Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

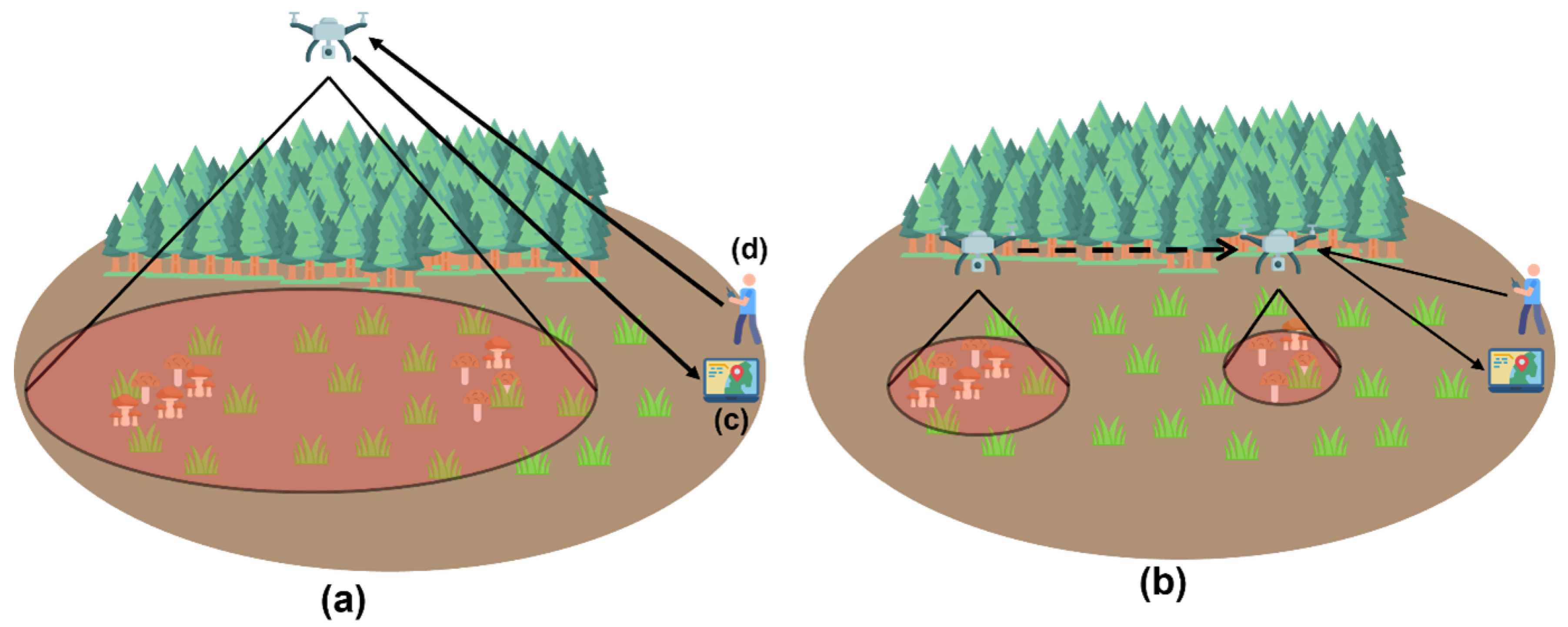

2.1. Data Acquisition

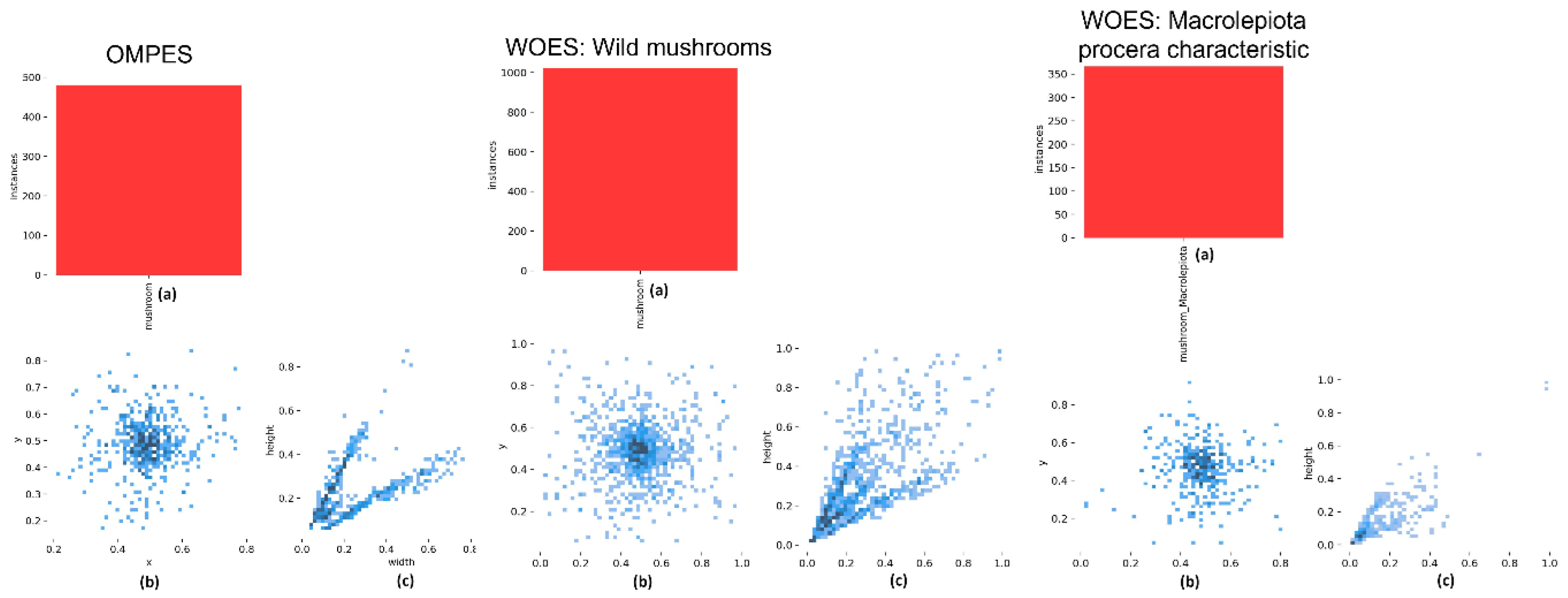

2.2. Data Preparation

2.3. The Main Methodology

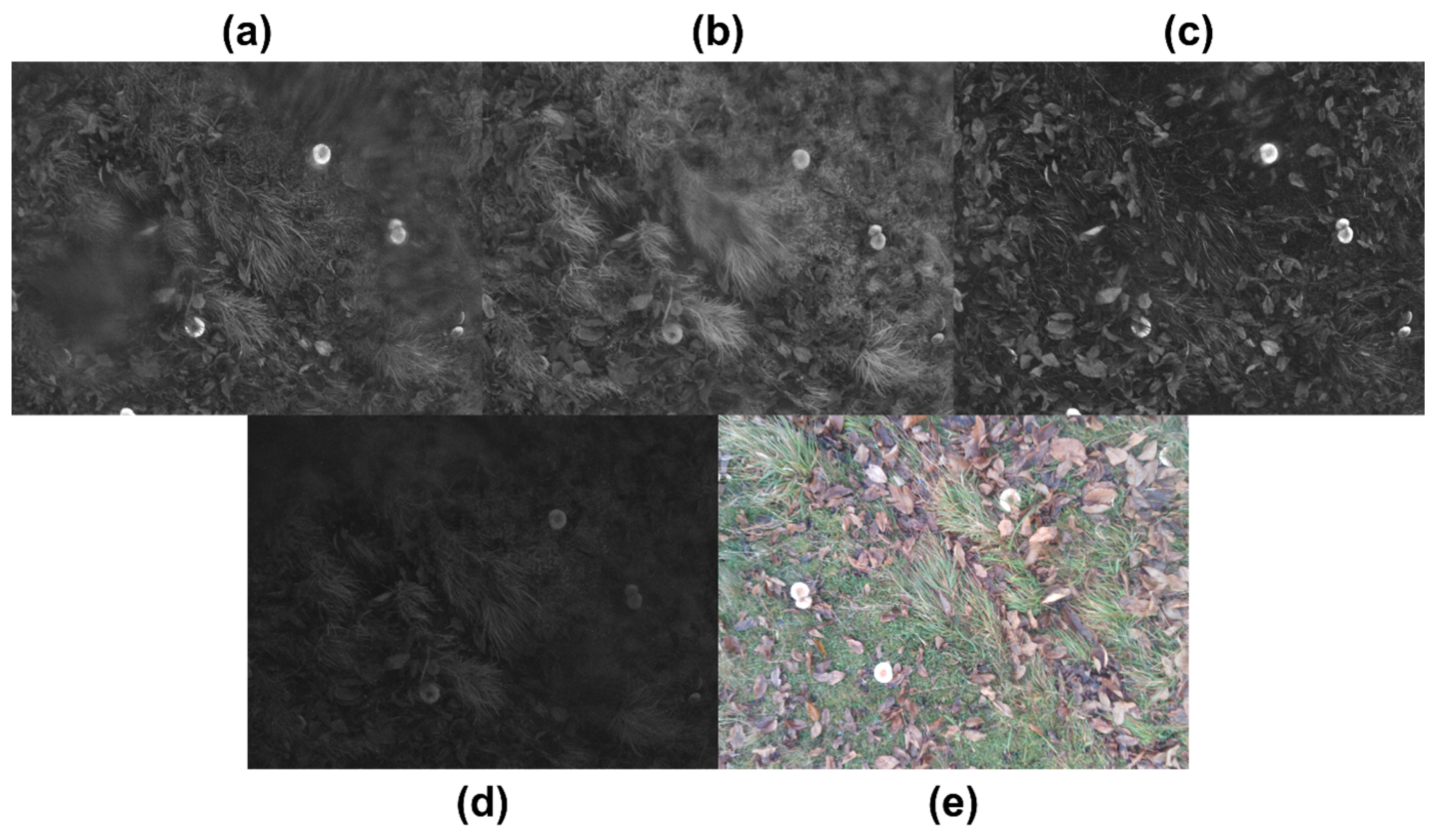

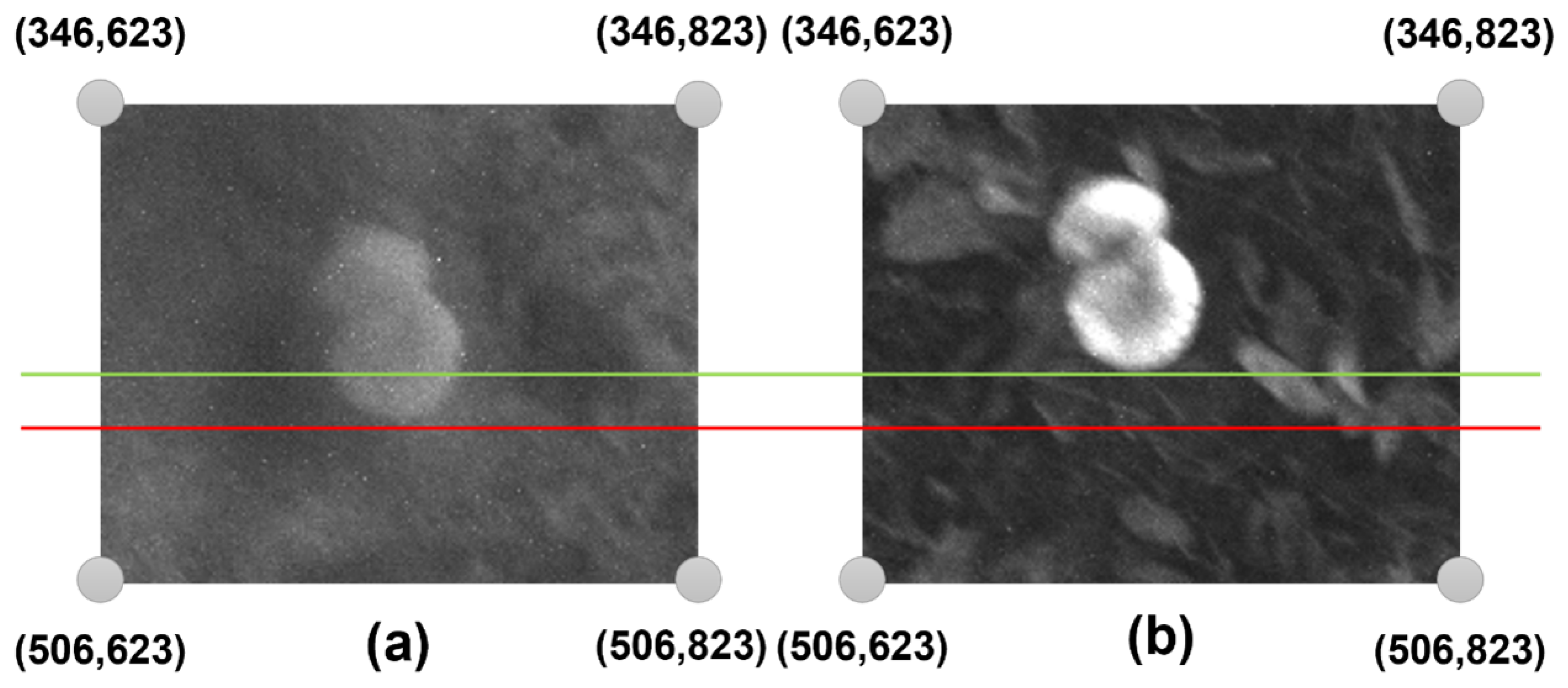

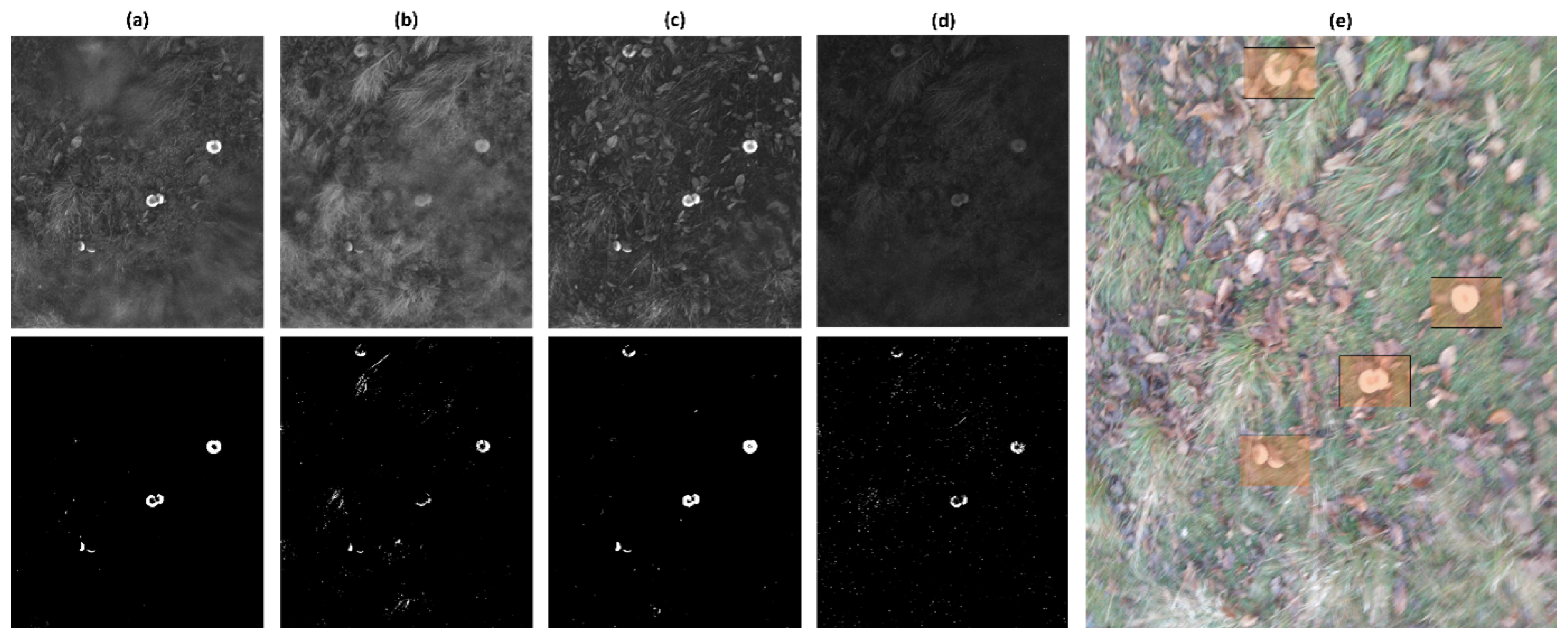

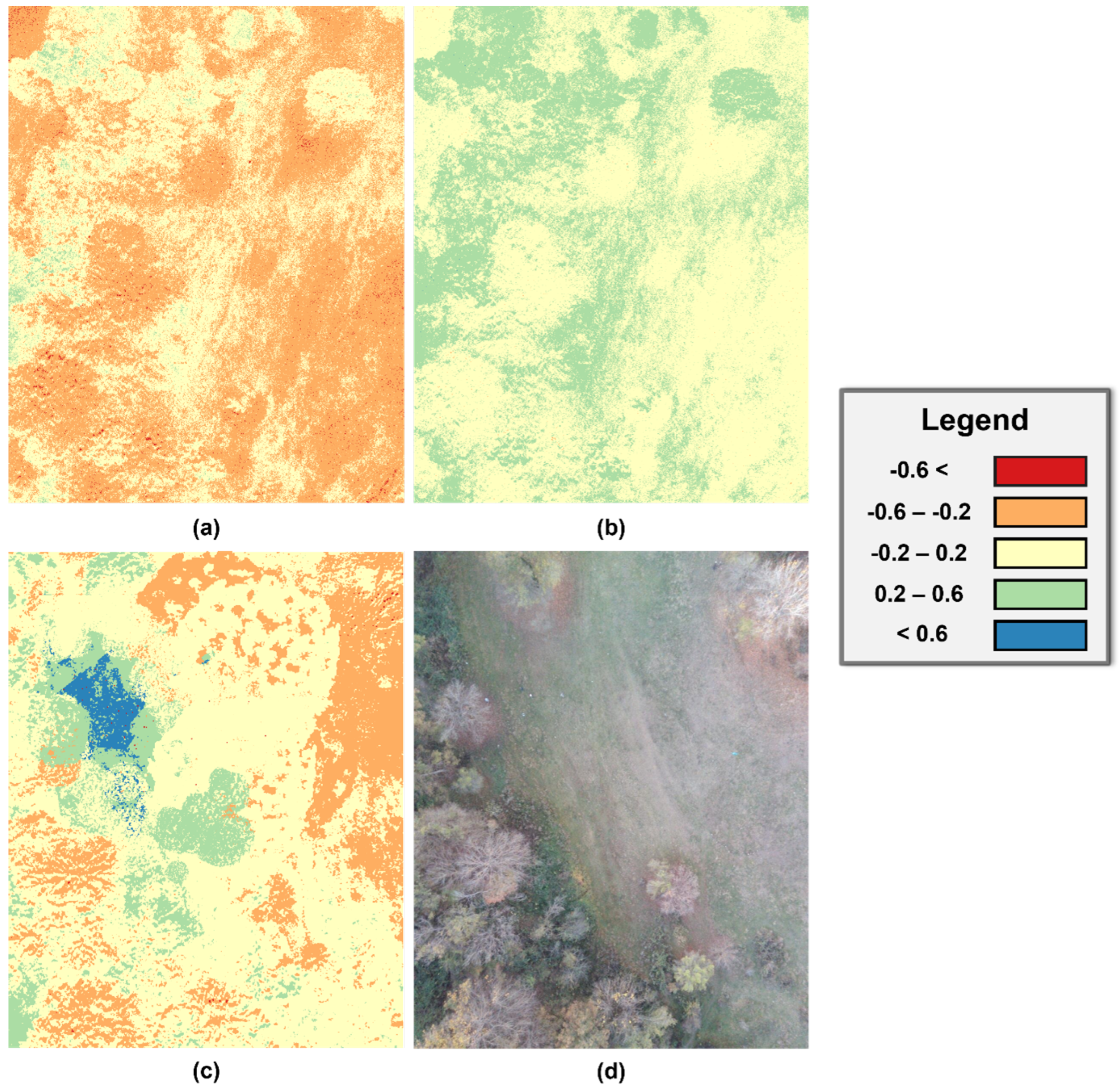

2.4. Phase One

- Processing the band images to adjust them to the selected spectrum (REDEDGE).

- Calculating the Normalized Difference Red Edge Index (NDRE) vegetation index.

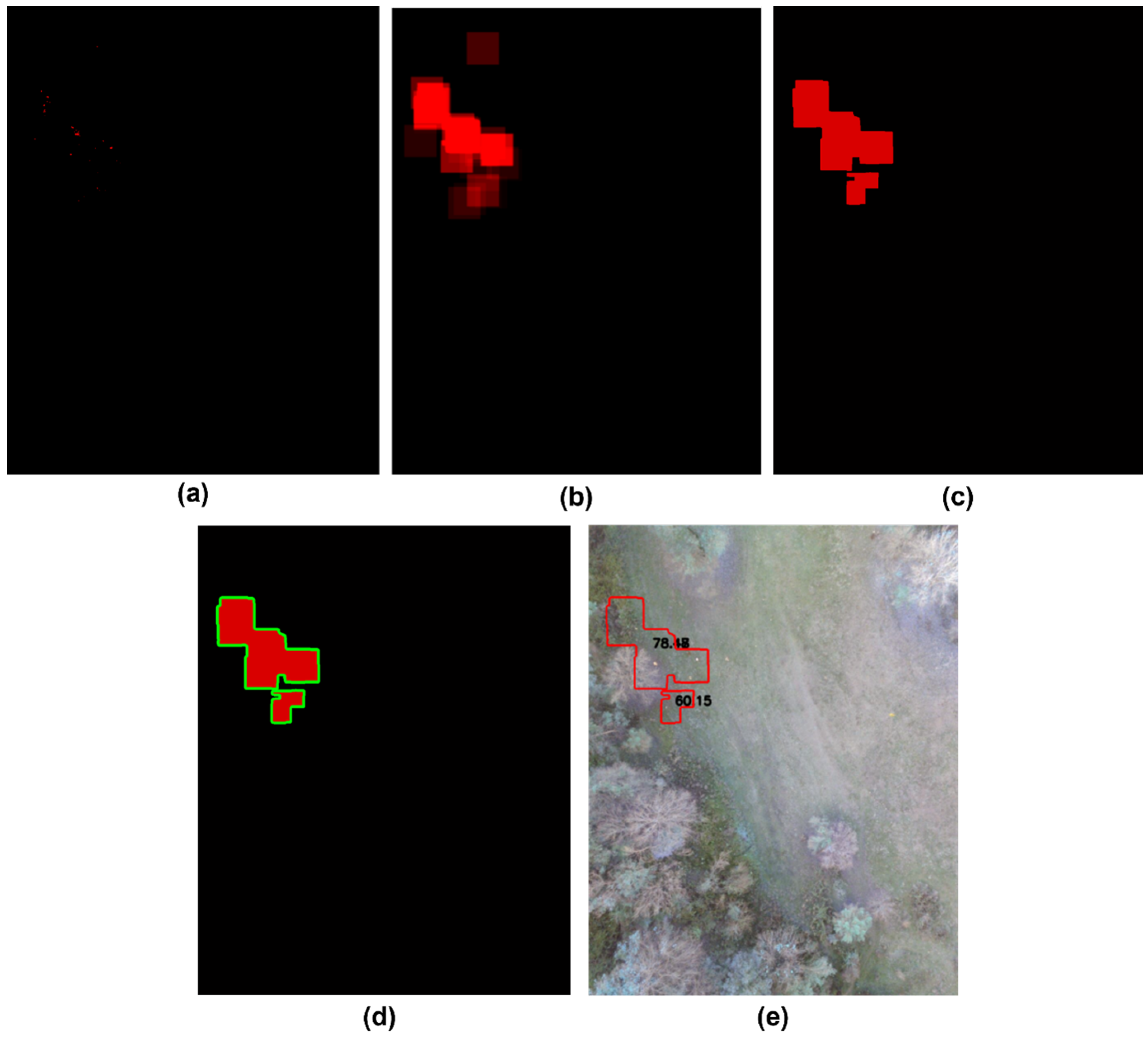

- Identifying potential locations with wild mushrooms.

- Calculating the probability of finding wild mushrooms in each location.

- Sending the processed RGB spectrum with the locations and probability of the wild mushrooms to a PNG image file via WiFi to the base station.

- Samples: The data type should be np.float32, and each feature should be placed in a separate column.

- Nclusters (K): Number of clusters required.

- Criteria: It is the condition for terminating an iteration. When these conditions are met, the algorithm stops iterating.

- Attempts: Specifies the number of times the algorithm is conducted with different beginning labellings. The method returns the labels that result in the highest degree of compactness. This density is returned as the output.

- Flags: This flag specifies how initial centres are obtained.

2.5. Phase Two

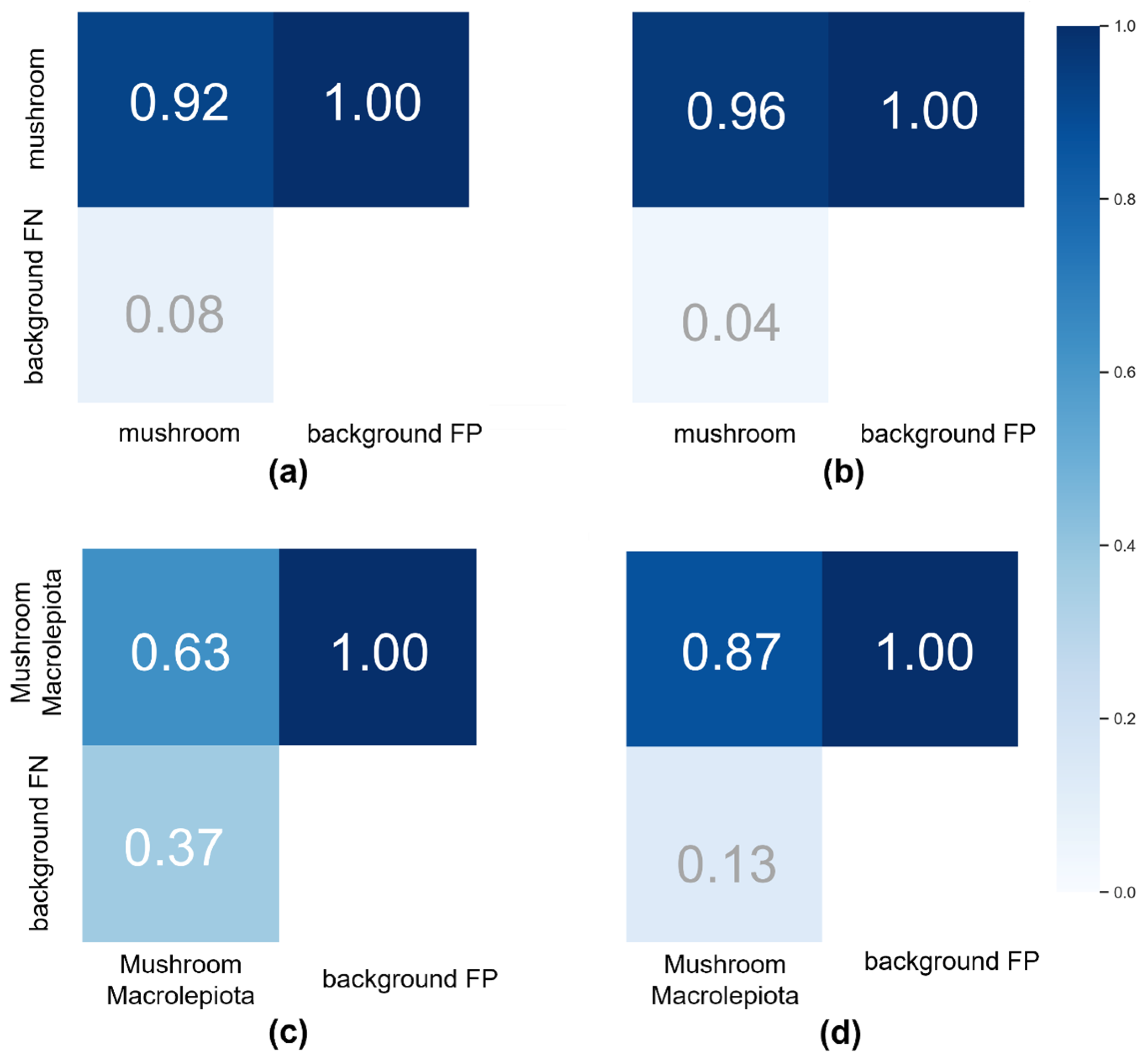

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Park, H. J. (2022). Current uses of mushrooms in cancer treatment and their anticancer mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(18), 10502. [CrossRef]

- Garibay-Orijel, R., Córdova, J., Cifuentes, J., Valenzuela, R., Estrada-Torres, A., & Kong, A. (2009). Integrating wild mushrooms use into a model of sustainable management for indigenous community forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 258(2), 122–131. [CrossRef]

- Agrahar-Murugkar, D., & Subbulakshmi, G. (2005). Nutritional value of edible wild mushrooms collected from the Khasi hills of Meghalaya. Food Chemistry, 89(4), 599–603. [CrossRef]

- Rózsa, S., Andreica, I., Poșta, G., & Gocan, T. M. (2022). Sustainability of Agaricus blazei Murrill mushrooms in classical and semi-mechanized growing system, through economic efficiency, using different culture substrates. Sustainability, 14(10), 6166. [CrossRef]

- Moysiadis, V., Sarigiannidis, P., Vitsas, V., & Khelifi, A. (2021). Smart farming in Europe. Computer Science Review, 39, 100345. [CrossRef]

- Boursianis, A. D., et al. (2022). Internet of Things (IoT) and agricultural unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in smart farming: A comprehensive review. Internet of Things, 18, 100187. [CrossRef]

- Amatya, S., Karkee, M., Zhang, Q., & Whiting, M. D. (2017). Automated detection of branch shaking locations for robotic cherry harvesting using machine vision. Robotics, 6(4), 31. [CrossRef]

- Uryasheva, A., et al. (2022). Computer vision-based platform for apple leaves segmentation in field conditions to support digital phenotyping. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 201, 107269. [CrossRef]

- Zahan, N., Hasan, M. Z., Malek, M. A., & Reya, S. S. (2021). A deep learning-based approach for edible, inedible and poisonous mushroom classification. Proceedings of ICICT4SD, 440–444. [CrossRef]

- Picek, L., et al. (2022). Automatic fungi recognition: Deep learning meets mycology. Sensors, 22(2), 633. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. J., Aime, M. C., Rajwa, B., & Bae, E. (2022). Machine learning-based classification of mushrooms using a smartphone application. Applied Sciences, 12(22), 11685. [CrossRef]

- Siniosoglou, I., Argyriou, V., Bibi, S., Lagkas, T., & Sarigiannidis, P. (2021). Unsupervised ethical equity evaluation of adversarial federated networks. ACM International Conference Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ibarra, E., Gómez-Martín, M. B., & Armesto-López, X. A. (2019). Climatic and socioeconomic aspects of mushrooms: The case of Spain. Sustainability, 11(4), 1030. [CrossRef]

- Barea-Sepúlveda, M., et al. (2022). Toxic elements and trace elements in Macrolepiota procera mushrooms from southern Spain and northern Morocco. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 108, 104419. [CrossRef]

- Adamska, I., & Tokarczyk, G. (2022). Possibilities of using Macrolepiota procera in the production of prohealth food and in medicine. International Journal of Food Science, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chaschatzis, C., Karaiskou, C., Goudos, S. K., Psannis, K. E., & Sarigiannidis, P. (2022). Detection of Macrolepiota procera mushrooms using machine learning. IEEE WSCE, 74–78. [CrossRef]

- Wei, B., et al. (2022). Recursive-YOLOv5 network for edible mushroom detection in scenes with vertical stick placement. IEEE Access, 10, 40093–40108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., et al. (2022). Research and application of wild mushrooms classification based on multi-scale features to realize hyperparameter evolution. Journal of Graphics, 43(4), 580. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Zhang, Y., Sun, X., Dai, H., & Chen, X. (2021). Intelligent solutions in chest abnormality detection based on YOLOv5 and ResNet50. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., & Su, B. (2017). Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. Journal of Sensors, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C., Jaganathan, V., Sivakumar, A. N., Czarnecki, J. M. P., & Chowdhary, G. (2022). NDVI/NDRE prediction from standard RGB aerial imagery using deep learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 203, 107396. [CrossRef]

- Solano-Alvarez, N., et al. (2022). Comparative analysis of the NDVI and NGBVI as indicators of the protective effect of beneficial bacteria in conditions of biotic stress. Plants, 11(7), 932. [CrossRef]

- Steven, M. D. (1998). The sensitivity of the OSAVI vegetation index to observational parameters. Remote Sensing of Environment, 63(1), 49–60. [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, D. K., & Nielsen, P. (2022). Comparative analyses of unsupervised PCA K-means change detection algorithm from the viewpoint of follow-up plan. Sensors, 22(23), 9172. [CrossRef]

| Band | Left | Up |

|---|---|---|

| NIR | 16 | 24 |

| RED | 35 | 15 |

| GREEN | 29 | 2 |

| RGB | 21 | 20 |

| Band | Lower Threshold (kHz) | Upper Threshold (kHz) |

|---|---|---|

| NIR | 38 | 40 |

| RED | 37 | 39 |

| GREEN | 38 | 40 |

| RGB | 16 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).