Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

18 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Philosophy, Mathematics and Art

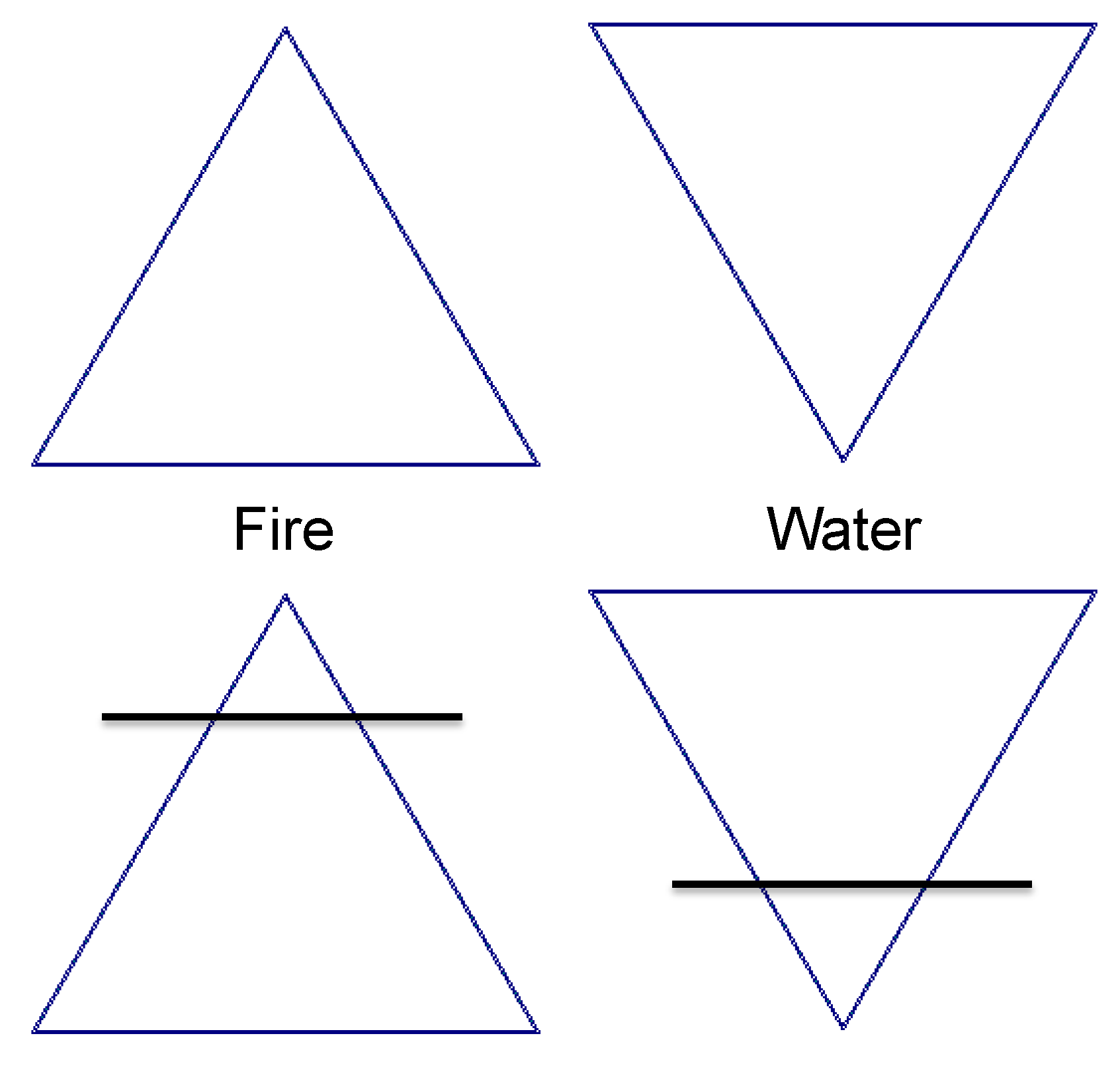

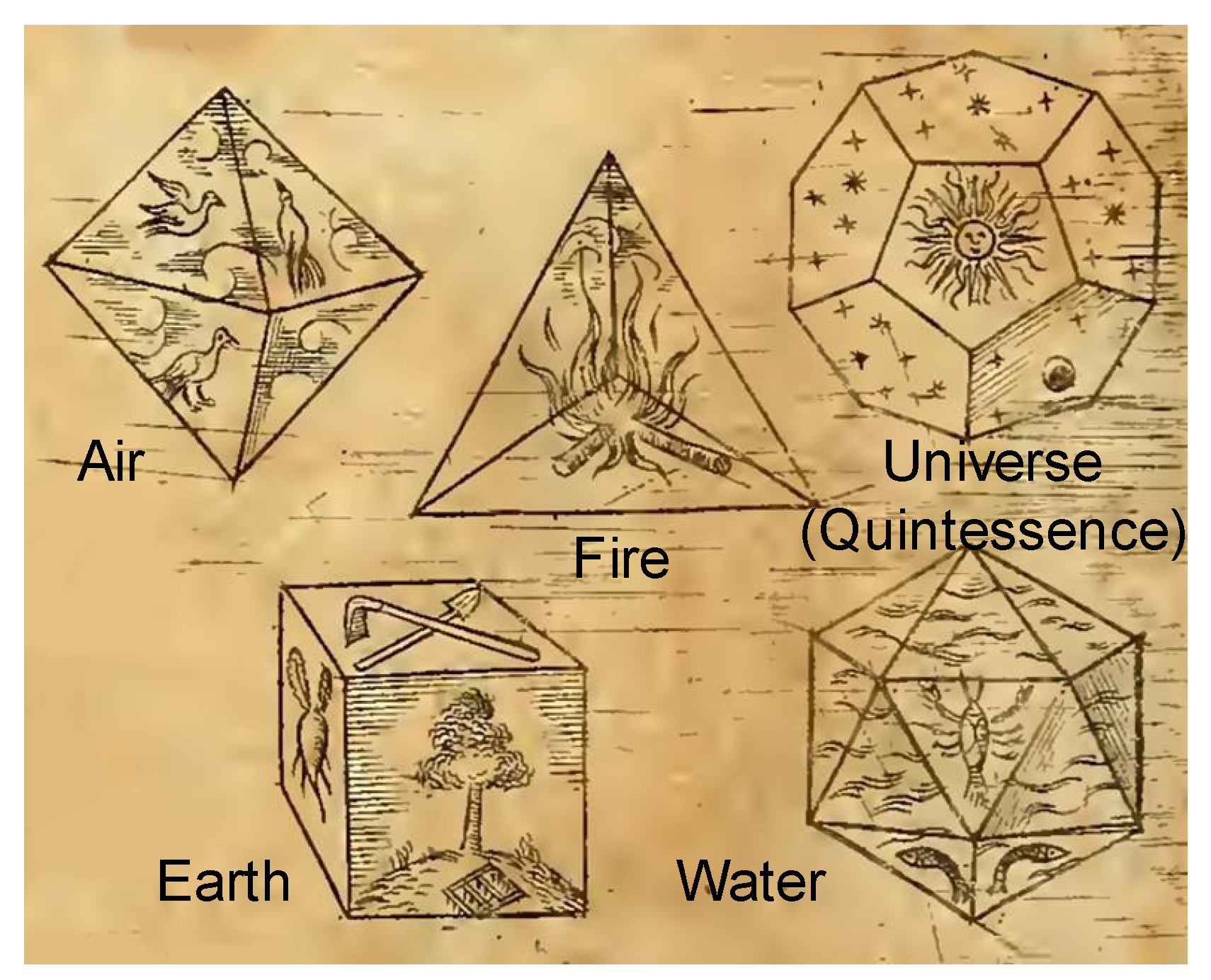

2.1. Plato

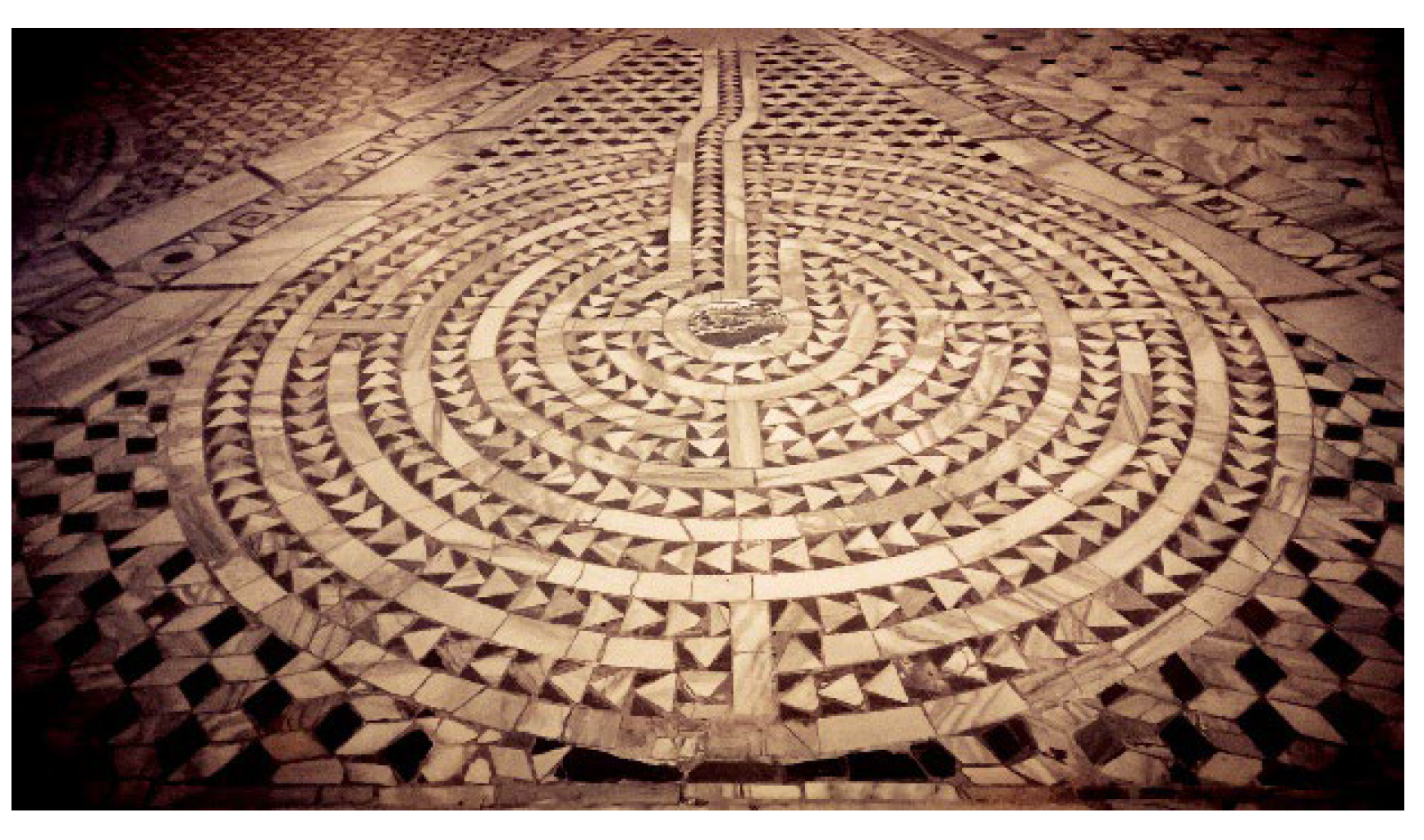

2.2. Ancient Art and Cosmatesque Decorations

2.3. Other Cultural Environments Using Triangles

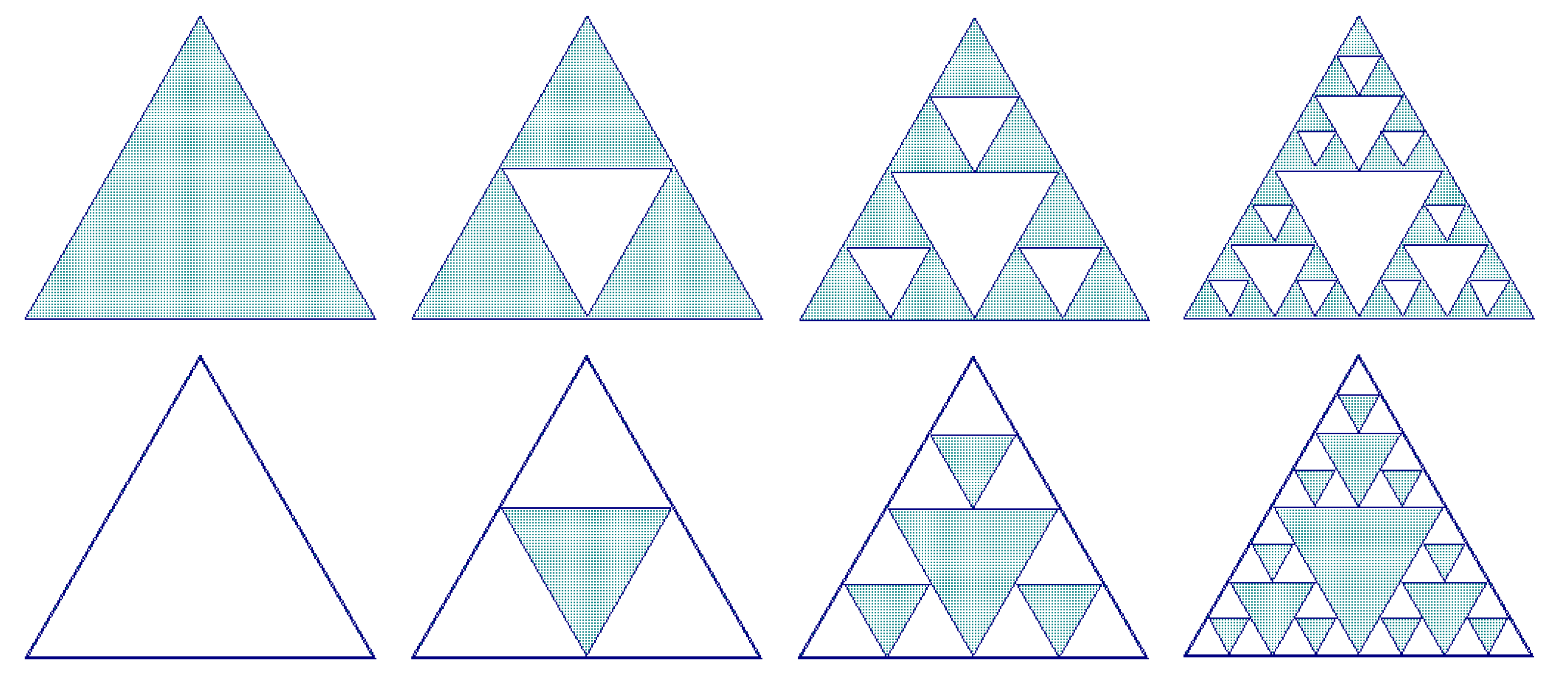

3. Mathematics and Geometry of Sierpinski Fractals

4. High Frequency Applications

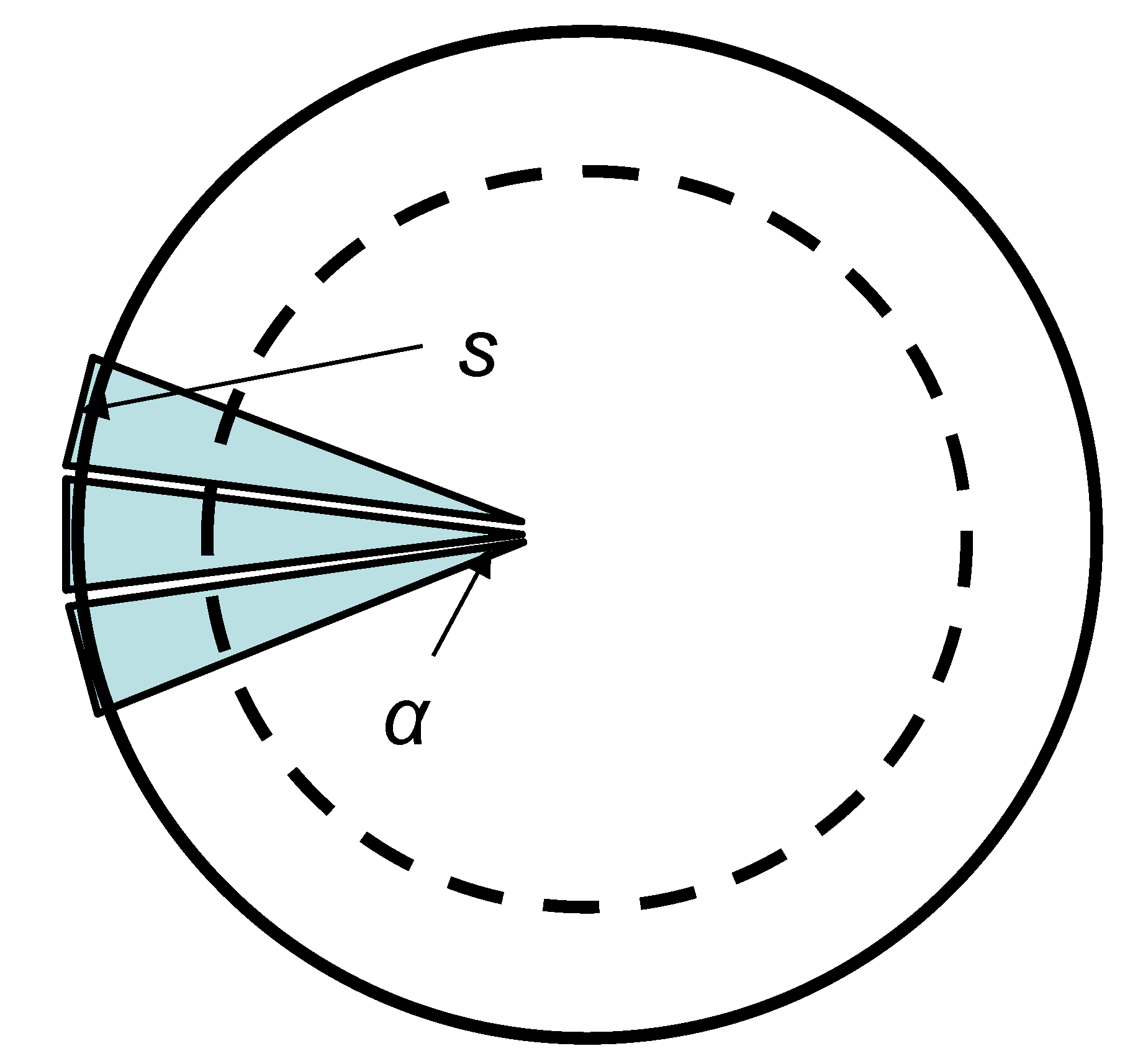

4.1. Resonance Frequencies

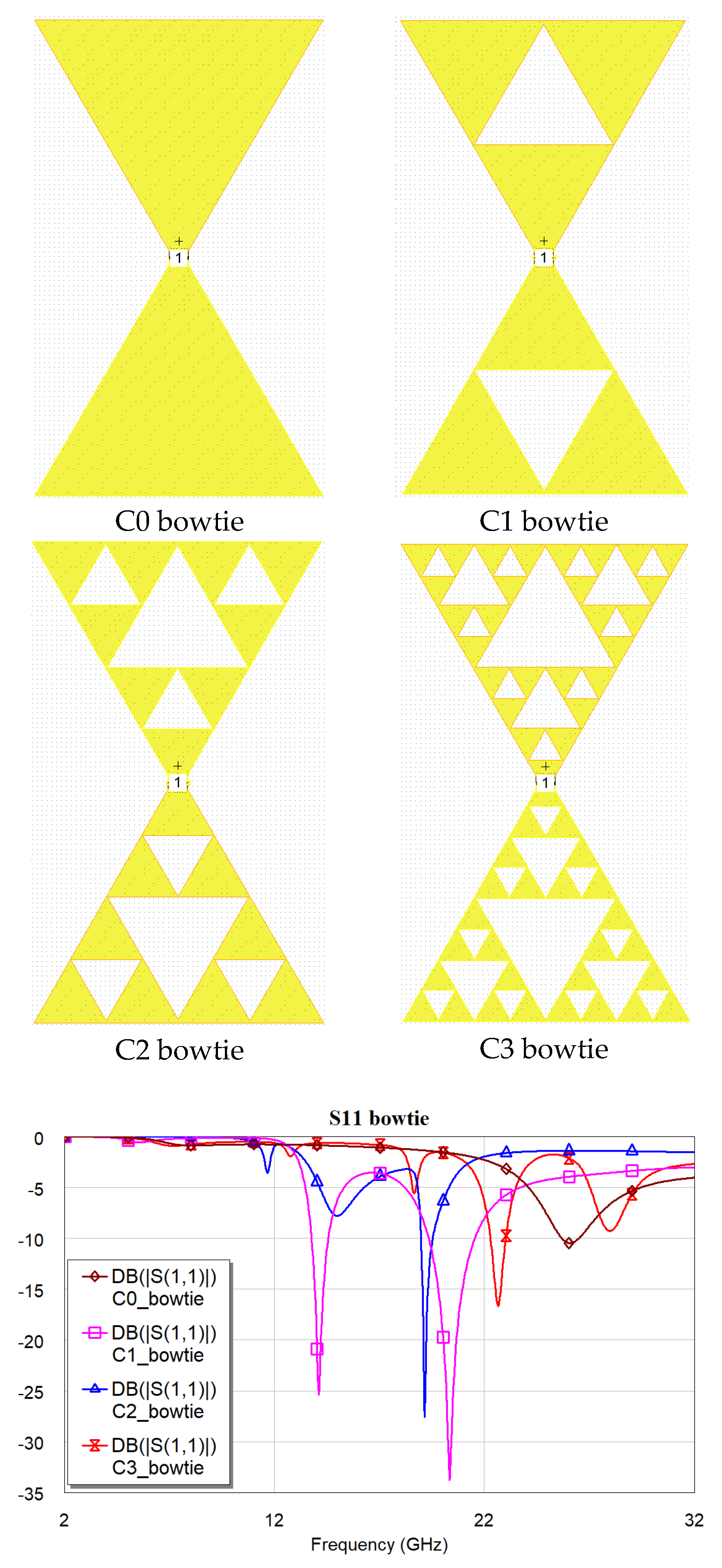

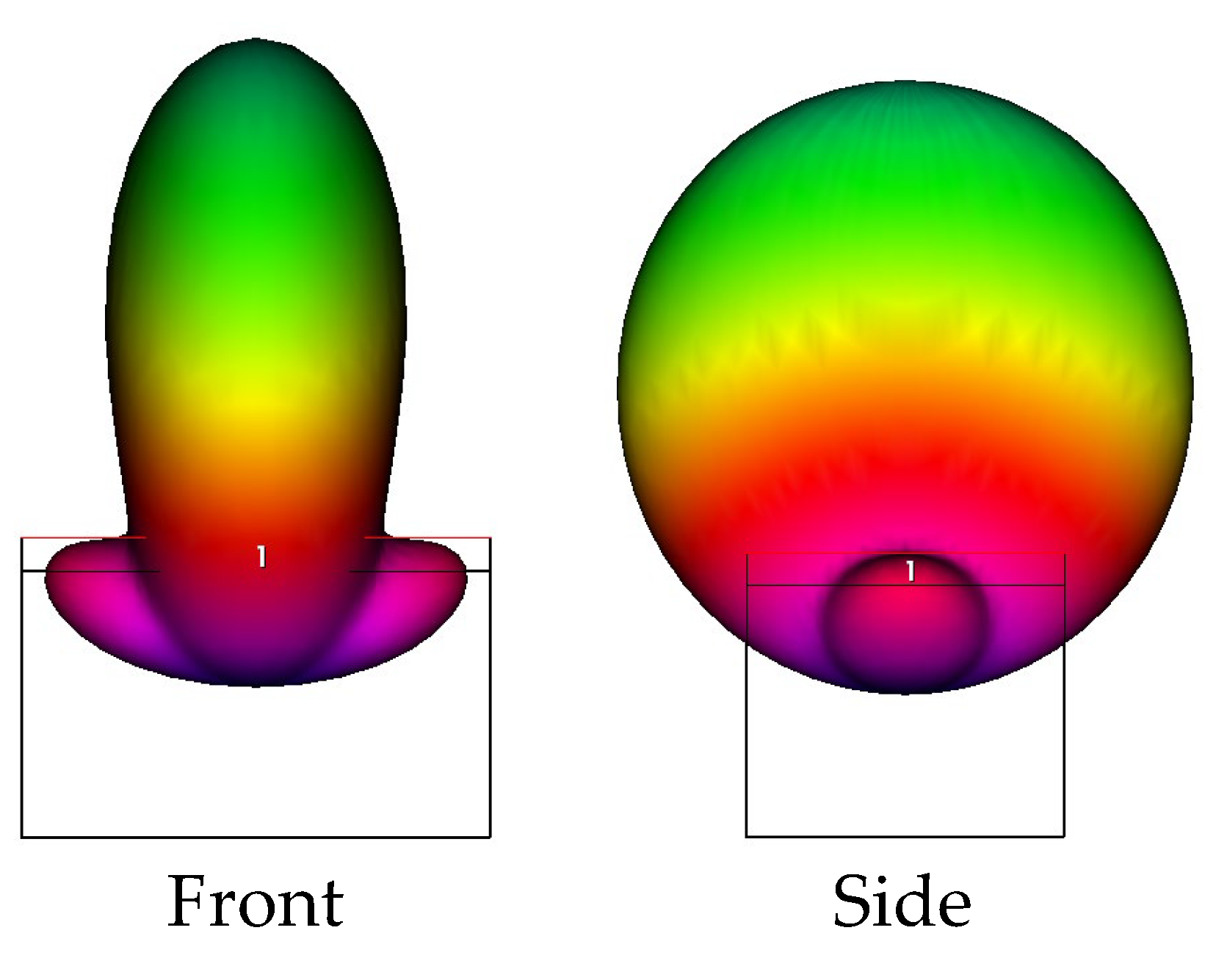

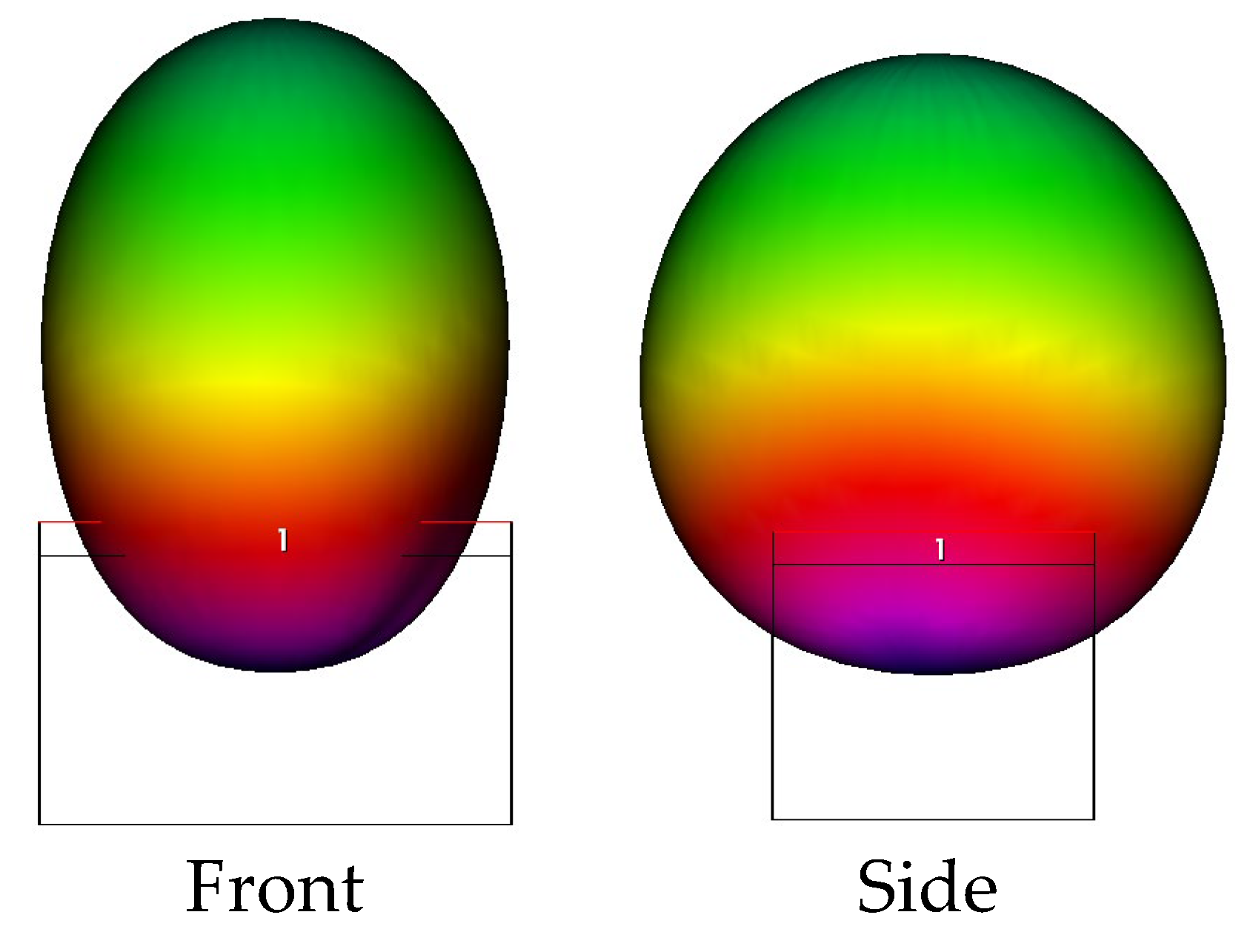

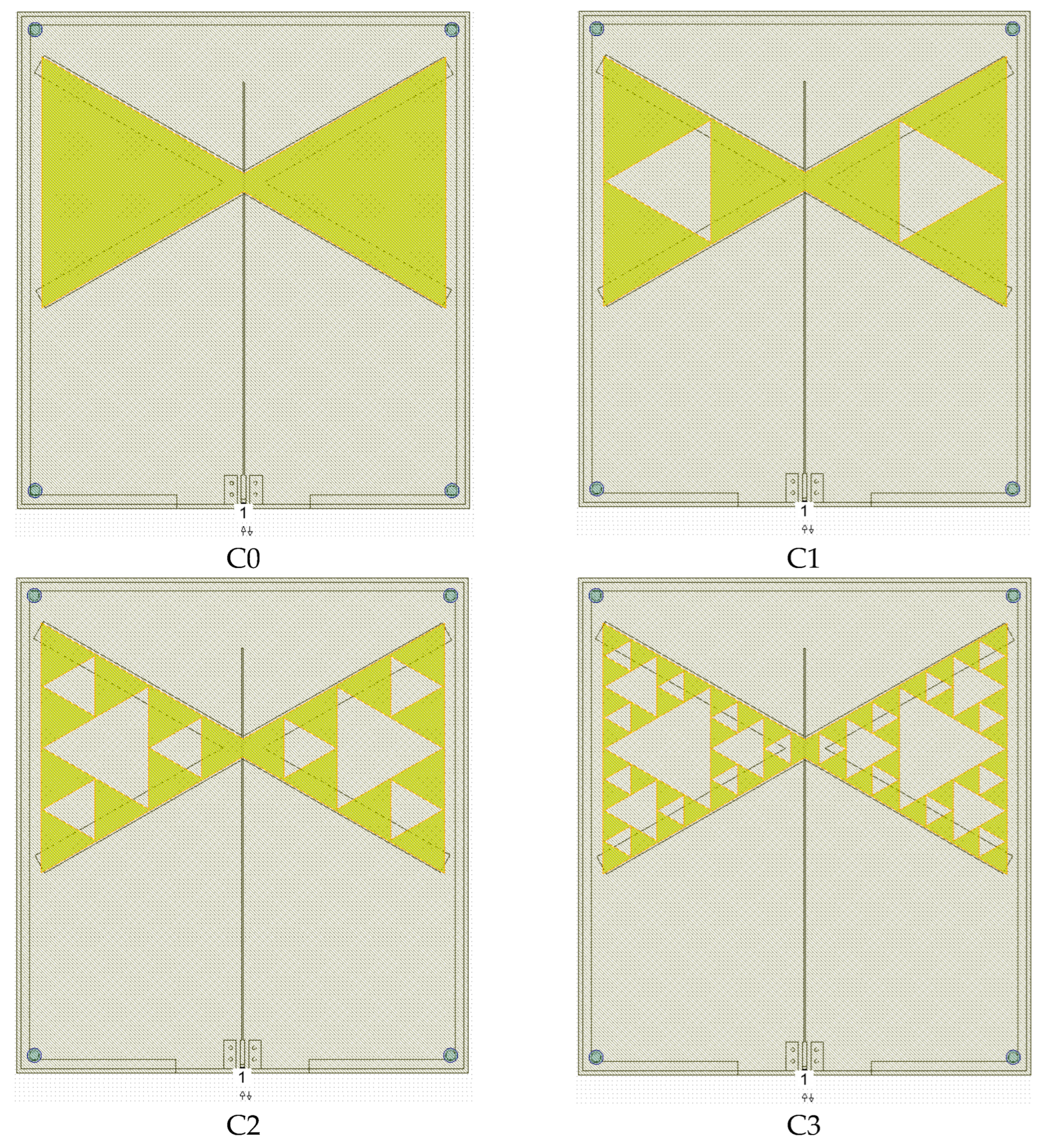

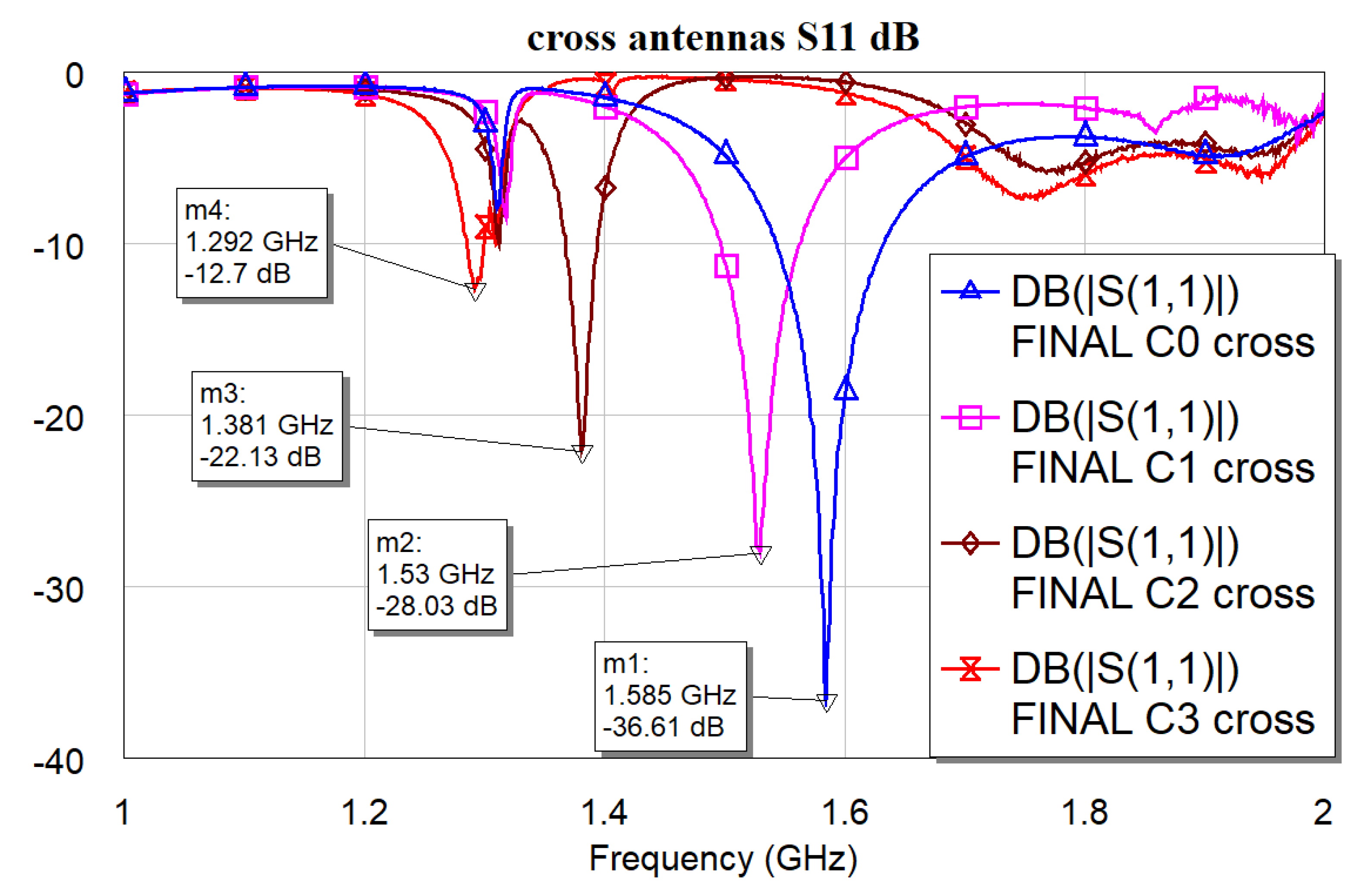

4.2. Antennas

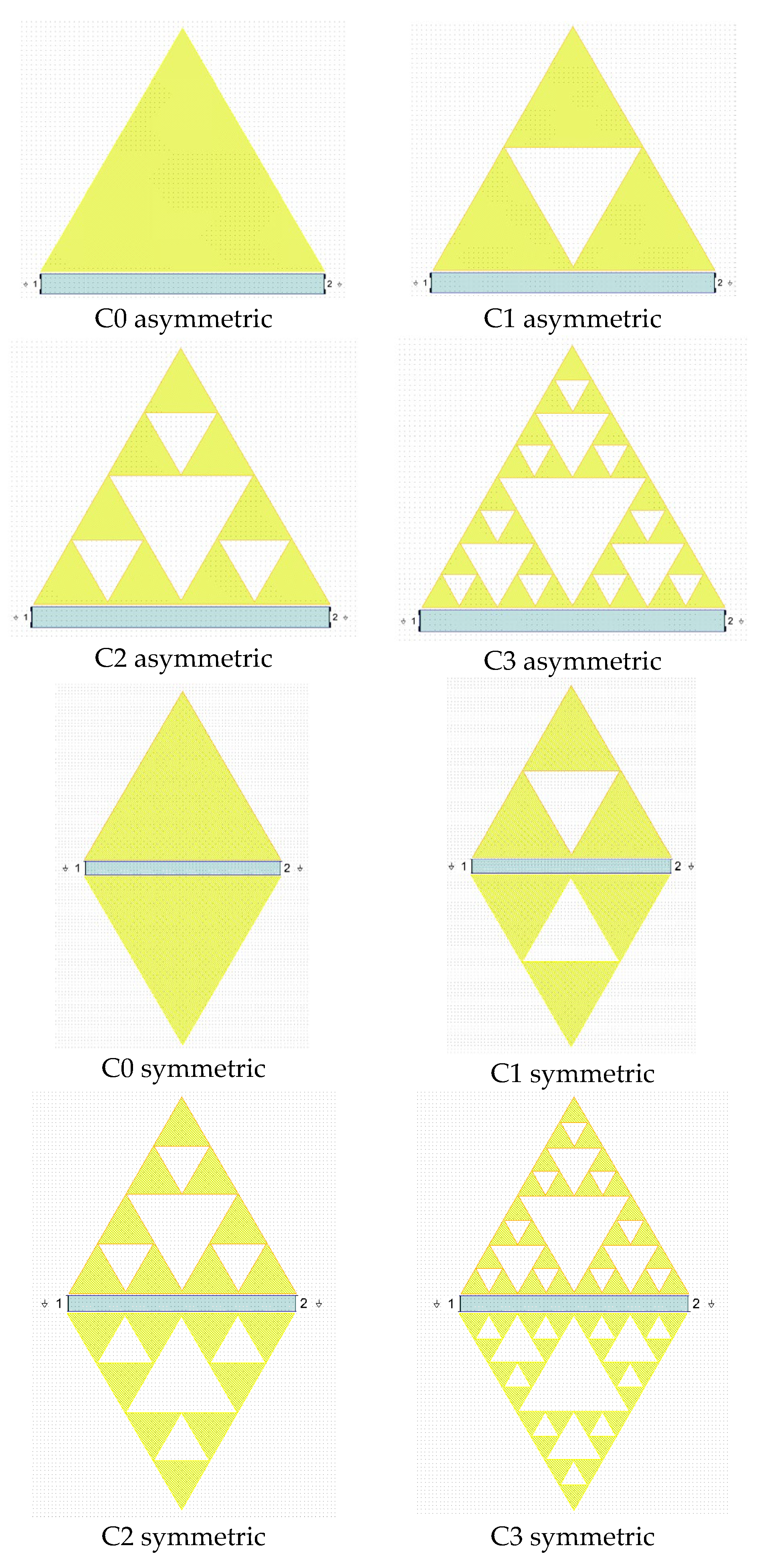

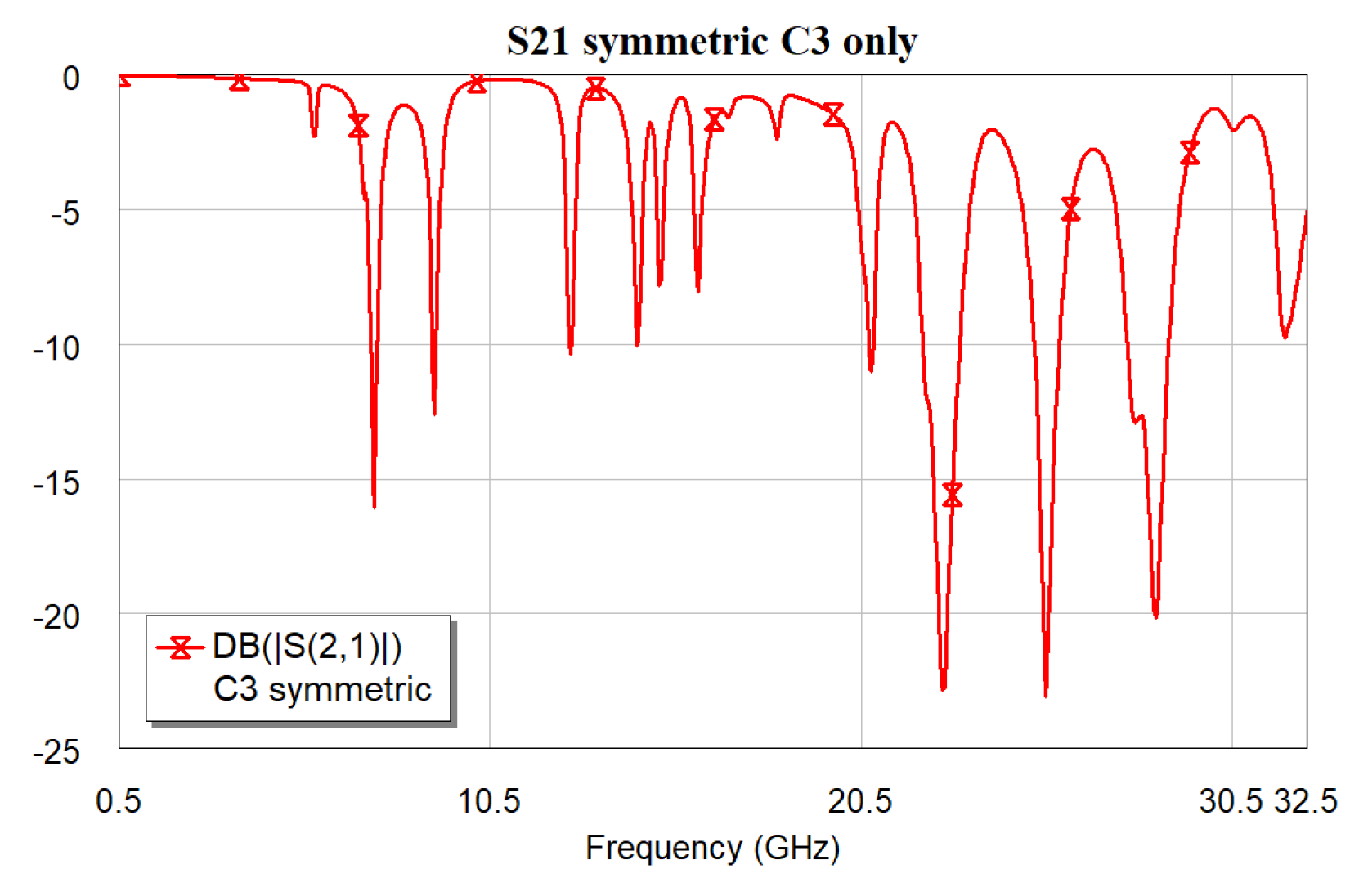

4.3. Resonators

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Pythagorean theorem”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 10 May. 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/Pythagorean-theorem. Accessed 14 June 2024.

- Mark Burgin, “Platonic Triangles and Fundamental Triads as the Basic Elements of the World”, Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts – 2018. Volume 5, Issue 1 – Pages 29-44. [CrossRef]

- Benno Artmann and Lothar Schaefer, “On Plato’s “Fairest Triangles” (Timaeus 54a)”, HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 20 (1993), 255-264. [CrossRef]

- David R. Lloyd, “Symmetry and Beauty in Plato”, Symmetry 2010, 2, 455-465. [CrossRef]

- Waclaw Sierpinski, “Pythagorean Triangles”, Dover Publications Inc., Mineola, NY 11501. https://www.softouch.on.ca/kb/data/Pythagorean%20Triangles.pdf.

- Ian Stewart, “number symbolism”, Encyclopedia Britannica, 15 Feb. 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/number-symbolism. Accessed 19 June 2024.

- Paloma Pajares-Ayuela, “Cosmatesque Ornament: Flat Polychrome Geometric Patterns in Architecture” London and New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

- Warwick Rodwell, David S. Neal: “The Cosmatesque Mosaics of Westminster Abbey: The Pavements and Royal Tombs: History, Archaeology, Architecture and Conservation”, Oxbow Books, 2019.

- Nicola Severino, “COSMATI: La firma dell’Artista. I tratti inequivocabili dell’arte cosmatesca della bottega di Lorenzo tra il XII e il XIII secolo. Alla scoperta del repertorio cosmatesco vero e definitivo di Lorenzo, Iacopo, Cosma e Figli. Studi sui Pavimenti Cosmateschi”, ilmiolibro.it, Cromografica, Roma, marzo 2014. Edizione digitale libera su academia.edu. Questa versione è stata corretta e modificata il 15 ottobre 2014 (in Italian).

- Benoit B. Mandelbrot, “The Fractal Geometry of Nature”, Henry Holt and Company, 1983, ISBN 0716711869, 9780716711865.

- Kenneth Falconer, “Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications”. John Wiley & Sons. xxv. ISBN 978-0-470-84862-3 (2003).

- Waclaw Sierpinski, “Sur une courbe dont tout point est un point de ramification”. Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris. 160: 302–305 (1915).

- A. Bickle, “Properties of Sierpinski Triangle Graphs”. In: Hoffman, F., Holliday, S., Rosen, Z., Shahrokhi, F., Wierman, J. (eds) Combinatorics, Graph Theory and Computing. SEICCGTC 2021. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, vol 448. Springer, Cham. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Qiang Sun, Liangliang Cai, Honghong Ma, Chunxue Yuan, and Wei Xu, “On-surface construction of a metal–organic Sierpinski triangle”, Chem. Commun., 2015, 51, 14164. [CrossRef]

- https://it.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/158786-sierpinski-triangle-generator, accessed on Jult 7th, 2024.

- https://download.cnet.com/sierpinski-triangle/3000-18498_4-75864275.html?ex=RAMP-2070.4, accessed on July 7th, 2024.

- https://www.comsol.it/multiphysics/finite-element-method, accessed on July 7th, 2024.

- Siliang Guo, Wengang Chen, Haijun Wang, Zhaoling Qiu, Beichao Wei, Jiahao Cheng, Haoen Yuan, Yihao Zhou, Hai Luo, “Simulation and experimental research on the cavitation phenomenon of wedge-shaped triangular texture on the surface of 3D-printed titanium alloy materials”, Tribology International, Volume 198, 2024, 109869, ISSN 0301-679X. [CrossRef]

- Guru Prasad Mishra, Madhu Sudan Maharana, Sumon Modak, B.B. Mangaraj, “Study of Sierpinski Fractal Antenna and Its Array with Different Patch Geometries for Short Wave Ka Band Wireless Applications”, Procedia Computer Science, Volume 115, 2017, Pages 123-134, ISSN 1877-0509. [CrossRef]

- R. Marcelli, G. Capoccia, G.M. Sardi, G. Bartolucci, B. Margesin, J. Iannacci, G. Tagliapietra, F. Giacomozzi, E. Proietti: “Metamaterials based RF microsystems for telecommunication applications”, Ceramics International, Volume 49, Issue 14, Part B, 2023, Pages 24379-24389, ISSN 0272-8842. [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosopher%27s_stone, accessed on March 14th, 2025.

- Paracelsus: Essential Readings. Selected and translated by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1999.

- Michael R. Shirts, David L. Mobley, John D. Chodera, Chapter 4 Alchemical Free Energy Calculations: Ready for Prime Time?, Editor(s): D.C. Spellmeyer, R. Wheeler, Annual Reports in Computational Chemistry, Elsevier, Volume 3, 2007, Pages 41-59, ISSN 1574-1400, ISBN 9780444530882. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1574140007030046). [CrossRef]

- Sheenam Khuttan, Solmaz Azimi, Joe Z. Wu, Emilio Gallicchio, “Alchemical Transformations for Concerted Hydration Free Energy Estimation with Explicit Solvation”, arXiv:2005.06504v2 [q-bio.QM]. [CrossRef]

- Eric John Holmyard, Alchemy, 1990, Dover Publication, New York, ISBN 10 0486262987, Originally Published: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin, 1957.

- Plato, Timaeus, Peter Kalkavage (Translation), Focus Publishing/R Pullins & Co, 2016.

- Dietmar Herrmann: “Ancient Mathematics - History of Mathematics in Ancient Greece and Hellenism”, ISBN 978-3-662-66493-3 ISBN 978-3-662-66494-0 (eBook), SPRINGER (2023). [CrossRef]

- Johannes Kepler, 1571-1630; “Harmonices Mundi”, Ptolemy, 2nd cent; Fludd, Robert, 1574-1637; Tambach, Gottfried, fl. 1607-1632, publisher; Planck, Johann, fl. 1615-1627, printer; Burndy Library, donor. DSI. https://archive.org/details/ioanniskepplerih00kepl/mode/2up.

- M. Emmer: “Art and Mathematics: The Platonic Solids.” Leonardo, vol. 15 no. 4, 1982, p. 277-282. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/600238.

- Dirk Huylebrouck, “Dark and Bright Mathematics: Hidden Harmony in Art, History and Culture”, Birkhä, user, Copernicus Books, ISBN 978-3-031-36254-5, ISBN 978-3-031-36255-2 (eBook), (book published under the imprint Birkhäuser, www.birkhauser-science.com by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Joel Kalvesmaki, “The Theology of Arithmetic: Number Symbolism in Platonism and Early Christianity”, Hellenic Studies Series 59. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies (2013). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_KalvesmakiJ.The_Theology_of_Arithmetic.2013.

- Juan Eduardo Cirlot, “A Dictionary of Symbols: Revised and Expanded Edition”, Jack Sage (Translator), Valerie Miles (Translator), Victoria Cirlot (Afterword), Herbert Read (Foreword), NYRB Classics (1963 First Ed., 2020) ISBN-10: 1681371979, ISBN-13: 978-1681371979.

- Williams, K. Paloma Pajares-Ayuela, “Cosmatesque Ornament: Flat Polychrome Geometric Patterns in Architecture”, Nexus Netw J 5, 144–145 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Elisa Conversano, Laura Tedeschini Lalli, “Sierpinski Triangles in Stone, on Medieval Floors in Rome”, Journal of Applied Mathematics, Aplimat, volume 4 (2011), number 4, pp.113-122.

- Paola Brunori, Paola Magrone, and Laura Lalli Tedeschini (2018-07-07), “Imperial Porphyry and Golden Leaf: Sierpinski Triangle in a Medieval Roman Cloister”, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol. 809, Springer International Publishing, pp. 595–609. ISBN 9783319955872, S2CID 125313277. [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangular_theory_of_love.

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/see-a-rare-alignment-of-all-the-planets-in-the-night-sky.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Illusory_contours.

- Alany RG, Tucker IG, Davies NM, Rades T. “Characterizing colloidal structures of pseudoternary phase diagrams formed by oil/water/amphiphile systems”. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2001 Jan;27(1):31-8. PMID: 11247533. [CrossRef]

- Qian Cheng, Jianfei Yin, Jihong Wen, Dianlong Yu, Mechanical properties of 3D-printed hierarchical structures based on Sierpinski triangles, International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Volume 247, 2023, 108172, ISSN 0020-7403. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020740323000747). [CrossRef]

- Balwinder S. Dhaliwal and Shyam S. Pattnaik, “Artificial Neural Network Analysis of Sierpinski Gasket Fractal Antenna: A Low Cost Alternative to Experimentation”, Hindawi Publishing Corporation, Advances in Artificial Neural Systems, Volume 2013, Article ID 560969, 7 pages. [CrossRef]

- Kyle Steemson and Christopher Williams: “Generalised Sierpinski Triangles”, arXiv:1803.00411v1 [math.DS] 27 Feb 2018.

- Rohit Gurjar, Dharmendra K. Upadhyay, Binod K. Kanaujia, Amit Kumar, “A compact modified Sierpinski carpet fractal UWB MIMO antenna with square-shaped funnel-like ground stub”, AEU - International Journal of Electronics and Communications, Volume 117, 2020, 153126, ISSN 1434-8411. [CrossRef]

- J. Dahele, K. Lee, “On the resonant frequencies of the triangular patch antenna”. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1987, 35, 100–101. [CrossRef]

- J. Helszajn, and D. S. James, “Planar Triangular Resonators with Magnetic Walls”, IEEE Trans. On Microwave Theory and Tech., Vol. MTT-26, pp. 95-100, 1978. [CrossRef]

- R. Marcelli, G.M. Sardi, E. Proietti, G. Capoccia, J. Iannacci, G. Tagliapietra, F. Giacomozzi, “Triangular Sierpinski Microwave Band-Stop Resonators for K-Band Filtering”. Sensors 2023, 23, 8125. [CrossRef]

- R.K. Mishra, R. Ghatak, D.R. Poddar, “Design Formula for Sierpinski Gasket Pre-Fractal Planar-Monopole Antennas” [Antenna Designer’s Notebook]. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2008, 50, 104–107. [CrossRef]

- A.P. Anuradha, S.N. Sinha, “Design of Custom-Made Fractal Multi-Band Antennas Using ANN-PSO” [Antenna Designer’s Notebook]. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2011, 53, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Pinaki Mukherjee, Alok Mukherjee, Kingshuk Chatterjee, “Artificial Neural Network based Dimension Prediction of Rectangular Microstrip Antenna”, Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series B, (2022). [CrossRef]

- N. Kumprasert and W. Kiranon, “Simple and accurate formula for the resonant frequency of the equilateral triangular microstrip patch antenna” in IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1178-1179, Aug. 1994. [CrossRef]

- S.Krishna Priya, Jugal Kishore Bhandari, M.Krishna Chaitanya, “Design and Research of Rectangular, Circular and Triangular Microstrip Patch Antenna”, International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE), ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8 Issue-12S, October 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Guney, and E. Kurt, “Effective side length formula for resonant frequency of equilateral triangular microstrip antenna”, International Journal of Electronics, vol. 103, no. 2, pp. 261–268, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bahl, P. Barthia, Microwave Solid State Circuit Design, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1988.

- J. Helszajn and D. S. James, “Planar Triangular Resonators with Magnetic Walls,” in IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 95-100, Feb. 1978. [CrossRef]

- Y. Akaiwa, “Operation Modes of a Waveguide Y Circulator (Short Papers),” in IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 954-960, Nov. 1974. [CrossRef]

- Y. Akaiwa, “Correction to “Operation Modes of a Waveguide Y Circulator” (Letters),” in IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 709-709, Jul. 1979. [CrossRef]

- M. Aldrigo et al., “Amplitude and Phase Tuning of Microwave Signals in Magnetically Biased Permalloy Structures” in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 190843-190854, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Geiler, S. Gillette, M. Shukla, P. Kulik and A. l. Geiler, “Microwave Magnetics and Considerations for Systems Design” in IEEE Journal of Microwaves, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 438-446, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A.K. Tagantsev, V.O. Sherman, K.F. Astafiev, J. Venkatesh & N. Setter, “Ferroelectric Materials for Microwave Tunable Applications”, Journal of Electroceramics, 11, 5–66, 2003, © 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Manufactured in The Netherlands.

- Sotyohadi, Riken Afandi, and Dony Rachmad Hadi, “Design and Bandwidth Optimization on Triangle Patch Microstrip Antenna for WLAN 2.4 GHz”, MATEC Web of Conferences 164, 01042 (2018). [CrossRef]

- K. Patel, S. Pandav and S. K. Behera, “Reconfigurable Fractal Devices,” in IEEE Microwave Magazine, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 41-62, July 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Dwivedy, S. K. Behera and V. K. Singh, “A Versatile Triangular Patch Array for Wideband Frequency Alteration With Concurrent Circular Polarization and Pattern Reconfigurability,” in IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 1640-1649, March 2019. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G., Qi, T., Li, M. et al.: “A low-profile broadband crossed-dipole antenna with fractal structure and inverted-L plates”. Sci Rep 12, 14960 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dr.S.Sathiya Priya, S.Nalini, R.Sandhiya, S.Sneha, “Performance and Analyze of Cross Dipole Antenna with Parasitic Elements”, International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), Volume: 07 Issue: 05 | May 2020, pp.915-919.

- Rogers Corporation, RO5880 Data Sheet. https://www.rogerscorp.com/-/media/project/rogerscorp/documents/advanced-electronics-solutions/english/data-sheets/rt-duroid-5870---5880-data-sheet.pdf, accessed on July 7th, 2024.

- G. Karunakar, V. Dinesh, “Analysis of microstrip triangular fractal antennas for wireless application”, International Journal of Innovative Research in Electrical, Electronics, Instrumentation and Control Engineering, Vol. 2, Issue 12, December 2014, ISSN (Online) 2321 – 2004, ISSN (Print) 2321 – 5526.

- J. Helszajn and D. S. James, “Planar Triangular Resonators with Magnetic Walls” in IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 95-100, Feb. 1978. [CrossRef]

- Romolo Marcelli: “Equivalent Circuits for Microwave Metamaterial Planar Components”. MDPI Sensors, SI: Metamaterials and Antennas for Enhancing Sensing, Imaging and Communication System, Sensors | Special Issue: Metamaterials and Antennas for Enhancing Sensing, Imaging and Communication System (mdpi.com). Sensors 2024, 24, 2212. [CrossRef]

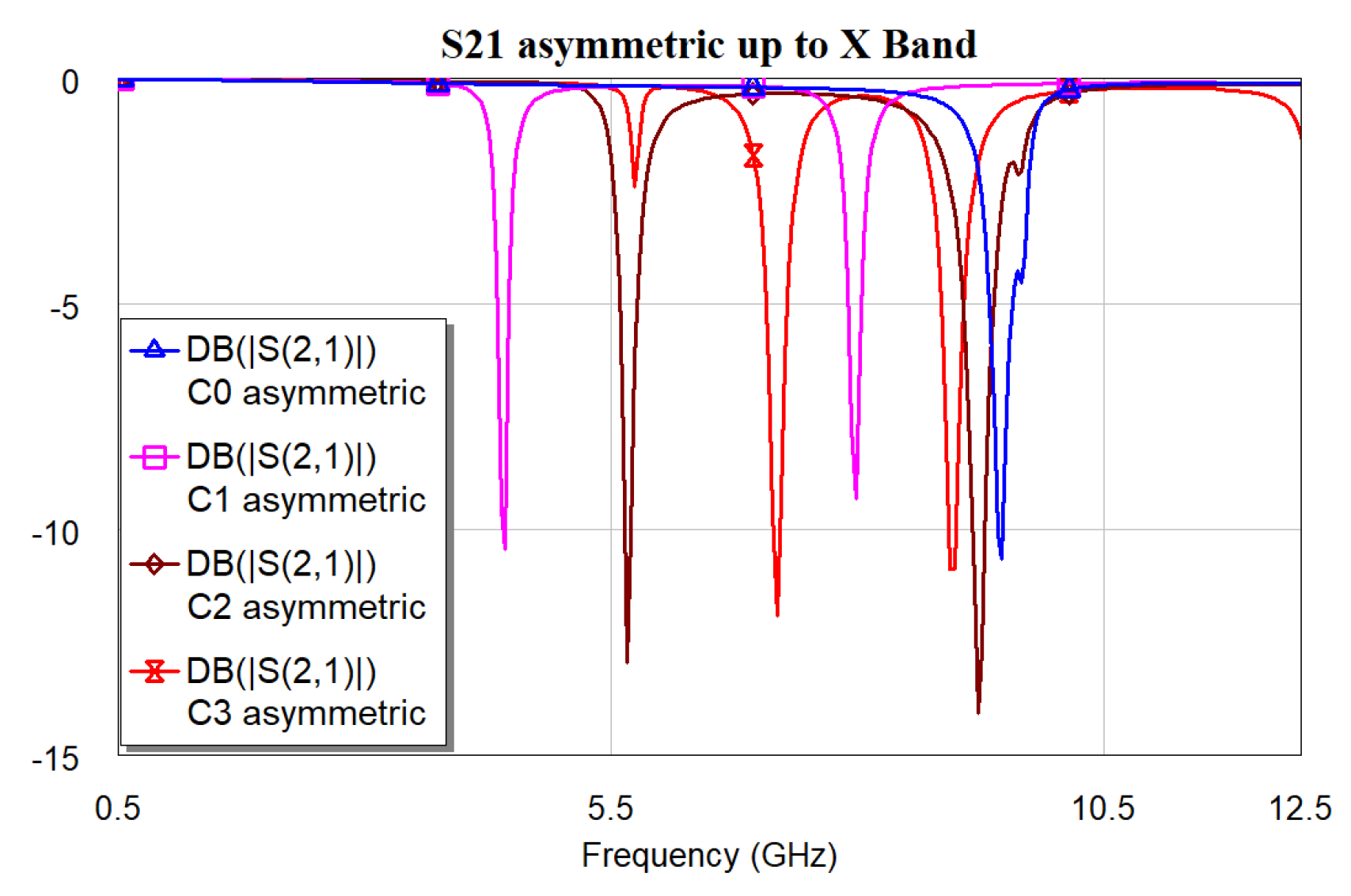

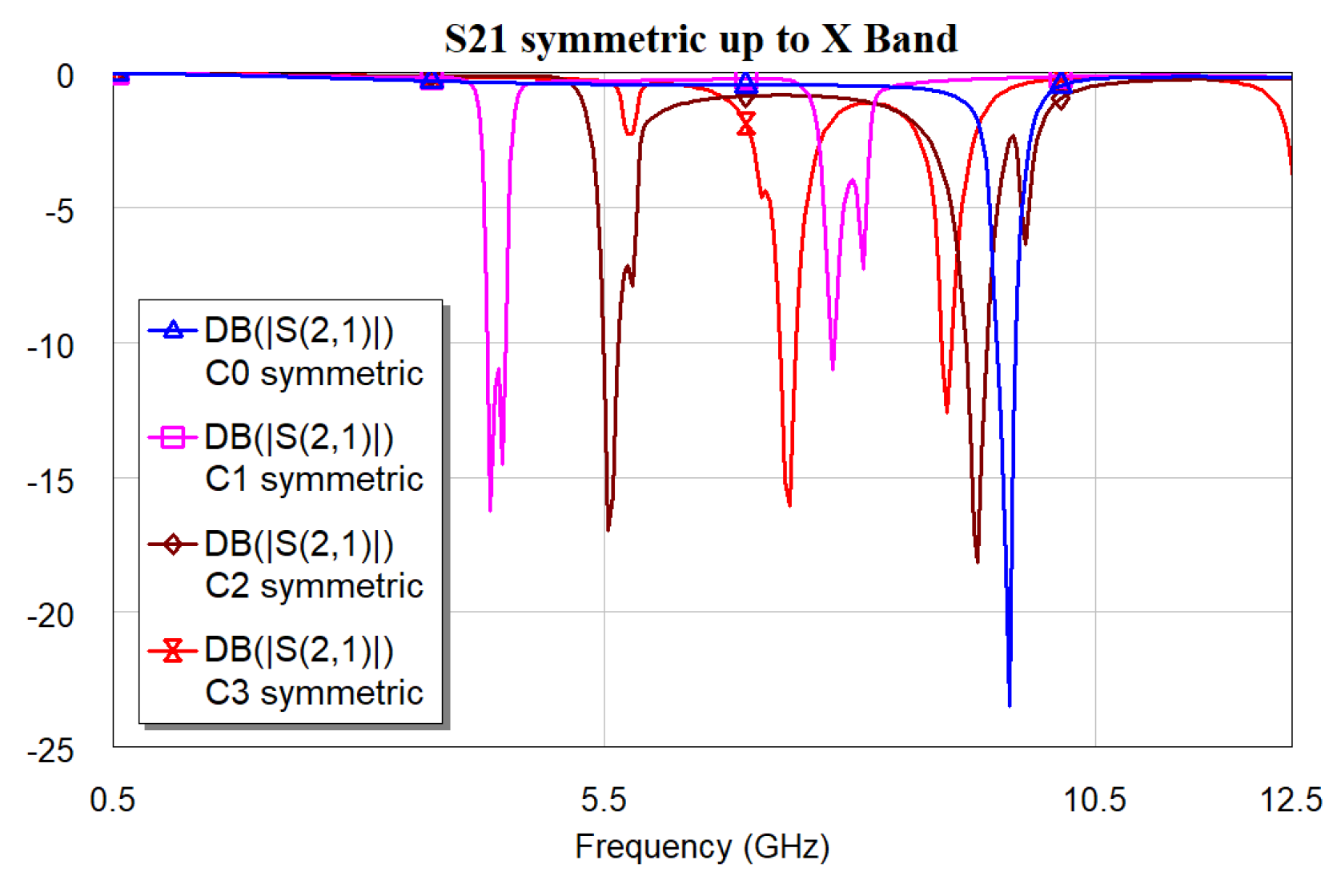

| Resonator | Resonance frequencies [GHz] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fres1 | Fres2 | Difference | |

| C0 asym | 9.46 | --- | --- |

| C1 asym | 4.42 | 7.98 | 3.56 |

| C2 asym | 5.66 | 9.22 | 3.56 |

| C3 asym | 7.18 | 8.94 | 1.76 |

| C0 sym | 9.62 | --- | --- |

| C1 sym | 4.34 | 7.82 | 3.48 |

| C2 sym | 5.54 | 9.30 | 3.76 |

| C3 sym | 7.38 | 8.98 | 1.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).