Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Temperature Tolerance and Mortality

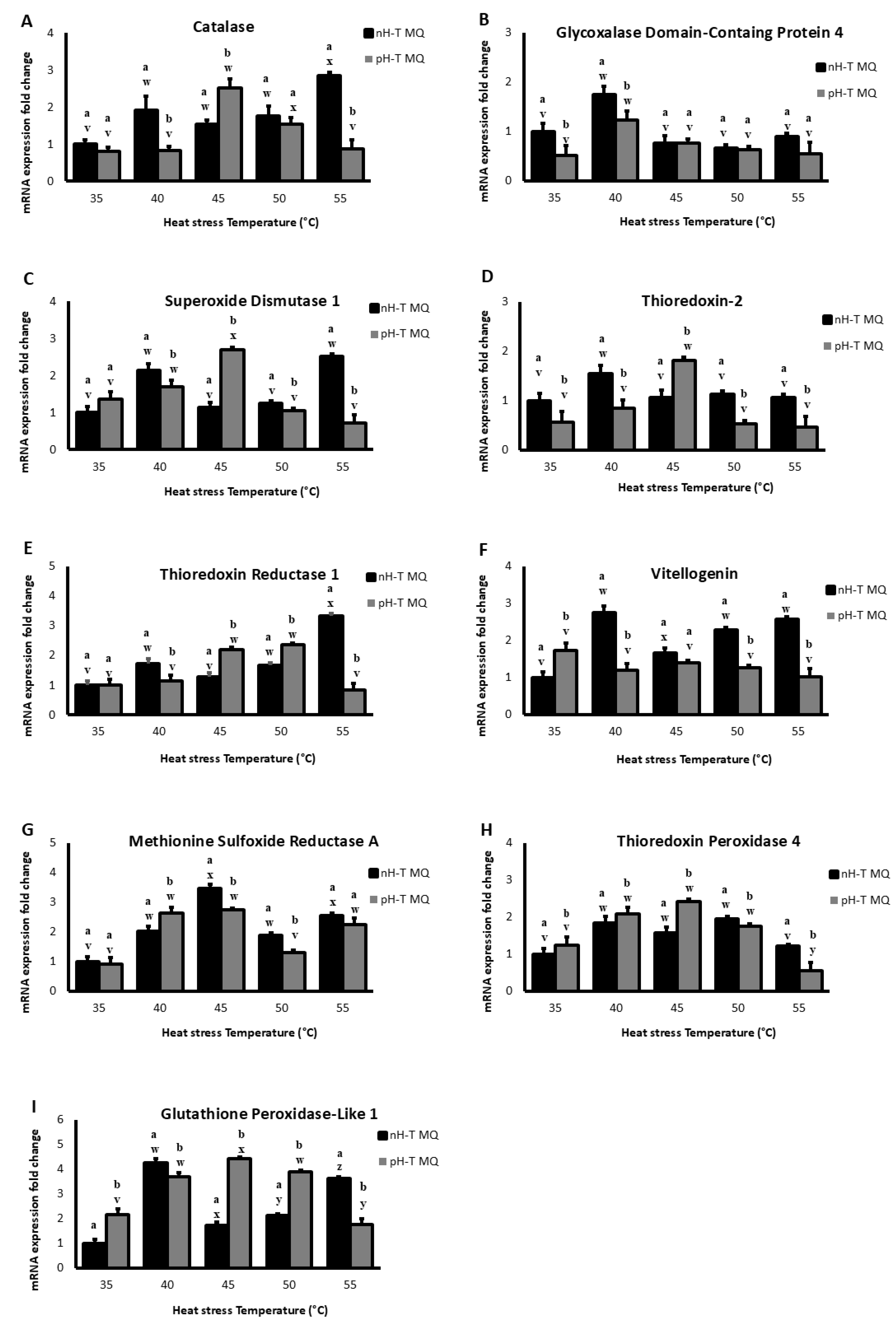

2.2.1. Catalase

2.2.2. Glycoxylase Domain-Containing Protein 4 (GLOD 4)

2.2.3. Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD 1)

2.2.4. Thioredoxin-2 (TrX 2)

2.2.5. Thioredoxin Reductase-1 (TrxR 1)

2.2.6. Vitellogenin (Vg)

2.2.7. Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase (MsrA)

2.2.8. Thioredoxin Peroxidase 4 (Tpx 4)

2.2.9. Glutathione Peroxidase Like 1 (Gtpx 1)

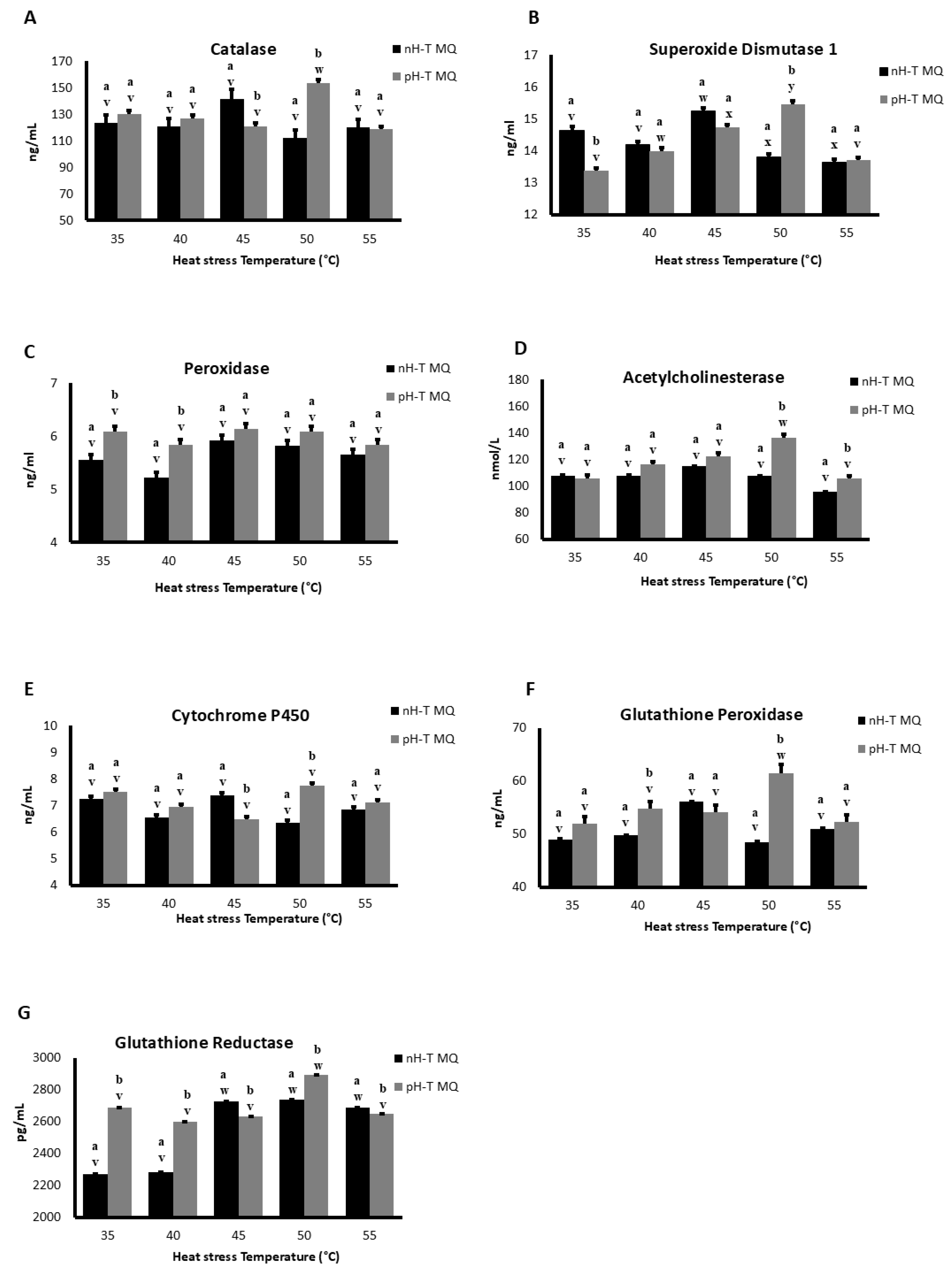

2.3. Antioxidants Concentration

2.3.1. Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD 1)

2.3.2. Peroxidase (POD)

2.3.3. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE)

2.3.4. Cytochrome P450 (CYTP450)

2.3.5. Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX)

2.3.6. Glutathione Reductase (GSR)

2.3.7. Catalase (Cat)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Queen Rearing

4.2. Pre-Heat Treatment-Queen Larval Stage

4.3. Rapid Heat Treatment and Heat Stress

4.4. RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

4.5. Relative Quantitative Real-Time qPCR (RT-qPCR)

4.6. ELISA

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| nH-T MQ | non-heat-treated mother queens |

| pH-T MQ | pre-heat-treated mother queen group |

| RHH | Rapid heat hardening |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Modell, H.; Cliff, W.; Michael, J.; McFarland, J.; Wenderoth, M.P.; Wright, A. A Physiologist's View of Homeostasis. Adv Physiol Educ 2015, 39, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsky, J.; Joshi, N.K. Impact of Biotic and Abiotic Stressors on Managed and Feral Bees. Insects 2019, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genersch, E. Honey Bee Pathology: Current Threats to Honey Bees and Beekeeping. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 87, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnieks, F.L.; Carreck, N.L. Ecology. Clarity on Honey Bee Collapse? Science 2010, 327, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Hung, Y.S.; Yang, E.C. Biogenic Amine Levels Change in the Brains of Stressed Honeybees. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2008, 68, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurnberger, F.; Hartel, S.; Steffan-Dewenter, I. The Influence of Temperature and Photoperiod on the Timing of Brood Onset in Hibernating Honey Bee Colonies. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchiccela B, Castelli, L. ; Corona, M.; Diaz-Cetti, S.; Invernizzi, C.; Martinez de la Escalera, G.; Mendoza, Y.; Santos, E.; Silva, C.; Zunino, P.; Antunez, K. Impact of Nutritional Stress on the Honeybee Colony Health. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Jones, W.A. Expression of Heat Shock Protein Genes in Insect Stress Responses. Invertebrate Surviv J 2012, 9, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Felton, G.W.; Summers, C.B. Antioxidant Systems in Insects. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 1995, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Byarlay, H.; Huang, M.H.; Simone-Finstrom, M.; Strand, M.K.; Tarpy, D.R.; Rueppell, O. Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Drones Survive Oxidative Stress Due to Increased Tolerance Instead of Avoidance or Repair of Oxidative Damage. Exp Gerontol 2016, 83, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, M.; Robinson, G.E. Genes of the Antioxidant System of the Honey Bee: Annotation and Phylogeny. Insect Mol Biol 2006, 15, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmochowska-Ślęzak, K.; Giejdasz, K.; Fliszkiewicz, M.; Żółtowska, K. Variations in Antioxidant Defense During the Development of the Solitary Bee Osmia bicornis. Apidologie 2015, 46, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zou, L.; Zhang, X.; Branco, V.; Wang, J.; Carvalho, C.; Holmgren, A.; Lu, J. Redox Signaling Mediated by Thioredoxin and Glutathione Systems in the Central Nervous System. Antioxid Redox Signal 2017, 27, 989–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.A.; Koc, A.; Cerny, R.L.; Gladyshev, V.N. Reaction Mechanism, Evolutionary Analysis, and Role of Zinc in Drosophila Methionine-R-Sulfoxide Reductase. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 37527–37535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.E.; Souza, A.O.; Tiberio, G.J.; Alberici, L.C.; Hartfelder, K. Differential Expression of Antioxidant System Genes in Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) Caste Development Mitigates Ros-Mediated Oxidative Damage in Queen Larvae. Genet Mol Biol 2020, 43, e20200173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzugan, M.; Tomczyk, M.; Sowa, P.; Grabek-Lejko, D. Antioxidant Activity as Biomarker of Honey Variety. Molecules 2018, 23, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurori, C.M.; Buttstedt, A.; Dezmirean, D.S.; Marghitas, L.A.; Moritz, R.F.; Erler, S. What Is the Main Driver of Ageing in Long-Lived Winter Honeybees: Antioxidant Enzymes, Innate Immunity, or Vitellogenin? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014, 69, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleolog, J.; Wilde, J.; Miszczak, A.; Gancarz, M.; Strachecka, A. Antioxidation Defenses of Apis Mellifera Queens and Workers Respond to Imidacloprid in Different Age-Dependent Ways: Old Queens Are Resistant, Foragers Are Not. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabentheiner, A.; Kovac, H.; Brodschneider, R. Honeybee Colony Thermoregulation--Regulatory Mechanisms and Contribution of Individuals in Dependence on Age, Location and Thermal Stress. PLoS One 2010, 5, e8967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, W.; Shen, J.; Long, D.; Feng, Y.; Su, W.; Xu, K.; Du, Y.; Jiang, Y. Tolerance and Response of Two Honeybee Species Apis cerana and Apis mellifera to High Temperature and Relative Humidity. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomatto, L.C.D.; Davies, K.J.A. Adaptive Homeostasis and the Free Radical Theory of Ageing. Free Radic Biol Med 2018, 124, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.J. Positive Oxidative Stress in Aging and Aging-Related Disease Tolerance. Redox Biol 2014, 2, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, R.G.; Paxton, R.J. De Luna, E.; Fleites-Ayil F.A.; Medina L.A.M.; Quezada-Euán J.J.G. Developmental Stability, Age at Onset of Foraging and Longevity of Africanized Honey Bees (Apis mellifera L.) under Heat Stress (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Thermal Biol 2018, 74, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groh, C.; Tautz, J.; Rössler, W. Synaptic Organization in the Adult Honey Bee Brain Is Influenced by Brood-Temperature Control During Pupal Development. PNAS 2004, 101, 4268–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tautz, J.; Maier, S.; Groh, C.; Rössler, W.; Brockmann, A. Behavioral Performance in Adult Honey Bees Is Influenced by the Temperature Experienced During Their Pupal Development. PNAS 2003, 100, 7343–7347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, M.A.; Scharpenberg, H.; Moritz, R.F. Pupal Developmental Temperature and Behavioral Specialization of Honeybee Workers (Apis mellifera L.). J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol 2009, 195, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, M.; Zeltzer, A.; Degrandi-Hoffman, G.; Martin, J.H. Influence of Temperature on Rate of Development and Color Patterns of Queen Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Environ Entomol 1992, 21, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ken, T.; Bock, F.; Fuchs, S.; Streit, S.; Brockmann, A.; Tautz, J. Effects of Brood Temperature on Honey Bee Apis mellifera Wing Morphology. Acta Zool Sin 2005, 51, 768–771. [Google Scholar]

- Elekonich, M.M. Extreme Thermotolerance and Behavioral Induction of 70-Kda Heat Shock Proteins and Their Encoding Genes in Honey Bees. Cell Stress Chaperon 2009, 14, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.; Cleare, X.; Li-Byarlay, H. The Life Span and Levels of Oxidative Stress in Foragers between Feral and Managed Honey Bee Colonies. J Insect Sci 2022, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, S.; Bandani, A.R.; Alizadeh, H.; Goldansaz, S.H.; Whyard, S. Differential Expression of Heat Shock Proteins and Antioxidant Enzymes in Response to Temperature, Starvation, and Parasitism in the Carob Moth Larvae, Ectomyelois ceratoniae (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wos, G.; Willi, Y. Thermal Acclimation in Arabidopsis Lyrata: Genotypic Costs and Transcriptional Changes. J Evol Biol 2018, 31, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Even, N.; Devaud, J.M.; Barron, A.B. General Stress Responses in the Honey Bee. Insects 2012, 3, 1271–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willot, Q.; Gueydan, C.; Aron, S. Proteome Stability, Heat Hardening and Heat-Shock Protein Expression Profiles in Cataglyphis Desert Ants. J Exp Biol 2017, 220(Pt 9), 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchel, A.; Komisarczuk, A.Z.; Rebl, A.; Goldammer, T.; Nilsen, F. Systematic Identification and Characterization of Stress-Inducible Heat Shock Proteins (Hsps) in the Salmon Louse (Lepeophtheirus Salmonis). Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendal, A.; Overgaard, J.; Bundy, J.G.; Sorensen, J.G.; Nielsen, N.C.; Loeschcke, V.; Holmstrup, M. Metabolomic Profiling of Heat Stress: Hardening and Recovery of Homeostasis in Drosophila. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2006, 291, R205–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, A.; Inayat, R.; Tamkeen, A.; Ul Haq, I.; Li, C.; Boamah, S.; Zhou, J.J.; Liu, C. Antioxidant Enzymes and Heat-Shock Protein Genes of Green Peach Aphid (Myzus persicae) under Short-Time Heat Stress. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 805509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.Q.; Tu, Y.Q.; Guo, P.Y.; He, W.; Jing, T.X.; Wang, J.J.; Wei, D.D. Antioxidant Enzymes and Heat Shock Protein Genes from Liposcelis Bostrychophila Are Involved in Stress Defense Upon Heat Shock. Insects 2020, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, R.T.; Wei, H.P.; Wang, F.; Zhou, X.H.; Li, B. Anaerobic Respiration and Antioxidant Responses of Corythucha ciliata (Say) Adults to Heat-Induced Oxidative Stress under Laboratory and Field Conditions. Cell Stress Chaperones 2014, 19, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Tian, S.; Wang, D.; Gao, F.; Wei, H. Interaction between Short-Term Heat Pretreatment and Fipronil on 2 Instar Larvae of Diamondback Moth, Plutella xylostella (Linn). Dose Response 2010, 8, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghzawi A.A.A.;, Al-Zghoul M.B.; Zaitoun S.; Al-Omary I.M.; Alahmad N.A. Dynamics of Heat Shock Proteins and Heat Shock Factor Expression During Heat Stress in Daughter Workers in Pre-Heat-Treated (Rapid Heat Hardening) Apis mellifera Mother Queens. J Therm Biol 2022, 104, 103194. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, J.A.; Heinen, R.; Gols, R.; Thakur, M.P. Climate Change-Mediated Temperature Extremes and Insects: From Outbreaks to Breakdowns. Glob Chang Biol 2020, 26, 6685–6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchuk, I.I.; Volkov, R.A.; Schoffl, F. Heat Stress- and Heat Shock Transcription Factor-Dependent Expression and Activity of Ascorbate Peroxidase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2002, 129, 838–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaquet, V.; Wallerich, S.; Voegeli, S.; Turos, D.; Viloria, E.C.; Becskei, A. Determinants of the Temperature Adaptation of Mrna Degradation. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, 1092–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.N.; Lee, S.G.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.K.; Choi, Y.; S; Kim, G.H. Comparative Analyses of Cu-Zn Superoxide Dismutase (Sod1) and Thioredoxin Reductase (Trxr) at the Mrna Level between Apis mellifera L. And Apis cerana F. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) under Stress Conditions. J Insect Sci 2016, 16, 4. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Abreu, R.; Penalva, L.O.; Marcotte, E.M.; Vogel, C. Global Signatures of Protein and Mrna Expression Levels. Mol Biosyst 2009, 5, 1512–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, N.; Wood, J.; Barber, J. The Role of Glutathione Reductase and Related Enzymes on Cellular Redox Homoeostasis Network. Free Radic Biol Med 2016, 95, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghzawi, A.A.A.; Zaitoun, S. Origin and Rearing Season of Honeybee Queens Affect Some of Their Physiological and Reproductive Characteristics. Entomol Res 2008, 38, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, H.; Page, R. Queen Rearing and Bee Breeding. 1st edn. 1997, Vol. MI, p. 224. Wicwas Press, Kalamazoo.

- Pettis, J.S.; Rice, N.; Joselow, K.; vanEngelsdorp, D.; Chaimanee, V. Colony Failure Linked to Low Sperm Viability in Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Queens and an Exploration of Potential Causative Factors. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0147220. [Google Scholar]

- McAfee, A.; Pettis, J.S.; Tarpy, D.R.; Foster, L.J. Feminizer and Doublesex Knock-Outs Cause Honey Bees to Switch Sexes. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Forward (5’-3’) | Product size | Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|

| atalase (Cat) | F: ACGAAATCCTTCCGCTGACC R: AGCATGGACTACACGTTCCG |

106 | AF436842.1 |

| Glycosylase Domain-Containing Protein 4 (GLOD 4) | F: GGAATTTGCTGAAGGTTGCG R: TGAGTATCTTCTGTTCCATATCCTATC |

94 | XM_625097.3 |

| Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD 1) | F: CGTTCCGTGTAGTCGAGAAAT R: GGTACTCTCCGGTTGTTCAAA |

133 | NM_001178027.1 |

| Thioredoxin 2 (TrX 2) | F: GGTTTACCAAATTAAGAATGCCAGT R: GACCACACCACATAGCAAAGA |

98 | XM_003250360 |

| Thioredoxin Reductase 1 (TrxR 1) | F: CTGATTGCTGTAGGTGGTAGAC R: CCAGCACATTCTAAACCAATATATCC |

149 | NM_001178025 |

| Vitellogenin (Vg) | F: GAACCTGGAACGAACAAGAATG R: CGACGATTGGATGGTGAAATG |

98 | NM_001011578.1 |

| Methionine Sulfoxide Reductase (MsrA) | F: GGGCCGGTGATTGTTTATTTG R: CAACGACTTCTGTATGATCACCT |

113 | AY329360.1 |

| Thioredoxin Peroxidase 4 (Tpx 4) | F: ACCTGGAGCATTTCCTTATCC R: CGCTTGTTCTGGATCATCTTTG |

103 | NM_001170973.1 |

| Glutathione Peroxidase-like 1 (Gtpx 1) | F: ATGGTCAAGAACCGGGAAATAG R: GGATGCGCAGAATCTCCATTA |

109 | NM_001178022.1 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2 (GAPDH) | F: TGGCAAAGGTGCAGACTATAAA R: TGGCATGGTCATCACCAATAA |

131 | XM_393605.7 |

| β-Actin related protein 1 (β-Actin) | F: CTAGCACCATCCACCATGAAA R: AGGTGGACAAAGAAGCAAGAA |

97 | NM_001185146.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).