Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

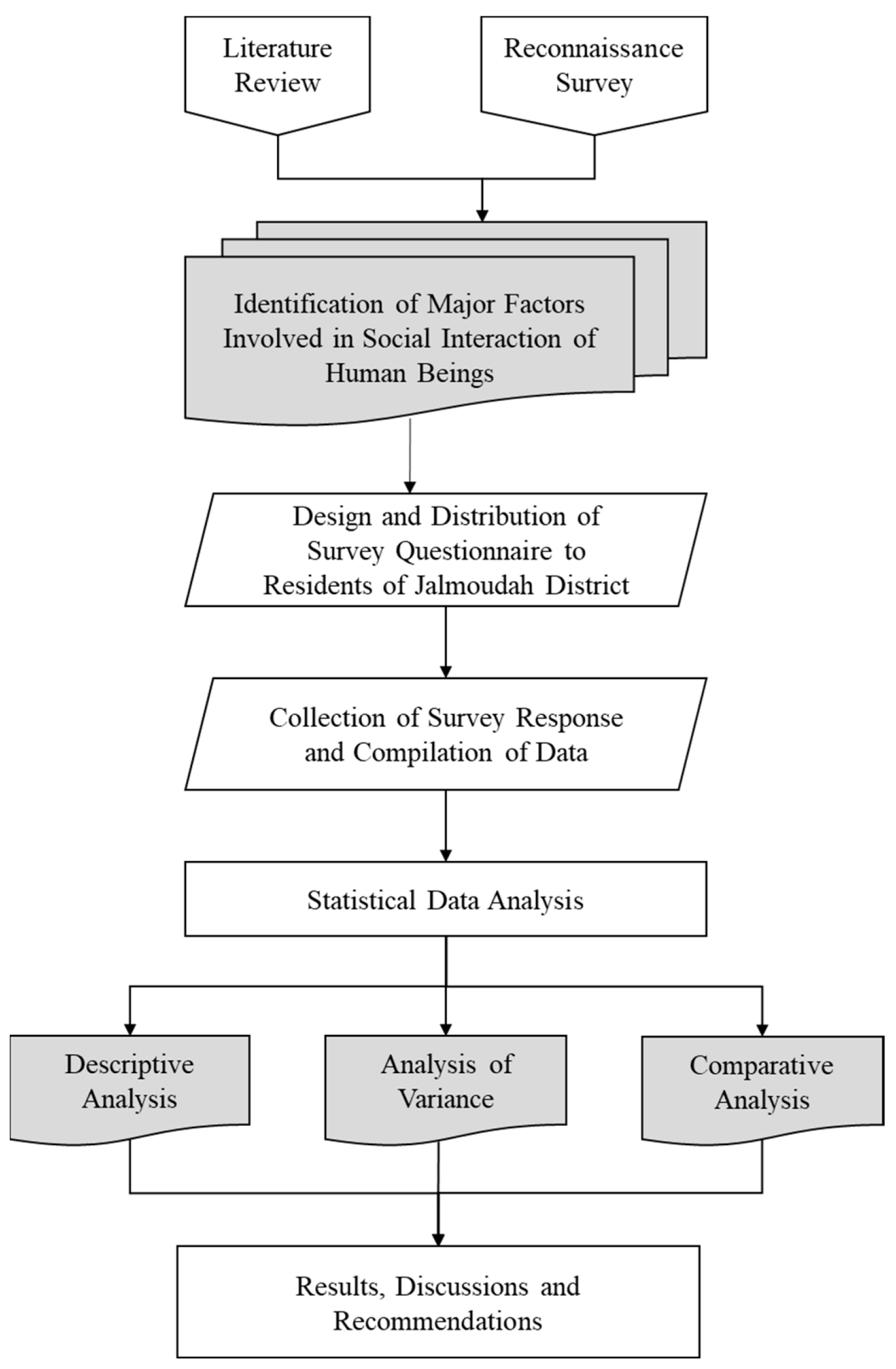

2. Materials and Methods

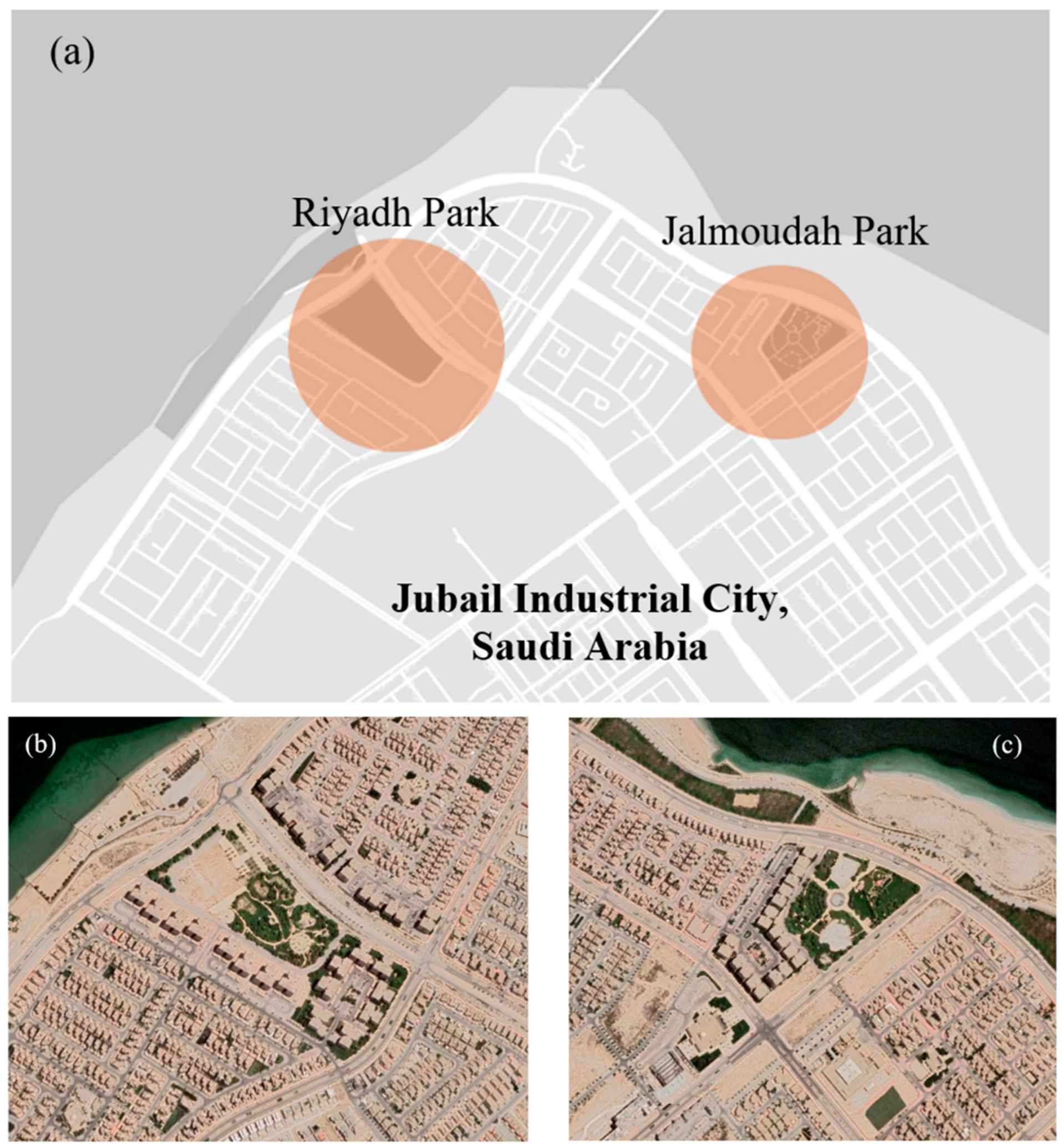

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3. Structure of Survey Questionnaire

3. Results and Discussion

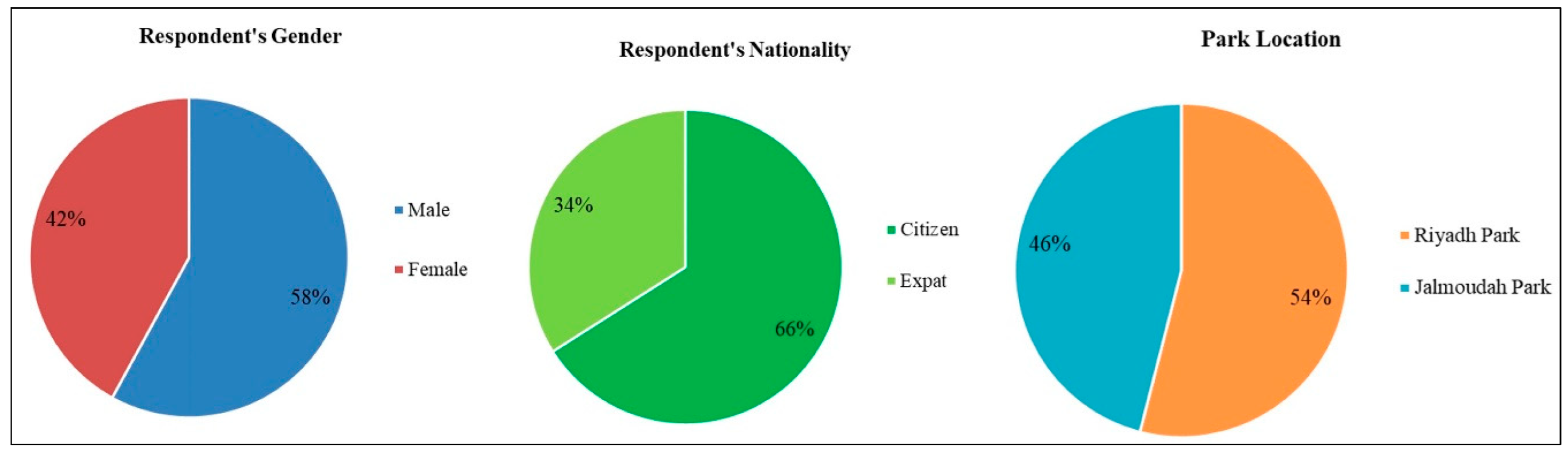

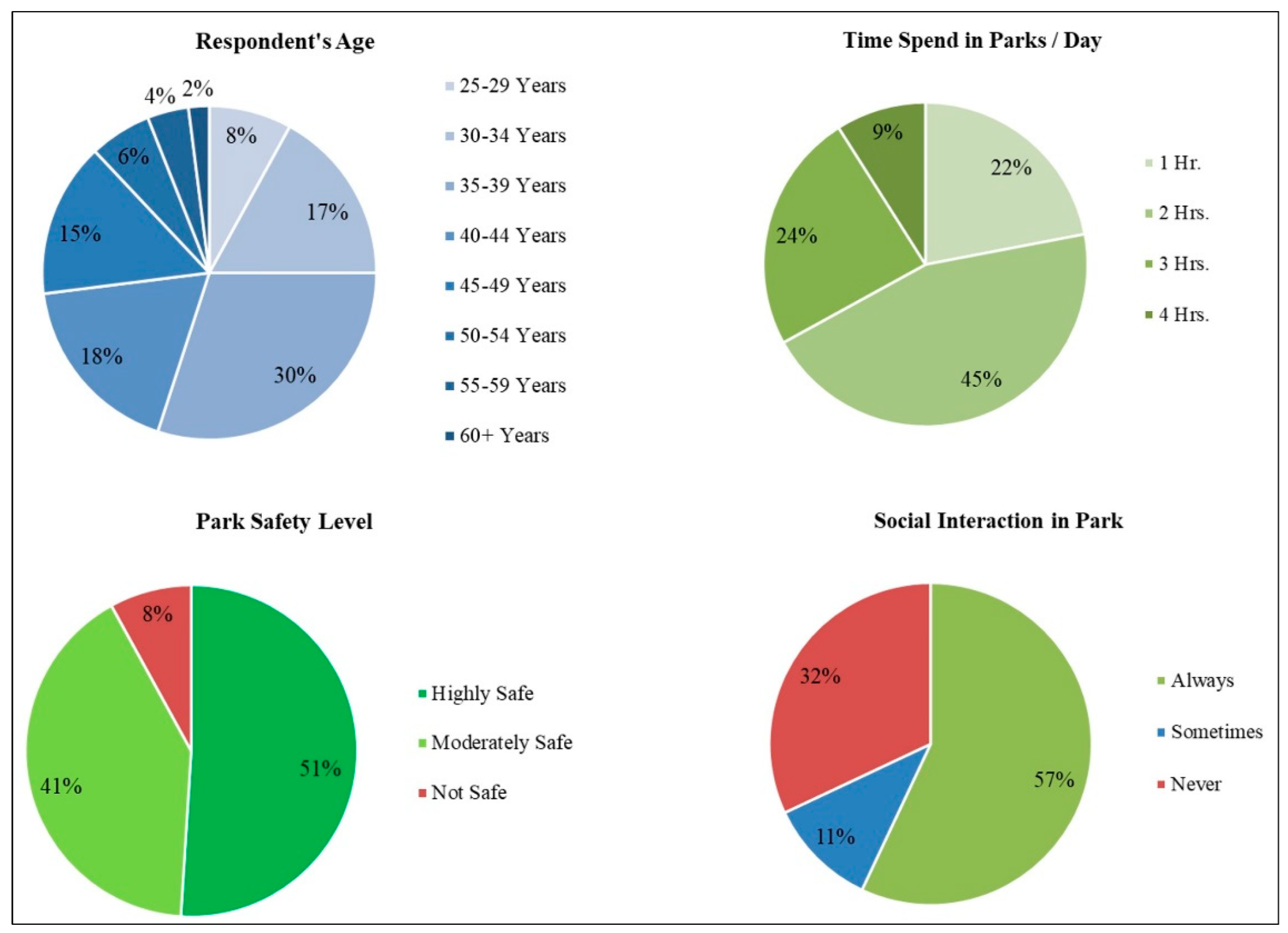

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

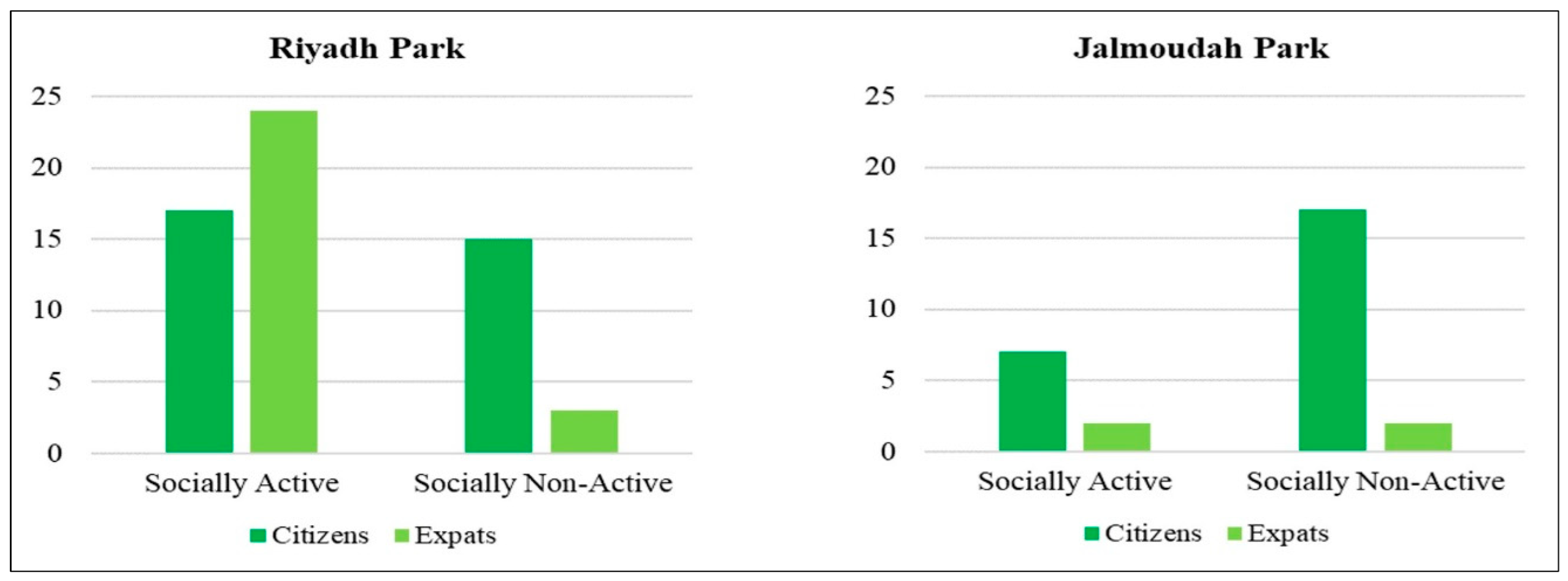

3.3. Comparative Analysis

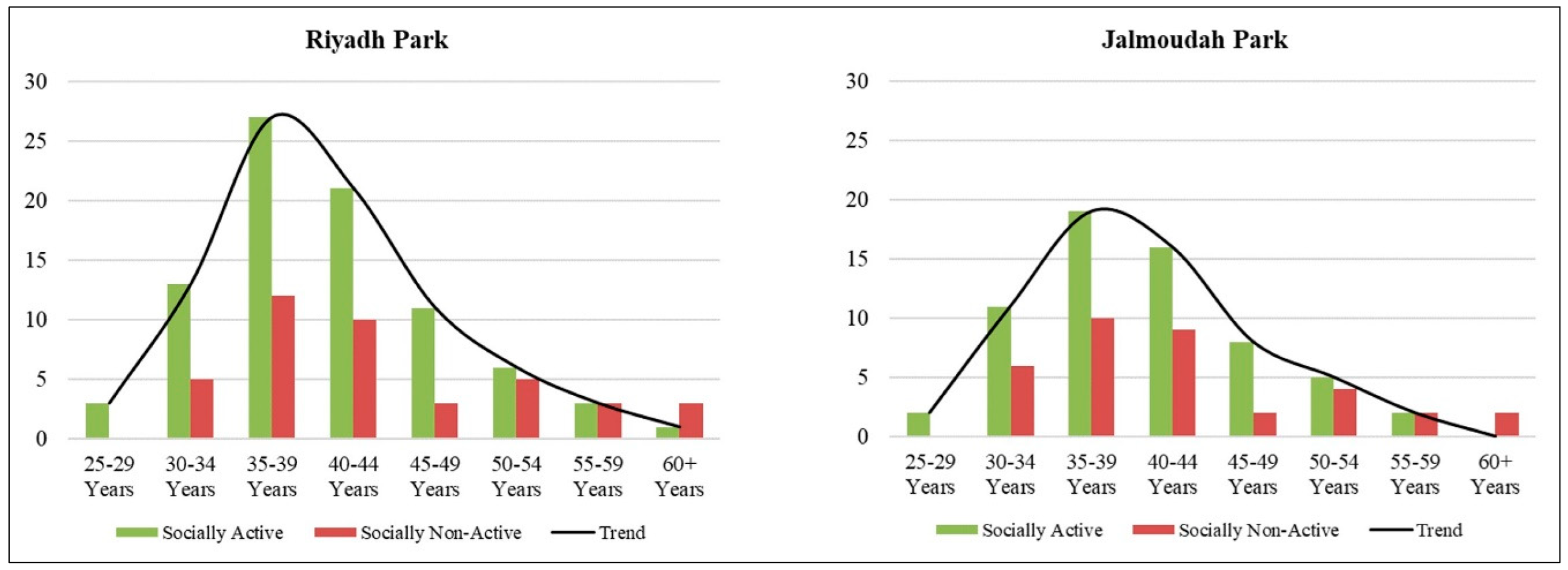

3.3.1. Relationship of Age with Other Variables

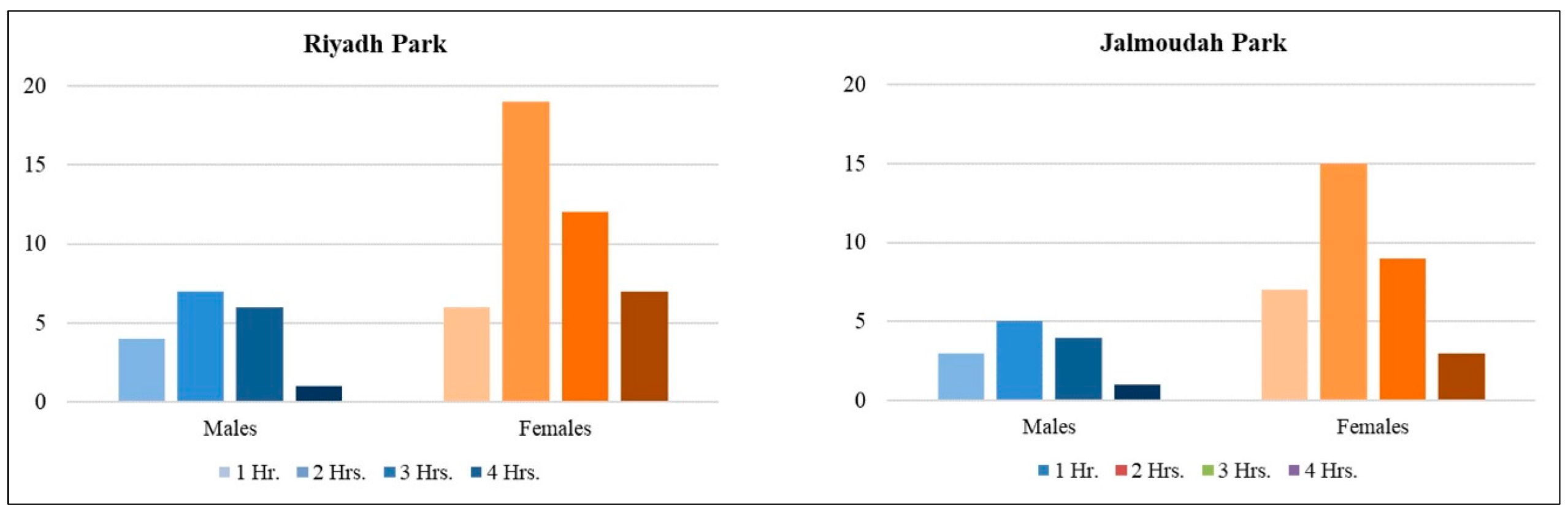

3.3.2. Relationship of Gender with Other Variables

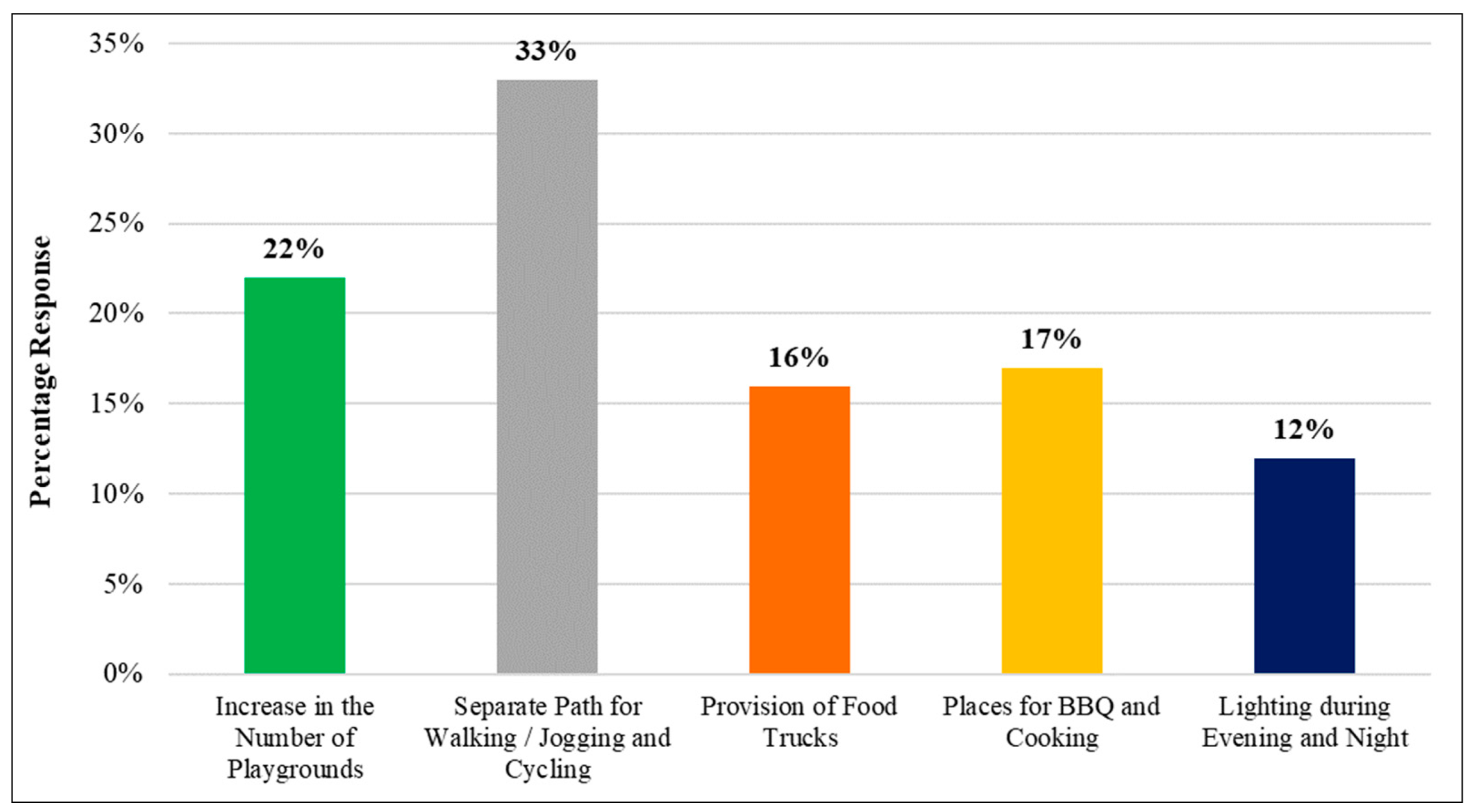

3.3.3. Opinion on Facilities in Parks

3.3.4. Opinion on Facilities in Parks

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Catalani, Anna. (2018). Cities’ Identity Through Architecture and Arts. Routledge. CRC Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1476790/cities-identity-through-architecture-and-arts-proceedings-of-the-international-conference-on-cities-identity-through-architecture-and-arts-citaa-2017-may-1113-2017-cairo-egypt-pdf.

- Rădulescu Sorana. (2017). Interior Public Spaces. Addressing the Inside-Outside Interface — Graz University of Technology. SITA - Studii de Istoria Și Teoria Arhitecturii. https://graz.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/interior-public-spaces-addressing-the-inside-outside-interface.

- Maniruzzaman, K. M., Alqahtany, A., Abou-Korin, A., & Al-Shihri, F. S. (2021). An analysis of residents’ satisfaction with attributes of urban parks in Dammam city, Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 12(3), 3365-3374.

- Alqahtany, A., & Jamil, R. (2022). Evaluation of Educational Strategies in the Design Process of Infrastructure for a Healthy Sustainable Housing Community. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 13(4), 101665.

- Alnaim, A., Dano, U. L., & Alqahtany, A. M. (2025). Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Recreational Parks in Residential Neighborhoods: A Case Study of the Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia.

- Zhang, R., Sun, F., Shen, Y., Peng, S., & Che, Y. (2021). Accessibility of urban park benefits with different spatial coverage: Spatial and social inequity. Applied Geography 135: 102555.

- Munet-Vilaró, F., Chase, S. M., & Echeverria, S. (2018). Parks as Social and Cultural Spaces Among U.S.- and Foreign-Born Latinas. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(10), 1434–1451. [CrossRef]

- Perez, L. G., Arredondo, E. M., McKenzie, T. L., Holguin, M., Elder, J. P., & Ayala, G. X. (2015). Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Depressive Symptoms Among Latinos: Does Use of Community Resources for Physical Activity Matter? Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 12(10), 1361–1368. [CrossRef]

- Otero Peña, J. E., Kodali, H., Ferris, E., Wyka, K., Low, S., Evenson, K. R., Dorn, J. M., Thorpe, L. E., & Huang, T. T. K. (2021). The Role of the Physical and Social Environment in Observed and Self-Reported Park Use in Low-Income Neighborhoods in New York City. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mani, M., Hosseini, S. M., & Ramayah, T. (2012). Parks as business opportunities and development strategies. Business Strategy Series, 13(2), 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, P. A., Lopes, C. S., da Silveira, I. H., Faerstein, E., & Junger, W. L. (2019). Is living near green areas beneficial to mental health? Results of the Pró-Saúde Study. Revista de Saúde Pública, 53, 75–75. [CrossRef]

- Rio, C. J., & Saligan, L. N. (2023). Understanding physical activity from a cultural-contextual lens. Frontiers in Public Health, 11. [CrossRef]

- Turna, N., & Bhandari, H. (2022). Role of Parks as Recreational Spaces at Neighborhood Level in Indian Cities. ECS Transactions, 107(1), 8685–8694. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Wang, F., Chen, L., & Zhang, W. (2021). Perceived urban green and residents’ health in Beijing. SSM - Population Health, 14, 100790. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., van Dijk, T., Tang, J., & van den Berg, A. E. (2015). Green Space Attachment and Health: A Comparative Study in Two Urban Neighborhoods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2015, Vol. 12, Pages 14342-14363, 12(11), 14342–14363. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani Mehrian, M., Manouchehri Miandoab, A., Abedini, A., & Aram, F. (2022). The Impact of Inefficient Urban Growth on Spatial Inequality of Urban Green Resources (Case Study: Urmia City). Resources 2022, Vol. 11, Page 62, 11(7), 62. [CrossRef]

- Raap, S., Knibbe, M., & Horstman, K. (2022). Clean Spaces, Community Building, and Urban Stage: the Coproduction of Health and Parks in Low-Income Neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Health, 99(4), 680–687. [CrossRef]

- Vaeztavakoli, A., Lak, A., & Yigitcanlar, T. (2018). Blue and Green Spaces as Therapeutic Landscapes: Health Effects of Urban Water Canal Areas of Isfahan. Sustainability, 10(11). [CrossRef]

- Ulset, V., Venter, Z., Charlott, E., & Nordbø, A. (2023). Increased nationwide recreational mobility in green spaces in Norway during the Covid-19 pandemic. [CrossRef]

- Moulay, A., & Ujang, N. (2016). LEGIBILITY OF NEIGHBORHOOD PARKS AND ITS IMPACT ON SOCIAL INTERACTION IN A PLANNED RESIDENTIAL AREA. In International Journal of Architectural Research Amine Moulay, Norsidah Ujang Archnet, Vol. 10.

- Sun, Y., Tan, S., He, Q., & Shen, J. (2022). Influence Mechanisms of Community Sports Parks to Enhance Social Interaction: A Bayesian Belief Network Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, Vol. 19, Page 1466, 19(3), 1466. [CrossRef]

- Cui, H., Maliki, N. Z., & Wang, Y. (2024). The Role of Urban Parks in Promoting Social Interaction of Older Adults in China. Sustainability 2024, Vol. 16, Page 2088, 16(5), 2088. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. A., Han, B., Williamson, S., Nagel, C., McKenzie, T. L., Evenson, K. R., & Harnik, P. (2020). Playground features and physical activity in U.S. neighborhood parks. Preventive Medicine 131: 105945.

- Chen, S., Sleipness, O., Christensen, K., Yang, B., Park, K., Knowles, R., Yang, Z., & Wang, H. (2024). Exploring associations between social interaction and urban park attributes: Design guideline for both overall and separate park quality enhancement. Cities, 145, 104714. [CrossRef]

- Poppe, L., Van Dyck, D., De Keyser, E., Van Puyvelde, A., Veitch, J., & Deforche, B. (2023). The impact of renewal of an urban park in Belgium on park use, park-based physical activity, and social interaction: A natural experiment. Cities, 140, 104428. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Kang, J. (2023). Natural sounds can encourage social interactions in urban parks. Landscape and Urban Planning, 239, 104870. [CrossRef]

- Leung, A. K. yee, Maddux, W. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Chiu, C. yue. (2008). Multicultural Experience Enhances Creativity: The When and How. American Psychologist, 63(3), 169–181. [CrossRef]

- Jayadi, K., Abduh, A., & Basri, M. (2022). A meta-analysis of multicultural education paradigm in Indonesia. Heliyon, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Sudigdo, A., & Pamungkas, O. Y. (2022). Multiculturalism in Children’s Literature: A Study of a Collection of Poems by Elementary School Students in Yogyakarta. Daengku: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Innovation, 2(3), 266–278. [CrossRef]

- Mena, J. A., & Rogers, M. R. (2017). Factors associated with multicultural teaching competence: Social justice orientation and multicultural environment. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 11(2), 61–68. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C. A., Cohen, D. A., & Han, B. (2018a). How Do Racial/Ethnic Groups Differ in Their Use of Neighborhood Parks? Findings from the National Study of Neighborhood Parks. Journal of Urban Health 95(5): 739–749.

- Wolch, J., Wilson, J. P., & Fehrenbach, J. (2005). Parks and park funding in Los Angeles: An equity-mapping analysis. Urban Geography 26(1): 4–35.

- Peters, K., Elands, B., & Buijs, A. (2010). Social interactions in urban parks: Stimulating social cohesion? Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 9(2): 93–100.

- Whiting, J. W., Larson, L. R., Green, G. T., & Kralowec, C. (2017). Outdoor recreation motivation and site preferences across diverse racial/ethnic groups: A case study of Georgia state parks. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 18: 10–21.

- Vaughan, C. A., Cohen, D. A., & Han, B. (2018b). How Do Racial/Ethnic Groups Differ in Their Use of Neighborhood Parks? Findings from the National Study of Neighborhood Parks. Journal of Urban Health 95(5): 739–749.

- Dade, M. C., Mitchell, M. G. E., Brown, G., & Rhodes, J. R. (2020). The effects of urban greenspace characteristics and socio-demographics vary among cultural ecosystem services. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, Vol. 49.

- Rivera, E., Veitch, J., Loh, V. H. Y., Salmon, J., Cerin, E., Mavoa, S., Villanueva, K., & Timperio, A. (2022). Outdoor public recreation spaces and social connectedness among adolescents. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V., & Bamkole, O. (2019). The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, Vol. 16, Page 452, 16(3), 452. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T., Kerr, J., & Schipperijn, J. (2019). Associations between Neighborhood Open Space Features and Walking and Social Interaction in Older Adults—A Mixed Methods Study. Geriatrics 4(3): 41.

- Rivera, E., Timperio, A., Loh, V. H., Deforche, B., & Veitch, J. (2021). Important park features for encouraging park visitation, physical activity and social interaction among adolescents: A conjoint analysis. Health & Place 70: 102617.

- Powers, S. L., Webster, N., Agans, J. P., Graefe, A. R., & Mowen, A. J. (2022). The power of parks: How interracial contact in urban parks can support prejudice reduction, interracial trust, and civic engagement for social justice. Cities, 131, 104032. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, I. T., Benita, F., & Tunçer, B. (2022). Effects of urban park spatial characteristics on visitor density and diversity: A geolocated social media approach. Landscape and Urban Planning, 226, 104514. [CrossRef]

- RCJ (2023). Jubail Industrial City Guide. < https://rcj.gov.sa/JicGuide/Beach.html >.

| Category | Options | Type |

| Mode of Transport | Bus, Car, Bicycle / Scooter, Walking | Check Box |

| Purpose of Visit | Relaxation, Spending time with the family, Kids Entertainment and Activities, Physical Activities, Working Out / Walk, Neighbors Gathering, Meeting New People | |

| Preference of Season | Summer, Autumn, Winter, Spring | |

| Time of Visit | Morning, Afternoon, Evening | |

| Duration of Stay | 1, 2, 3, or 4 Hrs. | |

| Company | Alone, Friends, Family | |

| Frequency of Visit | Daily, Once / Twice / Thrice a Week, Rarely | Multiple Choice |

| Number of Times Meeting in a Group | Daily, Weekly, Bi-Weekly, Monthly, Never | |

| Meeting with Other Nationalities | Yes, No |

| Category | Options | Type |

| Facilities for people with special needs (e.g. ramps, parking, toilets, sitting areas) | 1 to 5 | Likert Scale |

| Level of Facilities in Parks | Poor, Good, Very Good | Multiple Choice |

| Level of Satisfaction | 1 to 5 | Likert Scale |

| Required Improvements | Increase in the number of playgrounds, Separate Path for Walking / Jogging and Cycling, Provision of Food Trucks, Places for BBQ and Cooking, Lighting during Evening and Night | Check box |

| Safety of Children and People | 1 to 5 | Likert Scale |

| Safety Factors Required in Park | Text | Open Ended Question |

| Parameter | Response Mean () | Average Value | Response Standard Deviation (σ) |

| Age Bracket | 3.29 / 5 | 39 Years | 0.82 |

| Time Spend in Parks / Day | 2.63 / 4 | 2 – 3 Hrs. | 0.89 |

| Park Safety Level | 4.27 / 5 | Highly to Moderately Safe | 0.90 |

| Social Interaction in Park | 2.18 / 4 | Always to Sometimes | 0.49 |

| ANOVA | |||||||

| Sources | SS | df | F | P value | F crit | RMSSE | Omega Sq |

| Between Groups | 537.2943 | 6 | 194.4529 | 9.8E-135 | 2.114359 | 1.530623 | 0.666421 |

| Within Groups | 264.3373 | 574 | |||||

| Total | 801.6317 | 580 |

| group 1 | group 2 | mean | std err | q-stat | lower | upper | p-value | mean-crit | Cohen d |

| Age | Gender | 1.7470 | 0.0745 | 23.4534 | 1.4364 | 2.0576 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 2.5743 |

| Age | Nationality | 1.6265 | 0.0745 | 21.8359 | 1.3159 | 1.9371 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 2.3968 |

| Age | Park Location | 2.0000 | 0.0745 | 26.8501 | 1.6894 | 2.3106 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 2.9472 |

| Age | Social Interaction | 1.8795 | 0.0745 | 25.2326 | 1.5689 | 2.1901 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 2.7696 |

| Age | Time Spent | 1.0723 | 0.0745 | 14.3955 | 0.7617 | 1.3829 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 1.5801 |

| Age | Safety | 0.6747 | 0.0745 | 9.0579 | 0.3641 | 0.9853 | 6.57E-09 | 0.3106 | 0.9942 |

| Gender | Nationality | 0.1205 | 0.0745 | 1.6175 | -0.1901 | 0.4311 | 0.914228 | 0.3106 | 0.1775 |

| Gender | Park Location | 0.2530 | 0.0745 | 3.3967 | -0.0576 | 0.5636 | 0.199588 | 0.3106 | 0.3728 |

| Gender | Social Interaction | 0.1325 | 0.0745 | 1.7792 | -0.1781 | 0.4431 | 0.870594 | 0.3106 | 0.1953 |

| Gender | Time Spent | 0.6747 | 0.0745 | 9.0579 | 0.3641 | 0.9853 | 6.57E-09 | 0.3106 | 0.9942 |

| Gender | Safety | 2.4217 | 0.0745 | 32.5113 | 2.1111 | 2.7323 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 3.5686 |

| Nationality | Park Location | 0.3735 | 0.0745 | 5.0142 | 0.0629 | 0.6841 | 0.007692 | 0.3106 | 0.5504 |

| Nationality | Social Interaction | 0.2530 | 0.0745 | 3.3967 | -0.0576 | 0.5636 | 0.199588 | 0.3106 | 0.3728 |

| Nationality | Time Spent | 0.5542 | 0.0745 | 7.4404 | 0.2436 | 0.8648 | 4.2E-06 | 0.3106 | 0.8167 |

| Nationality | Safety | 2.3012 | 0.0745 | 30.8938 | 1.9906 | 2.6118 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 3.3910 |

| Park Location | Social Interaction | 0.1205 | 0.0745 | 1.6175 | -0.1901 | 0.4311 | 0.914228 | 0.3106 | 0.1775 |

| Park Location | Time Spent | 0.9277 | 0.0745 | 12.4546 | 0.6171 | 1.2383 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 1.3671 |

| Park Location | Safety | 2.6747 | 0.0745 | 35.9079 | 2.3641 | 2.9853 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 3.9414 |

| Social Interaction | Time Spent | 0.8072 | 0.0745 | 10.8371 | 0.4966 | 1.1178 | 1.61E-12 | 0.3106 | 1.1895 |

| Social Interaction | Safety | 2.5542 | 0.0745 | 34.2905 | 2.2436 | 2.8648 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 3.7639 |

| Time Spent | Safety | 1.7470 | 0.0745 | 23.4534 | 1.4364 | 2.0576 | -2.2E-14 | 0.3106 | 2.5743 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).