1. Introduction

Oysters, traditionally harvested for thousands of years, are a very important part of many diets around the world [

1], and increasing as aquaculture oyster demands surge [

2]. Since 2009, the global production has increased from 3 million to over 5.9 million tons [

3]. This is an important factor contributing to the increase in the number of cases of gastroenteritis caused by the human pathogen

Vibrio parahaemolyticus (

Vp) [

4,

5], a bacteria endemic to marine environments and present in seafood including oysters [

6]. In addition to gastroenteritis, consuming oysters with high

Vp concentrations can lead to primary septicemia in individuals with underlying medical conditions such as chronic diseases, liver disease, or immune disorders [

7].

The first outbreak of

Vp was reported in Osaka (Japan) in 1950 and since then, a continuing rise of

Vp infections has been reported in several countries over the past few decades [

8,

9,

10]. Such

Vp cases increase is connected to an unknown occurrence of global Vibrio infections [

11]. In 2020, around half a million

Vp infection cases were estimated worldwide [

10], being this pathogen the leading cause of seafood-derived illnesses worldwide [

12].

It is almost impossible to obtain seafood free of these bacteria due to the ubiquitous nature of Vibrio species in marine and estuarine environments, particularly during warm, summer months [

13] and the accumulation of Vibrio by oysters through filter-feeding. Seawater temperature is a major factor determining the concentration, distribution, and proliferation of

Vp in the coastal environment [

13,

14]. Higher densities of

Vp in oysters have been detected in the spring and summer, and are positively correlated with seawater temperature [

13,

15].

Vp is rarely detected during winter when Vibrio survives in the marine sediment until temperatures rise again to 14ºC and it is released to the seawater [

2]. Oysters harvested in summer can be associated with

Vp tissue concentrations approaching 1000 CFU/g, while in winter this concentration decreases to less than 10 CFU/g [

13,

16].

Oysters are harvested, sacked, and left at ambient air temperature on the boat deck before being dragged to shore. When the air temperature is very high in hot summer conditions, this exposure can result in an important

Vp growth in oysters up to 50 × 10

6

cells/g (7.7

CFU/g) [

17]. Regarding disease risk, the probability of illness is relatively low in winter (

) for consumption of a serving of 12 oysters with 100 × 10

3 Vp cells (

cells/g or 1.7

CFU/g ) [

18]. However, in summer this probability can increase to

after the consumption of a serving with 100 × 10

6 Vp cells (∼ 500 × 10

3 cells/g or 5.7

CFU/g) [

18]. In this context, raising temperature associated with climate change is a factor of concern, due to the expected influence of prolonged exposure to seawater temperatures supporting Vibrio proliferation and its impact on

Vp distribution [

10,

11] and population dynamics, and eventually the impact on human disease outcomes.

To address this risk, worldwide sanitation programs for shellfish control established time-to-temperature regulations to limit the growth of

Vp in post-harvest oysters [

19]. An example of this thermal process consists of cooling down the shellfish harvested for raw consumption to 10ºC (50ºF) within 10, 12, or 36 hours when the average monthly air temperature is higher than 27ºC, between 19 and 27ºC or lower than 18ºC, respectively [

2]. An absence of refrigeration, non-rapid refrigeration, or breaking the cold chain can lead to high temperatures during oyster warehousing leading to

Vp in vivo population increase. Resubmersion can also be considered a method for vibrio control [

20]

This effect of temperature on

Vp has been commonly explored by experiments at different constant temperatures [

17,

21,

22]. However, inferring outcomes from constant-temperature experiments onto realistic varying temperature regimes is complex and problematic [

23]. Improving methods in this regard is essential for the understanding of this and similar temperature-dependent host-pathogen systems while supporting studies about the public health impact of pathogenic

Vp associated with raw seafood consumption [

17,

19,

24].

In this study, a continuous-time model was developed for predicting the growth of

Vp in oysters under varying ambient temperatures. The model was constructed by numerically integrating an ordinary differential equation system with temperature-dependent growth parameters. First, the model was fitted, verified, and evaluated against previous experimental data of

Vp concentrations in Pacific oysters (

Crassostrea gigas) at constant temperatures [

17]. Once the model was verified and evaluated,

Vp dynamics in oysters were modeled at different post-harvest scenarios under varying environmental temperatures for winter and summer initial conditions, and with and without dockside ice and onboard ice treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

The predictive model developed in this study for exploring

Vp growth in oysters under varying environmental temperatures was parameterized with and evaluated against experimental data of

Vp concentrations in Pacific oysters obtained at different constant temperatures (see details in [

17]). First, linear and non-parametric regression models were obtained. Second, from the maximum slopes of these models, the inactivation and growth rates were estimated. Third, using these rates, our growth model was constructed for predicting the growth of

Vp in oysters under varying ambient temperatures:

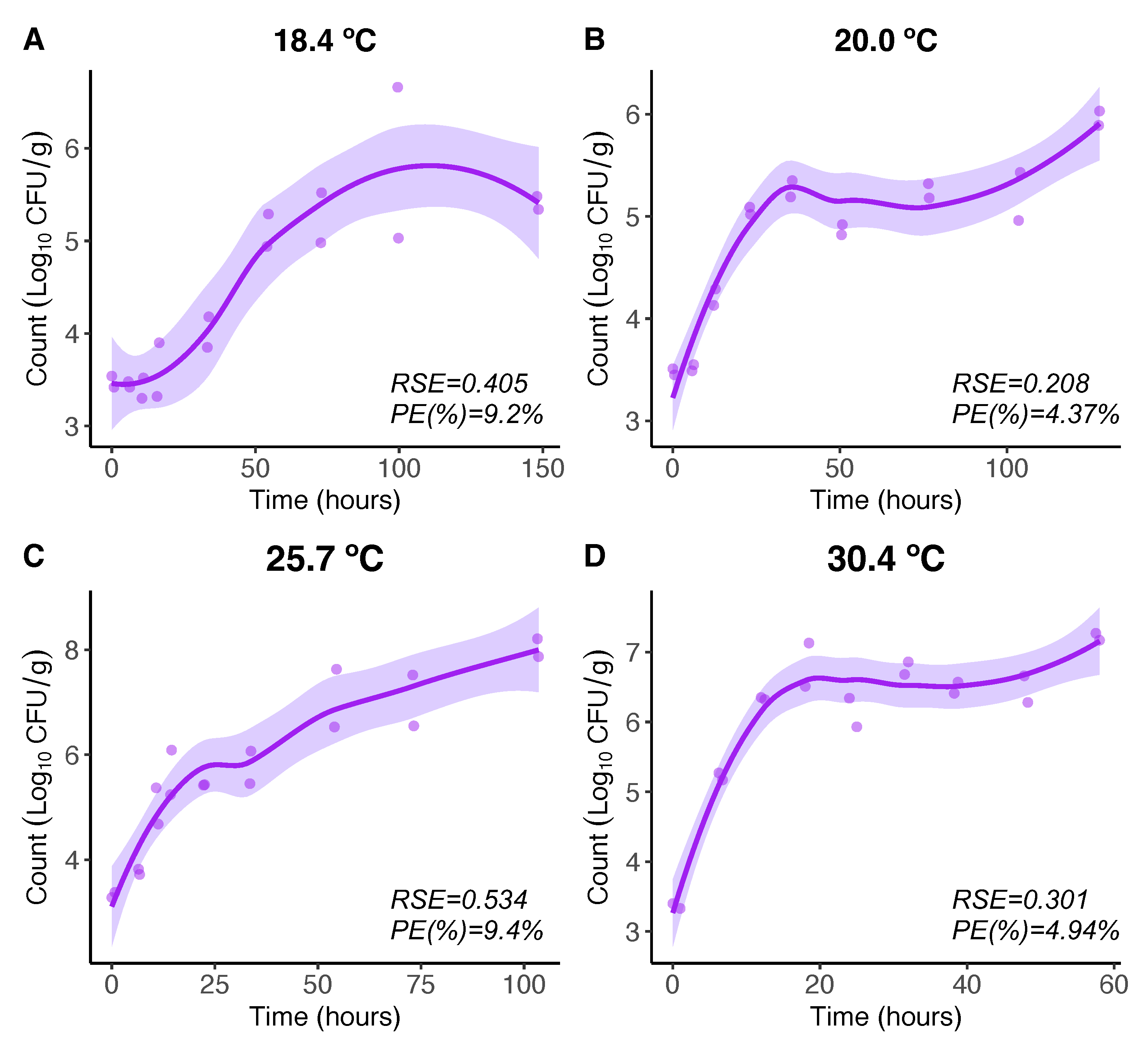

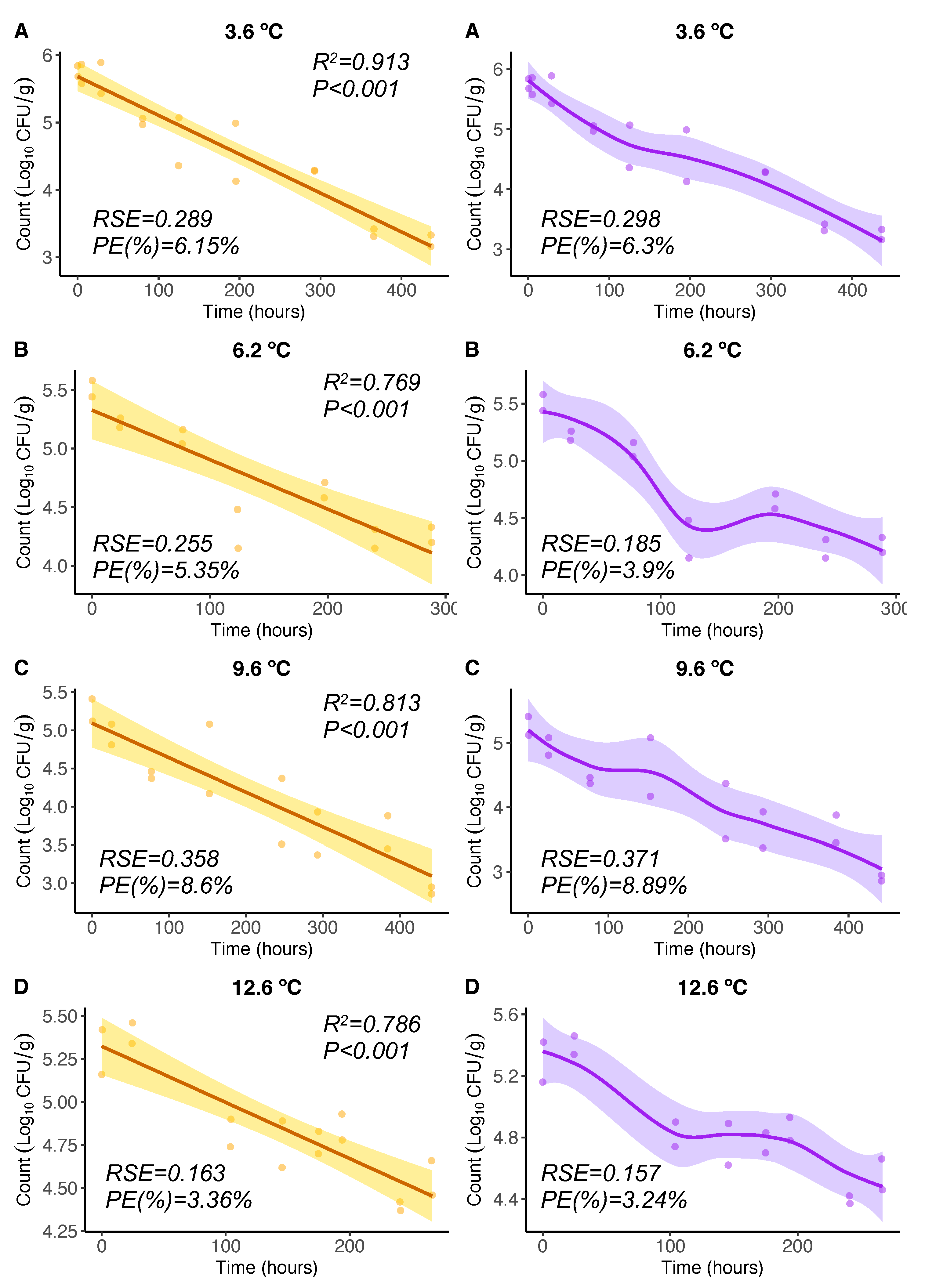

2.1. OLS and LOESS Regression Models for Vp Growth and Inactivation Processes

Two models were applied to analyze the relationship of

Vp concentration in oysters with time at experimental constant temperatures [

17]: the classic parametric Ordinary Least Squares regression model (OLS) (Galton, 1886) and the non-parametric Locally Weighted Least Squares Regression smoothing technique (LOESS) (Cleveland et al., 1988). As a non-parametric smoothing technique, the LOESS can model the relationship between Vp and time more robustly and in a more flexible manner than parametric models such as the OLS, potentially extracting information (e.g. ecological, biological) from the data that more restrictive parametric models miss. For

Vp inactivation, the goodness of fit of the OLS and LOESS regression curves were assessed and compared by analyzing the percentage error (

); a lower

meaning a better prediction accuracy. The

was calculated based on the residual standard error (

) as follows:

Where and are respectively the observed Vp and mean Vp counts in terms of colony forming units () and is the predicted counts by the OLS and LOESS models.

For

Vp growth, the goodness of fit of the LOESS regression curve was assessed. The obtained curves and the corresponding maximum slopes or growth rates were compared to the curves obtained by model fitting in [

17]. The PE was also calculated here based on the residual standard error.

Data analysis was conducted with R statistical software (R Core Team, 2018). The “ggplot2” package was used to generate plots.

2.2. Growth and Inactivation Rates for the Model

For

Vp growth, the classic square root model [

25] was applied to describe the growth rate (

r) as a function of temperature as follows:

The model shows a linear relationship between temperature (T) and the , where the regression coefficient is represented by a and is a hypothetical reference or threshold temperature between growth and inactivation of Vp.

The Arrhenius equation was used for the estimation of the kinetic parameters for the effect of temperature on bacterial inactivation as follows:

where

r is the reaction rate coefficient or constant,

T is the absolute temperature,

is the activation energy (i.e., the minimum amount of energy that must be provided to result in a reaction),

R is the universal gas constant, and

A is the collision factor.

2.3. The Model

2.3.1. Model Description, Mathematical Theory and Assumptions

The model developed here is a

Vp growth model for

Vp in oysters that accounts for the effect of varying temperature on bacterial growth. It is a continuous-time model, which results from an ordinary differential equation (ODE) system solved using a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method (RK4) [

26]. The numerical model for this ODE system is programmed in Matlab.

The model accounts for both bacterial growth and inactivation. Regarding bacterial growth, the model is an extension of the Logistic model [

27] which suggests that the rate of bacterial population increase is limited. The logistic model combines the ecological processes of growth and competition. Both processes depend on population density and their rates match the mass-action law [

27]. Regarding bacterial inactivation, the model is a linear decreasing model.

2.3.2. Model Equations

Vp growth and inactivation are described by the system and conditions defined by equations (

5) and (

6), being

the total number of

Vp counts per gram. That is, for having both

Vp growth and inactivation in the equation system for the variable

Vp population in oysters is divided into two classes

and

. The following equations represent the change of these two classes with time:

where

is the maximum growth rate of

Vp population in oysters (

).

accounts for substrate competition, that is, represents the carrying capacity or the maximum total counts, corresponding to 5.5

for lower temperatures (

), 7.5

for medium-high temperatures (

) and 6.75

for high temperatures (

) as observed by [

17]. The parameter

m can be 1 or 0, depending on the temperature (see equations (

7) and (

8)).

From equations (

3) and (

4), the following growth rates (

) were obtained:

The growth rate

and

m depend on temperature (

T) representing growth or inactivation of

Vp in oysters. That is, when

T is higher than

,

Vp population growth is defined by equation (

7), being

m=1 so that the first term in both equations (

5) and (

6) are annulled. In these conditions, the model studies the change in total

Vp population

or bacterial growth by the second term in equation (

6),

. While if

T is lower or equal to

, the growth rate

is defined by equation (

8), being

m=0. In this conditions, the change in total

Vp population (

or inactivation is only defined by

in equation (

5). The rest of the terms are annulled when

and the initial number of

.

2.3.3. Model Verification and Evaluation

The probability of illness is relatively low (

percent) for consumption of 10 × 10

3 cells/g

Vp cells/serving [

18], being a serving of 12 oysters or approximately 16 grams of meat. This is equivalent to about 50 cells/oyster meat gram; that is, 800 cells/serving. These concentrations are equivalent to winter CFU/g values [

13]. However, the probability of disease increases to 50 percent for consumption of about 100 × 10

6 Vp cells/serving. This corresponds to 8000 × 10

3 cells/oyster [

18], which are body burdens of the same order of magnitude as those found in oysters harvested in summer [

13].

Model verification consisted of showing that the model is correct, complete, and coherent by means of (i) static tests involving a structured examination of the formulas, algorithms, and code used to implement the model, and (ii) dynamic tests, where the computer program was run under different conditions to ensure that results produced were correct, according to the conceptual model, and consistent with expectations of reviewers experts in oyster pathology, Vp and population dynamics.

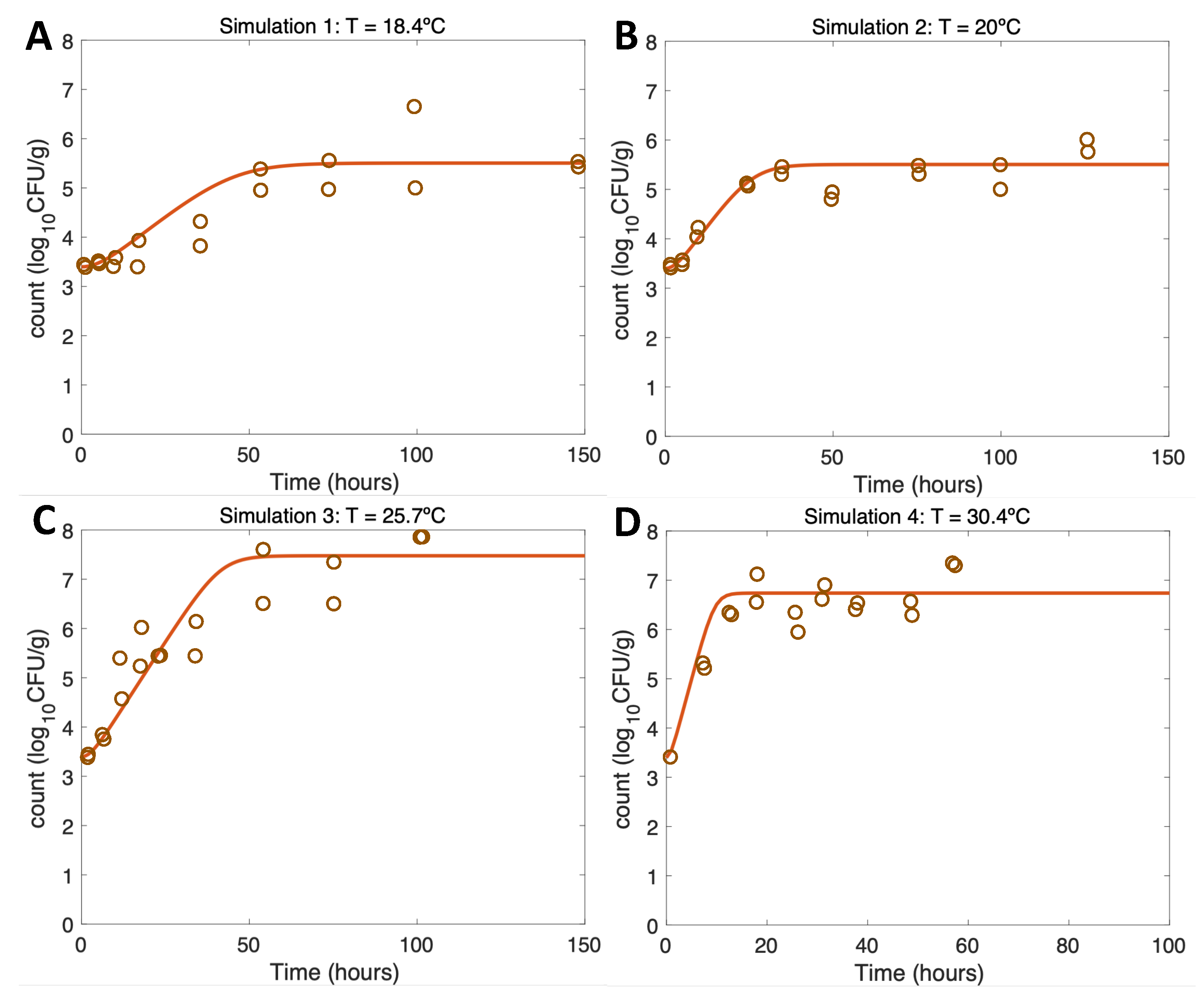

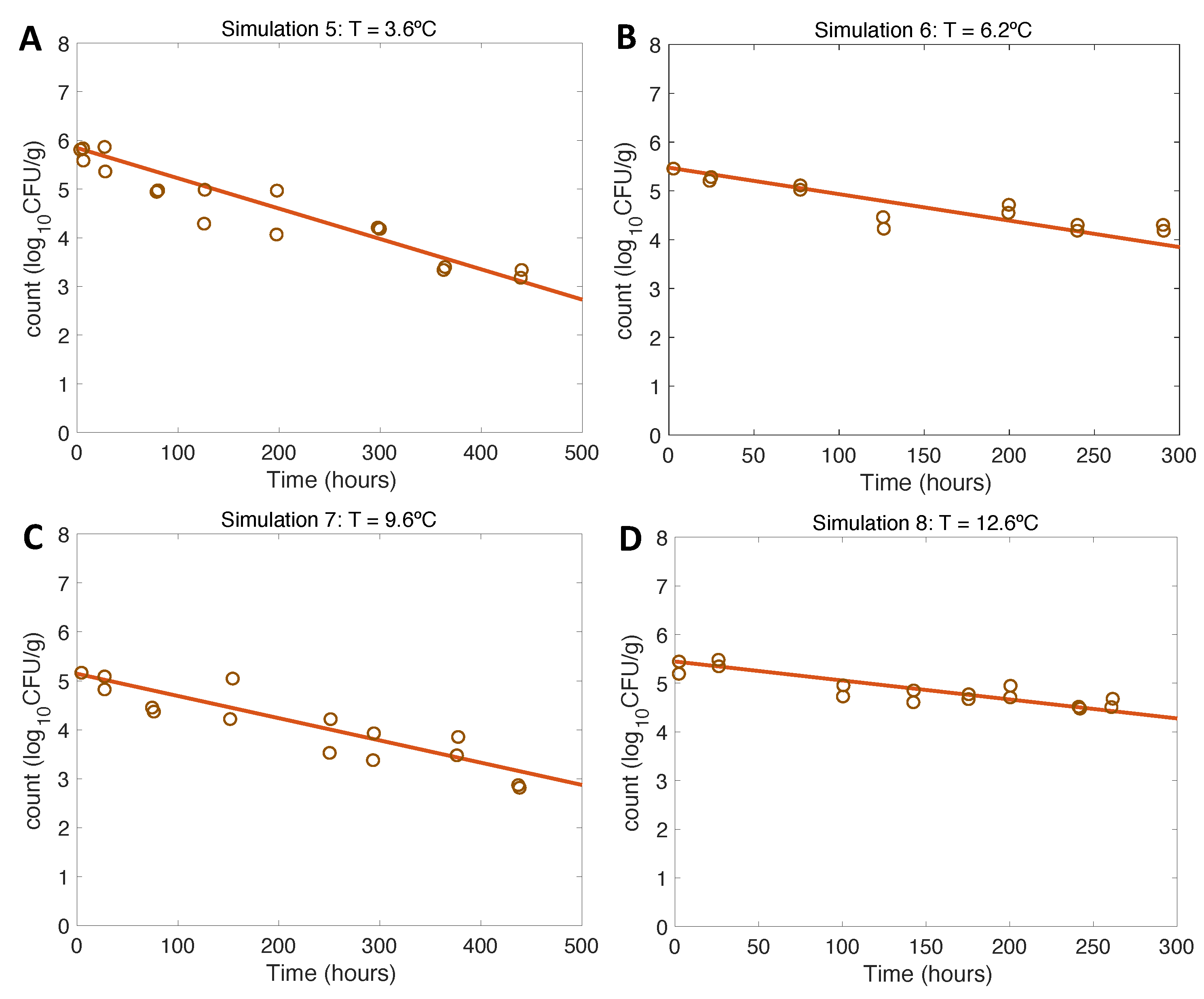

The parameter values used for model verification were those obtained by fitting the model growth and inactivation rate equations (Equations 5 and 6). The model was run for a series of 100/150-hour simulations for growth scenarios and 300/500-hour simulations for inactivation scenarios. This simulation time span was chosen (i) to detect pathogen proliferation and inactivation events, and (ii) to evaluate the model against growth and inactivation experimental data along the same time span [

17]. Thus, eight realistic (experimental) scenarios were simulated to verify and evaluate the performance of the model regarding the dynamics of

Vp population (

Table 1) [

17].

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the results of these verification/evaluation cases (simulations 1-8).

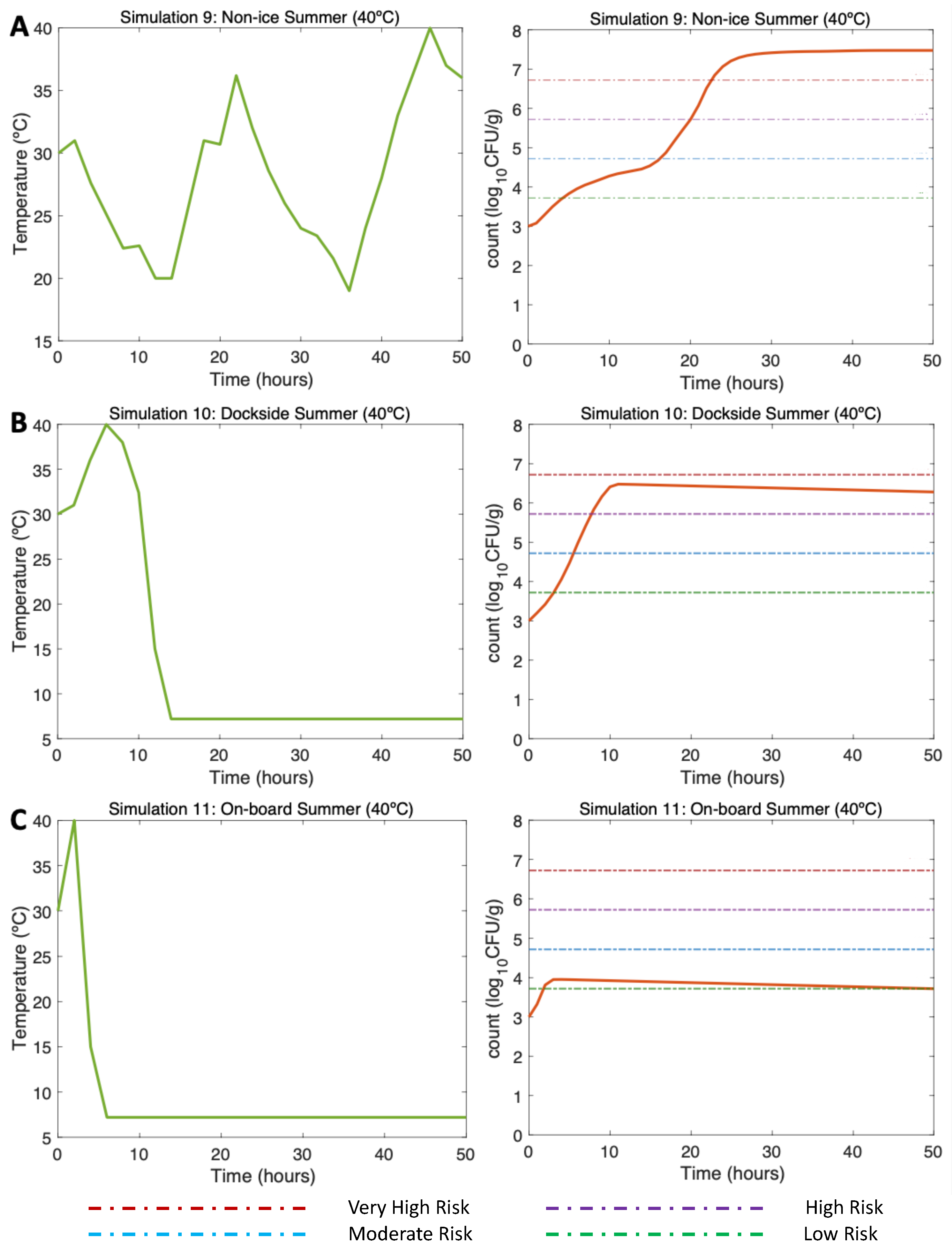

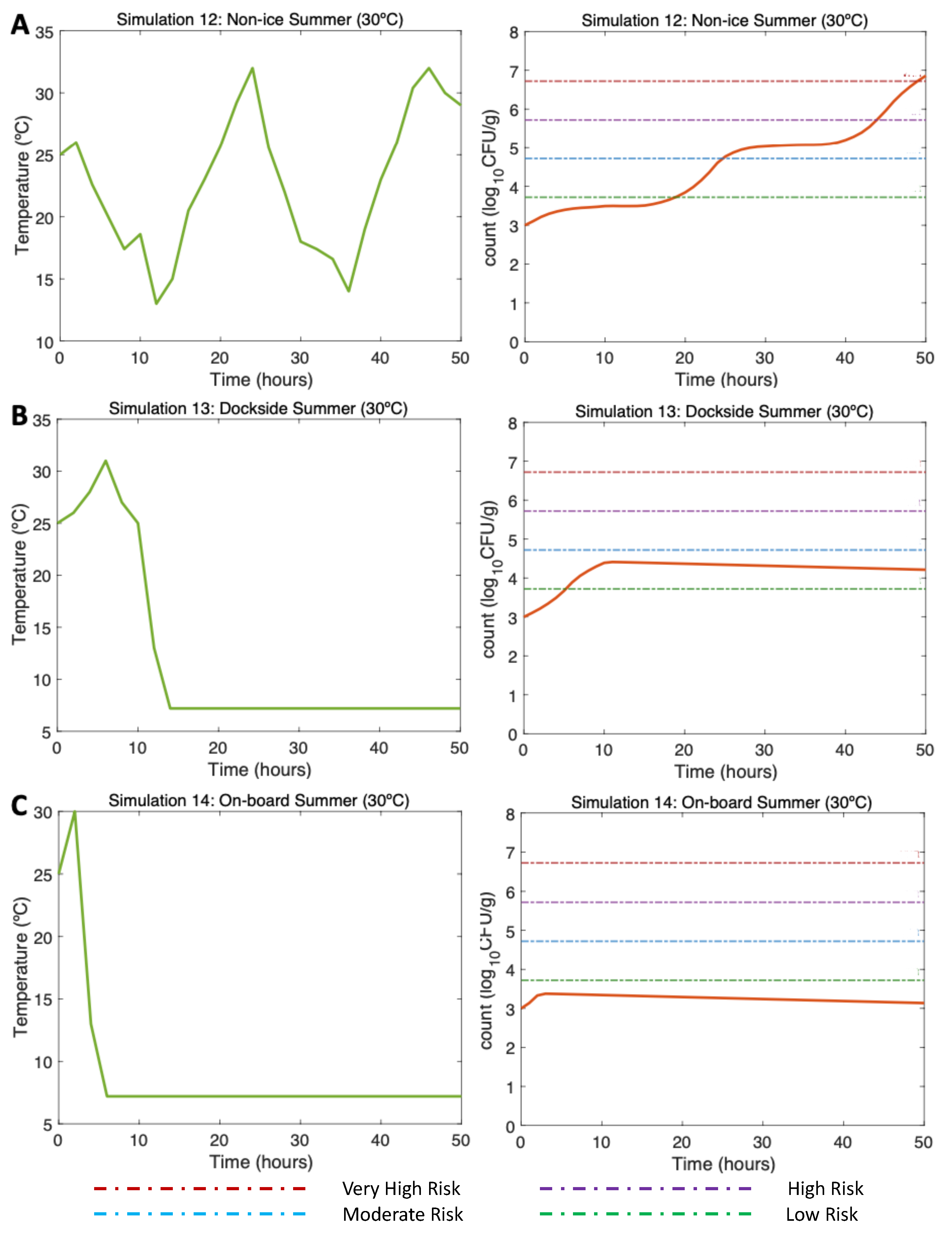

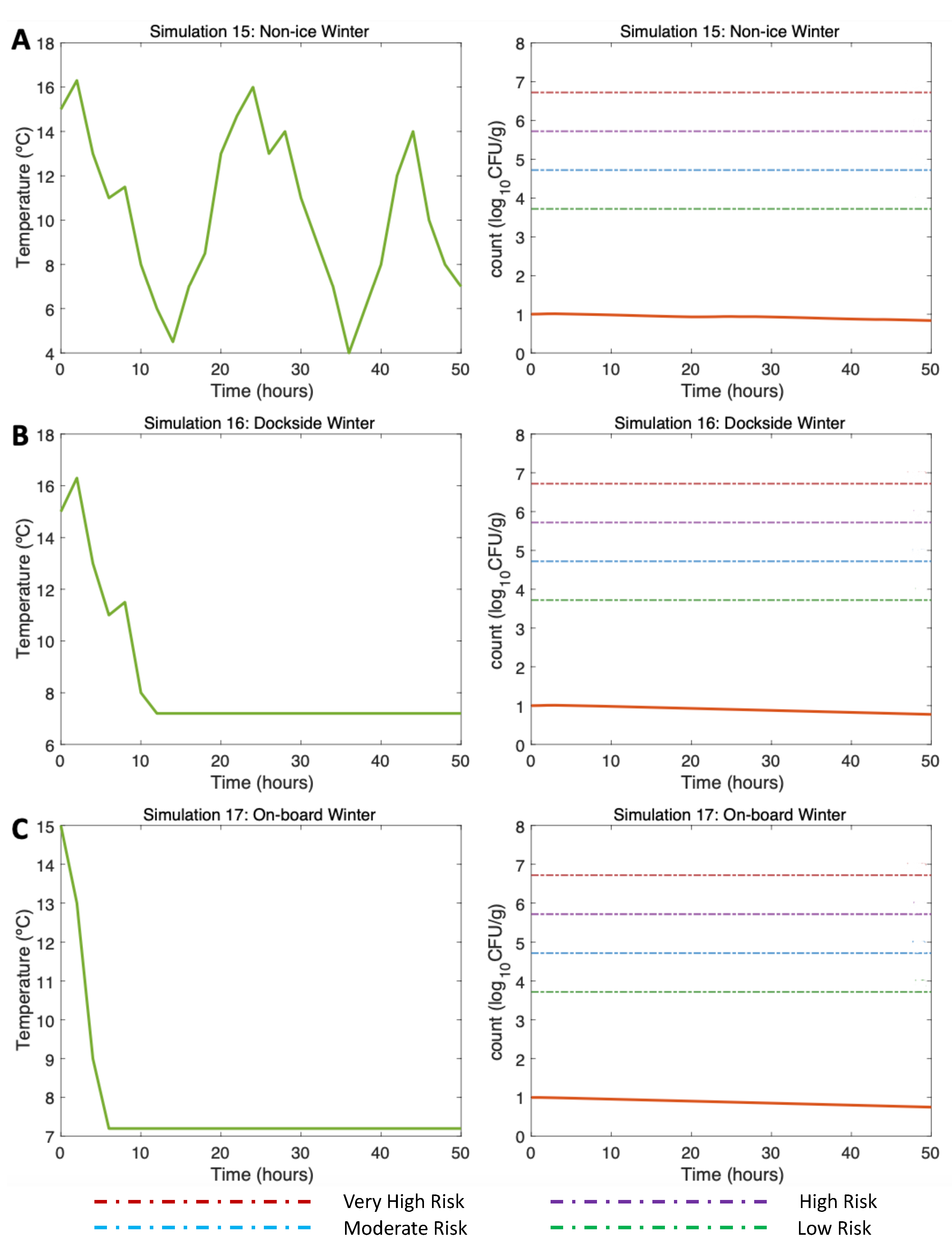

2.3.4. Modelling Scenarios

Different simulations were run representing both (i) realistic environmental (air) temperatures for regions with hot summers and mild winters as in south Europe [?] and south US [?], and (ii) realistic oyster processing temperature scenarios in terms of refrigeration by ice treatment from harvesting to consumption, in both summer and winter (simulations 9-17). For each season, simulated scenarios were differentiated by the ice treatment applied to oysters: non-iced (NI), dockside ice storage (DS), on-board ice storage (OB). In the NI scenario, there is not any type of pre-consumption treatment in terms of refrigeration. In the DS scenario, ice treatment started 10 hours after harvesting. In the OB scenario, ice treatment starts onboard right after harvesting.

Table 1.

Simulations for model verification and evaluation against experimental data of

Vp growth at constant temperatures from laboratory tests [

17].

Table 1.

Simulations for model verification and evaluation against experimental data of

Vp growth at constant temperatures from laboratory tests [

17].

| Simulation |

Scenario (Initial Conditions) |

Expected Results |

Figure |

| Simulation 1 |

T=18.4ºC, Vp=3.4

|

Logistic (extension) 3.4 to 5.5

|

3A |

| Simulation 2 |

T=20ºC, Vp=3.4

|

Logistic (extension) 3.4 to 5.5

|

3B |

| Simulation 3 |

T=25.7ºC, Vp=3.4

|

Logistic (extension) 3.4 to 7.5

|

3C |

| Simulation 4 |

T=30.4ºC,Vp=3.4

|

Logistic (extension) 3.4 to 6.75

|

3D |

| Simulation 5 |

T=3.6ºC, Vp=5.8

|

Linear 5.8 to 3.0

|

4A |

| Simulation 6 |

T=6.2ºC Vp=5.5

|

Linear 5.5 to 4.0

|

4B |

| Simulation 7 |

T=9.6ºCVp=5.1

|

Linear 5.1 to 3.0

|

4C |

| Simulation 8 |

T=12.6ºCVp=5.3

|

Linear 5.3 to 4.0

|

4D |

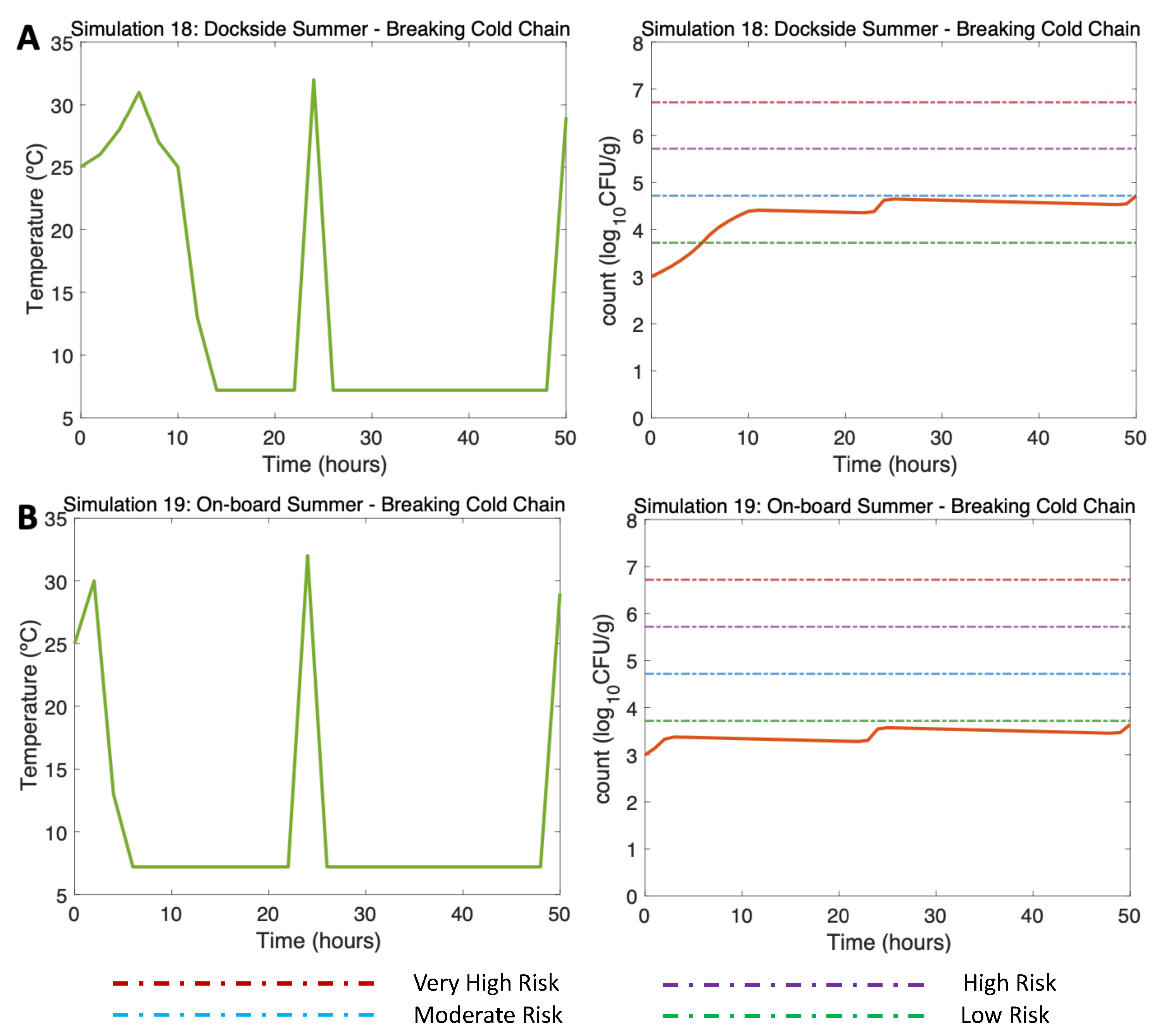

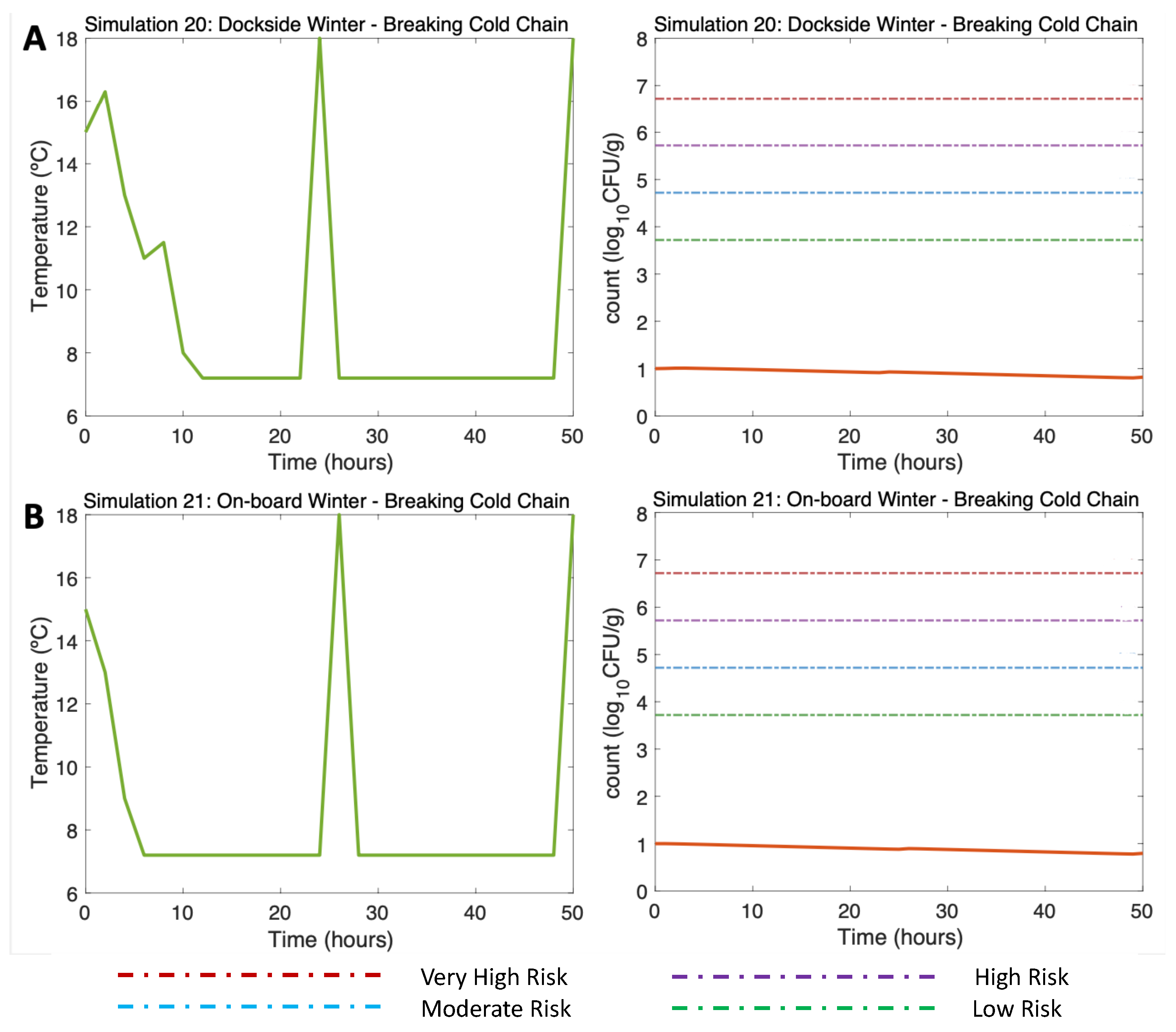

Other four realistic scenarios of interest were run in order to explore

Vp how

Vp growth would behave in an event of a potential break in the cold chain (simulations 18-21) referring to dockside and on-board situations in both winter and summer. Last simulation represent

Vp inactivation scenario in the long term. The characteristics of this set of modeling scenarios are summarized in

Table 2 and results showed in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

Table 2.

Realistic scenarios for exploring Vp dynamics in oysters under varying temperature in terms of water and air temperature, ice treatment and initial Vp number per oyster gram. Ice treatments are as follows: NI (non-iced), DS (ice treatment on dockside), OB (on-board ice treatment), Breaking cold chain (BCC). Water temperature (W), Air temperature (A).

Table 2.

Realistic scenarios for exploring Vp dynamics in oysters under varying temperature in terms of water and air temperature, ice treatment and initial Vp number per oyster gram. Ice treatments are as follows: NI (non-iced), DS (ice treatment on dockside), OB (on-board ice treatment), Breaking cold chain (BCC). Water temperature (W), Air temperature (A).

| Simulation |

Scenario (Initial Conditions) |

Figure |

| Simulation 9 |

NI, Summer, W= , A= , Vp=3

|

5A |

| Simulation 10 |

DS, Summer, W= , A= , Vp=3

|

5B |

| Simulation 11 |

OB, Summer, W= , A= , Vp=3

|

5C |

| Simulation 12 |

NI, Summer, W= , A= , Vp= 3

|

6A |

| Simulation 13 |

DS, Summer, W= , A= , Vp= 3

|

6B |

| Simulation 14 |

OB, Summer, W= , A= , Vp= 3

|

6C |

| Simulation 15 |

NI, Winter, W= , A= , Vp= 1 , |

7A |

| Simulation 16 |

DS, Winter, W= , A= , Vp= 1 , |

7B |

| Simulation 17 |

OB, Winter, W= , A= , Vp= 1 , |

7C |

| Simulation 18 |

DS, BCC Summer, W= , A= , Vp= 3

|

8A |

| Simulation 19 |

OB, BCC, Summer, W= , A= , Vp= 3

|

8B |

| Simulation 20 |

DS, BCC, Winter, W= , A= , Vp= 1

|

9A |

| Simulation 21 |

OB, BCC, Winter, W= , A= , Vp= 1

|

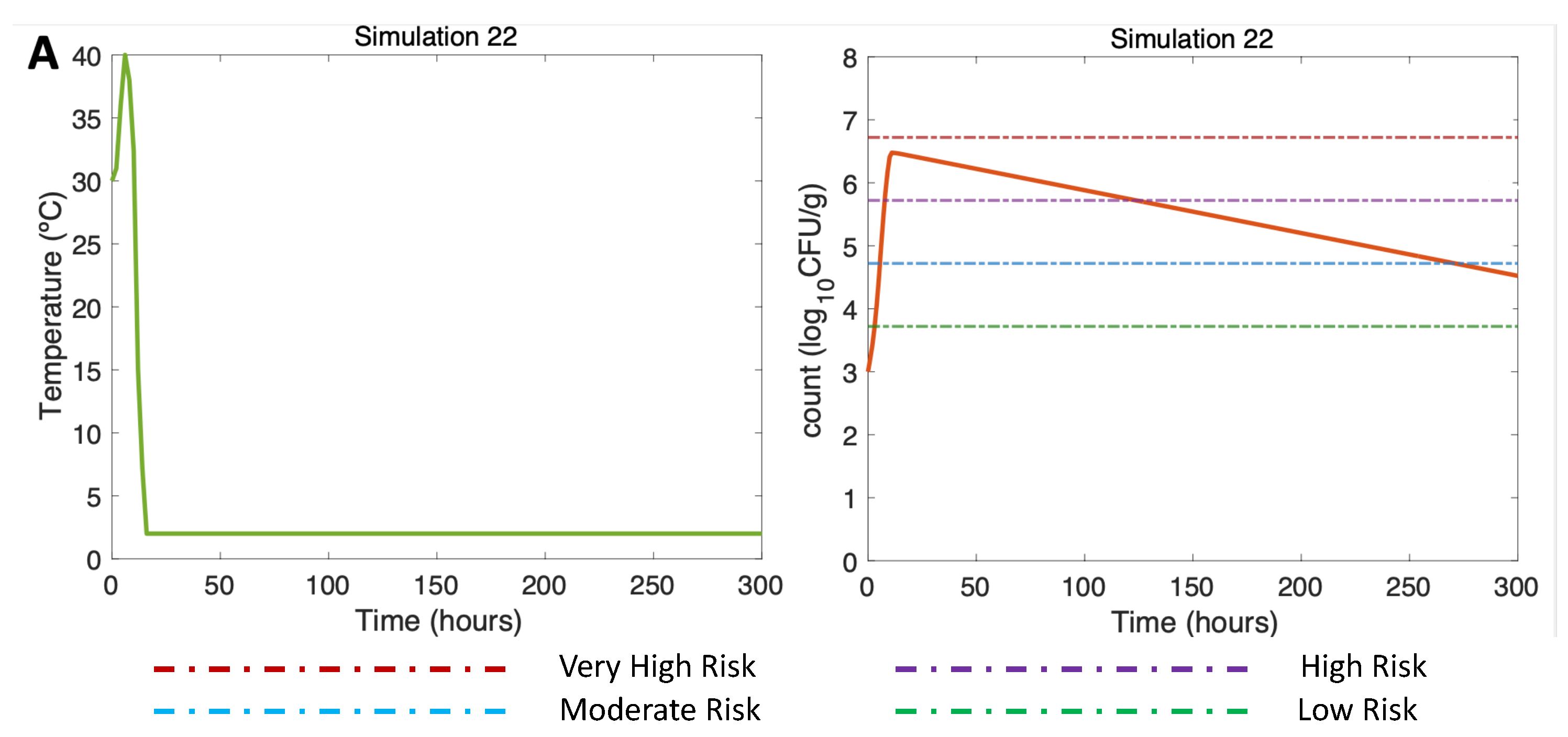

9B |

| Simulation 22 |

DS, Summer, W= , A= , Vp= 3

|

10A |

2.4. Risk of Illness

The model results are discussed in terms of the probability of illness. For this, risk of illness was estimated in

Table 3 by adapting previous dose-response model results [

18].

Table 3.

Probability and risk of gastroenteritis ((P(G) and R(G), respectively) and septicemia (P(S) and R(S), respectively) as a function of

Vp dose per oyster serving (12 oysters) and per oyster gram in a serving. Adapted and estimated from results of the Beta-Poisson Dose-Response model by [

18].

Table 3.

Probability and risk of gastroenteritis ((P(G) and R(G), respectively) and septicemia (P(S) and R(S), respectively) as a function of

Vp dose per oyster serving (12 oysters) and per oyster gram in a serving. Adapted and estimated from results of the Beta-Poisson Dose-Response model by [

18].

| CFU Per Serving |

Log CFU/g |

P (G) |

Risk (G) |

P (S) |

Risk (S) |

|

1.72 |

|

Extremely low |

|

Extremely low |

|

2.72 |

|

Very low |

|

Extremely low |

|

3.72 |

|

Low |

|

Extremely low |

|

4.72 |

|

Moderate |

|

Extremelylow |

|

5.72 |

|

High |

|

Verylow |

|

6.72 |

|

Very high |

|

Verylow |

|

7.72 |

|

Extremely high |

|

Verylow |

|

8.72 |

|

Extremely high |

|

Very low |

Note that U.S. Food and Drug Administration [

18], for example, predicts about 2800

Vp illnesses from oyster consumption each year. Of infected individuals, approximately 7 cases of gastroenteritis will progress to septicemia each year for the total population, of which 2 individuals would be from the healthy sub-population and 5 would be from the immunocompromised sub-population [

18].

2.5. Model Limitations

The ODE system here was solved using the RK4 method. RK4 methods are easy to implement, very stable, and self-starting; that is, unlike multi-step methods, there is no need to treat the first few steps taken by a single-step integration method as special cases. However, the primary disadvantages of RK4 methods are (i) the requirement of significantly more computation time than multi-step methods of comparable accuracy, and (ii) the fact that they do not easily yield good global estimates of the truncation error. However, for straightforward dynamical systems such as the one investigated by this model, the advantage of the relative simplicity and ease of use of RK4 methods far outweighs the disadvantage of their relatively high computational cost.

The growth and inactivation rate for the model was obtained by integrating the information obtained by regression models exploring the change in Vp concentrations with time at only eight constant temperatures. This is a simplification of reality and may result in a relative underestimation of Vp growth and consequently is an underestimation of the risk of getting gastroenteritis and septicemia.

Finally, when modeling realistic scenarios caution is required to interpret the results in quantitative terms; since the model is dealing with multiple dimensions, latent covariates, and data coming from laboratory experiments could result in some situations that are not entirely realistic.

4. Discussion

Varying temperatures critically shape

Vp proliferation dynamics of oysters [

18,

28]. However, empirically testing all possible varying temperature scenarios for a comprehensive study of their effects on

Vp proliferation is unachievable. Modeling

Vp growth under varying temperature mirroring ambient temperatures and the effect of ice treatments is crucial to both predict the magnitude of human illnesses and identify the temperature-related dynamics that are most important, particularly in the face of environmental change [

10,

29].

Our model generalizing from constant to time-varying temperatures was fed by growth and inactivation rate equations, both being temperature-dependent functions. These equations were obtained by means of analyzing the slope of regression models of the relationship between

Vp counts and time under different constant temperatures obtained in previous experiments [

17]. The slope for inactivation was identical to that obtained by [

17] as the same linear model was applied. The slope for the growth rate (maximum slope) obtained by the nonparametric LOESS regression model was very similar to that obtained by Baranyi models in [

17]. However, the LOESS curve adapted in a more flexible manner to the data and has the potential to extract more information from it than the Baranyi model. That is, the main advantage of using these types of models is the flexibility and the ease of interpretation of the smoothing function [

30]. Although further biological/ecological analysis of these non-parametric curves is required, non-parametric curves seem to provide valuable information to study the dynamics of bacterial growth in oysters in detail.

The model verification results conform to expectations of mathematical theory, behavior, and population dynamics. Moreover, the model evaluation against real experimental data shows a favorable match with particularly well-documented growth and inactivation dynamics from constant-temperature experiments [

17]. Once the model was verified and successfully evaluated, it can be considered for simulating different scenarios with the objective of improving the understanding of the

Vp-oyster system to support studies about the public health impact of pathogenic

Vp associated with raw oyster consumption. More broadly, this predictive initiative has the purpose to support identifying options for managing diseases caused by the consumption of any type of seafood. In addition, the model has also space to be adapted to and provide insights into other pathogen systems responding to varying temperatures e.g., [

31].

The model here is able to incorporate varying temperature conditions and day/night temperature oscillations to reproduce their effect on the temporal dynamics of

Vp. In this study, model initial conditions mirror realistic summer/winter

Vp concentrations in oysters [

13], with summer

Vp counts well above those in winter as high-temperatures favor

Vp proliferation, causing a higher number of bacteria at the time of collection. Model results are discussed here in terms of realistic air temperatures for zones with hot summers and mild winters as in south Europe [[

?] and south US [

?]. Increasing ambient temperature in summer favor

Vp growth in oysters from 3

up to 7.5

, resulting in a very high risk of gastroenteritis after consumption of a serving (12 oysters), particularly in hot summers reaching 40

C (Simulation 9). The model also reflects pathogen inactivation due to day/night oscillations, particularly, due to ice treatments. Ice treatment is much more effective in limiting the risk of illness when this is applied on board compared to dockside. On board, the gastroenteritis risk decreases to the low-risk zone (Simulation 11) corresponding to an extremely low risk for sepsis (

Table 3). Whilst, for dockside ice treatment, the risk of illness after a raw oyster serving consumption remains high for gastroenteritis and extremely high for septicemia. These results can be extrapolated to milder summers (30

C) in terms of dynamic patterns (Simulations 12-14) showing a rapid increase of

Vp followed by a maximum plateau. However, in this case, both on-board and dockside ice treatments limit the disease risk to the low-risk zone.

The model results are realistic; consuming raw oysters during hot summer months is inherently risky and requires onboard icing, while in mild summers dockside ice can be an acceptable control measure. The benefit of ice in hot summer scenarios is clear in our model results, but it should be emphasized that late cooling of oysters can be fatal and may not sufficiently inactivate the

Vp generated in the first few hours for guaranteeing a save consumption. These model results are consistent with oyster industry criteria [

18] and previous experimental studies [

32,

33].

For mild winter scenarios (Simulations 15-17), the model shows Vp counts starting from 1 and remaining consistently below the low-risk zone throughout the tested simulations. The effect of ice on inactivation is slight by hour 50. Here, the model detects tiny variations of each scenario; the final concentration of Vp is slightly higher in the non-ice scenario than that observed for the Dockside ice treatment scenario and relatively higher when compared to the on-board ice treatment scenario. The model also reproduces the effect of the cold chain breaking in summer (Simulations 18-19) showing an oscillating pattern with Vp growth and inactivation events. This effect is negligible in winter (Simulations 20-21).

A longer preservation time is essential to explore the real extent of cooling oysters down to minimize

Vp concentrations. For this, Simulation 22 was performed with initial conditions as in Simulation 10, but running the model for 300 hours (almost 13 days) instead of 50 hours (2 days). The model reproduces a cooling down on dockside decreasing oyster temperatures to 2

C. In this long-term simulation, the risk of gastroenteritis decreases from high risk to low risk by hour 300. Even if the prolonged ice treatment effect seems to work best for treating oysters for raw consumption, the ice treatment duration needs to be applied with caution. Very long ice treatments risk the marketability of harvested oysters; they may collapse and eventually open, influencing product placement and sales, and limiting their consumption, [

34]. Consequently, conclusions from this simulation result need to be balanced in terms of market quality. In winter, for example, prolonged and strong ice treatments may have little impact on inactivation compared to a non-ice scenario, while the performance of oysters can be jeopardizing sales.

This obviously cannot be extrapolated to higher temperature scenarios, where it is necessary to assess the most appropriate ice treatment timing (on-board or dockside) without posing a risk to human health. In this context, research on new treatments that minimize human health risks is essential. However, achieving this goal will not be an easy task as climatic anomalies are becoming more common, with long summer and winter seasons, thus increasing the seasonal risk of seafood illness. Under such circumstances, it is necessary to consider adjustments in industry practices and regulatory policy, especially for shellfish consumed raw, such as bivalve mollusks [

35]. Modeling approaches such as the one presented, verified, and evaluated here can be valuable tools with the necessary adjustments for simulating near-future scenarios under both varying ambient temperatures and the umbrella of climate change [

36,

37]. In addition, this modeling tool can support predictive studies under irregular and occasional temperature regimes, caused by weather events or thermoregulatory behaviors of organisms [

31]. Overall, this approach will help not only to improve our predictions of how organisms perform in varying temperature environments but also gain understanding of how temperature impacts organisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F., G.B., and TBH; methodology, I.F., G.B., and T.B.H.; software, I.F., G.B., and T.B.H.; validation, I.F., G.B., and T.B.H.; formal analysis, I.F., G.B., and T.B.H.; investigation, I.F., G.B., and T.B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, I.F., and G.B.; writing—review and editing, I.F., G.B., and T.B.H.; supervision, G.B., and T.B.H..