Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

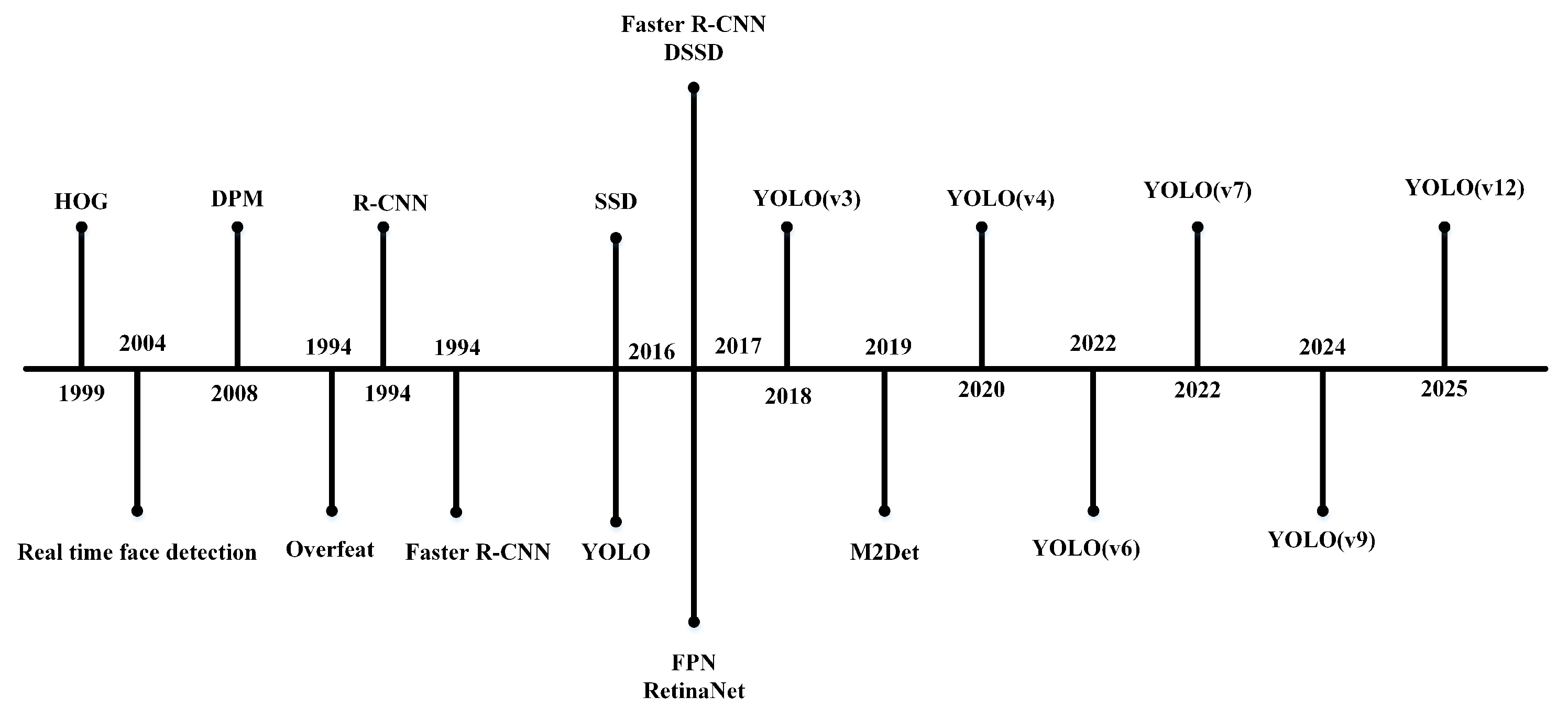

2. Object Detection Fundamentals

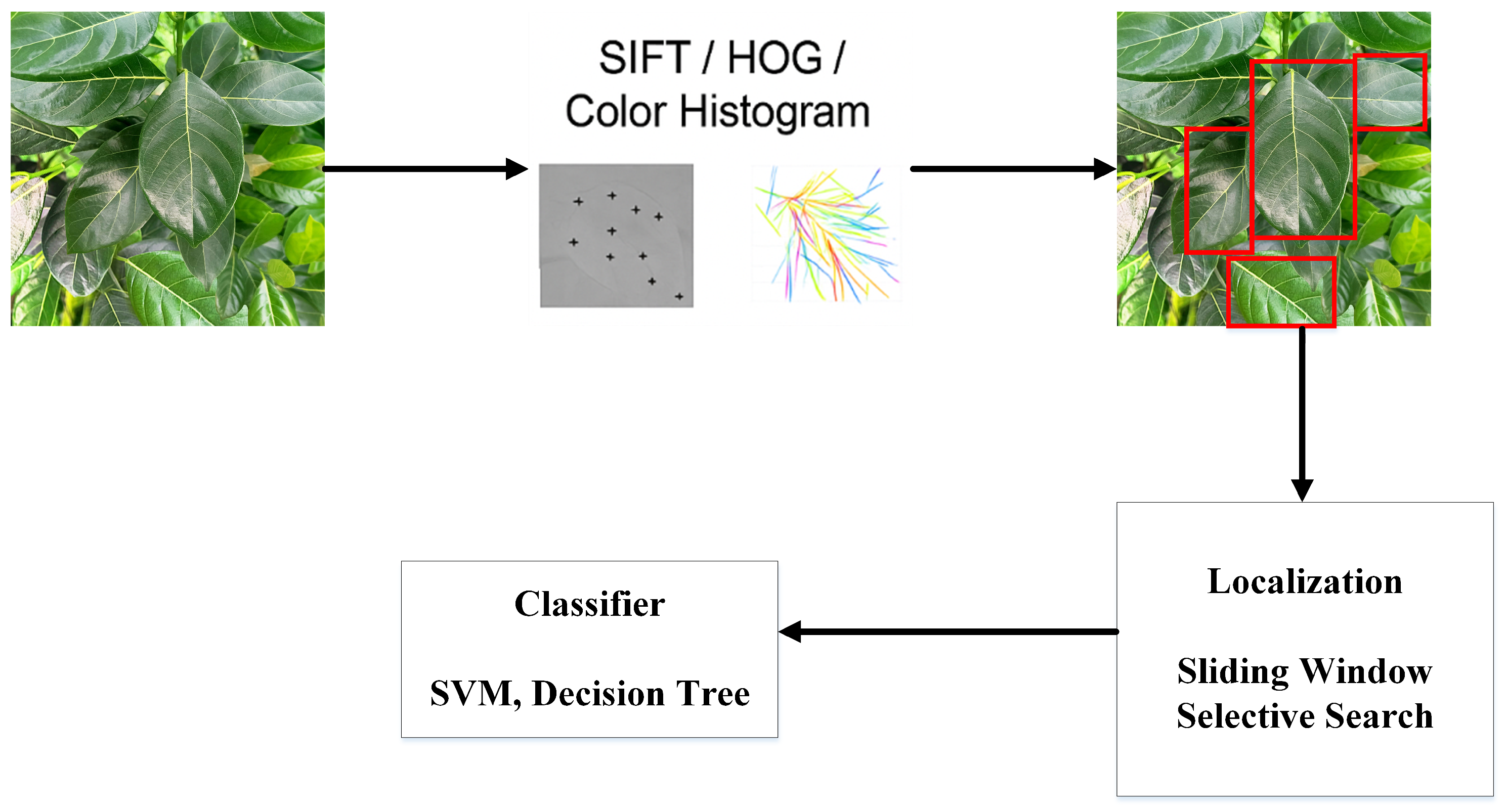

2.1. Traditional Approaches in Agriculture

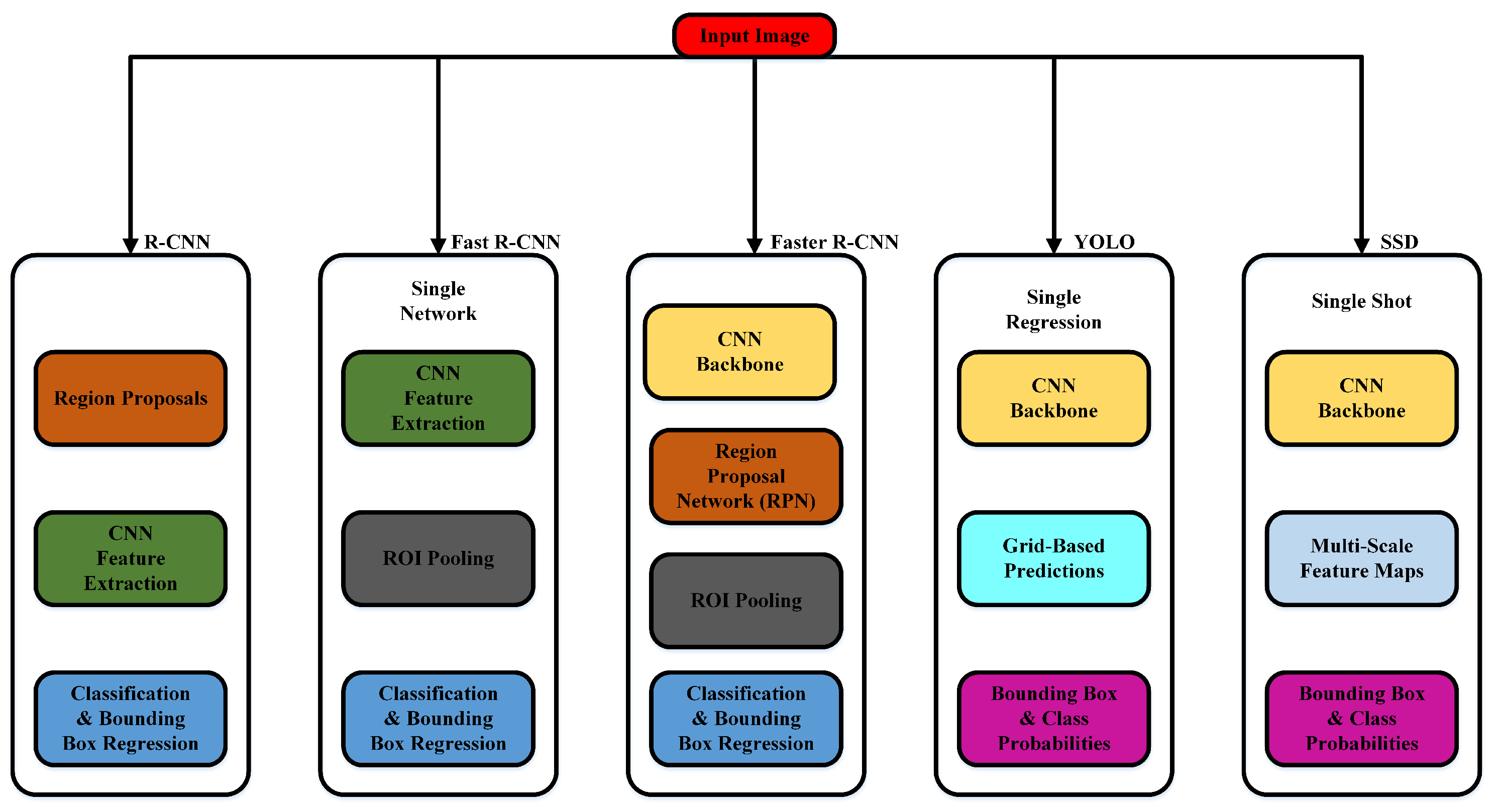

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Methods in Agriculture

2.2.1. R-CNN and Fast R-CNN

2.2.2. Faster R-CNN

2.2.3. YOLO (You Only Look Once)

2.2.4. SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector)

3. Applications in Agriculture

3.1. Weed Detection

3.2. Fruit Counting and Ripeness Detection

3.3. Disease and Pest Detection

3.4. Crop Row and Canopy Detection

4. Dataset Overview

4.1. Key Public Datasets

4.1.1. PlantVillage

4.1.2. DeepWeeds

4.1.3. AppleAphid

4.1.4. AgriNet

4.1.5. Mini-PlantNet

4.2. Dataset Characteristics and Contributions

4.3. Challenges in Dataset Diversity and Quality

4.4. Implications for Object Detection Research

5. Comparison of Algorithms

5.1. Algorithmic Foundations and Performance

5.1.1. Faster R-CNN

5.1.2. YOLO

5.1.3. SSD

5.1.4. EfficientDet

5.2. Comparative Analysis in Agricultural Contexts

5.3. Broader Implications and Trends

6. Challenges and Open Problems

6.1. Environmental Variability

6.2. Model Generalization

6.3. Real-Time Constraints

7. Future Directions

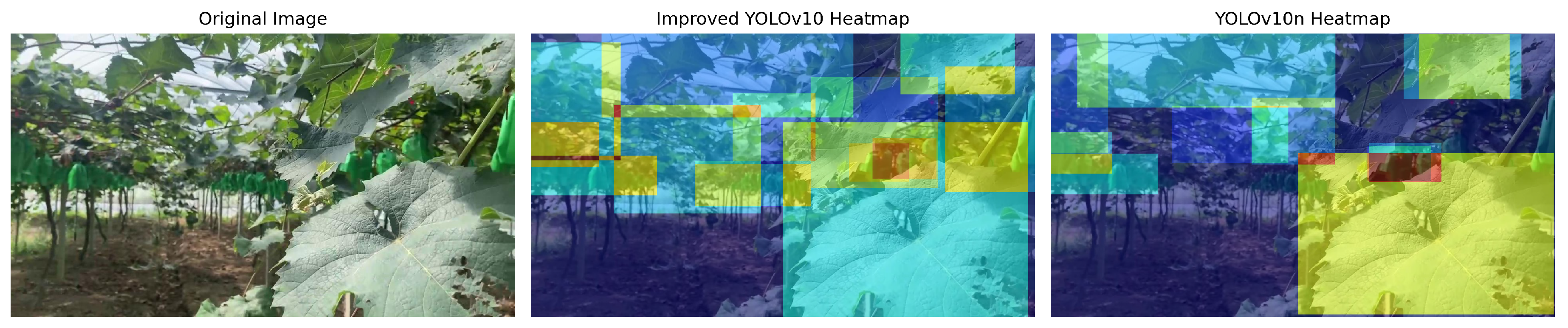

7.1. Explainable AI (XAI)

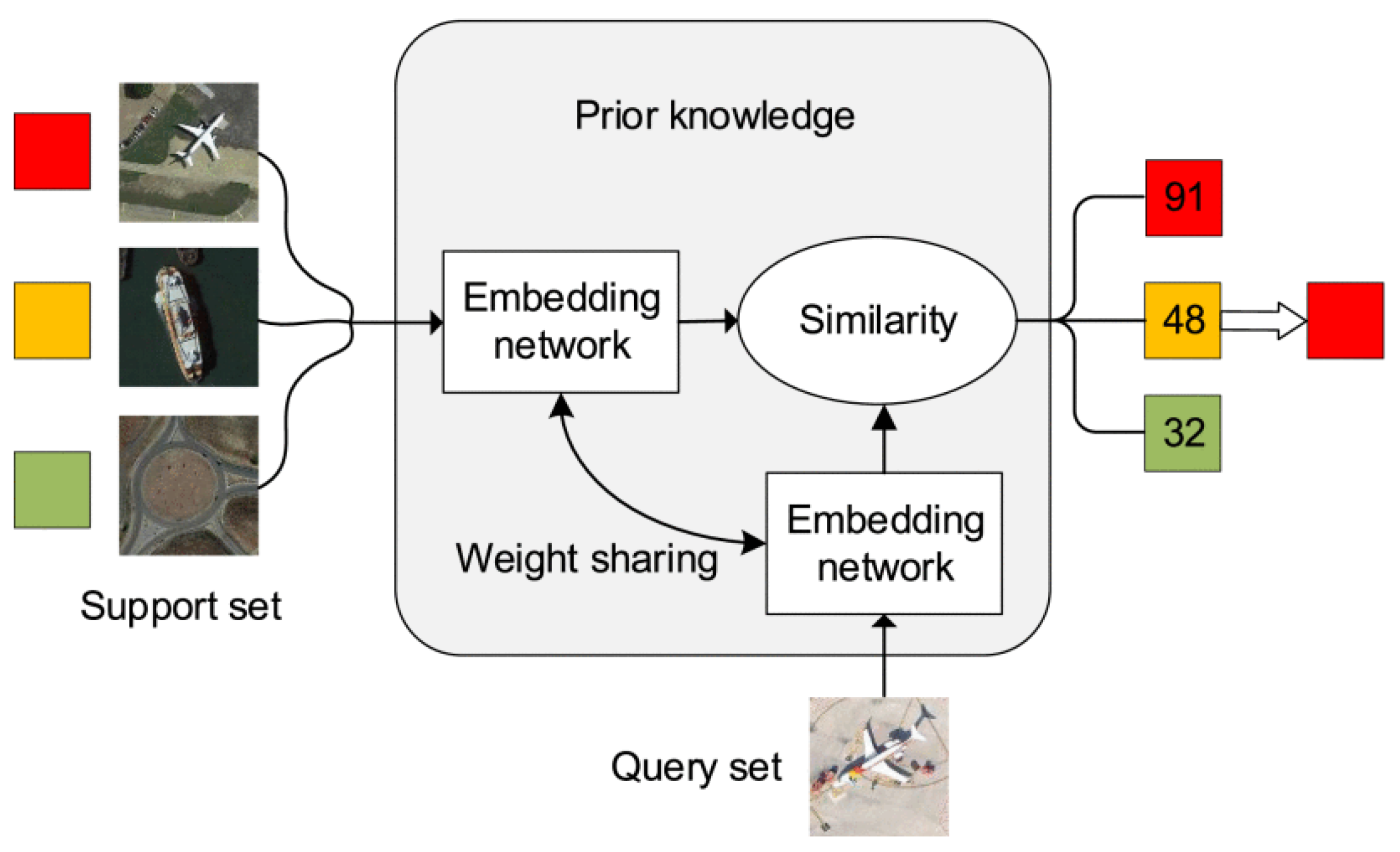

7.2. Few-Shot and Self-Supervised Learning

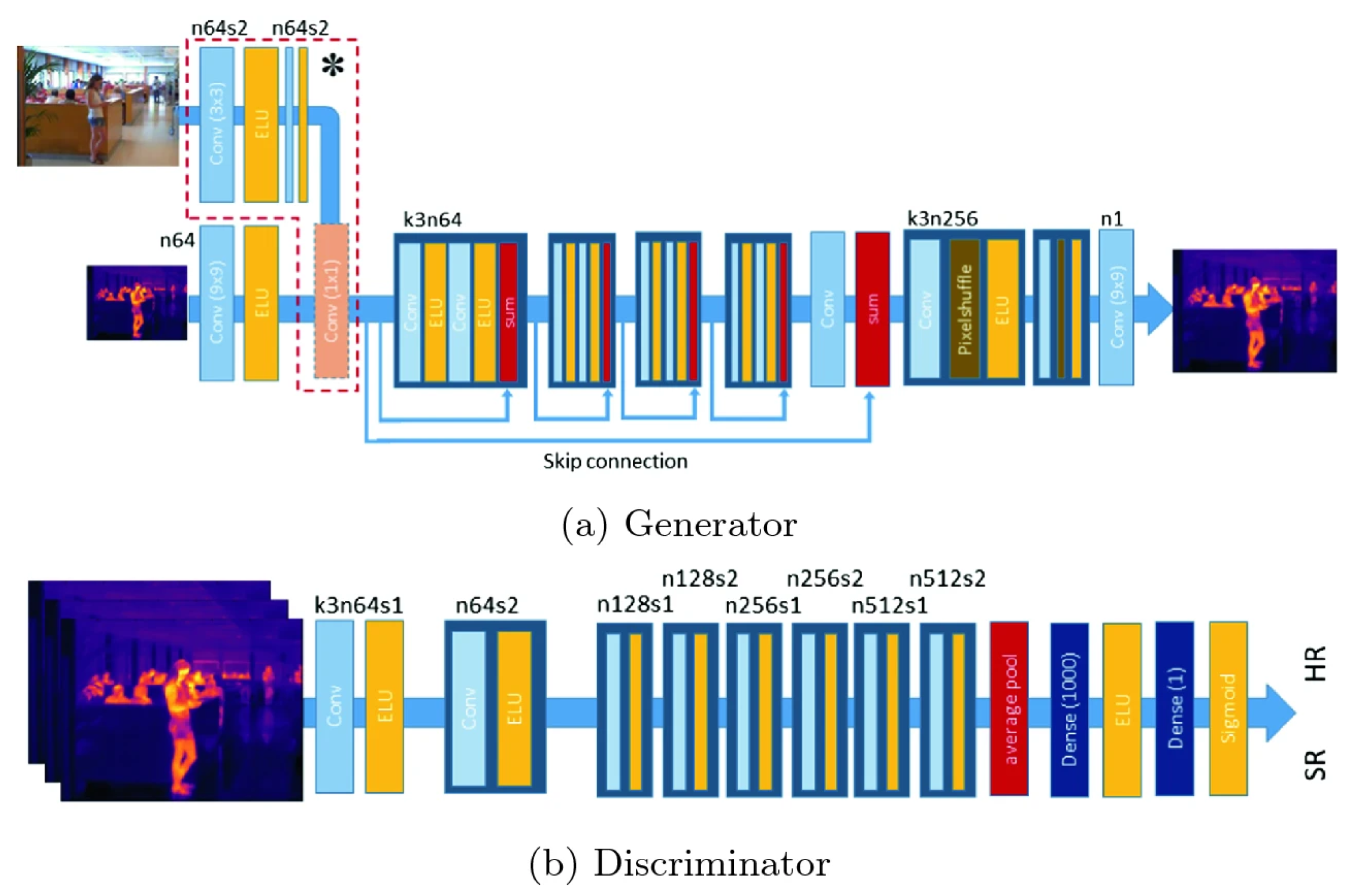

7.3. Multimodal Approaches

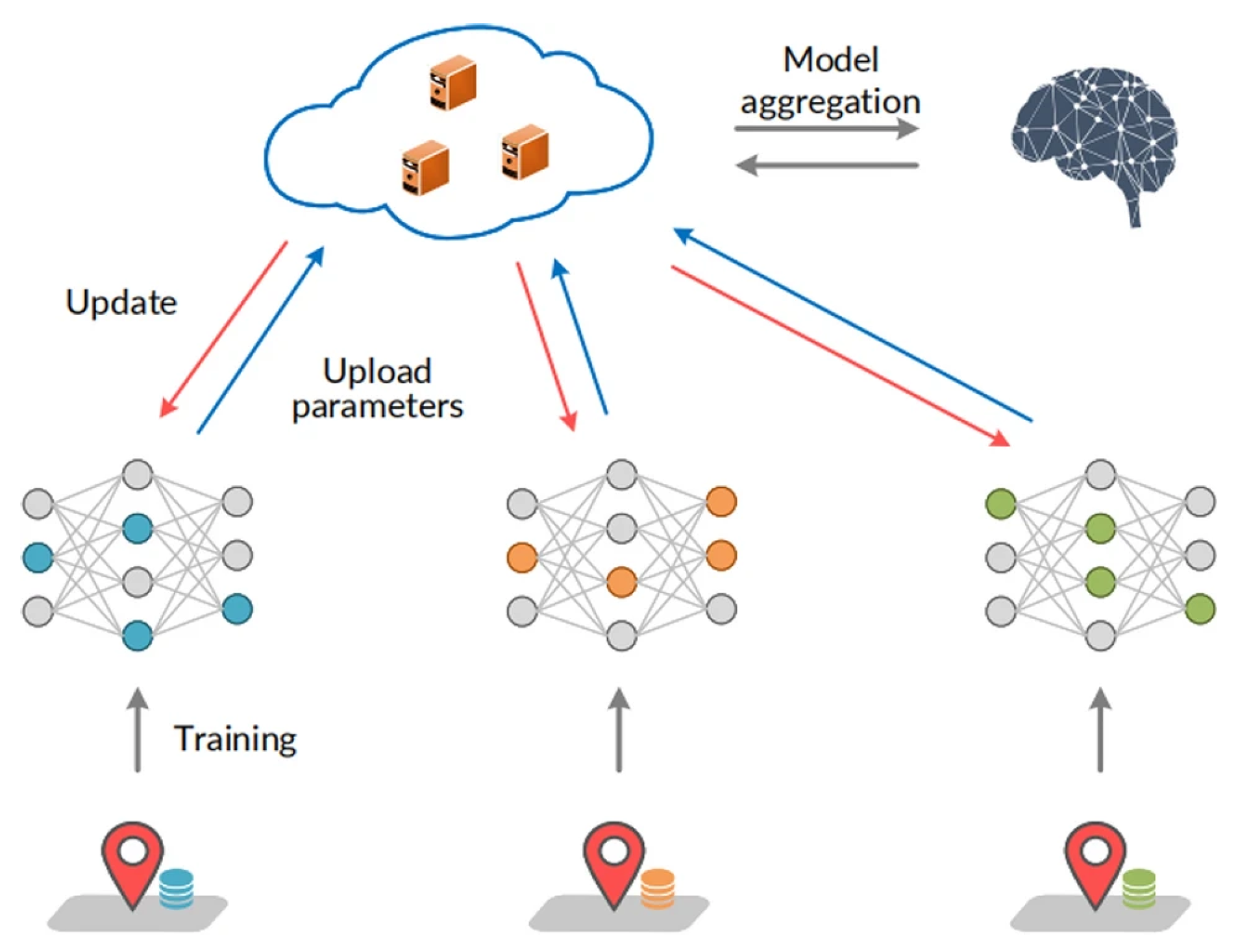

7.4. Federated Learning

7.5. Edge AI Optimization

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alif, M.A.R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv1 to YOLOv10: A comprehensive review of YOLO variants and their application in the agricultural domain. arXiv preprint, 2024; arXiv:2406.10139. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, D.; Guo, T.; Yu, S.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Hu, D. Classification of Apple Color and Deformity Using Machine Vision Combined with CNN. Agriculture 2024, 14, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Zhai, K.; Xu, B.; Wu, J. Green Apple Detection Method Based on Multidimensional Feature Extraction Network Model and Transformer Module. Journal of Food Protection 2025, 88, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganthi, S.U.; Prinslin, L.; Selvi, R.; Prabha, R. Generative AI in Agri: Sustainability in Smart Precision Farming Yield Prediction Mapping System Based on GIS Using Deep Learning and GPS. Procedia Computer Science 2025, 252, 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Majeed, Y.; Naranjo, G.D.; Gambacorta, E.M. Assessment for crop water stress with infrared thermal imagery in precision agriculture: A review and future prospects for deep learning applications. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 182, 106019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Dong, H. A Review of Vision-Based Multi-Task Perception Research Methods for Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2025, 25, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gu, J.; Wang, M. A review on the application of computer vision and machine learning in the tea industry. Frontiers In Sustainable Food Systems 2023, 7, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Cong, S.; Mao, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, N. Quantitative Detection of Mixed Pesticide Residue of Lettuce Leaves Based on Hyperspectral Technique. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2018, 41, e12654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Sun, J.; Lu, B.; Ge, X.; Zhou, X.; Zou, M. Application of Deep Brief Network in Transmission Spectroscopy Detection of Pesticide Residues in Lettuce Leaves. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2019, 42, e13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ge, X.; Wu, X.; Dai, C.; Yang, N. Identification of Pesticide Residues in Lettuce Leaves Based on Near Infrared Transmission Spectroscopy. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2018, 41, e12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Jain, A.; Gupta, P.; Chowdary, V. Machine learning applications for precision agriculture: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 4843–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, R.; Sofi, S.A. Precision agriculture using IoT data analytics and machine learning. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 5602–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Tian, Y.; Yin, W.; Zheng, C. An apple detection and localization method for automated harvesting under adverse light conditions. Agriculture 2024, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Tang, Z.; Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Si, Y.; Lu, M.; Panoutsos, G. Real-time object detection and robotic manipulation for agriculture using a YOLO-based learning approach. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Jaiswal, A.; Prasad, M.; Gandomi, A.H. Towards precision agriculture: IoT-enabled intelligent irrigation systems using deep learning neural network. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 17479–17491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, Z.; Ali, S.; Yang, N.; Fu, S.; Zhang, Y. Multi-class detection of cherry tomatoes using improved YOLOv4-Tiny. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2023, 16, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Jun, S.; Yan, T.; Bing, L.; Hang, Y.; Quansheng, C. Hyperspectral technique combined with deep learning algorithm for detection of compound heavy metals in lettuce. Food Chemistry 2020, 321, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabir, R.M.; Mehmood, K.; Sarwar, A.; Safdar, M.; Muhammad, N.E.; Gul, N.; Akram, H.M.B. Remote Sensing and Precision Agriculture: A Sustainable Future. In Transforming Agricultural Management for a Sustainable Future: Climate Change and Machine Learning Perspectives; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2024; pp. 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiuyan, G.A.O.; ZHANG, Y. Detection of Fruit using YOLOv8-based Single Stage Detectors. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 2023, 14, n/a. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Kong, J.L.; Jin, X.B.; Wang, X.Y.; Su, T.L.; Zuo, M. CropDeep: The crop vision dataset for deep-learning-based classification and detection in precision agriculture. Sensors 2019, 19, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhu, T.; Tao, Y.; Ni, C. Review of deep learning-based methods for non-destructive evaluation of agricultural products. Biosystems Engineering 2024, 245, 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Qiu, B.; Ahmad, F.; Kong, C.W.; Xin, H. A State-of-the-Art Analysis of Obstacle Avoidance Methods from the Perspective of an Agricultural Sprayer UAV’s Operation Scenario. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, H. Evaluation of a Laser Scanning Sensor in Detection of Complex-Shaped Targets for Variable-Rate Sprayer Development. Transactions of the ASABE 2016, 59, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, V.I.; Allen, W.A. Electrooptical remote sensing methods as nondestructive testing and measuring techniques in agriculture. Applied Optics 1968, 7, 1819–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Wang, W.; Gu, J.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Research on Apple Object Detection and Localization Method Based on Improved YOLOX and RGB-D Images. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

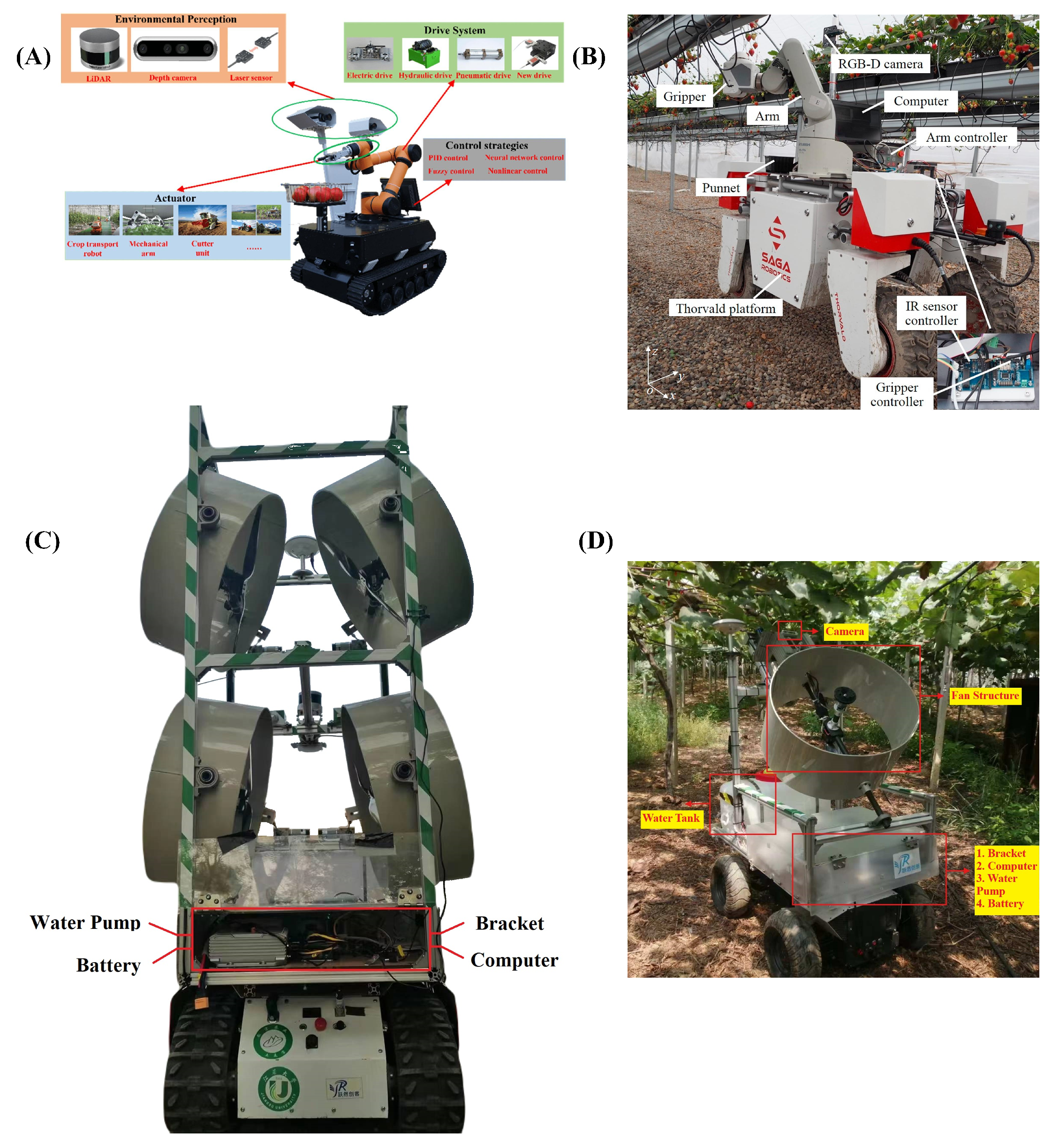

- Xie, D.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. Actuators and sensors for application in agricultural robots: A review. Machines 2022, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Peng, C.; Grimstad, L.; From, P.J.; Isler, V. Development and field evaluation of a strawberry harvesting robot with a cable-driven gripper. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 157, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y.; Zeng, X. Deep learning improved YOLOv8 algorithm: Real-time precise instance segmentation of crown region orchard canopies in natural environment. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 224, 109168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, F. Optimizing precision agriculture: A real-time detection approach for grape vineyard unhealthy leaves using deep learning improved YOLOv7 with feature extraction capabilities. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2025, 231, 109969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H.; Dai, J.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. Deep Learning on Computational-Resource-Limited Platforms: A Survey. Mobile Information Systems 2020, 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.M.; Tu, Y.H.; Li, T.; Ni, Y.; Wang, R.F.; Wang, H. Deep Learning for Sustainable Agriculture: A Systematic Review on Applications in Lettuce Cultivation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, R.; Hu, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, W. Crop-Free-Ridge Navigation Line Recognition Based on the Lightweight Structure Improvement of YOLOv8. Agriculture 2025, 15, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H. Edge-AI for Agriculture: Lightweight Vision Models for Disease Detection in Resource-Limited Settings. arXiv preprint, 2024; arXiv:2412.18635. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Zhong, M.; Zhu, W.; Rashid, A.; Han, R.; Virk, M.S.; Ren, X. Advances in Computer Vision and Spectroscopy Techniques for Non-Destructive Quality Assessment of Citrus Fruits: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR),; 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV).; pp. 1440–1448. [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2015, Vol. 28.

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 779–788. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement, 2018, [arXiv:cs.CV/1804.02767].

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors, 2022, [arXiv:cs.CV/2207.02696].

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Pan, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, J. A Real-Time Apple Targets Detection Method for Picking Robot Based on ShufflenetV2-YOLOX. Agriculture 2022, 12, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jia, W.; Ruan, C.; Zhao, D.; Gu, Y.; Chen, W. The recognition of apple fruits in plastic bags based on block classification. Precision Agriculture 2018, 19, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uijlings, J.R.; van de Sande, K.E.; Gevers, T.; Smeulders, A.W. Selective Search for Object Recognition. International Journal of Computer Vision 2013, 104, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladojevic, S.; Arsenovic, M.; Anderla, A.; Culibrk, D.; Stefanovic, D. Deep Neural Networks Based Recognition of Plant Diseases by Leaf Image Classification. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2016, 2016, 3289801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.; Mou, R.M.; Hasan, M.M.; Chakraborty, S.; Razzak, M.A. Recognition and detection of tea leaf’s diseases using support vector machine. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 14th International Colloquium on Signal Processing & Its Applications (CSPA), 2018, pp. 150–154.

- Tang, L.; Tian, L.; Steward, B.L. Classification of broadleaf and grass weeds using Gabor wavelets and an artificial neural network. Transactions of the ASAE 2003, 46, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Fan, S.; Zuo, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Q.; Kong, J. Discrimination of New and Aged Seeds Based on On-Line Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Technology Combined with Machine Learning. Foods 2024, 13, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. Development status and trend of agricultural robot technology. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2021, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Q.; Jin, K.; Xu, G.; Hu, Y. TS-YOLO: An all-day and lightweight tea canopy shoots detection model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Sun, J.; Lu, B.; Chen, Q.; Xun, W.; Jin, Y. Classification of Oolong Tea Varieties Based on Hyperspectral Imaging Technology and BOSS-LightGBM Model. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2019, 42, e13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paymode, A.S.; Malode, V.B. Transfer learning for multi-crop leaf disease image classification using convolutional neural network VGG. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2022, 6, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J. Fused-Deep-Features Based Grape Leaf Disease Diagnosis. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lu, C.; Piao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S. Rice virus release from the planthopper salivary gland is independent of plant tissue recognition by the stylet. Pest Management Science 2020, 76, 3208–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Qian, Y.; EL-Mesery, H.S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, A.; Tang, J. Rapid Detection of Rice Disease Using Microscopy Image Identification Based on the Synergistic Judgment of Texture and Shape Features and Decision Tree–Confusion Matrix Method. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 6589–6600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveros Escamilla, L.D.; Gómez-Espinosa, A.; Escobedo Cabello, J.A.; Cantoral-Ceballos, J.A. Maturity recognition and fruit counting for sweet peppers in greenhouses using deep learning neural networks. Agriculture 2024, 14, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, H.S.; ul Hassan, I.; Hasan, S.; Khurram, M.; Stricker, D.; Afzal, M.Z. Formation of a Lightweight, Deep Learning-Based Weed Detection System for a Commercial Autonomous Laser Weeding Robot. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjoud, A.B.; Amrouch, M. Object Detection Using Deep Learning, CNNs and Vision Transformers: A Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 35479–35516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, W.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, N. Object localization methodology in occluded agricultural environments through deep learning and active sensing. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 212, 108141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, T.; Deisy, C.; Sridevi, S.; Anbananthen, K.S.M. A comparative study of deep learning and Internet of Things for precision agriculture. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 122, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, S.; Tian, Q.; Huang, G. Computation-efficient Deep Learning for Computer Vision: A Survey. Cybernetics and Intelligence 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Sentís, M.; Vélez, S.; Martínez-Peña, R.; Baja, H.; Valente, J. Object detection and tracking in Precision Farming: A systematic review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 219, 108757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubek, T.; Bumbálek, R.; Ufitikirezi, J.D.D.M.; Strob, M.; Filip, M.; Špalek, F.; Bartoš, P. Advancing precision agriculture with computer vision: A comparative study of YOLO models for weed and crop recognition. Crop Protection 2025, 190, 107076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.; Konovalov, D.A.; Philippa, B.; Ridd, P.; Wood, J.C.; Johns, J.; Banks, W.; Girgenti, B.; Kenny, O.; Whinney, J.; et al. DeepWeeds: A Multiclass Weed Species Image Dataset for Deep Learning. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.H.; Velayudhan, K.K.; Potgieter, J.; Arif, K.M. Weed Identification by Single-Stage and Two-Stage Neural Networks: A Study on the Impact of Image Resizers and Weights Optimization Algorithms. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 850666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Shen, J.; Yang, K.; Zhou, X. Identifying Field Crop Diseases Using Transformer-Embedded Convolutional Neural Network. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xia, Z.; Gu, J.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W. High-precision apple recognition and localization method based on RGB-D and improved SOLOv2 instance segmentation. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2024, 8, 1403872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Su, J.; Huang, R.; Quan, W.; Song, Y.; Fang, Y.; Su, B. Fusing attention mechanism with Mask R-CNN for instance segmentation of grape cluster in the field. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 934450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Han, M.; He, J.; Wen, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y. Object detection and localization algorithm in agricultural scenes based on YOLOv5. Journal of Electronic Imaging 2023, 32, 052402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. EfficientDet: Scalable and Efficient Object Detection. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2020, pp. 10781–10790. [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K.; Chen, D.; Lammers, K.; Lu, R. O2RNet: Occluder-Occludee Relational Network for Robust Apple Detection in Clustered Orchard Environments. Smart Agricultural Technology 2023, 5, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; He, X.; Ge, X.; Wu, X.; Shen, J.; Song, Y. Detection of Key Organs in Tomato Based on Deep Migration Learning in a Complex Background. Agriculture 2018, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Gao, B.; Cao, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, T.; Wei, X. Early detection of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on oilseed rape leaves based on optical properties. Biosystems Engineering 2022, 224, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, M.; Al-Tuwaijari, A. Detection and identification of plant leaf diseases using YOLOv4. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0284567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Han, W.; Guo, P.; Wei, X. YOLOv8-GDCI: Research on the Phytophthora Blight Detection Method of Different Parts of Chili Based on Improved YOLOv8 Model. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Lv, Q.; Bian, Y.; He, R.; Lv, D.; Gao, L.; Li, X. Grape Target Detection Method in Orchard Environment Based on Improved YOLOv7. Agronomy 2025, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Salman, Z.; Lee, K.; Han, D. Harnessing the power of diffusion models for plant disease image augmentation. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1280496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Yu, Y. Artificial convolutional neural network in object detection and semantic segmentation for medical imaging analysis. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 638182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, S.; Sun, C.; Ma, X.; Jiang, Y.; Qi, L. Deep localization model for intra-row crop detection in paddy field. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 169, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, J.; Yan, Y.; Tian, G.; Gu, B. Recent developments and applications of simultaneous localization and mapping in agriculture. Journal of Field Robotics 2022, 39, 956–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milioto, A.; Lottes, P.; Stachniss, C. Milioto, A.; Lottes, P.; Stachniss, C. Real-time semantic segmentation of crop and weed for precision agriculture robots leveraging background knowledge in CNNs. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 2229–2235. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Gao, S.; Jiang, F.; Veeranampalayam-Sivakumar, A.N.; Thompson, L.; Luck, J.; Liu, C. Improved crop row detection with deep neural network for early-season maize stand count in UAV imagery. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 178, 105766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milioto, A.; Lottes, P.; Stachniss, C. Real-time blob-wise sugar beets vs weeds classification for monitoring fields using convolutional neural networks. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2017, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.T.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Huang, Z.; Schwing, A.G.; Brunner, R.; Khachatrian, H.; Karapetyan, H.; Dozier, I.; Rose, G.; et al. Agriculture-Vision: A Large Aerial Image Database for Agricultural Pattern Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020, pp. 2828–2838. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Young, S. A survey of public datasets for computer vision tasks in precision agriculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 178, 105760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.P.; Salathé, M. An open access repository of images on plant health to enable the development of mobile disease diagnostics. arXiv preprint, 2015; arXiv:1511.08060. [Google Scholar]

- Rahnemoonfar, M.; Sheppard, C. Deep count: fruit counting based on deep simulated learning. Sensors 2017, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Abbas, I.; Noor, R.S. Development of Deep Learning-Based Variable Rate Agrochemical Spraying System for Targeted Weeds Control in Strawberry Crop. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Huang, J.; Zhou, X.; Ren, N.; Sun, S. Toward Real Scenery: A Lightweight Tomato Growth Inspection Algorithm for Leaf Disease Detection and Fruit Counting. Plant Phenomics 2024, 6, 0174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Wei, X. STBNA-YOLOv5: An Improved YOLOv5 Network for Weed Detection in Rapeseed Field. Agriculture 2025, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, R.; Andujar Sanchez, D.; Hamouz, P.; Peteinatos, G.G.; Christensen, S.; Fernandez-Quintanilla, C. Advances in site-specific weed management in agriculture—A review. Weed Research 2022, 62, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Sun, S.; Zhang, W.; Shi, F.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Q. Classification and identification of apple leaf diseases and insect pests based on improved ResNet-50 model. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerge, K.; Frigaard, C.E.; Karstoft, H. Object Detection of Small Insects in Time-Lapse Camera Recordings. Sensors 2023, 23, 7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswara, S.M.; Padmanabhan, J. Deep Learning Based Agricultural Pest Monitoring and Classification. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 8684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sahili, Z.; Awad, M. The Power of Transfer Learning in Agricultural Applications: AgriNet. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 992700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čirjak, D.; Aleksi, I.; Lemic, D.; Pajač Živković, I. EfficientDet-4 Deep Neural Network-Based Remote Monitoring of Codling Moth Population for Early Damage Detection in Apple Orchard. Agriculture 2023, 13, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKechnie, I.; Raymond, K.; Stacey, D. Identifying Inconsistencies in Data Quality Between FAOSTAT, WOAH, UN Agriculture Census, and National Data. Data Science Journal 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcin, C.; Joly, A.; Bonnet, P.; Lombardo, J.C.; Affouard, A.; Chouet, M.; Servajean, M.; Lorieul, T.; Salmon, J. Pl@ntNet-300K: a plant image dataset with high label ambiguity and a long-tailed distribution. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Datasets and Benchmarks 2021, 2021.

- Alibabaei, K.; Assunção, E.; Gaspar, P.D.; Soares, V.N.G.J.; Caldeira, J.M.L.P. Real-Time Detection of Vine Trunk for Robot Localization Using Deep Learning Models Developed for Edge TPU Devices. Future Internet 2022, 14, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyan, M.A. Uncovering Bias in the PlantVillage Dataset. arXiv preprint, 2022; arXiv:2206.04374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wang, Y. MAR-YOLOv9: A Multi-Dataset Object Detection Method for Agricultural Fields Based on YOLOv9. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0307643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Feng, Q.; Qiu, Q.; Xie, F.; Zhao, C. Occluded Apple Fruit Detection and Localization with a Frustum-Based Point-Cloud-Processing Approach for Robotic Harvesting. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, A.; Pardo, S.; Sepúlveda, S.; Muñoz, L. Challenges to Use Machine Learning in Agricultural Big Data: A Systematic Literature Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufin, P.; Wang, S.; Lisboa, S.N.; Hemmerling, J.; Tulbure, M.G.; Meyfroidt, P. Taking it further: Leveraging pseudo-labels for field delineation across label-scarce smallholder regions. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2024, 134, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xie, S.; Ning, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z. Evaluating green tea quality based on multisensor data fusion combining hyperspectral imaging and olfactory visualization systems. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, C.; Beaumont, R.; Vencu, R.; Gordon, C.; Wightman, R.; Cherti, M.; Coombes, T.; Katta, A.; Mullis, C.; Wortsman, M.; et al. LAION-5B: An open large-scale dataset for training next generation image-text models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 25278–25294. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Rathod, V.; Sun, C.; Zhu, M.; Korattikara, A.; Fathi, A.; Fischer, I.; Wojna, Z.; Song, Y.; Guadarrama, S.; et al. Speed/Accuracy Trade-Offs for Modern Convolutional Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2017, pp. 7310–7311. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, C.; Ji, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T. D3-YOLOv10: Improved YOLOv10-Based Lightweight Tomato Detection Algorithm Under Facility Scenario. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, Y.; Shinde, K.; Gangan, J.; Firdausi, S.; Bharne, S. Weed Plant Detection from Agricultural Field Images using YOLOv3 Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Jin, X.; Sun, Y.; Che, J.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y. A novel deep learning-based method for detection of weeds in vegetables. Pest Management Science 2022, 78, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Miao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhai, C.; Zhao, C. HAD-YOLO: An Accurate and Effective Weed Detection Model Based on Improved YOLOV5 Network. Agronomy 2025, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.P.; Hughes, D.P.; Salathé, M. Using Deep Learning for Image-Based Plant Disease Detection. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheed, A.; Goyal, M.; Gupta, D.; Khanna, A.; Hassanien, A.E.; Pandey, H.M. An optimized dense convolutional neural network model for disease recognition and classification in corn leaf. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 175, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

- Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, X. Agricultural greenhouses detection in high-resolution satellite images based on convolutional neural networks: Comparison of Faster R-CNN, YOLO v3 and SSD. Sensors 2020, 20, 4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. Self-EMD: Self-Supervised Object Detection without ImageNet. arXiv preprint, 2020; arXiv:2011.13677. [Google Scholar]

- Gunay, M.; Koseoglu, M. Detection of circuit components on hand-drawn circuit images by using faster R-CNN method. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štancel, M.; Hulič, M. An Introduction to Image Classification and Object Detection Using YOLO Detector. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Vol. 2403; 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Roboflow. YOLOv5 is Here: State-of-the-Art Object Detection at 140 FPS, 2020.

- Xu, B.; Cui, X.; Ji, W.; Yuan, H.; Wang, J. Apple Grading Method Design and Implementation for Automatic Grader Based on Improved YOLOv5. Agriculture 2023, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Gao, S.; Peng, H.; Xue, Y.; Han, L.; Ma, G.; Mao, H. Lightweight Detection of Broccoli Heads in Complex Field Environments Based on LBDC-YOLO. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulhandjian, H.; Yang, Y.; Amely, N. Design and Implementation of a Smart Agricultural Robot bullDOG (SARDOG). In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC). IEEE, February 2024, pp. 767–771.

- Fu, C.Y.; Liu, W.; Ranga, A.; Tyagi, A.; Berg, A.C. DSSD: Deconvolutional Single Shot Detector. arXiv preprint, 2017; arXiv:1701.06659. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Hong, X.; Zhu, L. Detecting Small Objects in Thermal Images Using Single-Shot Detector. arXiv preprint, 2021; arXiv:2108.11101. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv preprint, 2019; arXiv:1905.11946. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. EfficientDet vs RTDETRv2: A Technical Comparison for Object Detection, 2023.

- Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Cui, J. Occlusion Robust Wheat Ear Counting Algorithm Based on Deep Learning. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 645899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayhan, A. Artificial Intelligence in Robotics: From Automation to Autonomous Systems. ResearchGate 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Du, S.; Lan, X. A review of object detection based on deep learning. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2020, 79, 23729–23791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Peng, T.; Cao, H.; Xu, Y.; Wei, X.; Cui, B. TIA-YOLOv5: An improved YOLOv5 network for real-time detection of crop and weed in the field. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1091655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.; Magalhães, S.A.; Pinho, T.M.; Cunha, M. Evaluating the Single-Shot MultiBox Detector and YOLO Deep Learning Models for the Detection of Tomatoes in a Greenhouse. Sensors 2021, 21, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X. Edge intelligence: On-demand deep learning model co-inference with device-edge synergy. Proceedings of the 2018 Workshop on Mobile Edge Communications 2018, pp. 31–36.

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. Journal of Field Robotics 2020, 37, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, M.; Shi, J.Q. A Survey on Deep Neural Network Pruning: Taxonomy, Comparison, Analysis, and Recommendations. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Gupta, S. To Prune, or Not to Prune: Exploring the Efficacy of Pruning for Model Compression. arXiv preprint, 2017; arXiv:1710.01878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Xie, C.; Yang, P.; Li, R.; Zhou, M. AgriPest: A Large-Scale Domain-Specific Benchmark Dataset for Practical Agricultural Pest Detection in the Wild. Sensors 2021, 21, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, C.M.; Poulose, A.; Gan, H. Agricultural Object Detection with You Look Only Once (YOLO) Algorithm: A Bibliometric and Systematic Literature Review. arXiv preprint, 2024; arXiv:2401.10379. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, X.; Sobeih, T.; Gaiser, T.; Thuy, N.H.; Behrend, D.; Srivastava, A.K.; Halder, K.; Ewert, F. Deep Learning Meets Process-Based Models: A Hybrid Approach to Agricultural Challenges. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2504.16141. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Yu, H.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sui, Y.; Zhao, R. Research on Agricultural Environmental Monitoring Internet of Things Based on Edge Computing and Deep Learning. Journal of Intelligent Systems 2024, 33, 20230114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.T.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Huang, Z.; Schwing, A.; Brunner, R.; Khachatrian, H.; Karapetyan, H.; Dozier, I.; Rose, G.; et al. Agriculture-Vision: A Large Aerial Image Database for Agricultural Pattern Analysis. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2001.01306 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.s.; Kim, G.T.; Shin, J.; Jang, S.W. Hierarchical Image Quality Improvement Based on Illumination, Resolution, and Noise Factors for Improving Object Detection. Electronics 2024, 13, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiang, J.; Duan, J. A low illumination target detection method based on a dynamic gradient gain allocation strategy. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 29058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldek, C.; Cunningham, J.; Aydin, M.; Sariyildiz, E.; Phung, S.L.; Alici, G. Sensing-based Robustness Challenges in Agricultural Robotic Harvesting. arXiv preprint, 2025; arXiv:2502.12403. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Z.; Jin, H.; Zhen, T.; Sun, F.; Xu, H. Small object recognition algorithm of grain pests based on SSD feature fusion. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43202–43213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwal, A.; Parhar, T.; Yandun, F.; Kantor, G. A Robust Illumination-Invariant Camera System for Agricultural Applications. arXiv preprint, 2021; arXiv:2101.02190. [Google Scholar]

- Bargoti, S.; Underwood, J. Deep Fruit Detection in Orchards. arXiv preprint, 2016; arXiv:1610.03677. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Peng, D.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z.; Yu, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, S. The Accuracy of Winter Wheat Identification at Different Growth Stages Using Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, U.; Liu, J.; Whitaker, J. Transfer Learning: Domain Adaptation. In Deep Learning for NLP and Speech Recognition; Springer, 2019; pp. 495–535. [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migneco, P. Traffic sign recognition algorithm: a deep comparison between YOLOv5 and SSD Mobilenet. Doctoral dissertation, Politecnico di Torino, 2024.

- Albahar, M. A survey on deep learning and its impact on agriculture: challenges and opportunities. Agriculture 2023, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, D.R.; Deepa, N.; Elavarasan, D.; Srinivasan, K.; Chauhdary, S.H.; Iwendi, C. Sensors driven AI-based agriculture recommendation model for assessing land suitability. Sensors 2019, 19, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Marinello, F.; Ercisli, S.; Zhang, Z. A survey of few-shot learning in smart agriculture: developments, applications, and challenges. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanya, V.; Subeesh, A.; Kushwaha, N.; Vishwakarma, D.; Kumar, T.; Ritika, G.; Singh, A. Deep learning based computer vision approaches for smart agricultural applications. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2022, 6, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrast Essenfelder, A.; Toreti, A.; Seguini, L. Expert-driven explainable artificial intelligence models can detect multiple climate hazards relevant for agriculture. Communications Earth & Environment 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Applied Machine Learning Explainability Techniques: Make ML models explainable and trustworthy for practical applications using LIME, SHAP, and more; Packt Publishing Ltd, 2022.

- Guo, Y.; Gao, J.; Tunio, M.H.; Wang, L. Study on the Identification of Mildew Disease of Cuttings at the Base of Mulberry Cuttings by Aeroponics Rapid Propagation Based on a BP Neural Network. Agronomy 2022, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakura, S.; Hirafuji, M.; Ninomiya, S.; Shibasaki, R. Adaptations of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) to Agricultural Data Models with ELI5, PDPbox, and Skater using Diverse Agricultural Worker Data. European Journal of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, R.; Hazrati Fard, S.M.; Kaur, J. Recommendations for ethical and responsible use of artificial intelligence in digital agriculture. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2022, 5, 884192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Khan, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Hussain, I. YOLO Optimization for Small Object Detection: DyFAM, EFRAdaptiveBlock, and Bayesian Tuning in Precision Agriculture. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, X.; Shen, Y.; Xu, J.; Khan, Z. A Single-Stage Navigation Path Extraction Network for agricultural robots in orchards. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2025, 229, 109687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Wu, D.; Wang, J. Enhancing stem localization in precision agriculture: A Two-Stage approach combining YOLOv5 with EffiStemNet. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2025, 231, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.; Kamsu-Foguem, B.; Kamissoko, D.; Traore, D. Deep learning for precision agriculture: A bibliometric analysis. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2022, 16, 200102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Fu, K. Research Progress on Few-Shot Learning for Remote Sensing Image Interpretation. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ren, M. YOLOv8-ACCW: Lightweight grape leaf disease detection method based on improved YOLOv8. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Lin, W.J.; Cheng, H.J.; Hung, C.L.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, S.P. A smartphone-based application for scale pest detection using multiple-object detection methods. Electronics 2021, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasri, F.; Debeir, O. Multimodal Sensor Fusion in Single Thermal Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ACCV 2018 Workshops. Springer; 2019; pp. 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhiary, M.; Hoque, A.; Prasad, G.; Kumar, K.; Sahu, B. Precision Agriculture and AI-Driven Resource Optimization for Sustainable Land and Resource Management. In Smart Water Technology for Sustainable Management in Modern Cities; IGI Global, 2025; pp. 197–232.

- Zhao, S.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, S. Tomato Leaf Disease Diagnosis Based on Improved Convolution Neural Network by Attention Module. Agriculture 2021, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Khan, Z.; Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Duan, S. Optimization of Improved YOLOv8 for Precision Tomato Leaf Disease Detection in Sustainable Agriculture. Sensors 2025, 25, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanya, K.; Gopal, P.; Srinivasan, V. Deep learning in agriculture: challenges and future directions. Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture 2022, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Padhiary, M.; Hoque, A.; Prasad, G.; Kumar, K.; Sahu, B. The Convergence of Deep Learning, IoT, Sensors, and Farm Machinery in Agriculture. In Designing Sustainable Internet of Things Solutions for Smart Industries; IGI Global, 2025; pp. 109–142.

- Zheng, W.; Cao, Y.; Tan, H. Secure sharing of industrial IoT data based on distributed trust management and trusted execution environments: a federated learning approach. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 21499–21509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Kumar, P. Comparative study of YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS for agriculture application. In 2024 11th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN) (pp. 72-77) 2024.

- Padhiary, M.; Kumar, R. Enhancing Agriculture Through AI Vision and Machine Learning: The Evolution of Smart Farming. In Advancements in Intelligent Process Automation; IGI Global, 2025; pp. 295–324.

| Model | Year | Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-CNN | 2014 | Two-stage | Region proposals + CNN classification [35] |

| Fast R-CNN | 2015 | Two-stage | ROI pooling, faster training [36] |

| Faster R-CNN | 2015 | Two-stage | Integrated RPN for proposal generation [37] |

| YOLOv1 | 2016 | One-stage | Unified detection and classification [38] |

| YOLOv3 | 2018 | One-stage | Multi-scale prediction, Darknet-53 [39] |

| YOLOv7 | 2022 | One-stage | E-ELAN optimization, fast and accurate [40] |

| SSD | 2016 | One-stage | Multi-box detection with multiple feature maps [41] |

| Task | Application Example | Reference | Algorithmic Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Detection | YOLOv7 for grapevine powdery mildew detection | Sun et al. (2025) | Improved YOLOv7 with backbone pruning |

| and feature enhancement for orchard environments | |||

| Disease Detection | RetinaNet for multi-crop disease classification | Duan et al. (2024) | YOLOv8-GDCI with global detail-context interaction |

| for detecting small objects in plant parts | |||

| Fruit Counting | YOLOv5 applied to apple counting | Ma et al. (2024) | Reviewed deep learning maturity detection |

| techniques including object-level fruit analysis | |||

| Fruit Counting | SSD for citrus fruit detection in orchards | Sa et al. (2016) | Developed SSD-based detection with real-time |

| capability using multispectral image fusion | |||

| Weed Detection | DeepWeeds dataset classification using YOLOv3 | Olsen et al. (2019) | Introduced multiclass weed dataset; evaluated |

| YOLOv3 under real-world conditions | |||

| Weed Detection | Improved YOLOv8 for weed detection in crop field | Jia et al. (2024) | Enhanced YOLOv8 with attention-guided dual-layer |

| feature fusion for dense weed clusters | |||

| Spraying Robotics | Precision pesticide application in vineyards | Khan et al. (2025) | YOLOv7 improved with custom feature extractors |

| targeting grape leaf health conditions | |||

| Spraying Robotics | Precision pesticide application in orchards | Khan et al. (2024) | Real-time instance segmentation of canopies |

| using refined YOLOv8 architecture |

| Dataset | Images | Crop/Weed Types | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PlantVillage | 50,000+ | 38 crop-disease pairs | Controlled lab images [86] |

| DeepWeeds | 17,509 | 9 weed species | Field conditions, weeds in Australia [64] |

| GrapeLeaf Dataset | 5,000+ | Grapevine diseases | Grape disease segmentation [76] |

| DeepFruit | 35,000+ | Apple, mango, citrus | Fruit detection for yield estimation [87] |

| Model | Dataset | Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv7 | Grape disease detection | High accuracy, fast inference | Suitable for real-time deployment [29,76] |

| YOLOv3 | Weed detection (DeepWeeds) | Good balance of speed and accuracy | Field condition tested [64,109,110,111] |

| Faster R-CNN | PlantVillage | High detection accuracy | Slower but more robust [37,112,113] |

| RetinaNet | Multi-crop disease datasets | Handles class imbalance well | Useful for rare diseases [114,115] |

| Challenge | Key Contributions |

|---|---|

| Tiny Object Detection (aphids, mildew spots) | Focal Loss to address class imbalance [114] |

| Domain Shift (lab to field conditions) | Domain adaptation techniques for agriculture [77] |

| Limited Labeled Data | Semi-supervised learning for crop disease detection [78] |

| Explaining Model Decisions (Explainability) | Visualization methods for deep model decisions [78] |

| Lighting and Background Variations | Robust early disease detection in varying environments [73] |

| Real-Time Deployment on Edge Devices | Lightweight CNN design for embedded detection [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).