1. Introduction

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a Gram-negative, facultative halophilic bacterium that inhabits estuaries and brackish water worldwide [

1]. It thrives in warm water conditions above 15 °C and sodium chloride concentrations below 25 ppm, with a rapid doubling time of 8-9 minutes [

2]. During the summertime, the bacterium can accumulate quickly in filter-feeding aquatic organisms, such as oysters [

3]. Consequently,

V. parahaemolyticus is a leading cause of gastroenteritis in humans, primarily associated with the consumption of contaminated seafood [

4]. According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 84,000 cases of foodborne illness are caused by

Vibrio infection annually in the United States [

3,

4]. For instance, a specific strain of

V. parahaemolyticus was identified as a causative agent for an outbreak across 13 Northeastern states in 2012 and 2013, which was associated with oyster consumption [

5,

6]. This outbreak had significant public health and economic repercussions, particularly for the local seafood industry [

7].

Several virulence factors are known to play key roles in

V. parahaemolyticus infection, including proteases, lipopolysaccharides, thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH), TDH-related hemolysin (TRH), and type III secretion system [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Among these, TDH and TRH are regarded as critical markers for identifying pathogenic strains, as they are commonly found in clinical isolates from patients but are rare in environmental strains [

8,

13,

14,

15,

16]. A genomic study has demonstrated that 90 % of clinical strains possess the

tdh and/or

trh gene, compared to less than 1 % of environmental strains [

17]. Due to a 67 % similarity in the amino acid sequences, TDH and TRH share similar pathogenic mechanisms causing pore formation in gastrointestinal cell membranes [

9,

18]. This leads to massive ion and water efflux, resulting in symptoms such as diarrhea. Therefore, the simultaneous detection of

tdh and

trh genes is essential for predicting the pathogenicity of

V. parahaemolyticus strains [

19,

20,

21]. Given the global concern over

V. parahaemolyticus contamination in seafood, there is an urgent need to develop rapid, sensitive, and specific detection tools for field applications.

Our previous study demonstrated that the multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification (MIRA), combined with lateral flow dipstick assay (LFD), could effectively detect the thermolabile hemolysin (

tlh) gene, a marker for identifying

V. parahaemolyticus, as well as two pathogenic marker

tdh and

trh genes separately, without requiring a laboratory setting [

22]. The entire MILA-LFD process was completed within 20 minutes at temperatures ranging from 30 to 45 °C, exhibiting high specificity and sensitivity comparable to real-time PCR. MIRA is a recombinase-based nucleic acid technique which employs three key enzymes, including recombinase proteins to form nucleoprotein filaments with target-specific primers and facilitate strand invasion into double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (SSBs) to stabilize the displaced strand and prevent re-annealing, and strand-displacing DNA polymerase to extend the primers once bound, synthesizing new DNA without high-temperature denaturation in a single-tube reaction [

22,

23,

24]. MIRA amplifies and tags target DNA in one step using primers and probes labeled with haptens, such as FAM (fluorescein amidite), and biotin or digoxigenin. During LFD step, hapten-labeled amplicons bind to conjugated antibodies on a nitrocellulose membrane, producing visible bands at the test lines that indicate the presence of target genes, while a control line confirms proper flow and reagent function. Therefore, MIRA-LFD is well suited for on-site pathogen detection in resource-limited settings without specialized laboratory infrastructure.

In this study, we developed a duplex MIRA-LFD assay capable of simultaneously detecting two pathogenic markers, tdh and trh, using specifically modified primers and probes. The sensitivity of the assay was evaluated using extracted DNA, direct bacterial culture, and oyster samples artificially infected with bacteria. Furthermore, the specificity of the assay was assessed by testing various Vibrio strains and foodborne pathogens. This assay provides a rapid and practical tool for screening the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus in oysters, complementing our previously developed MILA-LFD assay for the tlh gene, an identification marker.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and DNA Extraction

The reference strain

Vibrio parahaemolyticus F11-3A, which contains both

tdh and

trh genes, was used in this study [

19,

21].

V. parahaemolyticus ATCC 35118 strain was used as a

tdh-positive strain, while

V. parahaemolyticus ATCC 17802 served as a negative control for both genes [

25,

26]. For the determination of specificity of MIRA-LFD, additional closely related

Vibrio species and foodborne pathogens were tested. These included

V. vulnificus ATCC 33147,

V. vulnificus ATCC 27562,

V. vulnificus ATCC 33815,

V. metschnikovii,

V. fluvialis ATCC 33809,

V. mimicus ATCC 33655,

V. furnissii ATCC 35627,

V. cholerae ATCC 39315,

V. alginolyticus ATCC 33840,

Escherichia coli ATCC 51739,

E. coli K-12,

E. coli O157:H7 ATCC 43895,

Listeria monocytogenes F5069,

Lactobacillus buchneri ATCC 12936,

Listeria innocua ATCC 33090,

Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium 14028,

S. enterica Serovar Gaminara F2712,

S. enterica Serovar Montevideo ATCC BAA-1735,

S. enterica Serovar Senftenburg ATCC 43845,

S. enterica Serovar Enteritidis E190-88,

S. enterica Serovar Choleraesuis ATCC 10708,

Bacillus subtilis ATCC 9372,

Clostridium perfringens ATCC 13124,

Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 344,

Lactobacillus acidophilus NRRL B1910,

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, and

Shigella flexineri ATCC 12022. All bacterial strains were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Remel, San Diego, CA, USA) or on tryptic soy agar (TSA, Remel) at 37 °C. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), and DNA concentrations were measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The DNA samples were kept at -20 °C until further use.

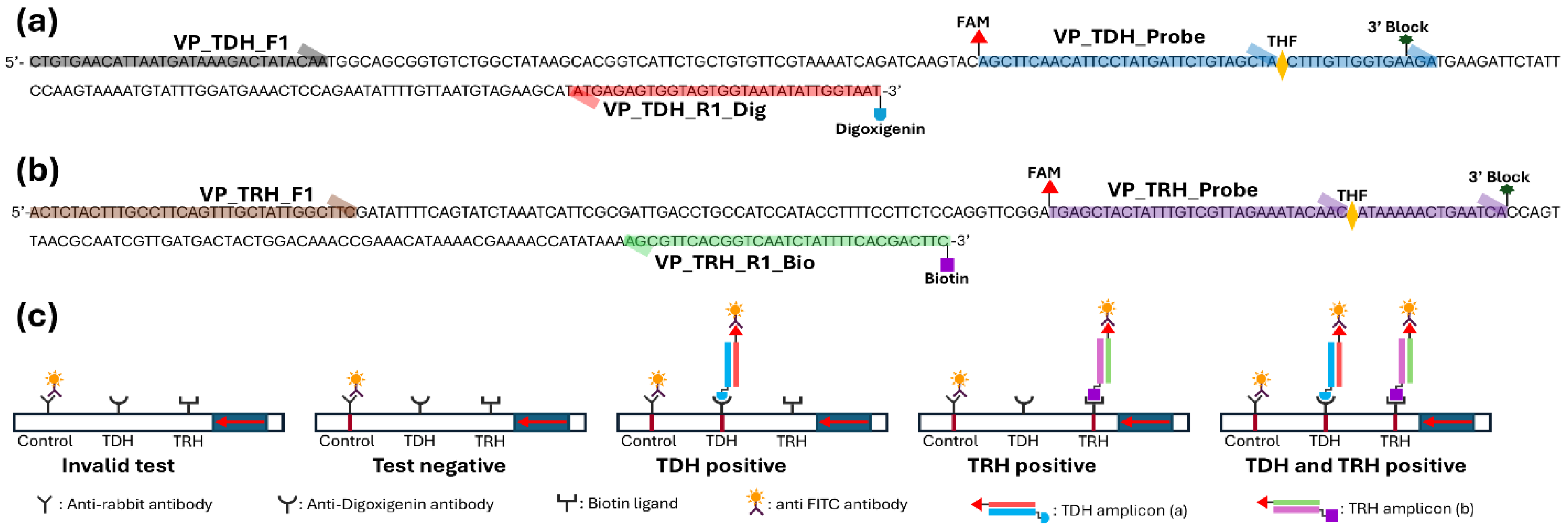

2.2. Primers and Probes

The

tdh (Gene ID: 1192010) and

trh (GenBank: KP836460.1) were used to design the primers and probes using SnapGene software (version 5.2, San Diego, CA, USA).

Table 1 provides the genetic information for the forward and reverse primer, as well as the probes used to amplify fragments of

tdh and

trh genes. The probes were labeled with a polymerase extension blocking group (C3 spacer) at the 5’ end, an internal abasic nucleotide analog (dSpacer tetrahydrofuran residue), and a carboxyfluorescein (FAM). The 5’ ends of reverse primers were labeled with either digoxigenin or biotin to enable attachment to the lateral flow dipsticks (LFD, HybriDetect 2T, Milenia Biotec, Giessen, Germany). The LFD features two test lines with anti-digoxigenin antibody and biotin ligand, which capture the amplicons labeled with digoxigenin or biotin.

2.3. Multienzyme Isothermal Rapid Amplification (MIRA) and Lateral-Flow Dipstick (LFD)

The MIRA-LFD assay was conducted using MIRA nfo kit (Amp-future, Changzhou, China) in a combination with lateral flow dipsticks (LFD, HybriDetect 2T, Milenia Biotec, Giessen, Germany). A 47.5 µL of MIRA mixture was prepared, consisting of 29.4 µL of Buffer A, 2 µL of each forward and reverse primer (10 µM) for both genes, 0.6 µL of each probe (10 µM), 1 µL of template and 7.9 µL of water (

Table 1). This mixture was added to a test tube containing a lyophilized pellet. The MIRA reaction was carried out at 40 °C for 16 min by adding 2.5 µL of MgAc (280 mM). Then, 5 µL of the MIRA product was diluted in 195 µL of HybriDetect 2T assay buffer. The LFD sample pad was immersed in the diluted solution and incubated for 1.5 minutes. A clear control line, with or without test lines, was considered valid.

2.4. Optimization of MIRA-LFD Assay

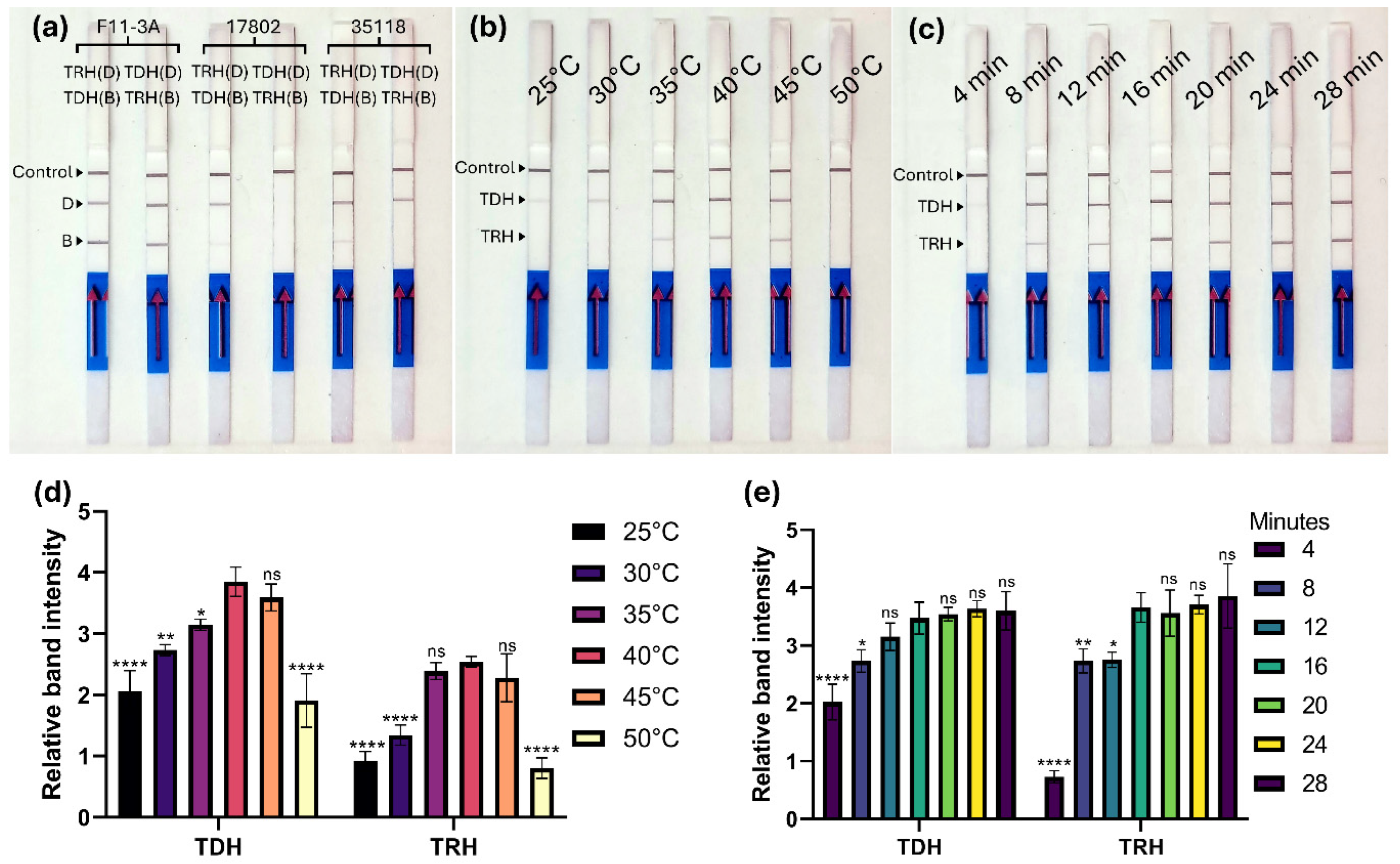

Two different primer combinations were examined for simultaneous amplifications of

trh and

tdh genes of

V. parahaemolyticus using F11-3A DNA in a MIRA reaction (

Table 1). The amplified reactions, containing either

trh-digoxigenin and

tdh-biotin or

trh-biotin and

tdh-digoxigenin, were loaded onto LFD strips to confirm the presence of both test lines along with a control line. The incubation temperatures for MIRA reactions were set at 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 °C. Additionally, the optimal incubation time was evaluated at durations of 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 28 minutes.

2.5. Sensitivity and Specificity of MIRA-LFD Assay

To evaluate the sensitivity of MIRA-LFD, both genomic DNA (ranging from 1 fg to 1 ng per reaction) and direct bacterial cultures (ranging from 3 × 10

1 to 3 × 10

5 CFU per reaction) of F11-3A were used. Fresh oysters were purchased from a local market, shucked, pooled, blended, and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at a ratio of 1:4 (w/v). After confirming the absence of

V. parahaemolyticus using a PCR assay [

20], the oyster samples were seeded with F11-3A bacteria in concentrations ranging from 3 × 10

1 to 3 × 10

5 CFU for the MIRA-LFD assay. The specificity of the MIRA-LFD assay was evaluated by applying genomic DNA samples extracted from various

Vibrio and foodborne bacteria mentioned above.

2.6. Multiplex PCR

A conventional multiplex PCR targeting the

tlh,

tdh, and

trh genes was performed to compare its sensitivity with that of the MIRA-LFD assay [

19,

27]. PCR reactions (50 µL) contained bacterial genomic DNA (1 fg–1 ng), 0.25 µM of each primer (1.25 µL of a 10 µM stock), 320 µM of each dNTP (8 µL of an 8 mM stock), 5 µL of 10× DreamTaq Green PCR buffer, 1.5 U DreamTaq Green DNA polymerase (0.3 µL of 5 U/µL; Thermo Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania), and nuclease-free water to volume. Thermal cycling was carried out on a standard PCR thermocycler as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 58 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Amplified products were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels in TBE buffer (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA) containing SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). The gel was electrophoresed for 45 min and visualized with a Gel Doc XR+ imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Test-band intensities were quantified using Image Lab™ v6.0.1 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and normalized to the negative-control value. All statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism™ v9 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Differences between groups were assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparisons test, with p < 0.05 considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of Primers and Probes

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a leading cause of foodborne illness in humans through the consumption of contaminated seafood, such as oysters [

4]. Since most environmental

V. parahaemolyticus strains are non-pathogenic, distinguishing them from pathogenic strains carrying the

trh and/or

tdh genes is crucial for seafood safety [

19,

28]. According to the U.S. FDA Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM) and the National Shellfish Sanitation Program (NSSP), DNA hybridization, PCR, and real-time PCR assays are the recommended methods for detecting

trh- and

tdh-positive strains in oyster samples [

20,

29]. However, these standard techniques are not well-suited for field applications due to their reliance on specialized laboratory infrastructure, equipment, and technical expertise.

Recombinase-based isothermal amplification assay, including multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification (MIRA) and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) offers significant advantages for on-site pathogen detection in field conditions without the need for specialized training or laboratory equipment [

30]. In their lyophilized form, these assays are easy to transport and enable target gene amplification at relatively low incubation temperatures (30–45 °C) using a simple heat block or even body heat [

31]. Recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of simultaneous amplification of multiple target genes in a single RPA reaction, such as Genus

Clavibacter and

C. nebraskensis,

Campylobacter jejuni and

C. coli,

Listeria monocytogenes and

Salmonella enteritidis, as well as

Staphylococcus aureus,

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and

Salmonella Enteritidis [

32,

33,

34,

35]. This study is the first to report the simultaneous detection of two representative pathogenic genes from

V. parahaemolyticus using the MIRA-LFD assay.

The primer sets and probes demonstrated 100% query coverage and 100% identity with both target genes (data not shown). Based on a previous study, the primer design criteria were established as follows: GC content ranging from 20 to 70%, annealing temperature between 50 and 100 °C, primer length between 30 and 36 bp, and a maximum allowable nucleotide repeat length of five [

22]. The forward primers, reverse primers (tagged with biotin or digoxigenin), and probes (tagged with FAM) generated amplicons labeled with 5’ FAM and 3’ biotin or digoxigenin (

Table 1 and

Figure 1). Upon interaction with anti-FAM antibodies, the amplicons were captured at two distinct lines on the LFD pad: the upper line (anti-digoxigenin) and the lower line (anti-biotin) (

Figure 1c). The control line on the LFD pad was visualized by capturing anti-FAM antibodies, and any results lacking a control line were deemed invalid. A valid MIRA-LFD assay can display possible outcomes: test negative,

tdh-positive,

trh-positive, and dual

trh/

tdh-positive.

Three

V. parahaemolyticus strains—F11-3A (

tdh+/

trh+), ATCC 17802 (

tdh-/

trh-), and ATCC 35118 (

tdh+/

trh-)—were used to evaluate primer sets and probes for the simultaneous amplification of

tdh and

trh fragments in a MIRA-LFD assay [

19,

21,

25,

26]. Prior to developing the dual MIRA-LFD assay, the primer sets and probes for each gene were evaluated using single-target MIRA-LFD assays. These assays yielded valid results without false positives or false negatives (data not shown). Dual MIRA-LFD assays were then tested using two different primer combinations: (1)

trh primers tagged with digoxigenin (TRH(D)) and

tdh primers tagged with biotin (TDH(B)), and (2)

tdh primers tagged with digoxigenin (TDH(D)) and

trh primers tagged with biotin (TRH(B)) (

Figure 2a). Both combinations produced positive results on the LFD strip when using the DNA template of F11-3A (

tdh+/

trh+), with amplicons captured at the anti-digoxigenin (D) and anti-biotin (B) lines. However, combination (1) produced false-positive

tdh+/

trh+ results for ATCC 17802 (

tdh-/

trh-) and ATCC 35118 (

tdh+/

trh-). By contrast, combination (2) correctly identified ATCC 17802 as

tdh-/

trh- and ATCC 35118 as

tdh+/

trh-.

Previous studies have reported that recombinase-based isothermal amplification assays can produce false-positive results due to competition among primers and probes for recombinase proteins, as well as primer-dimer formation during multi-target amplification [

32,

33,

35,

36]. Although optimization of primer and probe concentrations has been suggested to mitigate false positives, adjusting the concentrations of primers, probes, and MgAc in combination (1) failed to eliminate false amplification in this study (data not shown). By contrast, combination (2), in which

tdh and

trh primers were tagged with digoxigenin and biotin, respectively, did not exhibit false-positive amplification. These findings suggest that modifying the tagging materials in primer sets can effectively prevent false amplification in duplex MIRA-LFD assays. This approach provides a potential solution for improving the specificity and reliability of multi-target isothermal amplification assays.

3.2. Optimization of MIRA-LFD

Multiplex target gene amplification assays enable the simultaneous detection of multiple gene fragments in a single reaction, reducing operational steps, saving time, and minimizing reagent use [

37]. Commonly used multiplex technologies include multiplex PCR, real-time PCR, and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [

38,

39,

40]. Recently, the MIRA assay has emerged as a promising tool for rapid and reliable multiplex detection, offering advantages such as high tolerance to sample impurities, lower amplification temperatures compared to PCR (up to 95 °C) and LAMP (up to 65 °C), and significantly shortened incubation times [

23,

36]. However, due to the rapid amplification achieved by MIRA-LFD (lateral flow detection), optimizing incubation time and temperature is critical to maximize efficiency and minimize false-positive and false-negative results.

Figure 2b and 2d illustrate the results of duplex MIRA amplification across incubation temperatures ranging from 25 to 50 °C. The duplex MIRA assay was performed for 20 minutes using 1 ng of

V. parahaemolyticus F11-3A genomic DNA as the template. While the control line remained consistent across all lateral flow detection (LFD) strips,

tdh and

trh band intensities varied with temperature. The

tdh band first appeared at 25 °C, intensified up to 40 °C, and weakened at 45 °C. By contrast, the

trh band was observed only at 35, 40, and 45 °C, while no amplification detected for both gene at 50 °C. Previous studies have also reported temperature-dependent variations in MIRA amplification efficiency. For example, MIRA targeting

Spiroplasma eriocheiris failed to amplify at 30 °C and 40 °C [

23], whereas MIRA for

Acinetobacter baumannii was successful at 25 °C and 50 °C [

41]. These findings indicate that 40 °C is the optimal temperature for simultaneous

tdh and

trh detection using MIRA-LFD (

p < 0.05).

To determine the optimal amplification time, MIRA reactions were conducted at 40 °C using 1 ng of F11-3A genomic DNA, with incubation times ranging from 4 to 28 minutes at 4-minute intervals (

Figure 2c and 2e). Both

tdh and

trh bands appeared after 8 minutes, with distinct, intense bands observed at 16 minutes. Band intensities remained consistent at 16, 20, 24, and 28 minutes, confirming that 16 minutes was the optimal amplification time (

p < 0.05). For LFD detection, an incubation time of 1.5 minutes was selected, as no significant differences in band intensity were observed beyond this duration (data not shown), which was consistent with previous findings [

22]. In summary, the optimized MIRA-LFD assay enabled the detection of

tdh and

trh genes within a total reaction time of 20 minutes.

3.3. Sensitivity and Specificity of MIRA-LFD Assay

Surveillance of pathogenic

Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood is crucial for ensuring food safety and protecting the local seafood industry [

3,

4,

7,

42]. Recombinase-based isothermal amplification assays have been recognized as highly sensitive and specific tools for detecting foodborne pathogens under field conditions [

30,

36]. In this study, we evaluated the detection limits of our assay using various template concentrations and assessed its specificity against different pathogenic bacteria.

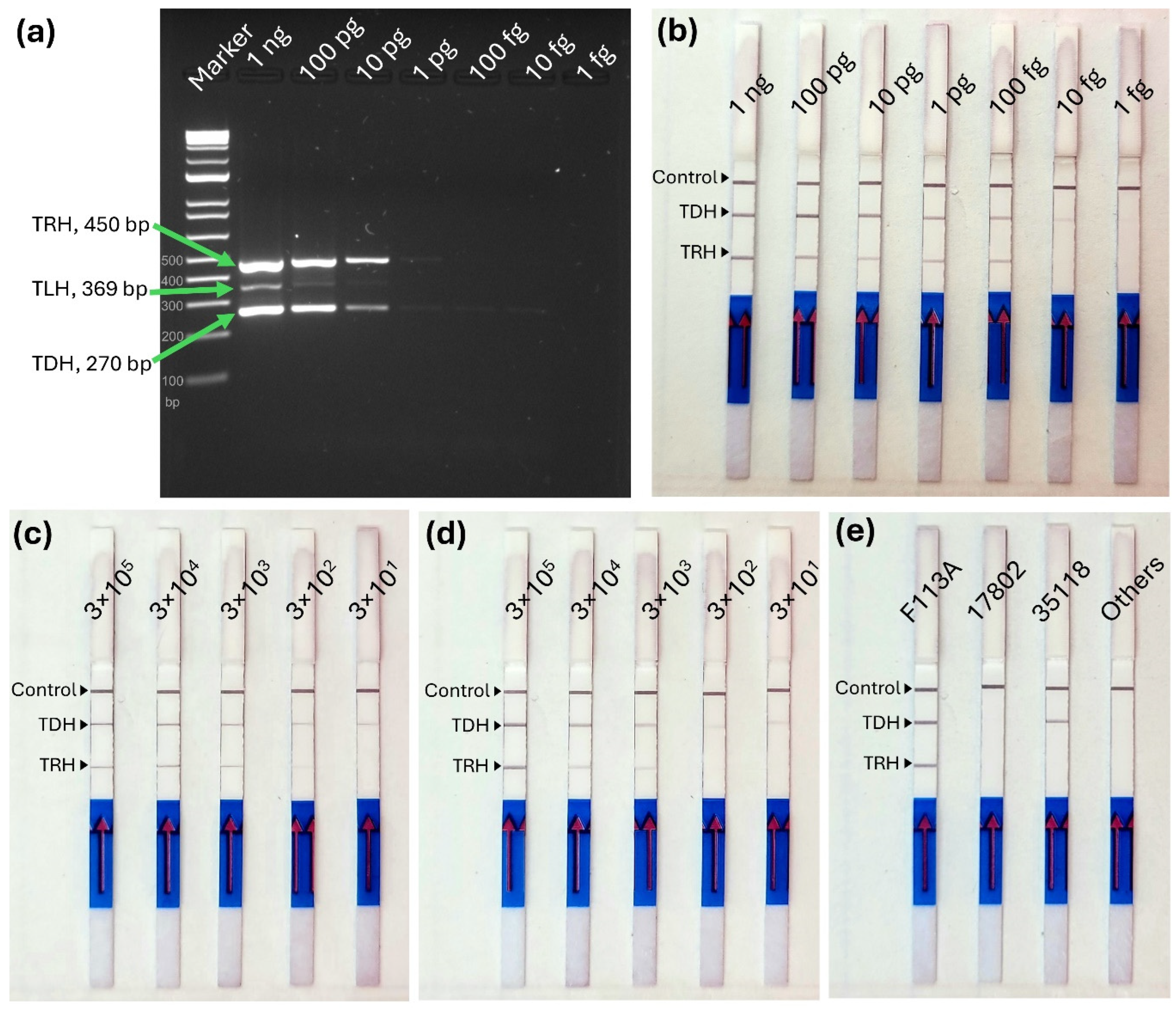

To determine the sensitivity of the MIRA-LFD assay, genomic DNA and bacterial cultures of

V. parahaemolyticus strain F11-3A (

tdh+ / trh+) were used as templates. Additionally, artificially contaminated oyster samples were prepared to assess detection limits in a food matrix. Templates were serially diluted (10-fold) and subjected to MIRA-LFD analysis. Clear visualization of control and two test lines on the LFD strip indicated a

tdh and

trh positive result, while only the control line signified a negative result. While the multiplex PCR detected both

tdh and

trh genes down to 100 fg (

Figure 3a), the MIRA-LFD assay improved sensitivity by detecting

tdh gene at 10 fg and

trh gene at 100 fg, yielding an overall detection limit of 100 fg for both genes (

Figure 3b). Notably, a recent multiplex PCR-LFD assay targeting

tlh and

tdh genes of

V. parahaemolyticus demonstrated detection limits of 0.39 ng of bacterial DNA [

43], highlighting that MIRA is more sensitive than conventional multiplex PCR-based assays for simultaneous detecting

V. parahaemolyticus genes. In direct culture and seeded oyster samples, positive bands were observed at detection limits of 300 CFU/reaction and 3,000 CFU/reaction, respectively (

Figure 3c and 3d). Previous MIRA-LFD studies have reported detection limits ranging from 97 pg to 64 fg of genomic DNA and 760 to 6 CFU for bacterial cultures of various pathogens [

23,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Similarly, a multiplex RPA-LFD assay exhibited a 10-fold higher detection limit in direct culture (2.8 to 7.6 × 10

2 CFU/ml) than in artificially contaminated food samples (2.8 to 7.6 × 10

3 CFU/ml), suggesting that food matrix inhibitors, including polysaccharides, polyphenols, and elevated magnesium levels in fruits, vegetables, and seafood can impair MIRA reaction [

48,

49]. Therefore, after initial detection in complex food matrices, it is advisable to confirm target genes using purified bacterial DNA.

The specificity of the duplex MIRA-LFD assay was evaluated using nine

Vibrio species and 18 foodborne pathogenic bacteria (

Figure 3e and Supplemental

Figure 1). The assay correctly identified

tdh+ / trh+ for strain F11-3A,

tdh- / trh- for ATCC 17802, and

tdh+ / trh- for ATCC 35118, demonstrating its ability to specifically amplify target genes in different

V. parahaemolyticus strains. No cross-reactivity was observed with other

Vibrio species or foodborne pathogens. While

Vibrio species are known to exchange genetic elements, including pathogenic genes, and the

tdh and

trh genes of

V. parahaemolyticus share high sequence similarity with those of

Vibrio alginolyticus, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio mimicus, and

Vibrio hollisae [

50,

51,

52,

53], the MIRA-LFD assay exhibited no false positives or negatives. This specificity was likely due to the use of long primers (approximately 35 bp) and the unique recombinase-driven amplification system of MIRA, ensuring precise targeting of

tdh and

trh genes. However, further evaluation of this assay using clinical and environmental samples is necessary to verify its detection efficacy.

4. Conclusions

A duplex MIRA-LFD assay was developed for the rapid detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by targeting the tdh and trh genes, key pathogenic markers associated with foodborne illness from oyster consumption. This assay provides visually interpretable results within 20 minutes at 40 °C using target-specific primer sets, making it a simple and efficient tool for field applications. With its high sensitivity and specificity, the MIRA-LFD assay may hold great potential for monitoring the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus, not only to prevent foodborne outbreaks but also to support the local seafood industry by ensuring product safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., S.C and Y.Z.; methodology, S.P. L.B, and Y.C.; software, S.P.; formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, S.P.; resources, L.B and Y.C.; data curation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, S.C and Y.Z.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, S.C and Y.Z. ; funding acquisition, S.C and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by USDA-ARS-SCA agreement number 58-6066-7081 and state CRIS project number MIS 081710 for MS Center for Food Safety and Postharvest Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, R.; Zhong, Y.; Gu, X.; Yuan, J.; Saeed, A.F.; Wang, S. The pathogenesis, detection, and prevention of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Frontiers in microbiology 2015, 6, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Trinanes, J.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Non-cholera vibrios: the microbial barometer of climate change. Trends in microbiology 2017, 25, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePaola, A.; Nordstrom, J.L.; Bowers, J.C.; Wells, J.G.; Cook, D.W. Seasonal abundance of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Alabama oysters. Applied and environmental microbiology 2003, 69, 1521–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froelich, B.A.; Noble, R.T. Vibrio bacteria in raw oysters: managing risks to human health. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 371, 20150209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Baker-Austin, C.; Jones, J.L.; Newton, A.E.; Gonzalez-Aviles, G.D.; DePaola, A. Spread of Pacific northwest Vibrio parahaemolyticus strain. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 369, 1573–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.E.; Garrett, N.; Stroika, S.G.; Halpin, J.L.; Turnsek, M.; Mody, R.K. Notes from the field: increase in Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections associated with consumption of atlantic coast shellfish-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014, 63, 335–336. [Google Scholar]

- DePaola, A. Managing Vibrio Risk in Oysters. Food Protection Trends 2019, 39, 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez West, C.K.; Klein, S.L.; Lovell, C.R. High frequency of virulence factor genes tdh, trh, and tlh in Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated from a pristine estuary. Applied and environmental microbiology 2013, 79, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Meng, H.; Gu, D.; Li, Y.; Jia, M. Molecular mechanisms of Vibrio parahaemolyticus pathogenesis. Microbiological Research 2019, 222, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tong, J.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Yuan, M.; Tian, C.; Xu, H.; Malakar, P.K.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Natural inhibitors targeting the localization of lipoprotein system in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Ono, T.; Rokuda, M.; Jang, M.H.; Okada, K.; Iida, T.; Honda, T. Functional characterization of two type III secretion systems of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Infection and immunity 2004, 72, 6659–6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirai, H.; Ito, H.; Hirayama, T.; Nakamoto, Y.; Nakabayashi, N.; Kumagai, K.; Takeda, Y.; Nishibuchi, M. Molecular epidemiologic evidence for association of thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH) and TDH-related hemolysin of Vibrio parahaemolyticus with gastroenteritis. Infection and immunity 1990, 58, 3568–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broberg, C.A.; Calder, T.J.; Orth, K. Vibrio parahaemolyticus cell biology and pathogenicity determinants. Microbes and infection 2011, 13, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, T.; Iida, T. The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct haemolysin and related haemolysins. Reviews and Research in Medical Microbiology 1993, 4, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongping, W.; Jilun, Z.; Ting, J.; Yixi, B.; Xiaoming, Z. Insufficiency of the Kanagawa hemolytic test for detecting pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Shanghai, China. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease 2011, 69, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.H.; Costa, R.A.; Menezes, F.G.; Silva, G.C.; Theophilo, G.N.; Rodrigues, D.P.; Maggioni, R. Kanagawa-negative, tdh-and trh-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from fresh oysters marketed in Fortaleza, Brazil. Current microbiology 2011, 63, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongjun, J.; Mittraparp-Arthorn, P.; Yingkajorn, M.; Kongreung, J.; Nishibuchi, M.; Vuddhakul, V. The trend of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in Southern Thailand from 2006 to 2010. Tropical medicine and health 2013, 41, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, K.; Nakahira, K.; Unzai, S.; Mayanagi, K.; Hashimoto, H.; Shiraki, K.; Honda, T.; Yanagihara, I. Relationship between heat-induced fibrillogenicity and hemolytic activity of thermostable direct hemolysin and a related hemolysin of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. FEMS microbiology letters 2011, 318, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bej, A.K.; Patterson, D.P.; Brasher, C.W.; Vickery, M.C.; Jones, D.D.; Kaysner, C.A. Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tl, tdh and trh. Journal of microbiological methods 1999, 36, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaysner, C.A.; DePaola, A.; Jones, J. Bacteriological analytical manual chapter 9: Vibrio. Food and Drug Administration, Maryland.[https://www. fda. gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/bam-chapter-9-vibrio]. Reviewed: December 2004, 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom, J.L.; Vickery, M.C.; Blackstone, G.M.; Murray, S.L.; DePaola, A. Development of a multiplex real-time PCR assay with an internal amplification control for the detection of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteria in oysters. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2007, 73, 5840–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.B.; Zhang, Y. Development of multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification (MIRA) combined with lateral-flow dipstick (LFD) assay to detect species-specific tlh and pathogenic trh and tdh genes of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Pathogens 2024, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Luan, X.; Gong, S.; Ma, Y.; Gu, W.; Du, J.; Meng, Q. Development and application of the MIRA and MIRA-LFD detection methods of Spiroplasma eriocheiris. J Invertebr Pathol 2023, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, C.; Feng, Y.; Sun, R.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Pan, Z.; Yao, H. Development of a multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification and lateral flow dipstick combination assay for bovine coronavirus detection. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 1059934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, W.A. Laboratory Method for Vibrio parahaemolyticus (V.p.) Enumeration and detection through MPN and real-time PCR in proceedings of the interstate shellfish sanitation conference (ISSC) Columbia, SC 29223-1740 2015.

- Rizvi, A.V.; Bej, A.K. Multiplexed real-time PCR amplification of tlh, tdh and trh genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its rapid detection in shellfish and Gulf of Mexico water. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2010, 98, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Zhang, Y. Innovative multiplex PCR assay for detection of tlh, trh, and tdh genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus with reference to the US FDA’s Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM). Pathogens 2024, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, J.; Kaysner, C.; Blackstone, G.; Vickery, M.; Bowers, J.; DePaola, A. Effect of intertidal exposure on Vibrio parahaemolyticus levels in Pacific Northwest oysters. Journal of food protection 2004, 67, 2178–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Shellfish Sanitation Program (NSSP)—Guide for the Control of Molluscan Shellfish 2023 Revision. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/federal-state-local-tribal-and-territorial-cooperative-human-food-programs/national-shellfish-sanitation-program-nssp (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Daher, R.K.; Stewart, G.; Boissinot, M.; Bergeron, M.G. Recombinase polymerase amplification for diagnostic applications. Clinical chemistry 2016, 62, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crannell, Z.A.; Rohrman, B.; Richards-Kortum, R. Equipment-free incubation of recombinase polymerase amplification reactions using body heat. PloS one 2014, 9, e112146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.L. Development of a multiplex real-time recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) assay for rapid quantitative detection of Campylobacter coli and jejuni from eggs and chicken products. Food control 2017, 73, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrea-Sarmiento, A.; Stack, J.P.; Alvarez, A.M.; Arif, M. Multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification assay developed using unique genomic regions for rapid on-site detection of genus Clavibacter and C. nebraskensis. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.B.; Du, X.J.; Zang, Y.X.; Li, P.; Wang, S. SERS-based lateral flow strip biosensor for simultaneous detection of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica serotype enteritidis. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2017, 65, 10290–10299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Li, J.; Chen, K.; Yu, X.; Sun, C.; Zhang, M. Multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification assay for the simultaneous detection of three foodborne pathogens in seafood. Foods 2020, 9, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, M.; Liao, C.; Liang, L.; Yi, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wei, G. Recent advances in recombinase polymerase amplification: Principle, advantages, disadvantages and applications. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 12, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, H. Monoplex and multiplex immunoassays: approval, advancements, and alternatives. Comparative clinical pathology 2022, 31, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.E.; Razzak, M.A.; Hamid, S.B.A. Multiplex PCR in species authentication: probability and prospects—a review. Food Analytical Methods 2014, 7, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becherer, L.; Borst, N.; Bakheit, M.; Frischmann, S.; Zengerle, R.; von Stetten, F. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)–review and classification of methods for sequence-specific detection. Analytical Methods 2020, 12, 717–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitmann, L.; Miglietta, L.; Xu, K.; Malpartida-Cardenas, K.; D'Souza, G.; Kaforou, M.; Brengel-Pesce, K.; Drazek, L.; Holmes, A.; Rodriguez-Manzano, J. Next-generation molecular diagnostics: Leveraging digital technologies to enhance multiplexing in real-time PCR. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 160, 116963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.W.; He, J.W.; Guo, S.L.; Li, J. Development and evaluation of a rapid and sensitive multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification with a lateral flow dipstick assay for detection of Acinetobacter baumannii in spiked blood specimens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2022, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, S.L.; DePaola, A.; Jaykus, L.A. An overview of Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety 2007, 6, 120–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saetang, J.; Sukkapat, P.; Palamae, S.; Singh, P.; Senathipathi, D.N.; Buatong, J.; Benjakul, S. Multiplex PCR-Lateral Flow Dipstick Method for Detection of Thermostable Direct Hemolysin (TDH) Producing V. parahaemolyticus. Biosensors 2023, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, P.; Liu, J.; Song, Z.; Wu, C.; Yu, X.; He, Y. Rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus using a novel multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification technique. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 1027785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Yao, J.; Yuan, S.; Liu, H.; Wei, N.; Zhang, J.; Shan, W. Development of a lateral flow recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid and visual detection of Cryptococcus neoformans/C. gattii in cerebral spinal fluid. BMC infectious diseases 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Niu, J.; Sun, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Qi, J. Rapid and sensitive detection of Streptococcus iniae in Trachinotus ovatus based on multienzyme isothermal rapid amplification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Gong, F.; Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Yu, Y.; Shu, J.; Pan, Z. Integrating filter paper extraction, isothermal amplification, and lateral flow dipstick methods to detect Streptococcus agalactiae in milk within 15 min. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2023, 10, 1100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; He, S.; Cui, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, X. Development of a multiplex recombinase polymerase amplification coupled with lateral flow dipsticks for the simultaneous rapid detection of Salmonella spp., Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Enteritidis. Food Quality and Safety 2024, 8, fyad059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Oh, S.W. A review of isothermal amplification methods and food-origin inhibitors against detecting food-borne pathogens. Foods 2022, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Kim, Y.O.; Kong, I.S. Multiplex PCR for the detection and differentiation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains using the groEL, tdh and trh genes. Molecular and cellular probes 2013, 27, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumiya, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Yahiro, S.; Lee, J.; Morita, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Arakawa, E.; Ohnishi, M. Multiplex PCR assay for identification of three major pathogenic Vibrio spp., Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus. Molecular and cellular probes 2011, 25, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishibuchi, M.; Janda, J.M.; Ezaki, T. The thermostable direct hemolysin gene (tdh) of Vibrio hollisae is dissimilar in prevalence to and phylogenetically distant from the tdh genes of other vibrios implications in the horizontal transfer of the tdh gene. Microbiology and immunology 1996, 40, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.C.; You, W.Y.; Chen, S.Y. Detection of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus in oyster by multiplex-PCR with internal amplification control. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2012, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).