1. Introduction

Many Neotropical deer species have exhibited a declining population trend, with estimated reductions in their geographic distribution ranging from 40% to 90% [

1]. Their conservation status is considerably more critical when compared to that of other mammalian taxa worldwide. While approximately 25% of all mammal species are currently classified as threatened and 15% as data-deficient [

2], the scenario is more alarming for Neotropical deer: 53% are listed under some level of threat, and 17.6% are considered data-deficient due to insufficient studies confirming their actual status [

3]. As wild populations decline, there is a corresponding reduction in genetic diversity and an increase in consanguineous mating (inbreeding), thereby elevating the risk of extinction [

4].

Taxonomic ambiguities further complicate the conservation of these species. It is suggested that numerous species remain undescribed, and for many, accurate differentiation through traditional methodologies is particularly challenging. Morphological homoplasy among several taxa highlights the presence of cryptic species complexes [

5,

6], where morphology proves to be an unreliable diagnostic tool. Similarly, while molecular genetic studies using mitochondrial or nuclear markers have been informative, they have occasionally lacked the resolution needed to distinguish evolutionary lineages, which were only clarified through cytogenetics [

7,

8]. Thus, karyotypic analysis has emerged as a highly relevant approach, as it facilitates species-level differentiation, and the establishment of reproductive isolation, which is essential for taxonomic validation [

6,

9,

10].

Following species validation, it becomes possible to initiate foundational studies to address knowledge gaps regarding ecological distribution (extent of occurrence and area of occupancy) and population structure (number of locations and subpopulations). Such information is crucial for the development of targeted conservation strategies, including the designation of protected areas to support species that have previously been overlooked or unknown [

11].

Nonetheless, cytogenetic analyses require the collection of viable cells from living or recently deceased individuals, as the preparation of chromosome spreads necessitates metabolically active cells. In addition to their relevance in cytogenetic research, somatic cells represent a valuable biological resource [

12,

13,

14], especially in the establishment of germplasm banks aimed at preserving the genetic diversity of threatened populations. Reproductive biotechnologies allow for the conservation and potential future use of various cell types to reintroduce alleles that may be lost in wild populations. These technologies include somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) and the differentiation of stem cells into gametes [

11].

However, obtaining viable cells from cervids is particularly challenging due to their behavioral and ecological characteristics. Many species are elusive, stress-prone, and highly adapted to forested environments, with some being extremely rare. Therefore, recovering and cryopreserving fibroblasts from deceased individuals can be a valuable strategy, enabling the collection of biological material from animals affected by fatal events such as roadkill, poaching, domestic dog attacks, disease, wildfires, and other causes. While freshly collected samples can be used directly for cell culture, in field conditions it is rarely possible to access nearby laboratories with the necessary infrastructure [

14]. Thus, the cryopreservation of tissue samples becomes a critical procedure, with the time interval between sample collection and processing being a determining factor for cell viability.

Post-mortem, cellular components degrade progressively, which can compromise the integrity of genetic material, rendering subsequent genetic analyses unviable [

15]. The rate at which post-mortem cellular activity ceases is influenced by several variables, including environmental conditions (e.g., ambient temperature and humidity) and intrinsic factors of the animal (e.g., age and health status) [

15]. Therefore, the present study aimed to assess cellular viability of skin tissue collected following the death of individual from two species of Neotropical deer, whose carcasses were maintained under natural field conditions (i.e., without temperature control and in non-sterile environments). Different time intervals between death and the collection of biological material were evaluated. Fresh and cryopreserved skin samples were subjected to cell culture to determine the viability of the derived fibroblast cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

This work was evaluated and approved by the Ethics and Animal Welfare Committee (CEBEA) of the Faculty of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences (FCAV) of São Paulo State University (UNESP), Jaboticabal campus, under protocol Nº. 005433/19. The study complies with the ethical principles in animal experimentation adopted by the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA).

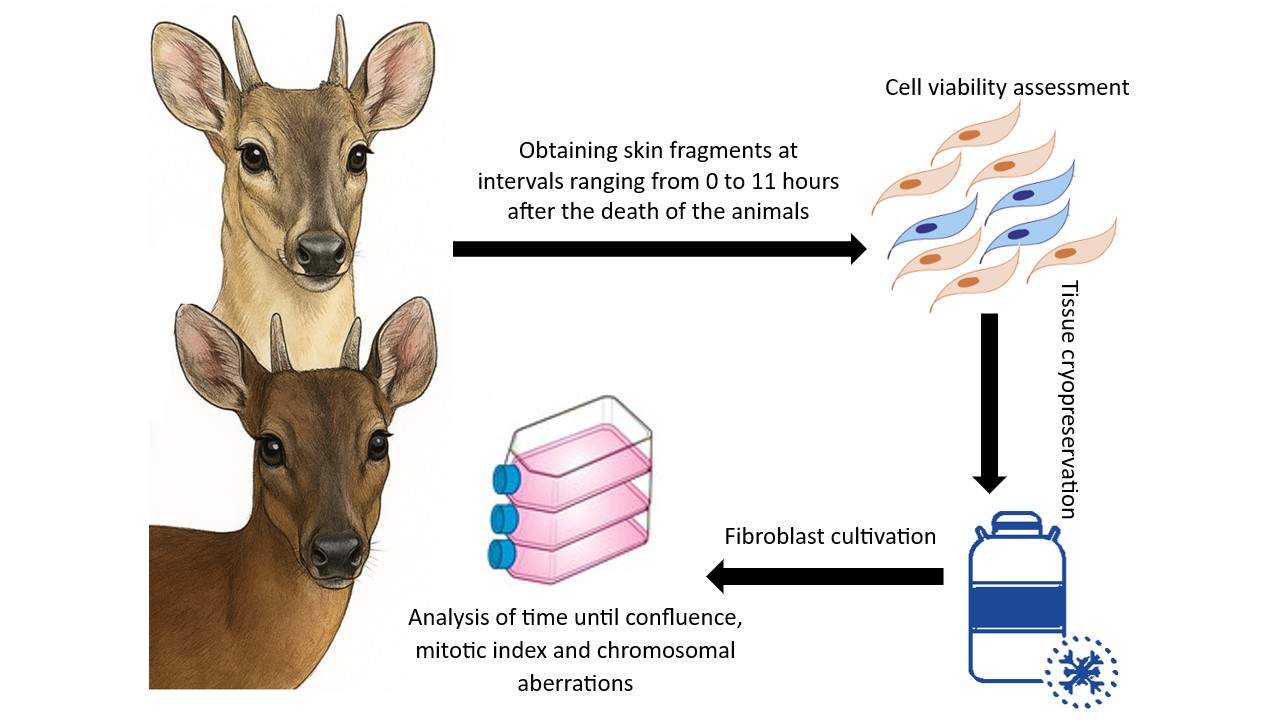

Sample Collection

Two individuals were used in this study: a female of the species

Mazama rufa (Animal 1 – A1) and a male of the species

Subulo gouazoubira (Animal 2 – A2), both housed in captivity at the Deer Research and Conservation Center (NUPECCE), Department of Animal Science, School of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences, São Paulo State University (UNESP), Jaboticabal Campus. The animals were chemically restrained using a combination of anesthetic agents—7 mg/kg of ketamine hydrochloride and 1 mg/kg of xylazine hydrochloride—administered intramuscularly via manual injection within a restraining box [

16], followed by euthanasia through intravenous administration of 1 g of sodium thiopental.

The carcasses were maintained in a room without temperature control, where ambient temperature ranged between 20°C and 25°C. Skin fragments were collected immediately after euthanasia and subsequently at regular intervals of one hour for a total period of 11 hours, resulting in twelve collection time points (0 h, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 5 h, 6 h, 7 h, 8 h, 9 h, 10 h, and 11 h). Samples were collected from the inner thigh region, which had been previously shaved and disinfected using 70% ethanol. Excised skin fragments measured approximately 2 cm² and were immediately immersed in McCoy’s solution (Sigma M4892) supplemented with a high concentration of antibiotics (500 mg/L gentamicin and 20 mg/L amphotericin B).

Upon arrival at the laboratory, each skin sample was divided into two equal parts: one portion was used to assess cellular viability in fresh tissue, while the other was cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen for subsequent thawing and cell culture procedures. The cultures were maintained until cell confluence and chromosomes preparations were obtained to assess the number of metaphases per cell, based on analysis of the mitotic index, as described below.

Cell Viability

Upon arrival at the laboratory, skin fragments stored in McCoy’s solution were handled under laminar flow and washed with PBS. For cell viability analysis, tissue fragments were mechanically minced into ~1 mm³ pieces in a dish containing 3 mL of collagenase (1 mg/mL) diluted in DMEM. The digestion was performed in a 5% CO₂ incubator at 37°C for 30 minutes, with manual agitation every 5 minutes. The content was centrifuged at 200g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant discarded. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 4.5 mL of DMEM for viability assessment.

To determine cell viability, a 50 µL aliquot of the cell suspension was mixed with 50 µL of 0.4% Trypan Blue (Gibco, 1:1 dilution). After mixing, the cell suspension was loaded into a Neubauer counting chamber and examined under a light microscope at 10x magnification. Viable (unstained) and non-viable (blue-stained) cells were counted in the four quadrants [

17]. The total number of viable cells was calculated using the formula:

where the mean refers to the average of cells in quadrants A, B, C, and D; 10,000 is the conversion factor per mL; 2 accounts for dilution (50 µL Trypan Blue + 50 µL cell suspension); and 4.5 is the total volume of DMEM used for resuspension [

17]. Cell viability (%) was calculated as follows:

Cell viability = (Viable cells / Total cells [viable + non-viable]) × 100 [

17].

Cryopreservation of Skin Fragments

For cryopreservation, each skin fragment was washed three times in PBS and divided into five equal parts. Each piece was placed in a cryotube containing 1.0 mL of freezing medium (McCoy’s medium supplemented with 20% inactivated equine serum, 6.25% DMSO, 100 mg/mL PVP, 4.25 µL gentamicin, and 8.5 µL amphotericin B) [

18]. Tubes were stored at 4°C for 3.5 hours, then exposed to liquid nitrogen vapor (2 cm above the liquid surface) for 30 minutes, and finally immersed in liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

Thawing and Cell Culture of Cryopreserved Fragments

Thawing of cryopreserved fragments was performed by transferring the cryotube from liquid nitrogen directly into a 37°C water bath for about 1 minute and a half until the freezing medium was completely liquefied. The fragment was then manipulated under laminar flow, washed three times with PBS, and mechanically minced into ~1 mm³ pieces in a Petri dish containing 1 mL of DMEM and 1 mL of fetal bovine serum (FBS). Fragments were transferred to culture flasks and supplemented with 1.0 mL of DMEM medium enriched with 50% FBS, 50 mg/L gentamicin sulfate, and 2 mg/L amphotericin B. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere and maintained without disturbance for 48 hours [

19].

After that, cultures were monitored daily and medium changes occurred every 48 hours. Cell proliferation and confluence were subjectively evaluated based on the rate of cell expansion within the culture flask and cell morphology, using an inverted optical microscope, until 100% confluence was reached. All evaluations were performed by two independent, blinded observers who were unaware of the animal source or time point of the samples under examination.

Cell Harvesting

Once cultures reached full confluence, cells were treated with 60 µL of 0.016% colchicine for 30 minutes at 37°C. Afterward, cells were detached using 0.25% trypsin and centrifuged at 200g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet resuspended in 5 mL of hypotonic KCl solution (0.067 M) for 20 minutes at 37°C. The cell pellet was then fixed with 5 mL of Carnoy’s fixative (methanol:acetic acid, 3:1), centrifuged, and the fixation process repeated three times.

Mitotic Index Analysis

Fixed cells were dropped onto microscope slides and stained using conventional Giemsa staining. Slides were analyzed under brightfield microscopy using an Olympus BX60 microscope (100x objective) equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam MRm camera and AxioVision Release 4.8.2 software. For each culture, 1,000 cells were evaluated. The mitotic index (MI) was calculated as the ratio of metaphase cells to the total number of cells analyzed, expressed as a percentage [

20,

21].

Chromosomal Alteration Analysis

For each sampling time point, between 20 and 60 metaphases were analyzed using bright-field microscopy with an oil immersion objective lens (magnification: 1000×), in order to assess chromosomal stability based on the presence and number of chromosomal alterations observed per sample. The observed chromosomal alterations were counted and classified into the following categories: ring (A), dicentric chromosome (Dic), chromatid gap (Gct), chromosome gap (Gcr), chromatid break (Qct), chromosome break (Qcr), triradial figure (Ft), quadriradial figure (Fq), and rearrangement (Re) [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The number of chromosomal alterations was statistically evaluated using Tukey’s test, performed with the statistical software GraphPad Prism 7.0.

3. Results

3.1. Cell Viability of Fresh Tissues

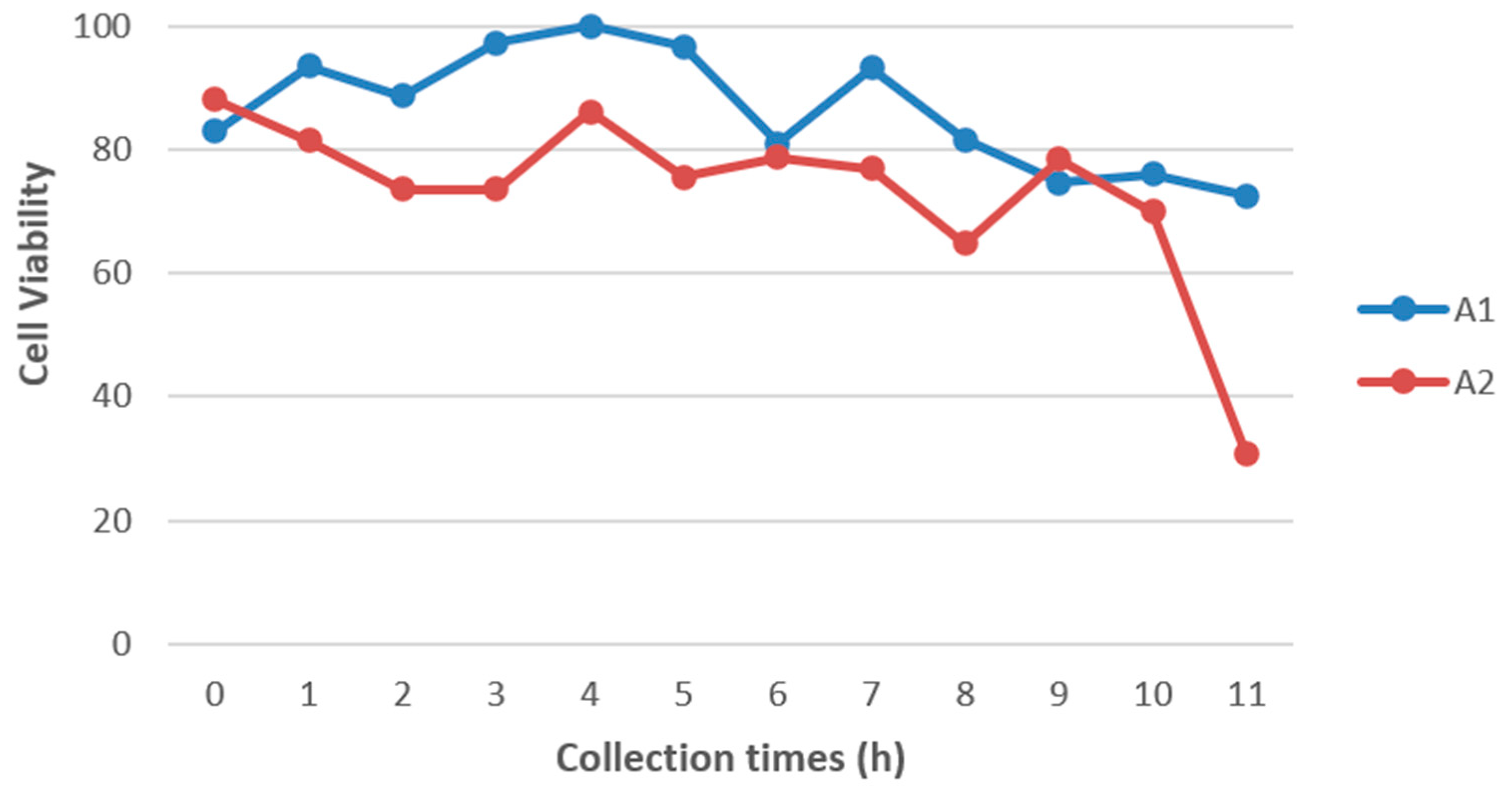

As expected, a decrease in the number of viable cells was observed over time after the death of both animals (

Figure 1). Tissues collected immediately after euthanasia showed cell viability greater than 80%. This number of viable cells slightly decreased in red brocket tissue collected after 11 hours, and the reduction was more pronounced in gray brocket tissue, where cell viability dropped below 40%. Although the number of viable cells at later time points was considerably lower than in the initial hours, the data indicate that it is still feasible to obtain viable cells from tissue fragments collected up to 11 hours postmortem.

Figure 1.

Cell viability of animal 1 (A1 – Mazama rufa) and animal 2 (A2 – Subulo gouazoubira) at different collection time points, expressed as a percentage.

Figure 1.

Cell viability of animal 1 (A1 – Mazama rufa) and animal 2 (A2 – Subulo gouazoubira) at different collection time points, expressed as a percentage.

3.2. Cryopreservation Methodology

Cryopreservation was carried out according to the methods used for Oliveira and collaborators [

13] and Sandoval and collaborators [

14]. The culture of cryopreserved skin fragments proved to be viable at all collection time points for both individuals evaluated in this study. Following thawing, the skin fragments were able to adhere to the bottom of the culture flasks, indicating that the cryopreservation protocol did not result in substantial damage to the tissue samples. Furthermore, these fragments demonstrated the capacity to resume cell division, as fibroblasts migrating from the tissue were observed to proliferate and spread throughout the culture surface.

3.3. Confluence Analysis of Cell Cultures Derived from Cryopreserved Skin Fragments

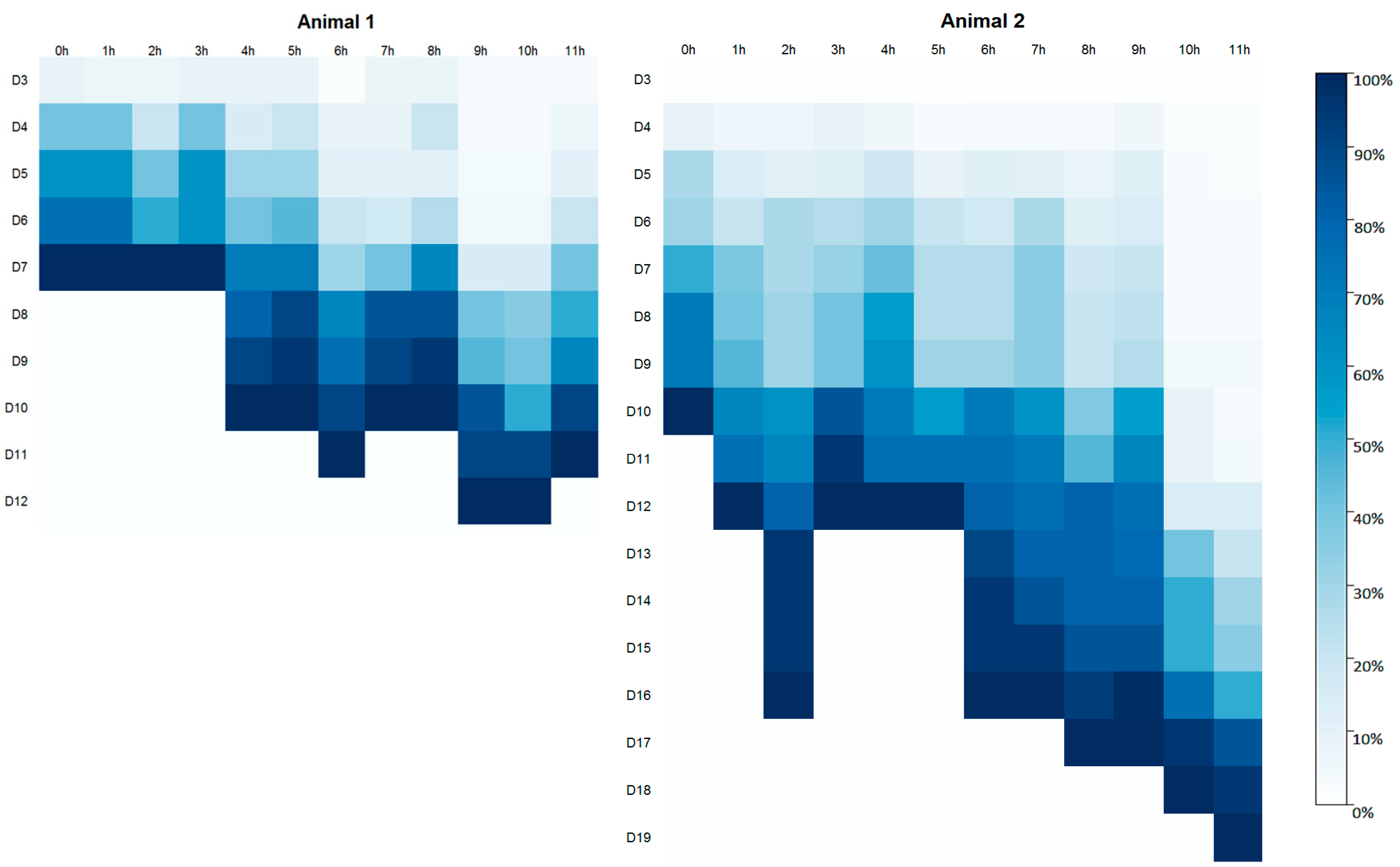

Confluence monitoring was conducted daily for all samples starting on day three (D3) after the initiation of cell culture. In Animal 1, tissue fragments adhered to the flask surface by the third day (D3), whereas in Animal 2, adherence was first observed on the fourth day (D4) (

Figure 2). Cell cultures from Animal 1 reached full confluence within a maximum of 12 days, which was notably shorter than the time required for Animal 2, in which cultures took up to 19 days to reach confluence (

Figure 2). In Animal 1, cell cultures established from samples collected within the first three hours postmortem reached full confluence simultaneously on the seventh day (D7) of cultivation. In contrast, for Animal 2, samples collected from the 1st to the 5th hour postmortem reached confluence by day 12 of culture, with the exception of the sample collected at two hours postmortem.

Figure 2.

Degree of cell confluence (%) in cultures derived from postmortem tissue samples of Animal 1 (Mazama rufa) and Animal 2 (Subulo gouazoubira). Cell cultures were evaluated daily, starting on the third day of culture (D3), until reaching 100% confluence. Tissue collection time points: 0 h, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 5 h, 6 h, 7 h, 8 h, 9 h, 10 h, and 11 h. Right panel: color bar indicates cell confluence percentage, ranging from 0% (white) to 100% (dark blue).

Figure 2.

Degree of cell confluence (%) in cultures derived from postmortem tissue samples of Animal 1 (Mazama rufa) and Animal 2 (Subulo gouazoubira). Cell cultures were evaluated daily, starting on the third day of culture (D3), until reaching 100% confluence. Tissue collection time points: 0 h, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 5 h, 6 h, 7 h, 8 h, 9 h, 10 h, and 11 h. Right panel: color bar indicates cell confluence percentage, ranging from 0% (white) to 100% (dark blue).

3.4. Mitotic Index Analysis

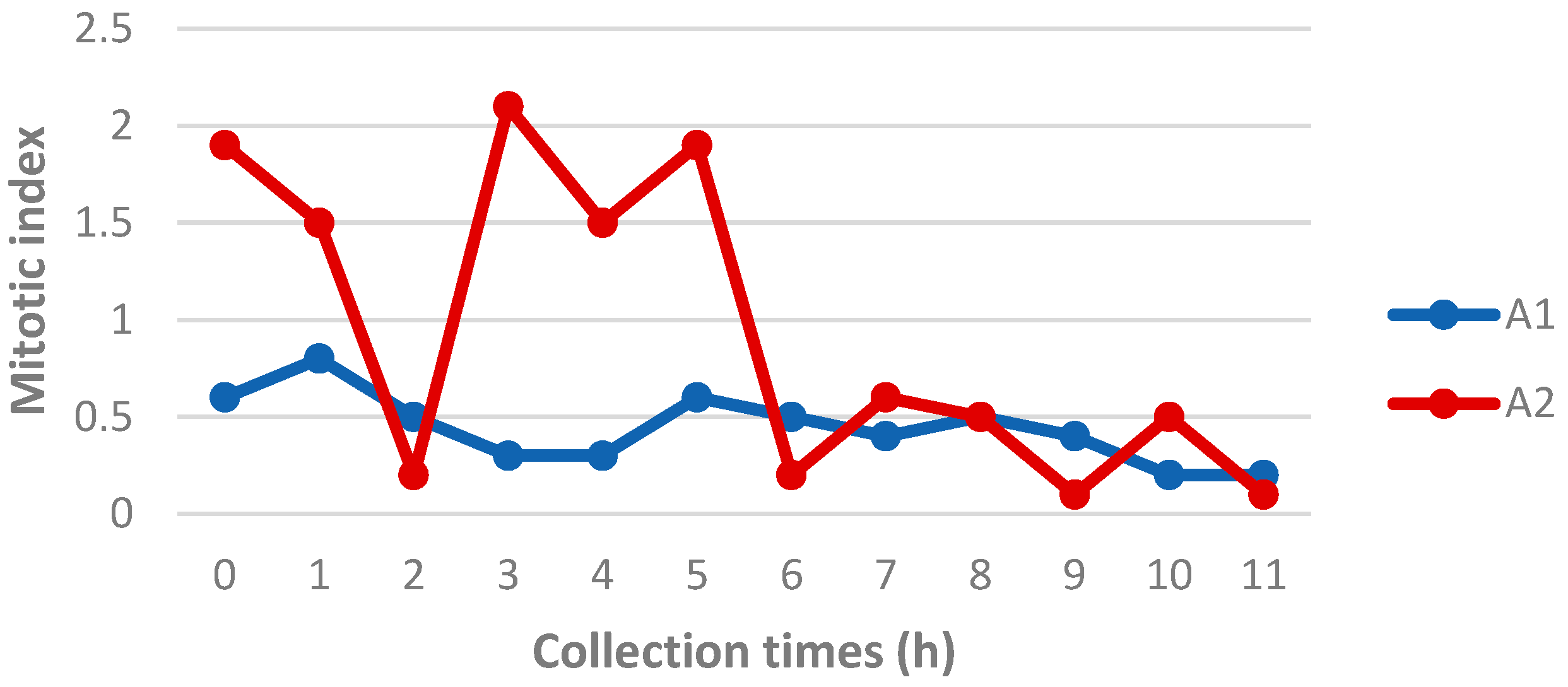

Mitotic index analysis revealed that Animal 2 generally exhibited a higher number of metaphases compared to Animal 1 (

Figure 3). This difference was most evident in the samples collected up to 5 h postmortem. After this time point, the number of metaphases in Animal 2 declined significantly, approaching the values observed in Animal 1. For Animal 2, a marked decrease in metaphase count was observed in the sample collected 2 hours postmortem. Considering that this same sample also showed delayed confluence, as previously reported, it is possible that a specific issue occurred during its processing, negatively affecting sample quality.

Figure 3.

Mitotic index of Animal 1 (Mazama rufa) and Animal 2 (Subulo gouazoubira) at different postmortem collection times.

Figure 3.

Mitotic index of Animal 1 (Mazama rufa) and Animal 2 (Subulo gouazoubira) at different postmortem collection times.

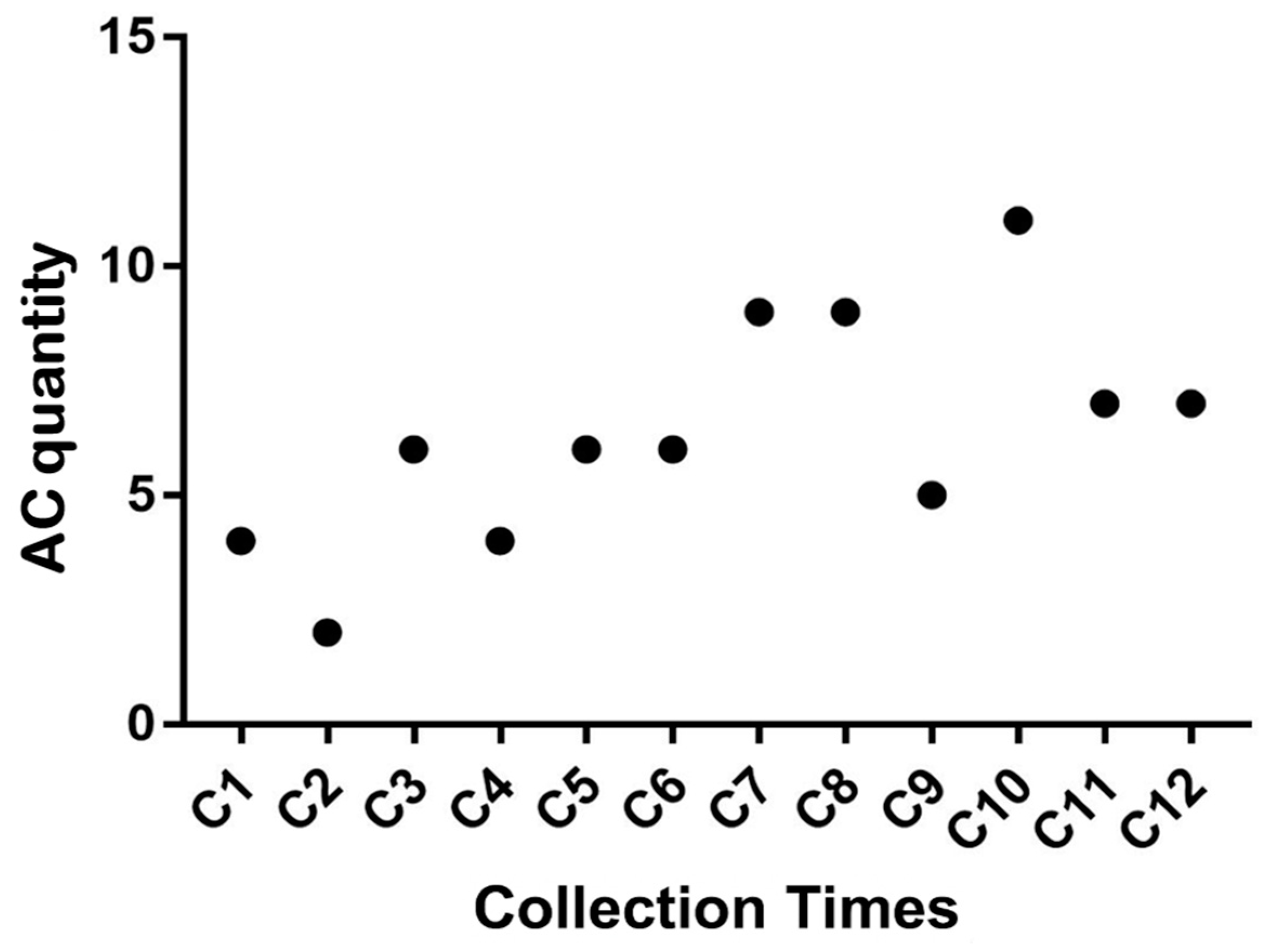

3.5. Chromosomal Alteration Analysis

A total of 780 metaphases were analyzed to assess chromosomal stability based on the presence and frequency of chromosomal alterations observed in each sampling time point. Among the nine types of chromosomal alterations evaluated, only four were detected: Gct, Gcr, Qct, and Qcr. The most frequently observed alteration was Gct, followed by Qct, Qcr, and Gcr, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 4, although a gradual increase in the average number of chromosomal alterations was observed in both Animal 1 and Animal 2 as the postmortem interval increased—particularly after the sixth collection point (5 hours postmortem)—these differences were not statistically significant. This result suggests that chromosomal structures remain stable for up to 11 hours after the animal's death.

Figure 4.

Average number of chromosomal alterations (ACs) observed at different sampling time points.

Figure 4.

Average number of chromosomal alterations (ACs) observed at different sampling time points.

Although it is possible to obtain viable tissue suitable for cryopreservation, subsequent thawing, and use in cytogenetic studies up to 11 h postmortem, the data presented herein suggest that the highest rates of cell viability, shortest time to reach confluence, greatest number of metaphases per cell (mitotic index), and highest chromosomal stability are achieved when skin fragments are collected within the first 5 hours postmortem.

4. Discussion

The collection of tissue samples from animals postmortem represents a valuable opportunity to preserve the genetic material of individuals, particularly those of rare or elusive species. In Brazil, it is estimated that approximately 475 million animals are killed annually on roads, equating to 15 roadkill incidents per second [

26]. Specific studies conducted in the state of São Paulo estimate an average of 0.6 medium- to large-sized mammals killed per kilometer per year on toll roads over a ten-year monitoring period [

27]. These figures support the potential significance of postmortem sampling in roadkill cases as a means of contributing to the maintenance of genetic diversity in cryobanks. Therefore, implementing policies that encourage highway concessionaires to collect animal carcasses could provide an efficient pathway for acquiring samples from forest-dwelling and elusive species, such as many neotropical deer.

Since death results in the cessation of blood circulation and subsequent oxygen deprivation, a cascade of tissue degradation begins [

28]. In this study, the analysis of freshly collected tissue allowed for the evaluation of sample quality, as low viability would significantly compromise the effectiveness of cryopreservation. Trypan Blue staining remains the most commonly used method to differentiate viable from non-viable cells and serves as a proxy for the proliferative capacity of a given sample [

29,

30,

31].

Upon evaluating cellular viability in samples collected at different postmortem intervals, it was observed that most samples from Animal 1 (M. rufa) exhibited a higher number of viable cells compared to those from Animal 2 (S. gouazoubira). This observation may be attributed to individual variation or possibly species-specific traits, as M. rufa typically has noticeably thicker skin than S. gouazoubira.

Fibroblasts began to migrate out from the skin fragments between the third day (Animal 1) and the fourth day (Animal 2) of culture, a timeframe consistent with previous studies on fibroblast outgrowth from Neotropical deer skin tissues [

13,

14,

15]. Regarding the time to reach full confluence, all cultures achieved 100% confluence within a timeframe comparable to that typically observed for brocket deer fibroblasts derived from in vivo-collected samples that were immediately cryopreserved and later thawed for culture [

13].

Previous studies have demonstrated that viable and cultivable cells can be obtained up to 10 days after the death of animals such as sheep, rabbits, and goats. However, these studies involved samples stored under controlled and sterile conditions at room temperature [

15,

32,

33,

34]. In contrast, this study demonstrated the presence of viable cells and sterility in cultured fibroblast lines up to 11 hours postmortem, under field conditions without temperature control or sterile handling, thus simulating a scenario found in nature.

Mitotic index analysis was used to morphologically assess cell cycle stages, quantifying the number of cells reaching metaphase during mitosis [

20]. However, the maximum mitotic potential may not have been fully represented in this experiment, as cultures were harvested only upon reaching 100% confluence—a point at which cellular proliferation generally begins to decline [

20,

35]. Given that fibroblasts proliferate rapidly and are capable of reaching adequate mitotic indices, it was unnecessary to use mitogens to stimulate cell division in order to obtain a moderate number of metaphases [

29].

Cytogenetic analyses provide insight into whether postmortem cellular degradation affects chromosomal structure and stability through the observation of chromosomal alterations [

32]. Some of the alterations observed in this study may not necessarily be associated with postmortem degradation but could instead reflect inherent chromosomal fragility reported in some Neotropical deer species [

25,

36]. Nevertheless, although chromosomal alterations were detected in some metaphases, their frequency did not differ significantly among samples collected at different time points. This finding indicates that stable, intact chromosomes can still be obtained up to 11 h postmortem.

Both the number of viable cells and the mitotic index declined progressively with increasing postmortem interval, consistent with the gradual death of skin cells—including adult stem cells, which are responsible for rapid cellular proliferation [

15]. The aforementioned oxygen deprivation results in progressive tissue decomposition due to lysosomal enzyme activity [

15]. Therefore, this study suggests that optimal results are achieved when skin samples from

M. rufa and

S. gouazoubira are collected within 5 h postmortem under uncontrolled environmental conditions of temperature and sterility.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that cells obtained from postmortem animal tissue remain chromosomally stable, making them suitable for cytogenetic analyses. Based on the combined analysis of the data presented in this study, it can be concluded that fibroblast cell lines can be successfully established from skin tissue collected up to 11 h postmortem from animals kept under non-controlled temperature conditions and without aseptic procedures. However, based on higher cell viability rates, shorter time to reach confluence, and greater numbers of metaphases per cell (mitotic index), it is suggested that optimal results can be achieved when skin fragments are collected within 5 h postmortem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.T. and J.M.B.D.; methodology, I.M.T.; formal analysis, L.D.R. and I.M.T.; investigation, L.D.R., I.M.T., E.D.P.S., J.A.M. and S.H.S.B..; resources, J.M.B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.R and I.M.T.; writing—review and editing, L.D.R, I.M.T., E.D.P.S; visualization, L.D.R., I.M.T., E.D.P.S., J.A.M., S.H.S.B and J.M.B.D.; supervision, J.M.B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) process n◦ 2017/07014-8.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics and Animal Welfare Committee (CEBEA) of the Faculty of Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences (FCAV) of São Paulo State University (UNESP), Jaboticabal campus, under protocol Nº. 005433/19 approved 16/05/2019.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the collaboration of the other members of the Deer Research and Conservation Center, the laboratory technician João Boer for helping with the equipment and preparing solutions, and the animal caretakers, who kept them healthy and well-being until the time of euthanasia of the individuals. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCNT |

Somatic cell nuclear transfer |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| PVP |

Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| MI |

Mitotic Index |

| R |

Ring |

| Dic |

Dicentric chromosome |

| Gct |

Chromatid gap |

| Gcr |

Chromosome gap |

| Qct |

Chromatid break |

| Qcr |

Chromosome break |

| Ft |

Triradial figure |

| Fq |

Quadriradial figure |

| Re |

Rearrangement |

References

- Weber, M. , & Gonzalez, S.Latin American deer diversity and conservation: A review of status and distribution. Écoscience 2003, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, J.; Chanson, J.S.; Chiozza, F.; Cox, N.A.; Hoffmann, M.; Katariya, V.; Lamoreux, J.; Rodrigues, A.S.L.; Stuart, S.N.; Temple, H.J.; et al. The status of the world’s land and marine mammals: Diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 2008, 322, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Disponível em: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (acessado em 31 de março de 2025).

- Duarte, J.M.B. Coleta, conservação e multiplicação de recursos genéticos em animais silvestres: O exemplo dos cervídeos. Agrociencia 2005, 9, 541–544, Disponível em: http://www.fagro.edu.uy/agrociencia/index.php/directorio/article/view/344. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Rincón, A. , Morales-Donoso, J.A., Sandoval, E.D.P., Tomazella, I.M., Mantellatto, A.M.B., Thoisy, B., & Duarte, J.M.B. Designation of a neotype for Mazama americana (Artiodactyla, Cervidae) reveals a cryptic new complex of brocket deer species. ZooKeys 2020, 958, 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- González, S. , & Duarte, J.M.B. Speciation, evolutionary history and conservation trends of neotropical deer. Mastozoología Neotropical 2020, 27, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Abril, V.V. , Carnelossi, E.A., González, S., & Duarte, J.M.B. Elucidating the evolution of the red brocket deer Mazama americana complex (Artiodactyla; Cervidae). Cytogenetic and Genome Research 2010, 128, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, M.L.H. (2016). Filogenia molecular de Mazama americana (Artiodactyla: Cervidae) como auxílio na resolução das incertezas taxonômicas [Dissertação de mestrado, Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho]. Repositório Institucional UNESP. Disponível em: https://repositorio.unesp.br/handle/11449/142902.

- Ryder, O.A. , & Onuma, M. Viable cell culture banking for biodiversity characterization and conservation. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 2018, 6, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P. , & Holt, W. Breakthroughs and new horizons in reproductive biology of rare and endangered animal species. Biology of Reproduction 2019, 101, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, L.D. , Buzanskas, M.E., Melo, L.M., Chaves, M.S., Freitas, V.J.F., & Duarte, J.M.B. Assisted reproductive technology in neotropical deer: A model approach to preserving genetic diversity. Animals 2021, 11, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastromonaco, G.F. , & King, W.A. Cloning in companion animal, non-domestic and endangered species: Can the technology become a practical reality? Reproduction, Fertility and Development 2007, 19, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.C. , Vacari, G.Q., & Duarte, J.M.B. (2023). A method to freeze skin samples for cryobank: A test of some cryoprotectants for an endangered deer. Biopreservation and Biobanking.

- Sandoval, E.D.P. , & Duarte, J.M.B. (2025). Transport media for live skin tissue from gray-brocket deer (Subulo gouazoubira). Biopreservation and Biobanking. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. , & Ma, X. In vitro culture of fibroblast-like cells from sheep ear skin stored at 25–26ºC for 10 days after animal death. International Journal of Biology 2014, 6, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, J.M.B. , Uhart, M.M., & Galvez, C.E.S. (Eds.). (2020). Neotropical Cervidology: Biology and Medicine of Latin American Deer. Funep/IUCN.

- Louis, K.S. , & Siegel, A.C. (2011). Cell viability analysis using trypan blue: Manual and automated methods. In M. J. Stoddart (Ed.), Mammalian Cell Viability: Methods and Protocols (pp. 7–12). Humana Press.

- Duarte, J.M.B. , Ramalho, M.F.P.; Di, T., Lima, V.F.H. de, & Jorge, W. A leukocyte cryopreservation technique for cytogenetic studies. Genetics and Molecular Biology 1999, 22, 399–400. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, R.S. , & Babu, A. (1995). Human chromosomes: principles and techniques (2nd ed., p. 419). McGraw-Hill.

- O'Connor, P.M. , Ferris, D.K., Pagano, M., Draetta, G., Pines, J., Hunter, T., Longo, D.L., & Kohn, K.W. G2 delay induced by nitrogen mustard in human cells affects cyclin A/cdk2 and cyclin B1/cdc2-kinase complexes differently. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 1993, 268, 8298–8308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galloway, S.M. , Aardema, M.J., Ishidate, M. Jr., Ivett, J.L., Kirkland, D.J., Morita, T., Moses, P., & Sofuni, T. Report from working group on in vitro tests for chromosomal aberrations. Mutation Research 1994, 312, 241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, H.J. , & O'Riordan, M.L. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes for the analysis of chromosome aberrations in mutagen tests. Mutation Research 1975, 31, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, J.R.K. Classification and relationships of induced chromosomal structural changes. Journal of Medical Genetics 1975, 12, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, J.R.K. , & Simpson, P. J. FISH "painting" patterns resulting from complex exchanges. Mutation Research 1994, 312, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tomazella, I.M. , Abril, V.V., & Duarte, J.M.B. Identifying Mazama gouazoubira (Artiodactyla; Cervidae) chromosomes involved in rearrangements induced by doxorubicin. Genetics and Molecular Biology 2017, 40, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Centro Brasileiro de Ecologia de Estradas (CBEE). (2019). Atropelômetro. Disponível em: http://cbee.ufla.br/portal/atropelometro/ (Acessado em 14 março 2024). 2024.

- Abra, F.D. , Huijser, M.P., Magioli, M., Bovo, A.A.A., & de Barros, K.M.P.M. An estimate of wild mammal roadkill in São Paulo state, Brazil. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, M. Ultrastructural changes of renal epithelial cells during post-mortem autolysis—experimental work. Med Pregl 2010, 63, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegg, D.E. Viability assays for preserved cells, tissues and organs. Cryobiology 1989, 26, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartford, J.B. (1998). Cell culture. In J. S. Bonifacino, J.B. Hartford, J. Lippincott-Schwartz, & K. M. Yamada (Eds.), Current Protocols in Cell Biology (pp. 1.0.1–1.0.2). John Wiley & Sons.

- Stoddart, M.J. (2011). Cell viability assays: Introduction. In M. J. Stoddart (Ed.), Mammalian Cell Viability: Methods and Protocols (pp. 1–6). Humana Press.

- Silvestre, M.A. , Saeed, A.M., Cervera, R.P., Escriba, M.J., & Garcia-Ximenez, F. Rabbit and pig ear skin sample cryobanking: Effects of storage time and temperature of the whole ear extirpated immediately after death. Theriogenology 2003, 59, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silvestre, M.A. , Sanchez, J.P., & Gomez, E.A. Vitrification of goat, sheep, and cattle skin samples from whole ear extirpated after death and maintained at different storage times and temperatures. Cryobiology 2004, 49, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M. , Ma, X., & Sharma, A. Effect of postmortem time interval on in vitro culture potential of goat skin tissues stored at room temperature. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology – Animal 2012, 48, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Jackman, J. , & O'Connor, P.M. (1998). Methods for synchronizing cells at specific stages of the cell cycle. In J. S. Bonifacino, J.B. Hartford, J. Lippincott-Schwartz, & K. M. Yamada (Eds.), Current Protocols in Cell Biology (pp. 8.3.1–8.3.20). John Wiley & Sons.

- Vargas-Munar, D.S.F. (2003). Relação entre fragilidade cromossômica e trocas entre cromátides irmãs com a variabilidade cariotípica de cervídeos brasileiros [Dissertação de Mestrado, Faculdade de Ciências Agrárias e Veterinárias]. Universidade Estadual Paulista ― Júlio de Mesquita Filho.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).