1. Introduction

Numerous literature reviews reveal a lack of consensus over the definition of social interaction. The subsequent delineates some fundamental principles of social interaction. Social interaction defines as the community actions undertaken by neighbors, such as borrowing or lending equipment, informal visits, and soliciting help during emergencies [

1]. It contends that local social connections are vital for the social sustainability of urban communities, since they bolster residents' feeling of community and safety in metropolitan environments [

2]. In addition, social interaction is defined as the occurrence of spoken or non-verbal exchanges between two or more people [

3]. Moreover, social interaction refers to the ongoing informal discourse between at least two individuals, enabling access to social and economic resources and support for a resident [

4].

Consequently, based on the preceding literature studies on social interaction, the existing literature on social interaction reveals a lack of agreement about its definition, with several interpretations and viewpoints concerning the fundamental concept of social sustainability. The research study examines face-to-face social interactions among people, including all social activities, including conversation.

Several research investigations consistently affirm that social interaction requires a suitable atmosphere for its manifestation. Consequently, extensive research has shown the impact of physical settings on social interactions [

5].

This may be achieved by creating situations and opportunities that promote various types of social connections, from passive to more active engagement [

6]. Furthermore, the physical environment has both direct and indirect effects on social interaction [

5]. Consequently, space may either promote or deter the length of users' stay in an area, hence affecting the likelihood of their interactions.

Moreover, the architectural characteristics of the built environment may affect people’s impressions of a certain area [

7]. The perceived attributes, such as safety, aesthetics, and privacy, subsequently influence individuals' behavior and their choices on the use of space. Consequently, certain features have an indirect impact on interpersonal relationships among individuals. The architectural features of the constructed environment might influence people’s perceptions of a certain region [

7]. The perceived characteristics, including safety, attractiveness, and privacy, consequently, affect a person’s behavior and their spatial choices. Thus, certain traits have an indirect influence on interpersonal interactions. It impacts the psychological accessibility of recreational spaces inside the residential area, hence directly affecting social interaction.

Conversely, certain socio-economic factors have been identified as significantly influencing social interactions within neighborhoods [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Talen (1999) contests the assertions of contemporary urbanism about community, proposing that social and economic uniformity within a neighborhood may have a greater influence on resident interactions [

8]. Moreover, homeownership is an additional factor that may influence social connections among inhabitants. Homeowners exhibit more engagement with neighbors compared to renters [

7].

Prioritizing and implementing interaction design strategies in particular settings is essential to strengthening social relationships in urban environments. Additionally, these areas may be used to successfully address individual sociocultural dynamics [

12]. Furthermore, physical open space is essential for promoting social contact among neighborhood people. Neighborhood parks, for instance, are essential to the growth and enhancement of cities as well as the promotion of social and cultural relations. They serve as venues for social and cultural exchange in addition to being locations where people may enjoy the outdoors [

5]. Meanwhile, local parks provide opportunities for social encounters that might strengthen social bonds, according to [

13].

In the presence of people, open spaces (public and semi-public locations) tend to draw others, who congregate and engage with one another while trying to find a spot in the throng, thereby starting new activities [

14]. The acts that determine the quality of an open space area include observation, perception, and communication [

14]. According to Pooleh and Vali (2014), these spaces improve social connections and meet residents' psychological needs [

15]

The main idea about how physical attributes affect social interaction is that they create opportunities and appropriate settings for different kinds and levels of interaction, from simple passive contacts to deeper social bonds [

6,

16]. In addition to the direct effects of the physical environment on interactions, it also has indirect effects by either facilitating or hindering users' time spent in a space [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. A communal open space's constituents include a variety of elements, including dedicated sitting places, gardens, horse trails, pedestrian walkways, children's play areas, and green space [

14].

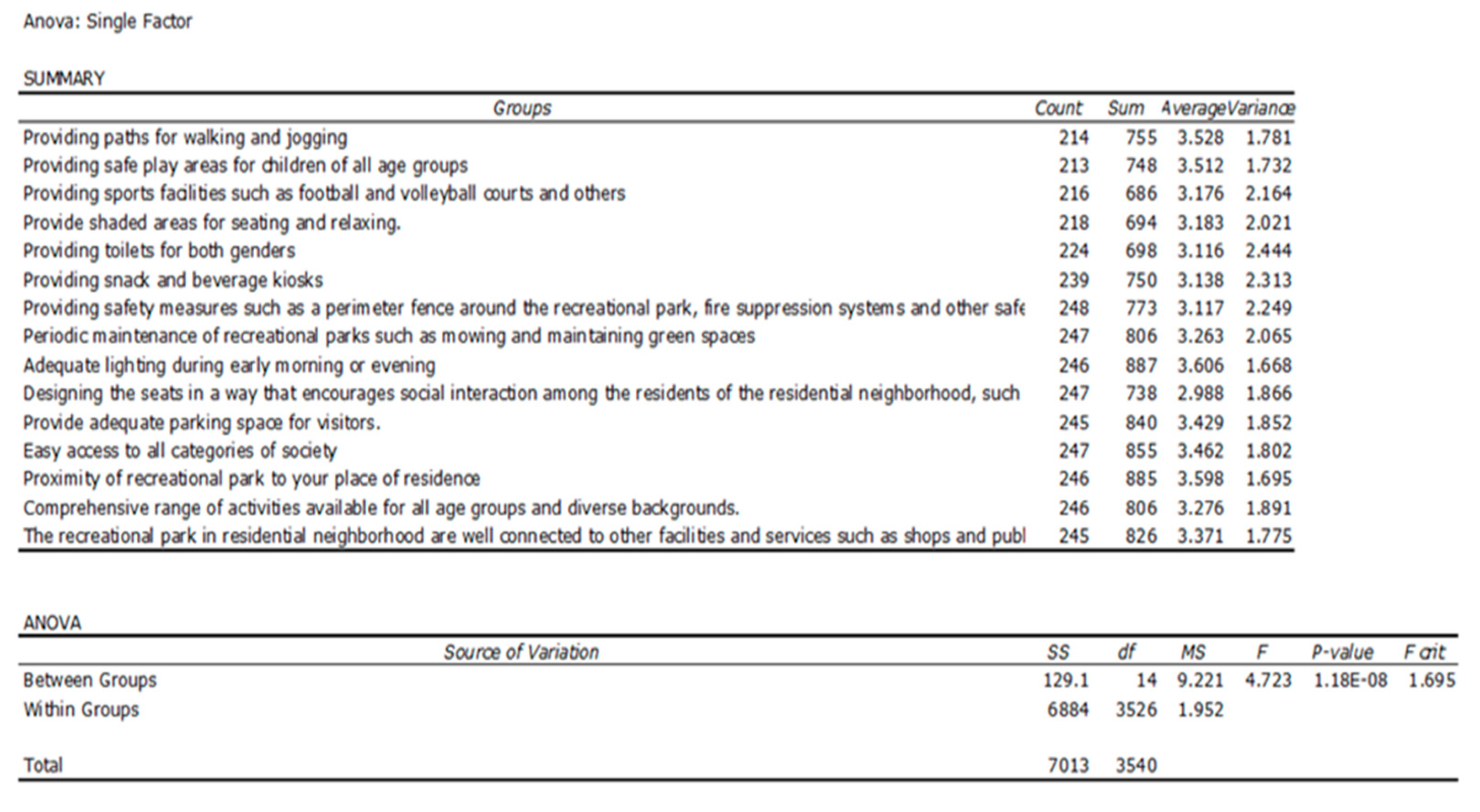

Both the quantity and quality of social interactions between people may be impacted by the built environment in two different ways. First off, certain physical elements, like doors, windows, and walls, have the direct ability to affect how people move and transit inside a place, creating chances for meetings and interactions. Second, people's perceptions of a place may also be influenced by the built environment's physical features [

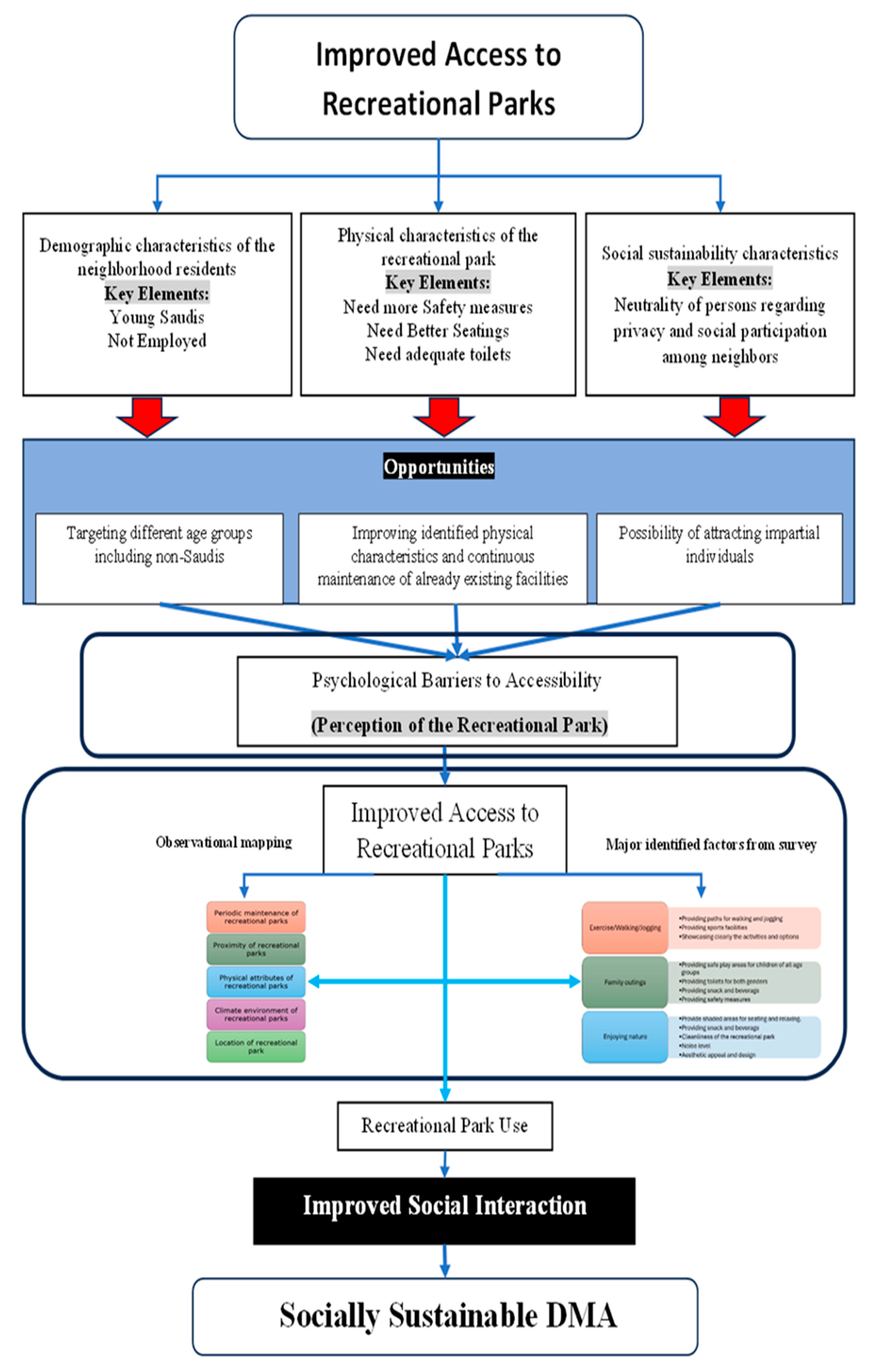

7]. These perceived qualities—like privacy, safety, and beauty—then affect people's behavior and decisions about whether and how to use space. Furthermore, Ewing and Handy (2009) distinguished three categories of attributes—physical aspects, design attributes, and user perception that might impact user behavior in urban planning (Refer to

Figure 1) [

22].

The aforementioned literature studies have demonstrated a direct relationship between open space and social interaction among residents. The research that follows focuses on residential parks as a great location for neighborhood residents to engage in face-to-face social interaction.

Traditionally, park accessibility is described as proximity to parks, suggesting that park locations should minimize travel distance [

23]. In addition to ongoing spatial and cost difficulties, the proximity-based approach does not consistently predict authentic human behavior, such as park use. Various factors related to parks, beyond distance, such as size, location, facilities, the surrounding environment, and various attitudes of the park influence park use [

24,

25,

26].

A widely accepted definition of accessibility in transportation research is 'the ease of accessing any land-use activity from a location using a certain transport system' [

27]. Some writers define it more broadly as the 'potential for opportunities for interaction' [

28] or 'a measure of an individual's freedom to participate in activities within the environment' [

29]. In public health studies, psychological accessibility is notably correlated with the use of community sports facilities [

30]. Thus, accessibility includes the perceptions of the individual ragarding the locations or related activities. Based on the preceding, this study regards recreational park accessibility as a holistic approach for assessing the possibilities for recreational park use. Consequently, this study argues that, unlike traditional research that analyzes park accessibility and usability separately, both concepts should be integrated into a unified conceptual framework. The physical and psychological dimensions of accessibility should be examined as interconnected elements. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) asserts that the relationship between the physical environment and actual action is mediated by psychological factors [

31,

32].

Psychological accessibility pertains to people’s perceptions and evaluations of their environmental contexts [

33]. Similar to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Fishbein and Ajzen's Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) asserts that the interaction of attitudes and subjective norms affects behavioral intentions, ultimately leading to intentional behavior. Psychological accessibility and intention may act as an internal motivating process for attitudes, functioning as a psychological variable and creating a state of readiness for behavior and experience.

Several research studies demonstrate a substantial correlation between the perception of park proximity or availability and park use [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Factors that enhance park utilization comprise the positive perception of park quality, which include safety [

37,

38,

39], amenities [

40,

41] and opportunities for social interaction [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Furthermore, several studies suggest that perceptions of neighborhood safety concerning crime and traffic, together with street connectivity and amenities, affect the frequency of park use [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

The relationship between physical environments and park use is shaped by environmental perception. According to Park (2017), psychological accessibility is divided into three main classifications: perceived distance, perception of the park quality and perception of neighborhood environment [

45]. In addition, according to Park (2017), the primary elements influencing perceived distance to the park are the perception of accessibility and the park's availability [

45]. The second category pertains to the perception of park quality, which encompasses safety, attractiveness, cleanliness, maintenance, amenities, activities, and the social environment [

45]. Although the perceived park quality includes safety, attractiveness, upkeep, facilities, and social environment, it may also integrate other factors depending on the objectives or setting of the study. Finally, the perception of the neighborhood environment pertains to features such as safety from crime and traffic, beauty and cleanliness, walkability, and the availability of destinations (e.g., shops, restaurants, grocery stores, public amenities).

Perception varies according to individual and socio-economic characteristics, which may affect the forecasting of park use. Individuals face unique constraints and have varying perceptions of space. Therefore, if a park does not satisfy the preferences of various user groups, its use would decline. The sociodemographic parameters relevant to park use include age group [

46,

47], gender [

48,

49,

50] and socioeconomic status [

50,

51].

In summary, conventional research on park accessibility reliant on physical accessibility demonstrates considerable limitations, as physical accessibility alone does not predict park usage. Therefore, physical accessibility must be supplemented with evaluations of perceived accessibility (Psychological Accessibility). Consequently, improving Park safety, appeal, cleanliness, proximity, and the diversity of activities for all societal groups may reduce the psychological barriers to accessibility which leads to increase the number of visitors and build vibrant places. Moreover, the findings of this study may aid policymakers and park designers in enhancing park accessibility through alternative tactics guided by psychological considerations.

This study aims to develop a framework for improving social interaction through enhanced access to recreational parks in the residential neighborhoods in the Saudi context. The study is organized into the following sections.

Section 2 describes the methodology of data collection and analysis.

Section 3 aims to discuss the key findings of the study. The study concludes with

Section 4 that aims to summarize and suggest some recommendations.

3. Results and Discussion

This section is divided into two main parts. The first part examines the behavior of end users in the recreational parks of the two selected case studies in each city of DMA to discover and understand the incentives and obstacles influencing the accessibility of the user visits. The observations were placed in November 2024 - February 2025, a period characterized by mild weather in DMA. The observations were conducted on two different occasions: once during a weekday and once on a weekend, at three distinct times: in the morning from 6:00 to 8:00 AM on weekdays and from 8:00 to 11:30 AM on weekends. The reason behind selection of two various times refer to the social life of the Saudi context. While, in the afternoon from 3:00 to 6:00 PM, and in the evening from 7:00 to 10:00 PM. The number of individuals using the location was assessed during a 15 to 20-minute observation session on both weekdays and weekends and recorded in the checklists. During the observation periods, the temperatures were comfortable with a low of 18°C and high up to 35°C. The weather was cold and warm on some days save for a limited number of days characterized by hot and dry weather. The observation spots were selected carefully to provide optimal visibility. The case studies are examined and presented. Initially, to count the individuals using the observed community locations (Recreational parks) are recorded; subsequently, the behaviors and activities of users are documented, including their categorization as male, female, or children (under 18 years old).

The second part is concentrated on the end user’s questionnaire survey where it aims to provide an analysis of the administered questionnaire survey. The survey sought to get insights into end users, satisfaction, perceptions and experiences about recreational parks in residential areas in DMA. Descriptive and cross-tabulation analyses were performed on the questionnaire variables. Furthermore, statistical tests were used to ascertain any dependence among the categorical variables associated with each posed issue.

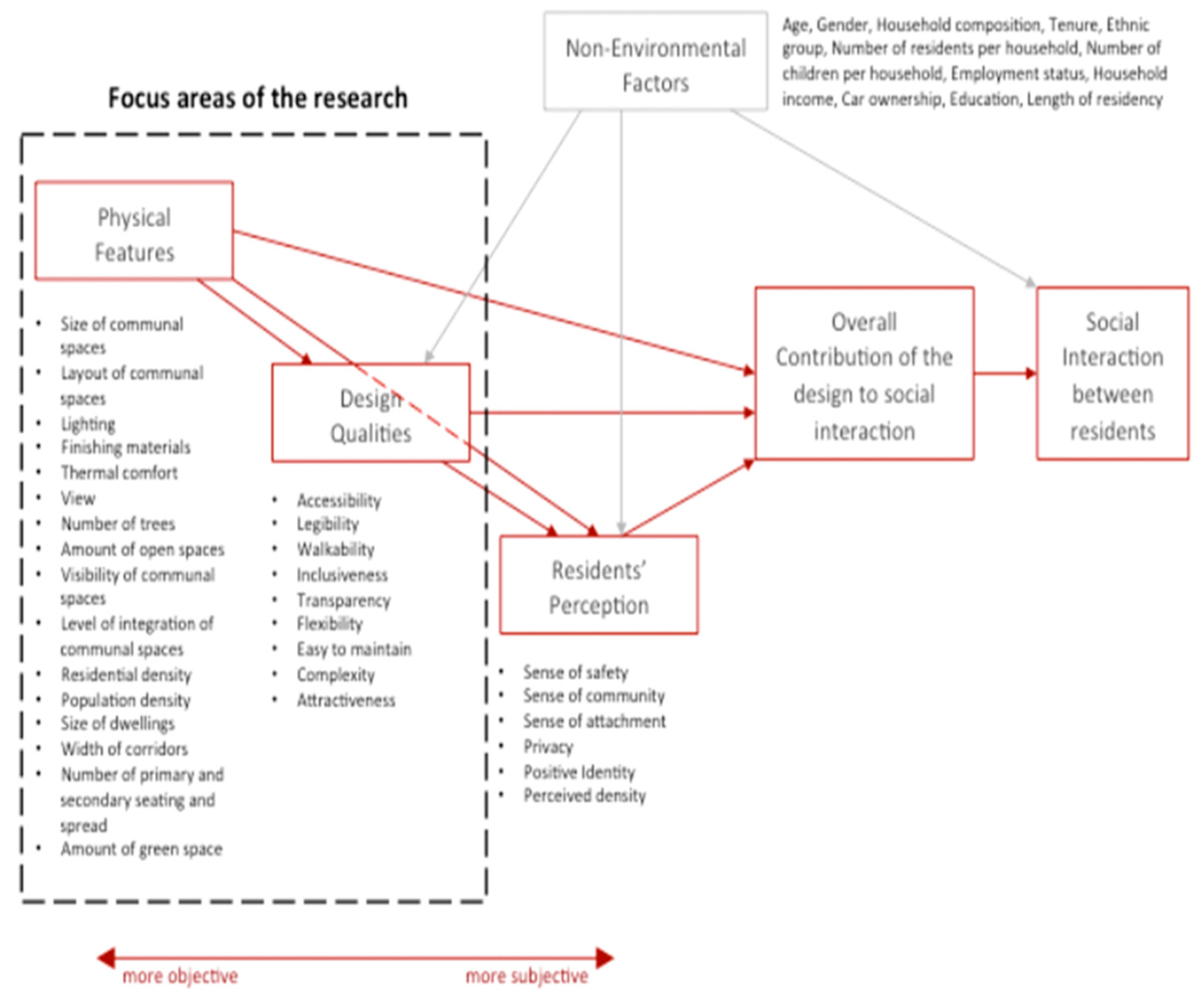

Firstly, the selection criteria for recreational parks for conducting the observational behavioural mapping have been established by convenience, particularly accessibility. The accessibility of the recreational park and the documentation of observational mapping through photography were key factors for the selection of the recreational parks. Moreover, the perceived importance within the hierarchy of recreational parks in the Saudi context. The location of the selected recreational parks corresponds with the condition of neighborhood recreational parks in Saudi Arabia, which range from 1000 m to 10,000 m. According to Yin (2014), the selected case studies may include either single-case or multiple-case approaches [

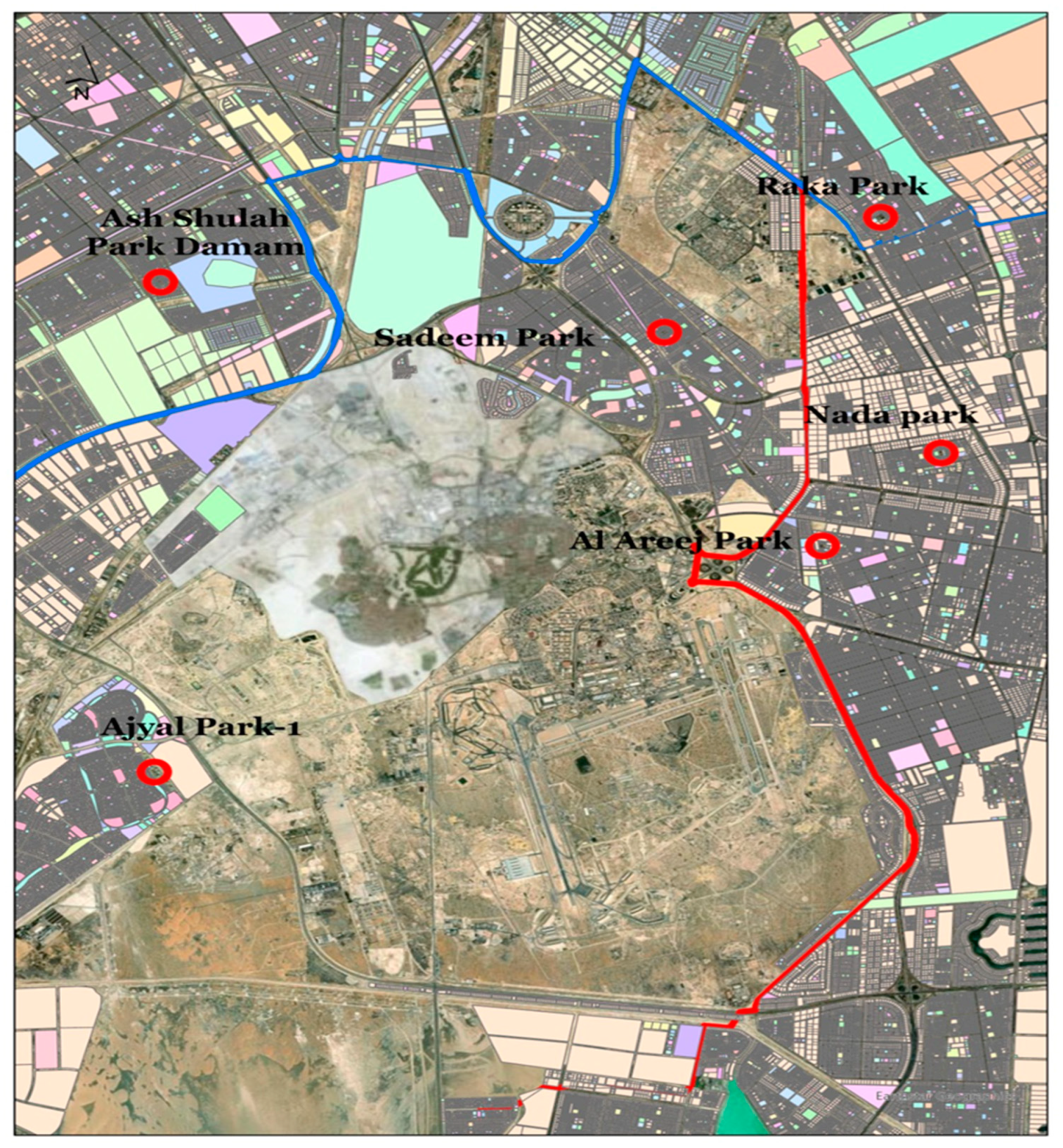

60]. This study used two case studies (Neighborhood Recreational Parks) in each city of the DMA (Dammam-Khobar-Dhahran) to improve the dependability of results drawn from the observational behavioral mapping approach. The following

Figure 3 represents the location of each selected recreational park in DMA.

The following delineates the observational mapping analysis of the three case studies in Dammam, Khobar, and Dhahran.

Case Study 1: Khobar City

The observational mapping in Khobar City was conducted in two various recreational parks in two different residential neighborhoods. The selected recreational parks as follows, (1) Areej Park and (2) Nada Park.

- 1.

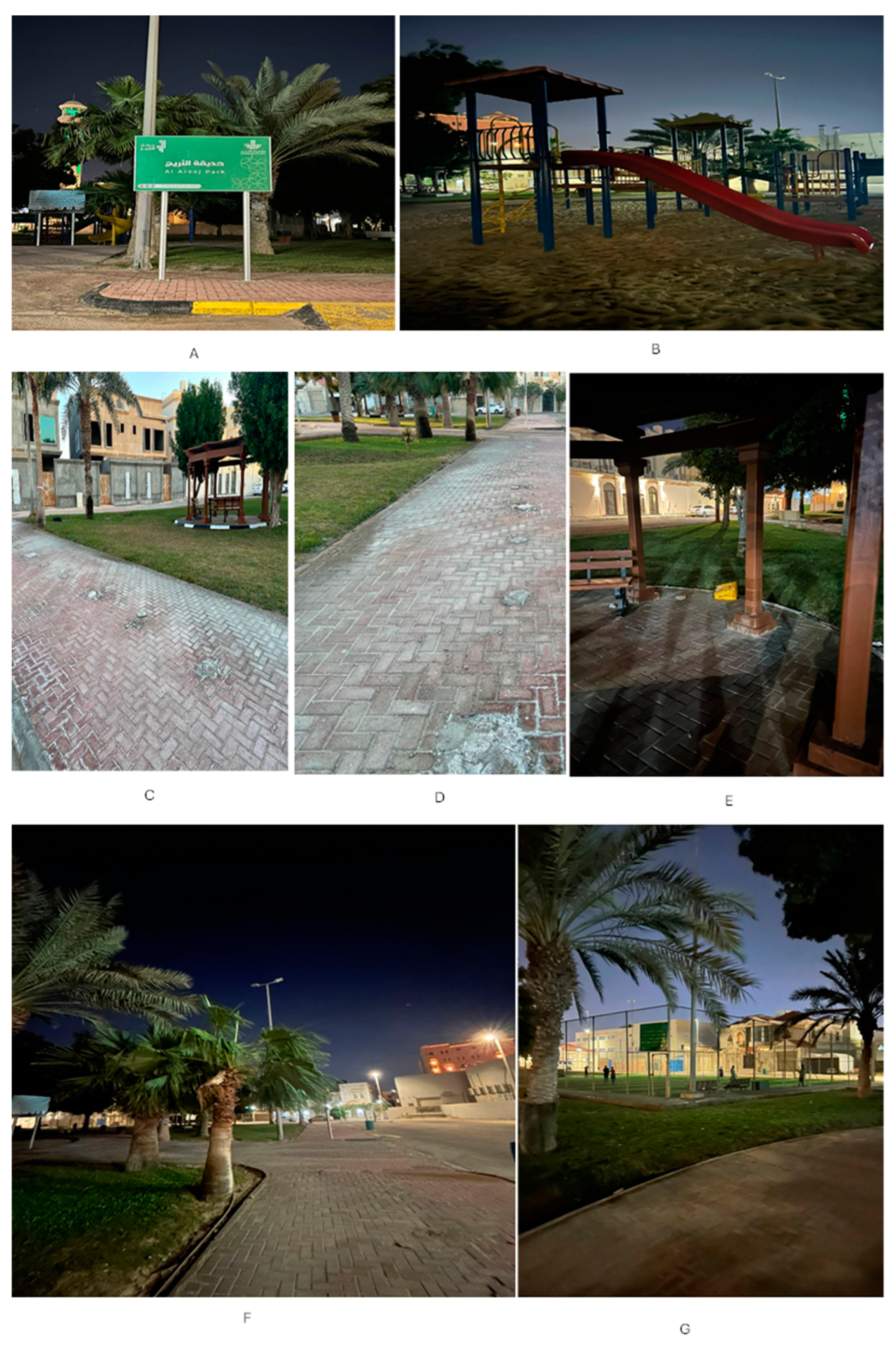

Areej Park:

Areej Park is situated in Khobar City, specifically in the Al Ulaya neighborhood, with an estimated area of 3,576 m² and is encircled by single family housing and apartment buildings.

Figure 4 illustrates that Areej Park offers shaded seating areas suitable for relaxation as well as formal and casual social meetings. Moreover, a substantial football field serves as an attraction for the youngsters in the residential area. Additionally, there exists a pathway around the park for exercise such as walking and running, accompanied by extensive green areas for visitors. The park provides parking spaces which enhance the physical accessibility of the park. Additionally, the park has a designated play area for youngsters. The playground space is very restricted and fails to accommodate diverse age groups.

The observational mapping process has shown that the park experiences insufficient periodic maintenance regarding the jogging track and illumination. The jogging track around the park is irregular, resulting in falls and other sad incidents. Moreover, the park experiences complete darkness at night, thus compromising the sense of security for its visitors. Consequently, the significance of lighting in parks, particularly during the nighttime, directly influences people’s perceptions of safety and security which may influence the psychological accessibility to the park. Moreover, the park exhibits poor cleanliness, as seen in the preceding

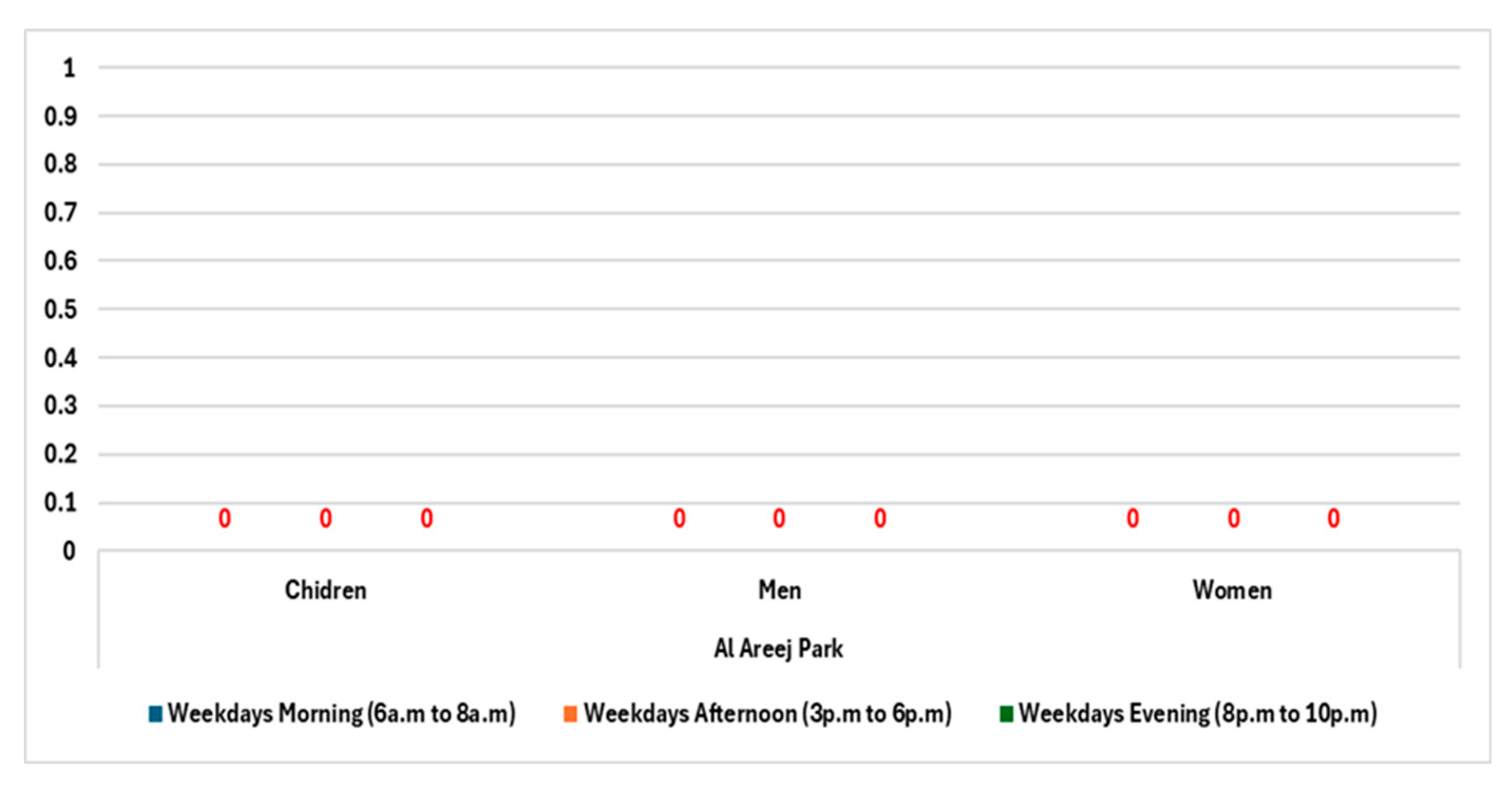

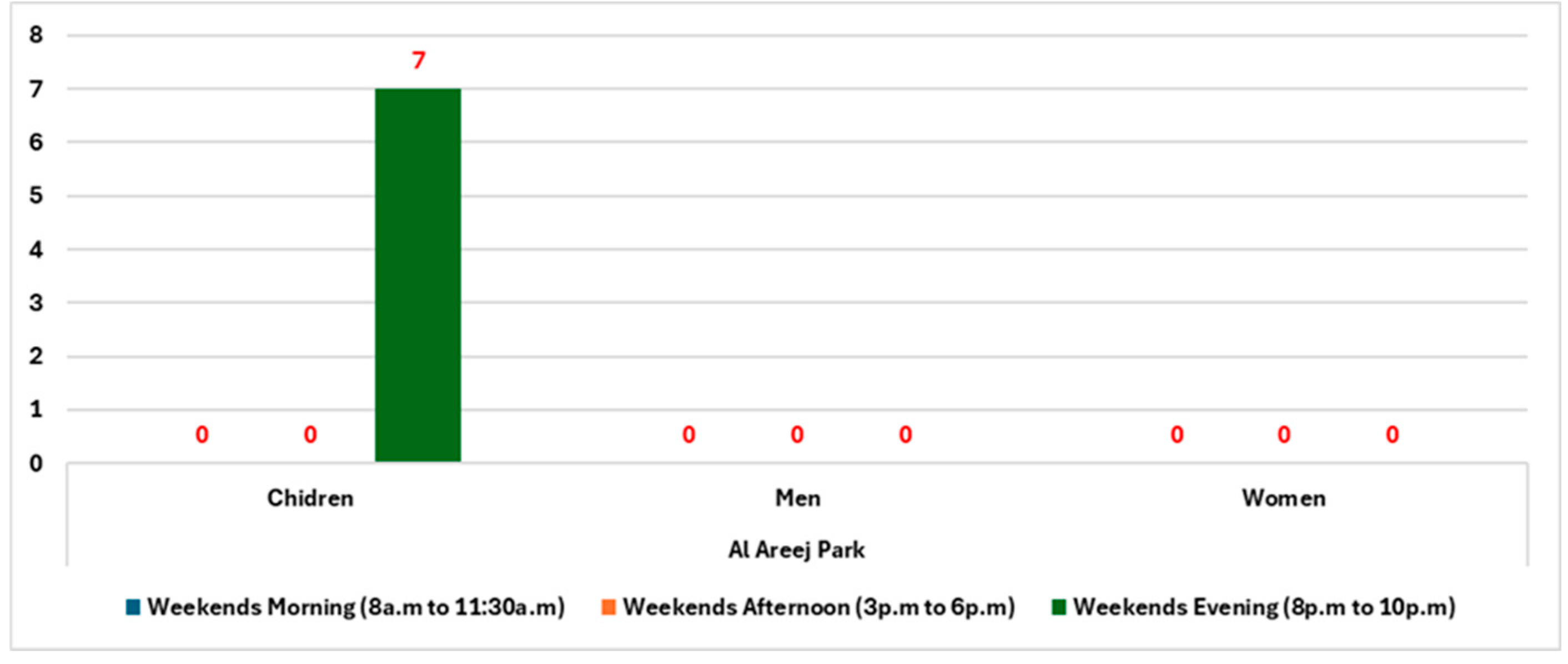

Figure 4, which presents a danger of epidemic and disease transmission. This is regarded as one of the factors that may affect psychological accessibility and consequently it restricts the number of visitors to the recreational park. Based on the preceding analysis, the observational mapping indicates that there were no visitors on weekdays or weekends, except for 7 youngsters who have visited the park to play football on the football field (See

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Consequently, the visitor numbers for Areej Park underscore the need for regular maintenance for the recreational park, including lighting, the football field, seating places, the play area, and the jogging route. The observational assessment of Areej Park highlighted the impact of regular maintenance on the psychological park accessibility.

- 2.

Nada Park:

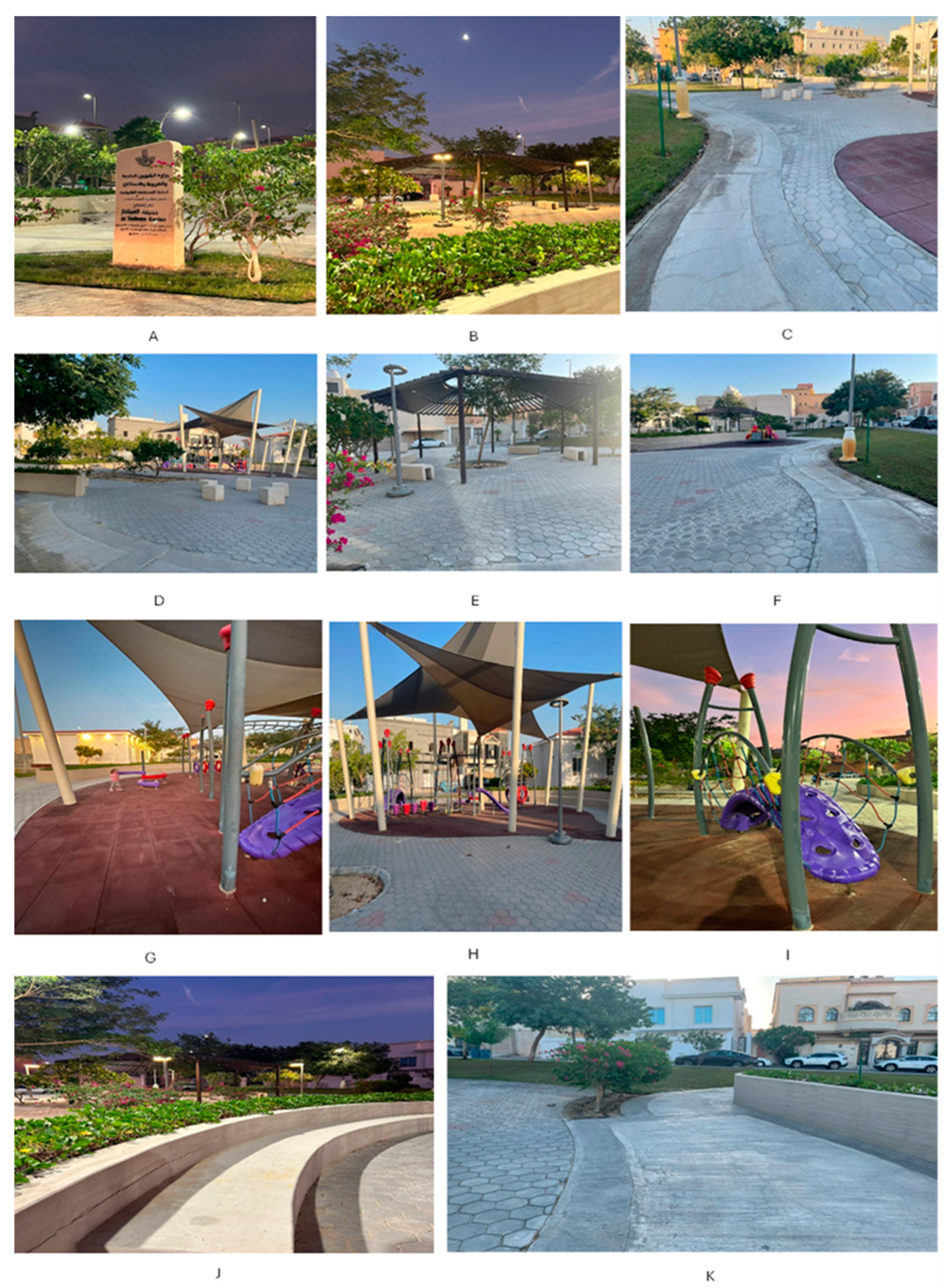

Nada Park is located in Khobar, particularly in Al Hizam Al Thahabi neighborhood, and is mainly surrounded by single-family housing. The park's estimated size is around 4,085 m². Below

Figure 7 shows physical characteristics of the indicated park. The park offers visible permeability throughout the complete park area, thus not obscuring the visual sight for the visitors. In addition, the park offers transparency with extremely high degrees of visibility by clearly presenting the choices and activities of the leisure facilities for the local people in the residential neighborhood. The park provides parking spaces which enhance the physical accessibility of the park. Moreover, the park stands out for having a walking and jogging path as well as green areas, which accentuates the surroundings and increases their appeal to visitors.

Although the several advantages of the Nada Park, including a football field, shaded seating areas, jogging route, and play area, observational behavioral mapping revealed a deficiency of visitors on both weekdays and weekends. As seen in the following

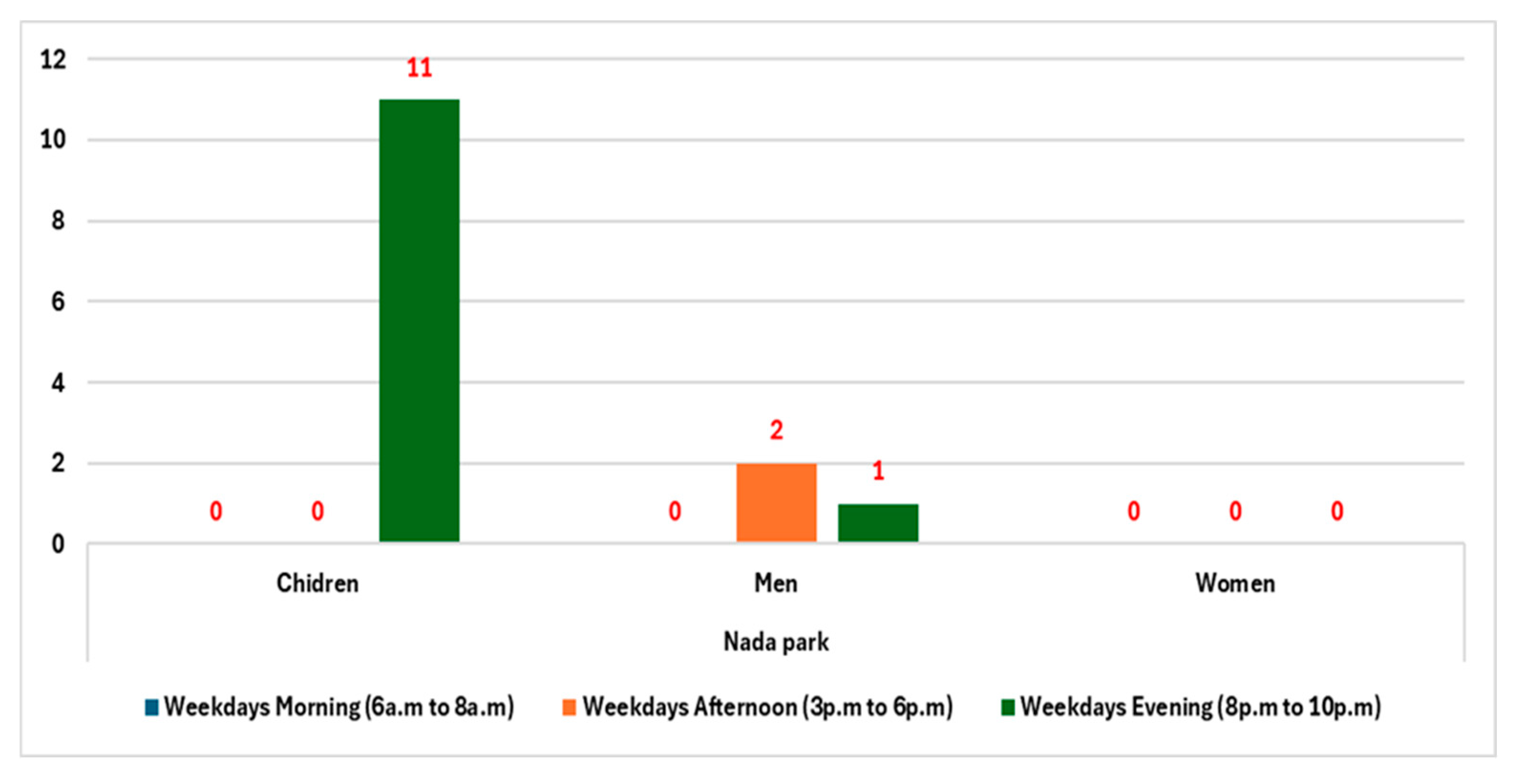

Figure 8. It was observed that 11 youngsters attended the park to play football on the field.

Similarly, the observational mapping, it has revealed that there is a very limited number of visitors in the recreational park on the weekends. As presented in the below

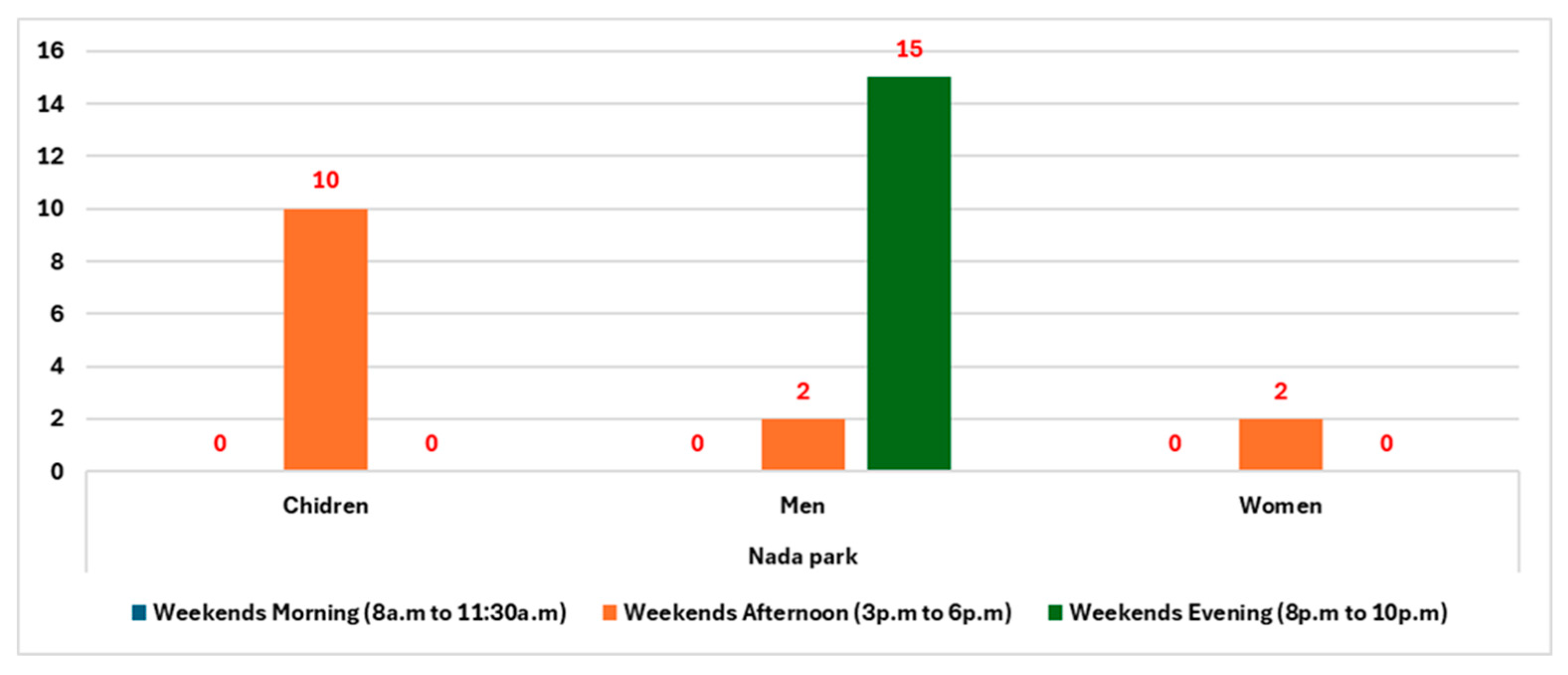

Figure 9, 10 children in the afternoon and 15 men in the evening time. According to the observational mapping, the most frequent activity was playing football by children and even sometimes by men.

Below

Table 1 represents the observational mapping statistics of the two recreational parks in Khobar.

In summary the case studies of Khobar, the comparison between the two case studies in Khobar City has revealed the pivotal role of the location (Spatial Distribution) of the parks in the residential neighborhoods as an important factor that may influence the number of visitors.

As discussed in the previous paragraphs, Nada Park suffers from the limited visitors or sometimes its absence despite the availability of most of the physical attributes that provide comfort to the users, for example, a path for walking or jogging, various and comprehensive play areas, areas designated for rest and relaxation, green areas that add beauty to the park and others. The interpretation behind these differences in the number of visitors is that residents of residential villas usually have yards in their private homes for practicing sports and other things, and even for children, they may have a playroom in the house or an outdoor yard. Therefore, the statistics of visitors to Al Nada Park indicated a limited number of visitors. On the other hand, the residents who live in the apartments may not have space for jogging, comfortable relaxation area or playground area for children. Consequently, the result indicated the impact of the spatial distribution of the parks as one of the factors that may undermine psychological access to recreational parks.

Moreover, the comparison between the case studies emphasized the importance of the periodic maintenance of the park as one of the factors that may influence access to recreational facilities. As represented previously, the park is facing issues with uneven jogging tracks and lighting, leading to falls and accidents. The pitch black at night can negatively impact visitors' sense of security. Therefore, the importance of proper lighting, particularly in the evening, is crucial as it impacts directly on the park's overall safety and security. Hence it will directly affect the perception of the neighborhood residents and influence directly the psychological accessibility to the recreational park.

Based on the preceding discussions, observational mapping and qualitative analysis suggests two factors that may undermine the access to the recreational parks, they are as follows: (1) location (Spatial distribution) of the recreational parks and (2) the periodic maintenance of the recreational parks.

Case Study 2: Dharan City

The observational mapping in Dhahran City was conducted in two various recreational parks in two different residential neighborhoods. The selected recreational parks are as follows, (1) Sadeem Park and (2) Ajyal Park-01.

- 1.

Sadeem Park:

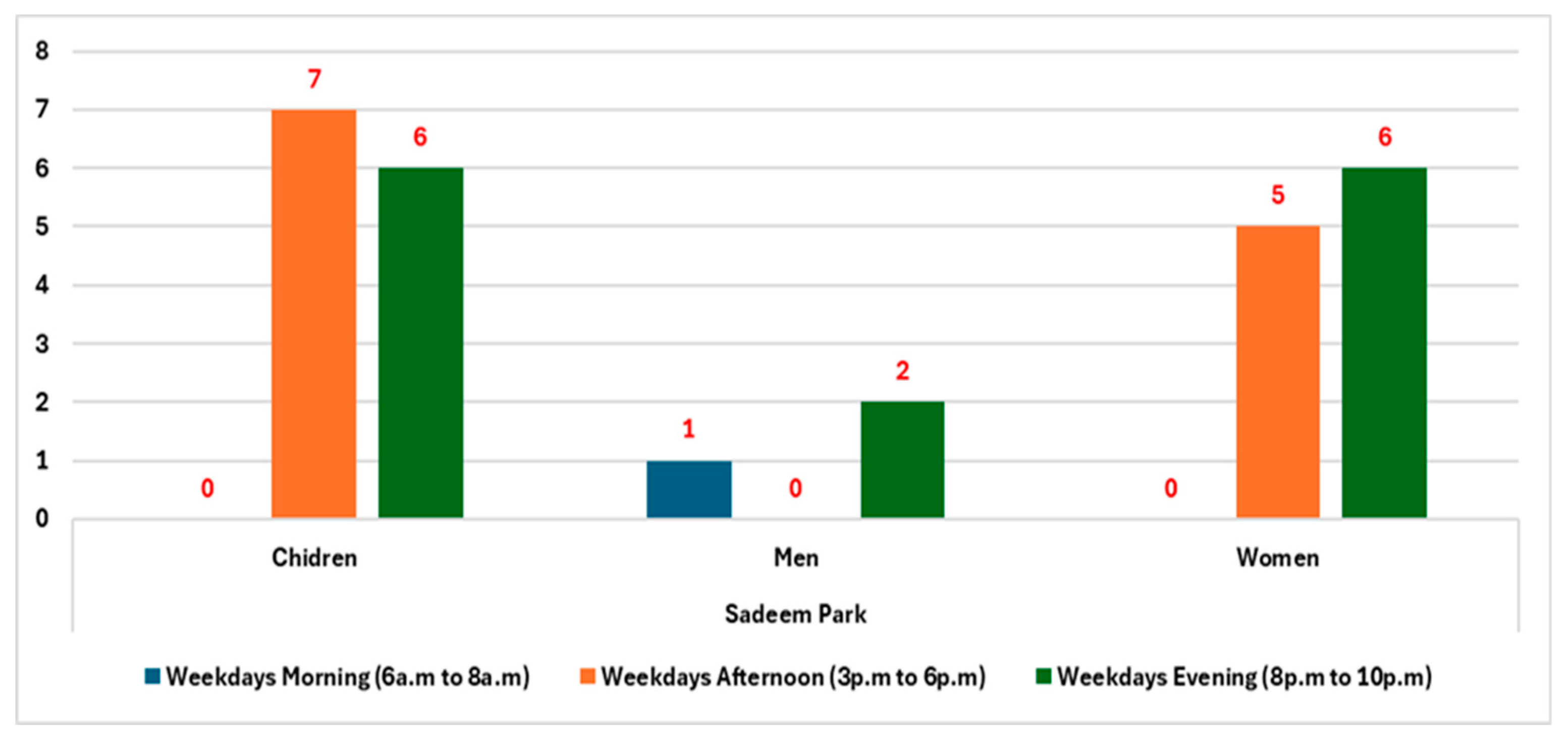

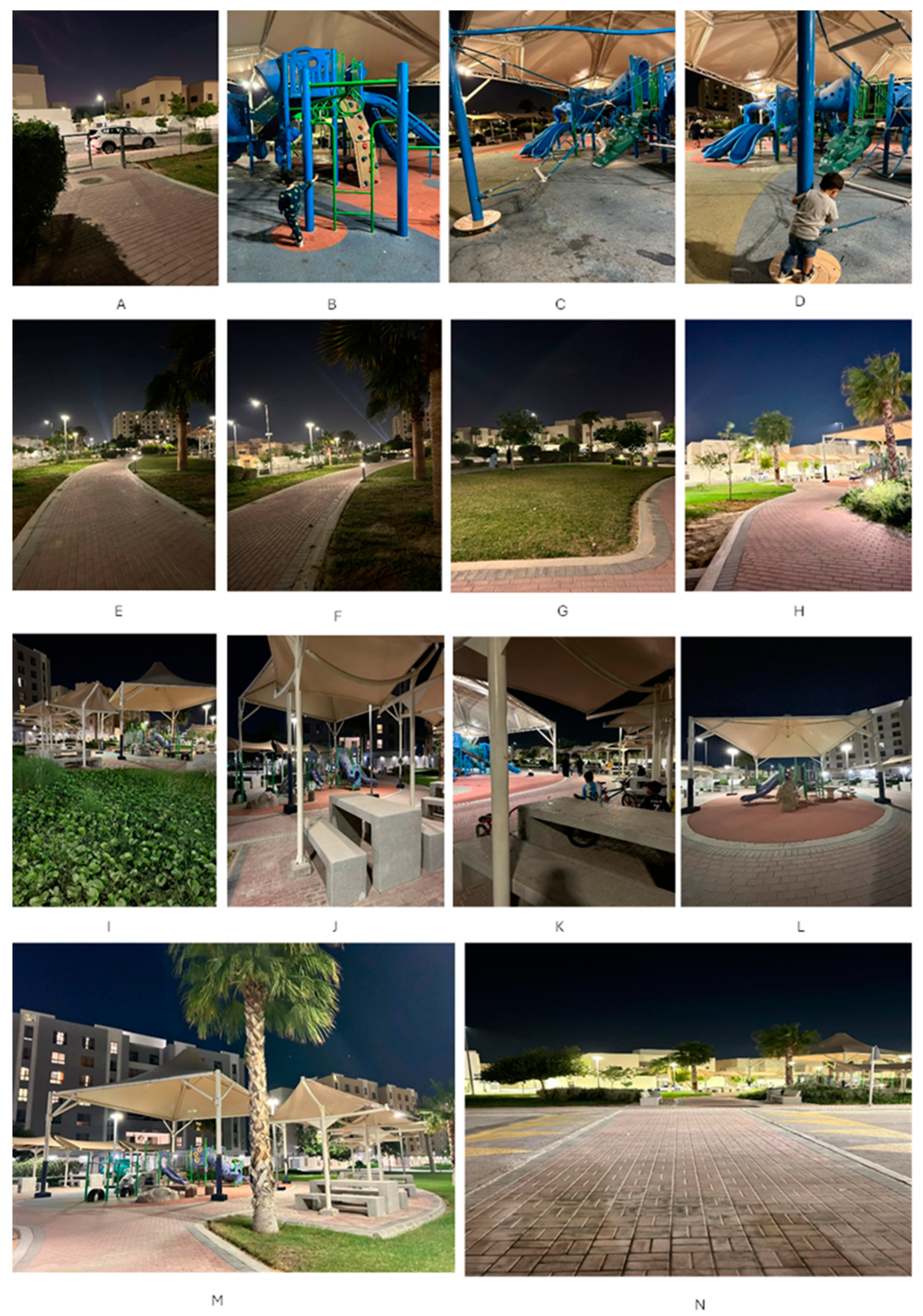

Sadeem Park is situated in the Qusour area of Dhahran. The park's estimated size is 3,658.29 m². The park is situated in a mostly residential area characterized by single family housing. Visual inspection of the park has shown that it offers several essential physical attributes (See

Figure 10). The park offers a walking and jogging track surrounded by green spaces, shaded seating areas for relaxation, picnics, and social gatherings. The park also provides parking spaces for easy access. In addition, the park provides a play area, which consists of several recreational equipment and covers various age groups in order to attract the children along with their families.

The case of Sadeem park is like Nada Park as both parks are surrounded with mainly residential villas and the two parks provide essential physical attributes for the visitors such as a play area, shaded sitting area for relaxation and social gatherings, jogging track and green space which give beauty to the place. However, both parks suffer from a lack of visitors. The following

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate the statistics of the visitors on the weekdays and weekends respectively. Observational mapping has revealed that there is no big difference between the number of visitors on the weekdays and weekends. As shown in

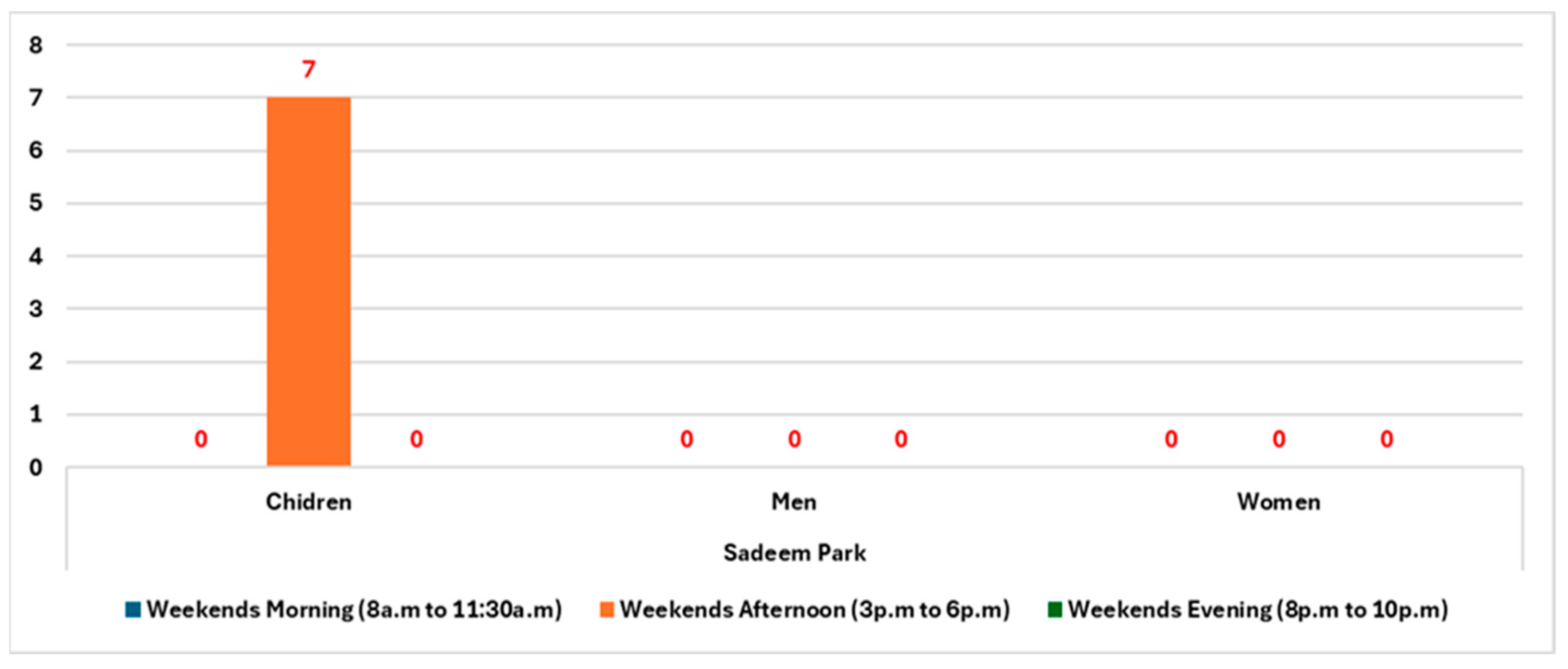

Figure 11, the number of visitors in the weekdays is 1 individual man only in the morning. Similarly, the main purpose of visiting the park in the morning is to practice jogging. While the observational reveals that 7 children and 5 women who visited the recreational facility in the afternoon time. In the evening, based on the observational mapping, the number of visitors is 8, 2 and 6 of children, men and women respectively who visit the park.

On the other hand, as shown in the below

Figure 12, observational mapping reveals that the number of visitors at weekends was only 7 children. Based on the comparison between the statistics of the Sadeem park visitors on weekdays and weekends, it is well noted that the number of visitors in the weekdays is more than during the weekends which is considered contrary to the context of Saudi society. Hence, the reason behind that is the weather was hot and sunny during the conduction of the observational mapping in Sadeem Park at the weekends.

Based on the observational mapping, Sadeem park is primarily visited by men and women during afternoon and evening hours for relaxation, running, walking, family gatherings, and child supervision during their playing. On the other hand, children usually enjoy playing in the playground, swinging and riding bicycles.

Based on the preceding paragraphs, the visiting statistics of Sadeem Park have suggested that the climatic environment of the park is considered to be one of the main factors that may influence the access to recreational parks in the residential neighborhoods.

- 2.

Ajyal Park-1

Ajyal Park-01 is located in Dhahran particularly in Ajyal residential neighborhoods with an estimated area of 7,944 m2. The park is surrounded by single family housing and apartments buildings. The location of the park is characterized by it directly in front of the apartment buildings which may enhance the physical accessibility to the recreational park hence it will affect positively the psychological accessibility and facilitate frequent utilization of the recreational facilities due to proximity to the park. The park offers a walking and jogging track surrounded by green spaces, shaded seating areas for relaxation, picnics, and social gatherings. The park also provides parking spaces for easy access. In addition, Ajyal park-01 offers a range of amenities for its users, including several pieces of recreational equipment which covers different age groups. It also provides a fence for safety and security specifically for children. On the other hand, the park's fence does not obstacle the visual which provides visual permeability, showcasing the recreational parks and activities for neighborhood residents which may encourage neighborhood residents to use the recreational park. Below Figure.13, shows the activities of the visitors and essential amenities of the park.

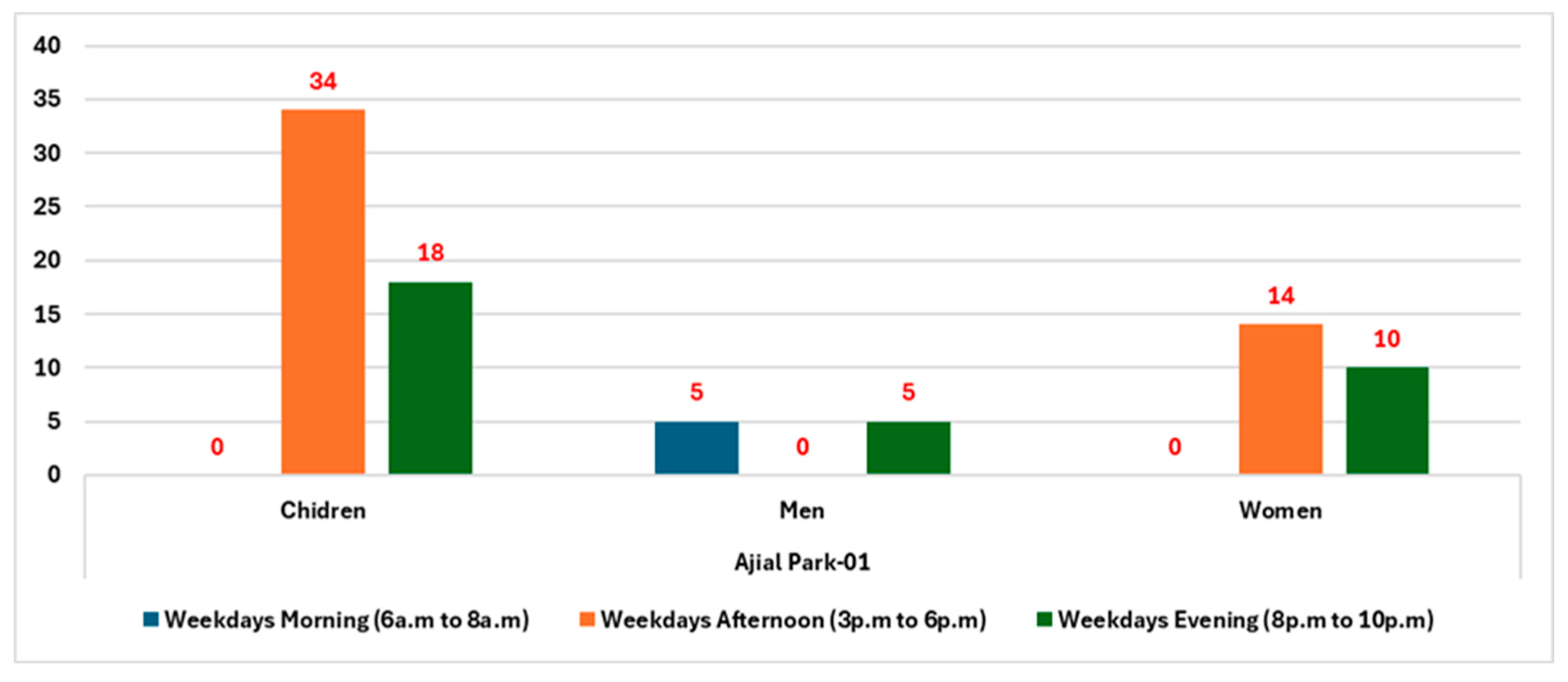

Observational mapping has shown no substantial changes in visitor numbers between weekdays and weekends. The findings indicated restricted use of recreational parks in the early hours. As seen in the below

Figure 14, the number of visitors on weekdays, consists only of five men in the early morning. The primary objective of visiting the recreational park in the morning is to practice jogging exercises. The observational mapping indicated that 34 children and 14 women have visited the recreational park in the afternoon. While, in the evening, the observed number of visitors to the park comprises 33 individuals, including 18 children, 5 males, and 10 women.

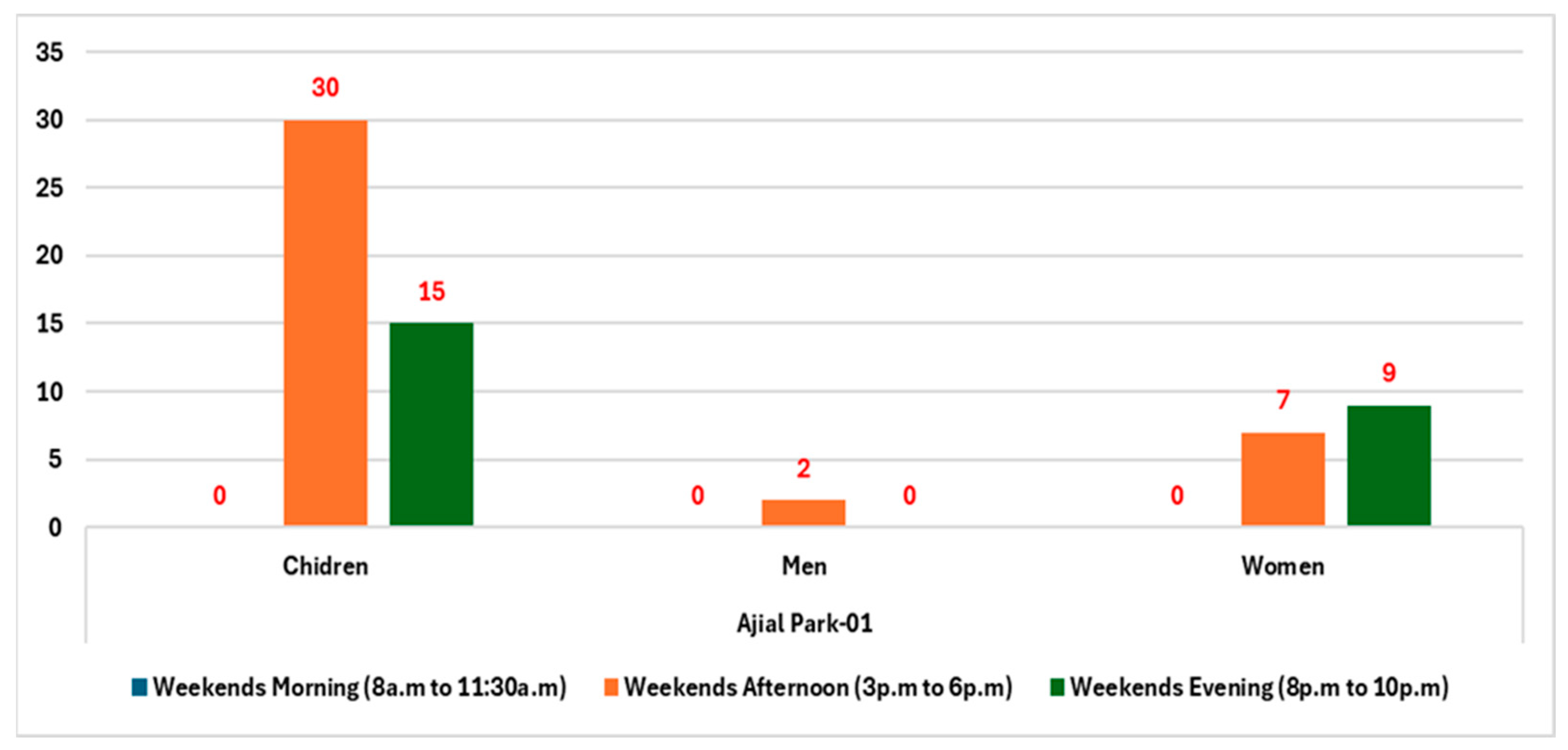

Conversely, observational mapping indicates that the visitation count on weekends closely resembles that of weekdays. As seen in the below

Figure 15, it was noted that there were 30 children, 2 males, and 7 women in the afternoon. In the evening, it was noted that there were 15 children and 9 women. While no visitors were observed in the morning. Similarly, the reason behind the lack of visitors to the parks in the morning, specifically at the weekend, is that people usually take a rest and sleep.

The observational mapping reveals that the primary motivation for visiting the park in the morning is to walk or jog before going to work. During the afternoon and evening, the majority of people use is for leisure, jogging, family reunions, and kid supervision. Children like engaging in activities inside the playground, which have slides, swings, and more apparatuses. Additionally, it was noted that several visitors of the children are using bicycles. The park has covered shaded seating spaces that enable families to directly monitor their children while they play. The observational mapping has revealed that several of the families that live in apartments opposite the park their visiting and practicing various activities in the park. Thus, this indicates that the proximity of the parks to the residential buildings is considered an advantage that may improve the access to the recreational facilities in the residential neighborhoods.

Below

Table 2 represents the observational mapping statistics of the two recreational parks in Dharan.

To sum up, the comparison of the two case studies in Dhahran emphasized that the playground area in the park directly impacts the number of children’s visitors and subsequently influences the visiting of families. Moreover, the observational mapping of the frequent activities by children, men and women in the recreational parks indicated the highly importance of the physical attributes of the recreational parks such as, shaded seating spaces, jogging routes and parking spaces. in addition to the toilets for both male and female which facilitate and encourage visitors to spend more time in the park. The comparison between Ajyal park-01 and Sadeem park indicated the impact of the spatial distribution of the parks as one of the factors that may undermine the access to the recreational parks.

Case Study 3: Dammam City

The observational mapping in Dammam City was conducted in two different recreational parks in two various residential neighborhoods. The selected recreational parks are as follows, (1) Raka Square Park and (2) Ash Shulah Park.

- 1.

Raka Square Park

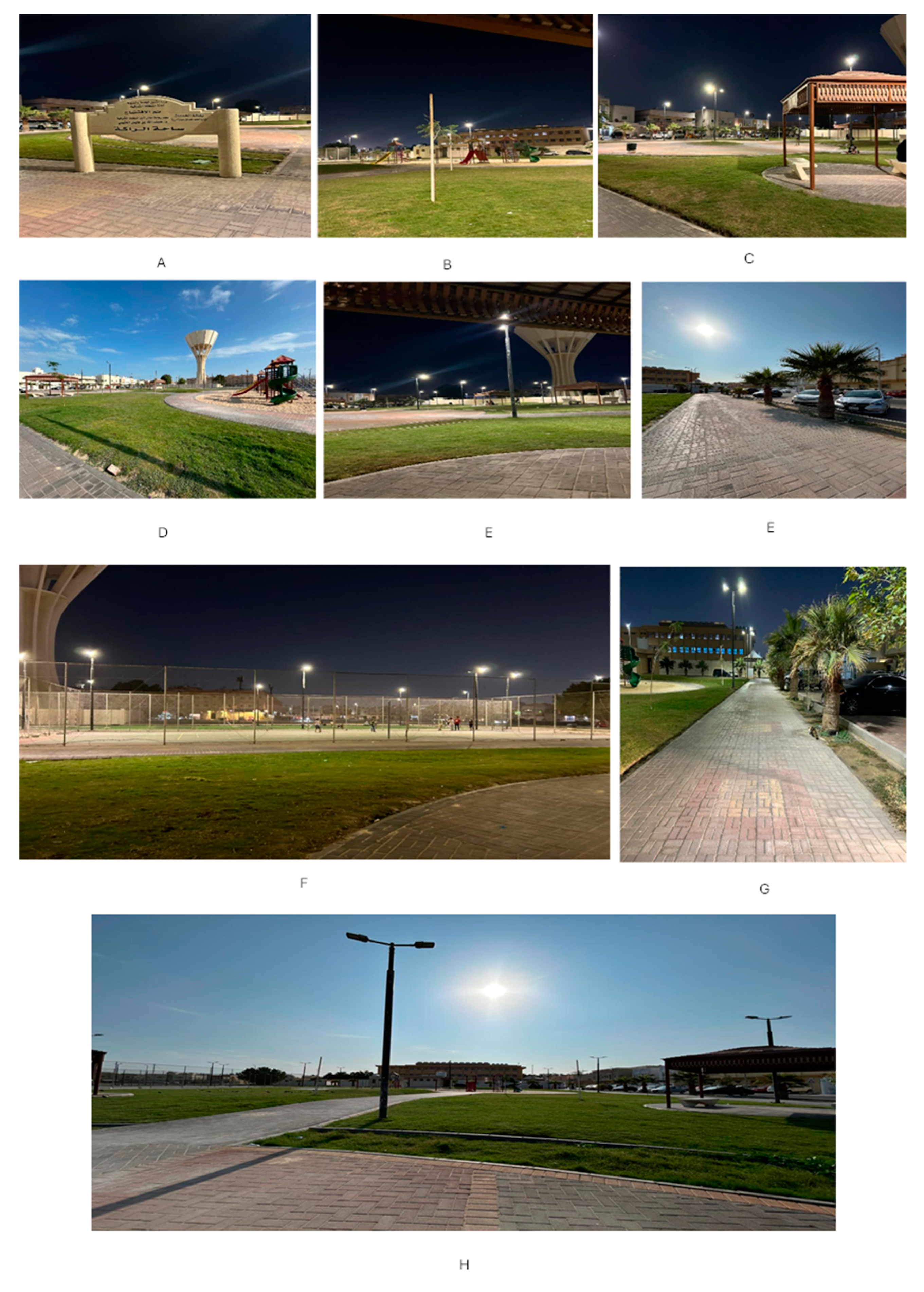

Raka Square Park is situated in Dammam, specifically in the North Rakah Neighborhood, with an approximate size of 8,151 m². The park is encircled by single family housing and apartment building.

Observational mapping indicates that the park provides an expansive green space, but the playground area is inadequate, lacking the capacity to accommodate diverse age groups. Hence, the play area is devoid of various recreational apparatus, including seesaws, swings, slides, jungle gyms, sandboxes, spring riders, trapeze rings, playhouses, mazes, and others. On the other hand, there is a large football field which may increase the influx of young people and children in the park to play football with relatives and friends. Additionally, the park has a walking and jogging route encircled by verdant areas that enhances its aesthetic appeal and may motivate local people to engage in running activities inside the park. Additionally, the park offers shade seating places for relaxation, picnics, and social events among family and friends. The park offers parking facilities that may enhance accessibility to the area. Figure. 16 illustrates the diverse activities of users and the physical attributes of the recreational park in Dammam City.

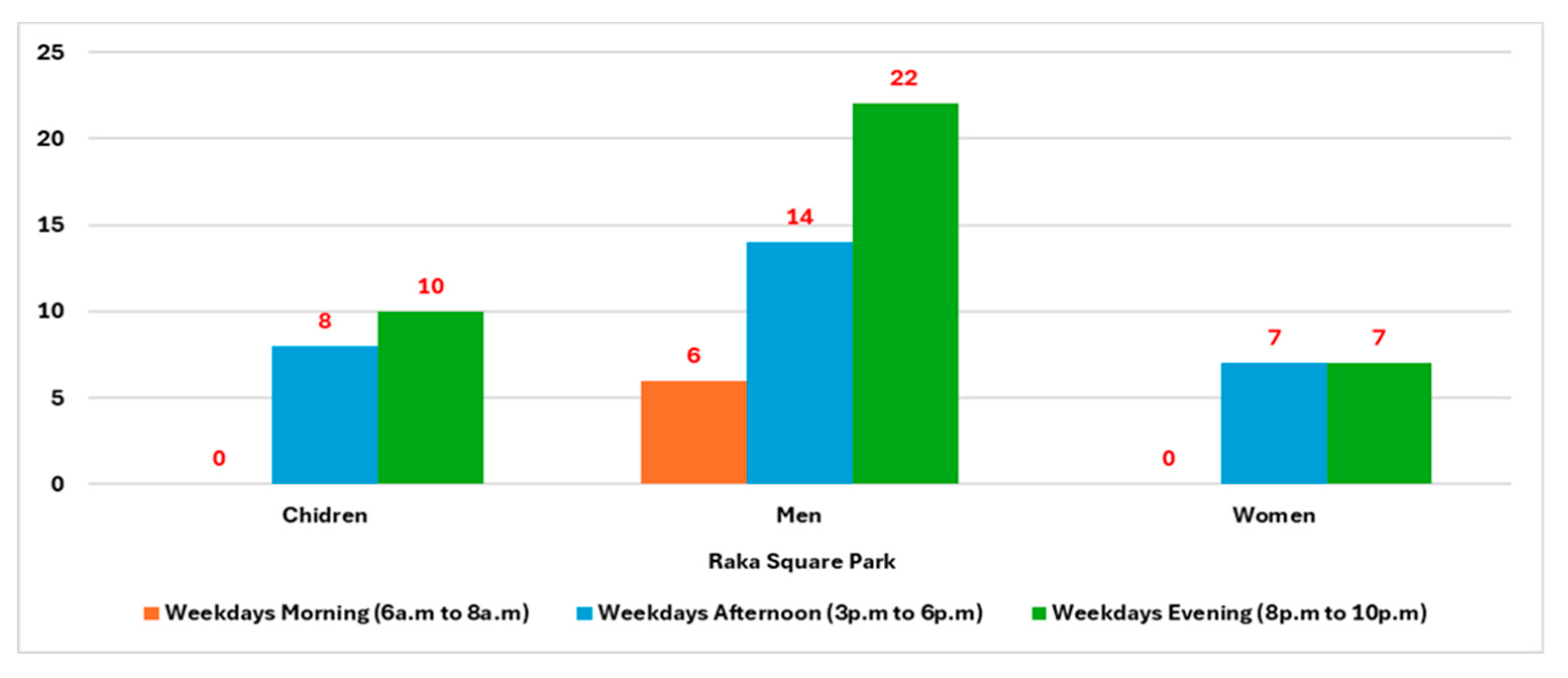

Observational mapping has shown that there is no significant disparity in visitor numbers between weekdays and weekends as seen in the below

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 respectively. Firstly, on weekdays, the number of visitors is limited to 6 males in the early morning. The primary objective of visiting the recreational park in the morning is to engage in jogging exercises. On the other hand, the observational mapping indicated that 8 children, 14 men, and 7 women attended the recreational park in the afternoon. While, in the evening, the park received 10 children, 22 men, and 7 women as users.

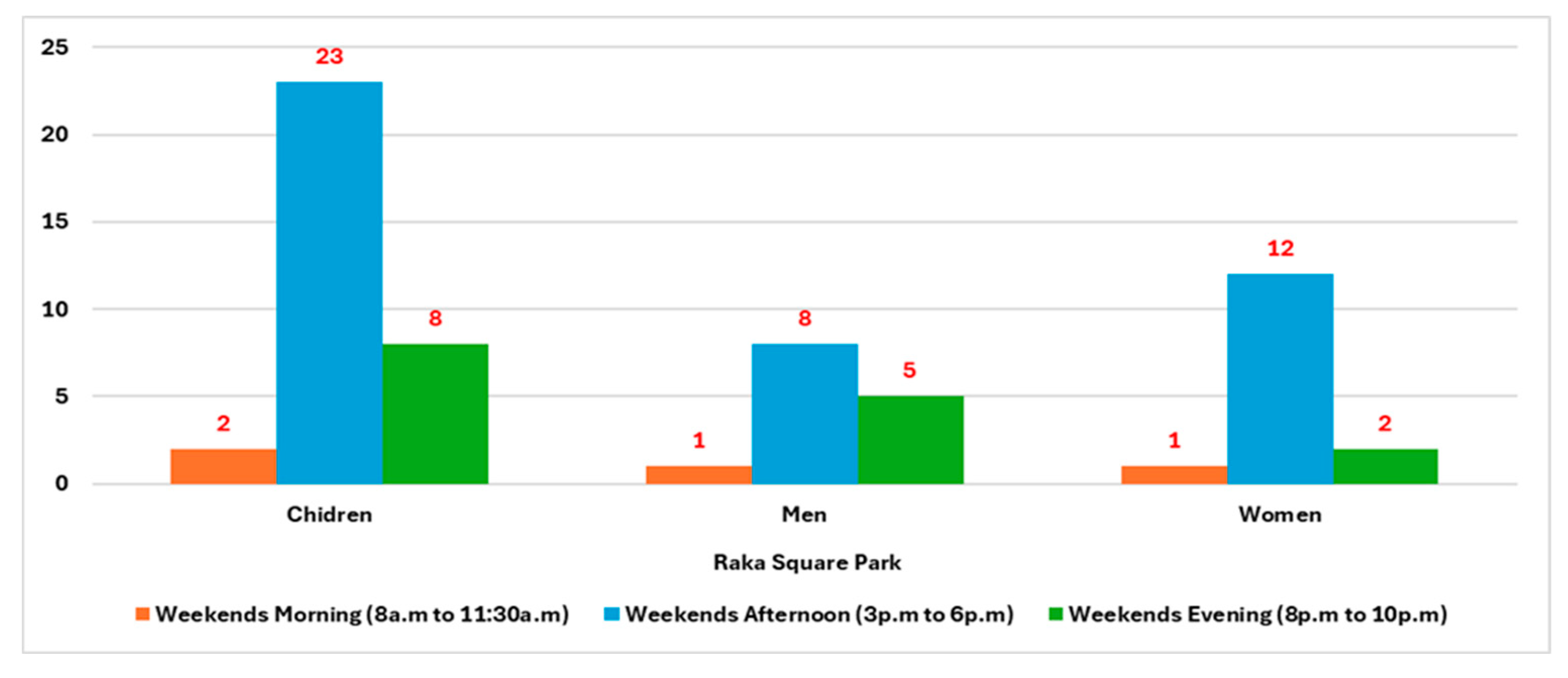

Likewise, as seen in

Figure 18, the number of visitors in the morning was significantly restricted. According to the observations, there were 2 children, 1 man, and 1 woman. On the other hand, it was noted that there were 22 children, 8 males, and 12 women in the afternoon. While, in the evening, it was observed that there were 8 children, 5 men, and 2 women. The visitation figures revealed that the park has insufficient attendance on both weekdays and weekends, necessitating an investigation into the primary factors that deter local people from using the recreational park.

Observational mapping indicates that men and women mostly frequent the park in the afternoon and evening for different purposes, including relaxing, strolling, informal meetings, child supervision, and other activities. Moreover, based on the observational mapping, it has been noticed that several men have used the area for playing football in the football field. The observational mapping indicates that the predominant activities for children at Raka Square Park include using the playground and engaging in football. The quantity of children is much lower in comparison to other recreational parks, such as Ajyal-01 park. The restricted number of children, which may subsequently impact family visits, is attributable to the inadequate recreational equipment in the play zone (See

Figure 15). The play zone is very restricted and fails to accommodate various age groups. Thus, it underscores the significance of the playground area as a crucial element in attracting children and their families. The play area in the recreational parks should be varied and cater to various age groups to engage this demographic (children and their families) inside the residential areas. Moreover, Raka Square Park is deficient in shaded seating areas for families and children to unwind or engage in social events, since the majority resort to using mats and other objects. Therefore, the absence of seating locations in the recreational parks may restrict both formal and informal social interactions among individuals.

- 2.

Ash Shulah Park

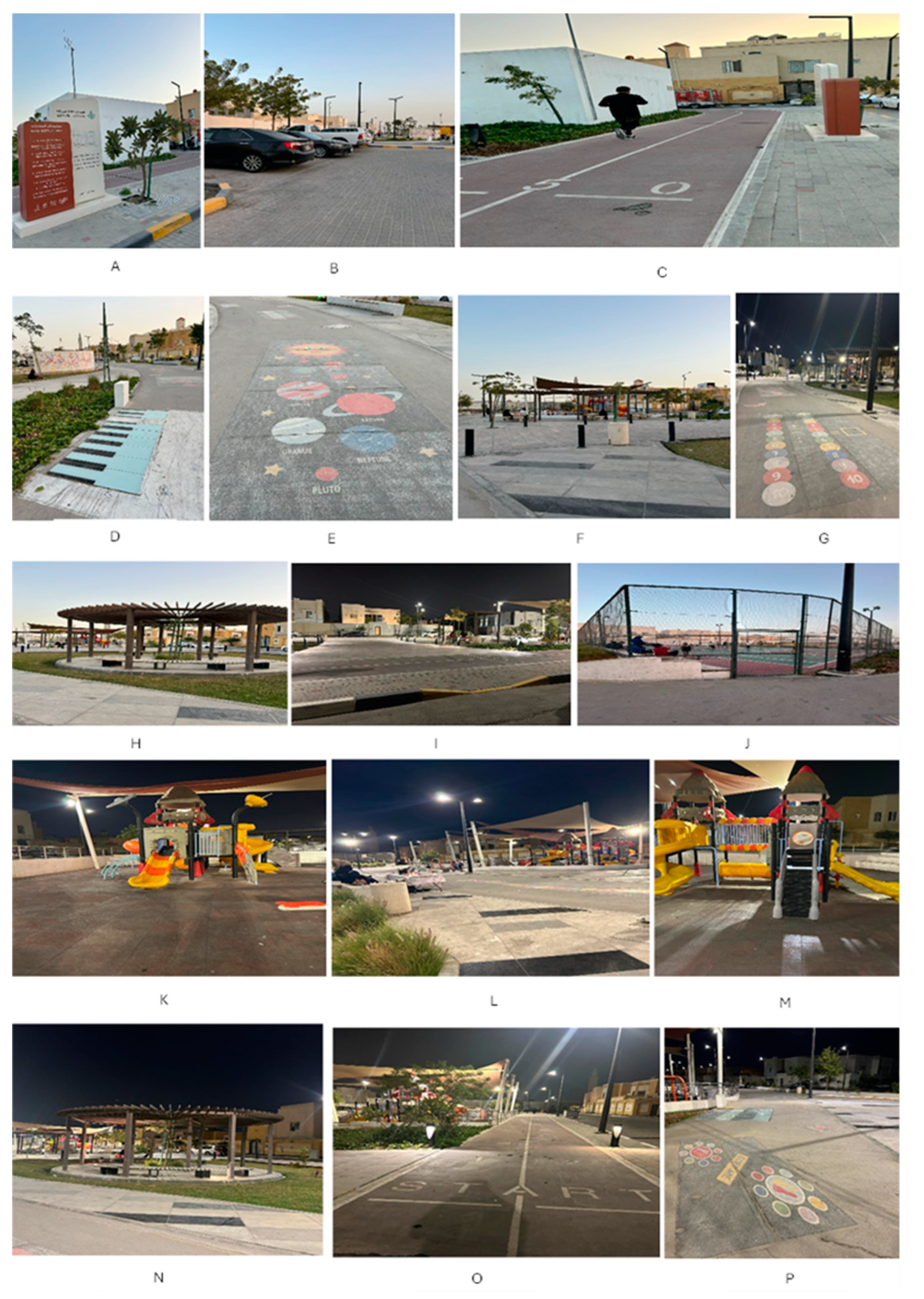

Ash Shulah Park is located in Dammam particularly in Ash Shulah Neighborhood with an estimated area of 1821m2 and surrounded by single-family housing and apartment building.

The park offers visible permeability throughout the complete park area, thus not obscuring the visual sight for the visitors. In addition, the park offers transparency with extremely high degrees of visibility by clearly presenting the choices and activities of the leisure facilities for the local people in the residential neighborhood. Moreover, the park provides parking spaces which enhance the physical accessibility of the park. Furthermore, the park is provided by specific entrance designated for handicapped people which provides social justice for all society members. In addition, it improves the physical accessibility to the recreational parks, which may influence positively psychological accessibility and increase the frequent use of the park. What distinguishes the park is that the existence of a wide path for walking and jogging track, along with vast green spaces, which adds beauty to the place and makes it attraction for those who practice these types of sports. Moreover, the availability of playground areas for children covering different age groups, which may increase the possibility of visiting the recreational facility with children with families. Furthermore, the park provides food & drinks Kiosks for the visitors particularly in the cold weather. The below

Figure 19 illustrates the activities of the people and shows the physical characteristics of Ash Shulah Park.

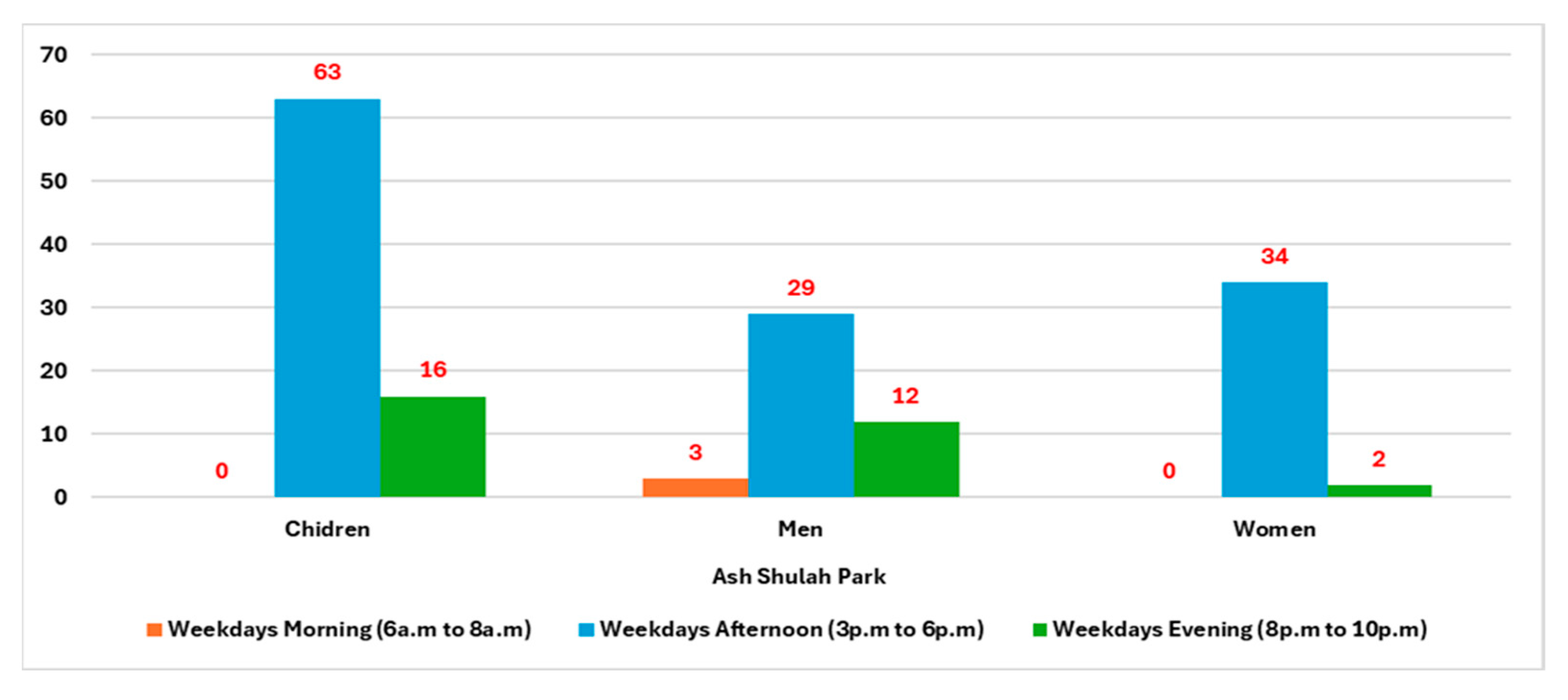

The observational mapping revealed no significant difference between the number of visitors to the park during weekdays and weekends. As illustrated in the following

Figure 20, during weekdays, morning visits to the park are limited to men only, which is quite similar to the preceding discussed case studies. Hence, it was observed 21 men who were visited the park in the morning during the weekdays. As the previously discussed case studies, the main purpose of their visit in the morning is to practice jogging before going to work. While in the afternoon and evening time, visitors, including children, men and women, flock to spend a pleasant time with their families. In the afternoon, it was observed that 63 children, 29 men and 34 women in the park. While, in the evening, the observational mapping reveals that 16, 12 and 2 of children, men and women respectively.

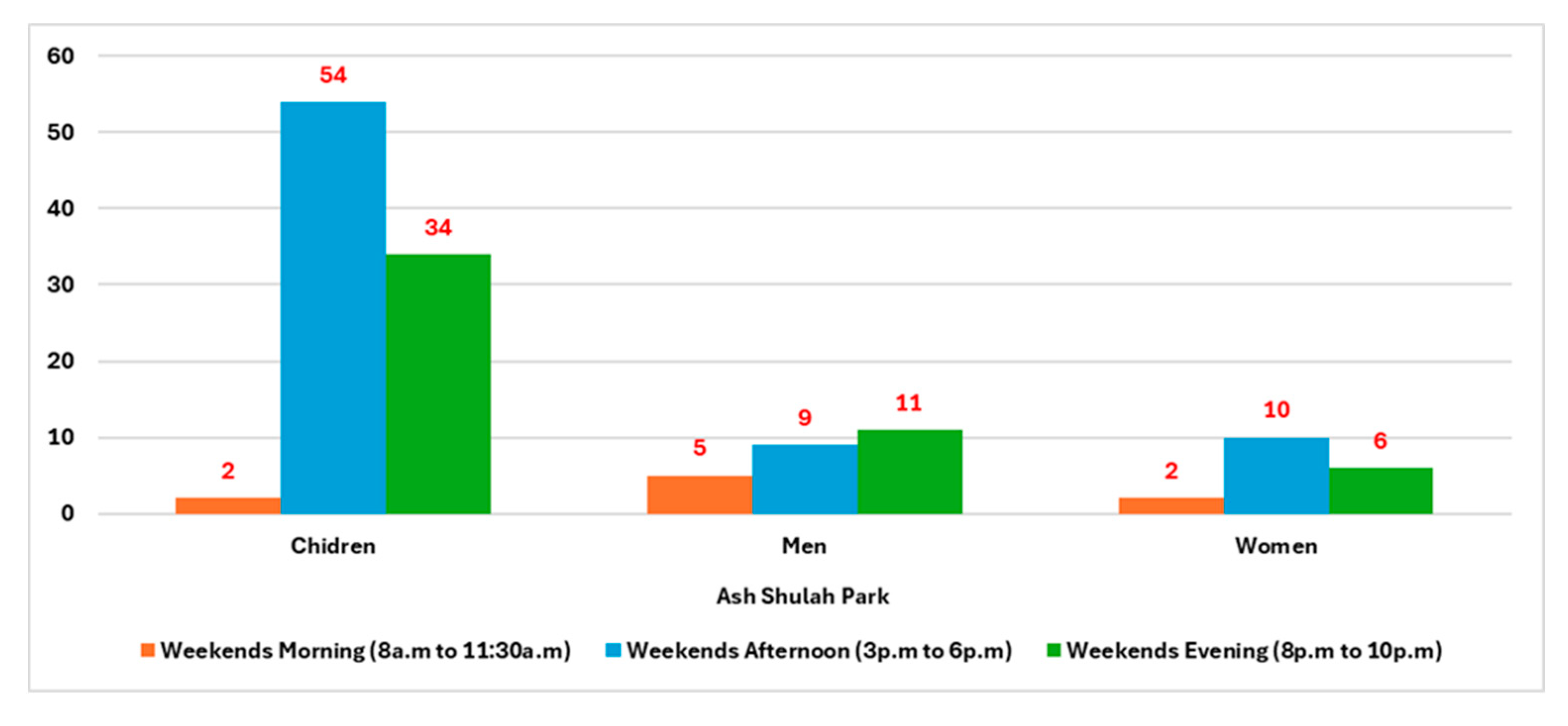

On the other hand, through observational mapping, it has been revealed that the number of visitors is quite similar to the number of visitors during the weekdays. As illustrated in the below

Figure 21, it was observed that 54 children, 9 men and 10 women in the afternoon. While, in the evening time, it was observed that 34, 11 and 6 of children, men and women respectively. While very limited visitors were observed in the morning. Similarly, the reason behind the lack of visitors to recreational facilities in the morning, specifically at the weekend, is that people usually take advantage of the weekends to sleep.

Based on the observational mapping, the main purpose of visiting the park in the morning during the weekdays is to engage in walking or jogging before heading to work. Consequently, the existence of the walking and jogging tracks in the parks is considered one of the attractive points to this category of people which motivates them to visit the recreational park. While the observational mapping reveals that in the afternoon and evening times, most men and women visit the park for various purposes such as, relaxation, running and walking practice, family or friends' gatherings to chat, child supervision and other various activities. While observational mapping has revealed that the most frequent activities by children in the park are playing in the playground area the slides and swings, riding bicycles and playing football. The statistics of the visitors (See Figure.24 and Figure.25) emphasized the importance of the various physical attributes of the parks such as comprehensive play area which covers different age groups, shaded seating areas, vast green space, football field, jogging track and others as they may attract different categories of visitors. Consequently, the perception of the status of the recreational parks will influence psychologically the access to the park in the residential neighborhood which may affect positively the frequent utilization of the recreational parks.

Below

Table 3 represents the observational mapping statistics of the two recreational parks in Dharan.

The analysis of visitation data for the two Recreational Parks in Dammam indicates that the playground area significantly influences the attraction of local youngsters and their families.

According to observational mapping, Ash Shulah Park has a playground equipped with diverse recreational apparatus suitable for various age groups (Refer to Figure 39). Conversely, Raka Square Park has a very restricted playground space, which has impacted the amount of kid visits.

Consequently, the analysis of visitation statistics from the case studies in Dammam indicates that the playground area in the recreational park directly influences the number of child visitors, which subsequently affects family attendance, as children in the Saudi context typically do not visit parks alone but accompanied by their families for supervision purposes.

The play area in parks is a fundamental element in attracting children and their families, alongside other physical features such as restrooms, shaded seating, jogging tracks, football fields, green spaces, and food and beverage kiosks.

Secondly, by using several literature review studies and observational mapping carried out by author, an online questionnaire was distributed to multiple colleagues in February 2025, and it received 256 complete responses with an average completion time of 3 minutes each. The survey utilized Question Pro for secure online submissions, and participants had the option to respond in Arabic or English. Prior to answering, participants were briefed about the survey's objectives.

The first twelve questions collected general demographic data. The first question asked about the participants’ locality, showing over 50% lived in Khobar, while nearly 24% were from Dammam. The second question about nationality revealed around 72% were Saudi citizens, important for understanding recreational preferences. The third question on gender indicated 67% were male, and about 33% female. Most participants (46%) were aged 18 to 24, while 29% were under 18. The fifth question addressed housing types, with 46% living in employer-provided units, and the sixth question revealed 75% were single. Regarding education, 35% had not completed their studies, and 73% were unemployed. For employed respondents, 55% worked in their neighborhoods, while 57% earned less than 5000 SAR monthly. Lastly, about 52% had relatives nearby. The below

Table 4 represents the details of the demographic data of the participants in the questionnaire survey.

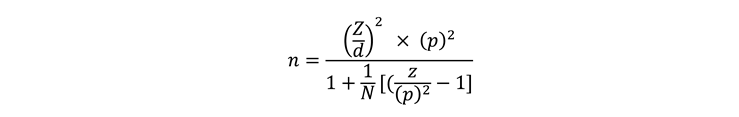

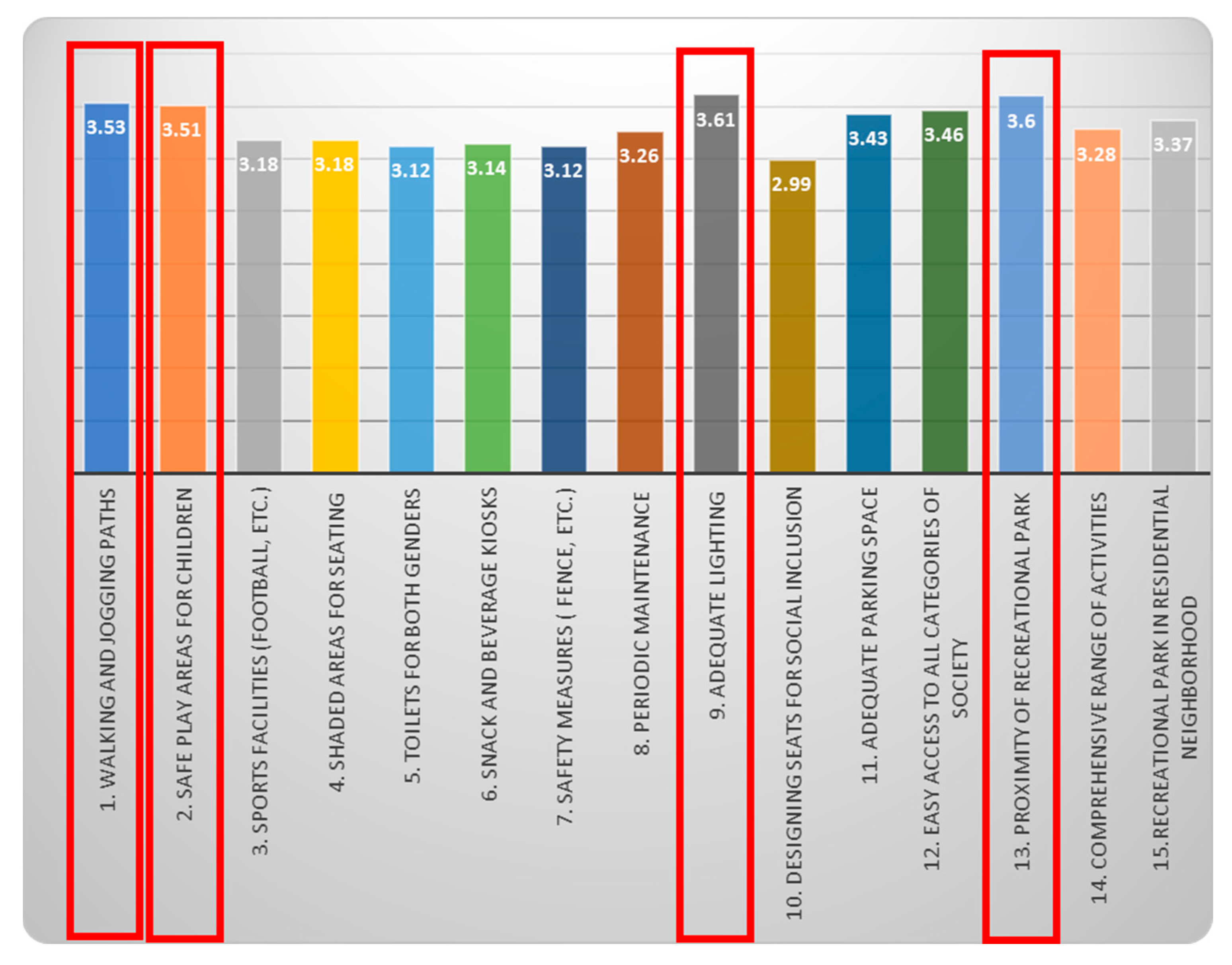

The physical factors were measured using a Likert scale, and the Anova single factor test showed a p value less than 0. 05, indicating a statistically significant result among the physical factors as in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Single factor Anova test on physical factors.

Table 5.

Single factor Anova test on physical factors.

It was important to summarize the highest and lowest ranked physical factors that might affect how often people use recreational parks.

Figure 22 shows the complete breakdown analysis of perception of the participants regarding the physical attributes of the recreational parks in DMA

Social sustainability characteristics were also measured on a Likert scale, with a significant result. Many participants (about 32%) had neutral opinions about their overall experience with neighborhood parks, suggesting they may be more open to persuasion.

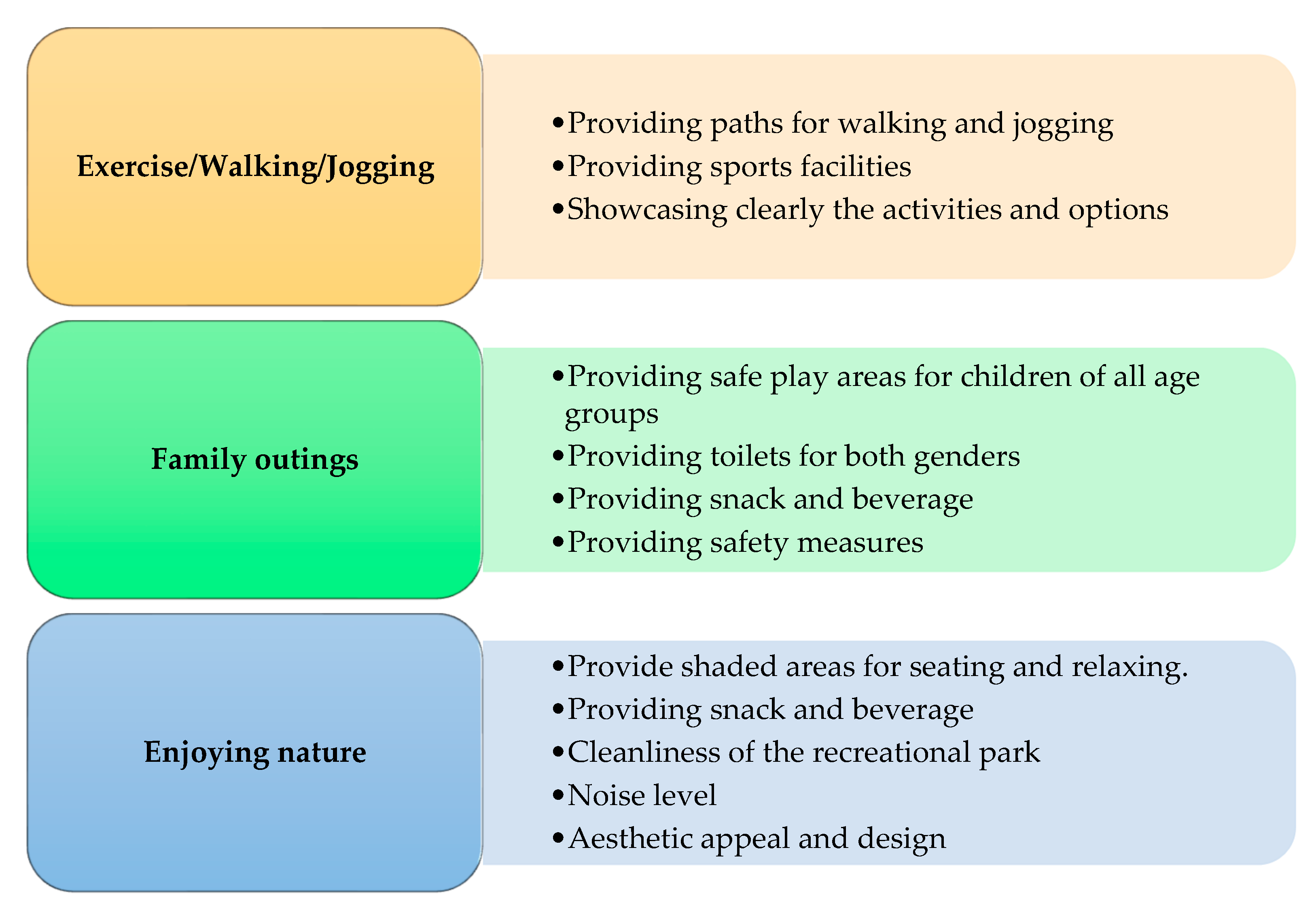

Furthermore, the analysis showed that most people visit parks for exercise, family outings, and relaxation in nature. It recommends focusing on amenities that support these activities. To boost park visits, it’s important to improve certain key aspects. Therefore, this study also identified key physical factors that need to be maintained or improved to encourage and improve park visits. Many respondents were dissatisfied with toilet facilities for different genders and the availability of snacks, as well as safety measures, suggesting that enhancements in these areas could attract more visitors. Additionally, over 68% of people were unhappy with the environmental design, indicating that improvements in noise levels, aesthetics, and cleanliness could enhance overall user experience. More respondents (44%) were dissatisfied with the parks than satisfied (24%), and the majority (53%) preferred meeting friends in other places rather than parks. Lastly, many people either never use these parks (20%) or visit only once or twice a year (30%).

The investigation in preceding paragraphs revealed that the majority of individuals use parks for exercise, family gatherings, and to appreciate nature for relaxation. Consequently, more emphasis should be directed towards facilities associated with the preceding qualities, since the individuals’ perceptions substantially influence their psychological accessibility to recreational parks. As an example, when people see parks as safe, welcoming, and inclusive, they feel more comfortable and are more likely to visit. On the other hand, adverse impressions, such as insecurity, congestion, or insufficient upkeep, reduce psychological accessibility and deter visitors. The following

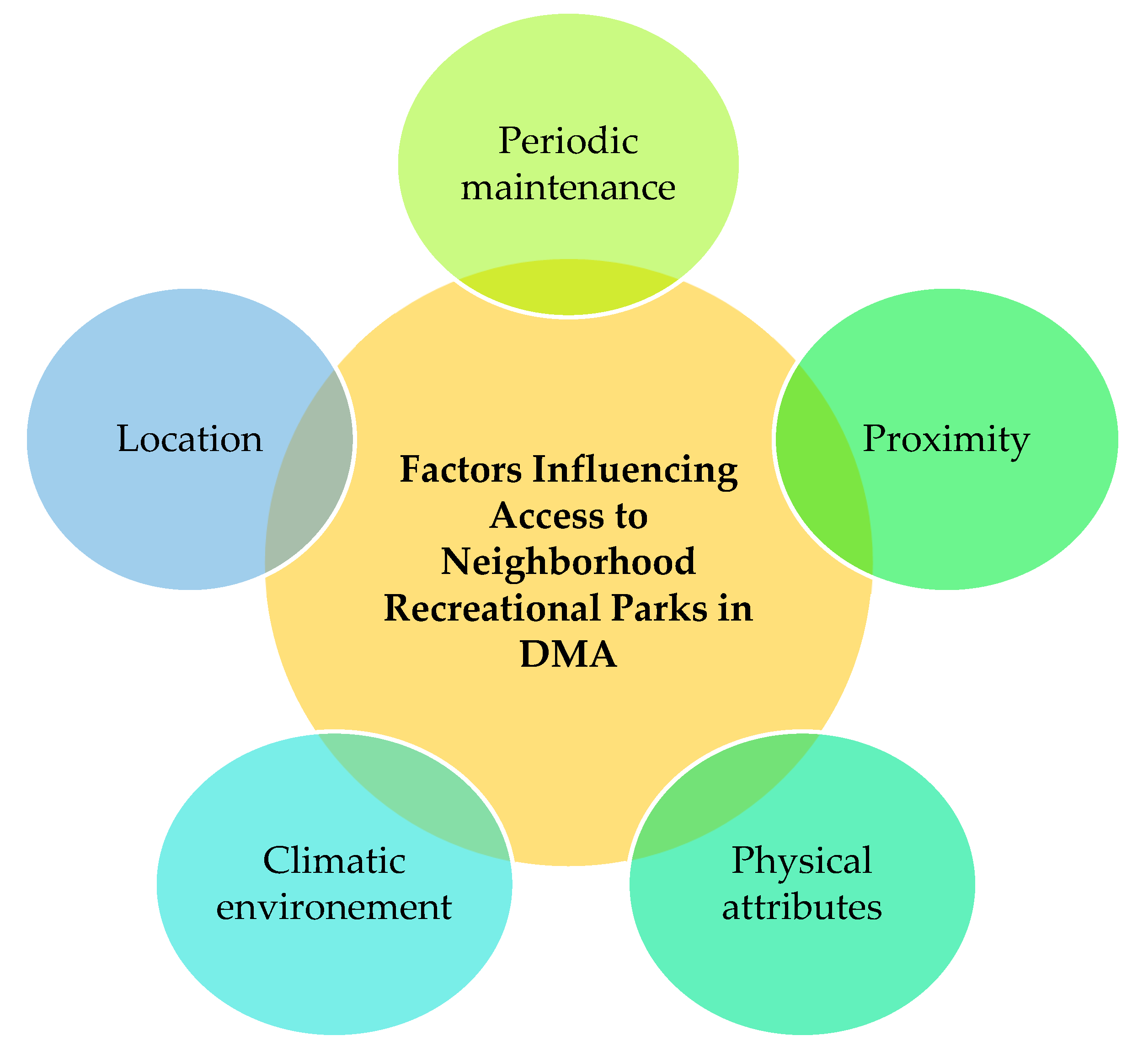

Figure 23 illustrates the primary characteristics discovered that may influence access to recreational parks and, therefore, their frequent use in DMA.