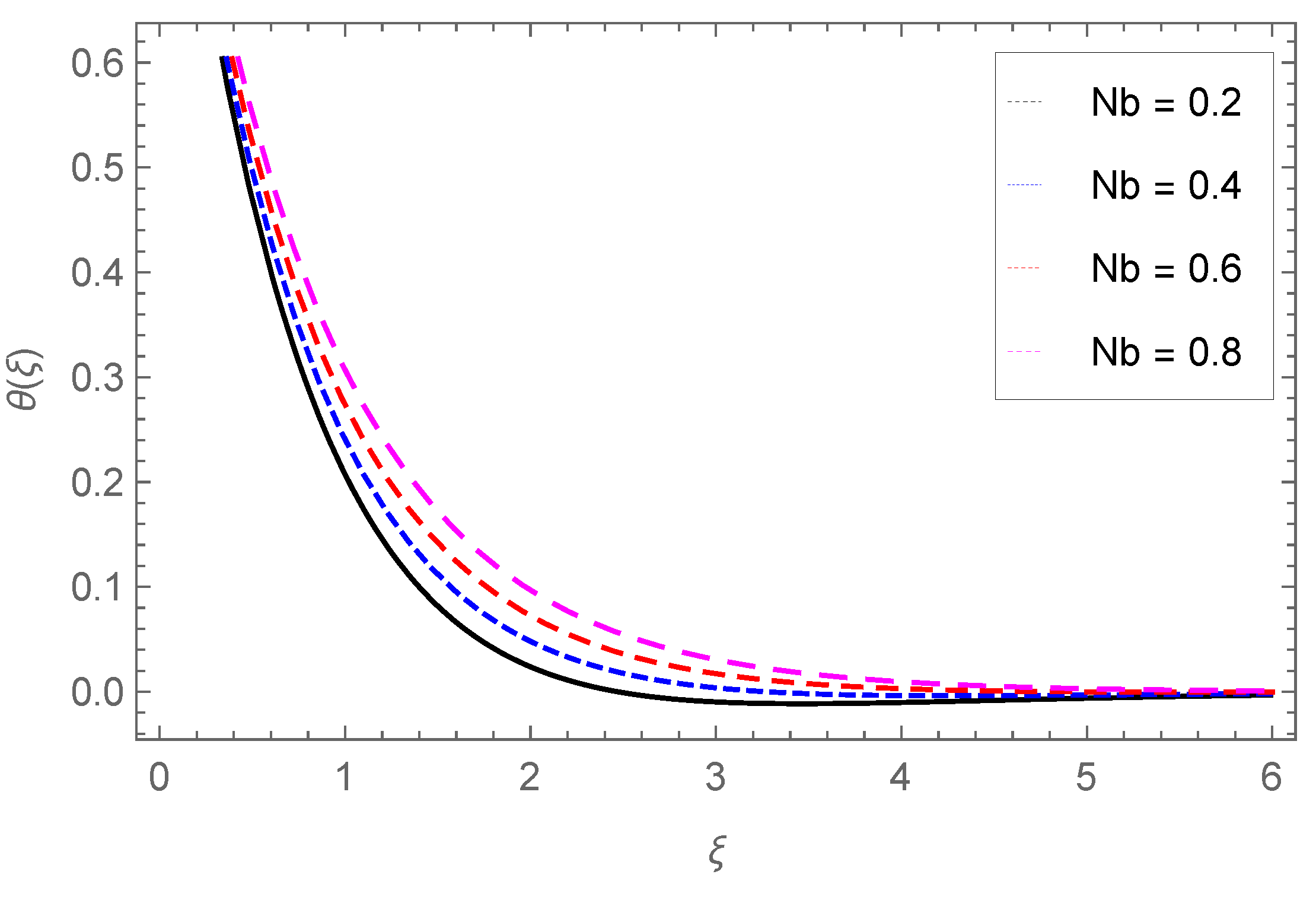

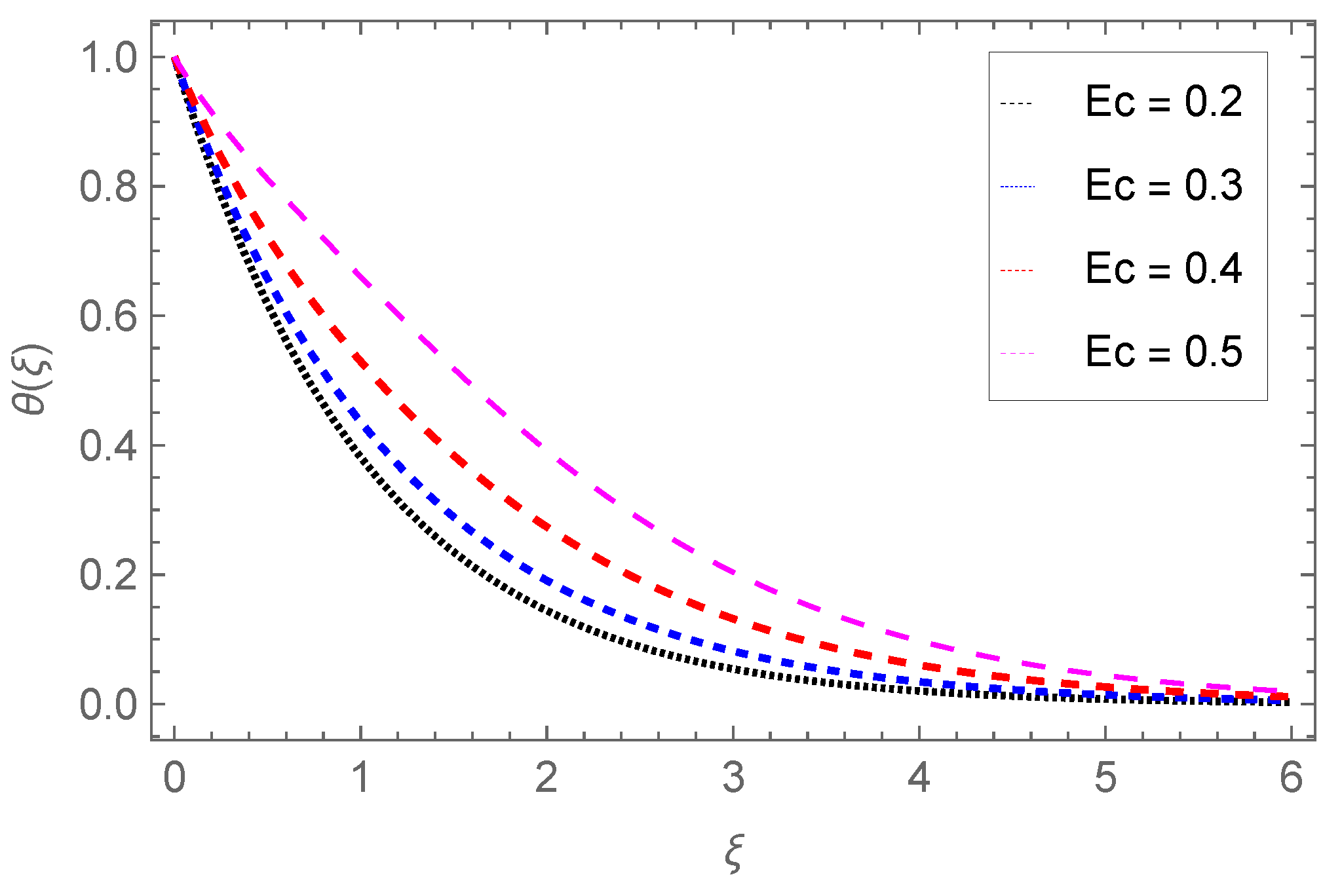

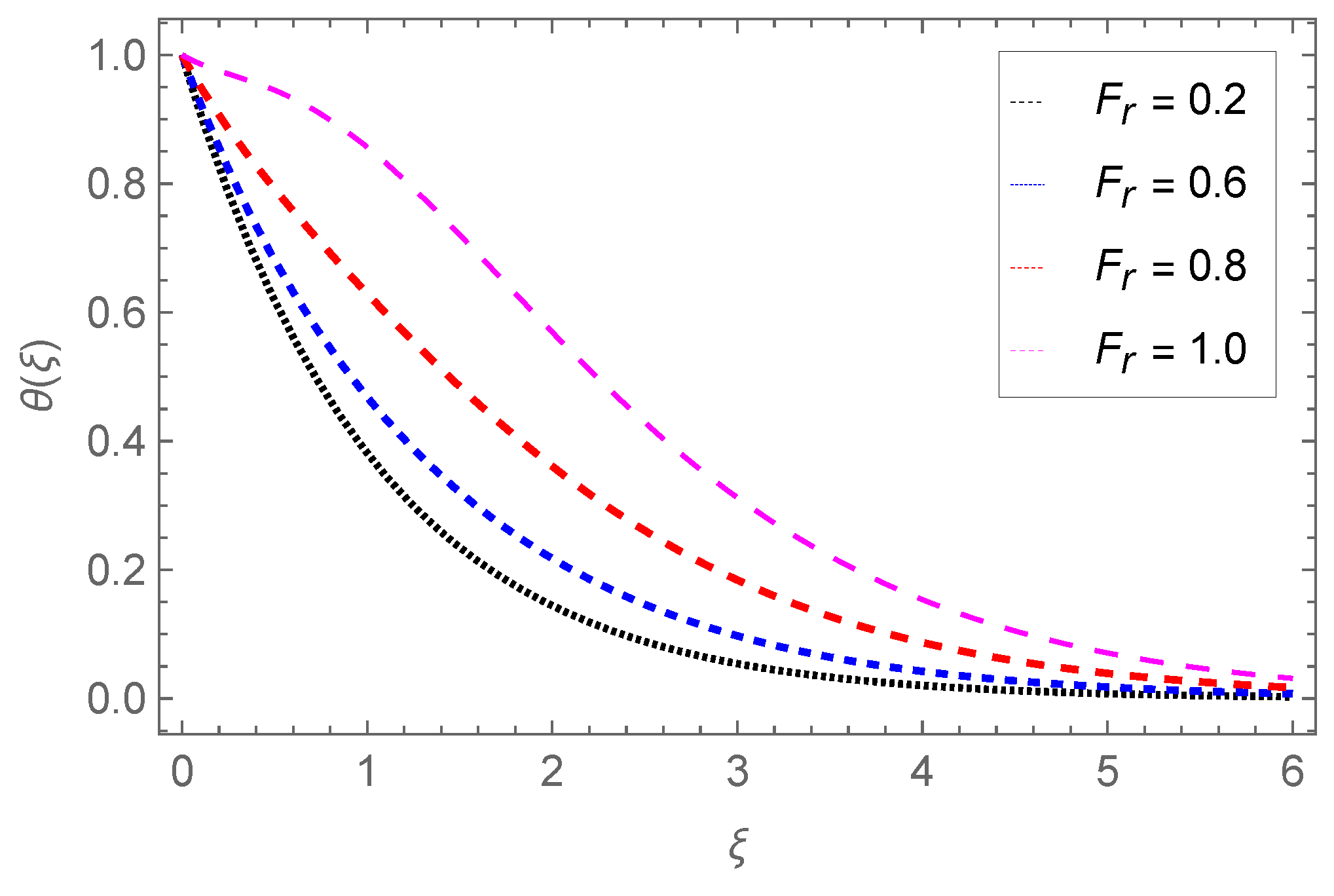

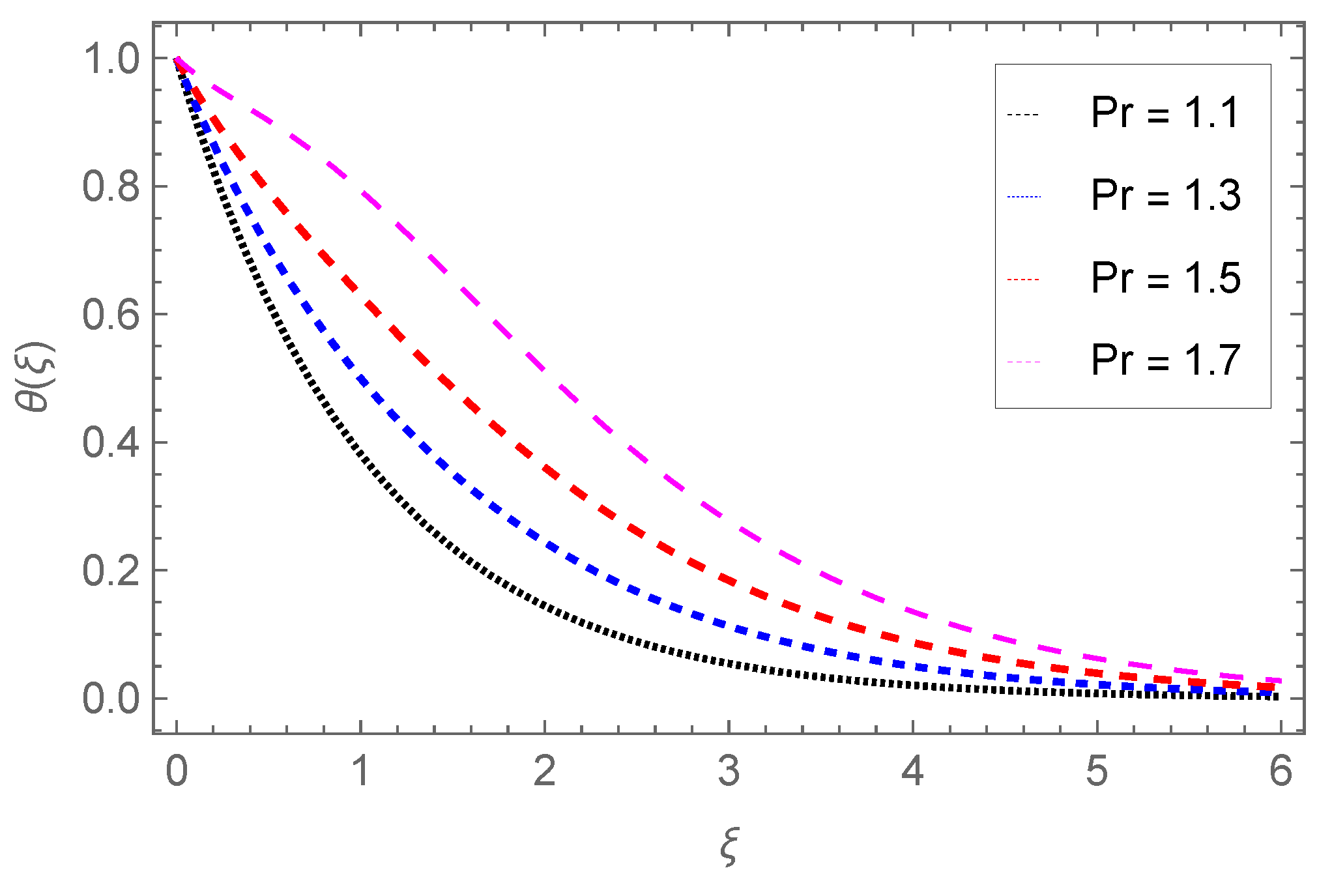

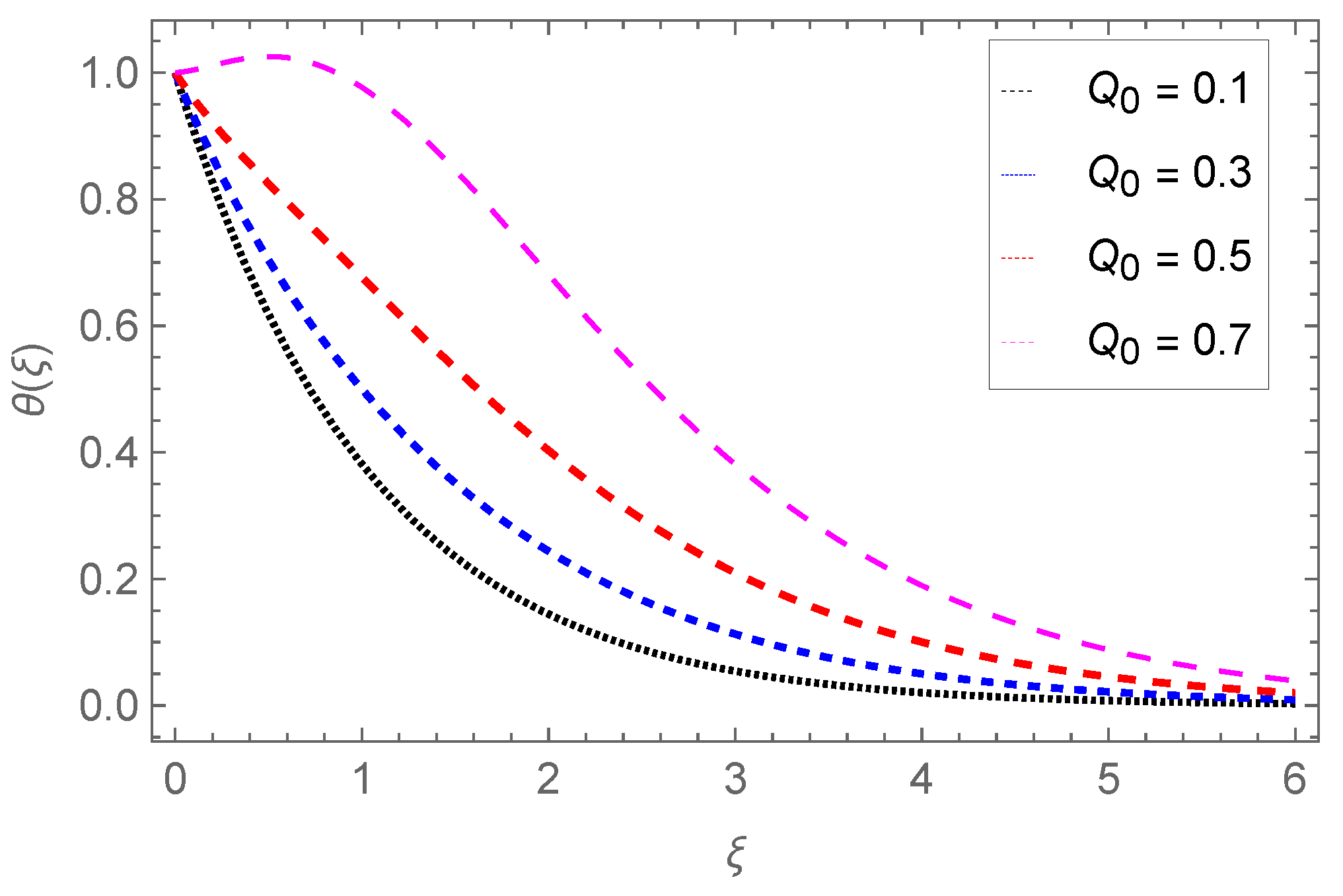

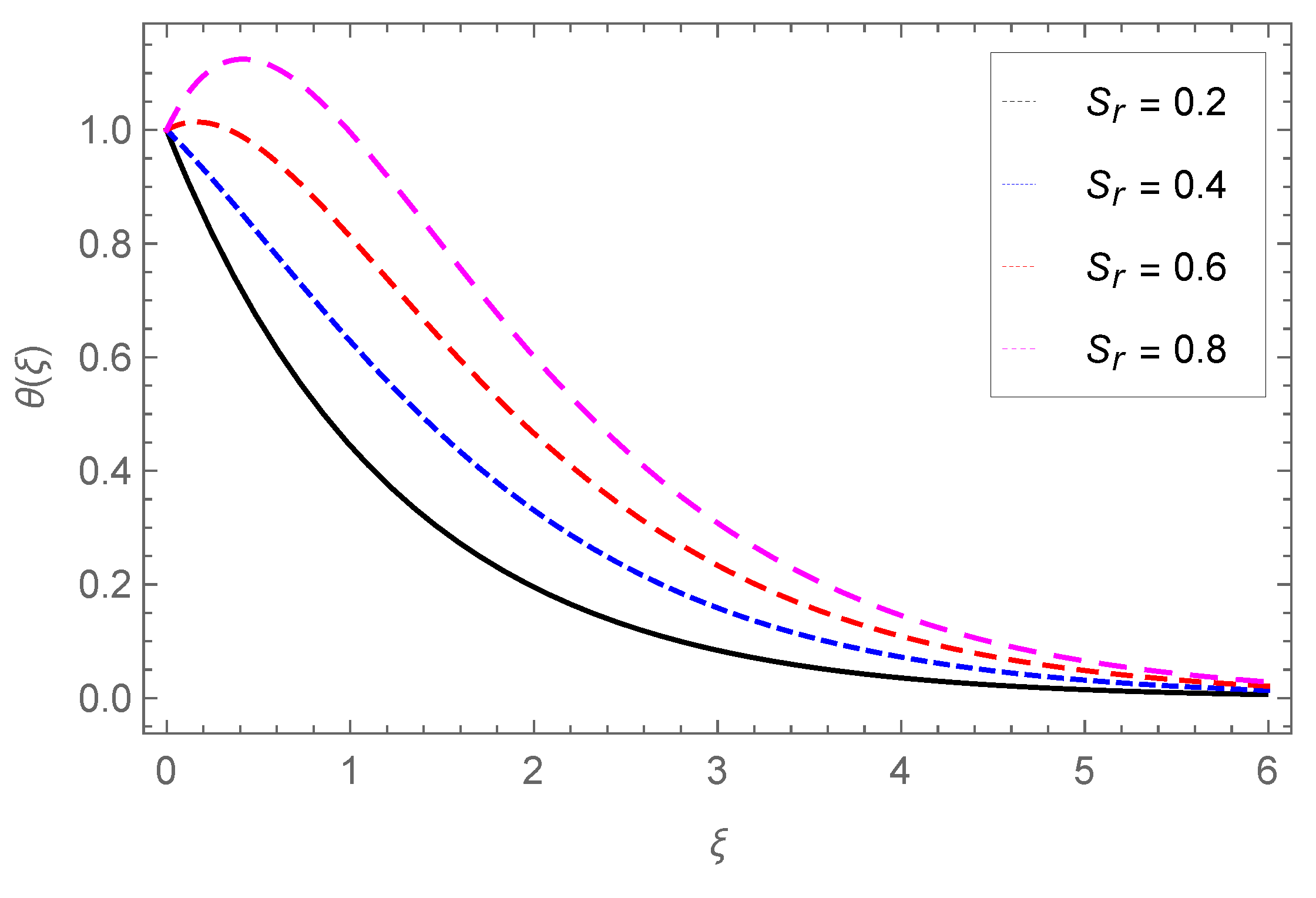

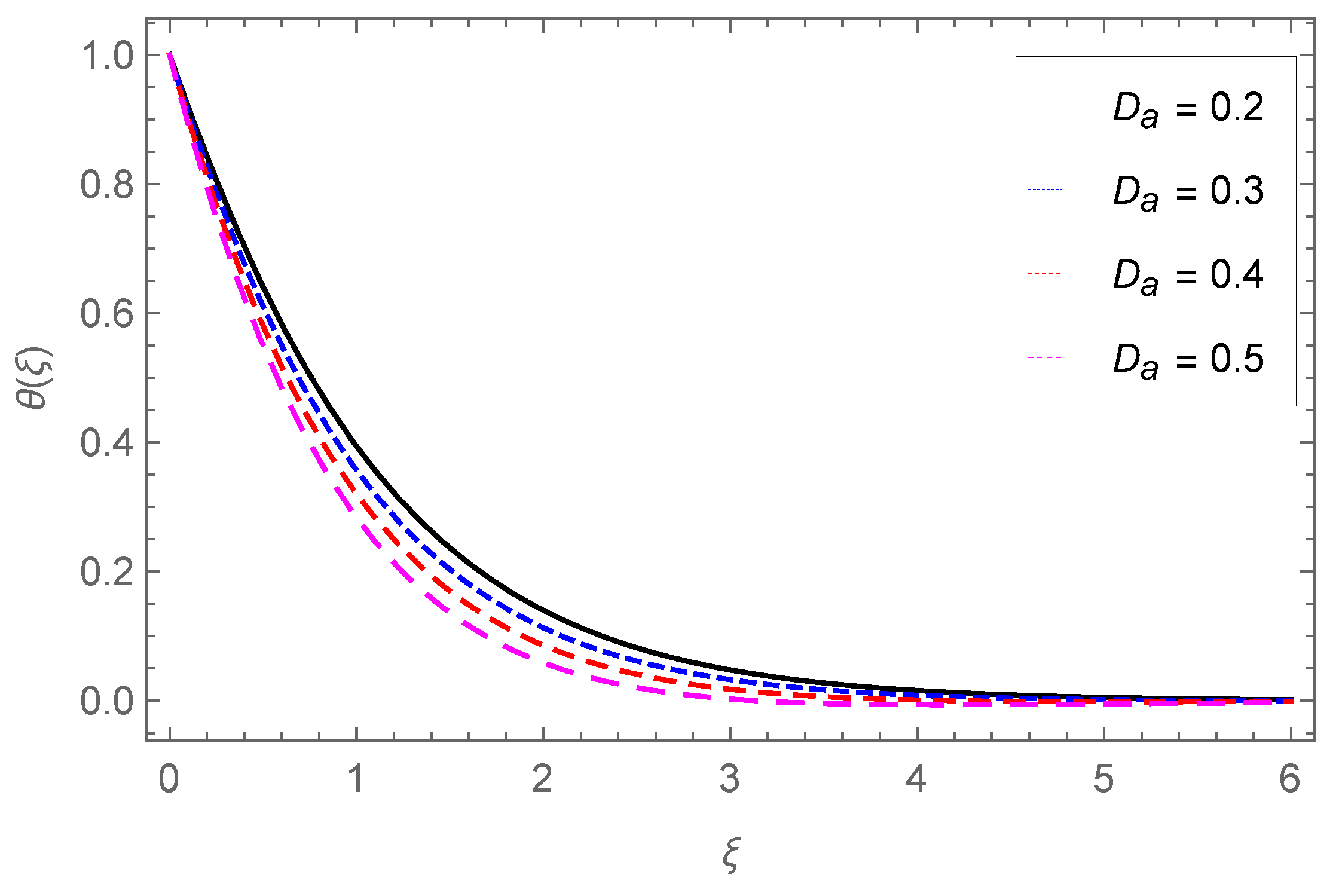

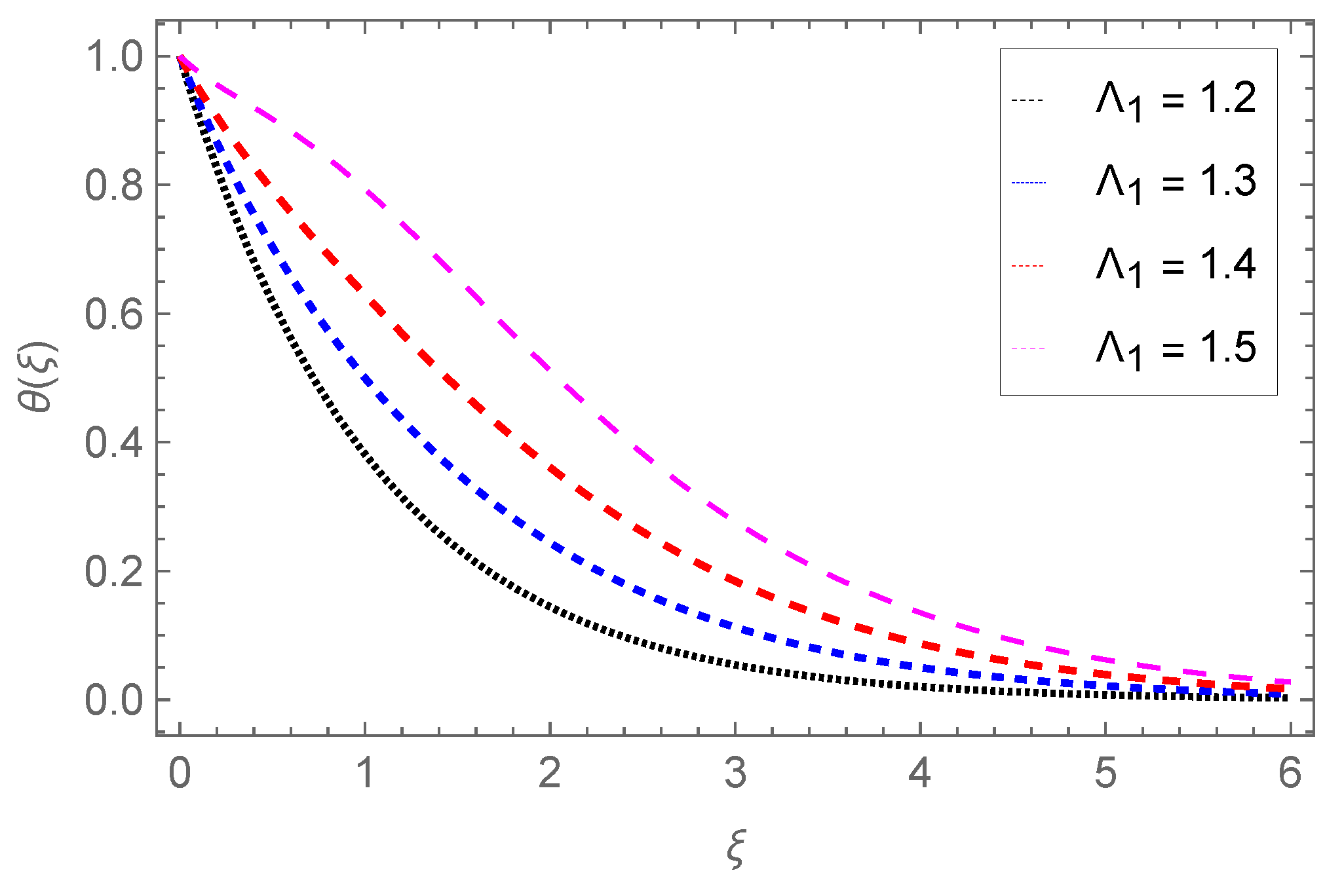

4.2. Temperature Profile

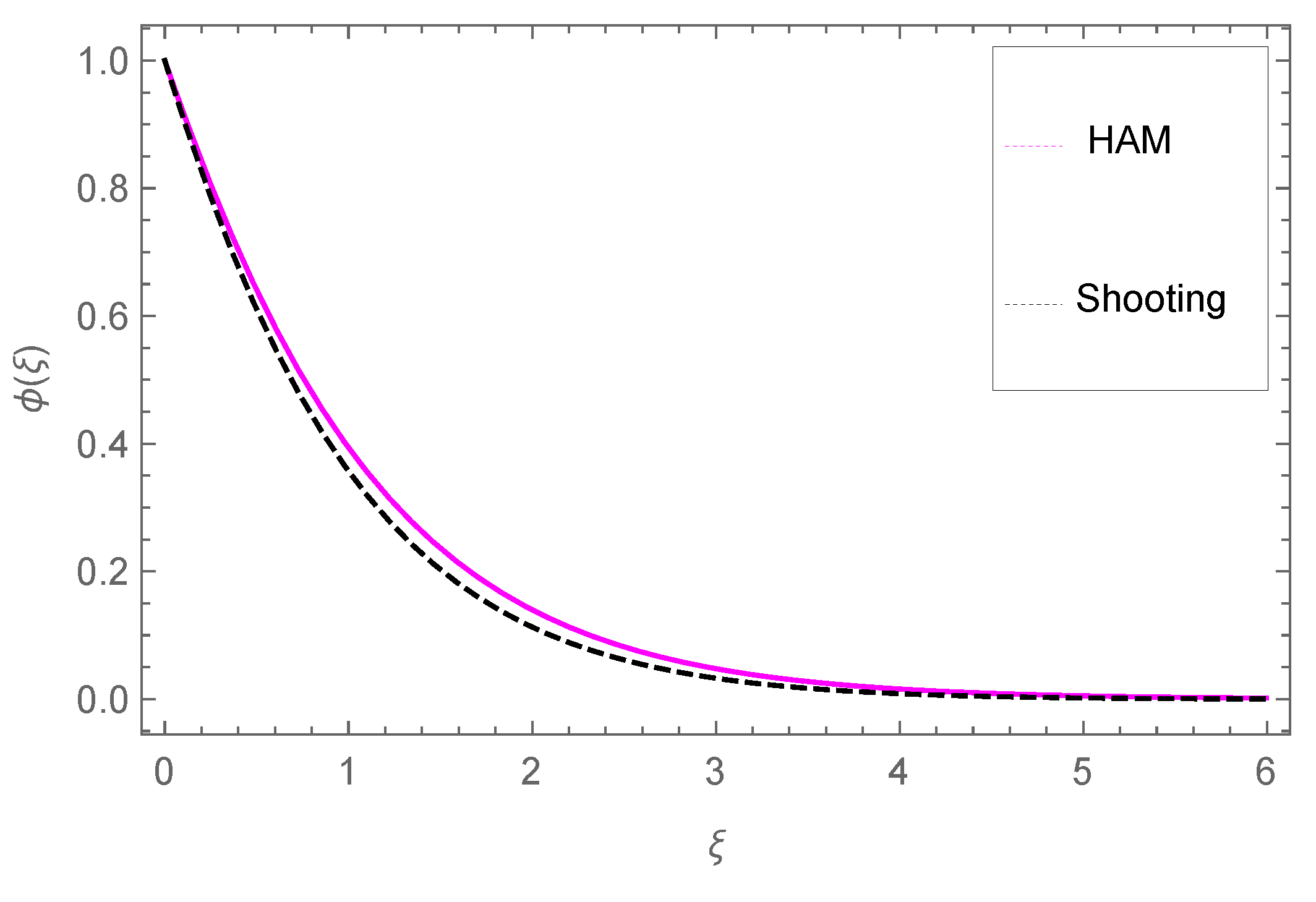

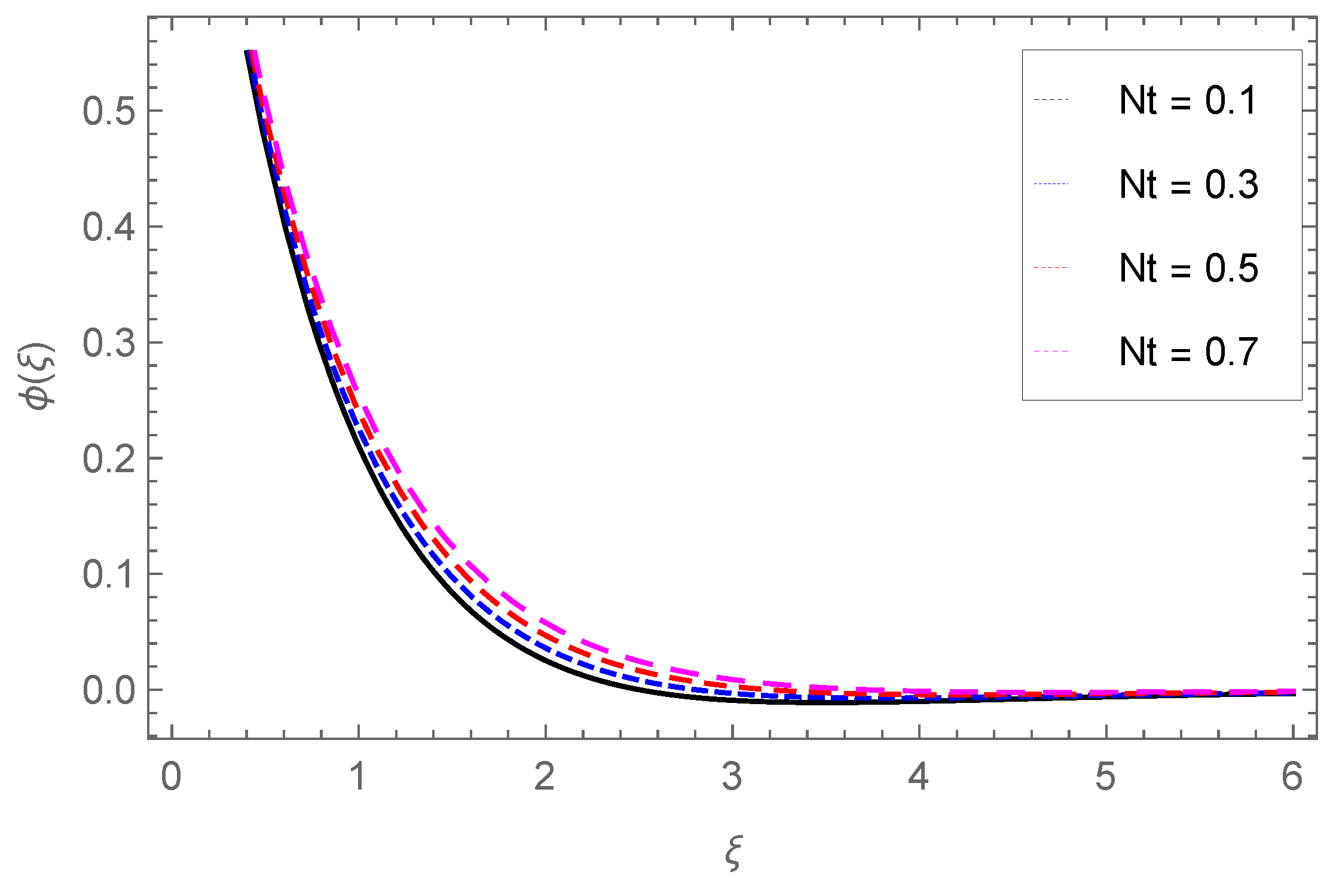

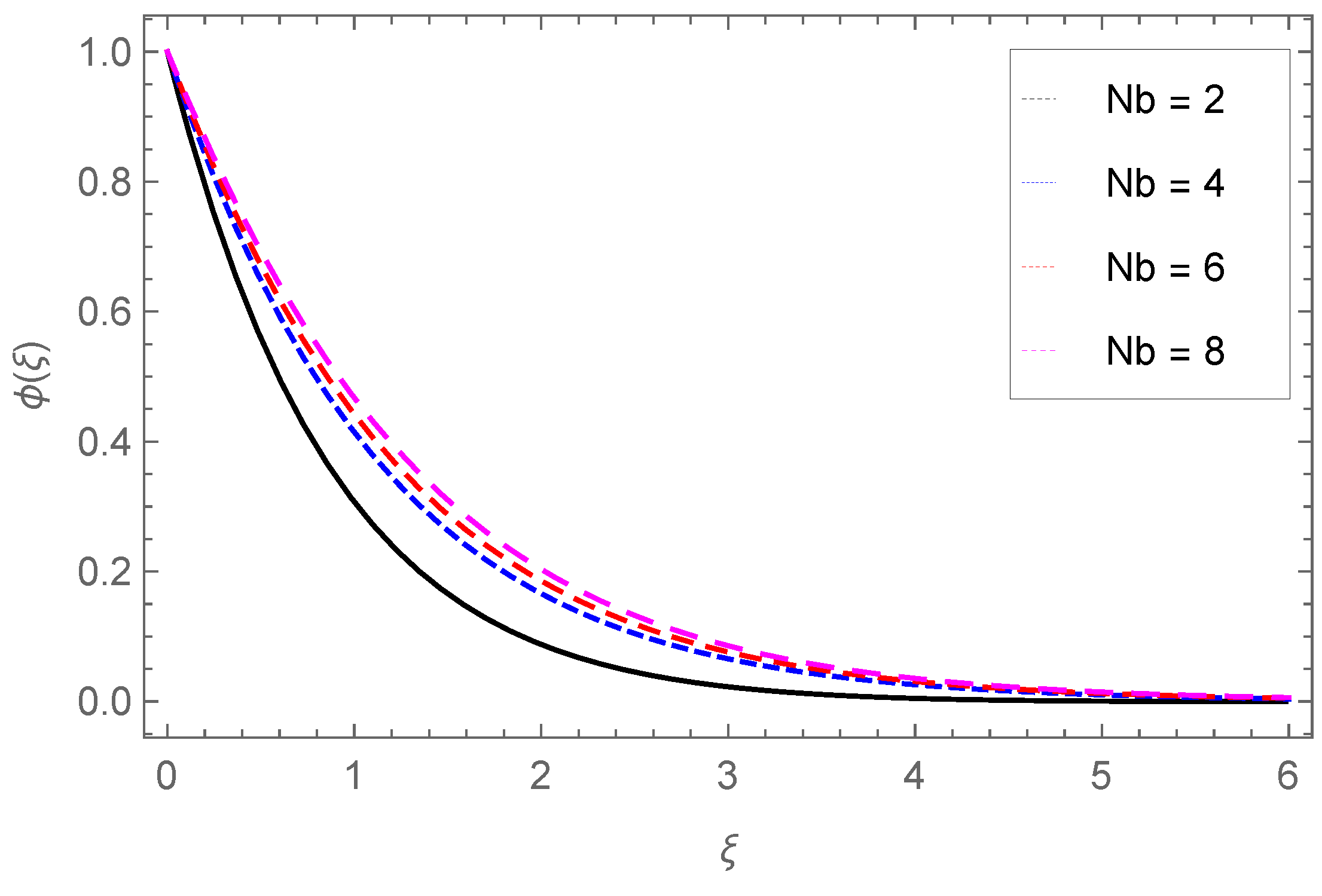

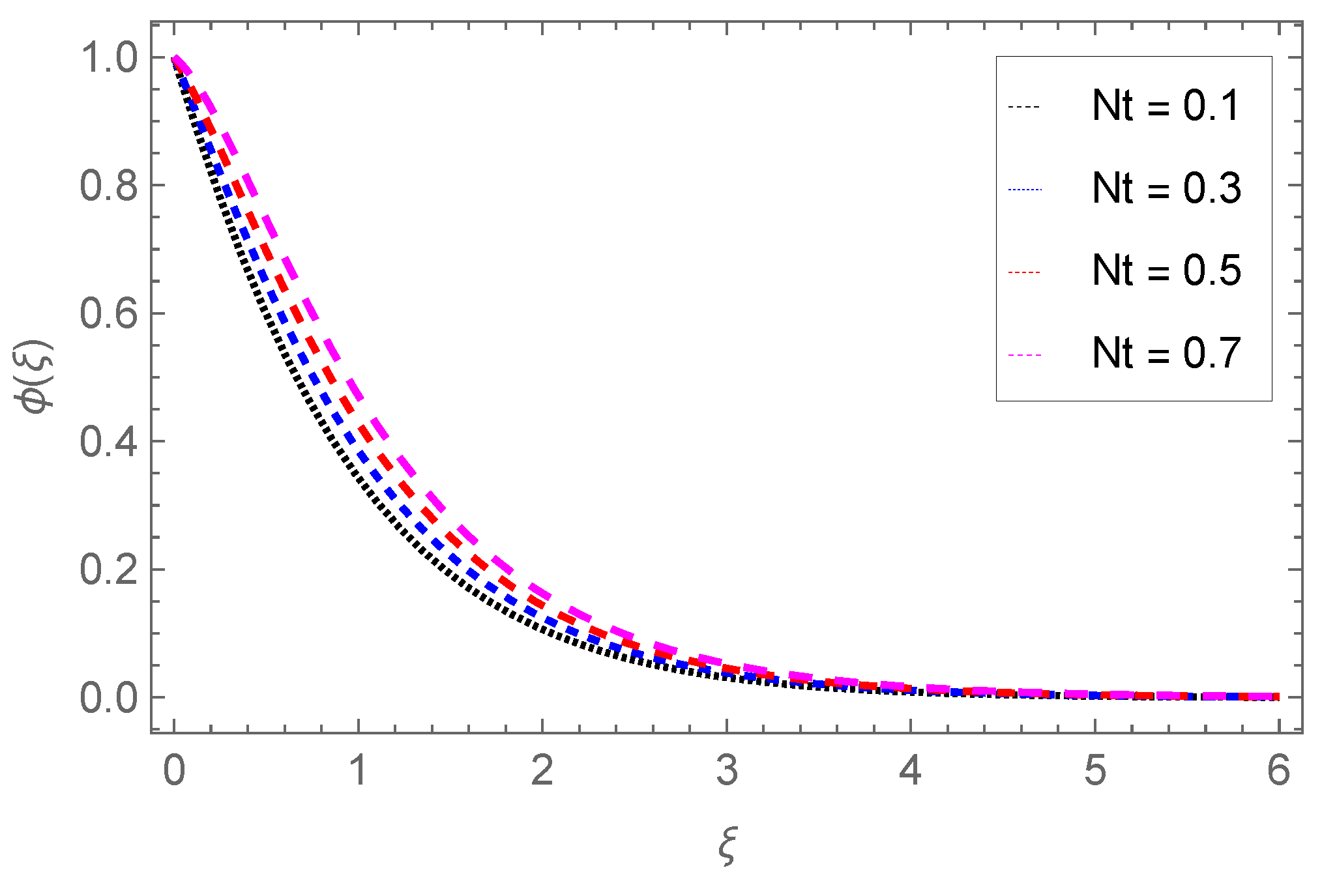

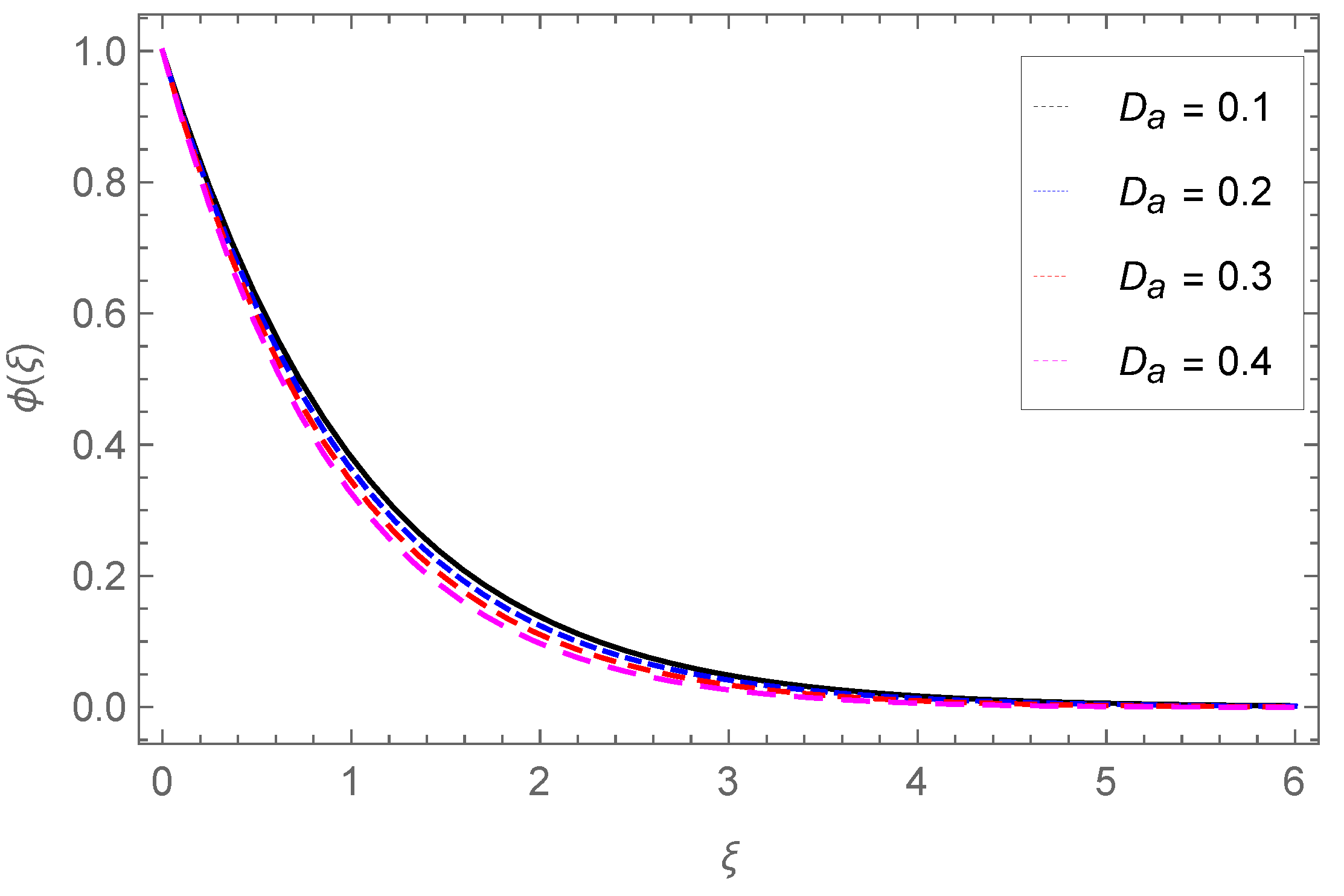

4.3. Concentration Profile

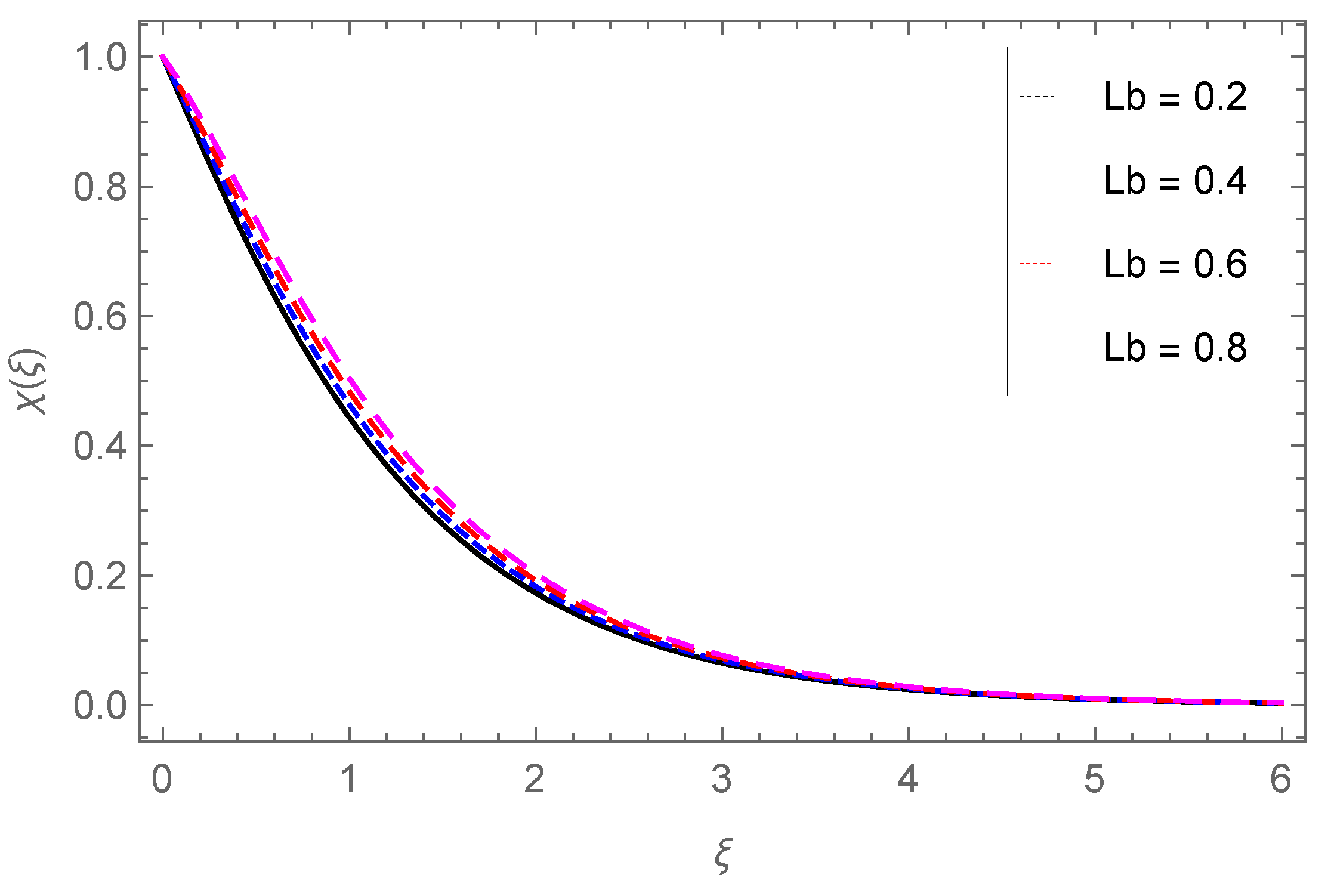

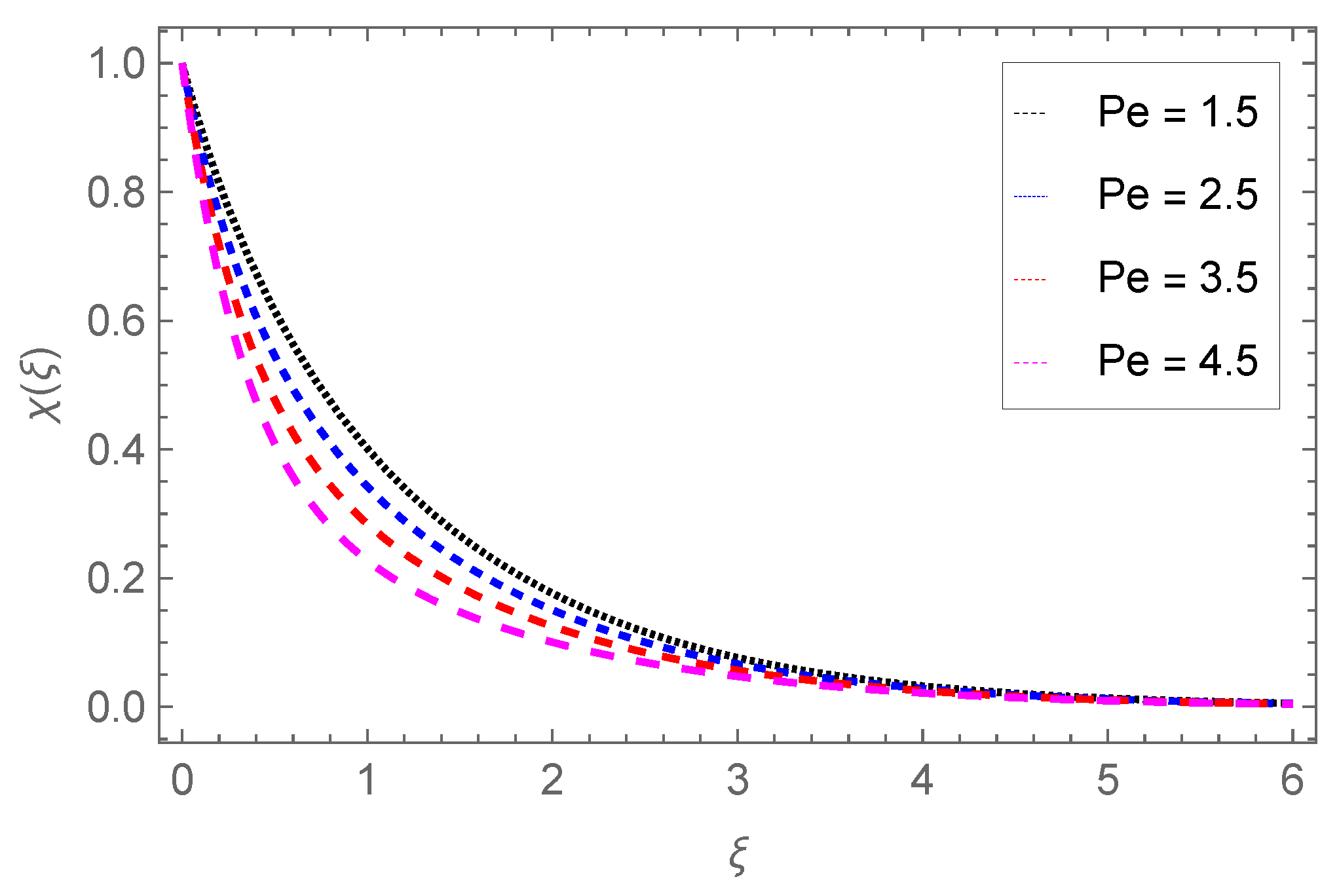

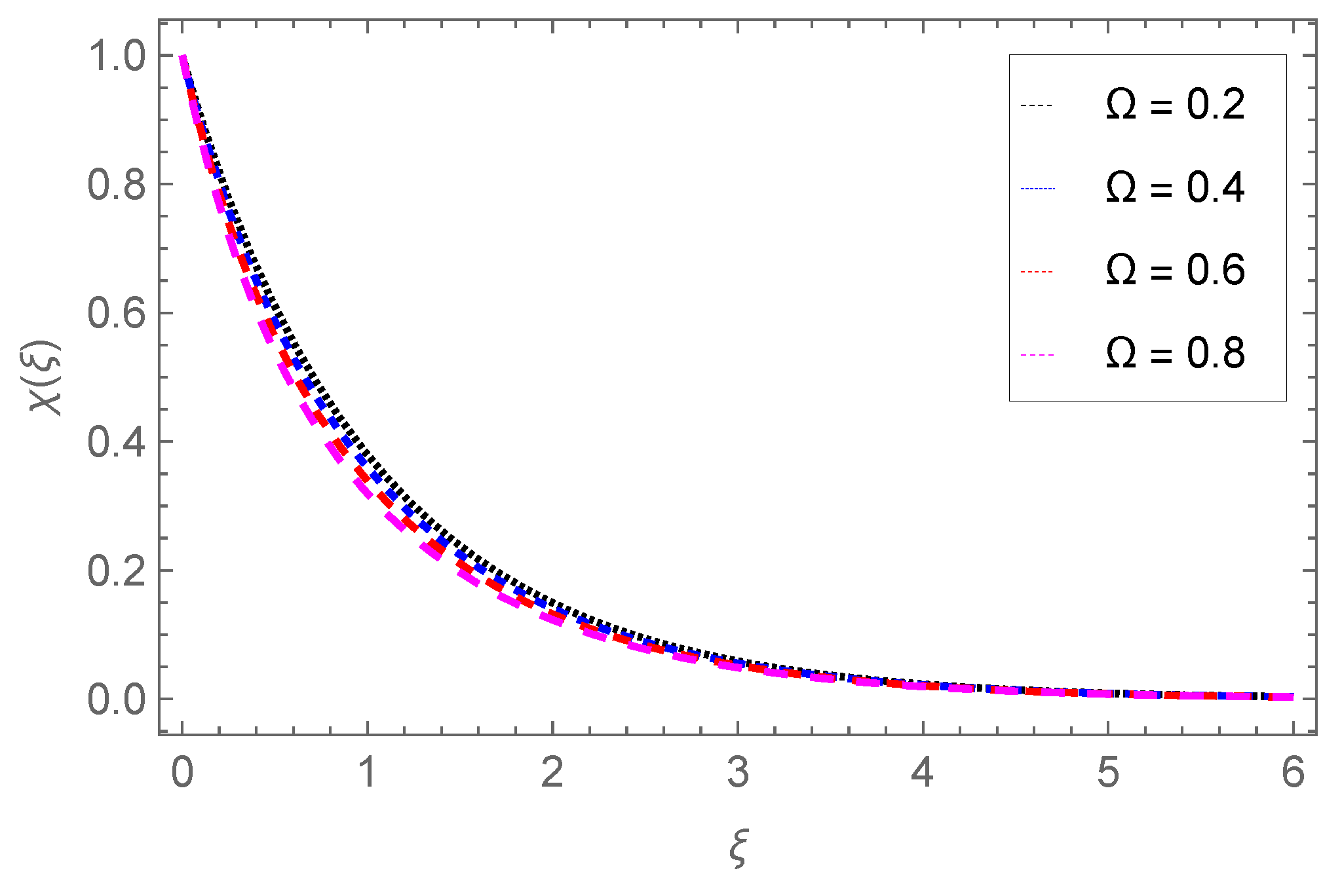

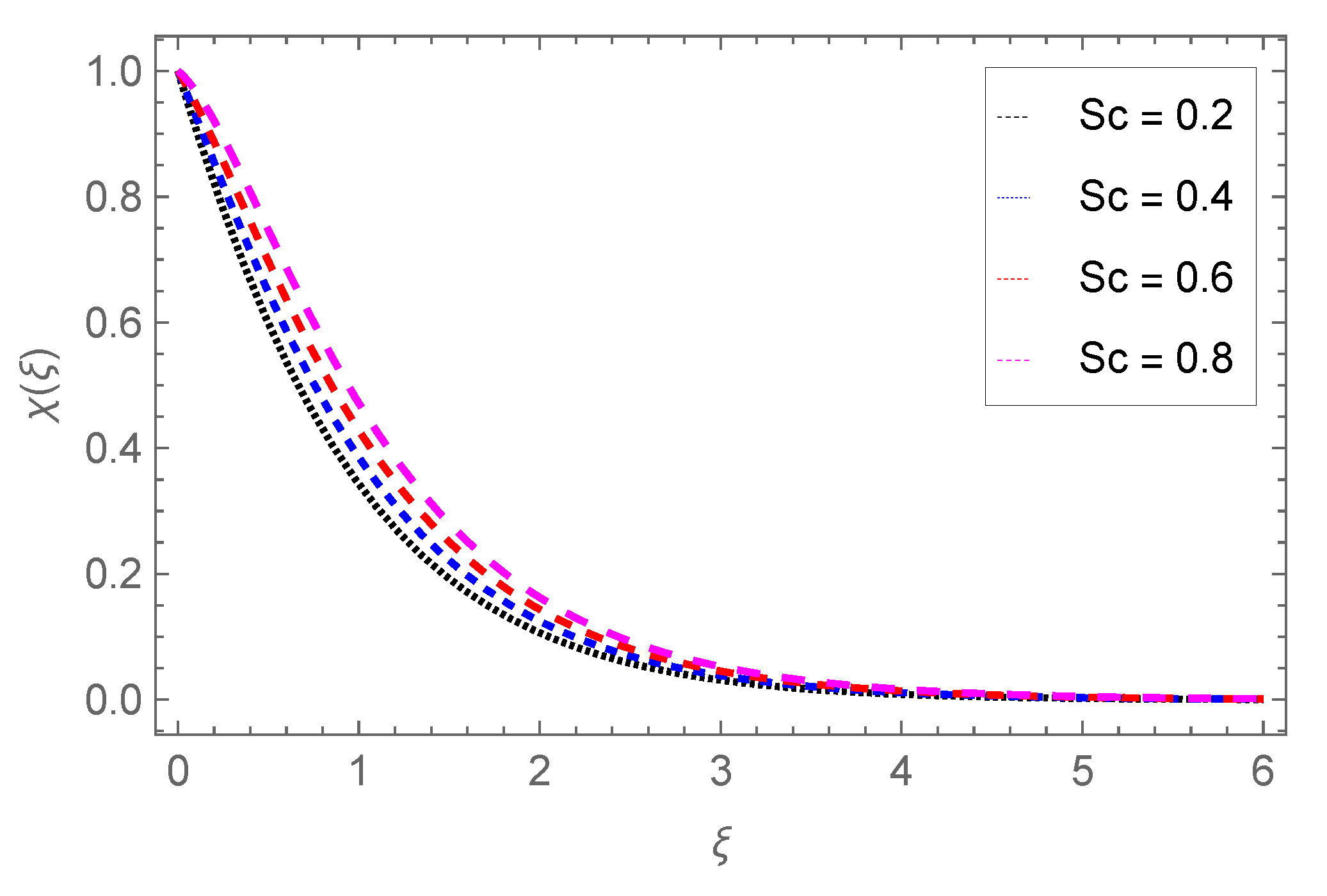

4.4. Gyrotactic Microorganism Profile

4.5. Remarks on Contrasting the Current Collection of Work Against [70].

5. Conclusions and Final Remarks

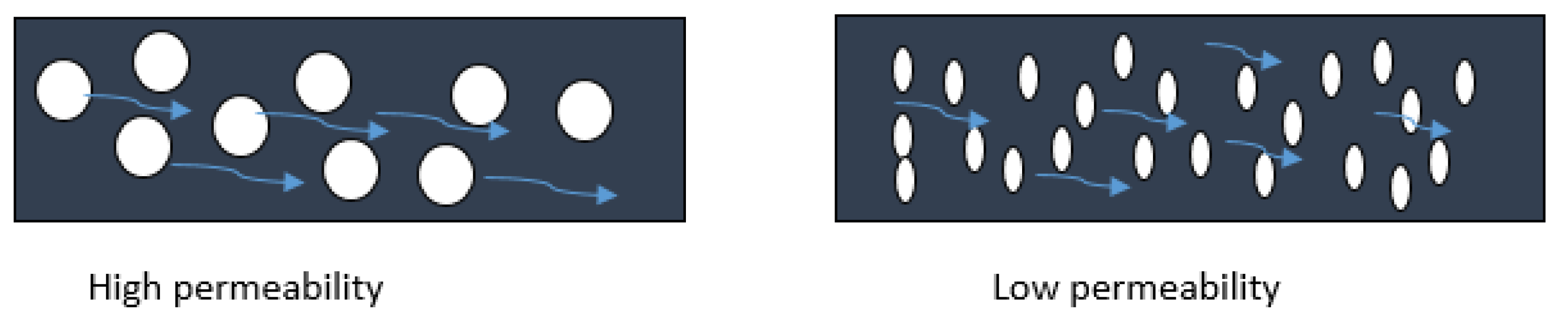

- The velocity profile falls with M and , while fluid movement is enhanced through the porous parameter Pm.

- The temperature profile increases with Nb, Ec, Pr, Sr, Nt, Q0, Fr, and , while it is reduced through the Darcy parameter Da.

- The concentration of nanoparticles is enhanced with Nb, Nt but reduced against the Darcy parameter Da and chemical reactions Sr.

- The concentration of gyrotactic microbes is raised with Lb, Pe, Sc but reduced with the concentration difference parameter .

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| M | Magnetic field parameter | Concentration difference parameter | |

| Nt | Thermophoresis parameter | Nb | Brownian motion parameter |

| Wce | Maximum cell swimming speed | Lb | Bioconvection Lewis number |

| Prandtl number | Eckert number | ||

| B0 | Magnetic field strength | T∞ | Ambient temperature (k) |

| N | Concentration of microorganisms | (u,v) | Components of velocity () |

| DT | Thermophoretic diffusion coefficient | C∞ | Ambient concentration |

| b | Chemotaxis constant | Cw | Surface concentration |

| T | Fluid temperature (k) | C | Concentration |

| DB | Brownian diffusion coefficient | Tw | Temperature on wall (k) |

| Dn | Diffusion of microbes | f | Velocity profile |

| a | Dimensional constant | N∞ | Ambient concentration of microbes |

| cp | Specific heat at constant pressure | Axis coordinates (m) | |

| Thermal conductivity | Nw | Reference concentration of microbes | |

| (a, b) | Dimensional constants | Pe | Bioconvection Peclet number |

| Biot number | Skin friction coefficient | ||

| Porosity parameter | Sc | Schmidt number | |

| Darcy parameter | Fr | Forchheimer parameter | |

| Heat source parameter | Sr | Chemical reaction | |

| Greek Letters | |||

| Dynamic viscosity of nanopartcles | Kinematic viscosity of nanopartcles | ||

| Density of nanoparticle() | Electrical conductivity | ||

| Similarity variable | Stefan Boltzmann Constant fluid | ||

| Concentration profile | Temperature profile | ||

| Casson fluid parameter | Gyrotactic microorganisms profile | ||

| Stretching ratio parameter | Plastic dynamic viscosity |

References

- Alwawi, F.A., Alkasasbeh, H.T., Rashad, A.M., Idris, R.: MHD natural convection of sodium alienate Casson nanofluid over a solid sphere. Results in Physics. 16, 102818 (2020).

- Mukhopadhyay, S.: Effects of thermal radiation on Casson fluid flow and heat transfer over an unsteady stretching surface subjected to suction/blowing. Chinese Physics B. 22(11), 114702 (2013).

- Mabood, F., Das, K.: Outlining the impact of melting on MHD Casson fluid flow past a stretching sheet in a porous medium with radiation. Heliyon. 5(2), e01216 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z., Kumam, P., Deebani, W.: Radiative MHD casson nanofluid flow with activation energy and chemical reaction over past nonlinearly stretching surface through Entropy generation. Scientific Report. 10, 4402 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Puneeth, V., Khan, M.I., Narayan, S.S., El-Zahar, E.R., Guedri, K.: The impact of the movement of the gyrotactic microorganisms on the heat and mass transfer characteristics of Casson nanofluid. Waves Random Complex Media. 1–24 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S., Haq, R.U., Lee, C.: MHD Flow of a Casson Fluid over an Exponentially Shrinking Sheet. Scientia Iranica. 19, 1550-1553 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Alali, E., Megahed, A.M.: MHD dissipative Casson nanofluid liquid film flow due to an unsteady stretching sheet with radiation influence and slip velocity phenomenon. Nanotechnology. Rev. 11, 463– 472 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dawar, A., Shah, Z., Alshehri, H.M., Islam, S., Kumam, P.: Magnetized and nonmagnetized Casson fluid flow with gyrotactic microorganisms over a stratified stretching cylinder. Sci Rep. 11, 16376 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mkhatshwa, M.P., Motsa, S., Sibanda, P.: MHD bioconvective radiative flow of chemically reactive Casson nanofluid from a vertical surface with variable transport properties. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43, 3170-3188 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Darcy, H.P.C.: Les Fontsines Publiques de la Ville de Dijon. Victor Dalmont, Paris. (1856).

- Li, S., Raghunath, K., Alfaleh, A., Ali, F., Zaib, A., Khan L.M.: Effects of activation energy and chemical reaction on unsteady MHD dissipative Darcy-Forchheimer squeezed flow of Casson fluid over horizontal channel. Sci Rep. 13(1), 2666 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Nayak, M.K., Shaw, S., Khan, M.I., Makinde, O., Chu, Y.M., Khan, S.U.: Inter-facial layer and shape effects of modified Hamilton’s Crosser model in entropy optimized Darcy–Forchheimer flow. Alex. Eng. J. 60, 4067–4083 (2021).

- Bilal, S., Sohail, M., Naz, R.: Heat transport in the convective Casson fluid flow with homogeneous heterogeneous reactions in Darcy-Forchheimer medium, Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 15, 1170–1189 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Naz, R., Tariq, S., Sohail, M., Shah, Z.: Investigation of entropy generation in stratified MHD Carreau nanofluid with gyrotactic microorganisms under Von Neumann similarity transformations, Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 135, 1–22 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Naz, R., Mabood, F., Sohail, M., Tlili, I.: Thermal and species transportation of Eyring-Powell material over a rotating disk with swimming microorganisms: applications to metallurgy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 5577–5590 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Rasool, G., Shah, N.A., El-Zahar, E.A., Wakif, A.: Numerical investigation of EMHD nanofluid flows over a convectively heated riga pattern positioned horizontally in a Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium: Application of passive control strategy and generalized transfer laws. Waves Random Complex Media. 1–20 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Kairi, R.R., Shaw, S., Roy, S., Raut, S.: Thermosolutal marangoni impact on bioconvection in suspension of gyrotactic microorganisms over an inclined stretching sheet. J. Heat Transf. 143, 031201 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mkhatshwa, M.P., Motsa, S., Sibanda, P.: MHD bioconvective radiative flow of chemically reactive Casson nanofluid from a vertical surface with variable transport properties. Int. J. Ambient. Energy. 43, 3170-3188 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Farooq Waqas, U., Shah, H., Kumam, Z., Deebani, W.P.: On unsteady 3D bioconvection flow of viscoelastic nanofluid with radiative heat transfer inside a solar collector plate. Sci Rep. 12, 2952 (2022).

- Mahdy, A.: Natural convection boundary layer flow due to gyrotactic microorganisms about a vertical cone in porous media saturated by a nanofluid. J Brazil Soc Mech Sci Eng. 38, 67-70 (2015).

- Giri, S.S., Das, K., Kundu, P.K.: Stefan blowing effects on MHD bioconvection flow of a nanofluid in the presence of gyrotactic microorganisms with active and passive nanoparticles flux. Eur Phys J Plus. 132, 101 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Waqas, H., Farooq, U., Shah, Z., Kumam, P., Shutaywi, M.: Second-order slip effect on bio-convectional viscoelastic nanofluid flow through a stretching cylinder with swimming microorganisms and melting phenomenon. Sci Rep. 11, 11208 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S., Shah, Q., Sohail, A.: Dynamics with Cattaneo–Christov heat and mass flux theory of bioconvection Oldroyd-B nanofluid. Adv Mech Eng. 12(7), 16–20 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S., Humphries, U.W., Kumam, W., Kumam, P., Muhammad, T.: Bioconvection Casson nanoliquid film sprayed on a stretching cylinder in the portfolio of homogeneous-heterogeneous chemical reactions. ZAMM Angew Math Mech. 101(102), (2022) e202000212. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S., Humphries, U.W., Kumam, W., Kumam, P., Muhammad, T.: Dynamic pathways for the bioconvection in thermally activated rotating system. Biomass Conver Bioref. 14 (7), 8605-8623 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S., Shah, Z., Islam, S., Khan, I., Alkanhal, T.A., Tlili, I.: Entropy generation in MHD mixed convection non-Newtonian second-grade nanoliquid thin film flow through a porous medium with chemical reaction and stratification. Entropy. 21(2), 139 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zuhra, S., Khan, N.S., Islam, S.: Magnetohydrodynamic second grade nanofluid flow containing nanoparticles and gyrotactic microorganisms. Comp Appl Math. 37, 6332–58 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Palwasha, Z., Islam, S., Khan, N.S., Hayat, H.: Non-Newtonian nanoliquids thin film flow through a porous medium with magnetotactic microorganisms. Appl Nanosci. 8, 1523–44 (2018).

- Sajid, M., Iqbal, S.A., Naveed, M., Abbas, Z.: Effect of homogeneousheterogeneous reactions and magnetohydrodynamics on Fe3O4 nanofluid for the Blasius flow with thermal radiations. J Mol Liq. 233, 115–21 (2017).

- Sravanthi, C.S., Mabood, F., Nabi, S.G., Shehzad, S.A.: Heterogeneous and homogeneous reactive flow of magnetite-water nanofluid over a magnetized moving plate. Propulsion Power Res. 11(2), 265–75 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, F., Gowda, R.J.P., Kumar, R.N., Khan, M.I.: Dynamics of thermosolutal Marangoni convection and nanoparticle aggregation effects on Oldroyd-B nanofluid past a porous boundary with homogeneous-heterogeneous catalytic reactions. J Indian Chem Soc. 99(6), 100458 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Mabood, F., Nayak, M.K., Chamkha, A.J.: Heat transfer on the cross flow of micropolar fluids over a thin needle moving in a parallel stream influenced by binary chemical reaction and Arrhenius activation energy. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 134(9), 427 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M., Shaheen, N., Kadry, S., Ratha, Y., Nam, Y.: Thermally stratified darcy forchheimer flow on a moving thin needle with homogeneous heterogeneous reactions and non-uniform heat source/sink. Appl. Sci. 10(2), 432 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Makinde, O.D., Animasaun, I.L.: Thermophoresis and Brownian motion effects on MHD bioconvection of nanofluid with nonlinear thermal radiation and quartic chemical reaction past an upper horizontal surface of a paraboloid of revolution. J. Mol. Liq. 221, 733–743 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I., Waqas, M., Hayat, T., Alsaedi, A.: A comparative study of Casson fluid with homogeneous-heterogeneous reactions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 498, 85–90 (2017).

- Hamid, A.: Terrific effects of Ohmic-viscous dissipation on Casson nanofluid flow over a vertical thin needle: Buoyancy assisting and opposing flow. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9(5), 11220–11230 (2020).

- Dawar, A., Acharya, N.: Unsteady mixed convective radiative nanofluid flow in the stagnation point region of a revolving sphere considering the influence of nanoparticles diameter and nanolayer. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 99(10), 100716 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N., Mabood, F., Badruddin, I.A.: Thermal performance of unsteady mixed convective Ag/MgO nanohybrid flow near the stagnation point domain of a spinning sphere. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 134, 106019 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N., Mabood, F., Shahzad, S.A., Badruddin, I.A.: Hydrothermal variations of radiative nanofluid flow by the influence of nanoparticles diameter and nanolayer. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 130, 105781 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.: Spectral simulation to investigate the effects of nanoparticle diameter and nanolayer on the ferrofluid flow over a slippery rotating disk in the presence of low oscillating magnetic field. Heat Transf. 50(6), 5951–5981 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.: Framing the impacts of highly oscillating magnetic field on the ferrofluid flow over a spinning disk considering nanoparticle diameter and solid–liquid interfacial layer. J. Heat Transf. 142(10), 102503 (2020).

- Khan, N.S., Zuhra, S., Shah, Q.: Entropy generation in two phase model for simulating flow and heat transfer of carbon nanotubes between rotating stretchable disks with cubic autocatalysis chemical reaction. Appl Nanosci. 9, 1797–822 (2019).

- Dawar, A., Shah, Z., Tassaddiq, A., Kumam, P., Islam, S., Khan, W.: A convective flow of Williamson nanofluid through cone and wedge with non-isothermal and non-isosolutal conditions: A revised buongiorno model. Case Stud Therm Eng. 24, 100869 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Cao, W., Lare, A.I., Yook, S.J., Ji, X.: Simulation of the dynamics of colloidal mixture of water with various nanoparticles at different levels of partial slip. Ternary-hybrid nanofluid. Int Commun Heat Mass Transfer. 135, 106069 (2022).

- Alrabaiah, H., Bilal, M., Khan, M.A., Muhammad, T., Legas, E.Y.: Parametric estimation of gyrotactic microorganism hybrid nanofluid flow between the conical gap of spinning disk-cone apparatus. Sci Rep. 12, 59 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nazir, U., Sohail, M., Selim, M.M., Alrabaiah, H., Kumam, P.: Finite element simulations of hybrid nano-Carreau Yasuda fluid with hall and ion slip forces over rotating heated porous cone. Sci Rep. 11, 19604 (2021).

- Shahid, N., Rana, M., Siddique, I.: Exact solution formotion of an Oldroyd-B fluid over an infinite flat plate that applies an oscillating shear stress to the fluid. Bound Value Prob. 10, 48 (2012).

- Oke, A.S.: Combined effects of Coriolis force and nanoparticle properties on the dynamics of gold-water nanofluid across nonuniform surface. ZAMM Angew Math Mech. e202100113 (2022) . [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Yang, W., Liu, Z.: A PANS method based on rotation-corrected energy spectrum for efficient simulation of rotating flow. Front Energ Res. 10, 894258 (2022).

- Ali, B., Shafiq, A., Siddique, I., Al-Madallal, Q., Jarad, F.: Significance of suction/ injection, gravity modulation, thermal radiation, and magnetohydrodynamic on dynamics of micropolar fluid subject to an inclined sheet via finite element approach. Case Stud Therm Eng. 28, 101537 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lei, T., Siddique, I., Ashraf, M.K., Hussain, S., Abdal, S., Ali, B.: Computational analysis of rotating flow of hybrid nanofluid over a stretching surface. Proceed Inst Mechl Eng E: J Process Mech Eng. 236(6), 095440892211000 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Habib, D., Salamat, N., Abdal, S., Siddique, I., Salimi, M., Ahmadian, A.: On time dependent MHD nanofluid dynamics due to enlarging sheet with bioconvection and two thermal boundary conditions. Microfluid Nanofluid. 26, 11 (2022).

- Hussain, F., Nazeer, M., Ghafoor, I., Saleem, A., Waris, B., Siddique, I.: Perturbation solution of Couette flow of casson nanofluid with composite porous medium inside a vertical channel. Nano Sci Technol Int J. 13(4), 23–44 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Siddique, I., Zulqarnain, R.M., Nadeem, M., Jarad, F.: Numerical simulation of MHD Couette flow of a Fuzzy nanofluid through an inclined channel with thermal radiation effect. Comput Intell Neurosci. 6608684, 1–16 (2021).

- Abdal, S., Siddique, I., Saif Ud Din, I., Ahmadian, A., Hussain, S., Salimi, M.: Significance of magnetohydrodynamic Williamson Sutterby nanofluid due to a rotating cone with bioconvection and anisotropic slip. ZAMM Angew Math Mech. e202100503 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, K., Siddique, I., Ali, R., Jarad, F.: Impact of ramped concentration and temperature on MHD Casson nanofluid flow through a vertical channel. J. Nanomater. 3743876, 1–17 (2021).

- Iqbal, S., Siddique, I., Siddiqui, A.M.: OHAM and FEM solutions of concentric n-layer flows of incompressible third-grade fluids in a horizontal cylindrical pipe. J. Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 41, 204 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Q., Obideyi, B.D., Shah, N.A., Animasaun, I.L., Mahrous, Y.M., Chung, J.D.: Significance of haphazard motion and thermal migration of alumina and copper nanoparticles across the dynamics of water and ethylene glycol on a convectively heated surface. Case Stud Therm Eng. 26, 101050 (2021).

- Oke, A.S., Animasaun, I.L., Mutuku, W.N., Kimathi, M., Shah, N.A, Saleem, S.: Significance of Coriolis force, volume fraction, and heat source/sink on the dynamics of water conveying 47 nm alumina nanoparticles over a uniform surface. Chin J Phys. 71, 716–27 (2021).

- Khan, N.S., Shah, Q., Bhaumik, A., Kumam, P., Thounthong, P., Amiri, I.: Entropy generation in bioconvection nanofluid flow between two stretchable rotating disks. Sci Rep. 10, 4448 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.H., Khan, N.S., Rano, S.A., Humphries, U.W., Kumam, P.: Computational investigations of Arrhenius activation energy and entropy generation in a viscoelastic nanofluid flow thin film sprayed on a stretching cylinder. J Adv Res Fluid Mech Therm Sci. 86(1), 27–51 (2021).

- Ramzan, M., Khan, N.S., Kumam, P.: Mechanical analysis of non-Newtonian nanofluid past a thin needle with dipole effect and entropic characteristics. Sci Rep. 11(1), 19378 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S., Humphries, U.W., Kumam, W., Kumam, P., Muhammad, T.: Bioconvection Casson nanoliquid film sprayed on a stretching cylinder in the portfolio of homogeneous-heterogeneous chemical reactions. Z Angew Math Mech. 8, e2020000222 (2022). [CrossRef]

- L. Ali, Z. Omar, I. Khan, J. Raza, M. Bakouri, I. Tlili.: Stability analysis of Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Casson type nanofluid over an exponential sheet: investigation of critical points. Symmetry. 11, 412 (2019).

- J. Kavita, S. Kalpna, P. Choudhary, P. Soni, A. Rifaqat, M. Ganesh. Significance of Darcy–Forchheimer Casson fluid flow past a non-permeable curved stretching sheet with the impacts of heat and mass transfer. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering. 61, 104907 (2024).

- N.M. Hafez, E. N. Thabet, Zeeshan Khan, A.M. Abd-Alla, S.H. Elhag.: Electroosmosis-modulated Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Casson nanofluid over stretching sheets in the presence of Newtonian heating. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering. 53, 103806 ( 2024). [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S., Patra, A., Misra, A., Nayak, M.K.: Assisting/opposing/forced convection flow on entropy-optimized MHD nanofluids with variable viscosity. Interfacial layer and shape effects. Heat Transf. 51(1), 578–603 (2021).

- Himanshu, U., Priya, B., Kumar, P.A., Makinde, O.D.: Heat transfer assessment for Au-blood nanofluid flow in Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium using induced magnetic field and Cattaneo-Christov model. Numer Heat Transf. Part B. Fundamentals. 84(4), 415–31 (2023).

- Satya Narayana, P.V., Tarakaramu, N., Moliya Akshit, S., Jati P.G.: MHD flow and heat transfer of an Eyring-Powell fluid over a linear stretching sheet with viscous dissipation-A numerical study. Front Heat Mass Transf. 9(1), 1–5 (2017).

- Elgendi, S.G., Abbas, W.,· Ahmed, A.M.: Said,·A. M.: Megahed Eman Fares. Computational Analysis of the Dissipative Casson Fluid Flow Originating from a Slippery Sheet in Porous Media. Journal of Nonlinear Mathematical Physics. 31, 19 (2024).

| Presents results | Presents results | Presents results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.51502 | 1.51501 | 0.0928714 | 0.0928711 | 0.825845 | 0.825840 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66661 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923994 | 0.806926 | 0.806923 |

| 1.89542 | 1.89543 | 0.0916227 | 0.0916225 | 0.779026 | 0.779022 |

| 1.83257 | 1.83255 | 0.0906326 | 0.0906323 | 0.786406 | 0.786401 |

| 1.70039 | 1.70034 | 0.0920388 | 0.0920386 | 0.802712 | 0.802710 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66655 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923998 | 0.806926 | 0.806925 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66658 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923994 | 0.806926 | 0.806922 |

| 1.76956 | 1.76959 | 0.0912866 | 0.0912863 | 0.796401 | 0.796402 |

| 1.85492 | 1.85490 | 0.0903812 | 0.0903807 | 0.787746 | 0.787744 |

| 2.76472 | 2.76471 | 0.0873642 | 0.0873640 | 0.886156 | 0.886153 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66661 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923978 | 0.806926 | 0.806924 |

| 1.21544 | 1.21542 | 0.0941238 | 0.0941237 | 0.766893 | 0.766890 |

| 1.67388 | 1.67385 | 0.0924106 | 0.0924104 | 0.807306 | 0.807302 |

| 1.62478 | 1.62467 | 0.0923341 | 0.0923342 | 0.804575 | 0.804572 |

| 1.56035 | 1.56027 | 0.0922204 | 0.0922201 | 0.800409 | 0.800404 |

| 1.88054 | 1.88053 | 0.0921267 | 0.0921265 | 0.809828 | 0.809824 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66662 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923996 | 0.806926 | 0.806925 |

| 1.46167 | 1.46165 | 0.0926254 | 0.0926253 | 0.801361 | 0.801362 |

| 1.55498 | 1.55497 | 0.0900135 | 0.0900132 | 0.563252 | 0.563251 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66662 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923993 | 0.806926 | 0.806924 |

| 1.90001 | 1.90002 | 0.0952221 | 0.0952220 | 1.397651 | 1.397650 |

| 1.66663 | 1.66662 | 0.0923999 | 0.0923996 | 0.806926 | 0.806924 |

| 1.66566 | 1.66559 | 0.265119 | 0.265105 | 0.806856 | 0.806854 |

| 1.66476 | 1.66472 | 0.4234431 | 0.4234425 | 0.806791 | 0.806792 |

| 1.66665 | 1.66658 | 0.0924475 | 0.0924470 | 0.806928 | 0.806926 |

| 1.66634 | 1.66632 | 0.0919339 | 0.0919331 | 0.806913 | 0.806912 |

| 1.66575 | 1.66573 | 0.0909649 | 0.0909645 | 0.806884 | 0.806882 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).