Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The Model

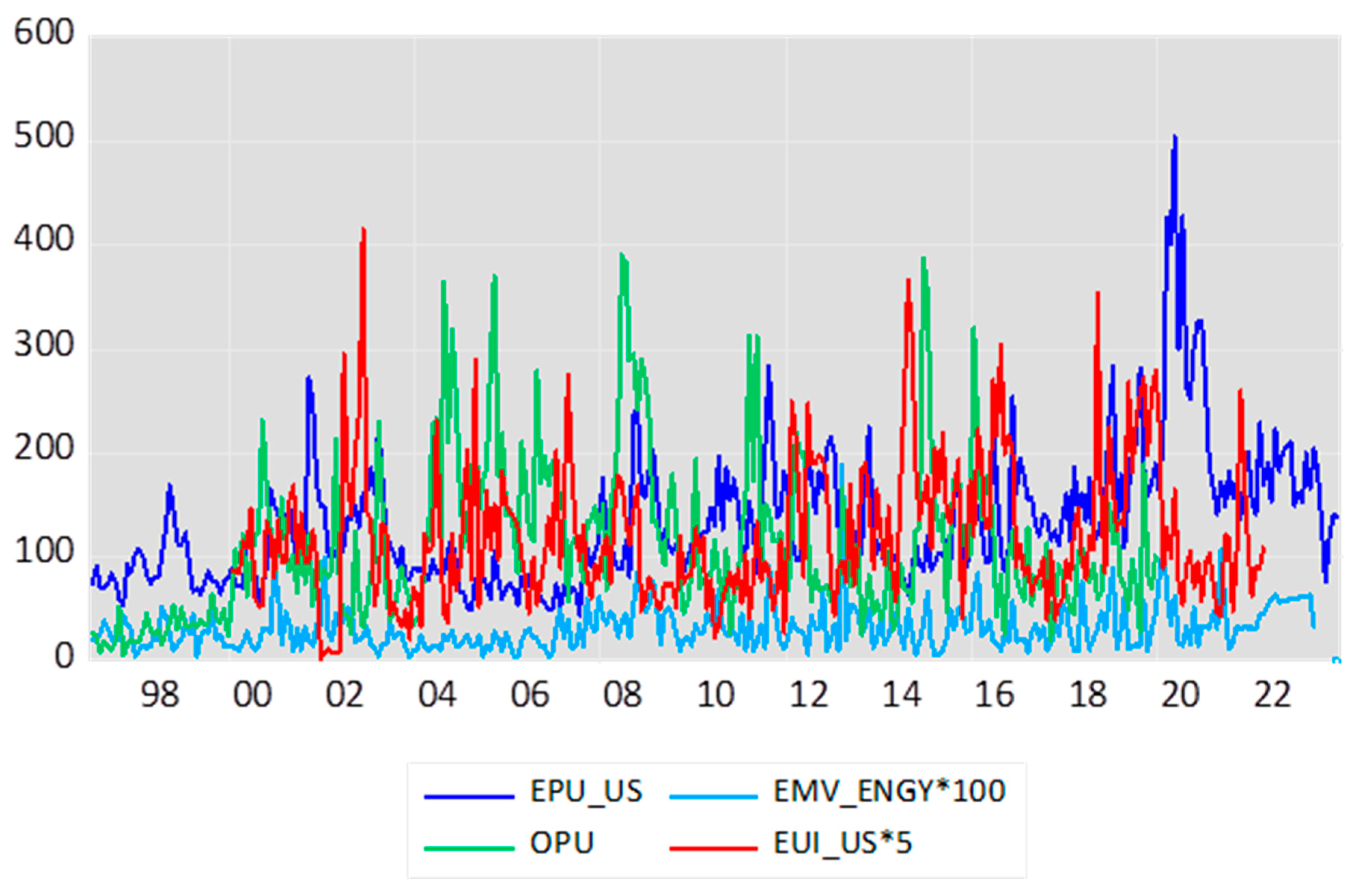

4. Data Selection and Description

5. Empirical Evidence

5.1. Empirical Results

5.2. Evidence of Energy Price Changes

5.2.1. Impact of Energy Uncertainty Index and Crude Oil Price Changes

5.2.2. Robustness Checks for Using Gasoline Price Changes

| Sector | C | Dum | |||||||||

| ENGY | 2.852 | -0.009 | -0.830 | -0.005 | -0.012 | 0.166 | -3.310 | 18.554 | 0.196 | 0.905 | 0.18 |

| 10.28 | -6.94 | -2.29 | -4.19 | -2.91 | 18.69 | -1.89 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 2.69 | ||

| BMAT | 4.376 | -0.013 | -0.418 | -0.013 | -0.009 | 0.097 | -6.668 | 18.660 | 0.787 | 0.729 | 0.10 |

| 22.17 | -8.34 | -8.53 | -21.47 | -5.89 | 10.65 | -3.05 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 1.87 | ||

| CDIS | 2.401 | -0.002 | -0.523 | -0.005 | -0.023 | 0.021 | -6.932 | 12.282 | 0.298 | 0.939 | 0.01 |

| 13.21 | -1.90 | -1.88 | -9.81 | -4.55 | 3.76 | -12.51 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 4.09 | ||

| CSTP | 2.034 | -0.003 | -0.167 | -0.001 | -0.025 | 0.016 | -2.666 | 7.128 | 0.183 | 0.861 | 0.04 |

| 12.87 | -5.52 | -1.87 | -6.46 | -9.45 | 2.22 | -4.35 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.97 | ||

| FINA | 4.439 | -0.009 | -2.087 | -0.012 | -0.021 | 0.001 | -0.661 | 20.733 | 1.829 | 0.789 | 0.05 |

| 12.01 | -4.34 | -4.47 | -7.75 | -2.71 | 6.21 | -2.40 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 2.60 | ||

| HLTH | 2.010 | -0.001 | -1.731 | -0.002 | -0.006 | 0.021 | -3.185 | 9.398 | 0.196 | 0.869 | 0.04 |

| 21.35 | -2.19 | -7.83 | -3.46 | -1.70 | 6.14 | -3.86 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 1.62 | ||

| INDU | 3.840 | -0.008 | -1.802 | -0.009 | -0.006 | 0.055 | -4.566 | 12.448 | 0.835 | 0.727 | 0.08 |

| 12.07 | -4.29 | -3.64 | -6.58 | -4.04 | 8.36 | -1.81 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 1.92 | ||

| RLES | 4.433 | -0.005 | -3.661 | -0.003 | -0.044 | -0.007 | -0.169 | 4.428 | 0.276 | 0.800 | 0.03 |

| 22.17 | -3.29 | -6.63 | -5.71 | -7.84 | -2.79 | -1.84 | 0.61 | 0.88 | 3.58 | ||

| TECH | 2.550 | -0.008 | -1.337 | -0.011 | 0.024 | 0.068 | -3.022 | 7.175 | 0.776 | 0.746 | 0.04 |

| 7.25 | -2.54 | -7.82 | -5.92 | 2.96 | 10.15 | -1.99 | 0.48 | 0.82 | 2.80 | ||

| TELE | 0.426 | 0.000 | -2.431 | -0.002 | 0.024 | 0.012 | -1.368 | 102.064 | 7.611 | 0.813 | 0.00 |

| 1.73 | 2.33 | -6.06 | -3.59 | 5.34 | 2.84 | -0.62 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 1.83 | ||

| UTIL | 1.665 | -0.003 | -0.287 | 0.005 | -0.035 | 0.032 | -2.808 | 11.938 | 1.527 | 0.795 | 0.05 |

| 9.64 | -2.30 | -7.22 | 8.98 | -7.89 | 4.78 | -2.87 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 2.32 |

6. Evidence of Climate Policy Changes

6.1. Direct Effect from Climate Policy Changes

- ,, and evidence shows that the majority of these variables continually present negative signs. However, in some instances, the coefficients turn to positive, which may be attributable to spurious correlations.

6.2. Interaction Between Changes in Oil Prices and Climate Policy Changes

7. Conclusions and Summary

References

- Hammoudeh, S.; Li, H. Oil sensitivity and systematic risk in oil-sensitive stock indices. J. Econ. Bus. 2005, 57, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filis, G.; Degiannakis, S.; Floros, C. Dynamic correlation between stock market and oil prices: The case of oil-importing and oil-exporting countries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2011, 20(3), 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Risk factors in stock returns of Canadian oil and gas companies. Energy Econ. 2001, 23, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, M.M.; Filion, D. Common and fundamental factors in stock returns of Canadian oil and gas companies. Energy Econ. 2007, 29, 428–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandha, M.; Faff, R. Does oil move equity prices? A global view. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.D. Historical oil shocks (NBER Working Paper 16790). NBER 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, I.; Kim, J. Oil price shocks and the US stock market: A nonlinear approach. J. Empir. Financ. 2021, 64, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.; Kaul, G. Oil and the stock markets. J. Finance 1996, 51, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L. Not all oil price shocks are alike: Disentangling demand and supply shocks in the crude oil market. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L.; Park, C. The impact of oil price shocks on the U.S. stock market. Int. Econ. Rev. 2009, 50, 1267–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; de Gracia, F.P.; Ratti, R.A. Oil price shocks, policy uncertainty, and stock returns of oil and gas corporations. J. Int. Money Finance 2017, 70, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Terry, S.J. Covid-induced economic uncertainty (No. w26983). NBER 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abiad, A.; Qureshi, I.A. The macroeconomic effects of oil price uncertainty. Energy Econ. 2023, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.-N.; Nguyen, C.P.; Lee, G.S.; Nguyen, B.Q.; Le, T.T. Measuring the energy-related uncertainty. Energy Econ. 2023, 124, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, E.M.; Molero, J.C.; de Gracia, F.P. Oil price volatility and stock returns in the G7 economies. Energy Econ. 2016, 54, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Du, W.; Ma, Y. Economic policy uncertainty, oil price volatility and stock market returns: Evidence from a nonlinear model. N. Am. J. Econ. Finance 2022, 62, 101777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, C.; Rath, B.N. The interconnectedness between crude oil prices and stock returns in G20 countries. Resour. Policy 2024, 91, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Luong, A.T. Dynamic spillovers between oil price, stock market, and investor sentiment: Evidence from the United States and Vietnam. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalman, Z. Oil price uncertainty and the US stock market analysis based on a GARCH-in-mean VAR model. Energy Econ. 2016, 59, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Ratti, R.A. Oil shocks, policy uncertainty and stock market return. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2013, 26, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, O.B.; Oliyide, J.A.; Kenku, O.T.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S. Comparative response of global energy firm stocks to uncertainties from the crude oil market, stock market, and economic policy. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcilar, M.; Gupta, R.; Kim, W.J.; Kyei, C. The role of economic policy uncertainties in predicting stock returns and their volatility for Hong Kong, Malaysia and South Korea. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2019, 59, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.C. Economic policy uncertainty, risk and stock returns: Evidence from G7 stock markets. Finance Res. Lett. 2019, 29, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, S.; Al-Khasawneh, J.A. Impact of economic policy uncertainty on stock markets of the G7 Countries: A nonlinear ARDL approach. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2022, 26, e00251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, J.A.; Kinateder, H.; Kinateder, P.G.; Wagner, N.F. Hedging stocks with oil. Energy Econ. 2021, 93, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Bai, R. Oil prices and economic policy uncertainty: Evidence from global, oil importers, and exporters’ perspective. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2021, 56, 101357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Kost, K. Policy news and stock market volatility (NBER Working Paper 25720). NBER 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gavriilidis, K. Measuring climate policy uncertainty. SSRN 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131(4), 1593–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodell, J.W. COVID-19 and finance: Agendas for future research. Finance Res. Lett. 2020, 35, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, M.A.; Faff, R.; Szulczyk, K.R. The 2008 global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic: How safe are the safe haven assets? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 83, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Oil price shocks and stock market activity. Energy Econ. 1999, 21, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharif, I.; Brown, D.; Burton, B.; Nixon, B.; Russell, A. Evidence on the nature and extent of the relationship between oil prices and equity values in the UK. Energy Econ. 2005, 27, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.B.; Veiga, H. Risk factors in oil and gas industry returns: International evidence. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, M.; Sahu, T.N.; Jana, S.S. Dynamics of oil price shocks and emerging stock market volatility: A generalized VAR approach. Vilakshan-XIMB J. Manag. 2021, 18, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, J.L. Oil price shocks and stock market behavior. J. Portfolio Manag. 1985, 12, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ratti, R. Oil price shocks and stock markets in the U.S. and 13 European countries. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 2587–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghyereh, A.; Awartani, B. Oil price uncertainty and equity returns: Evidence from oil importing and exporting countries in the MENA region. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2016, 8(1), 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faff, R.W.; Brailsford, T.J. Oil price risk and the Australian stock market. J. Energy Finance Dev. 1999, 4, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.G.; Wei, Y.M.; Jiao, J.L.; Fan, Y. Relationships between oil price shocks and stock market: An empirical analysis from China. Energy Policy 2008, 36(9), 3544–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporable, G.M.; Ali, F.M.; Spagnolo, N. Oil price uncertainty and sectoral stock returns in China: A time-varying approach. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 34, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chiou, J.S. Oil sensitivity and its asymmetric impact on the stock market. Energy 2011, 36, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.A.S.; Zwick, H.S. Oil price shocks and the US stock market: Slope heterogeneity analysis. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2016, 6, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Rabbani, M.R.; Bawazir, Hawaldar, I.T.; Chebab, D.; Karim, S.; AlAbbas, A. Oil price changes and stock returns: Fresh evidence from oil exporting and oil importing countries. Cogent Econ. Finance 2022, 10(1), 2018163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhang, Y. Climate policy uncertainty and the stock return predictability of the oil industry. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2022, 81, 101675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Rainey, I.; Gehricke, S.A.; Roberts, H.; Zhang, R. Trump vs. Paris: The impact of climate policy on US listed oil and gas firm returns and volatility. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 76, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, S.; Novan, K.; Peterman, W.B. The macro effects of climate policy uncertainty (Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2021-018). Fed. Reserve Board 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, M.; Foglia, M.; Bouri, E.; Dai, P.F. How does climate policy uncertainty affect financial markets? Evidence from Europe. Econ. Lett. 2024, 234, 111443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, H. The time-varying impact of uncertainty on oil market fear: Does climate policy uncertainty matter? Resour. Policy 2023, 82, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Bouri, E.; Saeed, T. News-based equity market uncertainty and crude oil volatility. Energy 2021, 222, 119930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollerslev, T. Glossary to ARCH (GARCH). In Volatility and Time Series Econometrics: Essays in Honor of Robert Engle; Bollerslev, T., Russell, J., Watson, M., Eds.; Oxford Univ. Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D. Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: A new approach. Econometrica 1991, 59, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K.; Pindyck, R.S. Irreversible Investment; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Narayan, P.K. What do we know about oil prices and stock returns? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2018, 57, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degiannakis, S.; Filis, G.; Arora, V. Oil prices and stock markets. Energy J. 2018, 39, 85–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, R.; Wang, S. Stock market volatility and return analysis: A systematic literature review. Entropy 2020, 22(5), 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.; Granger, C.W.; Engle, R.F. A long memory property of stock market returns and a new model. J. Empir. Finance 1993, 1(1), 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.C. Real stock market returns and inflation: Evidence from uncertainty hypotheses. Finance Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B.S. The relationship between stocks and oil prices. Brookings Commentary 2016, February 19.

- Barnett, M.; Brock, W.A.; Hansen, L.P. Pricing uncertainty induced by climate change. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2020, 33(3), 1024–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A.; Benkraiem, R.; Guesmi, K. The importance of climate policy uncertainty in forecasting the green, clean and sustainable financial markets volatility. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, U.; Sheikh, U.A.; Khalfaoui, R.; Roubaud, D.; Hammoudeh, S. Impact of climate policy uncertainty (CPU) and global energy uncertainty (EU) news on U.S. sectors: The moderating role of CPU on the EU and U.S. sectoral stock nexus. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Huermann, A. Impact of Weather on the Stock Market Returns of Different Industries in Germany. Junior Manag. Sci. 2020, 5, 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kocaarslan, B.; Ugur Soytas, U. Dynamic correlations between oil prices and the stock prices of clean energy and technology firms: The role of reserve currency (US dollar). Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Egan, P. Measuring contagion effects between crude oil and Chinese stock market sectors. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance 2018, 68, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.C.; Park, S. Oil prices and stock markets: Does the effect of uncertainty change over time? Energy Econ. 2017, 61, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K. Oil price shocks, competition, and oil & gas stock returns – Global evidence. Energy Econ. 2016, 57, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, K.; Yang, X. Response pattern of stock returns to international oil price shocks from the perspective of China’s oil industrial chain. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haykir, O.; Yagli, I.; Gok, E.D.A.; Budak, H. Oil price explosivity and stock return: Do sector and firm size matter? Resour. Policy 2022, 78, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | We also estimate the model using two period lags of change in oil prices and find evidence that energy-related prices have a significant lagged effect, which is consistent with the real options behavior [53]. To save space, we do not report the results. However, the estimated tables are available upon request. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | The variance equations were also estimated by using the asymmetric power GARCH model (APARCH) [57]. However, in this study’s empirical experiments, some models reveal negative R-squares due to an over parameterization problem although some information of the long memory can be achieved. For this reason, a TARCH model is maintained. |

| 5 | These figures were taken from the high points of each time series path but not reported. |

| 6 | The use of dummy variable to capture the impacts of GFC and COVTD-19 interruptions is required as Baker et al. [12] documented in their findings that the COVID-19 shock increased the VIX by about 500% from 15 January 2020 to 31 March 2020. |

| 7 | However, our interest is focusing on the contemporaneous period to avoid the over parametrization, but the current model contains more uncertainty variable instead of the VIX alone. Adding lagged effects on the explanatory variables are possible if we follow Dixit and Pindyck [53]. |

| Sector | Mean | Median | Maximum | Minimum | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | Jarque-Bera |

| ENGY | 0.629 | 0.688 | 28.513 | -45.502 | 6.914 | -0.760 | 9.491 | 598.2 |

| BMAT | 0.660 | 0.694 | 20.389 | -28.825 | 6.551 | -0.567 | 5.136 | 78.7 |

| CDIS | 0.787 | 1.091 | 16.608 | -17.291 | 4.908 | -0.318 | 4.252 | 26.6 |

| CSTP | 0.683 | 1.003 | 12.787 | -13.428 | 3.818 | -0.531 | 4.291 | 37.6 |

| FINA | 0.596 | 1.336 | 16.954 | -24.055 | 5.883 | -0.965 | 6.230 | 190.5 |

| HLTH | 0.773 | 1.280 | 12.821 | -13.022 | 4.079 | -0.533 | 3.573 | 19.7 |

| INDU | 0.774 | 1.261 | 15.931 | -22.608 | 5.543 | -0.567 | 4.608 | 52.1 |

| RLES | 0.668 | 1.334 | 27.404 | -36.352 | 5.967 | -1.190 | 9.920 | 720.7 |

| TECH | 0.894 | 1.535 | 19.533 | -32.333 | 7.407 | -0.676 | 4.555 | 57.1 |

| TELE | 0.398 | 1.045 | 27.492 | -17.171 | 5.650 | -0.177 | 4.714 | 41.2 |

| UTLI | 0.636 | 1.301 | 13.365 | -13.650 | 4.479 | -0.590 | 3.650 | 24.4 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

| (1) R_ENGY | 1 | ||||||||||

| ----- | |||||||||||

| (2) R_BMAT | 0.68 | 1 | |||||||||

| 16.61 | ----- | ||||||||||

| (3) R_CDIS | 0.50 | 0.74 | 1 | ||||||||

| 10.40 | 19.46 | ----- | |||||||||

| (4) R_CSTP | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 1 | |||||||

| 8.55 | 12.06 | 14.90 | ----- | ||||||||

| (5) R_FINA | 0.58 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 1 | ||||||

| 12.77 | 18.78 | 23.47 | 14.97 | ----- | |||||||

| (6) R_HLTH | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 1 | |||||

| 8.20 | 12.25 | 16.25 | 20.97 | 16.01 | ----- | ||||||

| (7) R_INDU | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.82 | 0.65 | 1 | ||||

| 14.29 | 24.47 | 28.51 | 13.22 | 25.64 | 15.37 | ----- | |||||

| (8) R_RLES | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 1 | |||

| 8.41 | 14.11 | 14.98 | 11.73 | 18.60 | 11.45 | 15.16 | ----- | ||||

| (9) R_TECH | 0.39 | 0.57 | 0.74 | 0.33 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.41 | 1 | ||

| 7.59 | 12.34 | 19.60 | 6.18 | 12.16 | 9.30 | 20.04 | 8.05 | ----- | |||

| (10) R_TELE | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 1 | |

| 7.08 | 9.83 | 13.40 | 9.43 | 10.66 | 9.37 | 13.29 | 6.95 | 12.67 | ----- | ||

| (11) R_UTLI | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 1 |

| 8.85 | 8.49 | 7.63 | 11.08 | 8.62 | 9.21 | 9.16 | 10.99 | 5.07 | 6.72 | ----- |

| EPU | EMVE | OPU | EUI | CPU | |

| EPU | 1 | ||||

| ----- | |||||

| EMVE | 0.314 | 1 | |||

| 5.10 | ----- | ||||

| OPU | -0.138 | 0.114 | 1 | ||

| -2.15 | 1.77 | ----- | |||

| EUI | 0.104 | -0.057 | -0.036 | 1 | |

| 1.61 | -0.88 | -0.56 | ----- | ||

| CPU | 0.501 | 0.122 | -0.090 | 0.123 | 1 |

| 8.93 | 1.89 | -1.40 | 1.92 | ----- |

| Sector | C | ||||||||||

| ENGY | 5.090 | -0.017 | -1.082 | -0.010 | -0.027 | -0.377 | 23.055 | 0.218 | 0.903 | 0.04 | |

| 10.96 | -6.19 | -13.87 | -6.66 | -4.16 | -3.51 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 3.42 | |||

| BMAT | 5.584 | -0.018 | -0.712 | -0.016 | -0.022 | -4.132 | 23.457 | 0.610 | 0.654 | 0.07 | |

| 11.50 | -5.73 | -2.15 | -8.58 | -3.09 | -13.30 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 1.52 | |||

| CDIS | 2.691 | -0.003 | -0.520 | -0.006 | -0.026 | -7.342 | 8.657 | 0.635 | 0.803 | 0.00 | |

| 13.58 | -1.53 | -2.16 | -11.23 | -4.11 | -33.11 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 2.10 | |||

| CSTP | 2.276 | -0.004 | -0.215 | -0.001 | -0.027 | -2.930 | 7.667 | 0.233 | 0.889 | 0.04 | |

| 21.38 | -4.28 | -1.67 | -1.70 | -43.20 | -10.54 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 1.33 | |||

| FINA | 4.466 | -0.009 | -2.106 | -0.012 | -0.021 | -0.717 | 19.501 | 1.780 | 0.794 | 0.06 | |

| 12.37 | -4.19 | -4.42 | -7.62 | -2.79 | -1.14 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 2.70 | |||

| HLTH | 2.302 | -0.002 | -1.781 | -0.003 | -0.007 | -1.354 | 9.019 | 0.216 | 0.774 | 0.03 | |

| 27.71 | -2.30 | -5.08 | -6.12 | -3.35 | -1.66 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.99 | |||

| INDU | 4.564 | -0.012 | -2.191 | -0.011 | -0.013 | -5.249 | 4.248 | 0.417 | 0.830 | 0.07 | |

| 12.03 | -5.79 | -6.02 | -6.75 | -7.88 | -2.45 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 3.84 | |||

| RLES | 4.351 | -0.005 | -3.675 | -0.003 | -0.044 | -0.165 | 3.817 | 0.231 | 0.790 | 0.03 | |

| 11.00 | -1.98 | -9.06 | -3.01 | -5.08 | -3.28 | 0.70 | 0.95 | 3.74 | |||

| TECH | 4.072 | -0.014 | -1.228 | -0.016 | 0.021 | -0.829 | 33.830 | 0.213 | 0.757 | 0.02 | |

| 8.46 | -5.93 | -2.63 | -11.42 | 3.00 | -0.70 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 1.06 | |||

| TELE | 0.652 | 0.000 | -3.094 | 0.000 | 0.024 | -1.253 | 15.891 | 1.328 | 0.797 | 0.00 | |

| 2.30 | -35.63 | -6.40 | 14.42 | 4.18 | -0.61 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 2.35 | |||

| UTIL | 2.174 | -0.005 | -0.295 | 0.004 | -0.037 | -3.781 | 32.909 | 4.474 | 0.857 | 0.05 | |

| 9.05 | -3.18 | -17.68 | 5.22 | -7.68 | -8.41 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 2.90 | |||

| Sector | C | |||||||||

| ENGY | 4.916 | -0.017 | -0.994 | -0.010 | -0.027 | -2.593 | 27.395 | 0.171 | 0.832 | 0.05 |

| 12.25 | -7.47 | -14.20 | -5.51 | -5.15 | -1.79 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 1.43 | ||

| BMAT | 5.456 | -0.018 | -0.645 | -0.016 | -0.018 | -4.321 | 29.683 | 1.004 | 0.656 | 0.07 |

| 14.10 | -7.67 | -9.28 | -10.67 | -5.96 | -1.76 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 1.38 | ||

| CDIS | 2.499 | -0.003 | -0.564 | -0.006 | -0.025 | -7.345 | 11.841 | 0.220 | 0.921 | 0.00 |

| 14.86 | -1.71 | -2.13 | -7.99 | -4.01 | -21.52 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 2.84 | ||

| CSTP | 2.089 | -0.004 | -0.250 | -0.001 | -0.028 | -2.905 | 6.889 | 0.334 | 0.857 | 0.04 |

| 55.96 | -15.95 | -2.38 | -1.98 | -11.95 | -7.44 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 1.48 | ||

| FINA | 4.283 | -0.009 | -2.064 | -0.011 | -0.020 | -0.877 | 15.697 | 1.087 | 0.706 | 0.06 |

| 12.97 | -3.91 | -3.81 | -6.96 | -5.52 | -0.47 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 2.07 | ||

| HLTH | 4.395 | -0.012 | -2.206 | -0.010 | -0.013 | -5.212 | 5.321 | 0.494 | 0.778 | 0.07 |

| 11.27 | -4.45 | -4.10 | -6.10 | -5.34 | -2.36 | 0.52 | 0.92 | 3.13 | ||

| INDU | 4.142 | -0.005 | -3.700 | -0.003 | -0.046 | -0.113 | 4.952 | 0.304 | 0.786 | 0.03 |

| 17.95 | -3.64 | -7.54 | -7.88 | -6.48 | -6.65 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 3.29 | ||

| RLES | 3.930 | -0.013 | -1.185 | -0.016 | 0.022 | -0.301 | 7.872 | 0.698 | 0.822 | 0.02 |

| 8.46 | -4.87 | -1.88 | -9.25 | 2.58 | -1.49 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 3.55 | ||

| TECH | 0.542 | -0.001 | -4.049 | 0.004 | 0.018 | -1.094 | 7.654 | 0.875 | 0.751 | 0.01 |

| 7.38 | -3.09 | -59.94 | 15.27 | 11.10 | -2.59 | 0.42 | 0.75 | 2.51 | ||

| TELE | 1.982 | -0.005 | -0.391 | 0.004 | -0.038 | -3.485 | 11.633 | 0.774 | 0.858 | 0.05 |

| 8.81 | -3.14 | -9.67 | 4.07 | -8.63 | -4.42 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 2.77 | ||

| UTIL | 4.916 | -0.017 | -0.994 | -0.010 | -0.027 | -2.593 | 27.395 | 0.171 | 0.832 | 0.05 |

| 12.25 | -7.47 | -14.20 | -5.51 | -5.15 | -1.79 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 1.43 |

| Sector | C | |||||||||

| ENGY | 5.317 | -0.017 | -1.559 | -0.010 | -0.025 | -0.370 | 21.865 | 0.207 | 0.908 | 0.05 |

| 17.55 | -6.94 | -3.27 | -5.82 | -3.76 | -3.88 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 3.77 | ||

| BMAT | 6.617 | -0.020 | -1.583 | -0.016 | -0.025 | -4.207 | 38.912 | 0.873 | 0.476 | 0.09 |

| 14.31 | -6.74 | -3.92 | -9.49 | -3.20 | -6.02 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.83 | ||

| CDIS | 3.491 | -0.005 | -1.502 | -0.006 | -0.032 | -6.936 | 10.878 | 0.312 | 0.682 | 0.03 |

| 29.87 | -2.67 | -4.32 | -5.77 | -4.63 | -10.00 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 1.00 | ||

| CSTP | 2.818 | -0.006 | -0.335 | -0.002 | -0.031 | -2.590 | 6.484 | 0.173 | 0.832 | 0.06 |

| 8.46 | -2.97 | -2.81 | -2.39 | -9.17 | -13.64 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 1.65 | ||

| FINA | 4.305 | -0.008 | -2.742 | -0.011 | -0.017 | -0.855 | 13.373 | 0.812 | 0.697 | 0.07 |

| 10.61 | -3.17 | -5.18 | -7.56 | -3.04 | -2.17 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 1.87 | ||

| HLTH | 2.696 | -0.010 | -0.005 | -1.858 | -0.007 | 0.010 | 8.374 | 0.354 | 0.782 | 0.02 |

| 9.90 | -6.17 | -4.25 | -4.92 | -2.77 | 11.69 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 1.74 | ||

| INDU | 4.675 | -0.010 | -2.660 | -0.010 | -0.022 | -5.605 | 6.070 | 0.516 | 0.741 | 0.08 |

| 17.46 | -4.09 | -5.76 | -23.91 | -5.25 | -25.04 | 0.54 | 0.85 | 2.50 | ||

| RLES | 4.371 | -0.005 | -4.051 | -0.003 | -0.044 | 2.846 | 8.546 | 0.671 | 0.815 | 0.02 |

| 117.91 | -9.88 | -43.02 | -26.97 | -18.75 | 24.14 | 0.45 | 0.73 | 3.28 | ||

| TECH | 4.000 | -0.015 | -2.124 | -0.013 | 0.007 | -2.103 | 15.845 | 1.004 | 0.644 | 0.04 |

| 8.43 | -4.27 | -4.85 | -6.46 | 4.77 | -1.07 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 1.46 | ||

| TELE | 1.452 | -0.001 | -3.150 | -0.003 | 0.011 | -1.349 | 23.088 | 1.341 | 0.799 | 0.01 |

| 5.39 | -5.61 | -8.25 | -2.06 | 3.57 | -0.67 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 1.83 | ||

| UTIL | 1.592 | -0.004 | -0.300 | 0.004 | -0.025 | -2.230 | 14.952 | 1.067 | 0.793 | 0.03 |

| 18.81 | -4.23 | -1.39 | 5.36 | -8.79 | -1.98 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 1.77 |

| Sector | C | Dumt | ||||||||||

| ENGY | 2.042 | -0.006 | -1.386 | -0.001 | -0.010 | 0.325 | -3.676 | 15.847 | 0.232 | 0.885 | 0.31 | |

| 7.66 | -2.97 | -3.10 | -3.48 | -11.65 | 35.96 | -2.39 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 1.71 | |||

| BMAT | 3.740 | -0.012 | -0.581 | -0.011 | -0.011 | 0.233 | -8.487 | 15.271 | 0.710 | 0.729 | 0.11 | |

| 32.98 | -8.19 | -2.39 | -9.02 | -2.36 | 16.65 | -8.34 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 1.95 | |||

| CDIS | 2.239 | 0.000 | -0.662 | -0.006 | -0.010 | 0.059 | -6.048 | 10.708 | 0.266 | 0.905 | 0.01 | |

| 28.38 | -5.96 | -2.28 | -19.68 | -6.25 | 18.51 | -27.90 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 2.32 | |||

| CSTP | 1.981 | -0.003 | -0.278 | 0.000 | -0.026 | 0.023 | -2.490 | 7.595 | 0.227 | 0.894 | 0.04 | |

| 13.32 | -2.00 | -2.64 | 6.47 | -10.67 | 3.42 | -4.04 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 1.15 | |||

| FINA | 4.157 | -0.008 | -2.089 | -0.011 | -0.018 | 0.035 | 2.647 | 12.737 | 0.713 | 0.730 | 0.01 | |

| 11.87 | -3.03 | -3.95 | -6.21 | -2.53 | 3.39 | 4.79 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 2.11 | |||

| HLTH | 2.116 | -0.002 | -1.784 | -0.003 | -0.007 | 0.018 | -1.833 | 9.766 | 0.306 | 0.897 | 0.03 | |

| 15.77 | -6.79 | -24.86 | -7.28 | -3.73 | 6.32 | -3.11 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 2.56 | |||

| INDU | 3.528 | -0.008 | -2.243 | -0.008 | -0.008 | 0.106 | -3.386 | 8.301 | 0.997 | 0.686 | 0.11 | |

| 14.66 | -3.91 | -4.34 | -26.50 | -11.69 | 16.85 | -1.33 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 1.97 | |||

| RLES | 4.235 | -0.005 | -3.768 | -0.004 | -0.044 | 0.005 | 0.146 | 12.196 | 0.680 | 0.812 | 0.03 | |

| 57.80 | -5.17 | -15.16 | -5.37 | -21.06 | 1.45 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 2.82 | |||

| TECH | 2.505 | -0.009 | -1.567 | -0.012 | 0.027 | 0.137 | -1.303 | 10.818 | 1.177 | 0.690 | 0.06 | |

| 6.40 | -2.94 | -2.10 | -6.28 | 4.28 | 18.19 | -0.67 | 0.44 | 0.80 | 2.05 | |||

| TELE | 0.241 | 0.001 | -2.405 | -0.001 | 0.025 | 0.032 | -1.625 | 17.915 | 1.460 | 0.754 | 0.00 | |

| 0.83 | 1.53 | -7.44 | -1.67 | 7.22 | 11.70 | -9.23 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 1.92 | |||

| UTIL | 1.868 | -0.004 | -0.379 | 0.005 | -0.036 | 0.029 | -2.985 | 10.019 | 1.207 | 0.800 | 0.05 | |

| 10.85 | -4.90 | -2.90 | 4.97 | -10.26 | 4.84 | -6.69 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 2.35 | |||

| Sector | C | |||||||||||

| ENGY | 1.775 | -0.003 | -2.135 | 0.004 | -0.019 | 0.351 | -0.847 | -0.018 | 42.687 | 17.506 | 0.912 | 0.38 |

| 10.51 | -3.16 | -5.95 | 2.92 | -8.08 | 59.10 | -5.19 | -9.29 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 2.72 | ||

| BMAT | 3.199 | -0.029 | -1.342 | -0.007 | -0.005 | 0.175 | -1.791 | 0.004 | 16.311 | 0.699 | 0.698 | 0.17 |

| 11.01 | -7.63 | -2.32 | -8.61 | -0.62 | 21.35 | -10.75 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 1.83 | ||

| CDIS | 2.497 | -0.004 | -1.771 | -0.004 | -0.015 | 0.077 | -0.952 | 0.073 | 61.107 | 2.973 | 0.099 | 0.06 |

| 14.72 | -2.27 | -7.73 | -4.95 | -4.32 | 13.72 | -10.40 | 6.17 | 1.85 | 1.11 | 0.84 | ||

| CSTP | 2.077 | -0.001 | -1.186 | 0.001 | -0.024 | 0.059 | -0.721 | -0.014 | 7.842 | 0.181 | 0.923 | 0.05 |

| 12.70 | -3.10 | -3.07 | 1.53 | -6.14 | 14.16 | -6.97 | -1.90 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 1.25 | ||

| FINA | 4.285 | -0.014 | -3.212 | -0.009 | -0.014 | 0.074 | -1.619 | -0.010 | 10.439 | 0.996 | 0.670 | 0.12 |

| 26.56 | -5.87 | -5.77 | -13.78 | -12.68 | 11.22 | -12.07 | -1.04 | 0.56 | 0.93 | 2.17 | ||

| HLTH | 2.402 | -0.007 | -2.290 | -0.002 | -0.004 | 0.034 | -0.929 | 0.024 | 9.967 | 0.271 | 0.800 | 0.05 |

| 14.48 | -5.07 | -8.19 | -2.06 | -1.17 | 4.57 | -6.34 | 1.37 | 0.24 | 0.34 | 1.12 | ||

| INDU | 3.418 | -0.009 | -2.721 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.135 | -1.532 | -0.007 | 12.076 | 1.294 | 0.672 | 0.16 |

| 18.99 | -5.62 | -5.43 | -4.39 | -3.58 | 15.65 | -15.25 | -3.57 | 0.49 | 0.91 | 1.89 | ||

| RLES | 4.285 | -0.014 | -3.212 | -0.009 | -0.014 | 0.074 | -1.619 | -0.010 | 10.439 | 0.996 | 0.670 | 0.12 |

| 26.56 | -5.87 | -5.77 | -13.78 | -12.68 | 11.22 | -12.07 | -1.04 | 0.56 | 0.93 | 2.17 | ||

| TECH | 1.644 | -0.013 | -2.091 | -0.010 | 0.045 | 0.153 | -0.254 | 0.059 | 4.615 | 0.451 | 0.745 | 0.08 |

| 3.50 | -3.39 | -2.86 | -3.51 | 3.52 | 7.47 | -1.38 | 1.86 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 3.37 | ||

| TELE | 1.489 | -0.006 | -1.784 | -0.002 | 0.021 | 0.056 | -1.331 | -0.001 | 14.321 | 0.518 | 0.656 | 0.03 |

| 5.00 | -2.42 | -2.89 | -2.32 | 2.30 | 3.96 | -5.36 | -0.08 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 1.45 | ||

| UTIL | 2.251 | -0.001 | -1.150 | 0.005 | -0.030 | 0.048 | -1.482 | -0.030 | 7.406 | 0.976 | 0.795 | 0.05 |

| 9.48 | -1.99 | -3.06 | 5.10 | -6.74 | 6.16 | -8.85 | -2.97 | 0.35 | 0.63 | 2.46 |

| Sector | C | D-2008 | D-2020 | ||||||||||||

| ENGY | 1.263 | -0.004 | -0.003 | -2.450 | 0.002 | -0.010 | 0.373 | -4.519 | -8.436 | 19.987 | 0.279 | 0.871 | 0.37 | ||

| 7.47 | -5.19 | -17.03 | -19.71 | 1.78 | -6.76 | 41.23 | -2.84 | -9.86 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 2.26 | ||||

| BMAT | 2.521 | -0.009 | -0.002 | -1.878 | -0.008 | -0.010 | 0.206 | -8.720 | -1.454 | 18.289 | 0.705 | 0.709 | 0.16 | ||

| 12.51 | -6.77 | -10.79 | -5.84 | -6.15 | -5.95 | 16.30 | -11.38 | -1.84 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 1.70 | ||||

| CDIS | 2.024 | -0.004 | -0.001 | -1.315 | -0.004 | -0.017 | 0.077 | -7.235 | -7.726 | 13.609 | 0.258 | 0.896 | 0.04 | ||

| 19.53 | -4.58 | -9.93 | -4.46 | -8.28 | -7.50 | 9.96 | -11.62 | -5.28 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 2.21 | ||||

| CSTP | 1.608 | -0.003 | -0.001 | -0.600 | 0.002 | -0.025 | 0.049 | -3.524 | -4.450 | 8.022 | 0.243 | 0.889 | 0.07 | ||

| 21.40 | -8.75 | -9.52 | -3.04 | 9.30 | -8.42 | 6.37 | -8.39 | -2.06 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 1.22 | ||||

| FINA | 3.103 | -0.013 | -0.001 | -2.487 | -0.009 | -0.021 | 0.080 | -0.654 | -9.316 | .440 | 0.824 | 0.691 | 0.11 | ||

| 11.82 | -7.73 | -2.70 | -5.23 | -5.15 | -3.87 | 7.65 | -0.32 | -6.66 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 2.03 | ||||

| HLTH | 1.883 | -0.007 | -0.001 | -2.209 | -0.002 | -0.005 | 0.041 | -2.331 | -0.850 | 10.037 | 0.222 | 0.913 | 0.05 | ||

| 23.19 | -5.87 | -8.23 | -11.51 | -5.23 | -2.08 | 9.82 | -14.88 | -3.32 | 0.22 | 0 .23 | 3.02 | ||||

| INDU | 2.455 | -0.012 | -0.001 | -2.821 | -0.006 | -0.005 | 0.142 | -4.888 | -7.223 | 10.452 | 0.705 | 0.716 | 0.15 | ||

| 17.72 | -8.52 | -11.82 | -5.66 | -6.86 | -7.56 | 12.08 | -2.06 | -8.02 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 1.92 | ||||

| RLES | 3.292 | -0.005 | 0.001 | -3.956 | -0.001 | -0.038 | 0.057 | -0.441 | -4.192 | 11.591 | 0.820 | 0.717 | 0.05 | ||

| 19.35 | -2.31 | 2.21 | -8.61 | -0.85 | -6.04 | 5.07 | -0.14 | -4.23 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 2.14 | ||||

| TECH | 1.708 | -0.017 | -0.001 | -1.773 | -0.010 | 0.035 | 0.143 | -3.865 | 2.198 | 11.127 | 1.061 | 0.708 | 0.06 | ||

| 6.07 | -7.39 | -7.93 | -3.30 | -5.38 | 4.49 | 9.06 | -4.91 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.84 | 2.25 | ||||

| TELE | 0.666 | -0.006 | -0.001 | -2.093 | -0.003 | 0.023 | 0.060 | -1.869 | -2.354 | 20.258 | 1.824 | 0.726 | 0.02 | ||

| 3.47 | -8.69 | -4.64 | -5.35 | -3.48 | 3.98 | 5.17 | -7.48 | -1.27 | 0.38 | 0.57 | 1.79 | ||||

| UTIL | 1.187 | -0.002 | -10.001 | -0.790 | 0.007 | -0.032 | 0.043 | -2.513 | -5.891 | 11.945 | 0.557 | 0.858 | 0.06 | ||

| 14.78 | -9.79 | -2.12 | -2.73 | 6.99 | -16.62 | 20.28 | -2.91 | -3.02 | 0.30 | 0.45 | 2.46 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).