Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

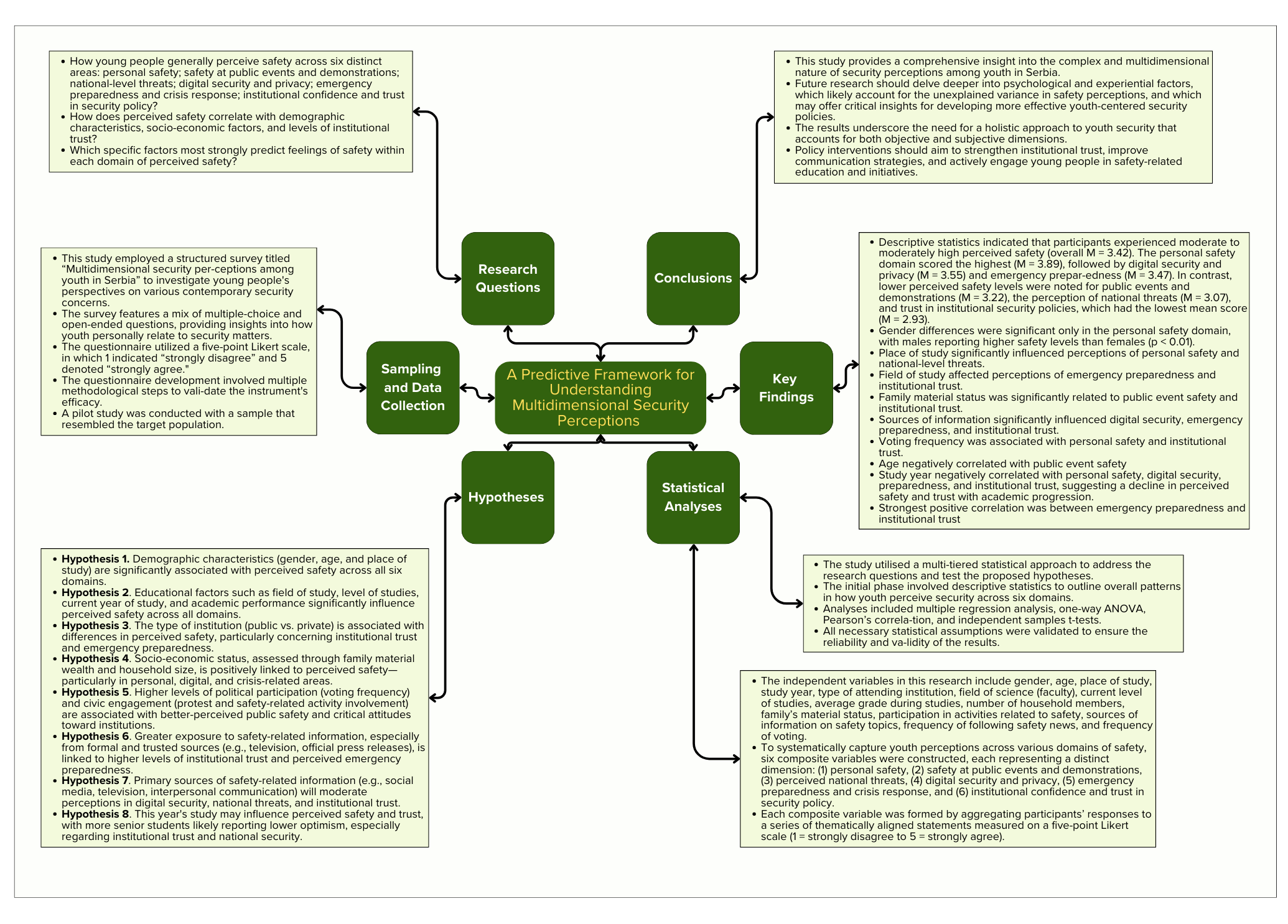

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

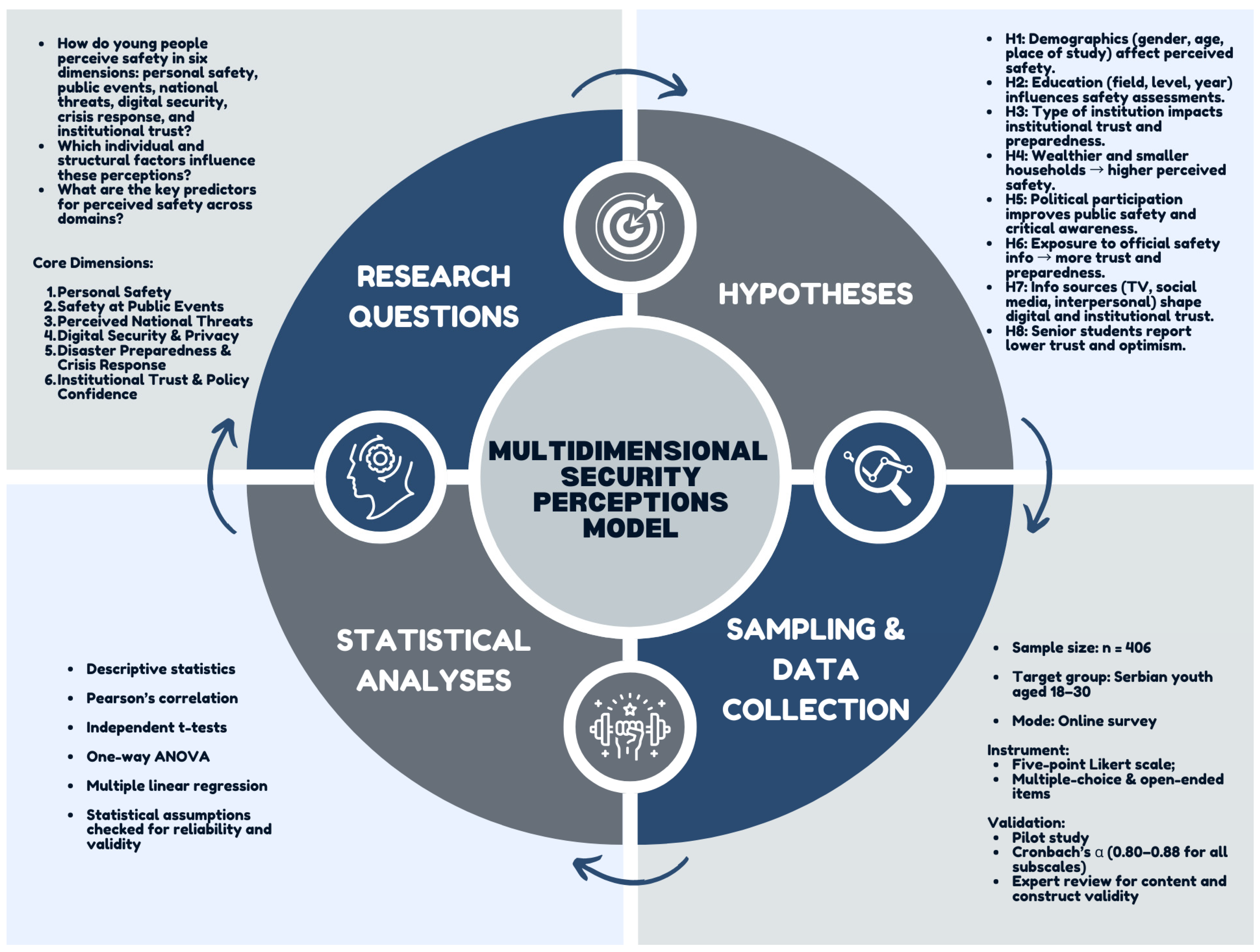

2. Methods

2.1. Hypotheses

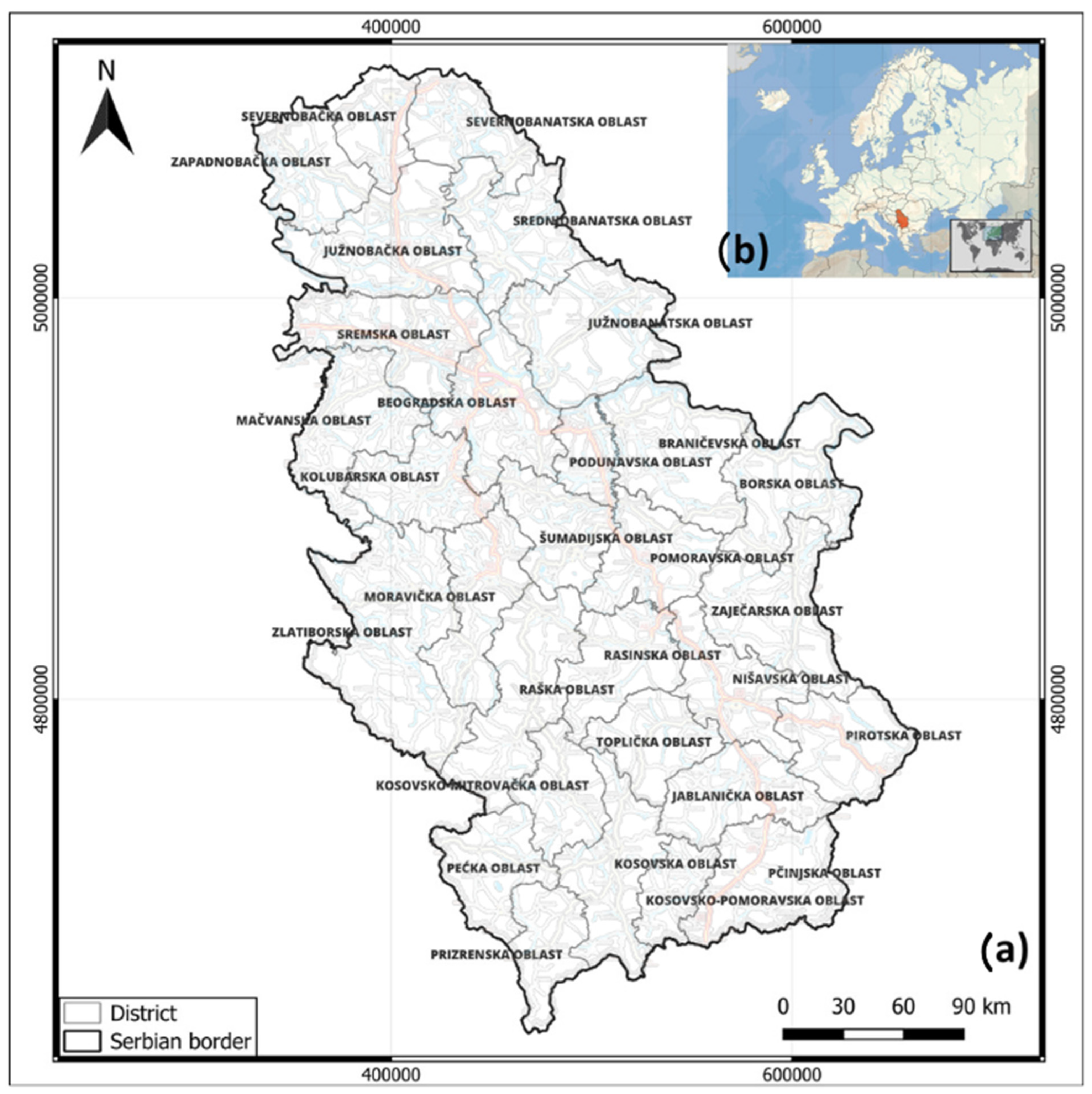

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Characteristics

2.3. Questionnaire Design

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Youth Perceptions of Personal Safety in Serbia

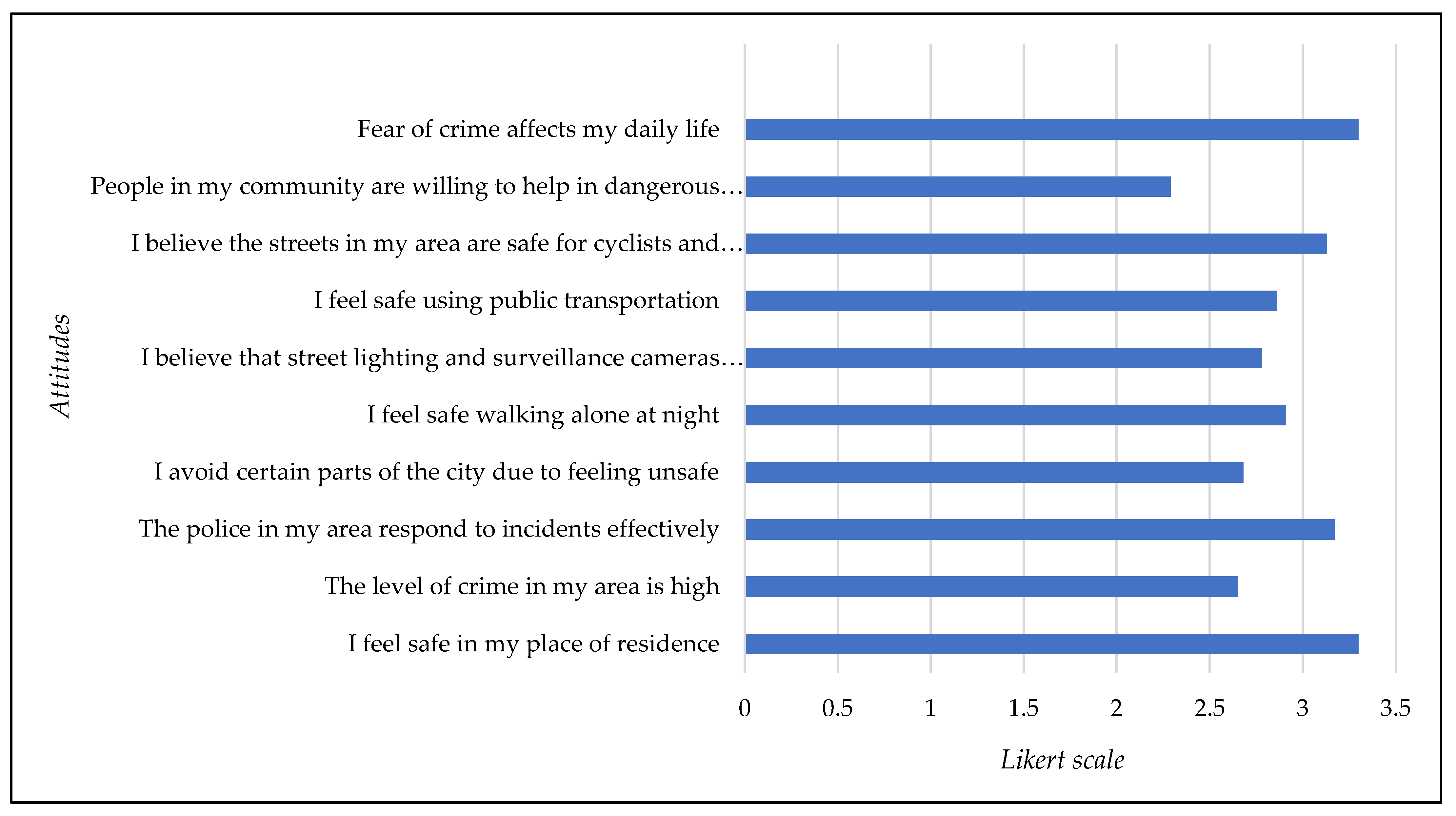

3.1.1. Perceptions of Personal Safety

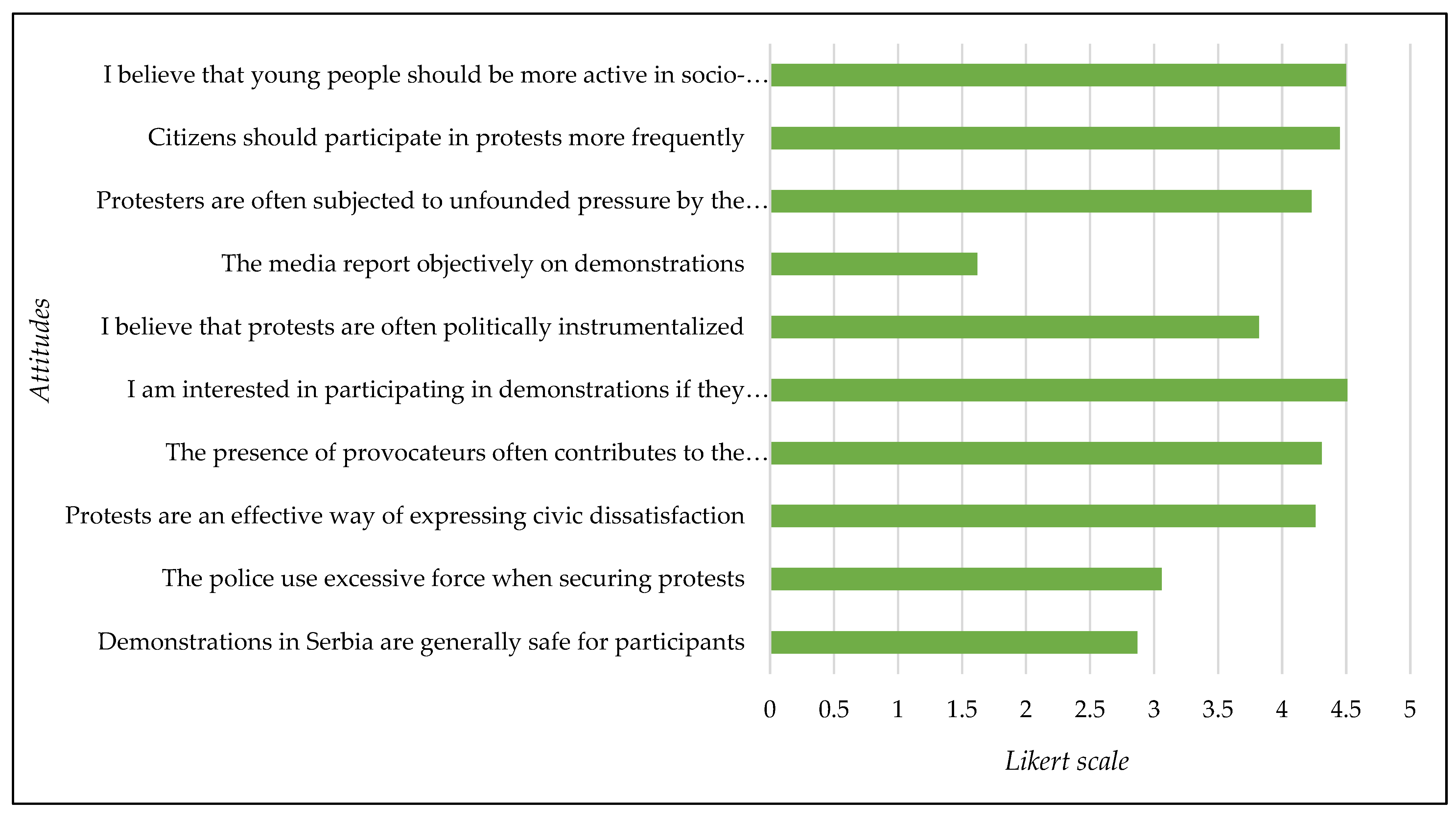

3.1.2. Perceptions of Safety at Public Events and Demonstrations

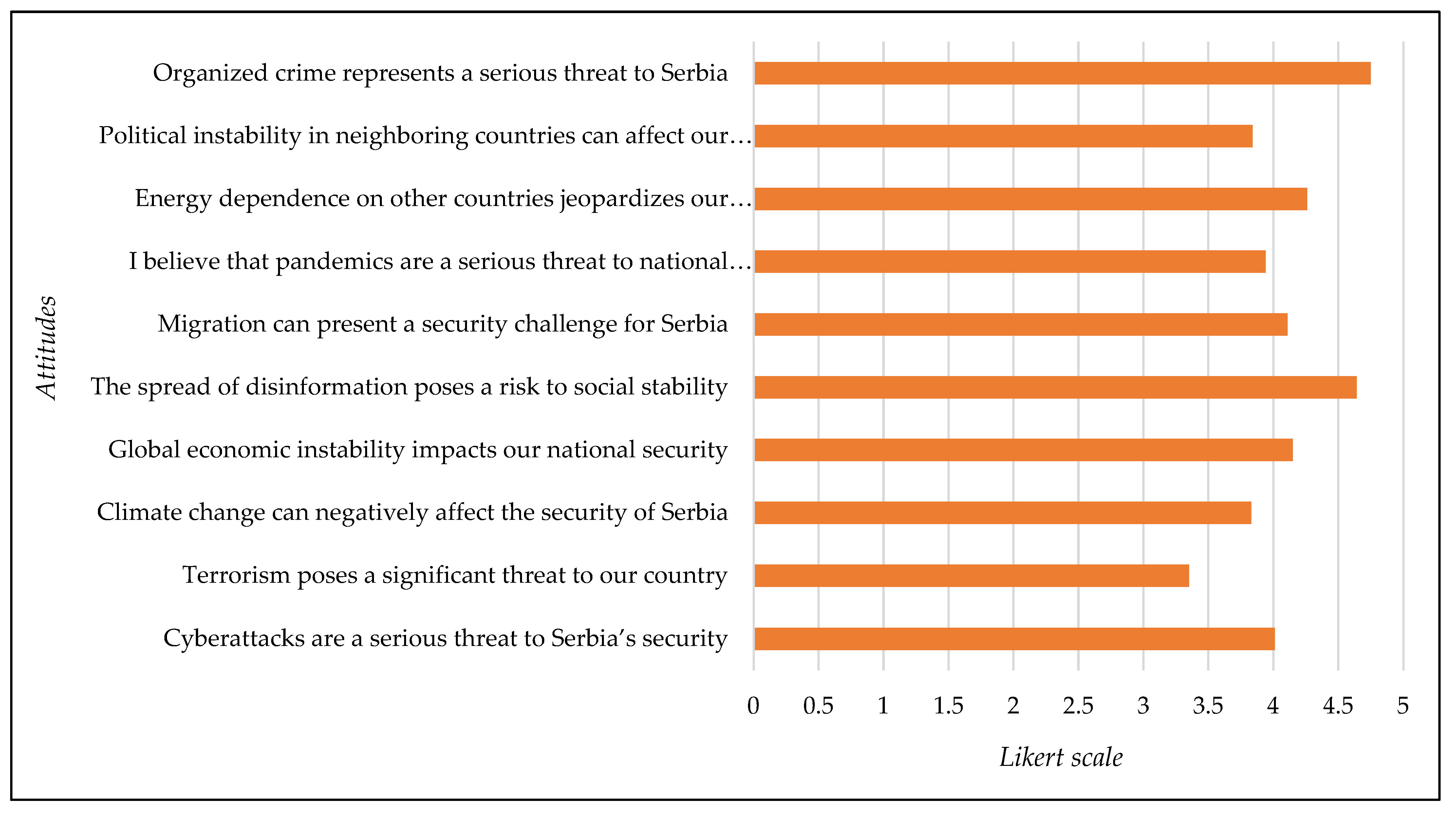

3.1.3. Perceptions of National-Level Threats

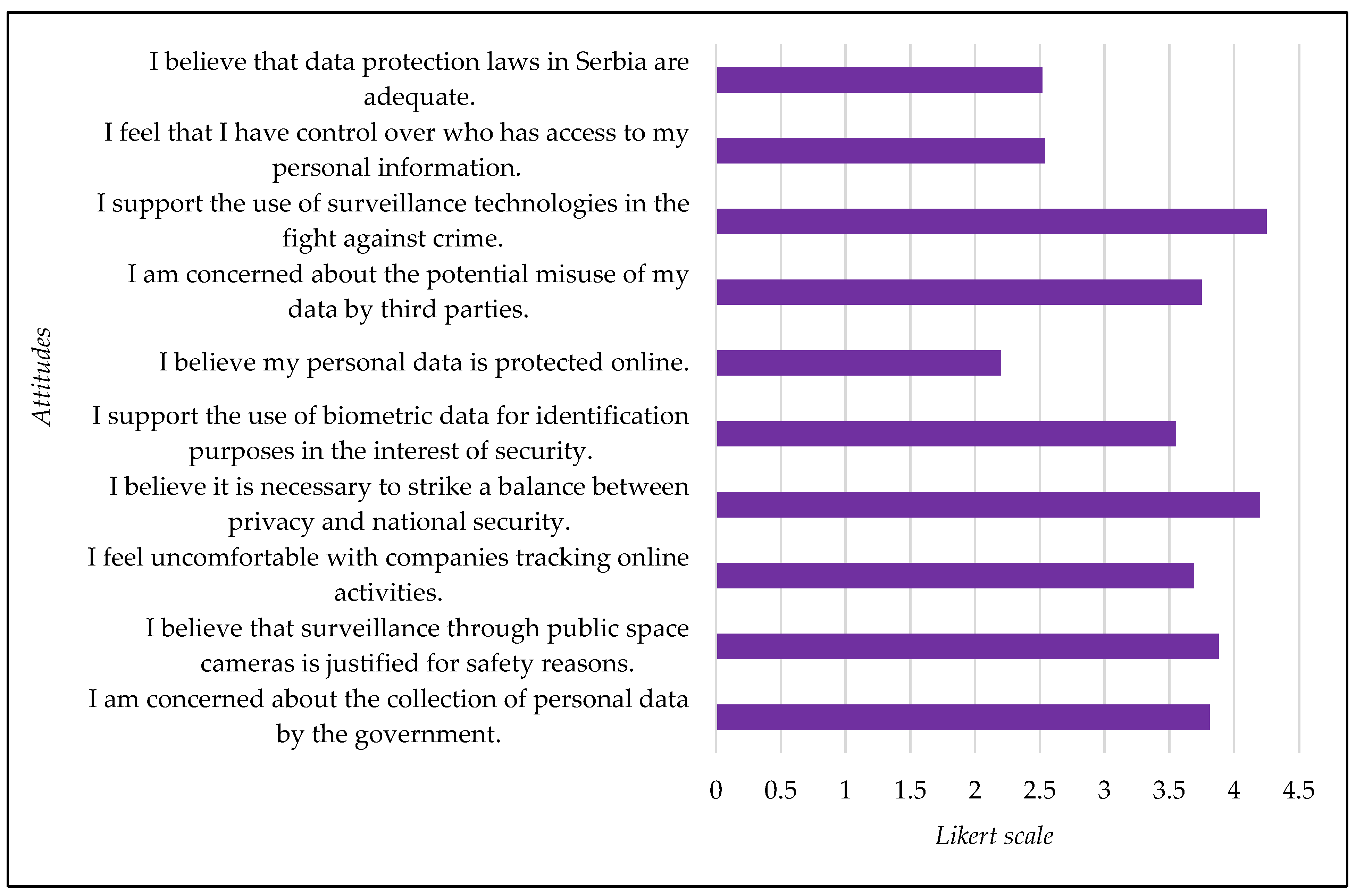

3.1.4. Perceptions of Digital Security and Privacy

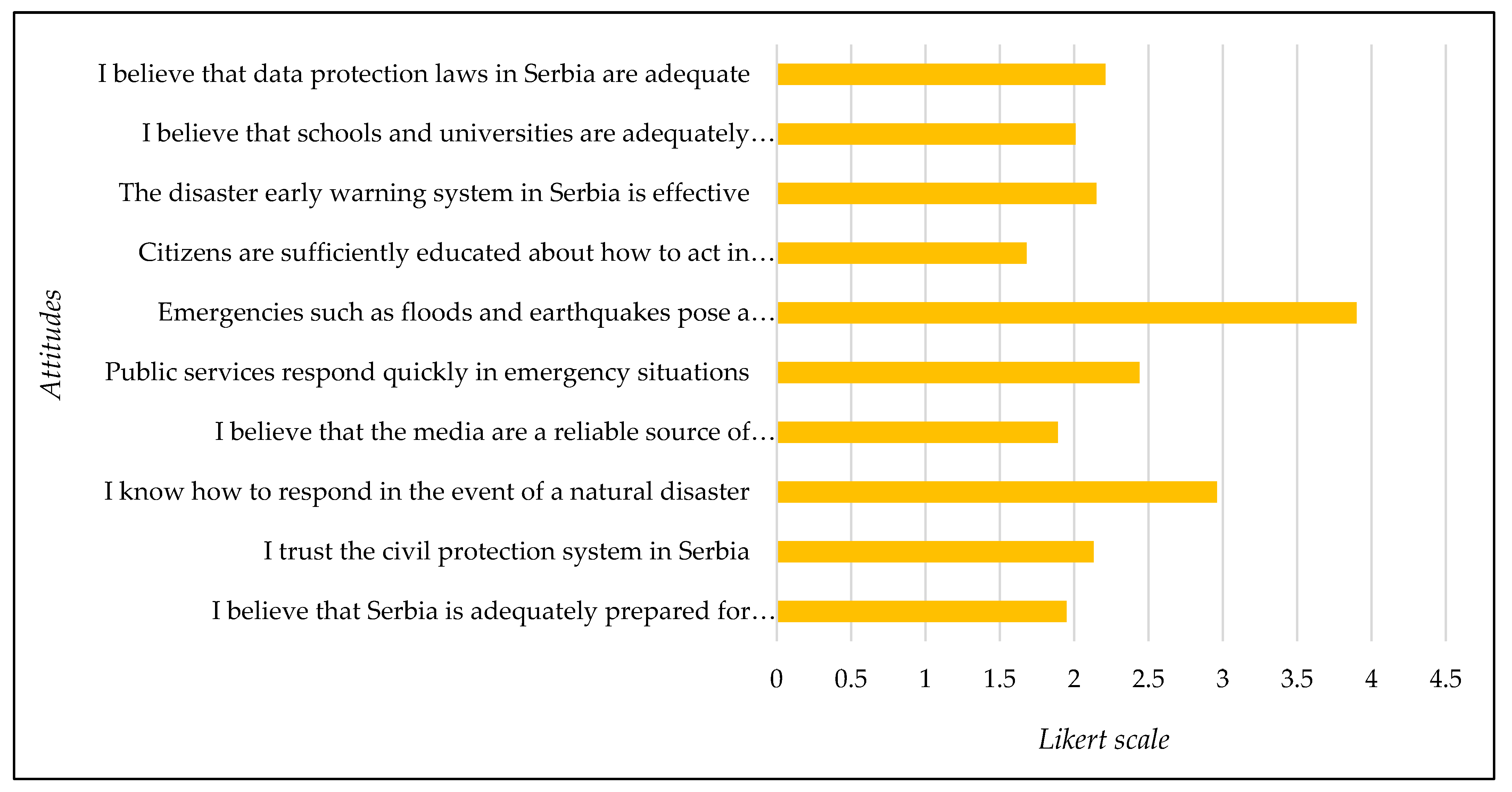

3.1.5. Perceptions of Disaster Preparedness and Crisis Response

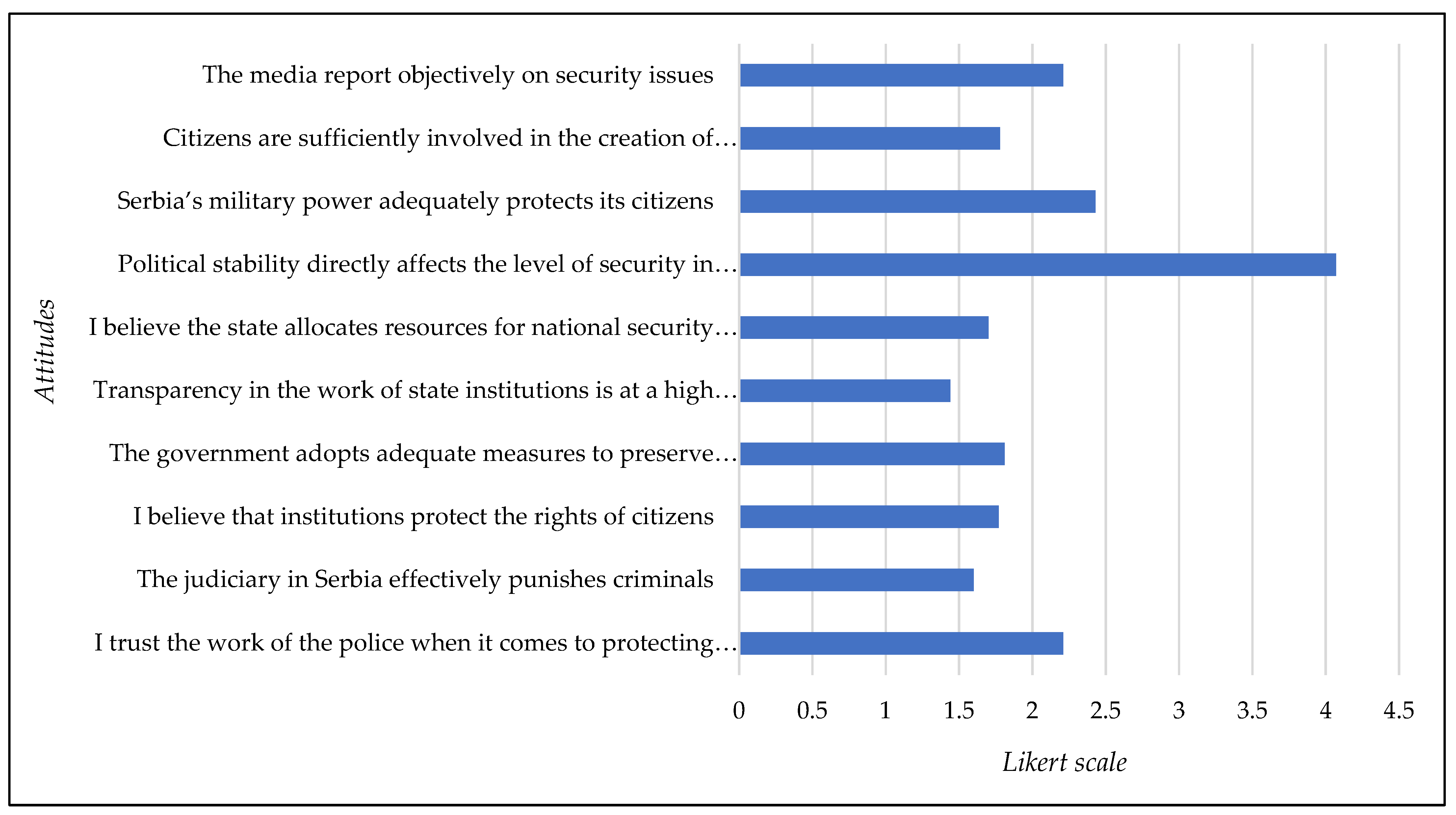

3.1.6. Perceptions of Institutional Confidence and Trust in Security Policy

3.2. Correlations and Effects of Socio-Demographic Factors on Perceived Personal Safety

3.2.1. Group Differences in Perceptions of Safety, Preparedness, and Institutional Trust: Independent Samples T-Test Results

3.2.2. Correlational Analysis of Demographic and Socioeconomic Predictors of Perceived Security

| Variable | Age | Personal Safety | Safety at public events and demonstrations |

National-level threats | Digital security and privacy | Disaster preparedness and crisis response |

Institutional confidence and trust in security policy |

| Age | 1.00 | ||||||

| Personal Safety | –0.03 | 1.00 | |||||

| Safety at public events and demonstrations | –0.16** | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| National-level threats | –0.04 | 0.03 | 0.28** | 1.00 | |||

| Digital security and privacy | –0.09 | 0.22** | 0.14** | 0.25** | 1.00 | ||

| Disaster preparedness and crisis response | –0.08 | 0.43** | –0.18** | 0.02 | 0.36** | 1.00 | |

| Institutional confidence and trust in security policy | –0.07 | 0.36** | –0.32** | –0.01 | 0.22** | 0.64** | 1.00 |

| Variable | Current year of study | Personal Safety | Safety at public events and demonstrations |

National-level threats | Digital security and privacy | Disaster preparedness and crisis response |

Institutional confidence and trust in security policy |

| Age | 1.00 | ||||||

| Personal Safety | –0.14** | 1.00 | |||||

| Safety at public events and demonstrations | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| National-level threats | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.28** | 1.00 | |||

| Digital security and privacy | –0.16** | 0.22** | 0.14** | 0.25** | 1.00 | ||

| Disaster preparedness and crisis response | –0.15** | 0.43** | –0.18** | 0.02 | 0.36** | 1.00 | |

| Institutional confidence and trust in security policy | –0.17** | 0.35** | –0.31** | –0.01 | 0.21** | 0.64** | 1.00 |

| Variable | Average grade | Personal Safety | Safety at public events and demonstrations |

National-level threats | Digital security and privacy | Disaster preparedness and crisis response |

Institutional confidence and trust in security policy |

| Age | 1.00 | ||||||

| Personal Safety | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Safety at public events and demonstrations | –0.07 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| National-level threats | –0.08 | 0.03 | 0.28** | 1.00 | |||

| Digital security and privacy | –0.15* | 0.22** | 0.14** | 0.25** | 1.00 | ||

| Disaster preparedness and crisis response | –0.10 | 0.43** | –0.18** | 0.02 | 0.36** | 1.00 | |

| Institutional confidence and trust in security policy | –0.04 | 0.36** | –0.32** | –0.01 | 0.22** | 0.64** | 1.00 |

| Variable | Household size | Personal Safety | Safety at public events and demonstrations |

National-level threats | Digital security and privacy | Disaster preparedness and crisis response |

Institutional confidence and trust in security policy |

| Age | 1.00 | ||||||

| Personal Safety | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Safety at public events and demonstrations | 0.03 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| National-level threats | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.28** | 1.00 | |||

| Digital security and privacy | 0.06 | 0.22** | 0.14** | 0.25** | 1.00 | ||

| Disaster preparedness and crisis response | 0.05 | 0.43** | –0.18** | 0.02 | 0.36** | 1.00 | |

| Institutional confidence and trust in security policy | –0.01 | 0.36** | –0.32** | –0.01 | 0.22** | 0.64** | 1.00 |

3.2.3. ANOVA Analysis of Sociodemographic and Informational Determinants of Perceived Security

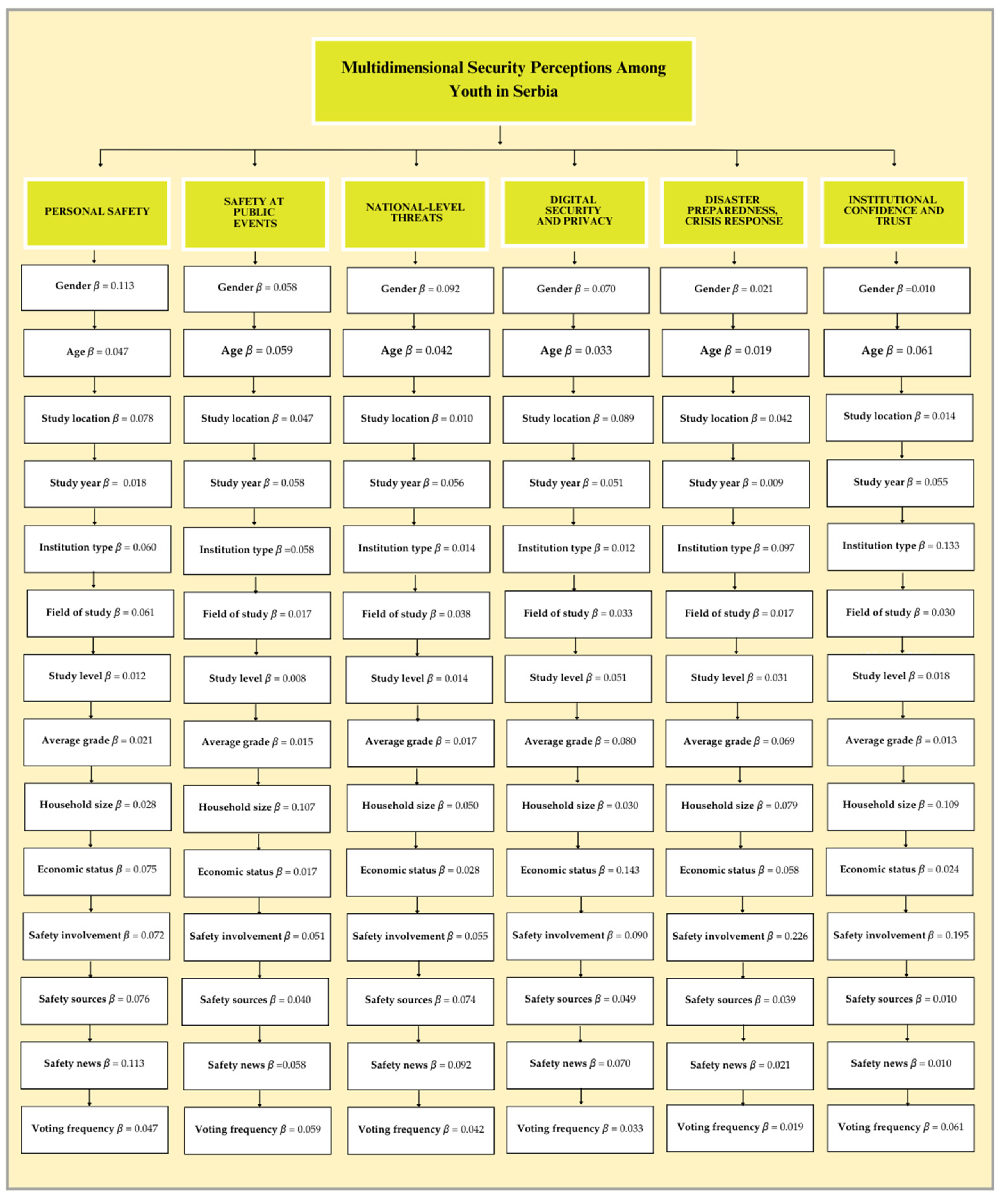

3.3. Predictors of Perceived Personal Safety: Regression Model Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Dear Participant,

- Your voice can contribute to improving the security system and protecting the rights of young people in Serbia.

- Understanding security risks allows for better protection measures in emergency situations.

- We will gain a more realistic picture of how safe young people really are – on the street, in the digital space, at public events, and during emergencies.

- The research helps identify problems and propose solutions that can enhance your safety.

- It is anonymous – your answers will be used solely for research purposes.

- It does not require much time – completing the questionnaire takes 10–15 minutes.

- It includes different types of questions—some are open-ended, while others ask you to rate statements on a scale from 1 to 5 (1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree).

- Please fill out the following basic information. The data are anonymous and will be used solely for research purposes.

- Gender:

- ☐ Male

- ☐ Female

- ☐ Other / Prefer not to say

- Age:

- _______________ (enter your age, e.g., 23)

- Place of study:

- ☐ Belgrade

- ☐ Novi Sad

- ☐ Niš

- ☐ Kragujevac

- ☐ Other city (please specify): ______________

- Type of institution you are attending:

- ☐ Public

- ☐ Private

- Your faculty belongs to the following field of science:

- ☐ Technical-technological sciences

- ☐ Natural and mathematical sciences

- ☐ Medical sciences

- ☐ Social and humanistic sciences

- Current level of studies:

- ☐ Professional studies

- ☐ Undergraduate academic studies

- ☐ Specialist studies

- ☐ Master’s academic studies

- ☐ Doctoral studies

- Current year of study:

- _______________ (enter the year of study, e.g., 2)

- Your average grade during studies:

- _______________ (enter your average grade, e.g., 7.85)

- Name of the place where your family lives:

- _______________ (enter the name of the place)

- Number of household members:

- _______________ (enter the number of members)

- How would you assess your family's material status compared to the average standard of living in the Republic of Serbia?

- ☐ Significantly below average (monthly family income is less than 50,000 RSD; we face financial difficulties, and basic needs are hard to meet)

- ☐ Below average (monthly family income is between 50,000 – 100,000 RSD; we can meet basic needs but have limited resources for additional expenses)

- ☐ Average (monthly family income is between 100,000 – 200,000 RSD; we can afford basic needs and occasional additional expenses)

- ☐ Above average (monthly family income is between 200,000 – 400,000 RSD; we have stable income and can afford a comfortable life)

- ☐ Significantly above average (monthly family income is more than 400,000 RSD; we have a high standard of living and financial security)

- Have you ever participated in activities related to safety before the beginning of student protests/blockades?

- (e.g., volunteer work in civil protection, disaster preparedness training, participation in protests, etc.)?

- ☐ Yes

- ☐ No

- How often did you follow news and information related to safety before the beginning of student protests/blockades?

- ☐ Daily

- ☐ Several times a week

- ☐ Occasionally

- ☐ Rarely or never

- What are your main sources of information on safety topics? (multiple answers possible)

- ☐ Television

- ☐ Online portals and social media

- ☐ Newspapers and magazines

- ☐ Official institutions and press releases

- ☐ Conversations with family and friends

- Since gaining the right to vote, how many times have you voted?

- ☐ I voted in all elections since obtaining the right to vote

- ☐ I voted more often than I skipped elections

- ☐ I voted less often than I skipped elections

- ☐ I voted only once

- ☐ I have not voted yet

- How would you assess the level of corruption today compared to 10 years ago?

- (1 indicates no significant change, 5 indicates that corruption has significantly decreased)

- 1 ☐ Corruption is at the same level as 10 years ago

- 2 ☐ Corruption is only slightly lower than 10 years ago

- 3 ☐ Corruption is somewhat lower than 10 years ago

- 4 ☐ Corruption is significantly lower than 10 years ago

- 5 ☐ Corruption is much lower than 10 years ago

- II. ATTITUDES

- Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

| Attitudes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel safe in my place of residence | |||||

| The level of crime in my area is high | |||||

| The police in my area respond to incidents effectively | |||||

| I avoid certain parts of the city due to feeling unsafe | |||||

| I feel safe walking alone at night | |||||

| I believe that street lighting and surveillance cameras have increased safety | |||||

| I feel safe using public transportation | |||||

| I believe the streets in my area are safe for cyclists and pedestrians | |||||

| People in my community are willing to help in dangerous situations | |||||

| Fear of crime affects my daily life |

- Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

| Attitudes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Demonstrations in Serbia are generally safe for participants | |||||

| The police use excessive force when securing protests | |||||

| Protests are an effective way of expressing civic dissatisfaction | |||||

| The presence of provocateurs often contributes to the escalation of violence during protests | |||||

| I am interested in participating in demonstrations if they advocate for critical social changes | |||||

| I believe that protests are often politically instrumentalized | |||||

| The media report objectively on demonstrations | |||||

| Protesters are often subjected to unfounded pressure by the authorities | |||||

| Citizens should participate in protests more frequently | |||||

| I believe that young people should be more active in socio-political life |

- Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

| Attitudes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Cyberattacks are a serious threat to Serbia’s security | |||||

| Terrorism poses a significant threat to our country | |||||

| Climate change can negatively affect the security of Serbia | |||||

| Global economic instability impacts our national security | |||||

| The spread of disinformation poses a risk to social stability | |||||

| Migration can present a security challenge for Serbia | |||||

| I believe that pandemics are a serious threat to national security | |||||

| Energy dependence on other countries jeopardizes our security | |||||

| Political instability in neighboring countries can affect our security | |||||

| Organized crime represents a serious threat to Serbia |

- Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

| Attitudes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am concerned about the collection of personal data by the government. | |||||

| I believe that surveillance through public space cameras is justified for safety reasons. | |||||

| I feel uncomfortable with companies tracking online activities. | |||||

| I believe it is necessary to strike a balance between privacy and national security. | |||||

| I support the use of biometric data for identification purposes in the interest of security. | |||||

| I believe my personal data is protected online. | |||||

| I am concerned about the potential misuse of my data by third parties. | |||||

| I support the use of surveillance technologies in the fight against crime. | |||||

| I feel that I have control over who has access to my personal information. | |||||

| I believe that data protection laws in Serbia are adequate. |

- Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

| Attitudes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I believe that Serbia is adequately prepared for emergencies | |||||

| I trust the civil protection system in Serbia | |||||

| I know how to respond in the event of a natural disaster | |||||

| I believe that the media are a reliable source of information during crises | |||||

| Public services respond quickly in emergency situations | |||||

| Emergencies such as floods and earthquakes pose a serious risk in Serbia | |||||

| Citizens are sufficiently educated about how to act in crisis situations | |||||

| The disaster early warning system in Serbia is effective | |||||

| I believe that schools and universities are adequately prepared for crisis situations | |||||

| I believe that data protection laws in Serbia are adequate |

- Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

| Attitudes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I trust the work of the police when it comes to protecting citizens | |||||

| The judiciary in Serbia effectively punishes criminals | |||||

| I believe that institutions protect the rights of citizens | |||||

| The government adopts adequate measures to preserve national security | |||||

| Transparency in the work of state institutions is at a high level | |||||

| I believe the state allocates resources for national security properly | |||||

| Political stability directly affects the level of security in the country | |||||

| Serbia’s military power adequately protects its citizens | |||||

| Citizens are sufficiently involved in the creation of security policies | |||||

| The media report objectively on security issues |

References

- Qazi, A.; Akhtar, P. Risk matrix driven supply chain risk management: Adapting risk matrix based tools to modelling interdependent risks and risk appetite. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 105351. [CrossRef]

- Aven, T.; Zio, E. Globalization and global risk: How risk analysis needs to be enhanced to be effective in confronting current threats. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2020, 205, 107270-107270. [CrossRef]

- Haimes, Y. Risk Modeling of Interdependent Complex Systems of Systems: Theory and Practice. Risk Analysis 2018, 38. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A.; Ireland, V. Preparing for complex interdependent risks: a system of systems approach to building disaster resilience. International journal of disaster risk reduction 2014, 9, 181-193. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Johns, A. Youth, social cohesion and digital life: From risk and resilience to a global digital citizenship approach. Journal of Sociology 2020, 57, 394-411. [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Jordan, L.; Hutchinson, A.; De Wet, N. Risky behaviour: a new framework for understanding why young people take risks. Journal of Youth Studies 2018, 21, 324-339. [CrossRef]

- Fabiansson, C. Young People’s Perception Of Being Safe – Globally & Locally. Social Indicators Research 2007, 80, 31-49. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P. The dangerousness of youth-at-risk: the possibilities of surveillance and intervention in uncertain times. Journal of adolescence 2000, 23 4, 463-476. [CrossRef]

- Manwaring, R.; Holloway, J. Resilience to cyber-enabled foreign interference: citizen understanding and threat perceptions. Defence Studies 2022, 23, 334-357. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Maliki, N.Z.B.; Cui, H. Public Perceptions of Resilient Design Characteristics in Urban Form. Sustainability 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gaudenzi, B.; Baldi, B. Cyber resilience in organisations and supply chains: from perceptions to actions. The International Journal of Logistics Management 2024. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Xu, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Ba, Z.; Huang, H. The mediating role of resilience between perceived social support and sense of security in medical staff following the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Grove, K. Security beyond resilience. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2017, 35, 184-194. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, M. Exercising emergencies: Resilience, affect and acting out security. Security Dialogue 2016, 47, 116-199. [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Prager, F.; Rose, A. Transportation security and the role of resilience: A foundation for operational metrics. Transport Policy 2011, 18, 307-317. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Arvai, J. Risk Perception: Reflections on 40 Years of Research. Risk Analysis 2020, 40. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Zwickle, A.; Walpole, H. Developing a Broadly Applicable Measure of Risk Perception. Risk Analysis 2018, 39. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, W.; Avishai, A.; Jones, K.; Villegas, M.; Sheeran, P. When does risk perception predict protection motivation for health threats? A person-by-situation analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Brown, V. Risk Perception: It’s Personal. Environmental Health Perspectives 2014, 122. [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Peters, E. Risk Perception and Affect. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2006, 15, 322-325. [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H. Risk: from perception to social representation. The British journal of social psychology 2003, 42 Pt 1, 55-73. [CrossRef]

- Sjoberg. Factors in risk perception. Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 2000, 20 1, 1-11.

- Bodemer, N.; Gaissmaier, W. Risk perception. Nature 1993, 361, 689-689. [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Leidner, B.; Mercado, E.; Li, M.; Cros, S.; Gómez, A.; Baka, A.; Chekroun, P.; Rottman, J. How safe are we? Introducing the multidimensional model of perceived personal safety. Personality and Individual Differences 2024. [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Le, A.; Adams-Leask, K.; Procter, N. Utilising co-design to develop a lived experience informed personal safety tool within a mental health community rehabilitation setting. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 2024, 71, 1076-1088. [CrossRef]

- Bowen-Forbes, C.; Khondaker, T.; Stafinski, T.; Hadizadeh, M.; Menon, D. Mobile Apps for the Personal Safety of At-Risk Children and Youth: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Grabinska, T. Personal Safety and Security Culture – Similarities and Differences. Security Dimensions 2021. [CrossRef]

- Maria, S.; Artem, M.; Margarita, K.; Irina, K.; Mariam, A. Psychological aspects of personal safety. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Glesner, C.; Geysmans, R.; Turcanu, C. Two sides of the same coin? Exploring the relation between safety and security in high-risk organizations. Journal of safety research 2022, 82, 184-193. [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.; Bieder, C. Safety and Security: The Challenges of Bringing Them Together. The Coupling of Safety and Security 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lisova, E.; Šljivo, I.; Čaušević, A. Safety and Security Co-Analyses: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Systems Journal 2019, 13, 2189-2200. [CrossRef]

- Burns, A.; McDermid, J.; Dobson, J. On the Meaning of Safety and Security. Comput. J. 1992, 35, 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, A.; Böhm, G.; Hayes, A.; O'Connor, R. Credible Threat: Perceptions of Pandemic Coronavirus, Climate Change and the Morality and Management of Global Risks. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.; Snyder, L. The influence of risk perception on safety: A laboratory study. Safety Science 2017, 95, 116-124. [CrossRef]

- McDaniels, T.; Kamlet, M.; Fischer, G. Risk perception and the value of safety. Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 1992, 12 4, 495-503. [CrossRef]

- B, T. THE CONCEPT OF PERSONAL SECURITY IN THE CONTEXT OF THE TRANSFORMATION OF LEGAL RELATIONS IN SOCIETY. Public administration and state security aspects 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tsiuman, T.; Nahula, O. ПСИХОЛОГІЧНА ФОРМУЛА БЕЗПЕКИ ЯК КОНЦЕПТУАЛЬНА ОСНОВА ФОРМУВАННЯ НАВИЧОК БЕЗПЕЧНОЇ ПОВЕДІНКИ ОСОБИСТОСТІ. 2021, 94-100. [CrossRef]

- Panzabekova, A.; Digel, I. PERSONAL SAFETY AS AN INDICATOR OF LIVING STANDARDS. 2020, 3, 60-74. [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A.; Robertson, M.; Ranse, J. Exploring safety at mass gathering events through the lens of three different stakeholders. Frontiers in Public Health 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sułek, K. Integrated Safety Management for Mass Arts and Entertainment Events Based on an Outdoor Concert in Poland: A Case Study. Journal of Public Governance 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Cronin, P.; Agambayev, A.; Ozev, S.; Cetin, A.; Orailoglu, A. A Crowd-Based Explosive Detection System with Two-Level Feedback Sensor Calibration. 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference On Computer Aided Design (ICCAD) 2020, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Sudenis, R. SAFETY OF MASS EVENTS IN INTERNAL SEA WATERS. 2020, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Dorreboom, M.; Barry, K. Concrete, bollards, and fencing: exploring the im/mobilities of security at public events in Brisbane, Australia. Annals of Leisure Research 2020, 25, 48-70. [CrossRef]

- Bukhtoyarov, V.; Dorokhin, S.; Ivannikov, V.; Shvyriov, A.; Yakovlev, K. Safe environment for pedestrians participating in public events. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 918. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yen, N.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Lv, Z.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Mei, L.; Luo, X. Social Sensors Based Online Attention Computing of Public Safety Events. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing 2017, 5, 403-411. [CrossRef]

- Batty, M.; Desyllas, J.; Duxbury, E. Safety in Numbers? Modelling Crowds and Designing Control for the Notting Hill Carnival. Urban Studies 2003, 40, 1573-1590. [CrossRef]

- Mellor, N.; Veno, A. Planning safe public events: practical guidelines. 2002.

- Wen, C.; Liu, W.; He, Z.; Liu, C. Research on emergency management of global public health emergencies driven by digital technology: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Huang, L.; Chen, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Deng, Q.; He, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Key technologies of the emergency platform in China. Journal of Safety Science and Resilience 2022. [CrossRef]

- Benis, A. Social Media and the Internet of Things for Emergency and Disaster Medicine Management. Studies in health technology and informatics 2022, 291, 105-117. [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Roberts, P.; Rhodes, M. The Ecology of Emergency Management Work in the Digital Age. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 2020, 3, 305-322. [CrossRef]

- Mirbabaie, M.; Ehnis, C.; Stieglitz, S.; Bunker, D.; Rose, T. Digital Nudging in Social Media Disaster Communication. Information Systems Frontiers 2020, 23, 1097-1113. [CrossRef]

- Krausz, M.; Westenberg, J.; Vigo, D.; Spence, R.; Ramsey, D. Emergency Response to COVID-19 in Canada: Platform Development and Implementation for eHealth in Crisis Management. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 2020, 6. [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Chan, F.; Jin, J.; Barry, T. The effects of efficacy framing in news information and health anxiety on coronavirus-disease-2019-related cognitive outcomes and interpretation bias. Journal of experimental psychology. General 2022. [CrossRef]

- Heiss, R.; Gell, S.; Röthlingshöfer, E.; Zoller, C. How threat perceptions relate to learning and conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19: Evidence from a panel study. Personality and Individual Differences 2021, 175, 110672-110672. [CrossRef]

- Shesterinina, A. Collective Threat Framing and Mobilization in Civil War. American Political Science Review 2016, 110, 411-427. [CrossRef]

- Huddy, L.; Feldman, S.; Taber, C.; Lahav, G. Threat, Anxiety, and Support of Antiterrorism Policies. American Journal of Political Science 2005, 49, 593-608. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, X. Risk perception and risky choice: Situational, informational and dispositional effects. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 2003, 6, 117-132. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Renner, R.; Jakovljević, V. Industrial Disasters and Hazards: From Causes to Conse-quences—A Holistic Approach to Resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 149-168.

- Cvetković, V.M.; Gole, S.; Renner, R.; Jakovljević, V.; Lukić, T. Qualitative insights into cultural heritage protection in Serbia: Addressing legal and institutional gaps for disaster risk resilience. Open Geosciences 2024, 16, 20220755.

- Cvetković, V.; Tanasić, J.; Renner, R.; Rokvić, V.; Beriša, H. Comprehensive Risk Analysis of Emergency Medical Response Systems in Serbian Healthcare: Assessing Systemic Vulnerabilities in Disaster Preparedness and Response. In Proceedings of the Healthcare, 2024; p. 1962.

- Cvetković, V.; Šišović, V. Understanding the Sustainable Development of Community (Social) Disaster Resilience in Serbia: Demographic and Socio-Economic Impacts. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2620.

- Cvetković, V.; Renner, R.; Aleksova, B.; Lukić, T. Geospatial and Temporal Patterns of Natural and Man-Made (Technological) Disasters (1900–2024): Insights from Different Socio-Economic and Demographic Perspectives. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 8129.

- Cvetković, V.; Noji, E.; Filipović, M.; Marija, M.P.; Želimir, K.; Nenad, R. Public Risk Perspectives Regarding the Threat of Terrorism in Belgrade: Implications for Risk Management Decision-Making for Individuals, Communities and Public Authorities. Journal of Criminal Investigation and Criminology/Revija za kriminalistiko in kriminologijo 2018, 69, 279–298.

- Kondratenko, N.; Dobryanskyy, O. The Determination of National Threats as a Prerequisite for the Formation of an Integrated System of Economic Security at the National Level. THE PROBLEMS OF ECONOMY 2023. [CrossRef]

- Khaustova, V.; Trushkina, N. Risks and Threats to National Security: Essence and Classification. Business Inform 2024. [CrossRef]

- Falandys, K.; Łabuz, P.; Barć, M. REPRIVATISATION, FUEL TRADING AND ISLAMIC IMMIGRANTS AS THREE LEVELS OF THREATS TO NATIONAL SECURITY. PRZEGLĄD POLICYJNY 2019. [CrossRef]

- Allahrakha, N. Balancing Cyber-security and Privacy: Legal and Ethical Considerations in the Digital Age. Legal Issues in the Digital Age 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sahi, A.M.; Khalid, H.; Abbas, A.; Zedan, K.; Khatib, S.; Amosh, H.A. The Research Trend of Security and Privacy in Digital Payment. Informatics 2022, 9, 32. [CrossRef]

- Sule, M.-J.; Zennaro, M.; Thomas, G. Cybersecurity through the lens of Digital Identity and Data Protection: Issues and Trends. Technology in Society 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P. Security and privacy protection in cloud computing: Discussions and challenges. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 160, 102642. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Urbano, A. Security in digital markets. Journal of Business Research 2019. [CrossRef]

- Toch, E.; Bettini, C.; Shmueli, E.; Radaelli, L.; Lanzi, A.; Riboni, D.; Lepri, B. The Privacy Implications of Cyber Security Systems. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Bazarkina, D.; Pashentsev, E. Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence. Russia in Global Affairs 2020. [CrossRef]

- Milošević, G.; Cvjetković-Ivetić, C.; Baturan, L. State Aid in Reconstruction of Natural and Other Disasters’ Consequences Using the Budget Funds of the Republic of Serbia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 169-182.

- Milenković, D.; Cvetković, V.M.; Renner, R. A Systematic Literary Review on Community Resilience Indicators: Adaptation and Application of the BRIC Method for Measuring Disasters Resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 79-104.

- Beriša, H.; Cvetković, V.; Pavić, A. Implications of Artificial Intelligence and Cyberspace on Risk Management Capabilities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 279-295.

- Cruz, R.D.D.; Ormilla, R.C.G. Disaster Risk Reduction Management Implementation in the Public Elementary Schools of the Department of Education, Philippines. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2022, 4, 1-15.

- Bashlueva, M.; Kartashov, I. TERRORISM AS ONE OF THE MAIN THREATS TO NATIONAL SECURITY. Lobbying in the Legislative Process 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.S.M.; Xu, X. Topical Dynamics of Terrorism from a Global Perspective and A Call for Action on Global Risk. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lepskiy, M.; Lepska, N. The Phenomenon of the Terrorist State in Contemporary Geopolitics: Attributive, Static, and Dynamic Characteristics. American Behavioral Scientist 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alwan, H.A.S.I.H. The impact of terrorism on government performance after 2014 (future vision). Russian Law Journal 2023. [CrossRef]

- Borichev, K.; Pavlik, M. The role of State Security bodies in countering terrorism. 2021, 2021, 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Ervine, P. Does Terrorism Pose a Real Threat to Security? 2020.

- Hendrix, C.; Young, J. State Capacity and Terrorism: A Two-Dimensional Approach. Security Studies 2014, 23, 329-363. [CrossRef]

- Ekmekçi, F. Terrorism as war by other means: national security and state support for terrorism. Revista Brasileira De Politica Internacional 2011, 54, 125-141. [CrossRef]

- Van Munster, R. The War on Terrorism: When the Exception Becomes the Rule. International journal for the semiotics of law 2004, 17, 141-153. [CrossRef]

- Yarovenko, H. Evaluating the threat to national information security. Problems and Perspectives in Management 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. Are they psychologically prepared? Examining psychological preparedness for disasters among frontline civil servants in Taiwan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ikican, T.Ç.; Bayındır, G.Ş.; Engin, Y.; Albal, E. Disaster preparedness perceptions and psychological first-aid competencies of psychiatric nurses. International nursing review 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abualenain, J. Psychological preparedness in disaster management: A survey of leaders in Saudi Arabia's emergency operation centers. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.; Kelly, L.; Mackay, A. Australian Red Cross psychosocial approach to disaster preparedness. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 2023. [CrossRef]

- Said, N.; Molassiotis, A.; Chiang, V. Psychological first aid training in disaster preparedness for nurses working with emergencies and traumas. International nursing review 2022. [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Marques, M.; Every, D. Conceptualising and measuring psychological preparedness for disaster: The Psychological Preparedness for Disaster Threat Scale. Natural Hazards 2020, 101, 297-307. [CrossRef]

- Paton, D. Disaster risk reduction: Psychological perspectives on preparedness. Australian Journal of Psychology 2019, 71, 327-341. [CrossRef]

- Sergey, K. Methodology for Building Automated Systems for Monitoring Engineering (Load-Bearing) Structures, and Natural Hazards to Ensure Comprehensive Safety of Buildings and Constructions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2021, 3, 1-10.

- El-Mougher, M.M.; Mahfuth, K. Indicators of Risk Assessment and Management in Infrastructure Projects in Palestine. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2021, 3, 23-40.

- Dukiya, J.J.; Benjamine, O. Building resilience through local and international partnerships, Nigeria experiences. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2021, 3, 11-24.

- Adamović, M.; Milojević, S.; Nikolovski, S.; Knežević, S. Pharmacy response to natural disasters. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management (IJDRM) 2021, 3, 25-30.

- Olawuni, P.; Olowoporoku, O.; Daramola, O. Determinants of Residents’ Participation in Disaster Risk Management in Lagos Metropolis Nigeria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2, 1-18.

- Chakma, U.K.; Hossain, A.; Islam, K.; Hasnat, G.T.; Kabir. Water crisis and adaptation strategies by tribal community: A case study in Baghaichari Upazila of Rangamati District in Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2, 37-46.

- Xuesong, G.; Kapucu, N. Examining Stakeholder Participation in Social Stability Risk Assessment for Mega Projects using Network Analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 1-31.

- Vibhas, S.; Adu, G.B.; Ruiyi, Z.; Anwaar, M.A.; Rajib, S. Understanding the barriers restraining effective operation of flood early warning systems. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 1-17.

- Kumiko, F.; Shaw, R. Preparing International Joint Project: Use of Japanese Flood Hazard Map in Bangladesh. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 62-80.

- Aktar, M.A.; Shohani, K.; Hasan, M.N.; Hasan, M.K. Flood Vulnerability Assessment by Flood Vulnerability Index (FVI) Method: A Study on Sirajganj Sadar Upazila. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2021, 3, 1-14.

- Al-ramlawi, A.; El-Mougher, M.; Al-Agha, M. The Role of Al-Shifa Medical Complex Administration in Evacuation & Sheltering Planning. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2.

- Carla S, R.G. School-community collaboration: disaster preparedness towards building resilient communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 45-59.

- Chakma, S. Water Crisis in the Rangamati Hill District of Bangladesh: A Case Study on Indigenous Community. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2023, 5, 29-44.

- Cvetković, V. Risk Perception of Building Fires in Belgrade. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 81-91.

- Cvetković, V. A Predictive Model of Community Disaster Resilience based on Social Identity Influences (MODERSI). International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2023, 5, 57-80.

- El-Mougher, M.M. Level of coordination between the humanitarian and governmental organizations in Gaza Strip and its impact on the humanitarian interventions to the Internally Displaced People (IDPs) following May escalation 2021. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2022, 4, 15-45.

- Ivanov, A. Disaster Risk Reduction and Disaster Risk Management: State of Play in North Macedonia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 201-212.

- Kaur, B. Disasters and exemplified vulnerabilities in a cramped Public Health Infrastructure in India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2020, 2, 15-22.

- Mano, R.; A, K.; Rapaport, C. Earthquake preparedness: A Social Media Fit perspective to accessing and disseminating earthquake information. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2019, 1, 19-31.

- Molnár, A. A Systematic Collaboration of Volunteer and Professional Fire Units in Hungary. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 1-13.

- Rajani, A.; Tuhin, R.; Rina, A. The Challenges of Women in Post-disaster Health Management: A Study in Khulna District. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2023, 5, 51-66.

- Adams, R. Disabilities and Disasters: How Social Cognitive and Community Factors Influence Preparedness among People with Disabilities. 2018.

- Ainuddin, S.; Routray, J.K. Institutional framework, key stakeholders and community preparedness for earthquake induced disaster management in Balochistan. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2012, 21, 22-36.

- Brown, B.J. Disaster preparedness and the United Nations: advance planning for disaster relief; Elsevier: 2013.

- Cretikos, M.; Eastwood, K.; Dalton, C.; Merritt, T.; Tuyl, F.; Winn, L.; Durrheim, D. Household disaster preparedness and information sources: Rapid cluster survey after a storm in New South Wales, Australia. BMC public health 2008, 8, 195.

- Alexander, D. Disaster and Crisis Preparedness. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Response. 2019, 63-92. [CrossRef]

- Ardiansyah, M.; Mirandah, E.; Suyatno, A.; Saputra, F.; Muazzinah, M. Disaster Management and Emergency Response: Improving Coordination and Preparedness. Global International Journal of Innovative Research 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kuehnhanss, C.; Nohlen, H. A scenario study on disaster preparedness behaviours. The European Journal of Public Health 2024, 34. [CrossRef]

- Marceta, Ž.; Jurišic, D. Psychological Preparedness of the Rescuers and Volunteers: A Case Study of 2023 Türkiye Earthquake. International Journal of Disaster Risk Management 2024, 6, 27-40.

- Samimian-Darash, L.; Rotem, N. From Crisis to Emergency: The Shifting Logic of Preparedness. Ethnos 2018, 84, 910-926. [CrossRef]

- Leider, J.; DeBruin, D.; Reynolds, N.; Koch, A.; Seaberg, J. Ethical Guidance for Disaster Response, Specifically Around Crisis Standards of Care: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Public Health 2017, 107. [CrossRef]

- Hanfling, D.; Altevogt, B.; Viswanathan, K.; Gostin, L. Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response. Military medicine 2016, 181 8, 719-721. [CrossRef]

- Goel, P. Crisis Management Strategies: Preparing for and Responding to Disruptions. Journal of Advanced Management Studies 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V. Disaster Risk Management. Scientific-Professional Society for Disaster Risk Management, Belgrade 2024.

- News, A. Serbian students demand justice after deadly train station collapse. 2024.

- News, A. Protests grow in Serbia after deadly infrastructure failure. 2024.

- Newton, K.; Norris, P. Confidence in public institutions: faith, culture, or performance? Disaffected democracies: What’s troubling the trilateral countries 2000, 52, 73.

- Anđić, T. Futurelessness, migration, or a lucky break: narrative tropes of the ‘blocked future’ among Serbian high school students. Journal of Youth Studies 2020, 23, 430-446. [CrossRef]

- Ilišin, V.; Gvozdanović, A.; Potočnik, D. Contradictory tendencies in the political culture of Croatian youth: unexpected anomalies or an expected answer to the social crisis? Journal of Youth Studies 2018, 21, 51-71. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, S.; May, D.; Lambert, E.; Keena, L. An Examination of the Effects of Personal and Workplace Variables on Correctional Staff Perceptions of Safety. American Journal of Criminal Justice 2020, 45, 145-165. [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Ahmad, F.; Morr, C.E.; Ritvo, P. Perceived impact of contextual determinants on depression, anxiety and stress: a survey with university students. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Allik, M.; Kearns, A. “There goes the fear”: feelings of safety at home and in the neighborhood: The role of personal, social, and service factors. Journal of Community Psychology 2017, 45, 543-563. [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Austin, D. Neighborhood Environmental Satisfaction, Victimization, and Social Participation as Determinants of Perceived Neighborhood Safety. Environment and Behavior 1989, 21, 763-780. [CrossRef]

- Eisch-Angus, K. Crime and Narration: The Creation of (In)Security in Everyday Life. 2020, 87-112. [CrossRef]

- Valera, S.; Guàrdia, J. Perceived insecurity and fear of crime in a city with low-crime rates. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2014, 38, 195-205. [CrossRef]

- Roznai, Y. The Insecurity of Human Security. 2014.

- Moreno, F.; Dennis, S.H.; Cummings, E.; Boxer, P. “When someone is in a safe place, I believe that your mind rests” emotional security amid community violence: A cross-national study with youth in Newark, New Jersey, USA, and San Pedro Sula, Cortés, Honduras. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 2024. [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Burgess, L.; Sellars, E.; Crooks, J.; McGowan, R.; Diffey, J.; Naughton, G.; Carrington, R.; Lovelock, C.; Temple, R.; et al. A qualitative study exploring the benefits of involving young people in mental health research. Health Expectations : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 2023, 26, 1491-1504. [CrossRef]

- Vilchez, M.; Trujillo, F. The Perception of Security and Youth: A Practical Example. Social Sciences 2023. [CrossRef]

- Slaatto, A.; Mellblom, A.; Kleppe, L.; Baugerud, G. Safety in Residential Youth Facilities: Staff Perceptions of Safety and Experiences of the “Basic Training Program in Safety and Security”. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth 2021, 39, 212-237. [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.; Beardslee, J.; Mays, R.; Frick, P.; Steinberg, L.; Cauffman, E. Measuring youths’ perceptions of police: Evidence from the crossroads study. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.; Padilla, K.; Tom, K. Police legitimacy: identifying developmental trends and whether youths’ perceptions can be changed. Journal of Experimental Criminology 2020, 18, 67-87. [CrossRef]

- Azmy, A. Police studies program for at-risk youth in youth villages: program evaluation and understanding the psychological mechanism behind participation in the program and perceptions towards police legitimacy. Police Practice and Research 2020, 22, 640-656. [CrossRef]

- Wardle, H. Perceptions, people and place: Findings from a rapid review of qualitative research on youth gambling. Addictive behaviors 2018, 90, 99-106. [CrossRef]

- Heller, S.; Shah, A.; Guryan, J.; Ludwig, J.; Mullainathan, S.; Pollack, H. Thinking, Fast and Slow? Some Field Experiments to Reduce Crime and Dropout in Chicago*. 2015, 132, 1-54. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C.; Mulvey, E.; Loughran, T.; Losoya, S. Perceptions of Institutional Experience and Community Outcomes for Serious Adolescent Offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior 2012, 39, 71-93. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-H.; Gan, J.; Yi, Z.; Qu, X.; Ran, B. Risk perception and the warning strategy based on safety potential field theory. Accident; analysis and prevention 2020, 148, 105805. [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Wang, X.; Griffin, M.; Wu, C.; Liu, B. Do we see how they perceive risk? An integrated analysis of risk perception and its effect on workplace safety behavior. Accident; analysis and prevention 2017, 106, 234-242. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Wiley, K.; Gianotti, A. Risk Perception in a Multi-Hazard Environment. World Development 2017, 97, 138-152. [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M. The Problem of Institutional Trust. Organization Studies 2023, 44, 308-310. [CrossRef]

- Fiket, I.; Pudar-Drasko, G. Possibility of non-institutional political participation within the non-responsive system of Serbia: The impact of (dis)trust and internal political efficiency. Sociologija 2021. [CrossRef]

- Džunić, M.; Golubovic, N.; Marinkovic, S. Determinants of institutional trust in transition economies: Lessons from Serbia. Ekonomski anali 2020. [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, I. Individual-Level Evidence on the Causal Relationship Between Social Trust and Institutional Trust. Social Indicators Research 2018, 144, 275-298. [CrossRef]

- Kroeger, F. Trusting organizations: The institutionalization of trust in interorganizational relationships. Organization 2012, 19, 743-763. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B.; Stolle, D. The State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust. Comparative politics 2008, 40, 441-459. [CrossRef]

- Pjesivac, I.; Spasovska, K.; Imre, I. The Truth Between the Lines: Conceptualization of Trust in News Media in Serbia, Macedonia, and Croatia. Mass Communication and Society 2016, 19, 323-351. [CrossRef]

- Heath, L.; Gilbert, K. Mass Media and Fear of Crime. American Behavioral Scientist 1996, 39, 379-386. [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.; Nikolić, N.; Lukić, T. Exploring Students' and Teachers' Insights on School-Based Disaster Risk Reduction and Safety: A Case Study of Western Morava Basin, Serbia. Safety 2024, 10, 2024040472.

- Zyla, B. Human Security. International Relations 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sokołowski, M. The concept and the essence of personal security. Kultura Bezpieczeństwa. Nauka – Praktyka - Refleksje 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kotovchevski, M.; Kotovchevska, B. National and Human Security Concept. 2017, 20, 319-325.

- Gasper, D.; Gómez, O. Human security thinking in practice: ‘personal security’, ‘citizen security' and comprehensive mappings. Contemporary Politics 2015, 21, 100-116. [CrossRef]

- Schutte, R.; Fordelone, T.Y. Human Security: a paradigm contradicting the national interest? 2006, 1, 35-40.

- Newman, E. Human Security and Constructivism. International Studies Perspectives 2001, 2, 239-251. [CrossRef]

- Wildavsky, A.; Dake, K. Theories of Risk Perception: Who Fears What and Why? 2016.

- Ferrer, R.; Klein, W. Risk perceptions and health behavior. Current opinion in psychology 2015, 5, 85-89. [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S.; Brown, S. Perceptions of risk. International Review of Victimology 2013, 19, 249-267. [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. Factors in Risk Perception. Risk Analysis 2000, 20. [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. Worry and Risk Perception. Risk Analysis 1998, 18. [CrossRef]

- Pollatsek, A.; Tversky, A. A theory of risk. Journal of Mathematical Psychology 1970, 7, 540-553. [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.; Gefen, D. Building Effective Online Marketplaces with Institution-Based Trust. Fox School of Business 2004. [CrossRef]

- Bošković, M.M.; Kostić, J. Track Record in Fight Against Corruption in Serbia – How to Increase Effectiveness of Prosecution? Journal of the University of Latvia. Law 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, K.; Petrović, V. Organized crime in Serbian politics during the Yugoslav wars. Journal of Political Power 2022, 15, 101-122. [CrossRef]

- Čvorović, D. Suppression of organized crime and Serbia's accession to the European Union. Bezbednost, Beograd 2022. [CrossRef]

- Obokata, T.; Bošković, A.; Radović, N. Serbia’s Action against Transnational Organised Crime. European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 2016, 24, 151-175. [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Guedes, I. The Role of the Media in the Fear of Crime: A Qualitative Study in the Portuguese Context. Criminal Justice Review 2022, 48, 300-317. [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, G.; Di Marco, M.H.; Russ, T.; Dibben, C.; Pearce, J. The impact of neighbourhood crime on mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social science & medicine 2021, 282, 114106. [CrossRef]

- Baranauskas, A. War Zones and Depraved Violence: Exploring the Framing of Urban Neighborhoods in News Reports of Violent Crime. Criminal Justice Review 2020, 45, 393-412. [CrossRef]

- Kort-Butler, L.; Habecker, P. Framing and Cultivating the Story of Crime. Criminal Justice Review 2018, 43, 127-146. [CrossRef]

- Leverentz, A. Narratives of Crime and Criminals: How Places Socially Construct the Crime Problem1. Sociological Forum 2012, 27, 348-371. [CrossRef]

- Callanan, V. Media Consumption, Perceptions of Crime Risk and Fear of Crime: Examining Race/Ethnic Differences. Sociological Perspectives 2012, 55, 115-193. [CrossRef]

- Gross, K.; Aday, S. The Scary World in Your Living Room and Neighborhood: Using Local Broadcast News, Neighborhood Crime Rates, and Personal Experience to Test Agenda Setting and Cultivation. Journal of Communication 2003, 53, 411-426. [CrossRef]

- Mravcová, A. Environmental Sustainability under the Impact of the Current Crises. Studia Ecologiae et Bioethicae 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kryshtal, H.; Briukhovetska, I.; Khimich, S. State and Business in Financing the Goals of Sustainable Development. „Sustainable Development: Modern Trends and Challenges“ 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Matiiuk, Y.; Krikštolaitis, R. The concern about main crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and climate change's impact on energy-saving behavior. Energy Policy 2023. [CrossRef]

- Grum, B.; Grum, D.K. Urban Resilience and Sustainability in the Perspective of Global Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic and War in Ukraine: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Faura, J. Ukraine's post-war reconstruction: Building smart cities and governments through a sustainability-based reconstruction plan. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z. Research on the balance strategy between privacy protection and crime control in the deployment of urban surveillance technology. Science of Law Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, K.; Dalipi, F. Exploring the surveillance technology discourse: a bibliometric analysis and topic modeling approach. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2024, 7. [CrossRef]

- Sung, C.-S.; Park, J.-Y. Design of an intelligent video surveillance system for crime prevention: applying deep learning technology. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 34297-34309. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Surveillance Threating Privacy and Data Protection: A Review. 2018, 8, 20583-20590.

- Prastyanti*, R.; Sharma, R. Establishing Consumer Trust Through Data Protection Law as a Competitive Advantage in Indonesia and India. Journal of Human Rights, Culture and Legal System 2024. [CrossRef]

- Popović, D. The Pivotal Role of DPAs in Digital Privacy Protection : Assessment of the Serbian Protection Mechanism. Law, Identity and Values 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, M. Freedom of expression and protection of personal data on the Internet: The perspective of Internet users in Serbia. 2020, 15, 5-34. [CrossRef]

- Bogosavljević, M. Protection of Personal Data in Documents: Application of the Law on Personal Data Protection in Serbia and Abroad. Moderna arhivistika 2019. [CrossRef]

- Šuvaković, U.; Petrović, J.; Nikolić, I. Confessional Instruction or Religious Education: Attitudes of Female Students at the Teacher Education Faculties in Serbia. Religions 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, V.; Vukić, T.; Maletaski, T.; Andevski, M. Students’ attitudes towards sustainable development in Serbia. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2020, 21, 733-755. [CrossRef]

- Pjesivac, I.; Imre, I. Perceptions of Media Roles in Serbia and Croatia: Does News Orientation Have an Impact? Journalism Studies 2018, 20, 1864-1882. [CrossRef]

- Reinprecht, A.-M. Between Europe and the Past—Collective Identification and Diffusion of Student Contention to and from Serbia. Europe-Asia Studies 2017, 69, 1362-1382. [CrossRef]

- Angluin, D.; Scapens, R. Transparency, accounting knowledge and perceived fairness in UK universities. Resource allocation: results from a survey of accounting and finance. British Accounting Review 2000, 32, 1-42. [CrossRef]

- Tmušič, M. Misuse of institutions and economic performance: some evidence from Serbia. Post-Communist Economies 2023, 35, 546-573. [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, V. Trust and subjective well-being: The case of Serbia. Personality and Individual Differences 2016, 98, 284-288. [CrossRef]

- Debb, S.; McClellan, M. Perceived Vulnerability As a Determinant of Increased Risk for Cybersecurity Risk Behavior. Cyberpsychology, behavior and social networking 2021, 24 9, 605-611. [CrossRef]

- Schaik, P.; Jeske, D.; Onibokun, J.; Coventry, L.; Jansen, J.; Kusev, P. Risk perceptions of cyber-security and precautionary behaviour. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 547-559. [CrossRef]

- Aven, T. A risk science perspective on the discussion concerning Safety I, Safety II and Safety III. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 217, 108077. [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, T.; Airo, K.; Jylhä, T. Safety training needs of educational institutions. Quality Assurance in Education 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khankeh, H.; Pourebrahimi, M.; Karibozorg, M.; Hosseinabadi-Farahani, M.; Ranjbar, M.; Ghods, M.; Saatchi, M. Public trust, preparedness, and the influencing factors regarding COVID-19 pandemic situation in Iran: A population-based cross-sectional study. Asian Journal of Social Health and Behavior 2022, 5, 154-161. [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, J.; Stanković, B.; Žeželj, I. When Our History Meets Their History: Strategies Young People in Serbia Use to Coordinate Conflicting Group Narratives. European Journal of Social Psychology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zorkić, T.J.; Mićić, K.; Cerović, T.K. Lost Trust? The Experiences of Teachers and Students during Schooling Disrupted by the Covid-19 Pandemic. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal 2021. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 180 | 45 |

| Female | 220 | 55 | |

| Age | ≤20 | 57 | 14.04 |

| 21−23 | 134 | 33.00 | |

| 24−26 | 164 | 40.39 | |

| ≥27 | 51 | 12.56 | |

| Place of study | Belgrade | 215 | 52.96 |

| Novi Sad | 125 | 30.79 | |

| Kragujevac | 66 | 16.26 | |

| Study year | First | 84 | 20.59 |

| Second | 137 | 33.58 | |

| Third | 148 | 36.27 | |

| Fourth | 39 | 9.56 | |

| Type of attending institution | Public | 345 | 84.98 |

| Private | 61 | 15.02 | |

| Faculty (Field of Science) | Technical-technological sciences | 90 | 21.95 |

| Natural and mathematical sciences | 10 | 2.44 | |

| Medical sciences | 50 | 12.20 | |

| Social and humanistic sciences | 260 | 63.41 | |

| Current level of studies | Undergraduate academic studies | 311 | 76.60 |

| Master’s academic studies | 80 | 19.70 | |

| Doctoral studies | 15 | 3.69 | |

| Average grade during studies | 6.00−7.00 | 60 | 14.78 |

| 7.00−8.00 | 144 | 35.47 | |

| 8.00−9.00 | 130 | 32.02 | |

| 9.00−10.00 | 72 | 17.73 | |

| Number of household members | ≤2 | 42 | 10.53 |

| 3−4 | 243 | 60.90 | |

| ≥5 | 114 | 28.57 | |

| The family's material status | Significantly below average (≤500 EUR) | 67 | 16.14 |

| Below average (500−1000 EUR) | 106 | 25.54 | |

| Average (1001−2000 EUR) | 222 | 53.49 | |

| Above average (2001−4000 EUR) | 20 | 4.82 | |

| Participated in activities related to safety | Yes | 137 | 34.34 |

| No | 262 | 65.66 | |

| Sources of information on safety topics | Television | 131 | 19.6 |

| Online portals and social media | 222 | 33.2 | |

| Newspapers and magazines | 25 | 3.7 | |

| Official institutions and press releases | 108 | 16.1 | |

| Conversations with family and friends | 183 | 27.4 | |

| Frequencies of following safety news | Daily | 90 | 22.17 |

| Several times a week | 69 | 17.00 | |

| Occasionally | 170 | 41.87 | |

| Rarely or never | 77 | 18.97 | |

| Frequency of vote | Voted more often than abstained | 56 | 13.93 |

| Voted in all elections since obtaining the right | 246 | 61.19 | |

| Voted only once despite having multiple opportunities | 31 | 7.71 | |

| Have never voted | 35 | 8.71 | |

| Voted and abstained equally often | 34 | 8.46 | |

| Attitudes | М | SD |

|---|---|---|

| I feel safe in my place of residence | 3.30 | 1.28 |

| The level of crime in my area is high | 2.65 | 1.15 |

| The police in my area respond to incidents effectively | 3.17 | 1.52 |

| I avoid certain parts of the city due to feeling unsafe | 2.68 | 1.42 |

| I feel safe walking alone at night | 2.91 | 1.38 |

| I believe that street lighting and surveillance cameras have increased safety | 2.78 | 1.30 |

| I feel safe using public transportation | 2.86 | 1.32 |

| I believe the streets in my area are safe for cyclists and pedestrians | 3.13 | 1.07 |

| People in my community are willing to help in dangerous situations | 2.29 | 1.25 |

| Fear of crime affects my daily life | 3.32 | 1.28 |

| Total | 2.91 | 1.30 |

| Attitudes | М | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Demonstrations in Serbia are generally safe for participants | 2.87 | 1.24 |

| The police use excessive force when securing protests | 3.06 | 1.23 |

| Protests are an effective way of expressing civic dissatisfaction | 4.26 | 1.09 |

| The presence of provocateurs often contributes to the escalation of violence during protests | 4.31 | 0.98 |

| I am interested in participating in demonstrations if they advocate for critical social changes | 4.51 | 0.99 |

| I believe that protests are often politically instrumentalized | 3.82 | 1.05 |

| The media report objectively on demonstrations | 1.62 | 0.95 |

| Protesters are often subjected to unfounded pressure by the authorities | 4.23 | 1.02 |

| Citizens should participate in protests more frequently | 4.45 | 0.99 |

| I believe that young people should be more active in socio-political life | 4.50 | 0.88 |

| Total | 3.76 | 1.04 |

| Attitudes | М | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Cyberattacks are a serious threat to Serbia’s security | 4.01 | 1.07 |

| Terrorism poses a significant threat to our country | 3.35 | 1.30 |

| Climate change can negatively affect the security of Serbia | 3.83 | 1.26 |

| Global economic instability impacts our national security | 4.15 | 0.92 |

| The spread of disinformation poses a risk to social stability | 4.64 | 0.65 |

| Migration can present a security challenge for Serbia | 4.11 | 1.01 |

| I believe that pandemics are a serious threat to national security | 3.94 | 1.12 |

| Energy dependence on other countries jeopardizes our security | 4.26 | 0.88 |

| Political instability in neighboring countries can affect our security | 3.84 | 1.01 |

| Organized crime represents a serious threat to Serbia | 4.75 | 0.58 |

| Total | 4.19 | 0.98 |

| Attitudes | М | SD |

|---|---|---|

| I am concerned about the collection of personal data by the government. | 3.81 | 1.21 |

| I believe that surveillance through public space cameras is justified for safety reasons. | 3.88 | 1.11 |

| I feel uncomfortable with companies tracking online activities. | 3.69 | 1.21 |

| I believe it is necessary to strike a balance between privacy and national security. | 4.20 | 0.93 |

| I support the use of biometric data for identification purposes in the interest of security. | 3.55 | 1.14 |

| I believe my personal data is protected online. | 2.20 | 1.16 |

| I am concerned about the potential misuse of my data by third parties. | 3.75 | 1.21 |

| I support the use of surveillance technologies in the fight against crime. | 4.25 | 0.88 |

| I feel that I have control over who has access to my personal information. | 2.54 | 1.29 |

| I believe that data protection laws in Serbia are adequate. | 2.52 | 1.10 |

| Attitudes | М | SD |

|---|---|---|

| I believe that Serbia is adequately prepared for emergencies | 1.95 | 1.00 |

| I trust the civil protection system in Serbia | 2.13 | 1.10 |

| I know how to respond in the event of a natural disaster | 2.96 | 1.26 |

| I believe that the media are a reliable source of information during crises | 1.89 | 1.06 |

| Public services respond quickly in emergency situations | 2.44 | 1.17 |

| Emergencies such as floods and earthquakes pose a serious risk in Serbia | 3.90 | 1.11 |

| Citizens are sufficiently educated about how to act in crisis situations | 1.68 | 0.88 |

| The disaster early warning system in Serbia is effective | 2.15 | 1.12 |

| I believe that schools and universities are adequately prepared for crisis situations | 2.01 | 1.03 |

| I believe that data protection laws in Serbia are adequate | 2.21 | 1.08 |

| Total | 2.43 | 1.08 |

| Attitudes | М | SD |

|---|---|---|

| I trust the work of the police when it comes to protecting citizens | 2.21 | 1.18 |

| The judiciary in Serbia effectively punishes criminals | 1.60 | 0.90 |

| I believe that institutions protect the rights of citizens | 1.77 | 0.97 |

| The government adopts adequate measures to preserve national security | 1.81 | 1.00 |

| Transparency in the work of state institutions is at a high level | 1.44 | 0.83 |

| I believe the state allocates resources for national security properly | 1.70 | 0.97 |

| Political stability directly affects the level of security in the country | 4.07 | 1.24 |

| Serbia’s military power adequately protects its citizens | 2.43 | 1.13 |

| Citizens are sufficiently involved in the creation of security policies | 1.78 | 0.96 |

| The media report objectively on security issues | 2.21 | 1.18 |

| Total | 2.30 | 1.04 |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

df | Male M (SD) |

Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions of personal safety | 1.06 | 2.49 | 0.01** | 397 | 2.97 (0.53) | 2.72 (0.50) |

| 2. Perceptions of safety at public events and demonstrations | 1.39 | –0.91 | 0.36 | 397 | 3.72 (0.55) | 3.77 (0.49) |

| 3. Perceptions of national-level threats | 1.66 | –1.50 | 0.13 | 397 | 4.01 (0.62) | 4.11 (0.57) |

| 4. Perceptions of digital security and privacy | 1.51 | –1.71 | 0.08 | 397 | 3.36 (0.52) | 3.46 (0.49) |

| 5. Perceptions of disaster preparedness and crisis response | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.72 | 397 | 2.35 (0.70) | 2.32 (0.65) |

| 6. Perceptions of institutional confidence and trust in security policy | 0.158 | 0.176 | 0.86 | 397 | 2.02 (0.72) | 2.01 (0.67) |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) | df | Male M (SD) | Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel safe in my place of residence | 0.58 | 2.92 | 0.00** | 398 | 4.07 (1.11) | 3.70 (1.11) |

| The level of crime in my area is high | 2.47 | –2.67 | 0.00** | 397 | 3.00 (1.25) | 3.40 (1.28) |

| The police in my area respond | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.73 | 397 | 2.66 (1.14) | 2.62 (1.14) |

| I avoid certain parts of the city due to feeling unsafe | 0.09 | –4.05 | 0.00** | 397 | 2.62 (1.48) | 3.33 (1.51) |

| I feel safe walking alone at night | 0.10 | 7.65 | 0.00** | 397 | 3.58 (1.34) | 2.40 (1.33) |

| I believe that street lighting and surveillance | 0.61 | 2.18 | 0.03* | 397 | 3.17 (1.42) | 2.82 (1.37) |

| I feel safe using public transportation | 1.51 | 7.07 | 0.00** | 397 | 3.55 (1.31) | 2.54 (1.20) |

| I believe the streets in my area are safe | 2.63 | 1.24 | 0.21 | 397 | 3.01 (1.41) | 2.82 (1.29) |

| People in my community are willing | 1.67 | 0.27 | 0.78 | 397 | 3.15 (1.12) | 3.12 (1.06) |

| Fear of crime affects my daily life | 1.07 | –2.62 | 0.00** | 397 | 1.99 (1.24) | 2.37 (1.24) |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

df | Male M (SD) |

Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions of personal safety | 0.095 | -0.415 | 0.679 | 397 | 2.86 (0.51) | 2.90 (0.52) |

| 2. Perceptions of safety at public events and demonstrations | 1.288 | 1.429 | 0.154 | 397 | 3.77 (0.50) | 3.64 (0.60) |

| 3. Perceptions of national-level threats | 0.917 | 1.064 | 0.288 | 397 | 4.10 (0.59) | 3.98 (0.50) |

| 4. Perceptions of digital security and privacy | 1.129 | -0.682 | 0.496 | 397 | 3.43 (0.51) | 3.49 (0.43) |

| 5. Perceptions of disaster preparedness and crisis response | 0.007 | -0.207 | 0.836 | 397 | 2.33 (0.66) | 2.35 (0.68) |

| 6. Perceptions of institutional confidence and trust in security policy | 0.015 | -0.800 | 0.424 | 397 | 2.01 (0.69) | 2.10 (0.65) |

| Variable | F | t | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

df | Male M (SD) |

Female M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceptions of personal safety | 0.002 | -1.282 | 0.201 | 396 | 2.82 (0.51) | 2.89 (0.51) |

| 2. Perceptions of safety at public events and demonstrations | 0.287 | 0.030 | 0.976 | 396 | 3.76 (0.54) | 3.76 (0.49) |

| 3. Perceptions of national-level threats | 2.708 | 0.678 | 0.498 | 396 | 4.12 (0.55) | 4.07 (0.60) |

| 4. Perceptions of digital security and privacy | 0.647 | -2.970 | 0.003 | 396 | 3.33 (0.52) | 3.48 (0.48) |

| 5. Perceptions of disaster preparedness and crisis response | 2.127 | -1.296 | 0.196 | 396 | 2.27 (0.60) | 2.36 (0.69) |

| 6. Perceptions of institutional confidence and trust in security policy | 0.002 | -0.797 | 0.426 | 396 | 1.97 (0.66) | 2.03 (0.70) |

| Variables | Place of study | Faculty (field of science) | Level of studies | Family's material status | ||||

| F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Personal Safety | 2.868 | 0.048* | 0.520 | 0.668 | 1.004 | 0.367 | 0.541 | 0.654 |

| Safety at public events and demonstrations | 0.248 | 0.780 | 1.530 | 0.206 | 2.605 | 0.075 | 3.386 | 0.018* |

| National-level threats | 2.939 | 0.044* | 1.321 | 0.267 | 0.436 | 0.647 | 0.704 | 0.550 |

| Digital security and privacy | 1.321 | 0.268 | 0.249 | 0.862 | 1.981 | 0.139 | 0.204 | 0.893 |

| Disaster preparedness and crisis response | 1.346 | 0.262 | 3.885 | 0.009* | 1.046 | 0.352 | 1.084 | 0.355 |

| Institutional confidence and trust | 0.786 | 0.456 | 6.240 | 0.000** | 0.600 | 0.550 | 2.707 | 0.045* |

| Variables | Information source | Following safety news | Frequency of voting | |||

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Personal Safety | 1.311 | 0.265 | 2.948 | 0.033* | 2.420 | 0.048* |

| Safety at public events and demonstrations | 0.291 | 0.884 | 0.995 | 0.395 | 1.052 | 0.380 |

| National-level threats | 1.349 | 0.251 | 0.834 | 0.476 | 1.021 | 0.396 |

| Digital security and privacy | 4.065 | 0.003* | 0.749 | 0.524 | 1.874 | 0.114 |

| Disaster preparedness and crisis response | 8.411 | 0.000** | 0.767 | 0.513 | 2.285 | 0.060 |

| Institutional confidence and trust in security | 7.344 | 0.000** | 0.962 | 0.411 | 2.647 | 0.033* |

|

Predictor Variable |

Personal safety |

Safety at public events |

National-level threats |

Digital security and privacy |

Disaster preparedness, crisis response |

Institutional confidence and trust |

||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Gender | 0.135 | 0.061 | 0.113* | -0.069 | 0.061 | -0.058 | -0.124 | 0.070 | -0.092 | -0.082 | 0.059 | -0.070 | 0.032 | 0.078 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.080 | 0.010 |

| Age | 0.053 | 0.061 | 0.047 | 0.065 | 0.060 | 0.059 | -0.054 | 0.070 | -0.042 | 0.036 | 0.059 | 0.033 | -0.028 | 0.078 | -0.019 | 0.092 | 0.080 | 0.061 |

| Study location | -0.138 | 0.092 | -0.078 | -0.083 | 0.092 | -0.047 | -0.180 | 0.106 | -0.089 | -0.137 | 0.090 | -0.079 | 0.097 | 0.118 | 0.042 | -0.033 | 0.122 | -0.014 |

| Study year | -0.031 | 0.089 | -0.018 | 0.098 | 0.088 | 0.058 | 0.111 | 0.102 | 0.056 | -0.086 | 0.086 | -0.051 | -0.020 | 0.113 | -0.009 | -0.129 | 0.117 | -0.055 |

| Institution type | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.060 | -0.073 | 0.067 | -0.058 | -0.021 | 0.077 | -0.014 | 0.015 | 0.065 | 0.012 | 0.161 | 0.085 | 0.097 | 0.226 | 0.089 | 0.133 |

| Field of study | -0.095 | 0.084 | -0.061 | 0.027 | 0.083 | 0.017 | 0.067 | 0.096 | 0.038 | 0.051 | 0.081 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.107 | 0.017 | -0.062 | 0.111 | -0.030 |

| Study level | 0.013 | 0.056 | 0.012 | -0.009 | 0.056 | -0.008 | -0.017 | 0.065 | -0.014 | -0.054 | 0.055 | -0.051 | 0.043 | 0.072 | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.075 | 0.018 |

| Average grade | 0.035 | 0.084 | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.083 | 0.015 | 0.032 | 0.096 | 0.017 | -0.131 | 0.081 | -0.080 | -0.152 | 0.107 | -0.069 | -0.030 | 0.111 | -0.013 |

| Household size | -0.039 | 0.071 | -0.028 | -0.145 | 0.070 | -0.107 | -0.078 | 0.081 | -0.050 | 0.040 | 0.069 | 0.030 | -0.141 | 0.090 | -0.079 | -0.202 | 0.094 | -0.109 |

| Economic status | -0.081 | 0.057 | -0.075 | 0.018 | 0.056 | 0.017* | 0.035 | 0.065 | 0.028 | -0.151 | 0.055 | -0.143 | -0.081 | 0.072 | -0.058 | -0.035 | 0.075 | -0.024 |

| Safety involvement | 0.077 | 0.054 | 0.072 | -0.053 | 0.053 | -0.051 | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.055 | 0.094 | 0.052 | 0.090* | 0.315 | 0.068 | 0.226* | 0.280 | 0.071 | 0.195 |

| Safety sources | 0.115 | 0.079 | 0.076 | -0.061 | 0.078 | -0.040 | 0.128 | 0.090 | 0.074 | 0.073 | 0.076 | 0.049 | 0.077 | 0.100 | 0.039* | -0.021 | 0.104 | -0.010* |

| Safety news | 0.135 | 0.061 | 0.113 | -0.069 | 0.061 | -0.058 | -0.124 | 0.070 | -0.092 | -0.082 | 0.059 | -0.070 | 0.032 | 0.078 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.080 | 0.010 |

| Voting frequency | 0.053 | 0.061 | 0.047 | 0.065 | 0.060 | 0.059 | -0.054 | 0.070 | -0.042 | 0.036 | 0.059 | 0.033 | -0.028 | 0.078 | -0.019 | 0.092 | 0.080 | 0.061 |

| R2 | 0.045 (0.016) | 0.031 (0.01) | 0.029 (-0.001) | 0.063 (0.034) | 0.086 (0.058) | 0.079 (0.051) | ||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).