1. Introduction

Since the coronavirus outbreak in December 2019, various drugs and vaccines against COVID-19 received marketing authorization, mostly with emergency approval [

1]. With these drugs, symptoms can usually be treated effectively, and in vaccinated individuals, the course of infection is predominantly mild. In addition, herd immunization led to the fact that the pandemic was no longer considered a global emergency as of May 05, 2023. COVID-19 now has a globally established and persistent disease status. Therefore, the pandemic would no longer meet the definition of a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” (PHEIC). However, the WHO stresses the fact that it is still existing [

2]. Many individuals become infected or reinfected with SARS-CoV2 even though they have already received a vaccination [

3]. COVID-19 had a disproportionate impact on the elderly and those with comorbidities, with higher rates of severe illness, and hospitalization.

It is known from studies that IgG levels can drop after a short time already with various vaccines on the market. This was evident with both mRNA vaccines with which the patients in the present study were vaccinated [

4]. The decrease in IgG antibodies could be associated with decreasing immunogenicity. A strong correlation between SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific CD4+ T cells and IgG antibodies was shown by Grifoni et al. 2020 [

5].

5-Aminolevulinic acid is a natural substance found in mitochondria and is significantly involved in producing ATP and thus energy provision [

6,

7]. As phosphate salt and in combination with SFC, it has already been on the Japanese market since 2010 as an over-the-counter dietary supplement for faster recovery after sports activities, among other things. In vitro tests showed that targeted and supplemental intake of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC can strengthen mitochondrial functions in aged cells [

8]. Hu et al. [

9] showed in a melanoma model, that 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC appears to be an important metabolic regulator in depleted T cell metabolism. Thus, it can be speculated that administration of the dietary supplement 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC may positively influence the immune response by enhancing immune cells through improved energy presence. Recent preclinical evidence has been generated supporting the anti-viral effect of 5-ALA-phosphate against Classical Swine Fever virus and different variants of SARS-CoV-2 [

10,

11].

Because of the strong correlation with SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses, measurement of IgG titer appears to be an appropriate parameter to investigate the supportive potential of the supplement 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC on the immune system and, in this study, specifically on vaccination support to achieve sustained immunity against viruses.

In this study, it was hypothesized that the administration of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC in subjects vaccinated against COVID-19 could enhance the immune system, leading to re-activation and increase of the vaccination response shown in the IgG titer. However, as it was planned as a pilot study, the primary objective was the evaluation of the safety and tolerability especially for unwished immune reactions when 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC is administered together and up to several weeks after a vaccination.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study was an open-label, two-arm interventional exploratory study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 5-ALA-Phosphate + SFC during the vaccination of subjects against SARS- - CoV-2 . This study was approved and monitored by the Institutional/Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) to safeguard the rights, safety, and well-being of all trial participants, and was conducted following good clinical practice in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, revised by the World Medical Association (WMA) 59th General Assembly, Seoul 2008, the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) recommendation on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) - E6(R2), 2016, and National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research involving Human Participants, 2017 issued by Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), India. All patients provided written informed consent. A clinical monitor regularly checked data integrity and quality during on-site monitoring visits.

The subjects were vaccinated within 24 hours of screening. At least 250 subjects were screened, of which 200 subjects were recruited. The recruited subjects were randomized in a ratio of 1:1 within 2 arms (5-ALA-phosphate + SFC and Control) to get not more than 160 completed subjects (80 in each arm), keeping 20% dropouts or lost to follow-up.

Only male and female subjects aged between 18 years and 70 years with a documented proof of 1st/2nd dose of vaccination were included in the study. Moreover, the subjects were planning to have a 2nd/3rd dose of the COVID-19 vaccine (Covishield/ Covaxin) and were willing and able to provide written informed consent.

However, subjects were excluded from trial participation when they suffered from an anemia (defined as Hemoglobin level: male: <12 g/dl, females: <11 g/dl) or their liver enzymes Alanin-Aminotransferase (ALT) and Aspartat-Aminotransferase (AST) were clinically relevant elevated (more than 2.5 times the upper limit). Moreover, subjects with an acute symptomatic COVID-19 infection indicated by fever, dry cough, and severe respiratory distress were excluded from the trial. The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found at ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT05234346).

The study participants were supplemented with 5-ALA phosphate + SFC for 21 days, and the safety of the IP was determined by monitoring the occurrence of adverse events. In addition, the efficacy of the IP was evaluated by comparing the absolute change in GMT of IgG levels against COVID-19 spike protein, EQ-5D-5L score, WHO-5 well-being score, and VAS for pain and fatigue.

The total study duration was 24 days, with an intervention period of 21 days.

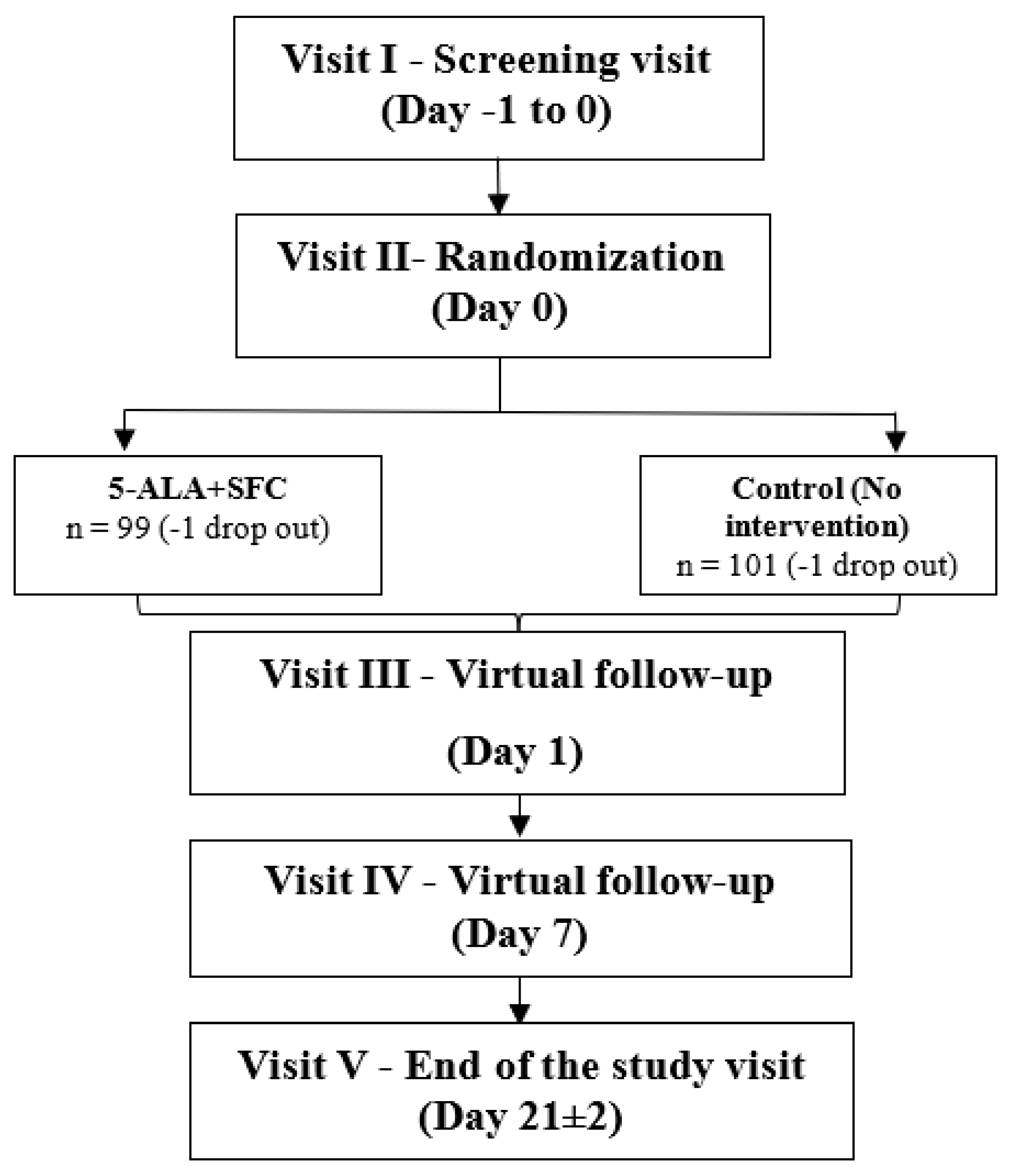

A detailed flow chart of the time points at which safety, efficacy, and other assessments were to be carried out is given in

Figure 1.

In addition, the visit-specific study schedule is provided in Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.

Table 1.

Study Visit Schedule.

Table 1.

Study Visit Schedule.

| Study day |

Screening /randomization visit

(Day 0) |

Virtual visit

(Day 1) |

Virtual visit

(Day 7) |

End of Study Visit (Day 21±2) |

| Visits |

1 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Informed consent |

X |

|

|

|

| Medical history |

X |

|

|

|

| Medication history |

X |

|

|

|

| Study-specific history |

X |

|

|

X |

Demographics data

(age, gender) |

X |

|

|

|

| Anthropometrics data (Height and Weight) |

X |

|

|

|

Vitals

(PR, BP, SpO2, and Body temperature) |

X |

|

|

X |

| Urine pregnancy test |

X |

|

|

X |

| Clinical examination |

X |

|

|

X |

| Concomitant medication |

|

|

|

X |

| RT-PCR |

|

X |

X |

| Blood sample collection (Hemoglobin, ALT & AST) |

X |

|

|

|

| Inclusion/Exclusion criteria |

X |

|

|

|

| Randomization process |

X |

|

|

|

| 2nd dose / Booster dose |

X |

|

|

|

| Blood sample collection (IgG) |

X |

|

|

X |

| EQ-5D-5L |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| VAS (pain and fatigue) |

X |

X#

|

X |

| WHO-5 well-being questionnaire |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| IP dispensing |

X |

|

|

|

| IP diary dispensing |

X |

|

|

|

| Daily diary dispensing |

X |

|

|

X |

| IP reconciliation |

|

|

|

X |

| AE/SAE |

X |

| ADR |

X |

All types of concomitant medication as prescribed by the physicians/investigators were allowed in this study except for experimental substances / investigational medicinal products that were not on the market and applied in the context of another clinical study. Moreover, taking vitamin D supplements during the trial was prohibited. Vitamin B and C supplements were allowed during the study.

Details of prior medications taken within 28 days before the start of screening and throughout the study and concomitant medications taken during the study, including start date, stop date or ongoing, the reason for use, dose, route, and frequency, were collected.

Continuous variables were subjected to normality testing using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and if found normal, then analysed using parametric tests, and non-normal data were analysed using non-parametric tests for hypothesis testing. Demographic and other baseline parameters were compared between the arms for differences using the Mann-Whitney ‘U’ test (non-parametric, 2 independent-sample test) for continuous data and the chi-square test for categorical data.

Incidence of adverse product reaction (APR) and solicited vaccine-related local and systemic reactions were analysed using the Chi-square test/Fisher-exact test for differences between the two arms. A listing of all adverse events (original term) has been generated, including severity, seriousness and causality, action taken, and outcome. The number and percentage of participants with Adverse Events were summarized using MedDRA terms grouped by preferred terms and system organ classes. Furthermore, the number of events was calculated. Other secondary outcomes were compared between the two arms using the Mann-Whitney U test and ANCOVA with intervention as a factor and baseline as a covariate where appropriate. The within-group comparison between the baseline and post-baseline assessments was the Wilcoxon-signed rank test or Friedman’s test as appropriate. A p-value <0.05 and 95% confidence intervals were considered for statistical significance, and a two-tailed hypothesis was tested.

As the primary objective of this study was safety, the primary endpoints were defined as follows:

Number of participants with adverse product reactions as per CTCAE grading, and

The secondary objective is the efficacy of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC in enhancing the immune system, the secondary endpoints are measured by the change in the following parameters as compared to the control arm:

Absolute change in GMT of IgG levels against SARS-Cov-2 spike protein.

European Quality of life five dimensions five-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) Score.

Visual analog scale (VAS) for pain and fatigue

WHO-5 well-being questionnaire

3. Results

200 participants, aged between 18-70 years were screened and randomized to two of the study arms. Of these, 198 participants with a mean age of 42.2 and 39.9 years in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC and control arms, respectively completed the study. Almost half of the participants in both arms had a positive COVID-19 history. Covishield was the vaccine of choice for most participants in both arms. In both arms, almost equal numbers of participants were vaccinated with the second and booster dose of vaccination during the study. The oxygen saturation level of the participants ranged from 93 to 100%. In both arms, most participants had serum IgG levels <5000 U/ml at baseline.

It was observed that both 5-ALA-+ SFC and control arms showed a remarkable increase in the WHO-5 well-being index scores, indicating the improvement in the well-being of the participants over 21 days of the study period. The improvement was numerically greater in the intervention arm (mean change from baseline: +7.63) than in the control arm (mean change from baseline: +4.04); however, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two arms (p = 0.75).

Both 5-ALA+ SFC and control arms showed a remarkable reduction in the VAS scores for pain at the injection site over the study period, with no pain at the end of the intervention. However, no significant difference was observed between the two arms except on Day 6, when a statistically significant difference (p = 0.04) was noted in the two arms, with the control arm having a better reduction in VAS scores compared to the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC arm.

The generalized overall fatigue VAS scores showed a remarkable reduction as well in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC and control arms over the study period from baseline scores. However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two arms at any single timepoint.

3.1. Primary Outcome – Safety: Adverse Product Reactions

One hundred ninety-eight participants reported adverse events during the study, out of which 97 were in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC arm and 101 in the control arm. However, none of the adverse events was related to the study product. A total of 537 events were reported during the study, 268 in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC + vaccine arm and 269 in the control arm. Twenty AEs reported after vaccine administration were reported to be unrelated to either the vaccine or the study product.

During the study duration, a total of 537 events were reported during the study, 268 in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC + vaccine arm and 269 in the control arm.

The two arms were comparable in the number of adverse events reported after vaccine administration (with p-values from 0.38 to 0.68). Except for fatigue a signal for statistically difference between the arms after vaccination has been observed with 86 cases in the 5-ALA + SFC arm and 95 cases in the control arm (p = 0.08). The odds ratio of not having an AE in the intervention group was 5.205 times compared to the control (

Table 2).

During the study duration, 517 out of 537 reported adverse events were found to be related to the vaccine administration, as presented in Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.. The two arms were comparable in the number of adverse events reported after vaccine administration.

Table 3.

Adverse events related to vaccine administration in two arms (FAS dataset).

Table 3.

Adverse events related to vaccine administration in two arms (FAS dataset).

| |

Preferred Term |

5-ALA+SFC (N=99) |

Control (N=101) |

Total

N=200

|

p-value |

| N (%) |

n |

N (%) |

n |

N (%) |

N |

| Local |

Injection site erythema |

0 (0.0%) |

0 |

4 (4.0%) |

4 |

4 (2.0%) |

4 |

NE |

| Injection site pain |

96 (97.0%) |

100 |

99 (98.0%) |

101 |

195 (97.5%) |

201 |

0.6812 (F) |

| Injection site rash |

0 (0.0%) |

0 |

1 (1.0%) |

1 |

1 (0.5%) |

1 |

NE |

| Systemic |

Asthenia |

5 (5.1%) |

5 |

2 (2.0%) |

2 |

7 (3.5%) |

7 |

0.2767 (F) |

| Diarrhoea |

1 (1.0%) |

1 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 |

1 (0.5%) |

1 |

NE |

| Fatigue |

86 (86.9%) |

106 |

95 (94.1%) |

108 |

181 (90.5%) |

214 |

0.0829 (C) |

| Headache |

8 (8.1%) |

8 |

7 (6.9%) |

7 |

15 (7.5%) |

15 |

0.7575 (C) |

| Myalgia |

7 (7.1%) |

7 |

5 (5.0%) |

5 |

12 (6.0%) |

12 |

0.5279 (C) |

| Nausea |

2 (2.0%) |

2 |

1 (1.0%) |

1 |

3 (1.5%) |

3 |

0.6193 (F) |

| Pyrexia |

31 (31.3%) |

31 |

26 (25.7%) |

26 |

57 (28.5%) |

57 |

0.3829 (C) |

| Somnolence |

1 (1.0%) |

1 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 |

1 (0.5%) |

1 |

NE |

| Vomiting |

1 (1.0%) |

1 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 |

1 (0.5%) |

1 |

NE |

| |

Total |

97 (98.0%) |

262 |

100 (99.0%) |

255 |

197 (98.5%) |

517 |

0.6193 (F) |

Twenty AEs reported after vaccine administration were reported to be unrelated to either the vaccine or the study product. (

Table 4). All these 20 events occurred after a substantial amount of time of starting the IP. Most of the events were resolved with symptomatic treatment with sequelae. The participants could complete the treatment duration thereafter uneventfully. Hence, all the events were judged by the Investigator as not related to the IP. Also, no serious adverse events were reported during the study.

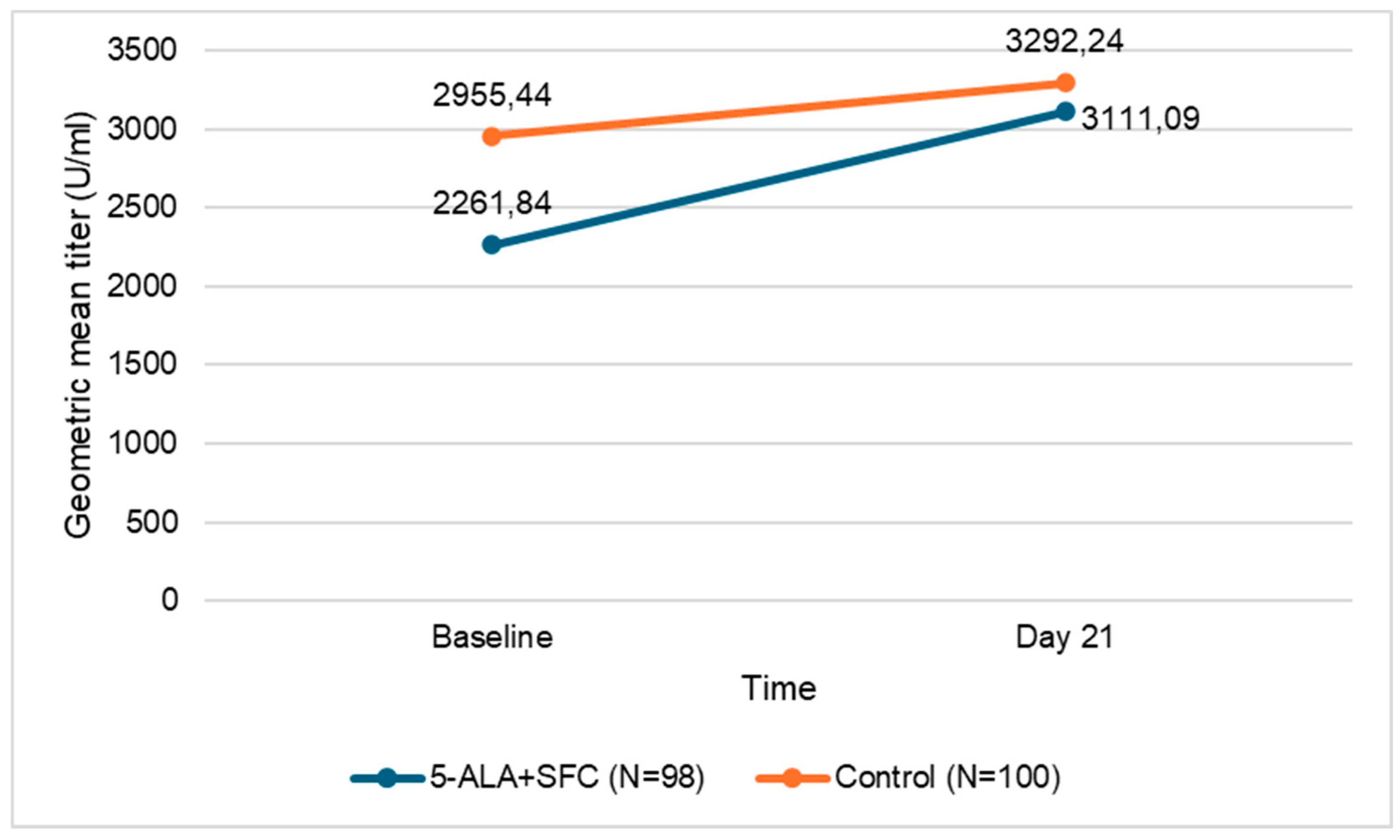

3.2. Secondary Outcome – Efficacy: Change im GMT of IgG Levels Against COVID-19 Spike Protein

The GMT is the preferred statistic for presenting the immune response to a vaccine [

12]. The baseline and day 21 GMT of IgG antibodies are presented in Table 5 and

Figure 2. The GMT of IgG in both study arms increased from the baseline values.

| Assessment |

5-ALA+SFC (N=98) |

Control (N=100) |

| |

GMT (U/ml) |

95% CI |

GMT (U/ml) |

95% CI |

| Baseline |

2261.84 |

1676.82 - 3050.98 |

2955.44 |

2287.00 - 3819.24 |

| Day 21 |

3111.09 |

2383.67 - 4060.48 |

3292.24 |

2669.28 - 4060.60 |

| Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval, GMT=geometric mean titer, N=number of participants. |

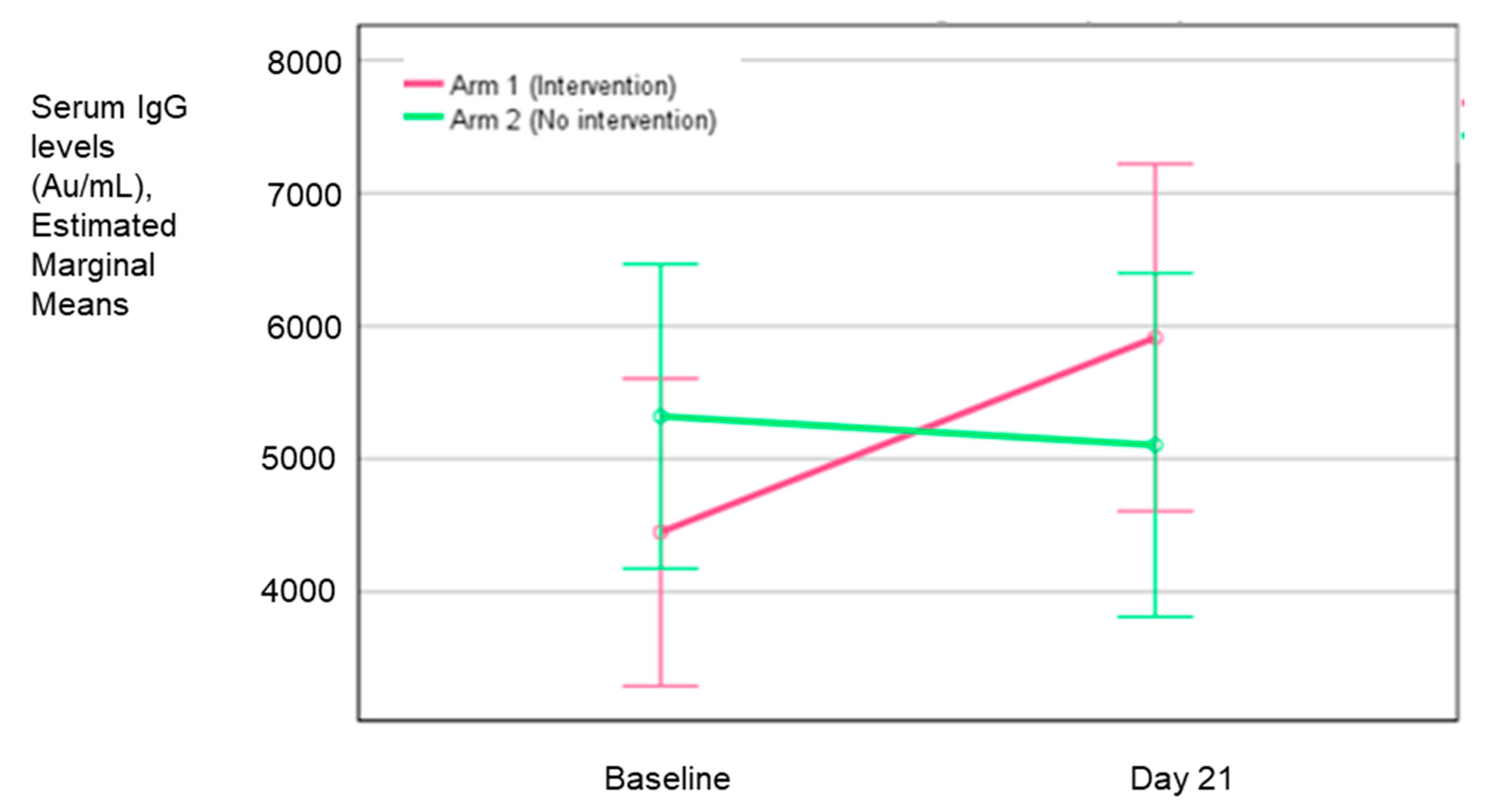

Table 6 and

Figure 3 show the adjusted (least square method) mean change in the GMT and the GMT ratio for both arms, indicating that the change in the intervention arm was 1.08 times more than the control arm. However, the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.56).

The above figure represents the LS means of serum IgG levels in the two arms from baseline to day 21.

Also, the geometric mean fold rise in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC with the vaccine arm (intervention arm) was greater (1.38) after 21 days of intervention compared to the only vaccine arm (control arm) (1.11). However, the rise was not statistically significant from the baseline in both arms (

Table 7). Although, the results were not statistically significant, a clear trend can be seen that the dietary supplement 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC increased the IgG antibody titer remarkably more in the intervention arm than in the control group, in which the subjects received vaccination only.

Arithmetic means: The baseline mean serum IgG level was less than 5000 U/ml in the intervention arm and more than 5000 U/ml in the control arm; however, this difference between the arms was statistically insignificant (

Table 8). On day 21, there was an increase in the mean serum IgG values in the intervention arm and a decrease in the control arm. The difference between the two arms was not significant. On the contrary, the median values of IgG levels show an increase in both arms on day 21 from their baseline values.

Mean and median change in both arms shows an increase in the intervention arm, while there was a decrease or no change in the control arm. However, the change from the baseline and between the groups was not clinically or statistically significant.

Domain-wise summary of EQ-5D-5L showed that no statistically significant difference was observed between the two arms at any time point in any of the domains of quality of life during the study.

3.2.1. Subgroup Analyses

Based on the values of serum IgG observed at baseline in the study population, three subgroups - <1000, 1000 to <5000, and ≥5000 U/ml were formed, and analyses were performed with GMT and arithmetic means of serum IgG levels.

Further, age and COVID-19 history-based categories were formed, and serum IgG levels were analyzed, as presented in

Table S1 and

Table S2.

Based on the values of serum IgG observed at baseline in the study population, three subgroups - <1000, 1000 to <5000, and ≥5000 U/ml were formed, and analyses were performed with GMT and arithmetic means of serum IgG levels.

Further, age and COVID-19 history-based categories were formed, and serum IgG levels were analyzed.

After approximately a month of a viral vector COVID vaccination, the generally found IgG antibody titer is 3615.3 AU/ml [

13]. In the subgroup with <1000 U/ml IgG levels, a statistically significant increase in the GMT of the IgG antibodies from baseline to day 21 in both 5-ALA + SFC and control arm was observed.

In the subgroup with <5000 U/ml baseline IgG level, a statistically significant increase in the GMT of the IgG antibodies in both 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC and the control arm was observed. On the contrary, in the subgroup having ≥5000 U/ml baseline IgG levels, a reduction was observed in GMT of IgG antibodies in both 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC and the control arm; however, this reduction was statistically significant only in the control arm (Table 9).

An increase in the GMT of IgG antibodies was observed from baseline across the two age categories, and this increase was statistically insignificant in both arms. However, when the age categories were further divided based on the COVID-19 history of the participants, it was noted that the control arm having negative COVID-19 history (COVID -ve) and <50 years of age, experienced a significant reduction in GMT of IgG antibodies.

With subgroup analysis presented as arithmetic means IgG levels, shows no statistically significant difference between the two groups after 21 days of intervention. However, some trends were observed. Subjects with a low baseline IgG antibody level (<1,000 U/ml) in the intervention group showed after 21 days of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC administration an approximately 2-fold higher IgG antibody titer level (4,414 U/ml) than comparable subjects in the control group (2,411 U/ml). There was an increase in the IgG levels from baseline to day 21 in the participants who had baseline IgG levels < 5,000 U/ml, while those with baseline IgG levels ≥5000 U/ml had a reduction in mean (from 11,147 U/ml at baseline to 9400 U/ml after 21 days in the intervention group; from 10,902 U/ml at baseline to 6,000 U/ml after 21 days in the control group) & median IgG (from 9,650 U/ml at baseline to 7,901 U/ml after 21 days in the intervention group; from 7,130 U/ml at baseline to 4649 after 21 days in the control group) on day 21 from the baseline levels.

In the subgroup analysis based on age and COVID history, it was observed that those who belonged to <50 years of age, had a positive COVID-19 history (COVID +ve), and received 5-ALA-Phosphate + SFC reported a very small decrease in the median IgG levels (from 2,500 U/ml at baseline to 2,393 U/ml on day 21) while those who received no intervention showed an increase in their median IgG levels (from 2,500 U/ml at baseline to 4,207 U/ml on day 21). On the contrary, those who had a negative COVID history (COVID -ve) and received 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC reported a very small increase in the median IgG levels (from 3,182 U/ml at baseline to 3,783 U/ml on day 21), and those who received no intervention demonstrated a decrease in median IgG level (from 3,631 U/ml at baseline to 2,750 U/ml on day 21).

Participants aged ≥50 years showed an increase in their median IgG levels irrespective of their COVID history; however, the difference between the two groups was statistically insignificant.

4. Discussion

Results from a former study suggested that neutralizing antibodies are critical for immune protection [

14]. Emerging evidence has also suggested that SARS-CoV-2-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, in coordination with neutralizing antibodies, are required to generate protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2 [

15]. Adjuvants such as aluminum-based salts, TLR agonists, emulsions, and other novel adjuvants have distinctive physicochemical properties, which can be significant in regulating the strength, duration, and types of immune responses [

16,

17,

18]. Previous preclinical studies have shown that vaccine adjuvants such as alum produced a geometric mean titer (GMT) twice as high as the non-adjuvanted vaccine [

19]. Based on the previous evidence [

10,

11], it was hypothesized that the administration of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC in subjects vaccinated against Covid-19 could enhance the targeted function of the immune system, which might lead to re-activation and/or increase the vaccination response. The current study was designed to test the antibody response potentiation after the second as well as booster doses of different viral vector vaccines.

The study results demonstrated that the combination of 5-ALA-phosphate and SFC, when administered to recently vaccinated individuals, was completely safe as no product-related adverse events were reported during the study. It was also noted that adding 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC to the vaccines resulted in 5 times higher odds of having no AE post-vaccination. Most of the AEs reported post-vaccination were related to the vaccine, were mild and resolved without complications, and were comparable to the previous studies on the vaccine [

20,

21].

The safety of the product has also been demonstrated in several clinical studies on hyperglycemic subjects and patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exposure ranged from 1 day to 12 weeks, and the doses administered ranged from 5 mg to 1,500 mg of 5-ALA-phosphate and 2.87 mg to 2,351 mg SFC [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Additionally, 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC administration post-vaccination for 21 days could increase the IgG antibody titer by 1.08 times as high as the control group with only COVID vaccination. The geometric mean fold rise (GMFR) in the 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC arm was greater (1.38) than in the control arm (1.11) without intervention after 21 days. Although the results were not statistically significant, a clear trend can be seen that the dietary supplement 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC increased IgG antibody titer more than in the control group, in which the subjects received vaccination only. This trend can be especially noticed in the subgroup analysis based on baseline serum IgG levels, age group, and/or COVID history (Table 10). Subjects with a low baseline IgG antibody level (<1,000 U/ml) reached in the intervention group after 21 days of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC administration an approximately 2-fold higher IgG antibody titer level (4,414 U/ml) than comparable subjects in the control group (2,411 U/ml). Therefore, supplementation might be particularly recommended in subjects with low baseline IgG titers. However, this is not limited to this subgroup as concomitant administration is generally safe and no contrary trend was observed in other baseline titer categories. For instance, a positive impact can be demonstrated in subjects with high IgG antibody levels (>/=5,000 U/ml), in whom high IgG antibody levels persisted longer in the intervention group (from 11,147 U/ml at baseline to 9,400 U/ml after 21 days of supplementation) than in the control group (from 10,902 U/ml at baseline to 6,000 U/ml after 21 days without supplementation). The same trend can be noticed in subjects with an age of ≥50 years and a positive COVID history. Again, the administration of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC kept the subjects at a high IgG antibody level for longer. Thus, a slight increase was observed in the intervention group (+ 186 U/ml), while there was even a remarkable decrease of IgG antibodies (- 1,124 U/ml) in the group with vaccination alone.

Although the results are not statistically significant, it can be stated that 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC is a potentially beneficial supplement when taken after COVID-19 vaccination. The evaluation of subject recordings from established quality of life questionnaires (EQ-5D-5L and WHO well-being) leads to the statement that 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC administration did not limit well-being, which is already a quite important result.

The VAS scores for pain at the injection site and the generalized overall fatigue also showed no statistically significant difference between the two arms. However, this can be envisioned as a positive outcome considering that the immune-boosting potential of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC is not accompanied by increased vaccination-related adverse events like pain at the injection site.

The evaluation of the subject questionnaires showed that the administration did not limit the well-being of the participants, which confirms the excellent tolerability of this food supplement. However, further studies would be recommended for verification of the results.

5. Conclusions

5-ALA-phosphate + SFC (150 mg daily) can be safely given together with (vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 (Covishield/Covaxin, viral vector vaccines) and up to 21 days thereafter. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was met. Moreover, the results for the secondary endpoint ‘Change in Immunoglobulin G levels’, although statistically not significant provided strong signals of immune-boosting properties of 5-ALA-phosphate + SFC. Therefore, IgG antibody titer increases were remarkably greater in the intervention group than in the control group. The evaluation of the subject questionnaires showed that the administration did not limit the well-being of the participants, which confirms the excellent tolerability of this food supplement. However, further studies would be recommended for verification of the results and to investigate the transferability to other types of vaccines and target indications e.g. influenza.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Norbert Berenzen, Andrea Ebeling, Riyadh Rehani, Marcus Stocker, and Motowo Nakajima, designed and supervised the study. Riyadh Rehani, Motowo Nakajima, and Norbert Berenzen wrote the manuscript. Norbert Berenzen was primarily responsible for final content and editing. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript..

Funding

This study was funded by SBI ALApromo GmbH, Germany, a subsidiary of Photonamic GmbH & Co. KG, Germany and conducted by Vedic Lifesciences Pvt. Ltd., India.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved and monitored by the Institutional/Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) to safeguard the rights, safety, and well-being of all trial participants, and was conducted following good clinical practice in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, revised by the WMA General Assembly, Seoul 2008), International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) recommendation on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) - E6(R2), 2016, and National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research involving Human Participants, 2017 issued by Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), India. The study was registered with the NIH ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT05234346) and Clinical Trials Registry India (Registration Number: CTRI/2022/03/040990).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Most data are contained within the article. Additional data needed could be retrieved from the study report.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the investigators, Deepak Varade, Prasad Nikam, Namdev Jagtap, Madhumati Varma, and Shalini Srivastava, who conducted the clinical part of the study. Moreover, we thank Vedic Lifesciences (Mumbai, India) for the statistical analysis and evaluation of the study results as well as SBI Pharmaceuticals Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) for providing the study products.

Conflicts of Interest

Norbert Berenzen is a global project manager, Riyadh Rehani is a senior scientific advisor, Andrea Ebling is a director of scientific and medical evaluation, Marcus Stocker is a director of clinical project management. They are employees at Photonamic GmbH, a subsidiary of SBI ALApharma. Motowo Nakajima is a director of SBI Pharmaceuticals, Japan. However, none of these authors have further financial arrangements (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interests, patent-licensing arrangements, research support, or major honorary).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-ALA |

5-Aminolevulinic acid |

| SFC |

Sodium Ferrous Citrate |

| AE |

Adverse Event |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| PHEIC |

Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| mRNA |

Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| IEC |

Institutional/Independent Ethics Committee |

| WMA |

World Medical Association |

| ICH |

International Conference on Harmonization |

| GCP |

Good Clinical Practice |

| ICMR |

Indian Council of Medical Research |

| ALT |

Alanine-Aminotransferase |

| AST |

Aspartate-Aminotransferase |

| GMT |

Geometric Mean Titer |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

| PR |

Pulse Rate |

| BP |

Blood Pressure |

| SPO2 |

Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| EQ-5D-5L |

5-demension-Quality of Life Questionnaire from EuroQuol group |

| IP |

Investigational Product |

| SAE |

Serious Adverse Event |

| ADR |

Adverse Drug Reaction |

| APR |

adverse product reaction |

| FAS |

Full Analyses |

| ITT |

Intention-To-Treat |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| GMFR |

geometric mean fold rise |

| N |

Number of participants |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| U |

Unit |

References

- Vasireddy, D.; Atluri, P.; Malayala, S.V.; Vanaparthy, R.; Mohan, G. Review of COVID-19 Vaccines Approved in the United States of America for Emergency Use [published correction appears in J Clin Med Res. 2021, 13(4), 204–213. [CrossRef]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: Factors Driving New Variants of SARS-CoV-2, Immune Escape, and Resistance to Antiviral Treatments as the End of the COVID-19 Pandemic is Declared. Med Sci Monit. 2023, 29, e942960. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Miah, M.; Begum, M.N.; Sarmin, M.; Mahfuz, M.; Hossain, M.E.; Rahman, M.Z.; Chisti, M.J.; Ahmed, T.; et al. COVID-19 reinfections among naturally infected and vaccinated individuals. Sci Rep. 2022, 12(1), 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisnewski, A.V.; Redlich, C.A.; Liu, J.; Kamath, K.; Abad, Q.-A.; Smith, R.F.; Fazen, L.; Santiago, R.; Luna, J.C.; Martinez, B.; et al. Immunogenic amino acid motifs and linear epitopes of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. PLoS ONE 2021, 16(9), e0252849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell 2020, 181(7), 1489–1501.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, S.; Maruyama, K.; Hagiya, Y.; Sugiyama, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Takahashi, K.; Abe, F.; Tabata, K.; Okura, I.; Nakajima, M.; et al. The effect of 5-aminolevulinic acid on cytochrome c oxidase activity in mouse liver. BMC Res Notes. 2011, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, C.; Miyashita, K.; Mitsuishi, M.; Sato, M.; Fujii, K.; Inoue, H.; Hagiwara, A.; Endo, S.; Uto, A.; Ryuzaki, M.; et al. Treatment of sarcopenia and glucose intolerance through mitochondrial activation by 5-aminolevulinic acid. Sci Rep. 2017, 7(1), 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozawa, N.; Noguchi, M.; Shinno, K.; Tajima, M.; Aizawa, S.; Saito, T.; Asada, A.; Ishii, T.; Ishizuka, M.; Iijima, K.M.; et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid and sodium ferrous citrate ameliorate muscle aging and extend healthspan in Drosophila. FEBS Open Bio. 2022, 12(1), 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Que, W.; Hirano, H.; Wang, Z.; Nozawa, N.; Ishii, T.; Ishizuka, M.; Ito, H.; Takahashi, K.; Nakajima, M.; et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid/sodium ferrous citrate enhanced the antitumor effects of programmed cell death-ligand 1 blockade by regulation of exhausted T cell metabolism in a melanoma model. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112(7), 2652–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S.; Isoda, N.; Huynh, L.T.; Kim, T.; Yoshimoto, K.; Tanaka, T.; Inui, K.; Hiono, T.; Sakoda, Y. Antiviral Effects of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Phosphate against Classical Swine Fever Virus: In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Pathogens. 2022, 11(2), 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwe Tun, M.M.; Sakura, T.; Sakurai, Y.; Kurosaki, Y.; Inaoka, D.K.; Shioda, N.; Yasuda, J.; Kita, K.; Morita, K. ; Antiviral activity of 5-aminolevulinic acid against variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Trop Med Health. 2022, 50(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverberi, R. The statistical analysis of immunohaematological data. Blood Transfus. 2008, 6(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, M.; Jain, M.; Patel, N.; Sharma, A. Quantitative estimation of anti-spike SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody response after covishield vaccination in healthcare workers. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2022, 34, 176-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Yang, Y. The potential danger of suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020, 20(6), 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arturo, E.C.; Saphire, E.O. Lifted Up from Lockdown. Cell. 2020, 183(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhartchouk, A.N.; Sharon, C.; Satkunarajah, M.; Auperin, T.; Viswanathan, S.; Mutwiri, G.; Petric, M.; See, R.H.; Brunham, R.C.; Finlay, B.B.; et al. Immunogenicity of a receptor-binding domain of SARS coronavirus spike protein in mice: implications for a subunit vaccine. Vaccine 2007, 25(1), 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, H.; Wu, C. The immune responses of HLA-A*0201 restricted SARS-CoV S peptide-specific CD8⁺ T cells are augmented in varying degrees by CpG ODN, PolyI:C and R848. Vaccine. 2011, 29(38), 6670–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wu, J.; Wei, W.; Du, Y.; Wan, T.; Ma, X.; An, W.; Guo, A.; Miao, C.; Yue, H.; et al. Exploiting the pliability and lateral mobility of Pickering emulsion for enhanced vaccination. Nat Mater. 2018, 17(2), 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Post, P.; Chubet, R.; Holtz, K.; McPherson, C.; Petric, M.; Cox, M. A recombinant baculovirus-expressed S glycoprotein vaccine elicits high titers of SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 2006, 24(17), 3624–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folegatti, P.M.; Ewer, K.J.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Becker, S.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; Bellamy, D.; Bibi, S.; Bittaye, M.; Clutterbuck, E.A.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020, 396(10249), 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ella, R.; Reddy, S.; Jogdand, H.; Sarangi, V.; Ganneru, B.; Prasad, S.; Das, D.; Raju, D.; Praturi, U.; Sapkal, G.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBV152: interim results from a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 trial, and 3-month follow-up of a double-blind, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021, 21(7), 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashikawa, F.; Noda, M.; Awaya, T.; Tanaka, T.; Sugiyama, M. 5- aminolevulinic acid, a precursor of heme, reduces both fasting and postprandial glucose levels in mildly hyperglycemic subjects. Nutrition 2013, 29(7-8), 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saber, F.; Aldosari, W.; Alselaiti, M.; Khalfan, H.; Kaladari, A.; Khan, G.; Harb, G.; Rehani, R.; Kudo, S.; Koda, A.; et al. The safety and tolerability of 5- aminolevulinic acid phosphate with sodium ferrous citrate in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Bahrain. J Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 8294805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehani, P.R.; Iftikhar, H.; Nakajima, M.; Tanaka, T.; Jabbar, Z.; Rehani, R.N. Safety and mode of action of diabetes medications in comparison with 5-aminolevulinic acid (5- ALA). J Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 4267357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, B.L.; Curb, J.D.; Davis, J.; Shintani, T.; Perez, M.H.; ApauLudlum, N.; Johnson, C.; Harrigan, R.C. Use of the dietary supplement 5-aminiolevulinic acid (5-ALA) and its relationship with glucose levels and hemoglobin A1C among individuals with prediabetes. Clin Transl Sci. 2012, 5(4), 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).