1. Introduction

The Mitochondria are fundamental organelles in most eukaryotic cells, playing an essential role in producing cellular energy through the oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS). In addition, they are also involved in a wide range of metabolic pathways for amino acids, nucleotides and lipids, as well as the regulation of apoptosis and aging [

1,

2]. Given their central role in energy homeostasis and metabolic regulation, the dysfunction of mitochondria is associated with a variety of human diseases, ranging from neurodegenerative disorders to metabolic syndromes [

3,

4].

Mitochondria contain their own DNA (mtDNA), which encodes essential components required for mitochondrial gene expression and OXPHOS. In the fission yeast

Schizosaccharomyces pombe (

S. pombe), the ~19 kb mtDNA encodes seven core subunits of OXPHOS proteins, including Cob1 (subunit of complex III, also called Cytb), Cox1, Cox2 and Cox3 (subunits of complex IV), Atp6, Atp8 and Atp9 (subunits of ATP synthase). Additionally, the mtDNA encodes a mitochondrial ribosomal protein Var1, the RNA subunit of RNaseP (

rnpB), two rRNAs (

rns and

rnl) and 25 tRNAs. Unlike human mtDNA, both

S. pombe and

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (

S. cerevisiae) mtDNAs lack complex I but instead encode alternative NADH dehydrogenases [

5]. This distinct genomic organization highlights the evolutionary diversity of mitochondrial genomes and their functional adaptation to diverse cellular environments.

The mechanism of mitochondrial translation shares greater similarity with bacterial translation than with its cytosolic counterpart, as mitochondria are derived from bacteria [

6,

7]. Despite this evolutionary relationship, mitochondrial translation initiation also exhibits features that are distinct from bacterial systems. In bacteria, the translation initiation requires three essential initiation factors (IF1, IF2 and IF3), which facilitate the binding of the initiator to the mitochondrial ribosome. In contrast, translation initiation in mitochondria involves only two initiation factors (mtIF2 and mtIF3), as IF1, a universally essential component in bacterial and cytosolic translation, is notably absent in mitochondria [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Another difference between bacterial and mitochondrial translation initiation is the formylation of initiator tRNA. In

E. coli, the initiation of translation depends on a formylated initiator tRNA (fMet-tRNA

ifMet), whereas in mitochondria, translation initiates with non-formylated initiator tRNA. Like in mammals, formylation of Met-tRNA

ifMet in

S. cerevisiae enhances its affinity to mtIF2 [

12]. Another distinction in mitochondrial translation is the involvement of translational activators, which function in conjunction with initiation factors (IFs) to regulate mitochondrial gene expression. These activators play a crucial role in facilitating mitochondrial translation and often act in a mRNA-specific manner [

13]. In

S. cerevisiae, for instance, Sov1 is required for the translation of

VAR1. While Cbs1, Cbs2, Cbp1 and Cbp3-Cbp6 form a complex involved in the translation of

COB, Pet309 and Mss51 are critical for the translation of

COX1, ensuring efficient synthesis of its encoded protein [

6].

Despite possessing a conserved core fold, mitochondrial translation initiation factor 2 (mtIF2) is different from bacterial IF2 in several functional domains. A 37-amino-acid insertion domain, located between domains II and III, was identified through a cryo-EM structure study of the entire translation initiation complex from mammalian mitochondria; this domain extends toward the decoding center and adopts the form of an α-helix, stabilizing the binding of the leaderless mRNAs and causing conformational changes in the rRNA nucleotides [

14]. It has been suggested that the insertion domain of mtIF2 in vertebrate mitochondria performs a similar role to that of bacterial IF1 [

15,

16]. This insertion domain was first identified in bovine mtIF2, where mutations in this region dramatically impair the formation of the initiation complex and disrupt its association with the small subunit of the mitoribosome [

17,

18]. Similarly, in human MTIF2, this domain has been shown to enhance translation initiation efficiency by stabilizing the mitoribosome association and ensuring accurate start codon selection [

14]. The evolutionary and genetic analysis of mitochondrial translation initiation factors suggests that the mtIF2 insertion domain functionally compensates for the universal absence of IF1 in mitochondria and exhibits high variability in length without perturbing protein function and primary sequence conservation across vertebrates. Sequence analysis of mitochondrial translation initiation factors further demonstrates that the insertion domain has a strong bias on amino acid composition, particularly for glutamate and lysine. In the human MTIF2 insertion domain, glutamate and lysine account for 20.3% and 21.9%, respectively, a pattern also observed in fungal homologs, such as in

S. pombe and

S. cerevisiae [

19].

To investigate whether the insertion domain plays a similar functional role in fungal mitochondria, we investigated the insertion domain of Mti2 (the mtIF2 homolog in S. pombe). We predicted the structure of Mti2 both with and without the insertion domain and performed structure alignment, suggesting that the insertion domain is essential for the proper folding of Mti2. Additionally, functional assays demonstrated that the insertion domain is critical for mitochondrial function and the translation of mtDNA-encoded genes. Furthermore, we explored the physical interaction between Mti2 and the mitochondrial ribosomal subunits. Coimmunoprecipitation results confirmed that Mti2 physically interacts with the small subunits of mitoribosomes (mtSSU) rather than large subunits of mitoribosomes (mtLSU). Sucrose sedimentation analysis further indicated that the absence of the insertion domain disrupts the association of mitochondrial translation initiation factors to mtSSU, as well as the assembly of mitoribosome. These findings suggest that, similar to its role in mammalian mitochondria, the insertion domain of Mti2 in S. pombe plays a conserved role in promoting translation initiation by facilitating mitoribosome association and thus reveal shared principles of mitochondrial translation initiation in both fission yeast and humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Media

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in

Table S1. The Δ

mti2 strain was generated by homologous recombination using pFA6a-kanMX6 [

20]. The Δ

mti2 strain was verified by PCR using check primers. The schematic view of the construction of

mti2 deleting insertion domain (aa443-477) strain (referred to as

mti2Δ

insertion strain) is shown in

Figure S1. Briefly, the fragments of Mti2

1-442 and Mti2

478-686 were amplified by PCR; these two fragments were fused into one single fragment using overlapping PCR and subsequently integrated into XbaI/SmaI sites of pJK148 [

21]. The plasmid was then linearized with NruI and transformed into wild-type strain yHL6381. A strain expressing C-terminal tagged Mti2 was generated by integrating corresponding tagging cassette into endogenous

mti2 locus into strain yHL6381. The tagging cassette was generated via overlapping PCR. The

mti2Δ

insertion and Mti2-FLAG strains were verified by western blotting with primary antibody against Mti2 and FLAG, respectively.

S. pombe cells were cultured in rich Yeast Extract with Supplements medium (YES: 3% glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 225 mg/L adenine, histidine, leucine, uracil and lysine hydrochloride). The described standard protocols of

S. pombe were adhered to in this study [

22].

2.2. Prediction and Alignment of Protein Structure

The structure prediction of

S. pombe Mti2 and Mti2Δinsertion was conducted by AlphaFold 3 [

23] using default parameters (

https://alphafoldserver.com/). To evaluate whether the deletion of the insertion domain altered the structure of Mti2, TM-align was used for the comparison of protein structures and alignment [

24]. TM-align provides a TM-score to quantify structural similarity, with a TM-score <0.3 indicating random structural similarity, while scores ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 suggest that the two structures share a very similar fold. In contrast, a higher root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value reflects a significant structural difference between the compared models.

2.3. Real-Time Quantitative Yeast Growth Assays

The quantitative growth assays were performed using FlowerPlates in a BioLector microbioreactor (m2p-labs) as described [

25]. Briefly, the wild type,

mti2Δ

insertion, and Δ

mti2 strains were precultured in YES medium for 12 h, and then diluted to an OD

600 of 0.2 and grown to mid-exponential phase. Subsequently, cultures were further diluted to achieve an initial OD

600 of 0.02, and 1.5 mL cultures were incubated in triplicate at 32°C with 85% humidity and 1000 rpm shaking. The growth was measured every 10 min in until the cells reached stationary phase. The growth data were normalized to the initial time point (time 0) with the R package

shiny (

https://shiny.posit.co/), and mean growth curves were analyzed using

grofit [

26]. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA by

R (version 4.4.1) [

27,

28].

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

The wild type,

mti2Δ

insertion, Δ

mti2 strains were precultured in YES overnight at 32°C and then diluted to an initial OD

600 of 0.2 in fresh YES. Cells were collected after 6 hours, and total RNA was extracted using an E.Z.N.A. Yeast RNA Kit (OMEGA BIO-TEK), followed by reverse transcription using the HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme). qPCR was then performed using the SYBR Master Mix. All reactions were performed in triplicates. The Ct values were normalized against

act1 (actin) levels. Fold changes in mRNA levels of

mti2Δ

insertion and Δ

mti2 strains in comparison to wild type were analyzed by the 2

-∆∆Ct method. GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.1) was used to determine

p-values. The primers for qPCR are listed in

Table S2.

2.5. Isolation of Mitochondria and Western Blot Analysis

Crude mitochondria from

S. pombe were isolated using lysis enzymes derived from

Trichoderma harzianum (Sigma-Aldrich) as described [

29]. Briefly, cells were cultured overnight, harvested and enzymatically digested. The protoplasts were then disrupted using a Dounce tissue grinder (Sigma-Aldrich), and the crude mitochondria were subsequently collected by differential centrifugation. Mitochondrial proteins were detected by western blotting with the corresponding primary antibodies. Primary antibodies against anti-Cob1 (aa 256-268), anti-Cox1 (aa 524-537), anti-Cox2 (aa 149-162), anti-Cox3 (aa 123-136), anti-Atp6 (aa 2-21), anti-Mti2 (aa 667-686), anti-Mti3 (aa 214-233), anti-Mrp5 (aa 368-387), anti-Rsm24 (aa 239-258) anti-Mrpl16 (aa 37-54), and Mrpl40 (aa 32-50) were prepared as described [

30]. Hsp60 served as a loading control.

2.6. Immunoprecipitation Assay

Wild-type and Mti2-FLAG strains were precultured overnight at 32°C in YES medium, diluted to an initial OD

600 of 0.2 in fresh YES and grown to mid-exponential phase. Cells were harvested after 10 h culture and suspended in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCI, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM PMSF), and disrupted with glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) using the FastPrep-24 bead homogenizer. Proteins were precipitated with anti-FLAG beads. The beads were washed with binding buffer and wash buffer as previously described [

31]. Protein loading buffer (1x) was used to elute the bound proteins, and the samples were then incubated at 100°C for 5 min.

2.7. Sucrose Gradient Sedimentation Analysis

Sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis was conducted as previously described [

32,

33]. Briefly, 2 mg of mitochondria were suspended in 300 μL of lysis buffer and incubated for 25 min on ice. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation and loaded onto the top of a sucrose gradient for ultracentrifugation. Twelve fractions were collected from the bottom to the top (~350 μl per fraction). Proteins were precipitated by adding the same volume of 50% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The precipitates were then washed with ice-cold acetone, suspended in 1x protein loading buffer and detected by western blotting using corresponding primary antibodies.

3. Results

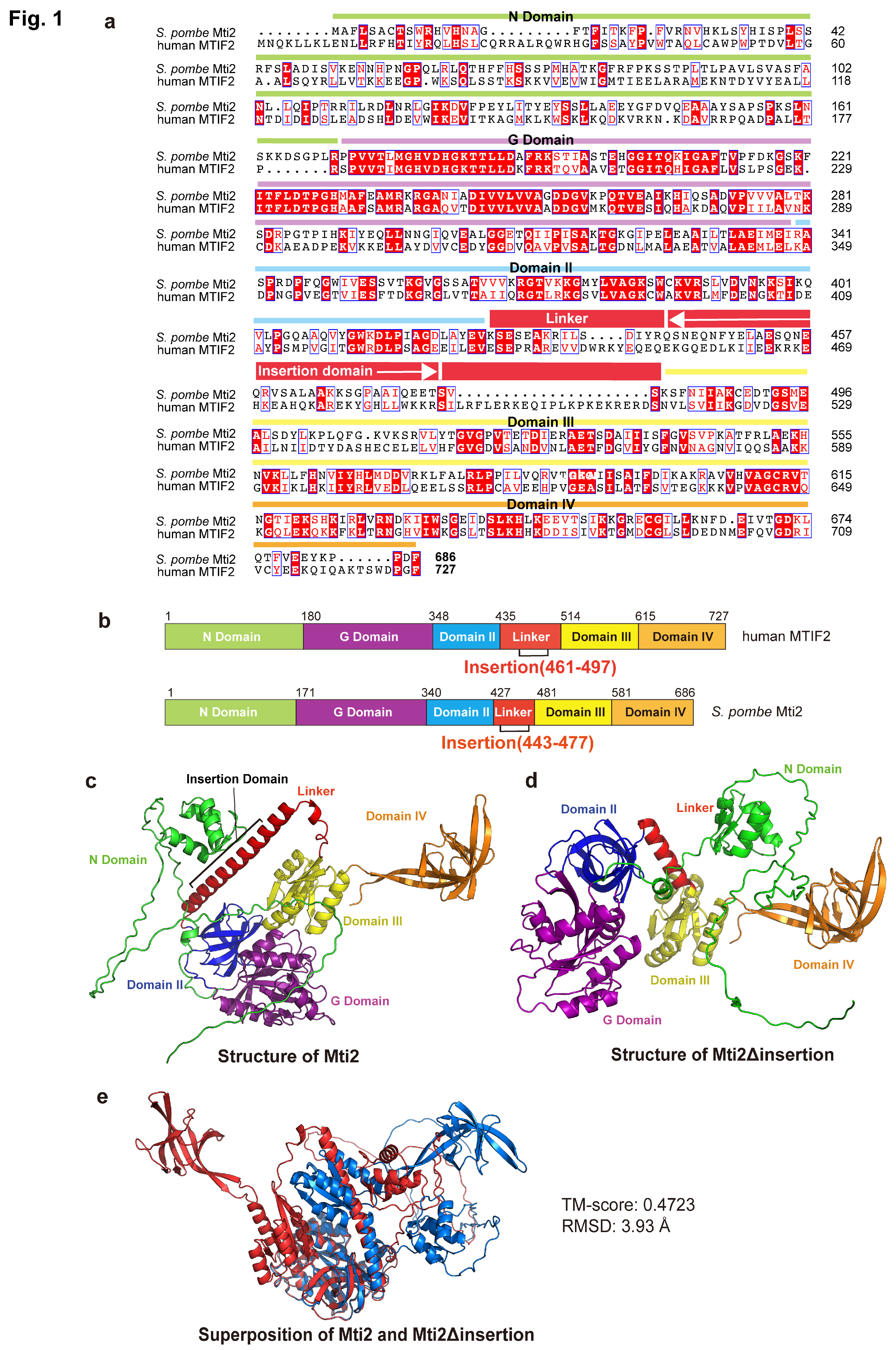

3.1. The Insertion Domain Is Required for Proper Folding of Mti2

To determine the insertion domain in

S.

pombe Mti2 that corresponds to the insertion domain of human MTIF2, a sequence alignment was performed between human MTIF2 and

S. pombe Mti2 (

Figure 1a). The domains of human MTIF2 were annotated following the framework described previously [

14], and the corresponding domains in

S. pombe Mti2 were identified (

Figure 1b). The G-domain is a structurally and functionally conserved domain responsible for GTP binding and hydrolysis, and plays a critical role in regulating protein synthesis during translation initiation, elongation, and termination [

34]. Domain II promotes initiator tRNA association to the small ribosomal subunit in a GTP-dependent manner during translation initiation [

35]. Domain III adopts a conserved

α/

β/

α structural fold, featuring a core parallel β-sheet that contributes to the proper binding of initiator tRNA to the P site [

36,

37]. Domain IV, characterized by a

β-barrel fold, facilitates conformational changes between GTP- and GDP-bound states [

37]. Like in human MTIF2, the insertion domain in Mti2 is located within the linker region between domain II and domain III (

Figure 1b). However, the sequence alignment indicates that the insertion domains of human MTIF2 and

S. pombe Mti2 exhibits low sequence similarity. This finding is consistent with the observation that the insertion domain varies greatly between species and is restrict in length [

19].

To explore the potential functional significance of the insertion domain in Mti2, we predicted the tertiary structures of Mti2 both with and without the insertion domain using AlphaFold3 [

23]. The ribbon patterns of tertiary structures revealed that the absence of the insertion domain resulted in significant alterations in protein folding. Using domain IV as a reference, notable shifts in the spatial arrangement of other domains were observed (

Figure 1c,d). The structural alignment of Mti2 with and without the insertion domain was subsequently performed by TM-align (

Figure 1e). The analysis yielded a TM-score of 0.47 and an RMSD of 3.93 Å, indicating a low degree of structural similarity. These structural predictions suggest that the absence of the insertion domain significantly disrupts the proper folding of Mti2, supporting its important role in Mti2 function.

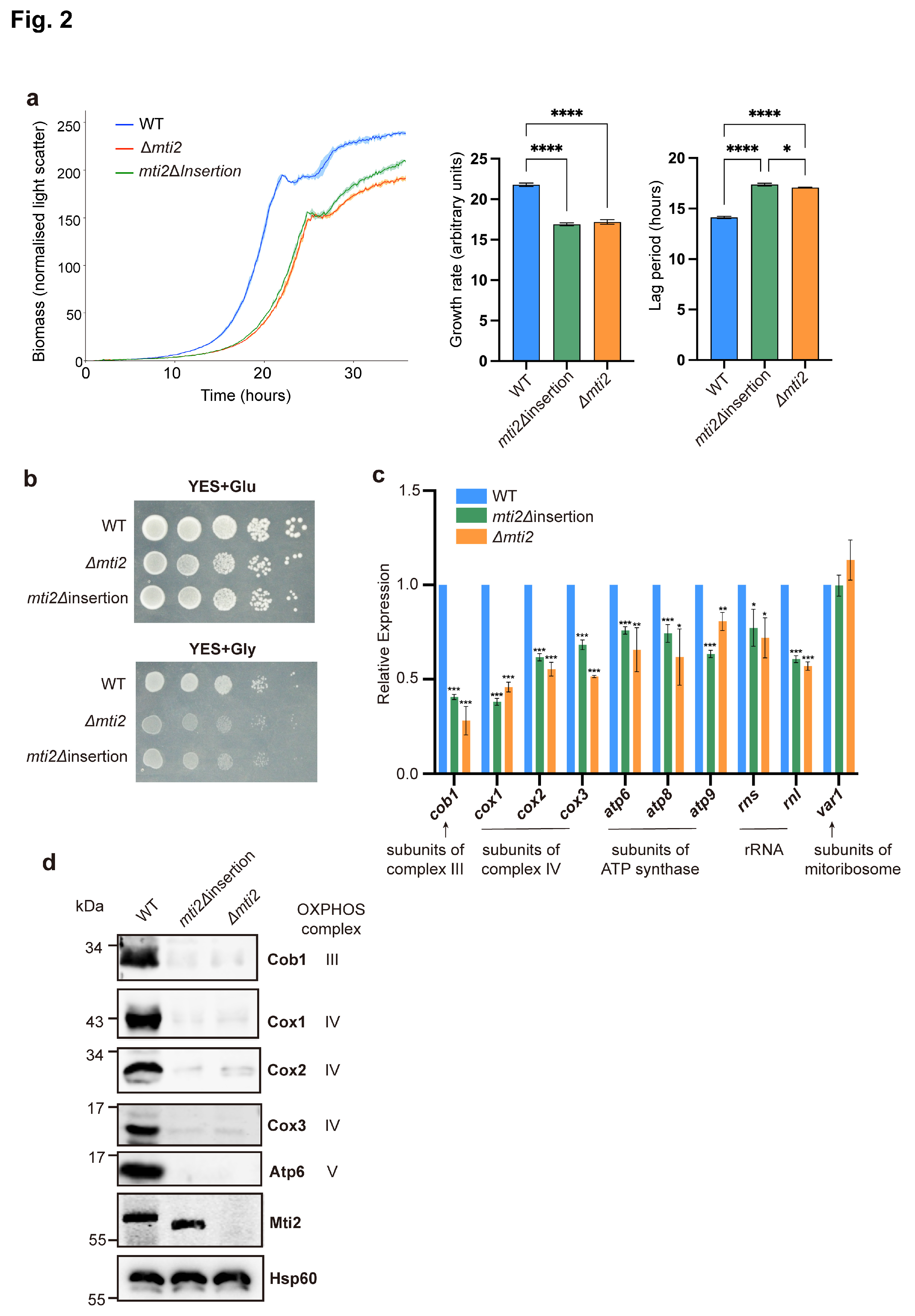

3.2. Deletion of the Insertion Domain Impairs Mti2 Function

To further investigate whether the deletion of the insertion domain affects the normal function of Mti2, we constructed a deletion strain of the entire

mti2 gene (Δ

mti2) and a deletion strain of the insertion domain only (

mti2Δ

insertion;

Figure S1). We examined whether these mutant strains impacted the growth of proliferating cells using a Biolector microbioreactor. The results revealed that both the

mti2Δ

insertion and Δ

mti2 cells exhibited reduced growth rates and prolonged lag phases compared to control cells (

Figure 2a). A spotting assay was then performed to assess cell growth under different carbon-source conditions. In glucose media,

S. pombe cells grow by fermentation with low mitochondrial respiratory demand, while in glycerol media, cells require high mitochondrial respiratory activity [

40]. Compared to wild-type cells, the growth of

mti2Δ

insertion and Δ

mti2 cells was only marginally reduced in glucose media but was significantly impaired in glycerol media (

Figure 2b). This result suggests that mitochondrial respiration is similarly inhibited in both mutants.

Mti2 is required for mitochondrial protein synthesis and normal levels of mtDNA-encoded proteins [

30]. To assess whether the insertion domain is required for the expression of mtDNA-encoded genes, we examined both RNA and protein levels of these genes in

mti2Δ

insertion cells using qPCR and western blotting, respectively. We found that

mti2Δ

insertion cells, similar to Δ

mti2 cells

, showed significantly reduced RNA levels of core subunits of respiratory chain complexes, including

cob1 (complex III),

cox1,

cox2 and

cox3 (complex IV),

atp6,

atp8 and

atp9 (ATP synthase). However, the RNA level of

var1, a mitochondrial ribosomal subunit encoded by mtDNA, remained stable in both mutants (

Figure 2c). Furthermore, both

mti2Δ

insertion and Δ

mti2 cells showed nearly abolished expression of the corresponding proteins (

Figure 2d). Collectively, these findings highlight the critical role of the insertion domain for Mti2 function and mitochondrial gene expression.

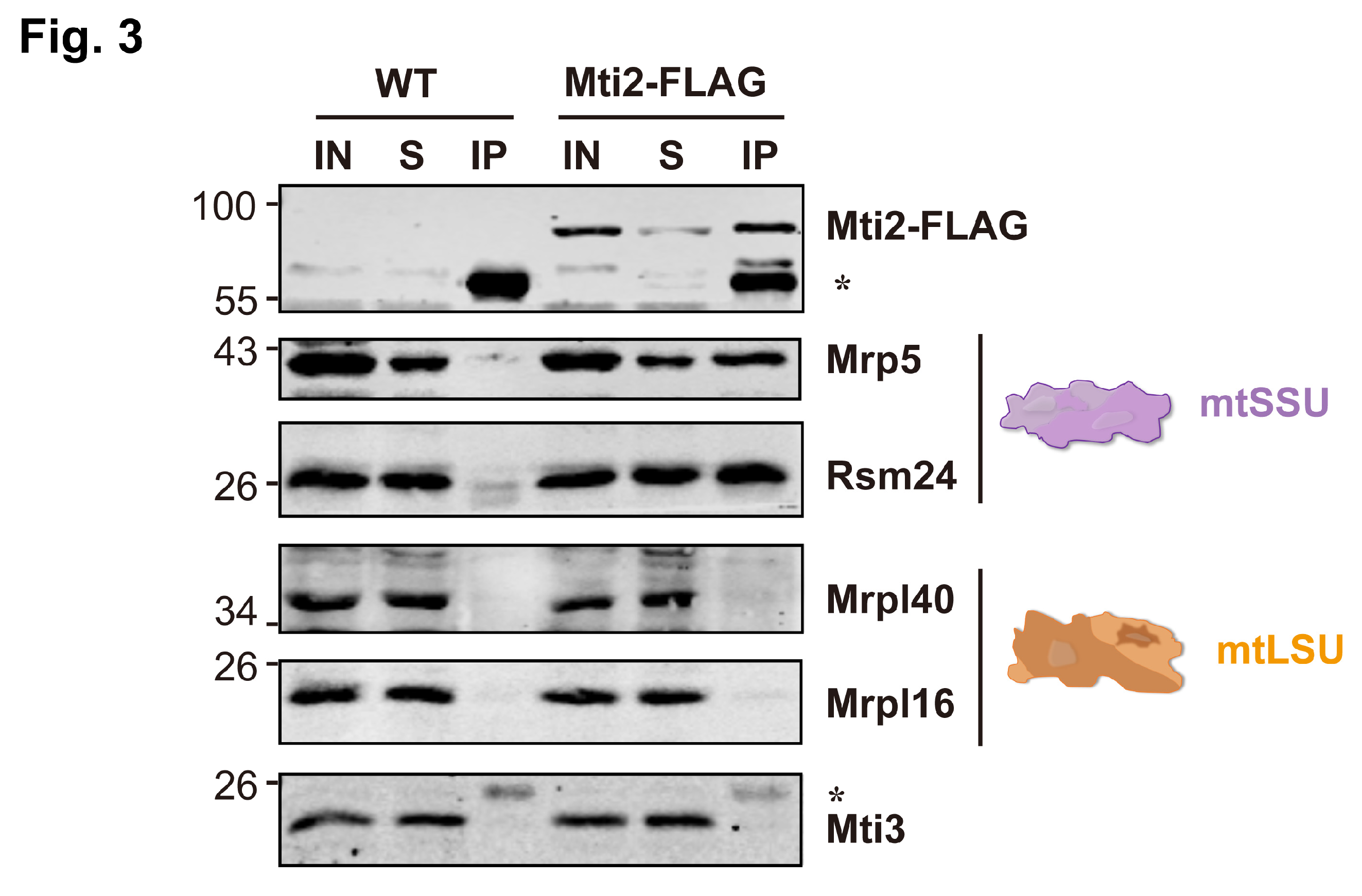

3.3. Mti2 Physically Interacts with the Small Mitoribosome Subunit

Previous studies have shown that Mti2 co-sediments with mtSSU in the same fractions using sucrose sedimentation analysis, suggesting its potential association with mtSSU [

30]. To investigate whether Mti2 physically interacts with the mtSSU, we generated an Mti2-FLAG tagged strain and performed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays. Our results revealed that the mtSSU, but not the mtLSU, specifically co-precipitated with Mti2-FLAG (

Figure 3). Moreover, no direct physical association was detected between the two mitochondrial translation initiation factors, Mti2 and Mti3. This finding provides direct evidence of a physical interaction between Mti2 and the mtSSU, reinforcing the model that Mti2 plays a direct role in mitochondrial translation initiation by associating with the mitoribosomes.

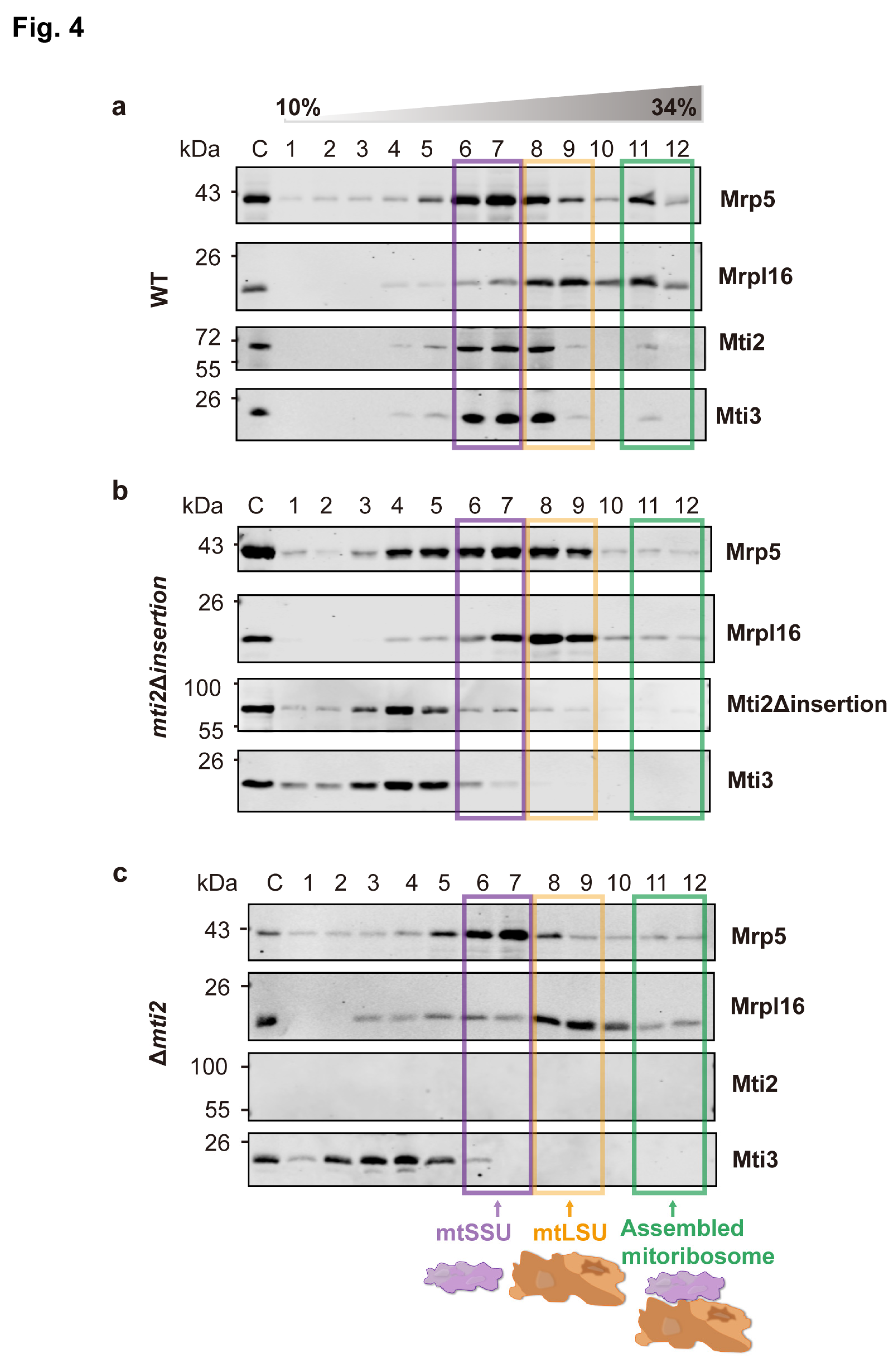

3.4. Deletion of the Insertion Domain Reduces the Affinity Between Mti2 and Mti3 and the mtSSU

Previous studies have shown that the insertion domain of human MTIF2 exhibits functional similarities to bacterial IF1, despite its distinct structural fold. The deletion of the insertion domain of MTIF2 leads to impaired translation efficiency in vitro [

14]. It is thought that the insertion domain facilitates mitochondrial translation by preventing premature entry of elongation factor tRNAs into the A-site and minimizing mRNA slippage, thereby ensuring accurate reading frame selection [

14].

To explore whether the insertion domain in

S. pombe plays a similar role in translation initiation, we conducted sucrose sedimentation analysis using wild-type,

mti2Δ

insertion, and Δ

mti2 cells. This approach enabled us to assess the effect of the insertion domain on the interaction between mitochondrial translation initiation factors and mitoribosomes. In wild-type cells, the mtSSU, mtLSU, and mitoribosome complexes were enriched in distinct fractions, with mitochondrial initiation factors co-sedimented with the mtSSU (

Figure 4a). Notably, deletion of the insertion domain resulted in the dissociation of translation initiation factors Mti2 and Mti3 from the mtSSU, and it significantly reduced their association with mitoribosomes (

Figure 4b), a phenotype similar to that observed in Δ

mti2 cells (

Figure 4c). These findings indicate that, like for MTIF2 in humans, the insertion domain in

S. pombe Mti2 promotes the efficiency of translation initiation by facilitating the association of initiation factors with the mitochondrial ribosome. We conclude that the insertion domain plays a conserved and crucial role in the function of MTIF2/Mti2 in mitochondrial translation in both fission yeast and humans, species that have diverged over a billion years ago.

4. Discussion

Mitochondrial translation initiation is a complex and highly regulated process that diverges significantly from its bacterial and cytosolic counterparts. While sharing a core mechanism with bacterial translation, mitochondria have evolved unique adaptations, including the use of methionyl-tRNA for both initiation and elongation and the absence of Shine-Dalgarno sequences. Another distinctive feature is the absence of IF1, which is universally present in other translation systems and increases the accuracy of the usage of tRNAs during elongation [

41]. The insertion domain of mtIF2 has been proposed to compensate for the absence of IF1 in vertebrates, suggesting that they may share a similar function in diverse eukaryotes [

14]. Phylogenetic and sequence analysis of mitochondrial translation initiation factors 2 showed that the insertion domain is only conserved in mammals [

17,

42], and full-length insertion domains are limited to vertebrates [

19]. However, whether the insertion domains play a similarly conserved role in other eukaryotes, particularly fungi, remains poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the functional significance of the insertion domain in Mti2, the mtIF2 homolog in

S. pombe. Our findings demonstrate that the insertion domain is crucial for Mti2 protein folding, mitochondrial respiration, and association of Mti2 with mitoribosomes. Together, these findings support the hypothesis that the insertion domain plays an important and conserved role in mitochondrial translation initiation.

We show that Mti2 physically interacts with the mtSSU to facilitate the initiation of mitochondrial protein translation (

Figure 3). Deletion of the insertion domain disrupts the association between mitochondrial initiation factors (Mti2 and Mti3) and the mtSSU (

Figure 4b). In human MTIF2, the deletion of the Trp-Lys-X-Arg motif, which is part of the insertion domain, severely impairs its function, suggesting that the insertion domain enhances the efficiency of translation initiation. This disruption is likely due to the loss of the insertion domain’s role in preventing premature binding of elongator tRNAs to the A-site and minimizing mRNA slippage to ensure accurate reading frame selection [

14]. According to the sequence alignment, the insertion domains share similar physicochemical properties that likely underlie their functional roles in mitochondrial translation initiation. However, the Trp-Lys-Lys-Arg motif in human MTIF2 and the Gln-Glu-Glu-Thr motif in

S. pombe Mti2 feature distinct amino acid sequences (

Figure 1a). Both motifs consist of highly polar and charged residues, which likely facilitate the interactions with ribosomal RNA and/or other components of the translational machinery, thereby ensuring efficient translation of leaderless mRNAs. Similarly, despite the low sequence identity of the insertion domains across species (

Figure 1a), their deletion results in impaired mitochondrial translation in different eukaryotes, highlighting their conserved functional importance.

This study provides fresh insights into the structural and functional role of the insertion domain in mitochondrial translation initiation, demonstrating its essential contributions to Mti2 stability, mitoribosome association, and translation efficiency in S. pombe. By establishing functional parallels between fungal and vertebrate mtIF2 insertion domains, our findings highlight a conserved adaptive mechanism compensating for the absence of IF1 in mitochondrial translation. These results broaden our understanding of the evolutionary divergence and conservation of mitochondrial translation mechanisms across eukaryotic species.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that the insertion domain of Mti2 plays a conserved and crucial role in Mti2 function and mitochondrial translation. This domain is required for the proper protein folding of Mti2, mitochondrial respiration, and efficient mitochondrial translation. Moreover, we show that Mti2 physically interacts with the mtSSU. Although the insertion domain of mtIF2 has been thought to be primarily conserved in vertebrates, our findings reveal that it performs a similar function in fission yeast, compensating for the absence of IF1 and facilitating translation initiation, which suggests a more widespread functional conservation across eukaryotes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org. Figure S1: The schematic view of the construction of mti2Δinsertion strain; Table S1: List of Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains used in this study; Table S2: List of primers used in this study; File S1: Original western blotting figures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., J.B. and Y.H.; visualization, Y.L. and J.B.; supervision, J.B. and Y.H.; funding acquisition, Y.L., J.B. and Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by China Scholarship Council (No. 202306860040 to Y.L.) and the Graduate Research and Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX23_1732 to Y.L.), a Wellcome Discovery Award (302608/Z/23/Z to J.B.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31770810 to Y.H.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Qinglong Yang and Xiao Yuan for their kind assistance during the preparation of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| mtSSU |

The small subunits of mitoribosomes |

| mtLSU |

The large subunits of mitoribosomes |

| mtDNA |

Mitochondrial genome |

| IF |

Initiation factors |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative real-time PCR |

| CoIP |

Co-immunoprecipitation |

References

- Rutter, J.; Hughes, A.L. Power2: The power of yeast genetics applied to the powerhouse of the cell. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somasundaram, I.; Jain, S.M.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Pathak, S.; Banerjee, A.; Rawat, S.; Sharma, N.R.; Duttaroy, A.K. Mitochondrial dysfunction and its association with age-related disorders. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1384966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boczonadi, V.; Horvath, R. Mitochondria: Impaired mitochondrial translation in human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 48, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, N.; Bonnefoy, N. Schizosaccharomyces pombe as a fundamental model for research on mitochondrial gene expression: Progress, achievements and outlooks. IUBMB Life 2023, 76, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmenko, A.; Atkinson, G.C.; Levitskii, S.; Zenkin, N.; Tenson, T.; Hauryliuk, V.; Kamenski, P. Mitochondrial translation initiation machinery: Conservation and diversification. Biochimie 2014, 100, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightowlers, R.N.; Rozanska, A.; Chrzanowska-Lightowlers, Z.M. Mitochondrial protein synthesis: Figuring the fundamentals, complexities and complications, of mammalian mitochondrial translation. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 2496–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, B.E.; Spremulli, L.L. Mechanism of protein biosynthesis in mammalian mitochondria. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Regul. Mech. 2012, 1819, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, E.; Ban, N. Mechanisms and regulation of protein synthesis in mitochondria. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Llácer, J.L.; Fernández, I.S.; Munoz, A.; Martin-Marcos, P.; Savva, C.G.; Lorsch, J.R.; Hinnebusch, A.G.; Ramakrishnan, V. Structural Changes Enable Start Codon Recognition by the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Complex. Cell 2014, 159, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, A.; Itoh, Y.; Remes, C.; Spåhr, H.; Yukhnovets, O.; Höfig, H.; Amunts, A.; Rorbach, J. Distinct pre-initiation steps in human mitochondrial translation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garofalo, C.; Trinko, R.; Kramer, G.; Appling, D.R.; Hardesty, B. Purification and characterization of yeast mitochondrial initiation factor 2. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 413, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, C.J.; Labarre-Mariotte, S.; Cornu, D.; Sophie, C.; Panozzo, C.; Michel, T.; Dujardin, G.; Bonnefoy, N. Translational activators and mitoribosomal isoforms cooperate to mediate mRNA-specific translation inSchizosaccharomyces pombemitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 11145–11166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, E.; Leibundgut, M.; Rackham, O.; Lee, R.G.; Boehringer, D.; Filipovska, A.; Ban, N. Unique features of mammalian mitochondrial translation initiation revealed by cryo-EM. Nature 2018, 560, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.S.; Haque, E.; Datta, P.P.; Elmore, K.; Banavali, N.K.; Spremulli, L.L.; Agrawal, R.K. Insertion domain within mammalian mitochondrial translation initiation factor 2 serves the role of eubacterial initiation factor 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 3918–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, R.; Grasso, D.; Datta, P.P.; Krishna, P.; Das, G.; Spencer, A.; Agrawal, R.K.; Spremulli, L.; Varshney, U. A Single Mammalian Mitochondrial Translation Initiation Factor Functionally Replaces Two Bacterial Factors. Mol. Cell 2008, 29, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, A.C.; Spremulli, L.L. The interaction of mitochondrial translational initiation factor 2 with the small ribosomal subunit. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 2005, 1750, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Farwell, M.A.; Burkhart, W.A.; Spremulli, L.L. Cloning and sequence analysis of the cDNA for bovine mitochondrial translational initiation factor 2. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gene Struct. Expr. 1995, 1261, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G.C.; Kuzmenko, A.; Kamenski, P.; Vysokikh, M.Y.; Lakunina, V.; Tankov, S.; Smirnova, E.; Soosaar, A.; Tenson, T.; Hauryliuk, V. Evolutionary and genetic analyses of mitochondrial translation initiation factors identify the missing mitochondrial IF3 in S. cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 6122–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bähler, J. ;Wu, J. Q.;Longtine, M. S.;Shah, N. G.;McKenzie, A., 3rd;Steever, A. B.;Wach, A.;Philippsen, P.;Pringle, J. R. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Yeast. 1998, 14, 943–51 101002/(sici)1097. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, J.B.; Boeke, J.D. Efficient targeted integration at leu1-32 and ura4-294 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 1994, 136, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, S.; Klar, A.; Nurse, P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991, 194, 795–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Skolnick, J. TM-Align: A protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anver, S.; Sumit, A.F.; Sun, X.-M.; Hatimy, A.; Thalassinos, K.; Marguerat, S.; Alic, N.; Bähler, J. Ageing-associated long non-coding RNA extends lifespan and reduces translation in non-dividing cells. Embo Rep. 2024, 25, 4921–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahm, M.; Hasenbrink, G.; Lichtenberg-Fraté, H.; Ludwig, J.; Kschischo, M. grofit: Fitting Biological Growth Curves with R. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisinger, C.; Pfanner, N.; Truscott, K. N. Isolation of yeast mitochondria. Methods Mol Biol. 2006, 313, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Su, R.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mti2 and Mti3 act in conjunction during mitochondrial translation initiation. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 4542–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ahmad, F.; Feng, G.; Huang, Y. Characterization of Shy1, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homolog of human SURF1. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Ppr10 and Mpa1 together mediate mitochondrial translational initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.; Barrientos, A. Sucrose Gradient Sedimentation Analysis of Mitochondrial Ribosomes. Methods Mol Biol. 2021, 2192, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipe, D.D.; I Wolf, Y.; Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. Classification and evolution of P-loop GTPases and related ATPases. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 317, 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laalami, S.; Sacerdot, C.; Vachon, G.; Mortensen, K.; Sperling-Petersen, H.; Cenatiempo, Y.; Grunberg-Manago, M. Structural and functional domains of E coli initiation factor IF2. Biochimie 1991, 73, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, S.K.; Roll-Mecak, A.; Burley, S.K.; Dever, T.E. Universal conservation in translation initiation revealed by human and archaeal homologs of bacterial translation initiation factor IF2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999, 96, 4342–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roll-Mecak, A.; Cao, C.; Dever, T.E.; Burley, S.K. X-Ray Structures of the Universal Translation Initiation Factor IF2/eIF5B. Cell 2000, 103, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2017, 27, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W320–W324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, A.; Gabrielli, N.; Calvo, I.A.; García-Santamarina, S.; Hoe, K.-L.; Kim, D.U.; Park, H.-O.; Hayles, J.; Ayté, J.; Hidalgo, E. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Increases Oxidative Stress and Decreases Chronological Life Span in Fission Yeast. PLOS ONE 2008, 3, e2842–e2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, A.; Pavlov, M.Y.; Lovmar, M.; Ehrenberg, M. How Initiation Factors Maximize the Accuracy of tRNA Selection in Initiation of Bacterial Protein Synthesis. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spremulli, L.L.; Coursey, A.;Navratil, T.;Hunter. Initiation and elongation factors in mammalian mitochondrial protein biosynthesis. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2004, 77, 211–261. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).