Introduction

Waterborne diseases are a global burden causing several million deaths and uncounted cases of sickness every year (Ramírez-Castillo et al., 2015). These infectious illnesses are emerging or resurging due to factors such as coastal development, climate change, and extreme events including marine heatwaves, which alter the environment for favourable growth and survival of microbial pathogens. Over the past 20 years, global sea surface temperatures (SST) have increased by about 0.4°C and by the end of the century they are projected to rise anywhere between an additional 0.9-5.4°C (IPCC, 2019). This warming trend has led to various issues including decreased biodiversity and variability, and ecosystem loss (Prakash, 2021). Another major consequence of higher SST is the growth of marine pathogens as some harmful bacteria, such as those belonging to genus Vibrio, prefer the warm and brackish waters typically found in coastal areas and estuaries (Froelich & Daines, 2020). As water temperatures continue to rise, these species are likely to become more abundant (Brumfield et al., 2021). Projections show that even under the most unfavorable scenario a global increase in 38,000 km of coastline areas suitable for Vibrio could occur by 2100 (Trinanes & Martinez-Urtaza, 2021). This spatial expansion of disease burden for Vibrio infections is predicted, particularly at higher latitudes, indicating an increased future risk in temperate regions. In coastal communities, this raises public health concerns because these areas often serve as a main water source and are heavily involved in the seafood industry and recreational activities (Craun, 1986). Contaminated seafood and water have caused millions of individuals worldwide to suffer from illnesses like typhoid, cholera, and harmful infections (i.e. Salmonella and E. coli) because of pathogenic bacteria (Cabral, 2010).

Seaweeds form some of the largest bodies of marine vegetation in the world, supplying valuable ecological functions of carbon sequestration, nutrient recycling, and coastal habitat protection (Chung et al., 2017). Seaweed, as a versatile resource, has served assorted purposes throughout history including, food, medicine, cosmetics, biofuel, and agriculture (Buschmann et al., 2017). As a result of its varied uses, the seaweed aquaculture industry has experienced substantial growth in the past 25 years, with an annual harvesting production of around 35 million tonnes (Cai et al., 2021).

Seaweed holobionts, that is the ecological unit comprised of a host plant and its microbiota (Vandenkoornhuyse et al., 2015), are influenced by both abiotic and biotic factors in the marine environment, determining the dominant microbial species that colonize the algal surface (Düsedau et al., 2023; Singh & Reddy, 2014). This surface layer of the seaweed, referred to as the eco-chemosphere, is a region abundant in chemicals and nutrients released by seaweeds (Schmidt & Saha, 2020). When environmental stressors occur (e.g. temperature fluctuations, changes in nutrient availability, water deoxygenation, acidification (Ji & Gao, 2021)), seaweed can release copious amounts of amino acids and sugars into their eco-chemosphere and the surrounding water column as a response (Goecke et al., 2010; Mahmud et al., 2008). Bacteria in the marine environment including pathogenic Vibrio can then utilise the released materials for their advantage.

Vibrio spp. are gram-negative chemoorganotrophic bacteria that can be found on many coastal seaweed species (Sampaio et al., 2022; Thompson et al., 2004). For survival and growth, Vibrio utilises a multitude of compounds from seaweed such as galactose, fucose, and mannose through its ability to penetrate the epithelial membrane of their seaweed hosts (Kalvaitienė et al., 2023; Mahmud et al., 2008). Notably, Vibrio species are responsible for the highest amount of disease from the marine environment (Baker-Austin et al., 2018) and the most common pathogenic species attributed to this are Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus (Blackwell & Oliver, 2007; Sampaio et al., 2022). Infections can occur through various routes, including cuts, open wounds, the gastrointestinal tract, or inhalation, typically from exposure to contaminated water or consumption of raw or undercooked seafood (Sampaio et al., 2022). Individuals at higher risk include those with chronic health conditions, particularly liver disease, diabetes, or weakened immune systems (Daniels & Shafaie, 2000). Vibrio infections can lead to life-threatening complications such as septicaemia, necrotizing fasciitis, wound infections, gastrointestinal issues, and even death (Coerdt & Khachemoune, 2021). In northern Europe, Vibrio infections have increased in recent years, largely due to an increased presence of Vibrio in coastal waters (Amato et al., 2018; Fleischmann et al., 2022).

Vibrio abundance in the water is highly associated with seasonal temperature changes. Vibrio experiences exponential increases in abundance during warmer months and declines in colder months (Baker-Austin et al., 2018; Blackwell & Oliver, 2007; Mahmud et al., 2007; Trinanes & Martinez-Urtaza, 2021; Vezzulli et al., 2013). When environmental factors change, such as alterations in temperature or salinity, Vibrio demonstrates a remarkable ability to resist and even thrive under stress (Pruzzo et al., 2005) (i.e. entering a Viable but Non-culturable State (VBNC) (Brumfield et al., 2021; Oliver, 2005)). Vibrio optimally grows in water temperatures of above 15°C and salinities of below 25ppt (Baker-Austin et al., 2013; Froelich & Daines, 2020; Kaspar & Tamplin, 1993; Vezzulli et al., 2013). The abundance of Vibrio is notably influenced by temperature and salinity (Trinanes & Martinez-Urtaza, 2021) making these two environmental variables the most important for Vibrio studies (Froelich & Daines, 2020; Namadi & Deng, 2023) with other environmental factors such as dissolved oxygen, nitrogen, pH, suspended solids, and turbidity exerting only marginal effects (Geisser et al., 2025; Takemura et al., 2014).

The global increase in sea surface temperature (SST) has led to stress in a multitude of aquatic organisms and ecosystems (Niinemets et al., 2017). For seaweed, under environmental stress, the thallus degrades, prompting a release of nutrients into the environment (Kalvaitienė et al., 2023). This nutrient release has the potential to create an avenue for the attraction and adherence of opportunistic bacteria (Lutz et al., 2013; Mensch et al., 2016). It could therefore be plausible that Vibrio, an opportunistic pathogen, may thrive better in these new and changing conditions (Vezzulli et al., 2020).

Globally, seaweeds have been identified as reservoirs for Vibrio species, with major occurrences reported throughout nations in Asia where seaweed aquaculture is extensive (Mahmud et al., 2007; Tuhumury et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2008). However, Vibrio has been isolated in coastal regions across Europe (Haley et al., 2012; Rizzo et al., 2016; Ziino et al., 2010), North America (Barberi et al., 2010; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Michotey et al., 2020), and Africa (Akrong et al., 2023; Selvarajan et al., 2019). There have also been documented cases of Vibrio-related illnesses associated with the consumption and use of seaweed (Reilly, 2011). However, we do not know how the health of seaweed-dominated coastal communities and public health might be affected by ocean warming. Additionally, safety concerns could arise for regions that import large quantities of seaweed due to postharvest contamination (Akomea-Frempong et al., 2023). Currently, there are no studies linking future climate predictions of SST with abundance of pathogenic Vibrios on seaweed surfaces and what this means for consequent public health risks. Therefore, we investigated how ocean warming will alter the association of pathogenic Vibrio species (Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio alginolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae) with three different seaweed species and their surrounding water columns. Additionally, we examined whether Vibrio abundance will be significantly higher in certain seaweed species in response to warmer oceans.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

Three species of seaweeds, Fucus serratus (brown seaweed, hereafter F. serratus), Palmaria palmata, (red seaweed, hereafter P. palmata) and Ulva spp. (green seaweed, hereafter Ulva spp.) were collected from Plymouth Sound (50°21′50.4″N 4°08′45.5″W) on 3 June 2024 during low tide. Five biological replicates were taken from each species of seaweeds. All samples were transferred to the laboratory within 30 minutes of collection.

Surface Area Analysis

To relate surface area to wet weight, 10 individual samples from each seaweed species (F. serratus, P. palmata, and Ulva spp.) were spin-dried for 1 minute and weighed to determine their fresh weight. Photographs of all samples were then taken and ran through Image J software to calculate surface area. The total surface area of each sample was then normalized by dividing the Image J calculated surface area by the wet weight (cm²g⁻¹). These calculations were performed on separate samples (collected in May 2024) a few weeks prior to the main experiment, and the samples used for surface area calculations were not included in the main experiment. The resulting average surface areas were used in the main experiment calculations. The mean surface areas per species were as follows: 32.112 cm²g⁻¹ (SD ±1.932) for F. serratus, 60.212 cm²g⁻¹ (SD ±3.659) for P. palmata, and 175.904 cm²g⁻¹ (SD ±26.154) for Ulva spp. These averages were used for further analysis in the main experiment.

Temperature Experiment

The temperature experiment was conducted in a controlled temperature (CT) room from 3 June to 17 June 2024. Approximately 10 g of spin-dried fresh weight from each seaweed species was placed in aquaria containing 800 mL of ambient seawater (salinity ~34 PSU) collected from Plymouth Sound. The tanks were maintained under continuous aeration and a 12:12 h light:dark cycle, with a light intensity of 18.35 µmol/m²/s. Each seaweed species was represented by five biological replicates, each housed in a separate tank (n = 5), resulting in a total of five individuals per species across five replicate tanks.

Field temperature, 14°C (0.5 metre depth) was measured at the time of collection on 3rd June 2024. Two subsequent temperature treatments (+2°C (time point, T1) and +6°C (timepoint, T2)) were conducted based on RCP 8.5. Each temperature treatment lasted for 7 days. On days 0-7, the seaweed samples were kept in water of 16°C and days 7-14 the seaweed samples were kept in water of 20°C. The water in the aquaria was replaced three times throughout the experiment (on days 4, 7, and 10) using freshly collected field seawater from Plymouth Sound.

On day 7, the +2°C treatment was ended and 3 g (fresh weight) seaweed samples from each aquarium were collected for CFU counts along with water samples from the aquaria tank. Following the T1 sampling, the temperature of the aquaria was increased to +6°C and treatment was continued for 7 more days. The below sampling process was followed for T2 samples but with 4 g of each species.

Vibrio cholera/vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio alginolyticus Abundance

To test for abundance of Vibrio cholerae/vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio alginolyticus in response to temperature stress, 3 g (fresh weight after 1 minute spin drying) of the thallus from each replicate of each seaweed species were obtained from the T1 time point. The individuals were placed in a sterile falcon tube and filled with 10 mL of filtered sterile seawater (FSSW). The seaweeds were gently rinsed with FSSW to get rid of loosely attached bacteria. Another 10 mL of FSSW was added with the addition of sterile glass beads. The tube was then vortexed for 3 minutes at 2500 rpm to create a microbial soup of 10 mL. Same process was followed for T2 samples but with 4 g of each species.

The microbial soup from each seaweed replicate (10mL), 400 mL aquaria water (for T1) and 200 mL aquaria water (for T2) was filtered through a 0.22 μm gridded membrane filter individually. Replication level was 5 for each type of seaweed and 5 for each tank water sample. The filter paper from each replicate was placed on CHROMagar Vibrio (CHROMagar, Paris, France) plates and incubated at 37°C for a total of 72 hours. Colony counts were conducted manually and recorded at 24, 48, and 72 hours as colony-forming units (CFU). According to the manufacturer protocol, blue colonies were counted as presumptive Vibrio cholerae/Vibrio vulnificus, mauve colonies as presumptive Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and cream colonies as presumptive Vibrio alginolyticus. For data analysis, only the 72-hour bacterial colony counts were used.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Python (3.12.0) in Visual Studio Code (1.93). Data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Following this, a two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted at a 95% level of significance to examine interactions between factors. Post-hoc analysis was performed using Tukey’s HSD test to assess differences among temperature treatments and species tested.

Results

The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed that all variables were normally distributed, validating assumptions of normality for further analysis.

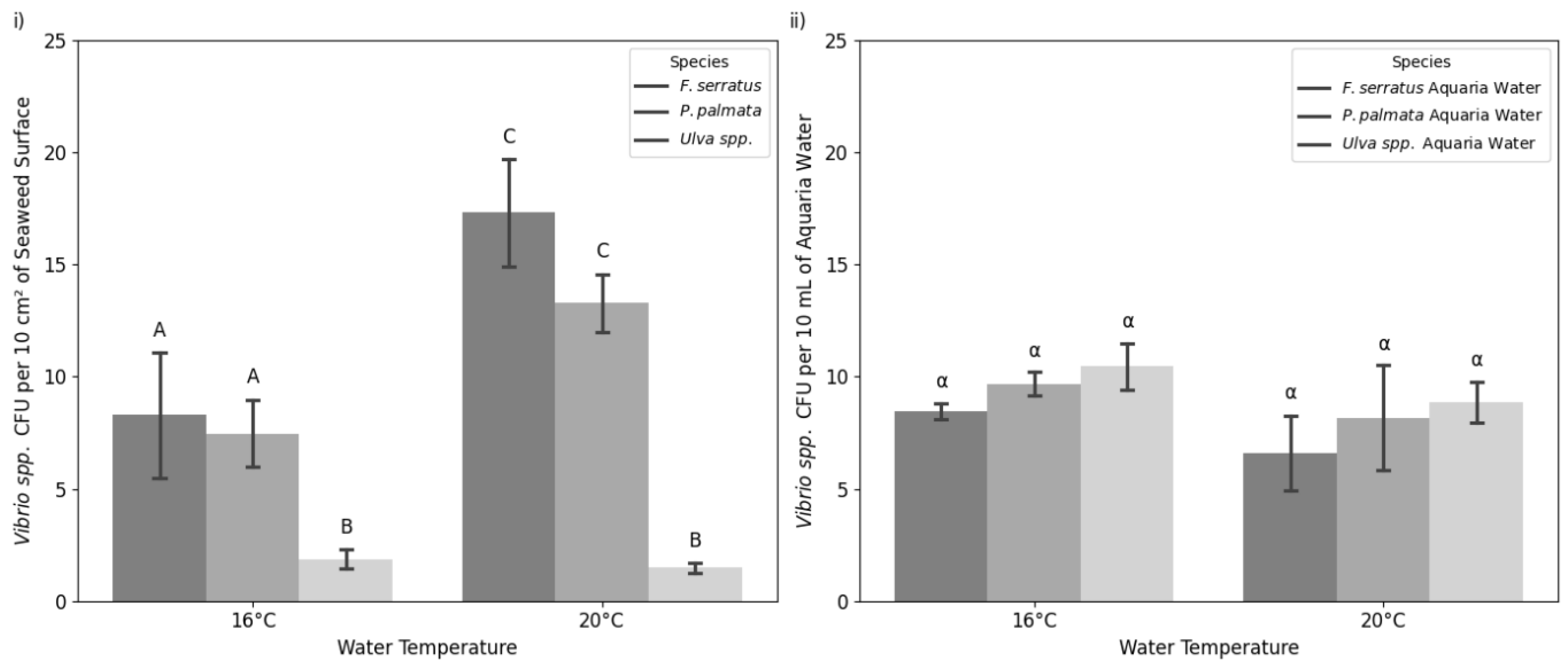

The two-way ANOVA revealed that both species and temperature significantly influenced

Vibrio CFU counts on seaweed surfaces (

Figure 1i), but not in the aquaria water (

Figure 1ii). In seaweed, species accounted for 75.08% of the variation (p<0.0002), temperature for 58.09% (p<0.0015), and the interaction between species and temperature for 47.70% (p<0.021). Post hoc Tukey’s tests indicated that

Vibrio CFU for

F. serratus and

P. palmata were not significantly different (p>0.51), but

Ulva. spp. had notably lower CFU than both species (p<0.0001, p<0.0013). Conversely, in the aquaria water, species explained only 17.83% of the variation (p>0.31), temperature 16.43% (p>0.15), and interaction less than 1% (p>0.99).

Discussion

This study investigated for the first time how ocean warming will affect the relationship between abundance of human pathogens Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus spp. on seaweed surfaces. Our findings demonstrate that increasing water temperatures as projected by RCP 8.5 will significantly increase the total abundance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus on Fucus serratus and Palmaria palmata surfaces. This has important future implications, as water temperatures are expected to rise significantly around the globe throughout the remainder of this century. Based on the findings of this study, warmer oceans will be expected to increase abundance of tested Vibrio species on certain seaweed surfaces which could pose risks to individuals who rely on seaweeds (e.g. for food, medicine, cosmetics, etc.) or are involved in the seaweed aquaculture industry, increasing the chances of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus infections (Griffis & Howard, 2013). The findings also have implications for recreational users given recreational use of the ocean has increased in recent years around the UK, promoted by various initiatives such as rock pooling events and structural improvements to designated bathing areas. This increase in public engagement with the marine environment will inevitably increase public exposure to Vibrio risk through contact with seaweed and the surrounding water, particularly during warmer months and marine heat waves.

Abundance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus spp. was also significantly different among seaweed species tested. Fucus serratus and Palmaria palmata had a significant higher growth of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus spp. than Ulva spp. when water temperatures rose to 20℃, indicating that not all seaweed species support the growth of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus spp. in the same manner with increasing water temperatures. This is likely due to physiological or biochemical differences among seaweed species such as variations in surface structure or nutrient release or difference in the surface chemistry of these tested species (Geisser et al., 2025; Singh & Reddy, 2014) which may create more favourable conditions for colonization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus spp. on certain species. These differences could also be attributed to distinct microbiomes associated with each seaweed species, as prior research has indicated that distinct species host unique bacterial communities (Wilkins et al., 2019; Nahor et al., 2024). Higher Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus spp. abundance on Fucus serratus and Palmaria palmata species could lead to regions dominated by these seaweeds having a higher potential for Vibrio-related illnesses (Del Olmo et al., 2018, Kalvaitienė et al., 2023) compared to areas where Ulva species are more prevalent (Qiao et al., 2021). The abundance of the tested Vibrio species did not vary significantly between the Ulva species at either temperature tested. However, their abundance was significantly lower on Ulva compared to Fucus serratus and Palmaria palmata. A recent study showed that actinobacteria dominate the microbial communities of Ulva species such as Ulva ohnoi (Flores et al. 2025) and Ulva rigida (Ismail et al. 2018). Actinobacteria are well-known producers of antimicrobial compounds. For instance, bioactive metabolites produced by Streptomyces spp. have been shown to modulate microbiota, stimulate host immunity, and offer protective effects against Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections (Loo et al. 2023). We therefore hypothesise that the reduced abundance of pathogenic Vibrio species on Ulva may be due to anti-Vibrio activity of actinobacteria present on the surface of the tested Ulva. Further work is needed to experimentally test this hypothesis.Seaweeds offer a sustainable source of nutrients, rich in vitamins, minerals, proteins, and fibres. These make it attractive not only for direct consumption but also as a component in animal feed, fertilizers, and biostimulants for agriculture. Additionally, seaweed-derived compounds are now used in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and bio-packaging. Thus, there has been a recent resurgence of interest in seaweed cultivation which includes the cultivation of kelps and Palmaria species (Kim et al., 2019), with Fucus species also being farmed in regions such as the Baltic Sea (Meichssner et al., 2020). Our results suggest careful consideration should be given to the species chosen for cultivation under the influence of ongoing climate change. Based on the findings, Ulva appears to be a better choice for farming due to its lower potential for harbouring pathogenic Vibrio colonies even under warmer water conditions.

Interestingly, while an increase in temperature significantly increased Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae and Vibrio alginolyticus abundance on seaweed surfaces, no such effect was observed in the respective aquaria water. This contrasts with previous field studies which have reported increased Vibrio levels in warmer water columns in the open ocean (Baker-Austin et al., 2018, Vezzulli et al., 2013; Trinanes et al., 2021). Several factors might explain this discrepancy. First, the experimental setup in this study was conducted in a controlled mesocosm environment, where salinity (~35ppt, relevant to the seaweed collection site) was above the ideal 25 ppt required for Vibrio proliferation (Namadi & Deng, 2023). Second, in natural ecosystems, a wider range of biotic and abiotic variables, such as nutrient fluctuations, competition, and non-climate-related stressors (such as invasive species, habitat destruction, and water pollution) could influence bacterial abundance more profoundly (Egan et al., 2013). Third, the findings could be due to Vibrio’s opportunistic nature. When seaweed is stressed by elevated temperatures and release more nutrients (de Oliveira et al., 2017), Vibrio bacteria may be more likely to remain attached to the seaweed surface to access those nutrients, rather than existing freely in the water column. This trend has been observed in other seaweed-dominated ecosystems (Michotey et al., 2020) as well as in seagrass meadows (Lamb et al., 2017). It is crucial to conduct future investigations into specific changes in Vibrio abundance in these seaweed-dominated ecosystems to gain a broader understanding of these patterns.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings report for the first time that the abundance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus/cholerae Vibrio alginolyticus will increase on certain seaweed species in response to mean temperature rise, particularly in areas where susceptible seaweed species, such as Fucus serratus and Palmaria palmata thrive. As sea surface temperatures continue to rise, these seaweed-dominated environments may serve as reservoirs for Vibrio, enhancing the risk of infections among coastal populations and those consuming seafood and using seaweeds from these regions. This susceptibility to Vibrio colonization has significant implications for marine ecosystems and aquaculture, emphasizing the need for targeted monitoring and management strategies. Future research should focus on the long-term ecological impacts of climate change on Vibrio, the interactions between seaweed and Vibrio, and the resulting consequences on human health.

Author Contributions

SW conducted the experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the paper. MS conceptualised the idea, designed the project, contributed to funding, and editing the manuscript to the final version.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Plymouth Marine Laboratory and the Department of Science and Engineering, University of Plymouth. SW acknowledges Plymouth Marine Laboratory for hosting this project. SW thanks Dr. Sarah Bass from the University of Plymouth for guidance. This research was funded by the University of Plymouth. MS thanks the British Phycological Society and the Royal Society for partially funding the work.

References

- Akomea-Frempong, S., Skonberg, D. I., Arya, R., & Perry, J. J. (2023). Survival of Inoculated Vibrio spp., Shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp. on Seaweed (Sugar Kelp) During Storage. Journal of Food Protection, 86(7), 100096. [CrossRef]

- Akrong, M. O., Anning, A. K., Addico, G. N. D., Hogarh, J. N., Adu-Gyamfi, A., deGraft-Johnson, K. A. A., Ale, M., Ampofo, J. A., & Meyer, A. S. (2023). Variations in seaweed-associated and planktonic bacterial communities along the coast of Ghana. Marine Biology Research, 19(4–5), 219–233. [CrossRef]

- Amato, E., Riess, M., Thomas-Lopez, D., Linkevicius, M., Pitkänen, T., Wołkowicz, T., Rjabinina, J., Jernberg, C., Hjertqvist, M., MacDonald, E., Antony-Samy, J. K., Bjerre, K. D., Salmenlinna, S., Fuursted, K., Hansen, A., & Naseer, U. (2022). Epidemiological and microbiological investigation of a large increase in vibriosis, northern Europe, 2018. Eurosurveillance, 27(28).

- Baker-Austin, C., Oliver, J. D., Alam, M., Ali, A., Waldor, M. K., Qadri, F., & Martinez-Urtaza, J. (2018). Vibrio spp. infections. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2018 4:1, 4(1), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C., Trinanes, J. A., Taylor, N. G. H., Hartnell, R., Siitonen, A., & Martinez-Urtaza, J. (2013). Emerging Vibrio risk at high latitudes in response to ocean warming. Nature Climate Change 2012 3:1, 3(1), 73–77. [CrossRef]

- Barberi, O. N., Byron, C. J., Burkholder, K. M., St. Gelais, A. T., & Williams, A. K. (2020). Assessment of bacterial pathogens on edible macroalgae in coastal waters. Journal of Applied Phycology, 32(1), 683–696. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, K. D., & Oliver, J. D. (2008). The ecology of Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio cholerae, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus in North Carolina Estuaries. Journal of Microbiology, 46(2), 146–153. [CrossRef]

- Brumfield, K. D., Usmani, M., Chen, K. M., Gangwar, M., Jutla, A. S., Huq, A., & Colwell, R. R. (2021). Environmental parameters associated with incidence and transmission of pathogenic Vibrio spp. Environmental Microbiology, 23(12), 7314–7340. [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, A. H., Camus, C., Infante, J., Neori, A., Israel, Á., Hernández-González, M. C., Pereda, S. V., Gomez-Pinchetti, J. L., Golberg, A., Tadmor-Shalev, N., & Critchley, A. T. (2017). Seaweed production: overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity. European Journal of Phycology, 52(4), 391–406. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J. P. S. (2010). Water Microbiology. Bacterial Pathogens and Water. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2010, Vol. 7, Pages 3657-3703, 7(10), 3657–3703. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Lovatelli, A., Aguilar-Manjarrez, J., Cornish, L., Dabbadie, L., Desrochers, A., Diffey, Garrido Gamarro, E., Geehan, J., S., Hurtado, A., Lucenta, D., Mair, G. Miao, W, Potin, P., Przybyla, C., Reantaso, M., Roubach, R., Tauati, M., & Yuan, X. (2021). Seaweeds and microalgae: an overview for unlocking their potential in global aquaculture development. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular, (1229). [CrossRef]

- Chung, I. K., Sondak, C. F. A., & Beardall, J. (2017). The future of seaweed aquaculture in a rapidly changing world. European Journal of Phycology, 52(4), 495–505. [CrossRef]

- Coerdt, K. M., & Khachemoune, A. (2021). Vibrio vulnificus: Review of Mild to Life-threatening Skin Infections PRACTICE POINTS. Cutis, 107(2). [CrossRef]

- Craun, G.F. (1986). Waterborne disease. In Waterborne Diseases in the United States. CRC Press, Inc. BocaRaton, Florida, 3-10.

- Daniels, N. A., & Shafaie, A. (2000). A Review of Pathogenic Vibrio Infections for Clinicians. Infect Med, 17(10), 665–685.

- Del Olmo, A., Picon, A., Nuñez, M. (2018). The microbiota of eight species of dehydrated edible seaweeds from North West Spain. Food Microbiology, 70, 224-231. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.S., Tschoeke, D.A., Magalhães Lopes, A.C.R., Sudatti, D.B., Meirelles, P.M., Thompson, C.C., Pereira, R.C., Thompson, F.L. (2017). Molecular Mechanisms for Microbe Recognition and Defense by the Red Seaweed Laurencia dendroidea. mSphere, 2(6), https://doi.org/10.1128/mSphere.00094-17.Düsedau, L., Ren, Y., Hou, M., Wahl, M., Hu, Z. M., Wang, G., & Weinberger, F. (2023). Elevated Temperature-Induced Epimicrobiome Shifts in an Invasive Seaweed Gracilaria vermiculophylla. Microorganisms, 11(3), 599. [CrossRef]

- Egan, S., Harder, T., Burke, C., Steinberg, P., Kjelleberg, S., & Thomas, T. (2013). The seaweed holobiont: understanding seaweed–bacteria interactions. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 37(3), 462–476. [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, S., Herrig, I., Wesp, J., Stiedl, J., Reifferscheid, G., Strauch, E., Alter, T., & Brennholt, N. (2022). Prevalence and Distribution of Potentially Human Pathogenic Vibrio spp. on German North and Baltic Sea Coasts. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12, 846819. [CrossRef]

- Froelich, B. A., & Daines, D. A. (2020). In hot water: effects of climate change on Vibrio–human interactions. Environmental Microbiology, 22(10), 4101–4111. [CrossRef]

- Geisser, A.H., Scro, A.K., Smolowitz, R., & Fulweiler, R.W. (2025). Macroalgae host pathogenic Vibrio spp. In a temperate estuary. Frontiers in Marine Science, 12. [CrossRef]

- Goecke, F., Labes, A., Wiese, J., & Imhoff, J. F. (2010). Chemical interactions between marine macroalgae and bacteria. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 409, 267–299. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D. J., Gonzalez, R. A., Froelich, B. A., Oliver, J. D., Noble, R. T., & McGlathery, K. J. (2014). Non-native macroalga may increase concentrations of Vibrio bacteria on intertidal mudflats. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 505, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Griffis, R., & Howard, J. (Eds.). (2013). Oceans and marine resources in a changing climate: A technical input to the 2013 National Climate Assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Haley, B. J., Chen, A., Grim, C. J., Clark, P., Diaz, C. M., Taviani, E., Hasan, N. A., Sancomb, E., Elnemr, W. M., Islam, M. A., Huq, A., Colwell, R. R., & Benediktsdóttir, E. (2012). Vibrio cholerae in a historically cholera-free country. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 4(4), 381–389. [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2019) Summary for Policymakers. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3–35. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y., & Gao, K. (2021). Effects of climate change factors on marine macroalgae: A review. Advances in Marine Biology, 88, 91–136. [CrossRef]

- Kalvaitienė, G., Vaičiūtė, D., Bučas, M., Gyraitė, G., & Kataržytė, M. (2023). Macrophytes and their wrack as a habitat for faecal indicator bacteria and Vibrio in coastal marine environments. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 194, 115325. [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, C. W., & Tamplin, M. L. (1993). Effects of temperature and salinity on the survival of Vibrio vulnificus in seawater and shellfish. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 59(8), 2425–2429. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Stekoll, M., & Yarish, C. (2019). Opportunities, challenges and future directions of open-water seaweed aquaculture in the United States. Phycologia, 58(5), 446-461. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J. B., Van De Water, J. A. J. M., Bourne, D. G., Altier, C., Hein, M. Y., Fiorenza, E. A., Abu, N., Jompa, J., & Harvell, C. D. (2017). Seagrass ecosystems reduce exposure to bacterial pathogens of humans, fishes, and invertebrates. Science, 355(6326), 731–733. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C., Erken, M., Noorian, P., Sun, S., & McDougald, D. (2013). Environmental reservoirs and mechanisms of persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4(DEC), 70843. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, Z. H., Neogi, S. B., Kassu, A., Mai Huong, B. T., Jahid, I. K., Islam, M. S., & Ota, F. (2008). Occurrence, seasonality and genetic diversity of Vibrio vulnificus in coastal seaweeds and water along the Kii Channel, Japan. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 64(2), 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, Z. H., Neogi, S. B., Kassu, A., Wada, T., Islam, M. S., Nair, G. B., & Ota, F. (2007). Seaweeds as a reservoir for diverse Vibrio parahaemolyticus populations in Japan. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 118(1), 92–96. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K. L. E., Vogt, R. L., & Effler, P. (1998). Illness associated with eating seaweed, Hawaii, 1994. Western Journal of Medicine, 169(5), 293. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc1305326/.

- Meichssner, R., Stegmann, N., Cosin, A.S., Sachs, D., Bressan, M., Marx, H., Krost, P., & Rüdiger, S. (2020). Control of fouling in the aquaculture of Fucus vesiculosus and Fucus serratus by regular desiccation. Journal of Applied Phycology, 32, 4145-4158. [CrossRef]

- Mensch, B., Neulinger, S. C., Graiff, A., Pansch, A., Künzel, S., Fischer, M. A., & Schmitz, R. A. (2016). Restructuring of epibacterial communities on fucus vesiculosus forma mytili in response to elevated pco2 and increased temperature levels. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7(MAR), 180232. [CrossRef]

- Michotey, V., Blanfuné, A., Chevalier, C., Garel, M., Diaz, F., Berline, L., Le Grand, L., Armougom, F., Guasco, S., Ruitton, S., Changeux, T., Belloni, B., Blanchot, J., Ménard, F., & Thibaut, T. (2020). In situ observations and modelling revealed environmental factors favouring occurrence of Vibrio in microbiome of the pelagic Sargassum responsible for strandings. Science of The Total Environment, 748, 141216. [CrossRef]

- Nahor, O., Israel, Á., Barger, N., Rubin-Blum, M., & Luzzatto-Knaan, T. (2024). Epiphytic microbiome associated with intertidal seaweeds in the Mediterranean Sea: comparative analysis of bacterial communities across seaweed phyla. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1, 14(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Namadi, P., & Deng, Z. (2023). Optimum environmental conditions controlling prevalence of vibrio parahaemolyticus in marine environment. Marine Environmental Research, 183, 105828. [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü., Kahru, A., Mander, Ü., Nõges, P., Nõges, T., Tuvikene, A., & Vasemägi, A. (2017). Interacting environmental and chemical stresses under global change in temperate aquatic ecosystems: stress responses, adaptation, and scaling. Regional Environmental Change 2017 17:7, 17(7), 2061–2077. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. D. (2005). The Viable but Nonculturable State in Bacteria. Journal of Microbiology, 43(spc1), 93–100.

- Prakash, S. (2021). Impact of Climate change on Aquatic Ecosystem and its Biodiversity: An overview. International Journal of Biological Innovations, 3(2). [CrossRef]

- Pruzzo, C., Huq, A., Colwell, R. R., & Donelli, G. (2005). Pathogenic Vibrio Species in the Marine and Estuarine Environment. Oceans and Health: Pathogens in the Marine Environment, 217–252. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y., Jia, R., Luo, Y., & Feng, L. (2021). The inhibitory effect of Ulva fasciata on culturability, motility, and biofilm formation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus ATCC17802. International Microbiology, 24, 301-310. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Castillo, F. Y., Loera-Muro, A., Jacques, M., Garneau, P., Avelar-González, F. J., Harel, J., & Guerrero-Barrera, A. L. (2015). Waterborne pathogens: detection methods and challenges. Pathogens, 4(2), 307–334. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, G. D., Reilly, C. A., Smith, E. G., & Baker-Austin, C. (2011). Vibrio alginolyticus-associated wound infection acquired in British waters, Guernsey, July 2011. Eurosurveillance, 16(42), 3. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L., Fraschetti, S., Alifano, P., Tredici, M. S., & Stabili, L. (2016). Association of Vibrio community with the Atlantic Mediterranean invasive alga Caulerpa cylindracea. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 475, 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A., Silva, V., Poeta, P., & Aonofriesei, F. (2022). Vibrio spp.: Life Strategies, Ecology, and Risks in a Changing Environment. Diversity 2022, Vol. 14, Page 97, 14(2), 97. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R., & Saha, M. (2021). Infochemicals in terrestrial plants and seaweed holobionts: current and future trends. New Phytologist, 229(4), 1852–1860. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. P., & Reddy, C. R. K. (2014). Seaweed–microbial interactions: key functions of seaweed-associated bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 88(2), 213–230. [CrossRef]

- Takemura, A. F., Chien, D. M., & Polz, M. F. (2014). Associations and dynamics of vibrionaceae in the environment, from the genus to the population level. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5(FEB), 75606. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, F. L., Iida, T., & Swings, J. (2004). Biodiversity of Vibrios. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 68(3), 403–431. [CrossRef]

- Trinanes, J., & Martinez-Urtaza, J. (2021). Future scenarios of risk of Vibrio infections in a warming planet: a global mapping study. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(7), e426–e435. [CrossRef]

- Tuhumury, N. C., Sahetapy, J. M. F., & Matakupan, J. (2024). Isolation and identification of bacterial pathogens causing ice-ice disease in Eucheuma cottonii seaweed at Seira Island Waters, Tanimbar Islands District, Maluku, Indonesia. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity, 25(3), 964–970. [CrossRef]

- Vandenkoornhuyse, P., Quaiser, A., Duhamel, M., Le Van, A., & Dufresne, A. (2015). The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytologist, 206(4), 1196–1206. [CrossRef]

- Vezzulli, L., Baker-Austin, C., Kirschner, A., Pruzzo, C., & Martinez-Urtaza, J. (2020). Global emergence of environmental non-O1/O139 Vibrio cholerae infections linked with climate change: a neglected research field? Environmental Microbiology, 22(10), 4342–4355. [CrossRef]

- Vezzulli, L., Colwell, R. R., & Pruzzo, C. (2013). Ocean Warming and Spread of Pathogenic Vibrios in the Aquatic Environment. Microbial Ecology, 65(4), 817–825. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, M., Goecke, F., Labes, A., Dobretsov, S., & Weinberger, F. (2012). The second skin: Ecological role of epibiotic biofilms on marine organisms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 3(AUG), 31139. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., Shuai, L., Li, Y., Lin, W., Zhao, X., & Duan, D. (2008). Phylogenetic analysis of epiphytic marine bacteria on Hole-Rotten diseased sporophytes of Laminaria japonica. Journal of Applied Phycology, 20(4), 403–409. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, L. G. E., Leray, M., O’Dea, A., Yuen, B., Peixoto, R. S., Pereira, T. J., Bik, H. M., Coil, D. A., Duffy, J. E., Herre, E. A., Lessios, H. A., Lucey, N. M., Mejia, L. C., Rasher, D. B., Sharp, K. H., Sogin, E. M., Thacker, R. W., Thurber, R. V., Wcislo, W. T., … Eisen, J. A. (2019). Host-associated microbiomes drive structure and function of marine ecosystems. PLOS Biology, 17(11), e3000533.

- Ziino, G., Nibali, V., & Panebianco, A. (2010). Bacteriological investigation on ‘Mauro’ sold in Catania. Veterinary Research Communications, 34(SUPPL.1), 157–161. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).