1. Introduction

Phosphorus is one of the most important macronutrients required for plant development, essential for energy transfer (ATP), signal transduction, and biosynthesis of nucleic acids and membranes (Khan et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2021). Despite its importance, phosphorus use in agriculture is highly inefficient, with a significant fraction of applied fertilizers becoming immobilized in soils or lost through runoff, contributing to eutrophication and ecological harm. Compounding the issue is the global dependence on non-renewable rock phosphate, which is unevenly distributed, expensive to mine, and projected to become increasingly scarce in the coming decades (Illakwahhi et al., 2024; Walsh et al., 2023). Ironically, agricultural soils and crop residues already contain large amounts of P, mainly in the form of phytate (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate), the principal storage form of organic phosphorus in seeds and plant tissues. However, phytate remains largely inaccessible to plants due to their natural deficiency in phytase enzymes, which are required to hydrolyze it into plant-available inorganic phosphate (Hollenback 2024; Raguet et al., 2024). Phytate accounts for up to 50–80% of the total organic phosphorus in soils and seeds, yet plants cannot directly utilize it due to the lack of phytase enzymes required to break it down (Liu et al., 2022). To address this paradox, researchers have turned to two promising strategies. The first involves the use of phytate-degrading and phosphate-solubilizing microbes to mobilize phosphorus from soil-bound sources. The second utilizes genetic engineering to create transgenic crops capable of producing phytase internally, thereby accessing their own phosphorus reserves (Pan and Cai 2023; Vashishth et al., 2023). This review aims to critically assess both strategies, individually and in combination, and explore how they can be integrated to create a closed-loop phosphorus cycle in agriculture. By evaluating recent advances, current challenges, and future directions, we propose a dual-strategy model that leverages microbial ecology and plant biotechnology to enhance phosphorus use efficiency, reduce fertilizer dependency, and contribute to sustainable agricultural systems.

2. Phytate in Soil vs Plant (Distribution and Accessibility)

Phytate (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate) serves as the major storage form of phosphorus in both plant tissues and soils (Kumar and Anand 2021; Sharma et al., 2022). In seeds, it is primarily concentrated in the aleurone layer and embryo, acting as a phosphorus reservoir during germination. However, most crop species lack the phytase enzyme required to break down phytate into usable inorganic phosphate (Pi), rendering this internal phosphorus pool largely inaccessible during early growth stages (Liu et al., 2022; Asif et al., 2022). As a result, even though phosphorus is present within the plant, it remains largely inaccessible to the plant itself during critical growth stages (Kumar et al., 2023). In soils, phytate accumulates from decaying plant residues, animal manure, and compost inputs. Once deposited, phytate tends to bind strongly with soil minerals particularly calcium, iron, and aluminum, forming stable complexes that are insoluble and resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis. This mineral-bound form of phytate significantly limits its availability to both microbes and plant roots (Liu et al., 2022).

Access to phytate depends on its location:

- ☐

External (Soil Phytate): Accessible through microbial intervention. Soil-dwelling microbes in the rhizosphere, especially phytate-degrading bacteria (PDB), can secrete extracellular phytase to hydrolyze phytate and release Pi, which can then be absorbed by plant roots (Shi et al., 2025).

- ☐

Internal (Seed Phytate): Inaccessible to external microbial enzymes due to cellular compartmentalization. Genetic engineering is required to enable plants to express phytase intracellularly, allowing direct utilization of their phosphorus stores (Balaban et al., 2016).

Importantly, phytate in the soil environment can be targeted by rhizosphere-associated microbes, particularly phytate-degrading bacteria that secrete extracellular phytase enzymes (Arif et al., 2017; Mohite et al., 2019). Thus, the phosphorus locked in phytate exists in two biologically distinct pools, extracellular (soil) and intracellular (seed), each requiring a targeted approach for mobilization. Understanding these distinctions is critical for designing comprehensive strategies that combine microbial and plant-based innovations to overcome phosphorus limitation in agriculture.

3. Microbial Strategies for Phytate Utilization

Microorganisms in the rhizosphere play a vital role in mobilizing phosphorus bound in organic and inorganic forms. Two key microbial groups involved in phytate transformation are phytate-degrading bacteria (PDB) and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) (

Table 1). While their mechanisms differ, both contribute to enhancing phosphorus bioavailability in soils (Rajapitamahuni et al., 2023).

3.1. Phytate-Degrading Bacteria

Phytate-degrading bacteria directly hydrolyze phytate through the secretion of extracellular phytase enzymes. These enzymes cleave the phosphate groups from the inositol ring structure of phytate, releasing inorganic phosphate (Pi) into the soil solution (Vashishth et al., 2023). Several bacterial and fungal genera, including Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Aspergillus, and Penicillium, have been identified as potent phytate degraders. Recent advances have focused on isolating thermostable and pH-resistant phytases that can function effectively across a range of soil environments. Some studies also report engineered microbial strains with enhanced phytase activity, offering a route to improved phosphorus mobilization in low-input agricultural systems (Doydora et al., 2020).

3.2. Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria (PSB)

PSBs mobilize phosphorus indirectly by releasing organic acids such as gluconic, oxalic, or citric acid into the rhizosphere. These acids chelate metal ions (e.g., Ca2+, Fe3+, Al3+) bound to phosphate compounds, thereby solubilizing mineral phosphates including those associated with phytate complexes. Although PSBs do not produce phytase enzymes, their acidification of the soil environment can synergistically enhance phytate accessibility by loosening its mineral binding. Co-inoculants combining PDB and PSB have shown promise in increasing overall phosphorus release and uptake in field conditions (Sharma et al., 2025).

3.3. Challenges in Field Application

Despite their potential, microbial inoculants often face limitations under field conditions:

- ☐

Microbial survival is challenged by competition from native soil microbiota and environmental stresses such as drought, salinity, or nutrient imbalance (Abdul Rahman et al., 2021).

- ☐

Enzyme inactivation may occur due to adsorption onto clay particles or organic matter, reducing phytase mobility and effectiveness (Menezes-Blackbum et al., 2013).

- ☐

Inconsistent results in different soil types highlight the need for site-specific strain selection and formulation strategies (Lee and Thierfelder 2017).

Emerging solutions include biofilm-forming strains, encapsulated microbial formulations, rhizosphere engineering, and microbiome-guided selection of native soil consortia. Together, these microbial tools provide a foundation for sustainable phosphorus management, especially when integrated with crop-based genetic approaches.

4. Limitations of Soil-Based Phytate Utilization Strategies

Despite the promise of microbial interventions in releasing phosphorus from phytate, several challenges hinder their consistent effectiveness in field conditions.

Limited Phytate Availability in Soil

Phytate primarily originates from plant residues and manure, and its accumulation depends on continuous organic matter input. In intensively managed or low-input systems, phytate levels may be insufficient to sustain long-term microbial activity and phosphorus release (Friedel and Ardakani 2021).

Enzyme Inactivation in Soil

Once secreted, phytase enzymes may bind to soil particles, particularly clay and humic substances, reducing their mobility and activity. This limits the efficiency of phytate hydrolysis in complex soil environments (Liu et al., 2022).

Competition and Survival of Microbes

Introduced biofertilizer strains (e.g., PSB or phytate degraders) may struggle to survive, colonize, or outcompete native microbes in diverse soil ecosystems, especially under stress conditions like drought, salinity, or nutrient imbalance (Dey et al., 2021).

Environmental Factors

Soil pH, temperature, moisture, and organic carbon content significantly influence enzyme activity and microbial viability. For instance, phytase works optimally under mildly acidic conditions, which may not be present in all agricultural soils (Liu et al., 2022).

Slow Phosphorus Release Rate

Even with active microbial populations, the rate of phosphorus release from phytate is gradual, making it difficult to match crop phosphorus demand during critical growth stages (Liu et al., 2022).

5. Genetic Engineering Perspective

While microbial phytase can unlock soil-bound phytate, the phytate stored within plant seeds remains inaccessible unless the plant itself is modified to produce phytase. Genetic engineering offers a promising solution to address this internal phosphorus bottleneck (Li et al., 2024).

5.1. Phytase Gene Sources and Transformation Methods

Phytate, which stores up to 80% of the total phosphorus in plant seeds, remains largely unavailable due to the lack of endogenous phytase enzymes in most plant species (Liu et al., 2022). Phytase genes have been cloned from various microorganisms, including Aspergillus niger, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp., and Citrobacter braakii. These microbial genes are typically more efficient than plant-derived ones due to higher catalytic activity and broader pH stability. Gene constructs are introduced into plant genomes via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or particle bombardment (gene gun) techniques (Wang et al., 2025). Crop species that have successfully been engineered to express phytase include maize, rice, soybean, canola, and Arabidopsis thaliana. These transgenic lines have demonstrated improved phosphorus uptake, increased seedling vigor, and greater biomass under low-phosphorus conditions (Venkataram and Hefferon 2023; Wang et al., 2025).

5.2. Expression Control and Subcellular Targeting

The efficiency of phytase activity in transgenic crops depends heavily on where and when the gene is expressed. Promoters such as seed-specific (e.g., globulin-1, oleosin) or constitutive (e.g., CaMV 35S) are commonly used. Seed-specific promoters are preferred to avoid unnecessary expression in vegetative tissues, which may disrupt normal metabolism (Wang et al., 2025). Targeting phytase enzymes to specific subcellular compartments, such as the vacuole, endoplasmic reticulum, or apoplast, enhances enzyme stability and prevents premature degradation. Recent innovations include fusion protein tags and multi-gene cassettes that optimize localization and controlled release of phosphate from phytate (Yassitepe et al., 2021). These transgenic plants demonstrated increased phytate degradation, improved phosphorus remobilization, and enhanced biomass accumulation under low-phosphorus conditions (Li et al., 2024; Mamun et al., 2024).

5.3. Benefits and Biosafety Concerns

Transgenic phytase crops offer several agronomic and environmental benefits according to Reddy et al., 2017:

- ☐

Enhanced use of internal phosphorus stores.

- ☐

Reduced need for external phosphorus fertilizers.

- ☐

Lower phytate levels in seeds, improving mineral bioavailability for human and animal nutrition.

However, regulatory and public acceptance issues remain major hurdles. Concerns about gene flow, ecological impact, and food safety often slow the approval and adoption of genetically modified crops. Addressing these concerns requires transparent risk assessments, strict biosafety testing, and communication strategies that emphasize the environmental benefits of reduced fertilizer dependency.

5.4. Toward Smart Engineering

Emerging strategies include tissue-specific inducible expression, CRISPR-based promoter tuning, and stacking phytase genes with phosphorus transporter genes to improve uptake and redistribution. These approaches allow for more precise phosphorus mobilization without compromising plant growth or yield (Rajendran et al., 2015). When combined with microbial interventions, genetically engineered crops can serve as the second arm of an integrated strategy for sustainable phosphorus cycling.

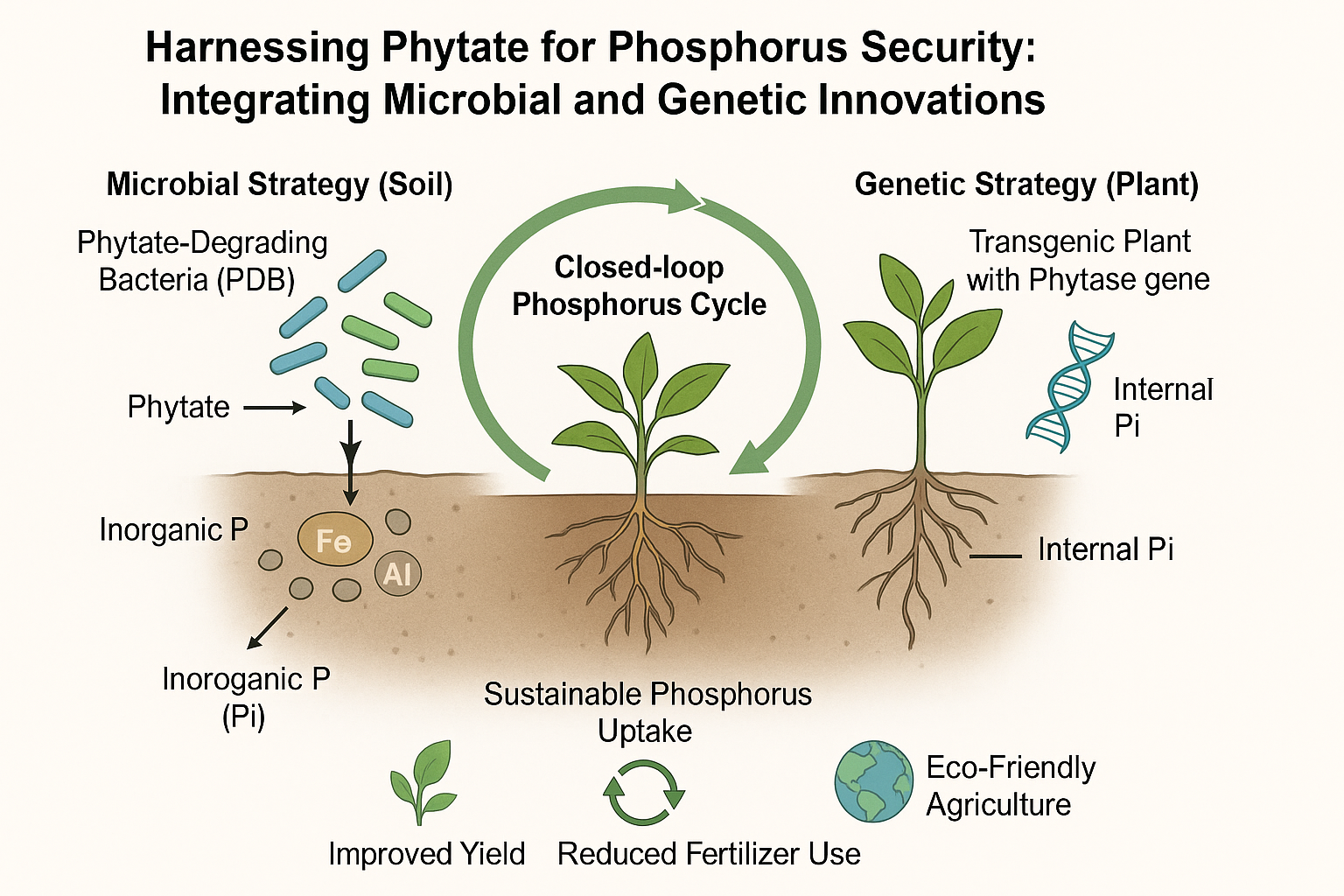

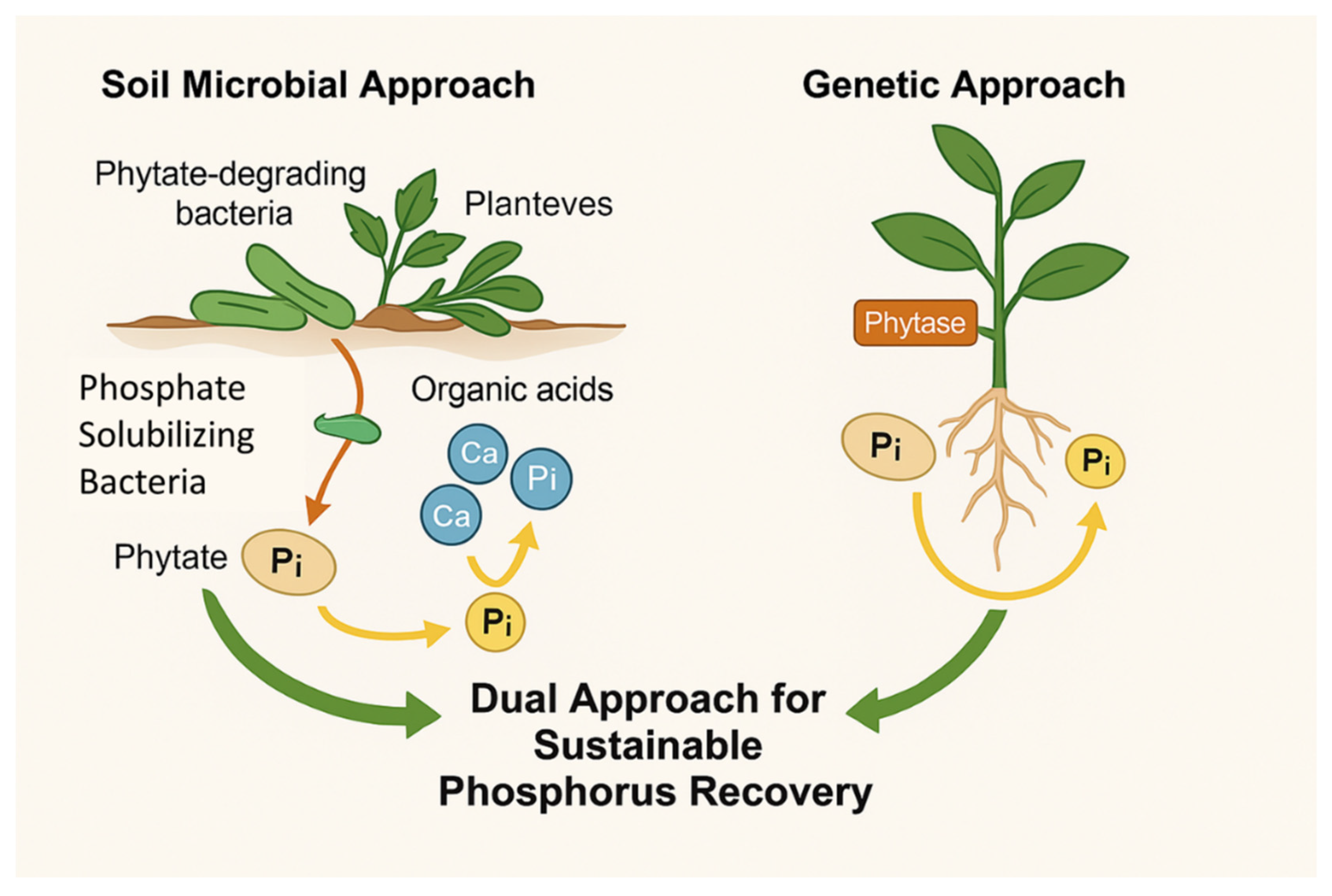

6. Integrative Model: A Dual Strategy for Sustainable Phosphorus Cycling

Given the complementary strengths of microbial inoculants and genetically engineered crops, we propose an integrated dual-strategy model for maximizing phytate utilization in agricultural systems (

Table 2). This model targets two major pools of phosphorus, soil-bound and seed-stored phytate, through a coordinated approach involving soil microbiology and plant biotechnology (

Figure 1).

6.1. Soil Microbial Approach (Harnessing Phytate-Degrading Bacteria and PSBs)

Soil-dwelling phytate-degrading bacteria (PDB) and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) play a critical role in releasing phosphorus from complex, insoluble forms. PDBs produce phytase enzymes that hydrolyze organic phytate compounds present in soil, while PSBs secrete organic acids that solubilize inorganic phosphorus sources like tricalcium phosphate (Liu et al., 2022). Together, these microbial populations improve phosphorus bioavailability and promote plant growth. For practical implementation, soils can be enriched with a mixed inoculum containing both PDBs and PSBs. Additionally, incorporating plant residues—such as roots, leaves, and seed husks—serves as a renewable phytate source, sustaining microbial activity over time. This not only recycles on-farm organic waste but also reduces dependence on synthetic phosphorus fertilizers derived from finite rock phosphate reserves.

6.2. Genetic Approach (Engineering Crops with Phytase Genes)

In parallel, genetically engineered crops expressing microbial phytase genes can hydrolyze seed-stored phytate during germination and early growth. This enables plants to mobilize internal phosphorus reserves, improving early vigor and reducing phosphorus deficiency stress. These transgenic crops also benefit from the enhanced soil phosphorus made available through microbial activity, resulting in a dual uptake pathway that increases overall phosphorus use efficiency (Reddy et al., 2017). By combining cutting-edge plant biotechnology with ecological soil management, this integrated strategy supports not only reduced fertilizer dependency but also improved crop performance and long-term soil fertility. It represents a scalable and sustainable model adaptable to both low-input and high-efficiency agricultural systems.

7. Future Perspectives

To realize the full potential of integrated microbial and genetic strategies for sustainable phosphorus use, several key research and development areas must be addressed.

Microbial Strain Optimization and Field Adaptation:

Future research should focus on isolating robust phytate-degrading and phosphate-solubilizing microbes that can thrive in diverse soil types and climates. The use of native, site-specific strains with proven rhizosphere colonization abilities will be critical. Metagenomics and functional screening can help identify microbial candidates with enhanced phytase activity and stress tolerance.

Development of Resilient Transgenic Crops:

Genetic engineering should move beyond single-gene transformations to multigenic strategies that stack phytase with other phosphorus-related traits, such as enhanced transporter expression or organic acid exudation. Advances in genome editing tools like CRISPR/Cas can enable precise control of gene expression and tissue targeting, reducing unintended effects.

Field Validation and Formulation Technologies:

Lab-to-field translation remains a major bottleneck. Therefore, microbial inoculants must be formulated for stability, shelf-life, and compatibility with farming practices. Similarly, genetically engineered plants should be tested under real-world conditions, including low-input systems, to validate their performance and adaptability.

Regulatory Harmonization and Public Engagement:

For widespread adoption, biosafety regulations and risk assessments must be standardized and streamlined across countries. Public concerns surrounding GM crops must be addressed through transparent communication of environmental benefits, such as reduced fertilizer use and improved soil health.

Integration with Smart Farming:

The future of phosphorus management lies in the integration of microbiome-based strategies and genetic innovations with precision agriculture tools. Sensors, remote monitoring, and AI-driven soil diagnostics can help apply microbial or genetic interventions when and where they are most needed.

By advancing these areas, it is possible to create a resilient, circular phosphorus system that meets the demands of modern agriculture while preserving ecological integrity.

8. Conclusions

Phytate represents a largely untapped reservoir of organic phosphorus in both soils and seeds. However, its inaccessibility to plants due to enzymatic limitations has long posed a challenge to sustainable phosphorus management. This review highlights a dual-strategy approach that combines soil microbial inoculants—specifically phytate-degrading and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria—with genetically engineered crops capable of internal phytase expression. While each strategy offers unique advantages, their integration presents a promising pathway toward closing the agricultural phosphorus loop. Microbial interventions unlock soil-bound phytate, while transgenic crops reclaim internal reserves, together enhancing phosphorus use efficiency and reducing dependency on finite rock phosphate resources. To move from concept to practice, interdisciplinary collaboration is needed across microbiology, plant genetics, field agronomy, and policy-making. With continued innovation and responsible deployment, these approaches have the potential to transform phosphorus management into a more circular, resilient, and environmentally sustainable system. This dual framework is not just a technological fix, but a necessary step toward redefining how we feed the world while preserving the planet’s limited resources.

Author Contributions

A.A.M. oversaw the entire project, and all authors gave their approval to the final manuscript. A.A.M. conceptualized and planned the study, carried out the analysis, wrote the manuscript, and created the graphs and illustrations. S.T.R. and S.K. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

There was no fund available.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author Abdullah Al Mamun is responsible for all data and materials.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the department of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering for supporting this research

Code Availability

There was no code available.

Ethics declarations

This review article does not include any studies by any of the authors that used human or animal participants. All authors are conscious and accept responsibility for the manuscript. No part of the manuscript content has been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Abdul Rahman, N. S. N.; Abdul Hamid, N. W.; Nadarajah, K. Effects of abiotic stress on soil microbiome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(16), 9036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mamun, A.; Rahman, M. M.; Huq, M. A.; Rahman, M. M.; Rana, M. R.; Rahman, S. T.; Alam, M. K. Phytoremediation: A transgenic perspective in omics era. Transgenic Research 2024, 33(4), 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, M. S.; Shahzad, S. M.; Yasmeen, T.; Riaz, M.; Ashraf, M.; Ashraf, M. A.; Kausar, R. Improving plant phosphorus (P) acquisition by phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Essential plant nutrients: uptake, use efficiency, and management 2017, 513–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Qureshi, I.; Bangroo, S.; Mahdi, S. S.; Sheikh, F. A.; Bhat, M. A.; Lone, A. A. Reduction of Phytic Acid and Enhancement of Bioavailable Micronutrients in Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Changing Climatic Scenario. In Developing Climate Resilient Grain and Forage Legumes; Springer Nature Singapore; Singapore, 2022; pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N. P.; Suleimanova, A. D.; Valeeva, L. R.; Chastukhina, I. B.; Rudakova, N. L.; Sharipova, M. R.; Shakirov, E. V. Microbial phytases and phytate: exploring opportunities for sustainable phosphorus management in agriculture. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, G.; Banerjee, P.; Sharma, R. K.; Maity, J. P.; Etesami, H.; Shaw, A. K.; Chen, C. Y. Management of phosphorus in salinity-stressed agriculture for sustainable crop production by salt-tolerant phosphate-solubilizing bacteria—A review. Agronomy 2021, 11(8), 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doydora, S.; Gatiboni, L.; Grieger, K.; Hesterberg, D.; Jones, J. L.; McLamore, E. S.; Duckworth, O. W. Accessing legacy phosphorus in soils. Soil systems 2020, 4(4), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H.; Tang, M.; Xie, X. Cross-talks between macro-and micronutrient uptake and signaling in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 663477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, J. K.; Ardakani, M. R. Soil nutrient dynamics and plant-induced nutrient mobilisation in organic and low-input farming systems: conceptual framework and relevance. Biological Agriculture & Horticulture 2021, 37(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenback, A. J. High-Resolution Study on Degradation and Isotope Effects of Inositol Phosphates in Soils; University of Delaware, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Illakwahhi, D. T.; Vegi, M. R.; Srivastava, B. B. L. Phosphorus’ future insecurity, the horror of depletion, and sustainability measures. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2024, 21(14), 9265–9280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Siddique, A. B.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, C. Phosphorus plays key roles in regulating plants’ physiological responses to abiotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12(15), 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dash, G. K.; Sahoo, S. K.; Lal, M. K.; Sahoo, U.; Sah, R. P.; Lenka, S. K. Phytic acid: A reservoir of phosphorus in seeds plays a dynamic role in plant and animal metabolism. Phytochemistry Reviews 2023, 22(5), 1281–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Anand, R. Effect of germination and temperature on phytic acid content of cereals. Int. J. Res. Agric. Sci 2021, 8, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.; Thierfelder, C. Weed control under conservation agriculture in dryland smallholder farming systems of southern Africa. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2017, 37(5), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tian, J.; Chen, X.; Liao, H. Bioengineering and management for efficient and sustainable utilization of phosphorus in crops. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2024, 90, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Han, R.; Cao, Y.; Turner, B. L.; Ma, L. Q. Enhancing phytate availability in soils and phytate-P acquisition by plants: a review. Environmental Science & Technology 2022, 56(13), 9196–9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Blackburn, D.; Jorquera, M. A.; Greiner, R.; Gianfreda, L.; de la Luz Mora, M. Phytases and phytase-labile organic phosphorus in manures and soils. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2013, 43(9), 916–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohite, B. V.; Koli, S. H.; Borase, H. P.; Rajput, J. D.; Narkhede, C. P.; Patil, V. S.; Patil, S. V. New age agricultural bioinputs. Microbial Interventions in Agriculture and Environment 2019, Volume 1, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cai, B. Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria: advances in their physiology, molecular mechanisms and microbial community effects. Microorganisms 2023, 11(12), 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguet, P.; Houot, S.; Montenach, D.; Mollier, A.; Ziadi, N.; Karam, A.; Morel, C. Soil organic phosphorus mineralisation rate in cropped fields receiving various P sources. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapitamahuni, S.; Kang, B. R.; Lee, T. K. Exploring the roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant–iron homeostasis. Agriculture 2023, 13(10), 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S. R. C. K.; Yau, Y. Y.; Pandey, D.; Kumar, A. CRISPR-Cas9 based genome engineering: opportunities in agri-food-nutrition and healthcare. Omics: a journal of integrative biology 2015, 19(5), 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C. S.; Kim, S. C.; Kaul, T. Genetically modified phytase crops role in sustainable plant and animal nutrition and ecological development: a review. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; AnandKumar, L. H. D.; Tyagi, A.; Muthumilarasan, M.; Kumar, K.; Gaikwad, K. An insight into phytic acid biosynthesis and its reduction strategies to improve mineral bioavailability. The Nucleus 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U. C.; Datta, M.; Sharma, V. Chemistry, Microbiology, and Behaviour of Acid Soils. In Soil Acidity: Management Options for Higher Crop Productivity; Springer Nature Switzerland; Cham, 2025; pp. 121–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Cao, T.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ying, Y. Phosphorus deficiency promotes root morphological and biochemical changes to enhance phosphorus uptake in Phyllostachys edulis seedlings. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, A.; Tehri, N.; Tehri, P.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, A. K.; Kumar, V. Unraveling the potential of bacterial phytases for sustainable management of phosphorous. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry 2023, 70(5), 1690–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataram, V.; Hefferon, K. Agricultural Biotechnology: Genetic Engineering for a Food Cause; Elsevier, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, M.; Schenk, G.; Schmidt, S. Realising the circular phosphorus economy delivers for sustainable development goals. npj Sustainable Agriculture 2023, 1(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Si, H.; Li, C.; Xu, Z.; Guo, H.; Jin, S.; Cheng, H. Plant genetic transformation: achievements, current status and future prospects. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassitepe, J. E. D. C. T.; da Silva, V. C. H.; Hernandes-Lopes, J.; Dante, R. A.; Gerhardt, I. R.; Fernandes, F. R.; Arruda, P. Maize transformation: From plant material to the release of genetically modified and edited varieties. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 766702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).