1. Introduction

Feline calicivirus disease, feline viral rhinotracheitis, and feline panleukopenia represent three prevalent infectious ailments in cats, stemming from feline calicivirus (FCV), feline herpesvirus type 1 (FHV-1), and feline panleukopenia virus (FPV), respectively. FCV, categorized under the Vesivirus genus within the Caliciviridae family, is a single-stranded, positive-sense, non-enveloped RNA virus. Its high contagiousness can trigger sporadic outbreaks of upper respiratory tract diseases (URTD) and virulent systemic diseases (FCV-VSD) in cats, accompanied by a significant mortality rate [

1]. FHV-1, belonging to the Varicellovirus genus of the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily in the Herpesviridae family, stands as a primary pathogen causing upper respiratory tract infections. It spreads primarily via direct contact, contaminated objects, and droplets, leading to infectious rhinotracheitis in cats with high morbidity and mortality rates [

2]. FPV, a member of the Protoparvovirus genus in the Parvoviridae family, causes a common acute and often fatal illness in cats, characterized by severe diarrhea, vomiting, nasal discharge, and profound leukopenia [

3].

The feline trivalent vaccine, officially titled "Feline Panleukopenia, Rhinotracheitis, and Calicivirus Trivalent Vaccine," is a multivalent formulation tailored for these three feline infectious diseases. It typically comes in inactivated or attenuated live forms. However, current practical applications of this vaccine exhibit certain limitations. The substantial antigenic variation among FCV strains limits the effectiveness of available vaccines against all strains, rendering suboptimal protection and insufficient to prevent infections by virulent wild strains or viral transmission among cats [

4]. The current FHV-1 vaccine offers limited and short-lived protection, as the virus's immune evasion tactics and multiple interferon response effectors often undermine vaccination efficacy [

5,

6]. Additionally, studies indicate potential immune evasion by FPV, with FPV-251 demonstrating high virulence and immune evasion potential when confronted with serum from cats immunized with China's only commercial vaccine (Feline Rhinotracheitis-Calicivirus-Panleukopenia Vaccine, inactivated virus) [

7,

8].

Adjuvants, comprising various molecules and materials, play a pivotal role in vaccine development by enhancing immune efficacy through prolonged antigen retention and sustained release, lymph node targeting, and dendritic cell activation modulation [

9]. Manganese, a crucial trace element for immune regulation among other physiological processes, emerges as a novel adjuvant candidate. Research shows Mn²⁺ can bolster immune responses by activating the cGAS-STING and NLRP3 pathways, thereby enhancing antigen uptake, presentation, and germinal center formation [

10,

11]. However, manganese adjuvant use entails potential toxicity risks and inconsistent immune efficacy [

11]. Traditional aluminum adjuvants, though widespread, often fail to elicit robust cellular immunity and may induce localized inflammation, making them less optimal for feline trivalent vaccines. Hence, safer and more effective immunological adjuvants are urgently needed in vaccine production.

Cytokines and metabolic regulatory molecules are indispensable for immune regulation. Cytokines like IL-15 exhibit multiple immunomodulatory activities, fostering the survival, proliferation, and activation of NK cells, B cells, and T cells [

12]. IL-23 augments the immune response by promoting the expansion and survival of the Th17 subset of helper T cells [

13]. Preliminary studies demonstrate that IL-15 and IL-23, when expressed as fusion proteins, significantly enhance mucosal immunity and systemic immune responses [

14]. Numerous studies affirm that β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), N-acetylcysteine (N-Ace), L-carnitine, sodium butyrate, and tryptophan can impact immune efficacy by modulating immune cell activity and mitigating inflammatory responses [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

To assess the adjuvant potential of these molecules, this study incorporated feline IL-15, IL-23, and a suite of metabolic regulators as a composite adjuvant, administered alongside trivalent vaccine antigens in mice. The aim was to evaluate whether this formulation could elevate vaccine immunogenicity and protective efficacy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Grouping and Immunization Protocol

Forty female Kunming mice aged 6 weeks were randomly divided into four groups, with 10 mice in each group. Each group received subcutaneous dorsal immunization according to the protocol outlined in

Table 1, followed by a booster immunization at week 3.

The trivalent feline vaccine antigens used in this experiment (107.0 TC5ID0 per dose of WH-2017 strain + 107.5 TCID50 per dose of LZ-2016 strain + 105.5 TCID50 per dose of CS-2016 strain) and the commercial vaccine "Maokangning" were provided by Sichuan Huapai Biotech (Group) Co., Ltd.

2.2. Sample and Data Collection

2.2.1. Body Weight Measurements

Mice in each group were weighed once a week for eight consecutive weeks to record the dynamic changes in body weight of the mice in each group.

2.2.2. Blood Immune Parameters

Venous anticoagulated blood samples (200 µL per mouse) were collected from each group of mice weekly using the tail snip method.

2.2.3. Lymphocyte Subsets

On Day 56 after the first immunization, mice were euthanized, and their spleens were removed to prepare lymphocyte suspensions. The number of lymphocyte subsets was detected and analyzed.

2.3. Neutralizing/Antigen-Specific Antibody Detection

2.3.1. Detection of Feline Trivalent Neutralizing Antibody Levels by Fixed Virus Dilution of Serum

Neutralizing antibody levels were tested before the first immunization and on Days 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 after the first immunization. Feline calicivirus diluted to 100 TCID50 per unit dose was mixed with an equal volume of two-fold serially diluted test serum and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. Each dilution was inoculated into 3–6 wells of cells. After inoculation, the number of wells showing cytopathic effects (CPE) in each group was recorded. The median protective dose (PD50) for each group was calculated using the Reed-Muench method, and the serum neutralizing titer was then determined [

22].

2.3.2. In Vitro Detection of Feline Trivalent Antigen-Specific Antibodies

Specific antibody levels were tested in vitro before the first immunization and on Days 7, 28, 42, and 56 after the first immunization. The levels of feline herpesvirus antibodies (FHV-Ab) and feline parvovirus antibodies (FPV-Ab) in mouse plasma were measured in vitro according to the instructions for the Feline Trivalent Antibody Detection Kit (fluorescent immunochromatography, catalog number PRG108, Shanghai Glinx Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) [

23].

2.4. Immune Cell Count in Blood

Complete blood count (CBC) analysis was performed on blood samples from each group before the first immunization and on Days 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 after the first immunization. A 50 µL sample of whole blood containing EDTA anticoagulant was taken from each group and analyzed using the veterinary fully automated five-part differential blood analyzer (TEK-VET5) manufactured by Tekon Biotechnology Co., Ltd., according to the operating procedures.

2.5. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Immune Cells

2.5.1. Analysis of Immune Cells in Blood

Flow cytometry was used to detect changes in immune cells in blood samples from each group of mice on Days 28, 42, and 56 after the first immunization.

Firstly, 1 µl of each of the following flow cytometry antibodies was added to a 1.5 ml EP tube containing 100 µl of mouse peripheral anticoagulated blood (with EDTA·2K anticoagulant): anti-mouse CD45 (CD45 Monoclonal Antibody (30-F11), Super Bright™ 600, eBioscience™), CD3 (BD Pharmingen™ FITC Hamster Anti-Mouse CD3e), CD4 (CD4 Monoclonal Antibody (GK1.5), eFluor™ 450, eBioscience™), CD8 (CD8a Monoclonal Antibody (53-6.7), PerCP-Cyanine5.5, eBioscience™), CD44 (CD44 Monoclonal Antibody (IM7), APC, eBioscience™), and CD62L (CD62L (L-Selectin) Monoclonal Antibody (MEL-14), PE, eBioscience™). The mixture was incubated at 4°C in the dark for 30 minutes. Then, 1 ml of 1×RBC lysis buffer (prepared with deionized water) was added to the reaction system. After lysis at room temperature for 5 minutes, the mixture was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was removed to obtain the cell pellet. Subsequently, 200 µl of PBS (with 0.5% BSA) was added to the cell pellet, mixed by pipetting, and then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C to remove the supernatant. This washing process was repeated twice. Finally, the washed cells were resuspended in 500 µl of PBS (with 0.5% BSA), fixed with a final volume of 2% paraformaldehyde, and stored in the dark at 4°C for subsequent detection.

At the same time, the same treatment was performed according to the following staining scheme: 1 µl of each of the following flow cytometry antibodies was added to tube 2: anti-mouse CD45 (CD45 Monoclonal Antibody (30-F11), Super Bright™ 600, eBioscience™), CD3 (BD Pharmingen™ FITC Hamster Anti-Mouse CD3e), CD4 (CD4 Monoclonal Antibody (GK1.5), eFluor™ 450, eBioscience™), CD69 (CD69 Monoclonal Antibody (H1.2F3), PE, eBioscience™), and CD103 (CD103 (Integrin alpha E) Monoclonal Antibody (2E7), APC, eBioscience™); 1 µl of each of the following flow cytometry antibodies was added to tube 3: anti-mouse CD19 (CD19 BUV395), IgM (IgM APC), and IgD (IgD FITC).

2.5.2. Analysis of Immune Cells in Splenic Single-Cell Suspension

After the mice were euthanized, and their spleen was placed on a 70 µm cell strainer, which was then placed in a 6 cm dish. 3 ml PBS (with 0.5% BSA) was added, and the spleens were ground directly on the 70 µm cell strainer using the plunger of a 2 ml syringe. After grinding, the cell strainer was rinsed with 2 ml of PBS (with 0.5% BSA). Then, the splenic cell suspension was transferred to a 15 ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was removed. 3 ml 1×RBC lysis buffer was added, and the mixture was vortexed and mixed, lysed at room temperature for 5 minutes, and then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. After removing the supernatant, 3 ml of PBS (with 0.5% BSA) was added, vortexed and mixed, and the 70 µm cell strainer was placed on a 50 ml centrifuge tube to filter the splenic cells again. The filtered cells were collected in a 50 ml centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was removed. The cells were washed once with PBS containing BSA and then once with PBS without BSA. 1 ml PBS (with 0.5% BSA) was then added to resuspend the cells, vortexed and mixed, and connective tissue was removed with a pipette. The preparation of the splenic single-cell suspension was then complete. 50 ml PBS (with 0.5% BSA) were used to resuspend the splenic cells. The mixture was incubated at 4°C for 10 minutes, and surface marker antibody incubation started without washing. Finally, staining was performed according to the color scheme in

Section 2.5.1, and the mixture was incubated in the dark on ice for 30 minutes. After washing twice, 200 µl of 4% paraformaldehyde was added to fix at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes. The cells were then washed once and resuspended to 200 µl for subsequent detection.

2.5.3. Gating Strategy

T cells were defined as the CD3+/CD45+ population. Based on the differential expression of CD4 and CD8, T cells could be further divided into four major subpopulations: CD4+ TH cells, CD8+ TC cells, CD4+/CD8+ double-positive (DP) cells, and CD4-/CD8- double-negative (DN) cells. The latter are mainly composed of γδ+ cells under normal conditions. When analyzing CD44 and CD62L in TH and TC lymphocytes, three different subpopulations could be distinguished: tissue-resident memory T cells, effector memory T (EM) cells, and central memory T cells.

Referring to the blood flow cytometry sample preparation method (see

Section 2.5.1), 1 µl of each of the following flow cytometry antibodies was added to the tube: anti-mouse CD19 (CD19 BUV395, BD), IgM (IgM APC, ThermoFisher, 17-5790-82), and IgD (IgD FITC, ThermoFisher, 11-5993-85). B cells were defined as the CD19+ population. When analyzing IgM and IgD in B cells, four different subpopulations could be distinguished: class-switched or activated B cells (IgM-, IgD-), transitional B cells (IgM+, IgD-), marginal zone B cells (IgM+, IgD+), and naïve follicular B cells (IgM-, IgD+).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. Data from each group were expressed as the mean±SD of triplicates. Differences among the groups were analyzed using two-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

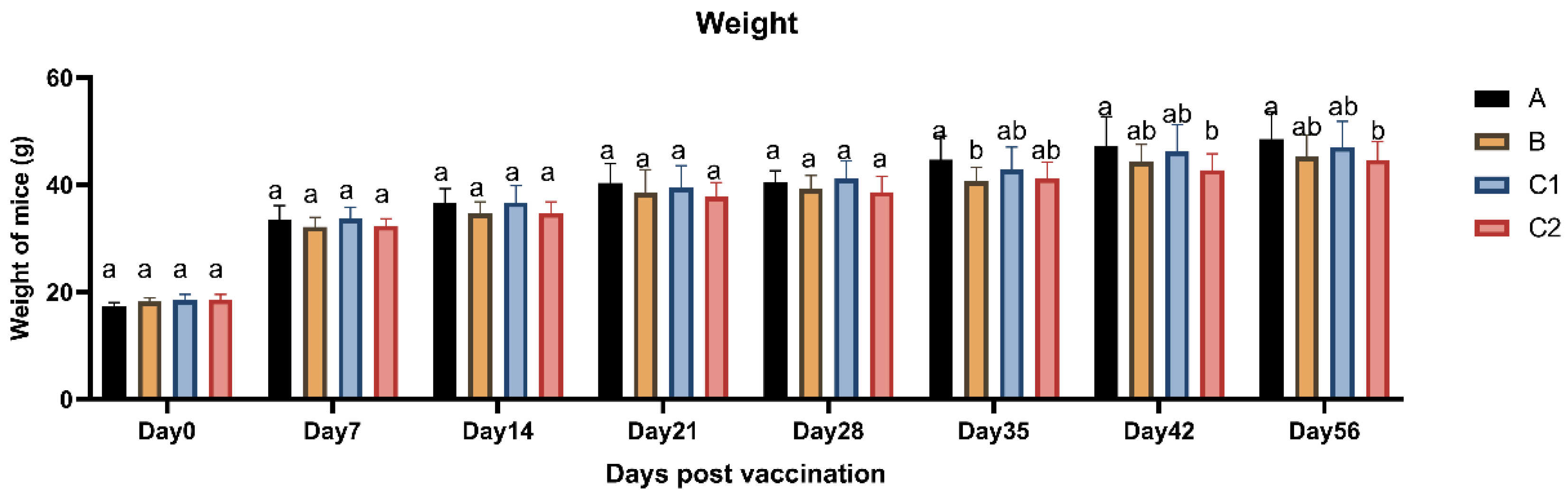

3.1. Weight Changes

Figure 1 displays the body weight measurements of mice in Groups A, B, C1, and C2 following vaccination. The average body weights across all groups showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) at any of the eight time points, with all groups demonstrating a gradual increasing trend over time. These findings indicate that the vaccine adjuvants did not induce significant alterations in body weight, thereby confirming the biological safety of the immunological adjuvants.

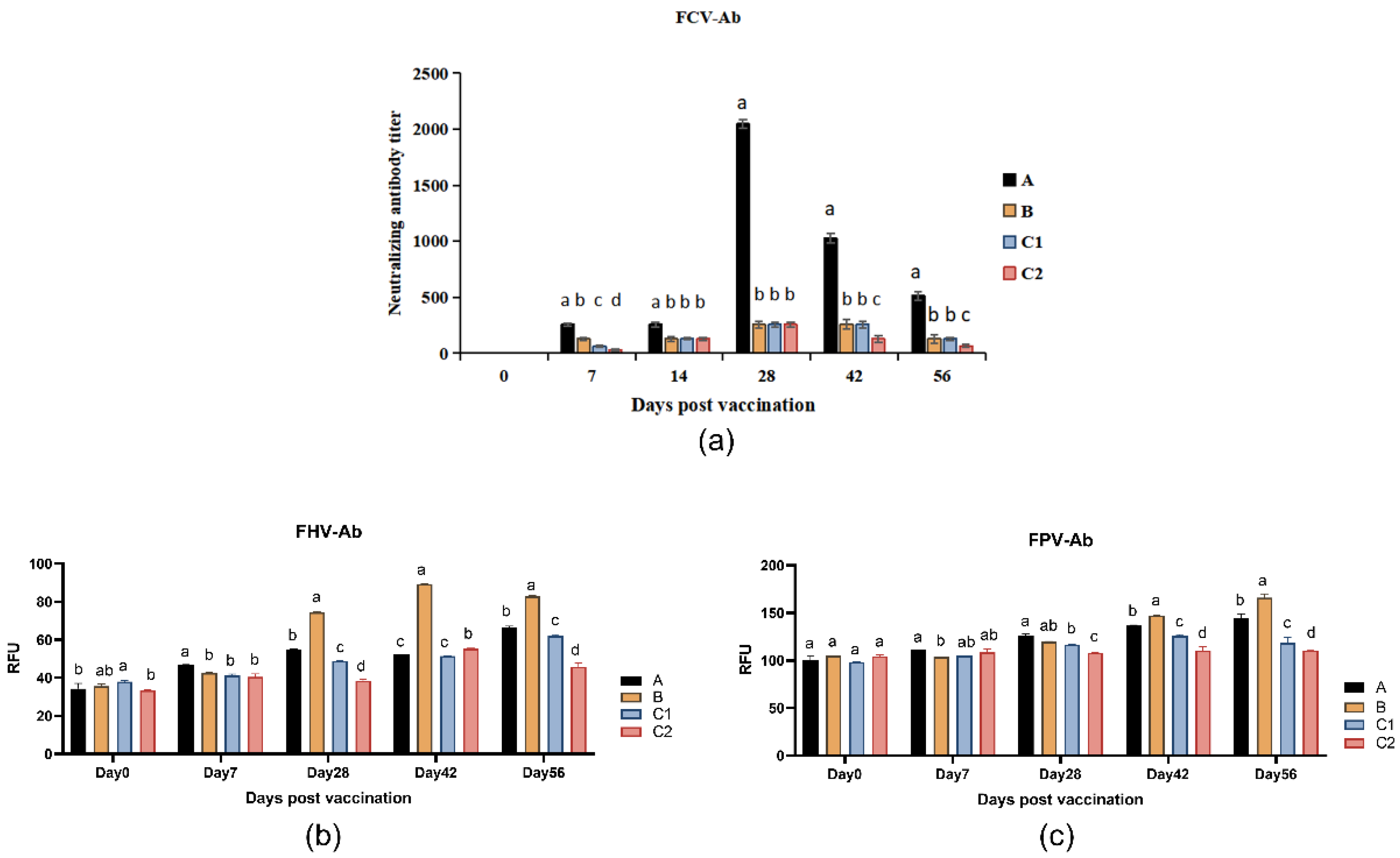

3.2. Neutralizing/Antigen-Specific Antibody Detection

Figure 2a presents the neutralizing antibody titers against FCV in the group A, B, C1, and C2 at days 0, 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 post-immunization. On day 7 after primary immunization, Group A and B showed significantly lower FCV neutralizing antibody titers compared to Group C1 (P < 0.05). By day 14, Group A maintained stable antibody levels, whereas Groups C1 and C2 exhibited significant declines. Following booster immunization (day 21), Group A demonstrated significantly higher FCV neutralizing antibody levels than the other three groups at all subsequent time points (P < 0.05).

Figure 2b,c display the FHV-Ab and FPV-Ab levels, respectively, measured at days 0, 7, 28, 42, and 56. As shown in

Figure 2b, Group A maintained higher FHV-Ab levels than Group C2 on days 28, 42, and 56 post-primary immunization (P < 0.05), while Group B showed significantly elevated FHV-Ab levels compared to all other groups (P < 0.05). Both Groups A and B exhibited marked increases in specific antibody levels following secondary immunization (day 21).

Figure 2c reveals that Groups A and B displayed progressively increasing FPV-Ab levels, with significantly higher titers than Groups C1 and C2 on days 42 and 56 (P < 0.05). Notably, by day 56, both Groups A and B achieved substantially enhanced FPV-Ab levels compared to pre-booster measurements.

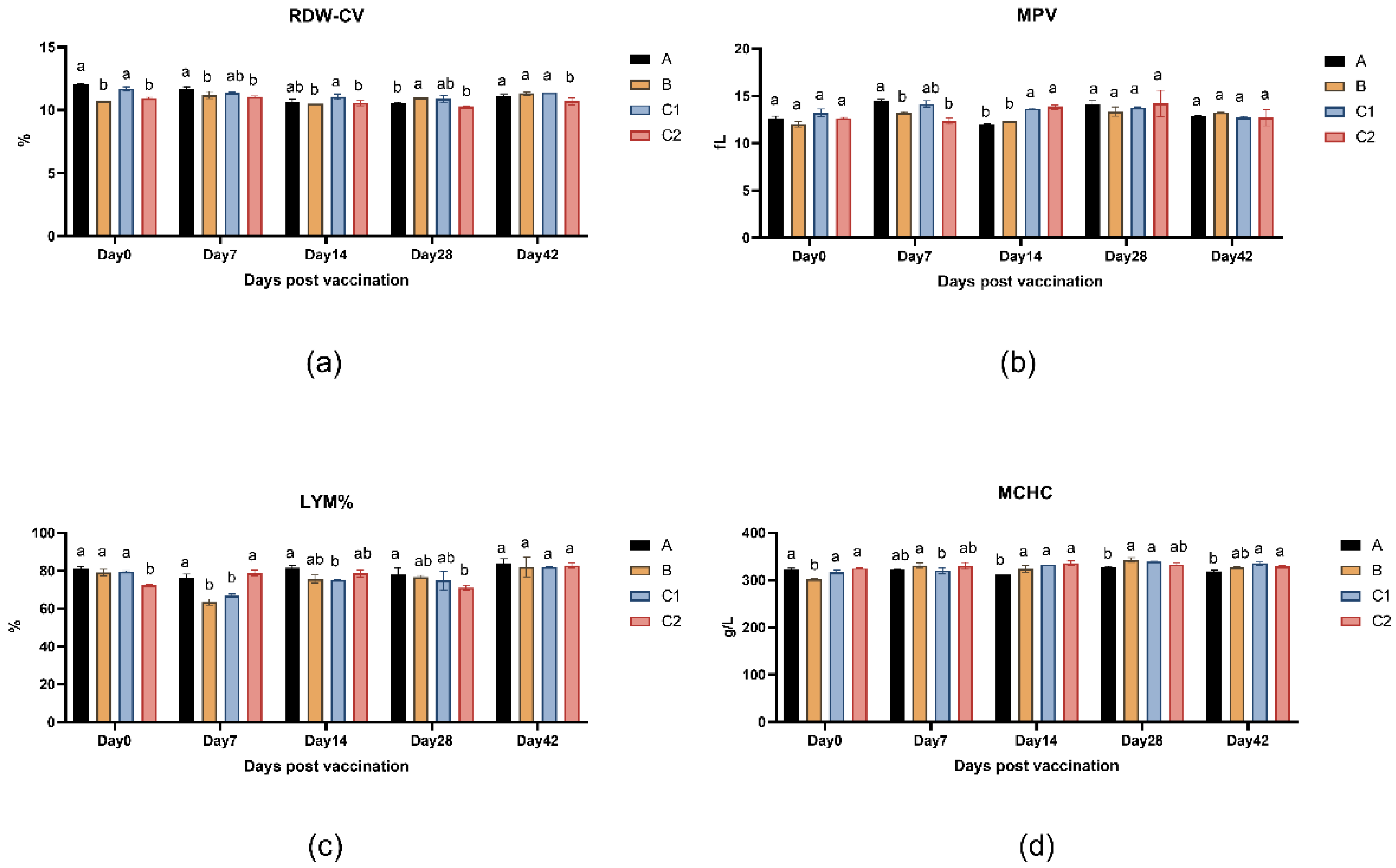

3.3. Blood Cells Analysis

Figure 3a-d presents the peripheral blood parameters of mice across measurement time points, including red cell distribution width (RDW-CV), mean platelet volume (MPV), lymphocyte percentage (LYM%), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). The data demonstrates no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) in these hematological indices among Groups A, B, C1, and C2 at any time point (days 0, 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56), indicating that the adjuvants did not significantly affect murine hematological parameters.

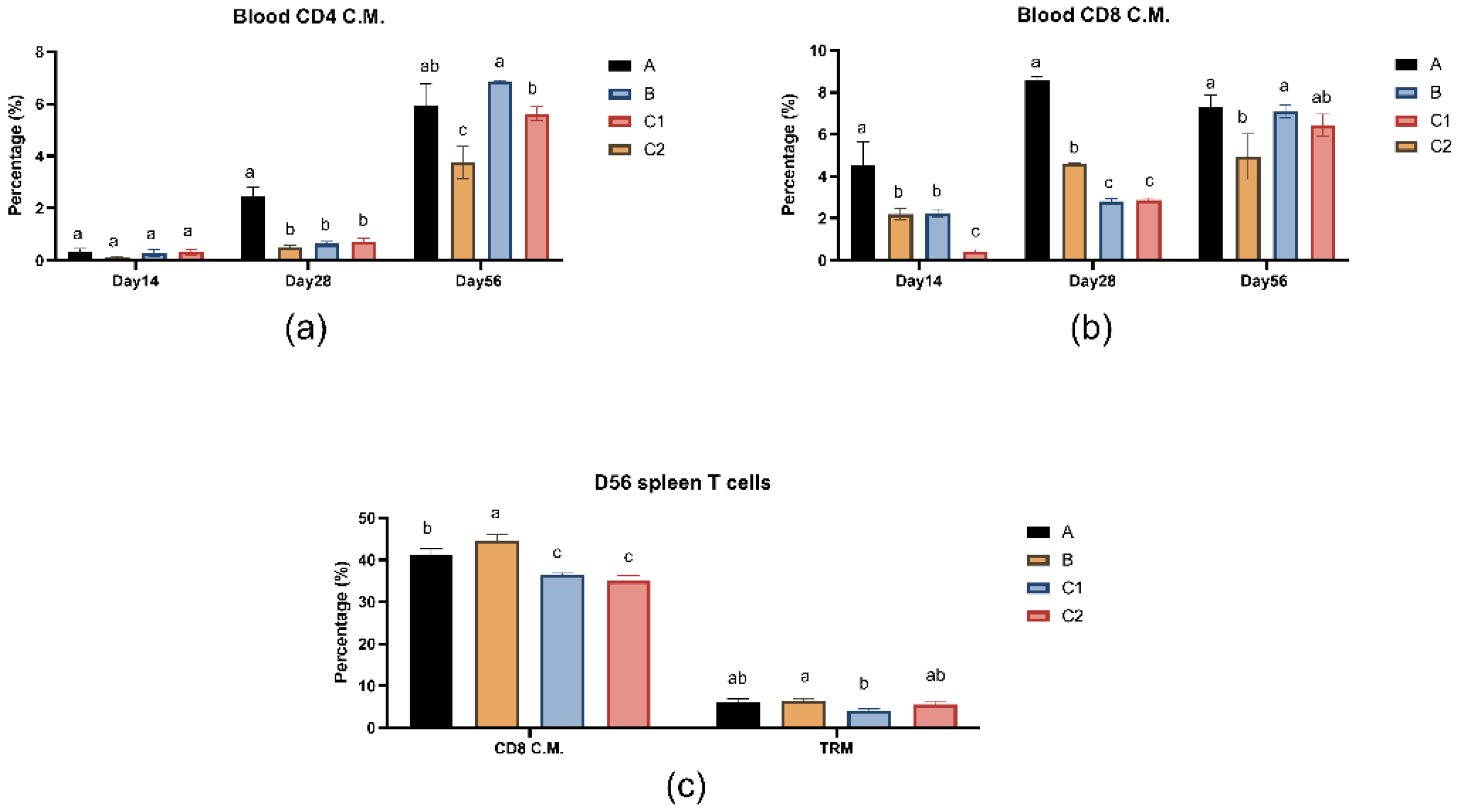

3.4. Flow Cytometry of Immune Cells

Figure 4a and b show the percentages of CD4 effector memory T lymphocytes and CD8 effector memory T lymphocytes in peripheral blood of mice in groups A, B, C1 and C2 on days 14, 28 and 56.

Figure 4c shows the percentage of T lymphocyte subset immunity in spleen of mice in groups A, B, C1 and C2 on day 56. In the blood T cell analysis on day 28, Group A demonstrated significantly higher percentages of both CD4+ and CD8+ central memory T cells (TCM) compared to the other three groups (P < 0.05), while no significant differences were observed versus Group C2 by day 56 (P > 0.05). In splenic T cell analysis on day 56, the percentages of CD8 central memory T cells in groups A and B were significantly higher than those in groups C1 and C2 (P<0.05), while there was no significant difference in tissue-resident memory T cell levels between groups A/B and group C2 (P>0.05).

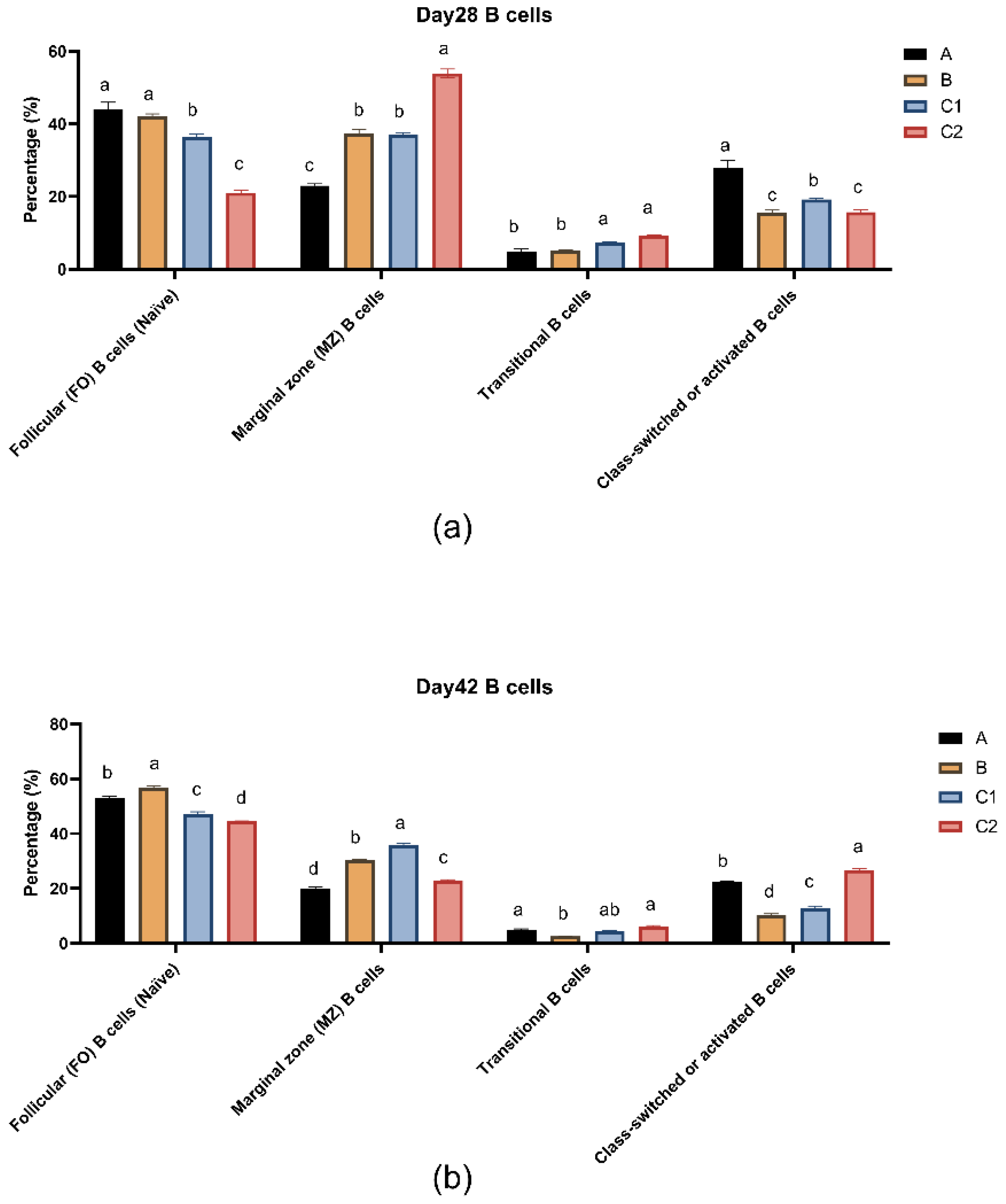

Figure 5a,b show the percentages of B lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood of mice in groups A, B, C1 and C2 at day 28 and day 42. At both measurement time points, transitional B cells (IgM+, IgD-) were present in low amounts in all groups. The follicular B cells (IgM-, IgD+) and activated B cells (IgM-, IgD-) in groups A and B were significantly higher than those in groups C1 and C2 (P<0.05). Moreover, the level of transitional B cells (IgM+, IgD-) at day 56 decreased compared to day 28. At day 28, the activated B cell level in group A was significantly higher than that in the other three groups (P<0.05).

4. Discussion

In recent decades, commercial vaccines for cats have exhibited suboptimal efficacy [

24,

25]. Vaccines targeting FCV and FHV may show waning immunity over time, necessitating periodic booster vaccinations to sustain protective effects [

26]. Conversely, immune adjuvants can augment vaccine immunogenicity and durability by prolonging antigen retention and fostering immune cell activation. To date, no studies have explored Mn, cytokines, or metabolic modulators as adjuvants in feline vaccines. Although aluminum adjuvants have proven moderately effective and are widely used, they are unable to elicit robust cellular immune responses and may induce localized inflammatory reactions [

27], rendering them unsuitable for feline vaccine formulations. Mn possesses stable chemical properties and can establish an immunostimulatory microenvironment [

10]. In a rabies vaccine study, manganese jelly (MnJ) significantly increased the production of various immune cells [

28]. However, the immunomodulatory effects of Mn are constrained by specific immune microenvironments [

29]. Furthermore, improper dosage control may lead to gradual Mn accumulation in the body upon repeated administration, potentially causing neurotoxicity and reproductive toxicity.

In contrast, cytokines and metabolic regulatory molecules offer significant advantages as novel immune adjuvants. Cytokines can enhance immune responses while mitigating adverse effects [

30,

31]. In this study, IL-15 and IL-23 were selected as two representative cytokines with crucial immunomodulatory functions. Research indicates that IL-15 regulates the generation and maintenance of memory T cells, enhances cytotoxic activity, and promotes cytokine production [

32]. Given its role in memory T cell development and persistence, IL-15 has been incorporated as a vaccine adjuvant for infectious diseases [

33]. IL-23 can amplify immune potency by promoting the expansion of tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells [

34,

35]. Moreover, in vitro studies have shown that the combined use of IL-15 and IL-23 effectively facilitates the generation of CD8⁺ central memory T cells [

36].

Metabolic regulatory molecules, as endogenous compounds, can also enhance immune efficacy while reducing adverse reactions such as inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and its precursor β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) enhance macrophage phagocytic capacity and suppress inflammatory reactions [

16,

21]. N-acetylcysteine (NAC), one of the most extensively studied antioxidant agents [

18], modulates immune function by regulating T cell subsets and upregulating the ability of dendritic cells to activate T cells, thereby increasing CD8⁺ T cell frequency and promoting memory T cell expansion [

20]. L-carnitine enhances immune efficacy by boosting immune cell activity and attenuating inflammatory responses [

19]. Additionally, sodium butyrate and serine can substantially influence immunity by modulating immune cell function and the production of immunologically active substances [

15,

17].

This study evaluated the biosafety of immune adjuvants by examining body weight and hematological parameters in experimental mice. The results revealed no significant differences in body weight among groups at any measured time point, with all groups exhibiting a stable upward trend in weight gain. This suggests that the adjuvants did not exert any adverse effects on the growth and development of the mice. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in peripheral blood hematological parameters across the four groups, indicating that IL-15, IL-23, and related metabolic molecules did not negatively impact the hematopoietic system or blood composition, further confirming the biosafety of the adjuvants.

CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cell memory play a pivotal role in combating infectious diseases. Upon encountering foreign antigens, naïve CD8⁺ T cells proliferate and differentiate into effector CD8⁺ T cells, subsequently leaving behind a stable population of CD8⁺ memory T cells after infection resolution [

37]. CD4⁺ T cells indirectly participate in immune responses by modulating the activity of other immune cells, whereas CD8⁺ T cells directly mediate cytotoxic effects to eliminate virus-infected cells. Central memory T cells (TCM) can persist long-term in the body and mount rapid responses upon re-exposure to the same antigen, thereby providing long-term immunity. The results demonstrated that Group A exhibited a significant increase in blood T cell levels after secondary immunization, with no significant difference compared to Group C2 by day 56, while remaining significantly higher than Group B. This indicates that Group A enhanced the immune response in mice post-booster immunization while maintaining a protective efficacy comparable to that of commercially available vaccines. On day 56, the percentages of splenic CD8⁺ TCM cells in Groups A and B were significantly higher than those in Groups C1 and C2. These findings suggest that IL-15 and IL-23 promote the expansion of tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) and TCM, while the metabolic molecules contribute to elevated CD8⁺ T cell levels and facilitate the formation of memory T cells.

For B cell subsets, upon activation, follicular (FO) B cells enter the germinal center and ultimately differentiate into plasma cells or memory B cells [

38]. Activated B cells signify the maturation of the immune response, and a subset of them further differentiates into memory B cells, which persist long-term in the body and mount rapid responses during secondary immune reactions [

39]. Appropriate NAD⁺ levels help maintain normal B cell function, promoting their differentiation into plasma cells for antibody production. Meanwhile, NMN supplementation may enhance B cell immune responses by elevating NAD⁺ levels [

39]. Experimental data demonstrate that Groups A and B, supplemented with metabolic regulators and cytokines, exhibited significant B cell differentiation characteristics: a reduced proportion of transitional B cells and a notably higher proportion of FO B cells compared to the control group. The addition of cytokines IL-15/23 may have facilitated the differentiation of transitional B cells into FO B cells, laying the foundation for the immune system to produce more high-affinity antibodies against antigens. The percentage of marginal zone (MZ) B cells in Groups A and B was lower than in Group C1, suggesting that the adjuvants in Groups A and B may have activated MZ B cells, driving their differentiation into plasma cells or other subsets [

40]. Furthermore, Group A displayed the highest percentage of activated B cells on day 28, indicating that more activated B cells would subsequently differentiate into plasma cells and memory B cells, thereby enhancing antibody production and long-term immunity.

The neutralizing antibody titer is closely associated with vaccine protective efficacy. The level of neutralizing antibodies in Group A was significantly higher than those in other groups after booster immunization, indicating that the adjuvants IL-15/23 significantly enhanced the immune response. The concentrations of FHV and FPV neutralizing antibodies were below the detection limit; therefore, we further evaluated the immunization efficacy by measuring virus-specific antibodies against the three viruses. The FHV-Ab measurement results demonstrated that the specific antibodies in Group B increased significantly after booster immunization and exhibited an upward trend. On day 56, the FHV-Ab level in Group B was significantly higher than those in the other three groups, suggesting that the cellular metabolic molecules could markedly and persistently enhance immune efficacy. After day 28, the FPV-specific antibody levels in Groups A and B were consistently higher than those in Groups C1 and C2, indicating that the metabolic regulators could more effectively promote the production of FPV-specific antibodies post-booster immunization. These results demonstrate that the combination of metabolic modulators and cytokines as adjuvants can optimize B-cell immune responses through multiple pathways, significantly improving antibody production efficiency and establishing long-term immune memory.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that feline IL-15, feline IL-23, and a series of metabolic regulatory molecules, when used as immunological adjuvants for the feline trivalent vaccine, exhibit a certain level of safety. During the immune response process, these adjuvants effectively promote the generation and differentiation of immune cells, while also enhancing the production of antibodies. This finding indicates that the aforementioned composite adjuvant can serve as an effective immune enhancer for the feline trivalent vaccine, providing a new potential strategy and theoretical basis for optimizing the immunological efficacy of the feline trivalent vaccine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W. and J.P.; methodology, J.P.; D.Z.; W.S.; D.H.; software, D.Z.; validation, D.Z., W.S., and R.G.; formal analysis, D.Z.; R.G.; M.L.; J.P.; M.L.; D.H.; L.Z.;Y.W.; investigation, D.Z.; J.P.; M.L.; D.H.; L.Z.; Y.W.; resources, P.J. and G.W.; data curation, D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; writing—review and editing, G.W.; visualization, D.Z.; supervision, P.J. & G.W.; project administration, P.J. & G.W.; funding acquisition, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the key project from the Sichuan Province of China (2020YFH0020, 2021YFYZ0030), the key project of Sichuan Sanyoukang Corp. (23H1442).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Animal Experiment Center of Sichuan University (Approval code SYXK-Chuan-2019-172, Approval Date: 16 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We enjoy the sincere help of Deyan Du, Sichuan Huapai Biotechnology (Group) Co. Ltd, to conduct the neutralization test of FCV antibody.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Bordicchia, M.; Fumian, T.M.; Van Brussel, K.; Russo, A.G.; Carrai, M.; Le, S.J.; Pesavento, P.A.; Holmes, E.C.; Martella, V.; White, P.; Beatty, J.A.; Shi, M.; Barrs, V.R. Feline Calicivirus Virulent Systemic Disease: Clinical Epidemiology, Analysis of Viral Isolates and In Vitro Efficacy of Novel Antivirals in Australian Outbreaks. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Huang, S.; Lu, Y.; Su, Y.; Guo, L.; Guo, L.; Xie, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Chai, H.; Wang, Y. Cross-species transmission of feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1) to chinchillas. Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 2532–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Q.; Alam, S.; Chowdhury, M.S.R.; Hasan, M.; Uddin, M.B.; Hossain, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. First molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the VP2 gene of feline panleukopenia virus in Bangladesh. Arch Virol 2021, 166, 2273–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.J.; Hartmann, K.; Egberink, H.; Truyen, U.; Tasker, S.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Frymus, T. Lloret, A.J.V. Calicivirus infection in cats. 2022, 14, 937.

- Capozza, P.; Pratelli, A.; Camero, M.; Lanave, G.; Greco, G.; Pellegrini, F.; Tempesta, M. Feline Coronavirus and Alpha-Herpesvirus Infections: Innate Immune Response and Immune Escape Mechanisms. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Qiao, P.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Huo, N.; Ding, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Xi, X. Liu, Y.J.F.i.V.S. Cellular and humoral immune responses in cats vaccinated with feline herpesvirus 1 modified live virus vaccine. 2025, 11, 1516850.

- Li, J.; Zeng, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yan, Q.; Li, Q.; Cao, S.; Zhou, D. Assessing immune evasion potential and vaccine suitability of a feline panleukopenia virus strain. Veterinary Vaccine 2024, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucciarone, C.M.; Franzo, G.; Legnardi, M.; Lazzaro, E.; Zoia, A.; Petini, M.; Furlanello, T.; Caldin, M.; Cecchinato, M.; Drigo, M. Genetic Insights into Feline Parvovirus: Evaluation of Viral Evolutionary Patterns and Association between Phylogeny and Clinical Variables. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, E.C.; McEntee, C.P. Vaccine adjuvants: Tailoring innate recognition to send the right message. Immunity 2024, 57, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guan, Y.; Lv, M.; Zhang, R.; Guo, Z.; Wei, X.; Du, X.; Yang, J.; Li, T.; Wan, Y.; Su, X.; Huang, X.; Jiang, Z. Manganese Increases the Sensitivity of the cGAS-STING Pathway for Double-Stranded DNA and Is Required for the Host Defense against DNA Viruses. Immunity 2018, 48, 675–687.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; Guan, Y.; Wei, X.; Sha, M.; Yi, M.; Jing, M.; Lv, M.; Guo, W.; Xu, J.; Wan, Y.; Jia, X.M.; Jiang, Z. Manganese salts function as potent adjuvants. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, K.; Yamada, H.; Hori, A.; Yajima, T.; Kubo, C.; Yoshikai, Y. IL-15 exacerbates collagen-induced arthritis with an enhanced CD4+ T cell response to produce IL-17. Eur J Immunol 2007, 37, 2744–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neurath, M.F. IL-23 in inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2019, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao R, Peng J, Zhang L, Chen J, Lv X, Li J, Wang Z, Wei H Luo Q, Porcine interleukin-15, 21 and 23 co-expressed biological preparation material and applications thereof, p. 23.

- Chen, G.; Ran, X.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Huang, B.; Fu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, W. Sodium Butyrate Inhibits Inflammation and Maintains Epithelium Barrier Integrity in a TNBS-induced Inflammatory Bowel Disease Mice Model. EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.P.; Price, N.L.; Ling, A.J.; Moslehi, J.J.; Montgomery, M.K.; Rajman, L.; White, J.P.; Teodoro, J.S.; Wrann, C.D.; Hubbard, B.P.; Mercken, E.M.; Palmeira, C.M.; de Cabo, R.; Rolo, A.P.; Turner, N.; Bell, E.L.; Sinclair, D.A. Declining NAD(+) induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell 2013, 155, 1624–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, T.; Yin, Y. Serine signaling governs metabolic homeostasis and health. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2023, 34, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, B. NAC, NAC, Knockin' on Heaven's door: Interpreting the mechanism of action of N-acetylcysteine in tumor and immune cells. Redox Biol 2022, 57, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, J.; Buyse, J.; Goddeeris, B.M. Dietary L-carnitine supplementation increases antigen-specific immunoglobulin G production in broiler chickens. Br J Nutr 2000, 83, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meryk, A.; Grasse, M.; Balasco, L.; Kapferer, W.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B.; Pangrazzi, L. Antioxidants N-Acetylcysteine and Vitamin C Improve T Cell Commitment to Memory and Long-Term Maintenance of Immunological Memory in Old Mice. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L.; Maier, A.B.; Tao, R.; Lin, Z.; Vaidya, A.; Pendse, S.; Thasma, S.; Andhalkar, N.; Avhad, G.; Kumbhar, V. The efficacy and safety of β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation in healthy middle-aged adults: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-dependent clinical trial. Geroscience 2023, 45, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.F. VARIANCE ESTIMATION IN THE REED-MUENCH FIFTY PER CENT END-POINT DETERMINATION. Am J Hyg 1964, 79, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shanghai GlinX Biotechnology Co., Ltd,-FiDX. Available online: https://www.glinxbio.com/fidx (Accessed 05 April 2025).

- Huang, C.; Hess, J.; Gill, M.; Hustead, D. A dual-strain feline calicivirus vaccine stimulates broader cross-neutralization antibodies than a single-strain vaccine and lessens clinical signs in vaccinated cats when challenged with a homologous feline calicivirus strain associated with virulent systemic disease. J Feline Med Surg 2010, 12, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lappin, M.R. Feline panleukopenia virus, feline herpesvirus-1 and feline calicivirus antibody responses in seronegative specific pathogen-free kittens after parenteral administration of an inactivated FVRCP vaccine or a modified live FVRCP vaccine. J Feline Med Surg 2012, 14, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Foley, P.; Yason, C.; Vanderstichel, R.; Muckle, A. Prevalence of feline herpesvirus-1, feline calicivirus, Chlamydia felis, and Bordetella bronchiseptica in a population of shelter cats on Prince Edward Island. Can J Vet Res 2020, 84, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Wei, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tian, X. Vaccine adjuvants: mechanisms and platforms. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Huang, F.; Zhou, M.; Chen, H.; Fu, Z.F.; Zhao, L. Colloidal Manganese Salt Improves the Efficacy of Rabies Vaccines in Mice, Cats, and Dogs. J Virol 2021, 95, e0141421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decout, A.; Katz, J.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Ablasser, A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, L.; Argyle, D.; Bain, D.; Nicolson, L.; Dunham, S.; Golder, M.C.; McDonald, M.; McGillivray, C.; Jarrett, O.; Neil, J.C.; Onions, D.E. Feline leukemia virus DNA vaccine efficacy is enhanced by coadministration with interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 expression vectors. J Virol 2001, 75, 8424–8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Leggat, D.; Herbert, A.; Roberts, P.C.; Sundick, R.S. A novel method to incorporate bioactive cytokines as adjuvants on the surface of virus particles. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2009, 29, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluns, K.S.; Williams, K.; Ma, A.; Zheng, X.X.; Lefrançois, L. Cutting edge: requirement for IL-15 in the generation of primary and memory antigen-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol 2002, 168, 4827–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sabatino, A.; Calarota, S.A.; Vidali, F.; Macdonald, T.T.; Corazza, G.R. Role of IL-15 in immune-mediated and infectious diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2011, 22, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, J.G.; Eyerich, K.; Kuchroo, V.K.; Ritchlin, C.T.; Abreu, M.T.; Elloso, M.M.; Fourie, A.; Fakharzadeh, S.; Sherlock, J.P.; Yang, Y.W.; Cua, D.J.; McInnes, I.B. IL-23 past, present, and future: a roadmap to advancing IL-23 science and therapy. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1331217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, H.; Mashiko, S.; Angsana, J.; Rubio, M.; Hsieh, Y.M.; Maari, C.; Reich, K.; Blauvelt, A.; Bissonnette, R.; Muñoz-Elías, E.J.; Sarfati, M. Differential Changes in Inflammatory Mononuclear Phagocyte and T-Cell Profiles within Psoriatic Skin during Treatment with Guselkumab vs. Secukinumab. J Invest Dermatol 2021, 141, 1707–1718.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Li, J.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Ye, Y. IL-7/IL-15/IL-21/IL-23 effectively promote the generation of human CD8(+) central memory T cells in vitro. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 2021, 37, 872–880. [Google Scholar]

- Kaech, S.M.; Wherry, E.J.; Ahmed, R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol 2002, 2, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M.I.; Catalan-Dibene, J.; Zlotnik, A. B cells responses and cytokine production are regulated by their immune microenvironment. Cytokine 2015, 74, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulendran, B.; P, S.A.; O'Hagan, D.T. Emerging concepts in the science of vaccine adjuvants. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belperron, A.A.; Dailey, C.M.; Booth, C.J.; Bockenstedt, L.K. Marginal zone B-cell depletion impairs murine host defense against Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Infect Immun 2007, 75, 3354–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).