Submitted:

14 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Clay/Gum Arabic Nanocomposite

2.2. Batch Adsorption Experiments

2.3. Kinetic studies

2.4. Adsorption Isotherm Models

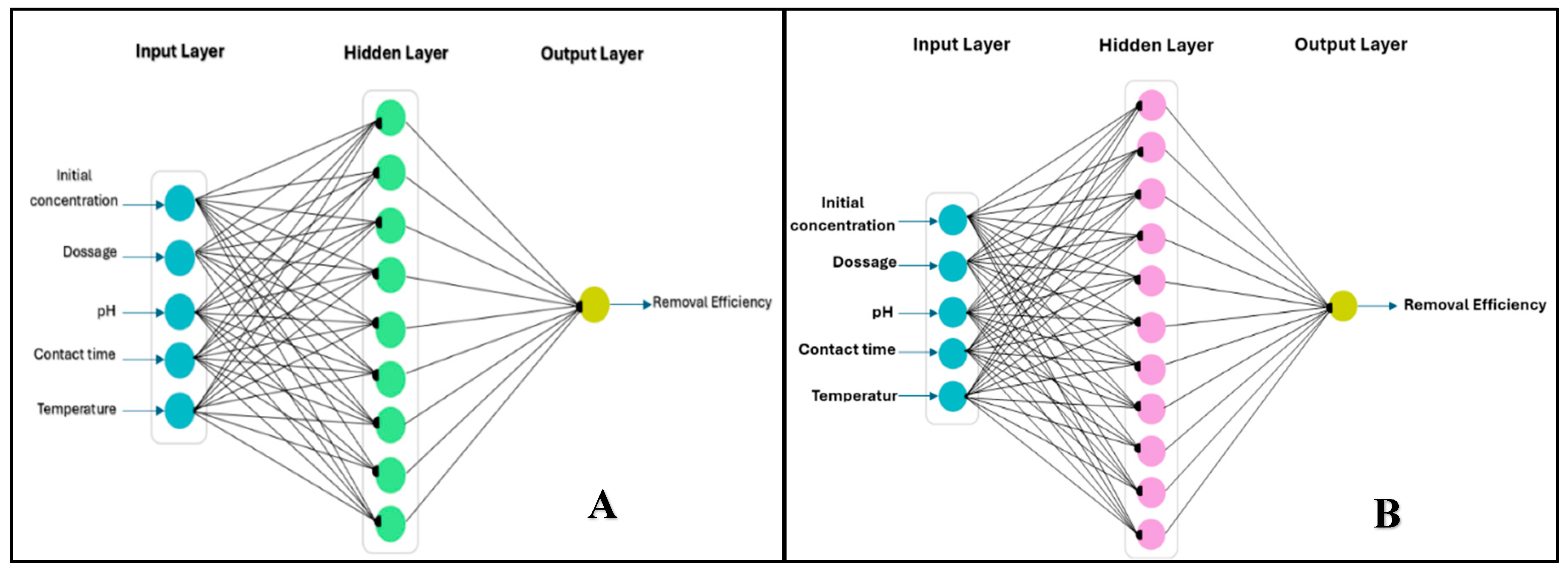

2.5. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

2.6. Reusability of CG/NC

2.7. Zeta Potential (ZP)

2.8. Instrumentation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

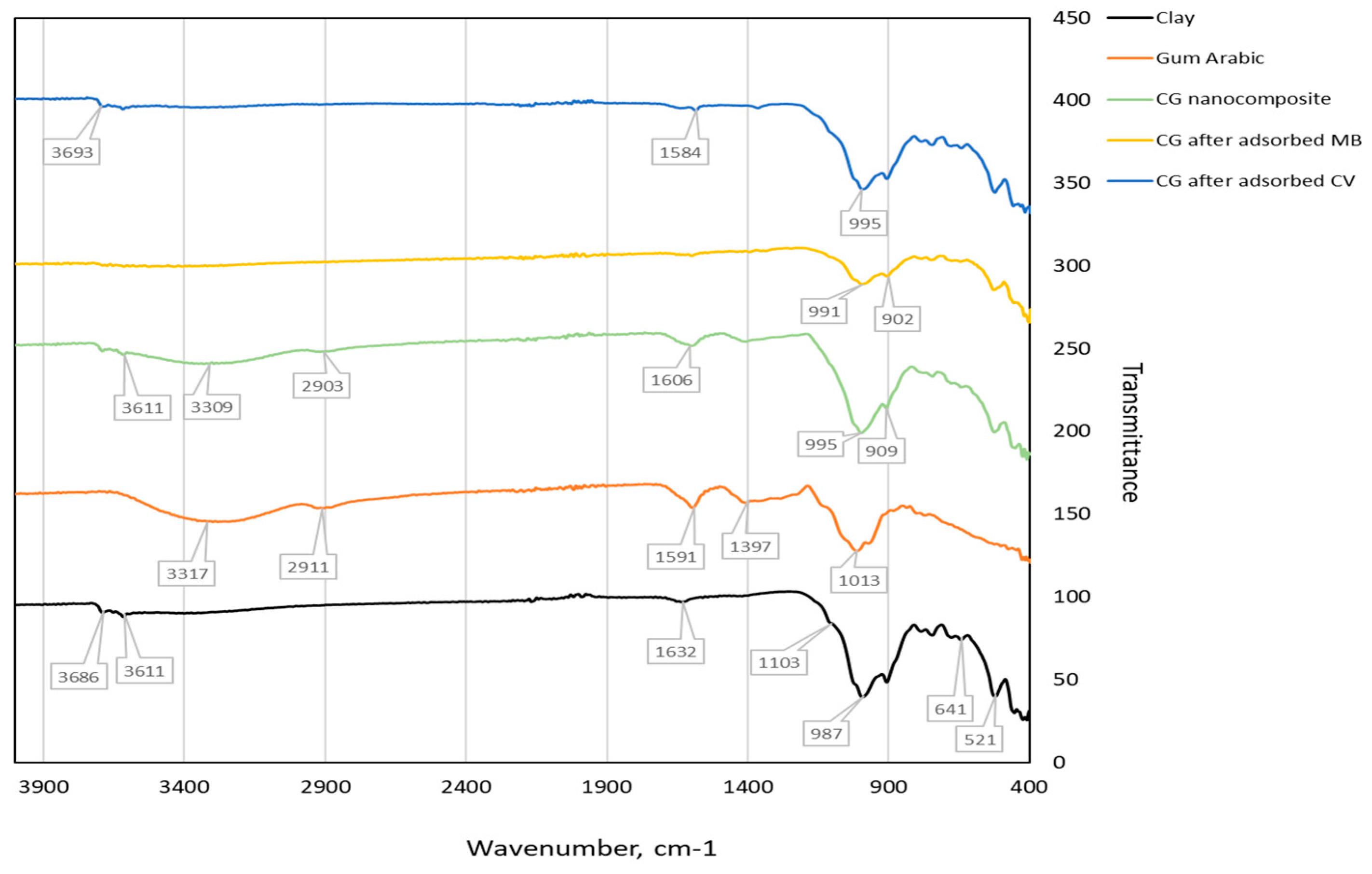

3.1.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

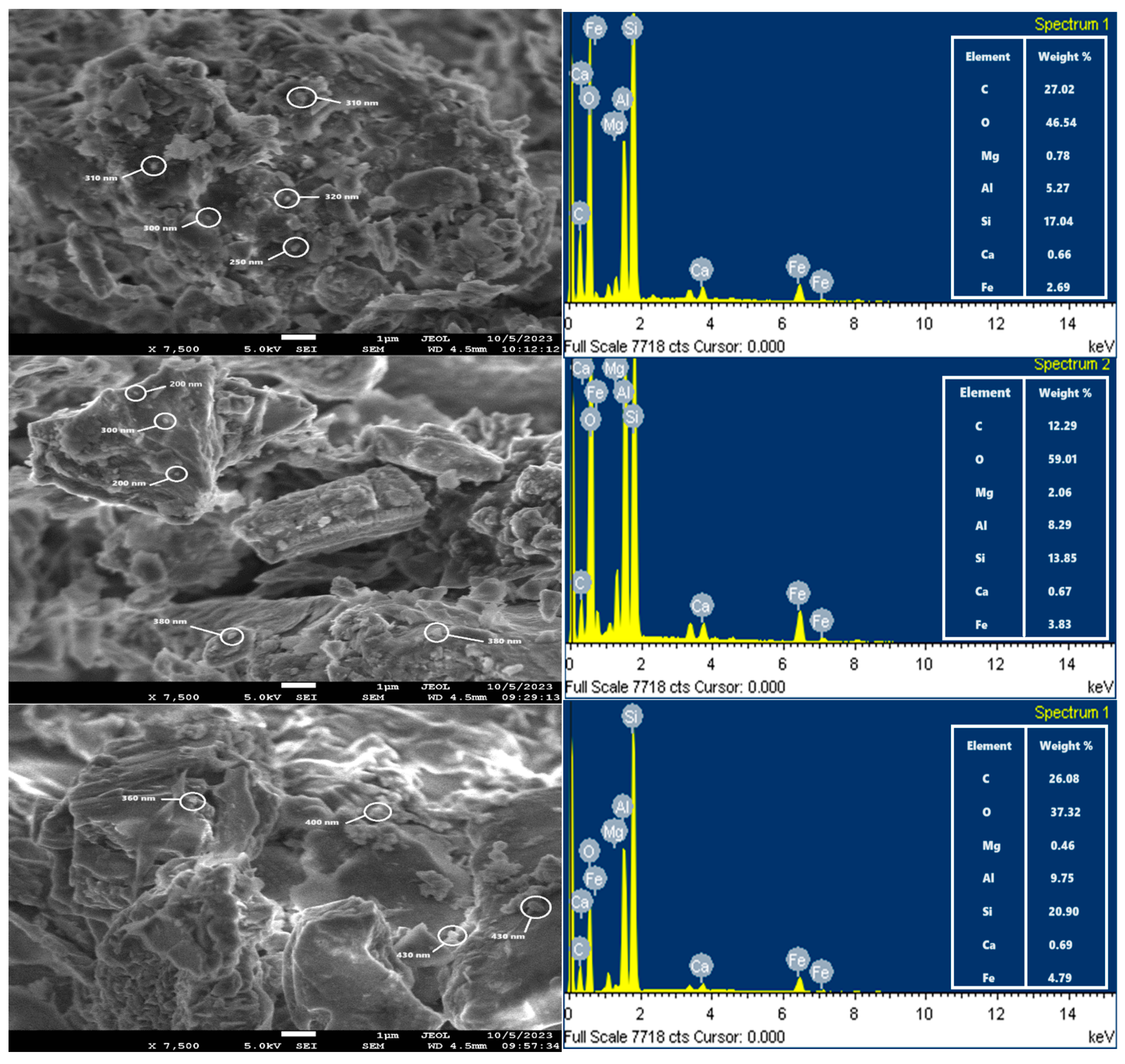

3.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM-EDX)

3.1.3. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Analysis

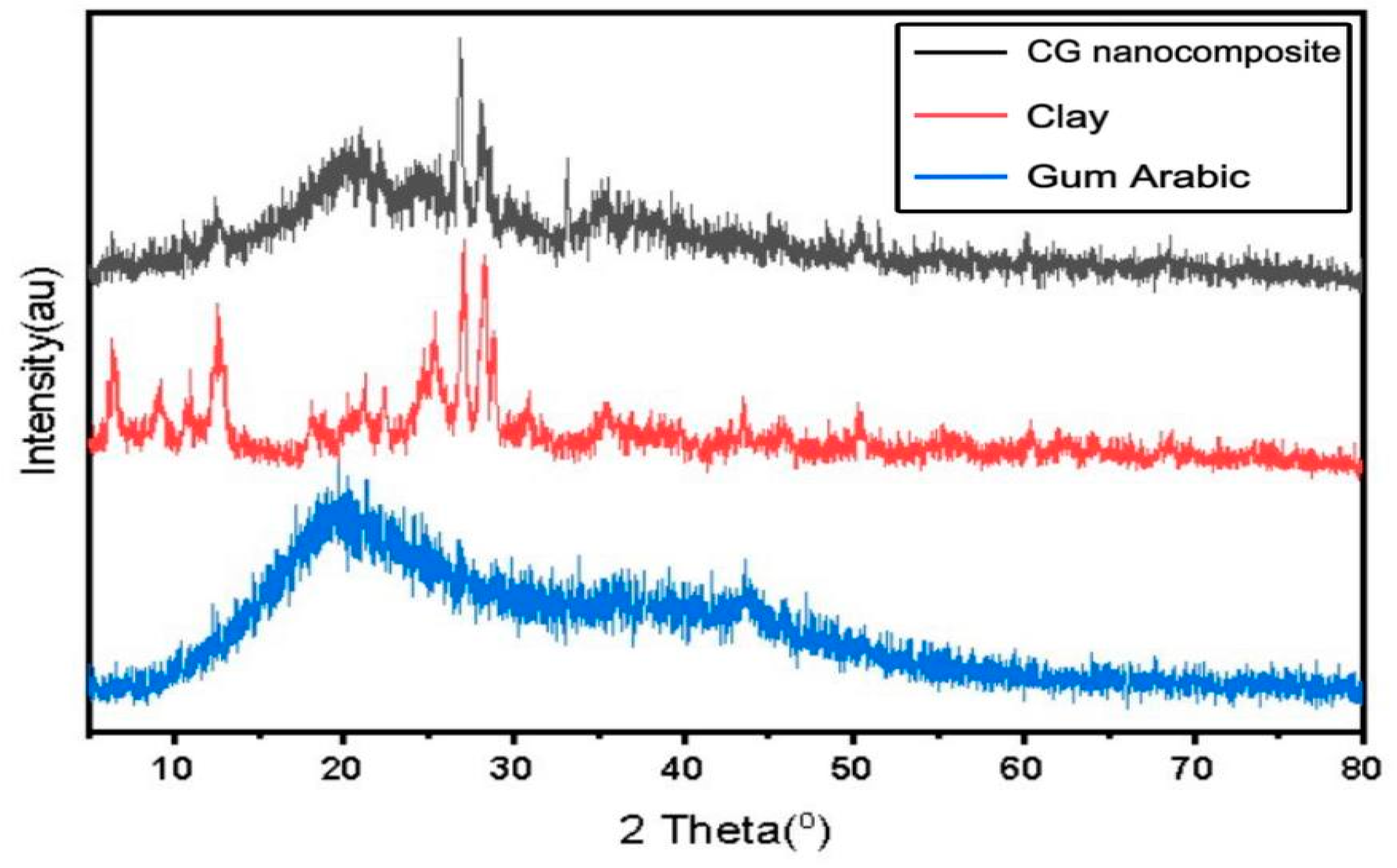

3.1.4. X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRD)

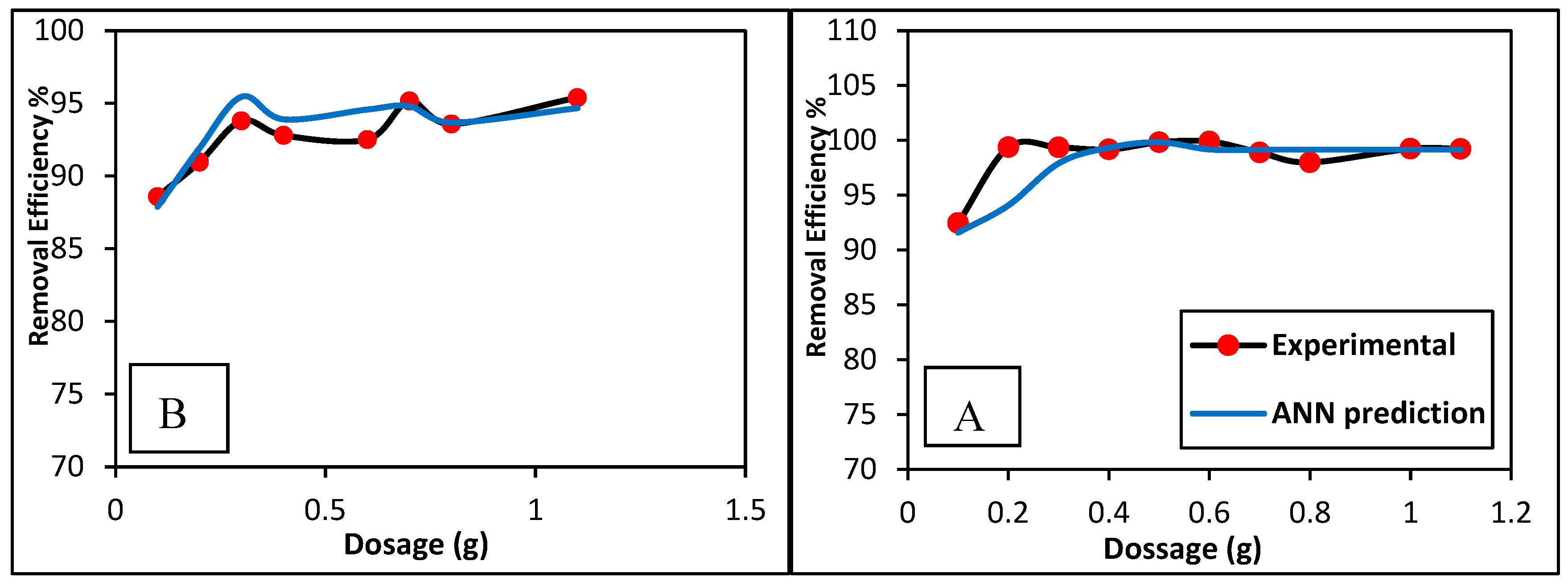

3.2. Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

3.3. Adsorption Studies

3.3.1. Effect of Dosage of CG/MC

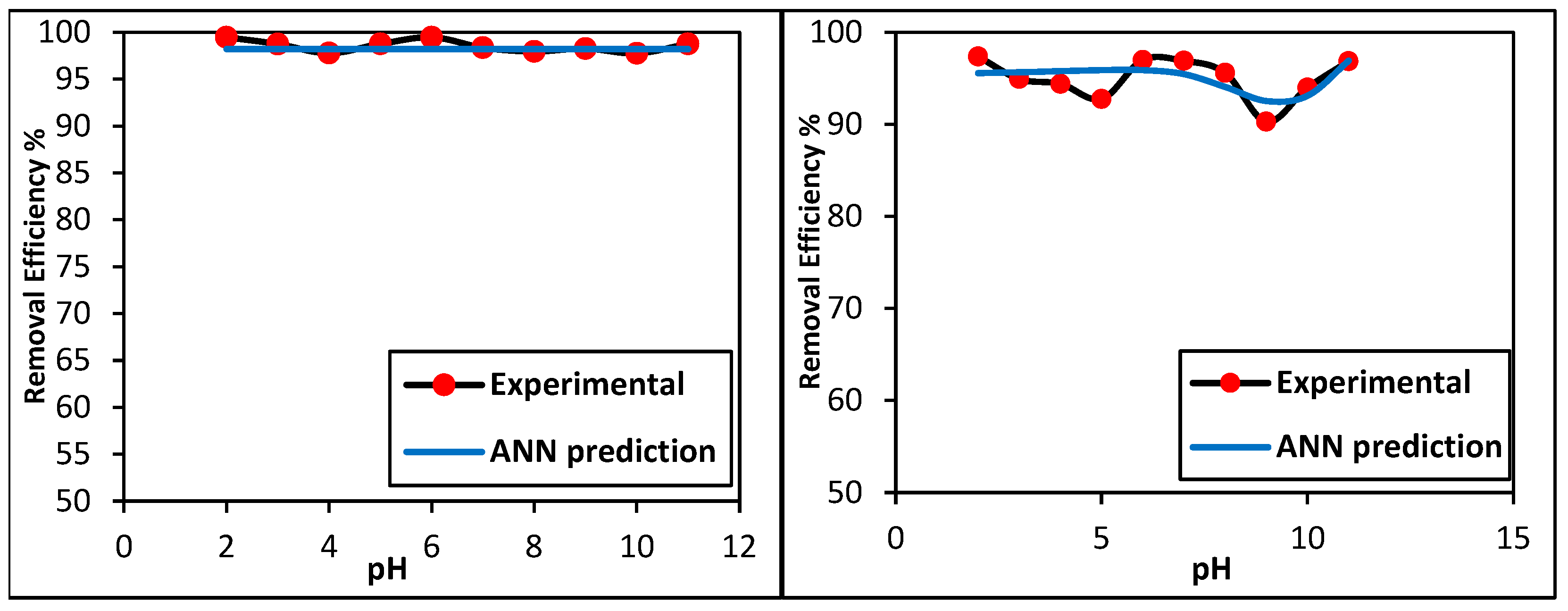

3.3.2. Effect of pH

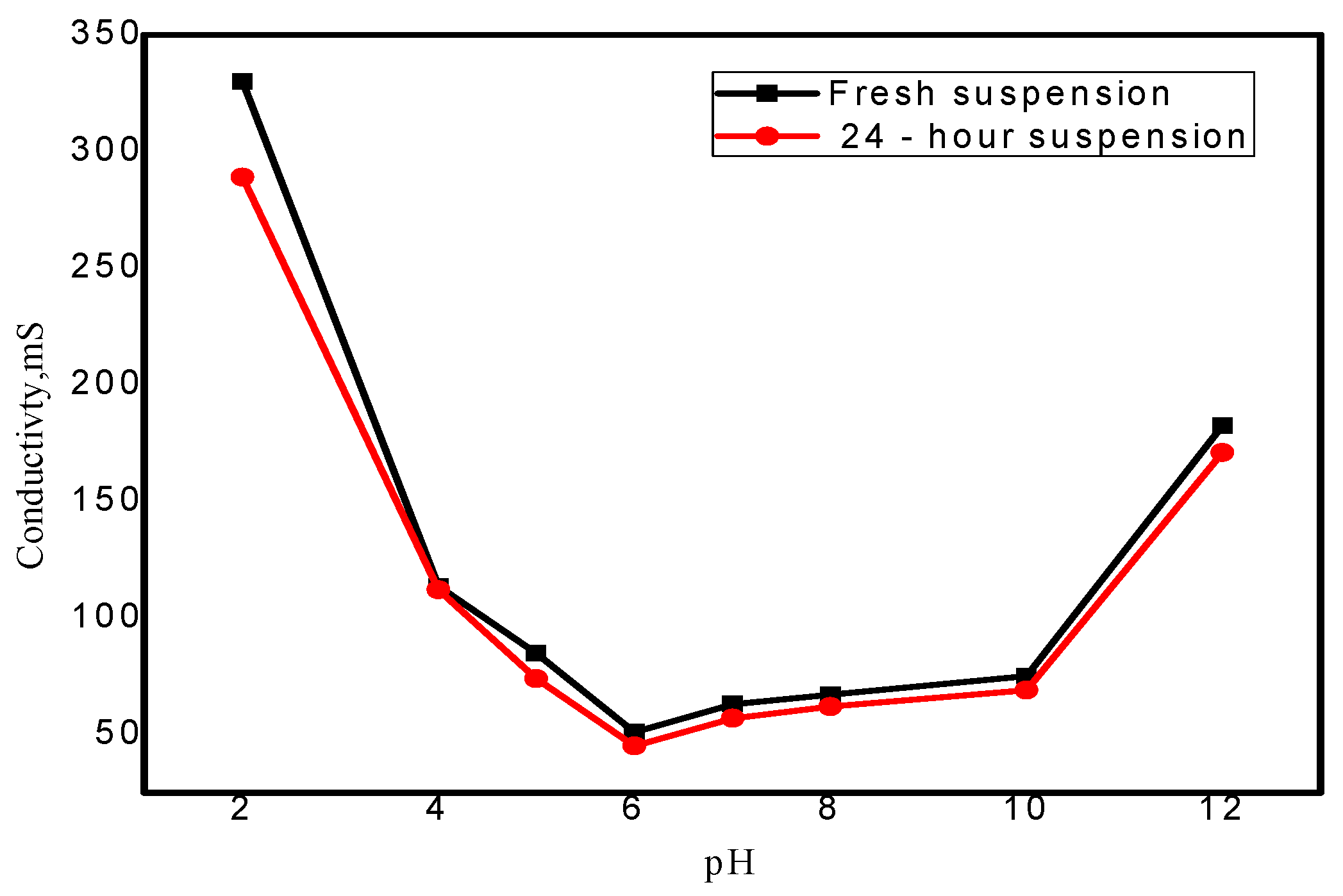

3.3.3. Zeta Potential

3.3.4. Effect of Contact Time

3.3.5. Effect of Initial Concentration

3.3.6. Effect of Temperature

3.3.7. Optimizing the ANN Model

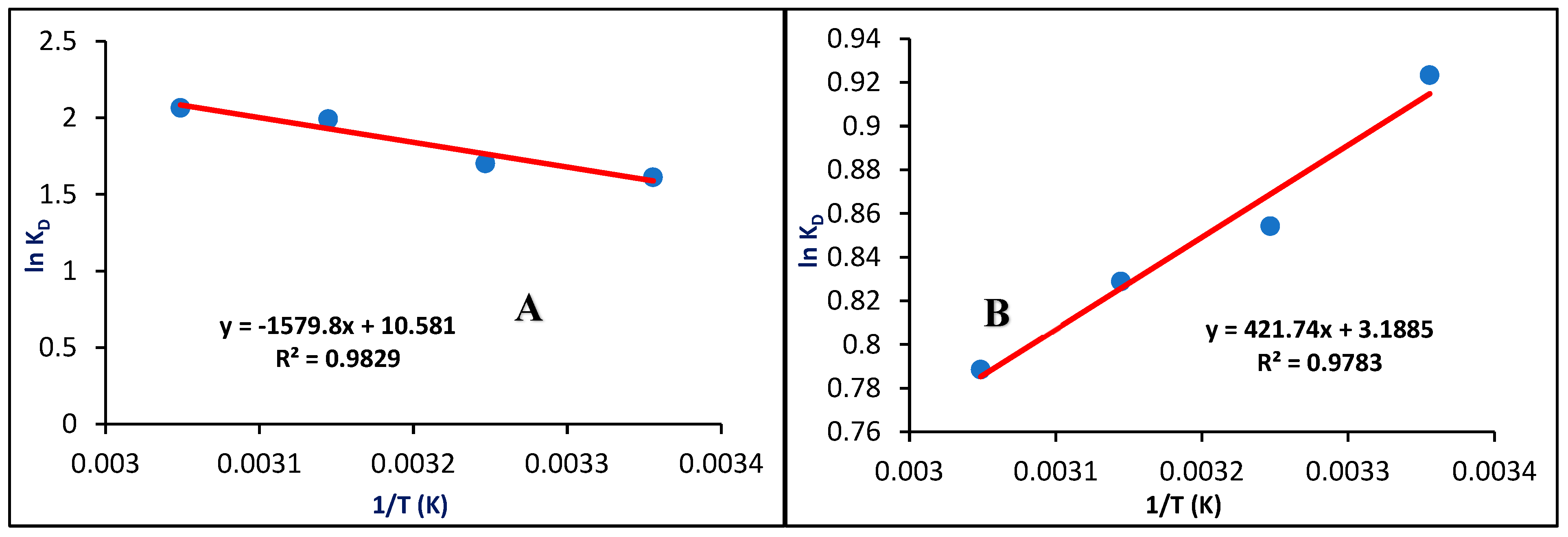

3.3.7. Thermodynamic Factors

3.3.8. Adsorption Isotherm Models

Langmuir Isotherm Model

3.4.2. Freundlich Isotherm Model

3.4.3. Temkin Isotherm Model

3.5. Kinetic studies

3.5.1. The Pseudo-First-Order

3.5.2. The Pseudo-Second-Order

The Intra-Particle Diffusion Model

The Elovich Model

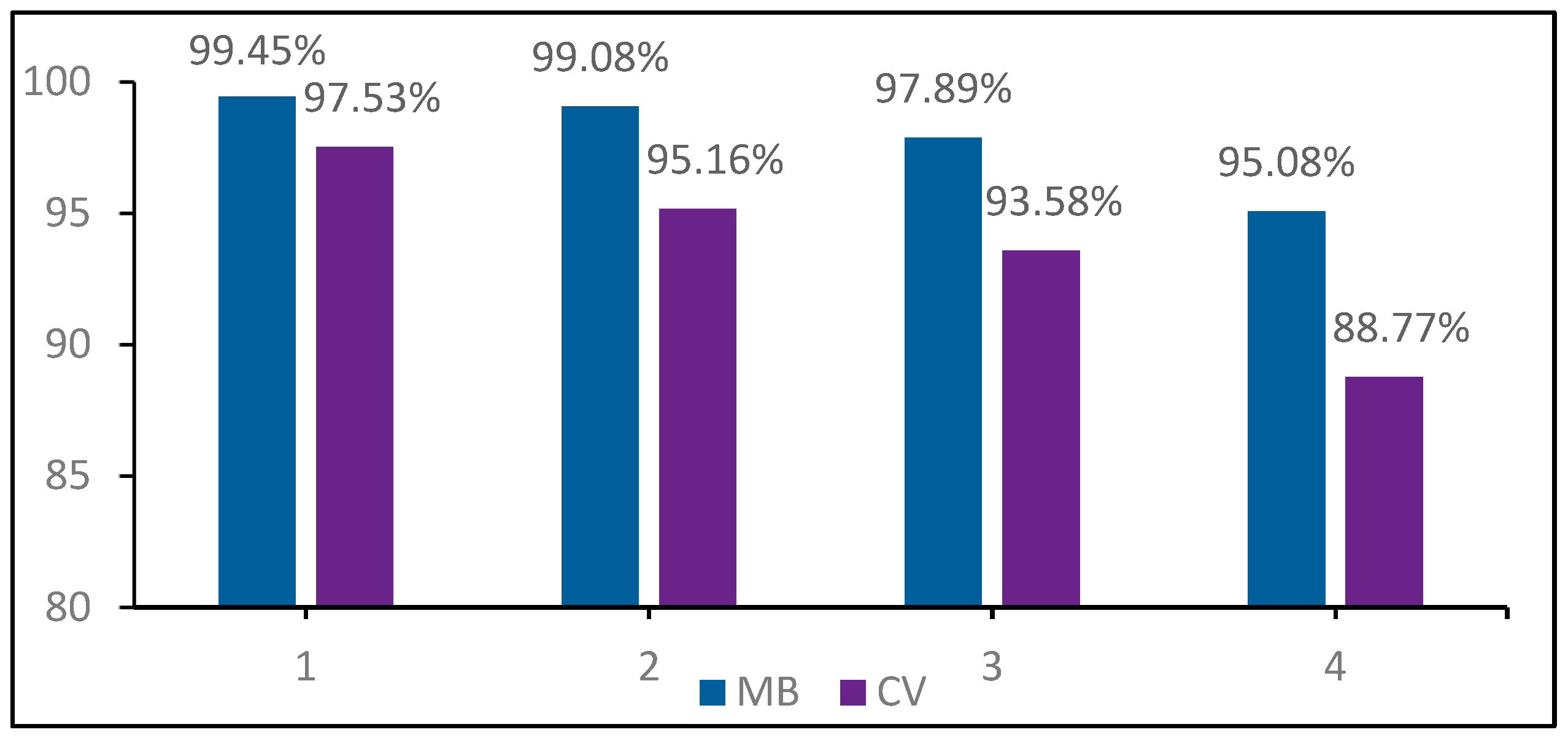

5.3.6. Reusability of CG/NC

5.3.7. Comparison with Other Adsorbents

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaramillo-Fierro, X.; González, S.; Jaramillo, H.A.; Medina, F. Synthesis of the ZnTiO3/TiO2 Nanocomposite Supported in Ecuadorian Clays for the Adsorption and Photocatalytic Removal of Methylene Blue Dye. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1891. [CrossRef]

- Ibupoto, A.S., Qureshi, U.A.; Ahmed, F.; Khatri, Z.; Khatri, M.; Maqsood, M.; Brohi., R.Z. Reusable carbon nanofibers for efficient removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution. Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 2018, 136, 744-752.

- Hameed, B.; Din, A.M.; Ahmad, A. Adsorption of methylene blue onto bamboo-based activated carbon: kinetics and equilibrium studies. Journal of hazardous materials 2007.,141(3), 819-825.

- Hong, J.; Bao, J.; Liu, Y. Removal of Methylene Blue from Simulated Wastewater Based upon Hydrothermal Carbon Activated by Phosphoric Acid. Water 2025, 17, 733. [CrossRef]

- Vishal Singh, Rahul Sapehia, Vikas Dhiman, Removal of methylene blue dye by green synthesized NiO/ZnO nanocomposites. Inorganic Chemistry Communications, 2025, 162, 112267, . [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Y.; Aydın, H. A kinetics and thermodynamics study of methylene blue adsorption on wheat shells. Desalination 2006. 194, 259-267.

- Hoslett, J., Ghazal, H.; Mohamad, N.; Jouhara, H. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions by biochar prepared from the pyrolysis of mixed municipal discarded material. Science of the Total Environment 2020. 714, 136832.

- Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X.; Bai, Z.; Yu, Z. Preparation of β-cyclodextrin/graphene oxide and its adsorption properties for methylene blue. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 200, 111605.

- Rehman, M.U. Physicochemical characterization of Pakistani clay for adsorption of methylene blue: Kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic study. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2021, 269, 124722.

- Patil, M.R.; Shrivastava, V. Adsorptive removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution by polyaniline-nickel ferrite nanocomposite: a kinetic approach. Desalination and Water Treatment. 2016, 57(13), 5879-5887.

- Chang, J.; Adsorption of methylene blue onto Fe3O4/activated montmorillonite nanocomposite. Applied Clay Science 2016, 119, 132-140.

- Alzahrani, E.; Gum Arabic-coated magnetic nanoparticles for methylene blue removal. International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering Technology 2014, 3(8), 15118-15129.

- Azhar-ul-Haq, M. Adsorptive removal of hazardous crystal violet dye onto banana peel powder: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology 2022, 1-16.

- Chowdhury, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Das, P. Adsorption of crystal violet from aqueous solution by citric acid modified rice straw: equilibrium, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Separation Science and Technology 2013, 48(9), 1339-1348.

- Sulthana, R.; Taqui, S.N.; Syed, U.T. Adsorption of crystal violet dye from aqueous solution using industrial pepper seed spent: equilibrium, thermodynamic, and kinetic studies. Adsorption Science and Technology 2022. doi:10.1155/2022/9009214.

- Khattri, S.; Singh, M. Use of Sagaun sawdust as an adsorbent for the removal of crystal violet dye from simulated wastewater. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 2012, 31(3), 435-442.

- Loulidi, I.; Boukhlifi, F.; Ouchabi, M.; Amar, A. Adsorption of crystal violet onto an agricultural waste residue: kinetics, isotherm, thermodynamics, and mechanism of adsorption. The Scientific World Journal, 2020, 5873521, . [CrossRef]

- AL-Shehri, H.S.; Almudaifer, E.; Alorabi, A.Q.; Alanazi, H.S.; Alkorbi, A.S.; Alharthi, F.A. Effective adsorption of crystal violet from aqueous solutions with effective adsorbent: equilibrium, mechanism studies and modeling analysis. Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability 2021, 33, 214-226.

- Senthilkumaar, S.; Kalaamani, P.; Subburaam, C. Liquid phase adsorption of crystal violet onto activated carbons derived from male flowers of coconut tree. Journal of hazardous materials 2006, 136, 800-808.

- Ahmad, R.; Studies on adsorption of crystal violet dye from aqueous solution onto coniferous pinus bark powder (CPBP). Journal of hazardous materials 2009, 171, 767-773.

- Laskar, N.; Kumar, U. Adsorption of crystal violet from wastewater by modified bambusa tulda. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2018, 22, 2755-2763.

- Mulla, B.; Ioannou, K.; Kotanidis, G.; Ioannidis, I.; Constantinides, G.; Baker, M.; Hinder, S.; Mitterer, C.; Pashalidis, I.; Kostoglou, N.; et al. Removal of Crystal Violet Dye from Aqueous Solutions through Adsorption onto Activated Carbon Fabrics. C 2024, 10, 19. [CrossRef]

- Ben Tahar, L.; Mogharbel, R.; Hameed, Y.; Noubigh, A.; Abualreish, M.J.A.; Alanazi, A.H.; Hatshan, M.R. Enhanced removal of the crystal violet dye from aqueous medium using tripolyphosphate–functionalized Zn–substituted magnetite nanoparticles. Results in Chemistry 2025, 14, 102152.

- Khan, M.I.; Almesfer, M.K.; Elkhaleefa, A.M.; et al. Efficient adsorption of hexavalent chromium ions onto novel ferrochrome slag/polyaniline nanocomposite: ANN modeling, isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022. 29, 86665-86679. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E.; Moghaddam, M.R.A.; Kowsari, E. A systematic and critical review on development of machine learning based-ensemble models for prediction of adsorption process efficiency. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 134588.

- Çelekli, A.; Geyik, F.; Artificial neural networks (ANN) approach for modeling of removal of Lanaset Red G on Chara contraria. Bioresource technology 2011, 102(10), 5634-5638.

- Khonde, R.; Pandharipande, S., Artificial Neural Network modeling for adsorption of dyes from aqueous solution using rice husk carbon. International Journal of Computer Applications 2012. 41(4).

- Sharma, K.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, V.; Mishra, P.K.; Ekielski, A.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, V. Methylene Blue Dye Adsorption from Wastewater Using Hydroxyapatite/Gold Nanocomposite: Kinetic and Thermodynamics Studies. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1403. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Yahya, S.A.; ElKhaleefa, A.; Shigidi, I.; Ali, I.H.; Rehan, M.; Pirzada, A.M. Toxic Anionic Azo Dye Removal from Artificial Wastewater by Using Polyaniline/Clay Nanocomposite Adsorbent: Isotherm, Kinetics and Thermodynamic Study. Processes 2025, 13, 827. [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.H.; Bani-Fwaz, M.Z.; El-Zahhar, A.A.; Marzouki, R.; Jemmali, M.; Ebraheem, S.M. Gum Arabic-Magnetite Nanocomposite as an Eco-Friendly Adsorbent for Removal of Lead(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Separations 2021, 8, 224. [CrossRef]

- Elkhaleefa, A.; Ali, I.H.; Brima, E.I.; Shigidi, I.; Elhag, A.B.; Karama, B. Evaluation of the Adsorption Efficiency on the Removal of Lead(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions Using Azadirachta indica Leaves as an Adsorbent. Processes 2021, 9, 559. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Demirci, Ş.; Özbayoğlu, G. Zeta potential measurements on three clays from Turkey and effects of clays on coal flotation. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 1996, 184(2), 535-541.

- Shehu, Z.; Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Kaolin/Gum Arabic Nanocomposite on Escherichia Coli and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Research Journal of Nanoscience and Engineering 2018. 2(2), 23-29.

- Idrissi, M.; Degradation of crystal violet by heterogeneous Fenton-like reaction using Fe/Clay catalyst with H2O2. Journal of Materials and Environmental Science 2016. 7(1), 50-58.

- Adikary, S.; Wanasinghe, D.; Characterization of locally available Montmorillonite clay using FTIR technique. Annual Transactions of Institution of Engineers Sri Lanka 2012, 1, 140-145.

- Upadhyay, A.; Ethylene scavenging film based on corn starch-gum acacia impregnated with sepiolite clay and its effect on quality of fresh broccoli florets. Food Bioscience 2022, 46, 101556.

- Nayak, A.K.; Das, B.; Maji, R.; Calcium alginate/gum Arabic beads containing glibenclamide: Development and in vitro characterization. International journal of biological macromolecules 2012, 51(5), 1070-1078.

- Jawad, A.H.; Abdulhameed, A.S. Mesoporous Iraqi red kaolin clay as an efficient adsorbent for methylene blue dye: adsorption kinetic, isotherm and mechanism study. Surfaces and Interfaces 2020, 18, 100422.

- Mukherjee, K.; Adsorption enhancement of methylene blue dye at kaolinite clay–water interface influenced by electrolyte solutions. RSC Advances 2015, 5(39), 30654-30659.

- Alorabi, A.Q.; Hassan, M.S.; Alam, M.M.; Zabin, S.A.; Alsenani, N.I.; Baghdadi, N.E. Natural Clay as a Low-Cost Adsorbent for Crystal Violet Dye Removal and Antimicrobial Activity. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2789. [CrossRef]

- Amirabadi, S.; Milani, J.M.; Sohbatzadeh, F. Application of dielectric barrier discharge plasma to hydrophobically modification of gum arabic with enhanced surface properties. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 104, 105724.

- Mecheri, R.; Zobeidi, A.; Atia, S.; Neghmouche Nacer, S.; Salih, A.A.M.; Benaissa, M.; Ghernaout, D.; Arni, S.A.; Ghareba, S.; Elboughdiri, N. Modeling and Optimizing the Crystal Violet Dye Adsorption on Kaolinite Mixed with Cellulose Waste Red Bean Peels: Insights into the Kinetic, Isothermal, Thermodynamic, and Mechanistic Study. Materials 2023, 16, 4082. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.; Phase formation behaviour in alkali activation of clay mixtures. Applied Clay Science 2019. 175, 10-21.

- 1Bashir, M.; Haripriya, S. Assessment of physical and structural characteristics of almond gum. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2016, 93, 476-482.

- Emam, H.E.; Arabic gum as bio-synthesizer for Ag–Au bimetallic nanocomposite using seed-mediated growth technique and its biological efficacy. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 2019, 27, 210-223.

- Yadav, V.B.; Gadi, R.; Kalra, S. Synthesis and characterization of novel nanocomposite by using kaolinite and carbon nanotubes. Applied Clay Science 2018, 155, 30-36.

- Nasuha, N.; Hameed, B.H.; Din, A.T. Rejected tea as a potential low-cost adsorbent for the removal of methylene blue. J Hazard Mater 2010, 175, 126-32.

- Ali, R.; Elsagan, Z.; AbdElhafez, S.; Lignin from agro-industrial waste to an efficient magnetic adsorbent for hazardous crystal violet removal. Molecules 2022, 27(6), 1831. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shahrani, S.; Phenomena of removal of crystal violet from wastewater using Khulays natural bentonite. Journal of Chemistry 2020. [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, K.M.; El-Dali, A.; Alkarewi, A.A.; Ewlad-Ahmed, A.M.; Treban, A. Adsorption of crystal violet dye onto olive leaves powder: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Chemistry International 2021, 7, 79-89.

| Sample | Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (Ao) |

| Clay | 14.34 | 0.003551 | 39.87 |

| Gum Arabic | 0.3835 | 0.00008181 | 18.85 |

| CG/NC | 46.91 | 0.0111 | 19.08 |

| Initialconcentration (mg/L) | Dosage CG/NC (g) | pH | Contact time (min) |

Temperature (oC) |

R (%) predicted |

R (%) experimentally |

||||

| MB CV |

50.00 47.90 |

0.30 0.29 |

7.00 7.00 |

7.00 3.80 |

24.00 50.00 |

99.15 99.00 |

97.31 96.40 |

|||

| MB | |||

| T, K | ∆G° (kJ/mol) | ∆S° (J/mol) | ∆H° (kJ/mol) |

| 298 308 318 328 |

-3.991 -4.356 -5.266 -5.631 |

88.01 |

13.13 |

| CV | |||

| T, K | ∆G° (kJ/mol) | ∆S° (J/mol) | ∆H° (kJ/mol) |

| 298 308 318 328 |

-2.288 -2.187 -2.191 -2.150 |

26.51 |

-3.50 |

| Langmuir Isotherm | |||

| qmax (mg/g) | KL (L/g) | R2 | |

| MB CV |

66.7 52.9 |

0.159 0.298 |

0.991 0.981 |

| Freundlich Isotherm | |||

| n | Kf (mg/g)/(mg/L) | R2 | |

| MB CV |

1.89 2.76 |

10.1 16.5 |

0.975 0.880 |

| Temkin Isotherm | |||

| A(L/g) | B | R2 | |

| MB CV |

2.5 2.6 |

12.08 28.55 |

0.929 0.975 |

| Pseudo-first-order | |||||

| qe (mg/g) | k1 (min-1) | R2 | |||

| MB CV |

5.694 4.028 |

0.000137 0.00035 |

0.701 0.323 |

||

| Pseudo-second-order | |||||

| qe (mg/g) | k2 (mg/g.min) | R2 | |||

| MB CV |

5.694 4.028 |

1.1876 1.9537 |

0.997 0.999 |

||

| Intra-particle diffusion | |||||

| kid (mg/g.min) | I | R2 | |||

| MB CV |

6.228 4.111 |

39.725 12.827 |

0.671 0.511 |

||

| Elovich | |||||

| α | β | R2 | |||

| MB CV |

3.40 x 1029 3.16 x 106 |

10.98 5.89 |

0.704 0.849 |

||

| Adsorbent | Adsorbate | Isotherm model | Optimum pH | Kinetic model | enthalpy | qmax (mg/g) | Adsorbent mass (g) | Ref. |

| (RT) | MB | Langmuir | 6-7 | Second order | - | 147 | 0.50 | [47] |

| (Fe3O4/Mt) | MB | Langmuir | 7.37 | Second order | - | 106.38 | 0.5 | [11] |

| (IRKC) | MB | Langmuir- Freundlich | 8 | First order | - | 240.4 | 0.1 | [38] |

| PANI-NiFe2O4 | MB | Langmuir | 9 | Second order | - | 6.65 | 8 | [10] |

| (WHS) | MB | Langmuir | 7 | Second order | endothermic | 21.50 | 1 | [6] |

| (LCF) | CV | Langmuir- Freundlich | 7 | First order | exothermic | 34.12 | 0.25 | [48] |

| Khulays natural bentonite | CV | Langmuir- Freundlich | 5.3 | Second order | endothermic | 263 | 0.25 | [49] |

| (NAJL) | CV | Langmuir | 9 | First order | exothermic | 315.2 | 0.02 | [18] |

| (OLP) | CV | Langmuir | 7.5 | Second order | - | 181.1 | 0.1 | [50] |

| (AS) | CV | Langmuir | 6 | Second order | endothermic | 12.2 | 0.5 | [17] |

| CG/NC | MB | Langmuir | 7 | Second order | endothermic | 66.7 | 0.20 | this study |

| CG/NC | CV | Langmuir | 7 | Second order | exothermic | 52.9 | 0.30 | this study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the contennstructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).