Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Plots Selection

2.2. Sample Collection and Statement

2.3. Chemical Assay, Calculation, Data Analyses and Figure Drawing

3. Results

3.1. Soil C, N, and P Concentrations and Variability

3.2. Stoichiometry Ratios of Soil C, N and P

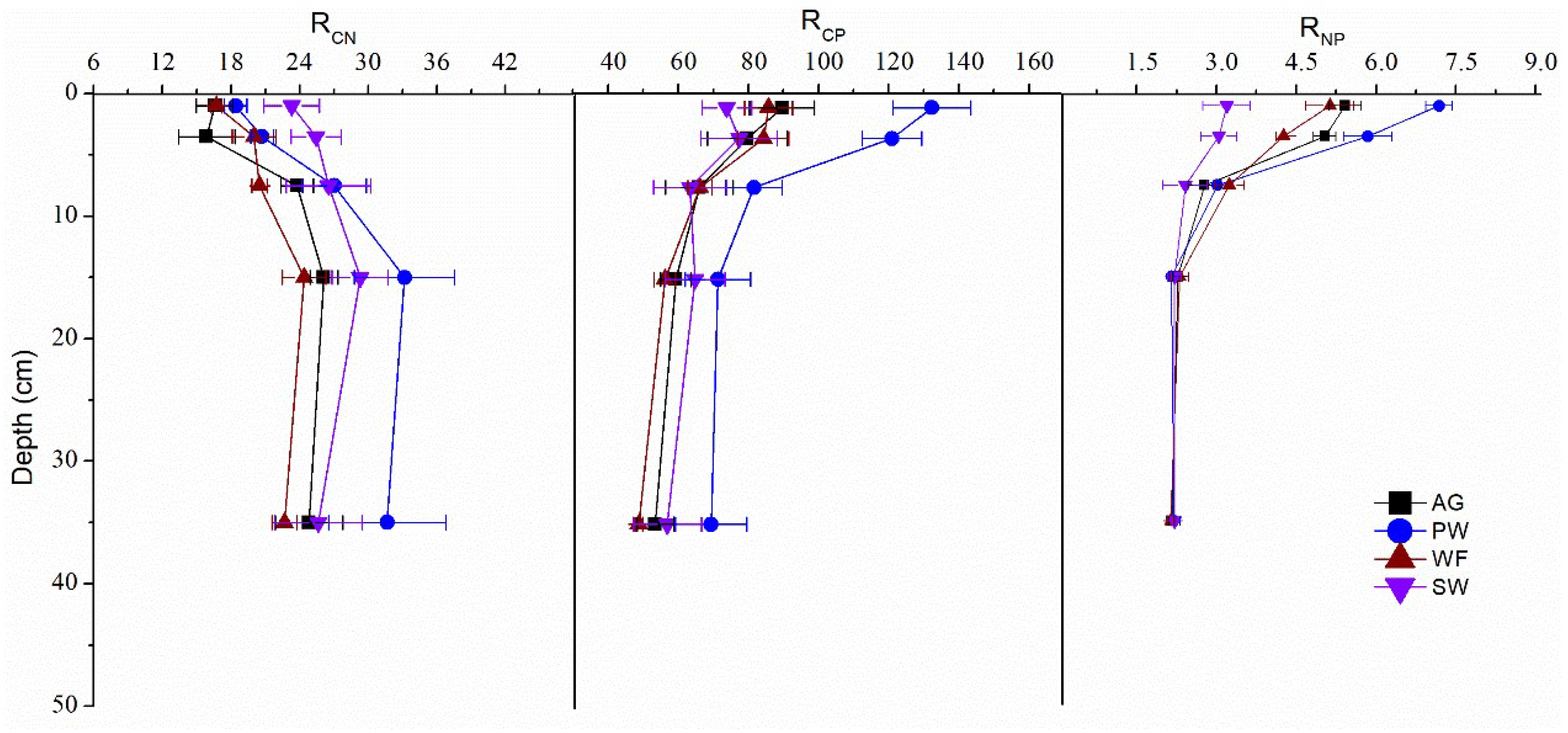

3.3. Profile Distribution of Soil C, N and P Concentrations and Ratios

4. Discussion

4.1. The Transition and the Influence of China’s Land Use Policy

4.2. Wetland Restoration Policies Effects on Coastal Wetland Soil

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YNR | The Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve |

| YRD | The Yellow River Delta |

| AG | Ash grove |

| PW | Permanent wetland |

| WF | Wheat field |

| SW | Seasonal wetland |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Plots | Parameters | 0-2 cm | 0-5 cm | 5-10 cm | 10-20 cm | 20-50 cm |

| AG | C | 24.16 a | 20.98 ab | 16.54 bc | 14.54 c | 13.19 c |

| N | 1701.74 a | 1540.48 b | 809.84 c | 648.35 d | 620.00 d | |

| P | 695.19 a | 676.51 ab | 645.75 bc | 631.31 c | 635.11 c | |

| RCN | 16.55 b | 15.86 b | 23.77 a | 26.13 a | 24.82 a | |

| RCP | 89.56 a | 79.70 ab | 66.03 bc | 59.35 c | 53.49 c | |

| RNP | 5.42 a | 5.04 a | 2.77 b | 2.27 c | 2.16 c | |

| PW | C | 37.71 a | 33.72 a | 21.35 b | 18.23 b | 16.61 b |

| N | 2388.48 a | 1901.64 b | 920.26 c | 641.83 d | 612.66 d | |

| P | 735.19 a | 719.04 a | 673.91 b | 659.745 b | 617.12 c | |

| RCN | 18.40 b | 20.71 b | 27.02 a | 33.16 a | 31.65 a | |

| RCP | 132.29 a | 120.93 a | 81.57 b | 71.34 b | 69.39 b | |

| RNP | 7.18 a | 5.85 b | 3.02 c | 2.15 d | 2.20 d | |

| WF | C | 24.24 a | 23.37 a | 18.07 b | 14.44 c | 12.22 c |

| N | 1693.51 a | 1381.25 b | 1034.29 c | 690.64 d | 626.91 d | |

| P | 730.33 a | 715.31 a | 705.31 ab | 662.31 bc | 646.21 c | |

| RCN | 16.71 b | 20.01 ab | 20.49 ab | 24.41 a | 22.68 a | |

| RCP | 85.74 a | 84.31 a | 66.16 b | 56.18 bc | 48.74 c | |

| RNP | 5.13 a | 4.26 b | 3.24 c | 2.31 d | 2.14 d | |

| SW | C | 20.65 a | 21.03 a | 16.65 b | 16.15 b | 13.87 b |

| N | 1041.29 a | 965.75 a | 738.34 b | 642.42 b | 629.64 b | |

| P | 722.53 a | 702.59 ab | 678.26 bc | 643.82 cd | 628.68 d | |

| RCN | 23.30 b | 25.43 ab | 26.52 ab | 29.28 a | 25.64 ab | |

| RCP | 73.84 ab | 77.37 a | 63.40 ab | 64.82 ab | 56.91 b | |

| RNP | 3.19 a | 3.04 a | 2.41 b | 2.21 b | 2.22 b |

References

- Navarro, N.; Rodríguez-Santalla, I. Coastal Wetlands. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowardin, L.M.; Carter, V.; Golet, F.C.; LaRoe, E.T. Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.D.o.t.I., Ed. Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of the Interior.: Washington, D.C., 1979; p 131.

- Meng, L.; Qu, F.; Bi, X.; Xia, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Elemental stoichiometry (C, N, P) of soil in the Yellow River Delta nature reserve: Understanding N and P status of soil in the coastal estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S.Hopkinson, C.; Wolanski, E.; Cahoon, D.R.; Perillo, G.M.E.; Brinson, M.M. Coastal Wetlands: A Synthesis. In Coastal Wetlands: An Integrated Ecosystem Approach, Second Edition ed.; Perillo, G.M.E., Wolanski, E., Cahoon, D.R., Brinson, M.M., Eds. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2019; pp 1-75.

- Finlayson, C.M.; Milton, G.R.; Prentice, R.C. Wetland types and distribution. In Finlayson, C.M., Milton, G.R., & Prentice, R.C. (2018). . in: Finlayson, C. Max, Milton, G. Randy, Prentice, R. Crawford and Davidson, Nick C. (ed.) The Wetland Book II: Distribution, Description and Conservation, Finlayson, C.M., Milton, G.R., Prentice, R.C., Davidson, N.C., Eds. Springer Netherlands: 2018.

- Moffett, K.B.; Nardin, W.; Silvestri, S.; Wang, C.; Temmerman, S. Multiple Stable States and Catastrophic Shifts in Coastal Wetlands: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities in Validating Theory Using Remote Sensing and Other Methods. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 10184–10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moomaw, W.R.; Chmura, G.L.; Davies, G.T.; Finlayson, C.M.; Middleton, B.A.; Natali, S.M.; Perry, J.E.; Roulet, N.; Sutton-Grier, A.E. Wetlands In a Changing Climate: Science, Policy and Management. Wetlands 2018, 38, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerch, M.; Spencer, T.; Temmerman, S.; Kirwan, M.L.; Wolff, C.; Lincke, D.; McOwen, C.J.; Pickering, M.D.; Reef, R.; Vafeidis, A.T. , et al. Future response of global coastal wetlands to sea-level rise. Nature 2018, 561, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, E.; Acreman, M.C. Ecosystem services of wetlands: pathfinder for a new paradigm. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 1341–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratolongo, P.; Leonardi, N.; Kirby, J.R.; Plater, A. Temperate coastal wetlands: morphology, sediment processes, and plant communities. In Coastal Wetlands: An Integrated Ecosystem Approach, Second Edition ed.; Perillo, G.M.E., Wolanski, E., Cahoon, D.R., Brinson, M.M., Eds. Amsterdam, 2019; pp 105-152.

- Kirwan, M.L.; Megonigal, J.P. Tidal wetland stability in the face of human impacts and sea-level rise. Nature 2013, 504, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, D.T.; Call, M.; Santos, I.R.; Sanders, C.J. Beyond burial: lateral exchange is a significant atmospheric carbon sink in mangrove forests. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20180200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourqurean, J.W.; Duarte, C.M.; Kennedy, H.; Marbà, N.; Holmer, M.; Mateo, M.A.; Apostolaki, E.T.; Kendrick, G.A.; Krause-Jensen, D.; McGlathery, K.J., et al. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 505-509. [CrossRef]

- Chmura, G.L.; Anisfeld, S.C.; Cahoon, D.R.; Lynch, J.C. Global carbon sequestration in tidal, saline wetland soils. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 2003, 17, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Groot, R.d.; Sutton, P.; Ploeg, S.v.d.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lu, X.; Sanders, C.J.; Tang, J. Tidal wetland resilience to sea level rise increases their carbon sequestration capacity in United States. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I.; Costa, M.D.P.; Atwood, T.B.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Lovelock, C.E.; Serrano, O.; Duarte, C.M. Blue carbon as a natural climate solution. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2021, 2, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.T.; Bradley, P.M. Effects of nutrient loading on the carbon balance of coastal wetland sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1999, 44, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Rivas-ubach, A.; Janssens, I.A. The human-induced imbalance between C, N and P in Earth’s life system. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2012, 18, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundareshwar, P.V.; Morris, J.T.; Koepfler, E.K.; Fornwalt, B. Phosphorus Limitation of Coastal Ecosystem Processes. Science 2003, 299, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitali, R.; Snoussi, M.; Kolker, A.S.; Oujidi, B.; Mhammdi, N. Effects of Land Use/Land Cover Changes on Carbon Storage in North African Coastal Wetlands. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.C. How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2014, 65, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckbert, S.; Costanza, R.; Poloczanska, E.; Richardson, A. Climate Regulation as a Service from Estuarine and Coastal Ecosystems. In Treatise on Estuarine and Coastal Science, 2011.

- Oppenheimer, M.; Glavovic, B.C.; Hinkel, J.; Wal, R.v.d.; Magnan, A.K.; Abd-Elgawad, A.; Cai, R.; Cifuentes-Jara, M.; DeConto, R.M.; Ghosh, T., et al. Sea level rise and implications for low-lying islands, coasts and communities; Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp 321-445.

- Foster, T.E.; Stolen, E.D.; Hall, C.R.; Schaub, R.; Duncan, B.W.; Hunt, D.K.; Drese, J.H. Modeling vegetation community responses to sea-level rise on Barrier Island systems: A case study on the Cape Canaveral Barrier Island complex, Florida, USA. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0182605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asselen, S.v.; Verburg, P.H.; Vermaat, J.E.; Janse, J.H. Drivers of Wetland Conversion: a Global Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaroufi, N.I.; Nordin, A.; Hasselquist, N.J.; Bach, L.H.; Palmqvist, K.; Gundale, M.J. Anthropogenic nitrogen deposition enhances carbon sequestration in boreal soils. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 3169–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.A.; Mendelssohn, I.A.; Silliman, B. Contrasting effects of nutrient enrichment on below-ground biomass in coastal wetlands. J. Ecol. 2015, 104, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, A.; Icely, J.; Cristina, S.; Perillo, G.M.E.; Turner, R.E.; Ashan, D.; Cragg, S.; Luo, Y.; Tu, C.; Li, Y., et al. Anthropogenic, Direct Pressures on Coastal Wetlands. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.M.; Huh, O.K.; Braud, D. Wetland Loss in World Deltas. J. Coastal Res. 2008, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Niu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, H. Global wetlands: Potential distribution, wetland loss, and status. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Yu, J.; Guan, B.; Li, Y.; Yu, M.; Qu, F.; Zhan, C.; Lv, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, Q., et al. A Comparison of the Development of Wetland Restoration Techniques in China and Other Nations. Wetlands 2020, 40, 2755-2764. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Melville, D.S.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Ren, W.; Zhang, Z.; Piersma, T.; Li, B. Rethinking China’s new great wall: Massive seawall construction in coastal wetlands threatens biodiversity. Science 2014, 346, 912–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, J.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Assessment of Blue Carbon Storage Loss in Coastal Wetlands under Rapid Reclamation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Yu, J.; Du, S.; Li, Y.; Lv, X.; Ning, K.; Wu, H.; Meng, L. Influences of anthropogenic cultivation on C, N and P stoichiometry of reed-dominated coastal wetlands in the Yellow River Delta. Geoderma 2014, 235-236, 227-232. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Sun, T.; Yang, Z. Effect of activities associated with coastal reclamation on the macrobenthos community in coastal wetlands of the Yellow River Delta, China: a literature review and systematic assessment. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 129, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Meng, L.; Xia, J.; Huang, H.; Zhan, C.; Li, Y. Soil phosphorus fractions and distributions in estuarine wetlands with different climax vegetation covers in the Yellow River Delta. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, G.; Deng, W.; Hu, Y.; Hu, W. Influence of hydrology process on wetland landscape pattern: A case study in the Yellow River Delta. Ecol. Eng. 2009, 35, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Hu, X.M.; Lu, Z.H. Soil C, N and P Stoichiometry of Shrub Communities in Chenier Wetlands in Yellow River Delta, China. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 5457–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020—Key findings; Rome, 2020.

- Chen, C.; Park, T.; Wang, X.; Piao, S.; Xu, B.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Fuchs, R.; Brovkin, V.; Ciais, P.; Fensholt, R., et al. China and India lead in greening of the world through land-use management. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 122-129. [CrossRef]

- Trumbore, S.; Brando, P.; Hartmann, H. Forest health and global change. Science 2015, 349, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C.; Tyukavina, A.; Zalles, V.; Khan, A.; Song, X.-P.; Pickens, A.; Shen, Q.; Cortez, J. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 2021, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Yao, W.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, H.; Li, N.; Huang, H.; Li, C., et al. Mapping wetland changes in China between 1978 and 2008. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 2813-2823. [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Barragán-Paladines, M.J.; Franz, N. The Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Vol. 14, pp. 850.

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Z.; Kang, X. Approaches to Enhance Wetland Carbon Sink in China. Natural Protected Areas 2022, 2, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Coastal Saline Soil Rehabilitation and Utilization Based on Forestry Approaches in China. Springer: 2014.

- Donato, D.C.; Kauffman, J.B.; Murdiyarso, D.; Kurnianto, S.; Stidham, M.; Kanninen, M. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. China makes progress on wetlands preservation. China Daily 2021.

- Hou, L. Environmental protection makes China’s wetland areas flourish. China Daily 2022.

- Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Ma, Z.-W.; Li, L.-H. Soil nutrient contents and stoichiometry as affected by land-use in an agro-pastoral region of northwest China. CATENA 2017, 150, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burst, M.; Chauchard, S.; Dambrine, E.; Dupouey, J.-L.; Amiaud, B. Distribution of soil properties along forest-grassland interfaces: Influence of permanent environmental factors or land-use after-effects? Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 289, 106739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, D.; Morante-Filho, J.C.; Baumgarten, J.; Bovendorp, R.S.; Cazetta, E.; Gaiotto, F.A.; Mariano-Neto, E.; Mielke, M.S.; Pessoa, M.S.; Rocha-Santos, L., et al. The breakdown of ecosystem functionality driven by deforestation in a global biodiversity hotspot. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 283, 110126. [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Zhai, J.; Zhao, G.; Mu, X. Dynamics of runoff and suspended sediment transport in a highly erodible catchment on the chinese Loess Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plots | Parameters | Min | Max | Mean | Std | c.v. |

| AG (n=25) | C (g kg-1) | 11.54 | 27.87 | 14.71 b | 4.76 | 0.32 |

| N (mg kg-1) | 611.58 | 1801.36 | 743.16 ab | 475.64 | 0.64 | |

| P (mg kg-1) | 608.17 | 707.00 | 640.30 b | 30.79 | 0.05 | |

| RCN | 11.90 | 29.26 | 24.11 b | 4.80 | 0.20 | |

| RCP | 48.74 | 101.90 | 58.93 b | 15.55 | 0.26 | |

| RNP | 2.10 | 5.69 | 2.55 a | 1.45 | 0.57 | |

| PW (n=25) | C (g kg-1) | 14.67 | 42.28 | 19.28 a | 9.04 | 0.47 |

| N (mg kg-1) | 604.84 | 2481.78 | 797.62 a | 738.76 | 0.93 | |

| P (mg kg-1) | 583.00 | 746.33 | 642.16 ab | 45.70 | 0.07 | |

| RCN | 17.65 | 40.49 | 30.30 a | 6.68 | 0.22 | |

| RCP | 61.50 | 150.34 | 76.61 a | 28.22 | 0.37 | |

| RNP | 2.07 | 7.47 | 2.69 a | 2.11 | 0.78 | |

| WF (n=25) | C (g kg-1) | 10.75 | 26.62 | 14.40 b | 5.15 | 0.36 |

| N (mg kg-1) | 609.31 | 1892.44 | 768.32 ab | 429.06 | 0.56 | |

| P (mg kg-1) | 632.83 | 797.00 | 662.85 a | 40.18 | 0.06 | |

| RCN | 16.28 | 25.51 | 22.41 b | 3.75 | 0.17 | |

| RCP | 43.78 | 94.02 | 55.58 b | 16.62 | 0.30 | |

| RNP | 2.05 | 5.44 | 2.53 ab | 1.21 | 0.48 | |

| SW (n=25) | C (g kg-1) | 12.69 | 25.31 | 15.30 b | 3.42 | 0.22 |

| N (mg kg-1) | 578.57 | 1208.27 | 679.69 b | 189.88 | 0.28 | |

| P (mg kg-1) | 616.17 | 768.65 | 644.86 ab | 39.99 | 0.06 | |

| RCN | 21.33 | 32.99 | 26.35 a | 3.37 | 0.13 | |

| RCP | 51.64 | 96.68 | 61.05 b | 11.44 | 0.19 | |

| RNP | 1.87 | 3.89 | 2.32 b | 0.52 | 0.22 |

| Plots | Parameters | 0-2 cm | 0-5 cm | 5-10 cm | 10-20 cm | 20-50 cm |

| AG | C | 24.16 a | 20.98 a | 16.54 b | 14.54 b | 13.19 b |

| N | 1701.74 a | 1540.48 b | 809.84 c | 648.35 d | 620.00 d | |

| P | 695.19 a | 676.51 a | 645.75 b | 631.31 b | 635.11 b | |

| RCN | 16.55 b | 15.86 b | 23.77 a | 26.13 a | 24.82 a | |

| RCP | 89.56 a | 79.70 a | 66.03 b | 59.35 bc | 53.49 c | |

| RNP | 5.42 a | 5.04 b | 2.77 c | 2.27 d | 2.16 d | |

| PW | C | 37.71 a | 33.72 b | 21.35 c | 18.23 cd | 16.61 d |

| N | 2388.48 a | 1901.64 b | 920.26 c | 641.83 d | 612.66 d | |

| P | 735.19 a | 719.04 a | 673.91 b | 659.745 b | 617.12 c | |

| RCN | 18.40 c | 20.71 c | 27.02 b | 33.16 a | 31.65 a | |

| RCP | 132.29 a | 120.93 a | 81.57 b | 71.34 b | 69.39 b | |

| RNP | 7.18 a | 5.85 b | 3.02 c | 2.15 d | 2.20 d | |

| WF | C | 24.24 a | 23.37 a | 18.07 b | 14.44 c | 12.22 c |

| N | 1693.51 a | 1381.25 b | 1034.29 c | 690.64 d | 626.91 d | |

| P | 730.33 a | 715.31 a | 705.31 a | 662.31 b | 646.21 b | |

| RCN | 16.71 c | 20.01 bc | 20.49 abc | 24.41 a | 22.68 ab | |

| RCP | 85.74 a | 84.31 a | 66.16 b | 56.18 bc | 48.74 c | |

| RNP | 5.13 a | 4.26 b | 3.24 c | 2.31 d | 2.14 d | |

| SW | C | 20.65 a | 21.03 a | 16.65 b | 16.15 b | 13.87 b |

| N | 1041.29 a | 965.75 a | 738.34 b | 642.42 b | 629.64 b | |

| P | 722.53 a | 702.59 ab | 678.26 b | 643.82 c | 628.68 c | |

| RCN | 23.30 b | 25.43 ab | 26.52 ab | 29.28 a | 25.64 ab | |

| RCP | 73.84 ab | 77.37 a | 63.40 bc | 64.82 abc | 56.91 c | |

| RNP | 3.19 a | 3.04 a | 2.41 b | 2.21 b | 2.22 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).