1. Introduction

Fixed-point continuous monitoring systems (CMS) have been deployed in oil and natural gas production facilities over the past few years, primarily to provide a continuous stream of data related to site-level methane emission, allowing for the detection of anomalous emission events, source localization, and emission rate quantification. CMS can also complement other forms of methane monitoring by providing data-driven site-level insights regarding emissions event duration and frequency [

1], and also provide complementary meteorological data to other measurement modalities that do not have in-situ sensors (e.g., aerial flyovers or satellite overpasses).

Various ambient methane measurement technologies exist for fixed-point continuous methane monitoring systems, spanning a wide range of detection modalities. Each of these sensing options have their own unique strengths and limitations. These technologies offer adaptability to various environmental conditions and application requirements. For instance, metal oxide (MOx) sensors provide cost-effective, broad-range concentration measurements. However, their technological limitations often restrict the utilization of these sensors to anomaly detection [

1,

2]. In contrast, tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy (TDLAS) sensors offer high precision and selectivity in return for a higher sensor price point. The selection of the measurement technology depends on factors such as project objectives, sensitivity requirements, operational environment, and cost considerations [

3,

4]. Examples of other ground-based continuous methane measurement methods include fixed optical gas imaging camera systems with quantitative capabilities as well as path-integrated methane measurement technologies that measure concentrations across short-range distances (e.g., <200 m) or over kilometer-scale areas. The accuracy of emission rate quantifications using these systems may vary significantly depending on the technology and solution provider [

5,

6,

7].

Properly-deployed CMS can provide timely alerts of potential site-level methane release events that could lead to elevated concentrations using a wide range of algorithms, from static ambient concentration thresholds to sophisticated machine learning techniques [

8]. For the first few years of the at-scale deployment of CMS, anomalous event detection was considered the primary application of these systems. However, with advances in emissions dispersion modeling and associated rate inversion, CMS has demonstrated potential beyond emission event detection. Enhanced emission modeling can result in reliable source localization and emission quantification, which can significantly augment the actionable insights derived from these systems [

9].

Fixed-point sensors provide ambient methane concentration measurements, often in parts-per-million (ppm), at a known location at a relatively high temporal frequency (typically at least one measurement is reported every minute). The raw data from CMS often consists of a set of methane concentration measurements in several sensor locations, plus meteorological measurement data collected using on-site anemometers. To infer the flux rate at the source location(s) (mass of pollutant emitted per unit of time), quantification algorithms need to translate the CMS raw data into the mass of pollutant emitted per unit of time. This is often achieved by combining the application of forward dispersion models and inversion frameworks [

10].

Forward dispersion models and inversion frameworks are often employed for the estimation of source emissions rate based on ambient concentration measurements. Forward dispersion models simulate the atmospheric transport of pollutants from any given source to receptors (e.g. sensor locations), factoring in meteorological parameters such as wind speed, wind direction, and atmospheric stability. In other words, a forward dispersion model simulates concentration enhancements at a given location, resulting from a known release rate from a given source location [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Subsequently, inversion models use mathematical optimization to determine source flux rates that produce simulated concentrations that align as closely as possible to the actual measurements. Inversion frameworks try to leverage simulated concentrations at the sensor locations and knowledge of forward dispersion patterns to solve an optimization problem, where the objective is to find a combination of source emission rates generating simulated concentrations that best fit the observed concentrations [

8]. A detailed discussion on the performance of various forward dispersion models and inversion frameworks can be found in [

22].

Controlled release studies are invaluable in helping to improve the capabilities of CMS technologies and evaluate their performance. These studies provide large volumes of high-quality “ground truth” data that enable technology developers to drive innovation and improve their algorithms. Recent studies suggest that the performance of CMS solutions has improved through continuous, rigorous testing using a standardized protocol [

7]. Cheptonui et al. [

7] indicated a positive correlation between repeated testing (frequent participation in controlled release testing studies) and improvement in the overall performance of solutions. The bulk of these improvements are realized via improved algorithmic workflows, from data pre-processing and cleaning, to more accurate dispersion modeling, and finally implementing more sophisticated inverse solvers; the hardware being tested tends to stay the same year-over-year.

More specifically, single-blind controlled release studies use several pre-defined metrics to assess the performance of CMS solutions. These evaluations encapsulate both the emissions measurement (hardware) and analytics (algorithms) related to emissions detection, localization, and quantification (DLQ). In single-blind studies, known quantities of natural gas are emitted from one or several release points within the study site. Each participating technology submits a summary of its DLQ results without prior knowledge of emissions rates, release points, or the timing of emission events. Submitted results are then compared against ground-truth data to assess how well each technology performed during the study [

23]. Note that controlled release studies are often designed to determine the combined uncertainty resulting from measurement (hardware) and data analysis (algorithms). In other words, to the best of our knowledge, there is no testing campaign that has been undertaken to disentangle these two sources of uncertainty by, for example, providing the participants with the same measurement data and focusing solely on the performance of different algorithms applied to the same underlying data.

In terms of facility complexity, the layout of controlled release sites can be simple (where only one or a few release points are included in the experiments and no obstacles or complex terrain is present), moderate (such as controlled testing facilities specifically designed to simulated operational emissions), or complex (such as actual operational oil and gas facilities). Other factors, such as complex terrain or the presence of obstacles, may contribute to the complexity of the testing facility. In addition, controlled releases can also vary in terms of the complexity associated with emission scenarios. First, a controlled release experiment may include a single emissions event or multiple overlapping events (i.e., multiple active release points). Second, when the emission scenario includes multiple overlapping events, those events can start and end together or asynchronously. Third, emission events may consist of steady-state or time-varying emission rates. Fourth, emission events may be designed to occur in the absence of simulated baseline emission, or alternatively, a simulated baseline emission level (steady-state or fluctuating baseline) may be present. Fifth, to add to this complexity, fluctuations in the baseline emissions may be designed to be comparable to the emission event rates. Sixth, emission scenarios may be designed with various durations and magnitudes, ranging from short-duration, small events to long-lasting events with high emission rates. Seventh, release points may be underground (to simulate pipelines), on the surface, or significantly elevated (for instance, representative of tanks or flare stacks). Eighth, offsite emission sources can be included in the design of emission scenarios. Lastly, in the case of non-oil and gas controlled releases, area sources may be considered in designing emission scenarios (e.g., to simulate landfill or underground pipeline emissions).

Examples of methane controlled release studies for CMS solutions include testing under the Advancing the Development of Emission Detection (ADED) program [

23], funded by the US Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), administered by the Colorado State University’s Methane Emissions Technology Evaluation Center (METEC) in its Fort Collins facility [

6,

7,

24] and during field campaigns [

25,

26,

27], studies performed at the TotalEnergies Anomaly Detection Initiative (TADI) testing facility [

28,

29,

30], Stanford University’s controlled release study in an experimental field site in Arizona [

5], Highwood Emissions Management testing in Alberta [

31], Alberta Innovates technology-specific controlled release testing studies [

32]. Note that some of these studies include simple release scenarios with only one release point [

31], while others may range from moderate complexity, with multiple release points with simplified release scenarios (e.g., steady-state, synchronous events during each experiment)[

6,

7,

24], or complex release scenarios conducted in actual operational setups [

25,

27].

Controlled release testing studies conducted by METEC from 2022 to 2024 [

6,

7,

24] are known as the most comprehensive single-blind CMS controlled release studies. The first iteration of the ADED protocol [

23] was employed during these studies. This protocol is comprised of temporally-distinct "experiments" at the METEC facility, each of which has between 1 and 5 synchronous release events (turned on and off at the start and end of each unique experiment). During the most recent (2024) campaign, experiment durations ranged between 15 minutes and 8 hours. Emission rates for each source during an individual experiment were held constant, with individual source rates ranging from 0.081 to 6.75 kg/hr. In that study, the experiments were designed such that only one release was active per equipment group at the METEC facility. Emission scenarios were designed in the absence of an artificial baseline emission or off-site sources. The results of the 2024 ADED study are publicly available on the METEC website [

33].

While research efforts have primarily concentrated on evaluating the accuracy of fixed-point CMS-based quantification for steady-state emission releases, studies have recently started to focus on the more complex scenario of dynamic and asynchronous emissions, which are common in operational facilities. Simpler event-based emission patterns used in previous studies characterized by distinct "experiments" with multiple synchronized release points do not appropriately mimic the complex emissions expected at operational facilities, and therefor do not fully evaluate the efficacy of the solutions being tested in terms of their performance in the field. As such, there is a clear need for advanced testing protocols that are capable of more closely simulating real-world emissions patterns and evaluating the performance of technologies under these more complex situations.

CSU’s METEC has recently upgraded its facility in Fort Collins and published a revised ADED testing protocol aiming to better align controlled release testing with emission profiles of real-world operating oil and gas facilities [

34]. This upgraded METEC 2.0 facility will enhance testing capabilities by adding new equipment, expanding release point options, and improving underground controlled release testing capabilities. In addition to these physical upgrades, the future ADED testing will include more complex emission scenarios, including fluctuating baseline emissions, asynchronous releases, and time-varying release rates.

This study evaluates the performance of emissions quantification using fixed-point continuous monitoring systems under complex single-blind testing conditions that more closely mimic real-world operational emission scenarios. More specifically, by comparing the actual release rates to the estimated rates, this study investigates the impact of averaging time on the uncertainties associated with emissions quantification. We take a deep dive into the application of short-term and long-term emission rate averaging approaches and study the root causes of emission source misattribution in a few select scenarios. Lastly, the application of anomalous emissions alerting above baseline is investigated. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind concerning the performance evaluation of a fixed-point continuous monitoring system under single-blind testing conditions involving complex, multi-source emission scenarios, including fluctuating baseline emissions, asynchronous releases, and time-varying release rates. Although the data is collected using a specific fixed-point CMS solution (employing TDLAS sensors) and a solution-specific quantification method is employed to derive emission rates, we still expect that most of the insights discussed in this study hold for many analogous technologies.

2. Data and Method

In August and September of 2024, METEC conducted a 28-day trial study intended to more accurately mimic emissions at operational oil and gas facilities via the inclusion of a noisy and time-varying baseline layered with multi-source asynchronous releases of various sizes. Project Canary participated in this single-blind controlled release study. It should be noted that the description here represents the authors’ best understanding of the controlled release study experiments and does not come directly from METEC.

The revised ADED testing protocol aims to replicate the emission characteristics of operational facilities, incorporating a stochastic, time-dependent baseline with significant high-frequency spectral power originating from diverse spatial locations. This baseline is intended to simulate operational emissions, such as those from pneumatic devices and compressor slip. Following a one-week baseline emission period, controlled releases of varying magnitudes and durations were introduced. These release events may exhibit partial or complete temporal overlap. At any given time, the total rate can be computed as the sum over all individual releases. This quantity will be often referred to as the "site-level" or "source-integrated" rate, and represents the total emission rate from the facility.

This study utilizes data collected using the Canary X integrated device, which combines a TDLAS methane sensor with an optional RM Young 2-dimensional ultrasonic anemometer. The Canary X, an IoT-enabled monitor, leverages high-sensitivity methane concentration measurements and meteorological measurements for methane emissions quantification. The methane sensor features a 0.4 ppm sensitivity, ±2% accuracy, and ≤0.125 ppm precision (60-second averaging).

A comprehensive analysis comparing various quantification methodologies, including different combinations of forward dispersion models and inverse frameworks, was discussed in a prior publication [

22]. The focus of this study lies in evaluating the system’s performance under complex, real-world emission scenarios and assessing the impact of averaging time on emission rate estimation. Therefore, the core insights derived in this work, particularly regarding the trade-offs between temporal resolution and error reduction, will generally apply to fixed-point CMS, regardless of the specific algorithm used. By concentrating on the examination of the system’s overall performance and operational implications, this study aims to improve the understanding of methane measurement and quantification using fixed-point CMS, building upon our prior work on quantification methodologies [

22].

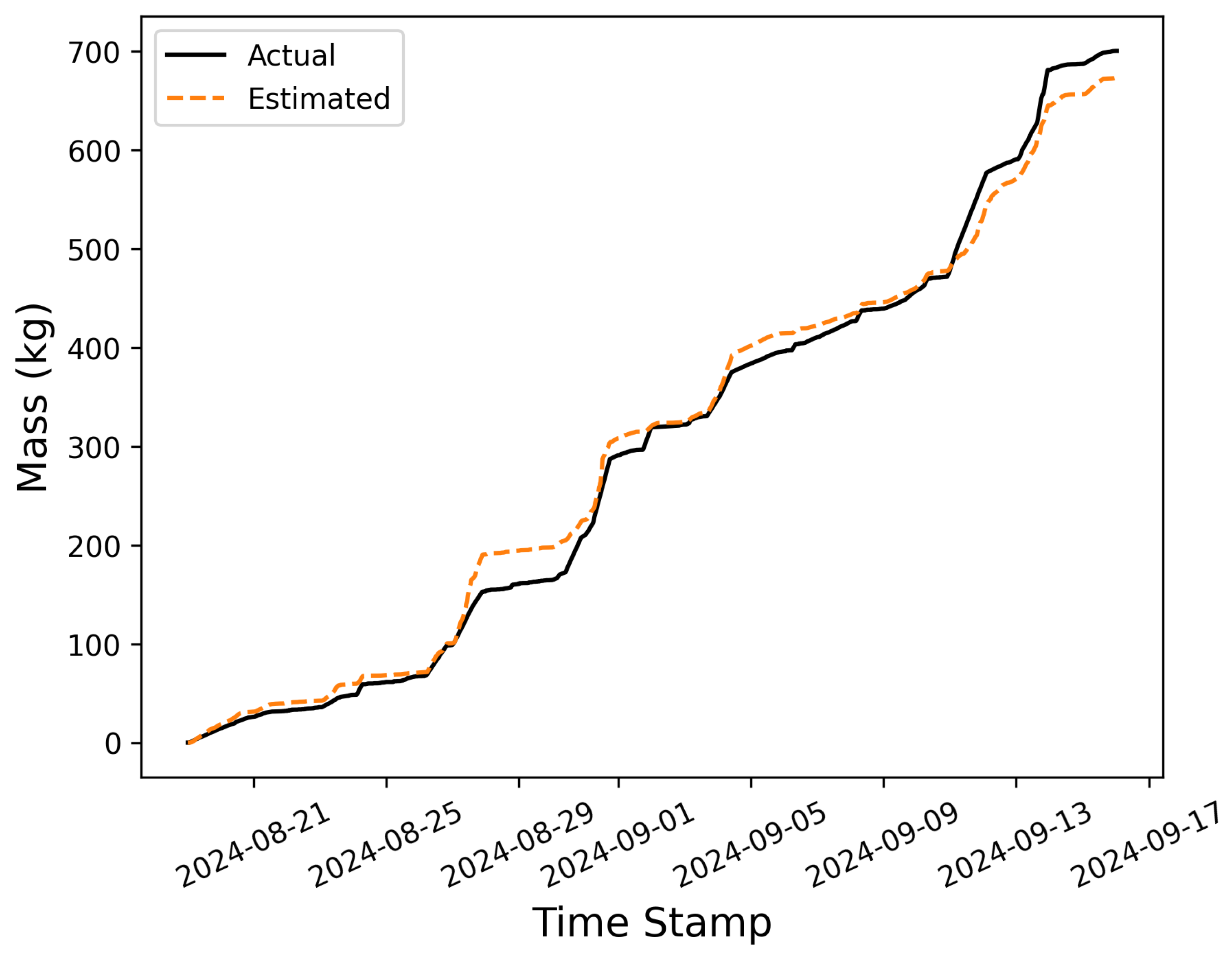

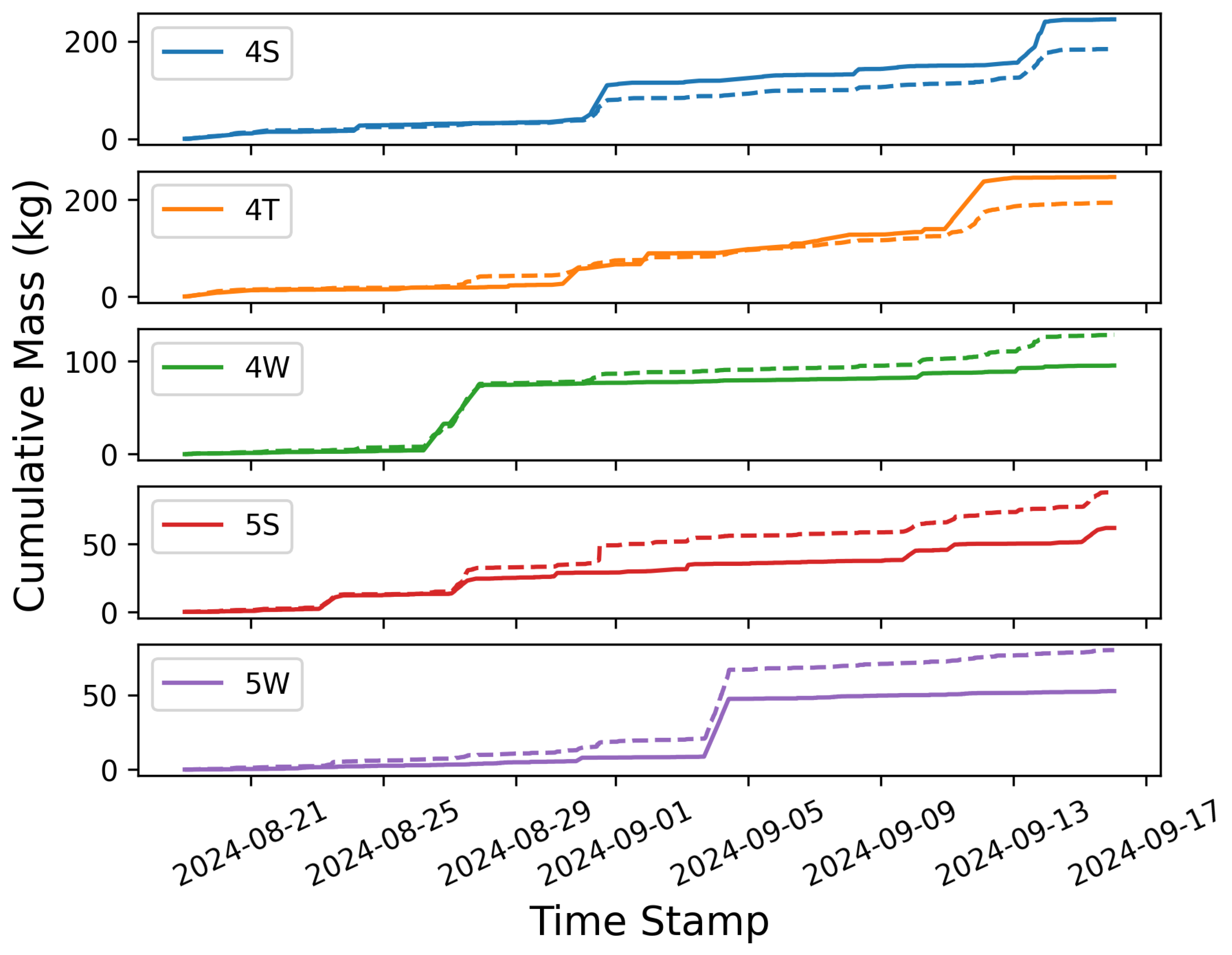

The selection of the proper performance evaluation metrics for CMS applications depends on the use case and the objective of the monitoring program. This study investigates the performance of one such system across a broad range of evaluative metrics, beginning with a direct comparison of 15-minute source emission rate estimates against ground-truth values. Subsequently, an analogous analysis is presented, focusing on extended-period time-averaged emission rates, which are generally more robust for informing actionable insights. This approach is grounded in findings from previous studies, which consistently indicate a high degree of variance in instantaneous quantification errors, but a low amount of bias, suggesting that longer-term (i.e., time integrated or averaged) estimates are generally more robust [

1,

7]. Next, cumulative mass emission estimates are compared to the actual cumulative gas release volumes to provide a comprehensive understanding of the system’s performance over time. This analysis is performed both at the site-level and also per source-group, to assess the efficacy of the system at accounting for the total mass being emitted by the facility as well as its ability to properly allocate that mass to spatially-clustered pieces of equipment. Finally, to assess the effectiveness of these systems in identifying significant deviations from normal operating conditions (represented by the first week of emissions during the testing), a threshold-based analysis is employed to evaluate the system’s capacity to detect and alert anomalous emissions exceeding established operational baselines.

4. Discussion

This study, while offering valuable insights into the performance of the existing emissions quantification practices using fixed-point CMS solutions, is subject to certain limitations. These limitations are primarily related to the short duration of the testing period (one week of baseline emission releases and then three weeks of baseline plus "fugitive" controlled releases). While insightful for initial analysis, the relatively short duration of the testing results implies that the entire range of atmospheric conditions that these systems are subject to in the field may not be present during this limited testing period. For instance, environmental factors such as wind speed and variability in direction, temperature, and atmospheric stability may exhibit seasonal variations that are not represented within this dataset. To best understand the deployment of these systems in the field, longer tests across more varied environmental conditions, ideally spanning multiple geographic regions that may exhibit different atmospheric characteristics, are needed. Nevertheless, some of the basic trends related to instantaneous error versus time-integrated error and the conditions that give rise to source misattribution should generally hold, although the specific values and details of the convergence of evaluative metrics with averaging time may be subject to change depending on other environmental and operational factors.

Limited variability in environmental conditions may limit the extrapolation of the quantitative error metrics from this study to a broader context. For example, the mean emission rate error and various metrics associated with the parity plots (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4) are derived based on the existing, limited dataset. Additionally, a longer data collection period can result in smaller uncertainty bounds associated with the error rates for various averaging times (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Similarly, our evaluation of the existing CMS system’s capability to process varying emission rates is derived based on, and so, may be skewed by, the specific emission scenarios encountered during this limited-time controlled release testing study. A more comprehensive performance evaluation of the CMS systems can be done in the future using longer data collection studies under realistic operational scenarios that include a wider variety of emission patterns.

Another limitation of this study stems from the dense network of sensors employed during the trial period of this testing campaign. In typical field deployments, CMS networks often contain between 3 and 6 sensors, however, for this blind test, there were 10 sensors deployed. Generally speaking, technology providers tend to deploy a dense sensor network at these testing centers. This decision is largely driven by the inherent value of obtaining a large volume of high-quality, ground-truth data from controlled release studies. These datasets help drive innovation, and the more data that is collected during these testing campaigns, the better solutions are able to refine physical dispersion models and associated inversion frameworks to improve their technology. Furthermore, deploying a dense network allows for the post-hoc investigation of system performance as a function of sensor density and configuration. In other words, the same quantification algorithm can be run across different subsets of the sensors to understand how the reliability of the output is dependent on the specific geometry of sources with respect to sensors and the sensor density. The drawback of deploying a dense network for this study is that the results are not representative of field deployments and, as such, represent a best-case scenario in terms of DLQ accuracy. Therefore, these results need to be interpreted in this context. In general, the expectation is that source misattribution will become more prevalent with a smaller number of sensors because there are fewer sensors capable of breaking degeneracies between sources.

Section 3.3.1 investigates a limited selection of cases where there is a single primary factor contributing to source misattribution. As a result, straightforward conclusions can be made related to the root causes of the system performance degradation. However, in other cases, different factors may contribute to source misattribution.

While source-level emission rate quantification at high temporal resolution (e.g., 15-minute estimates) offers a snapshot of emission rates at a specific moment, these estimates come with inherently higher uncertainties. As such, using only these short-duration estimates to derive insights may lead to a misunderstanding of true emission rates and result in wasted effort investigating what was only a spike in the noise of the emissions estimate. Note that in many applications, the objective of quantification is to either determine the contribution of different sources to the overall site-level emissions over an extended period of time, or to estimate the cumulative amount of emissions (or equivalently, average rate) over a long time period (e.g., a minimum of 4-hour averaging). While mitigating the noise of the short-duration estimates would be helpful, due to some of the primary applications of CMS, reducing the bias of the system’s quantification output is even more critical because it will result in more accurate quantification when longer-term averaging is considered.

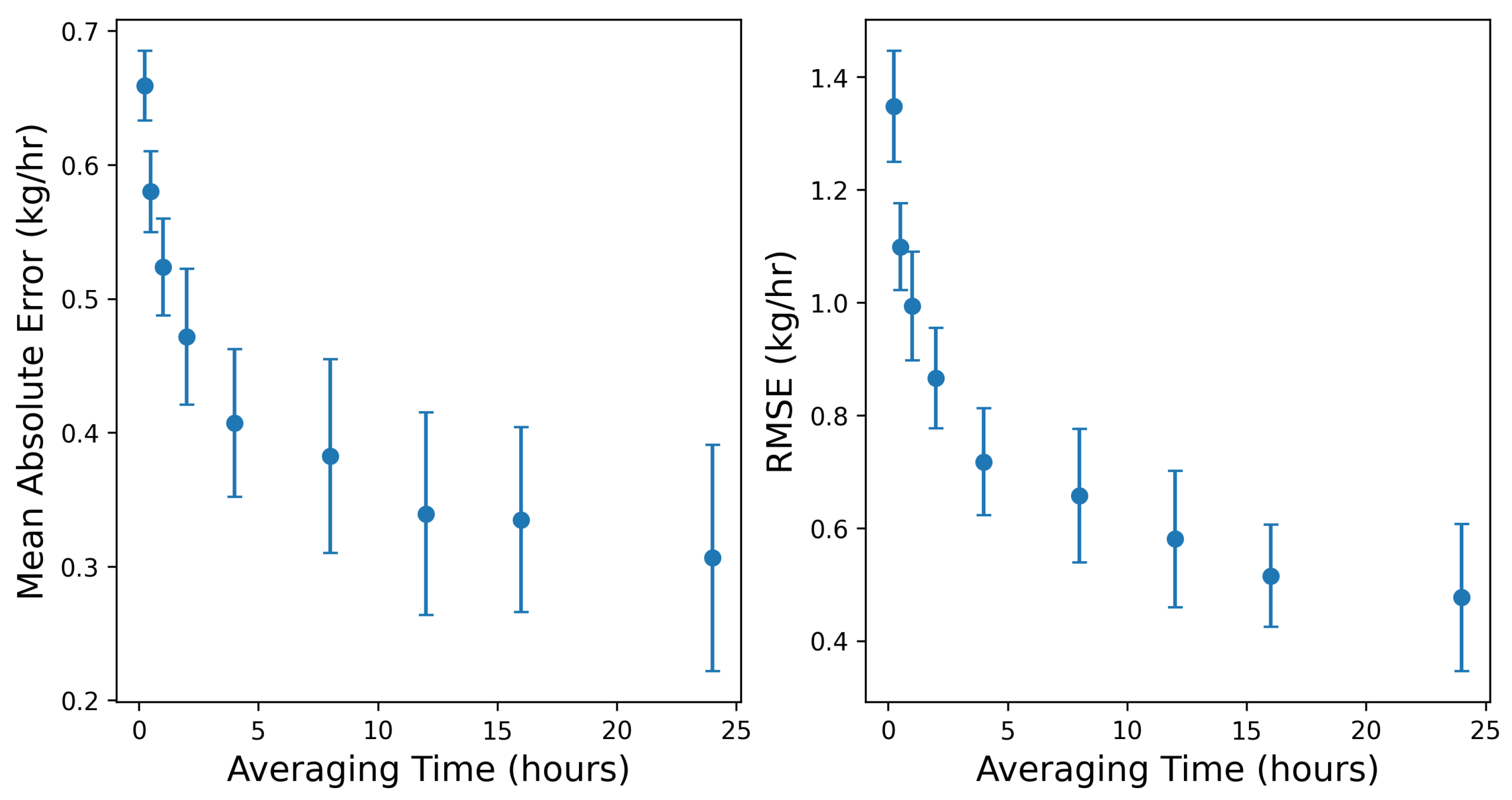

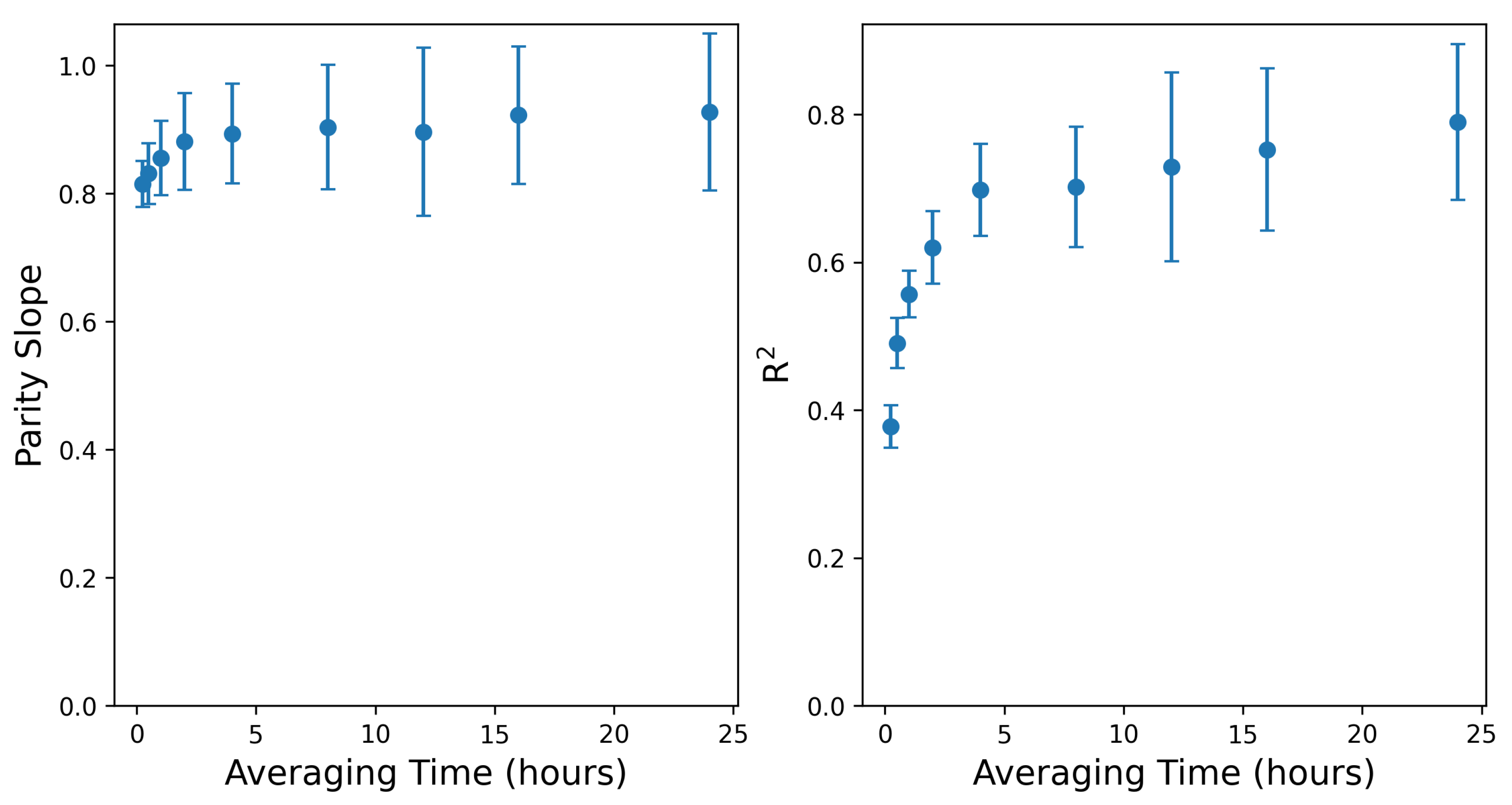

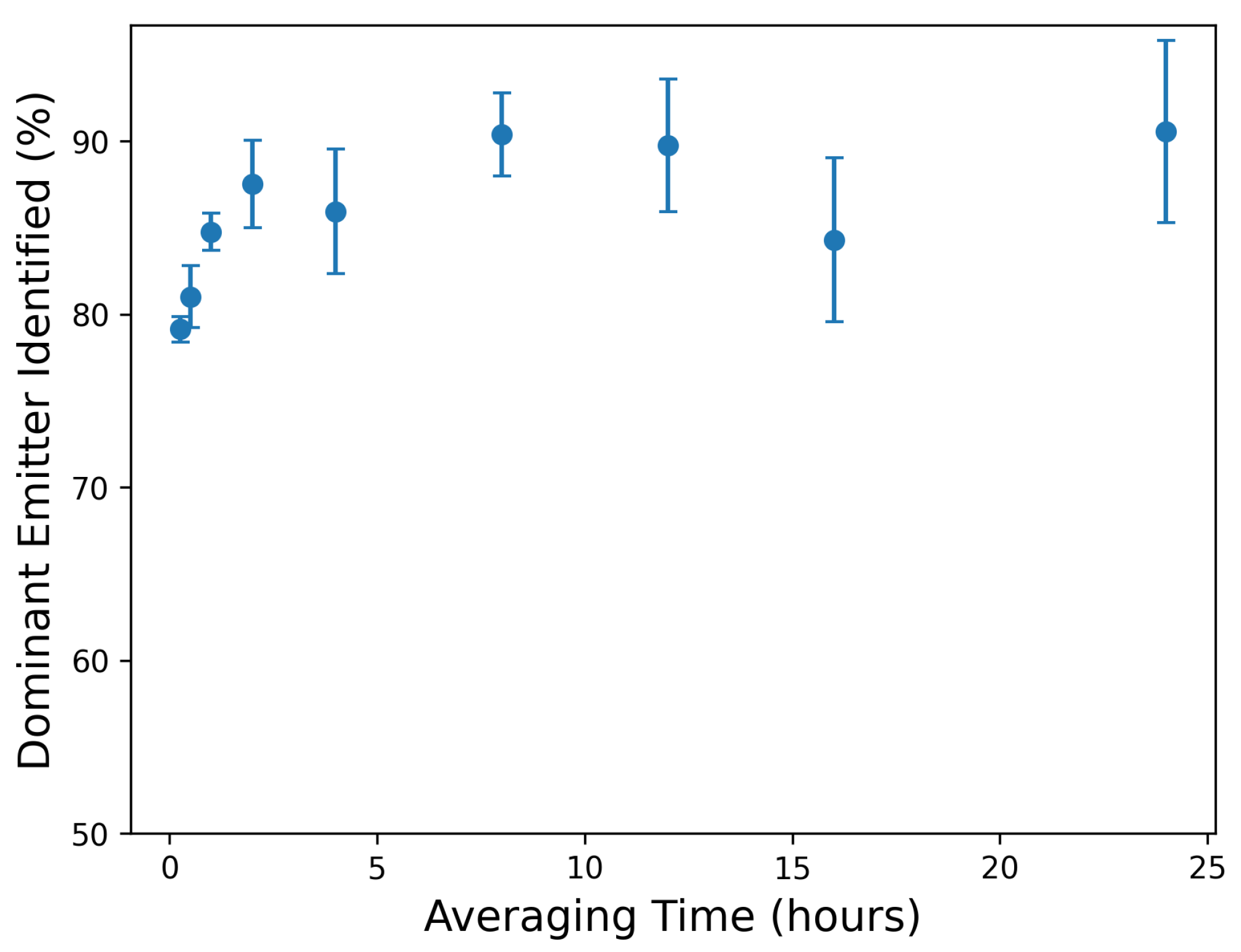

The near-zero bias of the existing system is promising. It indicates that the appropriate selection of the averaging time window can improve the reliability of site-level emission rate estimates. As previously discussed, a short averaging window often fails to adequately mitigate the inherent noise in the short-duration estimates. On the contrary, an overly extended averaging window may reduce the amount of actionable insights present in the quantification signals. Therefore, the averaging time length matters:

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 suggest a steep improvement in the performance of the system by increasing the averaging time to 4 hours. Increasing the averaging time from 4 to 12 hours still results in some gains in the system’s performance. As the averaging time increases beyond 12 hours, various metrics for the improvement of the system start to exhibit plateaued behaviors. Note that there is no right or wrong selection for averaging time selection. Instead, this decision should be informed by the objective of the methane measurement and quantification program. In some applications, the averaging time may be dictated by external factors (such as satisfying the requirement defined by the EPA OOOOb regulation), while other cases may present more flexibility.

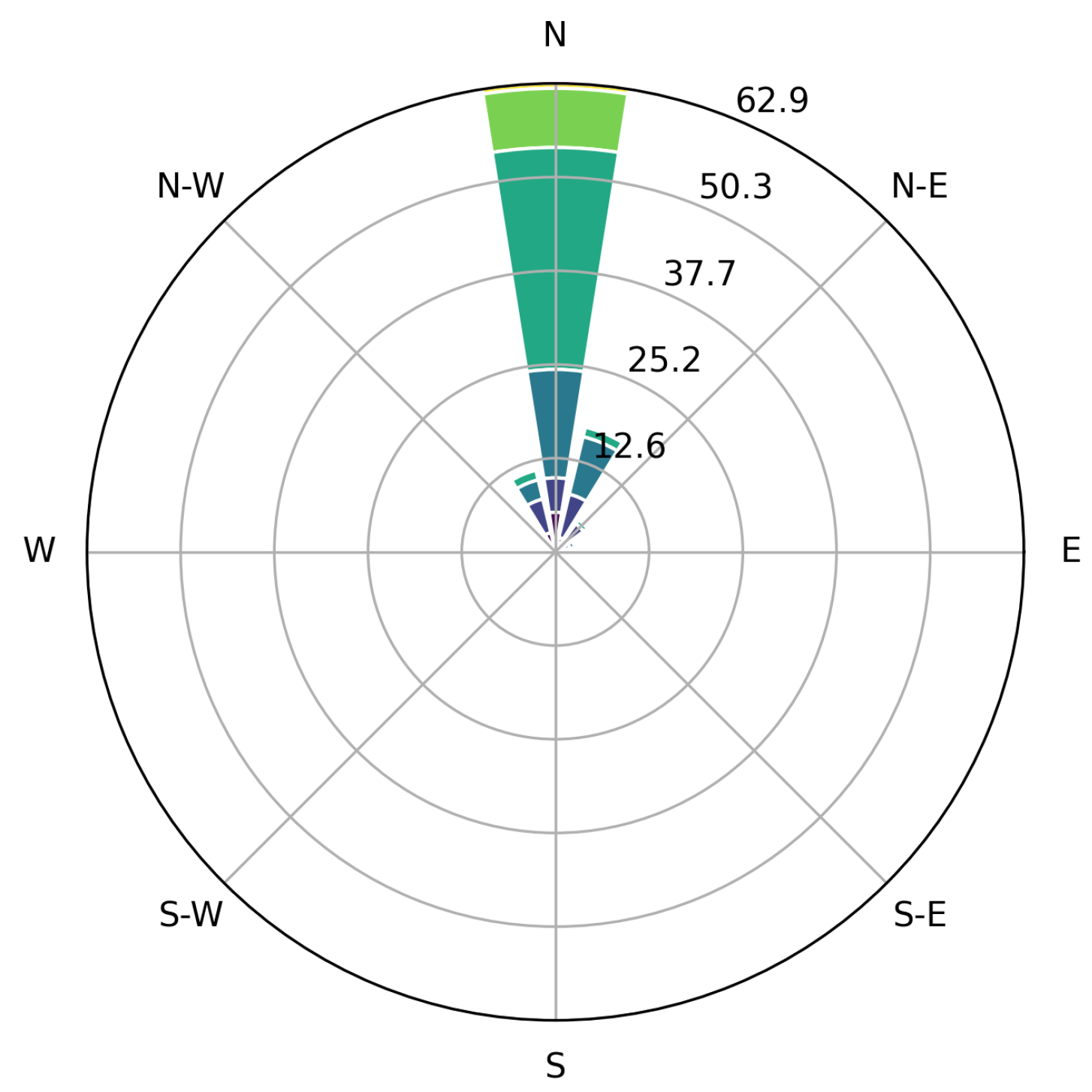

Lastly, because fixed-point sensors rely on the wind to advect emissions from sources to sensors, the statistics of wind direction and relative positioning of sources and sensors plays a critical role in the performance of the system in terms of distinguishing emissions between different sources. As demonstrated, source misattribution may occur when there is little wind variability. This is an unavoidable limitation of these systems unless additional prior information or assumptions (e.g., operational data, independent measurements, aggressive sparsity promotion) are used to constrain or inform the emission estimates. As such, care should be taken when interpreting the equipment-specific emission rates in operational scenarios. In other words, the variability of wind direction and relative positioning of equipment and sensors should be considered before making decisions based on emissions estimates from point sensor networks to help mitigate the potential for equipment-specific "false positive" alerts.

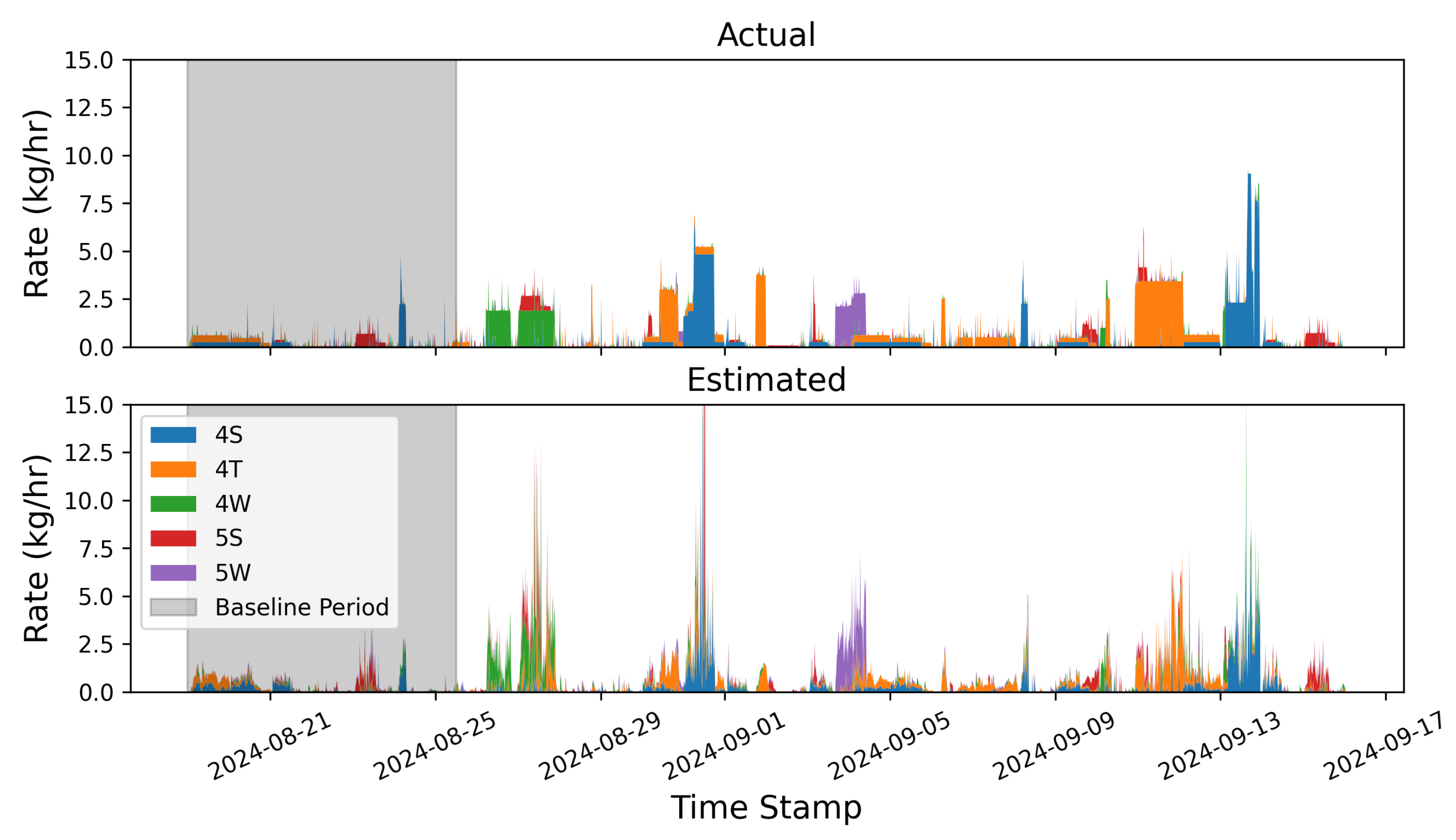

Figure 1.

Stacked bar charts showing the actual (estimated) emission rates in the top (bottom) panels, with each color corresponding to a source group. The duration of the baseline period is indicated with a shaded gray region.

Figure 1.

Stacked bar charts showing the actual (estimated) emission rates in the top (bottom) panels, with each color corresponding to a source group. The duration of the baseline period is indicated with a shaded gray region.

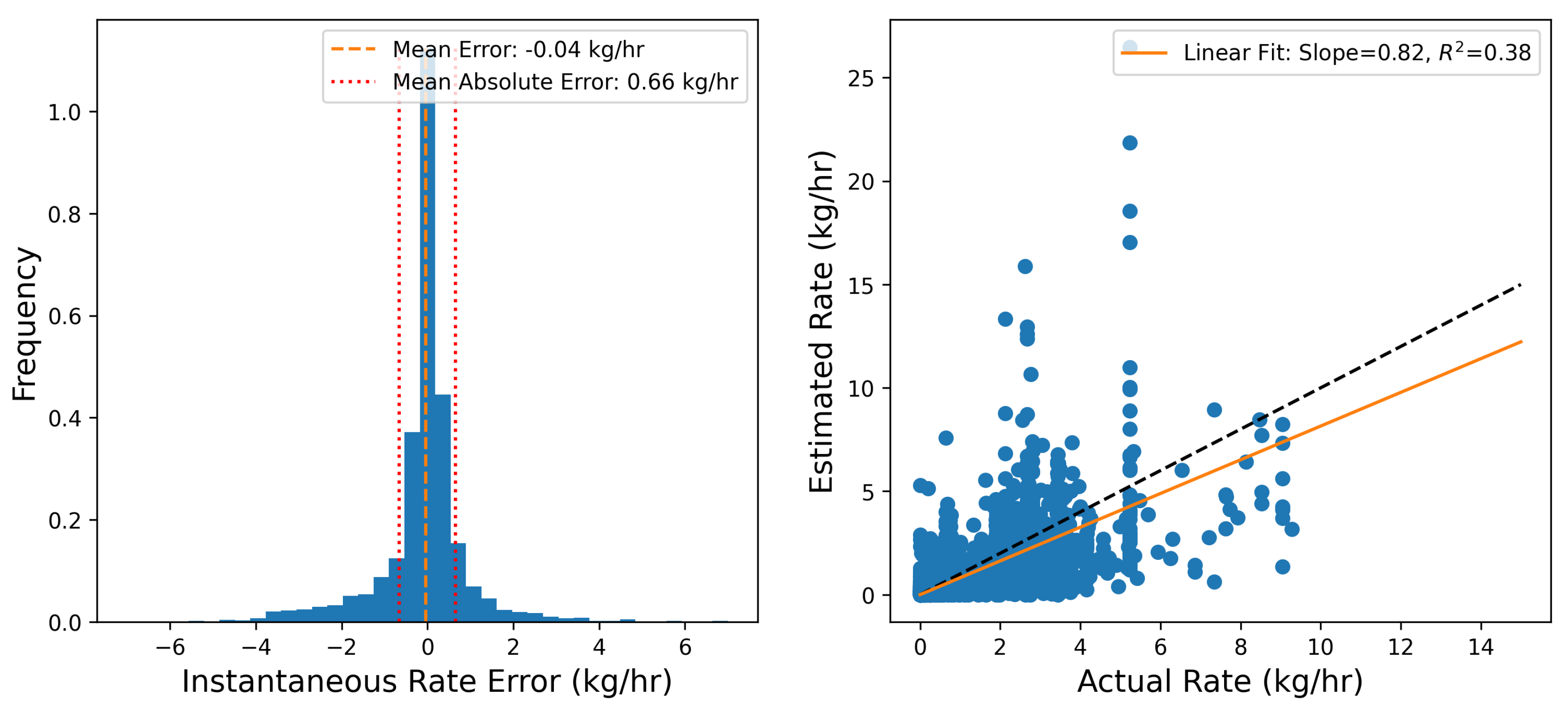

Figure 2.

Left Panel: Histogram of the 15-minute emission rate estimate errors, with the mean error (-0.04 kg/hr) and mean absolute error ( kg/hr) indicated in vertical dashed lines. Right Panel: Parity plot of the 15-minute emission rate estimate compared to the actual emission rates, with the linear fit and the parity relation indicated with orange line and dashed black line, respectively.

Figure 2.

Left Panel: Histogram of the 15-minute emission rate estimate errors, with the mean error (-0.04 kg/hr) and mean absolute error ( kg/hr) indicated in vertical dashed lines. Right Panel: Parity plot of the 15-minute emission rate estimate compared to the actual emission rates, with the linear fit and the parity relation indicated with orange line and dashed black line, respectively.

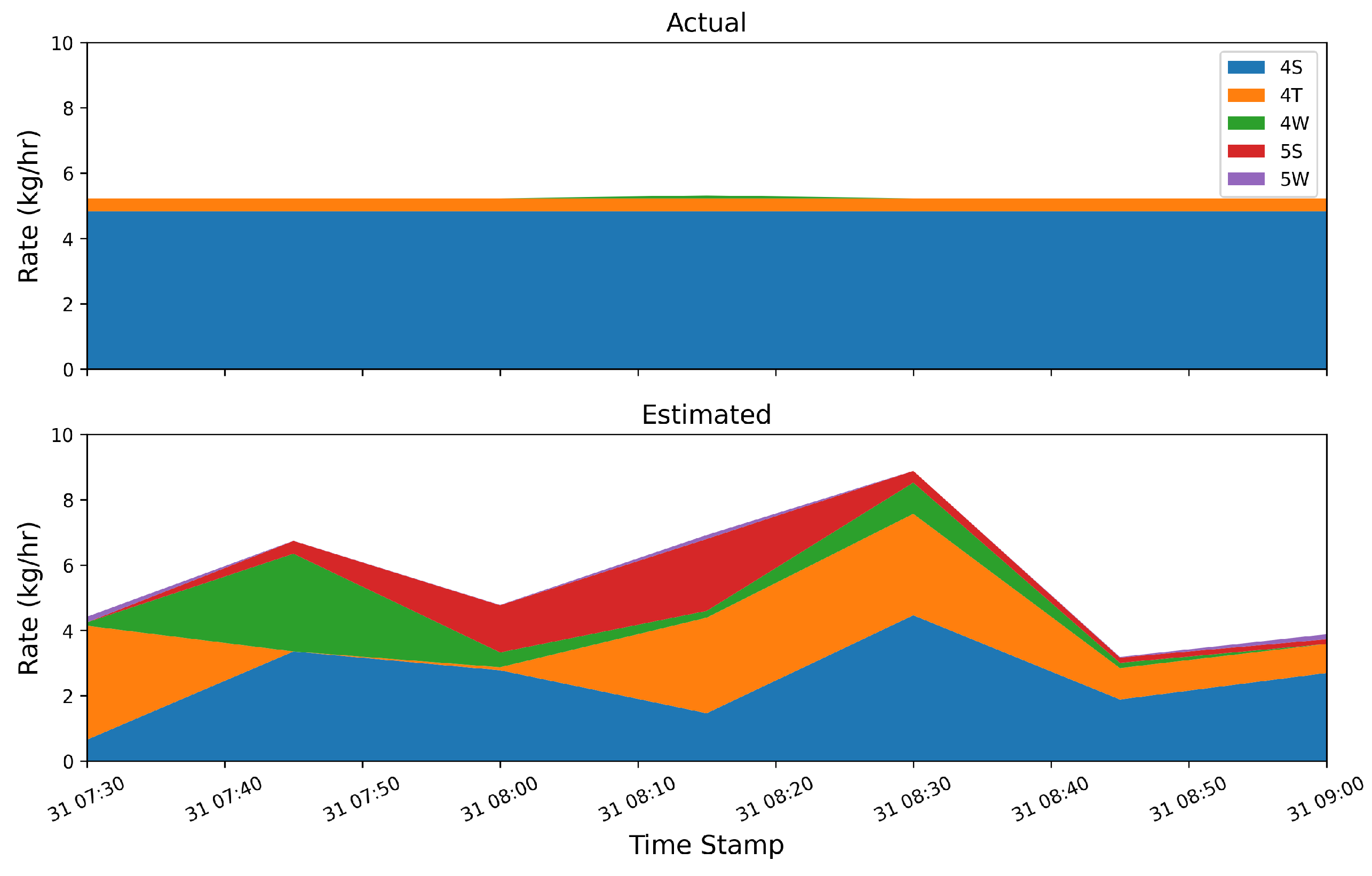

Figure 3.

Actual (top) and estimated (bottom) 12-hour aggregated rates.

Figure 3.

Actual (top) and estimated (bottom) 12-hour aggregated rates.

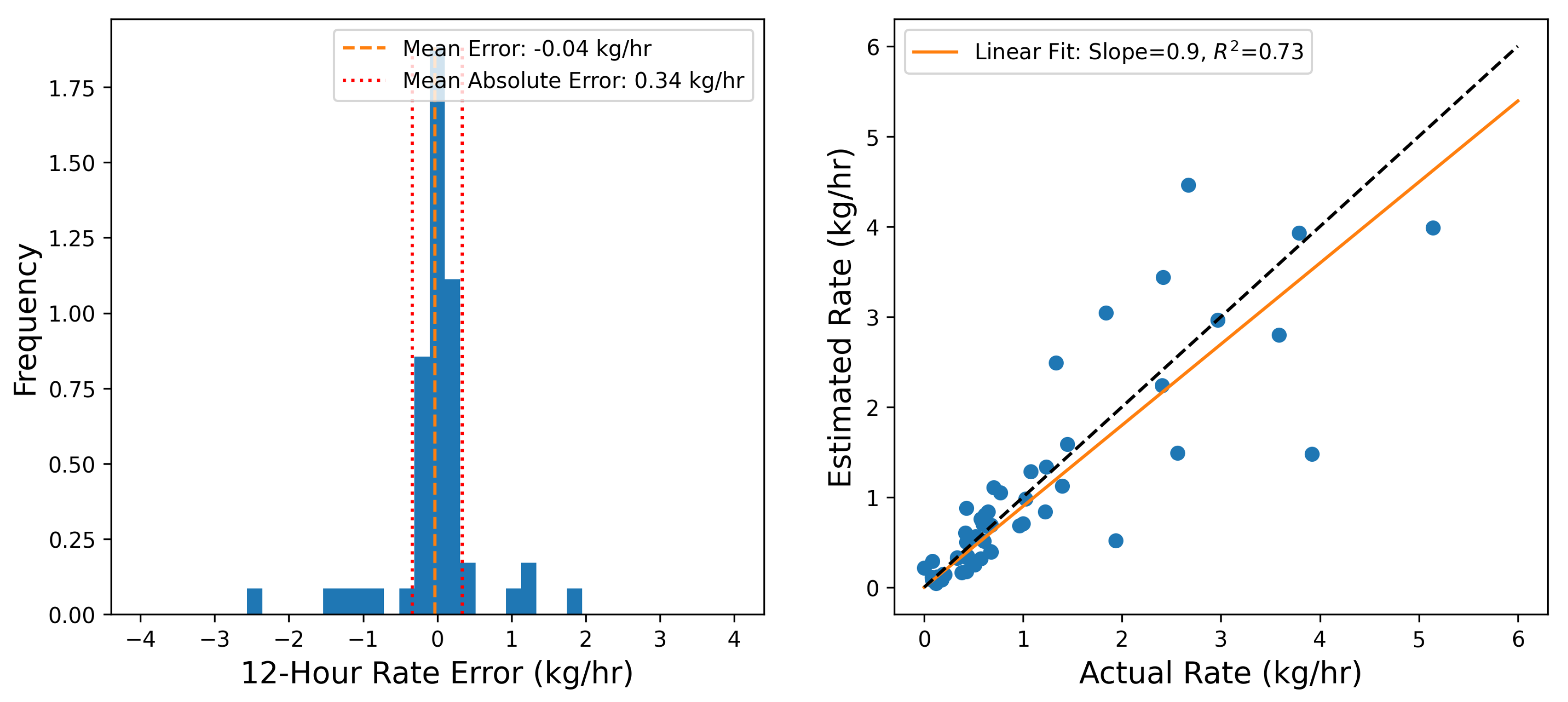

Figure 4.

Left Panel: Histogram of the 12-hour emission rate estimate errors, with the mean error (-0.04 kg/hr) and mean absolute error ( kg/hr) indicated with vertical lines. Right Panel: Parity plot of the 12-hour emission rate estimate compared to the actual emission rates, with the linear fit and the parity relation indicated with orange line and dashed black line, respectively.

Figure 4.

Left Panel: Histogram of the 12-hour emission rate estimate errors, with the mean error (-0.04 kg/hr) and mean absolute error ( kg/hr) indicated with vertical lines. Right Panel: Parity plot of the 12-hour emission rate estimate compared to the actual emission rates, with the linear fit and the parity relation indicated with orange line and dashed black line, respectively.

Figure 5.

Mean absolute error (left panel) and root mean squared error (right panel) as a function of averaging time.

Figure 5.

Mean absolute error (left panel) and root mean squared error (right panel) as a function of averaging time.

Figure 6.

Slope of parity line (left panel) and associated (right panel) as a function of averaging time.

Figure 6.

Slope of parity line (left panel) and associated (right panel) as a function of averaging time.

Figure 7.

Correctly-identified dominant emitter percentage as a function of averaging time.

Figure 7.

Correctly-identified dominant emitter percentage as a function of averaging time.

Figure 8.

Cumulative emissions from the testing center (black), and cumulative estimated emissions (dashed orange).

Figure 8.

Cumulative emissions from the testing center (black), and cumulative estimated emissions (dashed orange).

Figure 9.

Cumulative emissions curves for each individual equipment group. Estimated quantities are shown with dashed lines while true releases are depicted with solid lines.

Figure 9.

Cumulative emissions curves for each individual equipment group. Estimated quantities are shown with dashed lines while true releases are depicted with solid lines.

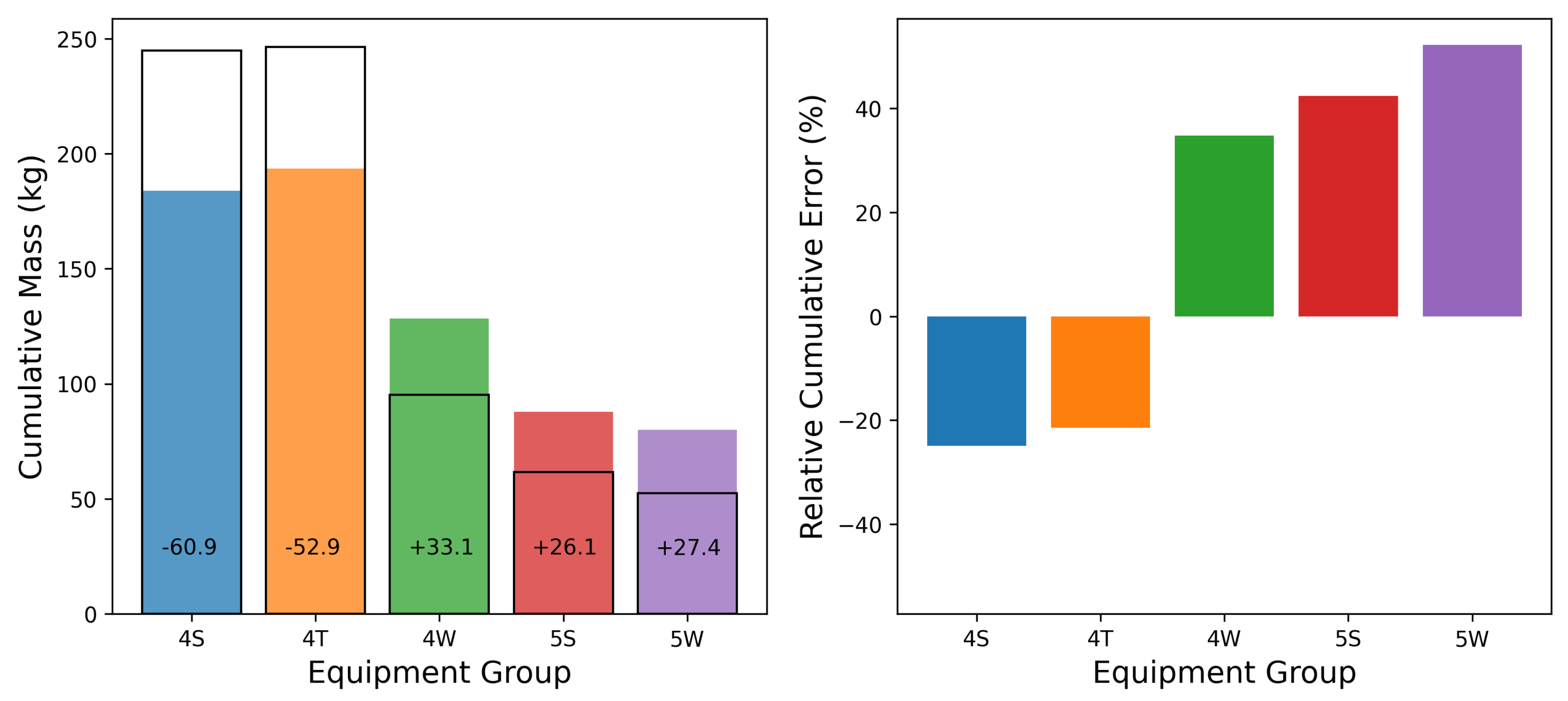

Figure 10.

Equipment-group specific cumulative emissions (estimated and actual, left), and relative cumulative error (right).

Figure 10.

Equipment-group specific cumulative emissions (estimated and actual, left), and relative cumulative error (right).

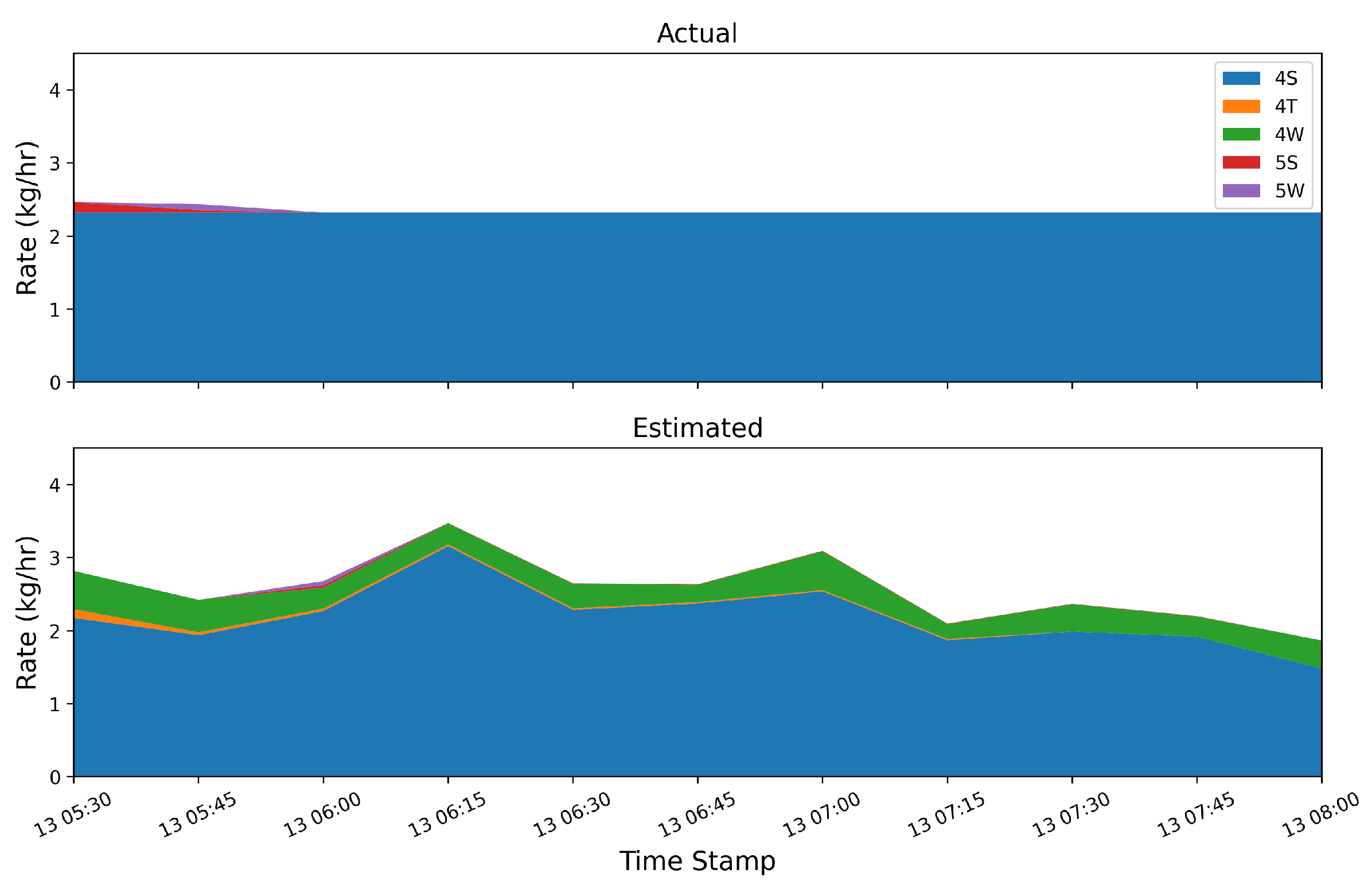

Figure 11.

Actual (top) and estimated (bottom) emission rates by group during a an emission event from the 4S group that shows significant source misattribution in the estimated rates.

Figure 11.

Actual (top) and estimated (bottom) emission rates by group during a an emission event from the 4S group that shows significant source misattribution in the estimated rates.

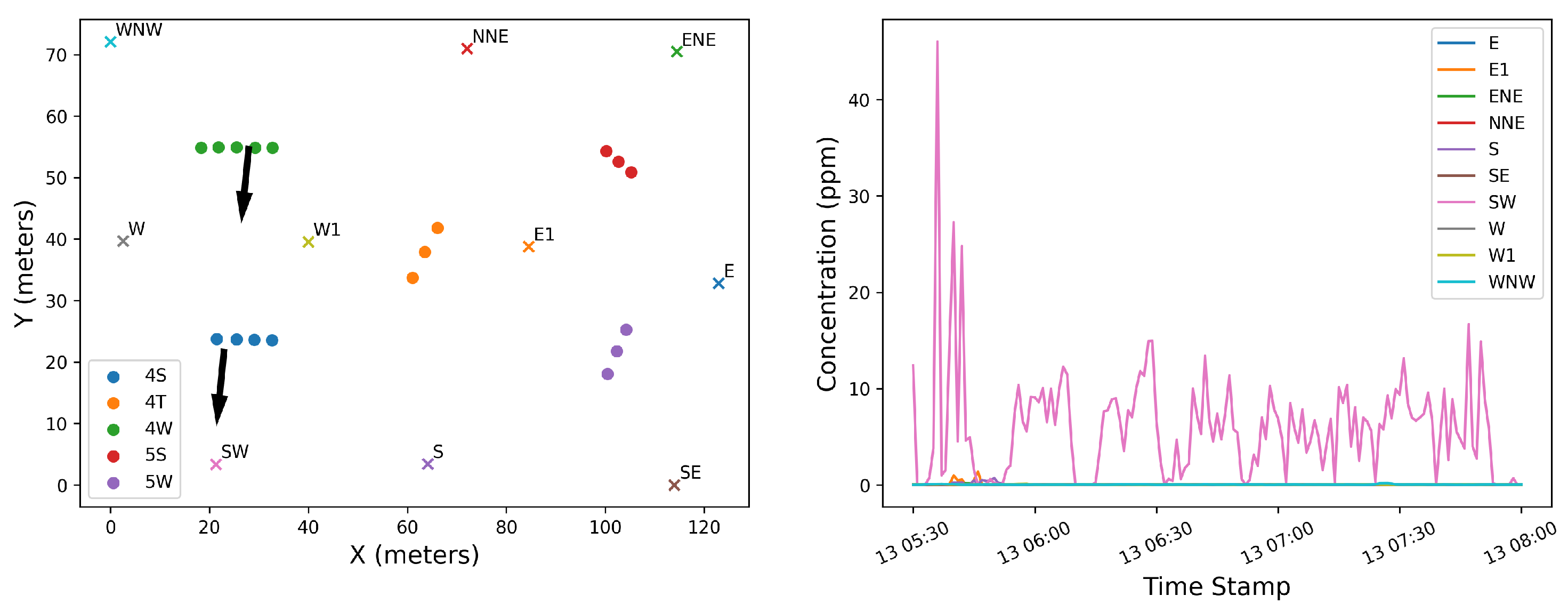

Figure 12.

Layout of sources (dots), sensors (x’s), and mean wind direction (arrows) during time period with significant source misattribution. Only a single sensor captures elevated concentrations downwind of multiple potential source groups.

Figure 12.

Layout of sources (dots), sensors (x’s), and mean wind direction (arrows) during time period with significant source misattribution. Only a single sensor captures elevated concentrations downwind of multiple potential source groups.

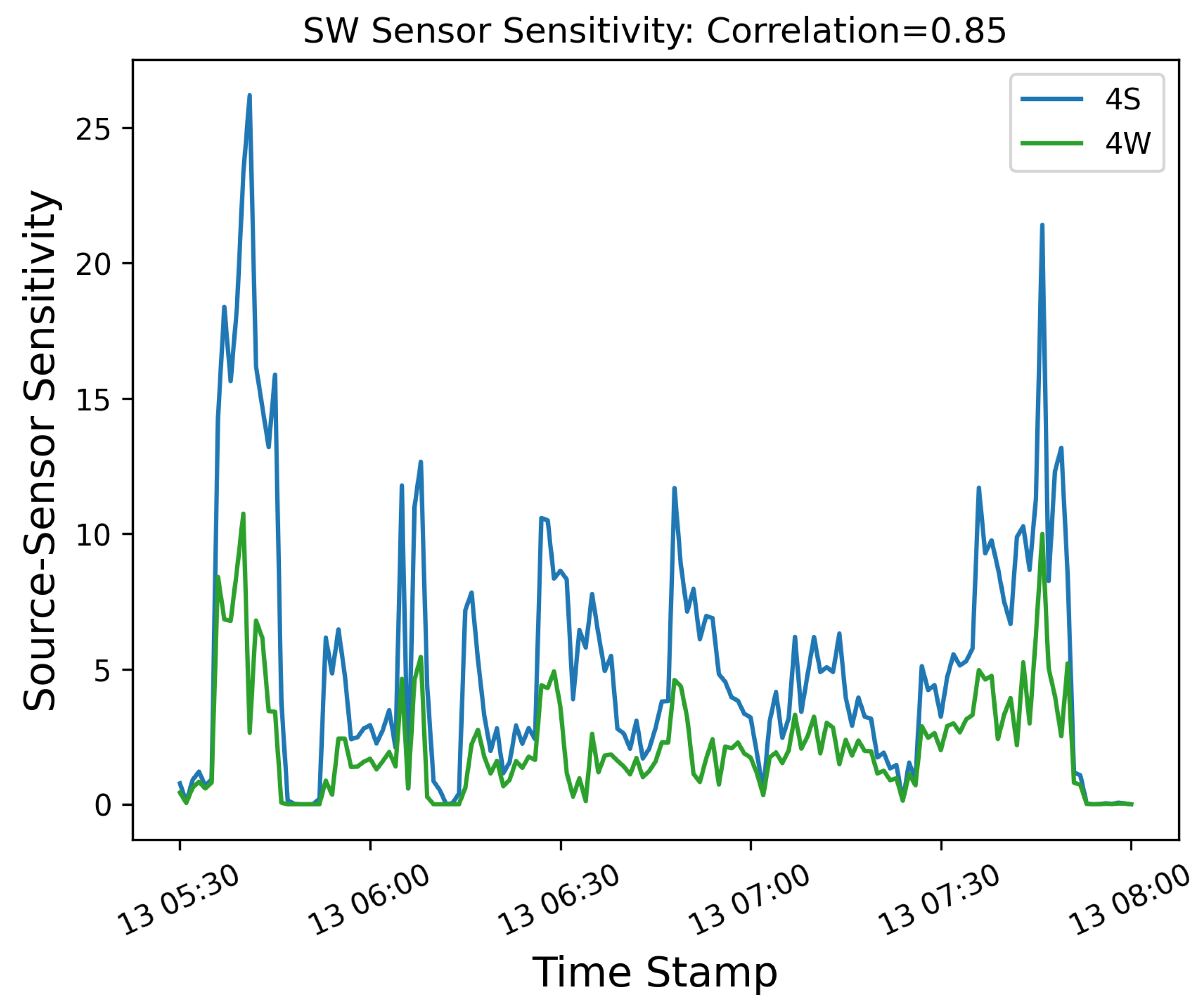

Figure 13.

Wind rose during selected time period, demonstrating the small degree of wind direction variability.

Figure 13.

Wind rose during selected time period, demonstrating the small degree of wind direction variability.

Figure 14.

Source-Sensor sensitivity for the 4S and 4W groups computed for the SW sensor. A high degree of correlation between the signals exists due to the specific geometry and uniform wind direction: because the sensor is directly downwind from both sources for the duration of the emission event, there is very little information that can help disambiguate between these two sources.

Figure 14.

Source-Sensor sensitivity for the 4S and 4W groups computed for the SW sensor. A high degree of correlation between the signals exists due to the specific geometry and uniform wind direction: because the sensor is directly downwind from both sources for the duration of the emission event, there is very little information that can help disambiguate between these two sources.

Figure 15.

Period of source confusion, during which the estimated emissions are erroneously attributed to 4 distinct equipment groups, when only 2 of the groups are emitting significantly.

Figure 15.

Period of source confusion, during which the estimated emissions are erroneously attributed to 4 distinct equipment groups, when only 2 of the groups are emitting significantly.

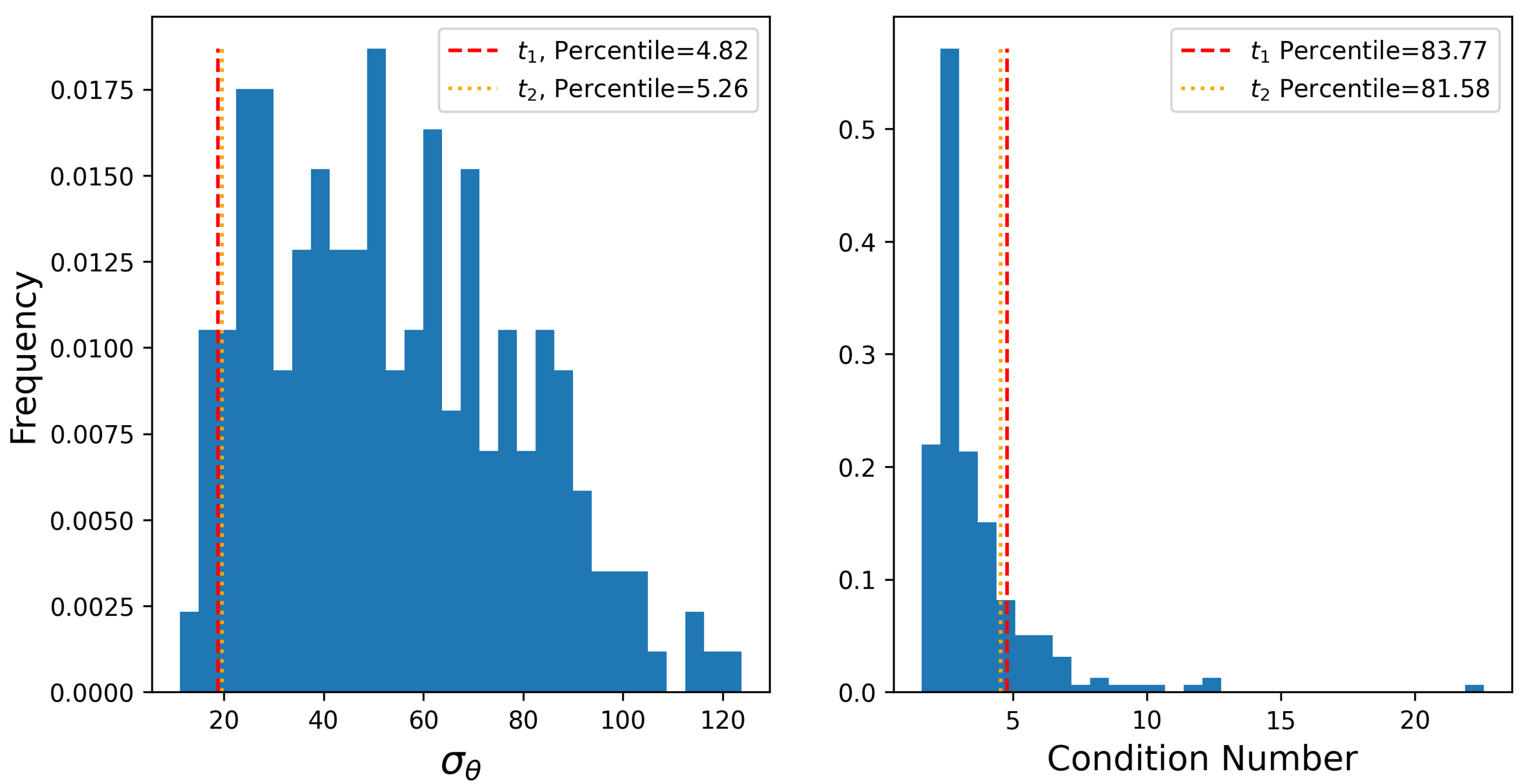

Figure 16.

Histogram of circular standard deviation of wind direction (left) and condition number of sensitivity matrix (right) for every three-hour time window during the testing period. The respective values from the manually-identified time periods, ( and ) with significant source misattribution are shown with dashed vertical lines.

Figure 16.

Histogram of circular standard deviation of wind direction (left) and condition number of sensitivity matrix (right) for every three-hour time window during the testing period. The respective values from the manually-identified time periods, ( and ) with significant source misattribution are shown with dashed vertical lines.

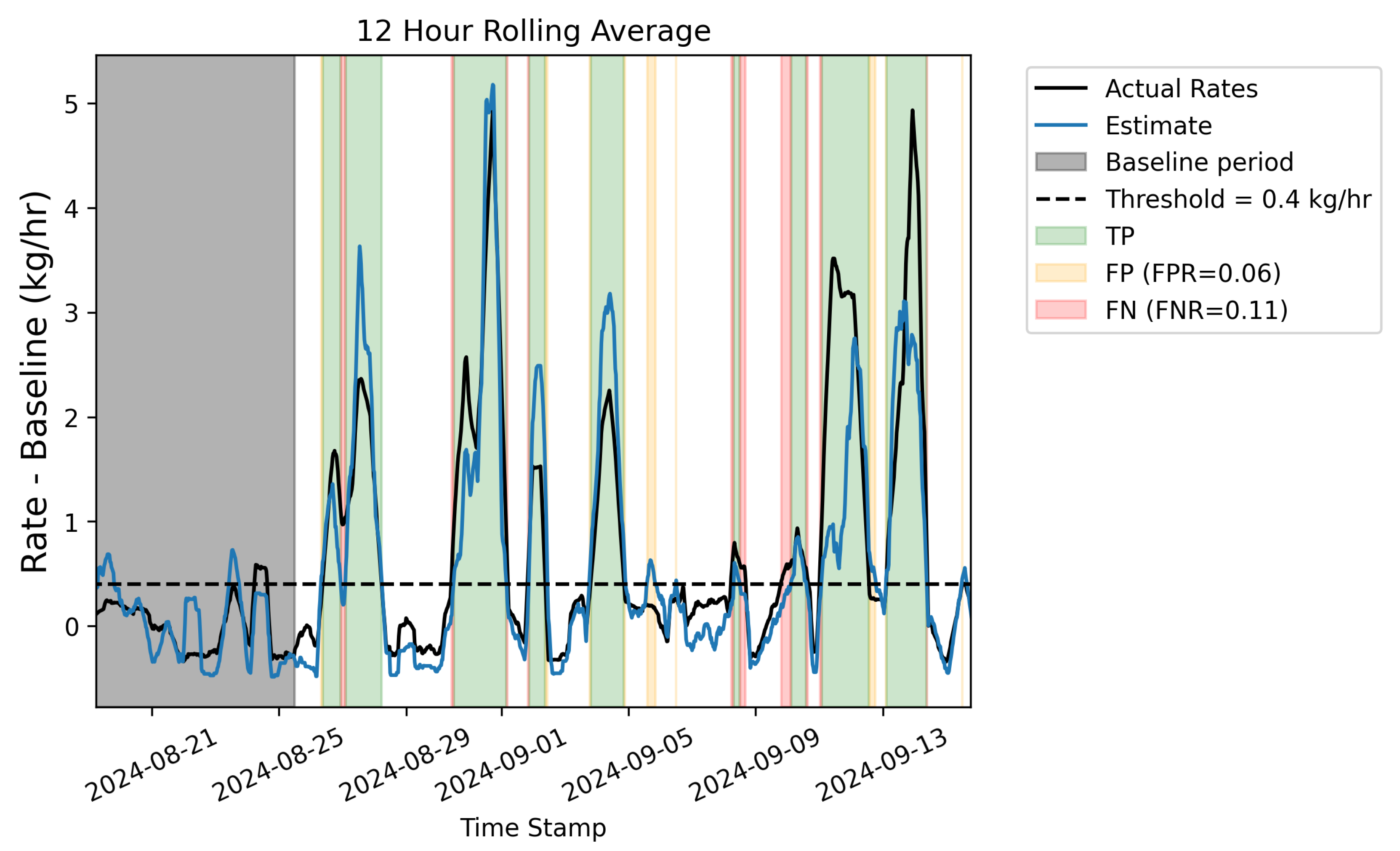

Figure 17.

12-hour rolling average of actual emission rate (black line), estimated rate (blue line). The black dashed line depicts a threshold of 0.4 kg/hr over the mean baseline (the baseline period is shown with a gray shaded region), and the green, orange, and red shaded regions depict periods that correspond to true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.

Figure 17.

12-hour rolling average of actual emission rate (black line), estimated rate (blue line). The black dashed line depicts a threshold of 0.4 kg/hr over the mean baseline (the baseline period is shown with a gray shaded region), and the green, orange, and red shaded regions depict periods that correspond to true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively.