Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

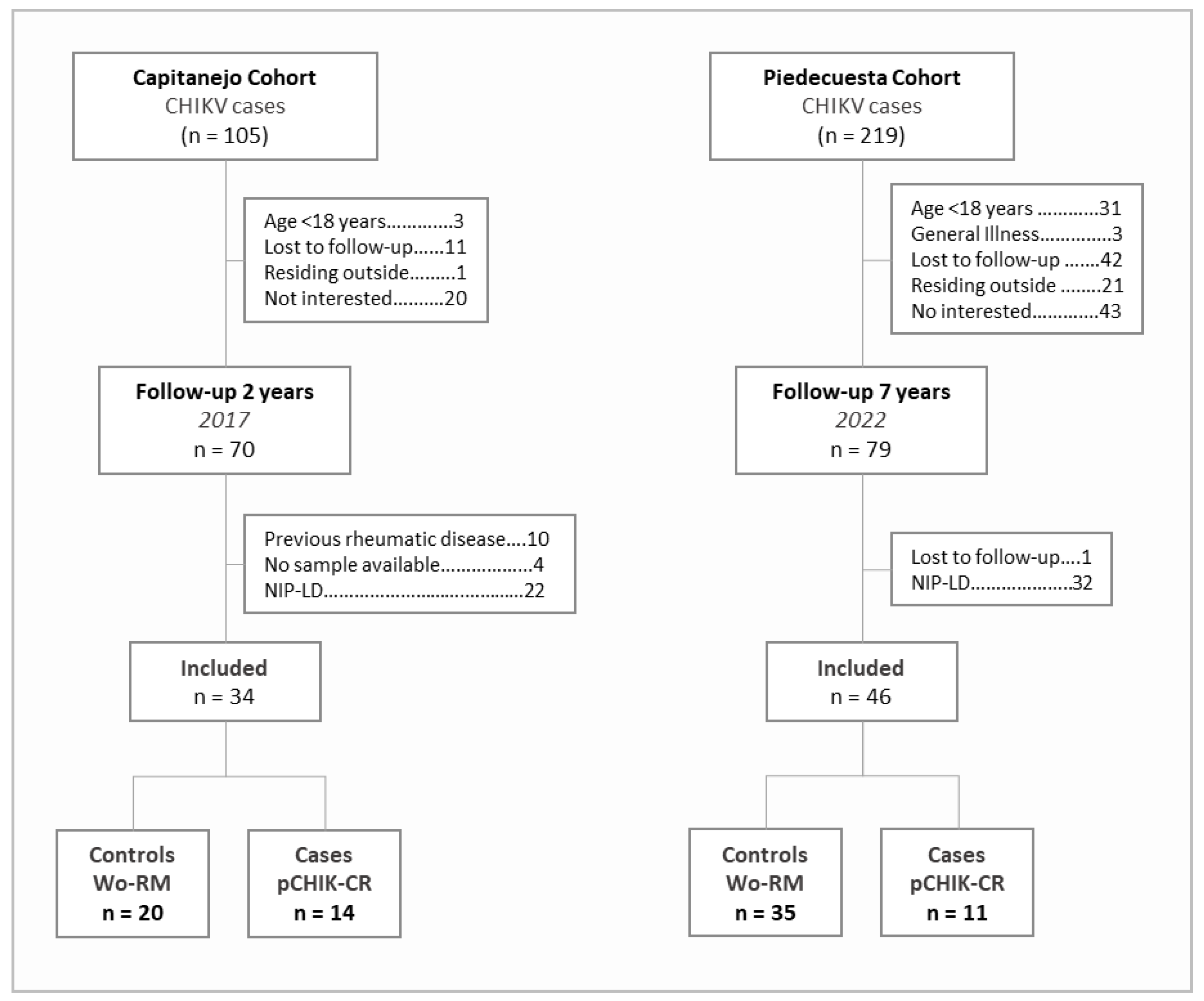

2.1. Description of Cohorts

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Case-Control Definition

2.4. Immunological Factor Assays

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

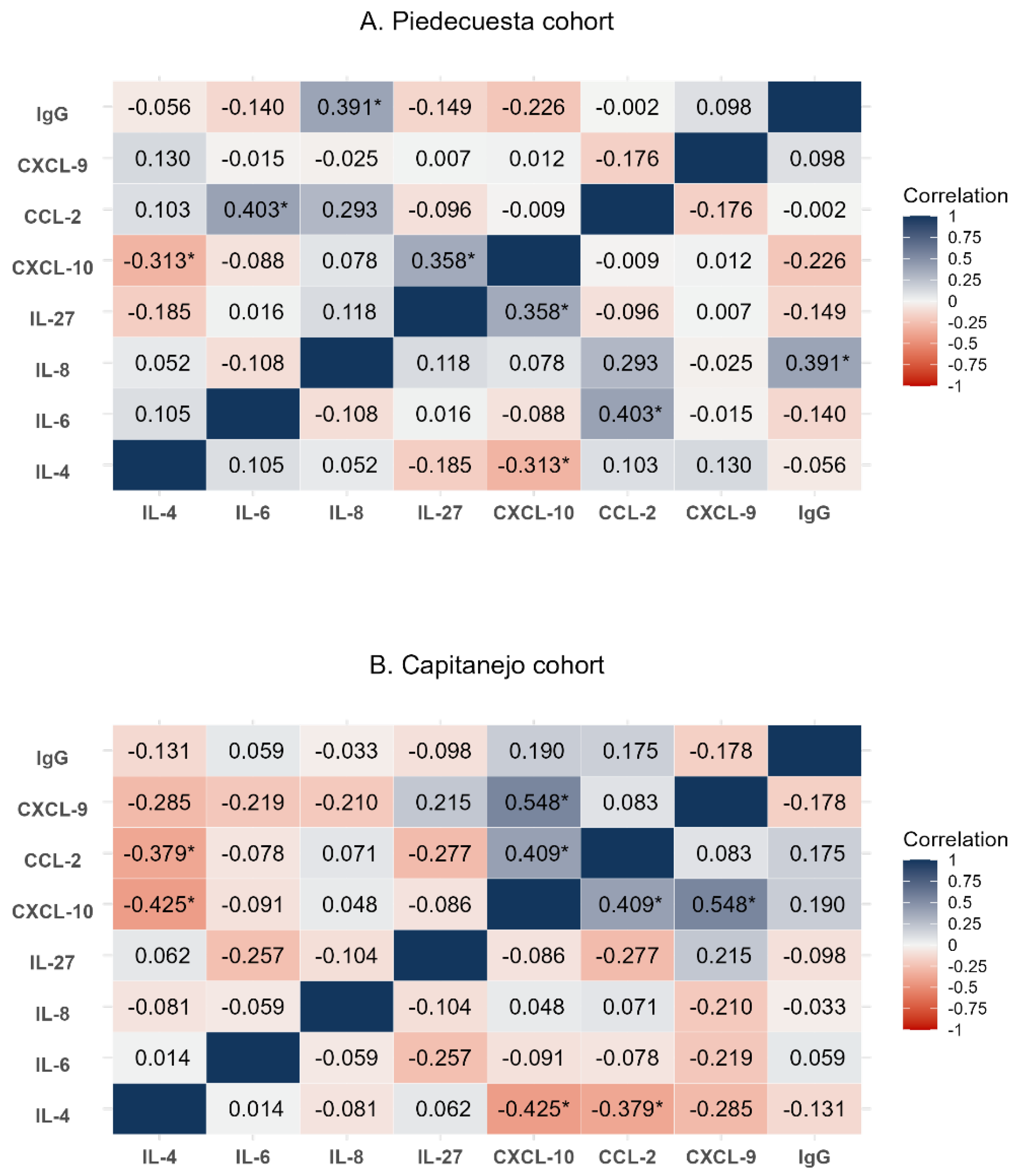

3.2. Quantification and correlation of immunological factors

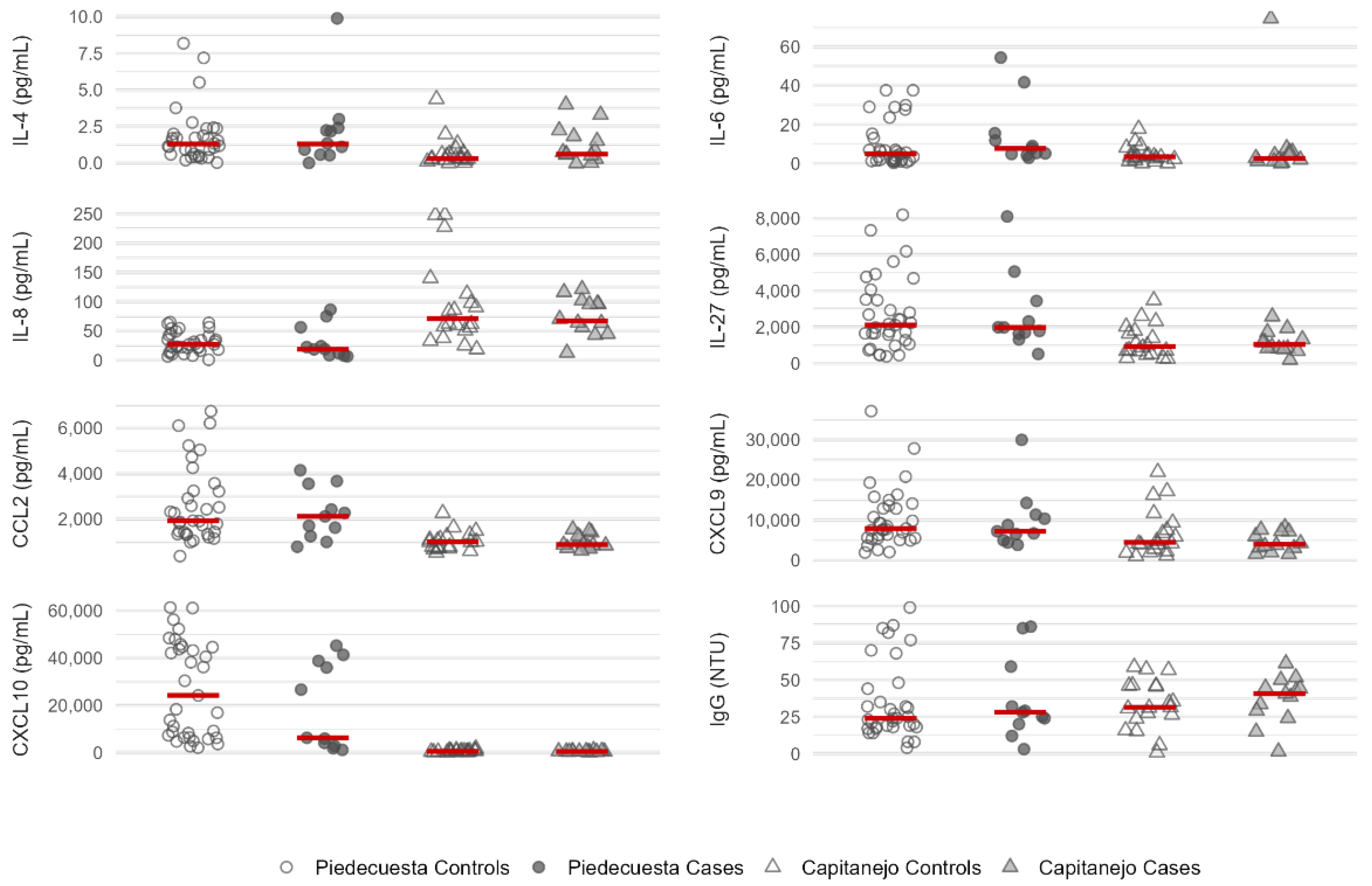

3.3. Quantification of immunological factors by case-control status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

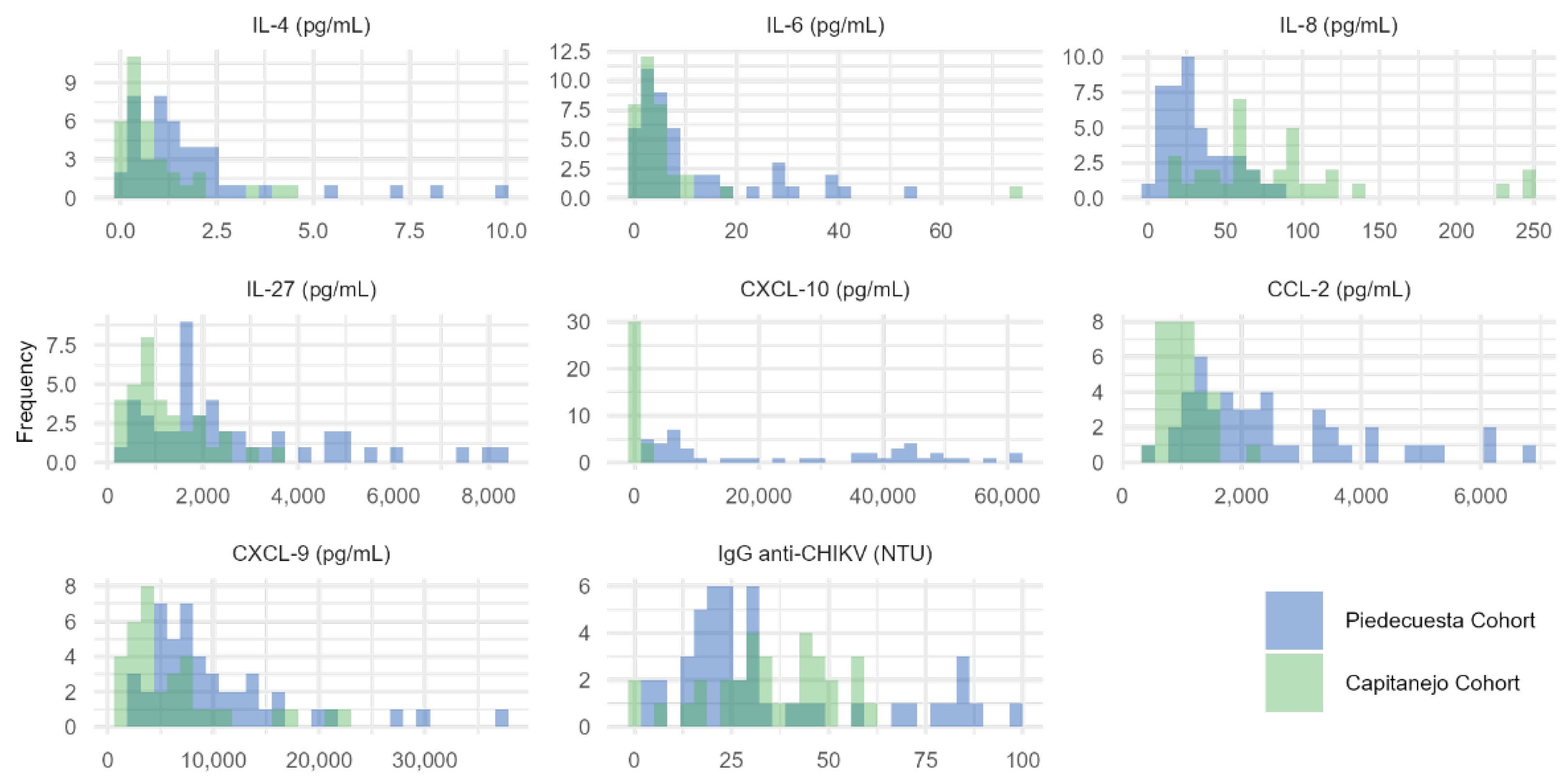

Appendix A.1. Histograms of the concentration of immunological factors quantified in each cohort.

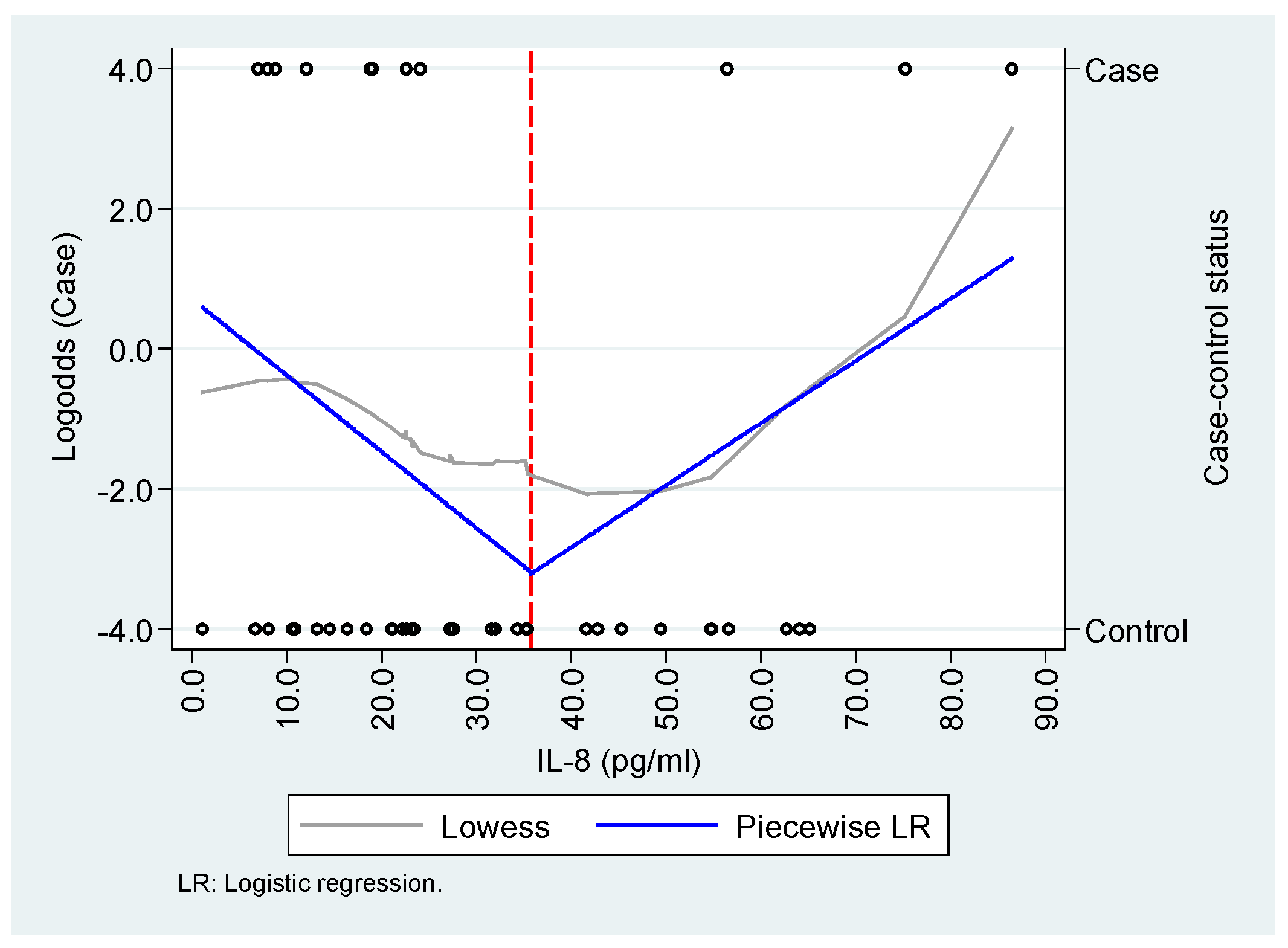

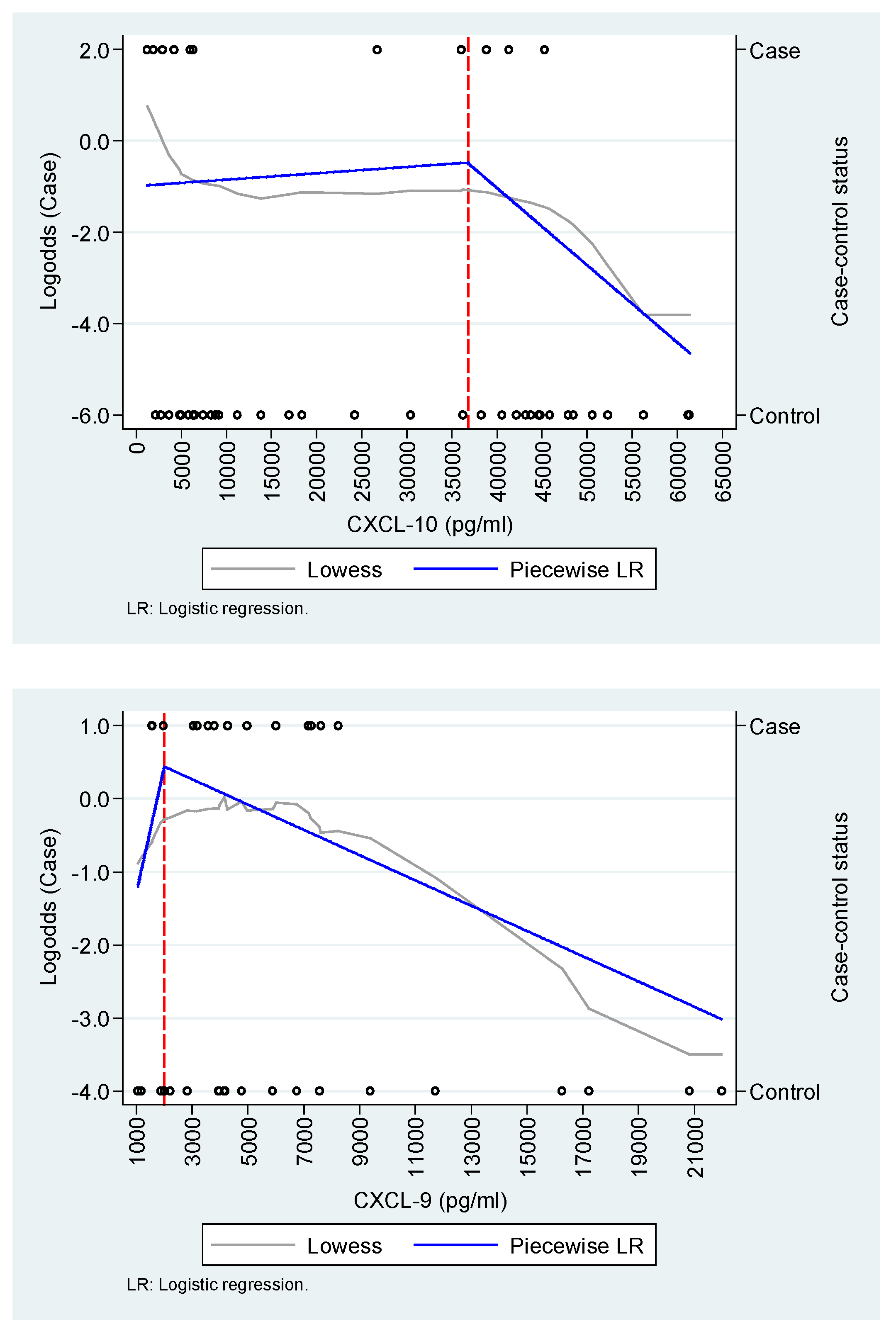

Appendix A.2. Exploration of the functional relationship between IL-8/CXCL-8, CXCL-9, and CXCL-10 and the case-control status.

References

- Valdés López, J.F.; Velilla, P.A.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Chikungunya Virus and Zika Virus, Two Different Viruses Examined with a Common Aim: Role of Pattern Recognition Receptors on the Inflammatory Response. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research 2019. [CrossRef]

- Constant, L.E.C.; Rajsfus, B.F.; Carneiro, P.H.; Sisnande, T.; Mohana-Borges, R.; Allonso, D. Overview on Chikungunya Virus Infection: From Epidemiology to State-of-the-Art Experimental Models. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhrymuk, I.; Kulemzin, S. V.; Frolova, E.I. Evasion of the Innate Immune Response: The Old World Alphavirus NsP2 Protein Induces Rapid Degradation of Rpb1, a Catalytic Subunit of RNA Polymerase II. J Virol 2012, 86, 7180–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.A.; Dermody, T.S. Chikungunya Virus: Epidemiology, Replication, Disease Mechanisms, and Prospective Intervention Strategies. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud Preparación y Respuesta Ante La Eventual Introducción Del Virus Chikungunya En Las Américas 2011.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud Chikungunya. Nota Descriptiva. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs327/es/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Tanabe, I.S.B.; Tanabe, E.L.L.; Santos, E.C.; Martins, W. V.; Araújo, I.M.T.C.; Cavalcante, M.C.A.; Lima, A.R. V.; Câmara, N.O.S.; Anderson, L.; Yunusov, D.; et al. Cellular and Molecular Immune Response to Chikungunya Virus Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharz, E.J.; Cebula-Byrska, I. Chikungunya Fever. Eur J Intern Med 2012, 23, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Rodríguez, M.A. Evaluación de Las Manifestaciones Reumatológicas y Las Alteraciones Paraclínicas Luego de Dos Años de La Presentación de La Infección Por Virus de Chikungunya En Un Brote En El Municipio de Capitanejo, Santander. [Tesis de Especialización En Medicina Interna], Universidad Industrial de Santander, 2018.

- Thiberville, S.D.; Moyen, N.; Dupuis-Maguiraga, L.; Nougairede, A.; Gould, E.A.; Roques, P.; de Lamballerie, X. Chikungunya Fever: Epidemiology, Clinical Syndrome, Pathogenesis and Therapy. Antiviral Res 2013, 99, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.; Javelle, E.; Cabie, A.; Bouquillard, E.; Troisgros, O.; Gentile, G.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Hoen, B.; Gandjbakhch, F.; Rene-Corail, P.; et al. French Guidelines for the Management of Chikungunya (Acute and Persistent Presentations). November 2014. Med Mal Infect 2015, 45, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Charry, J.S.; Parada-Martinez, M.A.; Segura-Puello, H.R.; Muñoz-Forero, D.M.; Nieto-Mosquera, D.L.; Villamil-Ballesteros, A.C.; Cortés-Muñoz, A.J. Musculoskeletal Disorders Due to Chikungunya Virus: A Real Experience in a Rheumatology Department in Neiva, Huila. Reumatol Clin 2021, 17, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumahoro, M.K.; Gérardin, P.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Perrau, J.; Fianu, A.; Pouchot, J.; Malvy, D.; Flahault, A.; Favier, F.; Hanslik, T. Impact of Chikungunya Virus Infection on Health Status and Quality of Life: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.; Malaisamy, M.; Ponnaiah, M.; Kaliaperuaml, K.; Vadivoo, S.; Gupte, M.D. Impact of Chikungunya on Health Related Quality of Life Chennai, South India. PLoS One 2012, 7, e51519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, E.; Guillemin, F.; Mura, M.; Léon, L.; Virion, J.M.; Letort, M.J.; De valk, H.; Simon, F.; Vaillant, V. Impaired Quality of Life after Chikungunya Virus Infection: A 2-Year Follow-up Study. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 2012, 51, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsinga, J.; Gerstenbluth, I.; Van Der Ploeg, S.; Halabi, Y.; Lourents, N.T.; Burgerhof, J.G.; Van Der Veen, H.T.; Bailey, A.; Grobusch, M.P.; Tami, A. Long-Term Chikungunya Sequelae in Curaçao: Burden, Determinants, and a Novel Classification Tool. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2017, 216, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marimoutou, C.; Ferraro, J.; Javelle, E.; Deparis, X.; Simon, F. Chikungunya Infection: Self-Reported Rheumatic Morbidity and Impaired Quality of Life Persist 6 Years Later. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2015, 21, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvignaud, A.; Fianu, A.; Bertolotti, A.; Jaubert, J.; Michault, A.; Poubeau, P.; Fred, A.; Méchain, M.; Gaüzère, B.A.; Favier, F.; et al. Rheumatism and Chronic Fatigue, the Two Facets of Post-Chikungunya Disease: The TELECHIK Cohort Study on Reunion Island. Epidemiol Infect 2018, 146, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérardin, P.; Fianu, A.; Malvy, D.; Mussard, C.; Boussaïd, K.; Rollot, O.; Michault, A.; Gaüzere, B.A.; Bréart, G.; Favier, F. Perceived Morbidity and Community Burden after a Chikungunya Outbreak: The TELECHIK Survey, a Population-Based Cohort Study. BMC Med 2011, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manimunda, S.P.; Vijayachari, P.; Uppoor, R.; Sugunan, A.P.; Singh, S.S.; Rai, S.K.; Sudeep, A.B.; Muruganandam, N.; Chaitanya, I.K.; Guruprasad, D.R. Clinical Progression of Chikungunya Fever during Acute and Chronic Arthritic Stages and the Changes in Joint Morphology as Revealed by Imaging. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2010, 104, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Parra, A.; Herrera, V.; Calderón, C.; Badillo, R.; Gélvez Ramírez, R.M.; Estupiñán Cárdenas, M.I.; Lozano Jiménez, J.F.; Villar, L.Á.; Rojas Garrido, E.M. Chronic Rheumatologic Disease in Chikungunya Virus Fever: Results from a Cohort Study Conducted in Piedecuesta, Colombia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2024, Vol. 9, Page 247 2024, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, M.L.; Grilli, E.; Corvetta, A.; Silvi, G.; Angelini, R.; Mascella, F.; Miserocchi, F.; Sambo, P.; Finarelli, A.C.; Sambri, V.; et al. Long-Term Chikungunya Infection Clinical Manifestations after an Outbreak in Italy: A Prognostic Cohort Study. Journal of Infection 2012, 65, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérardin, P.; Fianu, A.; Michault, A.; Mussard, C.; Boussaïd, K.; Rollot, O.; Grivard, P.; Kassab, S.; Bouquillard, E.; Borgherini, G.; et al. Predictors of Chikungunya Rheumatism: A Prognostic Survey Ancillary to the TELECHIK Cohort Study. Arthritis Res Ther 2013, 15, R9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Fernandez, G.J.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Synergistic Effects of Toll-Like Receptor 1/2 and Toll-Like Receptor 3 Signaling Triggering Interleukin 27 Gene Expression in Chikungunya Virus-Infected Macrophages. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 812110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, O.; Albert, M.L. Biology and Pathogenesis of Chikungunya Virus. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2010 8:7 2010, 8, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Fernandez, G.J.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Interleukin 27 as an Inducer of Antiviral Response against Chikungunya Virus Infection in Human Macrophages. Cell Immunol 2021, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoarau, J.J.; Jaffar Bandjee, M.C.; Krejbich Trotot, P.; Das, T.; Li-Pat-Yuen, G.; Dassa, B.; Denizot, M.; Guichard, E.; Ribera, A.; Henni, T.; et al. Persistent Chronic Inflammation and Infection by Chikungunya Arthritogenic Alphavirus in Spite of a Robust Host Immune Response. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 184, 5914–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Brito, M.S.A.G.; de Marchi, M.S.; Perin, M.Y.; Côsso, I. da S.; Bumlai, R.U.M.; Júnior, W.V. da S.; Prado, A.Y.M.; da Cruz, T.C.D.; Avila, E.T.P.; Damazo, A.S.; et al. Inflammation, Fibrosis and E1 Glycoprotein Persistence in Joint Tissue of Patients with Post-Chikungunya Chronic Articular Disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2023, 56, e0278-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis-Maguiraga, L.; Noret, M.; Brun, S.; Le Grand, R.; Gras, G.; Roques, P. Chikungunya Disease: Infection-Associated Markers from the Acute to the Chronic Phase of Arbovirus-Induced Arthralgia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Parra, A.; Herrera, V.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S.; Ramírez, R.M.G.; Villar, L.Á. Acute Immunological Profile and Prognostic Biomarkers of Persistent Joint Pain in Chikungunya Fever: A Systematic Review. Yale J Biol Med 2024, 97, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabali, M.; Lim, J.K.; Palencia, D.C.; Lozano-Parra, A.; Gelvez, R.M.; Lee, K.S.; Florez, J.P.; Herrera, V.M.; Kaufman, J.S.; Rojas, E.M.; et al. Burden of Dengue among Febrile Patients at the Time of Chikungunya Introduction in Piedecuesta, Colombia. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2018, 23, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñán Cardenas, M.I.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Gélvez, R.M.; Herrera, V.; Lozano, A.; Vanhomwegen, J.; Salje, H.; Manuguerra, J.-C.; Cummings, D.A.; Miranda, M.C.; et al. Endemicity and Emergence of Arboviruses in Piedecuesta, Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018, 99, 512–512. [Google Scholar]

- Riel, P.L.C.M. van.; Gestel, A.M. van.; Scott, D.L. Eular Handbook of Clinical Assessments in Rheumatoid Arthritis. 2000.

- Dacre, J. The GALS Screen: The Rapid Rheumatological Exam. Medical Journal of Australia 2019, 210, 396–397.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Real Time RT-PCR for Detection of Chikungunya Virus (SOP); Molecular Diagnostics and Research Laboratory, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, CDC Dengue Branch: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2014.

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O.; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 Rheumatoid Arthritis Classification Criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2010, 62, 2569–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudwaleit, M.; Van Der Heijde, D.; Landewé, R.; Akkoc, N.; Brandt, J.; Chou, C.T.; Dougados, M.; Huang, F.; Gu, J.; Kirazli, Y.; et al. The Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society Classification Criteria for Peripheral Spondyloarthritis and for Spondyloarthritis in General. Ann Rheum Dis 2011, 70, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aringer, M.; Costenbader, K.; Daikh, D.; Brinks, R.; Mosca, M.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Smolen, J.S.; Wofsy, D.; Boumpas, D.T.; Kamen, D.L.; et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019, 78, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Riel, P.L.C.M.; van Gestel, A.M.; Scott, D.L. EULAR Handbook of Clinical Assessments in Rheumatoid Arthritis: On Behalf of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials -ESCISIT, 3rd ed.; Van Zuiden Communications B.V: Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands, 2004; ISBN 9789075141900. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Häuser, W.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B. Fibromyalgia Criteria and Severity Scales for Clinical and Epidemiological Studies: A Modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2011, 38, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, X.; Ribera, A.; Gasque, P. Chikungunya-Induced Arthritis in Reunion Island: A Long-Term Observational Follow-up Study Showing Frequently Persistent Joint Symptoms, Some Cases of Persistent Chikungunya Immunoglobulin M Positivity, and No Anticyclic Citrullinated Peptide Seroconversion after 13 Years. The Journal of Infectious Diseases ® 2020, 222, 1740–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Hernández-Sarmiento, L.J.; Tamayo-Molina, Y.S.; Velilla-Hernández, P.A.; Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Interleukin 27, like Interferons, Activates JAK-STAT Signaling and Promotes pro-Inflammatory and Antiviral States That Interfere with Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses Replication in Human Macrophages. Front Immunol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-López, J.F.; Hernández-Sarmiento, L.J.; Tamayo-Molina, Y.S.; Velilla-Hernández, P.A.; Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Urcuqui-Inchima, S. Interleukin 27, like Interferons, Activates JAK-STAT Signaling and Promotes pro-Inflammatory and Antiviral States That Interfere with Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses Replication in Human Macrophages. Front Immunol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushima, K.; Yang, D.; Oppenheim, J.J. Interleukin-8: An Evolving Chemokine. Cytokine 2022, 153, 155828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.H.; Lum, F.M.; Lee, W.W.L.; Ng, L.F.P. Mouse Models for Chikungunya Virus: Deciphering Immune Mechanisms Responsible for Disease and Pathology. Immunol Res 2012, 53, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson Sousa, F.; Ghaisani Komarudin, A.; Findlay-Greene, F.; Bowolaksono, A.; Sasmono, R.T.; Stevens, C.; Barlow, P.G. Evolution and Immunopathology of Chikungunya Virus Informs Therapeutic Development. Dis Model Mech 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, F.M.; Ng, L.F.P. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Chikungunya Pathogenesis. Antiviral Res 2015, 120, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, M.C.; Fox, L.E.; Dunlap, B.F.; Young, A.R.; Monte, K.; Lenschow, D.J. Interferon Alpha, but Not Interferon Beta, Acts Early To Control Chronic Chikungunya Virus Pathogenesis. J Virol 2022, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, L.E.; Locke, M.C.; Young, A.R.; Monte, K.; Hedberg, M.L.; Shimak, R.M.; Sheehan, K.C.F.; Veis, D.J.; Diamond, M.S.; Lenschow, D.J. Distinct Roles of Interferon Alpha and Beta in Controlling Chikungunya Virus Replication and Modulating Neutrophil-Mediated Inflammation. J Virol 2019, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, V.L.J.; Paula A, V.; Silvio, U.I. Chikungunya Virus Infection Induces Differential Inflammatory and Antiviral Responses in Human Monocytes and Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. Acta Trop 2020, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualberto Cavalcanti, N.; MeloVilar, K.; Branco Pinto Duarte, A.L.; Jesus Barreto de Melo Rêgo, M.; Cristiny Pereira, M.; da Rocha Pitta, I.; Diniz Lopes Marques, C.; Galdino da Rocha Pitta, M. IL-27 in Patients with Chikungunya Fever: A Possible Chronicity Biomarker? Acta Trop 2019, 196, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Anshita, D.; Ravichandiran, V. MCP-1: Function, Regulation, and Involvement in Disease. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 101, 107598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Narazaki, M.; Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in Inflammation, Immunity, and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6, a016295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.A.; Takeuchi, T.; Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J.; Choy, E.H.; McInnes, I. Interleukin 6: The Biology behind the Therapy. Considerations in Medicine 2018, 2, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Foo, S.S.; Sims, N.A.; Herrero, L.J.; Walsh, N.C.; Mahalingam, S. Arthritogenic Alphaviruses: New Insights into Arthritis and Bone Pathology. Trends Microbiol 2015, 23, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Trejo, A.M.; Rodríguez-Páez, L.I.; Alcántara-Farfán, V.; Aguilar-Faisal, J.L. Multiple Factors Involved in Bone Damage Caused by Chikungunya Virus Infection. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Tritsch, S.; Reid, St.; Martins, K.; Encinales, L.; Pacheco, N.; Amdur, R.; Porras-Ramirez, A.; Rico-Mendoza, A.; Li, G.; et al. The Cytokine Profile in Acute Chikungunya Infection Is Predictive of Chronic Arthritis 20 Months Post Infection. Diseases 2018, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic, n (%) | Cases | Controls | Total | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piedecuesta cohort | ||||

| Female | 9 (81.2) | 14 (40.0) | 23 (50.0) | 0.035 |

| Age (years) | 45.0 [15.0] | 30.0 [20.0] | 33.5 [19.0] | 0.001 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.2) | 1.000 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Articular disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| No medical history | 11 (100.0) | 34 (97.1) | 45 (97.8) | 1.000 |

| Capitanejo cohort | ||||

| Female | 12 (85.7) | 13 (65.0) | 25 (73.5) | 0.250 |

| Age (years) | 60.2 [13.3] | 48.8 [27.3] | 54.0 [25.5] | 0.150 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (7.1) | 1.000 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 (25.0) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (20.6) | 1.000 |

| Articular disease | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| No medical history | 13 (92.9) | 17 (85.0) | 30 (88.2) | 1.000 |

| Biomarker (pg/mL) | Cases | Controls | Total | p | Median Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | Relative (%) | ||||||

| Piedecuesta cohort | |||||||

| IL-4 | 1.3 [0.6 - 2.4] | 1.3 [0.6 - 2.0] | 1.3 [0.6 -2.2] | 0.661 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| IL-6 | 7.7 [4.8 - 15.5] | 4.9 [1.5 - 15.2] | 5.4 [1.9 – 15.2] | 0.102 | 2.8 | 57.1 | |

| IL-8/CXCL-8 | 19.1 [8.8 - 56.4] | 27.3 [18.4 – 42.8] | 23.4 [16.4 – 42.8] | 0.421 | -8.1 | -29.9 | |

| IL-27 | 1,978.0 [1,631.9 - 3,435.9] | 2,104.3 [1,052.3 - 3,513.3] | 1,981.8 [1,307.3 – 3,481.2] | 0.867 | -126.3 | -6.0 | |

| CCL-2 | 2,119.3 [1,246.8 - 3,552.7] | 1,929.9 [1,339.7 - 3,290.0] | 2,024 [1,339.7 – 3,290.0] | 0.598 | 189.4 | 9.8 | |

| CXCL-9 | 7,230.7 [4,974.4 - 11,349.4] | 7,926.7 [5,518.5 - 13,596.0] | 7,836.9 [5,518.5 – 12,908.3] | 0.709 | -696.0 | -8.8 | |

| CXCL-10 | 6,333.5 [2,862.6 - 38,829.6] | 24,223.1 [6,484.3 - 44,777.8] | 21,293.3 [6,329.2 – 43,769.0] | 0.082 | -17,889.6 | -73.9 | |

| IgG* | 28.0 [20.0 - 59.0] | 24.0 [18.0 - 44.0] | 25.0 [18.0 – 44.0] | 0.699 | 4.0 | 16.7 | |

| Capitanejo cohort | |||||||

| IL-4 | 0.6 [0.3 - 1.8] | 0.3 [0.2 - 0.9] | 0.6 [0.2 – 1.0] | 0.268 | 0.3 | 116.7 | |

| IL-6 | 2.6 [1.2 - 5.9] | 3.4 [1.8 - 5.6] | 3.2 [1.4 – 5.9] | 0.674 | -0.8 | -23.5 | |

| IL-8/CXCL-8 | 67.4 [45.2 - 96.9] | 71.2 [53.4 - 105.8] | 67.4 [50.9 – 97.9] | 0.806 | -3.8 | -5.3 | |

| IL-27 | 1,036.4 [814.7 - 1,379.1] | 927.7 [579.2 - 1,907.2] | 951.7 [680.6 – 1,715.5] | 0.834 | 108.7 | 11.7 | |

| CCL-2 | 878.9 [771.2 - 1,259.6] | 1,002.8 [733.9 - 1,187.1] | 991.0 [737.7 – 1,248.1] | 0.944 | -124.0 | -12.4 | |

| CXCL-9 | 4,032.6 [3,046.9 - 7,170.6] | 4,479.4 [2,518.5 - 10,558.0] | 4,226.0 [2,813.5 – 7,558.3] | 0.441 | -446.8 | -10.0 | |

| CXCL-10 | 522.9 [390.8 - 631.6] | 589.0 [373.0 - 858.4] | 536.4 [388.2 – 733.3] | 0.382 | -66.1 | -11.2 | |

| IgG* | 40.7 [29.1 – 44.7] | 31.4 [23.7 - 46.1] | 34.9 [25.2 – 46.0] | 0.632 | 9.3 | 29.6 | |

| Biomarker | Crude OR (CI 95%) | Adjusted OR (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-8/CXCL-8 (pg/mL) * | ||

| <35.7 | 0.90 (0.81 – 0.98) | 0.85 (0.74 - 0.99) |

| ≥35.7 | 1.09 (1.01 – 1.18) | 1.09 (0.97 - 1.22) |

| Age | - | 1.13 (1.01 - 1.27) |

| Sex | - | 0.13 (0.14 - 1.07) |

| Disease onset | - | 0.47 (0.21 - 1.05) |

| HL | 0.634 | 0.875 |

| AUC | 0.75 (IC95%: 0.59 - 0.91) | 0.92 (IC95%: 0.85 - 1.00) |

| CXCL-10 (100 pg/mL) * | ||

| <36,800 | 1.00 (0.99 - 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99 - 1.02) |

| ≥36,800 | 0.98 (0.96 - 1.01) | 0.94 (0.90 - 0.99) |

| Age | - | 1.18 (1.03 - 1.35) |

| Sex | - | 0.13 (0.02 - 1.14) |

| HL | 0.502 | 0.830 |

| AUC | 0.57 (IC95%: 0.38 - 0.75) | 0.90 (IC95%: 0.80 - 0.99) |

| CXCL-9 (100 pg/mL) † | ||

| <2,000 | 1.19 (0.84 - 1.69) | 0.95 (0.60 - 1.50) |

| ≥2,000 | 0.98 (0.96 - 1.00) | 0.96 (0.93 - 0.99) |

| Age | - | 1.11 (1.01 - 1.22) |

| Sex | - | 0.21 (0.01 - 2.90) |

| Disease onset | - | 0.96 (0.91 - 1.02) |

| HL | 0.439 | 0.408 |

| AUC | 0.61 (0.42 - 0.80) | 0.84 (0.70 - 0.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).