1. Introduction

Preventing falls in older adults is a public health challenge that continues to attract research interest (Montero-Odasso & Camicioli, 2020). Fall is defined as an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level. Falls, trips, and slips can occur on one level or from a height (WHO, 2021). Significantly, older adults with cognitive impairment and dementia are five times more likely to be hospitalized than older adults without cognitive impairment (Myers et al., 1991). The literature suggests there is a strong relationship between executive function and falls; executive dysfunction doubles the risk for future falls and increases the risks of fall injury by 40% in older persons living in the community (Muir, Gopaul & Montero-Odasso, 2012). There is some evidence showing that cognitive motor interventions such as virtual reality-based interventions could reduce the risks of falls in older persons with mild cognitive impairment and dementia (Thapa et al., 2020). However, the empirical research using VR technology intervention on the occupational therapy area is limited (Miranda-Dura et al., 2021). The study aims to investigate the effectiveness of Virtual Reality (VR) training as a meaningful occupation and an alternative cognitive motor training to reduce the falls risk by altering the cognition, physical risk factors of falls and the fear of falling in older adults with MCI.

VR is a human-centered technology interface that involves real-time simulated environment and interactions through multiple sensory channels (Mirelman et al., 2016). VR technology can be either semi-immersive or fully immersive. This research used a fully immersive VR Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) associated with sensing technology. The CAVE technology asks the participants to wear stereoscopic glasses which enable them to see 3D graphics and images so that they can walk all the way around the objects in a simulated scenario and get a full view and a better understanding of exactly how those objects look and what the real time environment is like. The adoption of VR CAVE training can be an innovation for the health profession. Researchers could advocate pilot use of an innovative training tool for preventing falls in older persons at the pandemic. Rehabilitation therapists are increasingly using assistive technology and Kinect motor sensor technology for older adults on home modifications, safe footwear device e.g. fall sensor, Kinect with Xbox or Nintendo Wii and tele-rehab educational program for falls prevention (Elliot et al., 2018). This study becomes a pilot and pioneer research project using commercially VR CAVE application on fall prevention for older adults with cognitive impairment. The study evaluated an emerging area for adoption of accessible technology in future rehabilitation and aged care services (Liddle, 2023).

VR CAVE intervention is an innovative approach in health professions, growing rapidly especially in rehabilitation and aged care (Gao, Lee, & McDonough, 2020, Miranda-Duro et al., 2021). The VR CAVE games activities provided simulated virtual environments, which engaged the users with the holographic stimulation of virtual experience (Baus, & Bouchard, 2014; Moreno et al., 2019). VR training may be a useful adjunct to falls prevention approaches in health-related applications. Supported with European projects such as the iStoppFalls, Farseeing and PreventIT project, this research explored using technology to improve older adults’ physical health and functioning (Boulton et al., 2019). For instance, iStoppFalls project used exergames to reduce the risk of falls in older adults. These projects provided an essential background and supporting evidence to fall prevention by adoption of technology. Exercise programs and interprofessional fall prevention programs are recommended as a useful fall prevention intervention strategy: clinicians such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists can use a professional-led fall prevention program in aged care services (Ohman, Savikko, & Strandberg, 2016, Miranda-Duro et. al., 2021, Montero-Odasso et al., 2022). Due to the Covid-19 outbreak between 2019-2022, the human-guided fall prevention program had been severely restricted or reduced in community aged care service. This could lead to an adverse effect on older adults’ physical mobility and cognitive decline, but also induced loneliness, boredom, and isolation. The new development of VR CAVE training can be an effective training platform to provide a holographic training environment for the older adults in a post-pandemic era. The use of VR technology is becoming more affordable and can be easy to operate as compared with therapist-lead exercise. It offers potential as a safe and interactive (alternative) approach to fall prevention strategy in adoption of future healthcare application.

There have been reports that wearing a head-mounted device may induce discomfort and agitation in older people (Bourrelier, & Ryard, 2016). To minimize the impact of motion sickness or dizziness when using VR technology applications, the VR CAVE technology is designed to be more user-friendly as 3D stereoscopic glasses are more convenient and comfortable for older adults than normal VR headsets. In addition, there exists a knowledge gap in developing useful clinical practice applications for fall prevention by using VR technology to reduce the fall risks among older adults with mild cognitive impairment (Hamm et al., 2016). Therefore, the study's objective is to evaluate the potential training effects of VR CAVE training for fall prevention in older adults with MCI. Health professions could consider the adoption of accessible VR CAVE technology in future healthcare practice.

2. Methods

This study was a quasi-experimental design with three measurements from pre-test, post-test and 3 months follow up. The study adopted a convenience sampling method as a feasible alternative at COVID-19 pandemic.

The stakeholders of community aged care facilities offered two hybrid modes including telecare and limited center-based social support services. With consent given from all stakeholders, the research was conducted in the university VR training center or the community aged care service centers.

2.1. Participants

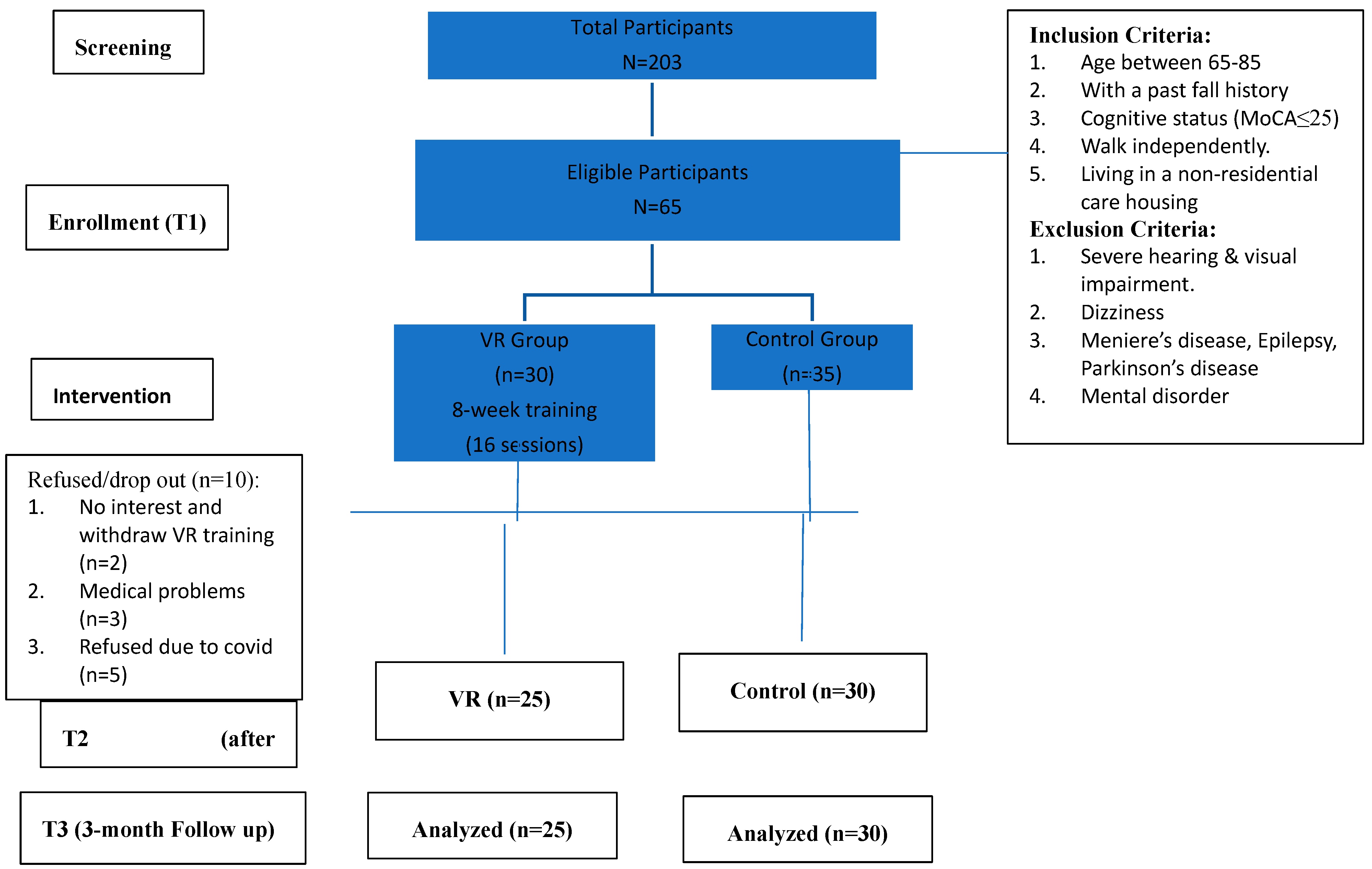

The sample size of the study had two hundred and three. All potential participants were involved in screening sessions for fall risks assessments co-organized by the research team and three aged care facilities. They were referred to by the staff through a promotion leaflet of the VR fall prevention research program held between June 2021 and November 2021. They provided informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The target population included the service members from three service settings in Hong Kong. The inclusion criteria were (1) aged 65 years to 85 years inclusive; (2) had a history of a fall within the past two years; (3) living in a non-residential age housing; (4) at risk of mild cognitive impairment, assessed by a validated screening tool of Hong Kong Montreal Cognitive assessment test (HK-MoCA score ≤25), indicating a risk of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia; (5) able to commute independently. These criteria must be satisfied prior to enrolment procedures taken in community aged care facilities.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria were medically unfit and physical complaints such as dizziness, motion sickness, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and mobility impairments and mental health challenges.

2.4. Intervention

The intervention program was called the VirCube VR for Rehab program, designed by a local information technology company. The VR company provided continuous technical and maintenance services in the research period. The ownership of the program belonged to the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences of The Hong Kong Polytechnic university. The researcher of the study declared no conflict of interest with the VR company; all research coordination, communication, and operations were restricted to the VR research office of the university.

The university VR CAVE research center installed the VirCube VR for Rehab program for research purposes. To match with the aims of the study, cognitive-motor training programs were chosen for the intervention program. The VR games modules for this study included fire emergency handling, outdoor walking, balancing game activities and community daily practices. The training modules involved dual task components; the participant was expected to train up his/her cognitive motor performances in an intensive VR technology-based training program. VR group participants received 2 sessions per week, 16 training sessions in total. Each session consisted of three to four training modules. Each module took 10-15 minutes to complete with a short break before the next module. The VR training session was about 45 minutes and monitored by the research team. The VirCube VR for Rehab program had detailed instruction and training protocol (additional file 1).

The control group did not receive any VR training in the community aged care centres. They received ordinary center-based social care service in community aged care centres. Some services resumed center-based health check service and social support services during pandemic. The control group participants were invited to take pretest, post-test and 3 months follow up measurements in the same period of VR group (T1, T2 and T3 intervals) in respective service centres.

2.5. Procedure

The VirCube VR for Rehab program and all VR CAVE facilities were built-in on a university VR research centre. The VR participants could commute independently to receive the 16-sessions VR training. On every VR session, all participants were supervised by the research team. They could stop the training at any time to avoid overloading during the repeated VR training. After completion of the VR session, the research team would collect the participants’ feedback and provide a debriefing session. Pictures A to G display the VR wearing devices, VR CAVE physical set up and cognitive-motor VR games (additional file 1). The VR game instruction and training protocol are documented in additional file 2.

2.6. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

The research participants gave consent to provide demographic information including personal, past falls history and other health information such as global cognitive status, and past medical history. The measurement of falls risk focused on different risk factors of falls (WHO, 2008). Fall efficacy included the concern of the fear of falling (Scheffer et al., 2008; Yardley et al., 2005).

2.7. Cognitive Measures

The level of cognitive function was screened by the Hong Kong Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA version). This validated assessment tool covered four domains including attention, executive functions/language, orientation, and memory. The total score ranged from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating better cognitive function. This screening tool had a good validity in detecting people with mild cognitive impairment (Yeung et al., 2020). A score of 25 or below indicated a higher risk of cognitive impairment or decline. Testing executive function of research participants was one of the indicators to detect the change of cognitive level after VR intervention. Two executive function tests were chosen such as The Trail Making Tests (TMT-A and TMT-B) for measuring the changes of executive function performance (Lei, & Erin, 2000).

2.8. Physical Measures

The intrinsic risk factors of falls were mainly assessed by the physical balance and stability and walk speed for the participants in three intervals. Three validated assessment tools including Berg Balance Scale (BBS), 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and Time Up and Go test (TUG) were used to measure the physical balance and mobility of the older adults in the risks of falling (Bandara et al., 2020).

The physical balance and level of stability were assessed by BBS. It consisted of 14 motor tasks; each scale ranged from 0 (unable) to 4 (independent). The higher the score, the greater the physical balance and stability. The BBS scale was a sensitive tool for older adults in an ageing population (Muir et al., 2008). For instance, scores below 45 indicated individuals with a greater risk of falling. A score below 51 with history of falls indicated a predictive risk of fall.

Another standardized fall risk assessment tool for older adults was the TUG. The participants were asked to get up from chair, walk 3 meters, turn around, walk back to chair, and sit down, and the time taken was recorded (Bischaff et al., 2003). Those participants scored the TUG (below 12 seconds) indicating a lower risk of fall. The 6MWT indicated the participants’ walking speed and physical level of tolerance, the longer the walking distance the stronger their physical condition.

2.9. Psychological Consideration

Fear of falling was measured by the Fall Efficacy International Scale (FES-I). This scale was a 16-item self-rated questionnaire in a Chinese version. The participants rated a score for the level of fall concern while engaging in daily occupations. It was a 4-point Likert scale with 1 as low concern and 4 as high concern of falling. It indicated the higher the score, the higher the fear concern of falling. The FES-I (Chinese version) was divided into three levels, 16-19 indicating low concern of falling, a score 20-27 indicating moderate concern and a score 28-64 indicating high concern (Yardley et al., 2005). The study chose the validated FES-I tool to assess the level of fall concerns between the intervention group and the control group.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome recorded the number of falls after the study, the secondary outcomes compared the changes in measurable variables in the three points (Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3). The statistical method was using SPSS version 27 and a

p value set ≤.05.

Table 1 showed the participants’ information such as the baseline demographic characteristics of participants including age, gender, educational level, living and cognitive status, history of fall and past health history such as chronic pain, osteoporosis, and fracture.

To compare the physical health outcomes between the two groups across time occasions, the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for data analysis. The independent variable was a time factor; the dependent variables include cognitive and physical functions. When any variable between the two groups found a significant difference in baseline measurement, comparison of covariance was applied. However, there was missing data found in the study, an intention-to-treat analysis was performed according to a last observation carried forward method.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

Sixty-five participants were considered eligible and were given formal consent to enroll in the study (

Figure 1). Fifty-five participants finally completed all measurements, with a mean age of 74.84% to 89.1% of the participants were female, 52.5% of the participants had an education level of secondary or above, and 32.7% of the participants were living alone in community (non-residential aged care facility). They were classified as having a higher risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia (mean score HK-MoCA= 21.22), and they had a higher rate of repeated fall within 12 months (50.9%). About 38.2% had reported chronic pain and 29.1% had a history of fracture due to a fall.

Some of the sixty-five eligible enrolled participants dropped out unexpectedly due to medical reasons (n=3) and loss of interest (n=2) in the VR group, some (n=5) in the control group refused to continue due to spreading anxiety. In total 10 participants dropped out throughout the study; the refusal rate in the VR group (n=2) was less than the control group (n=5). Finally, 84.62% (n=55) participants were analyzed for investigating the relationship between Virtual Reality technology-based training and the risk factors of fall.

As shown in

Table 1, there were no significant differences between the two groups in any of the demographic information. All participants were female in the intervention group, they had a higher education level (60% with secondary level) than the control group (46.7%). The intervention group had higher incident rate (53.3%) of fall history (<12 months), the history of fracture (40%) and chronic pain (44%). The control group had a higher incident rate (50%) of history of Osteoporosis than the intervention group (35.3%).

3.2. Demographic Data (Health Outcomes)

As shown in

Table 2, there were no significant differences (p>.05) between the two groups in executive function (TMT-A and TMT-B), balance (BBS) and 6-minute walk (6MWT) tests. Three other outcome measures including cognition (HK-MoCA), functional status (TUG) and fall efficacy (FESI) showed significant difference (p<.05) at baseline measurement. The HK-MoCA mean score (VR M=22.68; control M=20.00) of cognitive status in the two groups indicated a higher risk of cognitive decline such as mild cognitive impairment or dementia. The cut-off score of HK-MoCA screening tool was 22, indicating a higher risk of cognitive impairment, which is recommended for further medical investigation (Sarah et al., 2015, Yeung et al., 2020). The functional mobility (TUG, mean score=15.01) of the control group indicated a higher risk of fall. Regarding the fall efficacy international scale (FES-I), the two groups indicated a high concern of falling (high concern of fall when FES-I >28). Some variables in the two groups were not identical at the baseline measurement.

Importantly, the falls incident in the VR group (n=2) indicated about 50% lesser rate of fall than the control group (n=5) after the study. Hospital admission of participants (n=3) was reported in the control group only.

The study's secondary outcomes were illustrated in the table of multivariate and univariate of dependent variables between groups and time effects (

Table 3). There were significant differences in cognition (HK-MoCA, p=.008), executive function (TMT-A, p=.38, TMT-B, p=.006), balance level (BBS, p=.032), and walk speed (6MWT, p=.001) between the two groups at pre-test, post-test and follow up. These outcomes indicated greater improvement effects between groups and times in the intervention group. However, there were no significant differences in functional mobility (TUG, p=.938) and fall efficacy level (FES-I, p=.148) between groups and occasions. The effect of executive function (TMT-B, p=.172) showed an inconsistent result within the VR group in the follow-up. The intervention group (TMT-B, mean difference=-10.28s) showed faster time than the control group (TMT-B, mean difference= +30.18s). For the balance outcome measure, the mean score (BBS, at post-test=52.84 and follow up =53.21) indicated less predictive risk of falls (BBS score > 51) in the intervention group. The mean score of Time Up and Go Test (TUG) of the intervention group at post-test (9.27s) and follow up (8.46s) below 12s indicated a lesser risk of falls compared with the control group. The HK-MoCA means scores of the intervention group at post-test (25.72) and follow up (25.96) were indicating a lesser risk of mild cognitive impairment or decline than the control group. Although the fall efficacy showed no significant difference between the two groups, the intervention group showed greater improvement in the mean scores of FES-I (mean score=39.00 at post-test and mean score=33.48 at follow up), but the mean score indicated no significant decrease in fear concern of falling (FES-I>28) after intervention. Figure 2 to Figure 8 showed the changes of different variables over time between the two groups (additional file 3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

The study showed significant improvement on cognitive motor functions among older adults with MCI by adopting the VR CAVE training program (VirCube VR). The results supported the promising evidence of greater improvement in physical outcomes on the VR group after training. The VR CAVE technology application proved to be an alternative training method on falls prevention program for older adults with MCI and dementia (Kim, & Pang, 2019; Kwan et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2019).

4.2. Full Immersive VR CAVE Training on Falls Prevention

It was an exploratory study using the innovation application of VR CAVE program focusing on reducing the risks of falls among Chinese older adults with MCI in Hong Kong. The research design selected simulated VR games relating to the aims of the research project, designing and modifying a stimulated falls prevention program in the VR group. The findings were like recent reviews supporting the possible effects of VR training for fall prevention, which showed significant improvement on physical and cognitive outcomes. The holographic VR games were specially redesigned and beneficial for people with old age (Law et al., 2014; Stanmore et al., 2019). Unexpectedly, the research design countered shortcomings in limited workforce resources in addition to the VR system and facilities accessibility during COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong.

The study suggested an optimal falls prevention training protocol using VR CAVE technology 2 days per week for 8 weeks (about 2 months), with each VR session lasting less than 45 minutes and 16 training sessions in total (Kim & Pang, 2019; Law et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2020). For the VR CAVE program, each participant was suggested to take a break to avoid mental fatigue in between every VR game. The overall feedback of VR participants was very encouraging and rewarding. Few participants (16% drop out rate) were reported to quit the VR training for health and personal reasons. The VR motion sickness was minimized by 3D stereoscopic eyewear which is a handy VR CAVE design. The study allowed flexibility for participants to complete the 16 sessions for longer than 8 weeks (about 2 months) because of the unexpected circumstances during the pandemic in Hong Kong. In the end, still a high completion rate (100%) of the participants was achieved in the study. The participants also expressed extremely high satisfaction on improving their physical health outcomes and reducing the fear of falling after the innovative VR CAVE program. The evaluation study did not cover the qualitative data to measure the participant-observational evaluation. Advisably, it could be a good suggestion to consider a focus group or participants’ survey on their intentions and perceptions to use VR technology in the future.

4.3. Training Effects of VR Training for Fall Prevention

The research findings supported the potential evidence that VR CAVE training was effective in stimulating cognitive motor functions for the participants (Irazoki et al., 2020; Kim, & Pang, 2019). It further supported the evidence on training effects of the VR training for fall prevention in older adults with MCI. From a literature review, the cognitive function was associated with a risk of falling and poor postural balance indicated a higher risk of falls (Delbaere et al., 2012; Montero-Odasso, & Speechley, 2019; Fu et al., 2015). People with MCI showed higher risk of falls than community-dwelling older adults (Welmer et al., 2017). Beyond that, the VR CAVE training experience was so interactive and stimulating among VR participants that they showed high motivation, cohesiveness, and training compliance on VR falls prevention training program.

However, there was inconsistent evidence on improving the functional mobility and reducing the fear concern of falling in the two groups. At T1, the scores of TUG and FES-I between the two groups showed significant difference. VR participants showed higher functional mobility level and less fear concern of falling. The intervention effect of VRT was not statistically significant due to a potential selection bias. Statistically, the mean scores of the fear concern of falling of the two groups were similar after the VRT intervention. The VR group had shown significant improvement than the control group on the fall efficacy.

However, the VR CAVE program's primary design focused on cognitive motor intervention (dual-task component) which might not be sufficient to address the fear of falling. The 16-item self-rated questionnaire (FES-I) was a subjective assessment scale and targeted for the general ageing population, with items mainly focused on daily living tasks. Participants with cognitive impairments found it difficult to interpret and understand each question particularly under so many restrictions for living in the community during the pandemic period in Hong Kong. The FES-I international scale might not be the best standardized assessment tool to assess the fear of falling specifically for older adults with MCI. Overall, the results might be impacted by selection bias, the suitability of assessment tools, and other environmental constraints. Because the training program was conducted in The Hong Kong XXX University, the participants had to spend longer time on commuting which was indeed a tougher physical demand to undertake for the training sessions. Comparatively, those participants with lower physical mobility and higher fear of falling would become more reluctant and have difficulties opting for the VR group. In general, the VR participants might show better functional mobility (TUG) than the control group.

4.4. Challenges and Limitations

Compared with other VR research (Chau et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2019; Zahabi, & Abdul, 2020), the recruitment of participants for this study was challenging. The sample size of the study was small, but the dropout rate (15.38%) seemed comparatively low. Convenience sampling could lead to potential bias and affect the reliability of the findings in older population (Nikolopoulou, 2022). The VR group achieved a 100% attendance rate for VR training. The participants were actively engaged in the VR CAVE training with positive perception and acceptance using the application of VR CAVE program. The other benefits of the study showed good social and peer support as well as great enjoyment on learning VR technology among the participants in the study. Certainly, the positive effect of face-to-face interaction and interactive learning could promote being mentally and physically active and eliminate social isolation and boredom during the pandemic (Gao, Lee, & McDonough, 2020; Ng et al., 2019). Findings of the study were identical to these observations indicating the VR CAVE training was effective with a positive training effect. Future study is recommended to investigate the participants’ acceptance of and perception towards using full immersive VR technology intervention.

The study has major limitations, it was a non-randomized control trial design, affecting the validity and reliability of the findings due to sampling bias and sample small size. The researcher admitted the predictive limitation because the study had encountered many restrictions to implement a face-to-face experimental study in Hong Kong. Secondly, the improvement of cognitive and executive function tests as repeated measured by MoCA and TMTA/B results could be affected by repeated learning (Sarah, 2015). Thirdly, the group size between the intervention group and control group was not idential, and the VR participants showed higher motivation and engagement to take part in the research. These factors could contribute to a potential bias effect. Fourthly, the VR CAVE intervention had limited functions and merely focused on intrinsic factors of fall risks reduction because it was a tailor-made dual-task virtual simulated training program. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), falls prevention was complex to manage, and a multifactorial program was used to reduce the multiple risks of falls because of their complexity (WHO, 2004; Morello et al., 2019)

Finally, the challenges and demands for participants in the VR group were higher than the control group. The research team consumed workforce resources and faced difficulties tackling research coordination including the participants’ availability, facility arrangement and other technical issues. The data collection of follow up was heavily suspended due to a complete lockdown in Hong Kong between January 2022 to May 2022. The Hong Kong Polytechnic university and the community social service centers suspended all research projects and daily services in Hong Kong. The 3-month follow-up work in the two groups was delayed. The process of data collection might have adversely affected such as the higher dropout rate and unforeseeable factors because some participants refused to continue taking the study during this period. As an alternative, the research team adopted a special arrangement to maintain contact with the participants by phone call and other social means e.g. WhatsApp group. Thus, the research adopted the intention-to-treat method for data analysis.

5. Conclusion

The study supported evidence on the potential training effects of VR training for fall prevention in older adults with MCI by deploying VR CAVE application (VirCube VR). The VR CAVE program in falls prevention was evidently supported as potential VR technology training in aged care and rehabilitation services. The VR CAVE intervention could be an innovative and alternative training approach in future healthcare practice. Health professions such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists can expand the scope and make use of VR in many rehabilitation services. However, the demand for technological support when using VR applications is crucial particularly for an ageing population. In future, similar studies should be considered to be a bigger sample size with a RCT experimental design to uphold the generalizability of VR CAVE training for fall prevention in older adults with MCI.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualizing the study, methodology, data analysis, and reviewing the current version. Dr Wing Keung Ip contributed to investigation, writing the original draft preparation and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Review Committee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (reference number HSEARS20210317007) and The University of Southern Queensland (application number USQ AEC H21REA071).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All authors support sharing the research data and are available from the corresponding author upon request. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section ‘MDPI Research Data Policies’ at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the University of Southern Queensland. The authors wish to thank The Salvation Army and St. James Settlement in Hong Kong for offering support and contributions to the research project.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Bandara KMT, Ranawaka UK, Pathmeswaran A (2020) Usefulness of Timed Up and Go test, Berg Balance Scale and Six Minute Walk Test as fall risk predictors in post stroke adults attending Rehabilitation Hospital Ragama. http://ir.kdu.ac.lk/handle/345/2958.

- Baus O, Bouchard S (2014) Moving from virtual reality exposure-based therapy to augmented reality exposure-based therapy: a review. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 8, 112. [CrossRef]

- Bischoff HA, Stähelin HB, Monsch AU, Iversen MD, Weyh A, Von Dechend M, Theiler R (2003) Identifying a cut-off point for normal mobility: a comparison of the timed ‘up and go’ test in community-dwelling and institutionalized elderly women. Age and ageing, 32(3), 315-320. [CrossRef]

- Boulton E, Hawley-Hague H, Vereijken B, Clifford A, Guldemond N, Pfeiffer K, Todd C (2016) Developing the FARSEEING Taxonomy of Technologies: Classification and description of technology use (including ICT) in falls prevention studies. Journal of biomedical informatics, 61, 132-140. [CrossRef]

- Boulton E, Hawley-Hague H, French DP, Mellone S, Zacchi A, Clemson L, Todd C (2019) Implementing behaviour change theory and techniques to increase physical activity and prevent functional decline among adults aged 61–70: The PreventIT project. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 62(2), 147-156. [CrossRef]

- Bourrelier J, Ryard J (2016) Use of a virtual environment to engage motor and postural abilities in elderly subjects with and without mild cognitive impairment (MAAMI Project). IRBM. 37(2),75-80. [CrossRef]

- Chau, PH, Kwok YYJ, Chan MKM, Kwan KYD, Wong KL, Tang YH, Leung MK (2021) Feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of virtual reality training for older adults and people with disabilities: single-arm pre-post study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(5), e27640. [CrossRef]

- Coyle H, Traynor V, Solowij N (2015) Computerized and virtual reality cognitive training for individuals at high risk of cognitive decline: systematic review of the literature. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(4), 335-359. [CrossRef]

- Delbaere K, Kochan NA, Close JC, Menant JC, Sturnieks DL., Brodaty, H, Lord, SR (2012) Mild cognitive impairment as a predictor of falls in community-dwelling older people. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(10), 845-853. [CrossRef]

- Elliott S, Leland, NE (2018) Occupational therapy falls prevention interventions for community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(4), 7204190040p1-7204190040p11. [CrossRef]

- Fu AS, Gao KL, Tung AK, Tsang WW, Kwan MM (2015) Effectiveness of exergaming training in reducing risk and incidence of falls in frail older adults with a history of falls. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 96(12), 2096-2102. [CrossRef]

- Gao Z, Lee J, McDonough D (2020) Virtual Reality Exercise a Coping Strategy for Health and Wellness Promotion in Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9,1986; [CrossRef]

- Ge S, Zhu Z, Wu B, McConnell ES (2018) Technology-based cognitive training and rehabilitation interventions for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. BMC Geriatric, 18(1), 213. [CrossRef]

- Hamm J, Money AG, Atwal A, Paraskevopoulos I (2016) Fall prevention intervention technologies: A conceptual framework and survey of the state of the art. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 59, 319-345. [CrossRef]

- Iakovidis P, Lytras D, Fetlis A, Kasimis K, Ntinou SR, Chatzikonstantinou P (2023) The efficacy of exergames on balance and reducing falls in older adults: A narrative review. International Journal of Orthopaedics Sciences, 9(1), 221-225. [CrossRef]

- Irazoki E, Contreras-Somoza LM, Toribio-Guzman JM, Jenaro-Rio C, van der Roest H, Franco-Martin MA (2020) Technologies for Cognitive Training and Cognitive Rehabilitation for People With Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. A Systematic Review. Front Psychol, 11, 648. [CrossRef]

- Kim O, Pang Y, Kim JH (2019) The effectiveness of virtual reality for people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry, 19(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kwan RYC, Liu JYW, Fong, KNK, Qin J, Leung PK, Sin OSK, Lai CK (2021) Feasibility and Effects of Virtual Reality Motor-Cognitive Training in Community-Dwelling Older People With Cognitive Frailty: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games, 9(3), e28400. [CrossRef]

- Law LL, Barnett F, Yau MK, Gray MA (2014) Effects of combined cognitive and exercise interventions on cognition in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Ageing Research Review. 2014; 15:61–75. [CrossRef]

- Lei L, Erin DB (2000) Performance on Original and a Chinese Version of Trail Making Test Part B: A Normative Bilingual Sample, Applied Neuropsychology, 7:4, 243-246, . [CrossRef]

- Liddle J (2023) Considering inclusion in digital technology: An occupational therapy role and responsibility. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 70: 157-158. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Duro MDC, Nieto-Riveiro L, Concheiro-Moscoso P, Groba B, Pousada T, Canosa N, Pereira J (2021) Occupational therapy and the use of technology on older adult fall prevention: a scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(2), 702. [CrossRef]

- Mirelman A, Rochester L, Maidan I, Del Din S, Alcock L, Nieuwhof F, Hausdorff, JM (2016) Addition of a non-immersive virtual reality component to treadmill training to reduce fall risk in older adults (V-TIME): a randomized controlled trial. The Lancet, 388(10050), 1170-1182. [CrossRef]

- Mirelman A, Maidan I, Shiratzky SS, Hausdorff JM (2020) Virtual Reality Training as an Intervention to Reduce Falls. In: Montero-Odasso, M., Camicioli, R. (eds) Falls and Cognition in Older Persons. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso M, Speechley M (2018) Falls in cognitively impaired older adults: implications for risk assessment and prevention. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(2), 367-375. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso M, Camicioli R (Eds.) (2019) Falls and cognition in older persons: fundamentals, assessment and therapeutic options. Springer Nature.

- Montero-Odasso M, Van Der Velde N, Martin FC, Petrovic M, Tan MP, Ryg J, Masud T (2022) World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age and ageing, 51(9), afac205. [CrossRef]

- Morello RT, Soh SE, Behm K, Egan A, Ayton D, Hill K, Barker AL (2019) Multifactorial falls prevention programmes for older adults presenting to the emergency department with a fall: systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury prevention, 25(6), 557-564. [CrossRef]

- Myers AH, Baker SP, Van Natta ML, Abbey H, Robinson EG (1991) Risk factors associated with falls and injuries among elderly institutionalized persons. American journal of epidemiology, 133(11), 1179-1190. [CrossRef]

- Ng YL, Ma F, Ho FK, Ip P, Fu KW (2019) Effectiveness of virtual and augmented reality-enhanced exercise on physical activity, psychological outcomes, and physical performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 278-291. [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou K (2022) What Is Convenience Sampling? Definition & Examples. Scribbr. https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/convenience-sampling/.

- Ohman H, Savikko N, Strandberg TE (2016) Effects of exercise on cognition: the Finnish Alzheimer disease exercise trial: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of American Geriatric Society: 64:731-38. [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S (1991) Journal of American Geriatric Society: Mar;39(2):142-148. [CrossRef]

- Sarah AC, Jodi MH, Jacob D, Bolzenius LE, Salminen LM, Baker SS, Robert HP (2015) Longitudinal Change in Performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in Older Adults,The Clinical Neuropsychologist,29:6,824-835. [CrossRef]

- Scheffer AC, Schuurmans MJ, van Dijk N, van der Hooft T, de Rooij SE (2008) Fear of falling: Measurement strategy, prevalence, risk factors and consequences among older persons. Age and Ageing, 37,19–24. [CrossRef]

- Shema SR, Bezalel P, Sberlo Z, Giladi N, Hausdorff J, Mirelman A (2017) Improved mobility and reduced fall risk in older adults after five weeks of virtual reality training. Journal of Alternative Medicine Research, 9(2), 171-175.

- Stanmore EK, Mavroeidi A, de Jong LD, Skelton DA, Sutton CJ, Benedetto V, Todd C (2019) The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of strength and balance Exergames to reduce falls risk for people aged 55 years and older in UK assisted living facilities: a multi-centre, cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC medicine, 17, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Thapa N, Park HJ, Yang J, Son H, Lee MJ, Kang SW, Park KW, Park H (2020) The Effect of a Virtual Reality-Based Intervention Program on Cognitive in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine 9,1283. [CrossRef]

- Todd C, Skelton D (2004) What are the main risk factors for falls amongst older people and what are the most effective interventions to prevent these falls? World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/363812.

- Welmer AK, Rizzuto D, Laukka EJ, Johnell K, Fratiglioni L (2017) Cognitive and physical function in relation to the risk of injurious falls in older adults: a population-based study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72(5), 669-675. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2008). WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43811.

- World Health Organization (2021) Step safely: strategies for preventing and managing falls across the life-course.

- Yang CM, Hsieh JSC, Chen YC, Yang SY, Lin HCK (2020) Effects of Kinect exergames on balance training among community older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine, 99(28). [CrossRef]

- Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C (2005) Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age and ageing, 34(6), 614-619. [CrossRef]

- Yeung PY, Wong LL, Chan CC, Yung CY, Leung LJ, Tam YY, Lau ML (2020) Montreal cognitive assessment—single cutoff achieves screening purpose. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2681-2687. [CrossRef]

- Zahabi M, Abdul Razak AM (2020) Adaptive virtual reality-based training: a systematic literature review and framework. Virtual Reality, 24, 725-752. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).