Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

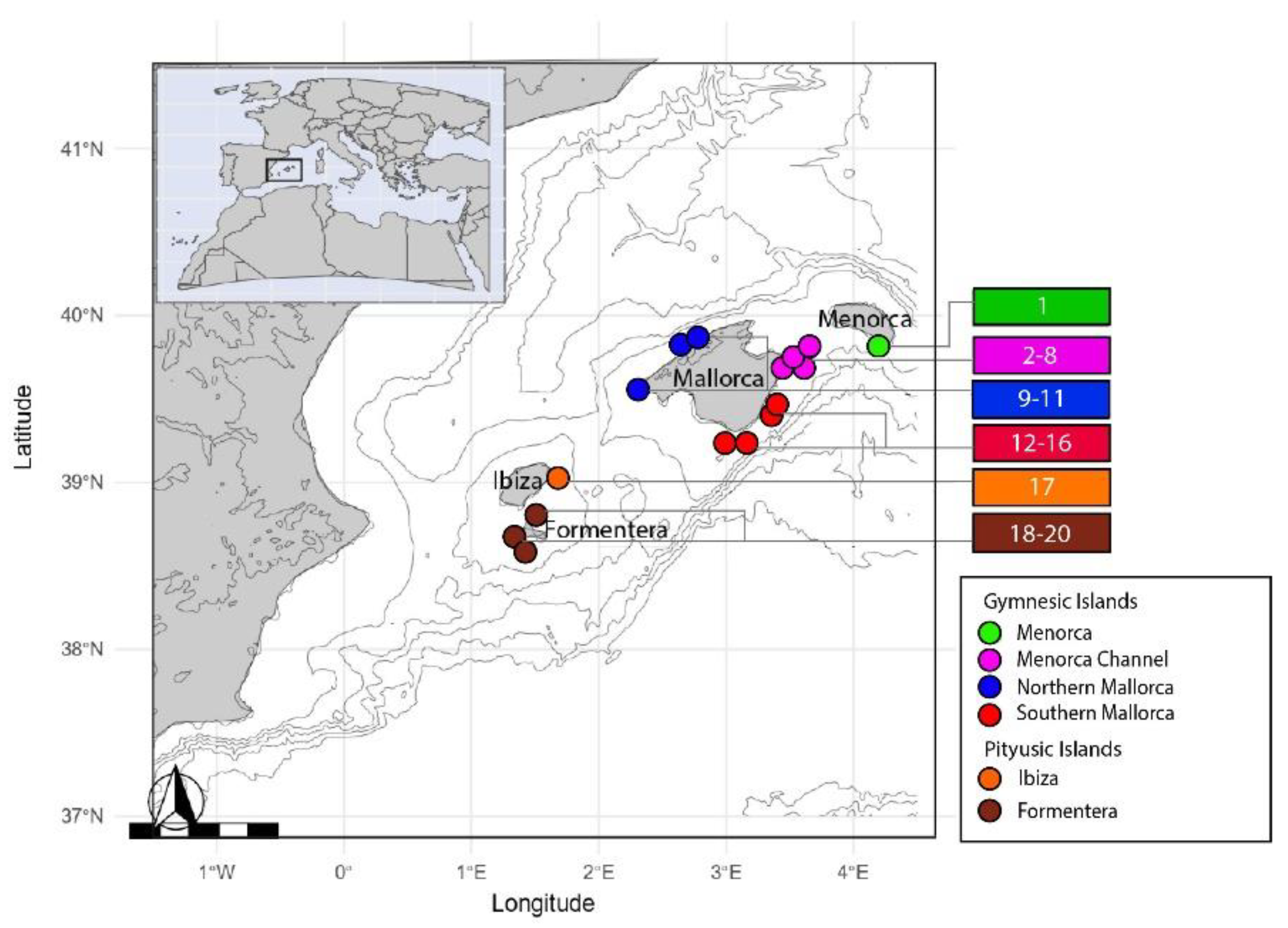

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling

2.3. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity

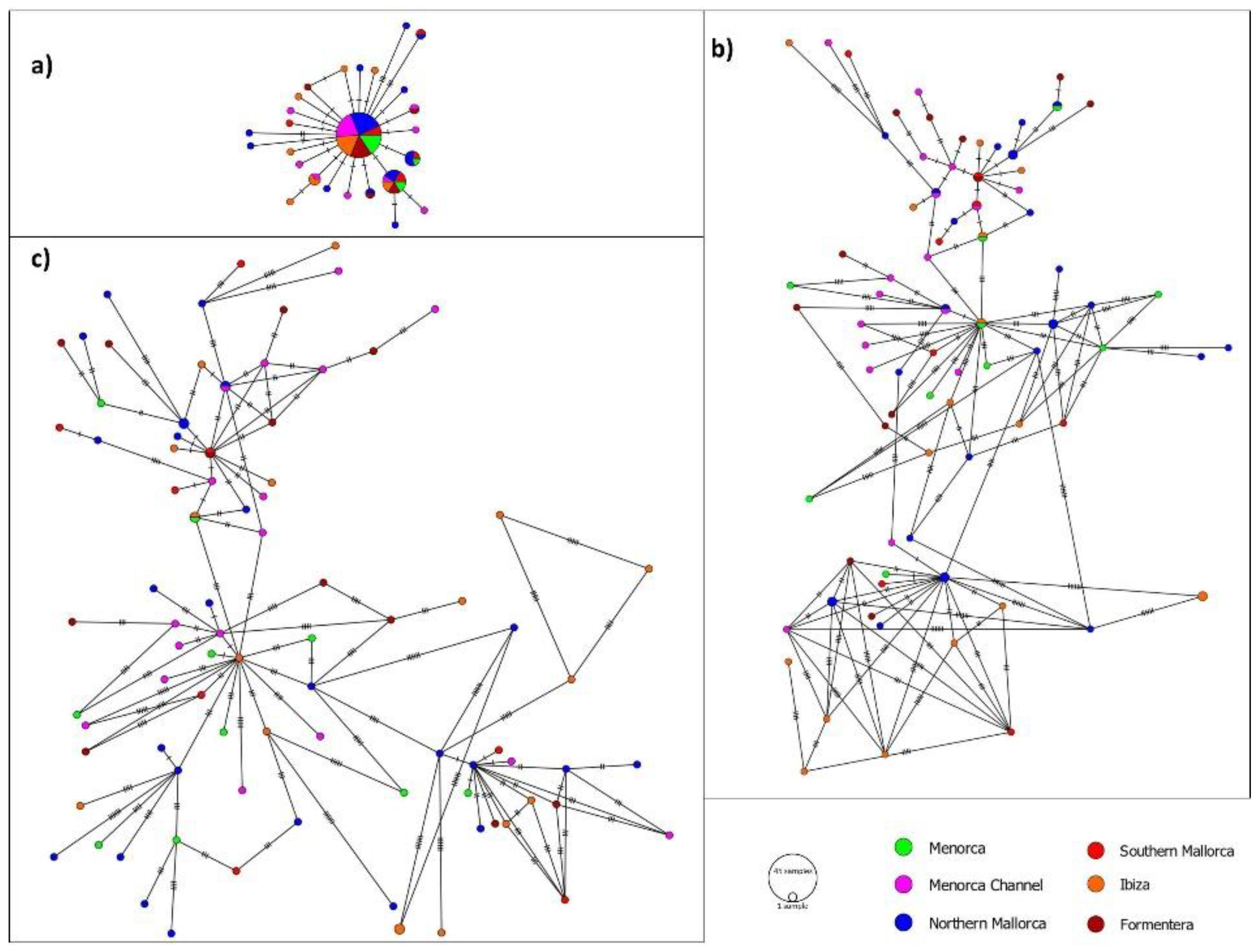

3.2. Genetic Differentiation and Connectivity

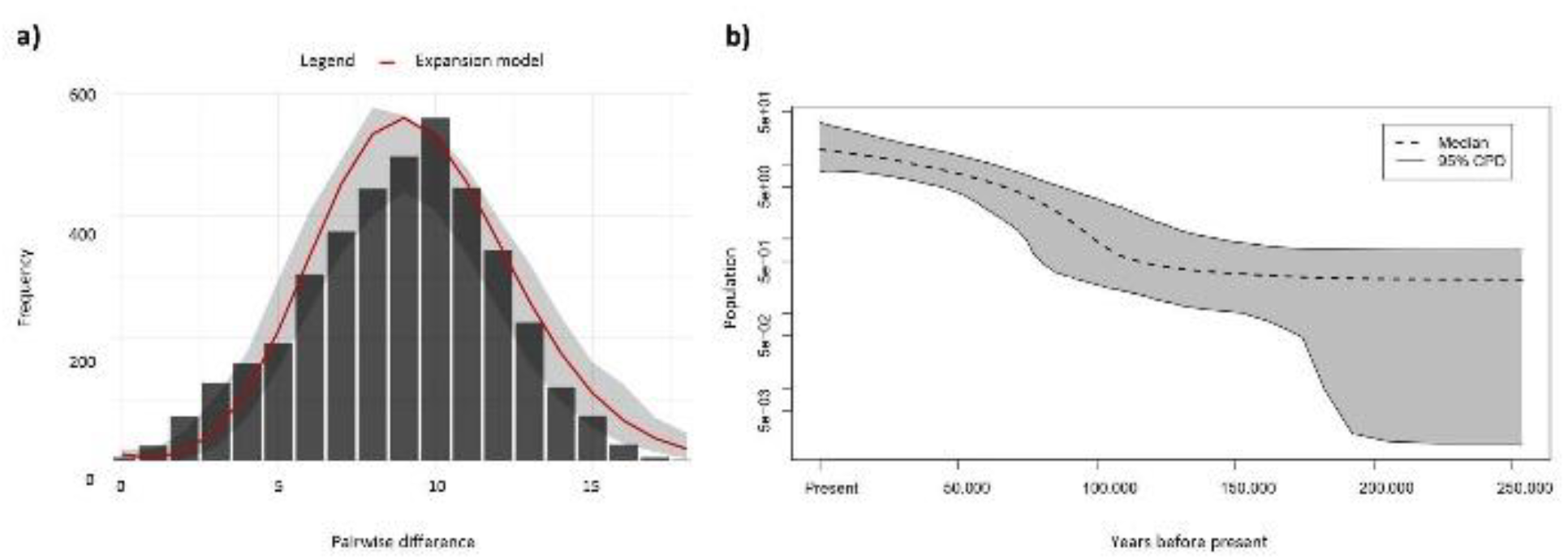

3.3. Population History

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMOVA | Analysis of Molecular Variance |

| BA | Balearic Archipelago |

| BSP | Bayesian Skyline Plot |

| COI | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I |

| CR | Control Region |

| EBSP | Extended Bayesian Skyline Plot |

| FOR | Formentera |

| Fst | Fixation Index |

| GI | Gymnesic Islands |

| IBI | Ibiza |

| LGM | Last Glacial Maximum |

| MCH | Menorca Channel |

| MCMC | Markov Chain Monte Carlo |

| MEDITS | Mediterranean International bottom trawl survey |

| MEN | Menorca |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| NML | Northern Mallorca |

| SML | Southern Mallorca |

References

- Pauls, S.U.; Nowak, C.; Balint, M.; Pfenninger, M. The impact of global climate change on genetic diversity within populations and species. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 925–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, K.A.; Toonen, R.J. Marine connectivity: a new look at pelagic larval duration and genetic metrics of dispersal. Mar. Ecol. Prog. 2011, 436, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, M.; Rives, B.; Schunter, C.; Macpherson, E. Impact of life history traits on gene flow: a multispecies systematic review across oceanographic barriers in the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS One 2017, 12(5), e0176419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quattrocchi, F.; Fiorentino, F.; Gargano, F.; Garofalo, G. The role of larval transport on recruitment dynamics of red mullet (Mullus barbatus) in the Central Mediterranean Sea Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202, 106814. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, O.P.; Aschan, M.; Rasmussen, T.; Tande, K.S.; Slagstad, D. Larval dispersal and mother populations of Pandalus borealis investigated by a Lagrangian particle-tracking model. Fish. Res. 2003, 65(1-3), 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basterretxea, G.; Jordi, A.; Catalan, I.A.; Sabatés, A.N.A. Model-based assessment of local-scale fish larval connectivity in a network of marine protected areas. Fish. Oceanogr. 2012, 21(4), 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Ahmad, N.A.H.; Ariffin, N.A.; Seah, Y.G.; Alam, M.M.M.; Jaafar, T.N.A.M.; Fadli, N.; Nor, S.A.M.; Rahman, M.M. Mitochondrial control region sequences show high genetic connectivity in the brownstripe snapper, Lutjanus vitta (Quoy and Gaimard, 1824) from the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. J. Genet. 2024, 103, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, S.; Andayani, N.; Muttaqin, E.; Simeon, B.M.; Ichsan, M.; Subhan, B.; Madduppa, H. Genetic connectivity of the scalloped hammerhead shark Sphyrna lewini across Indonesia and the Western Indian Ocean. PLoS One 2020, 15(10), e0230763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, S.M.; Castilho, R.; Lima, C.S.; Almada, F.; Rodrigues, F.; Šanda, R.; Vudić, J.; Pappalardo, A.M.; Ferrito, V.; Robalo, J.I. Genetic hypervariability of a Northeastern Atlantic venomous rockfish. PeerJ, 2021, 9, e11730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, M.A. Approximate Bayesian computation in evolution and ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 41, 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csillery, K.; Blum, M.G.B.; Gaggiotti, O.E.; Francois, O. Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) in practice. Trend. in Ecol. and Evol. 2010, 25, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, M.C.; Roland, K.; Calves, I.; Austerlitz, F.; Friso, F.P.; Tolley, K.A.; Ryan, S.; Ferreira, M.; Jauniaux, T.; Llavona, A.; Öztürk, B.; Öztürk, A.A.; Ridoux, V.; Rogan, E.; Sequeira, M.; Siebert, U.; Vikingsson, G.A.; Borrell, A.; Michaux, J.R.; Aguilar, A. Postglacial climate changes and rise of three ecotypes of harbour porpoises, Phocoena phocoena, in western Palearctic waters. Mol. Ecol. 2014, 23, 3306–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boissin, E.; Hurley, B.; Wingfield, M.J.; Vasaitis, R.; Stenlid, J.; Davis, C.; De Groot, P.; Ahumada, R.; Carnegie, A.; Goldarazena, A.; Klasmer, P.; Wermelinger, B.; Slippers, B. Retracing the routes of introduction of invasive species: the case of the Sirex noctilio woodwasp. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 5728–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanski, I. Metapopulation dynamics. Nature 1998, 396, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treml, E.A.; Halpin, P.N. Marine population connectivity identifies ecological neighbors for conservation planning in the Coral Triangle. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hureau, J.C.; Litvinenko, N.I. Scorpaenidae. In Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Bauchot, M.L.; Hureau, J.C.; Nielsen, J.; Tortonese, E. (Eds.).; UNESCO, Paris, 1986, Whitehead, P.J.P., pp. 1211-1229.

- Harmelin-Vivien, M.L.; Kaim-Malka, R.A.; Ledoyer, M.; Jacob-Abraham, S.S. Food partitioning among scorpaenid fishes in Mediterranean seagrass beds. J. Fish Biol. 1989, 34, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordines, F.; Massutí, E. Relationships between macro-epibenthic communities and fish on the shelf grounds of the western Mediterranean. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2009, 19(4), 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Sàbat, M.; Vila, S.; Casadevall, M. Annual reproductive cycle and fecundity of Scorpaena notata (Teleostei, Scorpaenidae). Sci. Mar. 2005, 69(4), 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordines, F.; Quetglas, A.; Massutí, E.; Moranta, J. Habitat preferences and life history of the red scorpion fish, Scorpaena notata, in the Mediterranean. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2009, 85, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.; Canals, M.; López-Martınez, J.; Munoz, A.; Herranz, P.; Urgeles, R.; Palomo, C.; Casamor, J.L. The Balearic Promontory Mediterranean international trawl survey (MEDITS). Aquat. Living Resour. 2002, 12, 207–217. [Google Scholar]

- Lehucher, P.M.; Beautier, L.; Chartier, M.; Martel, F.; Mortier, L.; Brehmer, P.; Millot, C.; Alberola, C.; Benzhora, M.; Taupierletage, I.; Dhieres, G.; Didelle, H.; Gleizon, P.; Obaton, D.; Crépon, M.; Herbaut, C.; Madec, G.; Sabrina, S.; Nihoul, J.; Harzallah, A. Progress from 1989 to 1992 in understanding the circulation of the Western Mediterranean Sea. Oceanol. Acta 1995, 18, 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Bosc, E.; Bricaud, A.; Antoine, D. Seasonal and interannual variability in algal biomass and primary production in the Mediterranean Sea, as derived from 4 years of SeaWiFS observations. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2024, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monserrat, S.; López-Jurado, J.L.; Marcos, M. (2008). A mesoscale index to describe the regional circulation around the Balearic Islands. J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 71(3-4), 413–420.

- Guijarro, B.; Fanelli, E.; Moranta, J.; Cartes, J.E.; Massutí, E. Small-scale differences in the distribution and population dynamics of pandalid shrimps in the western Mediterranean in relation to environmental factors. Fish. Res. 2012, 119-120, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, B.; Massutí, E.; Moranta, J.; Cartes, J.E. Short spatio-temporal variations in the population dynamics and biology of the deep-water rose shrimp Parapenaeus longirostris (Decapoda: Crustacea) in the western Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 2009, 73(1), 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, B.; Massutí, E.; Moranta, J.; Díaz, P. Population dynamics of the red-shrimp Aristeus antennatus in the Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean): spatio-temporal differences and influence of environmental factors. J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 71, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.; Massutí, E.; Moranta, J.; Cartes, J.E.; Lloret, J.; Oliver, P.; Morales-Nin, B. Seasonal and short spatial patterns in European hake (Merluccius merluccius L. ) recruitment process at the Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean): the role of environment on distribution and condition. J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 71, 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- Massutí, E.; Monserrat, S.; Oliver, P.; Moranta, J.; López-Jurado, J.L.; Marcos, M.; Hidalgo, M.; Guijarro, B.; Carbonell, A.; Pereda, P. The influence of oceanographic scenarios on the population dynamics of demersal resources in the western Mediterranean: hypothesis for hake and red shrimp off Balearic Islands. J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 71, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, L.; Moranta, J.; Abelló, P.; Balbín, R.; Barberá, C.; Fernández de Puelles, M.L.; Olivar, M.P.; Ordines, F.; Ramón, M.; Torres, A.P.; Valls, M.; Massutí, E. Body condition of the deep water demersal resources at two adjacent oligotrophic areas of the western Mediterranean and the influence of the environmental features. J. Mar. Syst. 2014, 138, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spedicato, M.T.; Massutí, E.; Mérigot, B.; Tserpes, G.; Jadaud, A.; Relini, G. The MEDITS trawl survey specifications in an ecosystem approach to fishery management. Sci. Mar. 2019, 83(S1), 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.V.; Zemlak, T.S.; Hanner, R.H.; Hebert, P.D.N. Universal primer cocktails for fish DNA barcoding. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostellari, L.; Bargelloni, L.; Penzo, E.; Patarnello, P.; Patarnello, T. Optimization of single-strand conformation polymorphism and sequence analysis of the mitochondrial control region in Pagellus bogaraveo (Sparidae, Teleostei): Rationalized tools in fish population biology. Anim. Genet. 1996, 27, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Bio. Evol. 2018, 35(6), 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34(12), 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Excoffier, L.; Lischer, H.E.L. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2010, 10, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D.; Nakagawa, S. POPART: full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6(9), 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. The genetical structure of populations. Ann. Eugen. 1951, 15, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, P.; Mashayekhi, S.; Sadeghi, M.; Khodaei, M.; Shaw, K. Population genetic inference with MIGRATE. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2019, 68, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Heled, J.; Kuhnert, D.; Vaughan, T.; Wu, C.; Xie, D.; Suchard, M.A.; Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J. BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, R.; Vaughan, T.G.; Barido-Sottani, J.; Duchêne, S.; Fourment, M.; Gavryushkina, A.; Heled, J.; Jones, G.; Kühnert, D.; De Maio, N.; Matschiner, M.; Mendes, F.K.; Müller, N.F.; Ogilvie, H.A.; Plessis, L.D.; Popinga, A.; Rambaut, A.; Rasmussen, D.; Siveroni, I.; Suchard, M.A.; Wu, C.; Xie, D.; Zhang, C.; Stadler, T.; Drummond, A.J. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2019, 15(4), e1006650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Yang, T.; Yanagimoto, T.; Gao, T. Comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genomes of three rockfishes (Scorpaeniformes, Sebastiscus) and insights into the phylogenetic relationships of Sebastidae. Biosc. Rep. 2020, 40(12), BSR20203379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, E.D.; Sbrocco, E.J.; DeBoer, T.S.; Barber, P.H.; Carpenter, K.E. Expansion dating: calibrating molecular clocks in marine species from expansions onto the Sunda Shelf following the Last Glacial Maximum. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, W.S.; Roy, A. Genetic diversity and population structure of brown croaker (Miichthys miiuy) in Korea and China inferred from mtDNA control region. Genes 2023, 14, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Suchard, M.A.; Xie, D.; Drummond, A.J. Tracer v1.6. 2014. Available online: http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer (accessed on 28 February of 2025).

- RStudio Team RStudio: Integrated Development for, R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 28 February of 2025).

- Petit-Marty, N.; Liu, M.; Tan, IZ.; Chung, A.; Terrasa, B.; Guijarro, B.; Ordines, F.; Ramírez-Amaro, S.; Massutí, E.; Schunter, C. Declining Population Sizes and Loss of Genetic Diversity in Commercial Fishes: A Simple Method for a First Diagnostic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 872537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, N.; Riera, J.; Tudurí, A.; Bassitta, M.; Ferragut, J.F.; Picornell, A.; Ramírez-Amaro, S. Estudios genéticos como una herramienta de diagnóstico para evaluar el efecto de las Zonas de Protección Pesquera en el Canal de Menorca sobre los recursos pesqueros demersales. In Proceedings of the XIV Reunión del Foro científico de pesca española en el mediterráneo, Palma, Spain, 20-21 septembre 2023; José Luis Sánchez Lizaso, Ed.; Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ordines, F.; Farriols, M.T.; Lleonart, J.; Guijarro, B.; Quetglas, A.; Massutí, E. Biology and population dynamics of by-catch fish species of the bottom trawl fishery in the western Mediterranean. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2014, 15(3), 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GFCM. Working Group on Stock Assessment of Demersal Species (WGSAD). Scientific Advisory Committee on Fisheries (SAC). General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM). 2024. Rome, Italy, 9-14 December 2024.

- Song, C.Y.; Sun, Z.C.; Gao, T.X.; Song, N. Structure analysis of mitochondrial DNA control region sequences and its applications for the study of population genetic diversity of Acanthogobius ommaturus. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2020, 46, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.B.D.; da Martins, K.C.P.; Júnior, J.N.S.; Moreira, E.C.O.; Sampaio, I.; Queiroz, C.C.S.; Leite, M.A.; de Souza, A.A.; dos Santos, C.A.; Vallinoto, M. High genetic diversity detected in the mitochondrial Control Region of the Serra Spanish Mackerel, Scomberomorus brasiliensis (Collette, Russo & Zavala, 1978) along the Brazilian coast. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2021, 32(5-8), 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.P.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Palumbi, S.R. Rates of mitochondrial DNA evolution in sharks are slow compared with mammals. Nature 1992, 357, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.; Carrillo, L.; Marinone, S.G. Potential connectivity between marine protected areas in the Mesoamerican Reef for two species of virtual fish larvae: Lutjanus analis and Epinephelus striatus. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, M.T.J.; Routman, E.J. Does population size affect genetic diversity? A test with sympatric lizard species. Heredity 2016, 116(1), 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunter, C.; Carreras-Carbonell, J.; Macpherson, E.; Tintoré, J.; Vidal-Vijande, E.; Pascual, A.; Guidetti, P.; Pascual, M. Matching genetics with oceanography: directional gene flow in a Mediterranean fish species. Mol. Ecol. 2011a, 20(24), 5167–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schunter, C.; Carreras-Carbonell, J.; Planes, S.; Sala, E.; Ballesteros, E.; Zabala, M.; Harmelin, J.G.; Harmelin-Vivien, M.; Macpherson, E.; Pascual, M. Genetic connectivity patterns in an endangered species: The dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol 2011b, 401(1-2), 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissin, E.; Micu, D.; Janczyszyn-Le, M.G.; Neglia, V.; Bat, L.; Todorova, V.; Panayotova, M.; Kruschel, C.; Macic, V.; Milchakova, N.; Keskin, Ç.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Nasto, I.; Zane, L.; Planes, S. Contemporary genetic structure and postglacial demographic history of the black scorpionfish, Scorpaena porcus, in the Mediterranean and the Black Seas. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 2195–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Amaro, S.; Picornell, A.; Arenas, M.; Castro, J.A.; Massutí, E.; Ramon, M.M.; Terrasa, B. Contrasting evolutionary patterns in populations of demersal sharks throughout the western Mediterranean. Mar. Biol. 2018, 165, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza, J.A.; Carreras-Carbonell, J.; Macpherson, E.; Pascual, M.; Roques, S.; Turner, G.F.; Rico, C. The influence of oceanographic fronts and early-life-history traits on connectivity among littoral fish species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106(5), 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.H.; Reed, D.C. Conceptual issues relevant to marine harvest refuges: examples from temperate reef fishes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1993, 50(9), 2019–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, E.; Raventós, N. Relationship between pelagic larval duration and geographic distribution of Mediterranean littoral fishes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 327, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jurado, J.L.; Marcos, M.; Monserrat, S. Hydrographic conditions affecting two fishing grounds of Mallorca island (western Mediterranean): during the IDEA project (2003-2004). J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 71, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggiotti, O.E.; Bekkevold, D.; Jørgensen, H.B.; Foll, M.; Carvalho, G.R.; Andre, C.; Ruzzante, D.E. Disentangling the effects of evolutionary, demographic, and environmental factors influencing genetic structure of natural populations: Atlantic herring as a case study. Evolution 2009, 63, 2939–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis-Santos, P.; Tanner, S.E.; Aboim, M.A.; Vasconcelos, R.P.; Laroche, J.; Charrier, G.; Pérez, M.; Presa, P.; Gillanders, B.M.; Cabral, H.N. Reconciling differences in natural tags to infer demographic and genetic connectivity in marine fish populations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoareau, T.B.; Boissin, E.; Berrebi, P. Evolutionary history of a widespread Indo-Pacific goby: the role of Pleistocene sealevel changes on demographic contraction/expansión dynamics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012, 62, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banguera-Hinestroza, E.; Evans, P.G.H.; Mirimin, L.; Reid, R.J.; Mikkelsen, B.; Couperus, A.S.; Deaville, R.; Rogan, E.; Hoelzel, A.R. Phylogeography and population dynamics of the white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus) in the North Atlantic. Conserv. Genet. 2014, 15, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, T.L.; Castilho, R.; Stevens, J.R. Meta-analysis of northeast Atlantic marine taxa shows contrasting phylogeographic patterns following post-LGM expansions. PeerJ. 2018, 6, e5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhs, D.R. Evidence for the timing and duration of the last interglacial period from high-precision uranium-series ages of corals on tectonically stable coastlines. Quat. Res. 2002, 58, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl-Jensen, D.; Albert, M.R.; Aldahan, A.; Azuma, N.; Balslev-Clausen, D.; Baumgartner, M.; Berggren, A.M.; Bigler, M.; Binder, T.; Blunier, T.; Bourgeois, J.C.; Brook, E.J.; Buchardt, S.L.; Buizert, C.; Capron, E.; Chappellaz, J.; Chung, J.; Clausen, H.B.; Cvijanovic, I.; Davies, S.M.; Ditlevsen, P.; Eicher, O.; Fischer, H.; Fisher, D.A.; Fleet, L.G.; Gfeller, G.; Gkinis, V.; Gogineni, S.; Goto-Azuma, K. Eemian interglacial reconstructed from a Greenland folded ice core. Nature 2013, 493, 489–494. [Google Scholar]

- Thunell, R.C. Pliocene-Pleistocene paleotemperature and paleosalinity history of the Mediterranean Sea: results from DSDP Sites 125 and 132. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1979, 4, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landini, W.; Sorbini, C. Evolutionary dynamics in the fish faunas of the Mediterranean basin during the Plio-Pleistocene. Quat. Int. 2005, 140(1), 64–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajewicz, U. Modeling mediterranean ocean climate of the last glacial maximum. Clim. Past. 2011, 7, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; Tanimura, M. The molecular clock runs more slowly in man than in apes and monkeys. Nature 1987, 326, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.Y.; Sharp, P.M.; Li, W.H. Mutation rate among regions of mammalian genome. Nature 1989, 337, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabholz, B.; Glémin, S.; Galtier, N. The erratic mitochondrial clock: variations of mutation rate, not population size, affect mtDNA diversity across birds and mammals. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.S.; Liu, M.; Gao, T.; Yanagimoto, T. Limits of Bayesian skyline plot analysis of mtDNA sequences to infer historical demographies in Pacific herring (and other species). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012, 65, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sampling Locations | COI | CR | Concatenated | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | N | S | h | Hd±SD | k | π±SD | S | h | Hd±SD | k | π±SD | S | h | Hd±SD | k | π±SD | |

| Menorca | MEN | 10 | 2 | 3 | 0.511±0.164 | 0.555 | 0.001±0.001 | 26 | 10 | 1.000±0.045 | 6.933 | 0.025±0.014 | 28 | 10 | 1.000±0.045 | 7.489 | 0.009±0.005 |

| Menorca Channel | MCH | 17 | 8 | 9 | 0.735±0.117 | 1.044 | 0.002±0.001 | 30 | 17 | 1.000±0.020 | 6.787 | 0.024±0.014 | 38 | 17 | 1.000±0.020 | 7.949 | 0.010±0.005 |

| Northern Mallorca | NML | 26 | 16 | 12 | 0.812±0.072 | 1.631 | 0.003±0.002 | 34 | 22 | 0.988±0.014 | 7.231 | 0.026±0.014 | 50 | 25 | 0.997±0.012 | 8.861 | 0.011±0.006 |

| Southern Mallorca | SML | 8 | 6 | 5 | 0.857±0.108 | 1.679 | 0.003±0.002 | 21 | 8 | 1.000±0.063 | 7.714 | 0.028±0.016 | 27 | 8 | 1.000±0.063 | 9.393 | 0.011±0.007 |

| Gymnesic Islands | GI | 61 | 24 | 20 | 0.741±0.057 | 1.279 | 0.002±0.002 | 57 | 53 | 0.996±0.004 | 7.156 | 0.026±0.014 | 82 | 59 | 0.999±0.003 | 8.468 | 0.010±0.005 |

| Ibiza | IBI | 17 | 7 | 8 | 0.779±0.099 | 1.118 | 0.002±0.002 | 32 | 16 | 0.993±0.023 | 8.500 | 0.031±0.017 | 39 | 16 | 0.993±0.023 | 9.618 | 0.012±0.006 |

| Formentera | FOR | 12 | 4 | 5 | 0.667±0.141 | 0.803 | 0.001±0.001 | 31 | 12 | 1.000±0.034 | 8.848 | 0.032±0.018 | 35 | 12 | 1.000±0.034 | 9.651 | 0.012±0.006 |

| Pityusic Islands | PI | 29 | 9 | 11 | 0.724±0.086 | 0.988 | 0.002±0.001 | 49 | 28 | 0.998±0.010 | 8.788 | 0.032±0.017 | 58 | 28 | 0.998±0.010 | 9.776 | 0.012±0.006 |

|

TOTAL Balearic Archipelago |

BA | 90 | 29 | 26 | 0.732±0.048 | 1.187 | 0.002±0.002 | 71 | 78 | 0.997±0.002 | 7.666 | 0.028±0.014 | 101 | 85 | 0.999±0.002 | 8.871 | 0.011±0.005 |

| Source of Variation | df | Sum of Squares | Variance Component | % of Variation | FST | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among groups | 1 | 3.872 | -0.03029 | -0.68 | ||

| Among locations within groups | 4 | 19.938 | 0.04019 | 0.91 | ||

| Within sampling locations | 84 | 370.957 | 4.41615 | 99.78 | 0.00224 | 0.21017 |

| TOTAL | 89 | 394.767 | 4.42606 | 100.00 |

| Tajima’s D | Fu’s Fs | Fu and Li’s D | Fu and Li’s F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COI | -2.462** | -30.563*** | -5.167** | -4.936** |

| CR | -1.675ns | -33.479*** | -2.961* | -2.918* |

| Concatenated | -1.963* | -121.701*** | -3.989** | -3.773** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).