1. Introduction

The Maldives is a unique archipelago comprising 26 atolls and approximately 1,200 islands. It is primarily known for its extensive coral reefs, which are the seventh largest in the world and has been an international tourist destination since the 1970s. In 1972, Kurumba Maldives, the first resort established by Italian entrepreneurs, opened on the island of Vihamanafushi, a short distance from the capital, Malé. This event marked the beginning of mass tourism in the archipelago. Since 1972, when resorts had a capacity of just 280 beds, the tourism sector has grown significantly. By 1985, there were 55 resorts, and by 2009, this number had increased to 97 resorts with a total capacity of over 20,000 beds (Scheyvens, 2011). As of 2024, the Maldives boasts 179 resorts (1 is currently closed) with a total capacity of approximately 60,000 beds (King, 2024). Tourism has driven the Maldives’ transition from a least-developed country to an upper-middle-income nation within 40 years. Tourism directly contributes 40% to the GDP, with the industry segmented into resorts (25.3%), other accommodation (3.1%), and food and beverage services (0.8%). Tourism revenue constituted 35.4% of total government revenue in 2019 and 42.9% in 2021. (Maldives fifth Tourism Master plan 2023-2027). Tourism has brought considerable prosperity to the Maldives; however, it has also strained natural resources and heightened the country’s vulnerability. The Maldives ranks among the most at-risk nations globally for sea level rise, with over 80% of its islands lying less than one meter above sea level. Projections indicate that sea levels may rise by 0.5 to 1.2 meters, potentially resulting in the loss of approximately 77% of the country’s land area by 2100. This poses a significant threat to the Maldives’ tourism industry, as over 90% of resort infrastructure and 99% of tourist accommodations are located within 100 meters of the shoreline (King, 2024). Few studies have analyzed sustainable practices in protected or fragile areas (Font et al., 2016; Wolf et al., 2024), and little is known about sustainability reporting practices and hospitality companies (Khatter et al., 2019). To address this gap this empirical analysis on Maldives reports aims to contribute to this field of research.

Sustainability reporting in the tourism sector: Literature review

The term sustainability originated in the 17th century in agriculture and botany, later expanding to various disciplines to describe responsible changes in resource use, technology, and institutions to meet human needs now and in the future (Grober, 2007). Sustainability reporting has been extensively explored in the literature, revealing key determinants such as the adoption, extent, and disclosure quality. These aspects are significantly shaped by international frameworks and guidelines, as highlighted by various studies (Hahn and Kuhnen, 2013; Dienes et al., 2016; Traxler et al., 2020). The importance of standardizing reporting practices is underscored by the challenges in providing both quantitative and qualitative information on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) issues. These challenges necessitate shared tools and frameworks to ensure consistency across countries (Siew, 2015). In the tourism sector, the absence of specific standards issued by entities like the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) or the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) has left this industry without comprehensive regulations. However, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) provide some relevant guidelines. For instance, ESRS 1 emphasizes foundational prerequisites for sustainability reporting, such as resource conservation, community engagement, and responsible tourism practices. ESRS 2 focuses on the transparency of sustainability practices, covering eco-friendly initiatives, cultural preservation, and community-driven projects. Moreover, ESRS standards E1 to E5 address environmental issues, including climate change, pollution, water and marine resources, biodiversity, and circular economy practices. Adopting and enforcing sustainability reporting standards hold significant potential for harmonizing reporting practices globally, especially in tourism. Research highlights the growing interest in sustainable tourism practices, examining Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) regulation instruments (Osman et al., 2022), the Triple Bottom Line framework (Stoddard et al., 2012), and managerial approaches in hospitality (Vávrová et al., 2024). Studies have also identified CSR’s direct influence on stakeholders like employees and customers, alongside its impact on business performance, mediated by factors such as customer trust and value (Madanaguli et al., 2021). Environmental concerns dominate the ESG discourse, with research examining pro-environmental behaviors (Ashraf et al., 2023), the environmental impact of hotels (Gomez-Guillen and Tapias-Baquè, 2024), and eco-innovation in hospitality (Sharma et al., 2020). Social dimensions have been explored in terms of labor relations in hospitality CSR reports (Piotr et al., 2024), participatory approaches involving local communities (Goebel et al., 2019), and stakeholder engagement processes (Guix et al., 2018; Iazzi et al., 2020). Reporting aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a growing focus, with studies showing how sustainable hotels can adopt strategic SDG reporting approaches (Prince et al., 2024; Ferrero-Ferrero et al., 2024). Empirical evidence reveals that sustainability reporting in the tourism sector often stems from a desire for legitimation or impression management rather than genuine accountability (Guix et al., 2018; McNally and Maroun, 2018). The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), effective January 2023, marks a significant shift in sustainability reporting requirements. It mandates detailed ESG disclosures for large and publicly listed companies, including those operating internationally, like European-owned luxury resorts in the Maldives. The CSRD incorporates double materiality, requiring companies to report how sustainability issues affect their business and how their operations impact the environment and society. For instance, resorts in the Maldives must address issues such as coral reef health, marine biodiversity, and community resource use. The CSRD aligns with other EU policies, including the European Green Deal, the EU Climate Law, and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). These frameworks promote resource efficiency, biodiversity protection, and climate action. Specific to tourism, the EU supports sustainability through initiatives like ISO 21401 and the EU Ecolabel, fostering environmentally responsible practices. Considering this framework, the Maldives, with their tourism-driven economy rooted in resort management, provide a compelling case study for assessing the current state of sustainable practices in fragile ecosystems.

Sustainability in Maldivian resorts: a focus on stakeholders in fragile ecosystems

The Maldives government has significantly emphasized environmental protection and sustainability, embedding these priorities within its legal framework and national policies. The 2008 constitutional revision underscores this commitment: Article 22 mandates the state to protect the natural environment, biodiversity, and aesthetic appeal of the country for future generations, while Article 23 guarantees citizens the right to a healthy, ecologically balanced environment, tasking the government with safeguarding this right (Grober, 2007). Following notable environmental degradation in 2015, the Maldives introduced the Green Tax, an environmental levy on tourists to fund conservation and waste management initiatives across the islands (United Nations Tourism Organization, n.d.). Recognizing the substantial waste generated by resorts - 2.5 to 7.5 kg per guest daily compared to 0.8 -1.0 kg per resident in Malé; the Green Tax reflects a proactive approach to balancing tourism with environmental sustainability (Republic of Maldives, Environmental Protection and Preservation Act, 1993/2014). Alongside these efforts, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has gained traction, particularly within large companies and the tourism sector, with engagement driven by consumer expectations, regulatory requirements, and international standards (Republic of Maldives, Climate Emergency Act, 2021). The Maldivian legal system has developed robust environmental legislation, including the Environmental Protection and Preservation Act (1993) (Republic of Maldives, Tourism Act, 1999), the Climate Emergency Act (2021) (United Nations, Paris Agreement, 2015), and the Maldives Tourism Act (1999). The Maldives also actively participates in global climate agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, to address its climate vulnerabilities, especially sea level rise (Techera & Cannell-Lunn, 2019). The Maldives Tourism Act and the Tourism Climate Action Plan (European Union, 2016) set stringent eco-friendly guidelines for the tourism industry, aiming to protect sensitive ecosystems like coral reefs through sustainable practices, eco-tourism, and efficient resource management (Techera & Cannell-Lunn, 2019). Indeed, some Maldivian resorts have already emerged as key players, implementing strategies to reduce environmental impact while fostering biodiversity conservation and strengthening community engagement. Nevertheless, while these initiatives reflect the Maldives’ dedication to aligning economic growth with environmental sustainability, enforcement remains challenging due to limited resources and the country’s vast, dispersed geography. Several resorts in the Maldives actively contribute to marine conservation, aligning with UN Goal 14. For example Soneva Fushi: Launched a large-scale coral nursery in 2021 to propagate 50,000 coral fragments annually, Four Seasons Landaa Giraavaru: Collaborates with the Manta Trust on manta ray conservation and offers educational programs like "Manta-on-Call"; Olive Ridley Project (ORP): Partners with resorts like Coco Palm Dhuni Kolhu, The Ritz-Carlton Maldives, and One&Only Reethi Rah to rehabilitate turtles and protect habitats; Six Senses Laamu: Focuses on coral reef monitoring, manta ray protection, guest education, and operational sustainability; Diamonds Thudufushi: Hosts a research lab with an University, integrating academic research with conservation.

Benchmarking Sustainability in Light of Resort Ratings in the Maldives

While sustainability reporting is not yet universally mandatory across all sectors in the Maldives, there is a clear trend towards increased regulation for businesses, particularly in tourism, to adopt and report on sustainable practices. This shift is reflected in various reports and frameworks published with different designations. From a classification standpoint based on the services offered, there is no precise regulation for resorts. In the absence of official standards, resorts often look to the European five-star classification system, with some variations, such as the option to add "plus" to the star rating. Therefore, one resort might be rated five stars while another is rated five stars plus. Some even refer to themselves as six-star resorts, similar to the luxury classification in the United Arab Emirates, where ratings can go as high as seven stars.

Overview

This study addresses a key gap in the literature: the lack of comparative analysis on how Maldivian resorts implement and communicate sustainability practices. It aims to provide an overview of these practices, particularly in light of new EU regulations under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) effective September 2024. Additionally, it investigates whether resorts of different classifications vary in their communication and actions on sustainability, exploring a potential link between star ratings and sustainability efforts. Since star classifications focus on services and infrastructure rather than sustainability, this analysis will assess how well Maldivian resorts align with international standards and prepare for regulatory changes. All relevant documents publicly available from Maldivian resorts were analyzed to achieve these aims. Specifically, study 1 focused on assessing whether the volume of information disclosed in these documents differed across resort categories. Moreover, study 2 included a thematic analysis of the text within these documents to identify key themes and determine if any differences emerged among resort classes. In conclusion, study 3 followed a similar approach but analyzed the visual communication strategies adopted by the considered resorts.

To do so, we adopted a mixed-method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative analyses to provide a comprehensive view of sustainability in Maldivian resorts. The present research offers actionable insights for policymakers, tourism industries stakeholders, and researchers by analyzing sustainability narratives and practices across resort categories. This integrated analysis enhances the understanding of sustainable tourism in island nations and provides a template for evaluating similar contexts globally.

2. Materials and Methods

Study 2 - Thematic text analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted on all textual parts present in the corpus of data described in Study 1. To understand whether there were any differences in the themes covered, the analyses were conducted by considering three subsamples of text separately, dividing the reports based on the level of resorts (Category 1, 2, and 3). The total body of data from the transcripts was distributed as follows: Category 3 total words: 63.779; Category 2 total words: 181.808; Category 1 total words: 21.586.Thematic analysis (Brown & Clarke, 2012) serves as a cornerstone in qualitative research, offering researchers a method to identify, analyze, interpret, and elucidate patterns or themes from their data. Its application transcends disciplines, contributing to its popularity and widespread use. The traditional Six-Phase Approach (see Brown & Clarke, 2012; Clarke et al., 2015) is widely recognized for its sequential process that guides researchers through distinct phases. The thematic analysis begins with data familiarization through extensive reading and note-taking of transcripts to grasp the content and identify initial insights. This is followed by systematically coding the data using specific software. These codes are then grouped into overarching themes that reflect broader patterns relevant to the research question. Each theme is reviewed to ensure it captures all relevant data and accurately represents the dataset’s narrative. The themes are further refined and clearly defined, with subthemes identified to emphasize distinct aspects. Finally, the report is produced by selecting vivid examples from the data to illustrate each theme, linking them back to the research question through direct quotations. Nevertheless, thematic analysis poses several challenges, such as subjectivity in identifying themes (Morgan, 2022), leading to varying interpretations (Berger, 2015). Moreover, thematic analysis is often resource-demanding and time-consuming, particularly when analyzing large datasets (Guest et al., 2013). Replicability and generalizability are also significant concerns (Morgan, 2022). Some authors (Chew et al., 2023; De Paoli, 2024) have recently proposed using a Large Language Model (LLM) for thematic analysis. Indeed, recent literature suggest that LLM models may perform better than human coding in deductive analysis (see De Paoli, 2024; Mathis et al., 2024). Based on this evidence, in the present work, LLM-based analysis tools were chosen to extract the themes found in the texts in the sustainability reports published by all the resorts in the Maldives. More in detail, the adopted LLM was designed to assist in identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within qualitative data, aligning with traditional thematic analysis frameworks (e.g., Braun & Clarke, 2012), though the computational efficiency and pattern recognition capabilities enhance the speed and scope of analysis. The following steps describe how the LLM conducted the thematic analysis. The LLM model first processed the text extracted from the considered sustainability reports through natural language processing (NLP) algorithms. The text was tokenized into smaller units and removed any unnecessary formatting. Using its pre-trained architecture, the algorithm identified patterns in the data by recognizing word frequencies, co-occurrences, and semantic relationships. The model then highlighted segments of text that recur across the text as initial codes automatically assigned to text patterns detected within the data. Codes reflect explicit content (e.g., frequently mentioned concepts) and relationships between concepts. After generating initial codes, the algorithm groups related codes into candidate themes. Themes are defined as broader patterns that capture the essence of multiple codes. The algorithm used clustering algorithms to detect higher-order relationships between codes, forming themes that provide a deeper understanding of the data. The model evaluates the coherence and distinctiveness of these themes, ensuring that they are internally consistent and mutually exclusive. Therefore, the algorithm refined the identified themes by reviewing them across the entire dataset to ensure accuracy. Redundant or overlapping themes were merged, and themes lacking sufficient supporting evidence were discarded. Finally, once the themes were finalized, detailed definitions for each theme and supporting quotes were generated.

Study 3 - Images content analysis

The corpus of images was extracted from the same reports described in Study 1. The archive contains a total of 746 images. The mean resolution of the images is approximately 551.290 pixels, and the average file size is about 360.26 KB. Similarly, to what was described in Study 1, we used a pre-trained model to identify, analyze, and report themes from images. This software integrates specific computer vision techniques with qualitative coding to extract meaningful themes from visual data. Initially, images are preprocessed using contrast enhancement, denoising, and segmentation techniques to improve clarity and isolate key features. Canny edge detection is adopted to identify object boundaries and color segmentation for distinguishing thematic color patterns. For object detection, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) (Redmon, 2016) algorithm is employed to detect and classify common objects within the images, and Faster R-CNN (see Zou, 2019) for more detailed recognition of complex visual elements. Human faces and expressions are analyzed using facial recognition algorithms, while Optical Character Recognition (OCR) was employed to extract embedded textual data. These visual and textual elements are automatically coded into text descriptions, allowing for thematic interpretation based on spatial relationships, emotional tone, and recurring patterns. The software then uses the k-means clustering to group images based on visual similarities. At the same time, pattern recognition methods are adopted to identify overarching themes across the dataset, providing objective image features and their contextual interpretations. To identify themes described in the published reports and subsequently compare them with international reference standards for sustainability reports, a content thematic analysis was conducted using Qualitative Analyzer Pro, an LLM based software that integrates the capabilities of CLIP, an artificial intelligence model developed by OpenAI (2024) that can understand and interpret the content of images by linking images and text, allowing it to identify objects, concepts, and relationships within images. As for Study 1, the analyses were conducted by considering the images of the resort categories separately. The total body of images was distributed as follows: Category 1 N=56; Category 2 N=370; Category 3 N=320.

3. Results

Study 2 - Thematic text analysis

To identify themes described in the published reports and subsequently compare them with international reference standards for sustainability reports, a thematic analysis was conducted.

Themes emerged for six-star resort transcripts

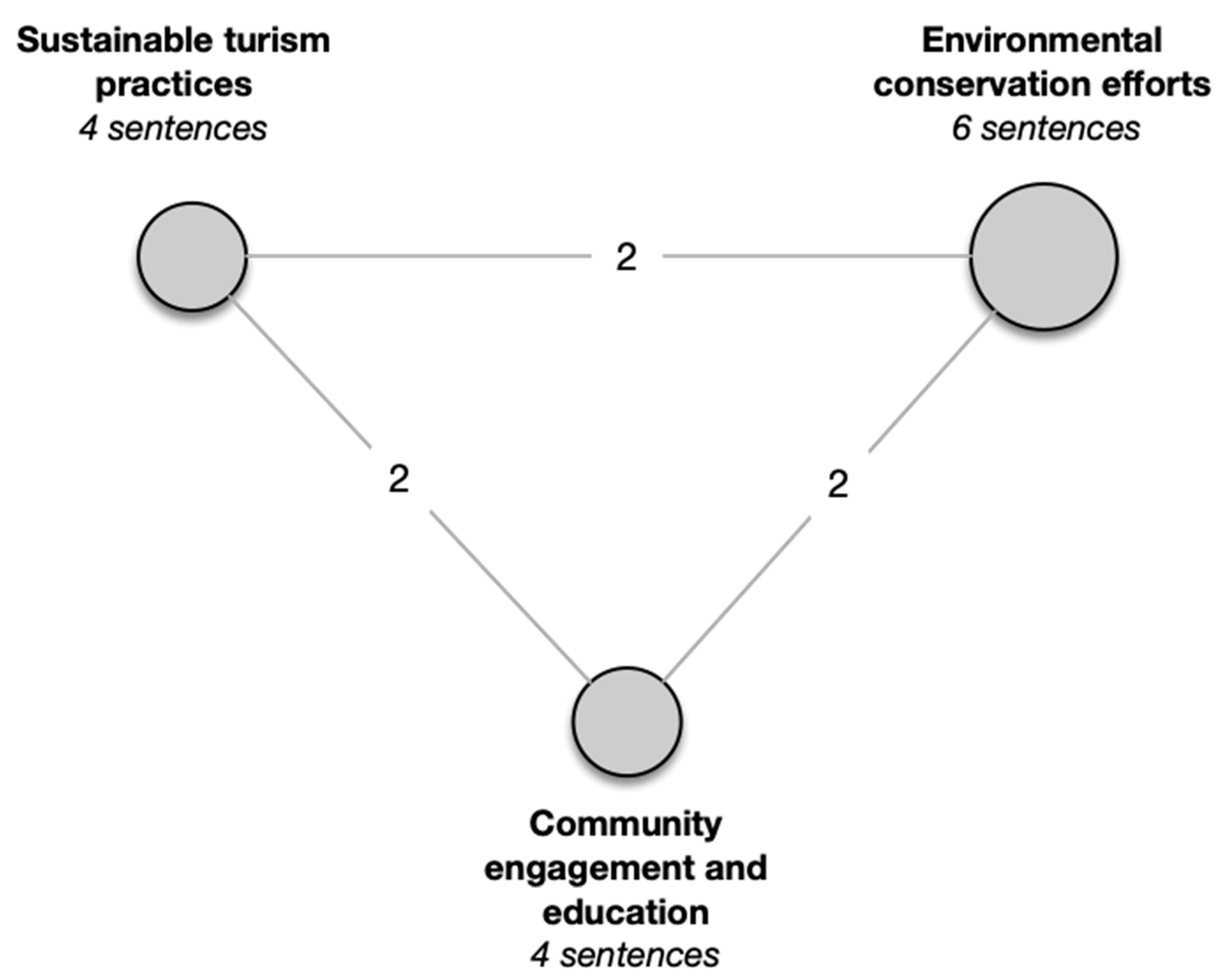

When considering the reports published by Category 1 resorts, the following 3 themes emerged (see also

Table 4 and

Figure 1):

Environmental Conservation Efforts. Initiatives and practices aimed at preserving natural ecosystems and biodiversity, often through sustainable practices and active restoration projects.

Community Engagement and Education. Activities and programs aimed at involving local communities in conservation efforts and educating them about environmental and cultural sustainability.

Sustainable Tourism Practices. Tourism practices that prioritize environmental sustainability include reducing waste, conserving water and energy, and promoting local culture.

Themes emerged for five-star resort transcripts

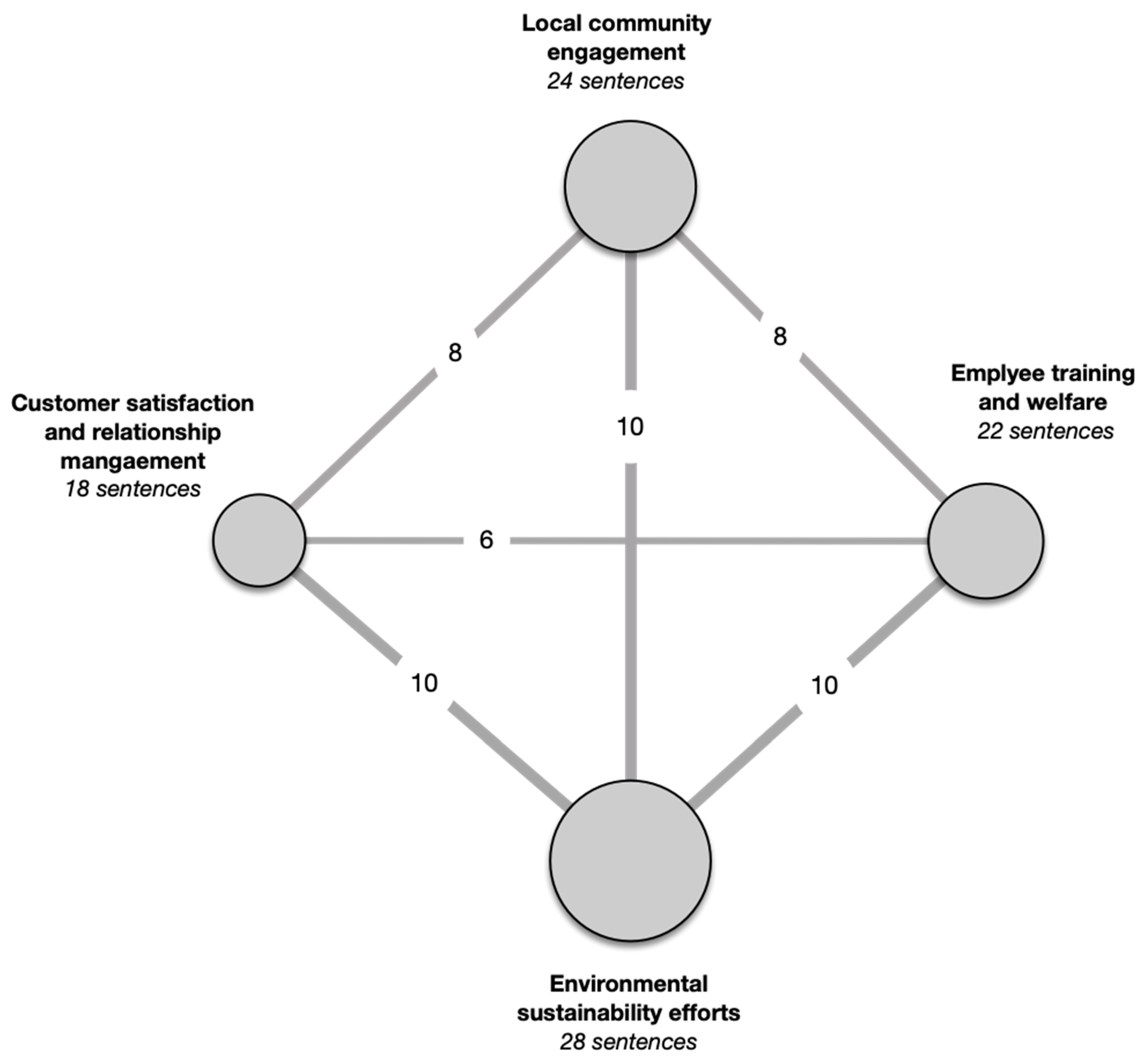

When considering the reports published by Category 2 resorts, the following 4 themes emerged (see also

Table 5 and

Figure 2):

Environmental Sustainability Efforts. This theme encompasses all initiatives and policies aimed at reducing environmental impact, promoting sustainable practices, and conserving natural resources.

Local Community Engagement. This theme involves efforts made by the resorts to engage with and support the local community through employment, educational initiatives, and other community-centric activities.

Employee Training and Welfare. This theme covers the training programs, safety measures, and welfare initiatives designed to ensure employees are skilled, safe, and motivated.

Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Management. This theme includes practices and strategies aimed at ensuring customer satisfaction and managing relationships effectively.

Themes emerged for Category 3 resort transcripts

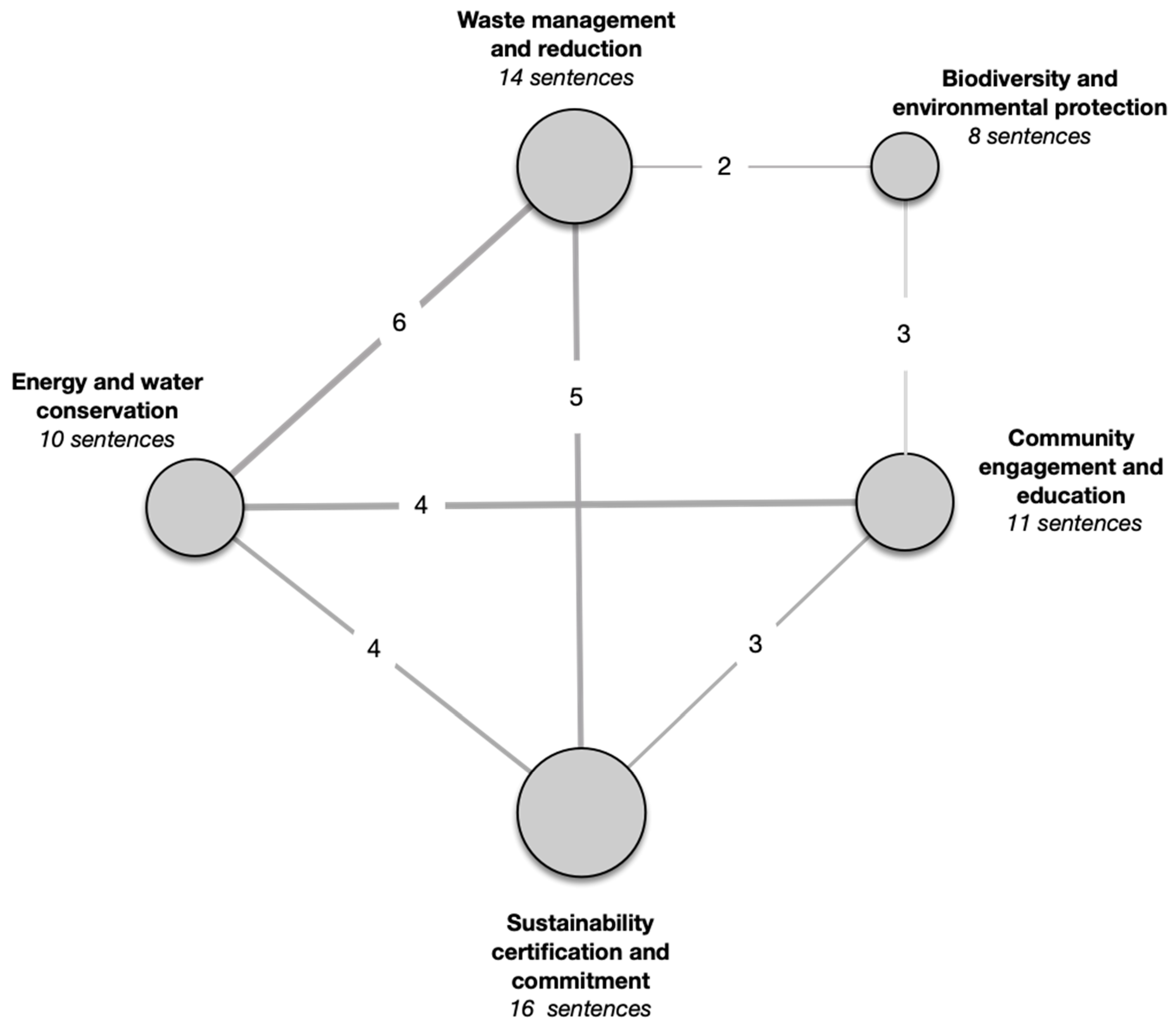

When considering the reports published by Category 3 resorts, the following 5 themes emerged (see also

Table 6 and

Figure 3):

Sustainability Certification and Commitment. This theme encompasses the organization’s commitment to achieving and maintaining sustainability certifications, such as Green Globe Certification, and continuous efforts to improve sustainability practices. The focus is on demonstrating leadership in environmental responsibility and ensuring year-on-year improvements.

Waste Management and Reduction. This theme focuses on the strategies and objectives related to waste management, including reducing non-recyclable waste, increasing recycling rates, and minimizing the environmental impact through responsible waste disposal practices.

Energy and Water Conservation. This theme includes initiatives and objectives aimed at conserving energy and water, optimizing efficiency, and utilizing renewable energy sources to reduce the overall environmental footprint.

Community Engagement and Education. This theme highlights the organization’s efforts to engage with local communities, provide education on sustainability practices, and support local development through various initiatives and partnerships.

Biodiversity and Environmental Protection. This theme involves the protection and conservation of biodiversity, ecosystems, and landscapes. It includes activities such as coral reef conservation, reducing pollution, and maintaining the natural environment.

Study 3 - Images content analysis

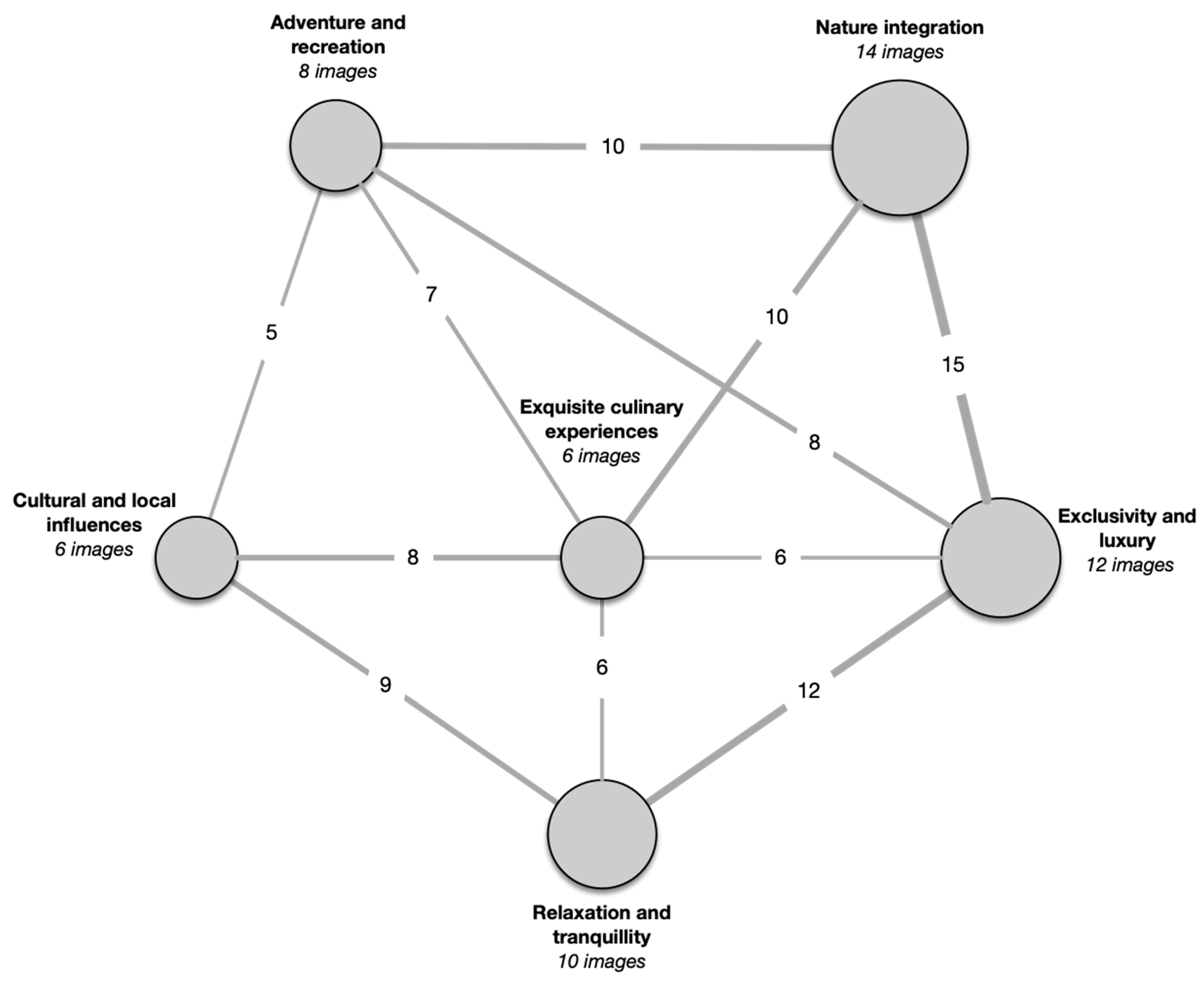

Themes emerged for six-star resort images

Upon reviewing the reports from Category 1, six key themes were identified (refer to

Figure 4):

Nature Integration (14 images): Many images focus on scenes of pristine beaches, overwater bungalows, and villas nestled amidst lush greenery.

Exclusivity and Luxury (12 images): These images showcase private villas, luxurious indoor spaces, elegantly furnished rooms, and private pools.

Relaxation and Tranquility (10 images): This theme revolves around images that depict serene and peaceful environments such as calm swimming pools, beachside lounging areas, hammocks, and spa-like settings.

Exquisite Culinary Experiences (6 images): images in this cluster focus on the culinary experiences, emphasizing the high-quality, artistic presentation of food and highlight fine dining as a crucial part of the guest experience.

Adventure and Recreation (8 images): this group of images showcases scenes of water sports such as snorkeling, boating, and jet skiing.

Cultural and Local Influences (6 images): This cluster incorporates elements of Maldivian culture, including traditional architecture, locally inspired decor, and design motifs.

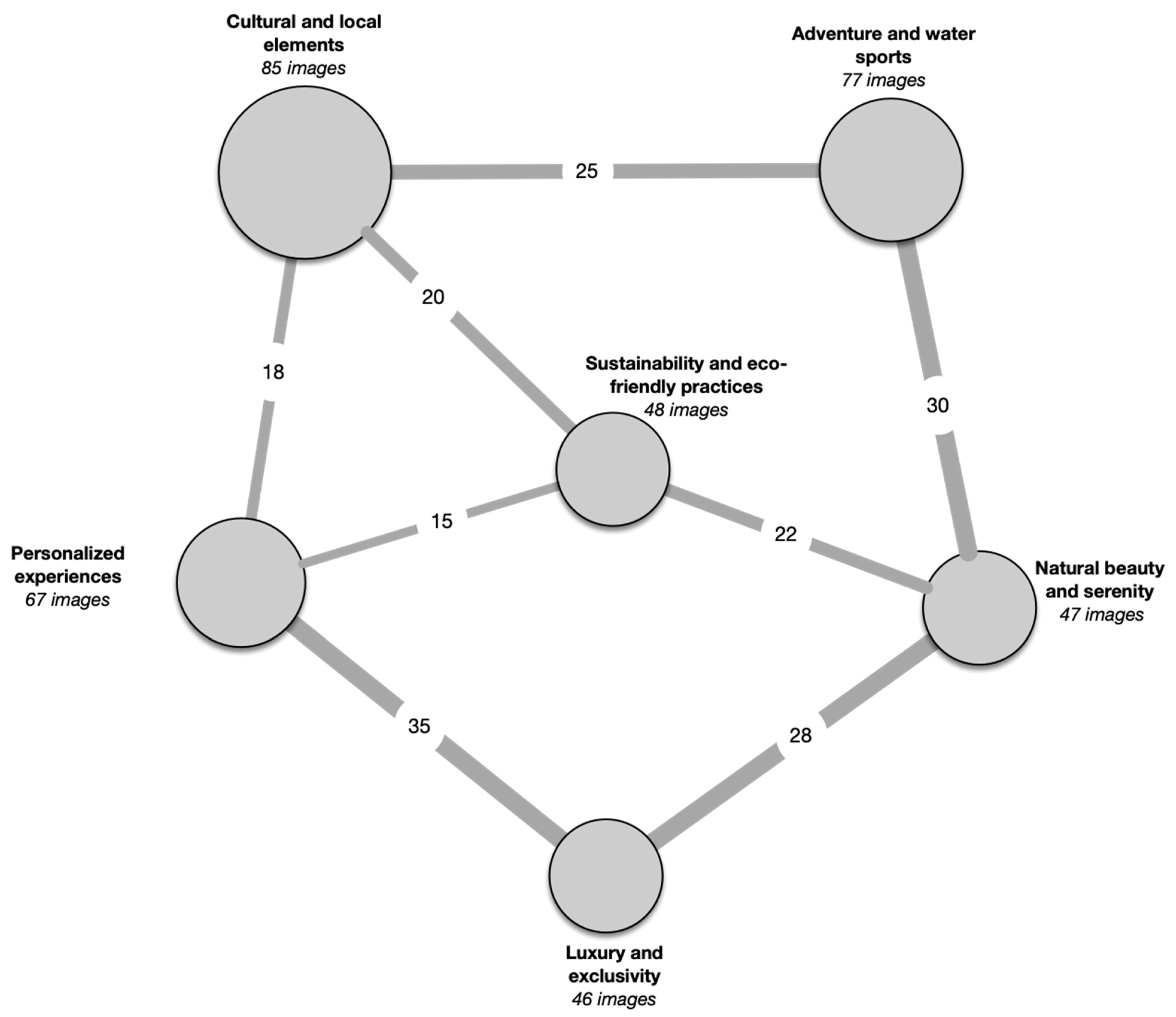

Themes emerged for Category 2 resort images

When considering the reports published by Category 2 resorts, the following six themes emerged (see also

Figure 5):

Adventure and Water Sports (77 images): Images in this cluster depict a wide range of water-based activities such as snorkeling, scuba diving, jet skiing, parasailing, and boat excursions.

Natural Beauty and Serenity (47 images): This theme focuses on visually representing the Maldives’ natural landscapes. Images often feature pristine beaches, crystal-clear waters, coral reefs, sunsets, palm trees, and coral reefs.

Luxury and Exclusivity (46 images). Images in this group showcase high-end amenities such as private overwater villas, luxurious accommodations, high-end interiors, and elegant settings.

Cultural and Local Elements (85 images). Images in this cluster depict traditional Maldivian activities, food, crafts, performances, local artisans, and local architecture.

Personalized Experiences and Leisure (67 images). Images highlight services such as private dinners on the beach, personalized spa treatments, romantic getaways, and custom excursions.

Sustainability and Eco-Friendly Practices (48 images). This theme comprises images showing solar panels, eco-friendly architecture, nature conservation, recycling initiatives, and sustainable materials.

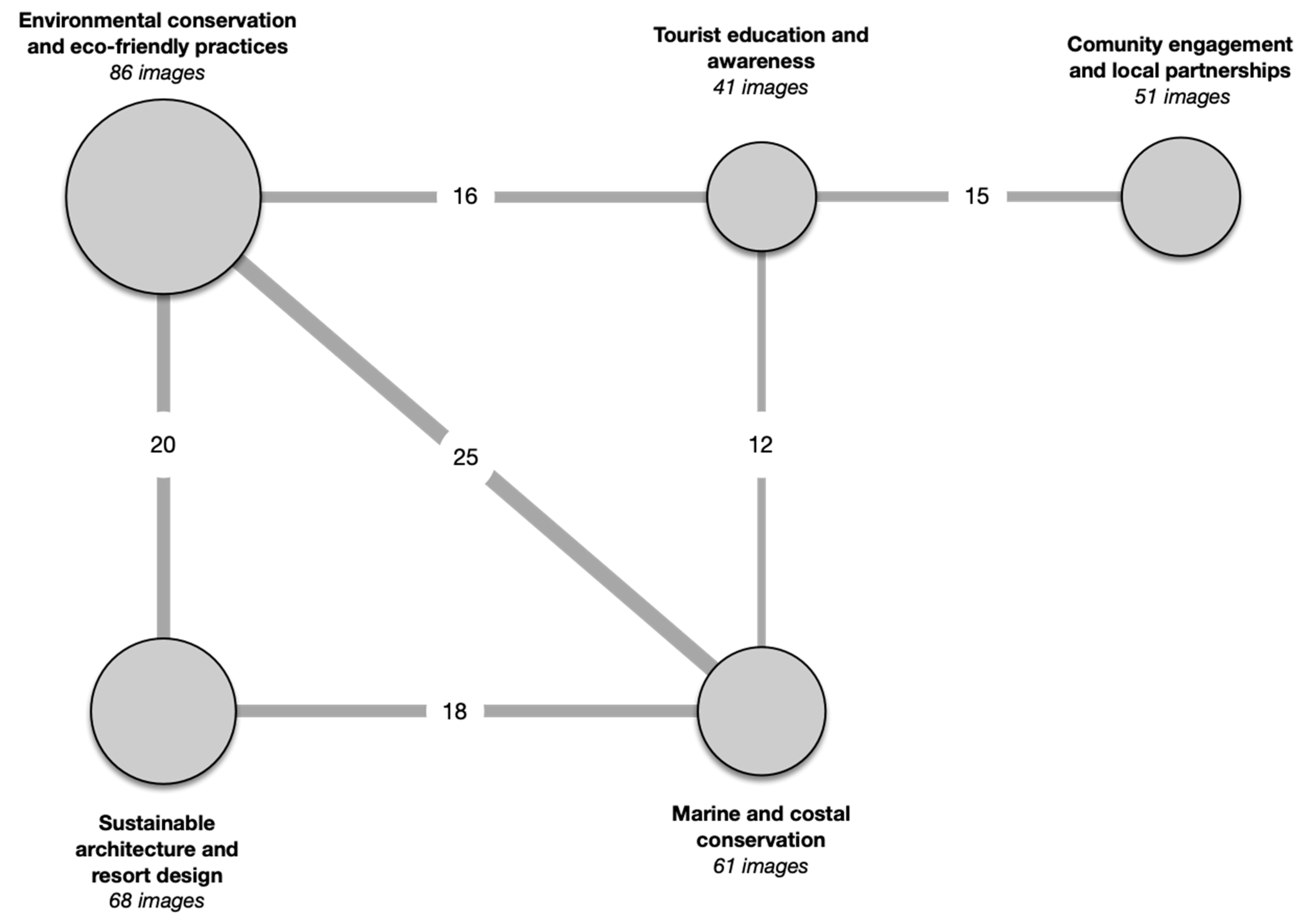

Themes emerged for Category 3 resort images

When considering the reports published by Category 3 stars resorts, the following 5 themes emerged (see also

Figure 6):

Environmental Conservation and Eco-Friendly Practices (86 images): Images in this theme depict sustainability practices such as waste management, renewable energy use, and water conservation.

Sustainable Architecture and Resort Design (68 images): images in this theme pertain to sustainable buildings, using natural materials and eco-friendly building techniques.

Marine and Coastal Conservation (61 images): images in this cluster are related to marine conservation, showing the marine ecosystem of the Maldives, initiatives for maintaining coral reefs, preserving beaches, and protecting marine species.

Community Engagement and Local Partnerships (51 images) This group of images includes local staff, partnering with local suppliers, or activities for supporting community education.

Tourist Education and Awareness (41 images): this cluster includes tourist education activities and tourists’ involvement in sustainability initiatives.

4. Discussion

Study 2 - Thematic text analysis

Overall, the thematic analysis suggests that the analyzed reports pay some attention to sustainability-related issues. However, differences in communication strategies emerge among the different levels of resorts.

Considering the results of the reports published by the Category 3 resorts, most sentences focus on sustainability certification and commitment, waste management and reduction, and energy and water conservation. These results suggest that the main issues addressed in the reports are related to the description of adopted environmental policies and sustainable practices. Accordingly, these clusters are related to local community engagement, highlighting an active involvement of local people in these activities as well. A similar pattern of results emerged also for 5-star resorts. The largest number of sentences is devoted to practices adopted concerning sustainability, showing the involvement of local communities to which staff training activities are also added. One unique aspect that emerges when considering Category 2 resort reports is represented by customer satisfaction and relationship management, suggesting how 5-star resorts devote particular energies to caring for customers and maintaining relationships with them, compared to other segments of resorts. The four themes seem particularly balanced, indicating a similar focus by the resorts on these areas.

Finally, Category 1 resorts are committed to environmental conservation through various sustainable practices and restoration projects. In addition to their environmental initiatives, the resorts engage with local communities, involving them in conservation projects and providing education on sustainability. Sustainable tourism practices are also a central focus, with the resorts emphasizing environmentally friendly approaches that not only protect the environment but also promote and celebrate local culture.

Study 3 - Images content analysis

The thematic analysis of the images confirms the differences that emerged in Study 1, suggesting a difference in communication strategy between Category 3 compared to Category 2 and 1. Specifically, the sustainability reports of Category 3 resorts in the Maldives present various key themes focusing on environmental and community efforts. The analysis reveals that most images highlight environmental conservation practices, such as waste management, energy efficiency, and marine conservation, indicating that these resorts prioritize preserving natural resources. Specifically, 86 images emphasize eco-friendly practices, illustrating the resorts’ commitment to protecting the environment. Sustainable architecture and design are also prominent, with 68 images reflecting environmentally conscious materials and designs that blend with natural surroundings. With 61 images, marine conservation underscores the importance of preserving marine life, vital for tourism activities like diving and snorkeling.

Moreover, these three thematic areas appear strongly interconnected (see

Figure 4). A fourth thematic area ties in with the previous ones, that of Tourist education, suggesting that the activities proposed by Category 3 resorts focus on environmental conservation and sustainable practices. Finally, although it emerged that resorts are making efforts to involve the local community, this thematic area appears distant from the others and not interconnected, resulting in a peripheral theme to the other thematic clusters.

Overall, the distribution of themes suggests that environmental sustainability and eco-friendly architecture are the core focus areas. At the same time, there is room for growth in community engagement and tourist education to further enhance the resorts’ comprehensive sustainability strategies.

Communication strategy differences emerge when considering reports from Category 2 and Category 1 resorts. In particular, the theme of luxury and exclusive experiences emerged. Five-star resort analyses revealed that the themes labeled as “cultural and local elements” and “adventure and water sports” emerged as the most prominent, with 85 images and 7 images, respectively, indicating a strong emphasis on showcasing local traditions and experiences offered as services to tourists. This aspect is also strongly related to the third cluster that emerged, e.g., “personalized experiences”, which highlights the resorts’ focus on customized guest services and exclusive and tailored experiences. The Category 2 reports also emphasize aspects related to “natural Beauty and Serenity” (47 images) and “Luxury and Exclusivity” (46 images), indicating that both the scenic environment and high-end comfort are essential to the resorts’ appeal.

Moreover, analysis suggests that these themes are all interconnected revolving around sustainability. The node labeled “Sustainability and eco-friendly practices” takes on the role of a pivot concerning the distribution of the other thematic clusters. Nevertheless, sustainability seems more of a growing area, with only 48 images reflecting eco-friendly practices. This suggests that sustainability is still a developing issue and not yet the priority of 5-star resorts, placing sustainability and ecological practices on the same level as luxury and exclusive experiences.

Finally, the analysis results for Category 1 resorts seem to confirm this trend, according to which as the prestige of the resorts increases, sustainable practices decrease in favor of exclusivity and luxury. The images present Maldives resorts as places offering luxury and a connection to nature. Privacy, relaxation, and personalized experiences appear to be key features. Culinary experiences are also depicted as an important part of the guest experience, with gourmet dining presented in picturesque settings.

5. Conclusions

The main goal of the present work was to offer an integrated analysis of sustainability practices and environmental policies implemented across Maldivian resorts, exploring their alignment with the Maldives’ unique environmental context and current international standards.

The global shift towards sustainable development is upheld by international agreements and goals, implemented locally through individual initiatives, including those in the Maldives’ tourism sector. Key frameworks guiding this shift include (a) the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), with protocols that drive nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; (b) the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), focusing on biodiversity conservation; and (c) the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a core part of the UN’s 2030 Agenda. This Agenda, adopted on September 25, 2015, promotes sustainable development across environmental, social, and economic/governance (ESG) dimensions and comprises 17 goals with 169 targets.

For the Maldives, where tourism is a primary economic pillar and home to world-renowned resorts, these goals have two central implications: tourism and resort operations can contribute directly to achieving SDGs by aligning practices with sustainability standards. If not managed sustainably, tourism and resort activities could hinder progress toward these goals, especially due to the Maldives’ sensitive marine ecosystems and limited freshwater resources.

Overall, our results indicate that much progress is needed for Maldivian resorts to fully embrace sustainable practices and to publish these efforts transparently. Many resorts have yet to release data on their sustainability actions, reflecting a gap in accountability and transparency. Additionally, there is significant variation in the quality of the information shared, beginning with the inconsistent titles of the reports themselves, which suggests a lack of standardization in sustainability reporting across the sector.

Indeed, higher-rated resorts (i.e., Category 1 resorts), which often attract guests who value eco-luxury, tend to use sustainability to stand out and build their brand. They highlight their environmental initiatives in ways that appeal to environmentally-conscious guests. However, while these practices show some commitment to sustainability, they may not fully address deeper, long-term environmental challenges.

In contrast, mid-range (i.e., Category 2 resorts) and lower-rated resorts (i.e., Category 3 resorts) adopt more direct, operational sustainability practices, focusing on practical measures such as waste reduction, renewable energy use, and community engagement. These efforts, while often less polished in presentation, tend to target specific environmental challenges more effectively by embedding sustainability practices into daily operations. By actively involving local communities and implementing practical environmental conservation strategies, these resorts highlight a bottom-up approach to sustainability that aligns with the immediate needs of the local environment and stakeholders. This trend suggests a stratification within the Maldivian resort industry, where sustainability is approached variably across resort categories, with luxury-focused resorts often emphasizing eco-friendly branding while more modest resorts implement concrete environmental initiatives. This contrast raises essential questions about the adequacy of current practices in collectively supporting the Maldives’ national sustainability goals, given its acute vulnerability to climate and environmental changes.

Moreover, the study indicates significant disparities in the content and detail of sustainability communications across resort categories. Resorts targeting higher-end markets often emphasize luxurious, eco-friendly experiences—an approach that, while contributing to guest awareness, may risk positioning sustainability as a secondary benefit rather than a core responsibility. Middle- and lower-rated resorts, however, display a more grounded commitment to sustainability, often driven by the necessity to optimize resources and costs. This difference in approach reveals a potential gap in the Maldivian tourism sector’s overall commitment to sustainability, where luxury-driven sustainability initiatives may overshadow practical, community-centered environmental actions essential for the Maldives’ long-term resilience. As the Maldives faces significant threats from climate change, including rising sea levels, the findings underscore the varying levels of sustainability engagement among resorts, driven by factors such as resort classification, star rating, available resources, and target clientele.

The results of the present work also offer potential indications with respect to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established by the United Nations in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These goals provide a universal framework aimed at ending poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring prosperity for all by 2030. Overall, the present results indicate that all three categories of resorts in the Maldives have already started implementing policies that support education (Goal 4) by offering skill-building initiatives, promoting career opportunities, and engaging local communities to help reduce inequalities (Goal 10). There is also evidence that actions to address climate change (Goal 13) have already been implemented by these resorts.

However, there are still areas for improvement. Specifically, resorts in categories 1 and 3 could focus more on poverty reduction (Goal 1) and on promoting decent work and economic growth (Goal 8) by expanding local employment opportunities and encouraging inclusive economic development. Additionally, the tourism sector could play a greater role in promoting gender equality (Goal 5) by offering more employment opportunities to women and supporting gender representation, especially in higher-skilled roles.

Resorts should also prioritize sustainable food practices (Goal 2) by sourcing locally, thereby integrating regional food production into their offerings and benefiting both tourists and local producers. Encouraging sustainable consumption (Goal 12) and reducing waste are also essential steps in minimizing the environmental impact of tourism.

Responsible water management remains vital in the Maldives, where fresh water is scarce, and energy-intensive resort operations would benefit from adopting renewable energy sources (Goal 7) to enhance energy efficiency and support global climate goals. Infrastructure investments can improve the visitor experience, helping resorts maintain competitiveness while fostering innovation (Goal 9).

Moreover, resorts, especially in categories 1 and 2, should adopt sustainable practices to protect marine life (Goal 14), which is essential to the Maldives’ economy. Protecting biodiversity (Goal 15) supports ecosystem stability and helps preserve the Maldives’ natural appeal as a tourist destination.

Finally, achieving the SDGs in the Maldives relies on partnerships (Goal 17) among government, private sectors, and communities. Such collaborations maximize tourism’s positive contributions to sustainability across all dimensions.

Some limitations should also be acknowledged. First, the reliance on publicly available sustainability reports inherently constrains the analysis of self-reported data, which may be selectively disclosed or influenced by marketing considerations. Not all resorts may equally emphasize every aspect of sustainability, potentially resulting in underreporting of certain practices or overemphasis on others aligned with marketing goals. Additionally, variations in report quality and format complicate cross-resort comparisons, as different resorts interpret and present sustainability metrics in diverse ways. This lack of standardization in reporting not only impacts comparability but may also obscure true sustainability performance. Furthermore, the study focuses on resorts with available online documentation, potentially excluding smaller or resource-limited establishments that may lack formalized sustainability reporting but could still contribute meaningfully to local environmental efforts.

In light of the findings, establishing standardized guidelines for stakeholders in the tourism sector, especially those operating within fragile ecosystems, is an urgent priority. The disparities observed across resort categories underscore the need for a unified framework to ensure consistent, transparent, and verifiable sustainability practices within the Maldivian tourism sector. Such guidelines would benefit from alignment with international reporting standards, such as the forthcoming CSRD. A standardized reporting framework could enable accurate assessment of each resort’s sustainability commitments and progress, allowing policymakers and tourists to make informed decisions in alignment with global sustainability goals. Such frameworks would encourage all resort categories to integrate sustainability as a core element rather than a peripheral or marketing-driven addition, fostering greater accountability and long-term resilience across the sector.

The Maldives is at a pivotal moment where its dependence on tourism must be carefully balanced with the urgent need for sustainable environmental practices to counter severe environmental degradation and the existential threat of rising sea levels (Mörner et al., 2004). Ensuring the long-term viability of its tourism sector requires unified, strengthened sustainability efforts across all resort categories, supported by clear, actionable guidelines. Understanding the current state of sustainable practices and how these efforts are communicated to the public, institutions, and stakeholders is essential for fostering a truly responsible tourism industry. For tourism businesses, this involves adopting environmentally friendly practices and sharing their progress openly, building trust and accountability (Tang & Higgins, 2022). Transparent communication boosts public and institutional support, shapes policies that further environmental goals (Scott, 1999), and encourages tourists to behave responsibly (Li et al., 2024). Together, these initiatives lay the groundwork for sustainable tourism that protects the Maldives’ unique natural heritage, secures its future as a premier destination, and sets a global standard for island nations facing similar ecological challenges.

By incentivizing resorts and other tourism-related businesses to implement eco-friendly practices, the Maldives can work towards preserving its ecosystems, protecting its tourism-dependent economy, and setting a benchmark for sustainable tourism in other vulnerable island nations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Paolo Galli, Diana Cerini, Federica Doni, Shazla Mohamed, Mohamed Sami Zitouni, Hussain Al Ahmad and Alessandro Gabbiadini; methodology, Alessandro Gabbiadini; software, Alessandro Gabbiadini; validation, Alessandro Gabbiadini and Paolo Galli; formal analysis, Alessandro gabbiadini; investigation, Paolo Galli, Diana Cerini, Federica Doni, Shazla Mohamed, Mohamed Sami Zitouni, Hussain Al Ahmad and Alessandro gabbiadini; resources, paolo Galli and Eleonotra Concari; data curation, Eleonora Concari; writing—original draft preparation, Paolo Galli, Diana Cerini, Erika Scuderi, Federica Doni, Shazla Mohamed, Mohamed Sami Zitouni, Hussain Al Ahmad and Alessandro Gabbiadini; writing—review and editing, Paolo Galli, Diana Cerini, Federica Doni, Shazla Mohamed, Mohamed Sami Zitouni, Hussain Al Ahmad and Alessandro Gabbiadini; visualization, Alessandro Gabbiadini; supervision, Paolo Galli.; funding acquisition, paolo Galli All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by: MUSA – Multilayered Urban Sustainability Action – project, funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU, under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) Mission 4 Component 2 Investment Line 1.5: Strengthening of research structures and creation of R&D “innovation ecosystems”, set up of “territorial leaders in R&D”.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to Giorgia Marazzi, the Honorary Consul of Italy in the Maldives, for providing support in obtaining the information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afeltra, G., Korca, B., Costa, E., & Tettamanzi, P. (2023). The quality of voluntary and mandatory disclosures in company reports: A systematic literature network analysis. Accounting Forum. [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative research, 15(2), 219-234. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Chew, R., Bollenbacher, J., Wenger, M., Speer, J., & Kim, A. (2023). LLM-assisted content analysis: Using large language models to support deductive coding. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2306.14924.

- Clarke, V. Clarke, V., Braun, V. & Hayfield, N. (2015) Thematic Analysis. In: Smith, J.A., Ed., Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, SAGE Publications, London, 222-248.

- Council of the European Union & European Parliament. (2000). Directive 2000/60/EC establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy. Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 327, 1–73.

- Council of the European Union & European Parliament. (2022). Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as regards corporate sustainability reporting. Official Journal of the European Union, PE/35/2022/REV/1, OJ L 322, 15–80.

- Council of the European Union & European Parliament. (2024). Directive (EU) 2024/1760 of the European Parliament and of the Council on corporate sustainability due diligence. Official Journal of the European Union, PE/9/2024/REV/1, OJ L, 2024/1760. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1760/oj.

- De Paoli, S. (2024). Performing an inductive thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with a large language model: an exploration and provocation on the limits of the approach. Social Science Computer Review, 42(4), 997-1019. [CrossRef]

- Dienes, D., Sassen, R., & Fischer, J. (2016). What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 7(2), 154-189. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2020). A new circular economy action plan for a cleaner and more competitive Europe (COM/2020/98 final).

- European Commission. (2020). EU biodiversity strategy for 2030: Bringing nature back into our lives (COM/2020/380 final).

- European Commission. (2023). Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Finance. https://finance.ec.europa.eu/capital-markets-union-and-financial-markets/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en.

- European Union. (2016). Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. OJ C 202, 1–388.

- European Union. (2021). REGULATION (EU) 2021/1119 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (European Climate Law). Official Journal of the European Union, PE/27/2021/REV/1, OJ L 243, 9.7.2021, p. 1–17. http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/1119/oj.

- Ferrero-Ferrero, I., Muñoz-Torres, M. J., Rivera-Lirio, J. M., Escrig-Olmedo, E., & Fernández-Izquierdo, M. Á. (2024). Sustainable development goals in the hospitality industry: a dream or reality?. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 20(5), 773-796. [CrossRef]

- Fifth Tourism Master Plan 2023-2027: Goals and Strategies. (2023). Government of Maldives, represented by the Ministry of Tourism. https://www.tourism.gov.mv/dms/document/4969b4831928f1bdf3506340fb6974fc.pdf.

- Font, X., Garay, L., & Jones, S. (2016). Sustainability motivations and practices in small tourism enterprises in European protected areas. Journal of Cleaner production, 137, 1439-1448. [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Namey, E. E., & Mitchell, M. L. (2013). Collecting qualitative data: A field manual for applied research. Sage.

- Guillen, J. J. G., & Baqué, D. T. (2024). Sustainability and the environmental impact of the tourism industry: An analysis of the hotel sector in Catalonia, Spain. Intangible Capital, 20(1), 277-297. [CrossRef]

- Guix, M., Bonilla-Priego, M. J., & Font, X. (2018). The process of sustainability reporting in international hotel groups: An analysis of stakeholder inclusiveness, materiality and responsiveness. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(7), 1063-1084. [CrossRef]

- Guix, M., & Font, X. (2022). Consulting on the European Union’s 2050 tourism policies: An appreciative inquiry materiality assessment. Annals of Tourism Research, 93, 103353. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R., & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of cleaner production, 59, 5-21. [CrossRef]

- Iazzi, A., Pizzi, S., Iaia, L., & Turco, M. (2020). Communicating the stakeholder engagement process: A cross-country analysis in the tourism sector. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1642-1652. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F. (2012) Dynamics of Marketing of Star Hotels, Products, & Services. Partridge Publishing Singapore.

- Khatter, A., McGrath, M., Pyke, J., White, L., & Lockstone-Binney, L. (2019). Analysis of hotels’ environmentally sustainable policies and practices: Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in hospitality and tourism. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(6), 2394-2410.

- King, C. (2024). Maldives tourism climate action plan : strategic pathways for climate resiliency in tourism. Ministry of Tourism, Maldives ; United States Agency for International Development.

- Li, J., Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., Nguyen, T. H. H., & Morrison, A. M. (2024). Sustainable tourist behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Sustainable Development, 32(4), 3356-3374. [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A., Srivastava, S., Ferraris, A., & Dhir, A. (2022). Corporate social responsibility and sustainability in the tourism sector: A systematic literature review and future outlook. Sustainable Development, 30(3), 447-461. [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, S., & Di Friedberg, M. S. (2017). Environmental policy and climate change vulnerability in the Maldives: from the ‘lexicon of risk’ to social response to change. Island Studies Journal, 12(1), 53-70. [CrossRef]

- Mann, T., Bender, M., Lorscheid, T., Stocchi, P., Vacchi, M., Switzer, A. D., & Rovere, A. (2019). Holocene sea levels in southeast Asia, Maldives, India and Sri Lanka: the SEAMIS database. Quaternary Science Reviews, 219, 112-125. [CrossRef]

- Mathis, W. S., Zhao, S., Pratt, N., Weleff, J., & De Paoli, S. (2024). Inductive thematic analysis of healthcare qualitative interviews using open-source large language models: How does it compare to traditional methods?. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 255, 108356. [CrossRef]

- McNally, M. A., & Maroun, W. (2018). It is not always bad news: Illustrating the potential of integrated reporting using a case study in the eco-tourism industry. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(5), 1319-1348.

- Mondo Maldive. (2019). Resorts and Villages in the Maldives. https://mondomaldive.it/it/.

- Morgan, H. (2022). Understanding Thematic Analysis and the Debates Involving Its Use. The Qualitative Report, 27(10), 2079-2091. [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N. A., Tooley, M., & Possnert, G. (2004). New perspectives for the future of the Maldives. Global and planetary change, 40(1-2), 177-182. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J. (2016). You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. [CrossRef]

- Republic of Maldives. (1993/2014). Environmental Protection and Preservation Act: Law No. 4/1993, amended 12/2014.

- Republic of Maldives. (1999). Tourism Act: No. 2/1999.

- Republic of Maldives. (2021). Climate Emergency Act: No. 9/2021.

- Scheyvens, R., (2011). The challenge of sustainable tourism development in the Maldives: Understanding the social and political dimensions of sustainability. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 52, No. 2. [CrossRef]

- Scott, A. (1999). Trust law, sustainability, and responsible action. Ecological Economics, 31(1), 139-154. [CrossRef]

- Siew, R. Y. (2015). A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). Journal of environmental management, 164, 180-195. [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J. E., Pollard, C. E., & Evans, M. R. (2012). The triple bottom line: A framework for sustainable tourism development. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 13(3), 233-258. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S., & Higgins, C. (2022). Do not forget the “How” along with the “What”: Improving the transparency of sustainability reports. California Management Review, 65(1), 44-63. [CrossRef]

- Techera, E. J., & Cannell-Lunn, M. (2019). A review of environmental law in Maldives with respect to conservation, biodiversity, fisheries, and tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law, 22(2), 228–256. [CrossRef]

- Traxler, A. A., Schrack, D., & Greiling, D. (2020). Sustainability reporting and management control–A systematic exploratory literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 276, 122725.

- United Nations Tourism Organization. (n.d.). Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through tourism – Toolkit of indicators for projects (TIPs). Tourism for SDGs Platform.

- United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf.

- United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. T.I.A.S. No. 16-1104.

- Wolf, F., Moncada, S., Surroop, D., Shah, K. U., Raghoo, P., Scherle, N., ... & Nguyen, L. (2024). Small island developing states, tourism and climate change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(9), 1965-1983.

- Zou, X. (2019). A review of object detection techniques. In 2019 International conference on smart grid and electrical automation (ICSGEA). IEEE. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports by Category 1 resorts. Nodes represent the themes and their sizes are proportional to the number of sentences supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of sentences that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of sentences connecting the two themes.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports by Category 1 resorts. Nodes represent the themes and their sizes are proportional to the number of sentences supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of sentences that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of sentences connecting the two themes.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports by Category 2. Nodes represent the themes and their sizes are proportional to the number of sentences supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of sentences that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of sentences connecting the two themes.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports by Category 2. Nodes represent the themes and their sizes are proportional to the number of sentences supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of sentences that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of sentences connecting the two themes.

Figure 3.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes for Category 3 resort reports. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of sentences supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of sentences that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of sentences connecting the two themes.

Figure 3.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes for Category 3 resort reports. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of sentences supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of sentences that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of sentences connecting the two themes.

Figure 4.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports for Category 1. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of images supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of images that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of images connecting the two themes.

Figure 4.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports for Category 1. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of images supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of images that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of images connecting the two themes.

Figure 5.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports for Category 2. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of images supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of images that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of images connecting the two themes.

Figure 5.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports for Category 2. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of images supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of images that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of images connecting the two themes.

Figure 6.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports for Category 3 resorts. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of images supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of images that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of images connecting the two themes.

Figure 6.

Visual representation of the relationship between the extracted themes when considering the reports for Category 3 resorts. Nodes represent the themes, and their sizes are proportional to the number of images supporting them. Edges represent the relationships between themes, with the thickness of the edges corresponding to the number of images that connect the themes. Edge labels display the number of images connecting the two themes.

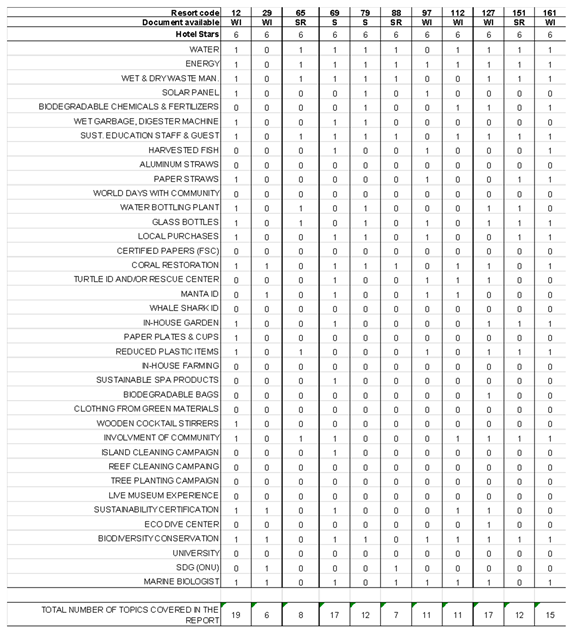

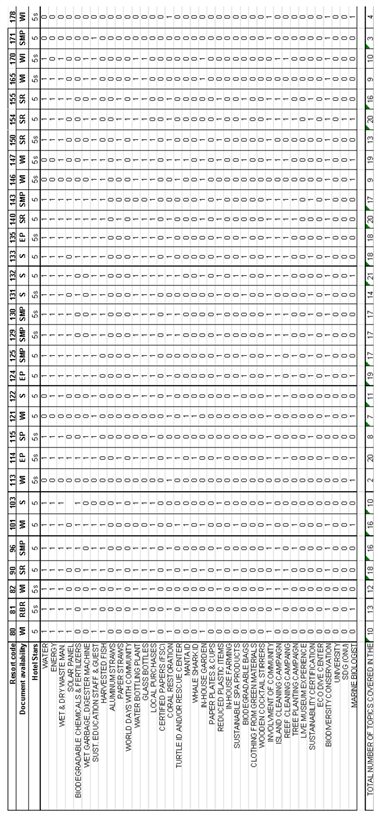

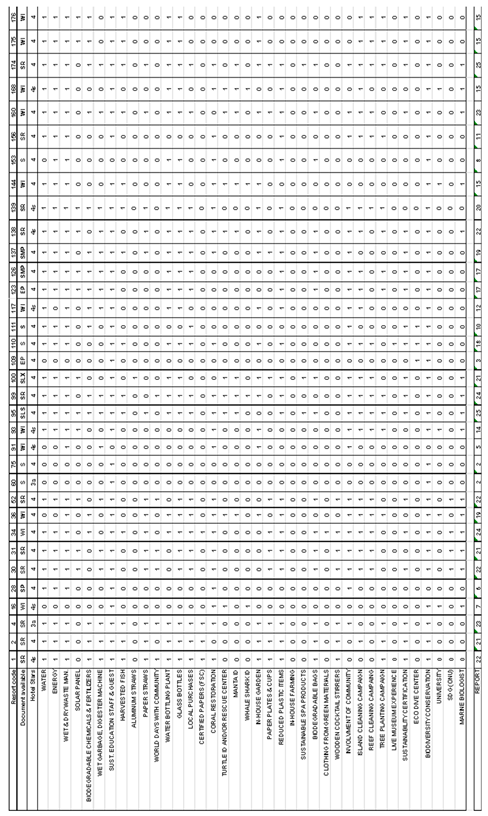

Table 1.

Themes Addressed in the Sustainability Reports Related to the 6-Star Resorts. Sustainability: S; Sustainability report: SR; Website Information: WI.

Table 1.

Themes Addressed in the Sustainability Reports Related to the 6-Star Resorts. Sustainability: S; Sustainability report: SR; Website Information: WI.

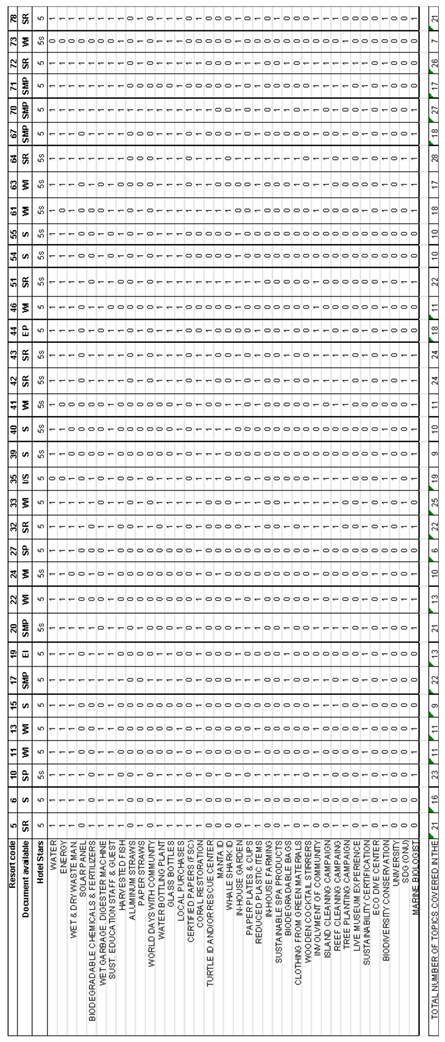

Table 2.

Themes Addressed in the Sustainability Reports Related to the 5-Star Resorts. Environmental initiatives: EI; Environmental Social and Governance Report: ESG; Environmental Policy: EP; Information: I; Responsible Business Report: RBR; Sustainable Luxury: SLX; Sustainability: S; Sustainability Management Plan: SMP; Sustainability Policy: SP; Sustainability report: SR; Sustainable Life Style: SLS; Website Information: WI.

Table 2.

Themes Addressed in the Sustainability Reports Related to the 5-Star Resorts. Environmental initiatives: EI; Environmental Social and Governance Report: ESG; Environmental Policy: EP; Information: I; Responsible Business Report: RBR; Sustainable Luxury: SLX; Sustainability: S; Sustainability Management Plan: SMP; Sustainability Policy: SP; Sustainability report: SR; Sustainable Life Style: SLS; Website Information: WI.

Table 3.

Themes Addressed in the Sustainability Reports Related to the 3-Star and 4-Star Resorts. Environmental initiatives: EI; Environmental Policy: EP; Information: I; Responsible Business Report: RBR; Sustainable Luxury: SLX; Sustainability: S; Sustainability Management Plan: SMP; Sustainability Policy: SP; Sustainability report: SR; Sustainable Life Style: SLS; Website Information: v.

Table 3.

Themes Addressed in the Sustainability Reports Related to the 3-Star and 4-Star Resorts. Environmental initiatives: EI; Environmental Policy: EP; Information: I; Responsible Business Report: RBR; Sustainable Luxury: SLX; Sustainability: S; Sustainability Management Plan: SMP; Sustainability Policy: SP; Sustainability report: SR; Sustainable Life Style: SLS; Website Information: v.

Table 4.

Extracted themes for Category 1, definitions, and supporting quotes.

Table 4.

Extracted themes for Category 1, definitions, and supporting quotes.

| Theme |

Short definition |

Supporting quotes from the transcript |

| Environmental Conservation Efforts |

Efforts to preserve natural ecosystems and biodiversity through sustainable practices and restoration projects. |

Our resort team strives towards minimizing our environmental footprint by implementing sustainable initiatives and action plans".

"We’ve linked with Sri Lanka’s Modern Agri to develop smart watering systems, a hydroponic greenhouse, and orchid house". |

| Community Engagement and Education |

Programs involving local communities in conservation and sustainability education. |

We love to support our community and give back".

"We believe in a natural excellence in everything we do, whether it is delivering the ultimate in guest experiences or providing energy to the rural poor in Myanmar via the Soneva Foundation" |

| Sustainable Tourism Practices |

Tourism practices that focus on environmental sustainability and promote local culture. |

We’ve committed to saving energy and water, reducing and recycling waste".

"Aiming for greener agriculture, we’ve linked with Sri Lanka’s Modern Agri to develop smart watering systems |

Table 5.

Extracted themes for Category 2, definitions, and supporting quotes.

Table 5.

Extracted themes for Category 2, definitions, and supporting quotes.

| Environmental Sustainability Efforts |

Initiatives aimed at reducing environmental impact and conserving resources. |

The shredder machine is a powerful tool designed specifically for processing green waste efficiently

Our in-house bottling plant has been producing an impressive yearly output of over 300,000 liters of water |

| Local Community Engagement |

Efforts to support and engage with the local community. |

Support vocational training and skills development initiatives for employability in the tourism sector.

Actively promote the resort’s involvement in local community and charity initiatives |

| Employee Training and Welfare |

Training programs and welfare initiatives for employees. |

To ensure our standard in delivery of customer services, Employee training and engagement strategy is followed.

"Conduct ongoing performance reviews and promote based on merit |

| Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Management |

Strategies to ensure customer satisfaction and manage relationships. |

Monitor customer satisfaction through various channels, including Customer Satisfaction Cards, guest emails, and online platforms.

Ensure clear communication of sustainable practices, plans, and strategies to guests |

Table 6.

Extracted themes for Category 3 resorts, definitions, and supporting quotes.

Table 6.

Extracted themes for Category 3 resorts, definitions, and supporting quotes.

| Theme |

Short definition |

Supporting quotes from the transcript |

| Sustainability Certification and Commitment |

Commitment to achieving and maintaining sustainability certifications, demonstrating continuous improvement in environmental practices. |

"Our goal is to continuously enhance our sustainability efforts and consistently improve with each yearly renewal."

"Sustainability at [omissis] resort means conducting our business while being mindful of global environmental concerns and our responsibility towards the environment." |

| Waste Management and Reduction |

Strategies to reduce non-recyclable waste and increase recycling rates to minimize environmental impact. |

"We have invested in a Wet Garbage Digester Machine to reduce our waste output and promote sustainable food practices."

"This is why we have a composting plant for organic waste which handles 250 kg of wet waste per day." |

| Energy and Water Conservation |

Initiatives to conserve energy and water, optimize efficiency, and use renewable energy sources. |

"We have implemented a range of energy-saving measures, such as using energy-efficient lighting and air conditioning systems."

"Our sustainability journey is built on managing and reducing the use of energy and water." |

| Community Engagement and Education |

Efforts to engage and educate local communities on sustainability and support local development. |

"We organized a thorough island cleaning initiative, involving local residents."

"Promote interaction with the local community and organize Maldivian-themed events and expeditions." |

| Biodiversity and Environmental Protection |

Conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems through resource conservation and pollution reduction initiatives. |

"The resort initiated a coral planting program, carefully transplanting coral fragments to damaged areas of the reef."

"We are committed to reducing our ecological footprint and championing local conservation initiatives." |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).