Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Celosia argentea: Taxonomy, Morphology, and Ethnobotanical Applications

3. Bioactive Compounds in C. argentea

4. Betalains in C. argentea: Biosynthesis Pathway, Biological Properties, and Applications

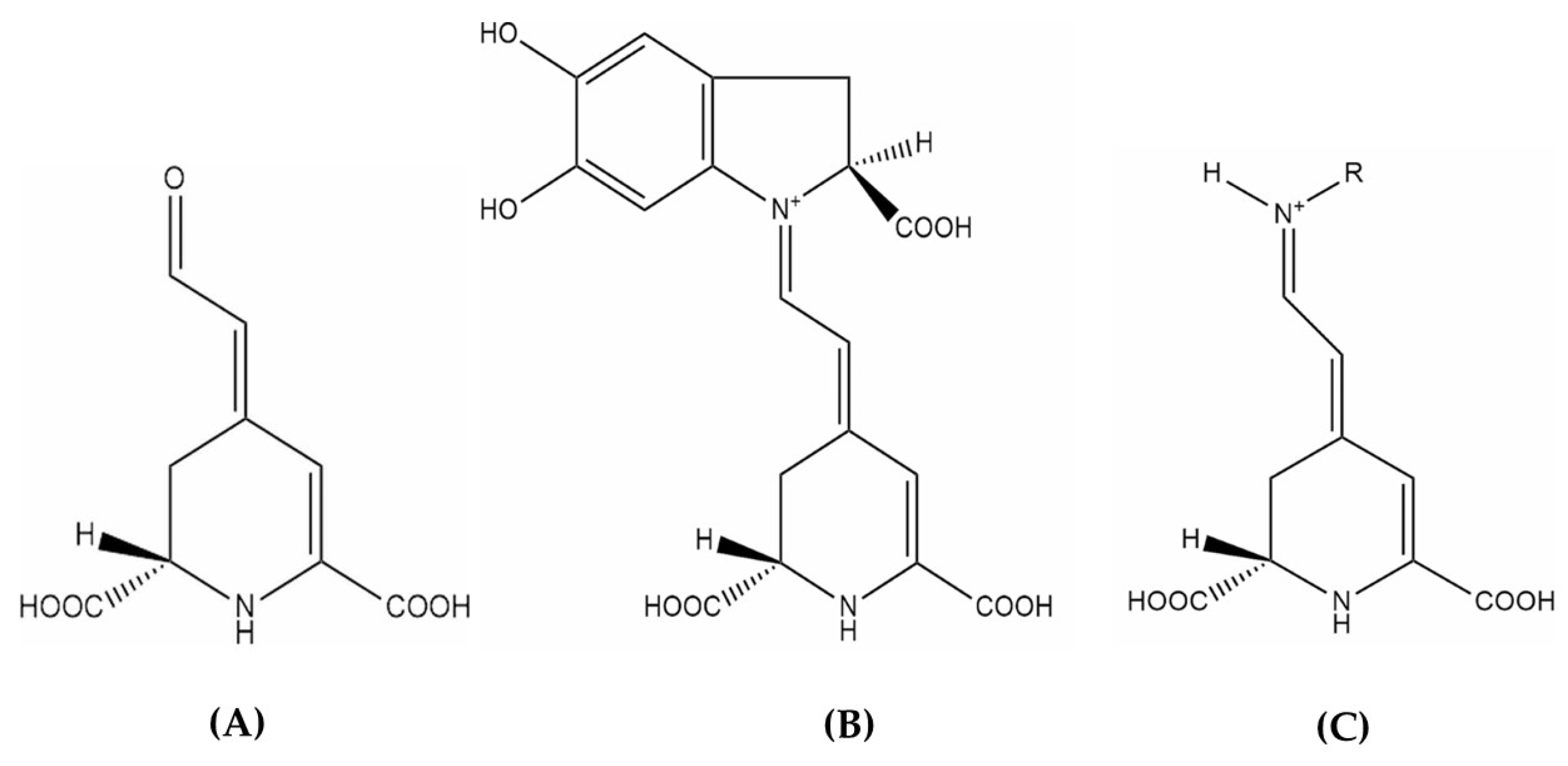

4.1. Biosynthesis Pathway of Betalains

4.2. Biological Properties of Betalains

4.3. Applications of Betalains

5. Production of Betalains from C. argentea

6. Perspectives

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schliemann, W.; Cai, Y.; Degenkolb, T.; Schmidt, J.; Corke, H. Betalains of Celosia argentea. Phytochem. 2001, 58, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surse, S.N.; Shrivastava, B.; Sharma, P.; Gide, P.S.; Attar, S. Celosia cristata: Potent pharmacotherapeutic herb—A review. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharm. Res. 2014, 3, 444–446. [Google Scholar]

- Nidavani, R.B.; Mahalakshmi, A.M.; Shalawadi, M. Towards a better understanding of an updated of ethnopharmacology of Celosia argentea L. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 5 (Suppl. 3), 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel, M.G. Betalains in some species of the Amaranthaceae family: A review. Antioxidants. 2018, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sun, M.; Schliemann, W.; Corke, H. Chemical stability and colorant properties of betaxanthin pigments from Celosia argentea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4429–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rub, R.A.; Pati, M.J.; Siddiqui, A.A.; Moghe, A.S.; Shaikh, N.N. Characterization of anticancer principles of Celosia argentea (Amaranthaceae). Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Xin, H.L.; Guo, M.L. Review on research of the phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Celosia argentea. Braz. J. Pharmacogn. 2016, 26, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.B.; Wang, Y.; Liang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Guo, M.L.; Zhang, J.J. Novel triterpenoid saponins from the seeds of Celosia argentea L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.; Sun, Z.L.; Guo, M.L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G. Two new compounds from Semen celosiae and their protective effects against CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 25, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rub, R.A.; Patil, M.J.; Shaikh, N.N.; Haikh, T.; Ahmed, J.; Siddiqui, A.A. Immunomodulatory profile of Celosia argentea–Activity of isolated compounds I and II. Int. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Res. 2015, 6, 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Ding, X.; Ouyang, M.A.; Wu, Z.J.; Xie, L.H. A new phenolic glycoside and cytotoxic constituents from Celosia argentea. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 12, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhujbal, S.S.; Chitlange, S.S.; Suralkar, A.A.; Shinde, D.B.; Patil, M.J. Anti-inflammatory activity of an isolated flavonoid fraction from Celosia argentea Linn. J. Med. Plant Res. 2008, 2, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H.; Morita, H.; Iwasaki, S.; Kobayashi, J. New antimitotic bicyclic peptides, celogentins D-H and J, from the seeds of Celosia argentea. Tetrahedron. 2003, 59, 5307–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, A.; Roon, T.; Klanrit, P.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, P.; Apiraksakorn, J.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P. Establishment of betalain-producing cell line and optimization of pigment production in cell suspension cultures of Celosia argentea var. plumosa. Plants. 2024, 13, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueangnak, K.; Kitwetcharoen, H.; Thanonkeo, S.; Klanrit, P.; Apiraksakorn, J.; Klanrit, P.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, P. Enhancing betalains production and antioxidant activity in Celosia argentea cell suspension cultures using biotic and abiotic elicitors. Sci. Rep-UK. 2025, 15, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odukoya, O.A.; Inya-Agha, S.I.; Segun, F.I.; Sodifiya, M.O.; Ilori, O.O. Antioxidant activities of selected Nigerian green leafy vegetables. Am. J. Food Technol. 2007, 2, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molehin, O.R.; Adefegha, S.A.; Oboh, G.; Saliu, J.A.; Athayde, M.L.; Boligon, A.A. Comparative study on the phenolic content, antioxidant properties and HPLC fingerprinting of three varieties of Celosia species. J. Food Biochem. 2014, 38, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiart, C.; Mogana, S.; Khalifah, S.; Mahan, M.; Ismail, S.; Buckle, M.; Narayana, A.K.; Sulaiman, M. Antimicrobial screening of plants used for traditional medicine in the state of Perak, Peninsular Malaysia. Fitoterapia. 2004, 75, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrichelvan, T.; Jegadeesan, M.; Devi, B.A.U. Anti-diabetic activity of alcoholic extract of Celosia argentea Linn. seeds in rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 25, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, Y.; Fujii, H.; Hase, K.; Ohnishi, Y.; Sakukawa, R.; Kadota, S.; Namba, T.; Saiki, I. Anti-metastatic and immunomodulating properties of the water extract from Celosia argentea seeds. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1998, 21, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hase, K.; Kadota, S.; Basnet, P.; Takahashi, T.; Namba, T. Hepatoprotective effects of traditional medicines. Isolation of the active constituent from seeds of Celosia argentea. Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showkat, S.; Rafiq, A.; Richa, R.; Sidique, Q.; Hussain, A.; Lohani, U.C.; Bhat, O.; Kumar, S. Stability enhancement of betalain pigment extracted from Celosia cristata L. flower through copigmentation and degradation kinetics during storage. Food Chem. X. 2025, 26, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palada, M.C.; Crossman, S.M.A. Evaluation of tropical leaf vegetables in the Virgin Islands. In Perspectives on New Crops and New Uses; Janick, J., Ed.; ASHS press: Alexandria, VA, 1999; pp. 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, M.; Grubben, G.J.H.; Denton, O.A. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. Vegetables. Kew Bull. 2004, 59, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.C.; Zhang, T.T.; Du, B.; Cheng, D.Y.; Li, Z.G. Chemical constituents of Celosia cristata L. Chinese Trad. Patent Med. 2014, 36, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.L.; Wei, J.H.; Sun, W.; Li, R.T.; Liu, S.B.; Dai, H.F. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants around Limu Mountains of Hainan Island, China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, M.L.; Li, Y.X. Two new hepaprotective saponins from Semen celosiae. Fitoterapia. 2010, 81, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, M. Triterpenoid saponins from the seeds of Celosia argentea and their anti-inflammatory and antitumor activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.B.; Wang, Y.; Liang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Guo, M.L.; Zhang, J.J. Novel triterpenoid saponins from the seeds of Celosia argentea L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; Yan, H.X.; Wang, Z.F.; Fan, M.X.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, X.T.; Xiong, C.Q.; Zhang, J.; Ma, B.P.; Guo, H.Z. New oleanane-type triterpenoid saponins isolated from the seeds of Celosia argentea. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 16, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Shimbo, K.; Shigemori, H.; Kobayashi, J. Antimitotic activity of moroidin, a bicyclic peptide from the seeds of Celosia argentea. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, J.; Suzuki, H.; Shimbo, K.; Takeya, K.; Morita, H. Celogentins A–C, new antimitotic bicyclic peptides from the seeds of Celosia argentea. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 6626–6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Morita, H.; Iwasaki, S.; Kobayashi, J. New antimitotic bicyclic peptides, celogentins D–H, and J, from the seeds of Celosia argentea. Tetrahedron. 2003, 59, 5307–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Morita, H.; Shiro, M.; Kobayashi, J.I. Celogentin K, a new cyclic peptide from the seeds of Celosia argentea and X-ray structure of moroidin. Tetrahedron. 2004, 60, 2489–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Suzuki, H.; Kobayashi, J. Celogenamide A, a new cyclic peptide from the seeds of Celosia argentea. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 67, 1628–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.H.; Cui, X.; Zhou, P.; Li, S.L. A comparative study of fatty acids and inorganic elements in Semen celosiae and cockscomb. J. Chinese Med. Mat. 1995, 18, 466–467. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.Q. The chemical constituents of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. var. acute (Thunb.) and Celosia argentea L. seeds grown in Fujian province. Chinese Acad. Med. Magazing Organisms 2002, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.Z.; Meng, X.Y.; Li, S.S.; Wu, L.J. Study on the chemical constituents of Semen celosiae. Chinese Trad. Herbal Drugs. 1992, 23, 344–345. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Q.; Guo, M.; Zhang, G. Study of chemical constituents of Semen celosiae. Pharm. Care Res. 2006, 6, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- Markandeya, A.G.; Firke, N.P.; Pingale, S.S.; Salunke-Gawali, S. Quantitative elemental analysis of Celosia argentea leaves by ICP-OES technique using various digestion methods. Int. J. Chem. Anal. Sci. 2013, 4, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorat, B.R. Review on Celosia argentea L. plant. Res. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 2018, 10, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, B.J.; Jyothi Sravani, M.; Hari Chandana, J.; Sumana, T.; Thyagaraju, K. Phytochemical and phytotherapeutic activities of Celosia argentea: a review. World J. Pharm. Pharmaceu. Sci. 2019, 8, 488–505. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.I.; Harsha, P.S.C.S.; Chauhan, A.S.; Vijayendra, S.V.N.; Asha, M.R.; Giridhar, P. Betalains rich Rivina humilis L. berry extract as natural colorant in product (fruit spread and RTS beverage) development. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1808–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polturak, G.; Aharoni, A. “La Vie en Rose”: biosynthesis, sources, and applications of betalain pigments. Mol Plant 2018, 11, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreón-Hidalgo, J.P.; Franco-Vásquez, D.C.; Gómez-Linton, D.R.; Pérez-Flores, L.J. Betalain plant sources, biosynthesis, extraction, stability enhancement methods, bioactivity, and applications. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.C. Betalains: properties, sources, applications, and stability—A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 2365–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Herrero, F.; García-Carmona, F. Biosynthesis of betalains: yellow and violet plant pigments. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimen, I.B.; Najar, T.; Abderrabba, M. Chemical and antioxidant properties of betalains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Production of betalains in plant cell and organ cultures: A review. Plant Cell Tiss Org 2024, 158, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, D.; Vogt, T.; Schliemann, W. Recent advances in betalain research. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I. Stabilization of betalains: A review. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Hua, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Hu, G.; Zhao, J.; Qin, Y. Transcriptomics-based identification and characterization of glucosyltransferases involved in betalain biosynthesis in Hylocereus megalanthus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 152, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.C.; Chiu, Y.C.; Tsao, N.W.; Chou, Y.L.; Tan, C.M.; Chiang, Y.H.; Liao, P.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Hsieh, L.C.; Wang, S.Y.; Yang, J.Y. Elucidation of the core betalain biosynthesis pathway in Amaranthus tricolor. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2021, 11, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzin, V.; Galili, G. The biosynthetic pathways for shikimate and aromatic amino acids in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis Book. 2010, 8, e0132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotewold, E. The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yu, Z.H.; Xiao, X.G. Cytosolic and nuclear colocalization of betalain biosynthetic enzymes in tobacco suggests that betalains are synthesized in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus of betalainic plant cells. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunnadeniya, R.; Bean, A.; Brwon, M.; Akhavan, N.; Hatlestad, G.; Gonzalez, A.; Symonds, V.V.; Lloyd, A. Tyrosine hydroxylation in betalain pigment biosynthesis is performed by cytochrome P450 enzymes in beets (Beta vulgaris). PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0149417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, N.; Aabe, Y.; Goda, Y.; Adachi, T.; Kasahara, K.; Ozeki, Y. Detection of DOPA 4,5-dioxygenase (DOD) activity using recombinant protein prepared from Escherichia coli cells harboring cDNA encoding DOD from Mirabilis jalapa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Dreiding, A.S. Biosynthesis of betalains. On the cleavage of aromatic ring during enzymatic transformation of DOPA into betalamic acid. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1972, 55, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N.; Adachi, T.; Koda, T.; Ozeki, Y. Detection of UDP glucose:cyclo-DOPA 5-O-glucosyltransferase activity in four o’clocks (Mirabilis jalapa L). FEBS Lett. 2004, 568, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N.; Wada, K.; Koda, T.; Kasahara, K.; Adachi, T.; Ozeki, Y. Isolation and characterization of cDNAs encoding an enzyme with glucosyltransferase activity for cyclo-DOPA from four o’clocks and feather cockscombs. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005, 46, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj Slimen, I.; Najar, T.; Abderrabba, M. Chemical and antioxidant properties of betalains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esatbeyoglu, T.; Wagner, A.E.; Schini-Kerth, V.B.; Rimbach, G. Betanin– a food colorant with biological activity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira Teixeira da Silva, D.; dos Santos Baião, D.; de Oliveira Silva, F.; Alves, G.; Perrone, D.; Mere Del Aguila, E.; Flosi Paschoalin, V.M. Betanin, a natural food additive: stability, bioavailability, antioxidant and preservative ability assessments. Molecules. 2019, 24, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, L.C.P.; Lopes, N.B.; Augusto, F.A.; Pioli, R.M.; Machado, C.O.; Freitas-Dörr, B.C.; Suffredini, H.B.; Bastos, E.L. Phenolic betalain as antioxidants: Meta means more. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 92, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadam, M.; Venkidasamy, B.; Subramanian, U.; Samynathan, R.; Ali Shariati, M.; Rebezov, M.; Girish, S.; Thangavel, S.; Dhanapal, A.R.; Fedoseeva, N.; et al. Bioactive compounds in oxidative stress-mediated diseases: targeting the NRF2/ARE signaling pathway and epigenetic regulation. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanzio, A.; Frazzitta, A.; Busa, R.; Tesoriere, L.; Livrea, M.A.; Allegra, M. Indicaxanthin from Opuntia ficus-indica (L. Mill) inhibits oxidized LDL-mediated human endothelial cell dysfunction through inhibition of NF-κB activation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longe. 2019, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, H.; Nayeri, Z.; Minuchehr, Z.; Sabouni, F.; Mohammadi, M. Betanin purification from red beetroots and evaluation of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity on LPS-activated microglial cells. PLoS One. 2020, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunan, D.; Yu, M.; Guan, H.; Zhou, Y. Neuroprotective effect of betalain against AlCl3-induced Alzheimer’s disease in Sprague Dawley rats via putative modulation of oxidative stress and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-ΚB) signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmaco. 2021, 137, 111369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fernando, G.S.N.; Sergeeva, N.N.; Vagkidis, N.; Chechik, V.; Do, T.; Marshall, L.J.; Boesch, C. Uptake and immunomodulatory properties of betanin, vulgaxanthin I and indicaxanthin towards Caco-2 intestinal cells. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, G.S.N.; Sergeeva, N.N.; Vagkidis, N.; Chechik, V.; Marshall, L.J.; Boesch, C. Differential effects of betacyanin and betaxanthin pigments on oxidative stress and inflammatory response in murine macrophages. Mol. Nutri. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2200583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ley, C.M.; Osorio-Revilla, G.; Hernández-Martínez, D.M.; Ramos-Monroy, O.A.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T. Anti-inflammatory activity of betalains: A comprehensive review. Human Nutri. Metab. 2021, 25, 200126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadanović-Brunet, J.M.; Savatović, S.S.; Ćetković, G.S.; Vulić, J.J.; Djilas, S.M.; Markov, S.L.; Cvetković, D.D. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of beet root pomace extracts. Czech J. Food Sci. 2011, 29, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Y.Y.; Dykes, G.; Lee, S.M.; Choo, W.S. Comparative study of betacyanin profile and antimicrobial activity of red pitahaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) and red spinach (Amaranthus dubius). Plant Foods Human Nutri. 2017, 72, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melgar, B.; Dias, M.I.; Ciric, A.; Sokovic, M.; Garcia-Castello, E.M.; Rodriguez-Lopez, A.D.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I. By-product recovery of Opuntia spp. peels: Betalainic and phenolic profiles and bioactive properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 107, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Bartosz, G. Biological properties and applications of betalains. Molecules. 2021, 26, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandate-Flores, L.; Romero-Esquivel, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.; Rostro-Alanis, M.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Castillo-Zacarías, C.; Ontiveros, P.R.; Celaya, M.F.M.; Chen, W.-N.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; et al. Functional attributes and anticancer potentialities of Chico (Pachycereus Weberi) and Jiotilla (Escontria Chiotilla) fruits extract. Plants. 2020, 9, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henarejos-Escudero, P.; Hernández-García, S.; Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Antitumoral drug potential of tryptophan-betaxanthin and related plant betalains in the Caenorhabditis elegans tumoral model. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska-Przyjemska, M.; Olejnik, A.; Dobrowolska-Zachwieja, A.; Łuczak, M.; Baer-Dubowska, W. DNA damage and apoptosis in blood neutrophils of inflammatory bowel disease patients and in Caco-2 cells in vitro exposed to betanin. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2016, 70, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, L.; Vigneron, P.; Rotellini, L.; Cazzola, H.; Merlier, F.; Prost, E.; Ralanairina, R.; Gadonna, J.P.; Rossi, C.; Vayssade, M. Betanin-enriched red beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) extract induces apoptosis and autophagic cell death in MCF-7 cells. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 29, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar]

- Allegra, M.; De Cicco, P.; Ercolano, G.; Attanzio, A.; Busá, R.; Cirino, G.; Tesoriere, L.; Livrea, M.A.; Ianaro, A. Indicaxanthin from Opuntia ficus-indica (L. Mill) impairs melanoma cell proliferation, invasiveness, and tumor progression. Phytomedicine. 2018, 50, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Guo, T.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Wang, X. Potential chemotherapeutic effect of betalain against human non-small cell lung cancer through PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Yu, K.; Chu, X.; Yang, L. Betanin alleviates inflammation and ameliorates apoptosis on human oral squamous cancer cells SCC131 and SCC4 through the NF-κB/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiailanis, A.D.; Chatzigiannis, C.M.; Papaemmanouil, C.D.; Chatziathanasiadou, M.V.; Chaloulos, P.; Riba, I.; Mullard, G.; Wiczkowski, W.; Koutinas, A.; Mandala, J.; Tzakos, A.G. Exploration of betalains and determination of the antioxidant and cytotoxicity profile of orange and purple Opuntia spp. cultivars in Greece. Plant Foods Human Nutri. 2022, 77, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, P.P.S.; Silva-e-Silva, A.C.A.G.d.; Antonio, A.d.S.; Pereira, H.M.G.; Veiga-Junior, V.F.d.; Felzenszwalb, I.; Araujo-Lima, C.F.; Teodoro, A.J. Antioxidant capacity, antitumor activity and metabolomic profile of a beetroot peel flour. Metabolites. 2023, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, E.; Mazloum-Ravasan, S.; Yu, J.S.; Ha, J.W.; Hamishehkar, H.; Kim, K.H. Therapeutic application of betalains: A review. Plants. 2020, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, M.A.; Naselli, F.; Cruciata, I.; Volpes, S.; Schimmenti, C.; Serio, G.; Mauro, M.; Librizzi, M.; Luparello, C.; Chiarelli, R.; et al. Indicaxanthin induces autophagy in intestinal epithelial cancer cells by epigenetic mechanisms involving DNA methylation. Nutrients. 2023, 15, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alian, D.M.E.; Helmy, M.W.; Haroun, M.; Moussa, N. Modulation of autophagy and apoptosis can contribute to the anticancer effect of Abemaciclib/celecoxib combination in colon cancer cells. Med. Oncol. 2024, 41, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazersaheb, S.; Jafari, S.; Aytemir, M.D.; Ahmadian, E.; Ardalan, M.; Zor, M.; Nasibova, A.; Monirifar, A.; Aghdasi, S. The synergistic effects of betanin and radiotherapy in a prostate cancer cell line: An in vitro study. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 9307–9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Tan, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Tan, D. Betanin reduces the accumulation and cross-links of collagen in high-fructose-fed rat heart through inhibiting non-enzymatic glycation. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2015, 227, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I. Plant betalains: Safety, antioxidant activity, clinical efficacy, and bioavailability. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety. 2016, 15, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Becerra-Martínez, E.; Pacheco-Hernández, Y.; Landeta-Cortés, G.; Villa-Ruano, N. Synergistic hypolipidemic and hypoglycemic effects of mixtures of Lactobacillus nagelii/betanin in a mouse model. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 19, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Maqueo, A.; García-Cayuela, T.; Fernández-López, R.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cano, M.P. Inhibitory potential of prickly pears and their isolated bioactives against digestive enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes and inflammatory response. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 6380–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, P.; Mesbah-Namin, S.A.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Abedimanesh, S.; Separham, A.; Jafarabadi, M.A. Effects of betalains on atherogenic risk factors in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Food Func. 2019, 10, 8286–8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ydjedd, S.; Chaalal, M.; Bahri, S.; Mokadem, S.; Radji, H. Antioxidant and α-amylase inhibition activities of prickly pears (Opuntia ficus indica L.) betalains extracts and application in yogurt as natural colorants. J. Agro. Proc. Technol. 2021, 27, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, D.V.T.; Pereira, A.D.; Boaventura, G.T.; Ribeiro, R.S.d.A.; Verícimo, M.A.; Carvalho-Pinto, C.E.d.; Baião, D.d.S.; Del Aguila, E.M.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Short-term betanin intake reduces oxidative stress in Wistar Rats. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, P.; Henarejos-Escudero, P.; Hernández-García, S.; Sánchez-Ferrer, Á.; Gandía-Herrero, F. In vitro, in vivo, and in silico evidence for the use of plant pigments betalains as potential nutraceuticals against Alzheimer’s disease. Food Front. 2024, 5, 2137–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedimanesh, N.; Asghari, S.; Mohammadnejad, K.; Daneshvar, Z.; Rahmani, S.; Shokoohi, S.; Motlagh, B.; et al. The anti-diabetic effects of betanin in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats through modulating AMPK/SIRT1/NF-κB signaling pathway. Nutri. Meta. 2021, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Radioprotective activity of betalains from red beets in mice exposed to gamma irradiation. Eur. J. Pharm. 2009, 615, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Szaefer, H.; Ignatowicz, E.; Adamska, T.; Baer-Dubowska, W. Beetroot juice protects against N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced liver injury in rats. Food Chem. Toxic. 2012, 50, 2027–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.K.; Ahmed, S.A.; El-Boghdady, N.A.; Metwally, N.S.; Nasr, N.N. Impact of betanin against paracetamol and diclofenac induced hepato-renal damage in rats. Biomarkers. 2020, 25, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Miao, L.; Guo, Y.; Tian, H.; Dos Santos, J.M. Preclinical evaluation of safety, pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and mechanism of radioprotective agent HL-003. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6683836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, P.M.; Guerrero-Rubio, A.; Henarejos-Escudero, P.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Health-promoting potential of betalains in vivo and their relevance as functional ingredients: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, G.Y.; Moussa, M.E.M.; Sheashea, E.R. Characterization of red pigments extracted from red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) and its potential uses as antioxidant and natural food colorants. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 91, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Manoj, P.; Shetty, N.P.; Prakash, M.; Giridhar, P. Characterization of major betalain pigments-gomphrenin, betanin and isobetanin from Basella rubra L. fruit and evaluation of efficacy as a natural colourant in product (ice cream) development. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 4994–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roriz, C.L.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Morales, P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Gomphrena globosa L. as a novel source of food-grade betacyanins: Incorporation in ice-cream and comparison with beet-root extracts and commercial betalains. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 92, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Harsha, P.S.C.S.; Chauhan, A.S.; Vijayendra, S.V.N.; Asha, M.R.; Giridhar, P. Betalains rich Rivina humilis L. berry extract as natural colorant in product (fruit spread and RTS beverage) development. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1808–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneşer, O. Pigment and color stability of beetroot betalains in cow milk during thermal treatment. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengatharan, A.; Dykes, G.A.; Choo, W.S. Stability of betacyanin from red pitahaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) and its potential application as a natural colourant in milk. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengatharan, A.; Dykes, G.A.; Choo, W.S. The effect of pH treatment and refrigerated storage on natural colourant preparations (betacyanins) from red pitahaya and their potential application in yoghurt. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 80, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coria-Cayupán, Y.; Nazareno, M.A. Cactus betalains can be used as antioxidant colorants protecting food constituents from oxidative damage. Acta Hort. 2015, 1067, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.A.; María, T.C.V.; Barragán-Huerta, B.E. Betaxanthins and antioxidant capacity in Stenocereus pruinosus: Stability and use in food. Food Res. Int. 2017, 91, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal-Alcazar, M.C.; Bautista-Palestina, F.; Rocha-Pizana, M.R.; Mojica, L.; Hernández-Álvarez, A.J.; Luna-Vital, D.A. Extraction, stabilization, and health application of betalains: An update. Food Chem. 2025, 481, 144011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amnah, M.A. Nutritional, sensory and biological study of biscuits fortified with red beetroots. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Kushwaha, R.; Goyal, A.; Tanwar, B.; Kaur, J. Process optimization for the preparation of antioxidant-rich ginger candy using beetroot pomace extract. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Singh Chauhan, A.; Giridhar, P. Nanoliposomal encapsulation mediated enhancement of betalain stability: Characterisation, storage stability and antioxidant activity of Basella rubra L. fruits for its applications in vegan gummy candies. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iahtisham-Ul-Haq; Butt, M.S.; Randhawa, M.A.; Shahid, M. Nephroprotective effects of red beetroot-based beverages against gentamicin-induced renal stress. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, 12873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Cai, Y.Z.; Corke, H. Evaluation of Asian salted noodles in the presence of Amaranthus betacyanin pigments. Food Chem. 2010, 118, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzer, E.; Ozogul, F.; Ozogul, Y. Impact of icing with potato, sweet potato, sugar beet, and red beet peel extract on the sensory, chemical, and microbiological changes of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fillets stored at (3 ± 1 °C). Aquacult. Int. 2020, 28, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamróz, E.; Kulawik, P.; Guzik, P.; Duda, I. The verification of intelligent properties of furcellaran films with plant extracts on the stored fresh Atlantic mackerel during storage at 2 °C. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 97, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Development of active and intelligent packaging by incorporating betalains from red pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) peel into starch/polyvinyl alcohol films. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020, 100, 105410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Hu, H.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J. Development of antioxidant, antimicrobial and ammonia-sensitive films based on quaternary ammonium chitosan, polyvinyl alcohol and betalains-rich cactus pears (Opuntia ficus-indica) extract. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020, 106, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yao, X.; Qin, Y.; Yong, H.; Liu, J. Development of multifunctional food packaging by incorporating betalains from vegetable amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor L.) into quaternary ammonium chitosan/fish gelatin blend films. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules. 2020, 159, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guesmi, A.; Ben Hamadi, N.; Ladhari, N.; Sakli, F. Dyeing properties and colour fastness of wool dyed with indicaxanthin natural dye. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 37, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, V.; Blaga, A.C.; Caşcaval, D.; Popescu, A. Beta vulgaris L.—A source with a great potential in the extraction of natural dyes intended for the sustainable dyeing of wool. Plants. 2023, 12, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zawahry, M.M.; Kamel, M.M.; Hassabo, A.G. Development of bio-active cotton fabric coated with betalain extract as encapsulating agent for active packaging textiles. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.M.; Gouda, M.; Abou Taleb, M.F.; Abdelaziz, M.A.; Abd El-Lateef, H.M. Development of betalain-finished plasma-treated nonwoven cotton textiles from beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) and recycled fabrics for identification of ammonia. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azwanida, N.N.; Normasarah, A.A. Utilization and evaluation of betalain pigment from red dragon fruit (Hylocereus Polyrhizus) as a natural colorant for lipstick. J. Teknol. 2014, 69, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoles, G.E.; Pattacini, S.H.; Covas, G.F. Separation of the pigment of an amaranth. Molecules. 2000, 5, 566–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lanier, S.M.; Downing, J.A.; Avent, J.L.; Lumc, J.; McHalea, J.L. Betalain pigments for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2008, 195, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, G.; Yumb, J.H.; Sinopoli, A.; Di Marco, G.; Grätzel, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Anthocyanins and betalains as light-harvesting pigments for dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy. 2012, 86, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, F.J.; Malamen, D.J.; McHale, J.L.; Marchioro, A.; Moser, J.E. Two-electron photo-oxidation of betanin on titanium dioxide and potential for improved dye-sensitized solar energy conversion. Physic. Chem. Interfaces Nanomaterials XIII. 2014, 9165, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Knorr, F.J.; McHale, J.L.; Clark, A.E.; Marchioro, A.; Moser, J.E. Dynamics of interfacial electron transfer from betanin to nanocrystalline TiO2: the pursuit of two-electron injection. J. Physic. Chem. 2015, 119, 1903019041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; Escribano, J.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Light emission in betalains: From fluorescent flowers to biotechnological applications. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; Martínez-Zapata, J.; Henarejos-Escudero, P.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Reversible bleaching of betalains induced by metals and application to the fluorescent determination of anthrax biomarker. Dyes Pigment. 2020, 180, 108493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, M.M.; Bani-Domi, A. Sustainable betalain pigments as eco-friendly film coating over aluminium surface. J. Materials Sci. 2021, 56, 13556–13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D.L.A.; Paun, C.; Pavliuk, M.V.; Fernandes, A.B.; Bastos, E.L.; Sá, J. Green microfluidic synthesis of monodisperse silver nanoparticles via genetic algorithm optimization. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 95693–95697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warhade, M.I.; Badere, R.S. Isolation of callus lines of Celosia cristata L. with variation in betalain content. J Indian Bot Soc 2015, 94, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Warhade, M.I.; Badere, R.S. Fusarium oxysporum cell elicitor enhances betalain content in the cell suspension culture of Celosia cristata. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2018, 24, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavokovic, D.; Krsnik-Rasol, M. Complex biochemistry and biotechnological production of betalains. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2011, 49, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

| Bioactive compound | Chemical | Analytical technique | Plant part | Reference |

| Saponins | Celosin A, Celosin B, Celosin C, Celosin D, Celosin E, Celosin F, Celosin G, Celosin I, Celosin II, Celosin H, Celosin I, Celosin J, Cristatain | NMR, HPLC-ELSD | Seed | [9,27,28,29,30] |

| Polyphenols | Lutin, Epigallocatechin, Gallic acid, Caffeic acid, Rosmarinic acid, Quercetin, 4-O-β-d-apifuranosyl-(1→2)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-2-hydroxy-6-methoxyacetophenone | HPLC | Leaf | [11,17] |

| Peptides | Moroidin, Celogentins A, Celogentins B, Celogentins C, Celogentins D, Celogentins E, Celogentins F, Celogentins G, Celogentins H, Celogentins J, Celogentins K, Celogenamide A | NMR, MS/MS, CD spectra | Seed | [31,32,33,34,35] |

| Amino acids | Glycine, Alanine, Arginine, Lysine, Glutamic acid, Valine, Methionine, Isoleucine, Phenylalanine, Serine, Tyrosine, Proline, Leucine, Histidine, Aspartic acid, Cysteine, Cytine, Threonine, Ornithine | Amino acid analyzer | Seed, Leaf | [36,37] |

| Fatty acids | Arachic acid, Arachidonic acid, Linolenic acid, Hexadecanoic acid, Palmitoleic acid, Octadecanoic acid, Octadecanoic monoenoic acid, Oleinic acid, Linoleic acid | GC | Seed | [36,37] |

| Betalains | Betaxanthins (Indicaxanthin, Dopaxanthin), Betacyanins (Betanin, Gomphrenin, Amaranthine, and Bougainvillein) | Spectrophotometry | Leaf, Inflorescence | [1,14,15] |

| Minerals | K, Ca, Mg, Na, Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn, S, Si, Ti, Cd, Hg, Cr, Mo, Pb | AA | Seed, Leaf | [36,37] |

| Others | Β-Sitosterol, Stigmasterol, β-Carotene, Ascorbic acid | - | Seed, Leaf | [38,39] |

| Biological activity | Mode of action | Reference |

| Antioxidant |

|

[45,63,64,65,66] |

| Anti-inflammatory |

|

[45,67,68,69,70,71,72] |

| Antimicrobial | Betalains exert antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria by targeting microbial cell membranes, similar to phenolic compounds. They alter membrane function and structure while increasing membrane permeability, ultimately leading to microbial cell death | [45,73,74,75,76] |

| Anticancer |

|

[77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] |

| Antidiabetic and antilipidemic |

|

[86,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Hepatoprotective, neuroprotective, and other effects |

|

[99,100,101,102,103] |

| Industry | Product | Plant source | Reference |

| Foods and beverages | Jelly, ice cream, and ice sherbets | B. vulgaris | [104,105,106] |

| Banana juice, fruit spread | Rivina humilis | [107] | |

| Dairy (cow milk) | B. vulgaris, Hylocereus polyrhizus | [108,109] | |

| Yogurt | H. polyrhizus | [110] | |

| Yogurt and cream | Opuntia ficus-indica, O. megacantha | [111] | |

| Jelly gummy and drink | Salicornia fruticosa | [112] | |

| Juice | B. vulgaris | [113] | |

| Biscuits | B. vulgaris | [114] | |

| Candies | B. vulgaris | [115] | |

| Banana spread | Basella rubra | [116] | |

| Beverages, smoothie-like beverages | B. vulgaris | [113,117] | |

| Noodle | Amaranthus tricolor | [118] | |

| Pork meat | - | [64] | |

| Rainbow trout fillets | B. vulgaris | [119] | |

| Food packaging | Furcellaran films | B. vulgaris | [120] |

| Starch/polyvinyl alcohol films | Stenocereus stellatus | [121] | |

| Ammonium chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol films | O. ficus-indica | [122] | |

| Ammonium chitosan films | A. tricolor | [123] | |

| Textiles | Colored wool | O. ficus-indica | [124] |

| Colored wool | B. vugaris | [125] | |

| Bioactive cotton fabrics | B. vugaris | [126] | |

| Betalain-dyed nonwoven cotton fibers | B. vugaris | [127] | |

| Cosmetics and pharmaceuticals | Lipsticks | H. polyrhizus | [128] |

| Facial cosmetic | Amaranthus sp. | [129] | |

| Other applications | Dye-sensitized solar cells | Phytolacca americana, B. vulgaris; Bougainvillea sp. | [130,131,132,133] |

| Betalain-based biosensors | B. vulgaris | [134,135] | |

| Metal coating | B. vulgaris | [136] | |

| Organometallic reductants, stabilizing agents | B. vulgaris | [137] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).