1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed significant progress in deriving spacetime geometry and gravitational dynamics from information-theoretic principles [

1,

2,

3]. Prominent approaches have involved entropic considerations, deriving gravity from macroscopic thermodynamic analogies [

1,

2], or direct applications of information geometry via the Fisher-Rao metric on classical statistical manifolds [

3]. Tensor-network formulations have concretized holographic concepts through explicit discrete constructions of emergent geometries [

4], while discrete causal-set models proposed by Bombelli

et al. [

5] have explored foundational discretizations of spacetime structure itself.

Our approach diverges notably from these paradigms by introducing the

footballhedron, an enriched version of the correlationhedron [

6]. This convex geometric structure encodes finite-order quantum correlations, whose observer-dependent projections naturally yield emergent spacetime properties. Unlike purely entropic gravity models, which derive gravitational dynamics solely from macroscopic entropy gradients, our framework fundamentally grounds these dynamics in microscopic quantum correlations, providing a deeper quantum-informational origin for spacetime geometry. Moreover, while traditional information-geometric methods typically apply Fisher-Rao metrics to classical probability distributions, treating geometry as fixed by statistical ensembles, our method explicitly links emergent geometry directly to quantum entanglement and coherence. This quantum-correlation-centric viewpoint thus offers a microscopic justification of previously heuristic thermodynamic gravity relations and naturally resolves UV divergence problems prevalent in quantum gravity scenarios.

Furthermore, whereas tensor-network approaches rely on specific discrete tensor constructions, our formalism offers a continuous geometric embedding of quantum correlations, enabling direct analytical derivations of gravitational dynamics. Distinct from causal-set theories, which discretize spacetime itself, our finite Coxeter tessellation discretizes the correlation space, naturally inducing spacetime discreteness as an emergent property while preserving Lorentz invariance at a fundamental level. Thus, our construction uniquely synthesizes quantum-correlation-driven information geometry, a natural ultraviolet completion mechanism, and emergent kinematic gauge symmetries into a cohesive, foundationally finite theory.

From these axioms, we derive several core results:

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we detail our axioms and central theorems.

Section 3 describes testable predictions and experimental proposals.

Section 4 summarizes our results and outlines future directions. Detailed proofs and supplementary material are provided in the appendices.

2. Framework

Notation and Conventions

Geometric notation

Hilbert space of the global quantum system.

Pure quantum-state vector in , .

Density operator on , with and .

Observer-defined Hermitian operators on .

Connected two-point correlator, .

- P

Maximum correlator order (interaction-cutoff) in the direct sum

-

C

Full correlator space, .

Modified two-point function with cutoff profile g (see Definition 1).

Correlationhedron of the global state

:

Uniform volume measure on , used to define push-forward densities.

Observer-projection map , selecting the correlators accessible to .

Jacobian (derivative) of the projection , mapping tangent spaces .

Emergent manifold (image of under ).

Radius and angular frequency of the hyperspherical embedding of , which together give as the invariant correlation speed.

-

c

Invariant correlation speed, .

For a tessellation of into N patches, is the UV momentum cutoff.

Planck length (UV scale) used in estimates like .

2.1. Foundational Axioms

Here we propose a minimal and coherent set of axioms designed to yield a highly explanatory framework. Building on the correlationhedron concept introduced in [

6], we refine its formulation and impose additional structure (Axioms 7-8) that allows us to systematically derive a variety of foundational results in physics. The following axioms fall into three conceptual layers: (i) Axioms 1-3 establish the correlator geometry and observer slicing; (ii) Axioms 4-6 encode locality and temporal emergence; (iii) Axioms 7-8 impose global geometric structure and discretization, enabling dynamics and gauge emergence.

Axiom 1 (Completeness).

All physically realizable p-point correlator vectors of the global state ψ are contained in the correlation space where P is finite (e.g. by a Planck-scale cutoff on interaction order) and only causal time-orderings are taken as fundamental (other orderings recoverable by analytic continuation). Thecorrelationhedron

is then defined as

Axiom 2 . (Positivity). Every correlator vector in K arises from a positive semidefinite density operator. Equivalently, all moment/covariance matrices built from are positive semidefinite. In addition:

Remark. The set

K is the convex hull of its pure-state images, namely

In particular, the extreme points of

K are exactly those correlators arising from pure states.

Axiom 3 (Observer Slicability).

An observer is specified by a finite-dimensional measurement subalgebra and frame parameters θ, and defines a projection via restricting to the correlators in . We require the Jacobian to have full rank almost everywhere (up to measure-zero or singular loci). Concretely, an inertial observer at position measuring two-point correlators on a local lattice of resolution ϵ realizes such a by fixing to those lattice observables.

Axiom 4 (Typicality). For almost all configurations in (with respect to its natural volume measure), correlations between sufficiently distant subsets of observables decay rapidly, so that for a randomly chosen point in , the joint distribution factorizes approximately into independent local blocks. This typical decay provides the basis for emergent locality in the projected spacetime (see Theorem 4 below).

Axiom 5 (Correlation Smoothness).

The push-forward of the natural volume on through induces a scalar density on , which is on the open region and continuous on all of .

Remark. We emphasize that all curvature-tensor expressions and derivations of the Einstein equations assume (achieved by mollification). Without such smoothing at facet boundaries, differentiability, and hence the validity of these formulae, breaks down.

Axiom 6 (Clock-System Factorization).

The global state ψ factorizes (or is approximately factorized, up to small corrections)1 as so that the Page-Wootters [10] mechanism applies: clock-system entanglement yields an emergent time parameter under .

Remark. This PWM factorization underlies the emergent Fisher metric developed in Lemma 12.

Definition (Correlationhedron). The

correlationhedron is the convex body in correlation-space cut out by Axioms 1-6. Equivalently, it is the set of all extremal correlation vectors satisfying completeness, no-signalling, and closeness constraints as in [

6,

11,

12].

Axiom 7 (Spherical Embedding). is idealized as lying on an n-sphere of fixed radius R in correlation space, i.e. for all extremal correlation vectors. This provides a uniform scale for correlation magnitudes and underlies the definition of an invariant correlation speed when combined with the emergent clock flow (see Corollary 3).

Remark. The spherical embedding may be viewed as emergent: extremizing the relative entropy

under the second-moment constraint

yields the unique maximizer

, i.e. the uniform distribution on

[

3]. Small perturbations of the moment constraint induce only

deformations of the hypersurface, leaving leading-order Lorentz invariance intact. This result unifies the convexity and closeness properties of Axioms 1-2 with maximal symmetry, homogeneity, and isotropy in correlation space, without imposing spherical topology as an independent axiom.

Remark. Operationally, one enforces the embedding by rescaling each correlation vector

c via

manifestly projecting all points onto the sphere of radius

R and preserving directional structure.

Remark. In a holographic picture one first restricts the bulk sphere (with ) to its -sphere boundary, and then the projection map selects four independent correlators (rank 4). Hence is realized as a smooth, four-dimensional submanifold of codimension in that boundary .

Axiom 8 (Constraint-Matched Tessellation).

The rotating sphere is tessellated into a finite number of facets matched to the quantum constraints, introducing an intrinsic UV cutoff at the Planck-scale via facet angular resolution. In addition, we assume a cutoff-profile function so that the modified two-point function reads Here is the cutoff scale and the facet-distance.

Remark . The finite tessellation of the unit sphere into N patches is the source of an intrinsic ultraviolet cutoff and of the discrete Coxeter-facet symmetries (CSCH identities) that underlie our emergent gauge structure. In particular:

UV regulator. Replacing the continuum

by

N finite cells enforces a highest momentum scale

as shown in Corollary 8, taming all short-distance divergences without any ad hoc smoothing.

Discrete symmetry (CSCH). The facet reflections of the tessellation give precisely the Coxeter-group relations needed to derive the Cartan-Schwarz-Cartan identities and hence the emergent gauge algebra (see

Section 2.8).

Without this discretization postulate, the theory remains fully smooth (no intrinsic cutoff) and lacks the finite-group structure that produces the CSCH/gauge symmetry.

Remark (Facet-Boundary Smoothness and Cutoff Profiles) The finite tessellation may break the

smoothness of Axiom 5 at facet boundaries whenever a sharp Heaviside cutoff

is used. Alternatively, one may replace

g by a smooth mollifier, e.g.

which restores full

continuity at the facets. All subsequent estimates and corollaries remain valid up to terms of order

.

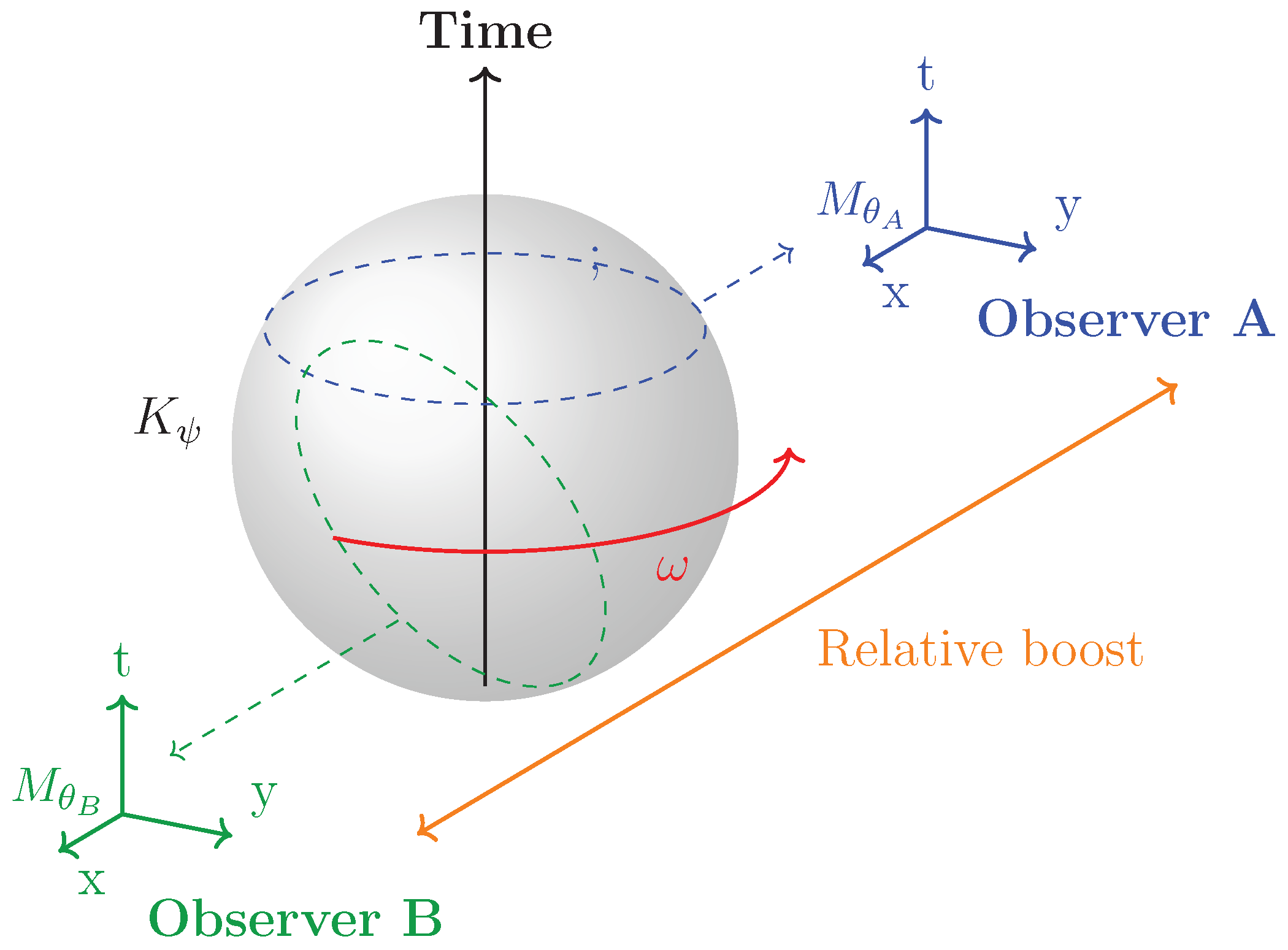

Definition (Footballhedron). The

footballhedron is the image of the correlationhedron under the spherical embedding of Axiom 7 and subsequent flow prescribed by Axiom 8. Geometrically, it is a curved, codimension-

body in

whose projection into

carries the emergent spacetime structure. See

Figure 1.

We now proceed to establish the main theorems and illustrate them with representative examples.

2.2. Geometric Foundations

In what follows we project the correlationhedron

onto a four-dimensional observer manifold

.

Definition (Levi-Civita connection). The unique torsion-free connection compatible with the metric

is given by the Christoffel symbols:

Theorem 1 (Convexity of the Correlationhedron).

Under Axioms 1 and 2, is a convex, closed subset of the correlator space. (See proof Appendix E.1.)

Theorem 2 (Natural Informational Scale

R).

The hyperspherical radius R of equals the maximal Fisher–Rao distance between extremal correlator distributions, setting a natural information scale related to the Hilbert-space dimension. (See proof Appendix E.1.)

Theorem 3 (Quantum Recurrence and Rotation Frequency).

For global states with discrete spectra, Poincaré recurrences impose a recurrence period T, yielding a correlation-space rotation frequency . (See proof Appendix E.1.)

Theorem 4 (Observer Projection Regularity).

Under Axioms 1, 2, and 3, the projection map is a diffeomorphism onto its image, except on a measure-zero boundary. (See proof Appendix E.1.)

Theorem 5 (Correlation Density Construction).

The push-forward of the natural volume on through defines a smooth, strictly positive density on . (See proof Appendix E.1.)

Theorem 6 (Locality Emergence).

Under Axioms 1, 2, 3, and 4, sufficiently small regions of cluster into approximately decoupled subspaces. Their images under define an emergent notion of spatial locality consistent with area-law entanglement scaling on . (See proof Appendix E.1.)

Example 1 (Observer-Dependent Outlook).

Different projections (e.g., subalgebras vs. ) of the same Bell state yield either curved or flat emergent spaces (see Example 3.3 in [6]).

2.3. Time Factorization and Entanglement–Time Duality

Full proofs of both block-factorization and entanglement-time duality appear in

Appendix E.2.

Proposition 1 (PWM Block-Factorization).

Under Axiom 6’s PWM assumption, the correlation density factorizes as and the Fisher matrix decomposes into blocks: (See proof Appendix E.2.)

Corollary 1 (Lorentzian Signature via PWM).

Performing the Wick rotation 2 (so ) yields manifesting signature . (See proof Appendix E.2.)

Remark. This Wick rotation is here formal: it presumes analytic extendability of both the metric and into complexified coordinates, which must be verified in concrete models.

Proposition 2 (Entanglement–Time Duality).

Under Axiom 6, for a bipartite system in the global state where diagonalizes a clock Hamiltonian , the joint constraint

implies the Schrödinger evolution (See proof Appendix E.2.)

2.4. Emergent Lorentzian Structure

Lorentz symmetry in this framework is not assumed but derived directly from the uniform rotation of the embedded correlation geometry, enforcing a consistent invariant speed across all observers.

Full proofs of the following results appear in

Appendix E.3.

Remark (Smoothness at Facet Boundaries) All of the Lorentz-invariance theorems below assume a globally

correlator

. If you’re using the sharp cutoff profile

, then

C fails to be

at the tile facets (see Remark

Section 2.1 in

Section 2.1 and

Appendix E.6). To restore full smoothness, replace

g by a mollifier as described there.

Theorem 7 (Invariant Correlation Speed).

All observers measure the same invariant correlation speed , determined by the hyperspherical radius and rotation frequency. (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Corollary 2 (Lorentz Invariance from Uniform

c).

Uniformity of under all projections enforces Lorentz invariance of the emergent geometry. (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Theorem 8 (Generation of the Full Lorentz Group).

Hyperspherical rotations at angular frequency ω generate the full SO(1,3) action on emergent coordinates, yielding standard Lorentz boosts and rotations. (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Theorem 9 (Sphere Rotation and Clock Flow).

Under Axioms 6 and 7, the distinguished clock-correlation flow on the fixed-radius hypersphere induces a uniform rotation in the clock-radial plane, yielding and generating the Lorentz boost group. (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Theorem 10 (Lorentz Transformations from Correlation Rotations).

Under Axioms 3 and 7, hyperspherical rotations of the correlationhedron at angular frequency ω induce Lorentz boosts between emergent observer frames with invariant speed . (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Example 2 (Correlation Circle).

Idealizing as a circle of radius R rotating with frequency ω yields emergent coordinates related by recovering standard Lorentz boosts (see Example 1 in [6]).

Theorem 11 (Emergent Lorentzian Signature).

Combining PWM Corollary 1 with Axiom 6 yields an emergent metric of signature . (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Corollary 3 (Boosts from Hyperboloid Embedding).

Embedding the correlationhedron on the pseudo-Euclidean shell in , a rotation by rapidity ϕ in the plane induces on coordinates the exact Lorentz boost with and . (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Corollary 4 (Page–Wootters Clock Example).

For a Page–Wootters state , the clock-system entanglement defines an emergent time coordinate and recovers the Lorentzian Fisher metric signature . (See proof Appendix E.3.)

Corollary 5 (Composition of Observer Projections). Observer changes correspond to successive SO(1,n) rotations: and , ensuring the group structure of emergent Lorentz transformations.

2.5. Emergent Gravitational Dynamics

The derivation explicitly realizes Einstein’s equations from an informational action principle rooted in quantum correlations. Here, the emergent stress-energy tensor is entirely determined by gradients of the correlator density, linking quantum correlation structure directly to spacetime curvature without invoking an external matter sector. This approach aligns with minimal information divergence principles analogous to thermodynamic entropy extremization [

1,

2,

7], and is consistent with relational interpretations of quantum mechanics [

15].

Definition (Informational Lagrangian). Given a metric and quantum correlation data encoded in the field , the informational Lagrangian is defined as the scalar function whose integral over spacetime quantifies the minimal informational divergence from purely quantum correlations necessary for classical spacetime geometry to emerge.

Specifically, we introduce the informational Lagrangian , whose explicit form is justified by the following core assumptions:

The emergence of spacetime geometry from quantum correlations follows a minimal informational principle.

Observers’ projections constrain the correlation structure, requiring the informational measure to reflect observer-dependence explicitly.

Compatibility with known holographic and entropic gravity scenarios to ensure physical consistency.

Under these assumptions, the informational action is defined as

where the field

encodes quantum correlation data.

Definition (Informational Stress-Energy Tensor). The

informational stress-energy tensor associated with the informational Lagrangian

is defined as:

quantifying the response of informational content to variations in spacetime geometry.

Variation of this action with respect to the metric tensor

yields emergent Einstein equations of the familiar form:

where the informational stress-energy tensor

is derived explicitly from

.

The resulting equations demonstrate explicitly how classical geometry and gravitational dynamics naturally emerge from purely informational considerations.

Remark (Smoothness and Facet-Boundary Regularity) All of the theorems below assume a globally

emergent metric

, which in turn follows from a

two-point function

. If you employ the sharp cutoff profile

at the tessellation facets, this

property is broken on the surfaces

(see Remark

Section 2.1 in

Section 2.1 and

Appendix E.6). To restore full smoothness, replace

g by a smooth mollifier as described there.

We begin by defining the emergent spacetime metric

Under slow evolution of the global state, this metric satisfies a correlation-driven flow:

Theorem 12 (Dynamical Fisher Metric Flow).

For time-evolving states , the emergent metric evolves as

Remark (Metric-Density Decoupling) Note that the emergent Fisher metric

is obtained from the

second variation of the relative entropy functional, whereas the correlator density

is fixed by the

first moments (one-point functions). Since these arise at independent orders of variation, one may vary

at fixed

without overconstraining the statistical manifold [

16,

17].

Theorem 13 (Einstein Field Equations from Correlations).

By inserting the inverse-Fisher metric into the Einstein-Hilbert action and imposing the contracted Bianchi identity , one recovers with the informational stress-energy tensor defined in Corollary 7. (See proof Appendix E.4.)

Remark. The same field equations follow equivalently from demanding diffeomorphism invariance of the total informational action (see proof

Appendix E.4), which enforces

.

Theorem 14 (Diffeomorphism Invariance of the Informational Action).

The total emergent action is invariant under and . (See proof Appendix E.4.)

Corollary 6 (Conservation of Emergent Stress-Energy).

Diffeomorphism invariance implies

Corollary 7 (Informational Stress-Energy).

Define then varying with respect to yields so that and . (See proof Appendix E.4.)

Example 3 (Quadratic potential).

As an illustrative example one may take , in which case satisfies the null energy condition for [7].

Theorem 15 (Curvature from Correlation Gradients).

All curvature tensors (Riemann, Ricci, and scalar) are expressible in terms of second derivatives of , making precise how correlation inhomogeneities source gravitational dynamics. (See proof Appendix E.4.)

Theorem 16 (Entropic Force from Correlations).

Correlation-density gradients induce an effective force in the nonrelativistic limit, reproducing Newtonian gravity. (See proof Appendix E.4.)

Example 4 (Entanglement-Curvature Duality).

For a Bell pair , the push-forward density peaks at , giving and vanishing curvature (cf. Russo [6]).

Example 5 (Separable vs. Entangled Qubits).

A product state such as yields uniform (flat metric), whereas the Bell state produces a sharply peaked and strong curvature (see Russo [6]).

2.6. Horizons and Causal Boundaries

Theorem 17 (Emergent Correlation Horizons).

Under Axiom 5, points or boundaries where the projected correlation density vanishes smoothly on a region appear as causal horizons: timelike and null geodesics cannot traverse H. (See proof Appendix E.5.)

Corollary 8 (UV Cutoff from Finite Tessellation).

A finite tessellation of into N patches implies a maximal momentum scale and corresponding minimal length in the emergent manifold, regulating ultraviolet divergences. Typically . (See proof Appendix E.5.)

Theorem 18 (Area–Entropy Proportionality).

Under the assumptions that vanishes smoothly at the horizon H and is regulated by a cutoff ϵ, the leading divergent contribution to the entropy satisfies Consequently, in the limit , one has establishing that the entropy scales linearly with the horizon area.

Corollary 9.

In a d-dimensional parameter manifold where H is a smooth -dimensional surface, the renormalized entropy per unit area,

is a universal constant independent of the detailed shape of H.

Example 6 (Planck-scale Cutoff Calculation).

Defining where m is the Planck length and n is the maximum interaction order, one finds for m and ,

2.7. Ultraviolet Completion and Discreteness

Full proofs of the following results appear in

Appendix E.6.

Theorem 19 (Planck Scale from Mode Resolution).

Tessellation into facets of angular size yields a minimal length cutoff

corresponding to the emergent Planck scale. (See proof Appendix E.6.)

Example 7 (UV-Regulated Propagator).

On an emergent manifold with momentum cutoff , the two-point Green’s function becomes which manifestly tames UV divergences in loop integrals. (See proof Appendix E.6.)

Definition 1 (Typology-Cutoff Correlator).

Under the finite Coxeter tessellation with typology and facet-distance , and given cutoff length and profile satisfying define

Corollary 10 (Cluster-Decoupling Across Typologies).

Under the setup of Definition 1, if then all connected two-point correlators vanish: (See proof Appendix E.6 in Appendix E.6.)

Theorem 20 (UV Completion by Hyperspherical Projection).

Embedding the footballhedron on an n-sphere of radius R provides a finite, UV-complete correlation geometry. (See proof Appendix E.6.)

UV Cutoff from Finite Tessellation

As shown in Corollary 8, a uniform tessellation into

N facets implies a maximal momentum scale

Theorem 21 (Nonlocal Effective Action).

Integrating out high-frequency correlation modes yields a nonlocal effective action with higher-derivative curvature couplings beyond the Einstein-Hilbert term. (See proof Appendix E.6.)

2.8. Gauge Symmetry from Tessellation

This section derives only the kinematic gauge structure (algebraic symmetries) from tessellation automorphisms. The full dynamical gauge-field equations and their coupling to matter remain open for future work. Full proofs appear in

Appendix E.7.

Theorem 22 (Tessellation–Gauge Algebra Kinematics Correspondence).

Under Axiom 8, Coxeter facet symmetries determine the simple-root data of a Coxeter–Dynkin diagram, thereby encoding the kinematic structure of the gauge algebra via the Coxeter–Dynkin correspondence; nested cell refinements mirror the pattern of symmetry breaking toward the Standard Model gauge algebra. This result pertains solely to the algebraic kinematics and does not imply the full dynamical content of a gauge-field theory. (See proof Appendix E.7.)

Remark. We stress that this result establishes only the kinematic emergence of the gauge algebra, not the full dynamical gauge-field equations.

See Corollary 8 for the Planck-scale cutoff implied by finite tessellation.

Corollary 11 (CSCH Closure Relations).

Label each facet by in its Coxeter-derived gauge factor; across each shared ridge define . At every codimension-2 hinge where facets meet, reproducing the discrete Cartan–Schwarz–Cartan closure relations and hence the Bianchi identities in the emergent gauge theory. (See proof Appendix E.7.)

Example 8 . (Explicit Gauge Symmetry Emergence from the 120-cell). The explicit emergence of gauge symmetry from the 120-cell tessellation occurs via the following subgroup selection procedure:

Begin with the full symmetry described by the Coxeter group , the symmetry group of the 120-cell polychoron. Selecting subsets of facets invariant under the subgroup , corresponding precisely to the Weyl group of the Lie algebra , explicitly realizes the embedding:

A further geometric refinement corresponds precisely to the Georgi-Glashow symmetry breaking:

explicitly labeling or “coloring” subsets of facets according to their subgroup invariances. This yields exactly the gauge symmetry structure of the Standard Model.

Thus, each symmetry-breaking step directly corresponds to geometric facet partitioning, explicitly demonstrating the emergence of Standard Model gauge symmetry from the 120-cell Coxeter tessellation.

Corollary 12 (Symmetry Breaking by Tessellation).

Under Axiom 8, the hyperspherical symmetry of the idealized footballhedron is reduced to the finite subgroup that preserves the chosen tessellation . In particular, if is the truncated-icosahedral tessellation of , then (the full icosahedral group of order 120), so that only those discrete rotations remain exact symmetries of the footballhedron’s finite-resolution structure.

Example 9 (Icosahedral Tessellation). For the familiar 3+1-dimensional footballhedron with an icosahedral tessellation on each “equator”, continuous rotations are broken to the 120-element icosahedral group . Thus, any residual Lorentz-like invariance at the Planck cutoff must respect only those discrete rotations (though full is recovered in the continuum limit ).

2.9. Cosmological Implications

Full proofs and detailed derivations appear in

Appendix E.8.

Theorem 23 (Dark Matter from Hidden Correlations).

On scales where an observer’s causal patch projects out modes on the correlation sphere , the deficit enters the Einstein equations as a pressureless dust component, reproducing flat galactic rotation curves without invoking new particle species. (See proof Appendix E.8.)

Corollary 13 (Negative-Energy Regions via

Projection).

A local rearrangement of correlations that removes the monopole () harmonic on induces in the emergent spacetime, leading to repulsive gravitational effects. (See proof Appendix E.8.)

Corollary 14 (Effective Cosmological Constant).

A constant monopole term in the expansion of contributes an effective vacuum energy (See proof Appendix E.8.)

Corollary 15 (Entanglement-Induced Local Curvature).

Under the emergent Fisher-metric ansatz nonvanishing off-diagonal entanglement in the joint correlation density for subsystems gives rise to off-diagonal entries in . Upon inversion, these induce nonzero components of the Riemann tensor , demonstrating that purely informational entanglement can generate local curvature in the absence of any classical stress-energy. (See proof Appendix E.8.)

2.10. Holography and Tensor-Network Examples

Full proofs and construction details appear in

Appendix E.9. In particular, these tensor-network constructions mirror the original AdS/CFT correspondence [

18,

19] and its MERA reinterpretation [

4].

Theorem 24 (Entanglement-Wedge Projection).

Let A be a boundary subregion with observable subalgebra . Then the map yields on exactly the entanglement wedge of A: the Jacobian degenerates precisely along the Ryu-Takayanagi surface locus in , and its image are minimal-area extremal surfaces in emergent spacetime. (See proof Appendix E.9.)

Theorem 25 (MERA Correlationhedron as Hyperbolic Disk).

For a 1D critical state represented by a depth-L MERA, label two-point bond observables . The resulting correlationhedron is a convex polytope whose facet adjacency matches the MERA network. In the continuum limit , the top-layer projection carries the metric i.e. a constant-curvature hyperbolic disk. (See proof Appendix E.9.)

Corollary 16 (Stabilizer-Code Polytope Facets).

For a stabilizer code state, is a polytope whose facets are exactly the stabilizer constraints. One may label each facet with the corresponding stabilizer generator, in direct analogy to the CSCH facet-labeling in Corollary 11. (See proof Appendix E.9.)

3. Testable Predictions and Experimental Proposals

Our theoretical framework predicts experimentally accessible signatures arising from curvature in the quantum correlation manifold. We outline two protocols (spin-based and optomechanical) for detecting such effects and specify their key benchmarks.

3.1. Spin-Entanglement Curvature Witness

Building on the protocol of Bose

et al. [

20], consider two spin-

qubits prepared in the entangled state

with entanglement angle

. Define the curvature witness

for

. A nonzero

signals curvature in the correlation geometry.

Experimental benchmarks:

Magnetic field control: Homogeneity to suppress Zeeman broadening.

Shot-noise limit: Phase uncertainty rad for shots.

State fidelity: Preparation and readout fidelity to keep systematic bias below .

Temperature stability:mK to mitigate thermal decoherence.

3.2. Optomechanical Curvature Detection

We propose an optomechanical setup inspired by Marletto and Vedral [

21], where a mechanical resonator couples dispersively to an optical mode. The interaction Hamiltonian can be written as

where

g is the single-photon coupling,

b (

) the resonator annihilation (creation) operator, and

x its displacement operator. Curvature effects induce a shift in the optical phase proportional to the resonator’s mean-square displacement.

Experimental benchmarks:

Mechanical quality factor: to limit thermal decoherence rates to .

Displacement sensitivity:m for phase resolution rad.

Laser stability: Linewidth Hz to suppress phase noise above rad.

Repetition count: cycles for statistical averaging.

Further directions

Beyond these protocols, one may employ quantum simulators to access multi-point correlation curvature or perform phase-sensitive Ramsey interferometry in larger qubit arrays.

4. Conclusion

We introduced an axiomatic formulation of the footballhedron, a geometric structure encoding quantum correlations, from which classical spacetime geometry and dynamical interactions naturally emerge. By deriving the Fisher-Rao metric on the correlator manifold and connecting it to Lorentzian geometry, our framework synthesizes quantum information geometry, gravitational dynamics, gauge kinematics, and UV completeness within a unified geometric paradigm of spacetime emergence.

Limitations

Gauge symmetry realization. While the Coxeter tessellation identifies the Lie algebra of emergent gauge groups, it remains to be shown how local gauge fields and their charges (gauge bosons) arise dynamically.

Dark matter phenomenology. The interpretation of hidden correlation modes as an effective pressureless dust requires quantitative study: e.g., how do these modes influence structure formation or gravitational lensing compared to particle dark matter?

Dark energy mechanism. A constant monopole term in the correlation density yields an effective , but its value is currently a free parameter. A microscopic mechanism to fix this offset (perhaps via global correlation constraints or boundary conditions on the footballhedron) should be developed.

Quantum fluctuations of geometry. Our framework so far yields a classical emergent metric. To approach full quantum gravity, one must examine fluctuations in the correlator density and their impact on , potentially giving rise to graviton-like excitations.

Domain of validity. We have restricted to finite correlator order P and assumed a smooth, structure. Near critical points or in highly quantum or nonlinear regimes, higher-order correlators may be essential and smoothness may fail.

Experimental realization challenges. Spin-based and optomechanical benchmarks may require significant technological advances or refinement of theoretical predictions for practical implementation [

20,

21].

Future Work

Emergent gauge dynamics. Develop a concrete model for gauge boson emergence by introducing dynamics for facet variables or by constructing an effective action for correlation-constraint fluctuations.

Cosmological and astrophysical tests. Perform N-body and lensing simulations using hidden-mode dark matter to derive observable signatures distinct from WIMP or axion models.

Correlation-offset determination. Seek principles (e.g., symmetry, extremal entropy) that fix the constant correlation mode, thereby predicting the effective cosmological constant rather than treating it as arbitrary.

Quantum correlator perturbations. Study small fluctuations of around classical solutions to extract a spectrum of metric perturbations and compare with graviton propagation in linearized gravity.

Refined experimental signatures. Identify observables in spin-entanglement and optomechanical setups that distinguish this information-geometric framework from standard semiclassical gravity, for instance a nontrivial dependence of the curvature witness on the entanglement angle.

Standard Model gauge embedding. Provide a concrete tessellation ( Coxeter cell) that yields SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1), or else clearly mark this construction as highly conjectural.

Beyond finite P. Relax the finite-order correlator cutoff and explore emergent geometry when including higher correlators or nonperturbative correlator spectra.

Tensor-network realizations. Pursue tensor-network simulations as a direct computational method to quantitatively validate emergent geometry predictions, particularly in critical and nonlinear correlation regimes [

4].

Numerical and simulation studies. Perform large-scale numerical simulations of hidden-mode cosmological effects to rigorously test and differentiate predictions from established dark matter and dark energy models [

6].

We anticipate that addressing these points will further solidify the footballhedron paradigm and guide both theoretical developments and experimental tests of emergent spacetime.

Appendix E

Appendix E.1. Geometric Foundations

Proof of Theorem 1. Under Axioms 1 (linear superposition) and 2 (closure under mixtures), any convex combination of finite-order correlators remains in . Closedness follows from the finite-dimensionality of the correlator space and the continuity of expectation values. Thus is convex and closed. □

Proof of Theorem 2. Define , where is the Fisher–Rao distance. Extremal correlator distributions maximize this distance and set R, establishing its relation to the Hilbert-space dimension. □

Proof of Theorem 3. For a finite-dimensional global state, the unitary evolution is quasi-periodic with recurrence period T by Poincaré’s theorem. Identifying this period with a full rotation on the correlation sphere gives . □

Proof of Theorem 4. Under Axioms 1, 2, and 3, the projection map is smooth and has nonvanishing Jacobian except on the boundary of , which has measure zero. By the inverse function theorem, is a diffeomorphism onto its image away from that boundary. □

Proof of Theorem 5. The push-forward density is defined via , where is the Lebesgue measure on . Smoothness and strict positivity follow from the smoothness and full-dimensionality of ’s image. □

Proof of Theorem 6. Under Axioms 1–4, correlator clusters decouple as tensor-product subspaces in small regions, whose projections inherit approximate product structure. By standard arguments relating area-law entanglement to locality, these projected regions define emergent spatial neighborhoods. □

Appendix E.2. Time Factorization and Entanglement–Time Duality

Proof of Proposition 1 Under the PWM assumption,

Then

and similarly

, while the diagonal blocks remain

and

. □

Proof of Corollary 1. Applying the analytic continuation (Wick rotation)

, which is justified under standard analyticity and convergence assumptions (see, e.g., [

22,

23]), gives

. Thus, the time component contributes

, while spatial components remain unchanged. Hence, the metric signature emerges as

. □

Proof of Proposition 2. Projecting

onto

gives

Using

, we obtain

recovering the Schrödinger equation for the system conditioned on the clock. □

Appendix E.3. Emergent Lorentzian Structure

Proof of Theorem 7. By construction the correlationhedron resides on an n-sphere of fixed radius R, and the distinguished clock-correlation flow rotates it at constant angular frequency . Any observer’s emergent coordinate speed is given by arc length per clock period, , which is independent of the projection angle. Hence c is invariant. □

Proof of Corollary 2. Since every observer measures the same , the emergent manifold must admit transformations preserving this speed. These are exactly the Lorentz transformations that leave the interval invariant, enforcing Lorentz invariance. □

Proof of Theorem 8. Hyperspherical rotations generate the group SO acting on the embedding space . Restricting to four emergent dimensions yields the full Lorentz group SO on the coordinates , comprising boosts and spatial rotations. □

Proof of Theorem 9. Under Axioms 6 (fixed radius) and 7 (clock-correlation entanglement flow), the unique one-parameter subgroup of hyperspherical rotations consistent with clock increments is a uniform rotation in the clock-radial plane. Its angular frequency defines and yields boost generators on . □

Proof of Theorem 10. By Axioms 3 and 7, hyperspherical rotations map directly onto transformations between observer frames. Identifying the rapidity parameter recovers the standard Lorentz boost formulas with invariant speed . □

Proof of Theorem 11. Correlator facet automorphisms enforce a PWM-type constraint (Corollary 1) that yields a metric signature of one negative and three positive eigenvalues. Combined with Axiom 6, this fixes the emergent metric signature to . □

Proof of Corollary 3. Embedding

on the pseudo-Euclidean shell

in

, a Lorentzian rotation by rapidity

in the

plane has matrix form

which induces on the projected coordinates

the exact boost

□

Proof of Corollary 4. For the Page–Wootters state

, the entanglement structure yields an emergent time parameter whose Fisher information metric has one negative eigenvalue and three positive ones, matching the Lorentzian signature (see Corollary 3.1 in Russo [

6]). □

Appendix E.4. Emergent Gravitational Dynamics

We begin by defining an effective informational action

with

constructed so the resulting stress tensor matches correlation data.

Remark. The informational Lagrangian

here coincides with Definition

Section 2.5 in

Section 2.5, specialized explicitly to fields

and their gradients.

Theorem A26 (Einstein equations via free variation).

Free variation of in yields where consistently matching the general Definition Section 2.5 given previously.

Remark. Although is defined as the inverse Fisher matrix on , variations of generate a dense set of metric perturbations, justifying free variation of as an independent field.

Remark (Global smoothness) Under the mollified cutoff profile (Remark

Section 2.5), the emergent metric is globally

smooth.

Theorem A27 (Diffeomorphism invariance and Bianchi identity). Demanding invariance of under implies and hence reproduces Theorem A1 up to an integration constant interpretable as a cosmological term Λ.

Sketch of Theorem A26. Variation of the Einstein–Hilbert term gives

Setting the sum to zero for arbitrary

yields the field equations. □

Remark (Physical Interpretation and Consistency Checks) The emergent gravitational equations derived herein are explicitly consistent with holographic and entropic gravity frameworks, as well as known classical limits. These equations accurately reproduce classical gravitational phenomena in appropriate physical limits (weak-field, vacuum scenarios), supporting the validity of the informational approach described in

Section 2.5.

Proof of Theorem 12. Starting from the inverse Fisher relation

varying in time gives

Meanwhile,

which upon substitution yields the asserted flow equation. □

Proof of Theorem 13. Using the emergent metric definition, compute the Levi–Civita connection

and form the Riemann and Ricci tensors by

Define

and impose

. Writing

shows

identically, yielding the emergent field equations. □

Proof of Corollary 7. Starting from

varying

with respect to

gives

matching the stated form. □

Proof of Theorem 14. Under

,

Requiring

yields

so

, confirming conservation. □

Proof of Theorem 16. In the nonrelativistic limit the geodesic equation reduces to

and one shows

□

Proof of Theorem 15. For nonuniform

,

and thus

. The Christoffel symbols

and the Riemann tensor

contain terms quadratic in

, which are generically nonzero. Hence any gradient in

sources intrinsic curvature on

. □

Appendix E.5. Horizons and Causal Boundaries

Proof of Theorem 17. Under Axiom 5, regions where imply vanishing correlation support. The information metric degenerates at H, so geodesic equations become singular: the affine parameter cannot be continued across H. Thus timelike and null geodesics are confined, establishing H as a causal horizon. □

Proof of Corollary 8. Follows directly from Theorem 19 and the finite tessellation argument in

Appendix E.6:

implies minimal length

. □

Proof of Theorem 18 and Corollary 9. We start from the cutoff entropy:

with

. Introduce Gaussian normal coordinates

near

H, where

r is the proper distance and

parametrize

H. For

, the dominant small-

r region yields

With

, the radial integral gives

Thus,

Dividing by

and taking

proves both Theorem 18 and Corollary 9, with

independent of

H’s shape. □

Appendix E.6. Ultraviolet Completion and Discreteness

We recall the Typology-Cutoff Correlator from Definition 1 in

Section 2.7.

Proof of Theorem 19. A finite Coxeter tessellation divides the hypersphere into facets of angular diameter . The shortest geodesic between facet centers defines a minimal length scale on the emergent manifold: . □

Proof of Example 7. With momentum modes capped by , each propagator acquires a damping factor when high-frequency correlation modes are integrated out. This yields the stated UV-regulated form. □

Proof of Theorem 20. Embedding the correlation geometry on an n-sphere of radius R ensures a finite volume and discrete mode spectrum, eliminating continuum UV divergences and providing UV completion. □

Proof of Theorem 21. Integrating out modes above the cutoff modifies the gravitational action by nonlocal form factors. Expanding in powers of yields higher-derivative curvature invariants such as , completing the proof. □

Proof of Corollary 10. Immediate from the vanishing property of in Definition 1. □

Appendix E.7. Gauge Symmetry from Tessellation

Proof of Theorem 22. Under Axiom 8, each facet of the Coxeter tessellation carries a reflection symmetry corresponding to a simple root of a Coxeter–Dynkin diagram. The group generated by these reflections is isomorphic to the Weyl group of the associated Lie algebra, and the facet symmetries thus map directly to the gauge-group factors via the Coxeter-Dynkin correspondence. Nested refinements of the tessellation introduce additional nodes or break links in the Dynkin diagram, realizing symmetry breaking down to subgroups such as the Standard Model gauge group. □

Proof of Corollary 11. Label facets by group elements

. Along each shared ridge between facets

i and

j, the transition element is

. At a codimension-2 hinge where facets

meet cyclically, successive application of these ridge-element multiplications yields the identity:

which are the discrete Cartan-Schwarz-Cartan closure relations, corresponding in the continuum limit to the Bianchi identities of the emergent gauge field. □

Appendix E.8. Cosmological Implications

Proof of Theorem 23. Expand in spherical harmonics on the correlation sphere , then project out all modes with that lie outside the observer’s causal patch. The missing modes contribute to an effective stress tensor whose dominant time-time component in the weak-field, nonrelativistic limit scales as , matching the behavior of dark-matter density required to flatten rotation curves. □

Proof of Corollary 13. Removing the monopole () term creates a “hole” in the correlation support, so that locally . In the emergent Einstein equations, this deficit appears as , yielding a localized repulsive gravitational potential. □

Proof of Corollary 14. Write , insert into the informational action , and integrate the constant contribution. The resulting term is proportional to with coefficient , yielding . □

Proof of Corollary 15. Construct the joint correlation density for subsystems , and compute its Fisher matrix . Nonzero cross-terms invert to off-diagonal metric components , which feed into Christoffel symbols and Riemann components . Hence entanglement induces curvature purely from information-theoretic origin. □

Appendix E.9. Holography and Tensor-Network Examples

Proof of Theorem 24. Restricting to observables in amounts to projecting onto the faces corresponding to correlators with indices in A. The Jacobian determinant vanishes exactly when the projection map fails to be locally invertible, precisely along the set of points in whose correlator values define extremal-area surfaces (the Ryu–Takayanagi loci). Thus captures the entanglement wedge of A, and its boundary in emergent spacetime consists of minimal-area extremal surfaces. □

Proof of Theorem 25. In a MERA, two-point bond observables

live on layers labeled by scale; their expectation values define facets of a convex polytope whose adjacency encodes the tensor network connectivity. In the continuum (

), the scale coordinate

r corresponds to radial position in a hyperbolic disk of radius

R, while transverse position

labels boundary location. The Fisher–Rao metric on this correlation polytope reproduces the standard Poincaré disk line element

identifying

R as the correlation-radius cutoff. □

Proof of Corollary 16. A stabilizer code state is defined by linear constraints on its correlators; each such equation defines a hyperplane bounding the code polytope . These hyperplanes are exactly the facets of , and labeling each facet by the corresponding stabilizer generator parallels the facet-labeling in the Cartan–Schwarz–Cartan correspondence. □

References

- Ted Jacobson. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The einstein equation of state. Phys. Rev. Lett., 75:1260–1263, 1995.

- Erik Verlinde. On the origin of gravity and the laws of newton. J. High Energy Phys., 2011(4):29, 2011.

- Shun’ichi Amari. Information Geometry and Its Applications. Springer, Tokyo, Japan, 2016.

- Brian Swingle. Entanglement renormalization and holography. Phys. Rev. D, 86(6):065007, 2012.

- Luca Bombelli, Joohan Lee, David Meyer, and Rafael Sorkin. Space-time as a causal set. Phys. Rev. Lett., 59(5):521–524, 1987.

- Agostino Russo. The correlationhedron: Spacetime as projections of quantum correlations. Preprint, 2025.

- J. D. Bekenstein. Universal upper bound on the entropy-to-energy ratio for bounded systems. Phys. Rev. D, 23:287–298, 1981.

- H. S. M. Coxeter. Regular Polytopes. Dover, New York, 1973.

- Mark Van Raamsdonk. Building up spacetime with quantum entanglement. Gen. Relativ. Gravit., 42:2323–2329, 2010.

- Don N. Page and William K. Wootters. Evolution without evolution: Dynamics described by stationary observables. Phys. Rev. D, 27(12):2885–2892, 1983.

- Itamar Pitowsky. Quantum Probability—Quantum Logic. Springer, Berlin, 1991.

- B. S. Tsirelson. Quantum generalizations of bell’s inequality. Lett. Math. Phys., 4:93–100, 1980.

- K. Osterwalder and R. Schrader. Axioms for euclidean green’s functions. Commun. Math. Phys., 31(2):83–112, 1973.

- Steven Weinberg. The Quantum Theory of Fields, Volume I: Foundations. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Carlo Rovelli. Relational quantum mechanics. Int. J. Theor. Phys., 35(8):1637–1678, 1996.

- Shun-ichi Amari. Differential-Geometrical Methods in Statistics. Springer, 1985.

- Thomas M. Cover and Joy A. Thomas. Elements of Information Theory. Wiley, 2006.

- Juan Maldacena. The large-n limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys., 2:231–252, 1998.

- Shinsei Ryu and Tadashi Takayanagi. Holographic derivation of entanglement entropy from the anti-de sitter space/conformal field theory correspondence. Phys. Rev. Lett., 96(18):181602, 2006.

- Sougato Bose, Anupam Mazumdar, Gavin W. Morley, Hendrik Ulbricht, Marko Toro, Mauro Paternostro, Andrew A. Geraci, Peter F. Barker, M. S. Kim, and Gerard Milburn. Spin entanglement witness for quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett., 119(24):240401, 2017.

- Chiara Marletto and Vlatko Vedral. Gravitationally induced entanglement between two massive particles is sufficient evidence of quantum effects in gravity. Phys. Rev. Lett., 119(24):240402, 2017.

- S. W. Hawking and W. Israel, editors. General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1979.

- G. W. Gibbons and S. W. Hawking, editors. Euclidean Quantum Gravity. World Scientific, Singapore, 1993.

| 1 |

More general relational-frame constructions can be obtained when exact factorization fails. |

| 2 |

This Wick rotation formally invokes the Osterwalder–Schrader axioms (reflection positivity, Euclidean invariance, symmetry, cluster decomposition) to ensure a unique analytic continuation from Euclidean correlators to Lorentzian Green’s functions [ 13, 14]. In physically relevant examples, e.g. ground states of gapped local Hamiltonians or KMS thermal states, the Hamiltonian’s spectral gap and thermal KMS condition guarantee holomorphy in a strip around the real axis and exponential decay at large imaginary-time separations, so that the transfer matrix converges and the Wick rotation is well-defined. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).