1. Introduction

For years, the quantitative analysis of human movement has been representing a crucial aspect in rehabilitation domain, providing relevant insights into the mechanisms underlying physical impairments and supporting the definition of therapeutic plans [

1,

2]. In fact, detecting abnormal movement patterns, as well as changes in motor strategies resulting from physical and pharmacologic treatments, is of paramount importance for assessing, treating, and monitoring a wide range of clinical conditions in both neurological and musculoskeletal area [

3,

4,

5].

In this context, evaluating trunk movement with specific focus on the range of motion (ROM) is particularly important, as it provides valuable information on functional deficits and compensatory strategies in people with musculoskeletal disorders, such as low back pain (LBP) [

6,

7]. However, despite its importance, the ease of implementation and overall reliability of trunk ROM assessment remain questionable in both research and clinical settings [

8,

9].

In general, ROM refers to the angular extent of movement a joint can achieve from its starting position to its maximum range in a given direction. In clinical practice, ROM is often quantified using goniometric measurements, allowing to assess trunk mobility and its impact on functional performance [

10]. While goniometers are affordable, portable, and widely used for direct ROM assessments, their overall reliability can be influenced by factors such as the examiner’s expertise, the specific joint being evaluated, and challenges in correctly positioning the device during movement [

11,

12]. To overcome these limitations, more advanced measurement tools have been developed, providing greater reliability in assessing joint ROM. Over time, marker-based optoelectronic motion capture (MoCap) systems have established themselves as the gold standard for quantitative movement analysis.

In general, these MoCap systems rely on cameras and reflective markers palace on specific anatomical landmarks to capture 3D kinematic data, providing reliable and accurate measurements of joint angles, velocities, accelerations, and spatio-temporal parameters [

13]. Although these MoCap systems offer valuable insights into joint function and biomechanical performance, which is crucial for diagnosing and treating movement-related disorders, they present several limitations hinder their widespread adoption. In fact, such systems are expensive, they require a controlled laboratory environment with trained personnel, and involve complex procedures for data acquisition and processing demanding both time and clinical expertise. Additionally, their use in controlled conditions often reduces their ecological validity, thus limiting their applicability in real-world contexts [

14,

15].

In recent years, wearable inertial measurement unit (IMU) have emerged as promising tool for human movement analysis [

16]. These compact and lightweight devices typically embed various tri-axial sensors (i.e., accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers), whose data integration via on-board sensor fusion algorithms enables the direct and real-time estimation of key 3D kinematic parameters [

17]. IMUs offer some advantages over marker-based MoCap systems, such as portability, ease of use, and the ability to measure movements in real-world environments [

18]. However, they do have several limitations, including potential calibration errors and need for complex algorithmic processing to interpret the data [

19,

20,

21]. Despite these limitations, IMUs have emerged as valuable tool for measuring trunk kinematics and ROM in various contexts, including clinical assessments and occupational studies [

22].

Concerning spine kinematics, the effectiveness and reliability of IMUs were evaluated by different studies, exploring their ability to provide accurate and consistent measurements when compared to gold standard systems. For instance, Liengswangwong et al. [

23] assessed and confirmed the accuracy of IMUs in measuring cervical spine motion; this finding was further reinforced by Ali et al. [

24], who reported a strong agreement between IMU measurements and marker-based MoCap data during walking, with thoracic trunk ROM values consistently ranging from of 2.4° to 2.6°. In addition, the effectiveness of IMUs in estimating spine kinematics was assessed in relation to marker-based MoCap across different movement planes. For instance, Schall and colleagues [

22] suggested that IMUs can capture trunk posture with reasonable reliability. Similarly, Parrington et al. [

24] reported that IMUs could estimate trunk ROM with moderate to excellent agreement under various conditions, such as standing and locomotion. This capability may be particularly beneficial for assessing populations with pathological conditions such as low back pain, where reliable measurement of trunk movements is essential for effective treatment planning [

25].

In general, literature underscores the potential of IMUs as a promising alternative to traditional motion capture technologies, providing a more accessible and portable solution for quantifying trunk overall kinematics and, more specifically, the ROMs. However, several challenges remain open. Factors such as the inherent differences in the measurements realized by different devices highlight the need for further research aimed at thoroughly evaluating the clinimetric properties of IMUs, such as reliability and validity of their use in different clinical scenarios.

In this context, we hypothesized that a wearable system based on a single IMU sensor was able to provide reliable information concerning trunk range of motion in different planes. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of a single IMU in measuring trunk range of motion (ROM) in healthy individuals, by comparing its outputs with those provided by a gold standard, i.e., a marker-based MoCap system. We supposed that the obtained findings could help to further bridge the gap between controlled laboratory-based human motion analysis and practical user-friendly solutions suitable for real-world applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The proposed investigaion was designed as a cross-sectional study which took place from May 2024 to October 2024, aimed to assess precision and accuracy of a wearable IMU sensor (Baiobit, Rivelo Srl—BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy), compared with an optoelectronic marker-based MoCap system (SMART DX 400 system, BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy). This research was carried out in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institution and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its latest amendments, it was approved by the Ethical Committees of Politecnico di Milano (22/2021, 14 June 2021). Written informed consent was signed by all participants. The reporting of the current study followed the updated STARD 2015 reporting guideline for diagnostic accuracy studies [

26].

2.2. Participants

All the experimental procedures were carried out at the “Posture and Movement Analysis Laboratory Luigi Divieti” located at Politecnico di Milano, Italy.

Healthy subjects were consecutively recruited on a voluntary basis among the staff of the University campus. Inclusion criteria were: aged 18 to 65 years, with a Body Mass Index (BMI) ranging from 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2; exclusion criteria included the presence of systemic, neurological and musculoskeletal conditions, and the inability to perform the requested tests for cognitive or psychiatric disorders that could prevent the completion of the required tests.

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

An a priori sample size calculation, assuming a strong correlation (r = 0.80), an alpha level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.80, suggested that a minimum of 15 participants would be sufficient to detect a significant correlation between the two technologies. Thence, a convenience sample of 27 healthy participants was recruited for this study, based on their availability to participate in the study. The full sample of 27 participants was retained to enhance the precision of the estimates and reduce the influence of outliers or missing data. This decision is consistent with methodological recommendations for reliability studies, which support the inclusion of larger samples when feasible [

26].

2.4. MoCap System

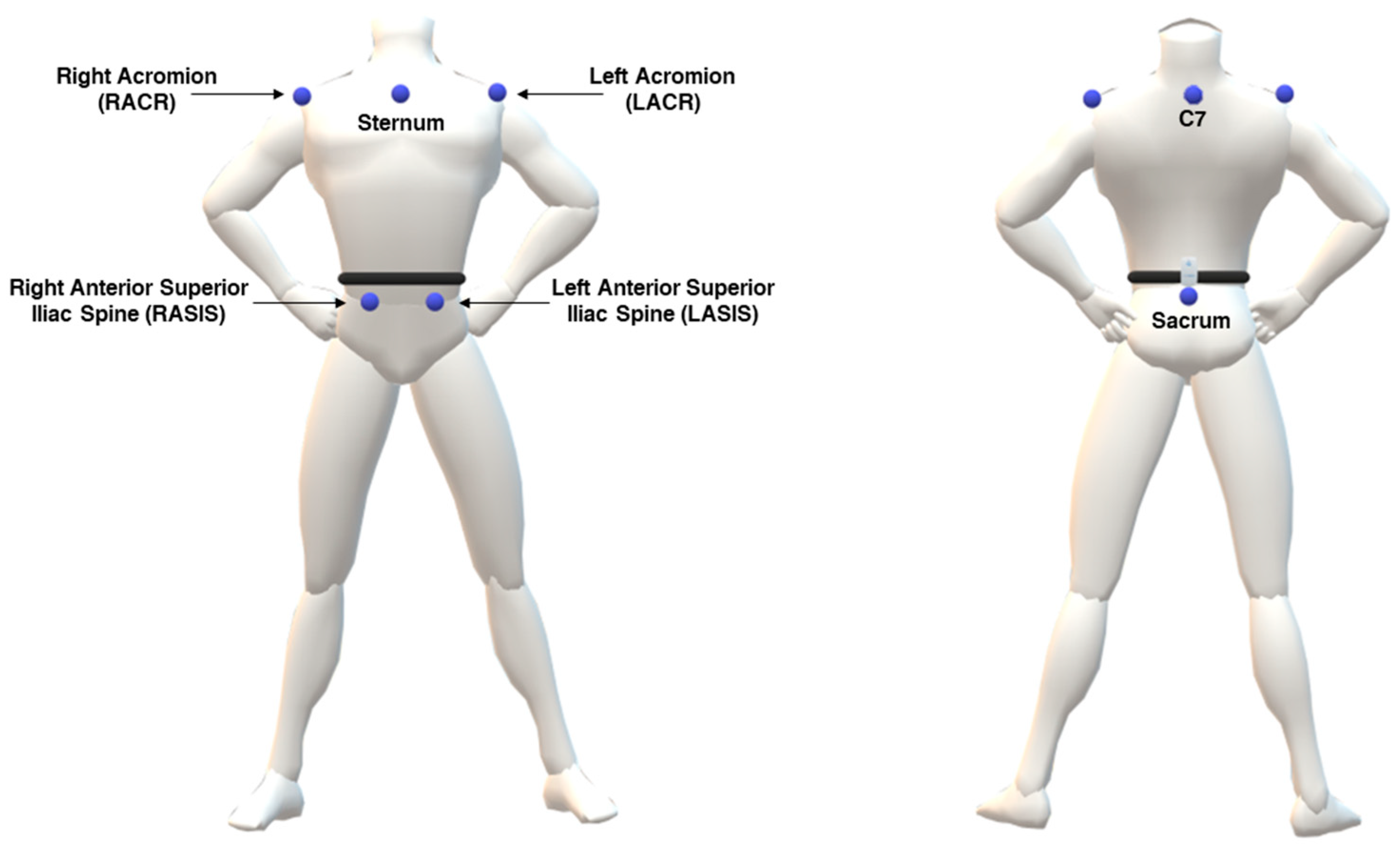

The marker-based MoCap system employed for data acquisition was the SMART DX 400 (BTSBioengineering, Milan, Italy), equipped with 8 cameras operating at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Anthropometric measurements of the participants included height and weight. Passive markers were attached to anatomical landmarks on each participant, following a customized marker set for upper body derived from Davis protocol [

27], considering markers on bilater acromion, seventh cervical vertebrae (C7), bilateral anterior superior iliac spine and sacrum with the adjunction of marker on sternum (

Figure 1). To maximize reliability of the procedure, the anatomical landmarks were identified manually through palpation by two different operators for each tested participant, focusing on regions with minimal soft tissue between the bone and skin.

2.5. IMU-Based System

The tested wearable IMU-based system (Baiobit, Rivelo Srl – BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy), was a medical device designed for clinical motor assessment. The device (dimensions: 70 × 40 × 18 mm, weight: 37 g; sample frequency: 100 Hz) integrates multiple sensors, including a tri-axial accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer, enabling a detailed assessment of motion within its 3D local coordinate system. The IMU provides orientation data that allows the algorithm to compute roll (axial rotation), pitch (antero-posterior inclination), and yaw (lateral inclination) angles. The IMU is able to wirelessly communicate with a personal computer via BLE technology. The IMU can be attached to user’s body via adjustable elastic bands to address different body location, preventing unwanted sensor’s displacement throughout the movement.

2.6. Testing Procedures

For data collection, each participant was simultaneously equipped with the previously described marker set and the IMU. According to manufacturer’s instruction, the IMU was placed approximately at L5/S1 vertebrae level using a customized elastic belt.

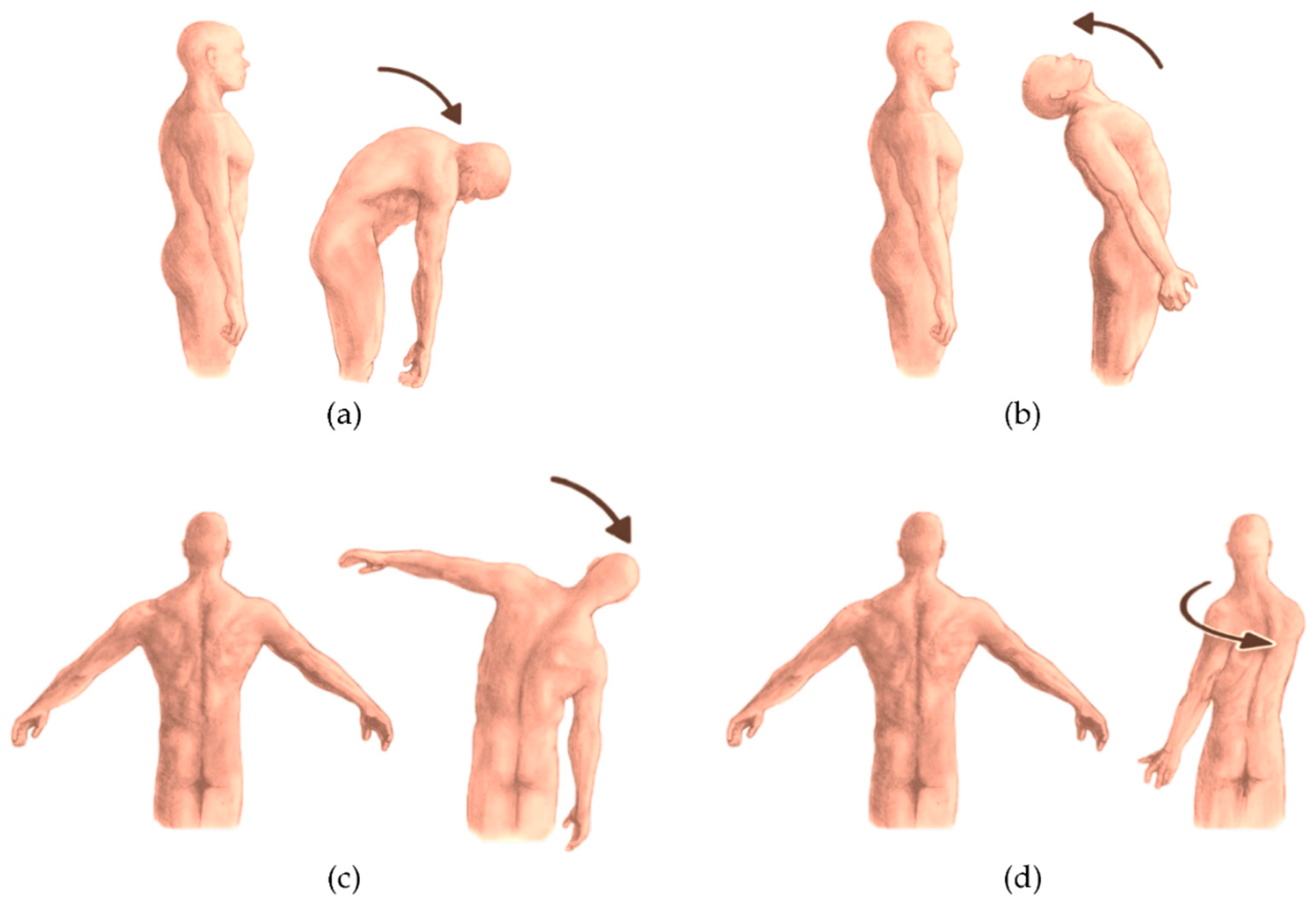

Starting from a neutral standing position, each participant was then required to perform the following tasks (

Figure 2):

Trunk flexion (

Figure 2a): participants bent forward at the waist level while maintaining a neutral spine, aiming to reach toward the floor without knee flexion;

Trunk extension (

Figure 2b): participants extended the trunk backward while ensuring hip stability;

Lateral bending toward right/left (

Figure 2c): participants performed a lateral bending movement at the waist, lowering one arm toward the corresponding leg while maintaining pelvic stability;

Trunk Rotation toward right/left (

Figure 2d): participants rotated the upper body to one side while keeping the hips oriented forward.

Each task was performed in two sets of six repetitions (per side for bilateral movements). Participants were instructed to perform the movements at their natural, self-selected pace.

2.7. Data Analysis and Processing

Raw data acquired with the marker-based MoCap system were initially processed using the proprietary software, i.e., SMARTtracker (version: 1.10.465.0; BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy). This step involved labelling each marker, so as to assign it to its corresponding anatomical landmark. In particular, for this evaluation the attention was focused on the following markers: C7, left and right acromion, left and right antero-superior iliac spines, sacrum.

Subsequently, the processed data were imported into SMARTanalyzer software (version: 1.10.465.0; BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy) for further analysis through custom routines designed to extract quantitative measurements. The 3D marker coordinates underwent linear interpolation and were filtered using a 5 Hz low-pass Butterworth filter to minimize noise. Task-specific routines were employed to calculate relevant rotation angles and their corresponding ROM. In particular, trunk orientation was calculated with respect to the fixed laboratory coordinate system, providing an absolute measure of the movement. The angles were computed using Euler angles, ensuring a precise evaluation of trunk kinematics within the global reference frame.

Repetitions for each task were identified by locating the maximum and minimum values along the angular curve. For each repetition, ROM was determined as the difference in degrees (°) between the maximum and minimum values.

IMU data were processed through an ad hoc and custom MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, United States) routine. Raw data, including accelerometer and gyroscope readings preprocessed by a Digital Motion Processor (DMPTM), which provided rotational angles (i.e., roll, pitch, and yaw), were processed to obtain Cardan angles referred to the global reference system. Cardan angles about the IMU axes were calculated using the YZX sequence (i.e., flexion-extension around Y; lateral bending around Z axis; axial rotation around X axis) as generalized by Cole [

28] using as reference frame the mean angles calculated during the stabilization phase defined as a 5-second window in which acceleration variations fell below 0.2 m/s². Functional angles were then extracted so as to quantify lateral bending, flexion/extension, and axial rotation, from which the ROM was calculated as the difference in degrees (°) between the maximum and minimum values.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The normality of the ROM data was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test, and a normal distribution was confirmed for the variables of interest; consequently, variables were statistically described as mean and standard deviation.

The comparison of ROM values obtained from the marker-based MoCap and IMU was evaluated by assessing the accuracy and the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), calculated as per the following equations:

In Equation 2, ŷᵢ represents the ROM values derived from the marker-based MoCap system, yᵢ refers to the ROM values from the IMU system, eᵢ denotes the error, and n is the total number of observations or participants.

To evaluate the agreement between the two systems, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) were calculated. In fact, Pearson’s correlation coefficient quantifies the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables. The value of r ranges from -1 to 1, where the extreme values indicate a strong (positive or negative) correlation, whereas values around zero suggest the absence of linear relationship. The strength of the correlation was classified as follows: |r| ≤ 0.4, weak; 0.4 < |r| ≤ 0.6, moderate; 0.6 < |r| ≤ 0.8, strong; and |r| > 0.8, very strong [

29]. The CCC evaluates the agreement between two continuous variables by combining measures of precision and accuracy, it ranges from -1 to +1, where 1 suggests perfect agreement, 0 indicates no agreement and -1 implies disagreement [

30].

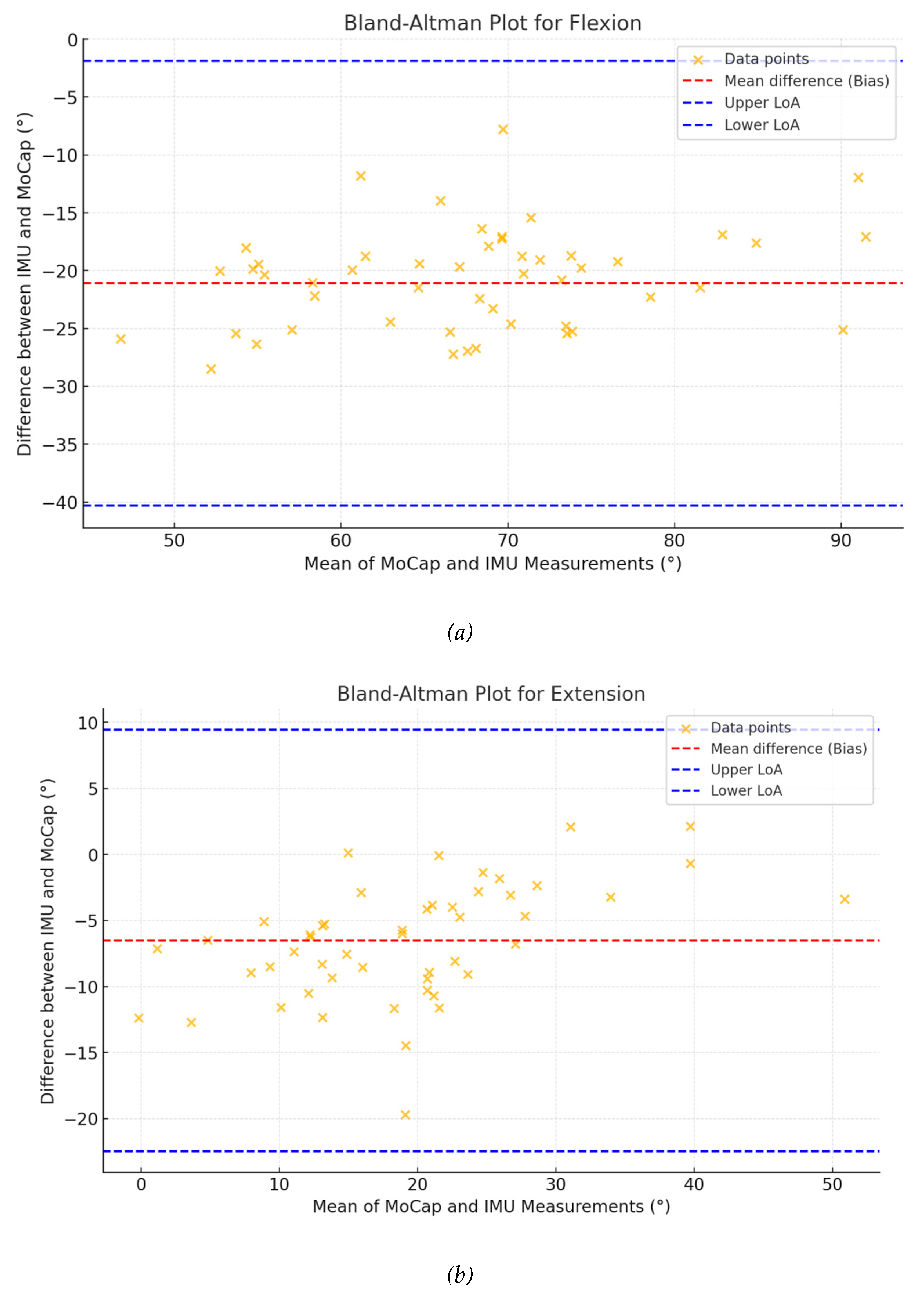

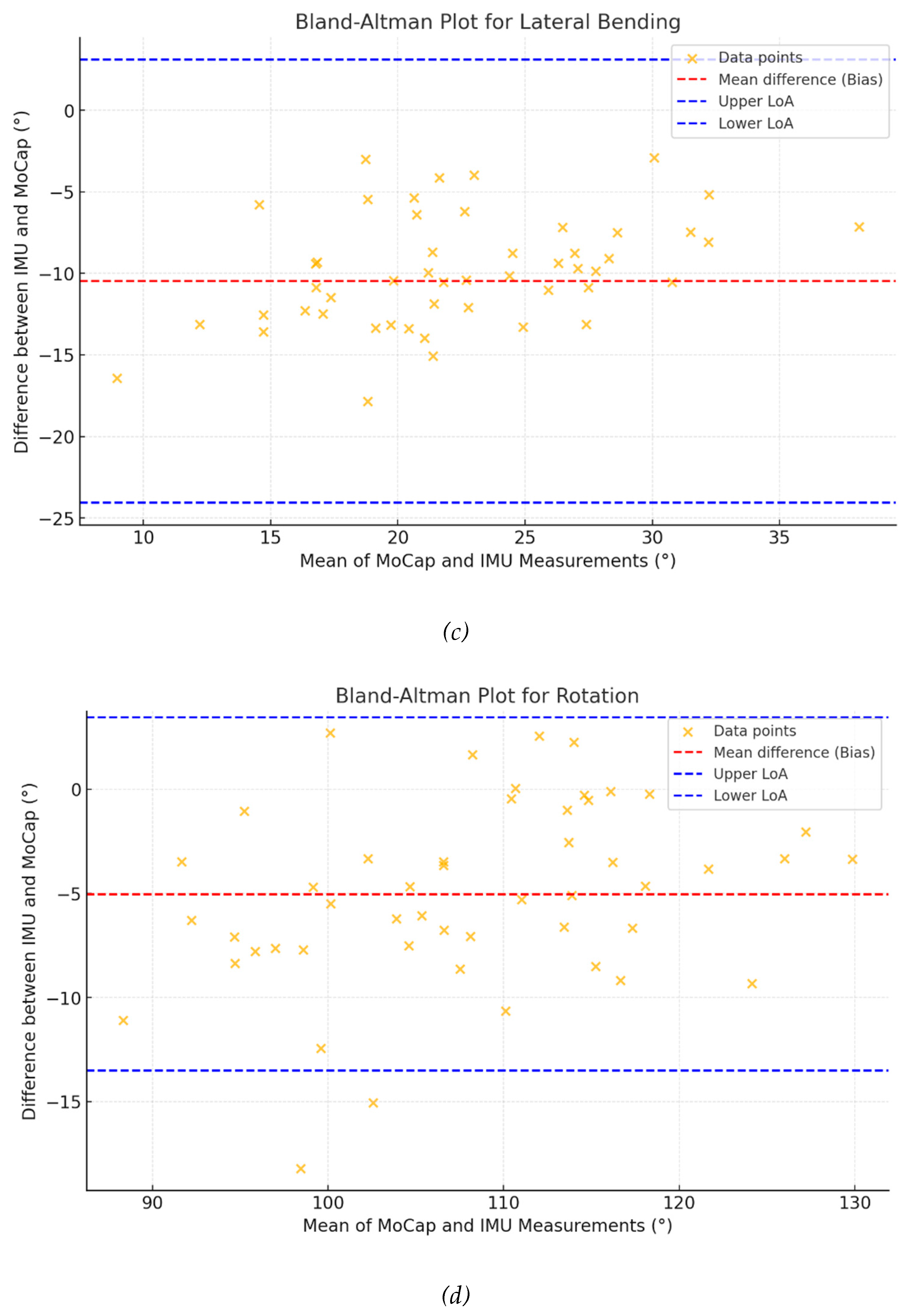

Additionally, Bland–Altman (BA) plots were used to visualize the level of agreement (LoA) between the measurements [

31].

All statistical tests were performed with a significance level set at α = 0.05

3. Results

The study included 27 participants, with male/female ratio of 11/16. The participants’ age ranged from 20 to 61 years (age: 31.1 ± 11.0 years), while the BMI spanned from 17.3 to 25.4 kg/m2. All the main characteristics of the sample are detailed in

Table 1

The mean values for ROM measured by the marker-based MoCap and IMU systems were respectively as follows: flexion (78.5°±9.8° vs. 57.4°±14.4°), extension (21.2°±8.14° vs. 14.7°±5.92°), lateral-bending (27.2°±6.93° vs. 16.7°±4.76°), and rotation (113°±28.3° vs. 108°±27.0°). Standard deviations showed greater variability in IMU measurements for flexion (14.4°) compared to MoCap (9.80°); conversely, similar trends were observed for other motions.

3.1. Accuracy and RMSE

The mean percentage of accuracy values for IMU measurements showed varying degrees of agreement with MoCap data: flexion 72.1% (SD: 12.7%), extension 64.1% (SD: 23.5%), lateral-bending 61.4% (SD: 16.8%), and rotation 92.4% (SD: 7.61%). RMSE values highlighted discrepancies across movements, with the largest error in flexion: 3.01° (SD: 1.32°), and the smallest in rotation: 1.09° (SD: 1.01°). Data are summarised in

Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, Accuracy and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for the motion assessed with IMU and MoCap technologies.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, Accuracy and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for the motion assessed with IMU and MoCap technologies.

| Analyzed movement |

MoCap (°) |

IMU (°) |

Accuracy (%) |

RMSE (°) |

| Flexion |

78.5 (9.8) |

57.4 (14.4) |

72.1 (12.7) |

3.01 (1.32) |

| Extension |

21.2 (8.14) |

14.7 (5.92) |

64.1 (23.5) |

1.15 (0.83) |

| Lateral-bending |

27.2 (6.93) |

16.7 (4.76) |

61.4 (16.8) |

1.59 (0.84) |

| Rotation |

113.0 (28.3) |

108.0 (27.0) |

92.4 (7.61) |

1.09 (1.01) |

3.2. Correlation and Agreement Analysis

Pearson’s correlation and CCC values are reported in Table 3. The analysis showed strong to very strong relationships between IMU and MoCap for flexion and rotation (r = 0.703, p < 0.001 and r = 0.944, p < 0.001, respectively); correlations for extension (r = 0.564, p < 0.001) and lateral-bending (r = 0.430, p = 0.003) were moderate. The CCC was highest for rotation (CCC = 0.927, 95% CI: 0.877–0.957), indicating strong agreement, while lower values were observed for lateral-bending (CCC = 0.155, 95% CI: 0.046–0.260). Flexion and extension showed moderate agreement with CCC values of 0.262 and 0.375, respectively.

Table 2.

Correlation and Bland-Altman statistics for the motion assessed with IMU and MoCap technologies.

Table 2.

Correlation and Bland-Altman statistics for the motion assessed with IMU and MoCap technologies.

| Motion |

Pearson “r” |

p-value |

CCC (95%CI) |

Bias° |

LoA Lower° |

LoA Upper° |

| Flexion |

0.703 |

<0.001 |

0.262 (0.156-0.363) |

-21.09 |

-41.18 |

-1.01 |

| Extension |

0.564 |

<0.001 |

0.375 (0.187-0.537) |

-6.53 |

-19.96 |

6.91 |

| Lat. Bending |

0.430 |

0.003 |

0.155 (0.004-0.260) |

-10.48 |

-23.23 |

2.26 |

| Rotation |

0.944 |

<0.001 |

0.927 (0.877-0.957) |

-5.12 |

-23.56 |

13.31 |

Bland-Altman analyses (

Figure 3) revealed biases ranging from -21.09° for flexion to -5.12° for rotation, with narrower limits of agreement in rotation) compared to flexion (-23.56° to 13.31° and -41.18° to -1.01°, respectively).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the overall reliability of an IMU-based wearable device in measuring trunk range of motion (ROM), by comparing it with respect to a marker-based optoelectronic MoCap system, which can be considered the actual gold standard in human motion analysis. Our findings provide relevant insights into the applicability and limitations of the IMU-based system utilized for trunk motion analysis.

The results showed that the IMU device provided comparable but consistently lower ROM values across all movements. For instance, the IMU underestimated flexion and lateral-bending compared to the marker-based MoCap system. In our opinion, this systematic underestimation may reflect intrinsic differences in the data acquisition and processing methods of the two systems [

32,

33].

Despite this discrepancy, the high accuracy observed for rotation (92.4%) underscores the potential of the IMU technology for analyzing specific types of trunk movements.

The RMSE values revealed several levels of agreement between the two systems, with the largest discrepancies observed for the case of flexion (3.01°) and the smallest in case of rotation (1.09°). This variability could be explained by the physiological and biomechanical characteristics of the different trunk movements, which might affect the reliability of the IMU; in this regard, Lee and colleagues (2023) reported that RMSE for upper trunk movements during a simulated task ranged from 1.6° to 2.9°, indicating that different trunk movements can lead to variability in measurement accuracy [

34]; in the same way, Khobkhun et al. demonstrated how accelerometers and gyroscopes can be influenced by the subject’s posture and movement dynamic [

35]. Additionally, the higher variability in IMU measurements, particularly for flexion (SD = 14.4°), may highlight the influence of measurement noise [

36].

Furthermore, it should be considered that misalignments errors are possible, indeed [

37,

38]. In the presented study, the IMU was placed to the lumbo-sacral region of each participant, by using an elastic belt; although this belt was necessary to fix the device to the trunk, a certain degree of relative motion occurred between the participant’s body and the sensor itself - due also to the presence of possible soft tissue artifacts - potentially accounting for some measurement accuracy issues, which were clearly observed both during flexion and lateral bending tasks.

The Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated strong relationships between the IMU and the marker-based MoCap system, particularly for flexion (r = 0.703) and rotation (r = 0.944). However, moderate correlations for extension (r = 0.564) and lateral bending (r = 0.430) are encouraging but suggest that certain motions may be more challenging to capture accurately with the IMU system. Once again, this finding can be interpreted in light of the potential displacements of the IMU device during various movements, particularly those involving flexion, extension, and lateral bending, as opposed to rotation. Additionally, the Bland-Altman analysis provided further insight into the agreement between the two systems, showing narrower limits of agreement for rotation compared to flexion, indicating better consistency for rotational movements. Furthermore, for each movement, the data points were randomly distributed around the mean difference (bias), suggesting the absence of any specific angle-dependent discrepancy between the two technologies, particularly during rotational movements. Finally, the mean difference values between the two measures are considerable relatively low and appear to correlate with the amplitude of each movement, i.e., higher for flexion and lateral bending, and lower for extension and rotation. This aspect was already reported by some authors [

38], though there is no complete agreement in literature [

39].

The CCC values supported these findings, with rotation showing the highest level of agreement (CCC = 0.927), when side-bending had the lowest (CCC = 0.155). This suggests that while the IMU-based system performs well for specific motions, it may require further adjustment to improve its performance for others, such as lateral bending and extension.

These findings substantially overlap with previous research highlighting the advantages of IMU-based systems, such as portability, ease of use, and real-time data acquisition [

32,

40]. However, the observed limitations emphasize the need for further improvements at different levels (i.e., compliance to soft tissue artifacts) to strengthen overall reliability and reduce errors, and the use of machine learning and artificial neural networks may be promising tools [

41,

42]. Importantly, the lower ecological validity of laboratory-based MoCap systems remains a significant limitation, and the IMU capacity for real-world application makes it an interesting alternative [

32,

40].

The IMU-based wearable device demonstrates promising potential as a cost-effective and practical tool for trunk ROM analysis. Our findings suggest that it cannot yet fully replace the precision of a gold-standard marker-based MoCap system; however, its application in clinical and real-world settings offers substantial advantages, warranting further development and assessment [

33]. This could pave the way for a wider adoption of wearable technologies in daily rehabilitation practices, enabling clinicians to monitor and assess patients’ motor performance with greater efficiency [

43,

44,

45].

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, it was conducted on a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study included only healthy participants, which does not allow for conclusions regarding the applicability of these tools in clinical populations, or individuals with movement disorders. Third, potential errors may have occurred due to a lack of precise instructions provided to participants, prior to performing the motor tasks. Finally, the elastic belt used to secure the IMU sensor may have allowed slight displacements during the execution of motor tasks, potentially affecting the precision of the collected data.

Since this study exclusively focused on healthy participants, future research should investigate the performance of IMU sensors for trunk movements in individuals with musculoskeletal disorders, where compensatory movements and functional limitations might further require their use in the clinical field [

46]. Lastly, refining the calibration procedures and algorithms for the IMU system may help reduce measurement discrepancies [

47].

Future research should focus on expanding the scope of IMU-based evaluations to also include other acceleration-derived metrics (e.g. root mean square, improved harmonic ratio and jerk). These indicators might be indicative for postural stability, movement symmetry, and smoothness, which are critical for understanding trunk movement dynamics [

48]. Investigating these parameters in populations with musculoskeletal disorders would provide further essential insights into their clinical relevance and the potential for targeted interventions [

49]. Additionally, studies involving larger and more heterogeneous cohorts, including individuals with specific pathologies, are needed to further validate the utility of IMU sensors in complex clinical scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This study highlighted that an IMU-based wearable sensor could provide a feasible and cost-effective alternative to gold-standard MoCap systems for trunk movement analysis, resulting particularly precise and accurate in the measurement of the rotation task. Although systematic underestimations and a certain degree of variability were observed for other motions, the IMU’s portability and real-world applicability make it a promising tool for clinical and home-based settings. Further protocol adjustments and validation in clinical populations are necessary to enhance accuracy and extend its utility.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, FDF and VC.; methodology, VC, NFL.; formal analysis, FDF, SC, VC.; investigation, FDF, SC.; resources, VC.; data curation, FDF, SC, VC; writing—original draft preparation, FDF, SC, MPo, MPa2, MG; writing—review and editing, FDF, VC, MG, NFL; supervision, VC, MPa, MG, NFL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of POLITECNICO OF MILAN (protocol 22/2021, 14 June 2021 ).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data collected and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alexia Lanzaro for her valuable help in data acquisition and processing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ROM |

Range of Motion |

| MoCap |

Motion Capture |

| IMU |

Inertial Measurment Unit |

| LBP |

Low Back Pain |

| |

|

| |

|

References

- Benedetti, M. G., & Negrini, S. (2016). Instrumental motion analysis: from the research laboratory to the rehabilitation clinic. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 52(4), 557–559.

- Quinn, L., Riley, N., Tyrell, C. M., Judd, D. L., Gill-Body, K. M., Hedman, L. D., Packel, A., Brown, D. A., Nabar, N., & Scheets, P. (2021). A Framework for Movement Analysis of Tasks: Recommendations From the Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy’s Movement System Task Force. Physical therapy, 101(9), pzab154. [CrossRef]

- Martin, C., Phillips, B. A., Kilpatrick, T. J., Butzkueven, H., Tubridy, N., McDonald, E., … & Galea, M. P. (2006). Gait and balance impairment in early multiple sclerosis in the absence of clinical disability. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 12(5), 620-628. [CrossRef]

- Stolze, H., Klebe, S., Baecker, C., Zechlin, C., Friege, L., Pohle, S., … & Deuschl, G. (2004). Prevalence of gait disorders in hospitalized neurological patients. Movement Disorders, 20(1), 89-94. [CrossRef]

- Dal Farra, F., Arippa, F., Carta, G., Segreto, M., Porcu, E., & Monticone, M. (2022). Sport and non-specific low back pain in athletes: a scoping review. BMC sports science, medicine & rehabilitation, 14(1), 216. [CrossRef]

- Reis, F. J. J. d. and Macedo, A. R. d. (2015). Influence of hamstring tightness in pelvic, lumbar and trunk range of motion in low back pain and asymptomatic volunteers during forward bending. Asian Spine Journal, 9(4), 535. [CrossRef]

- Dal Farra, F., Arippa, F., Arru, M., Cocco, M., Porcu, E., Tramontano, M., & Monticone, M. (2022). Effects of exercise on balance in patients with non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 58(3), 423–434. [CrossRef]

- M. VanDijk, N. Smorenburg, B. Visser, Y.F. Heerkens, M.W.G. Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden How clinicians analyze movement quality in patients with non-specific low back pain: a cross-sectional survey study with Dutch allied health care professionals. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord., 18 (2017), pp. 1-11.

- Schlager, A., Ahlqvist, K., Rasmussen-Barr, E. et al. Inter- and intra-rater reliability for measurement of range of motion in joints included in three hypermobility assessment methods. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19, 376 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R., Vela, L., Moreno-Verdú, M., Ferreira-Sánchez, M. d. R., Macías-Macías, Y., & Miangolarra-Page, J. C. (2020). Trunk range of motion is related to axial rigidity, functional mobility and quality of life in parkinson’s disease: an exploratory study. Sensors, 20(9), 2482. [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M., Mirzaei, M., & Khabiri, S. (2019). Universal goniometer and electro-goniometer intra-examiner reliability in measuring the knee range of motion during active knee extension test in patients with chronic low back pain with short hamstring muscle. BMC Sports Science Medicine and Rehabilitation, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. and Kim, E. (2016). Test-retest reliability of an active range of motion test for the shoulder and hip joints by unskilled examiners using a manual goniometer. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28(3), 722-724. [CrossRef]

- McGinley, J. L., Baker, R., Wolfe, R., & Morris, M. E. (2009). The reliability of three-dimensional kinematic gait measurements: A systematic review. Gait & Posture, 29(3), 360–369. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Aldana, A. C., Callejas-Cuervo, M., & Bó, A. P. L. (2020). Upper limb physical rehabilitation using serious videogames and motion capture systems: a systematic review. Sensors, 20(21), 5989. [CrossRef]

- Moro, M., Marchesi, G., Hesse, F., Odone, F., & Casadio, M. (2022). Markerless vs. marker-based gait analysis: a proof of concept study. Sensors, 22(5), 2011. [CrossRef]

- Poitras, I., Dupuis, F., Bielmann, M., Campeau-Lecours, A., Mercier, C., Bouyer, L. J., … & Roy, J. (2019). Validity and reliability of wearable sensors for joint angle estimation: a systematic review. Sensors, 19(7), 1555. [CrossRef]

- Fong, D. T. and Chan, Y. M. (2010). The use of wearable inertial motion sensors in human lower limb biomechanics studies: a systematic review. Sensors, 10(12), 11556-11565. [CrossRef]

- Cerfoglio, S., Capodaglio, P., Rossi, P., Conforti, I., D’Angeli, V., Milani, E., … & Cimolin, V. (2023). Evaluation of upper body and lower limbs kinematics through an imu-based medical system: a comparative study with the optoelectronic system. Sensors, 23(13), 6156. [CrossRef]

- Tadano, S., Takeda, R., & Miyagawa, H. (2013). Three dimensional gait analysis using wearable acceleration and gyro sensors based on quaternion calculations. Sensors, 13(7), 9321-9343. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Khoo, S., & Yap, H. J. (2020). Differences in motion accuracy of baduanjin between novice and senior students on inertial sensor measurement systems. Sensors, 20(21), 6258. [CrossRef]

- Manupibul, U., Tanthuwapathom, R., Jarumethitanont, W., Kaimuk, P., Limroongreungrat, W., & Charoensuk, W. (2023). Integration of force and imu sensors for developing low-cost portable gait measurement system in lower extremities. Scientific Reports, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Schall, M. C., Fethke, N. B., Chen, H., Oyama, S., & Douphrate, D. I. (2015). Accuracy and repeatability of an inertial measurement unit system for field-based occupational studies. Ergonomics, 59(4), 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Liengswangwong, W., Lertviboonluk, N., Yuksen, C., Jamkrajang, P., Limroongreungrat, W., Mongkolpichayaruk, A., … & Thaipasong, S. (2024). Validity of inertial measurement unit (imu sensor) for measurement of cervical spine motion, compared with eight optoelectronic 3d cameras under spinal immobilization devices. Medical Devices: Evidence and Research, Volume 17, 261-269. [CrossRef]

- Parrington, L., Jehu, D. A., Fino, P. C., Pearson, S., El-Gohary, M., & King, L. A. (2018). Validation of an inertial sensor algorithm to quantify head and trunk movement in healthy young adults and individuals with mild traumatic brain injury. Sensors, 18(12), 4501. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M., Ashouri, S., Abedi, M., Azadeh-Fard, N., Parnianpour, M., Khalaf, K., … & Rashedi, E. (2020). Using a motion sensor to categorize nonspecific low back pain patients: a machine learning approach. Sensors, 20(12), 3600. [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, LijmerJG Moher D, Rennie D, de Vet HCW, Kressel HY, Rifai N, Golub RM, Altman DG, Hooft L, Korevaar DA, Cohen JF, For the STARD Group. STARD 2015: An Updated List of Essential Items for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies.

- Davis, R. B., Õunpuu, S., Tybursky, D., & Gage, J. R. (1991). A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Human Movement Science, 10(5), 575–587. [CrossRef]

- Cole, G.K., Nigg, B.M., Ronsky, J.L., Yeadon, M.R., 1993. Application of the joint coordinate system to three-dimensional joint attitude and movement representation: a standardization proposal. J Biomech Eng. 115(4A):344-9.

- Akoglu H. (2018). User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish journal of emergency medicine, 18(3), 91–93. [CrossRef]

- Hiriote, S. and Chinchilli, V. M. (2011). Matrix-based concordance correlation coefficient for repeated measures. Biometrics, 67(3), 1007-1016. [CrossRef]

- Zaki, R. A., Bulgiba, A., Ismail, R., & Ismail, N. A. (2012). Statistical methods used to test for agreement of medical instruments measuring continuous variables in method comparison studies: a systematic review. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e37908. [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, M., Nicholas, K., Button, K., Sparkes, V., Sheeran, L., & Davies, J. (2018). Inertial measurement units for clinical movement analysis: reliability and concurrent validity. Sensors, 18(3), 719. [CrossRef]

- Cerfoglio, S., Lopomo, N. F., Capodaglio, P., Scalona, E., Monfrini, R., Verme, F., Galli, M., & Cimolin, V. (2023). Assessment of an IMU-Based Experimental Set-Up for Upper Limb Motion in Obese Subjects. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 23(22), 9264. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R., Akhundov, R., James, C., Edwards, S., & Snodgrass, S. J. (2023). Variations in concurrent validity of two independent inertial measurement units compared to gold standard for upper body posture during computerised device use. Sensors, 23(15), 6761. [CrossRef]

- Khobkhun, F., Hollands, M. A., Richards, J., & Ajjimaporn, A. (2020). Can we accurately measure axial segment coordination during turning using inertial measurement units (imus)? Sensors, 20(9), 2518. [CrossRef]

- Suvorkin, V., Garcia-Fernandez, M., González-Casado, G., Li, M., & Rovira-Garcia, A. (2024). Assessment of noise of mems imu sensors of different grades for gnss/imu navigation. Sensors, 24(6), 1953. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K., Li, J., Li, D., Fan, B., & Shull, P. B. (2023). Imu shoulder angle estimation: effects of sensor-to-segment misalignment and sensor orientation error. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 31, 4481-4491. [CrossRef]

- Lebleu, J., Gosseye, T., Detrembleur, C., Mahaudens, P., Cartiaux, O., & Penta, M. (2020). Lower limb kinematics using inertial sensors during locomotion: accuracy and reproducibility of joint angle calculations with different sensor-to-segment calibrations. Sensors, 20(3), 715. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z., Woodford, S. C., Senanayake, D., & Ackland, D. C. (2023). Conversion of upper-limb inertial measurement unit data to joint angles: a systematic review. Sensors, 23(14), 6535. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. and Yoon, S. (2021). Validity evaluation of an inertial measurement unit (imu) in gait analysis using statistical parametric mapping (spm). Sensors, 21(11), 3667. [CrossRef]

- Almassri, A. M. M., Shirasawa, N., Purev, A., Uehara, K., Oshiumi, W., Mishima, S., … & Wagatsuma, H. (2022). Artificial neural network approach to guarantee the positioning accuracy of moving robots by using the integration of imu/uwb with motion capture system data fusion. Sensors, 22(15), 5737. [CrossRef]

- Adans-Dester, C., Hankov, N., O’Brien, A., Vergara-Diaz, G., Black-Schaffer, R. M., Zafonte, R., … & Bonato, P. (2020). Enabling precision rehabilitation interventions using wearable sensors and machine learning to track motor recovery. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Olmedo, J. M., Pueo, B., Mossi, J. M., & Villalón-Gasch, L. (2023). Concurrent validity of the inertial measurement unit vmaxpro in vertical jump estimation. Applied Sciences, 13(2), 959. [CrossRef]

- Komaris, D., Tarfali, G., O’Flynn, B., & Tedesco, S. (2022). Unsupervised imu-based evaluation of at-home exercise programmes: a feasibility study. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. I., Adans-Dester, C., O’Brien, A., Vergara-Diaz, G., Black-Schaffer, R. M., Zafonte, R., … & Bonato, P. (2021). Predicting and monitoring upper-limb rehabilitation outcomes using clinical and wearable sensor data in brain injury survivors. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 68(6), 1871-1881. [CrossRef]

- Dal Farra, F., Arippa, F., Arru, M., Cocco, M., Porcu, E., Solla, F., & Monticone, M. (2025). Is dynamic balance impaired in people with non-specific low back pain when compared to healthy people? A systematic review. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 61(1), 72–81. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q., Liu, L., Mei, F., & Yang, C. (2021). Joint constraints based dynamic calibration of imu position on lower limbs in imu-mocap. Sensors, 21(21), 7161. [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M., Orejel Bustos, A. S., Montemurro, R., Vasta, S., Marangon, G., Belluscio, V., Morone, G., Modugno, N., Buzzi, M. G., Formisano, R., Bergamini, E., & Vannozzi, G. (2024). Dynamic Stability, Symmetry, and Smoothness of Gait in People with Neurological Health Conditions. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 24(8), 2451. [CrossRef]

- Castiglia, S. F., Dal Farra, F., Trabassi, D., Turolla, A., Serrao, M., Nocentini, U., Brasiliano, P., Bergamini, E., & Tramontano, M. (2025). Discriminative ability, responsiveness, and interpretability of smoothness index of gait in people with multiple sclerosis. Archives of physiotherapy, 15, 9–18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).