1. Introduction

Construction, renovation, and demolition (CRD) activities generate huge volumes of waste. Particularly, countries where the construction of residential, commercial, and industrial spaces utilizes substantial quantities of wood, fall under this case. According to Laadila et al., 2021, over 500 million tons (Mt) of CRD waste were generated annually across Canada, USA, and Europe. Management and disposal of CRD wood residues create numerous environmental and economic challenges. This also includes furniture parts that are organically contaminated wood fibers without a promising scope for reuse (Kumar et al., 2024). Such wood contains treated, tinted, or composite materials infused with chemicals like polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), heavy metals, paints, lubricants, and resins, making them non-recyclable and deteriorating in quality (Ganesan et al., 2025). Especially, chromated copper arsenate (CCA) remnants in CRD wood waste disposal could face major hurdles in terms of disposal due to rising restrictions (Gmar et al., 2022). A common, non-advisable practice followed for their disposal is usually landfilling which causes problems when these toxic substances from CRD wood waste leach into surrounding soil and groundwater posing serious risks to human and ecosystem health. Anaerobic decomposition of organic fractions in wood waste within landfills can produce harmful greenhouse gases (GHGs) like methane and carbon dioxide contributing to the climate crisis (O'Dwyer et al., 2018). Inadequate monitoring, lack of public awareness, absence of strict regulations for landfilling, and economic/technological burden inflicted on recycling technologies for CRD wood, allow handlers to look for easy disposal methods. Even simple sorting is complicated due to large variability in wood composition with geography and provincial sourcing practices. These externalities exacerbate an already growing strain on limited landfill spaces. Hence, alternative waste management technologies are needed to pave the way for valorizing CRD wood residues to bioenergy, biochemicals, and bioproducts.

Waste forest wood, whether sequestered directly from the forests or sourced from CRD sites, are typically low-value feedstock harboring scarce probability to be reused or recycled. The economic value of such wastes could be improved by efficient thermochemical conversion technologies such as torrefaction, gasification, or pyrolysis (Kizha & Han, 2016). Pyrolysis has immense potential in serving as a recovery pathway for refused wood residues mainly due to its distinct product stream, moderate operation conditions, and relatively simplistic operation/instrumentation than gasification (Ganesan et al., 2025). Upon depolymerization of biomass in low or no oxygen, the transformation yields three major products with high energy and oxygen content: solid biochar, liquid pyrolysis oil or biooil, and pyrolysis gas (Rao et al., 2022). Depending upon the application under focus, pyrolysis can either be carried out at low or high temperatures. For instance, low-temperature pyrolysis (<500°C) produces cyclic, stable aromatics as in biochar whereas temperatures >600°C produce pyrolysis gas that are partly condensible into biooil (Zhang et al., 2023). Biooil can serve as a foundation for producing platform chemicals or can be upgraded to fuel intermediates (Guedes et al., 2018). Pyrolysis gas, commonly referred to as energy-rich syngas, made of CO, CO2, H2, and other light C1-C3, can also serve as a base for liquid synfuels or can be combusted in boilers/furnaces for energy generation, surrounding it from a resource-recovery perspective (Mouneir & El-Shamy, 2024). Biochar may serve as a partial substitute for fossil coal and carbon black in hard-to-abate industrial sectors such as metallurgy, automobiles, construction, agriculture, soil remediation, biogas production, air and water purification (Peters et al., 2015, Ibitoye et al., 2024, Hasan et al., 2024, Legan et al., 2022). For a complex feedstock like CRD wood, pyrolysis may even trap all inherent hazardous components and immobilize them within the biochar product. But these biochars can eventually cause toxicity concerns because it may contain original PAHs from the wood feed as well as volatile organic compounds (VOCs), dioxins, and free radicals that are persistent (Han et al., 2022).

For safe pyrolysis, other non-wood contaminants like nails, plastics, concrete, glass, and rubber have to be removed without fail during the pre-treatment stages to avoid complications with reactor operation and efficient biomass conversion. On that note, for a smooth conversion, CRD biomass has to be uniformly size-treated via shredding, grinding or milling, to reduce particle size so that heat transfer, bulk density, and energy density limitations are subdued (Mlonka-Mędrala et al., 2019). Whenever biochar is leveraged to address environmental or industrial challenges, its stability determines the resistance towards chemical, thermal, or microbial degradation while enabling it to act as a carbon sink (Adhikari et al., 2024). The nature of feedstock and pyrolysis parameters like temperature, heating rate, and biomass residence time (BRT) govern this stability factor through the physicochemical properties of biochar as understood from Altıkat et al., 2024. The final quality and intended applications depend on how the biomass feedstock is pre-treated, what the process optimization steps are, and the scale of production.

Biopolymers in biomass such as cellulose, hemicellulose (together called holocellulose), and lignin contents have specific decomposition pathways that take place at different temperatures and different stages. Solid-gas phase reactions involving multiple reactive species makes the prediction of pyrolysis reaction modelling cumbersome (Ranzi et al., 2017). To understand what pyrolysis does to CRD biomass, getting to know the kinetics and thermodynamics is beneficial. Kinetics describes the nature and type of chemical reactions occurring during pyrolysis and the energy required to form intermediate complexes and products whereas thermodynamics describes how energy enters and leaves a system during these chemical reactions. Usually, pyrolysis may contain single-step reactions proceeding individually or multiple competitive biomass breakdown reactions that proceed simultaneously or sequentially underscoring the intricacies of this process (Silva et al., 2023). Yield, ion exchange capacities, influence of ash, pore size, volatile content, and carbon arrangement in biochar are invariably dictated by the thermal degradation profiles too. Therefore, careful consideration of the various temperatures, heating rates, conversion rates, and selecting appropriate kinetic models are very important to forecast pyrolysis behavior. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) is a systematic and structured method to under chemical kinetics of biomass pyrolysis. According to Branca & Galgano, 2024, for fitting experimental data, assumptions based on different theoretical models are used via model-fitting methods. Whereas, the biomass conversion rate with the associated temperature required for that conversion at different heating rates is applied to the experimental TGA data via model-free or isoconversional methods (used interchangeably). Kinetic parameters such as activation energy and thermodynamic parameters like enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG), can be calculated at each heating rate employed to study the influence of pyrolysis process parameters on biomass decomposition (Thejaswini et al., 2023).

To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a “detailed” study on the reaction kinetics and thermodynamics of heterogeneous CRD wood waste pyrolysis to biochar. To assist in fixing this research gap, the objectives of our study will be to: a) succinctly explain the theory behind model-fitting and model-free techniques with necessary equations along with the benefits and drawbacks of adapting to these methods; b) investigate the physicochemical characteristics of biomass, and understand its surface chemical make-up; and c) analyze the thermochemical degradation mechanisms via TGA at different heating rates and calculate kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. Approaching these measures would facilitate designing any robust pyrolysis processes using CRD wood as a substrate for biochar production.

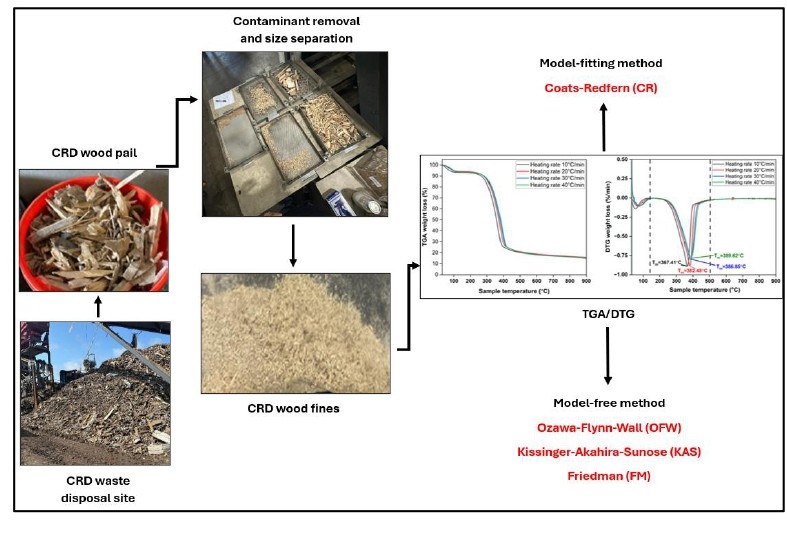

To engage with the aforesaid objectives, the idea behind each model is explored initially, followed by carrying out a compositional, proximate, elemental, and metal analysis of the CRD wood waste to understand the physicochemical properties of the feedstock. Next, the surface chemistry of CRD wood was also studied using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to project its composition and structural framework. Subsequently, TGA experiments using CRD biomass at four different heating rates: 10, 20, 30, and 40°C/min are carried out and the data is cleaned and curated to be analyzed according to the methods under consideration. Firstly, for the model-fitting methods, the Coats-Redfern (CR) approximation is utilized. For isoconversional methods, the Ozawa-Flynn-Wall (OFW), Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS), and Friedman (FM) models are used. Based on the computed activation energy, pre-exponential factor, and other constants, the thermodynamic parameters are calculated. Finally, a prognosis of matching suitable reaction models to specific biomass conversion rates is also attempted.

2. Theory, Materials and Methods

All analysis were performed using the same CRD wood waste, instrumentation, methods, and by the same technician, like what has been elucidated in Ganesan et al., 2025. The characterization techniques have been explained here again, for clarity.

2.1. Foundational Derivation

Different biomass sources exhibit different reactions due to variability in composition (Zhong et al., 2023). Therefore, an exact determination of reaction kinetics during biomass thermal decomposition is almost impossible (Rambhatla et al., 2024). To understand the pyrolytic conversion of CRD wood into biochar, TGA of this biomass is carried out at same or different heating rates in the presence of a carrier gas (eg: nitrogen, helium, argon, air, oxygen). An effective TGA test can mimick crucial process conditions such as the temperature, BRT, heating rate, and feed particle size that are usually interdepending, operational factors in a pyrolysis process which help in critically determining the composition of resulting products (Fanezouné et al., 2024). Through a kinetic study, the activation energy of a feedstock can be computed to evaluate its reactivity, for estimating its conversion efficiency, and also for scale-up considerations to larger pyrolyzers during the design phase (Patidar et al., 2022).

Rate of reaction for biomass in an isothermal condition is given as:

Here, k is the reaction rate constant, which is temperature dependent, dα/dt is the change in mass of biomass taken for the analysis with respect to time (also referred to as biomass conversion rate), and f(α) is a differential function of conversion rate that is determined and governed by the different orders or mechanisms of a chemical reaction.

In the above equation, α that represents a fractional change in mass of biomass reactant, can be represented as:

Here, x

o is the initial mass of biomass sample taken for the kinetic study by TGA, x

f is the final mass of sample at the end of TGA, and x

t is the mass of sample in the TGA cycle at a given time t. Decomposition rate of biomass as a function of temperature can be construed by the Arrhenius equation as follows:

In the above expression, A is the pre-exponential or frequency factor (s

-1 or min

-1) which represents the extent of molecular collisions in the wake of thermal decomposition at a given time and temperature, E

a is the activation energy required to cleave the bonds between feedstock biopolymers, namely cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (J/mol), R is the universal gas constant (8.3145 J/mol.K), and T is the temperature at which a particular stage of conversion proceeds (K). Upon substituting the reaction rate constant k from Equation 2 within the global one-step Arrhenius expression in Equation 4, we arrive at:

For a specific heating rate (K/min or K/s adopted during TGA, the temperature of the system is ramped up with respect to time and is hence, a non-isothermal process (Note: K/min is also the same as °C/min due to the same magnitude with respect to a common time frame. An increase in K by one unit is identical to an increase in °C by one unit).

By inserting the above heat rate expression and substituting for dt in Equation 5, we arrive at:

Equation 7 can be re-written as:

This serves as the basic expression that could be leveraged for model-fitting and model-free methods to be built further.

2.2. Model-Fitting and Model-Free TGA Methods Rooting from Foundational Equations

Generally, to perform a kinetic analysis and calculate corresponding parameters, TGA can incorporate two approaches: model-fitting and model-free methods, that can detail a thermal decomposition process (Zsinka et al., 2024).

2.2.1. Model-Fitting Methods

As the name suggests, model-fitting method assumes that the experimental data obtained from any thermal decomposition reaction should fit into a pre-theorized model (Arenas et al., 2019). This is where the predicted term f(α) as in the aforementioned equations comes into play, to describe the relationship between the degree of biomass conversion or α and the overall rate of reaction, where only a single heating rate is sufficient. As outlined in

Table 1, various forms of f(α) can take shape according to the type of reaction mechanism chosen for analysis that provide the output values of E

a and A (Postawa et al., 2022, Rambhatla et al., 2024, Patidar et al., 2022, Fanezouné et al., 2024).

Chemical reactions can be classified into first, second, and third order based on how the reaction rate relates to the concentrations of reactants. First-order reactions are reliant on the concentration of a single reactant, second-order reactions involve two reactants, and third-order reactions may include combinations of three reactants or elevated powers of one reactant. In biomass pyrolysis, biopolymers such as cellulose and lignin act as reactants, enabling numerous simultaneous reactions within the biomass. This study emphasizes these three orders, as higher-order reactions are uncommon and necessitate substantial energy to surpass activation energy barriers for multiple reactants to effectively collide. Furthermore, the diffusion mechanism pertains to the rate-limiting step regarding the movement of reactants, intermediates, and products through a medium (White et al., 2011), which can be characterized as one-dimensional, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional diffusion. One-dimensional diffusion occurs in a singular direction, like within linear, constrained porous channels. Two-dimensional diffusion takes place at surfaces or boundaries, while three-dimensional diffusion involves movement in all spatial directions, typical of bulk solid regions. In systems related to biomass pyrolysis, mass and heat transfer are affected by these types of diffusion, which are influenced by reaction time, residence time, and temperature. Phase interfacial reactions occur at the junctions between solids and liquids or gases, influenced by aspects such as adsorption, diffusion, and desorption processes (Pecha et al., 2019). The rate of these reactions depends on factors such as surface area, composition, particle size, residence time, temperature, and the presence of reactive atmospheres. In the process of converting biomass to biochar, heat transfer mechanisms namely, convection from the carrier gas and conduction from the surrounding biomass, are crucial. This conversion can result in the creation of secondary char and pyrolytic volatiles through random nucleation and growth mechanisms, where surface superstructures evolve into new phases that may display isotropic or anisotropic qualities (Zhang et al., 2022). This transformation might depend on how long surface clusters remain on the biochar and the temperature conditions that facilitate repolymerization and polycondensation reactions, akin to the processes seen in hydrothermal carbonization (HTC)-derived biochar (Pfersich et al., 2023). Given its carbonaceous nature, biochar remains inherently reactive and continues to undergo various phase interfacial reactions even after its production, which is evident by its tendency to self-ignite when exposed to heat or air adsorption.

2.2.1.1. Arrhenius Model

From Equation 8, it is important to note that heating rate is brought in here and matters mostly when the temperature profile as a function of time is combined with the Arrhenius expression during non-isothermal reactions. This can be seen in complex reaction models to theoretically simulate real-world thermal depolymerization processes like pyrolysis, gasification, or combustion where how much time a sample is subjected to a particular temperature can alter the conversion rate. Such models also introduce the element of non-equilibrium dynamics such as complex heat transfer mechanisms. On the other hand, the Arrhenius equation alone assumes a steady-state reaction where the temperature during conversion is held constant (isothermal) with negligible changes. In other words, such a setting does not consider, any disturbances introduced to an otherwise equilibrated system. So, to solve for E

a and A, for thermal decomposition of biomass in a system under equilibrium, the heating rate term is dropped and hence, Equation 8 is simplified as:

Here, by applying the natural logarithms on both sides, we conclude with the expression of the basic Arrhenius model:

Plotting

or ln(k) versus (1/T) results in a straight line with a negative slope of (-E

a/R) while the y-axis intercept can be used to directly calculate A (Mahmood et al., 2021). With respect to

, different reaction models and the equations for calculating their corresponding f(α) is described in

Table 1.

2.2.1.2. Coats-Redfern (CR) Model

The CR method is a model-fitting technique used in chemical kinetics to study thermal decomposition of solid biomass matter, irrespective of woody or non-woody nature (Mian et al., 2019). It is being widely used by researchers for analysing the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic materials. The CR model functions as an integral of Equation 1. To understand how we land at the CR expression and for calculation clarity, Fanezouné et al., 2024 states that a primary model function for biomass pyrolysis kinetics can be interpreted as:

where n is the order of reaction (1, 2, 3,….n). Also, unlike the Arrhenius model, the CR model may not assume a steady-state or isothermal model and can function effectively by following different heating rates (β). So, by substituting Equation 11 in Equation 8,

Upon rearranging this equation, it can be formulated as:

Now, introduction of the term g(α), i.e, the integral conversion of f(α) linking the extent of reaction to temperature and time, takes precedence which is based on a specific reaction mechanism encountered by biomass during pyrolysis. Integrating within the limits of α=0 and α=α at T=0 and T=T respectively (Wang et al., 2018, Mishra et al., 2018):

After integrating Equation 14 on the LHS first,

Following the recommendations in Mishra et al., 2018, after integration on RHS, Equation 15 becomes:

From Wang et al., 2018, assuming that

and can be neglected, Equation 17 can be reframed as:

Applying natural logarithms on both sides of Equation 18, we get:

Albeit the above equation is valid for n≠1. According to Chen et al., 2022, pyrolysis of lignin-based solids is a first-order reaction where n=1. Moreover, according to Altynbaeva et al., 2018, CR method adopts the basis of a single-stage first-order reaction during thermochemical breakdown of a solid fuel. Thus, Equation 19 becomes:

By inserting the integral function once again in Equation 20, we can simplify the expression as:

For different reaction models (chemical reaction, diffusion, phase interfacial, nucleation and growth) and associated mechanisms, the corresponding value of g(α) can be used from

Table 1 to calculate kinetic parameters. Plotting

versus

gives a straight line with a negative slope equivalent to

. With the known value of E

a, it is possible to calculate A using the y-axis intercept

.

Four key shortcomings of model-fitting methods are: a) The value of Ea is subjected to heavily depend on the reaction model assumed when in reality, there is significant possibility of a process to manifest itself by several other models; b) Secondly, if the wrong model is chosen, the reliability of the measured kinetic parameter value can be questionable; c) Thirdly, a model-fitting method like CR may function harmoniously only at one specific heating rate at a given time where different reaction mechanisms can be tested under one roof for satisfactoriness rather than several heating rates simultaneously as in iso-conversional models; d) Fourthly, despite providing an overview of Ea under many assumed models, it is a highly time-consuming method. Henceforth, while using model-fitting methods, it is advisable to assume as many reaction models as possible to help in quantitative analysis of Ea from more than a single perspective. In fact, it may be safe to say that convoluted processes such as pyrolysis can exhibit a myriad of simultaneous (parallel), sequential or both types of reactions at once. When using this approach, it could be possible to also narrow down on the ideal model using correlation coefficient (R2) and simple cross-comparison.

2.2.2. Model-Free or Iso-Conversional Methods

Model-free kinetic methods do not assume that a chemical reaction progresses as per a pre-selected model under only a single heating rate. It considers the possibility of addressing complex chemical reactions at multiple heating and conversion rates (Emiola-Sadiq et al., 2021). Here, different values of α (ranging from 0-1) are used to calculate Ea without the necessity for g(α) intervention, thereby, offering greater flexibility to the method (Najafi et al., 2024). It is here that common slow pyrolysis heating rates are employed (10-40°C/min in our case) in the presence of nitrogen to detect variations in Ea at each stage of α. Different values of α are obtained at different phases of pyrolysis due to which kinetic parameters under variable heating rates need to be compared and fitted separately one after the other (Chen et al., 2022). In other words, we will be plotting for one α value (eg: α=0.1) at all four heating rates (10, 20, 30, and 40°C/min), proceed to the next conversion value (eg: α=0.2) at the four heating rates, and so on till α=1. Variations in extracted Ea for instance, may indicate that biomass decomposition in a pyrolysis-like setting encompasses an interplay of many different reaction mechanisms and not just one that improves overall dependability and robustness of the derived values of Ea. Although it is not necessary to use g(α) to calculate Ea, model-free methods do need this function to calculate A and still depend upon a specific reaction model and mechanism. This is without a doubt, a notable drawback of model-free methods that accentuates a limitation towards fully characterizing both kinetic parameters without the role of assumptions. Also, model-free methods are criticised since they are too simplistic and general in describing a complex process like pyrolysis (Fanezouné et al., 2024).

There are different model-free methods used in practice of approximating E

a of pyrolysis reactions like FM, KAS, OFW, Vyazovkin (VZ), and distributed activation energy model (DAEM) that forge high simplicity during calculations. Among these, FM, KAS, and OFW will be used in this study as representative methods. They are appreciable to analyse complex reactions as a function of biomass conversion value, α. From the expressions studied in Mishra et al., 2020 and Li et al., 2022, the following

Table 2 illustrates the expression for these methods, values of constants/variables, and the procedure for plotting to evaluate kinetic parameters.

2.3. Thermodynamic Study

During pyrolysis, thermodynamic parameters such as ΔH, ΔS, and ΔG are calculated using the following equations adapted from Singh et al., 2021.

In the above equations, Tm is the maximum thermal decomposition temperature of CRD biomass that was obtained from DTG curves at each heating rate (10-40°C/min). Ea is the activation energy derived using isoconversional models of OFW, KAS, and FM at each heating rate and conversion stage. Pre-exponential factor, A, was also calculated from the respective plot using the intercept. KB is the Boltzmann constant of 1.38110-23 J/K and h is the Plank’s constant, 6.62610-34 J/s.

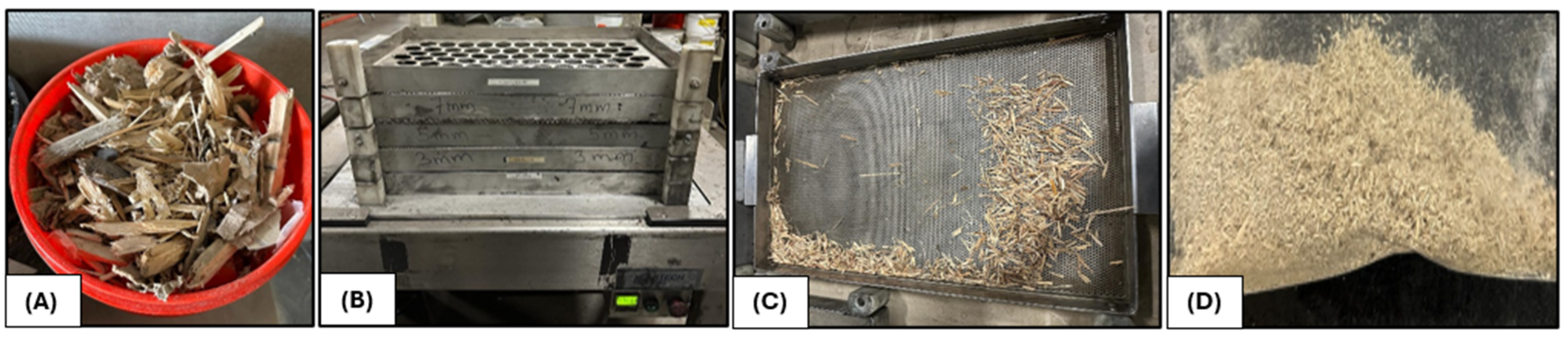

2.4. CRD Biomass Sample Preparation for Characterization and Kinetic Analysis

Non-recyclable CRD wood sourced from "BRQ Fibre et Broyure" in Trois-Rivières, Québec, was delivered in pails to the Innofibre facility

Figure 1 (A). After being collected, the CRD wood underwent mechanical sieving using a Labtech vibrational sieving unit to separate it into different particle sizes (>4.5 cm till >0.3 cm) after screening and removal of contaminants

Figure 1 (B). In fact, no washing was performed due to the risk of creating contaminated wastewater from the leaching of impurities present in the CRD wood. Once the size separation was completed, the selected biomass fraction in

Figure 1 (C) was dried for an entire night at 105 °C. Given that sieving only led to particle sizes of up to 0.3 cm, it was necessary to mill the CRD wood further. A Retsch SM300 mill (3 kW motor and rpm: 100-3000), featuring a high-speed tungsten carbide rotor and screens with openings as small as 500 µm, or a Thomas Wiley mill with a similar mesh size, was utilized to produce fine particles as in

Figure 1 (D) from the biomass for subsequent analysis.

2.5. Physicochemical Characterization

Proximate analysis was employed to evaluate ash content, volatile carbon (VC), and fixed carbon (FC) in biomass. For the ash measurement, 1 g of dry biomass fines was placed into a crucible and heated in a muffle furnace with a similar procedure as in ISO 1171. Beginning at room temperature, the sample was heated to 106 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and maintained at this temperature for 1 hour to ensure the removal of residual moisture and volatiles, then the temperature was increased at the same rate from 106 °C to 550 °C, where it was held for a duration of 2-4 h. The sample was then allowed to cool to room temperature in a desiccator to prevent any hygroscopic effects, after which the ash was weighed to ascertain the proportion of biomass remaining. For volatile carbon, 1 g of dry biomass fines was subjected to heating at 900 °C for 7 minutes in a sealed crucible, after which it was cooled and weighed to quantify the carbon lost. VC is utilized in certain contexts in this study to specifically refer to labile carbon, distinguishing it from other volatile components. FC was calculated using the relation: FC = 100 − (VC + ash), as weight percent dry basis (wt%DB), where VC and ash will also be represented as wt%DB (Armynah et al., 2019).

For the elemental analysis, an Elementar Vario Macro Cube examined 1-200 mg of dry biomass fines for elements such as carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur, utilizing helium (purity >99.996%) as the carrier gas and oxygen (purity >99.996%) for combustion up to 1200 °C. The oxygen content was determined by calculating the difference from 100%, using the percentages of all individual elements and ash, as given in: [. It is derived from Nzediegwu et al., 2021.

The higher heating value (HHV) of CRD biomass was determined using a similar approach outlined by Channiwala & Parikh, 2022. This approach correlated the calorific value with elemental composition of the biomass sample obtained through elemental analysis. For metal detection in biomass, an Agilent Technologies 4210 Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (MP-AES) was utilized, which featured a nitrogen fuel source and an SPS 4 autosampler. This apparatus allowed for the simultaneous analysis of multiple elements by aerosolizing the biomass sample into a nitrogen plasma to produce monoatomic ions. The device guaranteed accurate measurements of the inorganic content by completely digesting the organic materials found in the biomass.

2.6. Composition Analysis

The presence of extractives, structural carbohydrates, and lignin in CRD biomass were analyzed according to the laboratory analysis procedures mentioned in the reports NREL/TP-510-42619 and NREL/TP-510-42618, respectively.

2.7. FTIR

The distribution of surface functional groups in biomass was examined using an Agilent Technologies Cary 630 spectroscope, with Microlab PC software for operation. About 1 g of dry biomass fines was placed on a diamond crystal surface that was regularly cleaned with ethanol. The analysis was performed in transmittance mode over a spectral range of 500–4000 cm⁻¹ to determine the chemical bonds present in the material. Baseline and peak corrections were applied to the obtained spectra, followed by signal smoothing.

2.8. TGA

In order to examine the weight loss pattern of biomass in relation to temperature, a PerkinElmer TGA 8000 analyzer was utilized. This device was also able to assess proximate analysis parameters such as moisture, VC, FC, and ash. Only 8 mg of biomass fines in their original, non-dried state were needed per vial for the analyzer. Since TGA was leveraged to analyze the pyrolysis kinetics of CRD wood, the process gas used during heating was compressed nitrogen with a purity level exceeding 99.996%. The system was capable of accurately reaching temperatures up to 1200 °C with adjustable heating rates. For this research, 10, 20, 30, and 40 °C/min were employed, reaching a maximum temperature of 900 °C to investigate the transformation of biomass to biochar. Differential thermogravimetric (DTG) curves were generated by differentiating the weight loss features from the original thermogram in relation to time and plotting them against temperature. This led to the identification of different peaks indicating the points of maximum weight loss or melting of the sample during TGA, along with the corresponding temperatures, providing insights into biomass chemical composition and hydrocarbon structure.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of CRD Wood Comparative Analysis with other Biomass Feedstock

The proximate and elemental parameters of CRD biomass were analyzed as shown in

Table 3 Elemental composition, particularly carbon content in CRD wood, resembled hard woods like beech and poplar at 49-50% despite containing softwood residues in the bale. In terms of carbon content, MSW outperformed all the feedstock with carbon content at 76.26% due to a heterogeneous composition involving plastics and other hydrocarbon-rich residues. Oxygen (41.74%) and hydrogen (6.12%) were also equivalent to the ranges in hard wood species. These bolster the role of CRD biomass to be used in bioenergy applications for the production of biofuels, biochemicals, and bioproducts. Low sulfur (if any, from gypsum dust) and nitrogen content in CRD wood also mean that the release of NOx and SOx could be starved during pyrolysis. For proximate parameters, CRD wood is a low-ash biomass at 1.17% relative to high-ash agricultural residues like rice husk at 14.20% or medium-ash sources like MSW (8.26%).

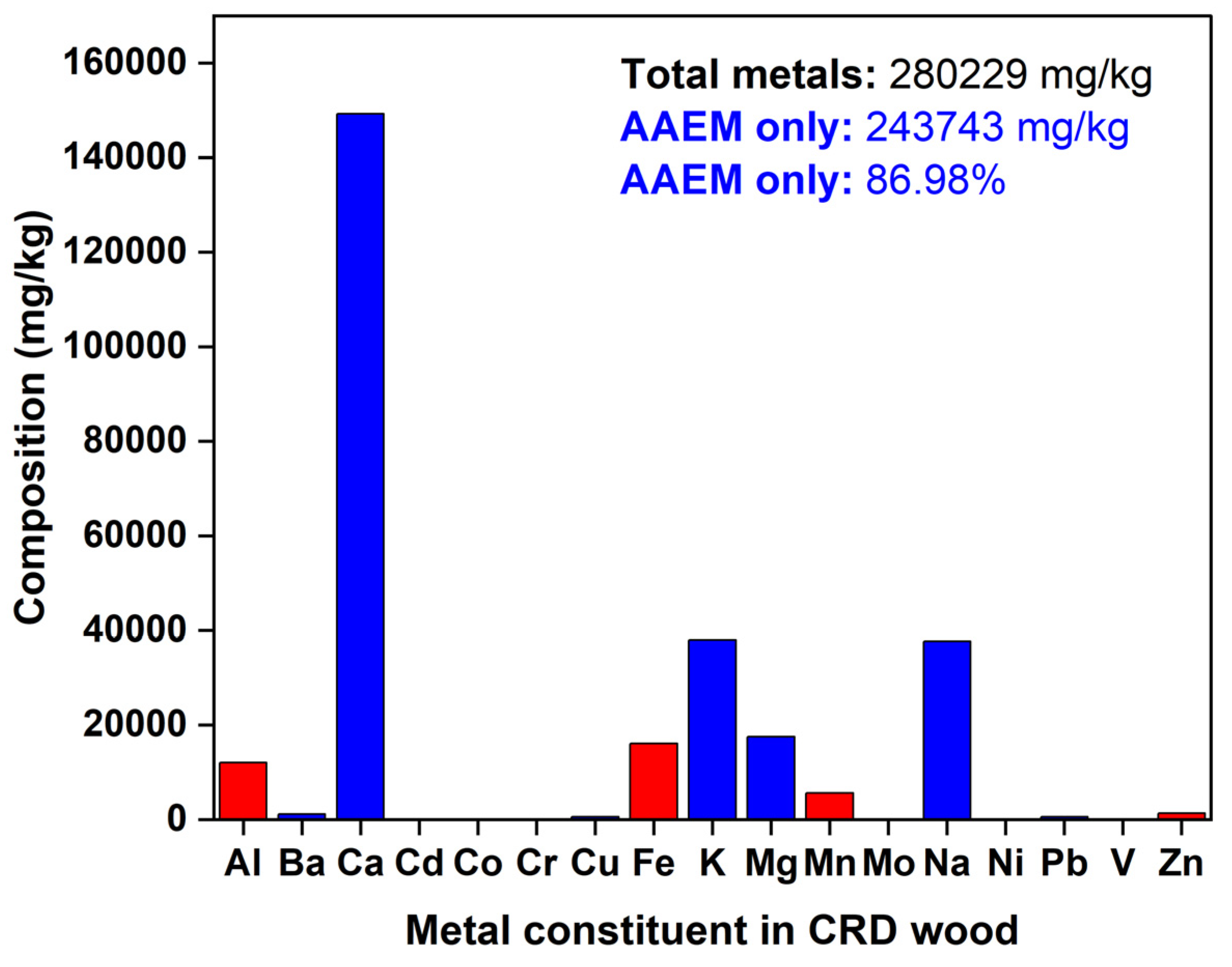

However, as delineated in

Figure 2, the metal content in CRD wood, mainly alkaline and alkaline earth metals (AAEM) (86-87%), was very high which may result in secondary reactions by acting as indirect catalysts leading to excess loss of carbon or could cause technical snags in reactor equipment through slagging, fouling or bed agglomeration (Wang et al., 2022, Cao et al., 2023). But, among AAEM, alkaline earth metals like Ca, Ba, and Mg constituted for 59.96% whereas alkaline metals made up just 27.03%. So, there could be a possibility where the melting of ash may be pushed towards relatively higher temperatures since presence of divalent species dominated this AAEM fraction. On the contrary, the other possibility with high AAEM could be secondary char formation (Liu et al., 2025). Grafmüller et al., 2022 stated that AAEM, when present with woody biomass, under pyrolysis temperatures of 350-750°C, may increase the yield of biochar through secondary reactions. This holds true for an AAEM-rich feedstock like CRD wood. Additionally, CRD wood contains some heavy metallic contaminants like Cu, Cr, and mild levels of As. Other heavy metals detected were mainly Zn and Pb. All these metals are part of preservatives, paints, varnishes, roofings, and surface coatings in conditioned CRD wood that are usually part of residential buildings, electricity poles, and hand rails dating back to 1960s-1990s. The VC in CRD wood (82.35%) matches VC in poplar (83.60%) and beech (84.87%) confirming highly decomposable fractions. Also, due to high volatiles and low ash, woody biomass could produce biochar product with high FC (Elhenawy et al., 2024). Also, due to the lower ash content that minimizes presence of non-combustible materials, HHV of CRD biomass is relatively high at 20.28 MJ/kg rendering it suitable for bioenergy applications (Nhuchhen & Afza, 2017). On the contrary, a high ash rice husk had a low HHV at 14.09 MJ/kg. Wheat straw with moderate ash also had a low HHV of 15.29 MJ/kg. Another pattern observed is that as volatiles increase, HHV decreases due to the non-availability of stable carbon. This was true for MSW (51.13%) and pinewood (64.37%) relative to CRD wood (82.35%), where the increase in volatiles decreased HHV from 29.70 MJ/kg, 22.33 MJ/kg, and 20.28%, respectively.

3.2. CRD Wood Compositional Analysis

To achieve a representative and robust analysis of CRD wood biomass received, samples from four different sections of the pail, post-sample preparation steps, were subjected to compositional analysis. Percentages of extractives, holocellulose and lignin were listed in

Table 4, which may explain the nature of biomass transformation to biochar. Extractives soluble in hot water and ethanol ranged from 2-3.5% and 2.5-4% respectively, that are usually eliminated as volatiles. Since total lignin varied from 24-31%, it is conclusive that CRD wood is composed of both hard and softwood and may be called together as ‘wood waste’ that has a comparable lignin content, recorded at 28.9% as in Li et al., 2024. From Yildiz et al., 2025, biochar produced from agriculture wastes like buckwheat husk (holocellulose: 73.72%, lignin: 24.73%), spent coffee grounds (holocellulose: 31.58%, lignin: 23.65%), hazelnut shell (holocellulose: 62.31%, lignin: 28.30%), and waste grass biomass like hemp (holocellulose: 25.81%, lignin: 20.69%), miscanthus (holocellulose: 63.11%. lignin: 25.48%) were also compared. Greater the lignin, more the structural complexity due to the presence of aromatics, and greater may be the biochar yields (Dhyani & Bhaskar, 2018). However, lignin content in biochar is not a solely conclusive indicator of mechanical strength/integrity and yield of biochar (Gurtner et al., 2023, Dufourny et al., 2019). Although, lignin, if softened and melted to form condensed aromatic structures, the overall bulk density and resistance towards breakage may increase (Wang et al., 2022). Carbon content and stability of biochar could be largely conserved as well. Total holocellulose content in CRD wood varied from 68-77%. With six-carbon sugars like glucose (44-54%), galactose (0.5-2.5%), mannose (2-10%) and five-carbon sugars like xylose (8-24%), arabinose (0-1.5%), hemicellulose decomposition in CRD wood to pyrolysis gases at lower temperatures is plausible. The overall contribution to char formation is low for hemicellulose. Cellulose decomposition could favor both condensed volatiles and intermediates (high temperatures) and some char (lower temperature) formation. It is determined by the temperature, BRT, and heating rate employed during the process (Xia et al., 2021).

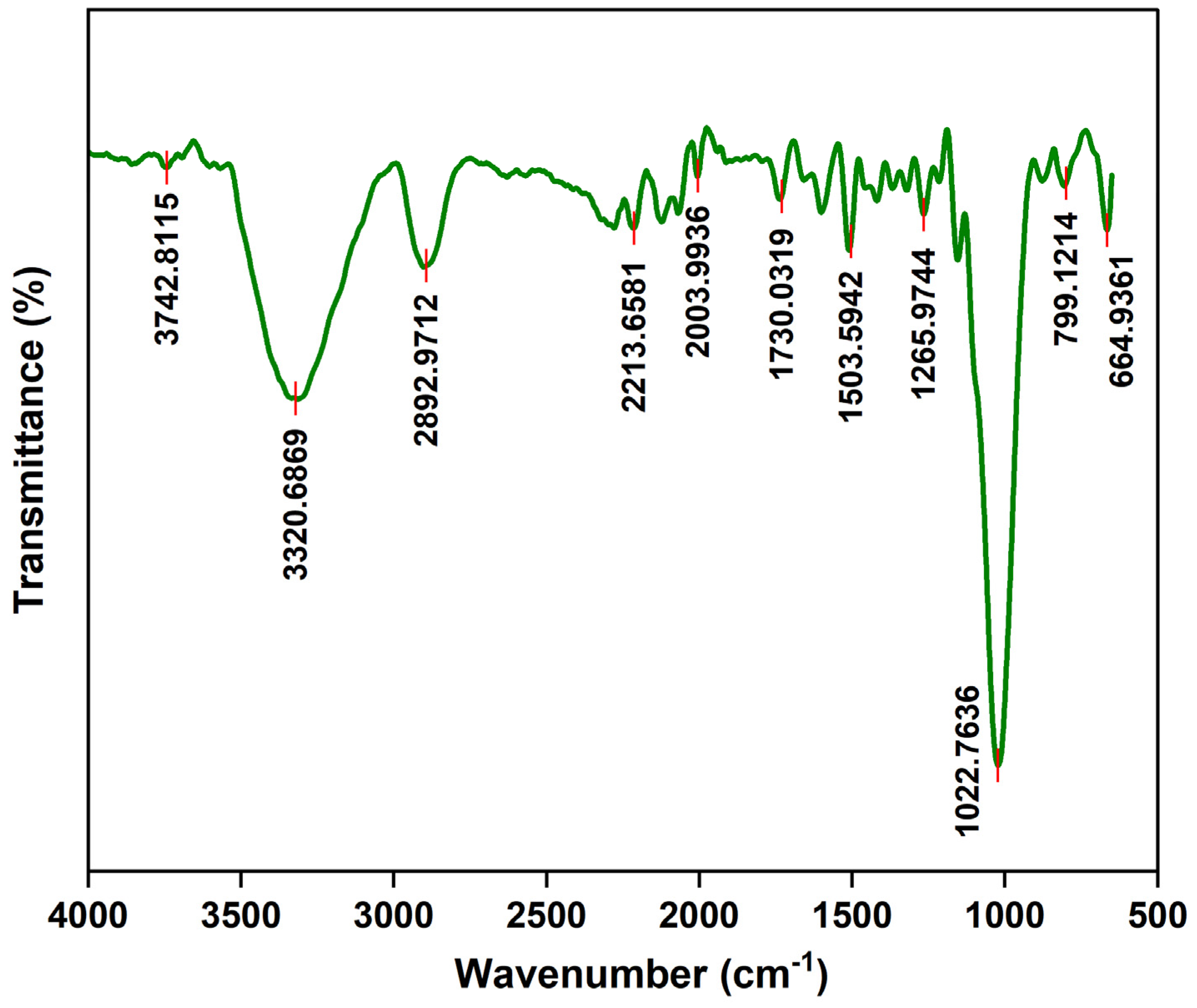

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis

FTIR spectral distribution of the CRD wood biomass is shown in

Figure 3. A high concentration of specific functional groups in the CRD biomass feed is denoted by strong transmittance peaks of infrared light through the sample which demonstrate specific vibrational patterns: stretching or bending. Spectral band assignments from Johnston, 2017 and Nanda et al., 2013 were used to match the transmittance peaks in CRD biomass to relevant functionalities. Firstly, the distinct peak at 3320 cm

-1 indicates O-H stretching vibrations as in moisture, carboxylic acids, alcohols, and phenols. Secondly, the distinct peak at 2892 cm

-1 could signify C-H stretching in aliphatic hydrocarbons as in alkanes that are subunits of most biomass polymers. Thirdly, the spectral band at 2003 cm

-1 highlights stretching vibrations in alkynes (C≡C) that may be ascribed to polyaromatics with maximal carbon condensation. Next, carbonyl stretch (C=O) in aldehydes, ketones, esters, and carboxylic acids appears around 1730 cm

-1 that stem from hemicellulose in CRD wood. Actually, this contributes to the loss of biomass carbon as CO and CO

2 during the onset of pyrolysis. A subdued peak at 1503 cm

-1 and 1265 cm

-1 means there are faint aromatic C-C and aromatic C-O ring stretching actions respectively, amidst the biomass carbon skeleton. Methyl, methylene or methoxy groups of biomass lignin also exhibit these vibrations owing to the presence of dense organic residues in biomass. A sharp band at 1022 cm

-1 may be due to C-O stretching in aliphatic ethers (C-O-R) and alcohols (C-O-H) that are key building blocks of carbohydrates/polysaccharides. The 799 cm

-1 band could be an extractive in biomass showcasing the C-H bend in alkynes, phenyl rings, or aromatics followed by the band at 664 cm

-1 stemming from C-H vibrations in alkenes.

3.4. TGA Analysis and Effect of Heating Rate

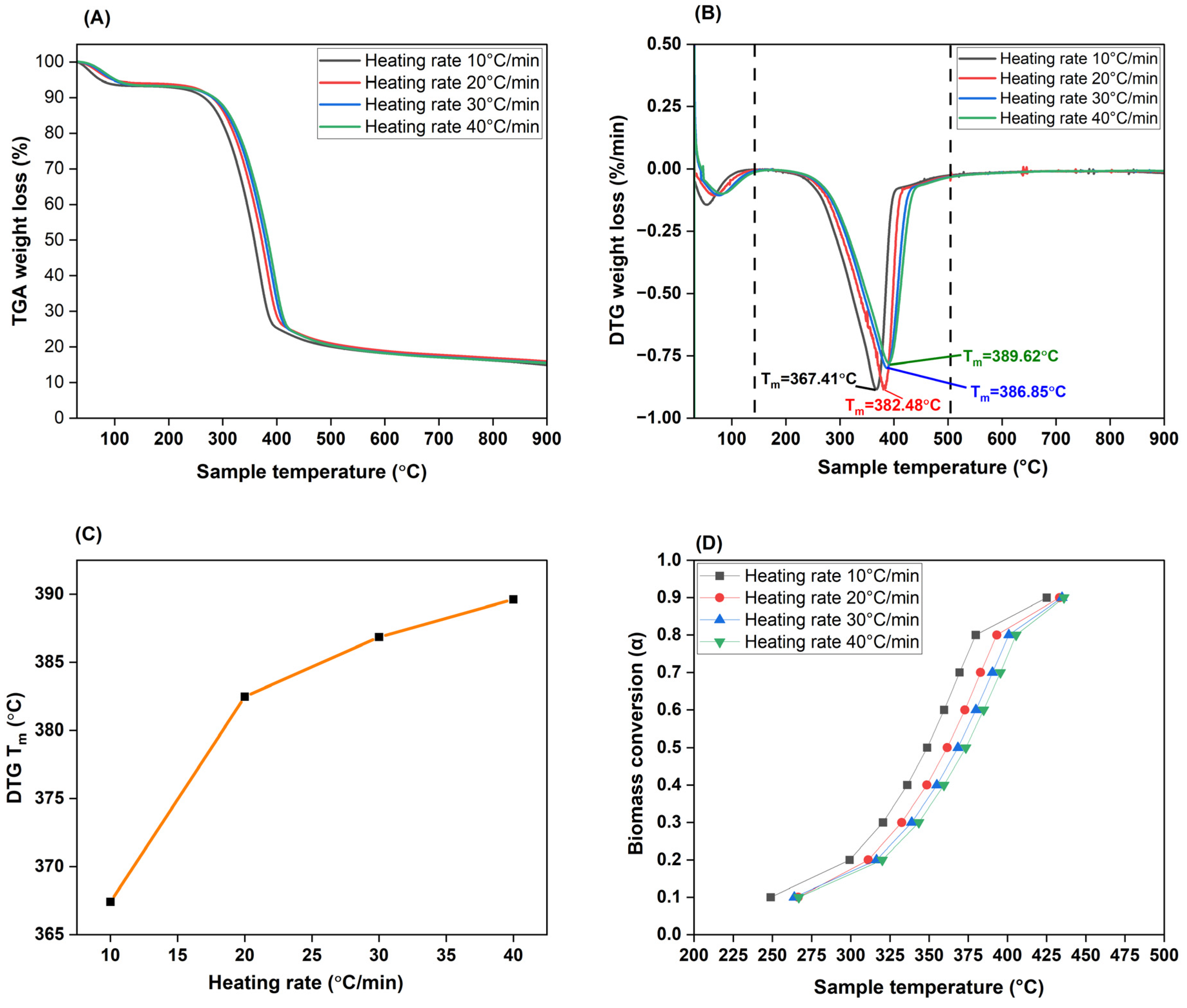

The thermal stability of CRD biomass was verified by TGA and DTG curves. The weight loss exhibited by biomass under four different heating rates: 10, 20, 30, and 40°C/min along with their stages of thermal degradation under an inert nitrogen atmosphere mimicking pyrolysis, are studied as in

Figure 4. From the TGA plot in

Figure 4 (A), it is evident that an increase in heating rate pushes the degradation temperature slightly higher (to the right) as reported in Mukherjee et al., 2021. This is because, an increase in heating rate means that there is less time for heat to permeate from the surface to the core of the biomass particle and that too, only non-linearly. So, the weight loss encountered is restricted as a surface effect rather than occurring throughout the particle and is hence low. At a lower heating rate, an inverse phenomenon where there is gradual heat transfer that devolatilizes biomass constituents to fruition under an ample time frame, is clear. Biomass’s outer layer and the core inside reach almost similar temperatures, allowing a linear thermal behaviour. This is validated by maximum weight loss (72.73%) between 200-400°C for the heating rate of 10°C/min followed by 69.45%, 64.95%, and 60.85% for the heating rates 20, 30, and 40°C/min respectively. However, despite an increase in heating rate by every 10°C/min, the profile for degradation curves is unchanged, as concurred from Raza et al., 2023.

If we look more closely at the DTG peaks for these heating rates, weight loss happens in three stages. The first stage occurs <150°C where evaporation of moisture and other surface bound volatiles occur. Around 5-7% weight loss happened here. As seen in

Figure 4 (B) (C), within the second stage from 200-400°C, melting temperatures of biomass (T

m) for each heating rate is observed to increase with increase in heating rate (367.41°C for 10°C/min to 389.62°C for 40°C/min) validating our earlier finding that greater BRT at that specific temperature means that there is adequate time for biomass to experience loss of structural integrity by efficiently exposing its biopolymers for cleavage, signifying an ongoing pyrolysis process. This region encompasses extractives, VOCs, hemicellulose, and cellulose breakdown respectively with peak decomposition mainly between 350-400°C. Since cellulose is a straight chain, crystalline polymer, it needs greater energy to collapse and hence, disintegrates after relatively less-stable hemicellulose degrades to a large extent. Biomass carbon (eg: carbon loss via CO

2 and CO) and heteroatom (eg: H

2S, SO

2, NH

3) rejection reactions from holocellulose followed by the simultaneous heat uptake to initiate destabilization of lignin aromatics (eg: phenols) are key reactions that increase gas and condensible volatiles yield. From the conversion (α) plot in

Figure 4 (D), we can see that 80% (α=0.8) is completed around 400°C. In this second stage, profound mass loss of 60-73% took place. Beyond this point, the third stage of decomposition is rather slow and proceeds well-spaced out due to complex lignin fractions and other heavy molecular weight compounds. Moreover, since CRD wood contains noticeable AAEM and other metals/inorganics in its ash fraction, that could be stable up to a certain level and delays breakdown. This is when char generation peaks due to both primary and secondary pyrolysis reactions. It is safe to say that no additional peaks were observed which means that significant degradation of inorganic material may not be accounted for. At the end of the process, about 20% of initial mass of CRD wood remains. All in all, there was another interesting observation. At higher heating rates of 30 and 40°C/min, decomposition peaks appear to overlap which indicates that degradation of biomass polymers may not be completely separated processes and could occur sharply within a narrow temperature range, and as synchronous steps. As concluded by Gonzalez-Aguilar et al., 2022 and Mukherjee et al., 2021, the thermal decomposition patterns remained fairly consistent across all the heating rates tested.

3.5. Kinetic Analysis of CRD Wood Pyrolysis

3.5.1. Model-Fitting Method

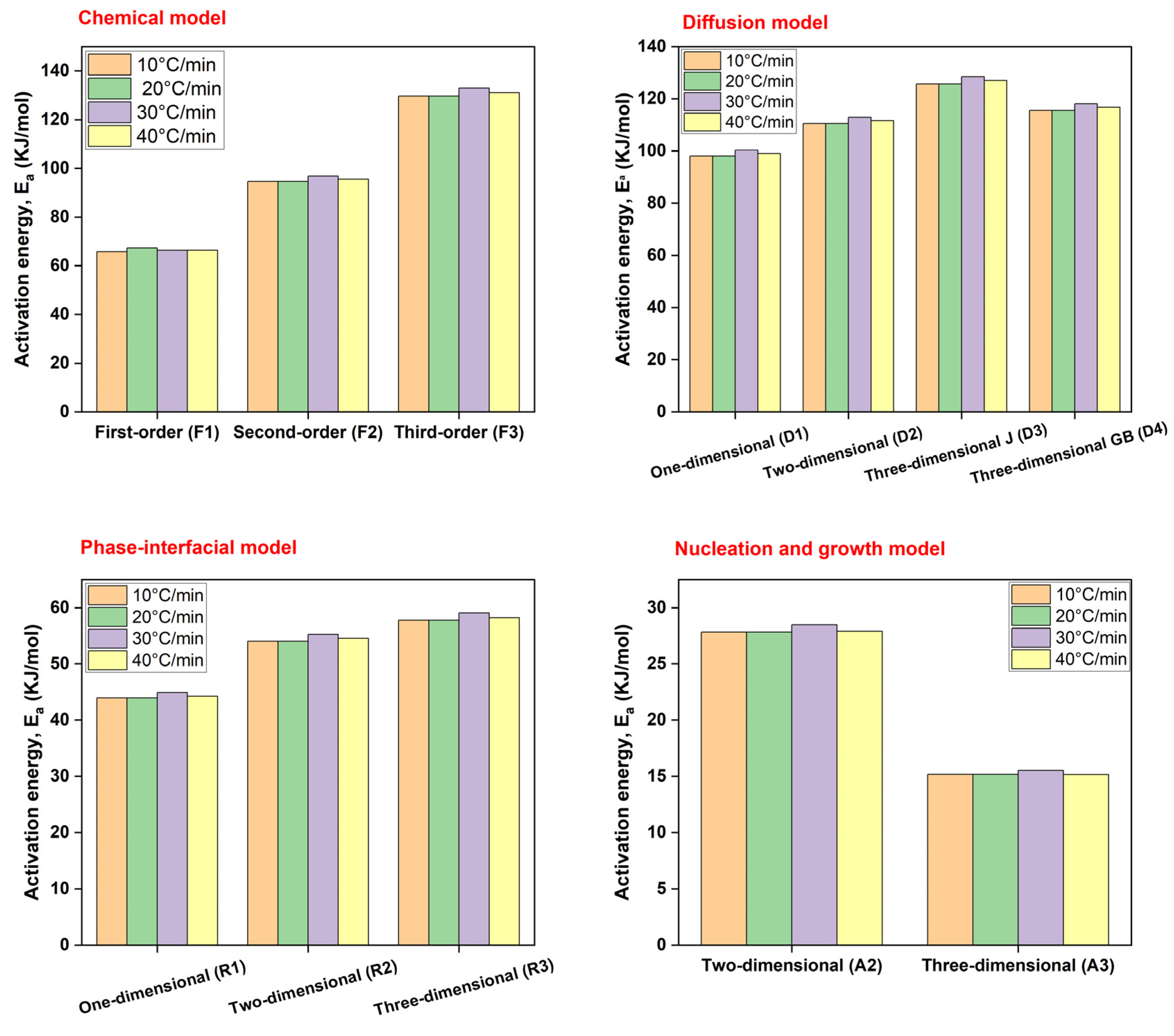

Being a model-fitting technique, the CR method fits TGA data of biomass pyrolysis to various kinetic models for calculating the activation energies and pre-exponential factors. The calculations in

Table 5 surrounded all models discussed in for the four different heating rates, i.e, 10-40°C/min. The correlation factor (R

2) was used to judge the probability of each reaction model being interplayed. From the 12 models analyzed, the average activation energy calculated was 78.22 KJ/mol for 10°C/min, 78.35 KJ/mol for 20°C/min, 79.94 KJ/mol for 30°C/min, and 78.97 for 40°C/min. No marked increase in activation energy existed between different heating rates, although it was maximum for 30°C/min as shown in

Figure 5.

For chemical reaction models (F1, F2, and F3), an increase in reactants necessitated either higher temperature or reaction time because of a high activation energy demand. This is to overcome any heat or mass transfer limitations during pyrolysis attributed mainly to the rampant molecular collisions within CRD biomass contributing to complex, overlapping reactions. It ranged from 65-68 KJ/mol for F1 to 129-133 KJ/mol for F3 as heating rate increased, indicating energy-intensive heterogeneous structures competing in the reaction. This is supported by a concomittant increase of the pre-exponential factor as well. However, average R2 is between 0.92-0.98 suggesting a relatively lower correlation of these reaction models w.r.t. their counterparts. Due to the highest activation energies recorded for F3 (more than any other reaction model tested), it may be possible to assign its role for higher conversion stages (α > 0.6) too where a thorough rearrangement of biochar’s chemical structure is probable as concluded by Calin et al., 2024.

For the diffusion model, activation energies collectively ranged from 98-129 KJ/mol with a dominant effect from linear (D1), planar (D2), and spherical (D3) diffusion mechanisms. These models dominate the thermochemical data of CRD wood as extrapolated from the findings in Dhaundiyal et al., 2018. Average R2 is > 0.99 highlighting their pivotal part in thermal decomposition where migration of volatiles and pyrolysis products could happen through porous channels and at the boundary layers. Diffusion was deemed suitable for coconut shell feedstock with a comparable activation energy of 68.9 KJ/mol granting appreciable bioenergy potential (Monir et al., 2024). A high correlation factor for diffusion model was also shown for feedstock like wood sawdust and wheat straw (Saleem et al., 2024). In case of any energy applications for CRD wood, D1, D2, and D3 models may govern the diffusion of ambient air/oxygen and volatile matter that initiate ignition and proceed till final combustion. This concept was also proposed by Hadey et al., 2020. As in Hassan et al., 2024, D3 model showed the highest activation energy for pyrolysis of MSW which could contain easily decomposable constituents. Whereas, in CRD wood D3 model (125-129 KJ/mol with R2 > 0.99) corresponded to a high activation energy for carrying forward diffusion within constricted spaces, especially upon clogging of porous channels with residual tar. It may also mean that surface-based diffusion has lower resistance and takes place more freely until an intermediate or product layer forms that impedes any progress. Due to high activation energies overall, F3, D1, D2, and D3 models can be attributed to the second (200-400°C) and third (400-600°C) stages of the TGA cycle where majority of disintegration reactions happen for CRD wood pyrolysis. An average activation energy of up to 84 KJ/mol was obtained by Tariq et al., 2023 for almond shell pyrolysis using CR method where the decomposition reactions occur in the range of 150-550°C as well. All these results were commensurate with CRD wood.

The occurrence of phase interfacial

reactions (R1, R2, R3) are also explainable due to a high average correlation of

> 0.99. The results here are comparable to Sobek & Werle, 2020 where D3 and

R3 majorly drove the biomass decomposition along with F1, F2, …Fn. This

means that decomposition of biomass could begin from the surface towards the less-reacted,

unconverted core. As a result of constant interaction between reactants and products

at an interphase, product layers are formed and sequentially shift from the outside

to the inside of the biomass particle. This is why biochar production is favored

at lower heating rates since it allows sufficient time for this gradual conversion.

Activation energy here was lower than chemical reaction and diffusion models, at

43-60 KJ/mol. Finally, only less energy (15-30 KJ/mol) was needed for secondary

pyrolytic intermediates and product formation through A2 and A3 nucleation mechanisms

(R2 = 0.97-0.99). For this mechanism, inherent AAEM and other inorganics

may have coincidentally aided in secondary charring and volatiles formation by behaving

as catalysts.

As depicted in

Figure 5, a notable difference in activation energies existed only at a heating rate of 30°C/min that may signify maximum conversion at this point unlike the ideal TGA curves where thermal decomposition temperatures increased closely (367-390°C) with step-wise increase of heating rate owing to reduced depolymerization time especially near the less conductive core. Same trends were observed for all other models too. Raza et al., 2023 reported a similar finding where activation energies increased till a specific heating rate after is stabilized or dropped. Although, this could be the case only till the maximum conversion is attained after which activation energies may decrease. This was also concurred from Mishra & Mohanty, 2018. On the whole, since each reaction model has a different but reasonably high correlation factor (R

2 ≥ 0.92) and variable activation energies, it is difficult to assign the most suitable pathway mainly because pyrolytic decomposition of biomass could be viewed as a simultaneous process rather than being assumed as an individualistic system. This was exactly proved by Mian et al., 2019.

3.5.2. Model-Free Methods

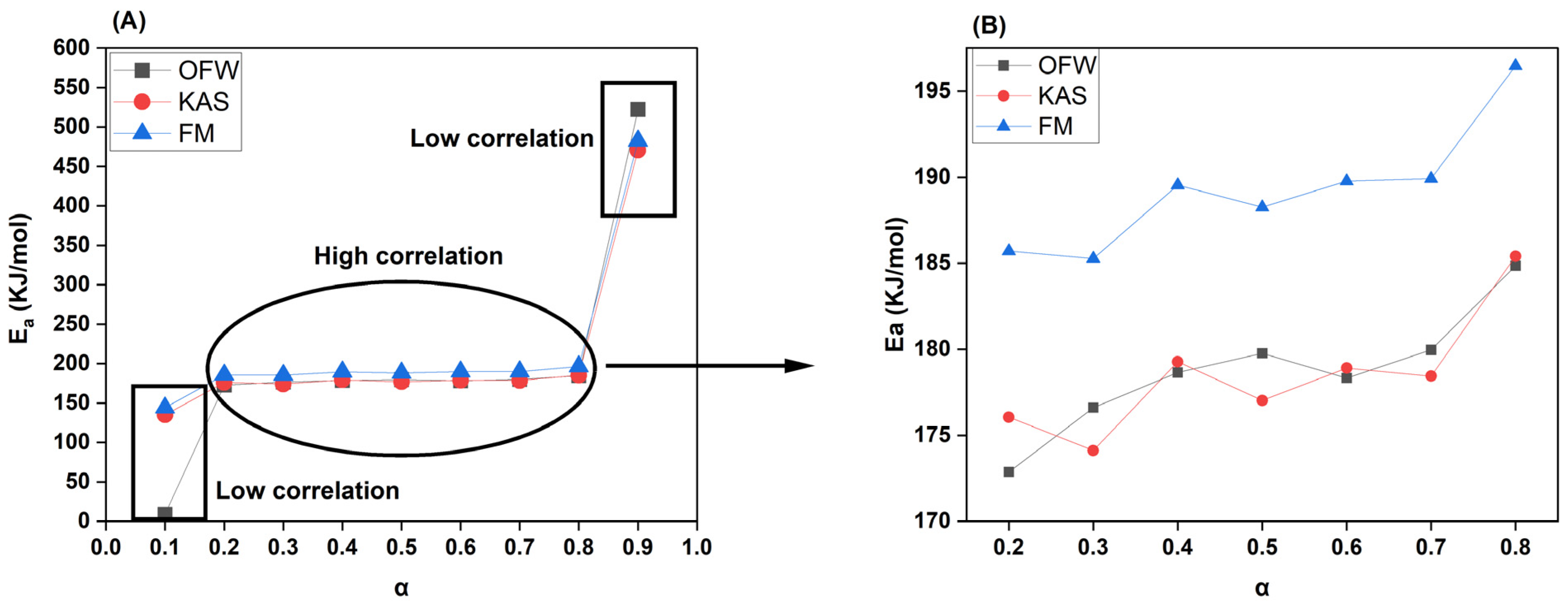

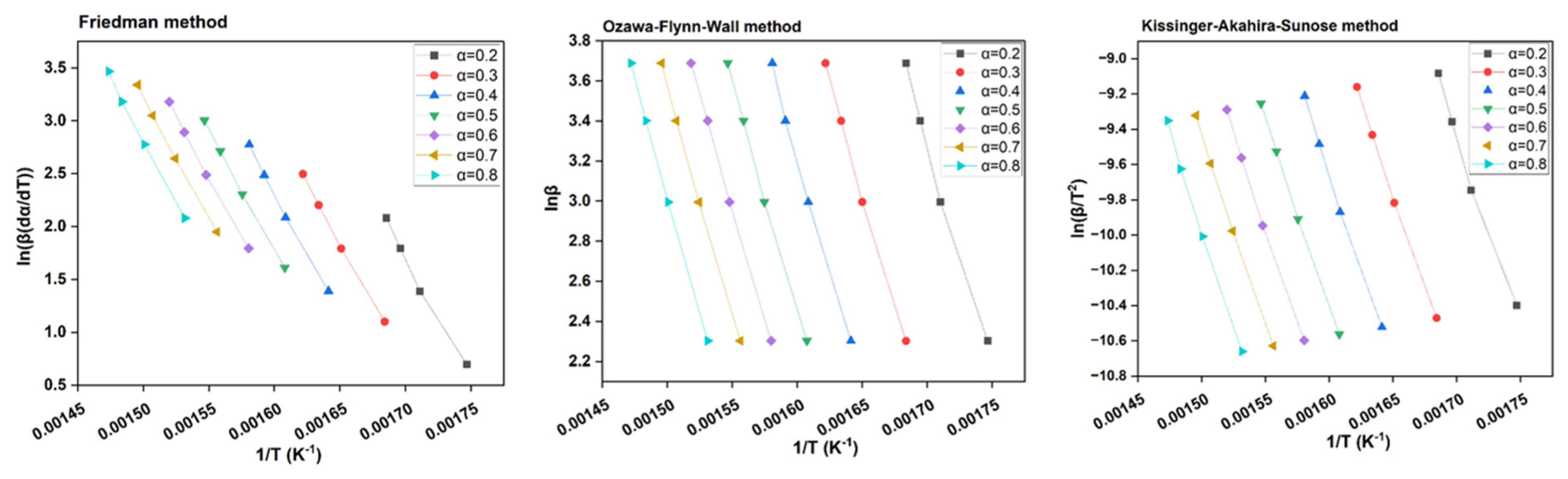

Model-free or isoconversional methods like OFW, KAS, and FM did not rely on any pre-determined reaction models for computing variable activation energies of biomass pyrolysis reactions (Fischer et al., 2024). Instead, biomass conversion rate or α was relied upon for thermal degradation studies. However, as outlined in Shrivastava et al., 2023, isoconversional models have limitations wherein they assume only a single-step reaction and could neglect the role of competing reactions. On the other hand, kinetic analysis of CRD wood by CR method proved that competing reaction models are plausible for a thermochemical process like pyrolysis. A kinetic analysis, whether performed using model-fitting or model-free methods, considers biomass particles that weigh between 6-8 mg, i.e, very small. Henceforth, the temperature on the surface can reach the centre of the same particle within a short time frame that disregards any heat transfer limitations. However, in actual pyrolysis reactors, the particle sizes of biomass can increase from a few cm to several inches and to even logs. This is where the importance of heat conductivity is compromised, but in reality, the temperature requirements rise drastically to satiate high activation energies for biomass conversion. Thus, a TGA-based study may mostly function depending upon kinetics only and could often overlook particle size, heating rate, composition of biomass (percentages of holocellulose and lignin), and the externalities caused by them. From

Figure 6, KAS and OFW plots together, seemed to slightly differ from FM plot.

For reference, the calculated kinetic parameters with the model correlation for each conversion stage is listed in

Table 6. For this tabulation, α > 0.8 and α < 0.2 were not considered due to relatively low R

2 (0.41-0.64 for α = 0.1; 0.90-0.93 for α = 0.9) and non-linearity. For other conversion rates, R

2 is > 0.99 except for α = 0.2, under KAS and FM methods (R

2 = 0.98). A high correlation means that activation energies derived at these conversion rates using the three methods are accurate and dependable. The activation energies under OFW, KAS, and FM methods for α = 0.2-0.8 ranged from 172-185 KJ/mol, 176-186 KJ/mol, and 185-197 KJ/mol, respectively. This work discovered very minimal differences between overall activation energy requirements, along with increase in heating and conversion rates which may suggest fairly quick chemical reactions for activated intermediates formation, as stated in Bisen et al., 2024. An α = 0.8 showed the highest activation energy since the decomposition in this phase may have occurred against highly stable aromatics in lignin and resolute inorganics/AAEM in ash.

FC in CRD biomass at 16-17% could also be targeted for decomposition during this stage. A significant difference in activation energy between each conversion rate was not observed since they varied very narrowly just like the TGA curves. Moreover, there was no defined increase in activation energy, and it was more or less adopting a partly sinusoidal pattern. These fluctuations could be due to complex multi-step reactions as discussed in Patidar et al., 2022. We may, hence, infer that 82-83% of VC in CRD biomass’s holocellulose component could be targeted from α = 0.2-0.7. A momentary jump in E

a could indicate that VC in biomass was either from heavier lignin bridges or was part of an organo-metallic linkage (eg: Fe-O-C; AAEM-O-C) which demand high energy for cleavage. These are confirmed by FTIR and SEM analysis which show the presence of a myriad of functional groups and metal content co-existing with biomass carbon and manifesting different degradation behaviours. Since the activation energy crosses 170 KJ/mol even at an initial conversion rate of 0.2, we may conclude that the overall rate of the reaction was slow. A summary plot of all isoconversional methods for the conversion rates between 0.2-0.8 is shown in

Figure 7.

CRD wood may thus, be an ineffective direct fuel source because it needs a high energy to start reacting. Converting it into biochar will help ease conductivity and heat transfer issues resulting in faster reaction times.

3.6. Thermodynamic Parameters

For thermodynamic parameters, α < 0.2 and α > 0.8 are not considered because of low correlation factors encountered during the calculation of activation energies. As tabulated in

Table 7, for OFW, KAS, and FM methods, ΔH did not vary largely with heating rates. Likewise, a lower influence of increasing conversion rates on ΔH also meant that the difference in energy requirement between reactants and the intermediates is less, that can aid in faster formation of activated complexes. Concomittantly, positive values of ΔH indicated endothermic (exothermic if ΔH < 0) reaction steps with heat absorption for biomass conversion and is in agreement with the findings from Shagali et al., 2023. ΔH was 179-180 KJ/mol, 179-181 KJ/mol, and 190-192 KJ/mol for OFW, KAS, and FM methods. This is in line with the findings for another woody biomass (

Ficus Nitida) as discussed in Tabal et al., 2021. ΔG which describes the spontaneity of a reaction or a system indicated a minorly increasing trend with positive values for all heating rates, conversion rates, and methods. This means that the process was not spontaneous (only if ΔG < 0) and needed an external energy source to drive all parallel, sequential, and competing reactions. A ΔG of 215-230 KJ/mol was observed for both OFW and KAS methods between 0.2-0.8 conversion rates that represented consistent results. However, for FM method, ΔG ranged a bit higher from 250-275 KJ/mol. This is in agreement to the studies mentioned in Patil et al., 2023. A chemical reaction like pyrolysis usually supports greater disorderliness and randomness represented by the system’s entropy (ΔS > 0) where a solid biomass material breaks down into volatiles, gases, and oil which are relatively fluidic and harbor greater molecular freedom. On the contrary, the ΔS values for OFW (-60 to -80 J/mol.K), KAS (-60 to -85 J/mol.K), and FM (-110 to -130 J/mol.K) methods are largely negative (ΔS < 0) which meant that the pyrolytic product under consideration has lower molecular freedom and that more energy is needed to cause structural transformations in biomass as stated in Kumar et al., 2024. Low ΔS means that biomass has undergone gradual physical/chemical transformations, consistent with Singh et al., 2021. The negativity increases from α = 0.2-0.8. Biochar is a potential example of the pyrolysis product stream where the structural framework is somewhat stable and has a lower state of potential energy as described by Tabal et al., 2021.

4. Conclusions

TGA was used to evaluate the thermal stability and kinetic performance of CRD wood biomass. Model-free methods of OFW, KAS, and FM can be used to derive kinetic and thermodynamic parameters since they do not assume any pre-defined reaction models to calculate the activation energies, and function on the basis of conversion rates and temperatures. CR method can however, function only on the basis of such reaction models. These models also give a diverse perspective of the different transformation processes that biomass could have possible undergone each one ranked for plausibility w.r.t the correlation coefficient. Increasing heating rates shifted the decomposition peaks of biomass to relatively higher regions suggesting that rate of degradation depends significantly on BRT and pyrolysis temperature. Degradation of CRD biomass is usually a complex process to understand even with tailored operation parameters mainly due to its varying chemical composition too, as validated from its inherent biopolymer distribution, FTIR analysis, and morphology. Nevertheless, the experimental weight loss data from TGA at each phase of thermal breakdown was consistent with the kinetic analysis data. In the end, CRD biomass shows great potential to be a low-cost, high-value source for bioenergy and bioproducts production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, editing, visualization - Aravind Ganesan. Supervision, mentorship Simon Barnabé. Supervision, review, mentorship Simon Langlois. Supervision, review, editing, mentorship - Olivier Rezazgui. Supervision, review, editing, mentorship - Younès Bareha. Project administration Cyrine Boussabbeh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MITACS, through Escouade Energie, Citeq, and supported by Innofibre, and I2E3 UQTR, Québec, Canada. The work was conducted at Innofibre Centre d’Innovation des Produits Cellulosiques, Trois-Rivières and at the Institute for Innovation in Ecomaterials, Ecoproducts, and Ecoenergies (I2E3), University of Québec Trois-Rivières (UQTR), Québec, Canada.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

Due credits to the technicians, researchers, and colleagues who were a critical part of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| AAEM |

Alkaline and alkaline earth metals |

| BRT |

Biomass residence time |

| CCA |

Copper, chromium, and arsenic |

| CR |

Coats-Redfern |

| CRD |

Construction, renovation, and demolition |

| DB |

Dry basis |

| DTG |

Differential thermogram |

| FC |

Fixed carbon |

| FM |

Friedman |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared |

| GHGs |

Greenhouse gases |

| HHV |

Higher heating value |

| HTC |

Hydrothermal carbonization |

| KAS |

Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose |

| MP-AES |

Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer |

| Mt |

Million tons |

| OFW |

Ozawa-Flynn-Wall |

| PAH |

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric analysis |

| VC |

Volatile carbon |

| Wt% |

Weight percent (used interchangeably with %) |

References

- Adhikari, S. , Moon, E., Paz-Ferreiro, J., & Timms, W. Comparative analysis of biochar carbon stability methods and implications for carbon credits. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 914, 169607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altıkat, A. , Alma, M. H., Altıkat, A., Bilgili, M. E., & Altıkat, S. A Comprehensive Study of Biochar Yield and Quality Concerning Pyrolysis Conditions: A Multifaceted Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altynbaeva, D. , Astafev, A., & Tabakaev, R. (2018). Kinetics of biomass low-temperature pyrolysis by coats–redfern method. In MATEC Web of Conferences (Vol. 194, p. 01058). EDP Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Arenas, C. N. , Navarro, M. V., & Martínez, J. D. Pyrolysis kinetics of biomass wastes using isoconversional methods and the distributed activation energy model. Bioresource technology 2019, 288, 121485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armynah, B. , Tahir, D., Tandilayuk, M., Djafar, Z., & Piarah, W. H. Potentials of biochars derived from bamboo leaf biomass as energy sources: effect of temperature and time of heating. International Journal of Biomaterials 2019, 2019, 3526145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, C. , & Galgano, A. Kinetic Modelling of Biomass Pyrolysis Processes. Processes 2024, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisen, D. , Chouhan, A. P. S., Sarma, A. K., Rajamohan, S., Elumalai, P. V., Balasubramanian, D., & Cherie, A. Thermogravimetric analysis of rice husk and low-density polyethylene co-pyrolysis: kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 31798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călin, C. , Sîrbu, E. E., Tănase, M., Győrgy, R., Popovici, D. R., & Banu, I. A Thermogravimetric Analysis of Biomass Conversion to Biochar: Experimental and Kinetic Modeling. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. , Yu, Y., & Wu, H. Primary release and transformation of inorganic and organic sodium during fast pyrolysis of sodium-loaded lignin. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2023, 39, 3439–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, K. H. , Sadi, M., Chakravarty, H., Andersen, J., Choudhury, B., Howard, T. J., & Arabkoohsar, A. Pyrolysis kinetics and potential utilization analysis of cereal biomass by-products; an experimental analysis for cleaner energy productions in India. Chemosphere 2024, 353, 141420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channiwala, S. A. , & Parikh, P. P. A unified correlation for estimating HHV of solid, liquid and gaseous fuels. Fuel 2002, 81, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. , Hu, J., Han, Q., Xie, A., Zhou, Z., Yang, J.,... & Wu, F. Application of distributed activation energy model and Coats-Redfern integration method in the study of industrial lignin pyrolysis kinetics. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 2022; 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaundiyal, A. , Singh, S. B., Hanon, M. M., & Rawat, R. Determination of kinetic parameters for the thermal decomposition of parthenium hysterophorus. Environmental and Climate Technologies 2018, 22, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani, V. , & Bhaskar, T. A comprehensive review on the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Renewable energy 2018, 129, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufourny, A. , Van De Steene, L., Humbert, G., Guibal, D., Martin, L., & Blin, J. Influence of pyrolysis conditions and the nature of the wood on the quality of charcoal as a reducing agent. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2019, 137, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhenawy, Y. , Fouad, K., Mansi, A., Bassyouni, M., Gadalla, M., Ashour, F., & Majozi, T. Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of biomass pyrolysis. Experimental analysis and numerical simulation of biomass pyrolysis. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2024, 149, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiola-Sadiq, T. , Zhang, L., & Dalai, A. K. Thermal and kinetic studies on biomass degradation via thermogravimetric analysis: a combination of model-fitting and model-free approach. ACS omega 2021, 6, 22233–22247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanezouné, C. K. , Dhahak, A., Peixinho, J., & El Bari, H. Thermogravimetric analysis and kinetic modeling for empty fruit bunch date palm pyrolysis. Bioresource Technology Reports 2024, 27, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, O. , Lemaire, R., & Bensakhria, A. Thermogravimetric analysis and kinetic modeling of the pyrolysis of different biomass types by means of model-fitting, model-free and network modeling approaches. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2024; 149, 10941–10963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A. , Rezazgui, O., Burgos, J. B., Mangin, P. J., & Barnabé, S. Valorization of lignocellulosic biomass forest residues in quebec via the integrated hydropyrolysis and hydroconversion (IH2) technology: A review. Biomass and Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A. , Rezazgui, O., Langlois, S., Boussabbeh, C., & Barnabé, S. Pyrolytic conversion of construction, renovation, and demolition (CRD) wood wastes in Québec to biochar: Production, characterization, and identifying relevant stability indices for carbon sequestration. Science of The Total Environment 2025, 965, 178650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, A. , Desvita, H., Munawar, E., Mamat, R., Nizar, M., Darnas, Y., & Sarjono, R. E. Comparative analysis of HHV and LHV values of biocoke fuel from palm oil mill solid waste. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2024, 9, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, E. , Vitaali, G., Lanzini, A., & Santarelli, M. Integration between biomass gasification and high-temperature electrolysis for synthetic methane production. Biomass and Bioenergy 2021, 148, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmar, M. , Bouafif, H., Bouslimi, B., Braghiroli, F. L., & Koubaa, A. Pyrolysis of chromated copper arsenate-treated wood: investigation of temperature, granulometry, biochar yield, and metal pathways. Energies 2022, 15, 5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Aguilar, A. M. , Cabrera-Madera, V. P., Vera-Rozo, J. R., & Riesco-Ávila, J. M. Effects of heating rate and temperature on the thermal pyrolysis of expanded polystyrene post-industrial waste. Polymers 2022, 14, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grafmüller, J. , Böhm, A., Zhuang, Y., Spahr, S., Müller, P., Otto, T. N.,... & Hagemann, N. Wood ash as an additive in biomass pyrolysis: effects on biochar yield, properties, and agricultural performance. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2022, 10, 2720–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R. E. , Luna, A. S., & Torres, A. R. Operating parameters for bio-oil production in biomass pyrolysis: A review. Journal of analytical and applied pyrolysis 2018, 129, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, D. , Kresta, M., Hupfauf, B., Götz, P., Nussbaumer, R., Hofmann, A., & Pfeifer, C. Mechanical strength characterisation of pyrolysis biochar from woody biomass. Energy 2023, 285, 129366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadey, C. , Malika, A., Mohammed, A., & Fatima, B. (2020). A study on the biomass wastes' combustion process and their biochar.

- Han, H. , Buss, W., Zheng, Y., Song, P., Rafiq, M. K., Liu, P.,... & Li, X. Contaminants in biochar and suggested mitigation measures–a review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 429, 132287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. , Chakma, S., Liang, X., Sutradhar, S., Kozinski, J., & Kang, K. Engineered Biochar for Metal Recycling and Repurposed Applications. Energies 2024, 17, 4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. M. M. , Asif, M., Hussain, T., Sajjad, R., Yasmin, F., & Khandaker, M. U. Pyrolysis of municipal solid waste: Kinetics and thermodynamic parameters via Coats-Redfern method. Applied Chemical Engineering, 1872; 7, 1872–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, S. E. , Loha, C., Mahamood, R. M., Jen, T. C., Alam, M., Sarkar, I.,... & Akinlabi, E. T. An overview of biochar production techniques and application in iron and steel industries. Bioresources and bioprocessing 2024, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C. T. 18 Biochar analysis by Fourier-transform infra-red spectroscopy. Biochar: a guide to analytical methods 2017, 199.

- Kizha, A. R. , & Han, H. S. Processing and sorting forest residues: Cost, productivity and managerial impacts. Biomass and Bioenergy 2016, 93, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, I. , Tirlangi, S., Kathiresan, K., Sharma, V., Madhu, P., Sathish, T.,... & Murugan, P. Co-pyrolysis of furniture wood with mixed plastics and waste tyres: assessment of synergistic effect on biofuel yield and product characterization under different blend ratio. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 24584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. K. , Hallad, S. C., & Panwar, N. L. Thermogravimetric pyrolysis investigation of pistachio shell for its potential of thermal properties, kinetics and thermodynamics. Discover Energy 2024, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laadila, M. A. , LeBihan, Y., Caron, R. F., & Vaneeckhaute, C. Construction, renovation and demolition (CRD) wastes contaminated by gypsum residues: Characterization, treatment and valorization. Waste Management 2021, 120, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legan, M. , Gotvajn, A. Ž., & Zupan, K. Potential of biochar use in building materials. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 309, 114704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Shang, Y., Wei, W., Liu, Z., Qiao, Y., Qin, S., & Tian, Y. Comparative study on pyrolysis kinetics behavior and high-temperature fast pyrolysis product analysis of coastal zone and land biomasses. ACS omega 2022, 7, 10144–10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Sun, W., Lichtfouse, E., Maurer, C., & Liu, H. Life cycle assessment of biochar for sustainable agricultural application: A review. Science of The Total Environment, 2024; 951, 175448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N. , Huang, H., Feng, J., Li, R., Huang, X., & Wu, Y. Effects of alkali and alkaline earth metals in biomass on co-pyrolysis characteristics and product distribution of coal and biomass. Fuel 2025, 389, 134551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaoui, A. , Trabelsi, A. B. H., Abdallah, A. B., Chagtmi, R., Lopez, G., Cortazar, M., & Olazar, M. Assessment of pine wood biomass wastes valorization by pyrolysis with focus on fast pyrolysis biochar production. Journal of the Energy Institute 2023, 108, 101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H. , Shakeel, A., Abdullah, A., Khan, M. I., & Moniruzzaman, M. A comparative study on suitability of model-free and model-fitting kinetic methods to non-isothermal degradation of lignocellulosic materials. Polymers 2021, 13, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, I. , Li, X., Jian, Y., Dacres, O. D., Zhong, M., Liu, J.,... & Rahman, N. Kinetic study of biomass pellet pyrolysis by using distributed activation energy model and Coats Redfern methods and their comparison. Bioresource technology 2019, 294, 122099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R. K. , & Mohanty, K. Pyrolysis kinetics and thermal behavior of waste sawdust biomass using thermogravimetric analysis. Bioresource technology 2018, 251, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R. K. , Mohanty, K., & Wang, X. Pyrolysis kinetic behavior and Py-GC–MS analysis of waste dahlia flowers into renewable fuel and value-added chemicals. Fuel 2020, 260, 116338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlonka-Mędrala, A. , Magdziarz, A., Dziok, T., Sieradzka, M., & Nowak, W. Laboratory studies on the influence of biomass particle size on pyrolysis and combustion using TG GC/MS. Fuel 2019, 252, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monir, M. U. , Shovon, S. M., Akash, F. A., Habib, M. A., Techato, K., Abd Aziz, A.,... & Prasetya, T. A. E. Comprehensive characterization and kinetic analysis of coconut shell thermal degradation: Energy potential evaluated via the Coats-Redfern method. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2024, 55, 104186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouneir, S. M. , & El-Shamy, A. M. A review on harnessing the energy potential of pyrolysis gas from scrap tires: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable energy recovery. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2024, 177, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A. , Okolie, J. A., Tyagi, R., Dalai, A. K., & Niu, C. Pyrolysis kinetics and activation thermodynamic parameters of exhausted coffee residue and coffee husk using thermogravimetric analysis. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2021, 99, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, H. , Golrokh Sani, A., & Sobati, M. A. Thermogravimetric and thermo-kinetic analysis of sugarcane bagasse pith: a comparative evaluation with other sugarcane residues. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S. , Mohanty, P., Pant, K. K., Naik, S., Kozinski, J. A., & Dalai, A. K. Characterization of North American lignocellulosic biomass and biochars in terms of their candidacy for alternate renewable fuels. Bioenergy Research 2013, 6, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhuchhen, D. R. , & Afzal, M. T. HHV predicting correlations for torrefied biomass using proximate and ultimate analyses. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzediegwu, C. , Naeth, M. A., & Chang, S. X. Elemental composition of biochars is affected by methods used for its determination. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2021, 156, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Dwyer, J. , Walshe, D., & Byrne, K. A. Wood waste decomposition in landfills: An assessment of current knowledge and implications for emissions reporting. Waste Management 2018, 73, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, R. , Castells, B., & Tascón, A. Thermogravimetric Assessment of Biomass: Unravelling Kinetic, Chemical Composition and Combustion Profiles. Fire 2024, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, K. , Singathia, A., Vashishtha, M., Sangal, V. K., & Upadhyaya, S. Investigation of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters approaches to non-isothermal pyrolysis of mustard stalk using model-free and master plots methods. Materials Science for Energy Technologies 2022, 5, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, Y. , Ku, X., & Vasudev, V. Pyrolysis characteristics and determination of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of raw and torrefied Chinese fir. ACS omega 2023, 8, 34938–34947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecha, M. B. , Arbelaez, J. I. M., Garcia-Perez, M., Chejne, F., & Ciesielski, P. N. Progress in understanding the four dominant intra-particle phenomena of lignocellulose pyrolysis: chemical reactions, heat transfer, mass transfer, and phase change. Green chemistry 2019, 21, 2868–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J. F. , Iribarren, D., & Dufour, J. Biomass pyrolysis for biochar or energy applications? A life cycle assessment. Environmental science & technology 2015, 49, 5195–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfersich, J. , Arauzo, P. J., Modugno, P., Titirici, M. M., & Kruse, A. Evaluation of the Char Formation During the Hydrothermal Treatment of Wooden Balls. Global Challenges 2023, 7, 2300169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postawa, K. , Fałtynowicz, H., Szczygieł, J., Beran, E., & Kułażyński, M. Analyzing the kinetics of waste plant biomass pyrolysis via thermogravimetry modeling and semi-statistical methods. Bioresource Technology 2022, 344, 126181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punsuwan, N. , & Tangsathitkulchai, C. Product Characterization and Kinetics of Biomass Pyrolysis in a Three-Zone Free-Fall Reactor. International Journal of Chemical Engineering 2014, 2014, 986719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojević, M. , Janković, B., Jovanović, V., Stojiljković, D., & Manić, N. Comparative pyrolysis kinetics of various biomasses based on model-free and DAEM approaches improved with numerical optimization procedure. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0206657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambhatla, N. , Panicker, T. F., Mishra, R. K., Manjeshwar, S. K., & Sharma, A. Biomass pyrolysis for biochar production: Study of kinetics parameters and effect of temperature on biochar yield and its physicochemical properties. Results in Engineering 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzi, E. , Debiagi, P. E. A., & Frassoldati, A. Mathematical modeling of fast biomass pyrolysis and bio-oil formation. Note I: kinetic mechanism of biomass pyrolysis. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2017, 5, 2867–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y. K. , Dhanalakshmi, C. S., Vairavel, D. K., Surakasi, R., Kaliappan, S., Patil, P. P.,... & Lalvani, J. I. J. Investigation on forestry wood wastes: pyrolysis and thermal characteristics of Ficus religiosa for energy recovery system. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 2022, 3314606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M. , Abu-Jdayil, B., & Inayat, A. Pyrolytic kinetics and thermodynamic analyses of date seeds at different heating rates using the Coats–Redfern method. Fuel 2023, 342, 127799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. , & Bahadar, A. In-Depth Study on Synergic Interactions and Thermo-Kinetic Analysis of (Wheat Straw and Woody Sawdust) Biomass Co-Pyrolysis over Mussel Shell-Derived CaO Catalyst Using Coats–Redfern Method. Catalysts 2024, 14, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagali, A. A. , Hu, S., Li, H., Chi, H., Qing, H., Xu, J.,... & Xiang, J. Thermal behavior, synergistic effect and thermodynamic parameter evaluations of biomass/plastics co–pyrolysis in a concentrating photothermal TGA. Fuel 2023, 331, 125724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, D. K. , Singh, A. K., & Chakraborty, J. P. Model-free isoconversional methods to determine the intrinsic kinetics and thermodynamic parameters during pyrolysis of boiled banana peel: influence of inorganic species. Bioresource Technology Reports 2023, 24, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. , Teixeira, S., & Teixeira, J. A review of biomass thermal analysis, kinetics and product distribution for combustion modeling: From the micro to macro perspective. Energies 2023, 16, 6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. K. , Patil, T., Pandey, D., & Sawarkar, A. N. Pyrolysis of mustard oil residue: a kinetic and thermodynamic study. Bioresource Technology 2021, 339, 125631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, S. , & Werle, S. Kinetic modelling of waste wood devolatilization during pyrolysis based on thermogravimetric data and solar pyrolysis reactor performance. Fuel 2020, 261, 116459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szufa, S. , Piersa, P., Adrian, Ł., Czerwińska, J., Lewandowski, A., Lewandowska, W.,... & Knapczyk, A. Sustainable drying and torrefaction processes of miscanthus for use as a pelletized solid biofuel and biocarbon-carrier for fertilizers. Molecules 2021, 26, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabal, A. , Barakat, A., & Aboulkas, A. Pyrolysis of ficus nitida wood: determination of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. Fuel 2021, 283, 119253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, R. , Saeed, S., Riaz, M., & Saeed, S. Kinetic and thermodynamic evaluation of almond shells pyrolytic behavior using Coats–Redfern and pyrolysis product distribution model. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 2023, 45, 4446–4462. [Google Scholar]