Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Mapping the Landscape: Domains and Applications of DL in Agriculture

A. Precision Crop Management

- Plant Disease and Pest Detection: Crop diseases and pests pose a significant threat to global food security, causing substantial yield losses annually (Benos et al., 2021; Kamilaris and Prenafeta-Boldú, 2018). Early and accurate detection is paramount for effective management (Benos et al., 2021). DL models, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have demonstrated remarkable success in analyzing visual data (images of leaves, stems, fruits) captured from various platforms (handheld devices, drones, fixed sensors) to identify and classify a wide range of diseases and pests (Mukherjee, 2025). Specific examples include identifying diseases in cucumbers (Berdugo et al., 2014), tomatoes (Fuentes et al., 2017), apples (Ren et al., 2020), bananas (Selvaraj et al., 2019), soybeans and recognizing pests in cotton (Wang et al., 2022). Beyond simple classification, some DL models can quantify the severity of infection or be integrated with IoT systems to provide timely alerts to farmers (Albahar, 2023).

- Weed Detection and Management: Weeds compete with crops for resources, significantly impacting yield and quality (Murad et al., 2023). DL techniques, primarily CNNs, are employed to distinguish weeds from crops based on image analysis (Mukherjee, 2025). This capability enables precision agriculture approaches like site-specific herbicide application through intelligent sprayers or targeted mechanical/laser weeding by agricultural robots (Aixa Lacroix, 2024). Such targeted interventions drastically reduce overall chemical usage, benefiting both the environment and farm economics (Murad et al., 2023). Semantic segmentation models can precisely map weed locations within a field, and ongoing research compares different object detection models like YOLO variants for optimal real-time performance in field conditions (Allmendinger et al., 2025).

- Yield Prediction: Forecasting crop yield is a critical yet inherently complex task in agriculture, influenced by numerous interacting factors(Bali and Singla, 2022). Accurate predictions aid farmers in making informed decisions regarding harvest logistics, storage, marketing, and resource management (Benos et al., 2021). DL models, including CNNs, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs, particularly LSTMs for temporal data), and hybrid architectures, are increasingly used to analyze diverse data streams – such as satellite or drone-based remote sensing imagery, historical weather patterns, soil property data, and past yield records – to generate yield forecasts (Mukherjee, 2025). These techniques have been applied to major crops like wheat, maize (Oikonomidis et al., 2023), soybeans(Sun et al., 2019) , rice (Jeong et al., 2022), corn (Abbas et al., 2021), as well as various fruits (Benos et al., 2021).

- Fruit Counting and Detection: Automated counting and detection of fruits on trees or plants are essential for accurate pre-harvest yield estimation and optimizing harvest management strategies (Mukherjee, 2025). DL-based object detection models (e.g., Faster R-CNN, YOLO, Inception-ResNet) and custom CNNs are trained to identify and count fruits like apples (Fu et al., 2020), citrus (Khattak et al., 2021), mangoes (Pathak et al., 2024) or video footage captured in orchards and fields (Farjon et al., 2023). Density estimation techniques, which predict a map of object density rather than individual instances, also serve as an alternative approach for counting (Agrawal and Kumar, 2025).

- Crop Monitoring and Phenotyping: DL facilitates continuous monitoring of crop status throughout the growing season. This includes assessing overall crop health, identifying different growth stages, monitoring nutrient levels (e.g., nitrogen status), and detecting abiotic stresses such as water deficit, salinity, or heat stress (Benos et al., 2021). DL algorithms process data acquired from various sensors mounted on drones, satellites, or ground platforms (Mukherjee, 2025). High-throughput plant phenotyping, leveraging DL for analyzing observable traits, accelerates crop breeding programs by automating the assessment of characteristics like disease resistance or yield potential (Wang et al., 2022).

- Seed Classification and Quality Assessment: DL, particularly CNNs, can enhance the efficiency and accuracy of classifying different seed types or assessing seed quality (Mukherjee, 2025). Related applications include estimating the number of seeds per pod in crops like soybeans, which is relevant for yield component analysis (Katharria et al., 2024).

B. Precision Livestock Farming (PLF)

- Animal Health and Welfare Monitoring: DL models analyze data from wearable sensors (e.g., accelerometers tracking movement) or video cameras to monitor animal health and behavior patterns (Chintakunta et al., 2023). Detecting deviations from normal behavior can serve as an early indicator of health issues, such as lameness in dairy cows or subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), enabling timely intervention and improving animal welfare (Espinel et al., 2024).

- Behavior Analysis: ML and DL models (including RF, SVM, LDA, KNN, DT, MLP, LSTM) are used to automatically classify specific animal behaviors like grazing, resting, ruminating, or feeding from sensor data (Murad et al., 2023). Understanding behavior patterns is crucial for assessing welfare and optimizing management (Keskes and Nita, 2024).

- Optimizing Production: By monitoring individual animal data such as feed intake, growth rates, and environmental conditions, DL models can help optimize feeding strategies, predict growth trajectories, and inform breeding decisions(Xuan et al., 2025). Remote counting technologies can also aid in livestock inventory management (Farjon et al., 2023). Applications extend to aquaculture, such as fish detection and monitoring in recirculating systems (Lakhiar et al., 2024).

C. Intelligent Soil and Water Management

- Soil Analysis and Management: DL models (regression techniques, CNNs, XGBoost, RF, ANNs) are used to predict key soil properties, including soil moisture content, organic matter levels, nutrient availability (N, P, K), pH, salinity, and bulk density (Mukherjee, 2025). These predictions often leverage data fusion, combining inputs from soil sensors, remote sensing platforms (satellite/drone imagery), weather data, and techniques like Time Domain Reflectometry (Awais et al., 2023). DL can also contribute to assessing overall soil health and identifying microbial indicators associated with soil-borne diseases (Chintakunta et al., 2023). Transformer-based models have shown particular strength in fusing multi-source remote sensing data for accurate soil analysis (Saki et al., 2024).

- Water Management and Precision Irrigation: Efficient water use is crucial. DL algorithms help optimize irrigation scheduling by predicting crop water requirements based on factors like soil moisture measurements (from sensors or predicted by models), weather forecasts, evapotranspiration estimates, and crop growth stage(Mujahid Tabassum, 2024). Models employed include CNNs, decision trees, and integrated IoT-DL systems (Lakhiar et al., 2024). DL can also be used to detect leaks in irrigation infrastructure by analyzing flow and pressure data (Alina P., 2024), assess water stress levels in crops using remote sensing data, and even contribute to broader water resource management through forecasting lake water levels or flood risks (Chintakunta et al., 2023).

D. Emerging Application Frontiers

- Precision Spraying: Moving beyond simple detection, DL combined with computer vision and XAI is being developed to evaluate the effectiveness of precision spraying systems after application, quantifying spray deposition on targets (crops vs. weeds) without relying solely on traditional, labor-intensive methods like water-sensitive papers or fluorescent tracers. This allows for better calibration and verification of systems designed to minimize chemical use (Rogers et al., 2024).

- Automated Harvesting: DL-powered object detection (e.g., using YOLO models) is a key component in robotic harvesting systems, enabling robots to accurately identify and locate ripe fruits or vegetables for picking (Mukherjee, 2025).

- Agricultural Robotics: AI, particularly DL, is the "brain" behind increasingly sophisticated agricultural robots designed for autonomous tasks such as planting, targeted weeding (including non-chemical methods like laser weeding (Lacroix, 2024), precision spraying, field monitoring, and harvesting (Rane et al., 2024). Vision Transformers are being explored for tasks like multi-object tracking to enhance robotic perception in complex field environments (Sapkota and Karkee, 2024).

- Supply Chain and Traceability: DL has potential applications in improving the efficiency, transparency, and safety of agricultural supply chains, for instance, by tracking products from farm to consumer (Saiwa, 2016).

III. The Technological Toolkit: DL Architectures and Methodologies

A. Foundational Architectures

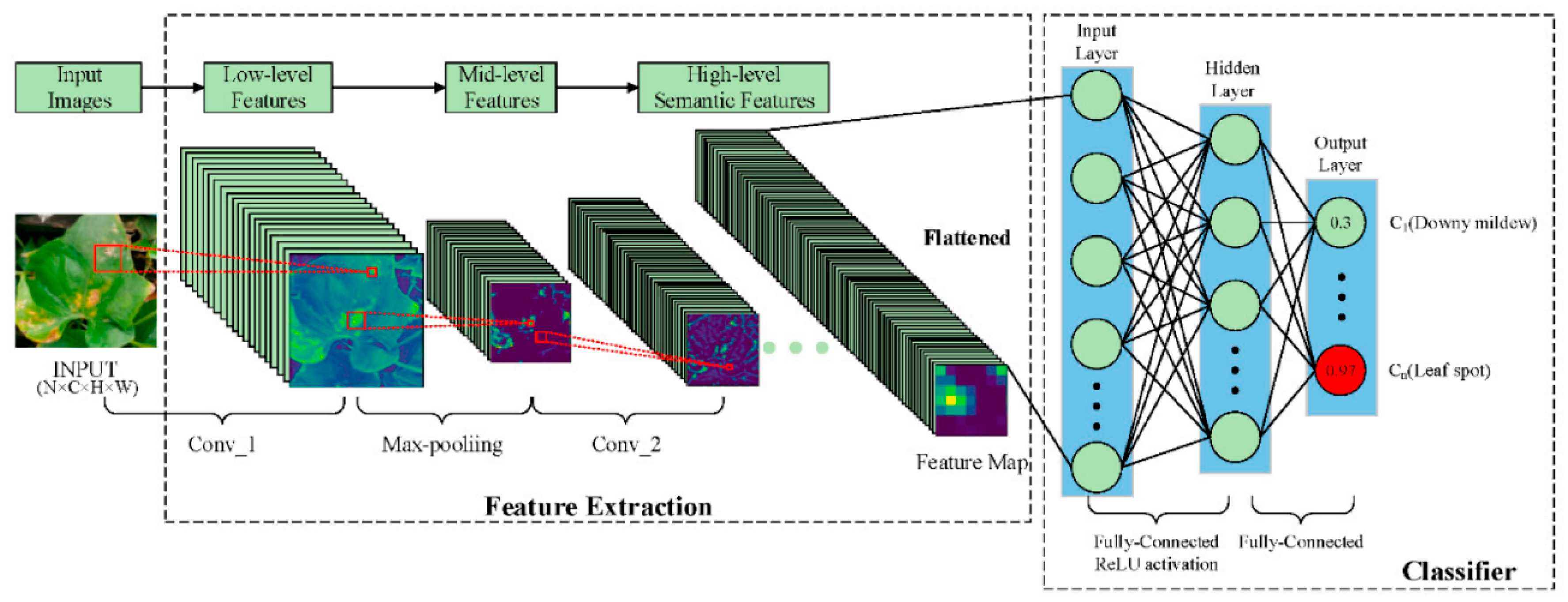

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): CNNs are unequivocally the dominant architecture in agricultural DL, particularly for tasks involving image data (Mukherjee, 2025). Their inherent ability to automatically learn spatial hierarchies of features (from simple edges and textures to complex object parts) makes them exceptionally well-suited for analyzing visual information from crops, soil, and livestock (Hashemi-Beni and Gebrehiwot, 2020). Consequently, CNNs are widely applied in plant disease (Figure 2) and pest detection, weed identification, fruit counting and localization, crop type classification from remote sensing imagery, and even soil property estimation when derived from visual or spectral image data (Farjon et al., 2023).

- Specific CNN Variants: A vast array of specific CNN architectures, often originating from broader computer vision research, have been adapted for agriculture(Awais et al., 2023). Table 1 provides an overview of the diverse CNN architectures that have been adapted from mainstream computer vision research for agricultural applications. It highlights foundational, deep, efficient, and specialized models, including segmentation networks and hybrid approaches, demonstrating the breadth of CNN use across different agricultural tasks.

| Category | Model Examples | Purpose/Notes | References |

| Foundational CNNs | AlexNet, VGG-16, GoogLeNet | Early deep learning models applied to agricultural tasks | Awais et al., 2023; Thakur et al., 2024 |

| Deep Architectures | ResNet-50, ResNet-101, ResNet-152V2, InceptionV3, Inception-ResNet | Better feature extraction through deeper or hybrid designs | Seyrek and Yiğit, 2024; Szegedy et al., 2017 |

| Lightweight/Edge Models | MobileNetV2, EfficientNet-B0 | Designed for mobile/edge deployment, low computational cost | Kulkarni et al., 2021 |

| Object Detection Models | Faster R-CNN, R-FCN, SSD, YOLOv3–YOLOv11 | Detection of fruits, weeds, pests; real-time applications | Jiang and Learned-Miller, 2017; Sharma et al., 2024 |

| Segmentation Networks | U-Net, SegNet, Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) | Pixel-level classification and delineation tasks | Farjon et al., 2023 |

| Specialized Networks | CountNet, DeepCorn | Object counting, kernel analysis in crops | Farjon et al., 2023 |

| Hybrid Approaches | PlantViT (CNN + Transformer) | Combines spatial feature learning and attention mechanisms | Sapkota and Karkee, 2024 |

- Object Detection Comparison (YOLO vs. Faster R-CNN): Table 2 compares two of the most prominent object detection models—YOLO and Faster R-CNN—within the context of agricultural applications. The table outlines their architectural differences, performance trade-offs, and suitability for tasks such as weed detection, fruit identification, and real-time drone-based monitoring.

| Criteria | YOLO (You Only Look Once) | Faster R-CNN | References |

| Detection Type | One-stage detector | Two-stage detector | Mohyuddin et al., 2024; Ren et al., 2017 |

| Speed | High; suitable for real-time (e.g., drones, robotic weeding) | Slower due to sequential proposal and classification | Sharma et al., 2024 |

| Accuracy | Improved in recent versions (YOLOv9–YOLOv11) | Often higher for small or overlapping objects | Kanna S et al., 2024; Gui et al., 2025 |

| Architecture | Single pass: localization + classification | RPN for region proposal + separate classification stage | Ren et al., 2017 |

| Strengths | Speed, edge-device suitability, now competitive accuracy | Superior for varied object sizes and complex scenes | Badgujar et al., 2024 |

| Recent Improvements | YOLOv9–YOLOv11: Enhanced accuracy while preserving speed | Enhanced FPN and RPN in newer variants | Santos Júnior et al., 2025; Liao et al., 2025 |

| Use Cases in Agriculture | Weed detection, fruit detection, SAR imagery analysis | Detailed object analysis requiring precision | Sharma et al., 2024; Kanna S et al., 2024 |

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): RNNs are designed to process sequential data, making them suitable for agricultural applications involving time-series information, such as weather patterns, crop growth stages over time, or animal movement data (Victor et al., 2025).

- Specific RNN Variants: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks (Figure 4), a type of RNN designed to handle long-range dependencies, are commonly employed (Egan et al., 2017). Applications include crop yield prediction based on temporal environmental data (Albahar, 2023), modeling and predicting plant or animal growth trajectories (Mukherjee, 2025), assessing crop nutrient status using time-series spectral data (often in hybrid CNN-LSTM models) , detecting abnormal animal behaviors indicative of illness (Egan et al., 2017), and classifying crops based on multi-temporal remote sensing data (Chengjuan Ren et al., 2020). Figure 4 compares the internal structures of LSTM and GRU (Gated Recurrent Unit) units, highlighting how each architecture uses different gating mechanisms to model long-term dependencies in sequential data.

- Transformers: Originally developed for Natural Language Processing (NLP), Transformer architectures, particularly Vision Transformers (ViTs) adapted for image analysis, are gaining traction in agriculture (Alicia Allmendinger et al., 2025; Khan et al., 2022). Their core mechanism is self-attention, allowing the model to weigh the importance of different parts of the input sequence (or image patches) when making predictions (Alicia Allmendinger et al., 2025).

- ○

- Applications: Transformers are being explored for plant disease classification (achieving high accuracy in paddy and other leaf diseases) (Sapkota and Karkee, 2024), crop yield prediction (e.g., the MMST-ViT model fuses visual remote sensing data with meteorological time-series), multi-object tracking in complex agricultural scenes for robotic applications (Sapkota and Karkee, 2024), and notably, for sophisticated data fusion in agricultural remote sensing, particularly for soil analysis where they have shown significant performance gains over conventional methods (Saki et al., 2024). Detection Transformers (DETR) and variants like RT-DETR are also being tested for real-time weed classification (Khan et al., 2022).

- ○

- Performance & Challenges: Early results are promising, with ViTs demonstrating high accuracy in disease detection (Sapkota and Karkee, 2024) and Transformer-based fusion significantly outperforming older methods in soil analysis (92-97% performance reported). RT-DETR shows high precision in weed detection tasks (Alicia Allmendinger et al., 2025; Khan et al., 2022). However, Transformers can be computationally intensive to train, and their application in agriculture is less mature compared to the long-standing use of CNNs (Alicia Allmendinger et al., 2025).

- ○

- Other Architectures: Beyond the main three, other network types appear in specific contexts. Basic Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) or Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) were used in early AI agriculture work and sometimes feature in hybrid models or simpler regression/classification tasks (Mukherjee, 2025). Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are primarily used for data augmentation, generating synthetic data to expand limited datasets (Mukherjee, 2025). Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) have been applied to crop and weed recognition, leveraging relationships between image features. Less commonly mentioned architectures include Deep Belief Networks (DBNs) (Espinel et al., 2024) and Autoencoders (Chengjuan Ren et al., 2020).

B. Key Methodologies

IV. Evaluating Impact: Performance, Effectiveness, and Benchmarks

A. Quantitative Performance Analysis

- Classification Tasks: For tasks like disease identification, weed/crop classification, or seed sorting, Accuracy (overall percentage of correct predictions) is widely reported (Maganathan et al., 2020). However, accuracy can be misleading, especially with imbalanced datasets (where one class vastly outnumbers others). Therefore, metrics like Precision (proportion of positive identifications that were correct), Recall (proportion of actual positives that were correctly identified, also known as sensitivity), and the F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) are often used to provide a more nuanced evaluation (Mahmud et al., 2021

- Object Detection Tasks: For locating and classifying objects within images (e.g., fruits, weeds, pests), the standard metric is Mean Average Precision (mAP). This metric considers both the classification accuracy and the localization accuracy (how well the predicted bounding box overlaps with the ground truth box, typically measured by Intersection over Union - IoU) across different confidence thresholds and object classes (Bal and Kayaalp, 2021

- Regression Tasks: For predicting continuous values, such as crop yield, fruit counts, or soil moisture levels, common metrics include Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE) (which measure the average magnitude of the prediction errors), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²) (which indicates the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables) (Hassija et al., 2024

- Density Estimation Tasks: For counting methods based on density maps, metrics like the Structural Similarity Measurement Index (SSIM) (comparing map similarity) and Percentage of Correct Keypoints (PCK) (evaluating localization accuracy) may be used (Farjon et al., 2023).

B. Comparative Assessment Against Traditional Techniques

C. Real-World Impact and Efficiency Gains

V. Harvesting the Benefits: Advantages of DL Adoption

- Improved Accuracy and Performance: A cornerstone benefit is the ability of DL models to achieve significantly higher accuracy compared to traditional machine learning algorithms and conventional methods in various agricultural tasks. This includes more accurate classification of diseases, pests, and weeds; more precise detection and localization of objects like fruits; and more reliable prediction of outcomes such as crop yield (Mukherjee, 2025). This enhanced accuracy translates into more dependable insights for decision-making.

- Automation and Efficiency: DL enables the automation of tasks that are traditionally labor-intensive, time-consuming, and sometimes prone to human error (Keskes and Nita, 2024). Examples include automated field scouting for diseases and pests, robotic weed removal, automated fruit counting for yield estimation, and potentially even robotic harvesting (Katharria et al., 2025). This automation leads to significant savings in time and labor costs, freeing up human resources for higher-level management tasks and increasing overall operational efficiency (Li et al., 2024).

- Enhanced Decision-Making: By processing vast amounts of complex data from sensors, drones, satellites, and other sources, DL provides farmers and agronomists with timely, data-driven insights that were previously unavailable or difficult to obtain (Bal and Kayaalp, 2021). These insights support better-informed decisions regarding critical aspects of farm management, including optimal planting strategies, precise irrigation scheduling, targeted fertilizer application, effective pest and disease control measures, and determining the ideal timing for harvest (Benos et al., 2021).

- Resource Optimization and Cost Savings: DL is a key enabler of precision agriculture techniques, allowing for the variable-rate application of inputs based on specific needs within a field (Li et al., 2024; Mahmud et al., 2021). By accurately identifying areas requiring water, fertilizer, or pesticides, DL systems facilitate targeted interventions, thereby minimizing the overall use of these resources (Chintakunta et al., 2023). This optimization reduces waste, lowers input costs for the farmer, and lessens the potential negative environmental impact associated with excessive resource use (Keskes and Nita, 2024).

- Early Detection and Proactive Management: DL models, particularly those analyzing image or sensor data, can often detect subtle signs of problems like plant diseases, pest infestations, nutrient deficiencies, or water stress at very early stages, sometimes even before they are visible to the human eye (Saki et al., 2024). This early detection capability allows for prompt and proactive interventions, which are typically more effective and less costly than reactive measures taken after a problem has become widespread, thereby minimizing potential crop losses and maintaining farm health (Bouacida et al., 2025).

- Scalability and Monitoring: DL facilitates the monitoring and analysis of large agricultural areas efficiently (Ojo and Zahid, 2022). When combined with remote sensing technologies like drones and satellites, DL algorithms can process vast amounts of imagery to assess crop health, identify anomalies, map variability, or predict yields across entire fields or even regions, providing a macroscopic view that is difficult to achieve through ground-based methods alone (Mukherjee, 2025).

- Sustainability: By enabling more precise and efficient use of resources (water, nutrients, energy, chemicals) and potentially reducing reliance on broad-spectrum treatments, DL contributes significantly to the goals of sustainable agriculture (Katharria et al., 2025). Optimized practices can lead to reduced environmental footprints, improved soil health, and greater long-term viability of farming systems (Ojo and Zahid, 2022).

VII. The Future Farm: Emerging Trends and Research Directions

- Integration and Automation (Agriculture 4.0): The overarching trend is towards deeper integration of DL with other technologies within the agriculture 4.0 framework (Maganathan et al., 2020). This involves combining DL-powered analytics with IoT sensor networks, advanced robotics, drone platforms, and sophisticated multi-source data fusion techniques to create highly automated, interconnected, and optimized farming systems (Ren et al., 2017). The future envisions increasingly autonomous systems capable of performing tasks like planting, real-time monitoring, targeted treatment application (fertilizers, pesticides, water), and harvesting with minimal human intervention (Feng et al., 2025; Rane et al., 2024).

- Advanced DL Architectures: While CNNs remain foundational, there is growing exploration and application of more advanced architectures (Sun et al., 2019). Transformers (including Vision Transformers and Detection Transformers) are showing significant promise for handling complex spatio-temporal dependencies, multimodal data fusion, and potentially offering improved robustness in certain tasks like soil analysis, yield prediction, and real-time object detection (Saki et al., 2024). Research into hybrid models that combine the strengths of different architectures (e.g., CNN-RNN for spatio-temporal analysis, CNN-ViT for enhanced feature extraction is also likely to continue (Sapkota and Karkee, 2024).

- Data-Centric AI: Recognizing data as a primary bottleneck, a significant future direction involves a stronger focus on data itself – a "data-centric" approach (Ficili et al., 2025). This includes concerted efforts to create larger, more diverse, higher-quality, and standardized agricultural datasets, potentially through collaborative initiatives and open data platforms. Techniques to mitigate data scarcity will remain crucial, including further development and refinement of synthetic data generation methods (using GANs or other simulation techniques) (Tamayo-Vera et al., 2024) and leveraging unlabeled data through self-supervised learning approaches for pre-training models on vast agricultural datasets. Addressing and mitigating bias in existing and future datasets will also be critical (Mehmet Alican, 2022).

- Explainable AI (XAI) and Trust: As DL models take on more critical roles in decision-making and autonomous systems, the need for transparency and interpretability will intensify (Hossain et al., 2025). Research and development in XAI tailored for agricultural applications will be crucial for building user trust among farmers and agronomists, facilitating model debugging and validation, ensuring fairness and accountability, and potentially meeting future regulatory requirements (Ragu and Teo, 2023). Using XAI not just for explaining predictions but also for diagnosing model failures and uncovering hidden dataset issues will become increasingly important (Hossain et al., 2025) . Techniques like inference-only feature fusion are also being explored for enhanced interpretability (Mohyuddin et al., 2024).

- Edge AI: To enable real-time analysis and decision-making directly on farm equipment (tractors, robots), drones, or local sensors without relying on constant, high-bandwidth cloud connectivity, deploying DL models at the "edge" is a key trend (Hu et al., 2023). This necessitates research into developing computationally efficient model architectures (e.g., lightweight versions of YOLO, MobileNet, model compression techniques, and hardware acceleration for resource-constrained devices. (Bouacida et al., 2025).

- Generative AI (GenAI): The capabilities of large language models (LLMs) and other generative AI techniques are beginning to be explored in agriculture (Mahmud et al., 2021). Potential applications include creating conversational AI agents to provide decision support for farmers (e.g., answering queries based on farm data and external knowledge), accessing and synthesizing information from unstructured sources (reports, manuals), generating synthetic training data, or even optimizing complex farm management plans (Rane et al., 2024). Effective deployment will require modernizing tech infrastructure and establishing robust data foundations within agricultural organizations (Thangamani et al., 2024).

- Sustainability Focus: There is a growing emphasis on explicitly designing, evaluating, and optimizing DL applications based on their contribution to specific sustainability goals (Olawumi and Oladapo, 2025). This involves moving beyond purely technical performance metrics to quantify impacts on resource use efficiency (water, energy, nutrients), reduction in chemical inputs, minimization of environmental footprint (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution), and promotion of biodiversity and long-term soil health (Tamayo-Vera et al., 2024).

- Multimodal Learning: Future agricultural systems will increasingly rely on integrating information from diverse data modalities(Olawumi and Oladapo, 2025). Developing DL models capable of effectively learning from and fusing multimodal data – such as combining visual imagery, spectral data, thermal readings, LiDAR point clouds, time-series sensor data, weather patterns, soil maps, and even genomic information – will be crucial for achieving a holistic understanding and enabling highly precise management (Aarif et al., 2025; Olawumi and Oladapo, 2025).

- Addressing Specific Challenges: Ongoing research will continue to focus on overcoming persistent technical challenges, including enhancing model robustness against real-world environmental variability (García-Navarrete et al., 2025), improving performance in scenarios with heavy object occlusion (e.g., fruits hidden by leaves), further reducing the computational cost of training and inference , and developing lower-cost, accessible sensing and hardware solutions to broaden adoption (Bal and Kayaalp, 2021).

IX. Conclusion: Synthesizing the Present and Future of DL in Agriculture

Competing interests

Authors’ Contributions

References

- Aarif K. O., M., A. Alam, and Y. Hotak. 2025. Smart Sensor Technologies Shaping the Future of Precision Agriculture: Recent Advances and Future Outlooks. J Sens. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A., C. Zhao, W. Ullah, R. Ahmad, M. Waseem, and J. Zhu. 2021. Towards Sustainable Farm Production System: A Case Study of Corn Farming. Sustainability 13: 9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, K., and N. Kumar. 2025. AI-ML Applications in Agriculture and Food Processing. , 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, N., H. Lan, T. Raza, M. Yaqub, R. Iqbal, and M.S. Pathan. 2025. Artificial intelligence in agriculture: Advancing crop productivity and sustainability. J Agric Food Res 20: 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, Aixa. 2024. AI Applications in Agriculture: Sustainable Farming [WWW Document]. Available online: https://montrealethics.ai/ai-applications-in-agriculture-sustainable-farming/ (accessed on 4.10.25). accessed.

- Albahar, M. 2023. A Survey on Deep Learning and Its Impact on Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities. Agriculture 13: 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, Alicia, Ahmet Oğuz Saltık, Gerassimos Peteinatos, Anthony Stein, and Roland Gerhards. 2025. Assessing the Capability of YOLO-and Transformer-based Object Detectors for Real-time Weed Detection.

- Alina, P. 2024. AI in Agriculture—The Future of Farming [WWW Document]. Available online: https://intellias.com/artificial-intelligence-in-agriculture/ (accessed on 4.10.25).

- Awais, M., S.M.Z.A. Naqvi, H. Zhang, L. Li, W. Zhang, F.A. Awwad, E.A.A. Ismail, M.I. Khan, V. Raghavan, and J. Hu. 2023. AI and machine learning for soil analysis: an assessment of sustainable agricultural practices. Bioresour Bioprocess 10: 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, C.M., A. Poulose, and H. Gan. 2024. Agricultural object detection with You Only Look Once (YOLO) Algorithm: A bibliometric and systematic literature review. Comput Electron Agric 223: 109090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAL, F., and F. KAYAALP. 2021. Review of machine learning and deep learning models in agriculture. International Advanced Researches and Engineering Journal 5: 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, N., and A. Singla. 2022. Emerging Trends in Machine Learning to Predict Crop Yield and Study Its Influential Factors: A Survey. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 29: 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benos, L., A.C. Tagarakis, G. Dolias, R. Berruto, D. Kateris, and D. Bochtis. 2021. Machine Learning in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Updated Review. Sensors 21: 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdugo, C.A., R. Zito, S. Paulus, and A.-K. Mahlein. 2014. Fusion of sensor data for the detection and differentiation of plant diseases in cucumber. Plant Pathol 63: 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouacida, I., B. Farou, L. Djakhdjakha, H. Seridi, and M. Kurulay. 2025. Innovative deep learning approach for cross-crop plant disease detection: A generalized method for identifying unhealthy leaves. Information Processing in Agriculture 12: 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Chengjuan, Dae-Kyoo Kim, and Dongwon Jeong. 2020. A Survey of Deep Learning in Agriculture: Techniques and Their Applications. Journal of Information Processing Systems: Vol. 16, No. 5, pp. 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintakunta, A.N., S. Koganti, Y. Nuthakki, and V.K. Kolluru. 2023. Deep Learning and Sustainability in Agriculture: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing 12: 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.T., X. Xu, Y. Wei, Z. Huang, A.G. Schwing, R. Brunner, H. Khachatrian, H. Karapetyan, I. Dozier, G. Rose, D. Wilson, A. Tudor, N. Hovakimyan, T.S. Huang, and H. Shi. 2020. Agriculture-Vision: A Large Aerial Image Database for Agricultural Pattern Analysis. in: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE; pp. 2825–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Delgado, D., C. Rodriguez, A. Bernuy-Alva, C. Navarro, and A. Inga-Alva. 2025. Optimization of Vegetable Production in Hydroculture Environments Using Artificial Intelligence: A Literature Review. Sustainability 17: 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, S., W. Fedorko, A. Lister, J. Pearkes, and C. Gay. 2017. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with jet constituents for boosted top tagging at the LHC. [Google Scholar]

- Espinel, R., G. Herrera-Franco, J.L. Rivadeneira García, and P. Escandón-Panchana. 2024. Artificial Intelligence in Agricultural Mapping: A Review. Agriculture 14: 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjon, G., L. Huijun, and Y. Edan. 2023. Deep-Learning-based Counting Methods, Datasets, and Applications in Agriculture--A Review. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q., H. Yang, Y. Liu, Z. Liu, S. Xia, Z. Wu, and Y. Zhang. 2025. Interdisciplinary perspectives on forest ecosystems and climate interplay: a review. Environmental Reviews 33: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficili, I., M. Giacobbe, G. Tricomi, and A. Puliafito. 2025. From Sensors to Data Intelligence: Leveraging IoT, Cloud, and Edge Computing with AI. Sensors 25: 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A., S. Yoon, S. Kim, and D. Park. 2017. A Robust Deep-Learning-Based Detector for Real-Time Tomato Plant Diseases and Pests Recognition. Sensors 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Navarrete, O.L., J.H. Camacho-Tamayo, A.B. Bregon, J. Martín-García, and L.M. Navas-Gracia. 2025. Performance Analysis of Real-Time Detection Transformer and You Only Look Once Models for Weed Detection in Maize Cultivation. Agronomy 15: 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia Moisés, A., I. Vitoria Pascual, J.J. Imas González, and C. Ruiz Zamarreño. 2023. Data Augmentation Techniques for Machine Learning Applied to Optical Spectroscopy Datasets in Agrifood Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 23: 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H., T. Su, X. Jiang, L. Li, L. Xiong, J. Zhou, and Z. Pang. 2025. FS-YOLOv9: A Frequency and Spatial Feature-Based YOLOv9 for Real-time Breast Cancer Detection. Acad Radiol 32: 1228–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi-Beni, L., and A. Gebrehiwot. 2020. DEEP LEARNING FOR REMOTE SENSING IMAGE CLASSIFICATION FOR AGRICULTURE APPLICATIONS. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences XLIV-M-2–2020, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V., V. Chamola, A. Mahapatra, A. Singal, D. Goel, K. Huang, S. Scardapane, I. Spinelli, M. Mahmud, and A. Hussain. 2024. Interpreting Black-Box Models: A Review on Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Cognit Comput 16: 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I., G. Zamzmi, P.R. Mouton, M.S. Salekin, Y. Sun, and D. Goldgof. 2025. Explainable AI for Medical Data: Current Methods, Limitations, and Future Directions. ACM Comput Surv, vol. 57, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.I., M. Awrangjeb, S. Pan, and A. Mamun. 2025. Transfer learning in agriculture: a review. Artif Intell Rev 58: 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M., Z. Li, J. Yu, X. Wan, H. Tan, and Z. Lin. 2023. Efficient-Lightweight YOLO: Improving Small Object Detection in YOLO for Aerial Images. Sensors 23: 6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S., J. Ko, and J.-M. Yeom. 2022. Predicting rice yield at pixel scale through synthetic use of crop and deep learning models with satellite data in South and North Korea. Science of The Total Environment 802: 149726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H., and E. Learned-Miller. 2017. Face Detection with the Faster R-CNN. in: 2017 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017)IEEE; pp. 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A., and F.X. Prenafeta-Boldú. 2018. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput Electron Agric 147: 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanna S, K., K. Ramalingam, P. P, J. R, and P. P.C. 2024. YOLO deep learning algorithm for object detection in agriculture: a review. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharria, A., K. Rajwar, M. Pant, J.D. Velasquez, V. Snasel, and K. Deep. 2025. Information Fusion in Smart Agriculture: Machine Learning Applications and Future Research Directions. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharria, A., K. Rajwar, M. Pant, J.D. Velásquez, V. Snášel, and K. Deep. 2024. Information Fusion in Smart Agriculture: Machine Learning Applications and Future Research Directions. [Google Scholar]

- Keskes, M. I. 2025. Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Fruit Growing: Innovations, Applications, and Future Prospects. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, M.I., and M.D. Nita. 2024. Developing an AI Tool for Forest Monitoring: Introducing SylvaMind AI. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Series II: Forestry • Wood Industry • Agricultural Food Engineering, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskes, M. I., A. H. Mohamed, S. A. Borz, and M. D. Niţă. 2025. Improving national forest mapping in Romania using machine learning and Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Remote Sensing 17, 4: 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., M. Naseer, M. Hayat, S.W. Zamir, F.S. Khan, and M. Shah. 2022. Transformers in Vision: A Survey. ACM Comput Surv, vol. 54, pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, U., M. S.M., S. V. Gurlahosur, and G. Bhogar. 2021. Quantization Friendly MobileNet (QF-MobileNet) Architecture for Vision Based Applications on Embedded Platforms. Neural Networks 136: 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhiar, I.A., H. Yan, C. Zhang, G. Wang, B. He, B. Hao, Y. Han, B. Wang, R. Bao, T.N. Syed, J.N. Chauhdary, and Rakibuzzaman Md. 2024. A Review of Precision Irrigation Water-Saving Technology under Changing Climate for Enhancing Water Use Efficiency, Crop Yield, and Environmental Footprints. Agriculture 14: 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Z. Zhang, L. Lei, X. Wang, and X. Guo. 2020. Agricultural Greenhouses Detection in High-Resolution Satellite Images Based on Convolutional Neural Networks: Comparison of Faster R-CNN, YOLO v3 and SSD. Sensors 20: 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y., L. Li, H. Xiao, F. Xu, B. Shan, and H. Yin. 2025. YOLO-MECD: Citrus Detection Algorithm Based on YOLOv11. Agronomy 15: 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganathan, T., S. Senthilkumar, and V. Balakrishnan. 2020. Machine Learning and Data Analytics for Environmental Science: A Review, Prospects and Challenges. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng, vol. 955, p. 12107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.S., A. Zahid, A.K. Das, M. Muzammil, and M.U. Khan. 2021. A systematic literature review on deep learning applications for precision cattle farming. Comput Electron Agric 187: 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinger, K., and R. Baeza-Yates. 2024. Responsible AI in Farming: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Sustainable Technology Design. Applied Sciences 14: 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancipe-Castro, L., and R.E. Gutiérrez-Carvajal. 2022. Prediction of environment variables in precision agriculture using a sparse model as data fusion strategy. Information Processing in Agriculture 9: 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmican, N., and et al. 2022. Uncovering Bias in the PlantVillage Dataset:A critical evaluation of the most famous plant disease detection dataset used for developing deep learning models [WWW Document]. WWW Document. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A. H., M. I. Keskes, and M. D. Nita. 2024. Analyzing the Accuracy of Satellite-Derived DEMs Using High-Resolution Terrestrial LiDAR. Land 13, 12: 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyuddin, G., M.A. Khan, A. Haseeb, S. Mahpara, M. Waseem, and A.M. Saleh. 2024. Evaluation of Machine Learning Approaches for Precision Farming in Smart Agriculture System: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 12: 60155–60184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchid, A., M. Marhoun, R. El Alami, and B. Boukili. 2024. Intelligent detection for sustainable agriculture: A review of IoT-based embedded systems, cloud platforms, DL, and ML for plant disease detection. Multimed Tools Appl 83: 70961–71000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, Mujahid. 2024. Precision Irrigation Scheduling using Real-Time Environmental Data. International Journal on Computational Modelling Applications 1: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. 2025. Deep Learning in Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities–A Comprehensive Review. African Journal OF Biomedical Research, 2397–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, N.Y., T. Mahmood, A.R.M. Forkan, A. Morshed, P.P. Jayaraman, and M.S. Siddiqui. 2023. Weed Detection Using Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Sensors 23: 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomidis, A., C. Catal, and A. Kassahun. 2023. Deep learning for crop yield prediction: a systematic literature review. N Z J Crop Hortic Sci 51: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawumi, M.A., and B.I. Oladapo. 2025. AI-driven predictive models for sustainability. J Environ Manage 373: 123472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osco, L.P., J. Marcato Junior, A.P. Marques Ramos, L.A. de Castro Jorge, S.N. Fatholahi, J. de Andrade Silva, E.T. Matsubara, H. Pistori, W.N. Gonçalves, and J. Li. 2021. A review on deep learning in UAV remote sensing. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 102: 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhiary, M. 2024. The Convergence of Deep Learning, IoT, Sensors, and Farm Machinery in Agriculture. , 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragu, N., and J. Teo. 2023. Object detection and classification using few-shot learning in smart agriculture: A scoping mini review. Front Sustain Food Syst 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, J., Ö. Kaya, S.K. Mallick, and N.L. Rane. 2024. Smart farming using artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, and ChatGPT: Applications, opportunities, challenges, and future directions. In Generative Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture, Education, and Business. Deep Science Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S., K. He, R. Girshick, and J. Sun. 2017. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 39: 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z., S. Wang, and Y. Zhang. 2023. Weakly supervised machine learning. CAAI Trans Intell Technol 8: 549–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H., T. Zebin, G. Cielniak, B. De La Iglesia, and B. Magri. 2024. Deep Learning for Precision Agriculture: Post-Spraying Evaluation and Deposition Estimation. [Google Scholar]

- Saiwa, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. 2016. Deep Learning for Agriculture Data-Driven Decisions and Increased Efficiency [WWW Document]. Available online: https://saiwa.ai/sairone/blog/deep-learning-for-agriculture/ (accessed on 4.9.25).

- Saki, M., R. Keshavarz, D. Franklin, M. Abolhasan, J. Lipman, and N. Shariati. 2024. Precision Soil Quality Analysis Using Transformer-based Data Fusion Strategies: A Systematic Review.

- Santos Júnior, E.S. dos, T. Paixão, and A.B. Alvarez. 2025. Comparative Performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11 for Layout Analysis of Historical Documents Images. Applied Sciences 15: 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R., and M. Karkee. 2024. YOLO11 and Vision Transformers based 3D Pose Estimation of Immature Green Fruits in Commercial Apple Orchards for Robotic Thinning. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj, M.G., A. Vergara, H. Ruiz, N. Safari, S. Elayabalan, W. Ocimati, and G. Blomme. 2019. AI-powered banana diseases and pest detection. Plant Methods 15: 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyrek, F.B., and H. Yiğit. 2024. Diagnosis of Lung Cancer from Computed Tomography Scans with Deep Learning Methods. JUCS-Journal of Universal Computer Science 30: 1089–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., V. Kumar, and L. Longchamps. 2024. Comparative performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and Faster R-CNN models for detection of multiple weed species. Smart Agricultural Technology 9: 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C., and T.M. Khoshgoftaar. 2019. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J Big Data 6: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., T. Wang, P. Cai, S.K. Mondal, and J.P. Sahoo. 2023. A Comprehensive Survey of Few-shot Learning: Evolution, Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. ACM Comput Surv, vol. 55, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D., H. Kong, Y. Qiao, and S. Sukkarieh. 2021. Data augmentation for deep learning based semantic segmentation and crop-weed classification in agricultural robotics. Comput Electron Agric 190: 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., L. Di, Z. Sun, Y. Shen, and Z. Lai. 2019. County-Level Soybean Yield Prediction Using Deep CNN-LSTM Model. Sensors 19: 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C., S. Ioffe, V. Vanhoucke, and A. Alemi. 2017. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Vera, D., X. Wang, and M. Mesbah. 2024. A Review of Machine Learning Techniques in Agroclimatic Studies. Agriculture 14: 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N., E. Bhattacharjee, R. Jain, B. Acharya, and Y.-C. Hu. 2024. Deep learning-based parking occupancy detection framework using ResNet and VGG-16. Multimed Tools Appl 83: 1941–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangamani, R., D. Sathya, G.K. Kamalam, and G.N. Lyer. 2024. AI Green Revolution: Reshaping Agriculture’s Future. , 421–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engelen, J.E., and H.H. Hoos. 2020. A survey on semi-supervised learning. Mach Learn 109: 373–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B., A. Nibali, and Z. He. 2025. A Systematic Review of the Use of Deep Learning in Satellite Imagery for Agriculture. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 18: 2297–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., W. Cao, F. Zhang, Z. Li, S. Xu, and X. Wu. 2022a. A Review of Deep Learning in Multiscale Agricultural Sensing. Remote Sens (Basel) 14: 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Q. Zhang, F. Yu, N. Zhang, X. Zhang, Y. Li, M. Wang, and J. Zhang. 2024. Progress in Research on Deep Learning-Based Crop Yield Prediction. Agronomy 14: 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methodology | Description | Example Applications | References |

| Transfer Learning (TL) | Uses pre-trained models (e.g., on ImageNet) fine-tuned on smaller agricultural datasets. Reduces need for large, labeled data and training time. | Plant disease detection, weed identification, crop classification | Morchid et al., 2024; Hossen et al., 2025; Albahar, 2023; Bouacida et al., 2025 |

| Data Fusion | Combines data from various sources (e.g., RGB, multispectral, hyperspectral, thermal imagery; drones, satellites, IoT sensors) to create more accurate and holistic models. | SAR-optical fusion for crop mapping, combining ground and remote sensing data | Mancipe-Castro & Gutiérrez-Carvajal, 2022; Katharria et al., 2025; Saki et al., 2024 |

| Data Augmentation | Enhances dataset size and diversity via transformations (rotation, flips, noise, etc.) or synthetic image generation using GANs (e.g., DCGAN). | Robust classification of crops, diseases, weeds | Shorten & Khoshgoftaar, 2019; Gracia Moisés et al., 2023; Su et al., 2021 |

| Few-Shot Learning (FSL) | Enables model training with very few labeled samples using techniques like Siamese or prototypical networks. Critical for rare or underrepresented classes in agriculture. | Plant disease classification with limited samples | Song et al., 2023; Ragu & Teo, 2023; Mohyuddin et al., 2024 |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | Provides transparency in DL models through methods like Class Activation Maps (CAMs) and LIME. Helps build trust, debug models, and validate decision-making processes. | Verifying disease model decisions, supporting precision spraying evaluation | Mallinger & Baeza-Yates, 2024; Hassija et al., 2024; Espinel et al., 2024 |

| Other Techniques | Includes: • Ensemble Learning – combines multiple models for higher accuracy • Semi-Supervised Learning – uses labeled and unlabeled data • Weakly Supervised Learning – trains with imprecise labels • Self-Supervised Learning – learns from unlabeled data via pretext tasks | Object counting, pre-training on large agricultural datasets | Benos et al., 2021; van Engelen & Hoos, 2020; Ren et al., 2023; Chiu et al., 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).