1. Introduction

Innovative technologies, such as augmented reality applications, are undergoing remarkable development and integration into various aspects of daily life. These technologies—including virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR)—offer novel ways of interacting with digital content and enhancing user experiences across a wide range of applications. Their implementation has the potential to fundamentally transform how people perceive and process information. Increasingly adopted by individuals of all ages and social backgrounds, these technologies have become integral to diverse communities (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2019). Applications range from strategy and simulation games to cognitive and entertainment tools.

One prominent subset of these technologies is serious games—computer-based programs designed to impart knowledge and skills are engagingly and entertainingly (Gentry et al., 2019). Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of serious games in boosting user motivation and engagement while fostering significant improvements in acquired skills. For instance, Benham et al. (2019) found that immersive VR interventions can alleviate pain and enhance the quality of life for older adults. Additionally, gamification has emerged as a complementary strategy to increase engagement in non-game contexts. By incorporating game-like elements such as points, leaderboards, and rewards into applications, gamification motivates users to adopt specific behaviors or achieve learning goals (Capterra, n.d.). While gamification enhances existing activities with playful incentives, serious games focus on standalone games with clearly defined educational objectives. Together, these developments highlight the transformative potential of serious games and gamification as innovative tools for knowledge transfer and skill development, fostering active engagement with complex topics.

In the realm of virtual reality (VR), serious games are increasingly being employed to deliver content in both knowledge-based and immersive ways. In gerontology, these technologies are being utilized to support older adults in various areas of life. Virtual applications have been applied in memory work, movement therapy, pain management, relaxation techniques, and the promotion of everyday activities known as Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) (Napetschnig et al., 2023). Training in virtual environments offers senior citizens opportunities to maintain or even improve their abilities. Research has shown significant positive effects of serious games on the cognitive and motor skills of older adults. For example, Kustanovich et al. (2023) demonstrated that serious games significantly improved memory and cognitive functions in seniors with dementia over a ten-week period. Through targeted exercises within a playful environment, participants not only trained their cognitive abilities but also preserved their everyday skills.

Similarly, Anderson-Hanley et al. (2012) provided evidence that serious games used in motor rehabilitation positively impact balance and coordination among older adults. Movement-based games—commonly referred to as exergames—not only promote physical fitness but also enhance user engagement and motivation. Bégel et al. (2017) further suggested that exergames training rhythmic abilities could serve as effective tools for rehabilitating motor and cognitive functions in individuals with conditions such as Parkinson's disease, dyslexia, or ADHD. These games enable seniors to remain active while enjoying exercise-based activities.

Moreover, an exploratory pilot study conducted as part of the "SenseCity" project by Joanneum Research Digital in Austria examined the impact of VR applications on the quality of life among older adults. Participants reported positive emotions and memories evoked by virtual experiences such as visiting a park or taking a gondola ride through Venice. These virtual experiences not only foster social interaction but also contribute to emotional stability (Health&Care Management, n.d.).

The use of serious games and VR technologies thus presents promising approaches for supporting older adults in their daily lives. These technologies can help enhance cognitive and motor skills while significantly improving overall well-being and quality of life for senior citizens. Given demographic changes and the growing proportion of older adults worldwide, it is essential to develop innovative solutions tailored to the specific needs of this population group.

In summary, VR technologies and serious games represent effective tools for promoting independence among older adults while helping them maintain or improve their daily living skills. Future research should prioritize further development of these technologies while evaluating their potential applications across diverse contexts.

2. Method

2.1. Field of Application

The findings outlined above emphasize the importance of virtual reality (VR) in training everyday activities. One such activity, crossing a road, serves as the central use case for this study. This use case is grounded in concerning statistics: In Germany, the incidence of road traffic accidents among senior citizens increases with age. According to statistical data, 12% of those injured and 29% of those killed in traffic accidents were aged 65 or older (Federal Statistical Office, 2020). The consequences of such accidents are often more severe for older adults compared to younger road users due to their reduced physical resilience (Lukas, 2018).

Crossing a road safely presents a significant challenge for many older adults. From the age of 75 onwards, the risk of accidents during road crossing increases substantially, with incorrect behavior frequently identified as the primary cause (Federal Statistical Office, 2021; Federal Statistical Office, 2023). Age-related changes in motor skills, cognitive function, and visual acuity exacerbate these difficulties. Motor impairments often manifest as reduced walking speed and difficulties adapting to varying situations (Tian et al., 2022; Soares et al., 2021; Maki & McIlroy, 2007). Additional motor changes include shorter stride lengths and compensatory movements stemming from balance disorders (Tapiro et al., 2020). Furthermore, postural control becomes increasingly vulnerable to disruptions with age, while gait and posture planning are impaired (Tian et al., 2022; Soares et al., 2021). These motor deficits are particularly problematic when navigating roads with high vehicle speeds.

2.2. Development of VR Application "Wegfest"

To address these challenges, a VR training application called "Wegfest" was developed to teach safe road-crossing techniques. This application uses various virtual road scenarios to help senior citizens learn how to cross streets while considering multiple factors. The development process utilized the Unity Engine and was carried out by the vobe GbR team using C# programming language. The modeling phase involved designing individual scenes featuring diverse environments and objects.

To create a realistic virtual environment, street scenarios from German cities—including Cologne, Bochum, Münster, and Düsseldorf—were selected as templates for development. These street situations were captured using Google Maps and subsequently implemented into Unity (see

Figure 1 ff.). The virtual environments aim to replicate real-world conditions as closely as possible to ensure effective training outcomes.

Figure 1.

Screenshot Google Maps, crossing situation traffic island in Düsseldorf (Google, 2009).

Figure 1.

Screenshot Google Maps, crossing situation traffic island in Düsseldorf (Google, 2009).

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Google Street View Maps, crossing situation traffic island in Düsseldorf on Person View (Google, 2009).

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Google Street View Maps, crossing situation traffic island in Düsseldorf on Person View (Google, 2009).

Figure 3.

Screenshot of scene Wegfest, crossing situation traffic island based on Google Street View Maps (own illustration).

Figure 3.

Screenshot of scene Wegfest, crossing situation traffic island based on Google Street View Maps (own illustration).

The scene design incorporates paid assets, including animated characters capable of performing interactions such as walking and gesturing.

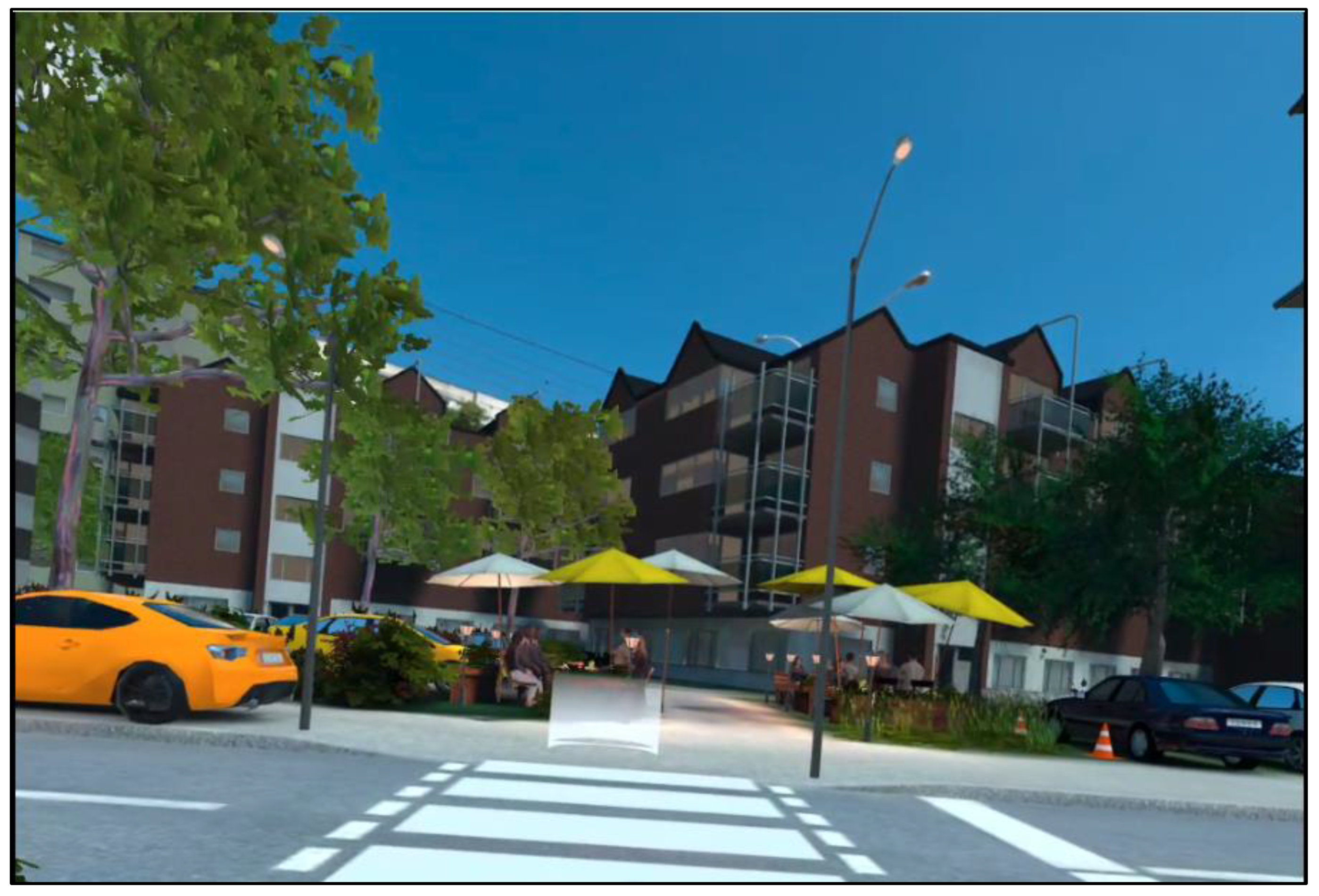

Figure 4 presents a screenshot of a daytime scene from "Wegfest," highlighting the integration of these dynamic elements into the virtual environment. These assets contribute to creating a realistic and immersive experience for users.

Figure 4.

Daytime scene at the Wegfest (own illustration).

Figure 4.

Daytime scene at the Wegfest (own illustration).

The Meta Quest 2 head-mounted display (HMD) was utilized for this project. Interactions in virtual reality (VR) were conducted by physically walking and gesturing, supported by hand-tracking technology. Continuous pre-tests, carried out by programmers and senior staff, facilitated iterative adjustments during the application development process. Beginning in July 2022, the existing version of "Wegfest" was tested with a sample of n=8 older adults. Participants were recruited through personal networks and the Bischoff Physiotherapy Practice in Düsseldorf. After each pre-test phase, feedback from participants was collected and integrated into the application design. Following the fourth pre-test with older adults, the application was deemed acceptable by users, enabling its prototype to be used for the subsequent intervention study.

Before starting their first training session, users completed an integrated tutorial within "Wegfest." This tutorial was designed to familiarize them with interaction patterns and navigation in the virtual environment. It allowed participants to individually explore various movement sequences and helped them acclimate to VR, a new medium for many senior citizens. The tutorial explained the functions of the application, outlined required interactions, and assessed their applicability. In addition to serving as a tool for onboarding participants, it also evaluated their experience of wearing the VR headset while physically walking. Once participants successfully completed the tutorial, the first scene of a predefined iteration was loaded. An iteration consisted of multiple consecutive street-crossing scenarios defined via a web application.

The web application comprised a front end, back end, and database that organized structured information electronically. An Internet connection was required for data transfer. The modular structure of various scenes enabled diverse applications for road-crossing training in VR environments.

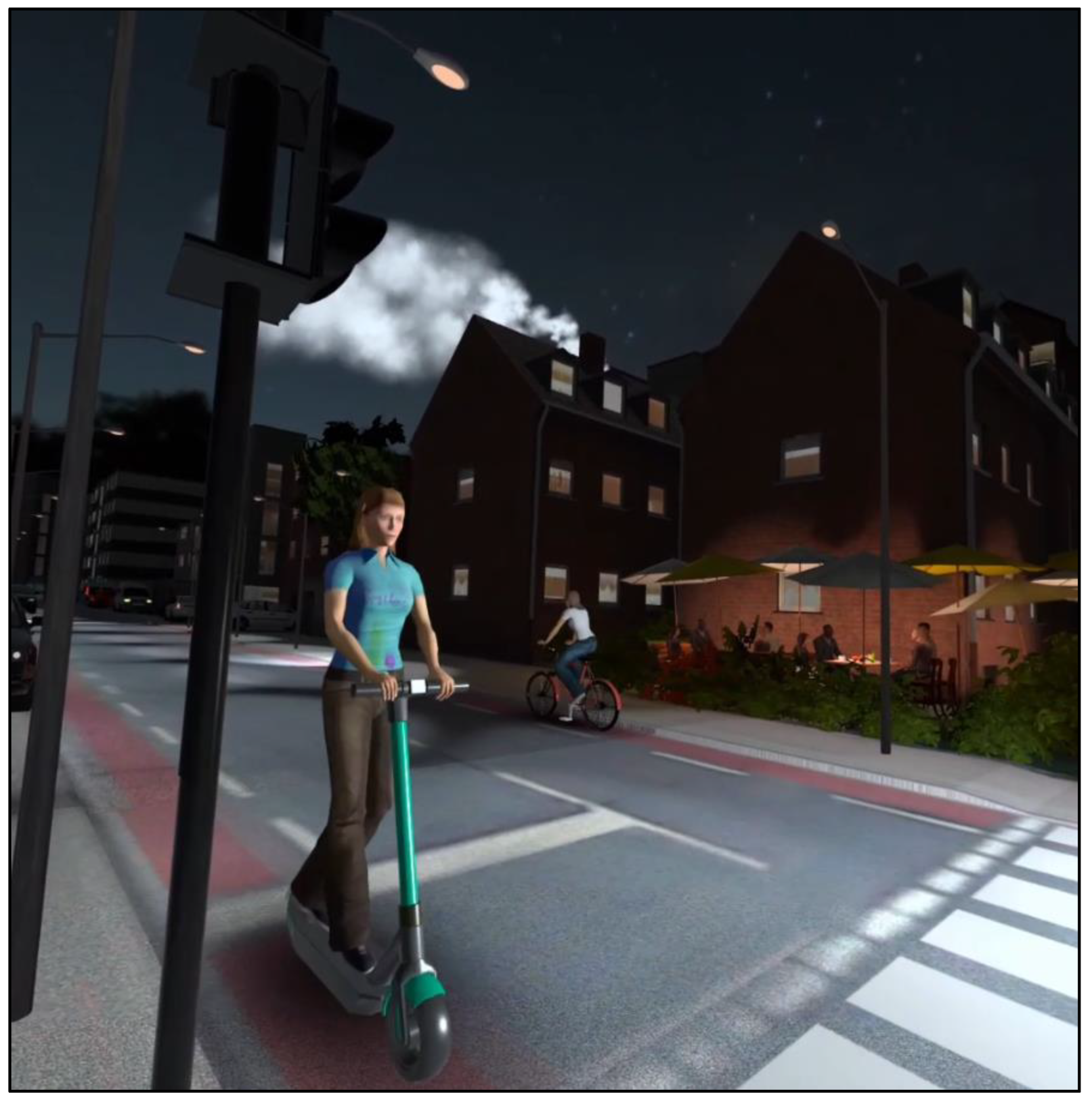

The scenes incorporated various vehicle models, including motorized and non-motorized vehicles. Modeling based on specific distance calculations—such as Region of Warning (ROW) and Region of Interest (ROI)—was employed to prevent virtual collisions and ensure user safety. A white circle on the opposite side of the curb acted as a target marker for participants. Scene parameters were configured to reflect real-world conditions during road crossings and included acoustic and visual stimuli. Acoustic inputs featured vehicle sounds (e.g., electric or motorized vehicles) as well as ambient noises such as voices or music. Visual inputs included varying crossing distances (e.g., lane width), crossing aids (e.g., traffic lights, crosswalks, traffic islands), and different times of day (e.g., daytime, twilight, night).

Figure 5 displays a screenshot from "Wegfest," showcasing an e-scooter or bicycle within a nighttime scene.

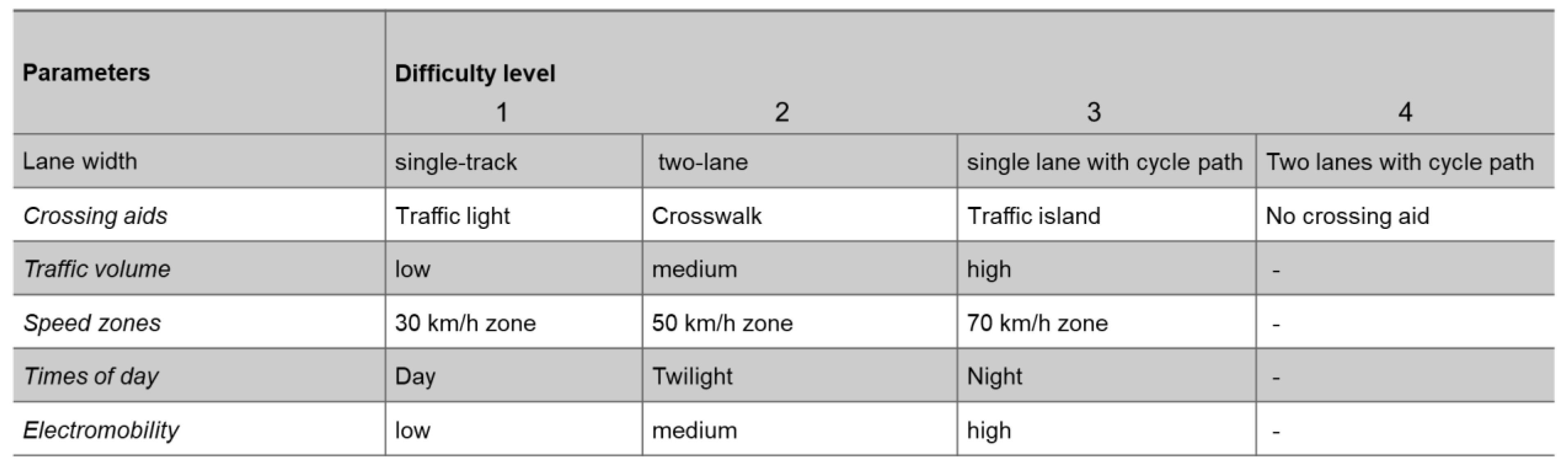

The selection of scenes for each iteration is guided by specific parameters. To ensure an adaptive progression in training, the requirements and level of difficulty in individual training units are systematically increased. The configuration of scenes within each iteration is determined based on these parameters. Comprehensive research is conducted to evaluate the relevance of individual parameters as influencing factors in road-crossing scenarios. This evaluation enables parameter weighting and serves as the foundation for variability in training design.

The training framework is structured around a value system in which scenes are configured by selecting parameters with corresponding difficulty gradations (e.g., 1 = easy; 3 or 4 = difficult) (see

Table 1). Progression to a scene with a higher challenge level occurs only after the user successfully completes a road-crossing attempt that is both accident-free and safe.

Table 1 provides an overview of the various parameters used to configure scenes in the VR application "Wegfest." By summing the values assigned to each parameter, a total score is calculated, which represents the difficulty level of the respective scene.

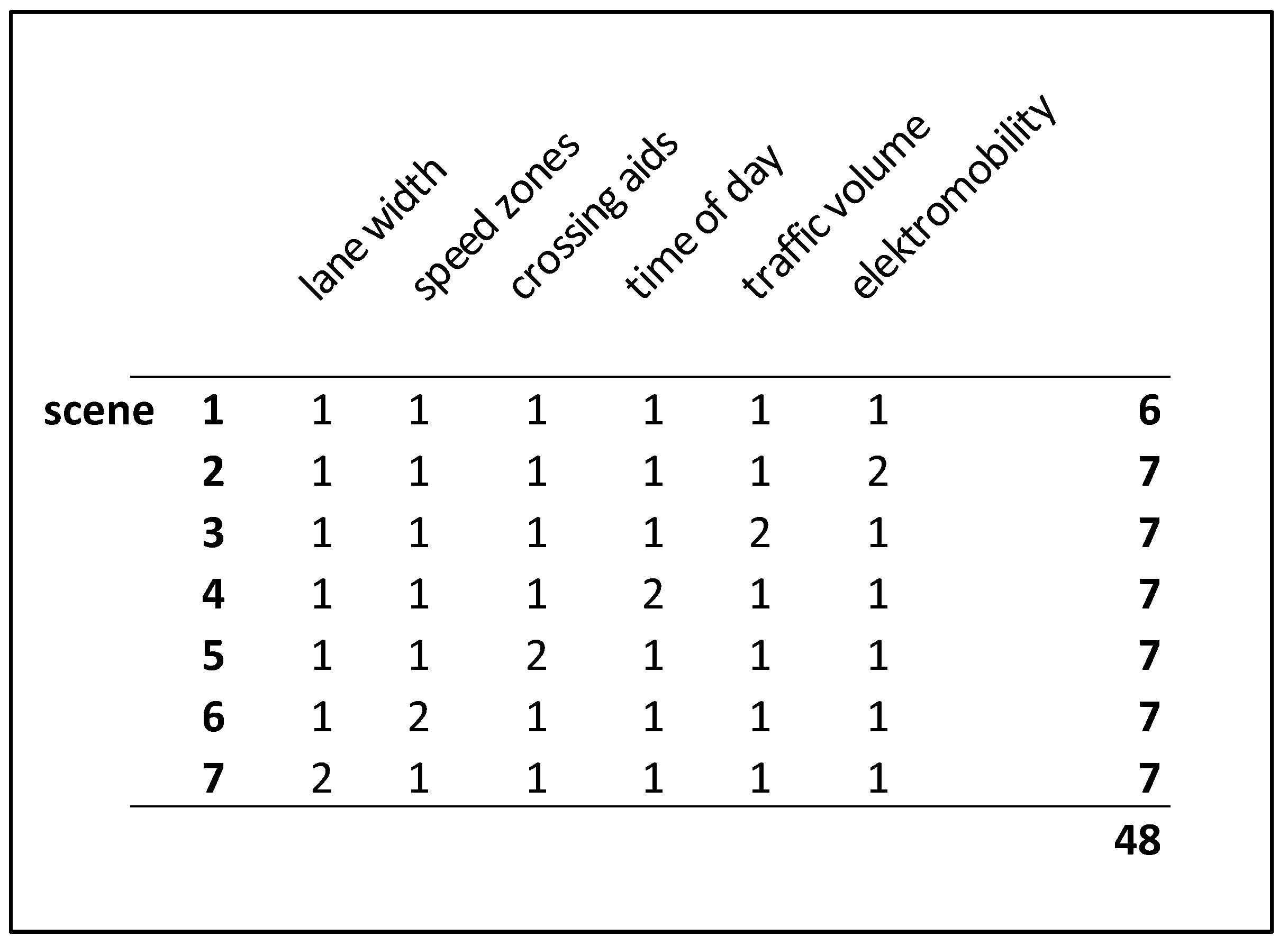

Table 2 presents an example of a training session consisting of seven distinct scenes with varying levels of difficulty; the cumulative sum of the parameters for this session is 48.

2.3. Research Design and Participants

To examine the effects of the VR application "Wegfest" on the physical and psychological parameters of senior citizens, an intervention study was conducted. The primary aim was to evaluate the impact of VR training designed to simulate various scenarios for crossing roads safely. The sample size was determined using a G*Power analysis, assuming a large effect size (dz=0.8), a significance level (α=0.05), and a test power (1−β=0.95). Of the n=29 recruited participants, n=20 were included in the final analysis.

Participants were selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria required individuals to be aged 70 years or older, without a fall risk, living independently, and physically fit. Exclusion criteria included contraindications for VR use (e.g., epilepsy, vertigo), severely limited walking ability, significant balance issues, cognitive impairments, bedridden status, severe cardiovascular diseases, use of mobility aids (e.g., walker or cane), severe visual impairments or eye diseases, and significant hearing loss. These criteria ensured participant safety and study validity. The participants ranged in age from 71 to 81 years (mean age: 74.95±3.17 years). Of the participants, n=12 were male and n=8 female; all were individually assessed for health suitability before participation.

2.4. Assessments

Prior to the VR intervention, several assessments were conducted to ensure the physical and mental suitability of participants:

Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test: This test evaluated mobility and fall risk by assessing functional performance in older adults, focusing on flexibility and balance (Podsiadlo & Richardson, 1991). A cut-off value of <20 seconds indicated unrestricted mobility in daily activities. The TUG demonstrated excellent reliability (interrater reliability: ICC = 0.99; intrarater reliability) and strong validity correlations with established measures such as the Berg Balance Scale (r=−0.81), Barthel Index of ADL (r=−0.78), and gait speed (r=−0.61) (Schleuter & Röhrig, 2008).

Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I): The FES-I assessed fall-related self-efficacy using a 16-item questionnaire that evaluated complex functional activities and social aspects of self-efficacy (Dias et al., 2006). This instrument demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.96) and excellent test-retest reliability (r=0.96).

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): The MoCA screened for cognitive deficits across domains such as memory, executive functions, attention, and visuospatial skills. It was particularly relevant for evaluating cognitive abilities required for VR use in "Wegfest" scenarios (Nicholls et al., 2022). A cut-off score >26 points indicated normal cognitive function. The MoCA showed strong psychometric properties with reliability (r=0.89) and sensitivity (80%) at this threshold (Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2018).

Additional questionnaires assessed VR suitability and participants' subjective perceptions of safety when crossing roads in virtual environments.

2.5. Intervention Process

The intervention took place between October and December 2022, with participant recruitment beginning on August 15, 2022. Recruitment involved distributing information sheets at Bischoff Physiotherapy Practice, RKM 740 Physiotherapy Facility in Düsseldorf, senior centers in Bochum (in collaboration with NRW Police), and personal networks in Düsseldorf and Cologne.

The intervention consisted of eight training sessions over three months, conducted twice weekly for 20–30 minutes per session. During these sessions, participants practiced crossing roads under various conditions in VR scenarios that gradually increased in complexity. Participants were individually supervised throughout the sessions to monitor their reactions closely and allow for immediate intervention if necessary.

The study received ethical approval from the German Sport University Cologne. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 and Microsoft Excel. Ethical standards were upheld through written informed consent and data protection agreements.

The drop-out rate was 31.03%. Reasons for exclusion included a TUG value exceeding the cut-off threshold (>23 seconds), motion sickness experienced by two participants who discontinued training prematurely, and irregular attendance (<75% of sessions) by six participants.

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Results

The evaluation of the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test data indicated a normal distribution for both measurement time points; therefore, a paired t-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used for analysis. The t-test revealed a significant difference between the measurement time points (p = 0.002), with a Cohen's d value of 0.784, indicating a large effect size. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) results showed no significant difference (p = 0.56), suggesting no change in the subjects' cognitive abilities.

A significant result was obtained for the Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I) (p = 0.005, z = -2.818), indicating an improvement in self-efficacy regarding fear of falling. These results support the effectiveness of the VR intervention in terms of functional performance and fall prevention.

The subjective assessment of the participants was evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test at the ordinal scale level. The analysis showed a significant change between the pre-assessment and the post-assessment (p < 0.001, z = 7.157). The participants reported a significant improvement in their subjective perception of their own safety when crossing the road after completing the VR intervention.

3. Summary of the Results

The results of the study indicate significant positive effects of the VR intervention, both in objective performance parameters (TUG and FES-I) and in the subjective perception of the participants. The improvement in the subjects' self-efficacy and subjective safety supports the assumption that VR-based training programs can positively influence the functional performance and sense of safety of senior citizens.

4. Discussion

The VR application "Wegfest" has selected road crossing as a central use case because this everyday activity is of great importance for senior citizens. Statistics show that older adults are frequently involved in accidents due to improper road crossing (Federal Statistical Office, 2021). The causes of this increased risk are multifaceted and include age-related changes in cognition, vision, and motor skills (Tian et al., 2022; Dommes, 2015). This issue is also addressed in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which covers various aspects of walking and locomotion (BfArM, 2021). Although there has been a slight decline in traffic accidents among senior citizens in recent years, this is attributable to several factors. For example, isolation and reduced mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic led to fewer accidents (Welzel et al., 2021). Increased road safety measures, such as more frequent speed cameras and speed limits, have also contributed to a reduction in the number of accidents (Glas, 2021; ADFC, 2020). Nevertheless, road safety for senior citizens remains a key concern, especially given demographic changes and the aging population (Maresova et al., 2023).

The development of the VR application "Wegfest" raises several important points for discussion. First, there is the question of the effectiveness of such VR training programs compared to traditional training methods. Studies have shown that VR training can have a positive impact on the cognitive and motor skills of older adults. For example, Benham et al. (2019) reported that immersive VR interventions not only improve physical well-being but can also boost participants' self-confidence. Another aspect is the adaptability of the VR application to individual needs. The ability to simulate different scenarios—such as crossing a road in different lighting or traffic conditions—could enable seniors to train specific challenges and improve their skills in a targeted manner (Napetschnig et al., 2023). This could not only increase road safety but also promote general self-confidence in dealing with everyday situations. Additionally, it is important to consider how realistic the VR representations are and how they influence the user's perception. Benoit et al. (2015) emphasized the influence of VR design on users' sense of presence. A high degree of realism could help senior citizens to better prepare for real-life situations. However, there is also a risk that excessive familiarity with the virtual environment could lead to an overestimation of their abilities in real life. Another point of discussion concerns the accessibility and acceptance of VR technologies among older adults. Many seniors may be unfamiliar with modern technology or have difficulty operating VR devices (Gulchak, 2008). Therefore, it is crucial to develop training programs that facilitate the use of VR applications while addressing concerns about possible side effects such as kinetosis (Dey et al., 2018). Thus, it can be said that the use of virtual reality to improve road safety for seniors offers promising approaches. However, further research and discussions are needed on design criteria and on the integration of such technologies into existing programs to support older adults. The results of these discussions could help to create guidelines for the development of effective and user-friendly VR applications.

This presentation on the development of VR applications in connection with safe road crossing emphasizes the growing relevance of virtual reality in the area of "healthy aging." Serious games, in particular, offer innovative approaches to support older adults in their daily mobility. The integration of playful elements into serious learning content not only promotes user engagement but also improves learning success through immersive experiences. The relevance of these technologies is underpinned by empirical studies. The results suggest that VR interventions can not only provide therapeutic benefits—such as reducing pain sensations or improving cognitive abilities—but also have a positive impact on psychosocial aspects. This is particularly important for older adults, whose quality of life is often impaired by physical limitations or psychological stress. In addition, the literature shows a clear link between motor changes in old age and the increased risk of road traffic accidents. Crossing roads safely requires not only physical skills such as speed and coordination but also cognitive processes such as decision-making and risk assessment. It is therefore crucial that future research continues to focus on the development of effective VR training programs to specifically promote these skills. It remains uncertain to what extent VR training actually leads to improved performance in crossing streets or reduces the risk of accidents. Further research is necessary to confirm these significant findings in a representative manner.

Overall, it appears that virtual reality is a promising tool for supporting older adults in their mobility and increasing their safety on the road. Through targeted training programs in virtual environments, seniors can not only improve their skills but also strengthen their self-confidence and thus increase their quality of life.

In summary, it can be said that virtual reality is a promising tool for improving the safety of older people in road traffic. Innovative training approaches can be used not only to train motor skills but also to promote self-confidence and reduce fear of mobility restrictions in old age.

5. Conclusions

The increasing integration of virtual reality (VR) technologies into healthcare opens up numerous innovative approaches to improving the quality of life of older adults. These technologies offer opportunities not only for cognitive stimulation but also for promoting emotional well-being and social interaction. The VR application "Wegfest" exemplifies how such technologies can be used in a targeted manner to address specific challenges in the everyday lives of senior citizens.

Studies show that VR applications can have significant positive effects on cognitive function and balance in older people. A study by Appel et al. (2020) found that immersive VR experiences can improve the subjective well-being and cognitive performance of seniors with mild cognitive impairment. These findings highlight the potential of VR as a therapeutic tool that not only promotes cognitive stimulation but also enhances emotional well-being by enabling users to activate positive memories and promote social interactions (RemmyVR, n.d.). In addition, a study by Jon Ram Bruun-Pedersen et al. (2016) has shown that VR technologies can motivate residents of care facilities to exercise more. This is particularly important as physical activity has been shown to reduce the risk of falls and improve the general health of older people. The combination of exercise and VR can therefore be an effective strategy to promote both physical and mental health.

Another key aspect of the use of VR by senior citizens is the improvement of social interaction. According to Tabbaa et al. (2019), VR applications can help older people communicate about their experiences and actively participate in social activities. This is particularly relevant in times of social isolation, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ability to take virtual trips or participate in interactive group activities can help reduce loneliness and increase a sense of belonging (Lai et al., 2023).

Despite the promising benefits, there are also challenges and ethical considerations associated with the use of VR technologies in older people. It is important to ensure that these technologies are not only effective but also used safely and ethically (Bruno et al., 2022). McCarthy et al. (2021) emphasized the need for responsible use of data and protection of user privacy. In addition, potential risks such as nausea or disorientation should be considered when using VR (Gulchak et al., 2018).

6. Outlook

In summary, it can be said that virtual reality technologies offer promising approaches for improving health behavior and promoting quality of life among senior citizens. The "Wegfest" application demonstrates how innovative technologies can be used specifically to support older adults. Future research activities should focus on how different parameters of VR training can influence real-life situations and which evidence-based forms of care can be developed. In addition, it is crucial to promote interdisciplinary exchange between healthcare, psychology, and computer science professionals to ensure the development of effective and user-friendly VR applications. Continuous evaluation of the effectiveness of such applications in real-life settings will also be necessary to fully understand their benefits for different target groups.

Another important aspect is the need for an interdisciplinary approach to the development of VR applications for senior citizens. Collaboration between computer scientists, psychologists, and gerontologists can help to consider both technical and human factors. For example, a psychological perspective could help to understand how older adults interact with new technologies and what barriers they may need to overcome (Fischer et al., 2019). In addition, training in the use of VR technologies should be part of the implementation process. Studies show that training programs can increase confidence in the use of technologies and thus also promote acceptance (Gulchak et al., 2018). This could be particularly important for senior citizens who may have less experience with digital media. In conclusion, virtual reality offers promising potential for improving health behavior and promoting mobility among older people. The "Wegfest" application represents an innovative approach to tackling specific challenges in the everyday lives of senior citizens. Future research activities should not only focus on the effectiveness of such applications but also investigate their acceptance and integration into existing care structures.

References

- Aguilar-Navarro, S. G., Mimenza-Alvarado, A. J., Palacios-García, A. A., Samudio-Cruz, A., Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. A., & Ávila-Funes, J. A. (2018). Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for the Detection of Cognitive Impairment in Mexico. Validez y confiabilidad del MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) para el tamizaje del deterioro cognoscitivo en méxico. Revista Co-lombiana de psiquiatria (English ed.), 47(4), 237–243. [CrossRef]

- Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club [ADFC] (2020). Promotion of municipal cycling infrastructure. Accessed on 29.11.2024 at https://www.adfc.de/artikel/foerderung-kommunaler-radverkehrsinfrastruktur.

- Anderson-Hanley, C. , Arciero, P. J., Brickman, A. M., Nimon, J. P., & Heller, W. (2012). The effectiveness of serious games for improving balance and coordination in older adults: A pilot study. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation,. [CrossRef]

- Appel, L. , Appel, E., Bogler, O., Wiseman, M., Cohen, L., Ein, N.,... & Campos, J. L. (2020). Older adults with cognitive and/or physical impairments can benefit from immersive virtual reality experiences: A feasibility study. Frontiers in Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Bégel, V., Di Loreto, I., Seilles, A., & Dalla Bella, S. (2017). Music Games: Potential Application and Considerations for Rhythmic Training. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 11, 273. [CrossRef]

- Benham, T., Smith, R., & Jones, L. (2019). The effectiveness of immersive virtual reality interventions for pain management in older adults: A systematic review. Pain Management Nursing, 20(5), 479-487.

- Benham, T., Smith, R., & Jones, L. (2019). The effectiveness of immersive virtual reality interventions for pain management in older adults: A systematic review. Pain Management Nursing, 20(5), 479-487.

- Benoit, M. , Guerchouche, R., Petit, P. D., Chapoulie, E., Manera, V., Chaurasia, G. et al. (2015). Is it possible to use highly realistic virtual reality in the elderly? A feasibility study with image-based rendering. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R. R. , Wolff, G., Wernly, B., Masyuk, M., Piayda, K., Leaver, S., Erkens, R., Oehler, D., Afzal, S., Heidari, H., Kelm, M., & Jung, C. (2022). Virtual and augmented reality in critical care medicine: the patient's, clinician's, and researcher's perspective. Critical care (London, England). [CrossRef]

- Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Health (BMG) with the participation of the ICD Working Group of the Board of Trustees for Questions of Classification in Health Care (KKG), (2021). ICD-10-GM Version 2021, Systematic Index, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, as of September 18, 2020. Accessed on 25.11.2024 at https://www.dimdi.de/static/de/klassifikationen/icf/icfhtml2005/.

- Capterra. (n.d.). Gamification vs. games-based learning: What's the difference? https://www.capterra.com/resources/gamification-vs-games-based-learning/.

- Dey, A. , et al. (2018). Privacy concerns and data protection in augmented reality applications for older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 30(3), 233-250.

- Dias, N. , Kempen, G. I., Todd, C. J., Beyer, N., Freiberger, E., Piot-Ziegler, C., et al. (2006). Die Deutsche Version der Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I) [The Ger-man version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version (FES-I)]. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 39(4), 297–300. [CrossRef]

- Dommes, A. , Lay, T. L., Vienne, F., Dang, N. T., Beaudoin, A. P., & Do, M. C. (2015). Towards an explanation of age-related difficulties in crossing a two-way street. Accident; analysis and prevention. [CrossRef]

- Dommes, A., V. Cavallo, V., Dubuisson, J.-B., Tournier, I. & Vienne, F. (2014). Crossing a two-way street: comparison of young and old pedestrians. Journal of Safety Research, 50 (2014), 27-34.

- Fischer, J., et al. (2019). Understanding technology acceptance among older adults: A systematic review of the literature. Gerontechnology, 18(4), 247-258.

- Gentry, S.V., Barata, G., & L'Ecuyer-Mailloux , J.(2019). Serious games for health: A systematic review on their effectiveness in promoting health behaviors among older adults.Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(3), e12345.

- Glass, O. (2021). Fewer traffic fatalities in the Corona year 2020. Accessed on 20.11.2024 at https://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/ungluecke/weniger-verkehrstote-im-corona-jahr-2020-17426713.html.

- Gulchak, S., et al. (2018). The challenges of technology adoption among older adults: A review of the literature. Gerontechnology, 17(3), 177-182.

- Health&Care Management. (n.d.). Positive emotions and virtual experiences: Enhancing social interaction and emotional stability in older adults. https://www.healthcaremanagement.com/positive-emotions-virtual-experiences.

- Joanneum Research. (n.d.). SenseCity: Virtual mindfulness training and imagination for people with dementia. https://www.fh-joanneum.at/projekt/sensecity/.

- Jon Ram Bruun-Pedersen et al (2016). Virtual reality technologies motivate nursing home residents to exercise more: An investigation.

- Kustanovich, M., Posmyk, A., Didczuneit-Sandhop, B., Beck, E., & Orlowski, K. (2023). Serious games for seniors - Influence on the cognitive abilities of seniors with dementia over a period of ten weeks. In Proceedings of the NWK 2023. https://www.hs-harz.de/dokumente/extern/Forschung/NWK2023/Beitraege/Serious_Games_fuer_SeniorInnen_-_Einfluss_auf_die_kognitiven_Faehigkeiten.pdf.

- Lukas, A. (2018). Older drivers: danger or vulnerable? Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2018; 143(11): 778-782. [CrossRef]

- Maki , B.E ., & McIlroy , W.E .(2007). Control of rapid limb movements for balance recovery: Insights from postural control research.Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 31(4), 556-567.

- Maresova, P. , Krejcar, O., Maskuriy, R., Bakar, N. A. A., Selamat, A., Truhlarova, Z., Horak, J., Joukl, M., & Vítkova, L. (2023). Challenges and opportunity in mobility among older adults - key determinant identification. BMC geriatrics. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J., et al (2021). Ethical considerations for the use of virtual reality in healthcare: A systematic review and recommendations for practice. Journal of Medical Ethics, 47(4), 241-246.

- Napetschnig, A. (2024). User-oriented design and evaluation of virtual reality applications for senior citizens, taking into account acceptance criteria and barriers to use. Doctoral thesis. Cologne: German Sport University Cologne. [CrossRef]

- Napetschnig, A. , Brixius, K. & Deiters, W. (2023). Development of virtual reality applications suitable for seniors: Proposal for a quality criteria core set [Manuscript accepted for publication in JMIR Interactive Journal of Medical Research]. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, V. I. , Wiener, J. M., Meso, A. I., & Miellet, S. (2022). The Relative Contribution of Executive Functions and Aging on Attentional Control During Road Crossing. Fron-tiers in psychology. [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A. K. , & Weinstein, N. (2019). The impacts of motivational framing of technology restrictions on adolescent concealment: Evidence from a preregistered experimental study. Computers in Human Behavior, 90, 170-180. [CrossRef]

- RemmyVR. (n.d.). Virtual reality for seniors: what the research says - RemmyVR.

- Soares , J.M ., Silva , C ., & Marques , A .(2021). Age-related changes in gait dynamics: Implications for fall risk assessment.Gait & Posture, 84, Article ID 123456.

- Federal Statistical Office - Destatis (2020). Traffic accidents: Accidents involving senior citizens in road traffic 2019. Accessed on 08.12.2024 at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Verkehrsunfaelle/Publikationen/Downloads-Verkehrsunfaelle/unfaelle-Senior*innen-5462409197004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

- Federal Statistical Office - Destatis (2021). Traffic accidents: Accidents involving senior citizens in road traffic 2020. Accessed on 08.12.2024 at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Verkehrsunfaelle/Publikationen/Downloads-Verkehrsunfaelle/unfaelle-senioren-5462409207004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

- Federal Statistical Office - Destatis (2023). Traffic accidents: Accidents involving senior citizens in road traffic 2021. Accessed on 08.12.2024 at https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Verkehrsunfaelle/Publikationen/Downloads-Verkehrsunfaelle/unfaelle-senioren-5462409217004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

- Podsiadlo, D. , & Richardson, S. (1991). The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mo-bility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. [CrossRef]

- Schleuter, S. & Röhrig, A. (2008). Time Get-Up and Go Test/Timed „Up and Go“-Test (TGUG/TUG). Zugriff am 12.11.2021 unter von http://www.assessment-info.de/asses-sment/seiten/datenbank/vollanzeige/vollanzeige-de.asp?vid=370.

- Tabbaa, L. , Ang, C. S., Rose, V., Siriaraya, P., Stewart, I., Jenkins, K. G., & Matsangidou, M. (2019). Bring the outside in: Providing accessible experiences through VR for people with dementia in locked psychiatric hospitals. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(7), e13837. [CrossRef]

- Tapiro, H., Oron-Gilad, T. & Parmet, Y. (2020). Journal of Safety Research. 72, 101-109. [CrossRef]

- Tian , J ., Liu , Y ., & Zhang , Y .(2022). The impact of aging on gait variability: A systematic review.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14, Article ID 123456.

- Welzel, F.D. , Schladitz, K., Förster, F., Löbner, M. & Riedel-Heller, S.G. (2021). Health consequences of social isolation: Qualitative study on psychosocial stress and resources of older people in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Federal Health Journal 64. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).