1. Introduction

Bladder cancer is the 6th most common cancer worldwide with over 440,000 newly diagnosed cases annually and 160,000 fatalities [

1]. The estimated number of new bladder cancer cases within the UK population alone is 10,200 with 5,400 expected deaths annually, a number which unfortunately continues to rise steadily [

2].

Bladder cancer was the first cancer to be associated with industrialization due to the increased cancer cases amongst dye workers who worked with aromatic amines. Other risk factors for bladder cancer are known to include old age, cigarette smoking, male gender, arsenic in drinking water, and infection of the bladder [

3,

4,

5].

Infectious agents have been recognised as direct carcinogens or promoters of human cancer. Particularly, high-risk Human Papillomaviruses (HR-HPVs) have been identified as carcinogenic agents in certain cancer types. HPVs are small, non-enveloped viruses belonging to a large family of double-stranded circular DNA viruses. They are able to infect epithelial surfaces, such as the skin and genital areas, through sexual or skin-to-skin contact, leading to the development of hyper-proliferative lesions known as warts or papillomas. Currently, more than 200 HPV types have been identified and categorised as either "low risk" or "high-risk" based on their association with neoplastic growth. While low-risk HPV types cause benign lesions, high-risk types are strongly linked to the development of cancer [

6,

7].

Long-term viral persistence is a critical factor in the development of malignancy, as it requires the evasion of the body's immune attacks and clearance mechanisms. Research has demonstrated that HPVs, like many other viruses, employ various strategies to subvert an effective immune response, potentially leading to delays or failure in clearing HPV infections [

7,

8,

9]. HPVs produce three major oncoproteins, E5, E6, and E7, which interact with the human immune system to downregulate key components such as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class I, p53, and Rb, respectively. While the immune system typically clears infections in a timely manner, albeit after a delay period, HPV can evade immune surveillance and persist under specific environmental conditions, ultimately leading to the progression of malignant diseases [

10].

HR-HPV types are considered to be the predominant cause of about 95% of cervical cancer cases [

11]. HPVs have also been linked to a significant number of other cancers, such as vaginal, penile, anal, and oropharynx cancers [

12]. These findings suggest that HPV might be able to travel from the initial infection site to various other organs, potentially contributing to cancer development in different parts of the body. Interestingly, our published research has found solid evidence of 10 HR-HPVs, aside from types 16 and 18, in freshly collected human breast cancer tissue, as well as human prostate tissue [

13,

14]. This discovery provides a strong foundation for further research into this important area of women's and men’s health. It's crucial that we continue studying and understanding the connections between HPV and various types of cancer.

The relationship between bladder cancers and HPV types 16 and 18 as possible carcinogen was first proposed by Li et al. (2011) stating that high-risk HPV may play a contributing role in bladder carcinogenesis. Since then, several studies focusing on the relationship between HPV and bladder cancers have rejected such an association. Schmid et al, 2015 did not detect any HPV DNA in 109 bladder cancer samples [

15,

16].

It had been suggested that the urethra may act as a reservoir for HPV [

17]. However, Griffith and Mellon (2000) revealed the presence of HPV in 6% of urethral swabs, compared to 29% in bladder tissue, hence some authors have suggested a link between HPV and bladder cancer [

18]. Results of studies so far have been highly controversial lacking concrete evidence to suggest whether there is any direct link between chronic HPV infection and bladder cancer. Considering the broad interest of HR-HPV and Bladder cancer, it is considered very important to verify the prevalence of various other HR-HPV types, not just HPV16 and HPV18 in bladder cancer, worldwide.

According to the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted in the UK to investigate the role of HR-HPV infection in the carcinogenesis of the bladder, despite its significant medical importance and high incidence rate among the global population. Therefore, we aimed to examine the presence and expression of 12 HR-HPV types in biopsies of both benign and malignant fresh bladder tissues obtained from patients in the UK by employing a highly sensitive molecular analysis method. Our study revealed that HR-HPV DNA was present in 33.3% of malignant bladder tissues, with HPV16, HPV35, and HPV52 being the most frequently detected genotypes. Additionally, 81% of HR-HPV DNA-positive samples showed expression of the E7 oncoprotein, suggesting active viral involvement in tumorigenesis. These findings provide novel insights into the potential role of HR-HPV in a subset of bladder cancers in the UK population and highlight the need for further investigations into the mechanistic relationship between HPV infection and bladder carcinogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of Patients and Prostate Tissue Specimen Collection

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Research Authority NHS (NRES Committee East Midlands – Leicester Central, UK; REC reference: 17/EM/0393). All procedures followed approved ethical guidelines and regulations. Following written informed consent, a total of 55 fresh bladder tissue specimens (51 malignant and 4 benign) were aseptically collected by a single surgical team over a two-year period. Tissues were immediately preserved in AllProtect reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to stabilize DNA, RNA, and proteins. All specimens underwent histopathological evaluations at the Kingston Hospital Histopathology Department, London, UK.

2.2. DNA Extraction and Purification

To avoid cross-contamination during tissue handling, strict aseptic techniques were applied using disposable items such as gloves, sterile surgical blades, and tubes. Total cellular DNA, RNA, and proteins were extracted simultaneously from bladder tissue specimens using the GenElute RNA/DNA/Protein Purification Plus Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, approximately 20–30 mg of each bladder tissue specimen was accurately weighed and homogenized in lysis buffer using a TissueLyser® (Qiagen) and QIAshredder spin columns (Qiagen). Homogenized lysates were transferred to genomic DNA purification columns to selectively bind genomic DNA, followed by washing and elution using the provided elution buffer. The concentration and purity of extracted nucleic acids were assessed using a NanoVue Plus spectrophotometer (GE Life Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA).

2.2. Detection and Genotyping of HPV DNA

To detect and genotype 12 high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) subtypes, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed using the HPV-HCR Genotype-Eph kit (AmpliSens, Bratislava, Slovak Republic) on purified DNA from bladder tissue specimens. To minimize contamination risks, DNA extraction and PCR assays were conducted in separate laboratories under stringent aseptic conditions. Multiplex PCR was performed by simultaneously amplifying four HPV target regions within each tube, enabling the detection of the following HR-HPV groups: HPV types 16/31/33/35 (tube 1), HPV 18/39/45/59 (tube 2), and HPV 52/56/58/66 (tube 3). This methodology permitted identification of single HPV infections as well as co-infections. PCR reactions for each sample were performed in triplicate to validate data reliability. Amplification of the β-globin gene (723 bp fragment) served as an internal control for DNA integrity in all samples.

Amplified PCR products and HPV type-specific positive controls were analysed by electrophoresis on 3% (w/v) agarose gels stained with SYBR Safe (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The gel was visualized and documented under ultraviolet illumination using a Gel Doc XR+ System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.3. HPV DNA Sequencing

To confirm the presence and genotype accuracy of HPV DNA, PCR products from HPV-positive bladder cancer samples were purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and subsequently subjected to direct sequencing using an Applied Biosystems 3730xL DNA Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequencing results were analysed and confirmed using the NCBI BLAST database for HPV sequence validation.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

To confirm HPV gene expression at the protein level, HPV DNA-positive bladder cancer tissue specimens underwent immunohistochemical analysis for HPV E7 protein using an anti-HPV E7 monoclonal antibody (Cervimax, Valdospan GmbH, Austria) that targets a broad range of HR-HPV types. IHC staining was performed using an automated BenchMark Ultra system (VENTANA, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The HPV E7 monoclonal antibody was applied at a dilution of 1:100 and incubated at 36°C for one hour. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III (CIN III) tissue blocks served as positive controls, while slides incubated without primary antibody served as negative controls. The staining intensity and positivity were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) with the IHC Analyzer plugin. Staining intensity was scored as negative (no staining detected), positive (visible only at high magnification), or strongly positive (visible clearly at low magnification).

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Characteristics of the Patients

The clinical and pathological characteristics of the bladder specimens analysed in this study are summarized in

Table 1. All pathological diagnoses were confirmed by the histopathology department of Kingston Hospital, London, UK, based on comprehensive histological evaluation of biopsy specimens.

A total of 55 fresh bladder tissue samples (47 male, 8 female) were collected from patients undergoing evaluation for suspected bladder cancer at the Urology Department of Kingston Hospital. Patient age ranged from 45 to 96 years at the time of biopsy, with the following age distribution: 6 (10.9%) patients younger than 60 years, 10 (18.2%) aged 61–70 years, 18 (32.7%) aged 71–80 years, and 21 (38.2%) patients older than 81 years.

Histopathological examination identified 51 malignant bladder cancer samples, including 49 (89.1%) transitional cell carcinoma (urothelial carcinoma) and 2 (3.6%) squamous cell carcinoma. The remaining 4 (7.3%) samples were benign bladder lesions.

3.2. Detection of HR-HPV DNA in Bladder Cancer Specimens

Extracted DNA from all 55 bladder tissue specimens was analysed for the presence of 12 high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) types (HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 66) using multiplex PCR. Each PCR experiment was conducted in triplicate to ensure data reliability and reproducibility. HPV-positive and negative controls were included in every run. Additionally, amplification of a 723 bp fragment of the β-globin gene served as an internal control to confirm DNA integrity and suitability of each sample.

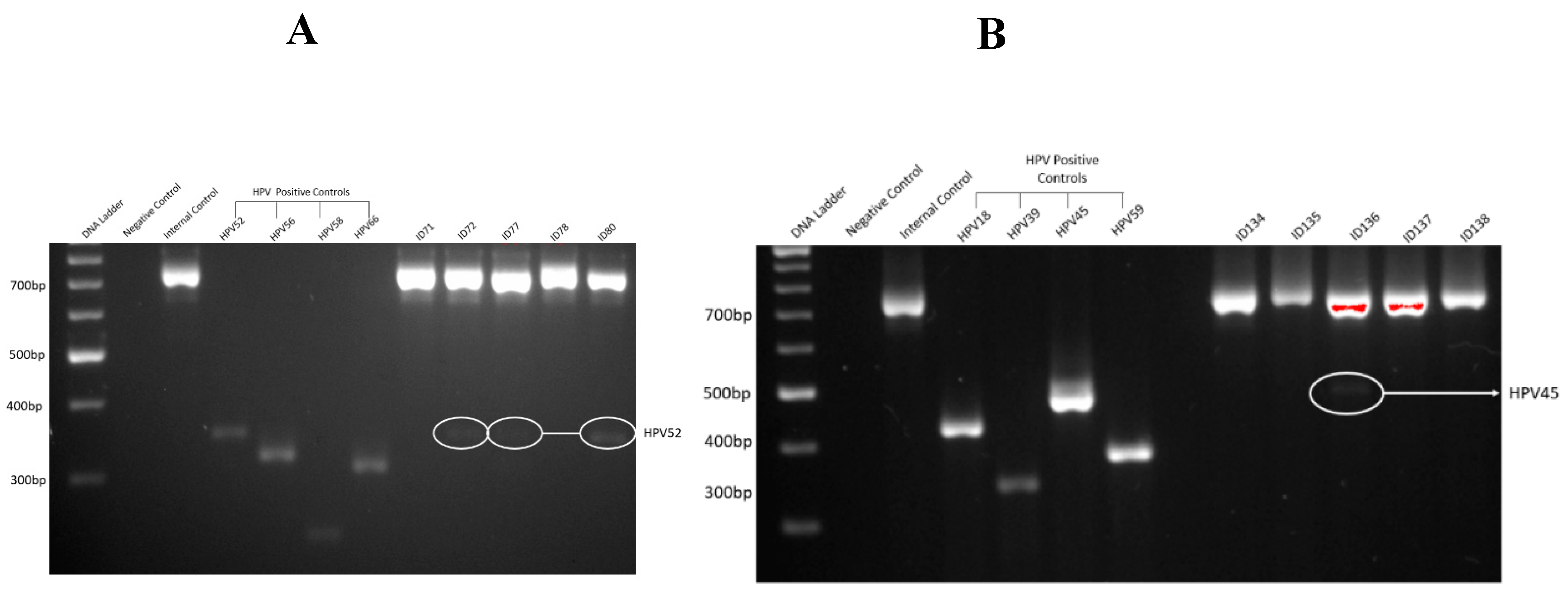

As shown in

Figure 1, gel electrophoresis demonstrated clear amplification products for HPV-positive controls, with no amplification observed in negative controls, indicating the absence of contamination and validating the efficiency and specificity of the PCR assay.

Figure 1A,B illustrate representative examples of successful PCR amplification for HR-HPV in bladder cancer specimens.

3.3. Sanger Sequencing Results

All HR-HPV-positive bladder samples identified by PCR were subjected to Sanger sequencing to confirm PCR-based genotyping results. Additionally, selected HPV-negative samples were sequenced as controls. BLAST analysis of sequencing results demonstrated greater than 90% concordance with PCR-amplified HPV-positive products. Sequencing data were consistent with PCR results, providing strong validation for the accuracy and specificity of the PCR assays. Representative chromatograms from Sanger sequencing analysis are presented in

Figure 2.

3.4. Prevalence and Distribution of HR-HPV Genotypes in Bladder Cancer

Among the 51 malignant bladder samples, HR-HPV DNA was detected in 17 cases (33.3%). The most identified genotypes were HPV16, HPV35, and HPV52, each detected in 5 out of 49 (10.2%) transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) samples (

Table 2). Other detected genotypes included HPV33, HPV39, HPV45, HPV59, and HPV66, though at lower frequencies. HPV18, HPV31, HPV56, and HPV58 were not detected in any sample.

Table 2 details the genotype-specific distribution of HR-HPVs by tumor grade. HPV16 and HPV35 were each detected across both low- and high-grade tumors, while HPV52 was predominantly observed in Grade 1 TCC cases (80%). Interestingly, HPV39 and HPV59 were identified only in Grade 3 tumors, which may suggest a link between specific genotypes and disease aggressiveness; however, further research with larger sample sizes is required to validate these patterns.

3.5. Frequency and Grade-Based Analysis of HPV Co-Infection

Of the 17 HR-HPV-positive TCC cases, 6 samples (12.2%) demonstrated co-infection with multiple HR-HPV genotypes (

Table 3). Co-infections were more frequently observed in Grade 1 tumours (3 out of 16, or 19%) compared to Grade 3 (2/19, 11%) and Grade 2 (1/14, 7%). This may suggest that co-infections can occur early in tumour development, although due to the limited number of cases, no statistically significant association could be drawn between co-infection status and tumour grade.

Table 3 outlines the number and percentage of co-infections stratified by tumour grade, showing that HPV co-infection is not restricted to higher-grade malignancies and may play a role at different stages of tumour evolution.

3.6. HPV Co-Infection Patterns and Combinatorial Genotypes

To understand the types of co-infection,

Table 4 presents the specific genotype combinations detected in co-infected bladder cancer tissues. Double HPV infections were observed in four cases, including combinations such as HPV16–HPV39, HPV35–HPV66, HPV52–HPV66, and HPV45–HPV59. Two samples showed triple infections: HPV16–HPV33–HPV52 and HPV35–HPV45–HPV59. These findings suggest that a subset of bladder tumors may harbor multiple oncogenic HPV types concurrently, potentially enhancing viral persistence, immune evasion, or oncogenic transformation. The implications of these co-infections in bladder carcinogenesis remain unclear and merit further investigation.

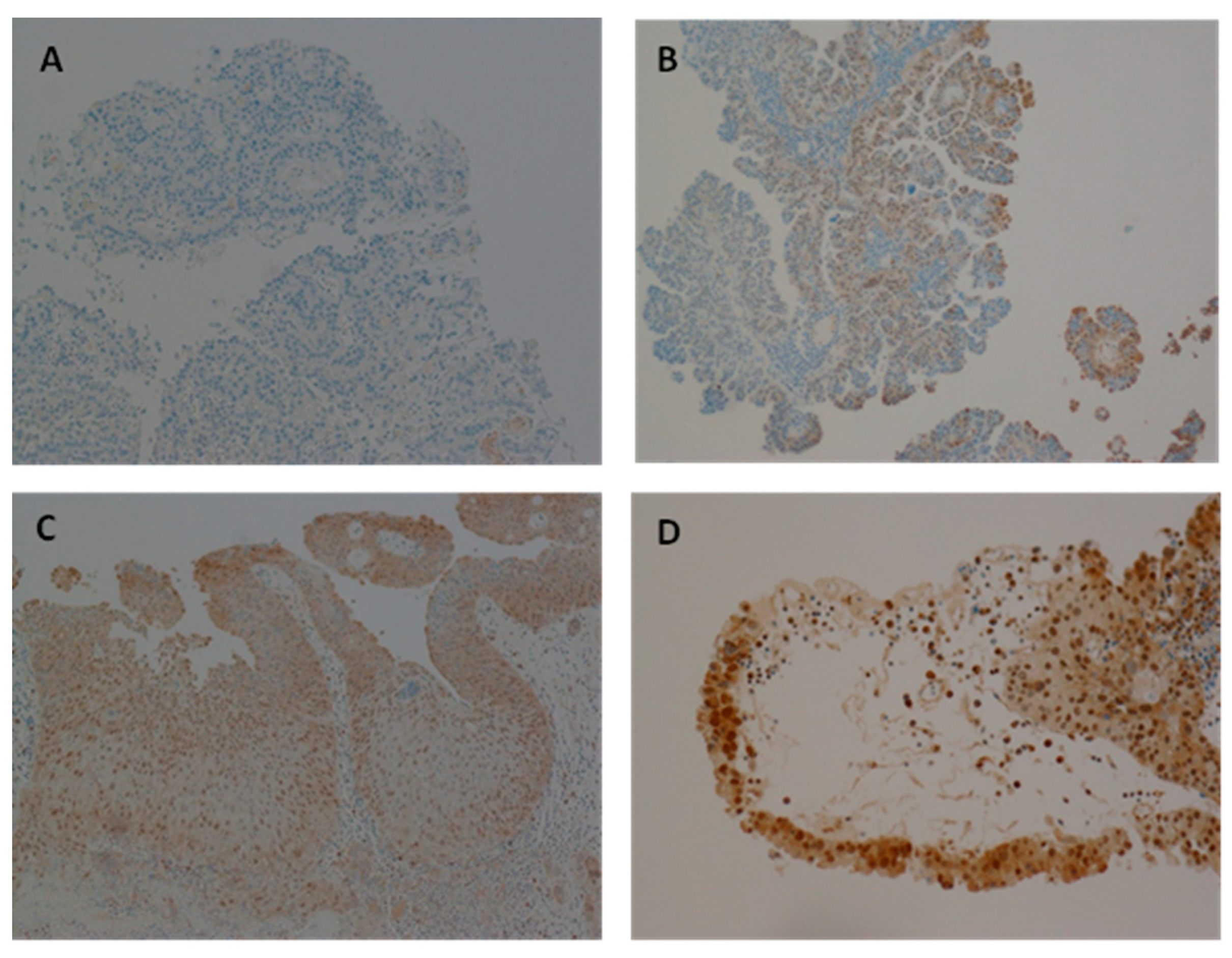

3.7. The Expression of HPV Protein in Samples Positive for HPV

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was performed to investigate HPV E7 oncoprotein expression in all 55 bladder specimens, including both benign and malignant samples. HPV E7 expression was clearly detectable in 13 out of 16 (81%) HPV DNA-positive cancer samples. In contrast, no E7 expression was detected in HPV DNA-negative samples. Additionally, three HPV DNA-positive samples did not exhibit detectable HPV E7 expression, possibly suggesting either an early stage of infection or clearance of the virus by the host immune response (a 'hit-and-run' mechanism). These findings are summarized in

Table 4.6 and were verified by a consultant pathologist at Kingston Hospital.

Representative immunohistochemical staining patterns for HPV E7 expression in bladder cancer tissues are shown in

Figure 3. HPV E7 expression was absent in the HPV DNA-negative bladder cancer sample (

Figure 3A), serving as a negative control. In contrast,

Figure 3B illustrates a HPV DNA-positive bladder cancer sample exhibiting weak E7 expression, while

Figure 3C,D depict HPV DNA-positive samples with moderate and strong E7 expression, respectively. This gradation in staining intensity highlights the variability in HPV E7 protein levels among positive cases, which may reflect differences in viral load, stage of infection, or the extent of viral gene expression and integration within the host genome.

4. Discussion

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most prevalent sexually transmitted infections globally, with most sexually active individuals acquiring it during their lifetime. While HPV is well recognized as a causal factor in cervical and several anogenital cancers [

6,

11,

12,

13], its role in bladder carcinogenesis remains a subject of debate. Bladder cancer is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, with a significant and steadily increasing incidence in both men and women [

1,

2]. However, the presence and pathogenic role of high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) in bladder cancer, especially within the UK population, has not been adequately investigated.

In this study, HR-HPV DNA was detected in

17 out of 51 malignant bladder samples (33.3%), using sensitive multiplex PCR and confirmed through Sanger sequencing. Among the 12 HR-HPV types analysed,

HPV16, HPV35, and HPV52 were the most prevalent, each found

in 5 out of 49 transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) samples (

Table 2). Other genotypes detected at lower frequencies included

HPV33, HPV39, HPV45, HPV59, and HPV66, whereas

HPV18, HPV31, HPV56, and HPV58 were not identified in any of the specimens. The detection of diverse HR-HPV types, beyond the commonly studied HPV16 and HPV18, underscores the importance of broader genotyping in HPV-related cancer research [

6,

14].

These findings partially align with those of Li et al. (2011), who also identified HPV16 as the most prevalent genotype in bladder cancers but reported HPV18 as less frequently involved [

15]. In contrast, Jørgensen and Jensen (2020) and Yan et al. (2021) found HPV18, HPV31, and HPV33 to be among the dominant types in bladder tissues in other regions [

19,

20]. The absence of these types in our cohort may reflect differences in regional prevalence, host genetics, or the impact of HPV vaccination programs in the UK, which primarily target HPV16 and HPV18 [

24].

The distribution of HR-HPV genotypes across tumour grades in

Table 2 revealed that HPV52 was most commonly detected in Grade 1 tumours, while HPV39 and HPV59 were found only in Grade 3, raising the possibility of genotype-specific associations with tumour aggressiveness. However, due to the small sample size, these trends require further investigation.

Of the 17 HR-HPV-positive bladder cancers, 6 cases (12.2%) exhibited co-infection with multiple HR-HPV types, as shown in

Table 3. Co-infections were most frequent in Grade 1 tumours (19%), compared to Grade 3 (11%) and Grade 2 (7%). Although a direct association between co-infection and tumour grade was not observed, the presence of multiple HR-HPV types suggests potential synergistic interactions that may promote viral persistence or increase oncogenic potential, consistent with findings in other HPV-related cancers [

7,

8].

Specific genotype combinations observed in

Table 4, such as HPV16–HPV39, HPV35–HPV66, and HPV16–HPV33–HPV52, further highlight the diversity of co-infections in bladder cancer. These combinations could result in more aggressive oncogenic behaviour, as suggested in cervical cancer literature, although this hypothesis remains to be validated in bladder cancer models [

9].

Although DNA-based detection methods confirm the presence of HPV genetic material, they do not differentiate between latent, cleared, or transcriptionally active infections [

10,

21]. Therefore, this study also assessed the expression of HPV E7 oncoprotein via immunohistochemistry in all HR-HPV-positive samples. Thirteen out of 16 (81%) samples showed E7 expression, confirming active viral gene expression in the majority of cases. Conversely, three HPV DNA-positive samples were negative for E7 expression, possibly due to early-stage infection or immune-mediated clearance, consistent with the “hit-and-run” hypothesis of HPV-related oncogenesis [

23].

The variability in E7 staining intensity across samples (

Figure 3) may reflect differences in viral load, gene integration status, or host immune responses. Interestingly, some co-infected samples lacked E7 expression, suggesting that not all HR-HPV presence translates into oncogenic activity, which aligns with observations in HPV-mediated oropharyngeal and breast cancers [

14,

23].

Demographic data from this cohort showed that 85% of the bladder cancer patients were male, and the majority were over 60 years of age, matching national and international bladder cancer trends [

2,

22]. These findings reinforce the representativeness of our sample for the UK bladder cancer population and highlight the need for gender- and age-specific analyses in future studies.

This investigation also has public health implications. The detection of HR-HPV types such as HPV35, HPV52, and HPV66—not currently covered by first-generation HPV vaccines—raises important questions about the scope of current vaccination strategies [

24]. If further studies confirm a pathogenic role of these types in bladder cancer, broader or regionally tailored vaccines may be necessary. Moreover, increasing awareness of HPV’s role beyond cervical cancer could improve early detection, prevention, and patient outcomes.

Nevertheless, this is the first UK-based study to investigate the prevalence and expression of 12 HR-HPV genotypes in fresh bladder cancer tissue. The results contribute to a growing body of evidence suggesting that HPV may be involved in bladder carcinogenesis, at least in a subset of cases. These findings suggest the need for further mechanistic studies and larger epidemiological analyses across different populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H.A; methodology, Y.A.; software, Y.A; validation, G.H.A, Y.A. and M.O.C..; formal analysis, Y.A.; investigation, G.H.A, Y.A.; resources, S.S.; data curation, Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.; writing—review and editing, Y.A, G.H.A,S.S and M.O.C.; visualization, Y.A.; supervision, G.H.A.; project administration, G.H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and officially approved by the Ethics Committee of Health and Research Authority NHS (NRES Committee East Midlands – Leicester Central, UK) REC reference: 17/EM/0393. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the patients who donated tissue and assistance of the surgical team at Kingston Hospital (Kingston upon Thames, London, UK). Also, authors would like to acknowledge Kingston University London for providing laboratory facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Research UK. Bladder cancer statistics. [Online]. Cancer Research UK. 2022. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bla (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Abdollahzadeh, P.; Madani, S.H.; Khazaei, S.; Sajadimajd, S.; Izadi, B.; Najafi, F. Association between human Papillomavirus and transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urology journal 2017, 14, 5047–50504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, M.A.; Gordon, N.S.; Abbotts, B.; James, N.D.; Zeegers, M.P.; Cheng, K.K.; Macdonald, A.; Roberts, S.; Parish, J.L.; Ward, D.G.; Bryan, R.T. Defining the frequency of human papillomavirus and polyomavirus infection in urothelial bladder tumours. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 11290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Reuter, V.E.; Hansel, D.E. Non-urothelial carcinomas of the bladder. Histopathology 2019, 74, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymonowicz, K.A.; Chen, J. Biological and clinical aspects of HPV-related cancers. Cancer biology & medicine 2020, 17, 864. [Google Scholar]

- Manini, I.; Montomoli, E. Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Ann Ig 2018, 30, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M. Immune responses to human papillomavirus and the development of human papillomavirus vaccines. In Human Papillomavirus; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 283–297. [Google Scholar]

- Hatano, T.; Sano, D.; Takahashi, H.; Oridate, N. Pathogenic role of immune evasion and integration of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, G.H.; Salman, N.A. Pathogenesis of Human Papillomavirus–Immunological Responses to HPV Infection. In Human Papillomavirus-Research in a Global Perspective; Rajkumar, R., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016; pp. 243–253. ISBN 978-953-51-2439-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe, M.; Taguchi, A.; Sone, K.; Mori, M.; Osuga, Y. Carcinogenesis and management of human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 28, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.Y.; Salman, N.A.; Sandhu, S.; Cakir, M.O.; Seddon, A.M.; Kuehne, C.; Ashrafi, G.H. Detection of high-risk Human Papillomavirus in prostate cancer from a UK based population. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, N.A.; Davies, G.; Majidy, F.; Shakir, F.; Akinrinade, H.; Perumal, D.; Ashrafi, G.H. Association of High Risk Human Papillomavirus and Breast cancer: A UK based Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, T.; Dai, M. Human papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2011, 204, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.C.; Thümer, L.; Schuster, T.; Horn, T.; Kurtz, F.; Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Seebach, J.; Straub, M.; Maurer, T.; Autenrieth, M.; Kübler, H. Human papilloma virus is not detectable in samples of urothelial bladder cancer in a central European population: a prospective translational study. Infectious Agents and Cancer 2015, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan, B.B.; Ürün, Y. Unveiling the Role of Human Papillomavirus in Urogenital Carcinogenesis a Comprehensive Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, T.R.L.; Mellon, J.K. Human papillomavirus and urological tumours: II. Role in bladder, prostate, renal and testicular cancer. BJU international 2000, 85, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K.R.; Jensen, J.B. Human papillomavirus and urinary bladder cancer revisited. Apmis 2020, 128, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, C.; Ma, X.; Zhou, X.; Tian, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, L.; Li, R.; Chen, H. Human papillomavirus prevalence and integration status in tissue samples of bladder cancer in the chinese population. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 224, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.H.; Halder, A.; Purwar, S.; Pushpalatha, K.; Gupta, P.; Dubey, P. Study to determine efficacy of urinary HPV 16 & HPV 18 detection in predicting premalignant and malignant lesions of uterine cervix. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of bladder cancer. Medical sciences 2020, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.A.; Idris, A.; McMillan, N.A. Analysis of a hit-and-run tumor model by HPV in oropharyngeal cancers. Journal of Medical Virology 2023, 95, e28260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, A.; Bowden, S.; et al. HPV vaccination and cancer prevention. Best Prac. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 65, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

A representative gel electrophoresis pattern of 12 high risk HPV types by genotype specific primers amplification. (A) Gel electrophoresis pattern of high-risk HPV types (52, 56, 58 and 66), Loading Marker = DNA ladder 100 bp plus (100 bp-3000 bp), HPV 52/66 = Positive Control DNA HPV types, 52 (360 bp), 56 (325 bp) and 58 (240 bp), 66 (304 bp) respectively, ID 71 and 78 = HPV Negative clinical sample, ID 72. 77 and 80 = HPV Positive clinical sample, Positive Control (PC+ ) = Internal control; human DNA (β -globin 723 bp). (B) Gel electrophoresis pattern of high-risk HPV types (18, 39, 45 and 59), HPV 18/59 = Positive Control DNA, HPV types 18 (425 bp), 39 (340 bp), 45 (340 bp) and 59 (395 bp) respectively, ID 134, 135, 137 and 138 = HPV Negative clinical sample, ID 136 = HPV Positive clinical sample.

Figure 1.

A representative gel electrophoresis pattern of 12 high risk HPV types by genotype specific primers amplification. (A) Gel electrophoresis pattern of high-risk HPV types (52, 56, 58 and 66), Loading Marker = DNA ladder 100 bp plus (100 bp-3000 bp), HPV 52/66 = Positive Control DNA HPV types, 52 (360 bp), 56 (325 bp) and 58 (240 bp), 66 (304 bp) respectively, ID 71 and 78 = HPV Negative clinical sample, ID 72. 77 and 80 = HPV Positive clinical sample, Positive Control (PC+ ) = Internal control; human DNA (β -globin 723 bp). (B) Gel electrophoresis pattern of high-risk HPV types (18, 39, 45 and 59), HPV 18/59 = Positive Control DNA, HPV types 18 (425 bp), 39 (340 bp), 45 (340 bp) and 59 (395 bp) respectively, ID 134, 135, 137 and 138 = HPV Negative clinical sample, ID 136 = HPV Positive clinical sample.

Figure 2.

Sanger sequencing analysis further valdates and confirms the PCR results. A representative Sanger sequencing result (Sample ID 50) shows 90% concordance for HPV35. This applies to all PCR results.

Figure 2.

Sanger sequencing analysis further valdates and confirms the PCR results. A representative Sanger sequencing result (Sample ID 50) shows 90% concordance for HPV35. This applies to all PCR results.

Figure 3.

Expression of HPV oncoprotein E7 analysed using Immunohistochemistry. (A) Representative of Bladder cancer with HPV showing negative HPV expression. (B) Representative of HPV positive bladder cancer sample with slightly positive HPV expression. (C, D) Representative of HPV infected bladder cancer sample with moderate and absolute HPV expression, respectively.

Figure 3.

Expression of HPV oncoprotein E7 analysed using Immunohistochemistry. (A) Representative of Bladder cancer with HPV showing negative HPV expression. (B) Representative of HPV positive bladder cancer sample with slightly positive HPV expression. (C, D) Representative of HPV infected bladder cancer sample with moderate and absolute HPV expression, respectively.

Table 1.

The histopathological results of patients with suspected bladder cancer at Kingston hospital. Based on these histopathological results, the most diagnosed bladder cancer cases were transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) cases and squamous cell carcinoma was found to be the rarest cancer type.

Table 1.

The histopathological results of patients with suspected bladder cancer at Kingston hospital. Based on these histopathological results, the most diagnosed bladder cancer cases were transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) cases and squamous cell carcinoma was found to be the rarest cancer type.

| |

Total Samples N (%) |

| Total number of samples |

55 (100) |

Female

Male |

8/55 (14.5)

47/55 (85.5)

|

Age (Year)

(45 – 96) |

|

<60

61-70

71-80

81-90

>90 |

6/55 (10.9)

10/55 (18.2)

18/55 (32.7)

16/55 (29.1)

5/55 (9.1)

|

| Pathological status |

|

Squamous cell carcinoma

Transitional cell carcinoma

No cancer |

2/55 (3.6)

49/55 (89.1)

4/55 (7.3)

|

Table 2.

Prevalence of 12 HR-HPV Types in Bladder Samples. The table demonstrates the prevalence of each of the 12 HR-HPV types in TCC of the bladder. Most prevalent HPV types in cancerous cases were HPV16, 35 and 52 with 5 samples infected.

Table 2.

Prevalence of 12 HR-HPV Types in Bladder Samples. The table demonstrates the prevalence of each of the 12 HR-HPV types in TCC of the bladder. Most prevalent HPV types in cancerous cases were HPV16, 35 and 52 with 5 samples infected.

| Pathological Status |

HPV Genotypes |

HPV in TCC n=17

17/49 (35%)

|

16 |

31 |

33 |

35 |

18 |

39 |

45 |

59 |

52 |

56 |

58 |

66 |

| Grade 1 |

2/5 (40) |

- |

1/1 (100) |

2/5 (40) |

- |

- |

1/4 (25) |

- |

4/5 (80) |

- |

- |

2/2 (100) |

| Grade 2 |

- |

- |

- |

1/5 (20) |

- |

- |

1/4 (25) |

1/2 (50) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Grade 3 |

3/5 (60) |

- |

- |

2/5 (40) |

- |

1/1 (100) |

2/4 (50) |

1/2 (50) |

1/5 (20) |

- |

- |

- |

| Total Prevalence of Specific HPV Genotype Cases n= |

5 |

- |

1 |

5 |

- |

1 |

4 |

2 |

5 |

- |

- |

2 |

Table 3.

The frequency of HR-HPV infection with multiple HPV genotypes in bladder samples.

Table 3.

The frequency of HR-HPV infection with multiple HPV genotypes in bladder samples.

| Pathological Status |

Total number of cases |

Total HPV +

N (%) |

HPV co-infections

N (%) |

|

| TRANSITIONAL CELL CARCINOMA CASES |

49/49 (100) |

17/49 (34.7) |

6/49 (12.2) |

|

| Grade 1 |

16 |

8/16 (50) |

3/16 (19) |

|

| Grade 2 |

14 |

2/14 (14) |

1/14 (7) |

|

| Grade 3 |

19 |

7/19 (37) |

2/19 (11) |

|

| Total |

49 |

17 |

6 |

|

Table 4.

HPV co-infection combination types in prostate tissues.

Table 4.

HPV co-infection combination types in prostate tissues.

| HPV Co-infection pairing |

Frequency |

| HPV16-HPV39 |

1 |

| HPV35-HPV66 |

1 |

| HPV52-HPV66 |

1 |

| HPV45-HPV59 |

1 |

| HPV16-HPV33-HPV52 |

1 |

| HPV35-HPV45-HPV59 |

1 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).