Submitted:

29 August 2024

Posted:

29 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Experimental Apparatus and Control

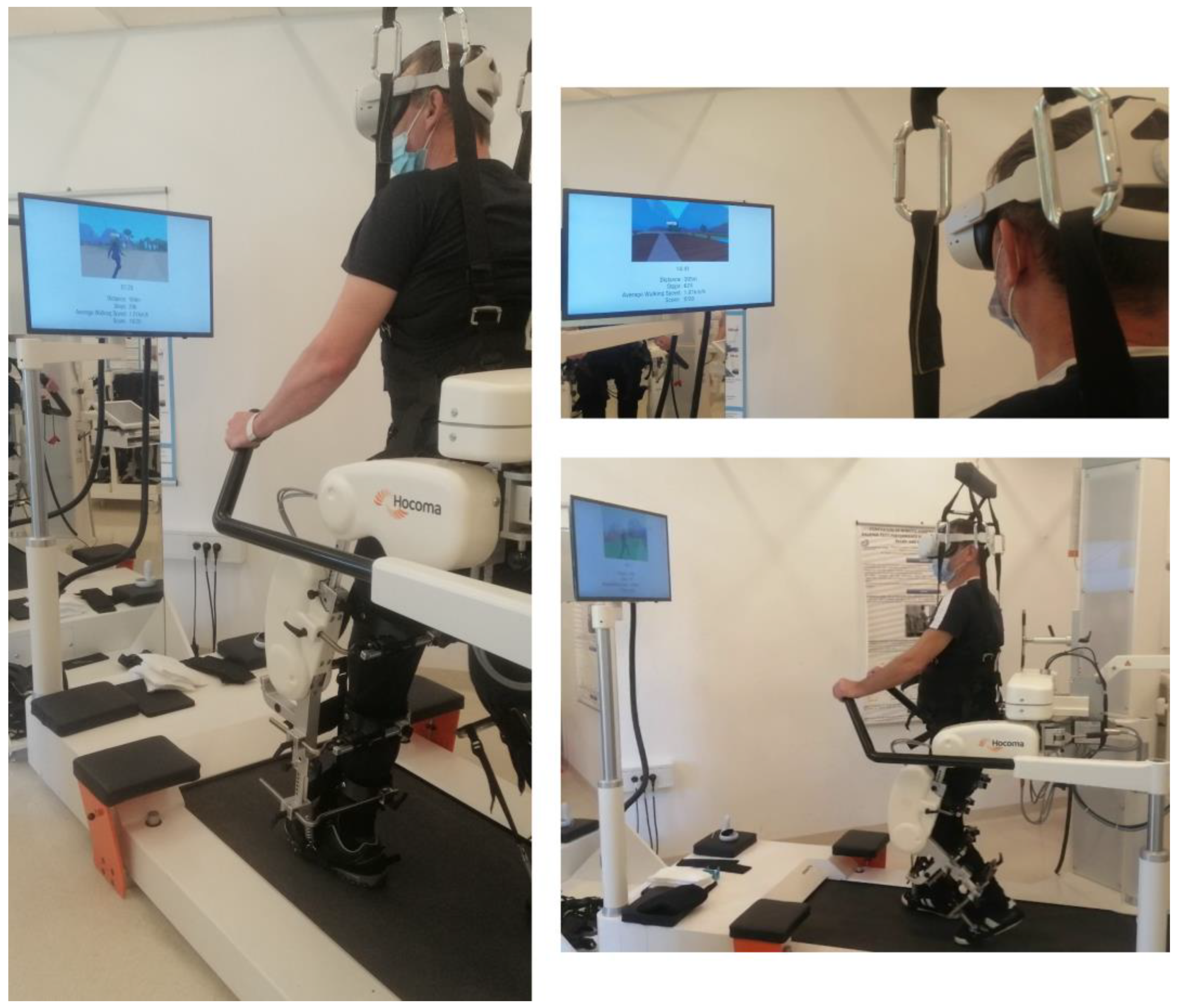

2.3.1. Robot Assisted Gait Training Device

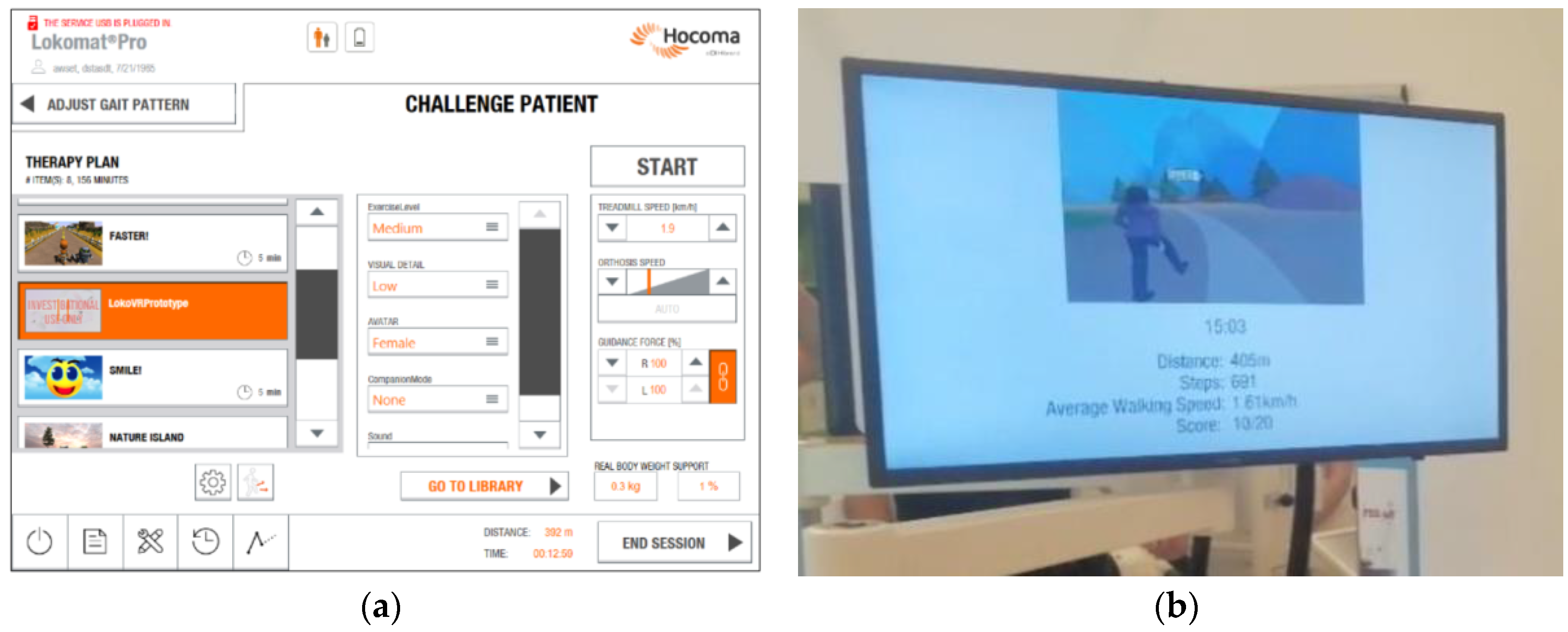

2.3.2. Immersive Virtual Environment

2.4. Treatment Procedures

2.5. Assessment Procedures

2.5.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

2.5.2. Feasibility and Session Adherence

2.5.3. Acceptance

2.6. Data Collection and Management

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.1. Feasibility and Session Adherence

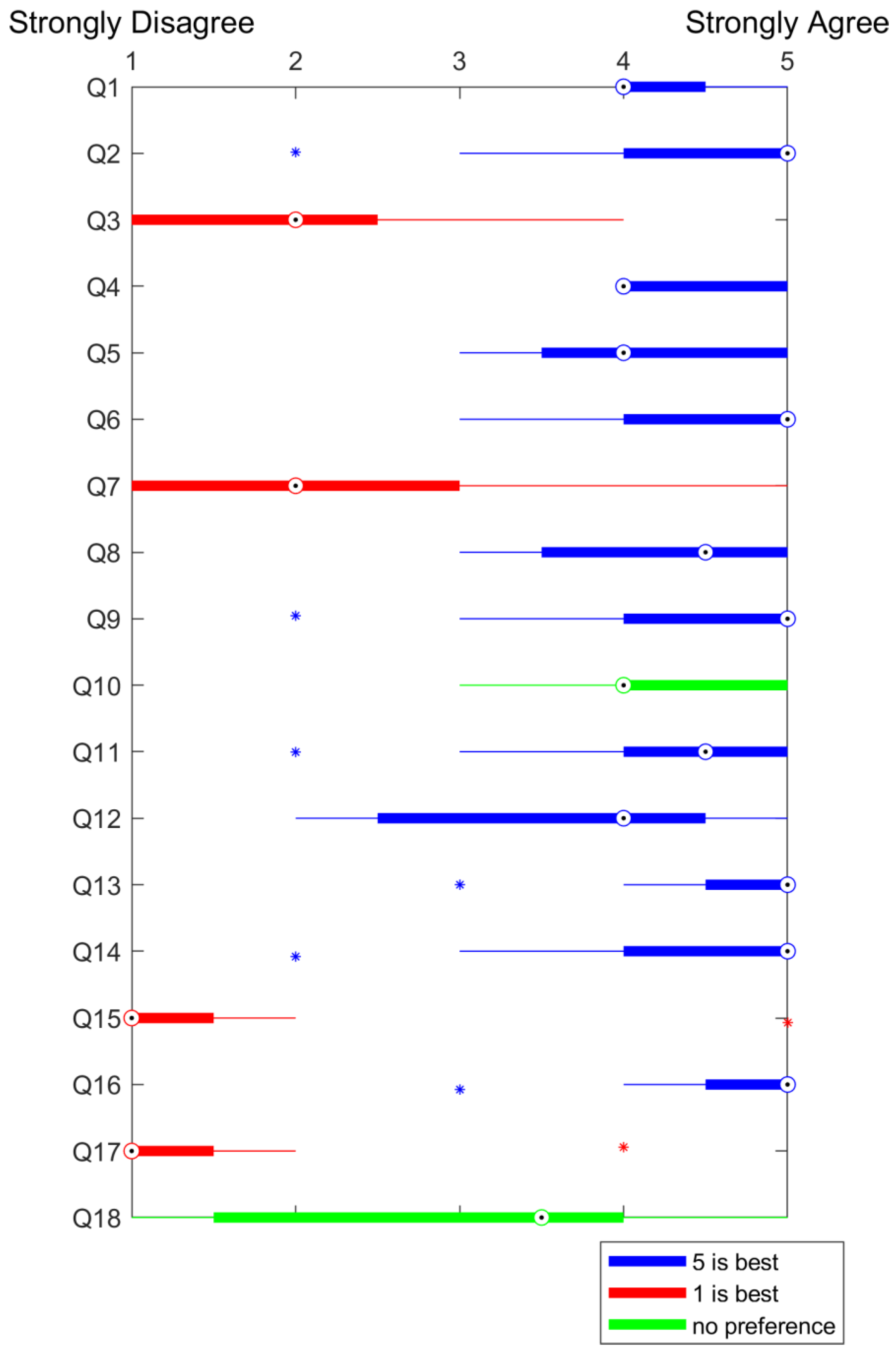

3.2. Acceptance

3.3. Further Observations

4. Discussion

4.1. Feasibility

4.2. Acceptance

4.3. Future Directions

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nieto-Escamez, F.; Cortés-Pérez, I.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Fusco, A. Virtual Reality Applications in Neurorehabilitation: Current Panorama and Challenges. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, W.; Khan, Z.Y.; Jawaid, A.; Shahid, S. Virtual Reality (VR)-Based Environmental Enrichment in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and Mild Dementia. Brain Sci 2021, 11, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, M.; De Luca, R.; De Nunzio, A.M.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Innovative Technologies in the Neurorehabilitation of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2022, 12, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassert, R.; Dietz, V. Rehabilitation Robots for the Treatment of Sensorimotor Deficits: A Neurophysiological Perspective. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2018, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolářová, B.; Šaňák, D.; Hluštík, P.; Kolář, P. Randomized Controlled Trial of Robot-Assisted Gait Training versus Therapist-Assisted Treadmill Gait Training as Add-on Therapy in Early Subacute Stroke Patients: The GAITFAST Study Protocol. Brain Sci 2022, 12, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J.; Krewer, C.; Bauer, P.; Koenig, A.; Riener, R.; Müller, F. Virtual Reality to Augment Robot-Assisted Gait Training in Non-Ambulatory Patients with a Subacute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2018, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanatta, F.; Farhane-Medina, N.Z.; Adorni, R.; Steca, P.; Giardini, A.; D’Addario, M.; Pierobon, A. Combining Robot-Assisted Therapy with Virtual Reality or Using It Alone? A Systematic Review on Health-Related Quality of Life in Neurological Patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2023, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedergård, H.; Arumugam, A.; Sandlund, M.; Bråndal, A.; Häger, C.K. Effect of Robotic-Assisted Gait Training on Objective Biomechanical Measures of Gait in Persons Post-Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2021, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loro, A.; Borg, M.B.; Battaglia, M.; Amico, A.P.; Antenucci, R.; Benanti, P.; Bertoni, M.; Bissolotti, L.; Boldrini, P.; Bonaiuti, D.; et al. Balance Rehabilitation through Robot-Assisted Gait Training in Post-Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postol, N.; Marquez, J.; Spartalis, S.; Bivard, A.; Spratt, N.J. Do Powered Over-Ground Lower Limb Robotic Exoskeletons Affect Outcomes in the Rehabilitation of People with Acquired Brain Injury? Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2019, 14, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-Y.; Tsai, J.-L.; Li, G.-S.; Lien, A.S.-Y.; Chang, Y.-J. Effects of Robot-Assisted Gait Training in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabro’, R.S.; Cassio, A.; Mazzoli, D.; Andrenelli, E.; Bizzarini, E.; Campanini, I.; Carmignano, S.M.; Cerulli, S.; Chisari, C.; Colombo, V.; et al. What Does Evidence Tell Us about the Use of Gait Robotic Devices in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis? A Comprehensive Systematic Review on Functional Outcomes and Clinical Recommendations. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwardat, M.; Etoom, M.; Al Dajah, S.; Schirinzi, T.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Sinibaldi Salimei, P.; Biagio Mercuri, N.; Pisani, A. Effectiveness of Robot-Assisted Gait Training on Motor Impairments in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2018, 41, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Dattola, V.; De Cola, M.C.; Logiudice, A.L.; Porcari, B.; Cannavò, A.; Sciarrone, F.; De Luca, R.; Molonia, F.; Sessa, E.; et al. The Role of Robotic Gait Training Coupled with Virtual Reality in Boosting the Rehabilitative Outcomes in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2018, 41, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszlo, C.; Munari, D.; Maggioni, S.; Knechtle, D.; Wolf, P.; De Bon, D. Feasibility of an Intelligent Algorithm Based on an Assist-as-Needed Controller for a Robot-Aided Gait Trainer (Lokomat) in Neurological Disorders: A Longitudinal Pilot Study. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.; Ballester, B.R.; Verschure, P.F.M.J. Principles of Neurorehabilitation After Stroke Based on Motor Learning and Brain Plasticity Mechanisms. Front Syst Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino Cinnera, A.; Bisirri, A.; Chioccia, I.; Leone, E.; Ciancarelli, I.; Iosa, M.; Morone, G.; Verna, V. Exploring the Potential of Immersive Virtual Reality in the Treatment of Unilateral Spatial Neglect Due to Stroke: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2022, 12, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, D.; Georgieva, I.; Gong, Z.; Nanjappan, V.; Georgiev, G. Virtual Reality for Neurorehabilitation and Cognitive Enhancement. Brain Sci 2021, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, K.E.; Lange, B.; George, S.; Deutsch, J.E.; Saposnik, G.; Crotty, M. Virtual Reality for Stroke Rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keersmaecker, E.; Lefeber, N.; Geys, M.; Jespers, E.; Kerckhofs, E.; Swinnen, E. Virtual Reality during Gait Training: Does It Improve Gait Function in Persons with Central Nervous System Movement Disorders? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrò, R.S.; Russo, M.; Naro, A.; De Luca, R.; Leo, A.; Tomasello, P.; Molonia, F.; Dattola, V.; Bramanti, A.; Bramanti, P. Robotic Gait Training in Multiple Sclerosis Rehabilitation: Can Virtual Reality Make the Difference? Findings from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Neurol Sci 2017, 377, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Luan, Z.; Li, Y.; Peng, X. Upper Limb Rehabilitation System Based on Virtual Reality for Breast Cancer Patients: Development and Usability Study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0261220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, C.M. Motion Sickness: A Synthesis and Evaluation of the Sensory Conflict Theory. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1990, 68, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Chessa, M.; Solari, F. Mitigating Cybersickness in Virtual Reality Systems through Foveated Depth-of-Field Blur. Sensors 2021, 21, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Korner-Bitensky, N.; Levin, M. Virtual Reality in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review of Its Effectiveness for Upper Limb Motor Recovery. Top Stroke Rehabil 2007, 14, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munari, D.; Fonte, C.; Varalta, V.; Battistuzzi, E.; Cassini, S.; Montagnoli, A.P.; Gandolfi, M.; Modenese, A.; Filippetti, M.; Smania, N.; et al. Effects of Robot-Assisted Gait Training Combined with Virtual Reality on Motor and Cognitive Functions in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Pilot, Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2020, 38, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, G.; Joerg, M.; Schreier, R.; Dietz, V. Treadmill Training of Paraplegic Patients Using a Robotic Orthosis. J Rehabil Res Dev 2000, 37, 693–700. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, A.; Mannocchi, I.; Sassi, M.S.H.; Carli, M.; De Luca, G. De; Longo, U.G.; Denaro, V.; Schena, E. Virtual Reality for Shoulder Rehabilitation: Accuracy Evaluation of Oculus Quest 2. Sensors 2022, 22, 5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregna, G.; Schincaglia, N.; Baroni, A.; Straudi, S.; Casile, A. A Novel Immersive Virtual Reality Environment for the Motor Rehabilitation of Stroke Patients: A Feasibility Study. Front Robot AI 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, C.; Kern, F.; Gall, D.; Latoschik, M.E.; Pauli, P.; Käthner, I. Immersive Virtual Reality during Gait Rehabilitation Increases Walking Speed and Motivation: A Usability Evaluation with Healthy Participants and Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Stroke. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2021, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.K.; Gill, K.M.; Magliozzi, M.R. Gait Assessment for Neurologically Impaired Patients. Phys Ther 1986, 66, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. J Psychiatr Res 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, F.; Tannock, I. Use and Misuse of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events in Cancer Clinical Trials. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of Healthcare Interventions: An Overview of Reviews and Development of a Theoretical Framework. BMC Health Serv Res 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R. Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales. J Grad Med Educ 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsaki, I.; Dimitriadi, N.; Despoti, A.; Tzoumi, D.; Leventakis, N.; Roussou, G.; Papathanasiou, A.; Nanas, S.; Karatzanos, E. The Effectiveness of Immersive Virtual Reality in Physical Recovery of Stroke Patients: A Systematic Review. Front Syst Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiza, E.; Matsangidou, M.; Neokleous, K.; Pattichis, C.S. Virtual Reality Applications for Neurological Disease: A Review. Front Robot AI 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L.M.; Nilsen, D.M.; Gillen, G.; Yoon, J.; Stein, J. Immersive Virtual Reality Mirror Therapy for Upper Limb Recovery After Stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2019, 98, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohil, C.J.; Alicea, B.; Biocca, F.A. Virtual Reality in Neuroscience Research and Therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011, 12, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.-J.; Han, S. Perspective: Present and Future of Virtual Reality for Neurological Disorders. Brain Sci 2022, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; MacPherson, S.E. How Immersive Virtual Reality Methods May Meet the Criteria of the National Academy of Neuropsychology and American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology: A Software Review of the Virtual Reality Everyday Assessment Lab (VR-EAL). Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2021, 4, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.-S.; Hui, C.L.-M.; Suen, Y.-N.; Lee, E.H.-M.; Chang, W.-C.; Chan, S.K.-W.; Chen, E.Y.-H. Application of Immersive Virtual Reality for Assessment and Intervention in Psychosis: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-H.; Lee, H.-M. Effect of Immersive Virtual Reality-Based Bilateral Arm Training in Patients with Chronic Stroke. Brain Sci 2021, 11, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Xie, H.; Harp, K.; Chen, Z.; Siu, K.-C. Effects of Virtual Reality Intervention on Neural Plasticity in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2022, 103, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsangidou, M.; Ang, C.S.; Sakel, M. Clinical Utility of Virtual Reality in Pain Management: A Comprehensive Research Review. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 2017, 13, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthes, C.; G.-H.R.J.; W.M.; K.D. State of the Art of Virtual Reality Technology. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Aerospace Conference 2016, 1–19.

- Rogers, J.M.; Duckworth, J.; Middleton, S.; Steenbergen, B.; Wilson, P.H. Elements Virtual Rehabilitation Improves Motor, Cognitive, and Functional Outcomes in Adult Stroke: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2019, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sui, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ali, N.; Guo, C.; Wang, T. Effects of Virtual Reality Intervention on Cognition and Motor Function in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, K.G.; De Freitas, T.B.; Doná, F.; Ganança, F.F.; Ferraz, H.B.; Torriani-Pasin, C.; Pompeu, J.E. Effects of Virtual Rehabilitation versus Conventional Physical Therapy on Postural Control, Gait, and Cognition of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2017, 3, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leocani, L.; Comi, E.; Annovazzi, P.; Rovaris, M.; Rossi, P.; Cursi, M.; Comola, M.; Martinelli, V.; Comi, G. Impaired Short-Term Motor Learning in Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence from Virtual Reality. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2007, 21, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Dattola, V.; De Cola, M.C.; Logiudice, A.L.; Porcari, B.; Cannavò, A.; Sciarrone, F.; De Luca, R.; Molonia, F.; Sessa, E.; et al. The Role of Robotic Gait Training Coupled with Virtual Reality in Boosting the Rehabilitative Outcomes in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Rehabil Res 2018, 41, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Question Type | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Closed-ended | I think I can benefit from this technology |

| Q2 | Closed-ended | The use of Virtual Reality makes Lokomat training more enjoyable to me |

| Q3 | Closed-ended | The use of Virtual Reality makes me exercise harder in the Lokomat |

| Q4 | Closed-ended | The use of Virtual Reality adds challenge to the Lokomat training |

| Q5 | Closed-ended | I think this way Lokomat training can be more effective for me |

| Q6 | Closed-ended | I feel safe when using this technology |

| Q7 | Closed-ended | Use of this technology can have negative consequences I can’t predict |

| Q8 | Closed-ended | I feel confident when using the VR in the Lokomat |

| Q9 | Closed-ended | I feel like I can do what is required when using the VR in the Lokomat |

| Q10 | Closed-ended | I would rather have more things to do when walking in VR |

| Q11 | Closed-ended | I like the environment I walked in |

| Q12 | Closed-ended | I liked the companions that were walking with me |

| Q13 | Closed-ended | It feels like time flies when training in the Lokomat with VR |

| Q14 | Closed-ended | Wearing the VR headset is comfortable |

| Q15 | Closed-ended | I felt sick when walking in the VR |

| Q16 | Closed-ended | I felt comfortable during the training |

| Q17 | Closed-ended | Looking at virtual reality makes me dizzy |

| Q18 | Closed-ended | I forget I am in the clinic when training like this |

| Q19 | Open-ended | What did you like or dislike about the virtual environment you walked in? |

| Q20 | Open-ended | Which companion do you prefer to walk with, animal or human, and why? |

| Q21 | Open-ended | Was there something that you would have liked to do in the virtual environment that wasn't possible? |

| Q22 | Open-ended | Do you have any good ideas for something you would like to do in a virtual reality when in the Lokomat? |

| Number | Question Type | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Closed-ended | I felt confident operating the Lokomat together with the VR headset |

| Q2 | Closed-ended | The amount of time spent donning/doffing the VR headset is feasible for use in clinical practice |

| Q3 | Closed-ended | I am satisfied with the ease of operation of the device through the user interface |

| Q4 | Closed-ended | I was able to adjust the game settings to address the unique needs of individual subjects |

| Q5 | Closed-ended | Using the device did not interfere with my ability to provide appropriate supervision and guarding of the subject throughout all sessions |

| Q6 | Closed-ended | I was able to communicate with the patient during the training as needed |

| Q7 | Closed-ended | VR headset was compatible with gait training activities |

| Q8 | Closed-ended | I felt that VR had a positive impact on the subjects’ walking performance |

| Q9 | Closed-ended | I felt that the patient(s) enjoyed the VR training session |

| Q10 | Closed-ended | Using the Lokomat together with a VR headset would be useful in my clinical practice |

| Q11 | Closed-ended | I would recommend using the Lokomat together with a VR headset to other physiotherapists |

| Q12 | Open-ended | Please note 3 things you liked about using the Lokomat together with a VR headset |

| Q13 | Open-ended | Please note 3 things about using the Lokomat together with a VR headset you would like to change |

| PID. | Diagnosis | Affected side | Onset (months) | Age (years) |

Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Gender (M/F) | FAC (level) | Walking ability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCI | both | 48 | 33 | 162 | 60 | F | 1 | Wheelchair |

| 2 | SCI | both | 8 | 64 | 184 | 105 | M | 4 | Wheelchair |

| 3 | Stroke | right | 5 | 54 | 185 | 93 | M | 5 | Rollator |

| 4 | Stroke | left | 4 | 53 | 185 | 105 | M | 1 | Wheelchair |

| 5 | Stroke | right | 4 | 57 | 185 | 81 | M | 1 | Wheelchair |

| 6 | Stroke | right | 7 | 75 | 176 | 78 | M | 5 | Rollator |

| 7 | Stroke | left | 12 | 64 | 173 | 80 | M | 4 | Wheelchair |

| 8 | SCI | both | 4 | 51 | 174 | 83 | M | 4 | Wheelchair |

| 9 | Stroke | right | 5 | 46 | 194 | 108 | M | 5 | Crutches |

| 10 | Stroke | right | 4 | 48 | 191 | 104 | M | 4 | Wheelchair |

| 11 | SCI | both | 4 | 65 | 168 | 88 | M | 3 | Wheelchair |

| 12 | SCI | both | 4 | 70 | 177 | 73 | M | 3 | Crutches |

| 13 | Stroke | left | 5 | 52 | 171 | 69 | M | 3 | Wheelchair |

| 14 | Stroke | right | 10 | 34 | 160 | 55 | F | 4 | Walking stick |

| 15 | Stroke | right | 14 | 49 | 181 | 90 | M | 5 | Walking stick |

| Mean | 9.2 | 54.3 | 177.7 | 84.8 | 3.5 | ||||

| (SD) | ±11.21 | ±11.97 | ±9.97 | ±16.49 | ±1.46 |

| PID | MMSE (score) |

|---|---|

| 3 | 28/30 |

| 4 | 27/30 |

| 5 | 27/29 |

| 6 | 27/30 |

| 7 | 26/30 |

| 9 | 27/28 |

| 10 | 28/30 |

| 13 | 24/30 |

| 14 | 28/30 |

| 15 | 27/30 |

| Abbreviations: MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination; PID = Patient Identification Number. | |

| PID | GF Left / Right (%) |

Walking speed (km/h) |

BWS (%) |

Immersive VR session duration (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90/90 | 1.50 | 30 | 32 |

| 2 | 80/80 | 1.70 | 40 | 22 |

| 3 | 100/100 | 1.70 | 44 | 27 |

| 4 | 100/100 | 1.30 | 45 | 10 |

| 5 | 100/100 | 1.50 | 43 | 23 |

| 6 | 100/100 | 1.30 | 50 | 16 |

| 7 | 100/100 | 1.20 | 50 | 13 |

| 8 | 80/80 | 1.60 | 30 | 20 |

| 9 | 100/100 | 1.40 | 49 | 11 |

| 10 | 100/100 | 1.50 | 48 | 20 |

| 11 | 100/100 | 1.60 | 28 | 18 |

| 12 | 90/90 | 1.70 | 45 | 31 |

| 13 | 100/100 | 1.20 | 49 | 19 |

| 14 | 100/100 | 1.20 | 50 | 28 |

| 15 | 100/100 | 1.30 | 49 | 23 |

| Mean | 96 | 1.4 | 43.3 | 20.9 |

| (SD) | ±7.37 | ±0.19 | ±7.83 | ±6.76 |

| N. of question | Median | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 4.3±0.45 |

| 2 | 5 | 4.3±0.98 |

| 3 | 2 | 2.0±0.95 |

| 4 | 4 | 4.3±0.49 |

| 5 | 4 | 4.1±0.79 |

| 6 | 5 | 4.6±0.67 |

| 7 | 2 | 2.3±1.30 |

| 8 | 5 | 4.3±0.87 |

| 9 | 5 | 4.3±0.98 |

| 10 | 4 | 4.3±0.75 |

| 11 | 5 | 4.3±0.97 |

| 12 | 4 | 3.7±1.15 |

| 13 | 5 | 4.7±0.65 |

| 14 | 5 | 4.4±1.00 |

| 15 | 1 | 1.5±1.17 |

| 16 | 5 | 4.7±0.65 |

| 17 | 1 | 1.4±0.90 |

| 18 | 4 | 3.1±1.51 |

| Abbreviations: N = number; SD = standard deviation. | ||

| Therapists | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N. of Question | 1 | 2 | 3 | Median | Mean (SD) |

| 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3.25±1.71 |

| 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4.25±1.50 |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3±0.82 |

| 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3.25±0.96 |

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4±0.82 |

| 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4.75±0.96 |

| 7 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4.5±2.08 |

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4.75±2.36 |

| 9 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5.25±2.63 |

| 10 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6±2.71 |

| 11 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6.25±3.20 |

| Abbreviations: N = number ; SD = standard deviation. | |||||

| Q19 - What did you like or dislike about the virtual environment you walked in? |

|

- “I like the environment, nature, which relaxes” - “nature is ok, lady is awful, dog is nice” - “it felt positive” - “after we explain what to do in the VR, it made sense to the patient and he liked it (observation)” - the patient liked the dog barking (observation) - “the walk, nature, mountains” - “nice scene”; the patient fully trusts the designers of the VR in the sense to create the VR what is best for the treatment/training |

| Q20 - Which companion do you prefer to walk with, animal or human, and why? |

|

- half of the patients choose the animal - three patients vote for both companions - one would choose walking with lady - one would choose animal, because lady was not pretty because of the low graphic resolution |

| Q21 - Was there something that you would have liked to do in the virtual environment that wasn't possible? |

|

- “I would like to enter the buildings (lighthouse, tent), where there could be some additional tasks to do“ - “to go uphill to mountain hiking” - “I would like to swim at the end” - “there could be some walking obstacles in the walking path” - “I would like to gather mushrooms” - “I would like to see the birds, since they are tweeting” |

| Q22 - Do you have any good ideas for something you would like to do in a virtual reality when in the Lokomat? |

|

- “I would like to have more activities, e.g. birds or other animals beside batteries” - “jump into the water at the end of the walking path” - “there could be two variants of batteries: those, which gives you power (green batteries) and those, which decrease power (red batteries)” - “I would like to open the box, which can be done by using virtual hands mode in VR; by the end of training I felt a bit bored due to the same type of game (just collecting the batteries)” - “I get bored because it’s always the same game” - “I would like to throw the bone for the dog” - “the game could be gradually more challenging” - “are the batteries always on the same locations?” (yes) - “the batteries could appear when being in a predefined radius, because at the current state of the VR, the very distant batteries are hard to collect and the patient is trying to collect them” - “the counter for batteries could be added” - “batteries are not really in the context of nature - consider replacing batteries with something that suits in nature, e.g. mushrooms or similar natural objects” - “I would like more people or animals walking around in the park and they would not be necessary the walking companions” - “I would be satisfied if there could be more things to do in VR” - “I was really satisfied with the VR and with the operation with the HMD” - “I would like to recommend the system to other patients that have regular Lokomat sessions, because it is more challenging, motivational and beneficial for the rehabilitation” |

| Q12 - Please note 3 things you liked about using the Lokomat together with a VR headset |

|

- simple to use - the reality of the environment was sufficient - time flies for the patients with its use - the whole installation is fairly easy to use - the patients had more motivation for training - especially those, who had several Lokomat trainings before participation - patients were able to have longer trainings, which was seen on quite a few cases - I liked the advanced type of training with double tasking – walking and attention to the surroundings - this type of training arouses the patient's interest and increases his participation |

| Q13 - Please note 3 things about using the Lokomat together with a VR headset you would like to change |

|

- would like to add more challenges during walking - to control the direction of walking according to the step length - possible more different environments, not just one scene, so that the patients could not be bored of walking in a single scene all the time - to change directions with legs' performance - the system could be easier to use from the technological point of view, especially software in the HMD - the beneficial function of the Loko-VR training for the rehabilitaion process would be the possibility to train particular walking features (swing phase, stance phase, gait symmetry, etc.) - it could be more easier to access to the VR application in the HMD - the HMD might be combined with the safety system in the case if the HMD falls from the patient's head - however, there was no such case, but if the HMD would somehow fall to the treadmill, it could present an obstacle on the walking path |

| Abbreviations: Q = question; VR = Virtual Reality. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).