Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

10 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Animals and Experimental Protocols

2.3. Cell Culture and Treatments

2.4. Cardiac Injury-Associated Enzymes

2.5. Histopathological Study

2.6. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick end Labeling (TUNEL)

2.7. DHE

2.8. LDH Assay

2.9. Cell Viability Assay

2.10. Flow Cytometry Assay_Annexin-V/PI Assay for Apoptosis

2.11. Western Blot Analysis

2.12. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

2.13. RNA Extraction and RNA Sequencing Analysis

2.14. Docking Analysis

2.15. RNA Knockdown

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isorhamnetin Ameliorates ISO-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction in a Rat Model

3.1.1. Evaluating Cardiac Function via Echocardiography

3.1.2. Isorhamnetin Alleviates ISO-Induced Myocardial Histopathological Damage and Myocardial Fibrosis in Rats

3.2. Isorhamnetin Reduces ISO-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Rats

3.2.1. Isorhamnetin Alleviates ISO-Induced Myocardial Apoptosis in Rats

3.2.2. Isorhamnetin Alleviates ISO-Induced Myocardial Oxidative Stress in Rats

3.3. Isorhamnetin Increases Cell Viability and Alleviates Myocardial Injury in ISO-Injured H9c2 Cells

3.4. Isorhamnetin Reduces ISO-Induced Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress In Vitro

3.4.1. Isorhamnetin Alleviates ISO-Induced Myocardial Oxidative Stress in Rats

3.4.2. Isorhamnetin Reduces ISO-Induced Oxidative Stress In Vitro

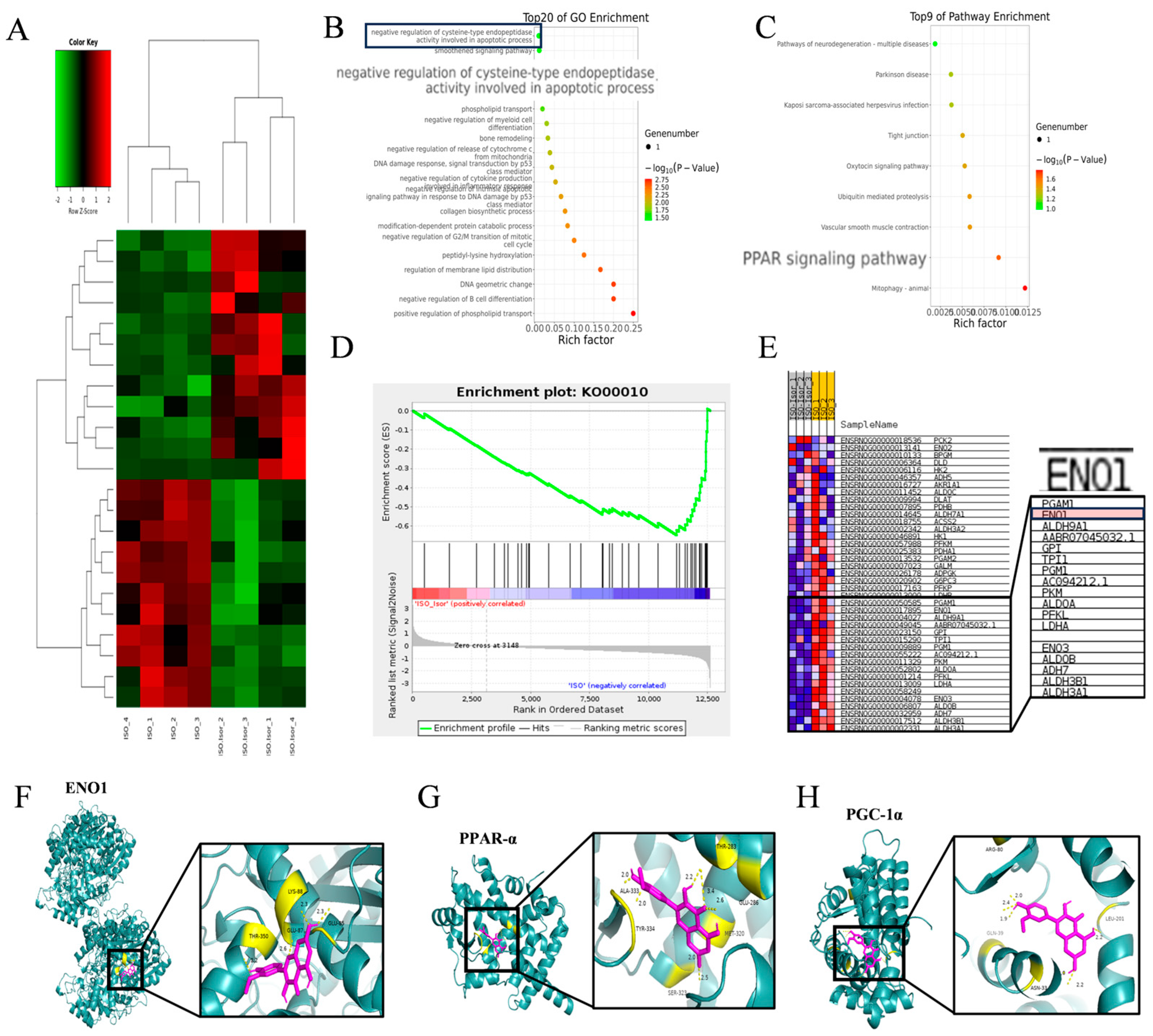

3.5. Transcriptome Sequencing Enrichment Reveals the Inhibition of the Glycolytic Pathway After Isorhamnetin Treatment, with ENO1 as a Key Target

3.6. Transcriptome Sequencing Enrichment Reveals the Inhibition of the Glycolytic Pathway After Isorhamnetin Treatment, with ENO1 as a Key Target

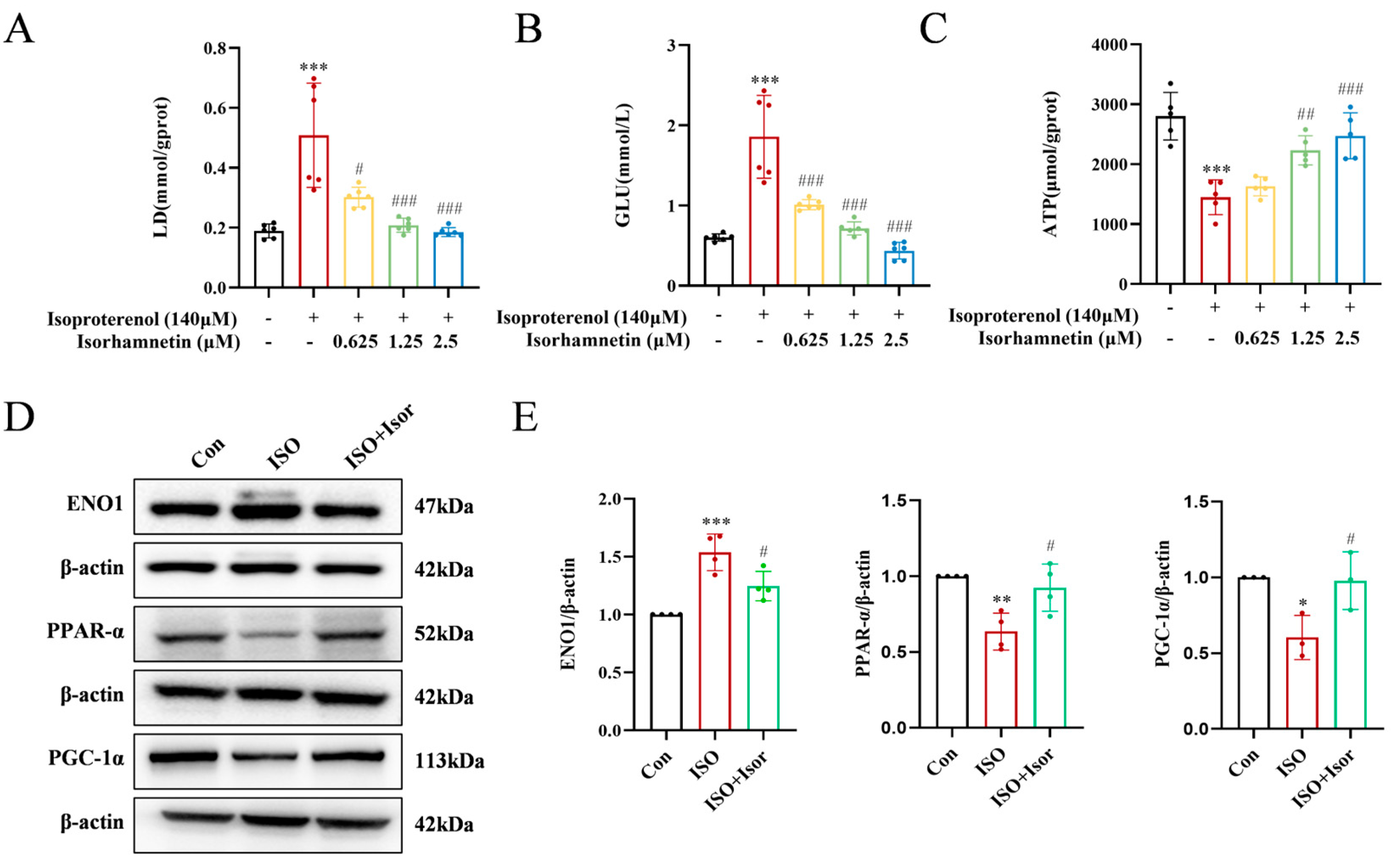

3.7. Isorhamnetin Exerts Cardioprotective Effects by Inhibiting ENO1, Activating the PPARα/PGC-1α Signaling Axis, Reversing Isoprenaline-Induced Conversion of H9c2 Energy Metabolism Substrate Levels, Inhibiting Glycolysis, and Increasing ATP Release, Thereby Attenuating Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISO | Isoproterenol |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| ENO1 | Recombinant Enolase 1 |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| PGC-1 | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1 |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| EF | Ejection Fraction |

| FS | Fractional Shortening |

| CK-MB | Creatine Kinase-MB |

| DHE | Dihydroethidium |

| Nrf2 | NF-E2-related factor 2 |

| HO-1 | Heme Oxygenase 1 |

| NQO1 | Recombinant NADH Dehydrogenase, Quinone 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| GSH-PX | Glutathione peroxidase |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

References

- Roth, G. A., Mensah, G. A., Johnson, C. O., Addolorato, G., Ammirati, E., Baddour, L. M., Barengo, N. C., Beaton, A. Z., Benjamin, E. J., Benziger, C. P., Bonny, A., Brauer, M., Brodmann, M., Cahill, T. J., Carapetis, J., Catapano, A. L., Chugh, S. S., Cooper, L. T., Coresh, J., Criqui, M., … GBD-NHLBI-JACC Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases Writing Group (2020). Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 76(25), 2982–3021.

- Lindstrom, M.; DeCleene, N.; Dorsey, H.; Fuster, V.; Johnson, C.O.; LeGrand, K.E.; Mensah, G.A.; Razo, C.; Stark, B.; Turco, J.V.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaboration, 1990-2021. Circ. 2022, 80, 2372–2425. [CrossRef]

- Nichtova, Z.; Novotova, M.; Kralova, E.; Stankovicova, T. Morphological and functional characteristics of models of experimental myocardial injury induced by isoproterenol. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2012, 31, 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Ghosh, A.K.; Dutta, M.; Mitra, E.; Mallick, S.; Saha, B.; Reiter, R.J.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Mechanisms of isoproterenol-induced cardiac mitochondrial damage: protective actions of melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 58, 275–290. [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Xie, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Lin, C.; Wang, G.; Liu, B.; Zhu, L. Main active components of Si-Miao-Yong-An decoction (SMYAD) attenuate autophagy and apoptosis via the PDE5A-AKT and TLR4-NOX4 pathways in isoproterenol (ISO)-induced heart failure models. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 176, 106077. [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.-F.; Liang, S.-Q.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Xu, J.-C.; Luo, W.; Huang, W.-J.; Wu, G.-J.; Liang, G. Isoproterenol induces MD2 activation by β-AR-cAMP-PKA-ROS signalling axis in cardiomyocytes and macrophages drives inflammatory heart failure. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 45, 531–544. [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, A., van Gilst, W. H., Voors, A. A., & van der Meer, P. (2019). Treating oxidative stress in heart failure: past, present and future. European journal of heart failure, 21(4), 425–435.

- Li, P.; Luo, S.; Pan, C.; Cheng, X. Modulation of fatty acid metabolism is involved in the alleviation of isoproterenol-induced rat heart failure by fenofibrate. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 7899–7906. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qin, Y.-H.; Zhu, L.; Zhao, X.-X.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Luo, S.-W.; Tang, G.-S.; Shen, Q. Cardiac troponin I autoantibody induces myocardial dysfunction by PTEN signaling activation. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 329–340. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, J.; Xie, R.; Fan, J.; Dai, B.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, D.W.; et al. Fibroblast-localized lncRNA CFIRL promotes cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 1155–1169. [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.-J.; Qian, L.-L.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, J.-Q.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.-W.; Yao, Y.-Y.; Ma, G.-S. Kallistatin/Serpina3c inhibits cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction by regulating glycolysis via Nr4a1 activation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166441. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Shahid, I.; Greene, S.J.; Mentz, R.J.; DeVore, A.D.; Butler, J. Mechanisms of current therapeutic strategies for heart failure: more questions than answers?. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 3467–3481. [CrossRef]

- Boateng I. D. (2023). Ginkgols and bilobols in Ginkgo biloba L. A review of their extraction and bioactivities. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 37(8), 3211–3223.

- Liu, Y.; Xin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Che, F.; Shen, N.; Cui, Y. Leaves, seeds and exocarp of Ginkgo biloba L. (Ginkgoaceae): A Comprehensive Review of Traditional Uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, resource utilization and toxicity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 298, 115645. [CrossRef]

- Gong, G., Guan, Y. Y., Zhang, Z. L., Rahman, K., Wang, S. J., Zhou, S., Luan, X., & Zhang, H. (2020). Isorhamnetin: A review of pharmacological effects. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 128, 110301.

- Sun, J.; Sun, G.; Meng, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Qin, M.; Ma, B.; Wang, M.; Cai, D.; Guo, P.; et al. Isorhamnetin Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity In Vivo and In Vitro. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e64526. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.-T.; Yang, T.-L.; Gong, L.; Wu, P. Isorhamnetin protects against hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced injure by attenuating apoptosis and oxidative stress in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Gene 2018, 666, 92–99. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-R.; Zheng, X.-M.; Liu, Y.; Tian, J.-H.; Kou, J.-J.; Shi, J.-Z.; Pang, X.-B.; Xie, X.-M.; Yan, Y. L-Carnitine Alleviates the Myocardial Infarction and Left Ventricular Remodeling through Bax/Bcl-2 Signal Pathway. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 2022, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, H.; Zou, H.; Liang, L.; Wu, X. Isorhamnetin prevents H2O2-induced oxidative stress in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 17, 648–652. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, M.; Qian, J.; Yu, T.; Lou, S.; Luo, W.; Zhou, H.; et al. JOSD2 mediates isoprenaline-induced heart failure by deubiquitinating CaMKIIδ in cardiomyocytes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Deglin, S. M., Deglin, J. M., & Chung, E. K. (1977). Drug-induced cardiovascular diseases. Drugs, 14(1), 29–40.

- Oliver, E.; Mayor, F., Jr.; D’Ocon, P. Beta-blockers: Historical Perspective and Mechanisms of Action. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019, 72, 853–862. [CrossRef]

- Pundir, S.; Garg, P.; Dviwedi, A.; Ali, A.; Kapoor, V.; Kapoor, D.; Kulshrestha, S.; Lal, U.R.; Negi, P. Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and dermatological effects of Hippophae rhamnoides L.: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 266, 113434. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-L.; Zhu, G.-L.; Wang, J.-A.; Zhang, G.-D.; Liu, H.-F.; Chen, J.-R.; Wang, Y.; He, X.-L. Protective effects of isorhamnetin on apoptosis and inflammation in TNF-α-induced HUVECs injury. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2015, 8, 2311–20.

- Xu, Y.; Tang, C.; Tan, S.; Duan, J.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y. Cardioprotective effect of isorhamnetin against myocardial ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury in isolated rat heart through attenuation of apoptosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 6253–6262. [CrossRef]

- Arden, N.; Betenbaugh, M.J. Life and death in mammalian cell culture: strategies for apoptosis inhibition. Trends Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ye, D.; Wang, Y. Caspase-3 as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2013, 17, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Pradelli, L.A.; Bénéteau, M.; Ricci, J.-E. Mitochondrial control of caspase-dependent and -independent cell death. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 1589–1597. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chai, F.; Liu, X.; Berk, M. The effects of escitalopram on myocardial apoptosis and the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion in a model of rats with depression. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Shao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; et al. Tanshinone IIA protects against heart failure post-myocardial infarction via AMPKs/mTOR-dependent autophagy pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108599. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, S.; Lin, M.; Long, J.; Yao, J.; Lin, Y.; Yi, F.; et al. Targeting oxidative stress as a preventive and therapeutic approach for cardiovascular disease. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X., Yang, S., & Yin, J. (2019). Blocking the REDD1/TXNIP axis ameliorates LPS-induced vascular endothelial cell injury through repressing oxidative stress and apoptosis. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 316(1), C104–C110.

- Senoner, T.; Dichtl, W. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Still a Therapeutic Target? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2090. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, N.; Bian, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, C. Salvianolic acid B promotes angiogenesis and inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis by regulating autophagy in myocardial ischemia. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Ghorbani, A.; Alavi, M.S.; Forouhi, N.; Rajabian, A.; Boroumand-Noughabi, S.; Sahebkar, A.; Eid, A.H. Cardioprotective effect of Sanguisorba minor against isoprenaline-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1305816. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Ding, L.; Li, W.; Niu, X.; Gao, D. GRK2 participation in cardiac hypertrophy induced by isoproterenol through the regulation of Nrf2 signaling and the promotion of NLRP3 inflammasome and oxidative stress. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 117, 109957. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Gao, M.; Kong, Y.; Shen, X.; Du, X.; Son, Y.-O.; Shi, X.; Liu, J.; Mo, X. Cardioprotective effect of total paeony glycosides against isoprenaline-induced myocardial ischemia in rats. Phytomedicine international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology 2012, 19, 672–676. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wei, T.; Chang, X.; He, H.; Gao, J.; Wen, Z.; Yan, T. Effects of Salidroside on Myocardial Injury In Vivo In Vitro via Regulation of Nox/NF-κB/AP1 Pathway. Inflammation 2015, 38, 1589–1598. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.; Rojas, D.A.; Urbina, F.; Solari, A. The Use of Antioxidants as Potential Co-Adjuvants to Treat Chronic Chagas Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1022. [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, J.S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders—A step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1066–1077. [CrossRef]

- Peoples, J.N.; Saraf, A.; Ghazal, N.; Pham, T.T.; Kwong, J.Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, K.; Das, J.; Pal, P.B.; Sil, P.C. Oxidative stress: the mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1157–1180. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D. A., & O'Rourke, B. (2010). Cardiac mitochondria and arrhythmias. Cardiovascular research, 88(2), 241–249.

- Da Dalt, L.; Cabodevilla, A.G.; Goldberg, I.J.; Norata, G.D. Cardiac lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1905–1914. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-J.; Xue, Y.-T.; Liu, Y. Cuproptosis, the novel therapeutic mechanism for heart failure: a narrative review. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 12, 681–692. [CrossRef]

- Abu Shelbayeh, O.; Arroum, T.; Morris, S.; Busch, K.B. PGC-1α Is a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Lifecycle and ROS Stress Response. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1075. [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, D.; Butruille, L.; Staels, B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 809–823. [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, C.; Liang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1–44. [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Garnier, A.; Veksler, V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1 alpha. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 79, 208–217. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zou, Y.; Song, C.; Cao, K.; Cai, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Geng, D.; Sun, W.; Ouyang, N.; et al. The role of glycolytic metabolic pathways in cardiovascular disease and potential therapeutic approaches. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2023, 118, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Shu, X.; Zhang, H.-W.; Sun, L.-X.; Yu, L.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.-C.; Yang, Z.-H.; Ran, Y.-L. Enolase 1 regulates stem cell-like properties in gastric cancer cells by stimulating glycolysis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).