Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights

- Increased Peroxidoxin expression linked to L. tropica visceralization in VL cases.

- No Leishmania RNA virus 1 detected in visceralized L. tropica isolates.

- L. tropica VL isolates show significant gene expression differences vs. CL strains.

- Novel mutations in Oligopeptidase B and Metallo-peptidase linked to VL pathogenesis.

- L. tropica identified as a potential cause of visceral leishmaniasis.

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Clinical Sample Collection and Parasite Culture

2.3. Leishmania Genotyping

2.4. Real-Time qRT-PCR

2.5. Evaluation of Genes by Comparing Gene Sequences

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Leishmaniasis Cases

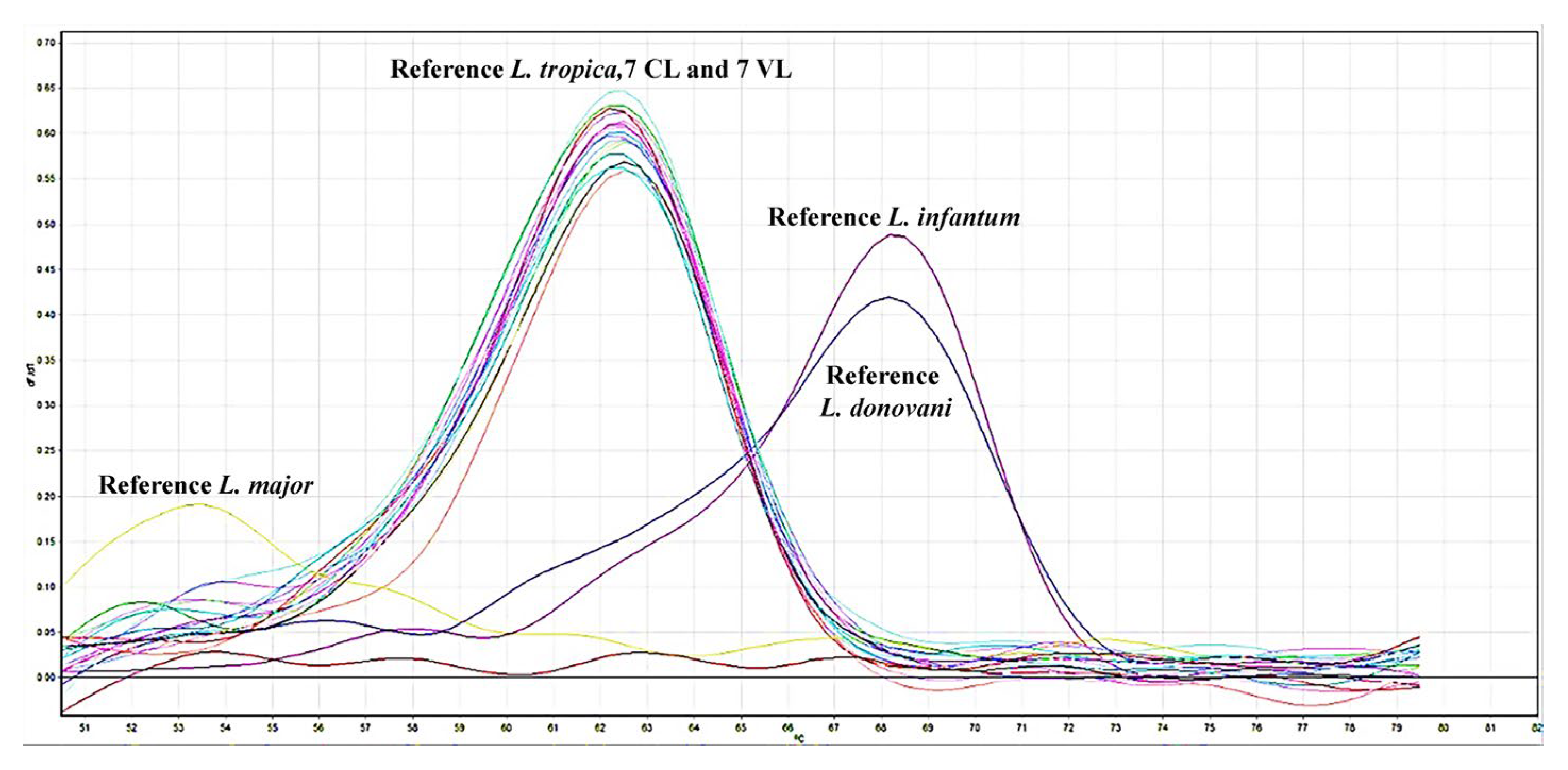

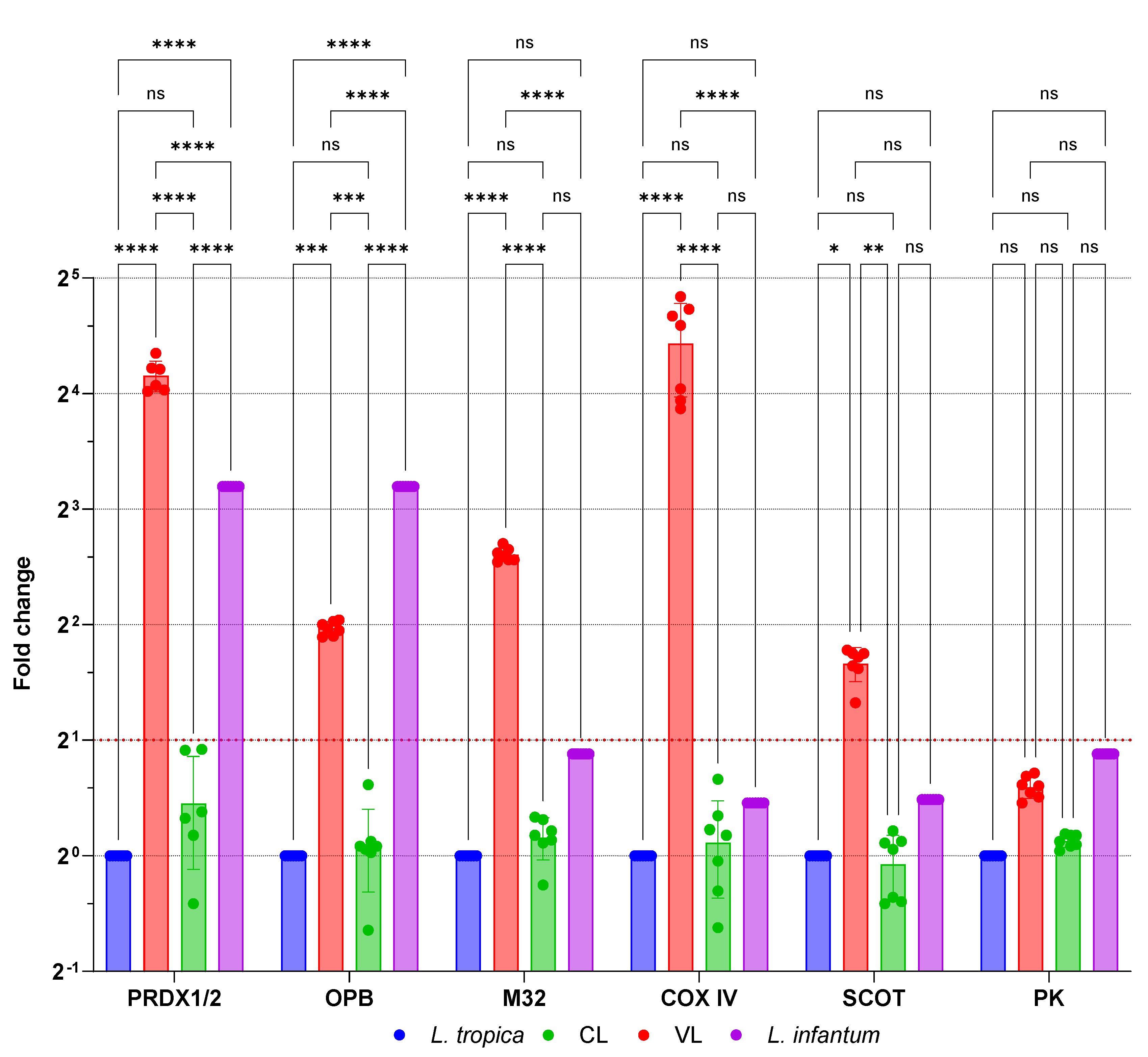

3.2. mRNA Expression Alterations of Genes Associated with Viscerotropism

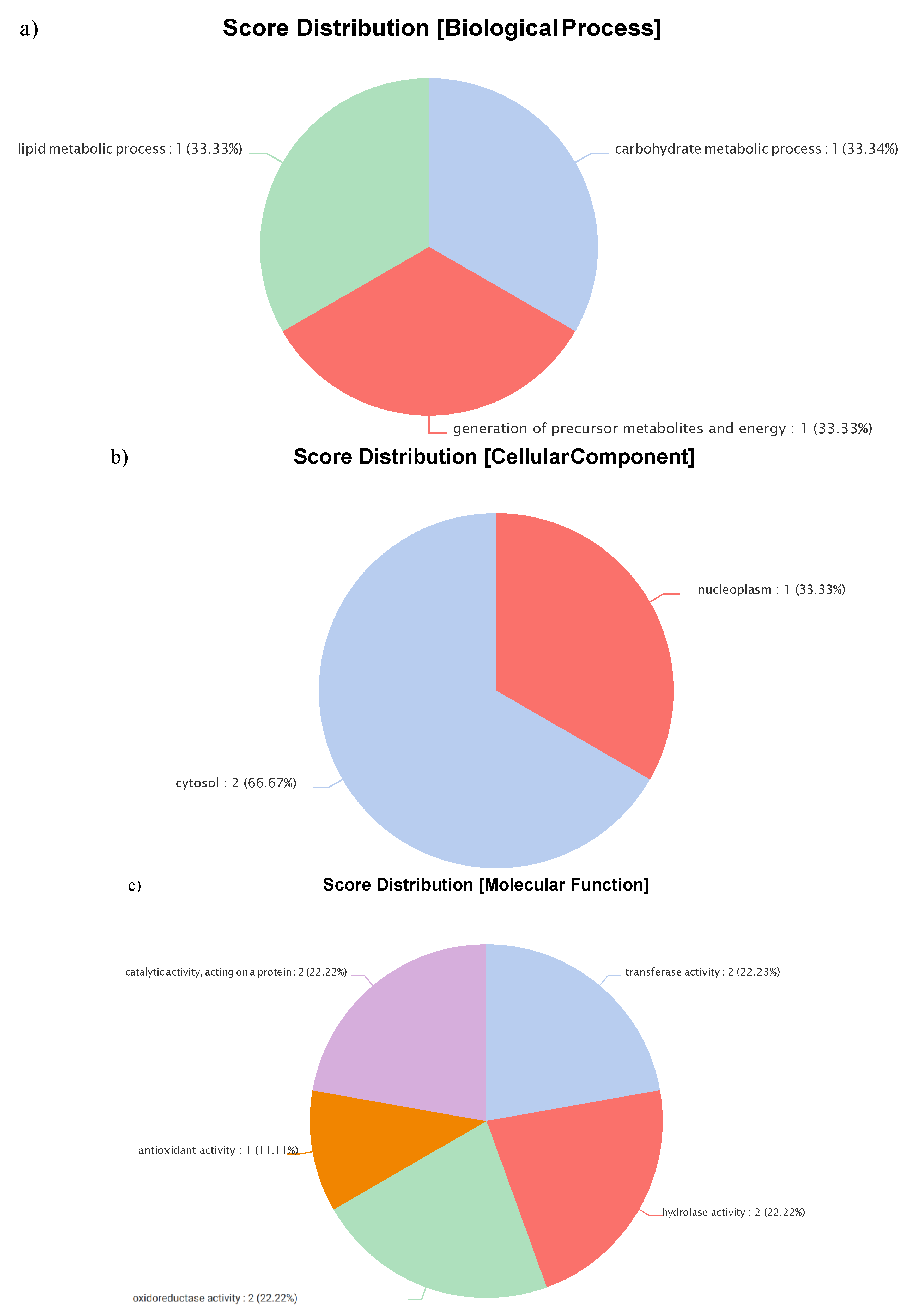

3.3. Gene-Level Analysis of Visceralized Leishmania Tropica

| Clinical feature | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Weight loss | + | + | + | – | + | + | – |

| Fatigue | + | + | – | + | + | + | + |

| GIS symptoms | – | + | + | + | – | + | + |

| Epistaxis/Gingival bleeding | + | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| Splenomegaly | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hepatomegaly | + | + | + | + | - | + | + |

| Pancytopenia | + | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Leukopenia | – | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Thrombocytopenia | – | – | – | + | – | – | – |

| Microscopy | Positive | Negative | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Modified NNN | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Seropositivity (IFAT) | 1/512 | 1/512 | 1/512 | 1/1024 | 1/512 | 1/1024 | 1/1024 |

| qPCR (Bone marrow) | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCall, L.I.; Zhang, W.W.; Matlashewski, G. Determinants for the Development of Visceral Leishmaniasis Disease. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvar, J.; Vélez, I.D.; Bern, C.; Herrero, M.; Desjeux, P.; Cano, J.; Jannin, J.; de Boer, M. Leishmaniasis Worldwide and Global Estimates of Its Incidence. PLoS One 2012, 7, e35671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, J. Leishmania. JAMA 2007, 298, 277–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, R.; Torres-Guerrero, E.; Quintanilla-Cedillo, M.R.; Ruiz-Esmenjaud, J. Leishmaniasis: A Review. F1000Res 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical Care of Leishmaniasis | Leishmaniasis | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-care/index.html (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Bailey, M.S.; Lockwood, D.N.J. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Clin Dermatol 2007, 25, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathers, C.D.; Ezzati, M.; Lopez, A.D. Measuring the Burden of Neglected Tropical Diseases: The Global of Disease Framework. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2007, 1, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, C.M.S.; Pedrosa, C.M.S. Clinical Manifestations of Visceral Leishmaniasis (American Visceral Leishmaniasis). The Epidemiology and Ecology of Leishmaniasis 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, B.M.; Carvalho, E.M.; Wilson, M.E. Cutaneous Manifestations of Human and Murine Leishmaniasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Madhu, M.; Murti, K. An Overview on Leishmaniasis. Viral, Parasitic, Bacterial, and Fungal Infections: Antimicrobial, Host Defense, and Therapeutic Strategies 2023, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burza, S.; Croft, S.L.; Boelaert, M. Leishmaniasis. The Lancet 2018, 392, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, L.; Singh, K.K.; Shanker, V.; Negi, A.; Jain, A.; Matlashewski, G.; Jain, M. Atypical Leishmaniasis: A Global Perspective with Emphasis on the Indian Subcontinent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, H.L.; Portal, I.F.; Bensinger, S.J.; Grogl, M. Leishmaniaspp: Temperature Sensitivity of Promastigotesin Vitroas a Model for Tropismin Vivo. Exp Parasitol 1996, 84, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, A.; Ghosh, S.; Pakrashi, S.; Roy, D.; Sen, S.; Chatterjee, M. Leishmania Strains Causing Self-Healing Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Have Greater Susceptibility towards Oxidative Stress. Free Radical Research 2012, 46, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Matlashewski, G. Loss of Virulence in Leishmania Donovani Deficient in an Amastigote-Specific Protein, A2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 8807–8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizbani, A.; Taslimi, Y.; Zahedifard, F.; Taheri, T.; Rafati, S. Effect of A2 Gene on Infectivity of the Nonpathogenic Parasite Leishmania Tarentolae. Parasitol Res 2011, 109, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charest, H.; Matlashewski, G. Developmental Gene Expression in Leishmania Donovani: Differential Cloning and Analysis of an Amastigote-Stage-Specific Gene. Mol Cell Biol 1994, 14, 2975–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inbar, E.; Shaik, J.; Iantorno, S.A.; Romano, A.; Nzelu, C.O.; Owens, K.; Sanders, M.J.; Dobson, D.; Cotton, J.A.; Grigg, M.E.; et al. Whole Genome Sequencing of Experimental Hybrids Supports Meiosis-like Sexual Recombination in Leishmania. PLoS Genet 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glans, H.; Karlberg, M.L.; Advani, R.; Bradley, M.; Alm, E.; Andersson, B.; Downing, T. High Genome Plasticity and Frequent Genetic Exchange in Leishmania Tropica Isolates from Afghanistan, Iran and Syria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021, 15, e0010110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glans, H.; Karlberg, M.L.; Advani, R.; Bradley, M.; Alm, E.; Andersson, B.; Downing, T. High Genome Plasticity and Frequent Genetic Exchange in Leishmania Tropica Isolates from Afghanistan, Iran and Syria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021, 15, e0010110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iantorno, S.A.; Durrant, C.; Khan, A.; Sanders, M.J.; Beverley, S.M.; Warren, W.C.; Berriman, M.; Sacks, D.L.; Cotton, J.A.; Grigg, M.E. Gene Expression in Leishmania Is Regulated Predominantly by Gene Dosage. mBio 2017, 8, e01393–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussotti, G.; Piel, L.; Pescher, P.; Domagalska, M.A.; Shanmugha Rajan, K.; Cohen-Chalamish, S.; Doniger, T.; Hiregange, D.G.; Myler, P.J.; Unger, R.; et al. Genome Instability Drives Epistatic Adaptation in the Human Pathogen Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait Maatallah, I.; Akarid, K.; Lemrani, M. Tissue Tropism: Is It an Intrinsic Characteristic of Leishmania Species? Acta Trop 2022, 232, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbilgin, A.; Çulha, G.; Uzun, S.; Harman, M.; Topal, S.G.; Okudan, F.; Zeyrek, F.; Gündüz, C.; Östan, I.; Karakuş, M.; et al. Leishmaniasis in Turkey: First Clinical Isolation of Leishmania Major from 18 Autochthonous Cases of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Four Geographical Regions. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2016, 21, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toz, S.O.; Culha, G.; Zeyrek, F.Y.; Ertabaklar, H.; Alkan, M.Z.; Vardarlı, A.T.; Gunduz, C.; Ozbel, Y. A Real-Time ITS1-PCR Based Method in the Diagnosis and Species Identification of Leishmania Parasite from Human and Dog Clinical Samples in Turkey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013, 7, e2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinç, M. Proteomic Analyses of Biological Samples by Using Different Mass Spectrometric Strategies. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses 2018, 28476510. [Google Scholar]

- C. de Oliveira, T.; Rodrigues, P.T.; Menezes, M.J.; Gonçalves-Lopes, R.M.; Bastos, M.S.; Lima, N.F.; Barbosa, S.; Gerber, A.L.; Loss de Morais, G.; Berná, L.; et al. Genome-Wide Diversity and Differentiation in New World Populations of the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Vivax. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.N.; Uplekar, S.; Kayal, S.; Mallick, P.K.; Bandyopadhyay, N.; Kale, S.; Singh, O.P.; Mohanty, A.; Mohanty, S.; Wassmer, S.C.; et al. A Method for Amplicon Deep Sequencing of Drug Resistance Genes in Plasmodium Falciparum Clinical Isolates from India. J Clin Microbiol 2016, 54, 1500–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šlapeta, J.; Dowd, S.E.; Alanazi, A.D.; Westman, M.E.; Brown, G.K. Differences in the Faecal Microbiome of Non-Diarrhoeic Clinically Healthy Dogs and Cats Associated with Giardia Duodenalis Infection: Impact of Hookworms and Coccidia. Int J Parasitol 2015, 45, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebrahtu, Y.; Lawyer, P.; Githure, J.; Were, J.B.; Muigai, R.; Hendricks, L.; Leeuwenburg, J.; Koech, D.; Roberts, C. Visceral Leishmaniasis Unresponsive to Pentostam Caused by Leishmania Tropica in Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1989, 41, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, A.J.; Grogl, M.; Gasser, R.A.; Sun, W.; Oster, C.N. Visceral Infection Caused by Leishmania Tropica in Veterans of Operation Desert Storm. N Engl J Med 1993, 328, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborzi, A.; Pouladfar, G.R.; Fakhar, M.; Motazedian, M.H.; Hatam, G.R.; Kadivar, M.R. Isolation of Leishmania Tropica from a Patient with Visceral Leishmaniasis and Disseminated Cutaneous Leishmaniasis, Southern Iran. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008, 79, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARKARI, B.; AHMADPOUR, N.B.; MOSHFE, A.; HAJJARAN, H. Molecular Evaluation of a Case of Visceral Leishmaniasis Due to Leishmania Tropica in Southwestern Iran. Iran J Parasitol 2016, 11, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Ghatee, M.A.; Mirhendi, H.; Karamian, M.; Taylor, W.R.; Sharifi, I.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Kanannejad, Z. Population Structures of Leishmania Infantum and Leishmania Tropica the Causative Agents of Kala-Azar in Southwest Iran. Parasitol Res 2018, 117, 3447–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafchi, H.R.; Kazemi-Rad, E.; Mohebali, M.; Raoofian, R.; Ahmadpour, N.B.; Oshaghi, M.A.; Hajjaran, H. Expression Analysis of Viscerotropic Leishmaniasis Gene in Leishmania Species by Real-Time RT-PCR. Acta Parasitol 2016, 61, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardenas, D.; Carter, P.M.; Nation, C.S.; Pizarro, J.C.; Guidry, J.; Aiyar, A.; Kelly, B.L. LACK, a RACK1 Ortholog, Facilitates Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit Expression to Promote Leishmania Major Fitness. Mol Microbiol 2015, 96, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajjaran, H.; Mousavi, P.; Burchmore, R.; Mohebali, M.; Mohammadi Bazargani, M.; Hosseini Salekdeh, G.; Kazemi-Rad, E.; Khoramizadeh, M.R. Comparative Proteomic Profiling of Leishmania Tropica: Investigation of a Case Infected with Simultaneous Cutaneous and Viscerotropic Leishmaniasis by 2-Dimentional Electrophoresis and Mass Spectrometry. Iran J Parasitol 2015, 10, 366. [Google Scholar]

- Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit IV - Leishmania Donovani | UniProtKB | UniProt. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/A0A3S5H6L2/entry (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Castro, H.; Teixeira, F.; Romao, S.; Santos, M.; Cruz, T.; Flórido, M.; Appelberg, R.; Oliveira, P.; Ferreira-da-Silva, F.; Tomás, A.M. Leishmania Mitochondrial Peroxiredoxin Plays a Crucial Peroxidase-Unrelated Role during Infection: Insight into Its Novel Chaperone Activity. PLoS Pathog 2011, 7, e1002325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza, C.E.; Zhong, X.; Rosas, L.E.; White, J.D.; Chen, R.P.Y.; Liang, G.F.C.; Chan, S.I.; Satoskar, A.R.; Chan, M.K. A Proposed Role for Leishmania Major Carboxypeptidase in Peptide Catabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 373, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Ghosh, S.; Pakrashi, S.; Roy, D.; Sen, S.; Chatterjee, M. Leishmania Strains Causing Self-Healing Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Have Greater Susceptibility towards Oxidative Stress. Free Radic Res 2012, 46, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, V.E.; Niemirowicz, G.T.; Cazzulo, J.J. The Peptidases of Trypanosoma Cruzi: Digestive Enzymes, Virulence Factors, and Mediators of Autophagy and Programmed Cell Death. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 2012, 1824, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenerton, R.K.; Zhang, S.; Sajid, M.; Medzihradszky, K.F.; Craik, C.S.; Kelly, B.L.; McKerrow, J.H. The Oligopeptidase B of Leishmania Regulates Parasite Enolase and Immune Evasion. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, S.; Grover, S.; Dhanjal, J.K.; Goyal, M.; Tyagi, C.; Chacko, S.; Grover, A. Mechanistic Insights into Mode of Actions of Novel Oligopeptidase B Inhibitors for Combating Leishmaniasis. J Mol Model 2014, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafmansouri, M.; Amiri-Dashatan, N.; Ahmadi, N. Identification of Protein Profile in Metacyclic and Amastigote-like Stages of Leishmania Tropica: A Proteomic Approach. AMB Express 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gene Ontology and GO Annotations. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/ (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Frasch, A.P.; Carmona, A.K.; Juliano, L.; Cazzulo, J.J.; Niemirowicz, G.T. Characterization of the M32 Metallocarboxypeptidase of Trypanosoma Brucei: Differences and Similarities with Its Orthologue in Trypanosoma Cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol 2012, 184, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Code | Gender | Age | Region | Symptom | Genotype of Amastigotes from Clinical Samples | Genotype of Promastigotes Grown in Culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | M | 7 | Aegean | Fever, rapid weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, nausea, diarrhea | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| V2 | F | 10 | Aegean | Weight loss, weakness, fever, anorexia, pancytopenia, nose and tooth bleeding, hepatosplenomegaly, growth retardation | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| V3 | F | 12 | Aegean | Swelling in the left upper quadrant, night sweats, anorexia, rapid weight loss (5 kg in the last 1 month), splenomegaly, pancytopenia | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| V4 | M | 20 | Aegean | Fever, hepatosplenomegaly, anorexia, spleen infarction, general condition disorder, diarrhea, pancytopenia, nose and gum bleeding, general condition disorder | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| V5 | M | 50 | Aegean | Fever, diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, dizziness, weakness, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, hepatosplenomegaly | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| V6 | M | 53 | Aegean | Fever, anorexia, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, weight loss, malaise, diarrhea | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| V7 | M | 55 | Mediterranean | Fever, weight loss, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, anorexia, nausea | L. tropica | L. tropica |

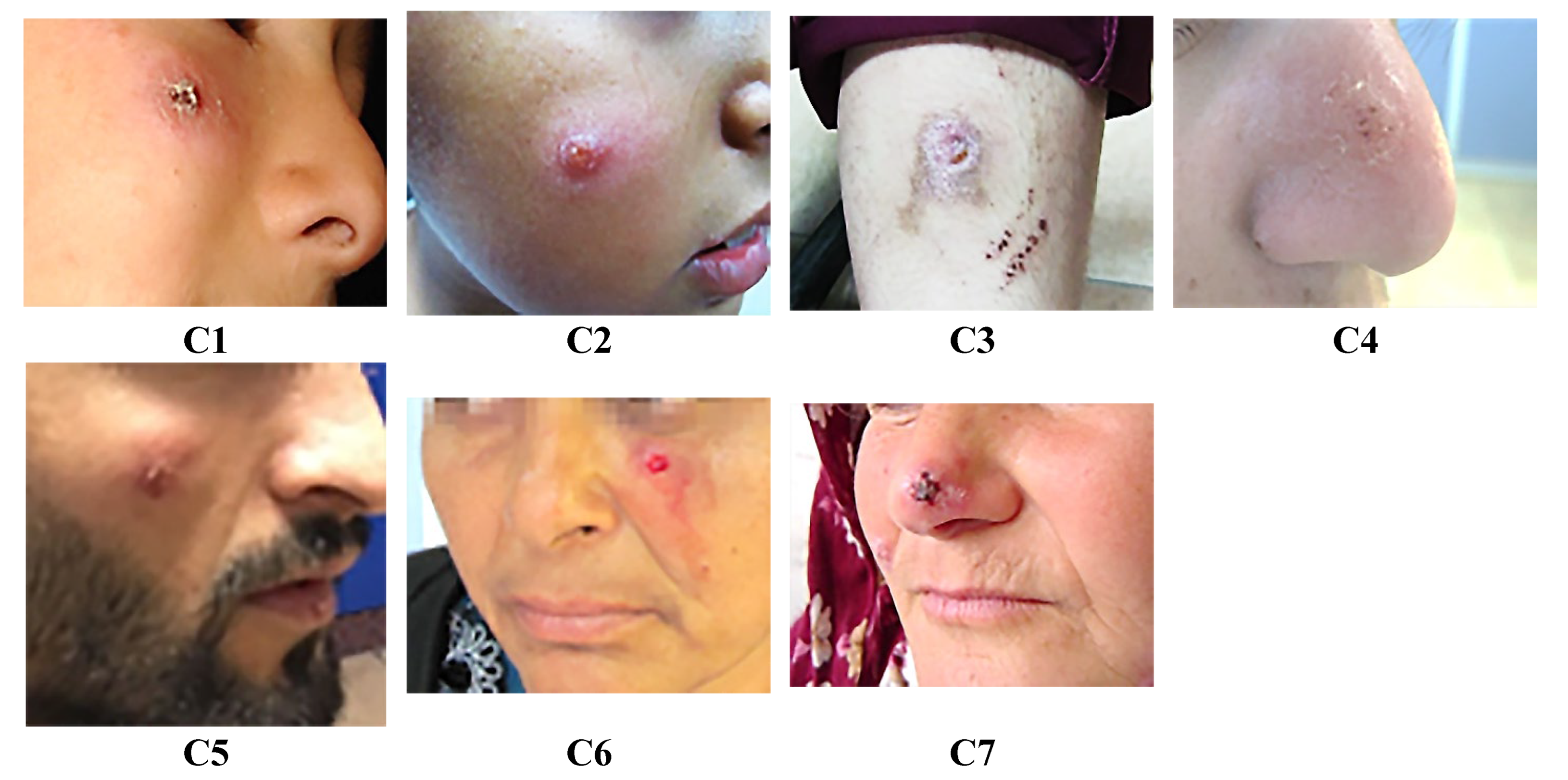

| C1 | M | 10 | Aegean | Nodular dry type lesion on the right cheek for 3 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| C2 | M | 11 | Aegean | Plaques with vascularity on the skin of the right zygomatic region of the face, dry type lesion present for 24 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| C3 | F | 17 | Aegean | Dry type lesion on the right arm for 3 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| C4 | F | 18 | Aegean | Dry type lesion on the right side of the nose for 7 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| C5 | M | 25 | Aegean | Dry type lesion on the right cheek for 8 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| C6 | F | 35 | Aegean | Dry type lesion under the eye on the left cheek for 6 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| C7 | F | 47 | Aegean | Dry type, itchy lesion on the tip of the nose for 12 months | L. tropica | L. tropica |

| Viscerotropism associated genes | Reference L. tropica | CL | VL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peroxidoxin 1 | _ | _ | _ |

| Peroxidoxin 2 | _ | _ | _ |

| Oligopeptidase B | c.1031A>G (p.Asp344Gly) c.1306C>G (p.Pro436Ala) |

c.1031A>G (p.Asp344Gly) c.1306C>G (p.Pro436Ala) |

_ |

| Metallo-peptidase, Clan MA (E), M32 family protein | c.169G>T (p.Ala57Ser) | c.169G>T (p.Ala57Ser) | _ |

| Cytochrome C Oxidase subunit IV | _ | _ | _ |

| Succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-coenzyme A transferase | _ | _ | _ |

| Pyruvate kinase | c.1362G>A (p.Glu454Lys) | c.1362G>A (p.Glu454Lys) | c.1362G>A (p.Glu454Lys) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).