1. Introduction

Coronary artery disease, also known as ischemic heart disease, impaired cardiovascular function by increased myocyte rupture, vascular endothelial cell aggregation and stagnation and infiltration and adhesion of leukocytes subsequently leading to acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [

1,

2]. Clinical trial frequently used thrombolytic therapy or percutaneous coronary intervention for timely reperfusion of ischemic tissue to reduce infarct size [

3,

4]. However, myocardial reperfusion itself can further induce and exacerbate myocardial cell damage, a phenomenon commonly referred to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Myocardial I/R injury involves many mechanisms, such as inflammatory response, oxidative stress, Ca2+ overload, ferroptosis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and energy metabolism disorders, and its complex pathogenic mechanisms have not been fully elucidated [

9]. Therefore, efforts are underway to elucidate the exact mechanism of myocardial I/R injury to develop treatment strategies to minimize its consequences. It is well known that mitochondrial dysfunction and impairment play critical roles in cardiac I/R injury through exacerbated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and oxidative stress consequently leading to several types of programmed cell death including apoptosis, ferroptosis and autophagy [

9,

10,

11]. The pathologic mechanisms were possibly due to the formation of H2O2, O2- and OH. Leading to lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage induced cardiovascular diseases [

12,

13]. Therefore, cumulated evidence has indicated that cardiac I/R-induced myocardial damage is closely correlated with mitochondrial impairment, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, ferroptosis, and oxidative stress [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Bcl-2–associated athanogene 3 (BAG3), a member of BAG cofamily protein, can regulate apoptosis, autophagy and development to make cells adapt to the oxidative stress [

14]. BAG3 is highly expressed in the heart, maintains the integrity of sarcomere structure and mitochondria, and reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis [

15]. Cumulated evidence showed that decreases in BAG3 expression caused myomyofibrillary disorders and severe left ventricular dysfunction, decrease in ejection fraction [

16], mitochondrial structure alteration [

17], excess ROS production [

10,

11], decreases in autophagy and increase in apoptosis [

15]. It has also been found that the upregulation of BAG3 protein can improve the cardiac function of mice with I/R induced myocardial infarction and reduce the death of cardiomyocytes [

18]. BAG3 can induce vasodilation and activate PI3K/AKT/eNOS signaling to enhance endothelial function [

19]. BAG3 via autophay and lysosomal pathways cleared damaged mitochondria [

20] to confer a new therapeutic target to cardiac I/R injury [

14]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor (Nrf2) is another critical antioxidant transcription factor and regulates the expression of multiple genes in the process of ferroptosis, like glutathione peroxide 4 (GPX4) [

21].

Cinnamaldehyde is a bioactive component isolated from Chinese herbal medicine

Cinnamonum cassia with many biomedical functions [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. 2'-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde (HCA), a natural derivative of Cinnamaldehyde, can confer anti-tumor activity [

30,

31]. In addition, HCA upregulated BAG3 expression and mediated apoptosis in the cancer cells [

32]. Cinnamaldehyde may exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action to reduce cardiac I/R injury [

33] and activate Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling to protect human endothelial cells against oxidative stress induced damage [

34]. Based on these results, HCA may be an important component for a therapeutic strategy to ameliorate oxidative stress induced cardioavascular diseases. However, none of the evidence has been reported. The present study was designed to investigate the protective effect and mechanisms of HCA preconditioning to prevent and attenuate cardiac I/R injury in vitro and in vivo.

2. Results

2.1. HCA Preconditioning Inhibited H2O2 Induced Cell Death and Upregulated BAG3 Expression in H9c2 Cells

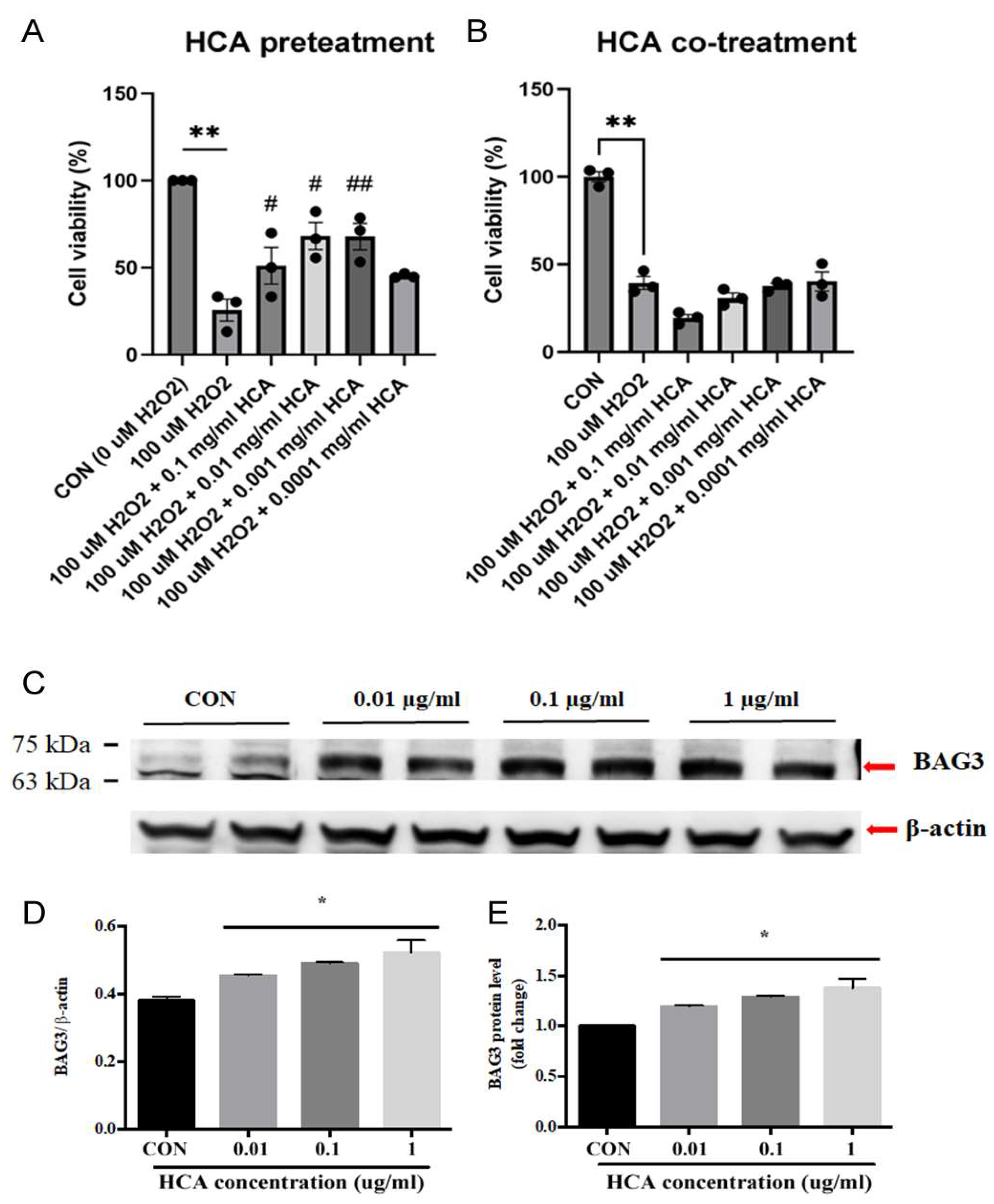

As shown in Figures 1A& 1B, HCA pretreatment significantly inhibited H2O2 induced H9c2 cell death in a dose-dependent manner, whereas HCA co-treatment did not exert a protective effect on H2O2 induced H9c2 cell death. These data inform that a cellular protection may come from a late protection. We further determined the HCA preconditioning on BAG3 expression in H9c2 cells. Our data in

Figure 1C demonstrated that HCA preconditioning significantly enhanced BAG3 expression in a dose-dependent fashion in H9c2 cells and 0.1 mg/ml of HCA displayed the maximal enhancement in BAG3 expression (Figures 1D&1E).

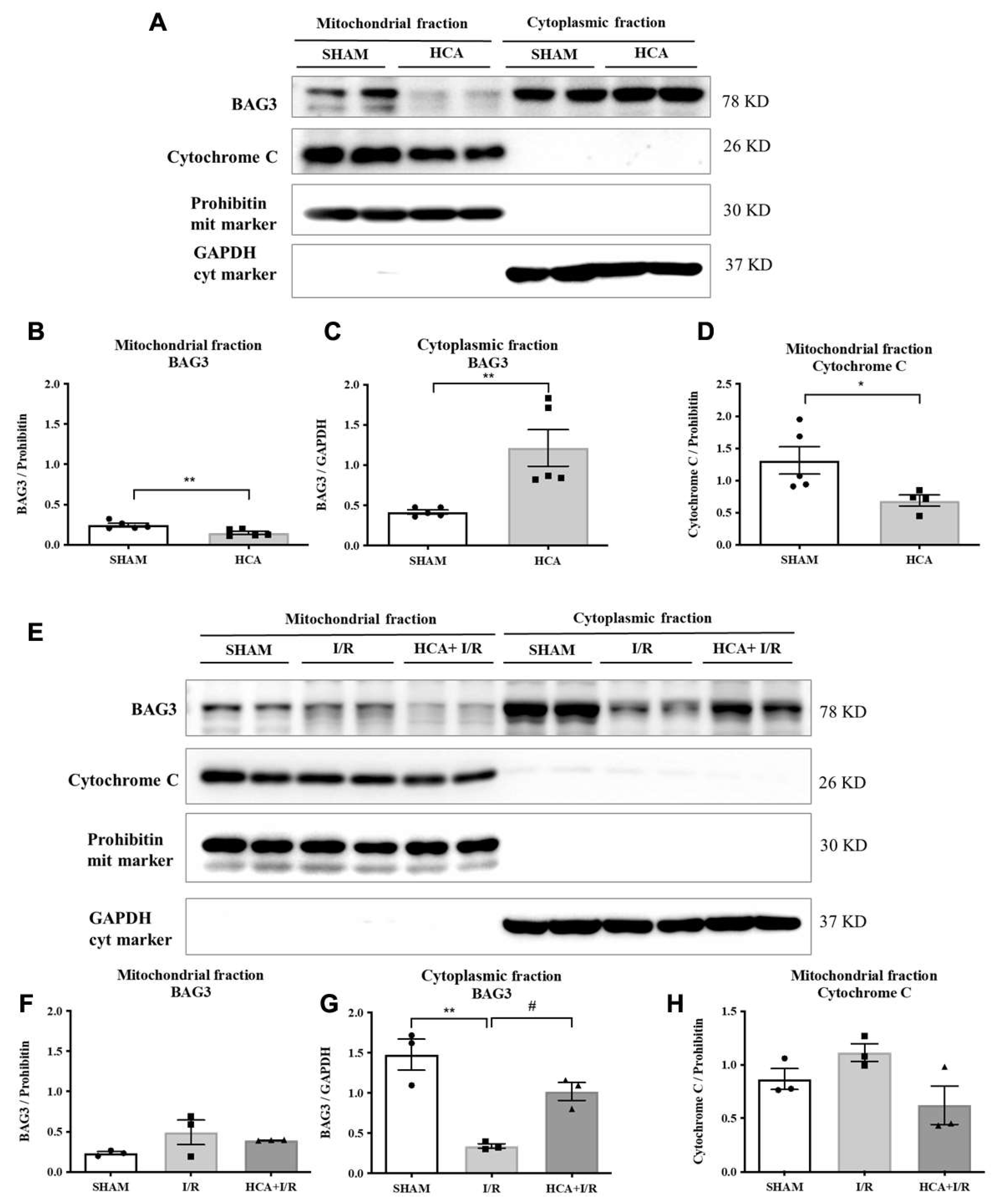

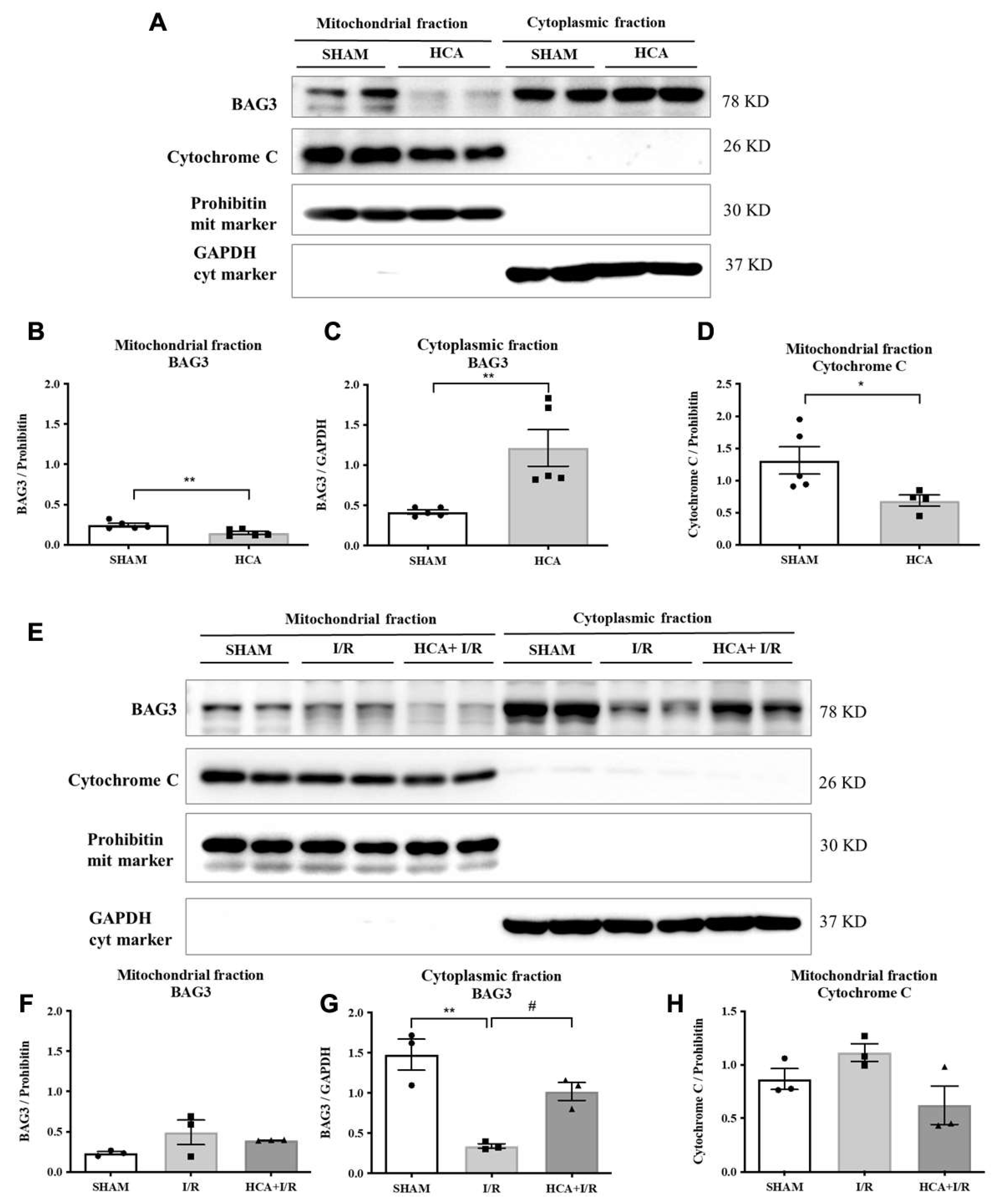

2.2. HCA Preconditioning Increased Cytosolic, Not Mitochondrial BAG3 Expression in HCA and HCA+I/R Hearts

As shown in

Figure 2A, original graphs of cytosolic and mitochondrial BAG3 expression were demonstrated by western blot assay in Sham and HCA hearts. The decreased expression of mitochondrial BAG3 (

Figure 2B), the increased cytosolic BAG3 expression (

Figure 2C) and a decreased mitochondrial cytochrome C (

Figure 2D) were noted between Sham and HCA hearts. As shown in

Figure 2E, the original traces of mitochondrial and cytosolic BAG3 expression were demonstrated among Sham, I/R and HCA+I/R hearts. A significantly reduced cytosolic BAG3 expression is found in I/R group vs. Sham group, whereas a significantly preserved cytosolic BAG3 is observed in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group (

Figure 2G). Mitochondrial fraction of BAG3 expression (

Figure 2F) and cytochrome C expression (

Figure 2H) are not significantly different among Sham, I/R and HCA+I/R groups.

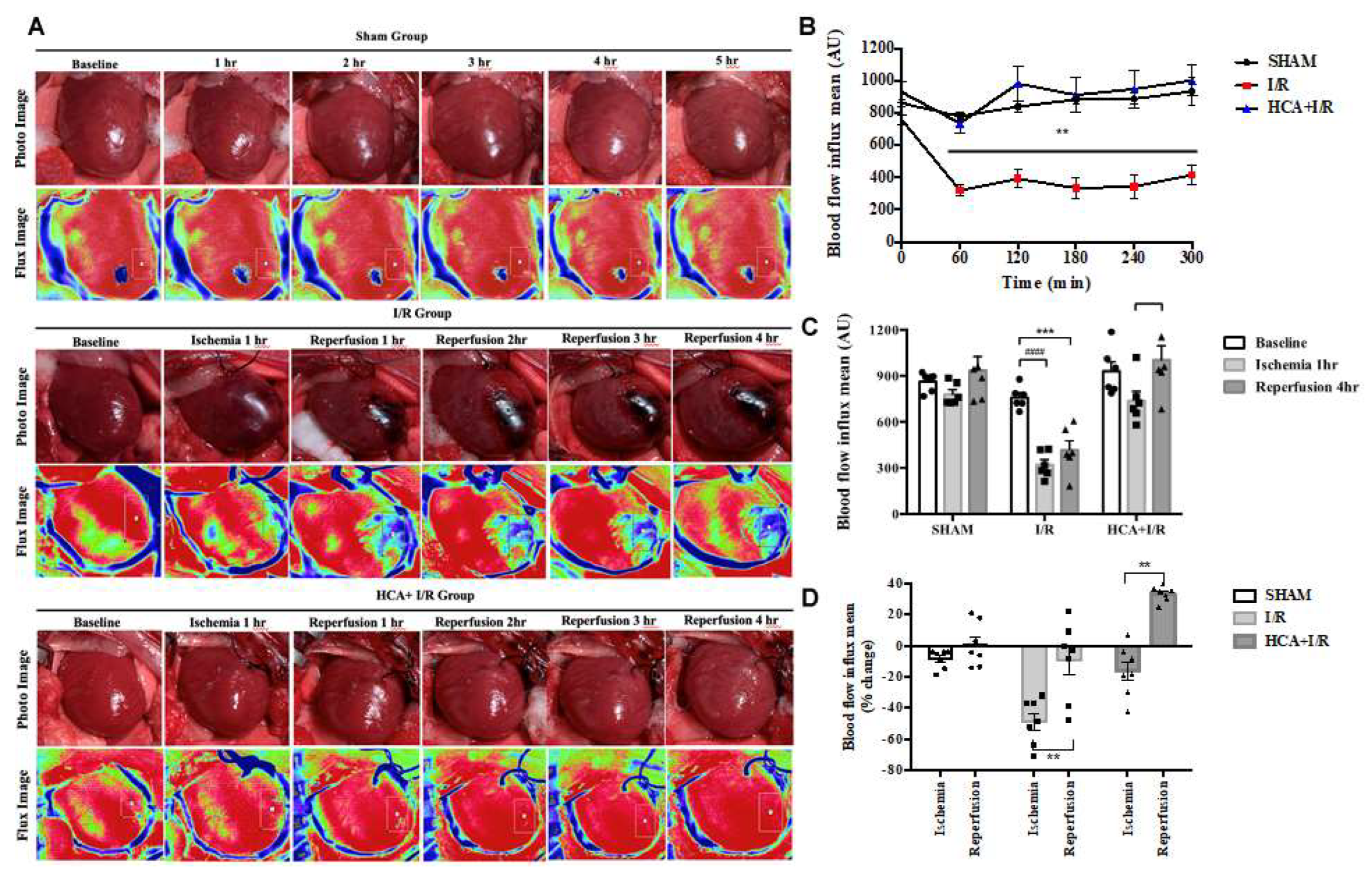

2.3. HCA Preconditioning Preserved Cardiac I/R Decreased Cardiac Surface Microcirculation

After the anesthetized rats underwent thoracotomy to expose the heart, the cardiac surface blood flow was continuously monitored by laser speckle imaging at different time points among three groups (

Figure 3A). Cardiac I/R significantly reduced the blood flow intensity in I/R group vs. Sham group (

Figure 3B). However, HCA preconditioning significantly preserved the cardiac surface microcirculation in HCA+I/R hearts vs. I/R hearts. The decreased percentage of blood flow intensity during ischemia or reperfusion in I/R group was significantly restored in HCA+I/R group (Figures 3C & 3D). There was no significant drop in blood flow after ischemia, and there was a tendency to increase with the blood flow after reperfusion, which showed that the phenomenon of ischemic death due to cardiac I/R could be protected after HCA preconditioning.

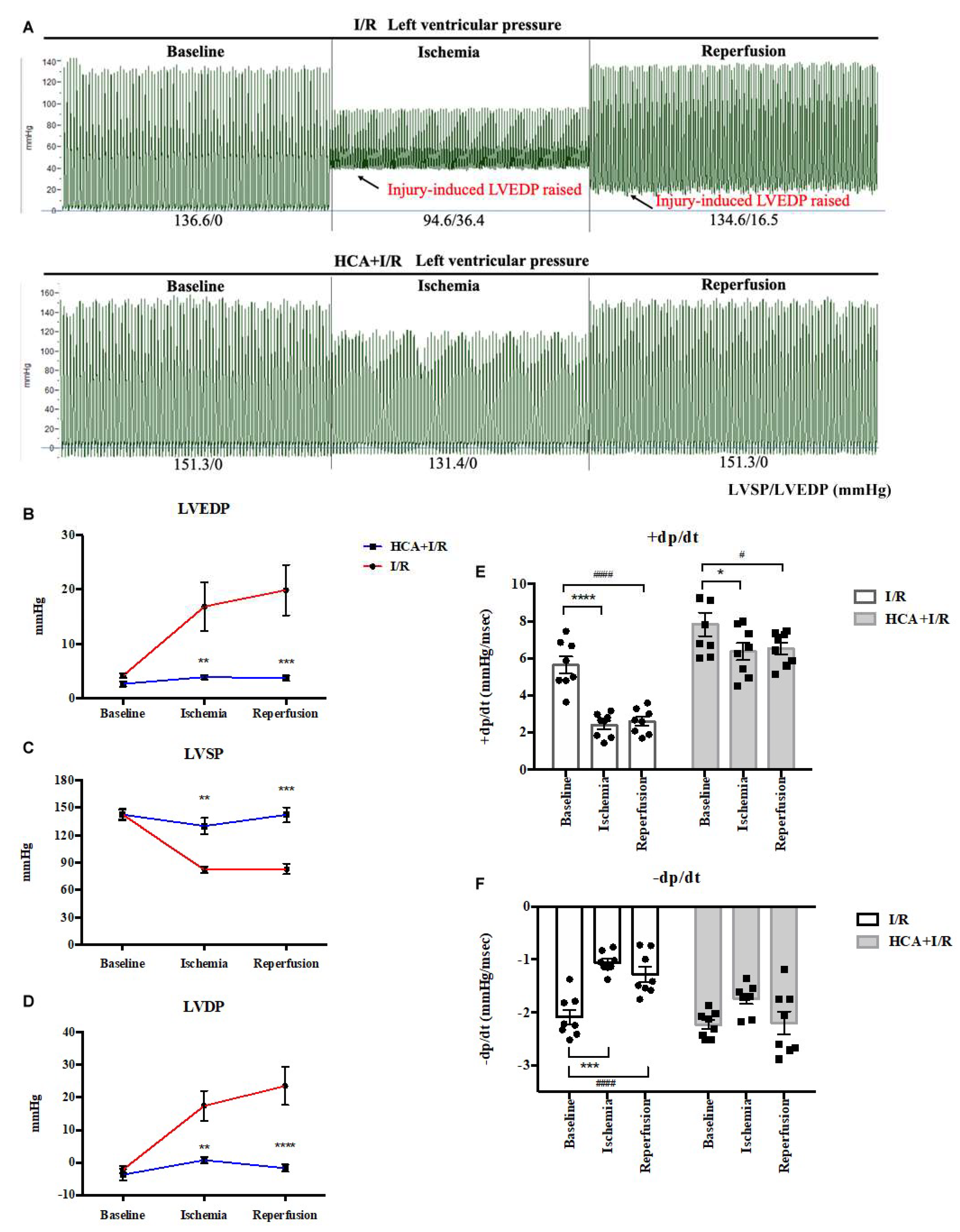

2.4. HCA Preconditioning Restored Cardiac I/R Increased LVEDP and Contractile Activity

The responses of left ventricular pressure during I/R periods in I/R and HCA+I/R groups were demonstrated in

Figure 4A. The statistical data indicated cardiac I/R significantly increased LVEDP (

Figure 4B) and LVDP (

Figure 4D), and decreased LVSP (

Figure 4C), dp/dt (Figures 4E & 4F) in the I/R group vs. HCA+I/R group. HCA preconditioning can effectively improve the strength of myocardial contraction and diastole, maintain the function of cardiac diastole and contraction, and effectively improve the dysfunction of cardiac diastolic and systolic function caused by cardiac I/R injury.

2.5. HCA Preconditioning Improved Cardiac I/R Altered EKG Parameters

We used iWorx 214 to determine EKG parameters including ST segment, R-R interval, P-R interval and heart rate in I/R and HCA+I/R groups (

Figure 5A). Cardiac I/R markedly enhanced ST segment elevation in both I/R and HCA+I/R groups implicating the successful induction of AMI. The statistical data informed that a significant increase in P-R interval (

Figure 5B) and R-R interval (

Figure 5C) and a significant decrease in heart rate (

Figure 5D) were occurred in the I/R period vs. baseline stage. HCA preconditioning significantly restored these altered parameters in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group implicating its capability to maintain the rhythmic function of the heart.

2.6. Effects of Bioactive Peptides from Trtoiseshell, Antler, and Their Combination on the Cell Viability of MC3T3-E1 Osteoblasts and HIG-82 Chondrocytes.

Caridac I/R significantly enhanced mitochondrial fission marker DRP1 expression in I/R group vs. SHAM group, however, HCA preconditioning significantly depressed cardiac I/R enhanced DRP1 expression in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group (Figures 5E&5F).

Figure 5.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R affected EKG parameters and mitochondrial fission. (A) Representative EKG graphs in ST segment, P-R interval and R-R intervals are indicated in I/R and HCA+I/R groups. The statistical data of P-R intervals (B), R-R intervals (C) and heart rate (D) are demonstrated, respectively. Mitochondrial fission marker DRP1 protein expression (E) among three groups and statistical data (F) are presented. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=8). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R affected EKG parameters and mitochondrial fission. (A) Representative EKG graphs in ST segment, P-R interval and R-R intervals are indicated in I/R and HCA+I/R groups. The statistical data of P-R intervals (B), R-R intervals (C) and heart rate (D) are demonstrated, respectively. Mitochondrial fission marker DRP1 protein expression (E) among three groups and statistical data (F) are presented. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=8). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

2.7. HCA Preconditioning Obviously Improved CCardiac I/R Induced Pathologic Alterations

In the histological examination of H&E stained heart tissues, cardiac I/R injury caused the tightly arranged myocardial tissue to become a fragmented structure and obvious interstitial edema (

Figure 6A). Excessive erythrocyte extravasation and leukocyte infiltration were also observed in the I/R tissues (

Figure 6A). A specific biomarker of CD45 for leukocyte stain was significantly increased in I/R vs. HCA+I/R groups (

Figure 6B). The coronary arteries and the surrounding tissues also showed a pathological phenomenon of detachment and damage (

Figure 6A). Compared with the I/R group, the above symptoms were significantly improved in the HCA+I/R group (Figures 6D-6F). Therefore, HCA preconditioning can significantly improve and reduce the damage and destruction of cardiac tissue structure caused by cardiac I/R.

2.8. HCA Preconditioning Decreased Cardiac I/R Induced Fibrosis

Masson’s trichrome stain indicated that cardiac I/R markedly enhanced blue-stain collagen fiber accumulation after I/R injury (

Figure 6C), whereas HCA preconditioning significantly decreased the degree of fibrosis by collagen content vs. I/R hearts (

Figure 6G).

2.9. HCA Preconditioning Attenuated Cardiac I/R Enhanced cTn I and LDH Level

The plasma level of high sensitivity troponin-1 (cTn I) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was used as a biomarker for AMI prognosis. Our results displayed that the value of cTn I and LDH was significantly higher in I/R group vs. SHAM group, whereas these values were significantly decreased in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group (Figures 6H &6I).

Figure 6.

Effect of HCA preconditioning one cardiac I/R induced pathologic changes, leukocyte infiltration and fibrosis among SHAM, I/R and HCA+I/R groups. (A) The structural alterations in response to cardiac I/R are demonstrated by H&E stain among three groups. (B) The immunohistochemistry of CD45 stain (leukocyte biomarker) among three groups. (C) The degree of fibrosis in heart tissue after cardiac I/R injury is indicated by Masson-trichrome stain among three groups. The statistical data in percentage of myocyte content (D), percentage of erythrocyte extravasation (E), leukocyte infiltration (F), collagen volume fraction (G), high sensitivity Troponin-1 (H), and lactate dehydrogenase level (I) are compared among three groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 6.

Effect of HCA preconditioning one cardiac I/R induced pathologic changes, leukocyte infiltration and fibrosis among SHAM, I/R and HCA+I/R groups. (A) The structural alterations in response to cardiac I/R are demonstrated by H&E stain among three groups. (B) The immunohistochemistry of CD45 stain (leukocyte biomarker) among three groups. (C) The degree of fibrosis in heart tissue after cardiac I/R injury is indicated by Masson-trichrome stain among three groups. The statistical data in percentage of myocyte content (D), percentage of erythrocyte extravasation (E), leukocyte infiltration (F), collagen volume fraction (G), high sensitivity Troponin-1 (H), and lactate dehydrogenase level (I) are compared among three groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

2.10. HCA Preconditioning Decreased Cardiac I/R Induced Infarct Size

By using Evans blue-TTC double staining, we characterized cardiac I/R evoked infarct area, area at risk and total left ventricular area. As shown in

Figure 7A, the representative images of infarct size were shown in each six section from these three groups. Cardiac I/R significantly increased infarct area (

Figure 7B), total infarct area (

Figure 7C) and infarct area/AAR (

Figure 7D) in I/R hears vs. SHAM hearts, whereas HCA preconditioning significantly reduced these parameters in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group.

2.11. HCA Preconditioning Enhanced BAG3 Expression and Restored Autophagy Related Proteins in the I/R Hearts

Cardiac I/R significantly decreased cardiac BAG3 expression in I/R vs. SHAM group (Figures 7F&7G), whereas HCA preconditioning efficiently preserved BAG3 expression in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. I/R significantly inhibited cardiac Beclin-1 (Figures 7H & 7J) and LC3II expression (Figures 7H & 7K) in I/R vs. SHAM group, however, HCA preconditioning significantly restored Beclin-1 and LC3II in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. The typical immunohistochemistry of cardiac BAG3, Beclin-1, and LC3II expression was demonstrated in

Figure 7I. The statistical data of immunohistochemic BAG3, Beclin-1 and LC3II were consistently with the western blot and were indicated in Figures 7L, 7M and 7N among these three groups, respectively.

2.12. HCA Preconditioning Decreased Cardiac I/R Induced 4HNE/GPX4 Mediated Ferroptosis and Caspase 3 Mediated Apoptosis

The typical GPX4 and 4HNE stains among three groups were displayed in Figures 8A & 8B, respectively. Cardiac I/R significantly enhanced the percentage of 4HNE stain (

Figure 8C) and significantly depressed GPX4 stain (

Figure 8D) vs Sham group. Also, cardiac I/R markedly increased TUNEL positive stained cells in I/R heart vs. Sham group (

Figure 8E). The statistical analysis of caspase 3 activity (

Figure 8F) and TUNEL positive cells were significantly increased (

Figure 8G) in I/R group vs. Sham group. HCA preconditioning significantly decreased 4HNE stain (

Figure 8C) and preserved GPX4 stain (

Figure 8D) in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. HCA preconditioning significantly decreased caspase 3 activity (

Figure 8F) and TUNEL positive apoptosis stain (

Figure 8G) in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group.

Figure 7.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R induced infarct size, BAG3 and autophagy expression among three groups. The typical infarct area among three groups are displayed in A. The percentage of six sections of infarct area between I/R and HCA+I/R groups are indicated in B. Total infarct area (C), infarct area/AAR (D) and AAR/LV (E) are demonstrated. The cardiac BAG3 expression (F, G), Beclin-1 (H, J) and LC3II (H, K) by western blot analysis are also shown. The immunohistochemistry of BAG3, Beclin-1, and LC3II is indicated in I. The statistic analysis of BAG3, Beclin-1 and LC3II are indicated in L, M and N among three groups, respectively. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

Figure 7.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R induced infarct size, BAG3 and autophagy expression among three groups. The typical infarct area among three groups are displayed in A. The percentage of six sections of infarct area between I/R and HCA+I/R groups are indicated in B. Total infarct area (C), infarct area/AAR (D) and AAR/LV (E) are demonstrated. The cardiac BAG3 expression (F, G), Beclin-1 (H, J) and LC3II (H, K) by western blot analysis are also shown. The immunohistochemistry of BAG3, Beclin-1, and LC3II is indicated in I. The statistic analysis of BAG3, Beclin-1 and LC3II are indicated in L, M and N among three groups, respectively. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

Figure 8.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R induced 4HNE/GPX4 mediated ferroptosis and caspase 3 mediated apoptosis among three groups. The typical GPX4 and 4HNE stains among three groups are displayed in A and B, respectively. The percentage of stain in sections of 4HNE and GPX4 among three are indicated in C and D. The cardiac TUNEL expression among three groups are shown in E. The statistical analysis of caspase 3 activity is demonstrated in F. The statistical analysis of TUNEL positive cells among three groups is indicated in G. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

Figure 8.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R induced 4HNE/GPX4 mediated ferroptosis and caspase 3 mediated apoptosis among three groups. The typical GPX4 and 4HNE stains among three groups are displayed in A and B, respectively. The percentage of stain in sections of 4HNE and GPX4 among three are indicated in C and D. The cardiac TUNEL expression among three groups are shown in E. The statistical analysis of caspase 3 activity is demonstrated in F. The statistical analysis of TUNEL positive cells among three groups is indicated in G. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

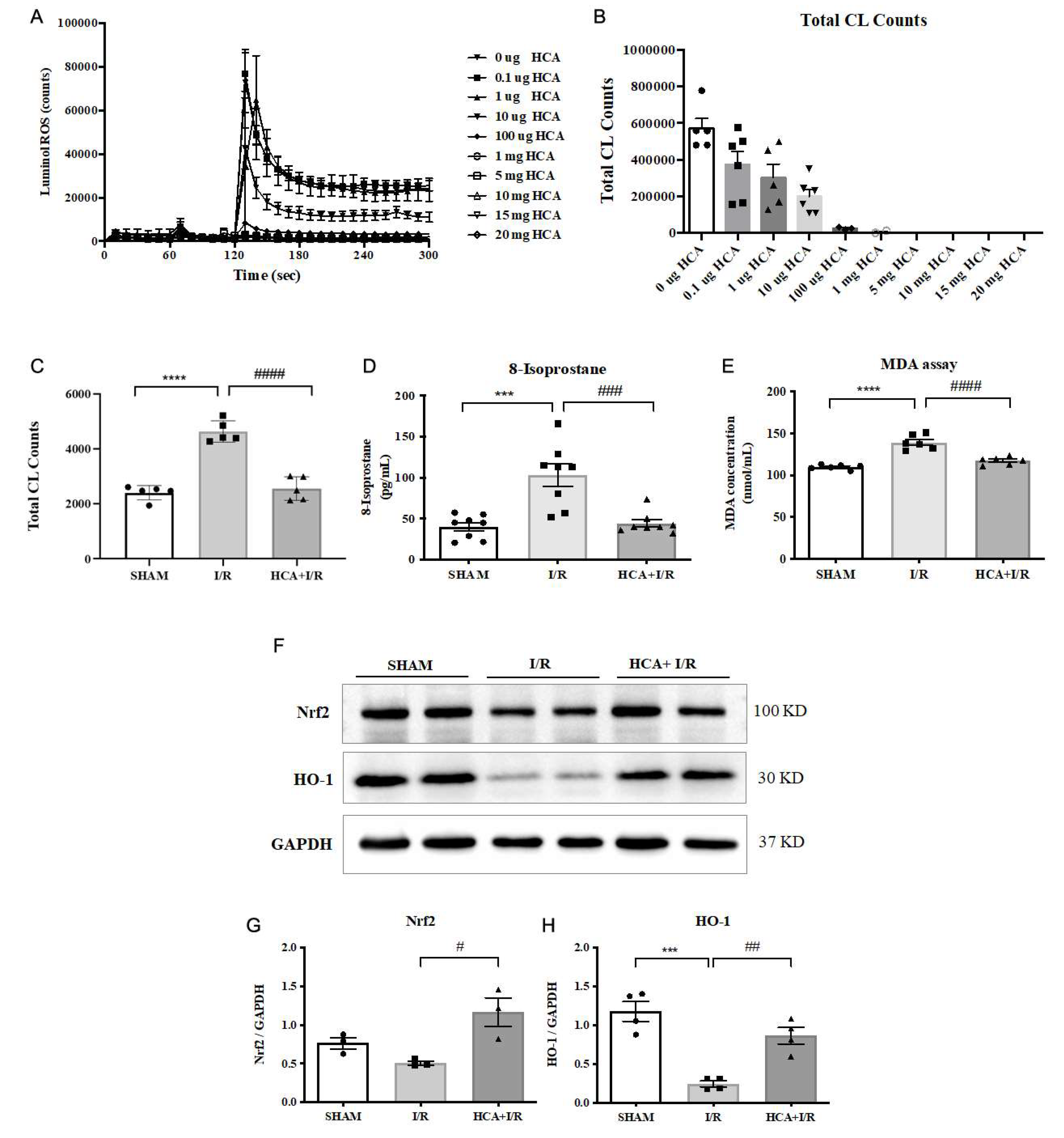

2.13. HCA Provided Antioxidant Activity In Vitro and In Vivo

We determined the ROS scavenging activity in vitro and in vivo in

Figure 9. With the analysis from a CL analyzer, HCA directly, dose-dependently and significantly suppressed the ROS amount in vitro (Figures 9A & 9B). In vivo data showed that cardiac I/R significantly enhanced ROS amount (

Figure 9C), 8-isoprostane (

Figure 9D) and MDA (

Figure 9E) in I/R group vs. Sham group. HCA preconditioning significantly decreased these oxidative stress in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group. In vivo study by western blot found that cardiac I/R decreased cardiac Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in the I/R heart vs. SHAM heart, whereas HCA preconditioning effectively restored cardiac Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in HCA+I/R heart vs. I/R heart (

Figure 9F). According to the he statistical analysis, the ratio of Nrf2/GAPDH (

Figure 9G) and HO-1/GAPDH (

Figure 9H) was significant decreased in I/R heart vs. SHAM heart, however, the decreased ration in Nrf2/GAPDH andHO-1/GAPDH was significantly recovered in HCA+I/R heart vs. I/R heart.

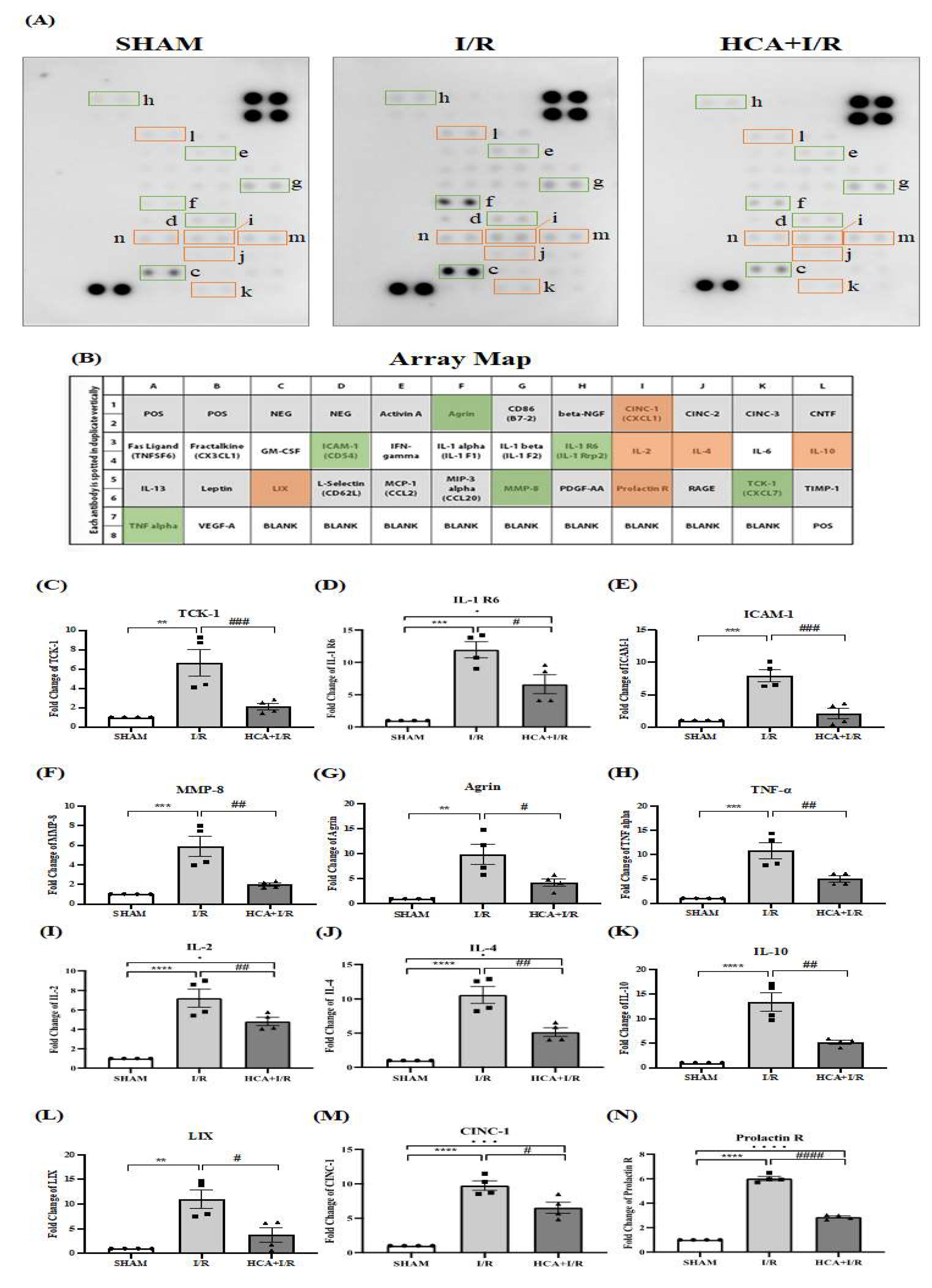

2.14. HCA Preconditioning Reduced Cardiac I/R Injury Induced Multiple Cytokines Expression

Figure 10A demonstrated the original multiple cytokines expression with the matching dots plot in

Figure 10B. The data indicated that the expression of TCK-1 (

Figure 10C), IL-1 R6 (

Figure 10D), ICAM-1 (

Figure 10E), MMP-8 (

Figure 10F), Agrin (

Figure 10G), TNF- (

Figure 10H), IL-2 (

Figure 10I), IL-4 (

Figure 10J), IL-10 (

Figure 10K), LIX (

Figure 10L), CINC-1 (

Figure 10M) and Prolatin (

Figure 10R) were significantly elevated in I/R vs. Sham group, whereas these cytokines are significantly depressed in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group.

3. Discussion

Our in vitro evidence showed that mimic cardiac I/R by H2O2 treatment effectively decreased H9c2 cell viability, however, pretreatment with HCA significantly protected H9c2 cells against H2O2 induced cell death through the induction of BAG3 upregulation in the H9c2 cells. Our in vivo data demonstrated that HCA preconditioning significantly restored the decreased cardiac surface blood flow and microcirculation during I/R periods vs. I/R group. HCA preconditioning further depressed the increased LVEDP level and restored contractile/relaxing function (dp/dt level). In EKG analysis, HCA preconditioning effectively improved cardiac I/R enhanced ST segment elevation, P-R interval delay, R-R interval increase and heart rate decrease. The use of Evans blue-TTC stain also indicated HCA preconditioning efficiently decreased infarct size vs. I/R hearts associated with the decreased level of cTn1 and LDH. In pathologic finding, HCA preconditioning markedly improved cardiac I/R induced myocardial destruction, erythrocyte extravasation, leukocyte infiltration, tissue edema and fibrosis vs. I/R group. Based on our data, HCA preconditioning effectively attenuated cardiac I/R induced oxidative injury and pathologic alterations. In this study, we developed a pharmacologic induction model for upregulation of cardiac BAG3 and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling to determine the beneficial effect on microvascular dysfunction in cardiac I/R injury. Upregulating BAG3 and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling conferred cardiac and vascular protection against cardiac I/R injury. Microvascular function of cardiac circulation can be effectively reinstituted by HCA preconditioning, implying the preventive and palliative benefit in patients with cardiac I/R injury.

Preconditioning with short-term hyperthermia [

35], ischemia [

36] or pharmacological drugs [

29,

33] can confer cardiovascular protection against myocardial I/R injury. Our previous report found that thermal preconditioning enhanced cardiac BAG3 expression and inhibited Bax/Bcl-2 ratio mediated apoptosis formation, but did not affect the Beclin-1/LC3-II mediated autophagy in the I/R heart [

35]. Cinnamaldehyde has been reported with many beneficial health-promoting effects including anti-bacteria [

22], anti-cancer [

23], anti-inflammation [

24], anti-depression [

25], anti-aging [

26] and neurocardiac protection [

27,

28] possibly through BAG3 upregulation. Cinnamaldehyde treatment can confer protection against several types of cardiovascular diseases such as viral myocarditis, ischemic heart disease, arterial atherosclerosis and cardiac hypertrophy [

29]. Cardiac I/R significantly decreased cytosolic BAG3 expression in the H9c2 cells and I/R heart. Our data also confirmed that HCA preconditioning indeed upregulated cardiac BAG3 expression expecially in cytosolic fraction subsequently leading to cardiac protection. In the present study, it is uncertain the mechanism how HCA enhances cytosolic BAG3 overexpression in cardiomyocytes. It requires further studies to be determined. The BAG3 is an anti-apoptotic co-chaperone protein. It has been reported that H/R significantly reduced neonatal myocardial cell BAG3 levels, which were associated with enhanced expression of apoptosis markers, decreased expression of autophagy markers, and reduced autophagy flux [

14]. Using adenoviral bag3 gene transfection significantly rescued I/R decreased infarct size, improved left ventricular function and improved markers of autophagy and apoptosis [

14]. On the other hand, ferroptosis, an rion dependent programmed cell death, was observed in our cardiac I/R hearts by the reduction of GPX4 and increase of 4HNE expression. HCA preconditioning can also ameliorate ferroptotic cell death in the cardiac I/R injury associated with the decreased lipid peroxidation like 8-isoprostane and MDA.

The delay in P-R and R-R interval in EKG signal and a reduction of heart rate were noted in cardiac I/R hearts. The delay or block of the normal electric transmission in EKG may be due to the severe structural destruction in myocytes and coronary artery and tissue edema in the I/R hearts. The cardiac I/R evoked structural alteration associated with the decrease in BAG3 expression possibly resulting in the electric transmission in the heart. BAG3 overexpression in the heart seems to preserve the structural integrity after cardiac I/R injury and to well maintain the EKG parameters. The reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and increased left ventricular end-diastolic diameter were associated with BAG3 mutation related cardiomyopathy and in histologic analysis, myocardial tissue from patients with a BAG3 mutation displayed myofibril disarray and a relocation of BAG3 protein in the sarcomeric Z-disc [

37]. Decreased cardiac expression of BAG3 was correlated with contractile dysfunction and heart failure, decreased BAG3-dependent sarcomere protein turnover impairs mechanical function, and sarcomere force-generating capacity is restored with BAG3 gene therapy [

38]. Our data informed that cardiac I/R decreased BAG3 expression was associated with contractile dysfunction including the increase in LVEDP and decrease in dp/dt, however, overexpression BAG3 in cytosolic fraction by HCA preconditioning effectively restored these contractile dysfunction.

BAG3 has been demonstrated to mediate the initiation of the autophagy pathway in HepG2 cells [

39]. Tahrir et al. [

20] reported that upregulated BAG3 promoted mitochondrial clearance by inhibiting proteasome activity using MG132 to regulate mitochondrial quality control in cardiomyocytes. Our results also revealed that mitochondrial fission marker DRP1 was significantly increased in response to cardiac I/R injury, whereas, HCA preconditioning through upregulation of BAG3 effectively inhibited DRP 1 expression in the HCA+I/R hearts implicating the regulatory role of BAG3 in mitochondrial quality control. By triggering autophagic degradation of impaired mitochondria, mitochondrial fission plays a protective role, however, excessive fission leads to mitochondrial mass loss, ATP deficits and apoptosis promotion [

40]. DRP1 functions with the Bax to evoke mitochondrial fragmentation, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and cytochrome c release in response to apoptosis stimulation [

41]. Inhibition of DRP1 maintains mitochondrial integrity and plays a cardioprotective role during cardiac I/R and cardiac arrest in cells by inhibiting exacerbated fission during I/R injury in murine and rat models [

40]. A recent report has indicated that BAG3 is expressed in primary rat neonatal cardiac fibroblasts and preferentially localizes to mitochondria [

42]. Upregulation of BAG3 by HCA preconditioning may localize in the mitochondria, which in turn protects mitochondria against cardiac I/R enhanced mitochondrial fission. However, this hypothesis will be determined in future. In addition, HCA through directly scavenging ROS activity from our data and upregulating endogenous antioxidant activity in Nrf2 and HO-1 signaling endowed antioxidant defense against cardiac I/R evoked oxidative stress.

I/R-induced inflammatory reaction is one of the most important elements in myocardial I/R injury. Among these, proinflammatory cytokines are a heterogeneous group of mediators that have been associated with activation of numerous functions, including the immune system and inflammatory responses. The presence of extensive inflammation in the hearts of rats subjected to coronary artery ligation has been shown earlier and was confirmed in the present study. Inflammation, documented by accumulation of inflammatory cells and measurement of several cytokines levels appeared at 4 hr after I/R injury. Importantly, our data demonstrate that the pretreatment of HCA downregulates inflammatory leukocyte infiltration and twelve proinflammatory cytokine levels in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group. These findings confer new implication into the molecular events that resolve inflammation after proinflammatory leukocyte activation in subjects undergoing cardiac I/R injury. HCA can inhibit the expression of TCK-1, IL-1 R6, ICAM-1, MMP-8, Agrin, TNF-, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, LIX, CINC-1 and Prolatin expression and decrease the influx of leukocytes in the impaired cardiac tissue according to the results in

Figure 9.

In conclusion, an HCA preconditioning confers an easier strategy to endow cardiac protection against cardiac I/R injury primarily through upregulating endogenous BAG3-mediated preservation of structural and functional integrity in the damaged heart. HCA also provided antioxidant activity to scavenge ROS and enhanced Nrf2/HO-1 mediated antioxidant signaling pathway in the heart.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Effect of HCA on In Vitro Model of Cardiac I/R in H9c2 Cells for Determining Viability

H9c2 cells were provided by ATCC (a nonprofit organization that collects, stores, and distributes standard reference cell lines) and plated in 35-mm dishes at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells/dish to reach ~95% confluence. To mimic in vivo cardiac I/R, cells were treated with 100 μM H2O2 in regular Ca2+ Krebs-Ringer buffer for 12 h followed by 2 h of recovery in full culture medium. To test the HCA effects, H9c2 cells were pretreated or co-treated with different dose of HCA for 6 h. Cell number was determined by a modified MTT assay (Dojindo Chemicals, Kumamoto, Japan). The pretreated effect of HCA on BAG3 expression was also determined in H9c2 cells by western blot analysis.

4.2. Animal Model

Male Wistar rats purchased from BioLASCO Taiwan Co., LTD (Ilan, Taiwan) of 8-10 weeks old (about 250~300 g) were kept at a constant temperature and a fixed photoperiod (light time from 7 am to 6 pm every day) in the Laboratory Animal Center of National Taiwan Normal University. All the experiments were approved (Approval no: 112058; Approval date: 1130131) and followed the guide of the National Science Council of the Republic of China (1977) for the care and experimentation of animals. The animals were randomly divided into SHAM control group, I/R group and HCA+I/R group. HCA was pretreated with intraperitoneal HCA (50 mg/kg body weight) three times/week for 2 weeks.

4.3. Cardiac I/R Injury Induction

In the cardiac I/R experiment, rats were first injected with urethane (1.2 g/kg body weight; Sigma, Missouri, USA) with no significant inhibitory effect on the respiratory and circulatory systems. The rat trachea was intubated with an external respirator (Small Animal Ventilator Model 683; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Mass, USA ), which provided a fixed ventilation volume per minute (8 mL/kg) and a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O per breath, depending on the anesthetized animal's respiratory rate at the time, to ensure subsequent respiration of the animal after thoracotomy. Endotracheal intubation was performed to insert a PE-240 tube between the trachea and C cartilage. Carotid artery cannulation was inserted a PE-50 tube via the left carotid artery into left ventricle for measurement of left ventricle pressure, whereas femoral artery cannulation was applied a PE-50 tube into the left femoral artery for measurement of arterial blood pressure. Femoral vein cannulation was performed by inserting a PE-50 tube into the right femoral vein for injecting normal saline to maintain animal physiological body fluids. After the cannulations, the chest was opened to expose the heart and the 6-0 sewing line (6-0 Prolene, UNIK, Taiwan) was tied the left anterior descending artery of the coronary artery for 60-minute ischemia, and then loosen the knot to reperfuse for 240 minutes. Animals subjected to AMI were successfully established by a decrease in coronary arterial surface blood flow during ischemia and a typical ST segment elevation on ECG graphics.

4.4. EKG Measurement

EKG recording electrodes were inserted subcutaneously on the left and right forelimbs and left hind limbs of rats using iWorx 214 (IX-214; iWorx Systems, Inc, Dover, NH, USA). The AMI could be successfully verified by ECG images of the typical ST segment elevation.

4.5. Parameters of Left Ventricle Pressure

We measured left ventricular pressure (LVP) including left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), left ventricular diastolic pressure (LVDP), left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), maximum increase in left ventricular pressure (+dp/dt) and maximum decrease in left ventricular pressure (-dp/dt) through the left carotid artery cannulation as described previously [

35].

4.6. Cardiac Surface Microcirculation

We determined the cardiac surface microcirculation by using MoorFLPI (Moor Instruments, Ltd, Devon, UK). In brief, continuous monitoring of blood flow on the surface of the heart laser speckle imaging and visible light imaging, the principle is through the laser Doppler velocity measurement technology, after the laser light source irradiates the surface of the object to be measured, the reflected light and scattered light signals will be generated, which will be captured through the lens, and analyzed and processed by the algorithm, the speckle map is obtained, and the rendering of the color algorithm is added on the basis of the speckle map, and the color map with different quantitative data is formed. It is suitable for the detection of continuous intravascular hemoperfusion in tissues. The contrast images are processed to produce 16-color encoded images related to cardiac blood flow, e.g. blue for low flow and red for high flow. The negative control value is set to 0 perfusion units (blue) and the positive control value is set to 1000 perfusion units (red). The perfusion units were analyzed in real time by MoorFLPI software. The successful establishment of an animal model of AMI could be verified by the sudden drop in coronary surface blood flow during ischemia.

4.7. Infarct Size Calculation

The infarct size in the heart was determined as described previously [

20]. Briefly, after reperfusion injury, 5-mL methyl blue was administered via the jugular vein and then the heart was removed. The heart was serially sliced from base to apex at 2-mm intervals. These sections were incubated in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma–Aldrich) at 37°C for 20 min. The infarct area was stained with white and the area at risk was stained with red. Using this method, the area of myocardial infarction, the area at risk, and the total left ventricule (LV) area could be distinguished: blue refers to the normal area, red refers to the ischemia risk area, and white refers to the infarction area. Photographs of heart slices were taken with a digital camera, and the area of each area was quantified, and the ratio of the infarct area to the total area on the scanned image was calculated using ImageJ software: Infarct area/area at risk (AAR), AAR/LV, and Total infarct area.

4.8. HCA Preconditioning Effect on Cytosolic and Mitochondrial BAG3 Expression

The expression of BAG3 in cytosol or mitochondria was determined in the Sham, HCA preconditioning, I/R and HCA+I/R hearts. The mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were obtained with Mitochondria Isolation Kit for tissue (with Dounce homogenizer, ab110169 (MS8510, Abcam). Protein concentration was determined by a BioRad Protein Assay (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Ten µg of protein was electrophoresed as described below. The primary antibody of BAG3 (1:1000, Proteintech, Rosemont, USA), Cytocheome C (1:1000, Bioss_bs-0013R), mitochondrial marker prohibitin (1:1000, Abcam_ab28172) and cytosolic marker GAPDH (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) was used.

4.9. Western Blotting

The method for western blotting was described previously [

4]. Frozen left ventricular tissue obtained from the infarcted area of the rat heart was ground and homogenized in liquid nitrogen, dissolved in the buffer of Radio-immunoprecipitation assay (Bio Basic Inc.) with protease inhibitor (78430, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the homogenate was centrifuged for 30 min at 14000 rpm at 4°C to collect the supernatant. The protein concentrations were determined by BioRad Protein Assay (BioRad Laboratories). After electrophoresis and electro-transferred, the blots were blocked by 5% BSA (A7906, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary and secondary antibodies used in the Western blot and IHC were listed as following: BAG 3 (1:1000, Proteintech, Rosemont, USA), LC3II (1:1000, Proteintech, Rosemont, USA), Beclin-1 (1:1000, Proteintech, Rosemont, USA), DRP1 (D6C7, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), β-actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA), Nrf2 (EP1808Y1:1000, Abcam), HO-1 (ab13248, 1:1000, Abcam) and GAPDH (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG were also used. All protein signals were detected using Western lightning plus-ECL (PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA) and imaged using a cold photographic system ImageQuestTM LAS-4000 (Fujifilm Co., Tokyo, Japan) and quantified using Image J software.

4.10. Antioxidant Activity Determination

The determination of the antioxidant activity of HCA was adapted a ultrasensitive chemiluminescent analyzer as described previously [

42].

4.11. Pathologic Finding

The heart samples after formalin fixation and paraffin embedding, 5-µm sections were applied to Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) stain and Masson’s trichrome stain.

4.12. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

We performed the IHC staining on 10% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded cardiac tissue sections. We deparaffinized and rehydrated these sections with xylene and alcohol. After submitted to antigen retrieval and blocked for non-specific binding, these sections were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used CD45 (ab10558, Abcam, 1:200), BAG3 (1:1000, Proteintech), Beclin-1 (1:1000, Proteintech) and LC3II (1:1000, Proteintech). These sections were incubated with secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase-labeled polymer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 1 h at room temperature and then were immersed in 3’3’-diaminobenzidine and stained in hematoxylin.

4.12. 8-Isoprostane, MDA and Biochemical Determination

8-Isoprostane in plasma were determined with 8-Isoprostane ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA). MDA was assay with Lipid Peroxidation (MDA) Assay Kit (Colorimetric/Fluorometric) (ab118970, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Caspase 3 activity was determined with Caspase-3 Assay Kit (ab3941, Colorimetric, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

4.14. Multiple Cytokine Antibody Array

Inflammatory cytokines may contribute to cardiac I/R injury. We therefore determine the cytokine expression in the plasma from the three groups of rats. Multiple cytokine expression levels were determined by use of RayBio®rat cytokine Antibody Array C1 (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

4.15. Statistical Analysis

All data from Fiji or Image J software data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The measures of interest are the comparisons of the parameters in the rats that underwent coronary artery ligation with vs. without HCA preconditioning. Differences within groups were evaluated by a paired t-test. One-way analysis of variance was used for establishing differences among groups followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Differences were adopted as significant for P < 0.05. We used GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA) for graphs preparation. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software system.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, an HCA preconditioning confers an easier strategy to endow cardiac protection against cardiac I/R injury primarily through upregulating endogenous BAG3-mediated preservation of structural and functional integrity in the damaged heart. HCA also provided antioxidant activity to scavenge ROS and enhanced Nrf2/HO-1 mediated antioxidant signaling pathway in the heart.

Abbreviation:

AAR: area at risk;

AMI: acute myocardial infarction;

BAG3: Bcl-2–associated athanogene;

I/R: ischemia/reperfusion;

HCA: 2‘-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde;

4HNE: 4-hydroxynonenal

HR: heart rate;

+dp/dt: maximal rate of rise in left ventricular pressure;

-dp/dt: maximal rate of fall in left ventricular pressure;

ECG: electrocardiogram;

GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4;

HO-1: heme oxygenase-1;

HRP: horseradish peroxidase;

LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery;

LV: left ventricle;

LVEDP: left ventricular end-diastolic pressure;

LVP: left ventricular pressure;

LVSP: left ventricular systolic pressure;

MDA: malondialdehyde

Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2;

ROS: reactive oxygen species;

TTC: 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride

Author Contributions

conceived the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, and writing-original draft: C.-H.W., C.-T.C., C. -Y, C.; conducted the investigation and methodology of the experiments: Y. -H. C.; provided funding acquisition: C.-H.W., C.-T.C., C. -Y, C.; provided resources, supervision and writing-review & editing: C.-H.W., C.-T.C., C. -Y, C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 111-2314-B-418 -011 from Dr. Chiang C.Y.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are confidential.

Acknowledgments

We thank the XXX.

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

References

- Luan, F.; Lei, Z.; Peng, X.; Chen, L.; Peng, L.; Liu, Y.; Rao, Z.; Yang, R.; Zeng, N. Cardioprotective effect of cinnamaldehyde pretreatment on ischemia/ reperfusion injury via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and gasdermin D mediated cardiomyocyte pyroptosis. Chem. Interactions 2022, 368, 110245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusch, G. Myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury and cardioprotection in perspective. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausenloy, D.J.; Yellon, D.M. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: a neglected therapeutic target. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Wang, H.; Du, F.; Zeng, X.; Guo, C. Protective Effects of the Soluble Receptor for Ad-vanced Glycation End-Products on Pyroptosis during Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9570971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Lee, W.-S.; Yang, K.-T. Methyl palmitate protects heart against ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury through G-protein coupled receptor 40-mediated activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 905, 174183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.N.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, L.Y.; Yin, S.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, S.B.; Fang, L.H.; Du, G.H. Aesculin suppresses the NLRP3 inflam-masome-mediated pyroptosis via the Akt/GSK3β/NF-κB pathway to mitigate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Phy-tomedicine 2021, 92, 153687. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, J.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 modulates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway by sponging miRNA-133a-3p to target IGF1R expression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 916, 174719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-J.; Liu, X.; Hu, M.; Zhao, G.-J.; Sun, D.; Cheng, X.; Xiang, H.; Huang, Y.-P.; Tian, R.-F.; Shen, L.-J.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase ameliorates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in multiple species. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2059–2075.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, L.N.; Popov, S.V.; Naryzhnaya, N.V.; Mukhomedzyanov, A.V.; Kurbatov, B.K.; Derkachev, I.A.; Boshchenko, A.A.; Khaliulin, I.; Prasad, N.R.; Singh, N.; et al. The regulation of necroptosis and perspectives for the development of new drugs preventing ischemic/reperfusion of cardiac injury. Apoptosis 2022, 27, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.T.; Miller, J.H.; Day, M.M.; Munger, J.C.; Brookes, P.S. Accumulation of Succinate in Cardiac Ischemia Primarily Occurs via Canonical Krebs Cycle Activity. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2617–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.A.; Bernstein, D. Mitochondrial remodeling: Rearranging, recycling, and reprogramming. Cell Calcium 2016, 60, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiber, A.; Hahad, O.; Andreadou, I.; Steven, S.; Daub, S.; Münzel, T. Redox-related biomarkers in human cardiovascular disease - classical footprints and beyond. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Xiao, J.-H. The Keap1-Nrf2 System: A Mediator between Oxidative Stress and Aging. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, F.; Myers, V.D.; Knezevic, T.; Wang, J.; Gao, E.; Madesh, M.; Tahrir, F.G.; Gupta, M.K.; Gordon, J.; Rabinowitz, J.; Ramsey, F.V.; Tilley, D.G.; Khalili, K.; Cheung, J.Y.; Feldman, A.M. Bcl-2-associated athanogene 3 protects the heart from ische-mia/reperfusion injury. JCI Insight. 2016, 1, e90931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, T.; Myers, V.D.; Gordon, J.; Tilley, D.G.; Sharp, T.E. 3rd. ; Wang, J.; Khalili, K.; Cheung, J.Y.; Feldman, A.M. BAG3: a new player in the heart failure paradigm. Heart Fail Rev. 2015, 20, 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, S.; Iwasaki, M.; Shelton, G.D.; Engvall, E.; Reed, J.C.; Takayama, S. BAG3 Deficiency Results in Fulminant Myopathy and Early Lethality. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Schaefer, J.; Meinhardt, M.; Reichmann, H. Mitochondrial abnormalities in the myofibrillar myopathies. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, W.; Sadoshima, J. BAG3 plays a central role in proteostasis in the heart. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2900–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizzo, A.; Damato, A.; Ambrosio, M.; Falco, A.; Rosati, A.; Capunzo, M.; Madonna, M.; Turco, M.C.; Januzzi, J.L.; De Laurenzi, V.; et al. The prosurvival protein BAG3: a new participant in vascular homeostasis. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2431–e2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahrir, F.G.; Knezevic, T.; Gupta, M.K.; Gordon, J.; Cheung, J.Y.; Feldman, A.M.; Khalili, K. Evidence for the Role of BAG3 in Mitochondrial Quality Control in Cardiomyocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 232, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.; Castro-Portuguez, R.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2019, 23, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Le, T. The antifungal effects of cinnamaldehyde against Aspergillus niger and its application in bread preservation. Food Chem. 2020, 317, 126405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W. Cinnamaldehyde induces autophagy-mediated cell death through ER stress and epigenetic modification in gastric cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 43, 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Wen, W.; Pan, T.; Chen, H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.H.; Xu, S. Cinnamaldehyde suppresses NLRP3 derived IL-1β via activating succinate/HIF-1 in rheumatoid arthritis rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Yu, T.T.; Zhang, L.P.; Zhao, S.J.; Gu, X.Y.; Pan, Y.; Kong, L.D. Cinnamaldehyde prevents intergenera-tional effect of paternal depression in mice via regulating GR/miR-190b/BDNF pathway. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 1955–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, D.; Huang, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, E.; Liao, S.; Li, E.; Zou, Y.; Wang, W. Antibacterial Mechanism of Cinnamaldehyde: Modu-lation of Biosynthesis of Phosphatidylethanolamine and Phosphatidylglycerol in Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 13628–13636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektaşoğlu, P.K.; Koyuncuoğlu, T.; Demir, D.; Sucu, G.; Akakın, D.; Eyüboğlu, I.P.; Yüksel, M.; Çelikoğlu, E.; Yeğen, B. .; Gürer, B. Neuroprotective Effect of Cinnamaldehyde on Secondary Brain Injury After Traumatic Brain Injury in a Rat Model. World Neurosurg. 2021, 153, e392–e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Shan, X.-L.; Wang, S.-N.; Chen, H.-H.; Zhao, P.; Qian, D.-D.; Xu, M.; Guo, W.; Zhang, C.; Lu, R. Trans-cinnamaldehyde suppresses microtubule detyrosination and alleviates cardiac hypertrophy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 914, 174687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, K.; Li, C.; Xiong, T.; Shi, J.; Dong, N. Cinnamaldehyde protects donor heart from cold ische-mia-reperfusion injury via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 114867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hong, D.; Han, S.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Kwon, B.-M.; Kim, H. Inhibition of Human Tumor Growth by 2′-Hydroxy- and 2′-Benzoyl-oxycinnamaldehydes. Planta Medica 1999, 65, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Ismail, I.A.; Kang, S.; Han, D.C.; Kwon, B. Cinnamaldehydes in Cancer Chemotherapy. Phytotherapy Res. 2016, 30, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-A.; Kim, S.-A. 2′-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde induces apoptosis through HSF1-mediated BAG3 expression. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 50, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, S. Protective effects of cinnamic acid and cinnamic aldehyde on isoproterenol-induced acute myocardial ischemia in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 150, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.; Trinh, N.; Ahn, S.; Kim, S. Cinnamaldehyde protects against oxidative stress and inhibits the TNF-α-induced inflammatory response in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chiang, C.Y.; Chang, T.C.; Chien, C.T. Multiple Progressive Thermopreconditioning Improves Cardiac Ische-mia/Reperfusion-induced Left Ventricular Contractile Dysfunction and Structural Abnormality in Rat. Transplantation 2020, 104, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murry, C.E.; Jennings, R.B.; Reimer, K.A. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardi-um. Circulation 1986, 74, 1124–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez F, Cuenca S, Bilińska Z, et al. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Due to BLC2-Associated Athanogene 3 (BAG3) Muta-tions. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2471–2481.

- Martin, T.G.; Myers, V.D.; Dubey, P.; Dubey, S.; Perez, E.; Moravec, C.S.; Willis, M.S.; Feldman, A.M.; Kirk, J.A. Cardiomyo-cyte contractile impairment in heart failure results from reduced BAG3-mediated sarcomeric protein turnover. Nat. Com-mun. 2021, 12, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-Q.; Du, Z.-X.; Zong, Z.-H.; Li, C.; Li, N.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, D.-H.; Wang, H.-Q. BAG3-dependent noncanonical autophagy induced by proteasome inhibition in HepG2 cells. Autophagy 2013, 9, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahrir, F.G.; Langford, D.; Amini, S.; Mohseni Ahooyi, T.; Khalili, K. Mitochondrial quality control in cardiac cells: Mecha-nisms and role in cardiac cell injury and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 8122–8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Große, L.; Wurm, C.A.; Brüser, C.; Neumann, D.; Jans, D.C.; Jakobs, S. Bax assembles into large ring-like structures remodel-ing the mitochondrial outer membrane in apoptosis. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.G.; Sherer, L.A.; Kirk, J.A. BAG3 localizes to mitochondria in cardiac fibroblasts and regulates mitophagy. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2024, 326, H1124–H1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, C.Y.; Chien, C.T.; Wang, S.S. Progressive thermopreconditioning attenuates rat cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by mitochondria-mediated antioxidant and antiapoptotic mechanisms. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 148, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Effect of HCA pretreatment on H2O2 induced H9c2 cell death and BAG3 expression in H9c2 cells. HCA pretreatment (A) not co-treatment (B) significantly inhibit H2O2 induced H9c2 cells death at the dose of 0.001-0.1 mg/ml of HCA. HCA pretreatment displayed a dose-dependent upregulation of BAG3 expression in H9c2 cells (C-E). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). * indicates significance vs. CON group (*p<0.05; ** p<0.01). # indicates significance vs. H2O2 group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01).

Figure 1.

Effect of HCA pretreatment on H2O2 induced H9c2 cell death and BAG3 expression in H9c2 cells. HCA pretreatment (A) not co-treatment (B) significantly inhibit H2O2 induced H9c2 cells death at the dose of 0.001-0.1 mg/ml of HCA. HCA pretreatment displayed a dose-dependent upregulation of BAG3 expression in H9c2 cells (C-E). All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3). * indicates significance vs. CON group (*p<0.05; ** p<0.01). # indicates significance vs. H2O2 group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on mitochondrial and cytosolic BAG3 expression in Sham, HCA, I/R and HCA+I/R groups. A: original graphs of cytosolic and mitochondrial BAG3 expression by western blot assay in Sham and HCA hearts. A translocation of mitochondrial BAG3 (B) to cytosolic BAG3 (C) and a translocation of mitochondrial cytochrome C (D) are noted between Sham and HCA hearts. E: original traces of mitochondrial and cytosolic BAG3 expression are demonstrated. A significantly reduced cytosolic BAG3 expression is found in I/R group vs. Sham group, Whereas a significantly preserved cytosolic BAG3 is observed in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group (G). Mitochondrial fraction of BAG3 expression (F) and cytochrome C expression (H) are not significantly different among Sham, I/R and HCA+I/R groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3-5). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on mitochondrial and cytosolic BAG3 expression in Sham, HCA, I/R and HCA+I/R groups. A: original graphs of cytosolic and mitochondrial BAG3 expression by western blot assay in Sham and HCA hearts. A translocation of mitochondrial BAG3 (B) to cytosolic BAG3 (C) and a translocation of mitochondrial cytochrome C (D) are noted between Sham and HCA hearts. E: original traces of mitochondrial and cytosolic BAG3 expression are demonstrated. A significantly reduced cytosolic BAG3 expression is found in I/R group vs. Sham group, Whereas a significantly preserved cytosolic BAG3 is observed in HCA+I/R group vs. I/R group (G). Mitochondrial fraction of BAG3 expression (F) and cytochrome C expression (H) are not significantly different among Sham, I/R and HCA+I/R groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3-5). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R evoked changes in cardiac surface microcirculation. (A) Representative responses of cardiac microcirculation to cardiac I/R are demonstrated in these three groups of rats. (B) The statistical data of cardiac surface microcirculation are indicated. A significant decrease in cardiac microcirculation is found in I/R group vs SHAM group, whereas the cardiac microcirculation is restored in HCA+I/R group. (C) The cardiac surface blood flow responses to baseline, 1-h ischemia and 4-h reperfusion are demonstrated among three groups. (D) The mean percentage change of cardiac surface blood flow during ischemia and reperfusion among three groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=6). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R evoked changes in cardiac surface microcirculation. (A) Representative responses of cardiac microcirculation to cardiac I/R are demonstrated in these three groups of rats. (B) The statistical data of cardiac surface microcirculation are indicated. A significant decrease in cardiac microcirculation is found in I/R group vs SHAM group, whereas the cardiac microcirculation is restored in HCA+I/R group. (C) The cardiac surface blood flow responses to baseline, 1-h ischemia and 4-h reperfusion are demonstrated among three groups. (D) The mean percentage change of cardiac surface blood flow during ischemia and reperfusion among three groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=6). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on left ventricular pressure in I/R and HCA+I/R hearts. (A) The typical responses of left ventricular pressure during baseline, ischemia and reperfusion phases in both two groups. The statistical data of LVEDP (B), LVSP (C), LVDP (E), +dp/dt (F) and -dp/dt (G) between I/R and HCA+I/R groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=8). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 4.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on left ventricular pressure in I/R and HCA+I/R hearts. (A) The typical responses of left ventricular pressure during baseline, ischemia and reperfusion phases in both two groups. The statistical data of LVEDP (B), LVSP (C), LVDP (E), +dp/dt (F) and -dp/dt (G) between I/R and HCA+I/R groups. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=8). * indicates significance vs. SHAM group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01;*** p<0.001;**** p<0.0001). # indicates significance vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001; #### p<0.0001).

Figure 9.

Effect of HCA on antioxidant activity in vitro and in vivo. The ROS scavenging activity of HCA in A and B is obtained from CL analyzer. HCA displayed a dose-dependent manner to significantly inhibit ROS activity (B). Cardiac I/R significantly enhances cardiac ROS (C), 8-isoprostane (D) and MDA (E) vs. Sham group, whereas these oxidative stresses are significantly depressed in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. Original western blot shows that cardiac I/R decreases cardiac Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in I/R heart (F), whereas HCA preconditioning partially restores Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in HCA+I/R heart. The statistical data of Nrf2/GAPDH and HO-1/GAPDH are indicated in G and H, respectively. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3-8). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

Figure 9.

Effect of HCA on antioxidant activity in vitro and in vivo. The ROS scavenging activity of HCA in A and B is obtained from CL analyzer. HCA displayed a dose-dependent manner to significantly inhibit ROS activity (B). Cardiac I/R significantly enhances cardiac ROS (C), 8-isoprostane (D) and MDA (E) vs. Sham group, whereas these oxidative stresses are significantly depressed in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. Original western blot shows that cardiac I/R decreases cardiac Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in I/R heart (F), whereas HCA preconditioning partially restores Nrf2 and HO-1 expression in HCA+I/R heart. The statistical data of Nrf2/GAPDH and HO-1/GAPDH are indicated in G and H, respectively. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=3-8). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

Figure 10.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R injury induced multiple cytokines expression by cytokine array analysis among three groups. A: original cytokines expression. B: matching dot plot. The expression of TCK-1 (C), IL-1 R6 (D), ICAM-1 (E), MMP-8 (F), Agrin (G), TNF- (H), IL-2 (I), IL-4 (J), IL-10 (K), LIX (L), CINC-1 (M) and Prolatin (R) is significantly elevated in I/R vs. Sham group, whereas these cytokines are significantly depressed in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=4). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

Figure 10.

Effect of HCA preconditioning on cardiac I/R injury induced multiple cytokines expression by cytokine array analysis among three groups. A: original cytokines expression. B: matching dot plot. The expression of TCK-1 (C), IL-1 R6 (D), ICAM-1 (E), MMP-8 (F), Agrin (G), TNF- (H), IL-2 (I), IL-4 (J), IL-10 (K), LIX (L), CINC-1 (M) and Prolatin (R) is significantly elevated in I/R vs. Sham group, whereas these cytokines are significantly depressed in HCA+I/R vs. I/R group. All the data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n=4). * indicates the significant difference vs. Sham group (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). # indicates the significant difference vs. I/R group (# p<0.05; ## p<0.01; ### p<0.001).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).