1. Introduction

Chikungunya fever (CHIK) is an acute mosquito-borne viral disease caused by the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), primarily transmitted through Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Due to global warming, urbanization, and increased population mobility, the geographical range of CHIKV transmission has expanded significantly and become a major public-health concern worldwide [

1]. Southern China, characterized by a humid subtropical climate and high mosquito density, provides favorable conditions for local CHIKV transmission and occasional outbreaks [

2].

Children represent a special population with immature immune systems and clinical manifestations that may differ from adults. Previous studies have shown that some pediatric patients develop prominent joint involvement, and a subset may experience persistent arthralgia or synovitis after the acute phase [

3,

4]. However, systematic clinical and imaging studies of pediatric CHIK remain limited, particularly regarding the relationship between virological load, clinical presentation, and joint ultrasonography.

The cycle threshold (CT) value from real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing is a commonly used indirect indicator of viral load; lower CT values reflect higher replication activity and may correlate with disease severity [

5]. Joint ultrasonography is a noninvasive and sensitive method for detecting early synovial inflammation and joint effusion [

6]. Combining virological and ultrasonographic data may therefore help clarify the relationship between viral replication and inflammatory joint involvement in pediatric patients.

Based on this, we retrospectively analyzed 42 pediatric CHIK cases confirmed at Foshan First People’s Hospital between July and August 2025 to evaluate their clinical characteristics and explore the correlation between viral CT values and joint ultrasonographic abnormalities. To our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic pediatric analysis in mainland China combining viral load and imaging findings to support early risk stratification and disease monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This retrospective study included 42 pediatric patients diagnosed with CHIKV infection at Foshan First People’s Hospital (Guangdong, China) between July and August 2025. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age ≤ 18 years; (2) acute febrile illness with typical rash and/or arthralgia; (3) laboratory confirmation of CHIKV infection by real-time RT-PCR of serum or throat swab specimens. Exclusion criteria included: (1) co-infection with other arboviruses such as dengue or Zika; (2) pre-existing rheumatologic disease; (3) incomplete clinical or imaging data. All cases were managed according to standard hospital protocols.

2.2. Data Collection

Demographic data (sex, age), clinical manifestations (fever, rash, joint pain), laboratory tests (complete blood count, liver and renal function, LDH), and RT-PCR CT values were retrieved from electronic medical records. Joint ultrasound was performed within 72 hours of admission using a high-frequency linear transducer (7–12 MHz) by experienced radiologists. Ultrasonographic findings were classified as normal or abnormal based on the presence of synovial hypertrophy, joint effusion, and/or increased vascular signal.

2.3. Grouping and Variables

Patients were divided into two groups based on the presence of arthralgia (arthralgia group vs. non-arthralgia group). Comparisons were made for demographics, clinical symptoms, laboratory parameters, and ultrasonographic findings. Subgroup analysis was performed by age (≤ 10 years vs. > 10 years) to assess differences in joint involvement.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were tested for normality and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR). Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Group comparisons were performed using the Student’s t test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous data and the χ² or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Correlations between CT values and joint involvement were analyzed using Spearman and Pearson coefficients. Two-tailed p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Clinical Characteristics

A total of 42 pediatric patients with confirmed Chikungunya fever were included, comprising 23 boys (54.8%) and 19 girls, with a mean age of 10.2 ± 4.1 years. Most patients (95.2%, 40/42) presented with fever as the initial symptom. The mean peak temperature was 38.7 ± 0.7 °C, lasting 2.3 ± 1.1 days, and all fevers subsided after administration of antipyretic agents. Some children experienced chills or rigors, and a few exhibited nonspecific findings such as conjunctival congestion. All patients developed rash, which lasted for an average of 4.9 ± 1.6 days and was mostly scattered over the limbs and trunk, occasionally involving the face. Eighteen cases (42.9%) presented with varying degrees of pruritus.

Among the 42 cases, 28 (66.7%) experienced arthralgia, including 3 who presented with joint pain as the initial symptom. The mean pain score was 2.6 ± 1.3 on a 0–10 visual analog scale (VAS), with a mean duration of 2.8 ± 1.3 days. The joints most frequently affected were the knees, ankles, and wrists, followed by fingers, toes, and elbows; a few cases also reported diffuse musculoskeletal discomfort. No involvement of the shoulders or spine was observed (

Table 1).

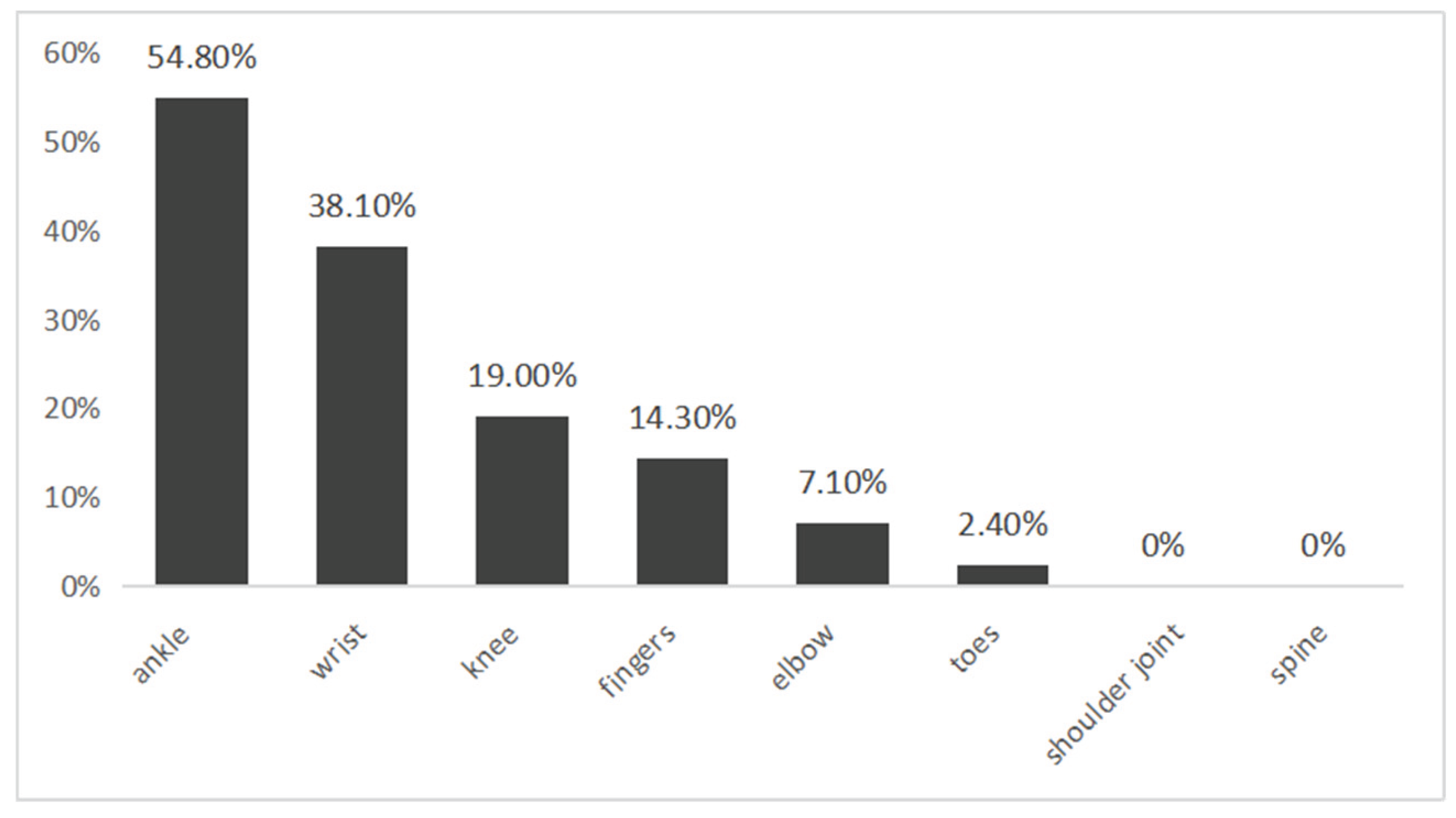

Further analysis showed that arthralgia typically involved multiple joints: 8 cases (19.0%) had single-joint involvement, 15 (35.7%) involved two joints, and 5 (11.9%) involved three to five joints. The most frequently affected joints were the ankles (54.8%) and wrists (38.1%), followed by knees (19.0%), fingers (14.3%), elbows (7.1%), and toes (2.4%) (

Figure 1). These findings suggest that pediatric CHIKV-associated arthralgia may range from localized to polyarticular, with a predominance in lower-limb and wrist joints.

When comparing across age groups, no significant differences were observed in fever incidence or duration between children aged ≤ 10 years and those aged > 10 years. The mean rash duration was slightly longer in the younger group (5.2 ± 1.6 days vs. 3.8 ± 1.7 days). However, differences in arthralgia were marked: the ≤ 10 year group had a 47.4% (9/19) incidence of arthralgia, predominantly monoarticular or oligoarticular (range 0–3 joints), whereas the > 10 year group had an 82.6% (19/23) incidence with broader polyarticular involvement (mean 1.7 joints, range 0–5). These results indicate that older children are more prone to arthralgia and to involvement of multiple joints, whereas younger children primarily present with fever and rash.

3.2. Laboratory Findings

Laboratory results during the acute phase of illness in the 42 pediatric patients showed that most had normal or slightly decreased leukocyte and platelet counts. A decreased lymphocyte ratio was observed in 47.6% of cases, indicating a viral infection pattern. C-reactive protein (CRP) was mildly elevated, with a mean level of 6.77 ± 10.59 mg/L, and only six patients (15%) exceeded 10 mg/L. Overall, these findings suggested a mild systemic inflammatory response during the acute phase.

Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) ranged from 161.5 to 414.2 IU/L, with a mean of 232.27 ± 59.41 IU/L. Nine cases (24.3%) exceeded the conventional upper reference limit (250 IU/L). Although LDH levels were elevated in some patients, no significant association was found with clinical symptom severity, implying that LDH elevation may reflect nonspecific systemic tissue injury rather than inflammation-specific activity.

3.3. Relationship Between Arthralgia and Ultrasonographic Abnormaliti

Among the 42 cases, 28 (66.7%) reported joint pain, and 24 of them underwent joint ultrasonography. Abnormal findings were observed in 20 (83.3%), mainly synovial hypertrophy and joint effusion, predominantly affecting the knees and ankles. Fourteen children without arthralgia also underwent ultrasonography, and none showed abnormalities. The difference between groups was statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001).

A total of 38 children underwent lymph node ultrasonography; 11 (28.9%) showed abnormalities, including cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph node enlargement or cortical thickening, with occasional involvement of submandibular or parotid regions. Among the 24 children with arthralgia, 11 (45.8%) had abnormal lymph node findings, whereas no abnormalities were detected among the 14 children without arthralgia (p = 0.0026). Detailed ultrasonographic comparisons are shown in

Table 2.

3.4. Correlation Between Viral CT Values and Joint Involvemen

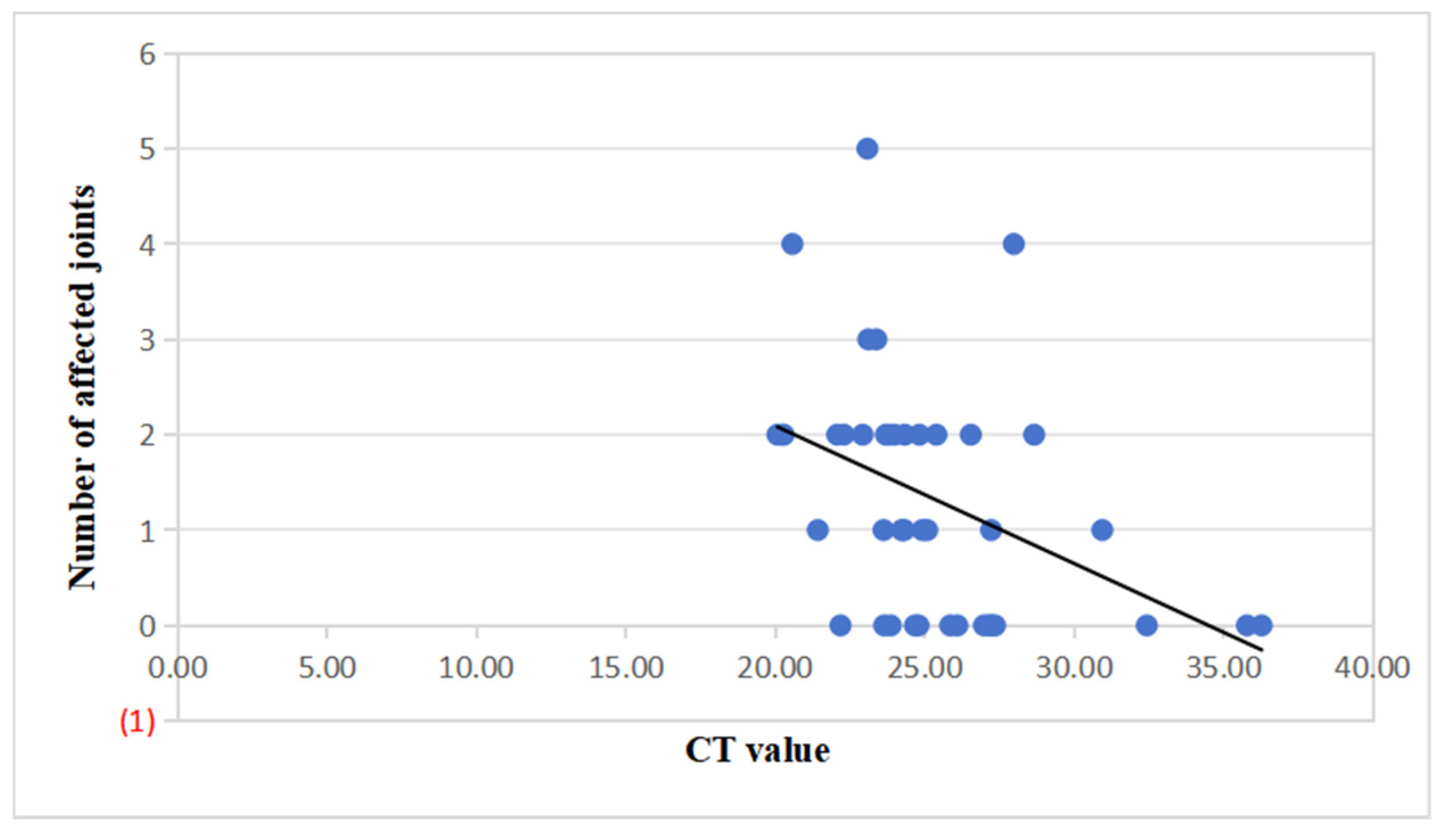

Among the 42 pediatric cases, further analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between viral nucleic acid CT values and the cumulative number of affected joints (Spearman r = –0.47, p = 0.002; Pearson r = –0.41, p = 0.007). This indicates that lower CT values (reflecting higher viral loads) were associated with more extensive joint involvement (

Figure 2).

In 19 patients with both complete CT value data and joint ultrasound results, a weak negative correlation was observed between CT value and ultrasonographic abnormality (r = –0.17, p = 0.482*), which was not statistically significant.

3.5. Dynamic Changes in CT Values Before Discharge

Sixteen of the 42 children underwent repeat virological testing before discharge: ten (62.5%) turned RT-PCR negative, suggesting viral clearance; six (37.5%) remained positive but with higher CT values than baseline, indicating reduced viral load. The median time to negativity was 4 (3–5) days, and the time to improvement (CT rise) was 3 (2–5) days. These findings suggest that most patients achieved virological improvement within approximately one week of admission.

4. Discussion

This study retrospectively analyzed 42 pediatric cases of Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, systematically evaluating clinical features, laboratory parameters, and imaging findings. Fever, rash, and arthralgia were the predominant manifestations, with 66.7% presenting joint pain, some as the initial symptom. The incidence of ultrasonographic abnormalities among children with arthralgia reached 83.3%, significantly higher than in those without arthralgia, and mainly manifested as synovial thickening and joint effusion. Additionally, lymph-node enlargement was more common in children with arthralgia, suggesting that CHIKV infection may induce not only local synovial inflammation but also systemic immune activation. Ultrasonography demonstrated high sensitivity for detecting synovial inflammatory changes. Consistent with previous adult studies, ultrasound serves as a valuable tool in evaluating acute joint involvement [

6]. While the general clinical spectrum aligns with earlier pediatric reports [

5,

7], most prior studies lacked integration of imaging data, and domestic imaging reports have remained limited [

8]. The present findings therefore provide new empirical evidence in Chinese children.

Age-stratified analysis revealed no significant differences in fever or rash incidence between younger (≤ 10 years) and older (> 10 years) children, whereas older children exhibited a higher frequency and wider distribution of joint pain. This age-related pattern supports prior observations that the pediatric CHIK clinical spectrum may vary with age [

3,

7]. Given the limited sample size, this association warrants confirmation in larger cohorts.

At the virological level, CT values showed a significant negative correlation with the cumulative number of affected joints, indicating that lower CT values (higher viral loads) were associated with more extensive joint involvement. Real-time RT-PCR CT values serve as a semi-quantitative indicator of viral replication, with low values denoting high viral activity that may parallel disease severity [

5]. Adult investigations have demonstrated that high viral load can promote synovial inflammation and chronic arthropathy [

9]. Accordingly, CT value may provide an early surrogate marker for assessing the risk of multi-joint involvement in pediatric CHIK.

Previous imaging studies on pediatric Chikungunya fever in China are extremely limited. The Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Foshan reported 31 pediatric cases, all of whom underwent joint ultrasonography, revealing a high incidence of joint effusion suggestive of early synovial inflammation (unpublished data, internal report from Foshan Maternal and Child Health Hospital, 2025). However, that study was confined to descriptive imaging findings without quantitative analysis of virological parameters such as CT values. In contrast, the present study achieved an integrated analysis combining virological and imaging indicators. By correlating RT-PCR–derived CT values with the number of affected joints and ultrasonographic abnormalities, we demonstrated a negative association between viral load and the extent of joint inflammation. This provides quantitative evidence linking viral replication intensity with inflammatory response severity and lays a methodological foundation for future risk-stratification and prognostic modeling in pediatric CHIK.

Regarding laboratory parameters, mild elevation of LDH was observed in some patients but showed no significant correlation with viral load or joint involvement, suggesting that LDH more likely reflects nonspecific systemic tissue injury rather than synovial inflammatory activity. This aligns with prior pediatric studies reporting limited diagnostic utility of LDH in CHIK [

10].

Immunologically, previous research indicates that children and adults exhibit distinct inflammatory-response patterns: pediatric patients often show stronger innate immune activation with elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels [

10], whereas adult studies have demonstrated persistent viral presence in synovial tissue leading to chronic inflammation [

4]. These mechanistic differences may underlie variations in clinical presentation. However, because cytokine profiles and follow-up imaging were not assessed in this study, such interpretations remain speculative and require validation in prospective designs.

Clinically, the strong association between arthralgia and ultrasonographic abnormalities underscores ultrasound as a sensitive modality for identifying acute joint involvement. The observed dynamic consistency between CT-value variation and symptom recovery suggests its potential role in early risk stratification. Regarding chronic progression, prior pediatric reports found a lower incidence of persistent arthralgia compared with adults [

3]; our study lacked 3–6-month follow-up data and thus cannot determine chronic outcomes. Future longitudinal work incorporating serial ultrasound and symptom evaluation is warranted to clarify long-term prognosis.

Study limitations include: (1) single-center retrospective design with a small sample; (2) incomplete ultrasound or biochemical data in some patients, introducing selection bias; and (3) lack of cytokine or immunologic profiling, which may underestimate associations between virological and clinical parameters. Future studies could involve multi-center, large-sample, long-term follow-up designs incorporating inflammatory cytokines and immune profiling to verify the clinical applicability of CT values in risk stratification and prediction of chronic joint manifestations. Despite the limited sample size, this study provides a valuable reference for future multi-center pediatric investigations.

5. Conclusions

Pediatric CHIKV infection mainly presents with fever, rash, and joint pain. Children with high viral loads (low CT values) are more prone to polyarticular involvement, and those with arthralgia show markedly higher rates of ultrasound-detected synovial abnormalities. Mild LDH elevation is nonspecific and unsuitable for joint-risk assessment. Integrating clinical features, CT values, and ultrasonographic findings may facilitate early recognition and risk management of pediatric CHIK during the acute phase.

Ethical Approval Statement: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Foshan First People’s Hospital (Approval No. Lunshenyan [2025] 220) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants.

Funding

This work was supported by the internal research fund of Foshan First People’s Hospital (Foshan, China). The funder had no role in the design, analysis, or publication of this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Departments of Pediatrics and Ultrasound at Foshan First People’s Hospital for their assistance in data collection and imaging interpretation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tjaden N B,Suk J E,Fischer D,et al. Modelling the effects of global climate change on Chikungunya transmission in the 21st century. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, H. Advances in Epidemiology and Vector Biology of Chikungunya Fever in China. China Tropical Medicine 2025, 25, 582–587. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira B D J,Brasil M Q A,Silva J J,et al. Chikungunya in a pediatric cohort:Asymptomatic infection,seroconversion,and chronicity rates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2025, 19, e0013254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoarau J J,Jaffar Bandjee M C,Krejbich Trotot P,et al. Persistent chronic inflammation and infection by Chikungunya arthritogenic alphavirus in spite of a robust host immune response. J Immunol 2010, 184, 5914–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B S R,Patel A K,Kabra S K,et al. Virus load and clinical features during the acute phase of Chikungunya infection in children. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0211036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettery M,Brunier L,Banydeen R,et al. Management of acute-stage chikungunya disease:Contribution of ultrasonographic joint examination. Int J Infect Dis 2019, 84, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik K D,Kumar C G D,Abimannane A,et al. Chikungunya infection in children:clinical profile and outcome. J Trop Pediatr 2024, 71, fmae057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janella, C. Imaging findings in chikungunya fever. Radiol Bras 2017, 50, V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamanukul S,Osiri M,Chansaenroj J,et al. Rheumatic manifestations of Chikungunya virus infection:Prevalence, patterns,and enthesitis. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0249867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beserra F L C N,Oliveira G M,Marques T M A,et al. Clinical and laboratory profiles of children with severe chikungunya infection. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2019, 52, e20180232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).